Feb 26, 2021 | Volume 11 - Issue 1

David E. Jones, Jennifer S. Park, Katie Gamby, Taylor M. Bigelow, Tesfaye B. Mersha, Alonzo T. Folger

Epigenetics is the study of modifications to gene expression without an alteration to the DNA sequence. Currently there is limited translation of epigenetics to the counseling profession. The purpose of this article is to inform counseling practitioners and counselor educators about the potential role epigenetics plays in mental health. Current mental health epigenetic research supports that adverse psychosocial experiences are associated with mental health disorders such as schizophrenia, anxiety, depression, and addiction. There are also positive epigenetic associations with counseling interventions, including cognitive behavioral therapy, mindfulness, diet, and exercise. These mental health epigenetic findings have implications for the counseling profession such as engaging in early life span health prevention and wellness, attending to micro and macro environmental influences during assessment and treatment, collaborating with other health professionals in epigenetic research, and incorporating epigenetic findings into counselor education curricula that meet the standards of the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP).

Keywords: epigenetics, mental health, counseling, prevention and wellness, counselor education

Epigenetics, defined as the study of chemical changes at the cellular level that alter gene expression but do not alter the genetic code (T.-Y. Zhang & Meaney, 2010), has emerging significance for the profession of counseling. Historically, people who studied abnormal behavior focused on determining whether the cause of poor mental health outcomes was either “nature or nurture” (i.e., either genetics or environmental factors). What we now understand is that both nature and nurture, or the interaction between the individual and their environment (e.g., neglect, trauma, substance abuse, diet, social support, exercise), can modify gene expression positively or negatively (Cohen et al., 2017; Suderman et al., 2014).

In the concept of nature and nurture, there is evidence that psychosocial experiences can change the landscape of epigenetic chemical tags across the genome. This change in landscape influences mental health concerns, such as addiction, anxiety, and depression, that are addressed by counseling practitioners (Lester et al., 2016; Provençal & Binder, 2015; Szyf et al., 2016). Because the field of epigenetics is evolving and there is limited attention to epigenetics in the counseling profession, our purpose is to inform counseling practitioners and educators about the role epigenetics may play in clinical mental health counseling.

Though many counselors and counselor educators may have taken a biology class that covered genetics sometime during their professional education, we provide pedagogical scaffolding from genetics to epigenetics. Care was taken to ensure accessibility of information for readers across this continuum of genetics knowledge. Much of what we offer below on genetics is putative knowledge, as we desire to establish a foundation for the reader in genetics so they may be able to have a greater understanding of epigenetics and a clearer comprehension of the implications we offer leading to application in counseling. We suggest readers review Brooker (2017) for more detailed information on genetics. We will present an overview of genetics and epigenetics, an examination of mental health epigenetics, and implications for the counseling profession.

Genetics

Genetics is the study of heredity (Brooker, 2017) and the cellular process by which parents pass on biological information via genes. The child inherits genetic coding from both parents. One can think of these parental genes as a recipe book for molecular operations such as the development of proteins, structure of neurons, and other functions across the human body. This total collection of the combination of genes in the human body is called the genome or genotype. The presentation of observable human traits (e.g., eye color, height, blood type) is called the phenotype. Phenotypes can be seen in our clinical work through behavior (e.g., self-injury, aggression, depression, anxiety, inattentiveness).

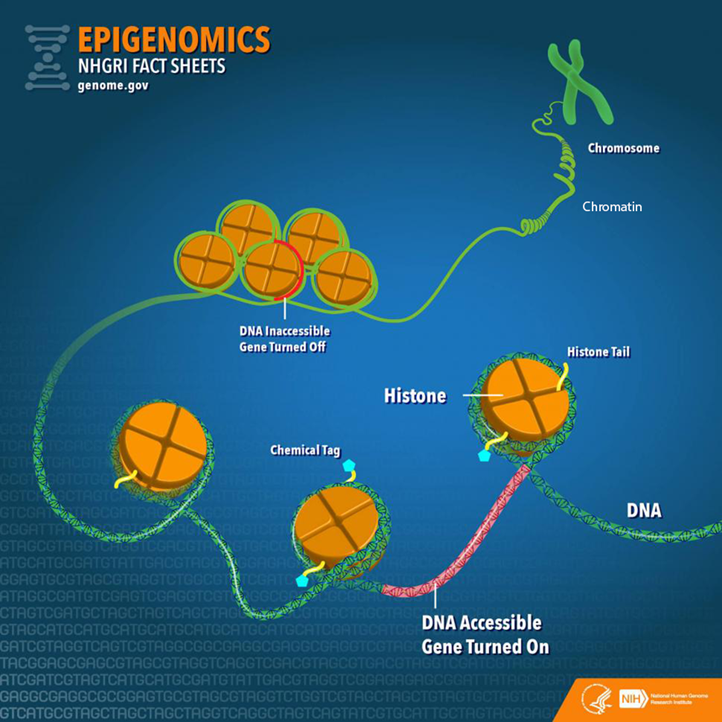

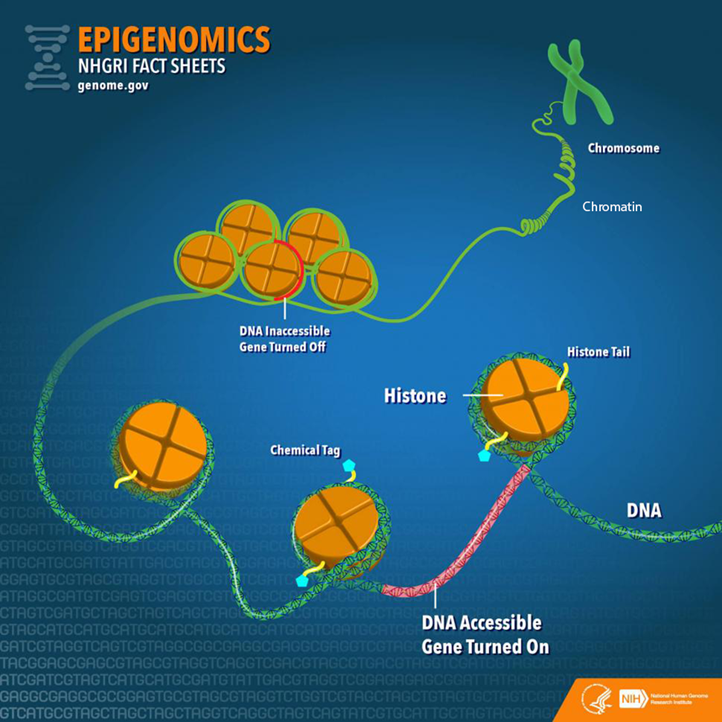

Before going further, it is important to establish a fundamental understanding of genetics by examining the varied molecular components and their relationships (Figure 1). Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is a long-strand molecule that takes the famous double helix or ladder configuration. DNA is made up of four chemical bases called adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C), and thymine (T). These form base pairs—A with T and C with G—creating a nucleic acid. The DNA is also wrapped around a specialized protein called a histone. The collection of DNA wrapped around multiple histones is called the chromatin. This wrapping process is essential for the DNA to fit within the cell nucleus. Finally, as this chromatin continues to grow, it develops a structure called a chromosome. Within every human cell nucleus, there are 23 chromosomes from each parent, totaling 46 chromosomes.

Figure 1

Gene Structure and Epigenetics

From “Epigenomics Fact Sheet,” by National Human Genome Research Institute, 2020

(https://www.genome.gov/about-genomics/fact-sheets/Epigenomics-Fact-Sheet). In the public domain.

Beyond the chromosomes, chromatin, histones, DNA, and genes, there is another key component in genetics: ribonucleic acid (RNA). RNA can be a cellular messenger that carries instructions from a DNA sequence (specific genes) to other parts of the cell (i.e., messenger RNA [mRNA]). RNA can come in several other forms as well, including transfer RNA (tRNA), microRNA (miRNA), and non-coding RNA (ncRNA). In the sections below, we elaborate on mRNA and tRNA and their impact on the genetic processes. Later in the epigenetics section, we provide fuller details on miRNA and ncRNA.

Besides the aforementioned biological aspects, it is important to understand that a child inherits genes from both parents, but they are not exactly the same genes, (i.e., alternative forms of the same gene may have differing expression). Different versions of the same gene are called alleles. Variation in an allele is one reason why we see phenotypic variation between our clients—height, weight, eye color—and this variation can contribute to mental disease susceptibility. Although there are many potential causes of poor mental health, family history is often one of the strongest risk factors because family members most closely represent the unique genetic and environmental interactions that an individual may experience. We also see this as a function of intergenerational epigenetic effects, which are covered later in this paper.

Transcription and Translation

Now that we have provided a foundation of the genetic components, we move toward the primary two-stage processes of genetics: transcription and translation (Brooker, 2017). The first step in the process of gene expression is called transcription. Transcription occurs when a sequence of DNA is copied using RNA polymerase (“ase” notes that it is an enzyme) to make mRNA for protein synthesis. We can liken transcription to the process of someone taking down information from a client’s voicemail message. In this visualization, DNA is the caller, the person writing down the message is the RNA polymerase, and the actual written message is the RNA.

A particular section of a gene, called a promotor region, is bound by the RNA polymerase (Brooker, 2017). The RNA polymerase acts like scissors to separate the double-stranded DNA helix into two strands. One of the strands, called the template, is where the RNA polymerase will read the DNA code A to T, and G to C to build mRNA. There are other modifications that must occur in eukaryotic cells such as splicing introns and exons. In short, sections of unwanted DNA, called introns, are removed by the process of splicing, and the remaining DNA codes are connected back together (exons).

Now that the mRNA has been created by the process of transcription, the next step is for the mRNA to build a protein necessary for the main functions of the body, in a process known as translation (Brooker, 2017). Here, translation is the process in which tRNA decodes or translates the mRNA into a protein in a mobile cellular factory called the ribosome. It is translating the language of a DNA sequence (gene) into the language of a protein. To do this, the tRNA uses a translation device called an anticodon. This anticodon links to the mRNA-based pairs called a codon. A codon is a trinucleotide sequence of DNA or RNA that corresponds to a specific amino acid, or building block of a protein. This process then continues to translate and connect many amino acids together until a polypeptide (a long chain of amino acids) is created. Later, these polypeptides join to form proteins. Depending on the type of cell, the protein may function in a variety of ways. For example, the neuron has several proteins for its function, and different proteins are used for memory, learning, and neuroplasticity.

Epigenetics

There is a wealth of research conducted on genetics, yet the understanding of epigenetics is more limited when focusing on mental health (Huang et al., 2017). Though the term epigenetics has been around since the 1940s, the “science” of epigenetics is in its youth. Epigenetic research in humans has grown in the last 10 years and continues to expand rapidly (Januar et al., 2015). The key concept for counselors to remember about epigenetics is that epigenetics supports the idea of coaction. Factors present in the client’s external environment (e.g., stress from caregiver neglect, foods consumed, drug intake like cigarettes) influence the expression of their genes (transcription and translation) and thus cell activity and related behavioral phenotypes. In the sections below, we will dive deeper into the understanding of epigenetic mechanisms and define key terms including epigenome, chromatin, and chemical modifications.

To start, the more formal definition of epigenetics is the differentiation of gene expression via chemical modifications upon the epigenome that do not alter the genetic code (i.e., the DNA sequence; Szyf et al., 2007). The epigenome, which is composed of chromatin (the combination of DNA and protein forming the chromosomes) and modification of DNA by chemical mechanisms (e.g., DNA methylation, histone modification), programs the process of gene expression (Szyf et al., 2007). The epigenome differs from the genome in that the chemical actions or modifications are on the outside of the genome (i.e., the DNA) or “upon” the genome. Specifically, epigenetic processes act “upon” the genome, which may open or close the chromatin to various degrees to govern access for reading DNA sequences (Figure 1). When the chromatin is opened, transcription and translation can take place; however, when the chromatin is closed, gene expression is silenced (Syzf et al., 2007).

It is important for counselors to conceptualize their client’s psychosocial environment in conjunction with the observed behavioral phenotypes, in that the client’s psychosocial environment may have partially mediated epigenetic expression (Januar et al., 2015). For example, with schizophrenia, a client’s adverse environment (e.g., early childhood trauma) influences the epigenome, or gene expression, which may contribute up to 60% of this disorder’s development (Gejman et al., 2011). Other adverse environmental influences have been associated with the development of schizophrenia, including complications during client’s prenatal development and birth, place and season of client’s birth, abuse, and parental loss (Benros et al., 2011). As we highlight below, epigenetic mechanisms (e.g., DNA methylation) may mediate between these environmental influences and genes with outcomes like schizophrenia (Cariaga-Martinez & Alelú-Paz, 2018; Tsankova et al., 2007).

Epigenetic Mechanisms

There are a variety of chemical mechanisms or tags that change the chromatin structure (either opening for expression or closing to inhibit expression). Some of the most investigated mechanisms for changes in chromatin structure are DNA methylation, histone modification, and microRNA (Benoit & Turecki, 2010; Maze & Nestler, 2011).

DNA Methylation. Methylation is the most studied epigenetic modification (Nestler et al., 2016). It occurs when a methyl group binds to a cytosine base (C) of DNA to form 5-methylcytosine. A methyl group is three hydrogens bonded to a carbon, identified as CH3. Most often, the methyl group is attached to a C followed by a G, called a CpG. These methylation changes are carried out by specific enzymes called DNA methyltransferase. These enzymes add the methyl group to the C base at the CpG site.

Methylation was initially considered irreversible, but recent research has shown that DNA methylation is more stable compared to other chemical modifications like histone modification and is therefore reversible (Nestler et al., 2016). This DNA methylation adaptability evidence is important, conceivably supporting counseling efficacy across the life span. If methylation is indeed reversible beyond 0 to 5 years of age, counseling efforts hold promise to influence mental health outcomes across the life span.

Beyond noted stability, DNA methylation is also important in that it is tissue-specific, meaning it assists in cell differentiation; it may regulate gene expression up or down and is influenced by different environmental exposures (Monk et al., 2012). For example, DNA methylation represses specific areas of a neuron’s genes, thus “turning off” their function. This stabilizes the cell by preventing any tissue-specific cell differentiation and inhibits the neuron from changing into another cell type (Szyf et al., 2016), such as becoming a lung cell later in development.

When looking at up- or downregulation, Oberlander et al. (2008) provided an example from a study using mice. When examining attachment style in mice, they found that decreased quality of mothering to offspring increased risk of anxiety, in part, because of the methylation at the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) gene and fewer GR proteins produced by the hippocampus. This change may lead to lifelong silencing or downregulation with an increased risk of anxiety to the mouse over its life span. Stevens et al. (2018) also established a link between diet, epigenetics, and DNA methylation. They found an epigenetic connection between poor dietary intake with increased risk of behavioral problems and poor mental health outcomes such as autism. The authors also remarked that further investigation is required for a clearer picture of this link and potential effects.

Histone Modification. Another process that has been extensively researched is post-translational histone modification, or changes in the histone after the translation process. The most understood histone modifications are acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation (Nestler et al., 2016). Acetylation, the most common post-translational modification, occurs by adding an acetyl group to the histone tail, such as the amino acid lysine. The enzymes responsible for histone acetylation are histone acetyltransferases or HATs (Haggarty & Tsai, 2011). Conversely, histone deacetylases (HDACs) are enzymes that remove acetyl groups (Saavedra et al., 2016). The acetylation process promotes gene expression (Nestler et al., 2016).

Through histone methyltransferases (HMTs), histone methylation increases methylation, thereby reducing gene expression. Histone demethylases (HDMs) remove methyl groups to increase gene activity. Phosphorylation can increase or decrease gene expression. Overall, there are more than 50 known histone modifications (Nestler et al., 2016).

From a counseling perspective, it is important to note that histone modification is flexible. Unlike DNA methylation, which is more stable over a lifetime, histone modifications are more transient. To illustrate, if an acetyl group is added to a histone, it may loosen the binding between the DNA and histone, increasing transcription and thereby allowing gene expression across the life span (Nestler et al., 2016). Such acetylation processes have been found in maternal neglect to offspring (early in the life span) and mindfulness practices in adult clients (Chaix et al., 2020; Devlin et al., 2010). Yet, although histone modification can be changed across the life span (Nestler et al., 2016), it is still important for counselors to recognize the importance of early counseling interventions because of how highly active epigenetics mechanisms (e.g., DNA methylation) are in children 0 to 5 years of age.

MicroRNA. Beyond histone modification, another known mechanism is microRNA (miRNA), which is the least understood and most recently investigated epigenetic mechanism when compared to DNA methylation and histone modification (Saavedra et al., 2016). miRNA is one type of non-coding RNA (ncRNA), or RNA that is changed into proteins. Around 98% of the genome does not code for proteins, leading to a supporting hypothesis that ncRNAs play a significant role in gene expression. For example, humans and chimpanzees share 98.8% of the same DNA code. However, epigenetics and specifically ncRNA contribute to the wide phenotypic variation between the species (Zheng & Xiao, 2016). Further, Zheng and Xiao (2016) estimated that miRNA regulates up to 60% of gene expression.

miRNA has also been found to suppress and activate gene expression at the levels of transcription and translation (Saavedra et al., 2016). miRNAs affect gene expression by directly influencing mRNA. Specifically, the miRNA may attach to mRNA and “block” the mRNA from creating proteins or it may directly degrade mRNA. This then decreases the surplus of mRNA in the cell. If the miRNA binds partially with the mRNA, then it inhibits protein production; but if it binds completely, it is marked for destruction. Once the mRNA is identified for destruction, other proteins and enzymes are attracted to the mRNA, and they degrade the mRNA and eliminate it (Zheng & Xiao, 2016). Moreover, when compared to DNA methylation, which may be isolated to a single gene sequence, miRNA can target hundreds of genes (Lewis et al., 2005). Researchers have discovered that miRNA may mediate anxiety-like symptoms (Cohen et al., 2017).

Human Development and Epigenetics

Over the life of an individual, there are critical or sensitive periods in which epigenetic modifications are more heavily influenced by environmental factors (Mulligan, 2016). Early life (ages 0 to 5 years) appears to be one of the most critical time periods when epigenetics is more active. An example of this is the Dutch Famine of 1944–45, also known as the Dutch Hunger Winter (Champagne, 2010; Szyf, 2009). The Nazis occupied the Netherlands and restricted food to the country, bringing about a famine. The individual daily caloric intake estimate varied between 400 and 1800 calories at the climax of the famine. Most notably, women who gave birth during this time experienced the impact of low maternal caloric intake, which impacted their child and the child’s health outcomes into adulthood. One discovery was that male children had a higher risk of adulthood obesity if their famine exposure occurred early in gestation versus a male fetus who experienced famine in late gestation. Findings suggested that fetuses who experienced restricted caloric intake during the development of their autonomic nervous system may have an increased risk of heart disease in adulthood. The findings of epigenetic mechanisms at work between mother and child during a famine are flagrant enough, yet epigenetic researchers have also discovered that epigenetic tags carry across generations, called genomic imprinting (Arnaud, 2010; Yehuda et al., 2016; T.-Y. Zhang & Meaney, 2010).

Genomic imprinting can be defined as the passing on of certain epigenetic modifications to the fetus by parents (Arnaud, 2010). It is allele-specific, and approximately half of the imprinting an offspring receives is from the mother. The imprinting mechanism marks certain areas, or loci, of offspring’s genes as active or repressed. For instance, the loci may exhibit increased or decreased methylation.

An imprinting example is evident in the IGF-2 (insulin-like growth factor II) gene and those fetuses exposed to the Dutch Hunger Winter (Heijmans et al., 2008). Sixty years after the famine, a decrease in DNA methylation on IGF-2 was found in adults with fetal exposure during the famine compared to their older siblings. Researchers also found these intergenerational imprinting effects associated with the grandchildren of women who were pregnant during the Dutch Hunger Winter. Similar imprinting is also apparent in Holocaust survivors (Yehuda et al., 2016) and children born to mothers who experienced PTSD from the World Trade Center collapse of 9/11 (Yehuda et al., 2005). These imprinting mechanisms are important for counselors to understand in that we see the interplay between the client and the environment across generations. The client becomes the embodiment of their environment at the cellular level. This is no longer the dichotomous “nature vs. nurture” debate but the passing on of biological effects from one generation to another through the interplay of nature and nurture.

Epigenetics and Mental Health Disorders

Now we turn our focus to the influence of epigenetics on the profession of counseling. What we do know is that epigenetic mechanisms, (e.g., DNA methylation, histone modifications, miRNA) are associated with various mental health disorders. It is hypothesized that epigenetics contributes to the development of mental disorders after exposure to environmental stressors, such as traumatic life events, but it may also have positive effects based on salutary environments (Syzf, 2009; Yehuda et al., 2005). We will review only those mental health epigenetic findings that have significant implications relative to clinical disorders such as stress, anxiety, childhood maltreatment, depression, schizophrenia, and addiction. We will also offer epigenetic outcomes associated with treatment, including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT; Roberts et al., 2015), meditation (Chaix et al., 2020), and antidepressants (Lüscher & Möhler, 2019).

Stress and Anxiety

Stress, especially during early life stages, causes long-term effects for neuronal pathways and gene expression (Lester et al., 2016; Palmisano & Pandey, 2017; Perroud et al., 2011; Roberts et al., 2015; Szyf, 2009; T.-Y. Zhang & Meaney, 2010). Currently, research supports the mediating effects of stress on epigenetics through DNA methylation, especially within the gestational environment (Lester & Marsit, 2018). DNA methylation has been associated with upregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, increasing anxiety symptoms (McGowan et al., 2009; Oberlander et al., 2008; Romens et al., 2015; Shimada-Sugimoto et al., 2015; Tsankova et al., 2007). DNA methylation has also been linked with increased levels of cortisol for newborns of depressed mothers. This points to an increased HPA stress response in the newborn (Oberlander et al., 2008). Ouellet-Morin et al. (2013) also looked at DNA methylation and stress. They conducted a longitudinal twin study on the effect of bullying on the serotonin transporter gene (SERT) for monozygotic twins and found increased levels of SERT DNA methylation in victims compared to their non-bullied monozygotic co-twin. Finally, Roberts et al. (2015) examined the effect of CBT on DNA methylation for children with severe anxiety, specifically testing changes in the FKBP5 gene. Although the results were not statistically significant, they may be clinically significant. Research participants with a higher DNA methylation on the FKBP5 gene had poorer response to CBT treatment.

Beyond DNA methylation, other researchers have investigated miRNA and its association with stress and anxiety. A study by Harris and Seckl (2011) found that fetal rodents with increased exposure to maternal cortisol suffered from lower birth weights and heightened anxiety. Similarly, Cohen et al. (2017) investigated anxiety in rats for a specific miRNA called miR-101a-3p. The researchers selectively bred rats, one group with low anxiety and the other with high anxiety traits. They then overexpressed miR-101a-3p in low-anxiety rats to see if that would induce greater expressions of anxiety symptomatology. The investigators observed increased anxiety behaviors when increasing the expression of miR-101a-3p in low-anxiety rats. The researchers postulated that miRNA may be a mediator of anxiety-like behaviors. Finally, paternal chronic stress in rats has been associated with intergenerational impact on offspring’s HPA axis with sperm cells having increased miRNAs, potentially indicating susceptibility of epigenetic preprogramming in male germ cells post-fertilization (Rodgers et al., 2013). The evidence suggests that paternal stress reprograms the HPA stress response during conception. This reprogramming may begin a cascading effect on the offspring’s HPA, creating dysregulation that is associated with disorders like schizophrenia, autism, and depression later in adulthood.

Though some researchers have indicated a negative association between anxiety and epigenetics, others have found positive effects between epigenetics and anxiety. A seminal study by Weaver et al. (2005) illustrated the flexibility of an offspring’s biological system to negative and positive environmental cues. Weaver et al. looked at HPA response of rodent pups who received low licking and grooming from their mother (a negative environmental effect) who exhibited higher HPA response to environmental cues in adulthood. Epigenetically, they found lower DNA methylation in a specific promotor region in these adult rodents. They hypothesized that they could reverse this hypomethylation by giving an infusion of methionine, an essential amino acid that is a methyl group donor. They discovered the ability to reverse low methylation, which improved the minimally licked and groomed adult rodents’ response to stress. This connects with counseling in that epigenetic information is not set for life but reversible through interventions such as diet.

Others have investigated mindfulness and its epigenetic effects on stress. Chaix et al. (2020) looked at DNA methylation at the genome level for differences between skilled meditators who meditated for an 8-hour interval compared to members of a control group who engaged in leisure activities for 8 hours. The control group did not have any changes in genome DNA methylation, but the skilled meditators showed 61 differentially methylated sites post-intervention. This evidence can potentially support the use of mindfulness with our clients as an intervention for treatment of stress.

Childhood Maltreatment

Childhood maltreatment includes sexual abuse, physical abuse and/or neglect, and emotional abuse and/or neglect. Through this lens, Suderman et al. (2014) examined differences in 45-year-old males’ blood samples between those who experienced abuse in childhood and those who did not, with the aim of determining whether gene promoter DNA methylation is linked with child abuse. After 30 years, the researchers found different DNA methylation patterns between abused versus non-abused individuals and that a specific hypermethylation of a gene was linked with the adults who experienced child abuse. Suderman et al. (2014) believed that adversity, such as child abuse, reorganizes biological pathways that last into adulthood. These DNA methylation differences have been associated with biological pathways leading to cancer, obesity, diabetes, and other inflammatory paths.

Other researchers have also found epigenetic interactions at CpG sites predicting depression and anxiety in participants who experienced abuse. Though these interactions were not statistically significant (Smearman et al., 2016), increased methylation at specific promoter regions was discovered (Perroud et al., 2011; Romens et al., 2015). Furthermore, in a hallmark study, McGowan et al. (2009) discovered that people with child abuse histories who completed suicide possessed hypermethylation of a particular promotor region when compared to controls. Perroud et al. (2011) noted that frequency, age of onset, and severity of maltreatment correlated positively with increased methylation in adult participants suffering from borderline personality disorder, depression, and PTSD. Yehuda et al. (2016) reported that in a smaller subset of an overall sample of Holocaust survivors, the impact of trauma was intergenerationally associated with increased DNA methylation. Continued study of these particular regions may provide evidence of DNA methylation as a predictor of risk in developing anxiety or depressive disorders.

Major Depressive Disorder

Most studies of mental illness, genetics, and depression have used stress animal models. Through these models, histone modification, chromatin remodeling, miRNA, and DNA methylation mechanisms have been found in rats and mice (Albert et al., 2019; Nestler et al., 2016). When an animal or human experiences early life stress, epigenetic biomarkers may serve to detect the development or progression of major depressive disorder (Saavedra et al., 2016). Additionally, histone modification markers may also indicate an increase in depression (Tsankova et al., 2007; Turecki, 2014). Beyond animal models, Januar et al. (2015) found that buccal tissue in older patients with major depressive disorder provided evidence that the BDNF gene modulates depression through hypermethylation of specific CpGs in promoter regions.

Lastly, certain miRNAs may serve as potential biomarkers for major depressive disorder. miRNA may be used in the pharmacologic treatment of depressive disorders (Saavedra et al., 2016). Tsankova et al. (2007) and Saavedra et al. (2016) noted that certain epigenetic mechanisms that influence gene expression may be useful as antidepressant treatments. Medication may induce neurogenesis and greater plasticity in synapses through upregulation and downregulation of miRNAs (Bocchio-Chiavetto et al., 2013; Lüscher & Möhler, 2019). This points to the potential use of epigenetic “engineering” for reducing depression progression and symptomology where a counselor could refer a client for epigenetic antidepressant treatments.

Maternal Depression

Maternal prenatal depression may program the postnatal HPA axis in infants’ responses to the caretaking environment. Such programming may result in decreased expression of certain genes associated with lesser DNA methylation in infants, depending on which trimester maternal depression was most severe, and increased HPA reactivity (Devlin et al., 2010). Further, Devlin et al. discovered that maternal depression in the second trimester affected newborns’ DNA methylation patterns. However, the authors offered key limitations in their study, namely the sample was predominantly male and depressive characteristics differed based on age. Conradt et al. (2016) reported that prenatal depression in mothers may be associated with higher DNA methylation in infants. However, maternal sensitivity (i.e., ability of mother to respond to infants’ needs positively, such as positive touch, attending to distress, and basic social-emotional needs) toward infants buffered the extent of methylation, which points to environmental influences. This finding highlights the risk of infant exposure to maternal depression in conjunction with maternal sensitivity. Yet, overall, the evidence suggests that epigenetic mechanisms are at play across critical periods—prenatal, postnatal, and beyond—that have implications for offspring. When a fetus or offspring experiences adverse conditions, such as maternal depression, there is an increased likelihood of “impaired cognitive, behavioral, and social functioning . . . [including] psychiatric disorders throughout the adult life” (Vaiserman & Koliada, 2017, p. 1). For the practicing counselor, we suggest that clinical work with expecting mothers has the potential to reduce such risk based on these epigenetic findings.

Schizophrenia

Accumulated evidence suggests that schizophrenia arises from the interaction between genetics and the client’s environment (Smigielski et al., 2020). Epigenetics is considered a mediator between a client’s genetics and environment with research showing moderate support for this position. DNA methylation, histone modifications, mRNA, and miRNA epigenetic mechanisms have been linked with schizophrenia (Boks et al., 2018; Cheah et al., 2017; Okazaki et al., 2019).

DNA methylation is a main focus in schizophrenia epigenetic research (Cariaga-Martinez & Alelú-Paz , 2018). For example, Fisher et al. (2015) conducted a longitudinal study investigating epigenetic differences between monozygotic twins who demonstrated differences in psychotic symptoms; at age 12, one twin was symptomatic and the other was asymptomatic. Fisher et al. found DNA methylation differences between these twins. The longitudinal twin study design allowed for the control of genetic contributions to the outcome as well as other internal and external threats. Further, it pointed to a stronger association between epigenetics and schizophrenia.

From a clinical perspective, Ma et al. (2018) identified a potential epigenetic biomarker for detecting schizophrenia. The authors were able to identify three specific miRNAs that may work in combination as a biomarker for the condition. According to the authors, this finding may be helpful in the future for diagnosis and monitoring treatment outcomes. We speculate that future counselors may have biomarker tests conducted as part of the diagnostic process and in monitoring treatment effectiveness with alternation in miRNA levels.

Addiction

In addictions, a diversity of epigenetic mechanisms have been identified (e.g., DNA methylation, histone acetylation, mRNA, miRNA) across various substance use disorders: cocaine, amphetamine, methamphetamine, and alcohol (Hamilton & Nestler, 2019). Moreover, these epigenetic processes have been hypothesized to contribute to the addiction process by mediating seeking behaviors via dopamine in the neurological system. Also, Hamilton and Nestler (2019) found that epigenetic mechanisms have the potential to combat addiction processes, but further research is needed.

Cadet et al. (2016) conducted a review of cocaine, methamphetamine, and epigenetics in animal models (mice and rats). Chronic cocaine use was linked with histone acetylation in the dopamine system and DNA methylation for both chronic and acute administrations. They concluded that epigenetics may be a facilitating factor for cocaine abuse. Others have supported this conclusion for cocaine specifically, in that cocaine alters the chromatin structure by increasing histone acetylation, thereby temporarily inducing addictive behaviors (Maze & Nestler, 2011; Tsankova et al., 2007). From a treatment perspective, Wright et al. (2015) reported, in a sample of rats, that an injected methyl supplementation appeared to attenuate cocaine-seeking behavior when compared to the control group associated with cocaine-induced DNA methylation.

Regarding methamphetamines, during their review, Cadet et al. (2016) discovered that there were only a few extant studies on epigenetics and methamphetamines. Numachi et al. (2004) linked extended use of methamphetamines to changes in DNA methylation patterns, which seemed to increase vulnerability to neurochemical effects. More recently, Jayanthi et al. (2014) discovered that chronic methamphetamine use in rats induced histone hypoacetylation, making it more difficult for transcription to occur and potentially supporting the addiction process. To counter this histone hypoacetylation, the authors treated the mice with valproic acid, which inhibited the histone hypoacetylation. This study may evidence potential psychopharmacological treatments in the future at the epigenetic level for methamphetamine addiction.

H. Zhang and Gelernter (2017) reviewed the literature on DNA methylation and alcohol use disorder (AUD) and found mixed results. The authors discovered that individuals with an AUD exhibited DNA hypermethylation and hypomethylation in a variety of promoter regions. They also noted generalization limitations due to small tissue samples from the same regions of postmortem brains. They suggested that DNA methylation may account for “missing heritability” (p. 510) among individuals with AUDs.

Histone deacetylation has also been connected to chromatin closing or silencing for chronic users of alcohol, which may be involved in the maintenance of an AUD. Palmisano and Pandey (2017) suggested that there are epigenetic mediating factors between comorbidity of AUDs and anxiety disorders. On a positive note, exercise has been found to have opposite epigenetic modifications when comparing a healthy exercise group to a group who experience AUDs in terms of DNA methylation at CpG sites (Chen et al., 2018). Thus, counselors may incorporate such aspects in psychoeducation when recommending exercise in goal setting and other treatment interventions.

To summarize, epigenetics has been linked to several disorders such as anxiety, stress, depression, schizophrenia, and addiction (Albert et al., 2019; Cadet et al., 2016; Lester et al., 2016; Palmisano & Pandey, 2017; Smigielski et al., 2020). DNA methylation and miRNA may have mediating effects for mental health concerns such as anxiety (Harris & Seckl, 2011; Romens et al., 2015). Additionally, epigenetic mediating effects have also been discovered in major depressive disorder, maternal depression, and addiction (Albert et al., 2019; Conradt et al., 2016; Hamilton & Nestler, 2019). Moreover, epigenetic imprinting has been associated with trauma and stress, as found in Holocaust survivors and their children (Yehuda et al., 2016). Overall, “evidence accumulates that exposure to social stressors in [childhood], puberty, adolescence, and adulthood can influence behavioral, cellular, and molecular phenotypes and . . . are mediated by epigenetic mechanisms” (Pishva et al., 2014, p. 342).

Implications

A key aim in providing a primer on epigenetics, specifically the coaction between a client’s biology and environment on gene expression, is to illuminate opportunities for counselors to prevent and intervene upon mental health concerns. This is most relevant based on the evidence that epigenetic processes change over a client’s lifetime because of environmental influences, meaning that the client is not in a fixed state per traditional gene theory (Nestler et al., 2016). Epigenetics provides an alternate view of nature and nurture, demonstrating that epigenetic tags may not only be influenced by unfavorable environmental influences (e.g., maternal depression, trauma, bullying, child abuse and neglect) but also by favorable environments and activities (e.g., mindfulness, CBT, exercise, diet, nurturing; Chaix et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2018; Conradt et al., 2016; Roberts et al., 2015; Stevens et al., 2018). Understanding the flexibility of epigenetics has the potential to engender hope for our clients and to guide our work as counselors and counselor educators, because our genetic destinies are not fixed as we once theorized in gene theory.

Bioecological Conceptualization: Proximal and Distal Impact and Interventions

The impact of epigenetics on the counseling profession can be understood using Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) bioecological model. The bioecological model conceptualizes a client’s function over time based on the coaction between the client and their environment (Broderick & Blewitt, 2015; Jones & Tang, 2015). The client’s environment can have both beneficial and deleterious proximal and distal effects. These effects are like concentric rings around the client, which Bronfenbrenner called “subsystems.” The most proximate subsystem is the microsystem, the environment that has a direct influence on the client, such as parents, teachers, classmates, coworkers, relatives, etc. The next level is the mesosystem, in which the micro entities interact with one another or intersect with influence on the client (e.g., school and home intersect to influence client’s thinking and behavior). The next system, called the exosystem, begins the level of indirect influence. This may include neighborhood factors such as the availability of fresh produce, safe neighborhoods, social safety net programs, and employment opportunities. The last subsystem is the macrosystem. This system consists of the cultural norms, values, and biases that influence all other systems. The final aspect of this model, called the chronosystem, takes into account development over time. The chronosystem directs the counselor’s attention to developmental periods that have differing risks and opportunities, or what can be called “critical” developmental periods.

Below we conceptualize epigenetic counseling implications using Bronfenbrenner’s model but simplify it by grouping systems: proximal effects (micro/meso level) labeled as micro effects and distal effects (exo/macro level) labeled as macro effects. We will also apply the chronosystem by focusing on critical developmental periods that are salient when applying epigenetics to counseling. Ultimately, our central focus is the client and the concentric influences of micro and macro effects. To begin, we will first focus on the important contribution of epigenetics during the critical developmental period of 0 to 5 years of age with implications at the micro and macro levels.

Epigenetics Supports Early Life Span Interventions

Though the evidence does support epigenetic flexibility across a client’s life span, we know that early adverse life events may alter a child’s epigenome with mediating effects on development and behavior (Lester & Marsit, 2018). We also know that epigenetic processes are most active in the first 5 years of life (Mulligan, 2016; Syzf et al., 2016). These early insults to the genome may elicit poor mental health into adulthood such as anxiety, depression, schizophrenia, and addiction. For example, a client who grew up in an urban environment with a traditionally marginalized group status and parents who experienced drug dependence has an increased risk for schizophrenia above and beyond the genetic, inherited risk. These adverse childhood experiences have the potential to modify the epigenome, increasing the likelihood of developing mental health concerns, including schizophrenia (Cariaga-Martinez & Alelú-Paz, 2018).

At the micro level, the caregiver can be a salutary effect against adverse environmental conditions (Oberlander et al. 2008; Weaver et al., 2005). Prenatally, counseling can work with parents before birth to generate healthy coping strategies (e.g., reduce substance abuse), flexible and adaptive caregiver functioning, and effective parenting strategies. An example of this is to use parent–child interactive therapy (PCIT) pre-clinically, or before the child evidences a disorder (Lieneman et al., 2017). Preventive services using PCIT have been documented as effective with externalizing behaviors, child maltreatment, and developmental delays. Additional micro-level interventions can be found in the use of home-visiting programs to improve child outcomes prenatally to 5 years of age where positive parenting and other combined interventions are utilized to improve the health of mother, father, and child (Every Child Succeeds, 2019; Healthy Families New York, 2021).

Clinically, epigenetics points to earlier care and treatment to prevent the emergence of mental disorders (e.g., major depressive disorder, schizophrenia). Also, epigenetic research has provided evidence that environmental change can be equally important as client change. Regarding treatment planning, examining the client’s individual level factors or microsystem (e.g., physical health, mental status, education, race, gender) as well as their macrosystem (e.g., social stigma, poverty, housing quality, green space, pollution) may be crucial before considering what kind of modifications and/or interventions are most appropriate. For example, if a 9-year-old White female presents to a counselor for behavioral concerns in school, it is important for the counselor to gather a holistic life history to build an informed picture of the many variables collectively impacting the child’s behavior at each level. At the micro level, a counselor will evaluate for childhood maltreatment, but from an epigenetic lens, other proximal environmental factors could be important to screen for such as poverty, maternal depression, nutrition, classroom dynamics, and exercise (McEwen & McEwen, 2017; Mulligan, 2016). If the 9-year-old child is experiencing parental neglect and food insecurity, the clinician can treat the client’s individual needs at the micro level (i.e., working with the family system to overcome any neglect by using treatments such as PCIT, and direct referral to social workers and other agencies to provide food and shelter to meet basic needs).

The science of epigenetics may also inform action taken during assessment and case conceptualization based on the coaction of environment with a client over time. Although intervention at 0–5 years of age is most preventative, it is not practical in all cases. Using assessments that collect information on an adult client’s early life may help inform case conceptualization and allow the integration of epigenetics into counseling theories to better understand the etiology of a client’s presenting problem(s). For example, using an adverse childhood experiences assessment may help identify individuals at higher risk of epigenetic concerns. Epigenetics highlights the impact of client–environment interaction and its influence (positive or negative) on overall health. Additionally, early life adversity increases the likelihood of poor health outcomes such as heart disease, anxiety, and depression. However, these poor consequences could be mediated by talking with clients about the importance of exercise and its benefit on epigenetics and, by extension, mental health.

At the macro level, examples could include the reduction of hostile environments (e.g., institutional racism, neighborhood violence, limited employment opportunities, low wages, air pollutants, water pollutants), advocacy for statutes, regulations to decrease instability such as unfair housing in low-income neighborhoods, establishing partnerships in the development of community-based and school-based prevention programs, and applying early interventions such as mindfulness to reduce the effects of stress (Chaix et al., 2020). To illustrate, postnatal depression symptom severity has been associated with residential stability (Jones et al., 2018). By developing policies that would increase housing security, a reduction in maternal depression symptom severity could potentially reduce the DNA methylation that is associated with upregulation of the HPA and child reactivity, but this would need to be investigated further for confirmation. According to Rutten et al. (2013), this change may also increase the resiliency of children by reducing their experience of chronic stress, as sustained maternal depression severity often impacts caregiving because of unstable housing.

Although members of the counseling profession have known the significance of early intervention for years, this epigenetic understanding confirms why human growth and development is a core component of our counseling professional identity (Remley & Herlihy, 2020) and provides a supporting rationale for our efforts. Additionally, epigenetic tags have the potential to cross generations via the process of imprinting (Yehuda et al., 2016). This has potential implications across the life span.

In summary, critical developmental periods must be a focal point for counseling interventions, necessitating upstream action rather than our current dominant approach of downstream activities and a shift toward primary prevention over predominantly tertiary prevention. Such primary prevention would reduce stress and trauma for children before signs and symptoms become apparent and attend to the development and sustainability of healthy environments that would increase both client and community wellness.

Epigenetics Supports Counseling Advocacy and Social Justice Efforts

When reflecting on the implications of epigenetics, it is apparent that place, context, and the client’s environment are critical factors for best positioning them for healthy outcomes, engendering a push for advocacy and social justice for clients. Because environments have no boundaries, it is important to think of advocacy across many systems: towns, counties, states, countries, and the world. This reinforces the call for counselors and counselor educators to move beyond the walls of their workplaces in order to collaborate within the larger mental health field (e.g., clinical mental health, school, marriage and family, addiction, rehabilitation). Additionally, said knowledge compels connection with other professions—such as social workers, physicians, psychologists, engineers, housing developers, public health administrators, and members of nonprofit and faith-based organizations, etc.—to enact change on a wider scale and to improve the conditions for clients at a systemic level.

This collaboration also calls for engaging at local and international levels. Global human rights issues such as sex trafficking cross countries, regions, and local communities and necessitate collaboration to ameliorate these practices and the associated trauma. For starters, the American Counseling Association and the International Association for Counseling could partner with other organizations such as the Child Defense Fund to assist in meeting their mission to level the playing field for all children in the United States. At the local level, counselors and counselor educators could collaborate with local children’s hospitals and configure a plan to meet common goals to improve children’s health and wellness.

Counseling Research and Epigenetics

Research primarily affects clients on a macro level but can trickle down to directly engage clients within our clinical work and practice. Counselors and counselor educators can partner with members of other disciplines to further the work with epigenetic biomarkers (e.g., depression and DNA methylation). Counseling researchers can also investigate how talk therapy and other adjuncts, such as diet and exercise, may improve our clients’ treatment outcomes. As counseling researchers, we can develop research agendas around intervention and prevention for those 0–5 years of age and create and evaluate programs for this age group while also creating community partnerships as noted above. An example of this partnership is The John Hopkins Center for Prevention and Early Intervention. The creators of this program developed sustainable partnerships with public schools, mental health systems, state-level educational programs, universities, and federal programs to focus on early interventions that are school-based and beyond. They collaborated to develop, evaluate, and deliver a variety of programs and research activities to improve outcomes for children and adolescents. They have created dozens of publications based on these efforts that help move the discipline forward. In one such publication, Guintivano et al. (2014) looked at epigenetic and genetic biomarkers for predicting suicide.

Counselor Education, CACREP, and Epigenetics

The counselor educational system affects clients distally but also holds implications for the work counselors conduct at the client level. Counselor educators can provide a more robust understanding of epigenetics to counseling students across the counselor education curriculum. These efforts can include introducing epigenetics in theories, diagnosis, treatment, human and family development, practicum and internship, assessment, professional orientation, and social and cultural foundations courses. By assisting counseling students to comprehend the relationship between client and environment, as well as the importance of prevention, educators will increase their students’ ability to carry out a holistic approach with clients and attend to the foundational emphases of the counseling profession on wellness and prevention. Moreover, by learning to include epigenetics in case conceptualization, students can gain a more robust understanding of the determinants of symptomology, potential etiology at the cellular level, and epigenetically supported treatments such as CBT and mindfulness.

It is fairly simple to integrate epigenetics education into programs accredited by the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP; 2015). To begin, counselor educators can integrate epigenetics education into professional counseling orientation and ethical practice courses. As counselor educators discuss the history and philosophy of the counseling profession, particularly from a wellness and prevention lens (CACREP, 2015, 2.F.1.a), counselor educators can discuss the connection between epigenetics and wellness. Wellness is a foundational value for the counseling profession and is a part of the definition of counseling (Kaplan et al., 2014). Many wellness models (both theoretical and evidence-based) are rooted in the promotion of a holistic balance of the client in a variety of facets and contexts (Myers & Sweeney, 2011). We can continue to support these findings by integrating epigenetics within our conversations about wellness, as we have epigenetic evidence that the positive or negative coaction between the individual and their environment can impact a person toward increased or decreased wellness.

Counselor educators can also integrate epigenetics education into Social and Cultural Diversity and Human Growth and Development courses. Within Social and Cultural Diversity courses, counselor educators can address how negative environmental conditions have negative influences on offspring. This is evidenced by the discrimination against Jews and its imprinting that crosses generations (Yehuda et al., 2016). Counselor educators can discuss how discrimination and barriers to positive environmental conditions can impact someone at the epigenetic level (CACREP, 2015, 2.F.2.h). Within Human Growth and Development, counselor educators can discuss how the study of epigenetics provides us a biological theory to understand how development is influenced by environment across the life span (CACREP, 2015, 2.F.3.a, c, d, f). In particular, it can provide an etiology of how negative factors change epigenetic tags, which are correlated with negative mental health that may become full-blown mental health disorders later in adulthood (CACREP, 2015, 2.F.3.c, d, e, g).

Additionally, counselor educators can integrate epigenetic education within specialty counseling areas. Several studies (Maze & Nestler, 2011; Palmisano & Pandey, 2017; Tsankova et al., 2007; Wong et al., 2011; H. Zhang & Gelernter, 2017) have noted how epigenetic mechanisms may support the addiction process and counselor educators can interweave this information when discussing theories and models of addiction and mental health problems (CACREP, 2015, 5.A.1.b; 5.C.1.d; 5.C.2.g). Counselor educators can also discuss epigenetics as it applies to counseling practice. Because epigenetics research supports treatments like CBT, mindfulness, nutrition, and exercise (Chaix et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2018; Roberts et al., 2015; Stevens et al., 2018), counselor educators can address these topics in courses when discussing techniques and interventions that work toward prevention and treatment of mental health issues (CACREP, 2015, 5.C.3.b).

Generally, CACREP (2015) standards support programs that infuse counseling-related research into the curriculum (2.E). We support the integration of articles, books, websites, and videos that will engender an understanding of epigenetics across the curriculum, so long as the integration supports student learning and practice.

Conclusion and Future Directions

In summary, there are numerous epigenetic processes at work in the symptoms we attend to as counselors. We have provided information that illustrates how epigenetics may mediate outcomes such as depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, and addiction. We have also illustrated how CBT, exercise, diet, and meditation may have positive epigenetic influences supporting our craft. We have discovered that epigenetic processes are most malleable in early life. This information offers incremental evidence for our actions as professional counselors, educators, and researchers, leading to a potential examination of our efforts in areas of prevention, social justice, clinical practice, and counseling program development. However, we must note that epigenetics as a science is relatively new and much of the research is correlational.

Based on the current limits of epigenetic science and a lack of investigation of mental health epigenetics in professional counseling, one of our first recommendations for future research efforts is to collaborate across professions with other researchers such as geneticists, as we did for this manuscript. From this partnership, our profession’s connection to epigenetics is elucidated. Interdisciplinary collaboration allows the professional counselor to offer their expertise in mental health and the geneticist their deep understanding of epigenetics and the tools to examine the nature and nurture relationships in mental health outcomes. We can also make efforts to look at our wellness-based preventions and interventions to document changes at the epigenetic level in our clients and communities. Ideally, as the science of epigenetics advances, we will have epigenetic research in our profession of counseling that is beyond correlation and evidences the effectiveness of our work down to the cellular level.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The development of this manuscript was supported

in part by a Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical

Center Trustee Award and by a grant from the

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL132344).

The authors reported no conflict of interest.

References

Albert, P. R., Le François, B., & Vahid-Ansari, F. (2019). Genetic, epigenetic and posttranscriptional mechanisms for treatment of major depression: The 5-HT1A receptor gene as a paradigm. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience, 44(3), 164–176. https://doi.org/10.1503/jpn.180209

Arnaud, P. (2010). Genomic imprinting in germ cells: Imprints are under control. Reproduction, 140(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1530/REP-10-0173

Benoit, L., & Turecki, G. (2010). The epigenetics of suicide: Explaining the biological effects of early life environmental adversity. Archives of Suicide Research, 14(4), 291–310.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2010.524025

Benros, M. E., Nielsen, P. R., Nordentoft, M., Eaton, W. W., Dalton, S. O., & Mortensen, P. B. (2011). Autoimmune diseases and severe infections as risk factors for schizophrenia: A 30-year population-based register study. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(12), 1303–1310. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11030516

Bocchio-Chiavetto, L., Maffioletti, E., Bettinsoli, P., Giovannini, C., Bignotti, S., Tardito, D., Corrada, D., Milanesi, L., & Gennarelli, M. (2013). Blood microRNA changes in depressed patients during antidepressant treatment. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 23(7), 602–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.06.013

Boks, M. P., Houtepen, L. C., Xu, Z., He, Y., Ursini, G., Maihofer, A. X., Rajarajan, P., Yu, Q., Xu, H., Wu, Y., Wang, S., Shi, J. P., Hulshoff Pol, H. E., Strengman, E., Rutten, B. P. F., Jaffe, A. E., Kleinman, J. E., Baker, D. G., Hol, E. M., . . . Kahn, R. S. (2018). Genetic vulnerability to DUSP22 promoter hypermethylation is involved in the relation between in utero famine exposure and schizophrenia. Nature Partner Journals Schizophrenia, 4(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-018-0058-4

Broderick, P. C., & Blewitt, P. (2015). The life span: Human development for helping professionals (4th ed.). Pearson.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

Brooker, R. J. (2017). Genetics: Analysis and principles (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Cadet, J. L., McCoy, M. T., & Jayanthi, S. (2016). Epigenetics and addiction. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 99(5), 502–511. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.345

Cariaga-Martinez, A., & Alelú-Paz, R. (2018). Epigenetic and schizophrenia. In F. Durbano (Ed.), Psychotic disorders – An update (pp. 147–162). IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.73242

Chaix, R., Fagny, M., Cosin-Tomás, M., Alvarez-López, M., Lemee, L., Regnault, B., Davidson, R. J., Lutz, A., & Kaliman, P. (2020). Differential DNA methylation in experienced meditators after an intensive day of mindfulness-based practice: Implications for immune-related pathways. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 84, 36–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2019.11.003

Champagne, F. A. (2010). Early adversity and developmental outcomes: Interaction between genetics, epigenetics, and social experiences across the life span. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(5), 564–574.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691610383494

Cheah, S.-Y., Lawford, B. R., Young, R. M., Morris, C. P., & Voisey, J. (2017). mRNA expression and DNA methylation analysis of serotonin receptor 2A (HTR2A) in the human schizophrenic brain. Genes, 8(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes8010014

Chen, J., Hutchinson, K. E., Bryan, A. D., Filbey, F. M., Calhoun, V. D., Claus, E. D., Lin, D., Sui, J., Du, Y., & Liu, J. (2018). Opposite epigenetic associations with alcohol use and exercise intervention. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9(594), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00594

Cohen, J. L., Jackson, N. L., Ballestas, M. E., Webb, W. M., Lubin, F. D., & Clinton, S. M. (2017). miR-101a-3p and Ezh2 modulate anxiety-like behavior in high-responder rats. European Journal of Neuroscience, 46(7), 2241–2252.

Conradt, E., Hawes, K., Guerin, D., Armstrong, D. A., Marsit, C. J., Tronick, E., & Lester, B. M. (2016). The contributions of maternal sensitivity and maternal depressive symptoms to epigenetic processes and neuroendocrine functioning. Child Development, 87(1), 73–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12483

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2015). 2016 CACREP standards. http://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/2016-Standards-with-citations.pdf

Devlin, A. M., Brain, U., Austin, J., & Oberlander, T. F. (2010). Prenatal exposure to maternal depressed mood and the MTHFR C677T variant affect SLC6A4 methylation in infants at birth. PloS ONE, 5(8), e12201.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0012201

Every Child Succeeds. (2019). 2019 report to the community. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5df9251a492

ba56bc96bc96f/t/5e73b2a333e8127c09daabf2/1584640684722/Final2019Report.pdf

Fisher, H. L., Murphy, T. M., Arseneault, L., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., Viana, J., Hannon, E., Pidsley, R., Burrage, J., Dempster, E. L., Wong, C. C. Y., Pariante, C. M., & Mill, J. (2015). Methylomic analysis of monozygotic twins discordant for childhood psychotic symptoms. Epigenetics, 10(11), 1014–1023.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15592294.2015.1099797

Gejman, P. V., Sanders, A. R., & Kendler, K. S. (2011). Genetics of schizophrenia: New findings and challenges. Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics, 12, 121–144.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-genom-082410-101459

Guintivano, J., Brown, T., Newcomer, A., Jones, M., Cox, O., Maher, B. S., Eaton, W. W., Payne, J. L., Wilcox, H. C., & Kaminsky, Z. A. (2014). Identification and replication of a combined epigenetic and genetic biomarker predicting suicide and suicidal behaviors. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(12), 1287–1296.

https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14010008

Haggarty, S. J., & Tsai, L.-H. (2011). Probing the role of HDACs and mechanisms of chromatin-mediated neuroplasticity. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 96(1), 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nlm.2011.04.009

Hamilton, P. J., & Nestler, E. J. (2019). Epigenetics and addiction. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 59, 128–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2019.05.005

Harris, A., & Seckl, J. (2011). Glucocorticoids, prenatal stress and the programming of disease. Hormones and Behavior, 59(3), 279–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.06.007

Healthy Families New York. (2021, January 4). [Website.] https://www.healthyfamiliesnewyork.org

Heijmans, B. T., Tobi, E. W., Stein, A. D., Putter, H., Blauw, G. J., Susser, E. S., Slagboom, P. E., & Lumey, L. H. (2008). Persistent epigenetic differences associated with prenatal exposure to famine in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(44), 17046–17049. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0806560105

Huang, W.-C., Ferris, E., Cheng, T., Hörndli, C. S., Gleason, K., Tamminga, C., Wagner, J. D., Boucher, K. M., Christian, J. L., & Gregg, C. (2017). Diverse non-genetic, allele-specific expression effects shape genetic architecture at the cellular level in the mammalian brain. Neuron, 93(5), 1094–1109.e7.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2017.01.033

Januar, V., Ancelin, M.-L., Ritchie, K., Saffery, R., & Ryan, J. (2015). BDNF promoter methylation and genetic variation in late-life depression. Translational Psychiatry, 5, e619. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2015.114

Jayanthi, S., McCoy, M. T., Chen, B., Britt, J. P., Kourrich, S., Yau, H.-J., Ladenheim, B., Krasnova, I. N., Bonci, A., & Cadet, J. L. (2014). Methamphetamine downregulates striatal glutamate receptors via diverse epigenetic mechanisms. Biological Psychiatry, 76(1), 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.09.034

Jones, D. E., & Tang, M. (2015). Health inequality: What counselors need to know to act. In Ideas and research you can use: VISTAS 2015. https://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/vistas/article_60785a22f16116603abcacff0000bee5e7.pdf?sfvrsn=4

Jones, D. E., Tang, M., Folger, A., Ammerman, R. T., Hossain, M. M., Short, J. A., & Van Ginkel, J. B. (2018). Neighborhood effects on PND symptom severity for women enrolled in a home visiting program. Community Mental Health Journal, 54(4), 420–428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-017-0175-y

Kaplan, D. M., Tarvydas, V. M., & Gladding, S. T. (2014). 20/20: A vision for the future of counseling: The new consensus definition of counseling. Journaling of Counseling & Development, 92, 366–372. https://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/20-20/2020-jcd-article-consensus-definition.pdf?sfvrsn=76017f2c_2

Lester, B. M., Conradt, E., & Marsit, C. (2016). Introduction to the special section on epigenetics. Child Development, 87(1), 29–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12489

Lester, B. M., & Marsit, C. J. (2018). Epigenetic mechanisms in the placenta related to infant neurodevelopment. Epigenomics, 10(3), 321–333. https://doi.org/10.2217/epi-2016-0171

Lewis, B. P., Burge, C. B., & Bartel, D. P. (2005). Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell, 120(1), 15–20.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035

Lieneman, C. C., Brabson, L. A., Highlander, A., Wallace, N. M., & McNeil, C. B. (2017). Parent–child interaction therapy: Current perspectives. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 10, 239–256.

https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S91200

Lüscher, B., & Möhler, H. (2019). Brexanolone, a neurosteroid antidepressant, vindicates the GABAergic deficit hypothesis of depression and may foster resilience. F1000Research, 8(May), 1–14.

https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.18758.1

Ma, J., Shang, S., Wang, J., Zhang, T., Nie, F., Song, X., Zhao, H., Zhu, C., Zhang, R., & Hao, D. (2018). Identification of miR-22-3p, miR-92a-3p, and miR-137 in peripheral blood as biomarker for schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research, 265, 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.03.080

Maze, I., & Nestler, E. J. (2011). The epigenetic landscape of addiction. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1216(1), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05893.x

McEwen, C. A., & McEwen, B. S. (2017). Social structure, adversity, toxic stress, and intergenerational poverty: An early childhood model. Annual Review of Sociology, 43, 445–472.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-060116-053252

McGowan, P. O., Sasaki, A., D’Alessio, A. C., Dymov, S., Labonté, B., Szyf, M., Turecki, G., & Meaney, M. J. (2009). Epigenetic regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor in human brain associates with childhood abuse. Nature Neuroscience, 12(3), 342–348. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2270

Monk, C., Spicer, J., & Champagne, F. A. (2012). Linking prenatal maternal adversity to developmental outcomes in infants: The role of epigenetic pathways. Development and Psychopathology, 24(4), 1361–1376.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579412000764

Mulligan, C. J. (2016). Early environments, stress, and the epigenetics of human health. Annual Review of Anthropology, 45(1), 233–249. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102215-095954

Myers, J. E., & Sweeney, T. J. (2011). Wellness counseling: The evidence base for practice. Journal of Counseling & Development, 86(4), 482–493. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2008.tb00536.x

National Human Genome Research Institute. (2020). Epigenomics fact sheet. https://www.genome.gov/about-genomics/fact-sheets/Epigenomics-Fact-Sheet

Nestler, E. J., Peña, C. J., Kundakovic, M., Mitchell, A., & Akbarian, S. (2016). Epigenetic basis of mental illness. The Neuroscientist, 22(5), 447–463. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073858415608147

Numachi, Y., Yoshida, S., Yamashita, M., Fujiyama, K., Naka, M., Matsuoka, H., Sato, M., & Sora, I. (2004). Psychostimulant alters expression of DNA methlytransferase mRNA in the rat brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1025(1), 102–109. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1316.013

Oberlander, T. F., Weinberg, J., Papsdorf, M., Grunau, R., Misri, S., & Devlin, A. M. (2008). Prenatal exposure to maternal depression, neonatal methylation of human glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) and infant cortisol stress responses. Epigenetics, 3(2), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.4161/epi.3.2.6034

Okazaki, S., Otsuka, I., Numata, S., Horai, T., Mouri, K., Boku, S., Ohmori, T., Sora, I., & Hishimoto, A. (2019). Epigenetic clock analysis of blood samples from Japanese schizophrenia patients. npj Schizophrenia, 5(9), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-019-0072-1

Ouellet-Morin, I., Wong, C. C. Y., Danese, A., Pariante, C. M., Papadopoulos, A. S., Mill, J., & Arseneault, L. (2013). Increased serotonin transporter gene (SERT) DNA methylation is associated with bullying victimization and blunted cortisol response to stress in childhood: A longitudinal study of discordant monozygotic twins. Psychology of Medicine, 43(9), 1813–1823. https://doi.org/10.107/S0033291712002784

Palmisano, M., & Pandey, S. C. (2017). Epigenetic mechanisms of alcoholism and stress-related disorders. Alcohol, 60, 7–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcohol.2017.01.001

Perroud, N., Paoloni-Giacobino, A., Prada, P., Olié, E., Salzmann, A., Nicastro, R., Guillaume, S., Mouthon, D.,

Stouder, C., Dieben, K., Huguelet, P., Courtet, P., & Malafosse, A. (2011). Increased methylation of glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) in adults with a history of childhood maltreatment: A link with the severity and type of trauma. Translational Psychiatry, 1, e59. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2011.60

Pishva, E., Kenis, G., van den Hove, D., Lesch, K.-P., Boks, M. P. M., van Os, J., & Rutten, B. P. F. (2014). The epigenome and postnatal environmental influences in psychotic disorders. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49, 337–348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-014-0831-2

Provençal, N., & Binder, E. B. (2015). The effects of early life stress on the epigenome: From the womb to adulthood and even before. Experimental Neurology, 268, 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.09.001

Remley, T. P., Jr., & Herlihy, B. (2020). Ethical, legal, and professional issues in counseling (6th ed.). Pearson.

Roberts, S., Keers, R., Lester, K. J., Coleman, J. R. I., Breen, G., Arendt, K., Blatter-Meunier, J., Cooper, P., Creswell, C., Fjermestad, K., Havik, O. E., Herren, C., Hogendoorn, S. M., Hudson, J. L., Krause, K., Lyneham, H. J., Morris, T., Nauta, M., Rapee, R. M., . . . Wong, C. C. Y. (2015). HPA axis related genes and response to psychological therapies: Genetics and epigenetics. Depression and Anxiety, 32(12), 861–870.

https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22430

Rodgers, A. B., Morgan, C. P., Bronson, S. L., Revello, S., & Bale, T. L. (2013). Paternal stress exposure alters sperm microRNA content and reprograms offspring HPA stress axis regulation. Journal of Neuroscience, 33(21), 9003–9012. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0914-13.2013

Romens, S. E., McDonald, J., Svaren, J., & Pollak, S. D. (2015). Associations between early life stress and gene methylation in children. Child Development, 86(1), 303–309. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12270

Rutten, B. P. F., Hammels, C., Geschwind, N., Menne-Lothmann, C., Pishva, E., Schruers, K., van den Hove, D.,

Kenis, G., van Os, J., & Wichers, M. (2013). Resilence in mental health: Linking psychological and neurobiological perspectives. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 128(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12095

Saavedra, K., Molina-Márquez, A. M., Saavedra, N., Zambrano, T., & Salazar, L. A. (2016). Epigenetic modifications of major depressive disorder. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 17(8), 1279.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17081279

Shimada-Sugimoto, M., Otowa, T., & Hettema, J. M. (2015). Genetics of anxiety disorders: Genetic epidemiological and molecular studies in humans. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 69(7), 388–401.

https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.12291

Smearman, E. L., Almli, L. M., Conneely, K. N., Brody, G. H., Sales, J. M., Bradley, B., Ressler, K. J., & Smith, A. K.

(2016). Oxytocin receptor genetic and epigenetic variations: Association with child abuse and adult psychiatric symptoms. Child Development, 87(1), 122–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12493

Smigielski, L., Jagannath, V., Rössler, W., Walitza, S., & Grünblatt, E. (2020). Epigenetic mechanisms in schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders: A systematic review of empirical human findings. Molecular Psychiatry, 25, 1718–1748. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0601-3

Stevens, A. J., Rucklidge, J. J., & Kennedy, M. A. (2018). Epigenetics, nutrition and mental health: Is there a relationship? Nutritional Neuroscience, 21(9), 602–613. https://doi.org/10.1080/1028415X.2017.1331524

Suderman, M., Borghol, N., Pappas, J. J., Pinto Pereira, S. M., Pembrey, M., Hertzman, C., Power, C., & Szyf, M. (2014). Childhood abuse is associated with methylation of multiple loci in adult DNA. BMC Medical Genomics, 7, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1755-8794-7-13

Szyf, M. (2009). The early life environment and the epigenome. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1790(9), 878–885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.01.009

Szyf, M., Tang, Y.-Y., Hill, K. G., & Musci, R. (2016). The dynamic epigenome and its implications for behavioral interventions: A role for epigenetics to inform disorder prevention and health promotion. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 6(1), 55–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-016-0387-7

Szyf, M., Weaver, I., & Meaney, M. (2007). Maternal care, the epigenome and phenotypic differences in behavior. Reproductive Toxicology, 24(1), 9–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2007.05.001

Tsankova, N., Renthal, W., Kumar, A., & Nestler, E. J. (2007). Epigenetic regulation in psychiatric disorders. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 8, 355–367. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2132

Turecki, G. (2014). Epigenetics and suicidal behavior research pathways. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 47(3), S144–S151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.06.011

Vaiserman, A. M., & Koliada, A. K. (2017). Early-life adversity and long-term neurobehavioral outcomes: Epigenome as a bridge? Human Genomics, 11(34), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40246-017-0129-z

Weaver, I. C. G., Champagne, F. A., Brown, S. E., Dymov, S., Sharma, S., Meaney, M. J., & Szyf, M. (2005). Reversal of maternal programming of stress responses in adult offspring through methyl supplementation: Altering epigenetic marking later in life. Journal of Neuroscience, 25(47), 11045–11054.

https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3652-05.2005

Wong, C. C. Y., Mill, J., & Fernandes, C. (2011). Drugs and addiction: An introduction to epigenetics. Addiction, 106(3), 480–489. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03321.x

Wright, K. N., Hollis, F., Duclot, F., Dossat, A. M., Strong, C. E., Francis, T. C., Mercer, R., Feng, J., Dietz, D. M., Lobo, M. K., Nestler, E. J., & Kabbaj, M. (2015). Methyl supplementation attenuates cocaine-seeking behaviors and cocaine-induced c-Fos activation in a DNA methylation-dependent manner. The Journal of Neuroscience, 35(23), 8948–8958. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5227-14.2015

Yehuda, R., Daskalakis, N. P., Bierer, L. M., Bader, H. N., Klengel, T., Holsboer, F., & Binder, E. B. (2016). Holocaust exposure induced intergenerational effects on FKBP5 methylation. Biological Psychiatry, 80, 372–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.08.005

Yehuda, R., Engel, S. M., Brand, S. R., Seckl, J., Marcus, S. M., & Berkowitz, G. S. (2005). Transgenerational effects of posttraumatic stress disorder in babies of mothers exposed to the World Trade Center attacks during pregnancy. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 90(7), 4115–4118.

https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2005-0550

Zhang, H., & Gelernter, J. (2017). Review: DNA methylation and alcohol use disorders: Progress and challenges. The American Journal on Addictions, 26(5), 502–515. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajad.12465

Zhang, T.-Y., & Meaney, M. J. (2010). Epigenetics and the environmental regulation of the genome and its function. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 439–466. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163625