Aug 10, 2022 | Volume 12 - Issue 2

Phillip L. Waalkes, Daniel A. DeCino, Maribeth F. Jorgensen, Tiffany Somerville

Supportive relationships with counselor educators as dissertation chairs are valuable to doctoral students overcoming barriers to successful completion of their dissertations. Yet, few have examined the complex and mutually influenced dissertation-chairing relationships from the perspective of dissertation chairs. Using hermeneutic phenomenology, we interviewed counselor educators (N = 15) to identify how they experienced dissertation-chairing relationship dynamics with doctoral students. Counselor educators experienced relationships characterized by expansive connections, growth in student autonomy, authenticity, safety and trust, and adaptation to student needs. They viewed chairing relationships as fluid and non-compartmentalized, which cultivated mutual learning and existential fulfillment. Our findings provide counselor educators with examples of how empathy and encouragement may help doctoral students overcome insecurities and how authentic and honest conversations may help doctoral students overcome roadblocks. Counselor education programs can apply these findings by building structures to help facilitate safe and trusting relationships between doctoral students and counselor educators.

Keywords: dissertation-chairing relationships, hermeneutic phenomenology, counselor education, doctoral students, relationship dynamics

According to the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP; 2015), doctoral students must develop research skills and complete counseling-focused dissertation research. Research mentorship is often important to counselor education doctoral students’ development as researchers (Flynn et al., 2012; Lamar & Helm, 2017; Neale-McFall & Ward, 2015). One of the central research mentoring relationships in doctoral programs is the dissertation-chairing relationship. Supportive research mentoring relationships in counselor education are invaluable to students (Lamar & Helm, 2017), are necessary to successful dissertation chairing (Ghoston et al., 2020; Jorgensen & Wester, 2020), and are a central factor in high-quality doctoral programs (Preston et al., 2020). In fact, a meaningful connection between students and their dissertation chairperson predicts students’ successful completion of their dissertations (Neale-McFall & Ward, 2015; Rigler et al., 2017) and positive dissertation experiences (Burkard et al., 2014). Therefore, to help promote intentional and supportive dissertation-chairing relationships, we examined counselor educators’ experiences of relationship dynamics with doctoral students.

Challenges in Dissertation Completion

Across disciplines, doctoral students can struggle with isolation, motivation, time management, self-regulation, and self-efficacy (Pyhältö et al., 2012). In their development as researchers, doctoral students in counselor education can experience intense emotions, including excitement, exhaustion, frustration, distrust, confusion, disconnection, and pride (Lamar & Helm, 2017). Negative relationships with dissertation chairs can exacerbate challenges to dissertation completion. In one meta-analysis study examining doctoral student attrition across disciplines, doctoral students identified a problematic relationship with their dissertation chairperson as the most significant barrier to their completion of their degrees (Rigler et al., 2017). Doctoral students in counselor education have reported negative experiences when their dissertation chairs were unenthusiastic, unsupportive, and unavailable, and when their guidance was not concrete (Flynn et al., 2012; Lamar & Helm, 2017). In addition, counselor education doctoral students involved in negative dissertation-chairing relationships can feel like they are on their own in their dissertation journeys (Protivnak & Foss, 2009). This feeling of isolation can intensify existing barriers in completing dissertations, including struggles with motivation, self-regulation, self-criticism, and self-efficacy (Burkard et al., 2014; Pyhältö et al., 2012).

Power differentials between doctoral students and dissertation chairs also can serve as a barrier to supportive dissertation-chairing relationships and dissertation completion (Burkard et al., 2014). For example, doctoral students are likely to remain silent in difficult relationships with dissertation chairs unless students perceive there to be a strong relationship built on respect and open communication (Schlosser et al., 2003). Cultural differences and systemic oppression may also impact dissertation-chairing relationships. According to Brown and Grothaus (2019), Black counselor education students can experience overt racism, tokenism, isolation, and internalized racism, which can foster mistrust in cross-racial mentoring relationships. Numerous researchers in counselor education (Borders et al., 2012; Ghoston et al., 2020; Neale-McFall & Ward, 2015; Purgason et al., 2018) have recommended mentors use transparent and honest dialogue with explicit attention to expectations, power dynamics, cultural differences, and potential conflicts.

Supportive Dissertation-Chairing Relationships

Dissertation-chairing relationships with individualized supports can help students overcome barriers to completing their dissertations (Ghoston et al., 2020; Purgason et al., 2018). According to Flynn and colleagues (2012), increased dissertation chairperson involvement can counteract counselor education students’ isolation, burnout, and perceptions of lacking support. Dissertation chairs can help doctoral students identify their low research self-efficacy and offer support, encouragement, and instruction to help address it (Burkard et al., 2014). According to Ghoston and colleagues (2020), a supportive relationship during the dissertation process can help doctoral students be more honest about when they are stuck, which, in turn, allows chairs to give more targeted direction and feedback.

Beginning counselor educators have reported faculty mentoring, care, and support were the most valuable components of their doctoral training (Perera-Diltz & Sauerheber, 2017). Specifically, doctoral students in counselor education value when faculty take time with them, express genuine caring, offer guidance, validate and believe in them, and celebrate their efforts and achievements (Neale-McFall & Ward, 2015; Protivnak & Foss, 2009; Purgason et al., 2018). Counselor education doctoral students also appreciate dissertation chairs who offer regular contact, timely support, and clear and authentic communication (Borders et al., 2012; Ghoston et al., 2020; Jorgensen & Wester, 2020).

Despite the importance of supportive dissertation-chairing relationships in counselor education (Flynn et al., 2012; Jorgensen & Wester, 2020; Neale-McFall & Ward, 2015), little research exists on how counselor educators experience dissertation-chairing relationships with doctoral students. Although researchers have studied dissertation-chairing relationships from the perspectives of counselor education doctoral students (e.g., Flynn et al., 2012; Lamar & Helm, 2017; Neale-McFall & Ward, 2015) and examined relational strategies counselor educators use (e.g., Ghoston et al., 2020; Jorgensen & Wester, 2020), few have examined counselor educators’ perceptions of the relationship as dynamic and mutually constructed. Given their role as faculty and their experiences in multiple dissertation-chairing relationships, dissertation chairs may have more awareness of and broader perspectives on the mutually influenced dissertation relationship and process. Understanding the complexities and nuances of dynamics in chairing relationships may help counselor educators develop more intentional dissertation-chairing practices, subsequently resulting in more successfully completed dissertations. Therefore, we asked the following research question in this hermeneutic phenomenological investigation: What are counselor educators’ lived experiences of dissertation-chairing relationship dynamics with doctoral students?

Method

We utilized a hermeneutic perspective rooted in an interpretive paradigm to guide this study. This perspective aligns with the focus on relationships in our study and emphasizes how individuals make meaning in interaction with others (Heidegger, 1962). Anchored by the viewpoint that all knowledge is relative and based on cultural context, Heidegger’s (1962) hermeneutic phenomenology helped us to construct an evocative description of the essence of participants’ experiences of chairing dissertations in a multi-dimensional and multi-layered way (van Manen, 1990). Hermeneutic phenomenology focuses on uncovering the participants’ experiences of the lifeworld, or their experience of everyday situations and relations (van Manen, 1990). The concept of lifeworld in hermeneutic phenomenology allowed us to examine participants’ lived experiences of human relation, or how they maintain relationships in shared interpersonal space. Therefore, we utilized hermeneutic phenomenology (van Manen, 1990) to investigate counselor educators’ experiences of dissertation-chairing relationships.

Participants and Sampling Procedure

Of 15 participants in our study, eight self-identified as female and seven self-identified as male. Ten participants self-identified as White. Three self-identified with multiple racial and ethnic groups, and two self-identified as African American or Black. Seven participants worked as an associate professor, seven participants worked as a full professor, and one participant worked as an assistant professor. Participants’ ages ranged from 33 to 68 (M = 47.93, SD = 10.18). Years of experience working as a counselor educator ranged from 4 to 29 (M = 16.40, SD = 7.92). Participants reported a wide range of successful chairing experiences, with one to 40 (M = 10.47, SD = 10.39) of their doctoral student advisees defending their dissertations. Nine participants worked at institutions in the Southern Association for Counselor Education and Supervision (ACES) region, three participants worked at institutions in the Western ACES region, two participants worked at institutions in the North Central ACES region, and one participant worked at an institution in the Northeastern ACES region. Five participants worked at institutions with an R2 Carnegie classification (doctoral universities with high research activity). Five participants worked at institutions with an R1 Carnegie classification (doctoral universities with very high research activity). Three participants worked at institutions with an M1 Carnegie classification (master’s colleges and universities with larger programs). Two participants worked at an institution with a D/PU classification (doctoral/professional universities).

Participants qualified for inclusion in this study if they self-identified as a counselor educator working in a CACREP-accredited program and had chaired at least one counseling doctoral student through a successful dissertation defense. After compiling a list of all CACREP-accredited counselor education doctoral programs (N = 33) from information available through the CACREP website, we created a list of names and email addresses of all counselor education faculty (N = 330) working at each of these institutions based on information available on programs’ websites. After receiving IRB approval, we randomly selected 249 faculty members from this list and sent each person a recruitment email and one follow-up email about a week later. Fifteen counselor educators expressed interest, yielding a response rate of 6.05%.

Data Collection

After counselor educators expressed interest in the study, we emailed them a brief demographic data survey, the informed consent document, and the interview questions. We scheduled a time for a semi-structured interview with them and asked them to return their demographic data survey before their interviews. All interviews were conducted through Zoom and audio recorded. The interview protocol consisted of six main open-ended questions and two to four scripted probes for each main question (Patton, 2014). We developed interview questions based on themes within the literature on dissertations and research mentorship (e.g., Flynn et al., 2012; Jorgensen & Wester, 2020; Neale-McFall & Ward, 2015) as well as our own experiences chairing dissertations. Sample interview questions included “How would you describe the characteristics of relationships you want to foster with students?” and “What relational factors help students successfully complete their dissertations with you as a dissertation chair?” Interviews lasted between 38 and 64 minutes. After transcribing the interviews using Rev.com, we deleted the audio files. We determined that we reached saturation at our sample size of 15 participants as we observed the same themes repeatedly emerging in our coding process (Patton, 2014).

Research Team

Our research team consisted of four members. Phillip Waalkes and Daniel DeCino served as the coding team. They both identify as White cisgender male counselor educators with experience chairing dissertations. Maribeth Jorgensen and Tiffany Somerville served as auditors. Jorgensen identifies as a White cisgender female counselor educator with experience chairing dissertations, while Somerville identifies as a White cisgender female counselor education doctoral student. Waalkes, DeCino, and Jorgensen developed the study after a conversation of their experiences chairing dissertations and conducting research in this topic area. We identified how we grew in our identities as dissertation chairs and how we adapted our mentoring styles to meet the needs of students. Considering our experiences as dissertation chairs and doctoral students, we wanted to know how counselor educators developed supportive dissertation-chairing relationships.

To promote reflexivity, the coding team, Waalkes and DeCino, used bridling throughout the data analysis process, utilizing written statements and discussion. Bridling is a process in which researchers actively wait for the phenomenon and its meaning to show itself while also scrutinizing their own involvement with the phenomenon. Bridling requires researchers to acknowledge their pre-understandings and loosen them to allow space for holistic understanding of the phenomenon without seeking to understand too quickly or too carelessly (Dahlberg, 2006). In his reflexivity statement, Waalkes wrote about the importance of timely and individualized feedback and the challenges of building relationships when taking over as dissertation chairperson in the middle of a student’s dissertation process. DeCino discussed his beliefs about the importance of individualized mentoring relationships and the impact of his dissertation experience as a doctoral student on his current dissertation-chairing identity. These reflexive conversations continued between Waalkes and DeCino throughout the data analysis process.

Data Analysis

Based on van Manen’s (1990) inductive data analysis procedure for hermeneutic phenomenology, we coded our data with hermeneutic awareness, reflecting on the data in multidimensional context as opposed to accepting it at face value. Additionally, we designed our procedure to create a hermeneutic circle by shifting between examining parts of the text and reflecting on the interviews as a whole (van Manen, 1990). The development of a thematic structure and a holistic statement (a one-sentence summary of the essence of each participant’s experience) as products of our data analysis reflect our hermeneutic circle.

Our data analysis process consisted of four stages. First, for each interview, Waalkes and DeCino individually created initial holistic statements for each participant. Holistic statements summarized the central significance or fundamental meaning of the participant’s transcript (i.e., text) as a whole. For example, Participant 6’s holistic statement was “Structure, organization, following rules, empathy, scheduled standing meetings to check in personally and professionally, and constructive feedback tailored to students’ needs with an awareness of cultural differences are essential to their dissertation-chairing relationships.” Then, they met to discuss their individual holistic statements and reach consensus on the content of each holistic statement. Second, they individually reviewed each transcript and highlighted essential passages throughout each transcript. Waalkes and DeCino selected passages that were particularly essential or revealing (van Manen, 1990). After selecting a passage, they rewrote it with attention to the context of what was below or above each highlighted section. After rewriting a passage, they reviewed the participants’ holistic statement to ensure that the rewritten passage reflected the interview as a whole. They combined their summary statements of essential passages into a shared spreadsheet. Third, in a series of meetings, Waalkes and DeCino discussed their summary statements and coded each one with a possible theme name. Afterward, they looked for frequently reoccurring codes and combined similar codes to create an initial theme list. Then, they checked that their themes were essential and not incidental by assessing them against the holistic statements and using imaginative variation by asking: “Is this phenomenon still the same if we imaginatively change or delete this theme from the phenomenon?” (van Manen, 1990, p. 107). In conversation, Waalkes and DeCino revised the theme list and structure throughout the imaginative variation process. Finally, Jorgensen and Somerville reviewed the theme list and the holistic statements and offered suggestions that helped refine them.

Trustworthiness

We established trustworthiness in the present study through an iterative data analysis process with hermeneutic awareness and a hermeneutic circle, triangulation of investigators, and bridling through reflexive journaling (Dahlberg, 2006; Hays & Singh, 2012). First, our iterative data analysis process promoted hermeneutic awareness and helped us achieve a hermeneutic circle in checking our thematic structure and our holistic statements compared to each other (van Manen, 1990). Reflecting on the data in context involved approaching the data with an awareness that meaning is never simple or one-dimensional but rather multidimensional and multilayered (van Manen, 1990). To do this, we used individual and consensus coding, evaluation of the data in holistic context using holistic statements, and imaginative variation to summarize only essential parts of participants’ experiences (van Manen, 1990). Second, to achieve triangulation of investigators, Waalkes and DeCino reached consensus throughout the data analysis process (Hays & Singh, 2012). We also utilized two external auditors who read the interview transcripts and provided feedback on our thematic structure and holistic statements. Third, we engaged in reflexive journaling and bridling as described in the research team section above.

Findings

We arranged our findings into five themes: (a) expansive connections, (b) growth in student autonomy, (c) authenticity, (d) safety and trust, and (e) adaptation to student needs. We arrived at these five themes by using imaginative variation to determine which of our themes were essential to participants’ experiences. Each theme is described in the sections below.

Expansive Connections

In the expansive connections theme, participants (n = 11) described how chairing relationships defy compartmentalized definitions and can have wide-ranging and mutually beneficial impacts that extend beyond the dissertation project. For example, Participant 15 offered herself “as a person” to students:

When you sign on to . . . work with me on a dissertation, you don’t just get my technical expertise, you get me as a person . . . and that’s what you get first, actually. So again, it’s not a relationship that’s contained in a box. Hopefully, this is something that grows and actually is something we both are learning from and continues to sustain.

Similarly, Participant 9’s relationships with students extended beyond discussions of dissertations:

I try to talk to [the students I chair] about personal stuff as well as just the dissertation stuff. Because it’s not little neat cubby holes that they put their lives in. What’s going on in their personal life is what’s impacting their progress towards completion. Sometimes it’s just a sigh [of] relief when I ask them “How’s your wife doing? Is the baby walking?” And it gives them a chance to just decompress for a moment and regroup.

Participant 5 described a mutuality in learning through an intense working relationship:

It’s not really a top-down thing, but it’s about learning a craft, and intensely working together to learn that craft . . . it’s a formative process. We’re learning about ourselves as we’re going through it. And I learn from my students as well, while I’m chairing their projects . . . this is a career-building, life-extending experience.

Growth in Student Autonomy

Participants (n = 8) described the importance of using the dissertation relationship to help students take initiative and learn to conduct research on their own. Often participants set clear expectations and boundaries in their relationships to help students do this. For example, Participant 9 encouraged students to take accountability over maintaining momentum in the working alliance:

The student has to recognize this as a partnership, and I can’t react until the student acts. So to me, if I don’t see any action taking place, it’s much more difficult to give you feedback, to give you some kind of response. So that working alliance, I keep pushing that to a student. “What’s your responsibility. What’s my responsibility?”

Participant 2 talked about how he wanted students to be autonomous in planning their dissertations while offering resources:

I’m not the timekeeper. I’m not the helicopter parent. . . . “This is your dissertation, right? This is . . . your life. I will help get you resources, figure out what you need to do to get it done, you know? Beg, buy, borrow, and steal resources to get it done, but you gotta come to me with that.” I’m not gonna say, “Okay, you’re done with stuff a. Stuff b is this. Here’s what you need to do.”

Participant 8 did not want to micromanage students even if students expected that of her:

I don’t want to be your mother. . . he’s like this helpless person. So, I was a little worried that he was continuing to perpetuate these types of dynamics in his life where he was looking for maybe strong women to just come in and take care of things for him . . . I’ve had to be really, really clear about that.

Authenticity

In the authenticity theme, nearly all participants (n = 13) described valuing genuine conversations with students, in which there was a mutuality in sharing vulnerable parts of themselves. These conversations involved discussing both parties’ roles and responsibilities in the relationship. Participants co-constructed the dissertation process by inviting students into honest discussions of the abilities of both parties. For example, Participant 3 described facilitating authentic conversations:

It’s not a one-size-fits-all model . . . every student is different and . . . the process of having the conversation about what they need is a really good relationship-building conversation. And I’m quick to say, “There may be things you want that I can’t provide,” just because I don’t have this skill set or the capacity or the bandwidth in a given day . . . just having those conversations that start that co-constructed collaborative process and empowering them to do their work.

Additionally, participants transparently revealed vulnerable parts about themselves to help students overcome anxiety or other challenges. For example, Participant 12 described the importance of mutual authenticity to facilitate using immediacy to address issues that were causing students to get stuck:

I really need to be able to call out what I see if [the student] may be stuck . . . there needs to be that mutual authentic exchange too . . . authentic relating is my really being able [to feel] like there’s someone for me to call out when I noticed there might be something obstructing [the student’s] capacity to keep moving forward.

Participant 7 viewed being humble and inviting students to share their knowledge as part of being genuine:

I mentioned having that mutual learning attitude and when you do that, that’s being open and honest and genuine with them. Not acting like you know everything. I may be perceived as an expert in some areas, but I don’t want to come off that way actually sometimes. I’ve done a lot of this stuff, but I’m not an expert on this particular area. Tell me what you know. Tell me what you think you know. Tell me what you don’t know that you want to do and I will help you try to get there.

Safety and Trust

In the safety and trust theme, participants (n = 10) discussed how trust and safety served as the foundation for their chairing relationships. Participants acknowledged how mutual trust deepened their connections and helped students feel like their chairperson would help them grow without leaving them floundering. Participants believed safety and trust helped assure students they were going to complete their dissertation and they were not going to be abandoned. For example, Participant 7 discussed the importance of students’ trusting her to offer consistent support:

[Students should] trust me that we can work collaboratively together to make it a good study, that I have the background or I know where to get [help], if you don’t as a student, to help figure out methodology, how to write that prospectus, how to write period. . . . You have to trust me to know how to do that or at least have the resources to help you figure it out, and to trust me that we’re going to be in this together. I’m not going to leave you hanging.

Numerous participants conceptualized students’ needs for safety in terms of expressing and processing strong and often hidden emotions. For example, Participant 5 discussed how students coped with their vulnerability and shame of not feeling good enough:

They need to feel safe . . . I think there’s a lot of shame that goes into developing as a student and maybe even overt or covert. It’s just really tough. It’s such a vulnerable time in your life. I think that doc students, when you get them into groups, they just are very sure and confident. . . . I think that’s such a defensive mechanism to kind of bolster themselves and to kind of propel themselves forward because they’re really trying to, at times, step into these very big roles.

Similarly, Participant 3 conceptualized safety in terms of helping students of color feel like they could make mistakes with him as they navigate biased academic systems:

I really try to bring my years of experience, but I also try to diminish the hierarchy as much as I can. So we have conversations about why we might go this way or why we might go that way rather than it being an edict from me. And I think students appreciate that. I think they feel respected. I think they feel valued. One of the things that I feel very grateful for is that I’ve had the opportunity to have a lot of students of color select me as their dissertation chair. . . . And I think part of that, as they navigate a system that’s still kind of incredibly White and largely biased . . . they feel safe . . . it’s safe to make mistakes . . . They’re going to hand in some versions of drafts that are just not very good. And that’s part of the learning process.

Adaptation to Student Needs

In the adaptation to student needs theme, participants (n = 12) discussed assessing their students’ personalities and tailoring their approaches to meet unique student needs with a mix of support and challenge. For example, Participant 3 described making adjustments based on students’ levels of self-efficacy:

There are some students that I think have a lot of self-efficacy and don’t want me to sugar-coat anything. I can just be very direct and they want me to be direct. They tell me they want me to be direct, but I also recognize for some students, what they’re going to respond better to is more a carrot, less stick. And so, even how I language a comment or something, I’m paying attention to that based on my sense of the student and what they can navigate. If I have a draft of something that it feels like I’ve kind of bled all over and I’ve done a real hatchet job on . . . I’m going to make sure that in the body of the email . . . I’m encouraging.

Similarly, Participant 4 discussed how she personalized encouragement based on students’ needs:

I think of a student I had who needed a lot of validation in the moment, of, “Hey, you’re doing really well. You have all these strengths. These are all the things you’re doing well and I know you can do this. I believe in you.” And then, for others, I know that they needed to sit in the stress or the disappointment a little bit. So to say like, “I hear you. You are struggling right now and I’m going to give you the space for that. And when you’re ready, I’ve got a lot of positive things to say about you. So you let me know when you’re ready for that feedback. It doesn’t sound like you’re ready for it right now.”

Discussion

Because developing as researchers is important for doctoral students (CACREP, 2015) and research mentorship is critical for this purpose (Flynn et al., 2012; Lamar & Helm, 2017; Neale-McFall & Ward, 2015), we investigated counselor educators’ experiences of relationship dynamics with doctoral students when chairing dissertations. Participants reported the complex and mutually influenced dynamics of expansive connections, growth in student autonomy, authenticity, safety and trust, and adaptation to student needs. Our finding of dissertation-chairing relationship dynamics as wide-reaching broadens the focus of previous researchers who have explored these relationships in terms of a series of strategies used by the chairperson (Ghoston et al., 2020) or a list of components contributing to successful dissertation completion (Jorgensen & Wester, 2020). Participants viewed chairing relationships as fluid, mutually influenced, and non-compartmentalized (Purgason et al., 2016), involving a blending of personal and collegial connection that could offer shared learning and fulfillment. Numerous researchers (e.g., Burkard et al., 2014; Flynn et al., 2012) have found that supportive dissertation-chairing relationships can have positive impacts on doctoral students. Yet, a unique finding of this study is that chairing relationships can also positively affect dissertation chairs. Participants discussed growing and experiencing feelings including pride, frustration, and fulfillment from their chairing relationships.

In the growth in student autonomy theme, numerous participants discussed helping students develop more independence and step into a more collegial role in their dissertation-chairing relationships. To a degree, this theme aligns with how Jorgensen and Wester (2020) and Ghoston and colleagues (2020) highlighted the need for accountability and developing doctoral students’ researcher identities in chairing relationships. However, our participants framed helping students become more autonomous as a mutually influenced working alliance that required doctoral student initiative and effort for their chairs to reciprocate. In other words, it seems that dissertation chairs believed doctoral students’ steady effort played a role in creating positive relational momentum throughout a consistent pattern of feedback and support. Additionally, for some participants, fostering student autonomy involved discussing boundaries and the navigation of transference and countertransference within the relationship dynamic. Completing a dissertation can be a challenging process in which students face numerous emotional roadblocks (Lamar & Helm, 2017; Pyhältö et al., 2012) and, for some participants, promoting student autonomy involved exploring and discussing how dependence may function as a defense mechanism for students to cover up their embarrassment, fear, or low self-efficacy.

Our findings also deepen the previous research on the importance of authenticity in dissertation-chairing relationships (Ghoston et al., 2020; Jorgensen & Wester, 2020; Purgason et al., 2016). Many participants directed the relationship toward mutually vulnerable places relevant to students’ dissertations. For example, some participants initiated authentic conversations when students felt stuck. When conflict in a relationship is unacknowledged, the person with less power in the relationship often responds in inauthentic ways; therefore, chairs should take the lead in venturing into vulnerable areas to help move the dissertation forward (Jordan, 2000). For participants, vulnerability included helping students overcome roadblocks and honest discussions and broaching of relationship dynamics, emotions, life experiences, and culture (Jordan, 2010; Purgason et al., 2016).

Our theme of adaptation to student needs highlights the way feedback plays out in mutually impacted relationship dynamics (Ghoston et al., 2020; Jorgensen & Wester, 2020). For example, numerous participants described how they adjusted their feedback styles to meet students’ sensitivity levels. In these cases, participants seemed to be using anticipatory empathy, or the ability to recognize and respond to covert and contextual life circumstances that influence a person (Jordan, 2010). These individualized and emotionally aware strategies can help students overcome barriers in their dissertation processes (Purgason et al., 2018). Additionally, consistent with relational pedagogy (Noddings, 2003), participants viewed dissertation-chairing relationships characterized by trust and safety as critical for helping reduce students’ feelings of shame or inadequacy and helping them feel safe in making mistakes. For many participants, developing trust seemed intertwined with their consistent availability and responding to students with empathy instead of judgment (Purgason et al., 2016).

Interestingly, no participants discussed specific methods they used to evaluate their dissertation-chairing relationships despite previous researchers’ calls to strengthen evaluation of research mentoring relationships (Protivnak & Foss, 2009; Purgason et al., 2018). Utilizing evaluative instruments or conversations in combination with reflection of prior or current experiences with dissertation chairing may help chairs intentionally adjust their feedback and relational styles (Ghoston et al., 2020). The list of items contributing to dissertation chair success developed by Jorgensen and Wester (2020) in their Delphi study of expert dissertation chairpersons may serve as a starting point to develop of such an instrument or help facilitate authentic conversations of needs and expectations between chairs and students.

Implications

Doctoral Students

Because chairing relationships can have broad impacts and can evolve into other professional relationships after dissertation completion, doctoral students might recognize the importance of choosing a chairperson—if they have that luxury—with whom they see potential for deeper connection. Identifying their needs in a chairing relationship might help them choose a chair. To do this, doctoral students might reflect on questions such as: “Which characteristics of a dissertation chairperson are most important to me?” or “What do I need to feel safety and trust in a dissertation-chairing relationship?” Additionally, doctoral students may want to learn more about their program faculty before selecting a chairperson. Doctoral students might interview potential chairs and ask them questions about their relationship styles. Such questions might include: “What did being authentic look like for you in previous chairing relationships?” and “How do you adapt your dissertation chairing to meet student needs?” Doctoral students might also consider their feelings and intuitions about relationships with faculty by assessing the levels of safety, trust, and authenticity they experience with various faculty members.

Ideally, dissertation chairs should facilitate authentic conversations about roadblocks for doctoral students throughout the dissertation process. However, sometimes chairs might be unaware of these roadblocks and doctoral students might consider taking risks to share their insecurities and relational needs with their chairs. Depending on the relational dynamics and power differential, doctoral students might consider the potential benefits and downsides of sharing such information and gauge the level of trust and safety they feel in the relationship. If a dissertation-chairing relationship does not feel safe, a student may consider broaching the topic with their chairperson or, depending upon the culture and policies of their program, switching to another chairperson who feels safer. Alternatively, doctoral students could work on their insecurities and roadblocks with others in their lives, including possibly in their own personal counseling. Personal counseling may be a more appropriate venue to discuss some issues as opposed to the dissertation-chairing relationship. Finally, given the prevalence of intense feelings doctoral students can experience during the dissertation process (Lamar & Helm, 2017; Pyhältö et al., 2012), they might reflect on their insecurities related to their dissertations and the ways their insecurities might affect their dissertation-chairing relationships. As participants discussed in the growth in student autonomy theme, discussing these thoughts and feelings through open and honest dialogue within trusting and safe relationships with their dissertation chairs might help deepen relationships and allow for opportunities to receive more personalized support.

Counselor Educators

To help doctoral students overcome roadblocks and insecurities, dissertation chairs can help students feel more connected through intentional creation of mutually empathic, safe, trusting, and authentic relationships. As the individuals with more power in the relationship, chairs should be ready to initiate conversations that are authentic and help set expectations, including conversations where they broach culture (Jordan, 2010; Purgason et al., 2016). For example, dissertation chairs may consider sharing vulnerable stories from their dissertation journeys or their lives to validate and normalize students’ experiences. Similarly, they might demonstrate humility by admitting the limits of their knowledge and skills and apologizing to students for relational ruptures when appropriate. For instance, a chairperson might admit their lack of knowledge about the methodology a student is using in their dissertation while helping them develop autonomy to seek out resources (e.g., other faculty, books, videos) to get the support they need. Additionally, consistently responding to students with empathy and encouragement if they make mistakes or do not meet deadlines may help build trust and self-confidence for students, creating an environment where they feel safer taking risks interpersonally and with their research. A safe and supportive relational foundation is essential for the trust-building required for learning to take place (Noddings, 2003).

Finally, authentic conversations might also include using immediacy to talk about relationship and cultural dynamics. Utilizing relational-cultural theory (Jordan, 2010; Purgason et al., 2016) may help chairs develop skills for initiating authentic and culturally infused conversations with their students. These conversations might happen throughout the dissertation-chairing relationship. Toward the beginning of the relationship, chairs might ask: “What do you need to build trust and safety in a relationship?” or “How do our cultural differences impact our work together?” At this phase in the relationship, chairs may also openly share their cultural backgrounds and their dissertation styles, including strengths and areas for growth as a dissertation chairperson. Closer to the completion of the dissertation, counselor educators can facilitate discussions with students on the wide-reaching impact of their relationships given the non-compartmentalized nature of dissertation relationships. Chairs might ask students questions such as “How are you different because of our relationship?” or “In what ways has our relationship helped you overcome barriers in your dissertation process?” and be willing to share how the relationship has affected them as well. Acknowledging and reflecting on that shared growth in conversation together may help both parties learn and feel more connected (Purgason et al., 2016).

Counselor educators can use ongoing reflective practice to develop and hone intentional approaches to building dissertation-chairing relationships. Counselor educators might ask themselves, “What relational qualities do I have to offer that contribute to helpful dissertation-chairing relationships?”, “How do I believe that mentoring relationships impact mentees’ development as researchers?”, or “What theories drive my research mentorship philosophy?” As a tangible output for addressing these questions, counselor educators can write philosophy of research mentorship statements, similar to philosophy of teaching or supervision statements. These statements can help counselor educators comprehensively define their approaches to research mentoring relationships. Counselor educators might revisit these statements throughout their careers as research on mentoring and their beliefs about dissertation chairing evolve. Additionally, counselor educators might create and share advisor disclosure statements with doctoral students to help clarify roles and expectations (Sangganjanavanich & Magnuson, 2009). Advisor statements may help alleviate role confusion and emphasize to students early in the relationship that doctoral students should grow as autonomous researchers and contribute to building a working alliance.

Counseling Programs

Numerous researchers have called for doctoral counseling programs to integrate more purposeful research mentorship in structured and systematic ways that could help offer more supportive relationships for doctoral students (Lamar & Helm, 2017; Perera-Diltz & Sauerheber, 2017). Counseling programs could establish structures that allow counselor educators and doctoral students to build trust early on in students’ programs. Connections developed between dissertation chairs and students in research apprenticeships; research teams; and co-teaching, advising, and informal program gatherings may provide relationships space to grow before students start their dissertations. Counseling programs might also establish methods for helping counselor educators evaluate dissertation-chairing relationships (Protivnak & Foss, 2009). Gaining an understanding of how students internalize feedback may help dissertation chairs better adapt to student needs and intentionally build expansive relationships (Ghoston et al., 2020). In line with CACREP’s requirement that counseling programs comprehensively evaluate their effectiveness, programs could regularly send out surveys to doctoral students who have recently completed their dissertations or withdrew during the dissertation stage to seek feedback on former students’ experiences of dissertation-chairing relationships (CACREP, 2015, Section 4). Such surveys might ask former students about their experiences of receiving feedback, the impact of their dissertation-chairing relationship, time and resources their chairperson dedicated to them, and challenges and successes they faced during the dissertation process. Program faculty could then use this feedback to improve their research mentoring programs by developing strategic plans including both individual and programmatic concrete goals (Purgason et al., 2018). Alternatively, dissertation chairs could conduct exit interviews with students.

Limitations

We identified several limitations in our study. First, all research team members identified as White, which may have limited our data analysis process based on our shared, privileged racial/ethnic identity. A coding team with different races and ethnicities may have arrived at a different thematic structure and may have more heavily emphasized cultural considerations in dissertation-chairing relationship dynamics. Second, in our interview protocol and demographic data survey, we did not ask many questions eliciting depth on the culture of participants’ institutions. Knowing more about the structures of participants’ programmatic and institutional supports and stressors for faculty members (e.g., teaching loads, policies that may contradict supporting student success) may have helped us analyze our data with a richer appreciation of contexts (van Manen, 1990; Hays & Singh, 2012). Third, our worldviews possibly influenced the questions we did not ask participants regarding how they navigated cultural differences with their students. Even though a few participants talked about navigating cultural differences, we do not have a clear sense of how cultural differences influenced participants’ chairing relationships. Cross-cultural mentorship relationships in counselor education are influenced by a myriad of complex relational and contextual factors related to racial/ethnic identity and White racism inherent in the field of counseling (Brown & Grothaus, 2019). These cross-cultural relationships warrant more focused investigation. Fourth, counselor educators who emphasized relationship-building in their dissertation chairing may have been more likely to participate in our study because they believed in the importance of our topic. Therefore, our findings may not reflect the relationships of those who do not emphasize relational approaches to dissertation chairing. Fifth, we did not explore dissertation relationships that took place in virtual programs. Chairs may experience relationship dynamics differently when interactions only occur virtually as opposed to mostly in person.

Directions for Future Research

First, future researchers might explore how counselor educators and doctoral students navigate power dynamics and cultural context in dissertation-chairing relationships (Borders et al., 2012; Jorgensen & Wester, 2020; Neale-McFall & Ward, 2015; Purgason et al., 2018). Fostering mutually fulfilling connections in dissertation-chairing relationships may help counselor educators attend to the unique needs of underrepresented students (Purgason et al., 2016) and help make research more accessible to doctoral students from more collectivist cultural backgrounds. Given the importance of authentic conversations and egalitarian relationships expressed by participants, further exploration of how counselor educators approach cultural, country of origin, worldview, gender, and other differences in dissertation-chairing relationships between themselves and students seems warranted. Second, participants in this study mostly talked about positive outcomes of dissertation-chairing relationships and helpful strategies they used to build relationships. Given the prevalence of negative dissertation relationships reported by doctoral students and their harmful impact on completion rates and mental health (Flynn et al., 2012; Lamar & Helm, 2017; Protivnak & Foss, 2009; Rigler et al., 2017), future researchers might examine ways that dissertation chairs can identify, navigate, and heal relational ruptures. Third, outcome research could illuminate the positive and negative impacts that dissertation-chairing relationships can have on students’ researcher self-efficacy, researcher identity development, and future research productivity. Because participants described tailoring their feedback styles to meet students’ unique needs but did not clearly describe evaluating the impact of their feedback, future researchers might examine the impact that different forms and styles of feedback have on students. Fourth, future researchers should explore institutional and programmatic factors that complicate chairs’ abilities to provide research mentorship to students. Finally, there are numerous theories of counseling supervision and adult learning that may apply to dissertation-chairing relationships but few theories specific to research mentorship or dissertation-chairing relationships in counselor education (Purgason et al., 2016). Future researchers might develop theories in this area by asking counselor educators about values, beliefs, and attitudes that drive their research mentorship philosophy and practice or by writing conceptual articles applying existing counseling theories to dissertation chairing.

Conclusion

Our research offers insights from counselor educators on how to foster supportive dissertation-chairing relationships. Counselor educators may utilize our findings to facilitate reflection regarding their relationship-building skills in dissertation-chairing relationships. Counselor educators intentionally build dissertation-chairing relationships to help their students overcome barriers to completing their dissertations and preparing them as future scholars.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Borders, L. D., Wester, K. L., Granello, D. H., Chang, C. Y., Hays, D. G., Pepperell, J., & Spurgeon, S. L. (2012). Association for Counselor Education and Supervision guidelines for research mentorship: Development and implementation. Counselor Education and Supervision, 51(3), 162–175.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2012.00012.x

Brown, E. M., & Grothaus, T. (2019). Experiences of cross-racial trust in mentoring relationships between Black doctoral counseling students and White counselor educators and supervisors. The Professional Counselor, 9(3), 211–225. https://doi.org/10.15241/emb.9.3.211

Burkard, A. W., Knox, S. K., DeWalt, T., Fuller, S., Hill, C., & Schlosser, L. Z. (2014). Dissertation experiences of doctoral graduates from professional psychology programs. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 27(1), 19–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2013.821596

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2015). 2016 CACREP standards. https://www.cacrep.org/for-programs/2016-cacrep-standards

Dahlberg, K. (2006). The essence of essences: The search for meaning structures in phenomenological analysis of lifeworld phenomena. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 1(1), 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482620500478405

Flynn, S. V., Chasek, C. L., Harper, I. F., Murphy, K. M., & Jorgensen, M. F. (2012). A qualitative inquiry of the counseling dissertation process. Counselor Education and Supervision, 51(4), 242–255.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2012.00018.x

Ghoston, M., Grimes, T., Graham, J., Grimes, J., & Field, T. A. (2020). Faculty perspectives on strategies for successful navigation of the dissertation process in counselor education. The Professional Counselor, 10(4), 615–631. https://doi.org/10.15241/mg.10.4.615

Hays, D. G., & Singh, A. A. (2012). Qualitative inquiry in clinical and educational settings. Guilford.

Heidegger, M. (1962). Being and time (J. Macquarrie & E. Robinson, Trans.). Harper and Row.

Jordan, J. V. (2000). The role of mutual empathy in relational/cultural theory. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56(8), 1005–1016. https://doi.org/cfp6pr

Jordan, J. V. (2010). Relational–cultural therapy. American Psychological Association.

Jorgensen, M. F., & Wester, K. L. (2020). Aspects contributing to dissertation chair success: Consensus among counselor educators. Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 13(3), 117–144.

http://doi.org/10.7729/42.1404

Lamar, M. R., & Helm, H. M. (2017). Understanding the researcher identity development of counselor education and supervision doctoral students. Counselor Education and Supervision, 56(1), 2–18.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12056

Neale-McFall, C., & Ward, C. A. (2015). Factors contributing to counselor education doctoral students’ satisfaction with their dissertation chairperson. The Professional Counselor, 5(1), 185–194.

https://doi.org/10.15241/cnm.5.1.185

Noddings, N. (2003). Caring: A feminine approach to ethics and moral education (2nd ed.). University of California Press.

Patton, M. Q. (2014). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice (4th ed.). SAGE.

Perera-Diltz, D., & Sauerheber, J. D. (2017). Mentoring and other valued components of counselor educator doctoral training: A Delphi study. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 6(2), 116–127. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMCE-09-2016-0064

Preston, J., Trepal, H., Morgan, A., Jacques, J., Smith, J. D., & Field, T. A. (2020). Components of a high-quality doctoral program in counselor education and supervision. The Professional Counselor, 10(4), 453–471. https://doi.org/10.15241/jp.10.4.453

Protivnak, J. J., & Foss, L. L. (2009). An exploration of themes that influence the counselor education doctoral student experience. Counselor Education and Supervision, 48(4), 239–256.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2009.tb00078.x

Purgason, L. L., Avent, J. R., Cashwell, C. S., Jordan, M. E., & Reese, R. F. (2016). Culturally relevant advising: Applying relational-cultural theory in counselor education. Journal of Counseling & Development, 94(4), 429–436. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12101

Purgason, L. L., Lloyd-Hazlett, J., & Avent Harris, J. R. (2018). Mentoring counselor education students: A Delphi study with leaders in the field. Journal of Counselor Leadership and Advocacy, 5(2), 122–136.

https://doi.org/10.1080/2326716X.2018.1452080

Pyhältö, K., Toom, A., Stubb, J., & Lonka, K. (2012). Challenges of becoming a scholar: A study of doctoral students’ problems and well-being. International Scholarly Research Notices, 2012.

https://doi.org/10.5402/2012/934941

Rigler, K. L., Bowlin, L. K., Sweat, K., Watts, S., & Thorne, R. (2017). Agency, socialization, and support: A critical review of doctoral student attrition. Paper presented at the 3rd International Conference on Doctoral Education, University of Central Florida.

Sangganjanavanich, V. F., & Magnuson, S. (2009). Averting role confusion between doctoral students and major advisers: Adviser disclosure statements. Counselor Education and Supervision, 48(3), 194–203.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2009.tb00074.x

Schlosser, L. Z., Knox, S., Moskovitz, A. R., & Hill, C. E. (2003). A qualitative examination of graduate advising relationships: The advisee perspective. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50(2), 178–188.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.50.2.178

van Manen, M. (1990). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy (1st ed.). Althouse Press.

Phillip L. Waalkes, PhD, NCC, ACS, is an assistant professor at the University of Missouri – St. Louis. Daniel A. DeCino, PhD, NCC, LPC, is an assistant professor at the University of South Dakota. Maribeth F. Jorgensen, PhD, NCC, LPC, LMHC, LIMHP, is an assistant professor at Central Washington University. Tiffany Somerville, MS, is a doctoral student at the University of Missouri – Saint Louis. Correspondence may be addressed to Phillip L. Waalkes, 415 Marillac Hall, 1 University Blvd., St. Louis, MO 63121, waalkesp@umsl.edu.

Feb 7, 2022 | Volume 12 - Issue 1

Clark D. Ausloos, Madeline Clark, Hansori Jang, Tahani Dari, Stacey Diane Arañez Litam

Trans youth experience discrimination and marginalization in their homes, communities, and schools. Professional school counselors (PSCs) are positioned to support and advocate for trans youth as dictated by professional standards. However, an extensive review of literature revealed a lack of confidence and competence in counselors working with trans youth and their families. Further, there is a dearth of literature that addresses factors leading to increased school counselor competence with trans students. The current study uses a cross-sectional survey design to contribute to the extant literature and explore how PSCs in the United States work with students in the K–12 public school system. Results from multiple regression analyses indicate that PSCs who have had postgraduate training and report personal and professional experiences with trans students are more competent in working with trans students. Implications for PSCs and school counselor education programs are discussed.

Keywords: trans youth, school counselors, competence, counselor education, multiple regression analysis

Trans people experience an incongruence between their sex assigned at birth and their gender identity (GI; Ginicola et al., 2017; McBee, 2013). The term trans encompasses a wide range of gender-expansive identities, including trans (transgender), nonbinary (one who identifies outside the gender binary of male or female), genderqueer or gender-fluid (one who identifies with gender in a fluid, dynamic way) and agender (one who does not identify as having a gender). Trans people face pervasive discrimination and marginalization (Whitman & Han, 2017), leading to severe physical and mental health disparities, like depression, anxiety, and suicidality (James et al., 2016). In schools, trans students face 4 times higher rates of discrimination when compared with cisgender peers (Kosciw et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2021). Trans students are more vulnerable to mental health disorders, a lack of social support, and an increase in self-harm, suicidal ideations, and suicide attempts (Kosciw et al., 2020; Reisner et al., 2014), especially among transmale and nonbinary students (Toomey et al., 2018). These rates are increasing in national trends and are even higher among Black and Latinx trans students (Vance et al., 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated barriers and inequities for trans students, with increasing health concerns, isolation, economic hardships, issues with housing, and limited access to essential clinical care (Burgess et al., 2021).

Increasingly, trans students face systemic legal barriers to their health and well-being (Wang et al., 2016). States including Arkansas, Idaho, Montana, South Dakota, and Tennessee have introduced bills that ban trans students from participating in sports that are congruent with their GI (Transgender Law Center, 2021). In April of 2021, Arkansas banned medical gender-affirming services to students under 18 years of age (American Civil Liberties Union [ACLU], 2021). New Hampshire’s House Bill 68 proposed adding gender-affirming treatments to the definition of child abuse (ACLU, 2021). Beyond political oppression, trans youth experience overt discrimination, verbal abuse, physical and sexual assault, and marginalization within their homes, schools, and places of employment (Human Rights Campaign [HRC], 2018; James et al., 2016). Trans youth additionally face disaffirming and incompetent teachers and medical professionals (Grant et al., 2011; James et al., 2016; Whitman & Han, 2017) and embedded systemic transmisia (the hatred of trans persons; Simmons University Library, 2019). Despite the pervasive mental health concerns faced by trans students (i.e., depression, anxiety, disordered eating, self-harm, suicide), professional school counselors (PSCs) continue to be ill equipped in supporting and advocating for this marginalized population within schools (Simons, 2021). Based upon an analysis of the extant body of research, we found that counselor education training programs lack rigor in working with trans students (O’Hara et al., 2013; Salpietro et al., 2019), counselor educators may hold biased views about trans students (Frank & Cannon, 2010), and there is an absence of quality professional development opportunities on trans issues (Salpietro et al., 2019; Shi & Doud, 2017). It is therefore of paramount importance for PSCs and counselor education programs to obtain a deeper understanding of how to better prepare for and support trans students in schools.

Professional School Counselors and Trans Students

PSCs focus on academic, career, and social-emotional growth and work as leaders alongside teachers, administration, families, and other stakeholders. PSCs are therefore well positioned to provide safety and support for trans students, promote change, and act as social justice advocates within schools (Bemak & Chung, 2008). The American School Counselor Association (ASCA) mandates that PSCs “promote affirmation, respect, and equal opportunity for all individuals regardless of . . . gender identity, or gender expression . . . and promote awareness of and education on issues related to LGBT students” (2016a, p. 37). PSCs who work with trans students may provide services through the Multitiered Systems of Support lens (MTSS; ASCA, 2019), through collaboration, by supporting school administration and staff (e.g., trainings, meetings, workshops), and through provision of direct student services (e.g., individual and group counseling, working with families). More specifically, PSCs advocate for and with students for name and pronoun changes within schools, trans-inclusive school policies, and increased visibility and normalization of trans people and issues.

ASCA (2016b) adopted a position that PSCs recognize that “the responsibility for determining a student’s gender identity rests with the student rather than outside confirmation from medical practitioners . . . or documentation of legal changes” (p. 64). It is clear that PSCs should possess knowledge and skills in working with and advocating for trans youth through a range of services at various levels and in coordination with other stakeholders in schools, all while respecting students’ autonomy and authenticity (ASCA, 2016a, 2016b, 2019; Bemak & Chung, 2008).

Counselor Education Programs

Although professional standards provide best practices (ALGBTIC LGBQQIA Competencies Taskforce, 2013; ASCA, 2016a), many PSCs never receive the training necessary to effectively serve trans students (Bidell, 2012; O’Hara et al., 2013; Salpietro et al., 2019). Salpietro and colleagues (2019) reported that counselor incompetence was related to a lack of rigorous training that attends to family systems, intersectionality, and medical issues through gender-affirming therapies (i.e., blockers, hormones, or surgeries). These researchers indicated a need for comprehensive, standardized, and thorough formal training (i.e., graduate school) and informal professional development opportunities. These findings are consistent with Shi and Doud (2017), who recommended PSCs specifically take advantage of conferences and workshops to supplement formal educational curricula. The Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network (GLSEN) conducted a survey that reported about 81% of school mental health professionals received “little to no competency training in their graduate programs related to working with [trans] populations,” and about 74% of participants rated their graduate training programs as “fair or poor” in preparing them for work with trans students (GLSEN et al., 2019, p. xviii). GLSEN and other professional organizations additionally reported about two-thirds of school professionals do not feel prepared to work with trans students (GLSEN et al., 2019). Although there are some professional development opportunities, such as those offered through the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), the HRC, and the Society for Sexual, Affectional, Intersex, and Gender-Expansive Identities (SAIGE), there is still a lack of concrete training within graduate programs and through fieldwork experiences and an overall lack of accessible, professional trainings. There is a clear need for increased attention to trans issues in formal educational programs and professional development offerings.

Purpose of the Study and Research Questions

This study examines factors that contribute to PSC competence in working with trans students in K–12 public schools. We highlight the need for PSCs and counselor education training programs to better focus on and support trans students. More specifically, we examine the following PSC factors: (a) the PSC’s GI, (b) whether the PSC has received postgraduate training on trans issues or populations, (c) whether the PSC has worked with self-identified trans students, and (d) whether the PSC knows someone who identifies as trans outside of the school setting.

PSC Gender Identity

Researchers recommend that special attention is given within a category of interest (i.e., gender identity) to historically marginalized groups, encouraging counselor-researchers to view all samples “in terms of their particularity and to attend to diversity within samples” (Cole, 2009, p. 176). We were intentional in using PSC GI demographic factors in data analysis, attending to diversity among PSC gender identities, as research indicates there may be relationships between counselor GI, privilege and oppression, and multicultural counselor competence (Cole, 2009). Culturally competent counselors engage in self-reflection, examine their own biases and stereotypes, consider how their positions of privilege or oppression impact the therapeutic alliance, and deliver culturally responsive counseling interventions.

Postgraduate Training Addressing Trans Issues

Researchers note that graduate programs in counselor education are not adequately preparing school counseling students to work with trans students (Bidell, 2012; Farmer et al., 2013; Frank & Cannon, 2010; GLSEN et al., 2019; O’Hara et al., 2013) and that much of the awareness, knowledge, and skills gained in working with this population are result of counselors’ self-seeking professional trainings, education, and workshops that are focused on trans issues and students (Salpietro et al., 2019; Shi & Doud, 2017).

Professional Experiences With Trans Students

O’Hara and colleagues (2013) reported no significance on scores of competence in working with trans clients between counseling students who completed practicum or internship and those who did not. In the present study, our variable relates to PSCs who have already graduated, reflecting on their professional tenure as PSCs, and if these experiences provided opportunities to work with trans students.

Personal Relationships With Trans People

O’Hara and colleagues (2013) reported that participants in their study identified informal sources as necessary for gaining trans-affirming knowledge and skills, such as “exposure to or personally knowing someone who [is trans]” (p. 246). Research supports the concept that increasing affirming attitudes and mitigating negative attitudes and beliefs toward trans individuals can be accomplished by exposure and intentional engagement in fostering personal and professional relationships with trans people (Salpietro et al., 2019; Simons, 2021). In forming relationships with trans people, we can listen to and learn from the lived experiences of this community, examine our own biases, and position ourselves as supportive allies, personally and professionally.

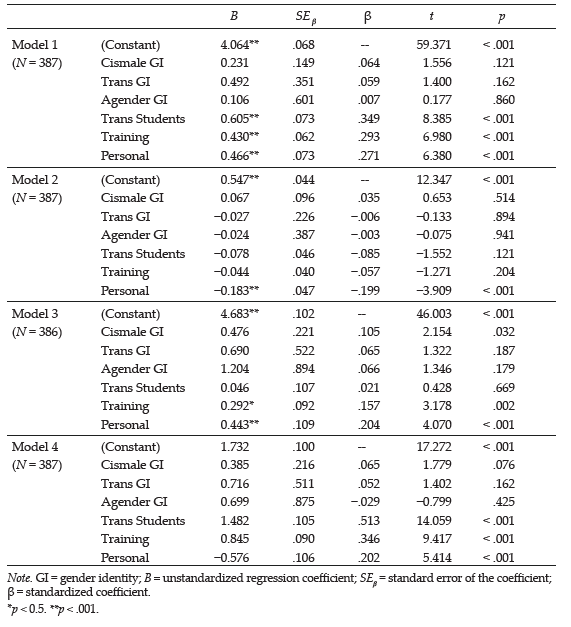

Research Questions

With these factors in mind, the following research questions were identified:

- What is the relationship between PSC factors (GI, postgraduate training, PSC work with trans students, and PSC personally knowing someone who is trans) and levels of PSC self-perceived competence in working with trans students in schools?

- What is the relationship between PSC factors (GI, postgraduate training, PSC work with trans students, and PSC personally knowing someone who is trans) and PSC awareness in working with trans students in schools?

- What is the relationship between PSC factors (GI, postgraduate training, PSC work with trans students, and PSC personally knowing someone who is trans) and PSC knowledge in working with trans students in schools?

- What is the relationship between PSC factors (GI, postgraduate training, PSC work with trans students, and PSC personally knowing someone who is trans) and PSC skills in working with trans students in schools?

We hypothesized there would be a statistically significance difference (p > .05) between PSC factors (GI, postgraduate training, PSC work with trans students, and PSC personally knowing someone who is trans) and levels of PSC self-perceived competence in working with trans students in schools. More specifically, we hypothesized that cisfemale PSCs who have had postgraduate training on trans issues, who have worked with trans students, and who personally know someone who is trans, would report higher scores in measures of awareness, knowledge, skills, and overall competence. Cisgender (cis) refers to someone who experiences congruence between their sex assigned at birth and their GI. Research demonstrates that cismales may express more negative attitudes and hold restrictive views toward queer and trans people when compared with cisfemales (Landén & Innala, 2000; Norton & Herek, 2012).

Method

Participants

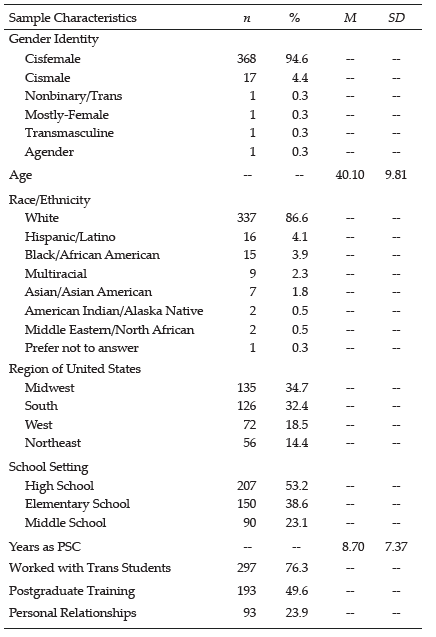

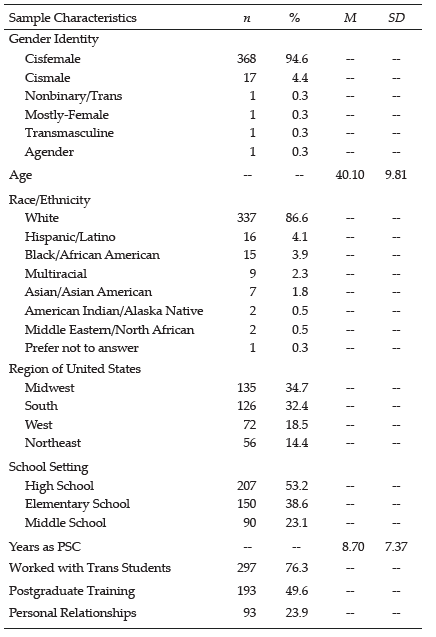

With an anticipated medium effect size of 0.15, a desired statistical power level of 0.95, and desired probability level of 0.05 (Israel, 2013), we determined an appropriate minimum sample size for the proposed study was 120 PSCs. Initially, 499 responses were recorded. Of those, 110 were incomplete or had missing data, yielding a total of 389 fully completed surveys. Participants in this study (N = 389) were PSCs with a valid school counseling license working in a public school setting, from kindergarten through 12th grade, in the United States. Participant demographic information can be found in Table 1.

Table 1

Demographic Characteristics of Professional School Counselors (PSCs)

Procedures

For ease of use and accuracy of representation, we used probability sampling, more specifically, a simple random sample selection process (Creswell, 2013). Upon approval by the IRB, we posted a series of three recruitment letters (with 2 weeks between each posting) to PSCs through an online professional forum, ASCA Scene. We also posted our recruitment letter on ASCA Aspects, a monthly e-newsletter. Data were collected over a period of 6 weeks. PSCs who elected to participate were directed to the electronic informed consent document and the survey.

Instrumentation

Demographic Questionnaire

Participants completed a questionnaire with write-in options for both age and gender and forced-choice responses to gather racial-ethnic identity, years working as a licensed school counselor, the region in which they practiced, and grade levels in which the participants worked. Our four independent variables were collected through the demographic questionnaire. Participants indicated their experiences, if any, with trans students, experiences with postgraduate training on trans issues, and personal relationships with trans people.

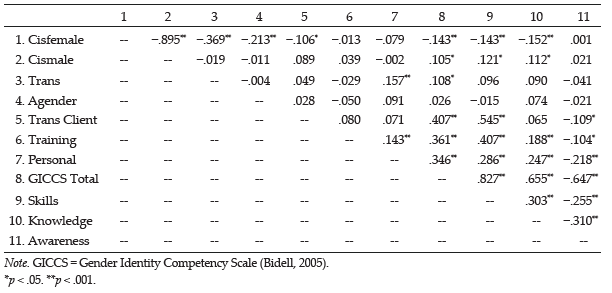

Gender Identity Counselor Competency Scale

The Gender Identity Counselor Competency Scale (GICCS), a revised version of the Sexual Orientation Counselor Competency Scale (Bidell, 2005), was used to assess PSC competence, the dependent variable in the study. This is the instrument best suited for intended measurement of self-perceived competence (Bidell, 2012; O’Hara et al., 2013). Bidell (2005) developed the instrument based on Sue and colleagues’ (1992) research of multicultural counseling competencies, with the domains of attitudinal awareness, knowledge, and skills. Bidell (2005) reported the Cronbach’s alpha of .90, with subscale scores for internal consistency of .88 for the Awareness subscale, .71 for the Knowledge subscale, and .91 for the Skills subscale (Bidell, 2005, 2012). Test-retest reliability for the overall instrument was found to be .84, with .85 for the Awareness subscale, .84 for the Knowledge subscale, and .83 for the Skills subscale (Bidell, 2005). The GICCS is a 29-item self-report assessment on a 7-point Likert scale (where 1 is not at all true and 7 is totally true). Examples of questions include: “I have received adequate clinical training and supervision to counsel transgender clients” and “The lifestyle of a transgender client is unnatural or immoral” (O’Hara et al., 2013, p. 242). Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was .70, adequate for our analysis.

Awareness Subscale. The Awareness subscale consists of 10 items focused on counselors’ attitudinal awareness and prejudice about trans clients, including statements like “It would be best if my clients viewed a [cisgender] lifestyle as ideal” and “I think that my clients should accept some degree of conformity to traditional [gender] values” (Bidell, 2005, p. 273). Cronbach’s alpha for the Awareness subscale has been reported as .88 (Bidell, 2005) and was .89 in the present sample. Self-awareness and reflection are critical skills for counselors in examining deeply held biases and beliefs and in asking culturally responsive questions to strengthen the therapeutic alliance.

Knowledge Subscale. This subscale of the GICCS consists of eight items focused on counselors’ experiences and skills with trans clients, including statements like “I am aware that counselors frequently impose their values concerning [gender] upon [trans] clients” and “I am aware of institutional barriers that may inhibit [trans] clients from using mental health services” (Bidell, 2005, p. 273). Cronbach’s alpha for the Knowledge subscale was reported as .76 (Bidell, 2005), and was .73 in the present sample. Counselors who impose their own values on a client may cause rifts in the therapeutic alliance and could potentially even harm clients.

Skills Subscale. This subscale of the GICCS consists of 11 items focused on counselors’ experiences and skills with trans clients, including statements like “I have experience counseling [trans male] clients” and “I have received adequate clinical training and supervision to counsel [trans] clients” (Bidell, 2005, p. 273). Cronbach’s alpha for the Skills subscale was reported as .91 (Bidell, 2005) but was .75 in the present sample. Counselors working with trans students need to understand the importance of evolving language and terminologies; utilize affirmative, celebratory, and liberating counseling; and have knowledge of and connection to medical providers who support gender-affirming interventions.

Data Analysis Procedures

Data Cleaning

We first screened the data to ensure it was usable, reliable, and valid to proceed with statistical analyses. We continued data cleaning by coding the demographic variable of GI 1 through 4: cisfemale (1); cismale (2); nonbinary, trans, and/or genderqueer (3); and agender (4). Racial-ethnic identities were coded 1 through 10: American Indian or Alaska Native (1); Asian or Asian American (2); Black or African American (3); Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish Origin (4); Middle Eastern or North African (5); Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (6); White (7); Some Other Race, Ethnicity, or Origin (8); Prefer Not to Answer (9); and Multiracial Identity (10). PSC location was also coded 1 through 6: Midwest (1), Northeast (2), South (3), West (4), Puerto Rico or other U.S. Territories (5), and Other (6). Last of the demographic variables, we coded PSC School Level 1 through 4: Elementary (1), Middle School (2), High School (3), and Other (4). In addition, we cleaned variables highlighting PSC professional and personal training and experiences with trans persons. The first variable was dummy coded to reflect participants who had worked with trans students (1; n = 297, 76.3%) and participants who indicated not working with trans students (0; n = 92, 23.7%). The next variable, PSC postgraduate training, was dummy coded for use in data analyses, reflecting those who indicated they engaged in postgraduate training (1; n = 193, 49.6%) and participants who indicated they did not engage in postgraduate training (0; n = 196, 50.4%). The final variable was dummy coded to reflect participants who know someone who is trans outside of the school setting (1; n = 93, 23.9%) and those participants who do not know someone who is trans outside of the school setting (0; n = 296, 76.1%). Per Bidell (2005), we started by reverse scoring coded GICCS items and created new variables for the GICCS total mean score, attitudinal Awareness, Skills, and Knowledge subscales.

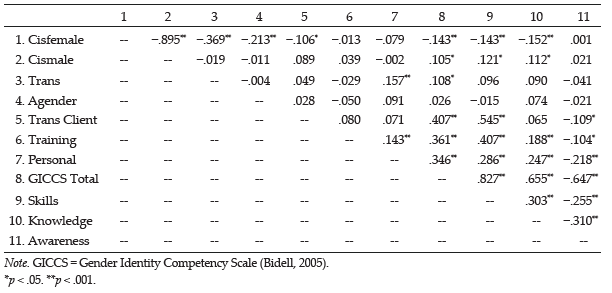

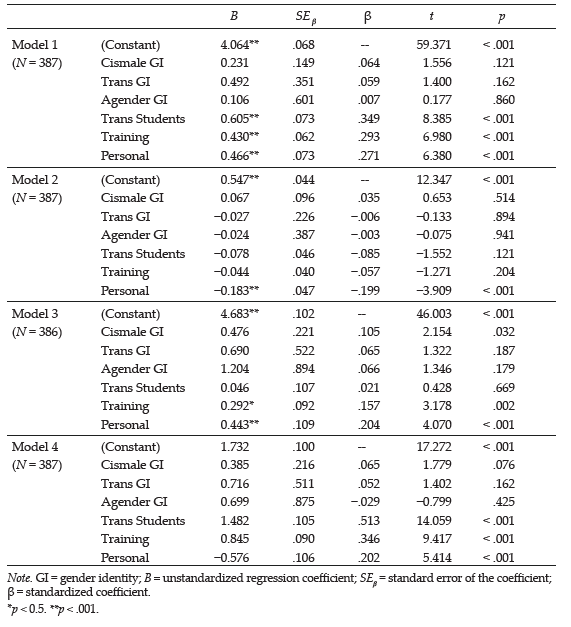

Data Analysis

Post–data cleaning, we entered all the data from the demographic questionnaire and the GICCS into SPSS 26. To best answer the research questions, we used a series of standard multiple regression analyses to determine “the existence of a relationship and the extent to which variables are related, including statistical significance” (Sheperis et al., 2017, p. 131). Although multiple regression analysis can be used in prediction studies, it can also be used to determine how much of the variation in a dependent variable is explained by the independent variables, which is what we intended to measure (Johnson, 2001). Our independent variables were four categorical variables measured by our demographic questionnaire: PSC GI, postgraduate training, PSC work with trans students, and PSC personal relationships with someone who is trans. Our dependent variable was school counselor competence in working with trans students, as measured by the GICCS (Bidell, 2005).