Sep 7, 2014 | Article, Volume 1 - Issue 3

E. Heather Thompson, Melodie H. Frick, Shannon Trice-Black

Counselors-in-training face the challenges of balancing academic, professional, and personal obligations. Many counselors-in-training, however, report a lack of instruction regarding personal wellness and prevention of personal counselor burnout. The present study used CQR methodology with 14 counseling graduate students to investigate counselor-in-training perceptions of self-care, burnout, and supervision practices related to promoting counselor resilience. The majority of participants in this study perceived that they experienced some degree of burnout in their experiences as counselors-in-training. Findings from this study highlight the importance of the role of supervision in promoting resilience as a protective factor against burnout among counselors-in-training and provide information for counselor supervisors about wellness and burnout prevention within supervision practice

Keywords: counselors-in-training, wellness, burnout, supervision, resilience

Professional counselors, due to often overwhelming needs of clients and heavy caseloads, are at high risk for burnout. Research indicates that burnout among mental health practitioners is a common phenomenon (Jenaro, Flores, & Arias, 2007). Burnout is often experienced as “a state of physical, mental, and emotional exhaustion caused by long-term involvement in emotionally demanding situations” (Gilliland & James, 2001, p. 610). Self-care and recognition of burnout symptoms are necessary for counselors to effectively care for their clients as well as themselves. Counselors struggling with burnout can experience diminished morale, job dissatisfaction (Koeske & Kelly, 1995), negative self-concept, and loss of concern for clients (Rosenberg & Pace, 2006). Clients working with counselors experiencing burnout are at serious risk, as they may not receive proper care and attention to often severe and complicated problems.

The potential hazards for counselor distress in practicum and internship are many. Counselors-in-training often begin their professional journeys with a certain degree of idealism and unrealistic expectations about their roles. Many assume that hard work and efforts will translate to meaningful work with clients who are eager to change and who are appreciative of the counselor’s efforts (Leiter, 1991). However, clients often have complex problems that are not always easily rectified and which contribute to diminished job-related self-efficacy for beginning counselors (Jenaro et al., 2007). In addition, counselor trainees often experience difficulties as they balance their own personal growth as counselors while working with clients with immense struggles and needs (Skovholt, 2001). Furthermore, elusive measures for success in counseling can undermine a new counselor’s sense of professional competence (Kestnbaum, 1984; Skovholt, Grier, & Hanson, 2001). Client progress is often difficult to concretely monitor and define. The “readiness gap,” or the lack of reciprocity of attentiveness, giving, and responsibility between the counselor-in-training and the client, are an additional job-related stressor that may increase the likelihood of burnout (Kestnbaum, 1984; Skovholt et al., 2001; Truchot, Keirsebilck, & Meyer, 2000).

Counselors-in-training are exposed to emotionally demanding stories (Canfield, 2005) and situations which may come as a surprise to them and challenge their ideas about humanity. The emotional demands of counseling entail “constant empathy and one-way caring” (Skovholt et al., 2001, p. 170) which may further drain a counselor’s reservoir of resilience. Yet, mental health practitioners have a tendency to present themselves as caregivers who are less vulnerable to emotional distress, thereby hindering their ability to focus on their own needs and concerns (Barnett, Baker, Elman, & Schoener, 2007; Sherman, 1996). Counselors who do not recognize and address their diminished capacity when stressed are likely to be operating with impaired professional competence, which violates ethical responsibilities to do no harm.

Counselor supervision is designed to facilitate the ethical, academic, personal, and professional development of counselors-in-training (CACREP, 2009). Bolstering counselor resilience in an effort to prevent burnout is one aspect of facilitating ethical, personal, and professional development. Supervisors who work closely with counselors-in-training during their practicum and internship can promote the hardiness and sustainability of counselors-in-training by helping them learn to self-assess in order to recognize personal needs and assert themselves accordingly. This may include learning to say “no” to the demands that exceed their capacity or learning to actively create and maintain rejuvenating relationships and interests outside of counseling (Skovholt et al., 2001). Supervisors also can teach and model self-care and positive coping strategies for stress, which may influence supervisees’ practice of self-care (Aten, Madson, Rice, & Chamberlain, 2008). In an effort to bolster counselor resilience, supervisors can facilitate counselor self-understanding about overextending oneself to prove professional competency to achieve a sense of self-worth (Rosenburg & Pace, 2006). Supervisors can help counselors-in-training come to terms with the need for immediate positive reinforcement related to work or employment, which is limited in the counseling profession as change rarely occurs quickly (Skovholt et al., 2001). Counselor resiliency also may be bolstered by helping counselors-in-training establish realistic measures of success and focus on the aspects of counseling that they can control such as their knowledge and ability to create strong therapeutic alliances rather than client outcomes. In sum, distressing issues in counseling, warning signs of burnout, and coping strategies for dealing with stress should be discussed and the seeds of self-care should be planted so they may grow and hopefully sustain counselors-in-training over the course of their careers.

Method

The purpose of this exploratory study was to investigate counselor-in-training perceptions of self-care, burnout, and supervision practices related to promoting counselor resilience. The primary research questions that guided this qualitative study included: (a) What are master’s-level counselors-in-training’s perceptions of counselor burnout? (b) What are the perceptions of self-care among master’s-level counselors-in-training? (c) What, if anything, have master’s-level counselors-in-training learned about counselor burnout in their supervision experiences? And (d) what, if anything, have master’s level counselors-in-training learned about self-care in their supervision experiences?

The consensual qualitative research method (CQR) was used to explore the supervision experiences of master’s-level counselors-in-training. CQR works from a constructivist-post-positivist paradigm that uses open-ended semi-structured interviews to collect data from individuals, and reaches consensus on domains, core ideas, and cross-analyses by using a research team and an external auditor (Hill, Knox, Thompson, Williams, Hess, & Ladany, 2005; Ponterotto, 2005). Using the CQR method, the research team examined commonalities and arrived at a consensus of themes within and across participants’ descriptions of the promotion of self-care and burnout prevention within their supervision experiences (Hill et al., 2005; Hill, Thompson, & Nutt Williams, 1997).

Participants

Interviewees. CQR methodologists recommend a sample size of 8–15 participants (Hill et al., 2005). The participants in this sample included 14 individuals; 13 females and 1 male, who were graduate students in master’s-level counseling programs and enrolled in practicum or internship courses. The participants attended one of three universities in the United States (one in the Midwest and two in the Southeast). The sample consisted of 10 participants in school counseling programs and 4 participants in clinical mental health counseling programs. Thirteen participants identified as Caucasian, and one participant identified as Hispanic. The ages of participants ranged from 24 to 52 years of age (mean = 28).

Researchers. An informed understanding of the researchers’ attempt to make meaning of participant narratives about supervision, counselor burnout, and self-care necessitates a discussion of potential biases. This research team consisted of three Caucasian female faculty members from three different graduate-level counseling programs. All three researchers are proficient in supervision practices and passionate about facilitating counselor growth and development through supervision. All members of the research team facilitate individual and group supervision for counselors-in-training in graduate programs. The three researchers adhere to varying degrees of humanistic, feminist, and constructivist theoretical leanings. All members of the research team believe that supervision is an appropriate venue for bolstering both personal and professional protective factors that may serve as buffers against counselor burnout. It also is worth noting that the three members of the research team believed they had experienced varying degrees of burnout over the course of their careers. The researchers acknowledge these shared biases and attempted to maintain objectivity with an awareness of their personal experiences with burnout, approaches to supervision, and beliefs regarding the importance of addressing protective factors, wellness and burnout prevention in supervision. This study also was influenced by an external auditor who is a former counselor educator with more than 20 years of experience in qualitative research methods and supervision practice. As colleagues in the field of counselor education and supervision, the research team and the auditor were able to openly and respectfully discuss their differing perspectives throughout the data analysis process, which permitted them to arrive at consensus without being stifled by power struggles.

Procedures for Data Collection

Criterion sampling was used to select participants in an intentional manner to understand specified counseling students’ experiences in supervision. Criteria for participation in this study included enrollment as a graduate student in a master’s-level counseling program and completion of a practicum experience or participation in a counseling internship in a school or mental health counseling agency. Researchers disseminated information about this study by email to master’s-level students in counseling programs at three different universities. Interested students were instructed to contact, by email or phone, a designated member of the research team, who was not a faculty member at their university. All participants were provided with an oral explanation of informed consent and all participants signed the informed consent documents. All procedures followed those established by the Institutional Review Board of the three universities associated with this study.

Within the research team, researchers were designated to conduct all communication, contact, and interviews with participants not affiliated with their respective universities, in order to foster a confidential and non-coercive environment for the participants. Interviews were conducted on one occasion, in person or via telephone, in a semi-structured format. Participants in both face-to-face and telephone interviews were invited to respond to questions from the standard interview protocol (see Appendix A) about their experiences and perceptions of supervision practices that addressed counselor self-care and burnout prevention. Participants were encouraged to elaborate on their perceptions and experiences in order to foster the emergence of a rich and thorough understanding. The transferability of this study was promoted by the rich, thick descriptions provided by an in-depth look at the experiences and perceptions of this sample of counselors-in-training. Interviews lasted approximately 50–70 minutes. The interview protocol was generated after a thorough review of the literature and lengthy discussions about researcher experiences as a supervisee and a supervisor. Follow-up surveys (see Appendix B) were administered electronically to participants six weeks after the interview to capture additional thoughts and experiences of the participants.

Data Analysis

All interviews were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim for data analysis. Transcripts were checked for accuracy by comparing them to the audio-recordings after the transcription process. Participant names were changed to pseudonyms to protect participant anonymity. Participants’ real names and contact information were only used for scheduling purposes. Information linking participants to their pseudonyms was not kept.

Coding of domains. Prior to beginning the data analysis process, researchers generated a general list of broad domain codes based on the interview protocol, a thorough understanding of the extant literature, and a review of the transcripts. Once consensus was achieved, each researcher independently coded blocks of data into each domain code for seven of the 14 cases. Next, as a team, the researchers worked together to generate consensus on the domain codes for the seven cases. The remaining cases were analyzed by pairs of the researchers. The third team member reviewed the work of the pair who generated the domain coding for the remaining seven cases. Throughout the coding process, domains were modified to best capture the data.

Abstracting the core ideas within each domain. Each researcher worked independently to capture the core idea for each domain by re-examining each transcript. Core ideas consisted of concise statements of the data that illuminated the essence of the participant’s expressed perspectives and experiences. As a group, the researchers discussed the wording of core ideas for each case until consensus was achieved.

Cross analysis. The researchers worked independently to identify commonalities of core ideas within domains across cases. Next, as a group, the research team worked to find consensus on the identified categories across cases. Aggregated core ideas were placed into categories and frequency labels were applied to indicate how general, typical, or variant the results were across cases. General frequencies refer to findings that are true for all but one of the cases (Hill et al., 2005). Typical frequencies refer to findings that are present in more than half of the cases. Variant frequencies refer to finding in at least two cases, but less than half.

Audit. An external auditor was invited to question the data analysis process and conclusions. She was not actively engaged in the conceptualization and implementation of this study, which gave the research team the benefit of having an objective perspective. The external auditor reviewed and offered suggestions about the generation of domains and core ideas, and the cross-case categories. Most feedback was given in writing. At times, feedback was discussed via telephone. The research team reviewed all auditor comments, looked for evidence supporting the suggested change, and made adjustments based on team member consensus.

Stability check. For the purpose of determining consistency, two of the 14 transcripts were randomly selected and set aside for cross-case analysis until after the remaining 12 transcripts were analyzed. This process indicated no significant changes in core domains and categories, which suggested consistency among the findings.

Results

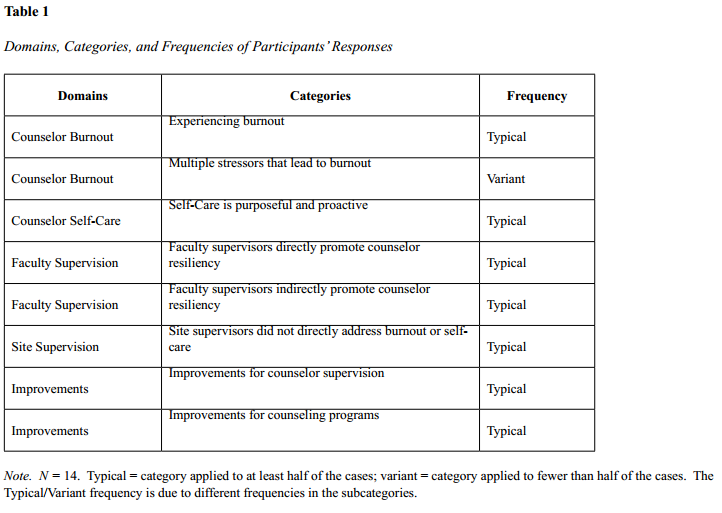

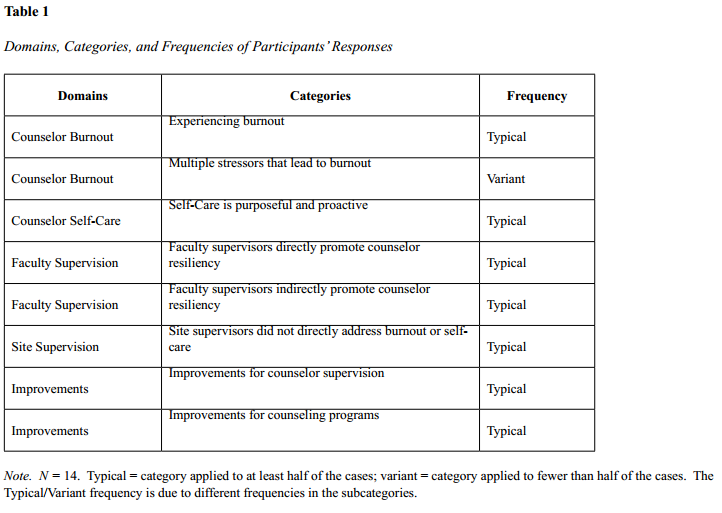

A final consensus identified five domains: counselor burnout, counselor self-care, faculty supervision, site supervision, and improvements (see Table 1). Cross-case categories and subcategories were developed to capture the core ideas. Following CQR procedures (Hill et al., 1997, 2005), a general category represented all or all but one of the cases (n = 13–14); a typical category represented at least half of the cases (n = 7–12); and a variant category represented less than half but more than two of the cases (n = 3 – 6). Categories with fewer than three cases were excluded from further analysis. General categories were not identified from the data.

Counselor Burnout

Experiencing burnout. Most participants reported knowledge of or having experiences with burnout. Participants identified stressors leading to burnout as a loss of enthusiasm and compassion, the struggle to balance school, work, and personal responsibilities and relationships, and difficulty delineating and separating personal and professional boundaries.

Participants described counselor burnout as no longer having compassion or enthusiasm for counseling clients. One participant defined counselor burnout as, “it seems routine or [counselors] feel like they’ve dealt with so many situations over time that they’re just kind of losing some compassion for the field or the profession.” Another participant described counselor burnout as no longer seeing the unique qualities of individuals seen in counseling:

I wouldn’t see [clients] as individuals anymore…and that’s where I get so much of it coming at me, or so many clients coming at me, that they’re no longer an individual they’re just someone that’s sitting in front of me, and when they leave they write me a check….they are not people anymore, they’re clients.

Participants often discussed a continual struggle to balance personal and professional responsibilities. One participant described burnout as foregoing pleasurable activities to focus on work-related tasks:

I can tell when I am starting to get burned out when I am focusing so much on those things that I forgo all of those things that are fun for me. So I am not working out anymore, I am not reading for fun, and I am putting off hanging out with my friends because of my school work. There’s school work that maybe doesn’t have to get done at that moment, but if I don’t work on it I’m going to be thinking about it and not having fun.

Another participant described burnout as having a hard time balancing professional and personal responsibilities stating, “I think I don’t look forward to…working with…people. I’m just kind of glad when they don’t show up. And this kind of sense that I’m losing the battle to keep things in balance.”

Boundary issues were commonly cited by participants. Several participants reported that they struggled to be assertive, set limits, maintain realistic expectations, and not assume personal responsibility for client outcomes. One participant described taking ownership of a client’s outcome and wanting to meet all the needs of her clients:

I believe part of it is internalizing the problem on myself, feeling responsible. Maybe loosing sight of my counseling skills and feeling responsible for the situation. Or feeling helpless. Also, in school counseling there tends to be a larger load of students. And this is frustrating to not meet all the needs that are out there.

Participants reported experiences with burnout and multiple stressors that lead to burnout. Participants defined counselor burnout as a loss of compassion for clients, diminished enthusiasm, difficulty maintaining a life-work balance, and struggles to maintain boundaries.

Counselor Self-Care

Self-care is purposeful and proactive. Participants were asked to describe self-care for counselors and reported that self-care requires purposeful efforts to set time aside to engage in activities outside of work that replenish energy and confidence. Most participants identified having and relying on supportive people, such as family, friends, and significant others to help them cope with stressors. Participants also identified healthy eating and individualized activities such as exercise, reading, meditation, and watching movies as important aspects of their self-care. One participant described self-care as:

Anything that can help you reenergize and refill that bucket that’s being dipped into every day. If that’s going for a walk in the park…so be it. If that’s going to Starbucks…go do it….Or something that makes you feel good about yourself, something that makes you feel confident, or making someone else feel confident….Whatever it is, something that makes you feel good about yourself and knowing that you’re doing what you need to be doing.

Participants reported that self-care requires proactive efforts to consult with supervisors and colleagues; one of the first steps is recognizing when one needs consultation. One participant explained:

I think in our program, [the faculty] were very good about letting us know that if you can’t handle something, refer out, consult. Consult was the theme. And then if you feel you really can’t handle it before you get in over your head, make sure you refer out to someone you feel is qualified.

Participants described self-care as individualized and intentional, and included activities and supportive people outside of school or work settings that replenished their energy levels. Participants also discussed the importance of identifying when counselor self-care is necessary and seeking consultation for difficult client situations.

Faculty Supervision

Faculty supervisors directly promote counselor resiliency. More than half of the participants reported that faculty supervisors directly initiated conversations about self-care. A participant explained, “Every week when we meet for practicum, [the faculty supervisor] is very adamant, ‘is everyone taking care of themselves, is anyone having trouble?’ She is very open to listening to any kind of self-care situation we might have.” Similarly, another participant stated, “Our professors have told us about the importance of self-care and they have tried to help us understand which situations are likely to cause us the most stress and fatigue.” One participant identified preventive measures discussed in supervision:

In supervision, counselor burnout is addressed from the perspective of prevention. We develop personal wellness plans, and discuss how well we live by them during supervision….Self-care is addressed in the same conversation as counselor burnout. In supervision, the mantra is good self-care is vital to avoiding burnout.

Faculty supervisors indirectly promote counselor resiliency. Participants also reported that faculty supervisors indirectly addressed counselor self-care by being flexible and supportive of participants’ efforts with clients. Participants repeatedly expressed appreciation for supervisors who processed cases and provided positive feedback and practical suggestions. One participant explained, “I know that [my supervisor] is advocating for me, on my side, and allowing me to vent, and listening and offering advice if I need it….giving me positive feedback in a very uncomfortable time.”

Further, participants stated they appreciated supervisors who actively created a safe space for personal exploration. One participant explained:

[Supervision] was really a place for us to explore all of ourselves, holistically. The forum existed for us for that purpose. [The supervisors] hold the space for us to explore whatever needs to be explored. That was the great part about internship with the professor I had. He sort of created the space, and we took it. It took him allowing it, and us stepping into the space.

Modeling self-care also is an indirect means of addressing counselor burnout and self-care. Half of the participants reported that their faculty supervisors modeled self-care. For example, faculty supervisors demonstrated boundaries with personal and professional obligations, practiced meditation, performed musically, and exercised. Conversely, participants reported that a few supervisors demonstrated a lack of personal self-care by working overtime, sacrificing time with their families for job obligations, and/or having poor diet and exercise habits.

Participants reported that faculty supervisors directly and indirectly addressed counselor burnout and self-care in supervision. Supervisors who intentionally checked in with the supervisees and used specific techniques such as wellness plans were seen as directly affecting the participants’ perspective on counselor self-care. Supervisors who were present and available, created safe environments for supervision, provided positive feedback and suggestions, and modeled self-care were seen as indirectly addressing counselor self-care. Both direct and indirect means of addressing counselor burnout and self-care were seen as influential by participants.

Site Supervision

Site supervisors did not directly address burnout or self-care. Participants reported that site supervisors rarely initiated conversations about counselor burnout or self-care. One participant reported that counselor burnout was not addressed and as a result she felt a lack of support from the supervisor:

[Site Supervisors] don’t ask about burnout though. Every time I’m bringing it up, the answers I’m getting are ‘well, when you’re in grad school you don’t get a life.’ You know, yeah, I get that, but that’s not really true, so I get a lot of those responses, ‘well, you know, welcome to the club.’

One participant stated that her site supervisor did not specifically address counselor burnout or self-care, stating “I think that is less addressed in a school setting than it is in the mental health field….I think that because we see such a small picture of our students, I think it is not as predominantly addressed.” Some participants, however, reported that their site supervisors indirectly addressed self-care by modeling positive behaviors. One participant stated:

[My site supervisor] has either structured her day or her life in such a way that no one cuts into that time unless she allows it. In that sense, she’s great at modeling what’s important…She just made a choice….She was protective. She made her priorities. Her family was a priority. Her walk was a priority, getting a little activity. Other things, house chores, may have fallen by the wayside. She had a good sense of priorities, I thought. That was good to watch.

In summary, participants reported that counselor burnout and self-care were not directly addressed in site supervision. Indeed, some participants felt a lack of support when feeling overwhelmed by counseling duties, and that school sites may address burnout and self-care less than at mental health sites. At best, self-care was indirectly modeled by site supervisors with positive coping mechanisms.

Improvements for Counselor Supervision and Training

Improvements for counselor supervision. More than half of the participants reported wanting more understanding and empathy from their supervisors. One participant complained:

A lot of my class mates have a lot on their plates, like I do, and our supervisors don’t have as much on their plate as we do. And it seems like they don’t quite get where we are coming from. They are not balancing all the things that we are balancing….a lot of the responses you get demonstrate their lack of understanding.

Another participant suggested:

I think just hearing what the person is saying. If the person is saying, I need a break, just the flexibility. Not to expect miracles, and just remember how it felt when you were in training. Just be relatable to the supervisees and try to understand what they are going through, and their point of view. You don’t have to lower your expectations to understand where we’re at…and to be honest about your expectations…flexible, honest, and understanding. If [supervisors] are those three things, it’ll be great.

Participants also suggested having counselor burnout and self-care more thoroughly addressed in supervision, including more discussions on balancing personal and professional responsibilities, roles, and stressors. One participant explained:

What would be really helpful when the semester first begins is one-on-one time that is direct about ‘how are you approaching this internship in balance with the rest of your life?’ ‘What are any issues that it would be worthwhile for me to know about?’ How sweet for the supervisor to see you as a whole person. And then to put out the invitation: the door’s always open.

Improvements for counselor training programs. More than half of the participants wanted a comprehensive and developmentally appropriate approach to self-care interwoven throughout their counselor training, with actual practice of self-care skills rather than “face talk.” One participant commented:

Acknowledge the reality that a graduate-level program is going to be a challenge, talking about that on the front end….[faculty] can’t just say you need to have self-care and expect [students] to be able to take that to the next level if we don’t learn it in a graduate program….how much better would it be for us to have learned how to manage that while we were in our program and gotten practice and feedback about that, and then that is so important of a skill to transfer and teach to our clients.

Most of the participants suggested the inclusion of concrete approaches to counselor self-care. Participants provided examples such as preparing students for their work as counselors-in-training by giving them an overview of program expectations at the beginning of their programs, and providing students with self-care strategies to deal with the added stressors of graduate school such as handling administrative duties during internship, searching for employment prior to graduation, and preparing for comprehensive exams.

Discussion

Findings from this study highlight the importance of the role of supervision in promoting resilience as a protective factor against burnout among counselors-in-training. The majority of participants in this study perceived that they experienced some degree of burnout in their experiences as counselors-in-training. Participants’ perceptions of experiencing burnout are a particularly meaningful finding because it indicates that these counselors-in-training see themselves as over-taxed during their education and training. If, during their master’s programs, counselors-in-training are creating professional identities based on cognitive schemas for being a counselor, then perhaps these counselors-in-training have developed schemas for counseling that include a loss of compassion for clients, diminished enthusiasm for counseling, a lopsided balance of personal and professional responsibilities, and struggles to maintain boundaries. Counselors-in-training should be aware of these potential pitfalls as these counselors-in-training reported experiencing symptoms of burnout which were rarely addressed in supervision.

In contrast to recent literature, which suggests that counselor burnout is related to overcommitment to client outcomes (Kestnbaum, 1984; Leiter, 1991; Shovholt et al., 2001), many counselor trainees in this study did not perceive that their supervisors directly addressed their degree of personal commitment to their clients’ success in counseling. Similarly, emotional exhaustion is commonly identified as a potential hazard for burnout (Barnett et al., 2007); yet, few participants believed that their supervisors directly inquired about the degree of emotional investment in their clients. Finally, elusive measures of success in counseling are often indicated as a potential factor for burnout (Kestnbaum, 1984; Skovholt, et al., 2001). The vast majority of participants interviewed for this study did not perceive that these elusive measures of success were addressed in their supervision experiences. Supervisors who are interested in thwarting counselor burnout early in the training experiences of counselors may want to consider incorporating conversations about overcommitment to client outcomes, emotional exhaustion, degree of emotional investment, and elusive measures of success into their supervision with counselors-in-training. In an effort to promote more resilient schemas and expectations for counseling work, supervisors can take an active role in helping counselors-in-training understand the importance of awareness and protective factors to protect against a lack of compassion, enthusiasm, life-work balance, and professional boundaries, similar to the way a pilot is aware that a plane crash is possible and therefore employs purposeful and effective methods of prevention and protection.

Participants in this study conceptualized self-care as purposeful behavioral efforts. Proactive behavioral choices such as reaching out to support others are ways that many counselors engage in self-care. However, self-care cannot be solely limited to engagement in specific behaviors. Self-care also should include discussions about cognitive, emotional, and spiritual coping skills. Supervisors can help counselors-in-training create a personal framework for finding meaning in their work in order to promote hardiness, resilience, and the potential for transformation (Carswell, 2011). Because of the nature of counseling, it is necessary for counselors to be open and have the courage to be transformed. Growth and transformation are often perceived as scary and something to be avoided. Yet, growth and transformation can be embraced and understood as part of each counselor’s unique professional and personal process. Supervisors can normalize and validate these experiences and help counselors-in-training narrate their inspirations and incorporate their personal, spiritual, and philosophical frameworks in their counseling. In addition, supervisors can directly address misperceptions about counseling, which often include: “I can fix the problem,” “I am responsible for client outcomes,” “Caring more will make it better,” and “My clients will always appreciate me” (Carswell, 2011). While these approaches to supervision are personal in nature, counselors-in-training in this study reported an appreciation for time spent discussing how the personal informs the professional. This finding is consistent with Bernard & Goodyear’s (1998) model of supervision which emphasizes personal development as an essential part of supervision. Models for personal development in counselor education programs have been proposed by many professionals in the field of counseling (Myers, 1991; Myers & Williard, 2003; Witmer & Granello, 2005).

Counselors-in-training in this study reported an appreciation for supervision experiences in which their supervisors provided direct feedback and positive reinforcement. Counselors-in-training often experience performance anxiety and self-doubt (Aten et al., 2008). In an effort to diminish counselor-in-training anxiety, supervisors may provide additional structure and feedback in the early stages of supervision. Once the counselor-in-training becomes more secure, the supervisor may facilitate a supervisory relationship that promotes supervisee autonomy and higher-level thinking.

The majority of participants interviewed reported a desire for supervisors to place a greater emphasis on life-work balance and learning to cope with stress. These findings suggest the importance of counselor supervisors examining their level of expressed empathy and emphasis on preventive, as well as remedial, measures to ameliorate symptoms and stressors that lead to counselor burnout. Participants expressed a need to be more informed about additional stressors in graduate school such as administrative tasks in internship, preparing for comprehensive exams, and how to search for employment. These findings suggest the need for counselor educators and supervisors to examine how they indoctrinate counselors-in-training into training programs in order to help provide realistic expectations of work and personal sacrifice during graduate school and in the counseling field. Moreover, counselor educators and supervisors should strive to provide ongoing discussions on self-care throughout the program, specifically when students in internship are experiencing expanding roles between school, site placement, and searching for future employment. As mental health professionals, counselor educators and supervisors may also struggle with their own issues of burnout; thus, attentiveness to self-care also is recommended for those who teach and supervise counselors in training.

Limitations

Findings from this study will benefit counselor educators, supervisors, and counselors-in-training; however, some limitations exist. One limitation is the lack of diversity in the sample of participants. The majority of the participants identified as Caucasian females, which is representative of the high number of enrolled females in the counseling programs approached for this study. The purpose for this study, however, was not to generalize to all counselor trainees’ experiences, but rather to shed light on how counselor perceptions of burnout and self-care are being addressed, or not, in counselor supervision.

Participant bias and recall is a second limitation of this study. Recall is affected by a participant’s ability to describe events and may be influenced by emotions or misinterpretations. This limitation was addressed by triangulating sources, including a follow-up questionnaire, reinforcing internal stability with researcher consensus on domains, core ideas, and categories, and by using an auditor to evaluate analysis and prevent researcher biases.

Conclusion

Counselors should be holders of hope for their clients, but one cannot give away what one does not possess (Corey, 2000). Counselors who lack enthusiasm for their work and compassion for their clients are not only missing a critical element of their therapeutic work, but also may cause harm to their clients. Counseling is challenging and can tax even the most “well” counselors. A lack of life-work balance and boundaries can add to the already stressful nature of being a counselor. Discussions in supervision about the potential for emotional exhaustion, the counselor-in-training’s degree of emotional investment in client outcomes, elusive measures of success in counseling, coping skills for managing stress, meaning-making and sources of inspiration, and personalized self-care activities are several ways supervisors can promote counselor resilience and sustainability. Supervisors should discuss the definitions of burnout, how burnout is different from stress, how to identify early signs of burnout, and how to address burnout symptoms in order to promote wellness and prevent burnout in counselors-in-training. Counselor educators and supervisors have the privilege and responsibility of teaching counselors-in-training how to take care of themselves in addition to their clients.

References

Aten, J. D., Madson, M. B., Rice, A., & Chamberlain, A. K. (2008). Postdisaster supervision strategies for promoting supervisee self-care: Lessons learned from hurricane Katrina. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 2(2), 75–82. doi:10.1037/1931-3918.2.2.75

Barnett, J. E., Baker, E. K., Elman, N. S., & Schoener, G. R. (2007). In pursuit of wellness: The self-care imperative. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 38(6), 603–612. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.38.6.603

Bernard, J. M., & Goodyear, R. K. (1998). Fundamentals of clinical supervision (2nd ed.). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) (2009). 2009 Standards. Retrieved from http://www.cacrep.org/ doc/2009%20standards %20with20cover.pdf

Canfield, J. (2005). Secondary traumatization, burnout, and vicarious traumatization: A review of the literature as it relates to therapists who treat trauma. Smith College Studies in Social Work, 75(2), 81–102. doi:10.1300 J497v75n02_06

Carswell, K. (2011, March). Lecture on combating compassion fatigue: Strategies for the long haul. Counseling Department, Western Carolina University, Cullowhee, NC.

Corey, G. (2000). Theory and practice of group counseling (5th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thompson Learning.

Hill, C. E., Knox, S., Thompson, S. J., Williams, E. N, Hess, S. A., & Ladany, N. (2005). Consensual qualitative research: An update. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 23(2), 196–205. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.196

Hill, C. E., Thompson, B. J., & Nutt Williams, E. (1997). A guide to conducting consensual qualitative research. The Counseling Psychologist, 25, 517–572. doi:10.1177/ 0011000097254001

Gilliland, B. E., & James, R. K. (2001). Crisis intervention strategies. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole-Thomson Learning.

Jenaro, C., Flores, N., & Arias, B. (2007). Burnout and coping in human service practitioners. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 38, 80–87. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.38.1.80

Koeske, G. F., & Kelly, T. (1995). The impact of overinvolvement on burnout and job satisfaction. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 65, 282–292. doi:10.1037/h0079622

Kestnbaum, J. D. (1984). Expectations for therapeutic growth: One factor in burnout. Social Casework: The Journal of Contemporary Social Work, 65, 374–377.

Leiter, M. (1991). The dream denied: Professional burnout and the constraints of human service organizations. Canadian Psychology, 32(4), 547–558. doi:10.1037/h0079040

Myers, J. E. (1991). Wellness as the paradigm for counseling and development. The possible future. Counselor Education and Supervision, 30, 183–193.

Myers, J. E., & Williard, K. (2003). Integrating spirituality into counselor preparation: A developmental, wellness approach. Counseling and Values, 47, 142–155.

Ponterotto, J. G. (2005). Qualitative research in counseling psychology: A primer on research paradigms and philosophy of science. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 126–136. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.196

Rosenberg, T., & Pace, M. (2006). Burnout among mental health professionals: Special considerations for the marriage and family therapist. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 32(1), 87–99. doi:10.1111/j.1752- 0606.2006.tb01590

Sherman, M. D. (1996). Distress and professional impairment due to mental health problems among psychotherapists. Clinical Psychology Review, 16, 299–315. doi:10.1016/0272- 7358(96)00016-5

Skovholt, T. M. (2001). The resilient practitioner: Burnout prevention and self-care strategies for counselors, therapists, teachers, and health professionals. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Skovolt, T. M., Grier, T. L., & Hanson, M. R. (2001). Career counseling for longevity: Self-care and burnout prevention strategies for counselor resilience. Journal of Career Development, 27(3), 167–176. doi:10.1177/089484530102700303

Truchot, D., Keirsebilck, L., & Meyer, S. (2000). Communal orientation may not buffer burnout. Psychological Reports, 86, 872–878. doi:10.2466/PR0.86.3.872-878

Witmer, J. M., & Granello, P. F. (2005). Wellness in counselor education and supervision. In J. E. Myers & T. J. Sweeney (Eds.), Counseling for wellness: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 342–361). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

E. Heather Thompson is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Counseling Western Carolina University. Melodie H. Frick is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Counseling at West Texas A & M University. Shannon Trice-Black is an Assistant Professor at the College of William and Mary. Correspondence can be addressed to Shannon Trice-Black, College of William and Mary, School of Education, PO Box 8795, Williamsburg, VA, 23187-8795, stblack@wm.edu.

Appendix A

Interview Protocol

1. What do you know about counselor burnout or how would you define counselor burnout?

2. What do you think are possible causes of counselor burnout?

3. As counselors we often are overloaded with administrative duties which may include treatment planning, session notes, and working on treatment teams. What has this experience been like for you?

4. Counseling requires a tremendous amount of empathy which can be emotionally exhausting. What are your experiences with empathy and emotional exhaustion? Can you give a specific example?

5. How do you distinguish between feeling tired and the early signs of burnout?

6. As counselors, we sometimes become overcommitted to clients who are not as ready, motivated, or willing to engage in the counseling process. Not all of our clients will succeed in the way that we want them to. How do you feel when your clients don’t grow in the way you want them to? How has this issue been addressed in supervision?

7. What is your perception of how your supervisors have dealt with stress?

8. How has counselor burnout been addressed in supervision?

prompt: asked about, evaluated, provided reading materials, and how often

9. How have specific issues related to burnout been addressed in supervision such as: (a) over-commitment to clients who seem less motivated to change, (b) emotional exhaustion, and (c) elusive measures of success?

10. How could supervision be improved in addressing counselor burnout?

prompt: asked about, evaluated, provided reading materials, modeled by supervisor

11. What do you know about self-care or how would you define self-care for counselors?

12. What are examples of self-care, specifically ones that you use as counselors-in-training?

13. How has counselor self-care been addressed in supervision?

14. Sometimes we have to say “no.” How would you characterize your ability to say “no?” What have you learned in supervision about setting personal and professional boundaries?

15. What, if any, discussions have you had in supervision about your social, emotional, spiritual, and/or physical wellbeing? What is a specific example?

16. How could supervision be improved in addressing counselor self-care?

prompt: asked about, provided reading materials, modeled by supervisor

17. How could your overall counselor training be improved in addressing counselor burnout and counselor self-care?

Appendix B

Follow-Up Questionnaire

How would you describe counselor burnout?

How has counselor burnout been addressed in supervision?

How could supervision be improved in addressing counselor burnout?

How would you describe self-care for counselors?

How has counselor self-care been addressed in supervision?

How could supervision be improved in addressing counselor self-care?

How could your overall counselor training be improved in addressing counselor burnout and counselor self-care?

Sep 5, 2014 | Article, Volume 1 - Issue 3

John McCarthy

Academic preparation is essential to the continued fidelity and growth of the counseling profession and clinical practice. The accreditation of academic programs is essential to ensuring the apposite education and preparation of future counselors. Although the process is well documented for counselors-in-training in the United States, there is a dearth of literature describing the academic preparation of counselors in the United Kingdom and Ireland. This article describes interview findings from six counseling programs at institutions in England and Ireland: Cork Institute of Technology; the University of East Anglia; the University of Cambridge; the University of Limerick; The University of Manchester; and West Suffolk College. It also discusses common and differentiating themes with counselor training in the U.S.

Keywords: accreditation, international, counselors-in-training, England, Ireland

Academic preparation lies at the heart of the counseling profession and is a vital ingredient to professional practice. Most people identifying themselves as professional counselors possess a minimum of a master’s degree in counseling, and as a result of the varied roles and settings in which they work, the academic training for such professionals is broad-based in common domains. Most counseling graduate programs typically offer coursework reflective of a core curriculum, field placement, and a specialty area (Neukrug, 2007).

Program accreditation also influences preparation. The Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) and the Council on Rehabilitation Education (CORE) represent two accrediting bodies in the counseling profession. The most recent CACREP Standards were developed “to ensure that students develop a professional counselor identity and master the knowledge and skills to practice effectively” (CACREP, 2009, p. 2). Eight core areas of curriculum are required of all CACREP-accredited programs: Professional Orientation and Ethical Practice; Social and Cultural Diversity; Human Growth and Development; Career Development; Helping Relationships; Group Work; Assessment; and Research and Program Evaluation. Furthermore, as Neukrug (2007) pointed out, many master’s-level counseling programs include a specialty area recognized by CACREP.

At the same time, international issues in counseling have drawn considerable interest in the past two decades. Pedersen and Leong (1997) outlined the global need for counseling as a result of urbanization and modernization throughout the world. The twelfth edition of Counselor Preparation was the first in the series to offer a chapter about counselor training outside of the U.S. (Schweiger, Henderson, & Clawson, 2008). More recent articles have examined counseling issues in such nations as Turkey (Stockton & Güneri, 2011), Mexico (Portal, Suck, & Hinkle, 2010), and Italy (Remley, Bacchini, & Krieg, 2010). The pace of the counseling profession internationally is rapid, prompting a need “to expand the knowledge basis of counseling as a profession internationally” (Stockton, Garbelman, Kaladow, & Terry, 2008, p. 78).

Despite the interest in international issues, the literature specific to the United Kingdom and Ireland—particularly related to counselor preparation—is somewhat limited. According to Syme (1994), counseling in Britain dates back to the 1940s. Initially such training was limited to priests, youth workers, and volunteers of the National Marriage Guidance Council. University counseling courses started in the 1950s. Growth among counselors working independently (i.e., counseling privately) was observed in the 1960s, and this trend in part resulted in the creation of the Standing Conference for the Advancement of Counselling in 1970.

In regard to the development of school counseling in England, Shertzer and Jackson (1969) noted that four counselor training facilities existed in the country at that time, producing about 100 counselors per year. In discussing various differential factors between the two countries, they pointed out that school counseling in the U.S. had benefited from federal government support, while in England the national government had taken a more neutral stance. Not long thereafter, Hague (1976) indicated that British professionals viewed the development of the profession as lagging behind that of the U.S. It also was during this decade that counselors from the U.S. had a “profound influence” on developments in the UK (Syme, 1994, p. 10). Awareness of counseling grew during the 1980s, a period in which counselors worked in the voluntary and private sectors as well as most universities and even larger companies (Syme).

Citing the 1993 edition of the Counselling and Psychotherapy Resources Directory that was published by the British Association of Counselling, Syme (1994) reported that approximately 600 counselors were listed in the London area, while far fewer were found in other areas of the UK. Around this period of time, counseling in independent practice had become “an attractive career,” though “an ever-present danger of standards being eroded in some areas of Britain where demand exceeds supply” existed (p. 15).

Dryden, Mearns, and Thorne (2000) also offered an extensive perspective of counseling in the UK dating to the World War II era. The British Association of Counselling (BAC), which emerged in 1976 and included members from the Association for Student Counselling and the Association for Pastoral Care and Counselling, played a pivotal role in the early development of the counseling profession. (The BAC has subsequently become the British Association of Counselling and Psychotherapy). Important contributions came from the educational system and voluntary sector. Dryden et al. summarized the historical foundations: “It is not perhaps altogether fanciful to see the history of counseling in Britain as the story of a collaborative response by widely differing people from different sectors of the community to human suffering engendered by social change and shifting value systems” (p. 471). In the early stages of development, counseling was not viewed as a profession, but rather as something that individuals performed with little or no training that was subsumed by another profession (Dryden et al.).

Dryden et al. (2000) noted that the BAC had begun to accredit counseling programs in 1988. Furthermore, it also had developed an expanded and detailed code of ethics that included supervision and training and had created guidelines for programs seeking accreditation. Altogether the profession had become “significant” in that it now was making noteworthy “demands on the budgets of the social and health services” (p. 476). They further speculated that the greatest inroads in counseling were made in the workplace, particularly regarding job-related stress. As counseling entered the 21st century in Britain, it had reached a “critical but dynamic point” in its development, as it was aiming to “maintain its humanity in its attitudes to both clients and practitioners” (p. 477).

Accreditation

Various accreditation bodies exist in this region. Among the UK programs, two foremost organizations are the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy (BACP), and the United Kingdom and European Association for Psychotherapeutic Counselling (UKEAPC).

The British Association of Counselling and Psychotherapy (BACP), formerly named the British Association for Counselling, was formed in 1977 and arose from the Standing Conference for the Advancement of Counselling (BACP, 2011). Its name was modified in September 2000 in acknowledgement of counselors’ and psychotherapists’ desire to belong to a unified profession that met the common interests of both groups (University of Cambridge Faculty of Education, 2010). BACP’s mission is to “enable access to ethical and effective psychological therapy by setting and monitoring of standards” (Welcome from BACP, 2011). BACP accredits individual practitioners, counseling services, and training courses. Nearly 9000 counselors and psychotherapists are accredited by BACP (Counsellor/Psychotherapist accreditation scheme, 2010).

To become accredited, individuals must meet eight criteria, which include the completion of a BACP-accredited training course and a minimum of three years of practice prior to the application. Candidates must have had 450 supervised hours within the past 3–6 years, 150 of which came after their academic training, along with a minimum of 1.5 hours of supervision/month during this period. (An alternative route is provided and included in the BACP Standard for Accreditation.) Other criteria address continuing professional development; self-awareness; and knowledge and understanding of theories along with practice and supervision (BACP, 2009).

BACP began the recognition of training course standards in 1988, and over 120 courses have been recognized or accredited. Courses must include a mix of elements that include knowledge-based learning; competencies in therapy; self-awareness; professional development; skills work; and placements regarding practice (BACP, 2009).

BACP’s most recent framework in ethics, the Ethical Framework for Good Practice in Counselling & Psychotherapy (BACP, 2010), replaced earlier ethical codes. Aimed at guiding practice in counseling and psychotherapy for BACP members, the Framework also was produced to “inform the practice of closely related roles that are delivered in association with counselling and psychotherapy or as part of the infrastructure to deliver these services” (p. 02). The Framework features sections on values and ethical principles in counseling and psychotherapy. It also is highlighted by a section related to the personal moral qualities of counselors, who are encouraged to possess such characteristics as resilience, humility, wisdom, empathy, and courage.

The United Kingdom and European Association for Psychotherapeutic Counselling (UKEAPC) is an organization that “regulates and monitors the standards of training and quality of delivery of its Member Training Organizations” (UKEAPC Home page, 2011). It was founded in 1996 and underwent a modification in its name in 2010 to include member organizations in Europe (UKEAPC Name Change, 2010). Member organizations can include universities and training programs in the private sector and it is designed for programs at the post-graduate level or the equivalent thereof (Home Page, 2011).

UKEAPC defines psychotherapeutic counseling as a “form of counselling in depth which adopts a relational-developmental focus with the goal of fostering the client’s personal growth and development, in the context of their life and current circumstances” (UKEAPC What is Therapeutic Counselling?, 2011). It also involves the counselor’s use of self; competence in interventions, assessment, and diagnosis; an understanding of efficacy within the psychotherapeutic relationship; competence in abilities to guide clients toward their existential potential; ability to work with other healthcare professionals; and a commitment to ongoing professional development (UKEAPC).

Trainees in psychotherapeutic counseling programs must meet certain criteria to be considered for acceptance into UKEAPC. In addition to possessing a personality that can maintain stability in a psychotherapeutic relationship, candidates also should be living a life consistent with personal ethics; possess experience in responsible roles in working with people; and have an educational background to enable her/him to cope with academic demands at the postgraduate/graduate level (UKEAPC Training Standards, 2011).

Graduate training programs meeting UKEAPC standards are a minimum of three years in duration along with 450 hours devoted to skills and theory and 300 hours dedicated to supervised work with clients. Four components are deemed to be necessary: personal therapy; clinical practice; supervised practice; and a comprehension of theories. A trainee must have at least 40 hours/year of personal therapy, equating to 120 hours by the conclusion of the program. A final evaluation that assesses theoretical comprehension and clinical competence must also be given. Training programs are responsible for publishing the code of ethics/professional practice to which it adheres; this code must be consistent with the corresponding codes of UKEAPC (UKEAPC Training Standards, 2011).

Programs also must include the following curricular items: theory, practice, and range of approaches of psychotherapeutic counseling; relevant studies in human development, sexuality, ethics, research, and human sciences; social and cultural influences in psychotherapeutic counseling; the provision of a placement in mental health; supervised psychotherapeutic counseling practice; identification/management of the trainee’s involvement in personal psychotherapeutic counseling; the ability to refer to other professionals when deemed necessary; legal issues; research skills; and a written product that displays a trainee’s ability to communicate professionally. Full member organizations also must have a professional development policy consistent with UKEAPC (UKEAPC Training Standards, 2011).

In regard to Ireland, guidance was made “a universal entitlement in post primary schools” in Ireland through the adoption of the Education Act (1998). Additional professionals are given to each school by the Department of Education and Skills for the purpose of guidance. They range from eight hours in smaller schools with an enrollment of less than 200 students to approximately two full-time posts in larger schools with an enrollment of 1,000 students or more (National Centre for Guidance in Education, 2011).

The National Centre for Guidance and Education (NCGE), an agency of the Irish Department of Education and Science, aims to “support and develop guidance practice in all areas of education and to inform the policy of the Department in the field of guidance” (National Centre for Guidance in Education, 2011). The Centre provides support for guidance professionals in the school setting, such as guidance counselors and practitioners in second and third level schools and in adult education. It fosters such support through an array of activities, including though not limited to the development of guidance resources, the dissemination of information on good guidance practice, and offering support for innovative projects in guidance (National Centre for Guidance in Education, 2011). Training in Whole School Guidance Planning also is administered through professional development workshops (NCGE, Whole School Guidance, 2011).

Established in 1968, the Institute of Guidance Counsellors (IGC) in Ireland represents over 1200 professionals in second-level schools as well as third level colleges, guidance services in adult settings, and private practice. IGC serves as a liaison and an advocate in its work with government, institutions of higher education, and other organizations (Welcome to the ICG, 2011). It also offers a Code of Ethics (Coras Eitice–Code of Ethics, 2011).

The purpose of this study was to examine counselor preparation at selected institutions of higher education in England and Ireland from a comparative standpoint to that in the United States. In my search of the literature, no recent journal article has addressed this topic. The rationale behind this study is not only to enlighten U.S. counselor educators in learning more about another system of preparation, but also to aid them in their own programmatic considerations regarding such areas as philosophy, training emphases, and student involvement. One of the critical fundamental questions in the interviews echoed Stockton et al.’s (2008) discussion of international counselor training: “What are the critical variables that shape these programs?” (p. 84).

Data Collection

This research project was approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board prior to the collection of data, which took place during the author’s sabbatical in the spring semester of 2011. Institutions offering graduate training in counseling were asked to participate based on, for the most part, a convenience factor. Three of them were in proximity to the base of my sabbatical, the University of Cambridge. The two programs in Ireland were also sought due to their propinquity. This sample was clearly not exhaustive and was not intended to be meant as comprehensive in any way. However, it is interesting to note that the institutions included in this study do vary in both size and type of institution.

Possible participation was initially sought in one of two ways: After identifying a faculty member or course director from a website search, I emailed the respective counselor educator, outlined my proposed study, and asked for participation. In other instances, I spoke to the course director directly. The informed consent was shared or sent for their review, and a copy of the completed consent was given to participants at the actual interview. All interviews were done in person and were informal in structure. Drafts of each course summary in the data section were sent to one of the interviewees at each institution for feedback on the clarity and accuracy of the content as well as overall approval.

Interviewees in the study were Dr. Judy Moore, Director of the Centre for Counselling Studies, University of East Anglia (England); Dr. Steve Shaw, Course Director (Access Course) (Counselling), West Suffolk College (England); Dr. Lucy Hearne, Programme Director, University of Limerick (Ireland); Mr. Tom Geary, Lecturer, Programme Director, University of Limerick (Ireland); Dr. Terry Hanley, Director of MA (January intake), University of Manchester (England); Dr. Colleen McLaughlin, Course Director (MEd), University of Cambridge (England); and Mr. Gus Murray, Lecturer in Counselling, Cork Institute of Technology (Ireland).

Terminology

In understanding the approach to counselor training in this region, I found some differing language that is reflected in parts of this article. First, for the most part, a “course” would not mean an individual class, as it might be used in the U.S., but rather a course of study or program. Second, instead of “faculty/faculty members” or “department,” I tended to hear “course team” or “members of staff” to describe the equivalent. Third, “course members” was often used in place of “students.” Fourth, instead of being headed by a “department chair,” a faculty member with the title of “course director” oversaw each individual program. Finally, “accreditation” was used to mean both course of study approval by an outside body as well as approval of an individual’s educational work (i.e., certification). In other words, a trainee in England could seek accreditation by, for instance, the BACP.

Data

This section offers an overview of the respective courses included in the study and represents data taken from the interviews as well as from course/university materials and/or websites. Each course summary is designed to reflect pertinent facets of the courses, including the curriculum and any unique elements. A background of the institution also is featured.

University of Limerick (UL)

Located five kilometers from Limerick City, the University of Limerick has an enrollment of approximately 11,600 students (University of Limerick, 2010). Designed around IGC guidelines, its Graduate Diploma in Guidance Counselling program is part-time in enrollment and two full years in duration. Its primary objective is to train practicing teachers and other related professionals to become Guidance Counsellors, and the program’s qualification is recognized by the Department of Education and Skills in Ireland for the aim of gaining an appointment as a Guidance Counsellor at a second-level school (i.e., high school). It is also recognized by the Institute of Guidance Counsellors, Ireland. To be considered for admission, an individual must have an undergraduate degree and/or an approved teaching qualification or an acceptable level of experience and interest in the area. Applicants also are interviewed prior to the admission decision (University of Limerick, n.d.-b).

Interviews and course materials. Started 12 years ago, the Graduate Diploma in Guidance Counselling at the University of Limerick is housed in the Department of Education and Professional Studies. Faculty members include other UL faculty who primarily teach in other academic areas as well as 6–8 part-time lecturers. The diploma program is offered in 2–3 “outreach centres” throughout Ireland, each of which has a link-in coordinator who liaises with the programme directors and students. Other key personnel include process educators, who aid in teaching theories and skills development; placement tutors, who are retired guidance counselors who serve as supervisors during students’ placements; and mentors, who share their expertise with students on a voluntary basis during the students’ placements. Approximately 18–20 trainees are accepted in a cohort in each of the centres. The diploma program has 325 graduates to date with another 80 trainees to be graduating in January, 2012 (T. Geary & L. Hearne, personal communication, April 4, 2011).

The program is comprised of 10 taught modules, a research project, and a placement in an educational setting. On average, students’ classroom time for the initial three semesters is six hours/week. A portion of the program is offered on two intensive residential weekend sessions. This portion is done in the first and third semesters and emphasizes experiential group work as a way to enhance trainees’ skills. In the third semester, the classtime is decreased to about three hours/week to enable students to complete their research projects (University of Limerick, n.d.-b; T. Geary & L. Hearne, personal communication, April 4, 2011).

Courses in “Counselling Theory and Practice” are taken in both the first and second years. Additional courses in the initial year include those in the areas of human development, career development, group processes, research methods, and assessment. The second year features placements in both educational and industrial settings, the latter of which is brief (five days) and intended to give exposure to alternative guidance counseling settings. Placements are marked on a pass/fail basis. The final year also includes a research project and coursework in guidance in adult/continuing education, educational issues, professional practice, and the psychology of work (University of Limerick, n.d.-b; T. Geary & L. Hearne, personal communication, April 4, 2011).

The University of Limerick program has been described as “a course with psychological emphasis….focusing on the psychological aspects of guidance counseling” and where “the standard and focus on the personal counselling dimension is emphasized” (Geary & Liston, 2009, p. 7). Consistent with this approach, students are required to pursue their own personal therapy. This experience occurs in each first academic year and must be at least 10 sessions in length. Trainees pay for their own therapy and have to submit a letter from the professional confirming the trainee’s attendance (T. Geary & L. Hearne, personal communication, April 4, 2011).

Trainees at UL pursue competency in the various modules through coursework, including a two-week summer school session at the end of the first academic year. Successful completion of a module, each of which has two units, is reflected in evaluative rubrics. They also have two tutorials per semester in which a programme director meets with a group of students to offer a brief presentation on a topic such as writing skills or to discuss trainees’ concerns in relation to their course work. The minor dissertation in the second year requires students to investigate a topic as a practitioner– researcher. Trainees develop the research proposal through the course on research methods taken in the summer school session in the first year. The topic must be related to guidance counseling, and the completed project is submitted at the end of September in their second year for a graduation the subsequent January (T. Geary & L. Hearne, personal communication, April 4, 2011). Finally, elements of the program have been presented at three recent conferences in Finland (Geary & Liston, 2009), the UK (Liston & Geary, 2009), and Canada (Liston & Geary, 2010), and a qualitative/quantitative assessment of UL graduates’ career paths, professional roles, and professional development needs has been planned (Geary & Liston, 2009).

Finally, a Master of Arts in Guidance Counselling was started Fall 2011 (L. Hearne, personal communication, 27 May 2011; University of Limerick, n.d.-c). Focusing on personal, social, educational, and vocational issues through contemporary perspectives, the post-graduate degree program is designed to “advance graduates of initial guidance counselling programmes” and to “build on their knowledge, skills and competencies in the field” (University of Limerick, n.d.-a). The 12-month, part-time programme will be offered only at the main campus for the time being. Five modules and a dissertation will be required and work-related experiences and supervision also will be integral parts of the course of study. Coursework will cover advanced research methods; advanced counseling theory and practice; two practica (the first of which is on critical perspectives in the field and the second of which is on a case study); and guidance planning.

Cork Institute of Technology (CIT)

CIT has approximately 12,000 students, about half of whom are enrolled full-time, across four separate campuses. The main campus is located in Bishopstown, west of Cork City (Facts and Figures, n.d.). It features a part-time Counselling and Psychotherapy program that leads to a BA (Honours) degree (Cork Institute of Technology, 2011). A part of this degree can include two certifications: Students completing the first year earn a Counselling Skills Certificate in Counselling Skills, herein referred to as the “initial Certificate.” Similarly, individuals earn a Higher Certificate in Arts in Counselling Skills upon finishing the second year. Both years involve part-time enrollment. The BA (Honours) degree is four years in length and is accomplished through successful completion of the third and fourth years (CIT, Counselling Skills Certificate, 2011).

Interview and course materials. The initial Certificate program is described as “an introductory training in Counselling for use in their existing work or life situations” (CIT, Counselling Skills Certificate, 2011). Individuals must be at least 25 years old and submit two written references and also are assessed through an interview. In addition, the importance of dual relationships is outlined on the website for the Certificate:

…Due to the personal and experiential nature of the course, it is generally not possible to have staff or students with significant existing personal or professional relationships in the same course group. Where possible, every effort is made to overcome this difficulty by placing them in separate groups. Oftentimes this solution is not possible and in these instances, the dual relationship may prevent the applicant from being offered a place on the course at that time (CIT, Counselling Skills Certificate, 2011).

Five courses are offered each semester. Students enroll in coursework on family systems theory and application, counseling skills, mindfulness, and experiential group process in their initial semester. Trainees in the final half of the certification program take courses on person-centered counseling theory and application; developmental theory; and a second course in both counseling skills and experiential group process. Successful completion is based on an evaluation of written, practical, and experiential assignments (CIT Program outcomes, 2011). By earning this Certificate, graduates should be enabled to practice counseling skills within their “existing roles.” Furthermore, the website clearly states that the Certificate is not a professional qualification within Counselling and “does not qualify the holder to practice as a professional counsellor” (CIT, Counselling Skills, 2011).

The Higher Certificate is predicated upon completion of the initial Certificate and has similar admissions requirements (CIT, Counselling Skills, 2011). The goal is to build upon the foundation in the initial Certificate so that individuals can use the skills in existing employment or volunteer work. It also serves as an entry into the BA Honours degree in the subsequent third and fourth years (CIT, Counselling Skills, 2011). Eight modules are outlined and described in detail in a rubric format and are based on various knowledge, skills and competencies (CIT, Higher Certificate, 2011). Content in the Higher Certificate is highlighted by continued work in group process and counseling skills. However, another feature that differentiates the Higher Certificate from the Certificate is an emphasis on theory and application of ego states and life scripts (CIT, Higher Certificate, 2011). Though completion does not permit individuals to practice as a professional counselor, it does enable them to practice a full range of counselling skills within an existing role (CIT, Counselling Skills, 2011).

The Certificate program was developed in 1991. At any given time, about 140 students are enrolled in the various segments of the CIT training: approximately 60 in the first year, 36 in the second year, and 24 in the third and fourth years. Trainees are not guaranteed admission among the various levels. In other words, completion of the initial Certificate does not translate into an automatic admission into the Higher Certificate (year 2). Though the minimum age of 25 is set as admissions criterion for both Certificate programs, the average age of admitted students is generally closer to 35, as life experience and maturity are valued in terms of the development of therapeutic relationships by the trainees. A written self-appraisal and two interviews (group and individual) are also a part of the admissions process. In addition, it was noted that many students enter the CIT program having first been in other professions (G. Murray, personal communication, April 5, 2011).

Years 3 and 4 of the BA (Honours) degree support the practice of counseling with the final year stressing the integration of modalities. Staff members coordinate and often identify the trainees’ placements, which often take place at universities, high schools, primary schools, community projects, and alternative centers. Students are supervised individually and accumulate a minimum of 100 placement hours over the four years (G. Murray, personal communication, April 5, 2011). By their graduation, students must have completed a minimum of 100 hours of personal counseling (G. Murray, personal communication, October 10, 2011). The CIT program also has about 15 instructors, most of whom are part-time, that assist with the training (G. Murray, personal communication, April 5, 2011). A Master’s degree was also instituted in Fall 2011 (G. Murray, personal communication, October 10, 2011).

Most graduates of the BA (Honours) degree progress in their work area as a result of their advanced training, as they may get a promotion or secure a more counseling-related position in their workplace. Private practice is another possible route for graduates. Additional hours are needed after graduation for individuals to meet accreditation standards (G. Murray, personal communication, April 5, 2011).

University of Cambridge