Feb 26, 2021 | Volume 11 - Issue 1

Priscilla Rose Prasath, Peter C. Mather, Christine Suniti Bhat, Justine K. James

This study examined the relationships between psychological capital (PsyCap), coping strategies, and well-being among 609 university students using self-report measures. Results revealed that well-being was significantly lower during COVID-19 compared to before the onset of the pandemic. Multiple linear regression analyses indicated that PsyCap predicted well-being, and structural equation modeling demonstrated the mediating role of coping strategies between PsyCap and well-being. Prior to COVID-19, the PsyCap dimensions of optimism and self-efficacy were significant predictors of well-being. During the pandemic, optimism, hope, and resiliency have been significant predictors of well-being. Adaptive coping strategies were also conducive to well-being. Implications and recommendations for psychoeducation and counseling interventions to promote PsyCap and adaptive coping strategies in university students are presented.

Keywords: university students, psychological capital, well-being, coping strategies, COVID-19

In January 2020, the World Health Organization declared the outbreak of a new coronavirus disease, COVID-19, to be a public health emergency of international concern, and the effects continue to be widespread and ongoing. For university students, the pandemic brought about disruptions to life as they knew it. For example, students had to stay home, adapt to online learning, modify internship placements, and/or reconsider graduation plans and jobs. The aim of this study was to understand how the sudden changes and uncertainty resulting from the pandemic affected the well-being of university students during the early period of the pandemic. Specifically, the study addresses coping strategies and psychological capital (PsyCap; F. Luthans et al., 2007) and how they relate to levels of well-being.

University Students and Mental Health

Although mental health distress has been an issue on college campuses prior to the pandemic (Flatt, 2013; Lipson et al., 2019), COVID-19 has and will continue to magnify this phenomenon. Experts are projecting increases in depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicide in the United States (Wan, 2020). Johnson (2020) indicated that 35% of students reported increased anxiety associated with a move from face-to-face to online learning in the spring 2020 semester, matching the early phases of the COVID-19 outbreak. Stress associated with adapting to online learning presented particular challenges for students who did not have adequate internet access in their homes (Hoover, 2020).

Researchers have reported that high levels of technology and social media use are associated with depression and anxiety among adolescents and young adults (Huckins et al., 2020; Primack et al., 2017; Twenge, 2017). Given the current realities of physical distancing, there are fewer opportunities for traditional-age university students attending primarily residential campuses to maintain social connections, resulting in social fragmentation and isolation. Research has demonstrated that this exacerbates existing mental health concerns among university students (Klussman et al., 2020).

The uncertainties arising from COVID-19 have added to anticipatory anxiety regarding the future (Ray, 2019; Witters & Harter, 2020). From the Great Depression to 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina, victims of these life-shattering events have had to deal with their present circumstances and were also left with worries about how life and society would be inexorably altered in the future. University students are dealing with uncertain current realities and futures and may need to bolster their internal resources to face the challenges ahead. In this context, positive coping strategies and PsyCap may be increasingly valuable assets for university students to address the psychological challenges associated with this pandemic and to maintain or enhance their well-being.

Coping Strategies

Coping is often defined as “efforts to prevent or diminish the threat, harm, and loss, or to reduce associated distress” (Carver & Connor-Smith, 2010, p. 685). There are many ways to categorize coping responses (e.g., engagement coping and disengagement coping, problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping, accommodative coping and meaning-focused coping, proactive coping). Engagement coping includes problem-focused coping and some forms of emotion-focused coping, such as support seeking, emotion regulation, acceptance, and cognitive restructuring. Disengagement coping includes responses such as avoidance, denial, and wishful thinking, as well as aspects of emotion-focused coping, because it involves an attempt to escape feelings of distress (Carver & Connor-Smith, 2010; de la Fuente et al., 2020). Findings on the effectiveness of problem-focused coping strategies versus emotion-focused coping strategies suggest the effectiveness of the particular strategy is contingent on the context, with controllable issues being better addressed through problem-focused strategies, while emotion-focused strategies are more effective with circumstances that cannot be controlled (Finkelstein-Fox & Park, 2019). In general, problem-focused coping strategies, also known as adaptive coping strategies, include planning, active coping, positive reframing, acceptance, and humor (Carver & Connor-Smith, 2010). Other coping strategies, such as denial, self-blame, distraction, and substance use, are more often associated with negative emotions, such as shame, guilt, lower perception of self-efficacy, and psychological distress, rather than making efforts to remediate them (Billings & Moos, 1984). These strategies can be harmful and unhealthy with regard to effectively coping with stressors. Researchers have recommended coping skills training for university students to modify maladaptive coping strategies and enhance pre-existing adaptive coping styles to optimal levels (Madhyastha et al., 2014).

Flourishing: The PERMA Well-Being Model

Positive psychologists have asserted that studies of wellness and flourishing are important in understanding adaptive behaviors and the potential for growth from challenging circumstances (Joseph & Linley, 2008; Seligman, 2011). Flourishing (or well-being) is defined as “a dynamic optimal state of psychosocial functioning that arises from functioning well across multiple psychosocial domains” (Butler & Kern, 2016, p. 2). Seligman (2011) proposed a theory of well-being stipulating that well-being was not simply the absence of mental illness (Keyes, 2002), but also the presence of five pillars with the acronym of PERMA (Seligman, 2002, 2011). The first pillar, positive emotion (P), is the affective component comprising the feelings of joy, hope, pleasure, rapture, happiness, and contentment. Next are engagement (E), the act of being highly interested, absorbed, or focused in daily life activities, and relationships (R), the feelings of being cared about by others and authentically and securely connected to others. The final two pillars are meaning (M), a sense of purpose in life that is derived from something greater than oneself, and accomplishment (A), a persistent drive that helps one progress toward personal goals and provides one with a sense of achievement in life. Seligman’s (2011) PERMA model is one of the most highly regarded models of well-being.

Seligman’s multidimensional model integrates both hedonic and eudaimonic views of well-being, and each of the well-being components is seen to have the following three properties: (a) it contributes to well-being, (b) it is pursued for its own sake, and (c) it is defined and measured independently from the other components (Seligman, 2011). Studies show that all five pillars of well-being in the PERMA model are associated with better academic outcomes in students, such as improved college life adjustment, achievement, and overall life satisfaction (Butler & Kern, 2016; DeWitz et al., 2009; Tansey et al., 2018). Additionally, each pillar of PERMA has been shown to be positively associated with physical health, optimal well-being, and life satisfaction and negatively correlated with depression, fatigue, anxiety, perceived stress, loneliness, and negative emotion (Butler & Kern, 2016). At a time of significant stress, promoting the highest human performance and adaptation not only helps with well-being in the midst of the challenge but also can provide a foundation for future potential for optimal well-being (Joseph & Linley, 2008).

Psychological Capital (PsyCap)

PsyCap is a state-like construct that consists of four dimensions: hope (H), self-efficacy (E), resilience (R), and optimism (O), often referred to by the acronym HERO (F. Luthans et al., 2007). F. Luthans et al. (2007) developed PsyCap from research in positive organizational behavior and positive psychology. PsyCap is defined as an

individual’s positive psychological state of development characterized by (1) having confidence (self-efficacy) to take on and put in the necessary effort to succeed at challenging tasks; (2) making a positive attribution (optimism) about succeeding now and in the future; (3) persevering toward goals and, when necessary, redirecting paths to goals (hope) in order to succeed; and (4) when beset by problems and adversity, sustaining and bouncing back and even beyond (resilience) to attain success. (F. Luthans et al., 2015, p. 2)

Over the past decade, PsyCap has been applied to university student development and mental health. There is robust empirical support suggesting that individuals with higher PsyCap have higher levels of performance (job and academic); satisfaction; engagement; attitudinal, behavioral, and relational outcomes; and physical and psychological health and well-being outcomes. Further, they have negative associations with stress, burnout, negative health outcomes, and undesirable behaviors at the individual, team, and organizational levels (Avey, Reichard, et al., 2011; Newman et al., 2014). Researchers have also examined the mediating role of PsyCap in the relationship between positive emotion and academic performance (Carmona-Halty et al., 2019; Hazan Liran & Miller, 2019; B. C. Luthans et al., 2012; K. W. Luthans et al., 2016); relationships and predictions between PsyCap and mental health in university students (Selvaraj & Bhat, 2018); and relationships between PsyCap, well-being, and coping (Rabenu et al., 2017).

Aim of the Study and Research Questions

The aim of the current study was to examine the relationships among well-being in university students before and during the onset of COVID-19 with PsyCap and coping strategies. The following research questions guided our work:

- Is there a significant difference in the well-being of university students prior to the onset of COVID-19 (reported retrospectively) and after the onset of COVID-19?

- What is the predictive relationship of PsyCap on well-being prior to the onset of COVID-19 and after the onset of COVID-19?

- Do coping strategies play a mediating role in the relationship between PsyCap and well-being?

Method

Participants

A total of 806 university students from the United States participated in the study. After cleaning the data, 197 surveys were excluded from the data analyses. Of the final 609 participants, 73.7% (n = 449) identified as female, 22% (n = 139) identified as male, and 4.3% (n = 26) identified as non-binary. The age of participants ranged from 18 to 66 (M = 27.36, SD = 9.9). Regarding race/ethnicity, most participants identified as Caucasian (83.6%, n = 509), while the remaining participants identified as African American (5.3%, n = 32), Hispanic or Latina/o (9.5%, n = 58), American Indian (0.8%, n = 5), Asian (3.6%, n = 22), or Other (2.7%, n = 17). Fifty-four percent of the participants were undergraduate students (n = 326), and the remaining 46% were graduate students (n = 283). The majority of the participants were full time students (82%, n = 498) compared to part-time students (18%, n = 111). Sixty-three percent of the students were employed (n = 384) and the remaining 37% were unemployed (n = 225).

Data Collection Procedures

After a thorough review of the literature, three standardized measures were identified for use in the study along with a brief survey for demographic information. Instruments utilized in the study measured psychological capital (Psychological Capital Questionnaire [PCQ-12]; Avey, Avolio et al., 2011), coping (Brief COPE; Carver, 1997), and well-being (PERMA-Profiler; Butler & Kern, 2016). Data were collected online in May and June 2020 using Qualtrics after obtaining approval from the IRBs of our respective universities. An invitation to participate, which included a link to an informed consent form and the survey, was distributed to all university students at two large U.S. public institutions in the Midwest and the South via campus-wide electronic mailing lists. The survey link was also distributed via a national counselor education listserv, and it was shared on the authors’ social media platforms. Participants were asked to complete the well-being assessment twice—first, by responding as they recalled their well-being prior to COVID-19, and second, by responding as they reflected on their well-being during the pandemic.

Instruments

Demographic Questionnaire

A brief questionnaire was used to capture participant information. The questionnaire included items related to age, gender, race/ethnicity, relationship status, education classification, and employment status.

Psychological Capital Questionnaire – Short Version (PCQ-12)

The PCQ-12 (Avey, Avolio et al., 2011), the shortened version of PCQ-24 (F. Luthans et al., 2007), consists of 12 items that measure four HERO dimensions: hope (four items), self-efficacy (three items), resilience (three items), and optimism (two items), together forming the construct of psychological capital (PsyCap). The PCQ-12 utilizes a 6-point Likert scale with response options ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients as a measure of internal consistency of the HERO subscales in the current study were high—hope (α = .86), self-efficacy (α = .86), resilience (α = .73), and optimism (α = .83)—consistent with the previous studies.

Brief COPE Questionnaire

Coping strategies were evaluated using the Brief COPE questionnaire (Carver, 1997), which is a short form (28 items) of the original COPE inventory (Carver et al., 1989). The Brief COPE is a multidimensional inventory used to assess the different ways in which people generally respond to stressful situations. This instrument is used widely in studies with university students (e.g., Madhyastha et al., 2014; Miyazaki et al., 2008). Fourteen conceptually differentiable coping strategies are measured by the Brief COPE (Carver, 1997): active coping, planning, using emotional support, using instrumental support, venting, positive reframing, acceptance, denial, self-blame, humor, religion, self-distraction, substance use, and behavioral disengagement. The 14 subscales may be broadly classified into two types of responses—“adaptive” and “problematic” (Carver, 1997, p. 98). Each subscale is measured by two items and is assessed on a 5-point Likert scale. Thus, in general, internal consistency reliability coefficients tend to be relatively smaller (α = .5 to .9).

PERMA-Profiler

The PERMA-Profiler (Butler & Kern, 2016) is a 23-item self-report measure that assesses the level of well-being across five well-being domains (i.e., positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, accomplishment) and additional subscales that measure negative emotion, loneliness, and physical health. Each item is rated on an 11-point scale ranging from never (0) to always (10), or not at all (0) to completely (10). The five pillars of well-being are defined and measured separately but are correlated constructs that together are considered to result in flourishing (Seligman, 2011). A single overall flourishing score provides a global indication of well-being, and at the same time, the domain-specific PERMA scores provide meaningful and practical benefits with regard to the possibility of targeted interventions. The measure demonstrates acceptable reliability, cross-time stability, and evidence for convergent and divergent validity (Butler & Kern, 2016). For the present study, reliability scores were high for four pillars—positive emotion (α = .88), relationships (α = .83), meaning (α = .89), accomplishment (α = .82); high for the subscales of negative emotion (α = .73) and physical health (α = .85); and moderate for the pillar of engagement (α = .65). The overall reliability coefficient of well-being items is very high (α = .94).

Data Analysis Procedure

The data were screened and analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, v25). Changes in PERMA elements were calculated by subtracting PERMA scores reported retrospectively by participants before the pandemic from scores reported at the time of data collection during COVID-19, and a repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted to examine the difference. Point-biserial correlation and Pearson product moment correlation coefficients were calculated to examine the relationships of demographic variables, PsyCap, and coping strategies with change in PERMA scores. Multivariate multiple regression was carried out to understand the predictive role of PsyCap on PERMA at two time points (before and during COVID-19). Structural equation modeling in Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS, v23) software was used to test the mediating role of coping strategies on the relationship between PsyCap and change in PERMA scores. Mediation models were carried out with bootstrapping procedure with a 95% confidence interval.

Results

Prior to exploring the role of PsyCap and coping strategies on change in well-being due to COVID-19, an initial analysis was conducted to understand the characteristics and relationships of constructs in the study. Correlation analyses (see Table 1) revealed significant and positive correlations between four PsyCap HERO dimensions (i.e., hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism; Avey, Avolio et al., 2011) and the six PERMA elements (i.e., positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, accomplishment, and physical health; Butler & Kern, 2016). Further, PsyCap HERO dimensions were negatively correlated to negative emotion and loneliness. Age was positively correlated with change in PERMA elements, but not gender. Similarly, approach coping strategies such as active coping, positive reframing, and acceptance (Carver, 1997) were resilient strategies to handle pandemic stress whereas using emotional support and planning showed weaker but significant roles. Similarly, religion also tended to be an adaptive coping strategy during the pandemic. Behavioral disengagement and self-blame (Carver, 1997) were found to be the dominant avoidant coping strategies that were adopted by students, which led to a significant decrease in well-being during the pandemic. Overall, as seen in Table 1, all three variables studied—PsyCap HERO dimensions, eight PERMA elements, and coping strategies—were highly related.

Table 1

Relationship of Demographic Factors, Psychological Capital, and Coping Strategies With Change in PERMA Elements

| Variables |

Mean |

SD |

P |

E |

R |

M |

A |

N |

H |

L |

| Age |

27.36 |

9.91 |

.15** |

.11** |

.14** |

.16** |

.14** |

.01 |

.03 |

-.17** |

| Course Ф |

– |

– |

.19** |

.10* |

.19** |

.16** |

.06 |

-.05 |

.09* |

-.14** |

| Nature of course Ф |

– |

– |

.06 |

.06 |

.12** |

.13** |

.09* |

.03 |

.03 |

-.10** |

| Gender Ф |

– |

– |

-.01 |

-.06 |

.01 |

-.02 |

-.02 |

.02 |

-.02 |

.03 |

| Employment Ф |

– |

– |

-.17** |

-.11** |

-.13** |

-.19** |

-.10* |

.04 |

-.11** |

.11** |

| Self-Efficacy |

13.80 |

3.21 |

.11** |

.13** |

.14** |

.18** |

.16** |

-.05 |

.15** |

-.03 |

| Hope |

18.68 |

3.92 |

.24** |

.26** |

.20** |

.34** |

.40** |

-.17** |

.21** |

-.10* |

| Resilience |

13.41 |

3.08 |

.23** |

.22** |

.20** |

.32** |

.33** |

-.16** |

.15** |

-.13** |

| Optimism |

8.61 |

2.39 |

.21** |

.27** |

.23** |

.32** |

.30** |

-.11** |

.16** |

-.10* |

| Self-Distraction |

6.32 |

1.41 |

-.09* |

.01 |

.03 |

-.02 |

.01 |

.08* |

.02 |

.11** |

| Active Coping |

5.83 |

2.01 |

.24** |

.28** |

.20** |

.28** |

.32** |

-.09* |

.23** |

-.08* |

| Denial |

2.96 |

1.42 |

-.19** |

-.14** |

-.18** |

-.16** |

-.16** |

.24** |

-.16** |

.12** |

| Substance Use |

3.60 |

2.02 |

-.18** |

-.15** |

-.15** |

-.20** |

-.20** |

.11** |

-.09* |

.17** |

| Using Emotional Support |

5.07 |

1.81 |

.12** |

.11** |

.32** |

.18** |

.11** |

.04 |

.10* |

-.02 |

| Using Instrumental Support |

4.35 |

1.70 |

.01 |

.04 |

.20** |

.07 |

.02 |

.10* |

.04 |

.07 |

| Behavioral Disengagement |

3.96 |

2.11 |

-.43** |

-.37** |

-.40** |

-.46** |

-.44** |

.31** |

-.26** |

.27** |

| Venting |

4.58 |

1.54 |

-.24** |

-.16** |

-.08* |

-.17** |

-.16** |

.29** |

-.09* |

.16** |

| Positive Reframing |

5.12 |

1.78 |

.28** |

.27** |

.21** |

.26** |

.25** |

-.15** |

.18** |

-.14** |

| Planning |

5.42 |

1.75 |

.07 |

.12** |

.11** |

.13** |

.11** |

.08 |

.08* |

-.04 |

| Humor |

4.93 |

2.00 |

-.02 |

-.02 |

-.02 |

-.04 |

-.06 |

-.02 |

.02 |

.05 |

| Acceptance |

6.47 |

1.43 |

.33** |

.27** |

.27** |

.34** |

.31** |

-.25** |

.21** |

-.15** |

| Religion |

3.93 |

2.03 |

.21** |

.16** |

.16** |

.22** |

.13** |

-.08 |

.15** |

-.05 |

| Self-Blame |

4.08 |

1.72 |

-.33** |

-.27** |

-.29** |

-.36** |

-.36** |

.29** |

-.22** |

.20** |

Note. P = Positive Emotion, E = Engagement, R = Relationships, M = Meaning, A = Accomplishment, N = Negative Emotion, H = Physical Health, L = Loneliness.

Ф Point-biserial correlation

* p < .05, ** p < .01

Research Question 1

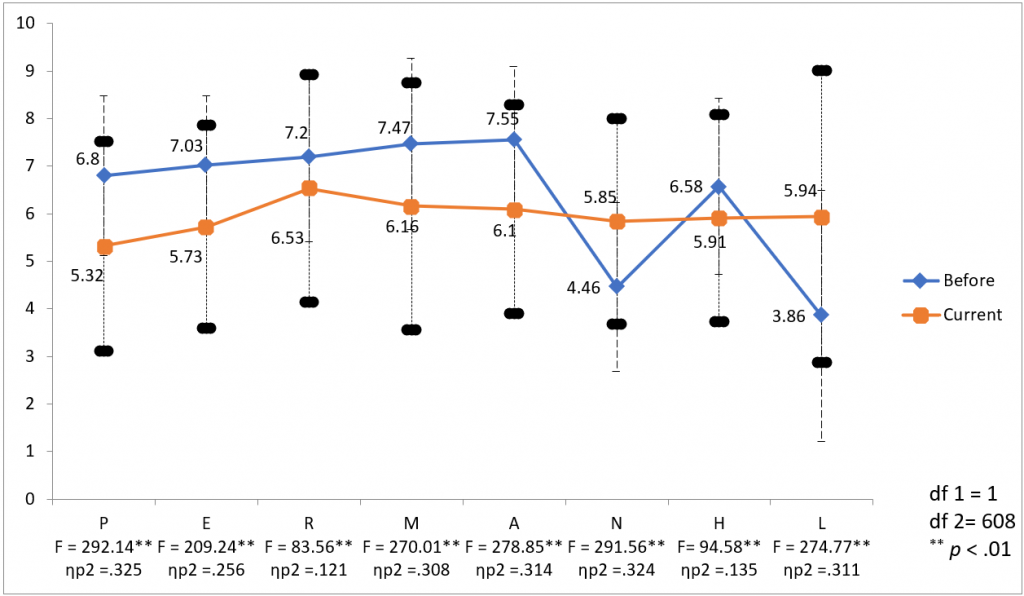

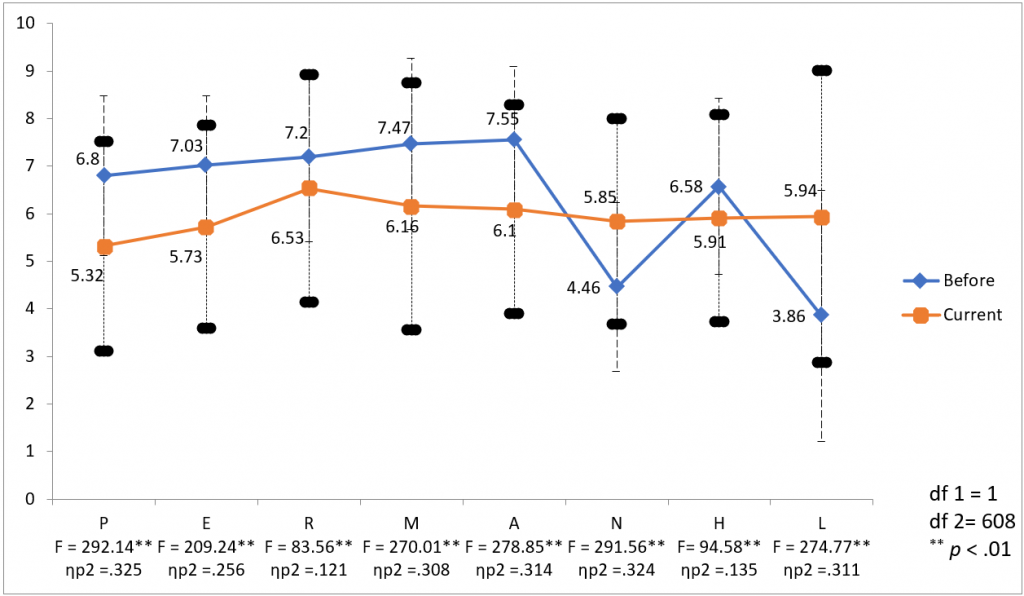

Results of a repeated-measures ANOVA presented in Figure 1 indicate that mean scores of PERMA decreased significantly during COVID-19: λ = .620; F (5,604) = 73.99, p < .001. Partial eta squared was reported as the measure of effect size. The effect size of the change in well-being for PERMA elements was 38%, ηp2 = .380, a high effect size (Cohen, 1988). As expected, negative emotion and loneliness significantly increased during the period of COVID-19, impacting overall well-being in an adverse manner. The average scores of negative emotion and loneliness increased from 4.46 and 3.86 to 5.85 and 5.94, respectively. Physical health significantly reduced from 6.58 to 5.91. The effect size of the change in the scores of individual PERMA elements ranged between 12.1% and 32.5%. Among the PERMA elements, engagement and physical health were least impacted by COVID-19, whereas students’ experiences of positive emotion and negative emotion were the factors that were largely affected.

Figure 1

Changes in the PERMA Prior to the Onset of COVID-19 and After the Onset of COVID-19

Note. P = Positive Emotion, E = Engagement, R = Relationships, M = Meaning, A = Accomplishment, N = Negative Emotion, H = Physical Health, L = Loneliness.

Research Question 2

The predictive role of PsyCap on well-being at two time points (before and after the onset of COVID-19) was analyzed using multivariate multiple regression (see Table 2). Coefficients of determination for models predicting well-being from PsyCap dimensions ranged from 4% to 28%. Before the onset of COVID-19, 23% of the variance in well-being was explained by the PsyCap dimensions (R2 = .23, p < .001), with self-efficacy and optimism as the most significant predictors of well-being. However, during the pandemic, the covariance of the PsyCap dimensions with well-being increased to 39% (R2 = .39, p < .01). Interestingly, after the onset of the pandemic, the predictor role of certain PsyCap dimensions shifted. For example, optimism became the strongest predictor of overall well-being and hope emerged as a predictor of engagement, meaning, accomplishment, and physical health during the pandemic. The predictive role of hope was negligible before COVID-19. The predictive role of resilience on positive emotion, accomplishment, negative emotion, and loneliness also became significant during COVID-19. Self-efficacy was a consistent predictor of PERMA elements before COVID-19. But during COVID-19, the relevance of self-efficacy in predicting PERMA elements was limited to controllable factors—relationships, meaning, and physical health—and the predictive role of self-efficacy overall was no longer significant (see Table 2).

Table 2

Predicting PERMA Elements From Psychological Capital Prior to the Onset of COVID-19 and After the Onset of COVID-19

|

PERMA |

Self-Efficacy |

Hope |

Resilience |

Optimism |

Adj. R2 |

F |

| Before COVID-19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Positive Emotion |

.10* |

-.06 |

-.01 |

.44** |

.19 |

37.66** |

| Engagement |

.10* |

.06 |

.01 |

.11* |

.05 |

8.80** |

| Relationships |

.10* |

.07 |

-.09 |

.29** |

.12 |

21.33** |

| Meaning |

.21** |

.06 |

-.03 |

.38** |

.28 |

58.68** |

| Accomplishment |

.24** |

.06 |

.04 |

.13* |

.14 |

25.62** |

| Negative Emotion |

-.13** |

.10 |

-.05 |

-.29** |

.11 |

18.97** |

| Physical Health |

.16** |

.08 |

-.04 |

.12* |

.07 |

12.16** |

| Loneliness |

-.10* |

0 |

-.01 |

-.19** |

.04 |

7.36** |

| Well-Being |

.19** |

.04 |

-.02 |

.35** |

.23 |

45.41** |

| During COVID-19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Positive Emotion |

.04 |

.09 |

.10* |

.41** |

.30 |

67.05** |

| Engagement |

.02 |

.21** |

.05 |

.26** |

.21 |

40.86** |

| Relationships |

.09* |

.1 |

-.01 |

.33** |

.19 |

36.72** |

| Meaning |

.11** |

.18** |

.09 |

.38** |

.39 |

99.93** |

| Accomplishment |

.05 |

.37** |

.14** |

.17** |

.39 |

96.96** |

| Negative Emotion |

-.03 |

-.07 |

-.13* |

-.23** |

.14 |

26.80** |

| Physical Health |

.16** |

.19** |

-.03 |

.14** |

.15 |

27.25** |

| Loneliness |

-.04 |

.01 |

-.11* |

-.20** |

.08 |

13.34** |

| Well-Being |

.07 |

.22** |

.08 |

.37** |

.39 |

97.48** |

* p < .05, ** p < .01

Research Question 3

Structural equation modeling was used to examine whether coping strategies mediate PsyCap’s effect on well-being. Coping strategies that predicted change in PERMA were used for mediation analysis. Indirect effects describing pathways from PsyCap factors to PERMA factors through identified coping strategies were tested for mediating roles. Results indicated that PsyCap affected well-being both directly and indirectly through coping strategies. Optimism had a significant indirect effect on change in well-being compared to hope and resilience (see Table 3). Among adaptive coping strategies, active coping, positive reframing, and using emotional support mediated the relationship between optimism and overall well-being. Interestingly, using emotional support also showed a similar mediating link between resilience and PERMA, but not for the factors of loneliness and negative emotion. On the other hand, self-blame and behavioral disengagement were two problematic coping strategies that mediated the relationship between optimism and all PERMA elements. Specifically, we found coping through self-blame playing a mediating role between PERMA factors and two of the HERO dimensions—resilience and hope.

Table 3

Indirect Effect of Psychological Capital on PERMA Factors Through Coping Strategies (Mediators)

| PsyCap |

Standardized Beta (ß, Indirect effect) |

| L |

H |

N |

A |

M |

R |

E |

P |

| Active Coping Ф |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Optimism |

-.016* |

.043** |

-.017* |

.06** |

.052** |

.037** |

.052** |

.044** |

|

Resilience |

-.005 |

.014 |

-.006 |

.02 |

.017 |

.012 |

.017 |

.015 |

|

Hope |

-.007 |

.018 |

-.007 |

.025 |

.022 |

.015 |

.022 |

.018 |

|

Self-Efficacy |

-.009 |

.025 |

-.01 |

.034 |

.03 |

.021 |

.03 |

.025 |

| Positive Reframing Ф |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Optimism |

-.047** |

.06** |

-.05** |

.085** |

.088** |

.07** |

.094** |

.096** |

|

Resilience |

-.005 |

.007 |

-.006 |

.01 |

.01 |

.008 |

.011 |

.011 |

|

Hope |

.003 |

-.003 |

.003 |

-.005 |

-.005 |

-.004 |

-.005 |

-.005 |

|

Self-Efficacy |

-.005 |

.006 |

-.005 |

.009 |

.009 |

.007 |

.01 |

.01 |

| Using Emotional Support Ф |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Optimism |

-.007 |

.02* |

.012 |

.03* |

.049** |

.086** |

.029* |

.032** |

|

Resilience |

.003 |

-.012 |

-.005 |

-.013* |

-.021* |

-.037* |

-.012* |

-.014* |

|

Hope |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Self-Efficacy |

-.001 |

.006 |

.002 |

.006 |

.01 |

.018 |

.006 |

.007 |

| Self-Blame Ф |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Optimism |

-.038** |

.043** |

-.056** |

.07** |

.07** |

.056** |

.054** |

.065** |

|

Resilience |

-.03** |

.034** |

-.044** |

.055** |

.055** |

.044** |

.042** |

.051** |

|

Hope |

-.023* |

.025* |

-.033* |

.042* |

.041* |

.033* |

.032* |

.038** |

|

Self-Efficacy |

-.005 |

.006 |

-.007 |

.009 |

.009 |

.007 |

.007 |

.008 |

| Behavioral Disengagement Ф |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Optimism |

-.07** |

.067** |

-.081** |

.113** |

.118** |

.104** |

.097** |

.112** |

|

Resilience |

-.02 |

.02 |

-.023 |

.033 |

.034 |

.03 |

.028 |

.033 |

|

Hope |

-.032 |

.03 |

-.036 |

.051 |

.053 |

.047 |

.044 |

.051 |

|

Self-Efficacy |

-.009 |

.009 |

-.011 |

.015 |

.016 |

.014 |

.013 |

.015 |

Note. Coping strategies with insignificant mediating role are not included in the table. P = Positive Emotion,

E = Engagement, R = Relationships, M = Meaning, A = Accomplishment, N = Negative Emotion, H = Physical Health,

L = Loneliness.

Ф Mediator coping strategies.

* p < .05, ** p < .01

Discussion

The current study investigated the PERMA model of well-being (Seligman, 2011) with university students before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the relationships between PsyCap (F. Luthans et al., 2007), coping strategies, and well-being of university students. We examined whether the COVID-19 context shaped the efficacy of particular strategies to promote well-being. Findings are discussed in three areas: reduction in well-being related to COVID-19, shift in predictive roles of PsyCap HERO dimensions, and coping strategies as a mediator.

Reduction in Well-Being Related to COVID-19

Well-being scores across all PERMA elements, including physical health, were lower than those reported retrospectively prior to the pandemic. Such a decline in well-being following a pandemic is consistent with previous occurrences of public health crises or natural disasters (Deaton, 2012). Participants reported higher levels of negative emotion and loneliness after the onset of COVID-19, and a decrease in positive emotion. It is this balance of positive and negative emotions that contributes to life satisfaction (Diener & Larsen, 1993), and our findings support the notion that fostering particular positive psychological states (PsyCap), as well as engaging in related coping strategies, promotes well-being in the context of this large-scale crisis.

Shift in Predictive Roles of PsyCap HERO Dimensions

Consistent with prior research (Avey, Reichard et al., 2011; F. Luthans & Youssef-Morgan, 2017; Youssef-Morgan & Luthans, 2015), we found that PsyCap predicted well-being. PsyCap’s positive psychological resources (HERO dimensions) may enable students to have a “positive appraisal of circumstances” (F. Luthans et al., 2007, p. 550) by providing mechanisms for reframing and reinterpreting potentially negative or neutral situations. There was however an interesting shift in the predictive role of PsyCap dimensions before and after the onset of COVID-19. Prior to COVID-19, self-efficacy and optimism were the two major psychological resources that predicted university student well-being. However, after COVID-19, self-efficacy did not present as a predictor of well-being in this study. Although the reason for this result is uncertain, it is conceivable that attending to an uncertain future (i.e., hope) and recovering from immediate losses (i.e., resilience) became more salient, and one’s self-efficacy in managing normal, everyday challenges receded in importance. Indeed, optimism and hope each uniquely predict a major proportion of variance of the change in well-being and may together help students to face an uncertain future (M. W. Gallagher & Lopez, 2009). Resilience, the ability to recover from setbacks when pathways are blocked (Masten, 2001), had a predictive role on positive emotion and accomplishment in this study.

Coping Strategies as a Mediator

While PsyCap directly relates to well-being and coping strategies relate to well-being, our findings indicated that coping strategies also played a significant mediating role in the relationship between PsyCap and well-being. Specifically, adaptive coping strategies played a significant role in enhancing the positive effects of PsyCap on well-being. Adaptive coping strategies—such as active coping, acceptance, using emotional support, and positive reframing—were found to better aid in predicting well-being. In this study, accepting the realities, using alternative affirmative explanations, seeking social support for meeting emotional needs, and engaging in active problem-focused coping behaviors seem to be the most helpful ways to counter the negative effects of the pandemic on well-being. Conversely, when individuals employed problematic coping strategies such as behavioral disengagement and self-blame (Carver, 1997), the negative impacts were much stronger than the positive effect of adaptive coping strategies.

Implications for Counselors

Given findings of the relationship between PsyCap and well-being in the current study, as well as in prior research (F. Luthans et al., 2006; F. Luthans et al., 2015; McGonigal, 2015), counselors may wish to focus on developing PsyCap to help university students flourish both during the pandemic and in a post-pandemic world. Two significant challenges to counseling professionals on college campuses are the lack of resources to adequately respond to mental health concerns among students and the stigma associated with accessing services (R. P. Gallagher, 2014; Michaels et al., 2015). Thus, efficient interventions that are not likely to trigger stigma responses are helpful in this context. Several researchers have found that relatively short training in PsyCap interventions, including web-based platforms (Dello Russo & Stoykova, 2015; Demerouti et al., 2011; Ertosun et al., 2015; B. C. Luthans et al., 2012, 2013) have been effective. Recently, the use of positive psychology smartphone apps such as Happify and resilience-building video games such as SuperBetter have been suggested and tested as motivational tools, especially with younger adults, to foster sustained and continued engagement with PsyCap development (F. Luthans & Youssef-Morgan, 2017; McGonigal, 2015). These are potential areas of practice for college counselors and counselors serving university students.

Interventions that are described as well-being approaches rather than those that highlight pathologies are less stigmatizing (Hunt & Eisenberg, 2010; Umucu et al., 2020) than traditional deficit-based therapeutic approaches. There are a number of research-based approaches offered in the field of positive psychology to guide mental health professionals to facilitate development of PsyCap and other important well-being correlates. These include approaches to building positive emotions (Fredrickson, 2009); coping strategies, which were found in this study to boost well-being (Jardin et al., 2018; Lyubomirsky, 2008); and effective goal pursuits (F. Luthans & Youssef-Morgan, 2017). One of the distinguishing characteristics of PsyCap is its malleability and openness to change and development (Avey, Reichard et al., 2011; F. Luthans et al., 2006). Thus, there is potential for counselors to develop well-being promotion initiatives for students on university campuses targeting PsyCap and its constituting positive psychological HERO resources with the end goal of strengthening well-being (Avey, Avolio et al., 2011; F. Luthans et al., 2015; F. Luthans & Youssef-Morgan, 2017).

Strategies and programming to develop wellness can be delivered in one-on-one sessions with students, as well as in group settings, and may have either a prevention or intervention focus. They could also be adapted to provide services online. A variety of free online assessments are also available for use by counselors, including tools that measure well-being, positive psychological resources, and character strengths of university students in addition to existing assessment batteries. By administering the PERMA-Profiler to university students, counselors could identify and understand what dimension of well-being should be further developed (Umucu et al., 2020). With each PERMA element individually rendering to flourishing mental health, specific targeted positive psychology interventions might be offered as domain-specific interventions.

Counselors could help university students benefit from attending to, appreciating, and attaining life’s positives (Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009) and from enhancing the strength and frequency of employing positive coping strategies through targeted psychoeducational or counseling interventions. Teaching university students active coping strategies, such as positive reframing and how to access emotional support, could help them cope with adverse situations. Sheldon and Lyubomirsky (2006) indicated that practicing gratitude helps people to cope with negative situations because it enables them to view such situations through a more positive lens. Among university students, healthy coping strategies could buffer them from some of the unique challenges associated with acculturating and adjusting to college experiences (Jardin et al., 2018), especially during a pandemic.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

The findings of this study should be considered in light of certain limitations. Foremost among these is that data were collected using self-report measures, and in the case of the PERMA-Profiler, data were collected using the retrospective recall of participants as they considered their well-being prior to the onset of COVID-19. Retrospective recall may be inaccurate (Gilbert, 2007) with participants under- or overestimating their well-being. Given the ongoing repercussions of the pandemic, we recommend continued and longitudinal studies on well-being, coping strategies, and PsyCap. Additionally, data collection methods and sample demographics would likely limit generalizability. We utilized a correlational cross-sectional study design; therefore, although PsyCap was predictive of change in well-being before and during COVID-19, neither causation nor directionality can be assumed. In future, researchers may wish to investigate whether PsyCap predicts longitudinal changes in well-being in the COVID-19 context.

A further consideration is that the PERMA model of well-being (Seligman, 2011) may not be associated with similar outcomes for people of other cultures and backgrounds during COVID-19. Future researchers examining well-being in university students in different regions of the country or internationally may wish to further investigate the applicability of the PERMA model as a measure of university students’ well-being during the pandemic. Finally, the moderate Cronbach’s alpha reliability scores of < .70 (Field, 2013) for the subscales of the Brief COPE inventory and the engagement subscale of the PERMA-Profiler are of concern, which has also been expressed by prior researchers (Goodman et al., 2018; Iasiello et al., 2017). Future researchers should consider issues of internal consistency as they choose scales and interpret results.

Conclusion

To conclude, the present findings contribute to existing literature on PsyCap and well-being, using the PERMA model of well-being (Seligman, 2011) among university students in the United States in the context of COVID-19. Key findings are that the optimism, hope, and resilience dimensions of PsyCap are significant predictors of well-being, explaining a large amount of variance, with adaptive coping being conducive to flourishing. Further, the present findings highlight the importance of examining the relationships between each element of well-being and with each HERO dimension. Both individual counseling and group-based programming focused on PsyCap and positive coping strategies could support the well-being of university students as they experience ongoing stressors related to the pandemic or as they face other setbacks.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Avey, J. B., Avolio, B. J., & Luthans, F. (2011). Experimentally analyzing the impact of leader positivity on follower positivity and performance. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(2), 282–294.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.02.004

Avey, J. B., Reichard, R. J., Luthans, F., & Mhatre, K. H. (2011). Meta-analysis of the impact of positive psychological capital on employee attitudes, behaviors, and performance. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 22(2), 127–152. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.20070

Billings, A. G., & Moos, R. H. (1984). Coping, stress, and social resources among adults with unipolar depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(4), 877–891. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.46.4.877

Butler, J., & Kern, M. L. (2016). The PERMA-Profiler: A brief multidimensional measure of flourishing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 6(3), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v6i3.526

Carmona-Halty, M., Schaufeli, W. B., & Salanova, M. (2019). Good relationships, good performance: The mediating role of psychological capital: A three-wave study among students. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 306. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00306

Carver, C. S. (1997). You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the Brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4(1), 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6

Carver, C. S., & Connor-Smith, J. (2010). Personality and coping. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 679–704.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100352

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(2), 267–283. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.267

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge Academic.

de la Fuente, J., Lahortiga-Ramos, F., Laspra-Solis, C., Maestro-Martin, C., Alustiza, I., Auba, E., & Martin-Lanas, R. (2020). A structural equation model of achievement emotions, coping strategies and engagement-burnout in undergraduate students: A possible underlying mechanism in facets of perfectionism. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17062106

Deaton, A. (2012). The financial crisis and the well-being of Americans: 2011 OEP Hicks lecture. Oxford Economic Papers, 64(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/gpr051

Dello Russo, S., & Stoykova, P. (2015). Psychological capital intervention (PCI): A replication and extension. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 26(3), 329–347. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.21212

Demerouti, E., van Eeuwijk, E., Snelder, M., & Wild, U. (2011). Assessing the effects of a “personal effectiveness” training on psychological capital, assertiveness and self-awareness using self-other agreement. The Career Development International, 16(1), 60–81. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620431111107810

DeWitz, S. J., Woolsey, M. L., & Walsh, W. B. (2009). College student retention: An exploration of the relationship between self-efficacy beliefs and purpose in life among university students. Journal of College Student Development, 50(1), 19–34. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.0.0049

Diener, E., & Larsen, R. J. (1993). The experience of emotional wellbeing. In M. Lewis & J. M. Haviland (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (pp. 405–415). Guilford.

Ertosun, Ö. G., Erdil, O., Deniz, N., & Alpkan, L. (2015). Positive psychological capital development: A field study by the Solomon four group design. International Business Research, 8(10), 102–111.

https://doi.org/10.5539/ibr.v8n10p102

Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. SAGE.

Finkelstein-Fox, L., & Park, C. L. (2019). Control-coping goodness-of-fit and chronic illness: A systematic review of the literature. Health Psychology Review, 13(2), 137–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2018.1560229

Flatt, A. K. (2013). A suffering generation: Six factors contributing to the mental health crisis in North American higher education. College Quarterly, 16(1).

Fredrickson, B. L. (2009). Positivity: Groundbreaking research reveals how to embrace the hidden strength of positive emotions, overcome negativity, and thrive. Crown.

Gallagher, M. W., & Lopez, S. J. (2009). Positive expectancies and mental health: Identifying the unique contributions of hope and optimism. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(6), 548–556.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760903157166

Gallagher, R. P. (2014). National Survey of College Counseling Centers 2014. International Association of Counseling Services, Inc. http://d-scholarship.pitt.edu/28178

Gilbert, D. (2007). Stumbling on happiness. Random House.

Goodman, F. R., Disabato, D. J., Kashdan, T. B., & Kauffman, S. B. (2018). Measuring well-being: A comparison of subjective well-being and PERMA. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 13(4), 321–332.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2017.1388434

Hazan Liran, B., & Miller, P. (2019). The role of psychological capital in academic adjustment among university students. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 20(1), 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9933-3

Hoover, E. (2020). Distanced learning. Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/distanced-learning

Huckins, J. F., DaSilva, A. W., Wang, W., Hedlund, E., Rogers, C., Nepal, S. K., Wu, J., Obuchi, M., Murphy, E. I.,

Meyer, M. L., Wagner, D. D., Holtzheimer, P. E., & Campbell, A. T. (2020). Mental health and behavior of college students during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic: Longitudinal smartphone and ecological momentary assessment study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(6), e20185.

https://doi.org/10.2196/20185

Hunt, J., & Eisenberg, D. (2010). Mental health problems and help-seeking behavior among college students. Journal of Adolescent Health, 46(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.08.008

Iasiello, M., Bartholomaeus, J., Jarden, A., & Kelly, G. (2017). Measuring PERMA+ in South Australia, the State of Wellbeing: A comparison with national and international norms. Journal of Positive Psychology and Wellbeing, 1(2), 53–72.

Jardin, C., Mayorga, N. A., Bakhshaie, J., Garey, L., Viana, A. G., Sharp, C., Cardoso, J. B., & Zvolensky, M. J.

(2018). Clarifying the relation of acculturative stress and anxiety/depressive symptoms: The role of anxiety sensitivity among Hispanic college students. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 24(2), 221–230. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000175

Johnson, R. (2020). Students stressed out due to coronavirus, new survey finds. Best Colleges (April 20, 2020).

https://www.bestcolleges.com/blog/coronavirus-survey

Joseph, S., & Linley, P. A. (Eds.). (2008). Trauma, recovery, and growth: Positive psychological perspectives on posttraumatic stress. Wiley.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090197

Klussman, K., Nichols, A. L., Langer, J., & Curtin, N. (2020). Connection and disconnection as predictors of mental health and wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 10(2). https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v10i2.855

Lipson, S. K., Lattie, E. G., & Eisenberg, D. (2019). Increased rates of mental health service utilization by U.S. college students: 10-year population-level trends (2007–2017). Psychiatric Services, 70(1), 60–63.

https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201800332

Luthans, B. C., Luthans, K. W., & Avey, J. B. (2013). Building the leaders of tomorrow: The development of academic psychological capital. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 21(2), 191–199.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051813517003

Luthans, B. C., Luthans, K. W., & Jensen, S. M. (2012). The impact of business school students’ psychological capital on academic performance. The Journal of Education for Business, 87(5), 253–259.

https://doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2011.609844

Luthans, F., Avey, J. B., Avolio, B. J., Norman, S. M., & Combs, G. M. (2006). Psychological capital development: Toward a micro-intervention. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(3), 387–393.

https://doi.org/10.1002/job.373

Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2007). Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 60(3), 541–572.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00083.x

Luthans, F., & Youssef-Morgan, C. M. (2017). Psychological capital: An evidence-based positive approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4, 339–366.

Luthans, F., Youssef-Morgan, C. M., & Avolio, B. J. (2015). Psychological capital and beyond. Oxford University Press.

Luthans, K. W., Luthans, B. C., & Palmer, N. F. (2016). A positive approach to management education: The relationship between academic PsyCap and student engagement. Journal of Management Development, 35(9), 1098–1118. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-06-2015-0091

Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). The how of happiness: A scientific approach to getting the life you want. Penguin.

Madhyastha, S., Latha, K. S., & Kamath, A. (2014). Stress, coping and gender differences in third year medical students. Journal of Health Management, 16(2), 315–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972063414526124

Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56(3), 227–238. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.227

McGonigal, J. (2015). SuperBetter: A revolutionary approach to getting stronger, happier, braver and more resilient. Penguin Press.

Michaels, P. J., Corrigan, P. W., Kanodia, N., Buchholz, B., & Abelson, S. (2015). Mental health priorities: Stigma elimination and community advocacy in college settings. Journal of College Student Development, 56(8), 872–875. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2015.0088

Miyazaki, Y., Bodenhorn, N., Zalaquett, C., & Ng, K.-M. (2008). Factorial structure of Brief COPE for international students attending U.S. colleges. College Student Journal, 42(3), 795-806.

Newman, A., Ucbasaran, D., Zhu, F., & Hirst, G. (2014). Psychological capital: A review and synthesis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(S1), S120–S138. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1916

Primack, B. A., Shensa, A., Escobar-Viera, C. G., Barrett, E. L., Sidani, J. E, Colditz, J. B., & Everette James, A. (2017). Use of multiple social media platforms and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A nationally-representative study among U.S. young adults. Computer Human Behavior, 69, 1–9.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.013

Rabenu, E., Yaniv, E., & Elizur, D. (2017). The relationship between psychological capital, coping with stress, well-being, and performance. Current Psychology, 36(4), 875–887. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-016-9477-4

Ray, J. (2019). Americans’ stress, worry and anger intensified in 2018. Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/249098/americans-stress-worry-anger-intensified-2018.aspx

Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. Simon & Schuster.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Simon & Schuster.

Selvaraj, P. R., & Bhat, C. S. (2018). Predicting the mental health of college students with psychological capital. Journal of Mental Health, 27(3), 279–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2018.1469738

Sheldon, K. M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2006). How to increase and sustain positive emotion: The effects of expressing gratitude and visualizing best possible selves. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1(2), 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760500510676

Sin, N. L., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2009). Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: A practice-friendly meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(5), 467–487. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20593

Tansey, T. N., Smedema, S., Umucu, E., Iwanaga, K., Wu, J.-R., Cardoso, E. D. S., & Strauser, D. (2018). Assessing college life adjustment of students with disabilities: Application of the PERMA framework. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 61(3), 131–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034355217702136

Twenge, J. M. (2017). iGen: Why today’s super-connected kids are growing up less rebellious, more tolerant, less happy—and completely unprepared for adulthood—and what that means for the rest of us. Atria Books.

Umucu, E., Wu, J.-R., Sanchez, J., Brooks, J. M., Chiu, C.-Y., Tu, W.-M., & Chan, F. (2020). Psychometric validation of the PERMA-profiler as a well-being measure for student veterans. Journal of American College Health, 68(3), 271–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2018.1546182

Wan, W. (2020). The coronavirus pandemic is pushing America into a mental health crisis. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2020/05/04/mental-health-coronavirus

Witters, D., & Harter, J. (2020). Worry and stress fuel record drop in U.S. life satisfaction. Gallup.

https://news.gallup.com/poll/310250/worry-stress-fuel-record-drop-life-satisfaction.aspx

Youssef-Morgan, C. M., & Luthans, F. (2015). Psychological capital and well-being. Stress Health, 31(3), 180–188. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2623

Priscilla Rose Prasath, PhD, MBA, LPC (TX), is an assistant professor at the University of Texas at San Antonio. Peter C. Mather, PhD, is a professor and department chair at Ohio University. Christine Suniti Bhat, PhD, LPC, LSC (OH), is a professor and the interim director of the George E. Hill Center for Counseling & Research at Ohio University. Justine K. James, PhD, is an assistant professor at University College in Kerala, India. Correspondence may be addressed to Priscilla Rose Prasath, 501 W. Cesar E. Chavez Boulevard, Durango Building, University of Texas at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78207, priscilla.prasath@utsa.edu.

Feb 26, 2021 | Volume 11 - Issue 1

Christian D. Chan, Stacey Diane Arañez Litam

The emergence and global spread of COVID-19 precipitated a massive public health crisis combined with multiple incidents of racial discrimination and violence toward Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) communities. Although East Asian communities are more frequently targeted for instances of pandemic-related racial discrimination, multiple disparities converge upon Filipino communities that affect their access to mental health care in light of COVID-19. This article empowers professional counselors to support the Filipino community by addressing three main areas: (a) describing how COVID-19 contributes to racial microaggressions and institutional racism toward Filipino communities; (b) underscoring how COVID-19 exacerbates exposure to stressors and disparities that influence help-seeking behaviors and utilization of counseling among Filipinos; and (c) outlining how professional counselors can promote racial socialization, outreach, and mental health equity with Filipino communities to mitigate the effects of COVID-19.

Keywords: Asian American, Filipino, mental health equity, COVID-19, discrimination

Asian Americans represent the fastest-growing ethnic group in the United States (Budiman et al., 2019). Following the global outbreak of COVID-19, many Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPIs) have experienced a substantial increase in race-based hate incidents. These incidents of racial discrimination have included verbal harassment, physical attacks, and discrimination against Asian-owned businesses (Jeung & Nham, 2020), which multiply the harmful effects on psychological well-being and life satisfaction among AAPIs (Litam & Oh, 2020). According to Pew Research Center trends (Ruiz et al., 2020), about three in 10 Asian adults reported they experienced racial discrimination since the outbreak began. Proliferation of anti-Chinese and xenophobic hate speech from political leaders, news outlets, and social media, which touted COVID-19 as the “Chinese virus,” further exacerbate instances of race-based discrimination (U.S. Department of Justice, 2020) and echo the Yellow Peril discourse from the late 19th century (Litam, 2020; Poon, 2020).

Although the community is often aggregated, Asian Americans are not a monolithic entity (Choi et al., 2017; Jones-Smith, 2019; Sue et al., 2019). The term Asian American encompasses over 40 distinct subgroups, each with distinct languages, cultures, beliefs, and migration histories (Pew Research Center, 2013; Sue et al., 2019). It is no surprise, therefore, that specific ethnic subgroups would be more affected by the pandemic than others. For example, instances of COVID-19–related racial discrimination disproportionately affect East Asian communities, specifically Chinese migrants and Chinese Americans. An analysis of nearly 1,500 reports of anti-Asian hate incidents indicated approximately 40% of Chinese individuals reported experiences of discrimination as compared to 16% of Korean individuals and 5.5% of Filipinos (Jeung & Nham, 2020). Although Chinese individuals disproportionately experience overt forms of COVID-19–related discrimination, Filipino migrants and Filipino Americans are not immune to the deleterious effects of the pandemic.

With over 4 million people of Filipino descent residing in the United States (Asian Journal Press, 2018), it is of paramount importance for professional counselors to recognize how the Filipino American experience may compound with additional COVID-19 exposure and related stressors in unique ways that distinctively impact their experiences of stress and mental health. The current article identifies how the racialized climate of COVID-19 influences Filipino-specific microaggressions and the presence of systemic and institutional racism toward Filipino communities. The ways in which COVID-19 exacerbates existing racial disparities across social determinants of health, help-seeking behaviors, and utilization of counseling services are described. Finally, the implications for counseling practice and advocacy are presented in ways that can embolden professional counselors to promote racial socialization, outreach, and health equity with Filipino communities to mitigate the effects of COVID-19.

Health Disparities Among Filipino Americans

The unprecedented emergence of COVID-19 has affected the global community. As of January 5, 2021, a total of 21,382,296 cases were confirmed and 362,972 deaths had been reported in the United States (Worldometer, n.d.). Although information about how racial and ethnic groups are affected by the pandemic is forthcoming, emerging data suggests that specific groups are disproportionately affected. Professional counselors must be prepared to support communities that may be more vulnerable to pandemic-related stress and face challenges related to medical and mental health care access because of intersecting marginalized identities, such as age, race, ethnicity, gender identity, sexual identity, social class, and migration history (Chan & Henesy, 2018; Chan et al., 2019; Litam & Hipolito-Delgado, 2021). For example, the AAPI population may be especially in need of mental health support because of ongoing xenophobic sentiments from political leaders that combine with intergenerational trauma, racial discrimination, and racial trauma (Litam, 2020).

Underutilization of Mental Health Services

Compared to other Asian American subgroups, Filipinos are the least likely to seek professional mental health services. In a study of 2,230 Filipinos, approximately 73% had never used any type of mental health service and only 17% sought help from friends, community members, peers, and religious or spiritual leaders (Gong et al., 2003). Since the Gong et al. (2003) study, a multitude of researchers have documented the persistent disparity of mental health usage and unfavorable attitudes toward professional help-seeking among Filipinos (David & Nadal, 2013; David et al., 2019; Nadal, 2021; Tuazon et al., 2019), despite high rates of psychological distress (Martinez et al., 2020).

The experiences of Filipino communities uniquely influence aspects of mental health and wellness. Compared to other subgroups of Asian Americans, Filipino Americans with post-traumatic stress experiences tend to exhibit poorer health (Kim et al., 2012; Klest et al., 2013), and report higher rates of racial discrimination (Li, 2014). As a subgroup, Filipino Americans present to mental health counseling settings with high rates of depression, suicide, HIV, unintended pregnancy, eating disorders, and drug use (David et al., 2017; Klest et al., 2013; Nadal, 2000, 2021). Compared to other Asian subgroups, Filipinos may experience lower social class and employment statuses, which may increase the prevalence of mental health issues (Araneta, 1993). Among Filipinos, intergenerational cultural conflicts and experiences of racial discrimination were identified as significant contributors to depression and suicidal ideation (Choi et al., 2020). The underutilization of professional mental health services and help-seeking among Filipino communities is unusual because of their familiarity with Western notions, systems, and institutions, which surface as traits that are typically associated with mental health help-seeking within the broader AAPI community (Abe-Kim et al., 2002, 2004; Shea & Yeh, 2008).

Distinct Experiences of Oppression

Aspects of Filipino history are characterized by colonization, oppression, and intergenerational racial trauma (David & Nadal, 2013) and have been rewritten by White voices in ways that communicate how America saved the Philippines from Spanish rule through colonization (Ocampo, 2016). These sentiments remain deeply entrenched within the mindset of many Filipinos in the form of colonial mentality (David & Nadal, 2013; Tuazon et al., 2019). Colonial mentality refers to the socialized and oppressive mindset characterized by beliefs about the superiority of American values and denigration of Filipino culture and self (David & Okazaki, 2006a, 2006b). Colonial mentality is the insidious aftermath galvanized through years of intergenerational trauma, U.S. occupation, and socialization under White supremacy (David et al., 2017). Professional counselors must recognize the interplay between colonial mentality and the mental health and well-being of Filipino clients to best support this unique population.

The internalized experiences of oppression perpetuate the denigration of Filipinos by Filipinos as a result of the internalized anti-Black sentiments and notions of White supremacy that remain at the forefront of American history (Ocampo, 2016). The Filipino experience is one that is characterized by forms of discrimination by individuals who reside both within and outside of the Filipino community (Nadal, 2021). For example, Filipinos who espouse a colonial mentality disparage those with Indigenous Filipino traits (i.e., dark skin and textured hair) as unattractive, undesirable, and worthy of shame (Angan, 2013; David, 2020; Mendoza, 2014). Filipinos also experience a sense of otherness within the AAPI community and from other communities of color because their history, culture, and phenotype combine in ways that “break the rules of race” (Ocampo, 2016, p. 13). Although Filipinos are sometimes confused with individuals from Chinese communities, they are not typically perceived as Asian or East Asian (Lee, 2020) and are often mistaken for Black or Latinx (Ocampo, 2016; Sanchez & Gaw, 2007). These pervasive experiences render the Filipino identity invisible (Nadal, 2021). Ultimately, Filipinos remain among the most mislabeled and culturally marginalized of Asian Americans (Sanchez & Gaw, 2007). Professional counselors who work with Filipino clients must obtain a deeper understanding of how these unique experiences of invisibility and colonial mentality continue to affect the minds and the worldviews of Filipinos and Filipino Americans.

Risk Factors for COVID-19 Exposure

The burgeoning rate of COVID-19 cases has devastated hospitals and medical settings. The overwhelming strain faced by medical communities uniquely affects Filipino migrants and Filipino Americans who are overrepresented in health care and disproportionately at risk of COVID-19 exposure (National Nurses United, 2020). The overrepresentation of Filipinos in health care, particularly within the nursing profession, is directly tied to the history of U.S. colonization. Following the U.S. occupation of the Philippines from 1899 to 1946, the Filipino zeitgeist became imbued with profound cultural notions of American superiority and affinity for Westernized attitudes, behaviors, and values (David et al., 2017). For example, the introduction of the American nursing curricula by U.S. Army personnel during the Spanish-American war (McFarling, 2020) instilled pervasive cultural influences that positioned the nursing profession as a viable strategy to escape political and economic instability in pursuit of a better life in the United States (Choy, 2003). These cultural notions have culminated to make the Philippines the leading exporter of nurses in the world (Choy, 2003; Espiritu, 2016). Of the immigrant health care workers across the United States, an estimated 28% of registered nurses, 4% of physicians and surgeons, and 12% of home health aides are Filipinos (Batalova, 2020). About 150,000 registered nurses in the United States are Filipino, equating to about 4% of the overall nursing population (McFarling, 2020; National Nurses United, 2020). According to the National Nurses United (2020) report, 31.5% of deaths among registered nurses and 54% of deaths among registered nurses of color were Filipinos. Based on these statistics, Filipinos face disproportionate exposure to pandemic-related stressors and death that may increase the risk for mental health issues.

Individuals of Filipino descent may also face significant COVID-19–related challenges, as they are predisposed to several health conditions that have been linked with poorer treatment prognosis and outcomes (Ghimire et al., 2018; Maxwell et al., 2012). Compared to other racial and ethnic subgroups, Filipinos residing in California had higher rates of type II diabetes, asthma, and cardiovascular disease (Adia et al., 2020). High rates of hypertension, cholesterol, and diabetes were also noted in studies of Filipino Americans residing in the greater Philadelphia region (Bhimla et al., 2017) and in Las Vegas, Nevada (Ghimire et al., 2018). One study of Filipinos residing in the New York metropolitan area indicated rates of obesity significantly increased the longer Filipino immigrants resided in the United States (Afable et al., 2016). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021) associated each of these underlying medical conditions with a greater likelihood for hospitalization, intensive care, use of a ventilator, and increased mortality. Filipino Americans also tend to report lower social class and employment statuses as compared to other Asian Americans, which may contribute to higher rates of mental health issues and create barriers to health care access (Adia et al., 2020; Sue et al., 2019).

Cultural Barriers to Professional Mental Health Services

Filipinos face culturally rooted barriers to seeking professional mental health services that may include fears related to reputation, endorsement of fatalistic attitudes, religiousness, communication barriers, and lack of culturally competent services (Gong et al., 2003; Nadal, 2021; Pacquiao, 2004). The presence of mental illness stigma is also deeply entrenched within Filipino communities (Appel et al., 2011; Augsberger et al., 2015; Tuazon et al., 2019). In many traditional Filipino families, mental illness is mitigated by addressing personal and emotional problems with family and close friends, and through faith in God (David & Nadal, 2013). Rejection of mental illness is based on the belief that individuals who receive counseling or therapy are crazy, dangerous, and unpredictable (de Torres, 2002; Nadal, 2021).

Connection and Kinship

Given the central prominence of family, it is no surprise that Filipino individuals’ mental health begins to suffer when their connection to community and kinship is compromised. Although relatively few studies on Filipino mental health exist, Filipinos and Filipino Americans consistently report family-related issues as among the most stressful. In one study of Filipino and Korean families in the Midwest (N = 1,574), the presence of intergenerational family conflict significantly contributed to an increase in depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation (Choi et al., 2020). In another study of Filipino Americans, quality time with family, friends, and community was identified as an important factor in mitigating the effects of depression (Edman & Johnson, 1999). The centralized role of Filipino families uniquely combines with a group mentality in ways that may additionally hinder rates of professional help-seeking.

Hiya and Amor Propio

Notions of hiya and amor propio each represent culturally specific barriers to seeking mental health care. According to Gong and colleagues (2003), hiya and amor propio are related to the East Asian notions of saving face. While hiya emphasizes the more extensive experience of shame that arises from fear of losing face, amor propio is associated with concepts of self-esteem linked to the desire to maintain social acceptance. A loss of amor propio would result in a loss of face and may compromise the cherished position of community acceptance (Gong et al., 2003). Filipino Americans may thus avoid seeking professional mental health services because of combined feelings of shame (hiya) linked to beliefs that one has failed or is unable to overcome their problems independently, and fears of losing social positioning within one’s community (amor propio). To experience amor propio would put a Filipino—or worse, their family—at risk for tsismis, or gossip. Indeed, avoiding behaviors that may lead others within the Filipino community to engage in tsismis about the client or their family is a significant factor that guides choices and behaviors. Engaging in behaviors that result in one’s family becoming the focus of tsismis is considered highly shameful and reprehensible among Filipino communities.

Bahala Na

The Tagalog term bahala na refers to the sense of optimistic fatalism that characterizes the shared experiences of many Filipinos and Filipino Americans. Bahala na can be evidenced through Filipino cultural expectations to endure emotional problems and avoid discussion of personal issues. This core attitude may have deleterious effects on mental health and help-seeking, as many Filipinos are socialized to deny or minimize stressful experiences or to simply endure emotional problems (Araneta, 1993; Sanchez & Gaw, 2007). A qualitative analysis of 33 interviews and 18 focus groups of Filipino Americans indicated bahala na may combine with religious beliefs to create additional barriers to addressing mental health problems (Javier et al., 2014). For example, virtuous and religious Filipinos and Filipino Americans may endorse bahala na attitudes by believing their higher power has instilled purposeful challenges that can be overcome by sufficient faith and endurance (Javier et al., 2014).

Hindi Ibang Tao

Moreover, many Filipinos and Filipino Americans demonstrate hesitance to trust individuals who are considered outsiders. When interactions with those considered other cannot be avoided, traditional Filipinos tend to be reticent, conceal their real emotions, and avoid disclosure of personal thoughts, needs, and beliefs (Pasco et al., 2004). Filipino community members place a large value on in-group versus out-group members and largely prefer to seek support from helping professionals within the Filipino community, rather than from others outside of the group (Gong et al., 2003). Individuals who are hindi ibang tao (in Tagalog, “one of us”) are differentiated from those who are ibang tao (in Tagalog, “not one of us”), which influences interactions and amount of trust given to health care providers (Sanchez & Gaw, 2007). White counselors may be able to bridge the cultural gap with Filipino clients to become hindi ibang tao by exhibiting respect, approachability, and a willingness to consider the specific influences of Filipino history and the importance of family (Sanchez & Gaw, 2007). Professional counselors who overlook, minimize, or disregard these cultural values risk higher rates of early termination and may experience their Filipino clients as exhibiting little emotion (Nadal, 2021). Filipino clients who are not yet comfortable with professional counselors may interact in a polite, yet superficial manner because culturally responsive relationships and trust have not been developed (Gong et al., 2003; Pasco et al., 2004; Tuazon et al., 2019).

Pakikisama and Kapwa

Another Filipino cultural barrier is pakikisama, or the notion that when one belongs to a group, one should be wholly dedicated to pleasing the group (Bautista, 1999; Nadal, 2021). Filipino core values extend beyond the general notion of collectivism and include kapwa, an Indigenous worldview in which the self is not distinguished from others (David et al., 2017; Enriquez, 2010). Thus, Filipinos do not solely act in ways that benefit the group; they are also expected to make decisions that please other group members, even at the expense of their own desires, needs, or mental health (Nadal, 2021). The cultural notions of pakikisama and kapwa interplay with amor propio in ways that have detrimental effects on Filipinos in dire need of mental health support. For example, a second-generation Filipino American may recognize that their suicidal thoughts and experiences of depression may be worthy of mental health support, but recognition of cultural mistrust toward those deemed other may risk their family’s social acceptance (amor propio). Risking the family’s social acceptance could ultimately violate group wishes (pakikisama) and may subject their family to stigma and gossip (tsismis).

Implications for Practice and Advocacy in Professional Counseling