Dec 16, 2020 | Volume 10 - Issue 4

Thomas A. Field, William H. Snow, J. Scott Hinkle

The hiring of new faculty members in counselor education programs can be complicated by the available pool of qualified graduates with doctoral degrees in counselor education and supervision, as required by the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) for core faculty status. A pipeline problem for faculty hiring may exist in regions with fewer doctoral programs. In this study, the researchers examined whether the number of doctoral programs accredited by CACREP is regionally imbalanced. The researchers used an ex post facto study to analyze differences in the number of doctoral programs among the five regions commonly defined by national counselor education associations and organizations. A large and significant difference was found in the number of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs by region, even when population size was statistically controlled. The Western region had by far the fewest number of doctoral programs. The number of CACREP-accredited master’s programs in a state was a large and significant predictor for the number of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs in a state. State population size, state population density, the number of universities per state, and the number of American Psychological Association–accredited counseling psychology programs were not predictors. Demand may surpass supply of doctoral counselor educators in certain regions, resulting in difficulties with hiring new faculty for some CACREP-accredited programs. An analysis of programs currently in the process of applying for CACREP accreditation suggests that this pipeline problem looks likely to continue or even worsen in the near future. Implications for counselor education and supervision are discussed.

Keywords: doctoral programs, master’s programs, counselor education and supervision, CACREP, pipeline problem

Counselor education has experienced substantial growth over the past decade. The number of students enrolled in master’s and doctoral programs accredited by the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) has increased exponentially. In 2012, there were 36,977 master’s-level students and 2,028 doctoral students in CACREP-accredited programs (CACREP, 2013). By 2018, that number had risen to 52,861 master’s students (43% increase) and 2,917 doctoral students (44% increase; CACREP, 2019b). Counselor education programs have also expanded across the United States, following the merger between CACREP and the Council for Rehabilitation Education (CORE) in 2017 (CACREP, 2017). All 50 states and the District of Columbia now contain counselor education programs accredited by CACREP (CACREP, n.d.), though the number of programs can vary substantially across states (see Appendix).

This enrollment growth in CACREP-accredited master’s programs may be influenced by events that generated a greater need for graduates of master’s CACREP-accredited counselor education programs. In 2010, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) published standards that permitted licensed counselors to work independently within its system (T. A. Field, 2017). Subsequently in 2013, TRICARE, the military insurance for active military and retirees, created a new rule that would permit licensed counselors to join TRICARE panels and independently bill for services (U.S. Department of Defense, 2014). Both rules required candidates to graduate from a CACREP-accredited program as a basis for eligibility. The VA and TRICARE’s requirement for licensed counselors to graduate from CACREP-accredited programs to qualify for independent practice status was in response to a 2010 report issued by the Institute of Medicine, now known as the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Health and Medicine Division. The report recommended that professional counselors have “a master’s or higher-level degree in counseling from a program in mental health counseling or clinical mental health counseling that is accredited by CACREP” (p. 10). The additional legitimization of CACREP by the VA and TRICARE increased interest among counselor education programs to seek and maintain CACREP accreditation, especially for the master’s specialty of clinical mental health counseling (T. A. Field, 2017). In addition, graduation from a CACREP-accredited program has become a requirement for licensure in certain states (e.g., Ohio) within the past few years, following advocacy efforts by counselor leaders (Lawson et al., 2017). Lawson et al. (2017) and Mascari and Webber (2013) have proposed that establishing CACREP as the educational standard for licensure would strengthen the professional identity and place counseling on par with other master’s-level mental health professions that require graduation from an accredited program for licensure. Graduation from a CACREP-accredited program will also become a requirement for certification by the National Board for Certified Counselors (NBCC) as of 2024 (NBCC, 2018). These changes will likely bolster the valuing of CACREP accreditation by prospective students and also result in ever-increasing numbers of counseling programs that seek and maintain CACREP accreditation.

The growth in doctoral student enrollment (44%; CACREP, 2019b) may in part reflect the need for individuals with doctoral degrees to serve as counselor educators for these growing master’s programs. It is also likely due to a major change in faculty qualifications. To advance the professionalization of counseling (Lawson, 2016), the 2009 CACREP standards (2008) required all core faculty hired after 2013 to possess doctoral degrees in counselor education and supervision (CES), preferably from CACREP-accredited programs. From 2013 onward, newly appointed core faculty with doctorates in counseling psychology or other non-counseling disciplines could no longer qualify for faculty positions in CACREP-accredited doctoral CES programs. Lawson (2016) articulated that prior to this standard, an inequity existed whereby psychologists could be recruited for counselor education faculty positions, though counselor educators could not be hired for full-time psychology faculty positions. As a result, the psychology doctorate had a distinct advantage over the CES doctorate in the hiring of new faculty in counseling and psychology faculty positions (Lawson, 2016).

In light of these requirements for new faculty members in counselor education programs to possess doctorates in CES to qualify as core faculty, the hiring of new faculty members may be complicated by the available pool of qualified graduates. While counselor education programs routinely hire faculty from outside of their region, it seems possible that programs in regions with fewer counselor education doctoral programs may have greater difficulty in hiring counselor educators compared with programs in regions with numerous doctoral programs in CES. The extent of regional differences in the number of CES doctoral programs has not previously been quantitatively explored in the extant literature.

Regional Representation of Counselor Education Programs

Despite the national representation of CACREP-accredited programs and enrollment growth for both master’s and doctoral programs, the number of CACREP-accredited master’s and doctoral programs is not equally distributed and varies substantially by state and by region. Table 1 depicts that the national ratio of CACREP-accredited master’s-to-doctoral counselor education programs is roughly 9:1 (CACREP, n.d.). As seen in Table 1, these ratios vary by region as defined by national counselor education associations and organizations (i.e., North Atlantic, North Central, Rocky Mountain, Southern, Western regions). The North Central, Rocky Mountain, and Southern regions currently have a ratio of master’s-to-doctoral programs that ranges from 3:1 to 5:1. In comparison, the North Atlantic and Western regions have a 9:1 and 18:1 ratio of CACREP-accredited master’s-to-doctoral programs, respectively.

Table 1

Regional Representation of CACREP-Accredited Programs (December 2018)

| Region |

Population |

CACREP Doctoral Programs |

CACREP Master’s Programs |

Ratio of Master’s to Doctoral |

% States with Doctoral Programs |

Ratio of Population to Master’s Programs |

Ratio of Population to Doctoral Programs |

| North Atlantic |

57,780,705 |

8 |

75 |

9:1 |

36.4 |

770,409:1 |

7,222,588:1 |

| North Central |

72,251,823 |

23 |

104 |

5:1 |

69.2 |

694,729:1 |

3,141,384:1 |

| Rocky Mountain |

14,346,347 |

8 |

24 |

3:1 |

83.3 |

597,764:1 |

1,793,293:1 |

| Southern |

119,141,243 |

44 |

162 |

4:1 |

93.3 |

735,440:1 |

2,647,583:1 |

| Western |

63,647,316 |

2 |

35 |

18:1 |

28.6 |

1,818,495:1 |

31,823,658:1 |

| Total |

327,167,434 |

85 |

783 |

9:1 |

|

417,838:1 |

3,804,272:1 |

Note. Ratios rounded to closest whole number. Source of CACREP data: https://www.cacrep.org/directory/. Source of U.S. Census data: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-national-total.html#par_textimage_2011805803

This overall ratio of master’s-to-doctoral programs is likely to increase in the coming years, as a total of 63 master’s programs are in the process of applying for CACREP accreditation compared to only five doctoral programs, as depicted in the Appendix (i.e., 13:1 ratio). This 13:1 ratio exceeds the current 9:1 ratio. As seen in the Appendix, the regions with the highest ratios currently (North Atlantic and Western regions) have at least the same if not greater ratio of master’s-to-doctoral programs currently in the CACREP accreditation process (10:1 and 8:0 respectively), meaning that these unequal ratios will likely remain stable for some time to come. Although population size in states and regions may play some role in this unequal distribution, other factors likely contribute to this phenomenon. No previous literature has examined factors contributing to regional differences in the number of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs.

The confluence of (a) greater numbers of CACREP-accredited master’s programs, (b) greater student enrollment numbers in CACREP-accredited master’s programs, (c) CACREP requirements for hiring faculty to meet faculty–student ratios, and (d) the 2013 CACREP requirement for core faculty to possess doctorates in CES may together result in increased demand for hiring doctoral CES graduates to maintain CACREP accreditation. A pipeline problem may result from demand surpassing supply, with programs struggling to hire qualified doctoral graduates. This imbalance of supply and demand appears most exaggerated for faculty with expertise in school counseling (Bernard, 2006; Bodenhorn et al., 2014). Bodenhorn et al. (2014) expressed concern that the 2013 CACREP requirement for core faculty could limit enrollment in master’s programs. Although enrollment continues to climb in CACREP-accredited programs nationally, it is possible that regions with fewer doctoral programs may limit master’s enrollment because of difficulties with hiring additional core faculty. Programs in regions with fewer doctoral programs may struggle to convince candidates from other regions to relocate to their locale.

In the higher education literature, multiple studies have noted that location and proximity to home appears to be a fairly consistent reason for why prospective doctoral students, and later assistant professors, choose their doctoral programs and faculty positions, making recruitment from outside of a region difficult. Geographic location and proximity to home has been identified as the number one ranked reason for program selection in counselor education programs by master’s and doctoral students (Honderich & Lloyd-Hazlett, 2015) and in higher education doctoral programs (Poock & Love, 2001), and the second-ranked reason in marriage and family therapy doctoral programs (Hertlein & Lambert-Shute, 2007). Prospective students from underrepresented minority backgrounds appear to also consider the importance of community and geographic factors in doctoral program selection (Bersola et al., 2014). In a qualitative study by Linder and Winston Simmons (2015), proximity to family was an important factor in students choosing doctoral programs in student affairs. A qualitative study by Ramirez (2013) also found that proximity to home was a strong predictor of Latinx student choice of doctoral programs.

Very few studies exist into candidate selection of faculty positions at the completion of a doctoral CES program. The published studies that do exist have similarly found that location is again a primary consideration for new assistant professors when selecting their first faculty position. Magnuson et al. (2001) surveyed new assistant professors in counselor education and found that location was a primary factor for more than half of participants. New assistant professors considered proximity to family, geographical features, and opportunities for spouse when selecting their first faculty position (Magnuson et al., 2001). In more recent studies in other academic disciplines, geographic location remained a strong factor (though not the most important factor) for why academic job seekers chose faculty positions in hospitality (Millar et al., 2009) and accounting (Hunt & Jones, 2015). In academic medicine, geographic location was again a key reason for why candidates from underrepresented minority backgrounds selected faculty positions (Peek et al., 2013). It is worth noting that in the Millar et al. (2009) study, international students ranked geographic location as less important than their U.S. counterparts, though they ranked family ties to region as more important. It is possible that the rise of online positions may make location less of a factor in candidate job selection today compared to years past. Follow-up studies are needed to examine the role of geographic location in candidate selection of in-person and online faculty positions.

Although relatively few studies into the selection of faculty roles exist, location appears to be a consistent reason for why prospective doctoral students and later assistant professors choose their doctoral programs and faculty positions. Programs in regions with few doctoral programs may experience multiple layered challenges when hiring faculty. The master’s students in those regions have fewer options for doctoral study closer to home and therefore may need to consider leaving home and family to attend a doctoral program in a different region or attending a program with online or hybrid delivery options. Although online options are becoming more numerous, studies are needed to evaluate the frequency by which online doctoral graduates secure faculty positions versus in-person graduates, as this is currently unknown. It is possible that students may elect not to pursue doctoral study if they are unwilling to relocate, which potentially limits the pipeline of future faculty members who are originally from regions with fewer doctoral programs. Furthermore, doctoral graduates from other regions may have originally chosen their doctoral program in part because of geographical location, which may limit their openness to taking a faculty position in a region that has few doctoral programs. Thus, although counselor education programs in regions with fewer doctoral programs may need to hire candidates outside of the region, candidates from outside of the region may be less willing to move to a region with fewer doctoral programs. This may create difficulties for counselor education programs in regions with fewer doctoral programs that are seeking to fill open core faculty positions.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study was to begin to address the gap in what is known regarding the extent of regional differences for the number of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs in CES. To date, regional differences in the number of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs have not been studied. The researchers believed that gaining information about regional differences in the number of doctoral programs would be helpful in understanding the nature and extent of the pipeline problem in CES.

Methodology

The guiding research question was as follows: To what extent do regional differences exist in the number of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs in CES? The researchers identified two hypotheses: 1) There are differences in the number of doctoral programs by region even when controlling for population size, and 2) The number of CACREP-accredited master’s programs is a strong predictor of doctoral CACREP-accredited programs by state. Because counselor education programs must already have achieved master’s CACREP accreditation for a full 8 years in order to apply for doctoral CACREP accreditation (CACREP, 2019a), the researchers hypothesized that the number of doctoral programs by region would be directly related to the number of CACREP-accredited master’s programs in the region.

For the purposes of this study, the word program refers to a counseling academic unit housed within an academic institution offering one or more CACREP-accredited master’s counseling specialties that include addiction counseling; career counseling; clinical mental health counseling; clinical rehabilitation counseling; college counseling and student affairs; marriage, couple, and family counseling; rehabilitation counseling; or school counseling. These programs also may offer a doctorate in CES. In this study, master’s programs were tallied by program unit rather than specialization tracks within programs to avoid counting multiples for the same master’s program.

The researchers selected an ex post facto quantitative design to compare doctoral programs by region and state. Data were gathered through four sources: (a) CACREP-accredited master’s and doctoral counselor education programs on the CACREP (n.d.) website; (b) listing of population demographics and population density on the U.S. Census Bureau (2020) website; (c) listing of public and private colleges by state from the National Center for Education Statistics (n.d.) website; and (d) listing of counseling psychology doctoral programs accredited by the American Psychological Association (APA; 2019). Data for variables (b) through (d) were collected to ascertain whether the prediction of the number of CACREP-accredited master’s programs within states was complicated by extraneous variables such as state population size, state population density, number of colleges and universities in the state, and number of APA-accredited counseling psychology programs within states. Counseling psychology doctoral programs were identified as a potential predictor variable because doctoral programs in counseling psychology and CES are often considered competitor programs for resources such as faculty lines, as core faculty cannot be shared between APA- and CACREP-accredited programs (CACREP, 2015). Thus, a preponderance of counseling psychology doctoral programs within a state could potentially limit the number of CES doctoral programs within the same state.

The researchers limited the search to CACREP-accredited programs only because of the 2013 requirement for CACREP-accredited programs to specifically hire doctoral CES graduates. Programs that are not accredited by CACREP may subvert a regional pipeline problem by hiring faculty from related disciplines, such as psychology. For this reason, non–CACREP-accredited programs were excluded from the study. A 2018 CACREP report indicated that 405 programs in the United States were CACREP accredited (CACREP, 2019b). The percentage of counselor education programs in the United States that are CACREP accredited is unknown and most likely differs among states and regions. For example, 98% of master’s counselor education programs were CACREP accredited (52 of 53 programs) in Ohio, with the only non–CACREP-accredited program in the process of working toward accreditation. In comparison, only 24% of master’s counselor education programs in California (23 of 96 programs) were CACREP accredited. The large difference in CACREP representation between California and Ohio can partially be attributed to state regulatory issues. In Ohio, candidates for counseling licensure are required to graduate from CACREP-accredited programs. In contrast, California does not require CACREP accreditation and became the last state to license counselors in 2010 (T. A. Field, 2017). Specialized accreditation appears less common across professions in California. Despite having the most licensed marriage and family therapists (LMFTs) of any state, only 10% (8 of 82) of LMFT preparation programs in California are accredited by the Commission on the Accreditation for Marriage and Family Therapy Education (COAMFTE; n.d.). California is an outlier in the Western region, as 95% (38 of 40) of programs within the other states in that region (Alaska, Arizona, Hawai’i, Nevada, Oregon, Washington) were CACREP accredited.

Data Analysis

Data were entered into a Microsoft Excel worksheet and organized by the following columns: states, number of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs per state, number of CACREP-accredited master’s programs per state, state population size, state population density, number of colleges and universities per state, and the number of APA-accredited counseling psychology doctoral programs per state, and region. States were organized by regions defined by national counselor education associations and organizations (e.g., North Atlantic region, North Central region). Data from all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia were entered into the database.

To test the first and second hypotheses, data were analyzed using SPSS (Meyers et al., 2013). For the first hypothesis, a one-way analysis of co-variance (ANCOVA) for independent samples was selected to compare the number of doctoral programs by region, controlling for population size. The required significance level for the one-way ANCOVA was set to .05. The researchers determined the required sample size for .80 power, per Cohen’s (1992) guidelines. Per G*Power 3 (Faul et al., 2007), a one-way independent-samples ANCOVA requires a sample size of 42 states for .80 power at the .05 alpha level.

To test the second hypothesis, a linear multiple regression analysis (random model) was computed to identify predictor variables for the number of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs by state. Five predictor (i.e., independent) variables were entered into the regression equation. These predictor variables were as follows: (a) the number of CACREP-accredited master’s programs per state, (b) state population size, (c) state population density, (d) number of colleges and universities by state, and (e) number of APA-accredited counseling psychology programs per state. As described above, the presence of an APA-accredited counseling psychology program could potentially reduce the likelihood of a university also offering a CACREP-accredited counselor education program at the same institution. Per G*Power 3 (Faul et al., 2007), a linear multiple regression analysis (random model) requires a sample size of 39 states for .80 power at the .05 alpha level.

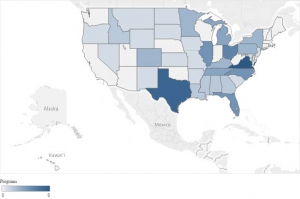

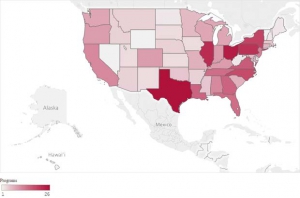

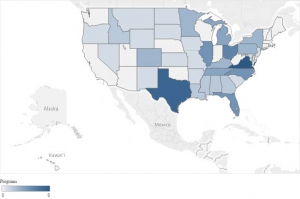

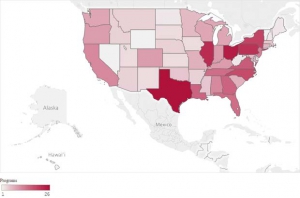

To further understand trends in the data regarding the regional representations of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs and CACREP-accredited master’s programs, data were also organized graphically via a data visualization platform (Tableau). These data for the number of programs by state are presented in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1

Geographical Representation of CACREP-Accredited Doctoral Programs in the United States

Note: To fit in image, Alaska was scaled down and the geographical locations of Alaska and Hawai’i were moved.

Figure 2

Geographical Representation of CACREP-Accredited Master’s Programs in the United States

Note: Data reflect number of total programs rather than number of specialized tracks per state. To fit in image, Alaska was scaled down and the geographical locations of Alaska and Hawai’i were moved.

Results

Table 1 and the Appendix display the number of CACREP-accredited doctoral and master’s programs by both region and state. The researchers used these data to test the hypotheses using inferential statistics.

Differences in CACREP-Accredited Doctoral Programs by Region

The researchers tested the hypothesis that significant differences existed for the number of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs among the five regions, even when the confounding variable of population size was controlled. The sample size of 51 exceeded the requirement for 80% power at the .05 alpha level (i.e., n = 42). Levene’s test for equality of error variances was not significant, indicating that parametric statistics could be performed without adjustments (A. Field, 2013). A one-way independent-samples ANCOVA for differences in number of programs by region was significant—F(4, 45) = 4.64, p < .05, η2 = .38—and represented a large effect size (Cohen, 1988).

The Southern region had the largest number of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs (n = 45). This was nearly twice the number of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs of the second-ranked region (North Central, n = 23), and more CACREP-accredited doctoral programs than the other four regions combined (n = 41). Compared to the Southern and North Central regions, the other three regions—namely the North Atlantic, Rocky Mountain, and Western regions—had substantially fewer CACREP-accredited doctoral programs. The North Atlantic and Rocky Mountain regions had eight CACREP-accredited doctoral programs each, and the Western region had two. The Southern region had the highest percentage of states with CACREP-accredited doctoral programs at 93% (14 of 15 states).

The number of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs per state was not equally distributed by region. Figure 1 and the Appendix show that in the Southern region, 14 of 15 states had CACREP-accredited doctoral programs, with two states having an especially high number of doctoral programs (i.e., Virginia = 9, Texas = 8). Other Southern region states (i.e., Maryland and South Carolina) only had a single doctoral program. In the North Atlantic region, counselor education programs were concentrated within specific geographic locations. The eight doctoral programs in the region were located within three states (i.e., New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania) and the District of Columbia. The remaining seven states, including the entirety of New England (i.e., Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont) have zero CACREP-accredited doctoral programs.

To better understand the relationship between doctoral programs and population size, ratios were computed comparing the population to doctoral and master’s programs by region. Table 1 depicts the ratio for population to doctoral programs by region. Upon further inspection of the data, it appears that population size could explain the number of doctoral programs in a region. For example, the Southern region had by far the greatest number of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs at 45, yet the proportion of programs was roughly equivalent for four of the five regions when considering the population size of those regions. As seen in Table 1, the population of the Southern region was 119 million people, which was 1.65 times the size of the next largest region, the North Central region (72 million). Accordingly, the number of doctoral programs in the Southern region was nearly double the number of programs in the North Central region (45 vs. 23). When examining the ratio of population to CACREP-accredited doctoral programs, the Southern region appears to have a roughly equivalent representation (2.6 million per doctoral program) to two other regions, the Rocky Mountain (1.8 million) and North Central (3.1 million) regions.

The Western region had the largest ratio of population to doctoral programs, at 31.8 million people per doctoral program. This ratio was more than four times greater than the next largest ratio (North Atlantic, 7.2 million per doctoral program) and 10 times the ratio of the other three regions (North Central, 3.1 million; Southern, 2.6 million; Rocky Mountain, 1.8 million). It was therefore evident that the Western region was most underrepresented in the number of CES doctoral programs per region inhabitant.

The Relationship Between CACREP-Accredited Doctoral and Master’s Programs

A linear multiple regression (random model) was computed to better understand the relationship between the number of CACREP-accredited master’s and doctoral programs per state. Other predictor variables included state population size, state population density, number of colleges and universities per state, and number of APA-accredited counseling psychology programs per state. The sample size of 51 exceeded the requirement for 80% power at the .05 alpha level (i.e., n = 39). Data conformed to homoscedasticity and did not show multicollinearity (A. Field, 2013). Residuals (errors) were equally distributed, and no significant outliers were found (A. Field, 2013). Because these assumptions were met, parametric statistics could be performed without adjustments (A. Field, 2013). The linear multiple regression (random model) variables significantly predicted the number of CACREP doctoral programs: F(5, 44) = 18.55, p < .05, R2 = .68. This represented a large effect size. Notably, only CACREP-accredited master’s programs were a significant predictor variable, with a standardized β coefficient of .85 (p < .05). The other predictor variables were not significant predictors and did not contribute to the multiple regression model. Thus, the presence of CACREP-accredited master’s programs accounted for 68% of the variance in doctoral programs by state.

Data in Table 1 help to elucidate the relationship between CACREP-accredited doctoral and master’s programs. The Southern region by far had the largest number of CACREP-accredited master’s programs (n = 162) and doctoral programs (n = 45). The second largest number of master’s programs was in the region with the second largest number of doctoral programs (North Central; 104 and 23, respectively). Some differences between doctoral and master’s program representation were found; the Rocky Mountain region had the smallest number of master’s programs at 24, which was three times less than the North Atlantic region, despite having the same number of doctoral programs (n = 8).

Figures 1 and 2 further clarify that although a relationship exists between the number of CACREP-accredited doctoral and master’s programs, there are important regional differences. In the West, several states had a relatively high number of master’s programs (e.g., California, Oregon, Washington) despite having one or even zero doctoral programs per state. In the North Atlantic region, New York and Pennsylvania had among the highest number of master’s programs by state, though these two states had relatively fewer doctoral programs. There were no CACREP-accredited doctoral programs and relatively few CACREP-accredited master’s programs in the entirety of New England (i.e., Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont), which is noteworthy because the area is known for the high number of colleges and universities, as well as high population density.

When reviewing ratios of master’s programs to population in Table 1, the Western region showed a far smaller representation of master’s programs compared to other regions. There were 1.8 million inhabitants per master’s program in the Western region. The Western region had more than double the ratio of the other four regions, who themselves have a fairly equivalent ratio of inhabitants per master’s program, ranging from 597,000 to 770,000.

Discussion

The results indicate a large and significant difference (p < .05, η2 = .38) in the number of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs by region when controlling for the confounding variable of population size. The number of CACREP-accredited master’s programs per state is also a large and significant predictor (standardized β = .85, p < .05) for the number of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs in a state. Other variables, such as state population size, state population density, number of colleges and universities per state, and number of APA-accredited counseling psychology programs, did not predict the number of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs in a state.

The Western region had by far the fewest number of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs, the smallest percentage of states with CACREP-accredited doctoral programs, the largest ratio of CACREP-accredited master’s-to-doctoral programs, and the largest ratio of population size to both master’s and doctoral CACREP-accredited programs. With only two CACREP-accredited doctoral programs in seven states, the Western region may experience a significant pipeline problem. It is worth noting that the number of CACREP-accredited master’s programs has doubled in the Western region since 2009, from 16 to 35 programs (CACREP, n.d.). During the same time period, the Western region has not gained any new CACREP-accredited doctoral programs. From an analysis of in-process programs, it seems that the Western region stands to gain further CACREP-accredited master’s programs but no CACREP-accredited doctoral programs in the near future, exacerbating any existing pipeline problem. In addition, the North Atlantic region has a relative lack of doctoral programs as compared to master’s programs. In the ensuing section, potential reasons for the lack of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs in the Western and North Atlantic regions, along with the potential impact of this problem, are discussed.

CES Doctoral Programs in the Western Region

The Western state of California was initially an early developer and adopter of counselor education accreditation standards, yet today it has relatively few CACREP-accredited master’s programs relative to population size and has never had a CACREP-accredited doctoral program. The California story is worth exploring in greater depth because it illustrates a further barrier to establishing doctoral CACREP programs in the Western region.

California is a major outlier in this study in that only 24% (n = 23) of 96 master’s degree programs in counseling (i.e., clinical mental health counseling; marriage, couple, and family counseling; school counseling) were CACREP accredited. One explanation for this low number is that it was not until 2010 that California granted licenses to professional counselors (T. A. Field, 2017). As mentioned earlier, licensure requirements (especially those that require CACREP accreditation) can increase the number of CACREP-accredited programs in a state, with Ohio being a notable example. It is also interesting to note that despite California’s long history of granting licenses to marriage and family therapists, COAMFTE (n.d.) was not a strong accreditation competitor to CACREP. As of 2019, only 10% (8) of 82 MFT licensable programs were COAMFTE accredited.

CES Doctoral Programs in the North Atlantic Region

The North Atlantic region had only eight CACREP-accredited doctoral programs, which were concentrated in three states (i.e., New Jersey, New York, District of Columbia). No CACREP-accredited doctoral programs were in the New England region (i.e., Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont). The North Atlantic region has several densely populated states, with New York and Pennsylvania being the fourth and fifth most populated states in the United States. The North Atlantic region also had a fairly large number of master’s CACREP-accredited programs (n = 75). As seen in Table 1, the North Atlantic region had roughly the same ratio of CACREP-accredited master’s programs to population size as the Southern region and yet had a ratio of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs to population size that was three times greater than the Southern region’s ratio. The North Atlantic region also had more than double the number of master’s programs than the Western region, despite having a smaller population overall. Considering this larger presence of CACREP-accredited master’s programs, the North Atlantic’s lack of doctoral programs is somewhat surprising.

The reason for the low number of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs in the North Atlantic region can be understood when considering the historical presence of APA-accredited counseling psychology doctoral programs in the region. Although not a predictor for the number of CES doctoral programs nationally, APA-accredited counseling psychology programs appear to be a potential barrier to CES doctoral program establishment in New England especially. Massachusetts had the second largest number of APA-accredited counseling psychology doctoral programs (n = 6), behind only Texas (n = 7; APA, 2019). As stated previously, university administrators may perceive doctoral programs in counseling psychology and CES as competitor programs for faculty lines, as core faculty cannot be shared between APA and CACREP-accredited programs (CACREP, 2015). The large number of counseling psychology doctoral programs in Massachusetts may help explain why there are no CES doctoral programs in New England.

CES Doctoral Programs Across Regions

Although the Western and North Atlantic regions had the greatest degree of pipeline problem, it is possible that all five regions will be impacted by the pipeline problem in the near future. An analysis of programs currently in the process of applying for CACREP accreditation (designated “in process”) is presented in the Appendix. Across regions, a total of 63 master’s programs were in process, compared to only five doctoral programs. This 12.6:1 ratio is far above the current ratios of the Southern, North Central, and Rocky Mountain regions and is similar to the current ratio for the North Atlantic region. All regions except the Rocky Mountain region appear to be impacted. The Southern region had 31 in-process master’s programs and three in-process doctoral programs (10:1 ratio). The North Central region had 13 in-process master’s programs and one in-process doctoral program (13:1). The North Atlantic region had 10 in-process master’s programs and one in-process doctoral program (10:1). The Western region had eight in-process master’s programs and zero in-process doctoral programs (8:0). The Rocky Mountain region seemed least impacted, with only one in-process master’s program and zero in-process doctoral programs (1:0). Any existing pipeline problem for doctoral-level counselor education faculty therefore seems likely to continue if not worsen in the coming years.

State Laws and Rules Prohibiting Doctoral Programs

In this study, the number of CACREP-accredited master’s programs is a strong predictor of the number of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs within a state. The relationship between the number of master’s and doctoral CACREP-accredited programs is far weaker in the Western region because of state laws and rules that restrict doctoral study at public universities. The California and Washington state university systems limit doctoral programs to their research-intensive universities. The California Master Plan (California State Department of Education, 1960; Douglass, 2000) restricts doctoral programs to the University of California university system and specifically does not permit Doctor of Philosophy degrees to be offered at the California State University system campuses. This is important because in California all of the counselor education programs at state universities are operated within the California State University system, with no programs offered within the research-intensive University of California system.

A similar dynamic exists within the Washington state educational system, whereby only the research-intensive universities (i.e., University of Washington, Washington State University) may offer doctoral degrees. As in California, master’s counselor education programs within Washington state universities are only operated within the teaching institutions (e.g., Central Washington University, Eastern Washington University, Western Washington University) and no programs are offered at the research-intensive state universities. Unfortunately, one of the first-ever CACREP-accredited doctoral programs was at the University of Washington, which closed its program and lost its CACREP accreditation status in 1988 (CACREP, n.d.).

State political dynamics are a significant barrier to starting new doctoral programs within the Western state public university systems. Because of state laws and regulations, the real need generated by the significant number of master’s counseling programs at teaching-focused and less research-intensive state universities in California and Washington has no real influence on doctoral program development. No new state university doctoral programs are on the horizon or even under consideration. Instead, new doctoral programs in Western states will likely only start at private universities. Unfortunately, these institutions tend to have higher tuition without the advantage of the graduate student funding that their state counterparts generally offer.

Pace (2016) found that institution type (i.e., public vs. private) and enrollment numbers for the institution were predictors of whether the institution had a CACREP-accredited doctoral program. As of 2018, the majority of doctoral programs were housed in public institutions (n = 64), with 19 programs at private institutions (CACREP, n.d.). Of these 19 programs at private institutions, 12 (63%) were at professional or master’s-level universities according to Carnegie classification (The Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education, 2019). Programs within private colleges and universities represented more than half of all programs (12 of 21 programs; 57%) at non–research-intensive universities (i.e., professional or master’s-level classifications). Private universities with professional and master’s-level classifications who develop doctoral CES programs seem less likely to have the financial support to offer scholarships and tuition waivers to students when compared to research institutions.

Student funding has historically been valued as a core principle of doctoral education. It often provides doctoral students with full-time opportunities to shadow faculty members and develop research self-efficacy (Lambie & Vaccaro, 2011), which is considered the primary focus of doctoral-level counselor education (Adkison-Bradley, 2013). Program faculty in these new private doctoral programs may face heavier workloads given the lack of student funding (e.g., increased teaching and advising loads) and support for faculty research and scholarship. This could potentially limit the research training available to doctoral students at these new institutions, which may hinder the ability for these doctoral students at emerging programs to be adequately prepared for the scholarly work required as a future faculty member. If unaddressed, these programs would not contribute to meeting the growing need for qualified doctoral counselor educators in the Western region, and the pipeline problem would continue.

For example, in Washington, several private universities with CACREP-accredited master’s programs (i.e., Antioch University-Seattle, City University of Seattle, Seattle Pacific University) have recently established doctoral programs in CES. In the three institutions, all new faculty hired after 2013 have completed doctoral degrees in CES from institutions outside of the Western region, with the majority of those doctorates being completed in the Southern region. Although not CACREP accredited at the time of writing, these new doctoral programs appear to be a potential solution to the pipeline problem in the Western region. However, it is worth noting that these three private universities are teaching institutions rather than research institutions, and such programs may need guidance regarding how to include sufficient research training in the doctoral curriculum if the program cannot offer funding to doctoral students and the faculty are not given support to generate faculty-led research and scholarship.

Impact of Doctoral Programs on Regional Professional Identity

Authors such as Lawson (2016) and Mascari and Webber (2013) have argued that CACREP accreditation strengthens the professional identity of the program and of students within the program. It is unknown whether the number of CACREP-accredited master’s and doctoral programs within a region also strengthens and contributes to professional identity within a region. There are no existing published studies that have comprehensively examined the regional impact of the number of CACREP-accredited master’s and doctoral programs on professional identity. Anecdotally, there appear to be several potential effects from having a lack of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs within a region. CACREP-accredited master’s counseling programs must recruit new faculty hires from outside of the region if there is an insufficient number of candidates available from established doctoral programs within the region. Because the Western region and New England states have a dearth of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs, counselor education programs in those states may need to recruit from outside of their region to find suitable candidates. As mentioned previously, this pipeline problem can make recruiting difficult, as candidates strongly weigh location and closeness to home when selecting doctoral programs (Hertlein & Lambert-Shute, 2007; Honderich & Lloyd-Hazlett, 2015; Poock & Love, 2001) and faculty positions (Hunt & Jones, 2015; Magnuson et al., 2001; Millar et al., 2009). Location appears to be a particularly important consideration for candidates from underrepresented minority backgrounds (Bersola et al., 2014; Linder & Winston Simmons, 2015; Peek et al., 2013; Ramirez, 2013). As a result, prospective doctoral students and faculty members may be unwilling to study or work at a program outside of their home region.

Online CACREP-accredited doctoral programs may create pathways for more students in a region with a lack of doctoral programs to pursue and attain a doctorate in counselor education, which may reduce any existing pipeline problem. Studies are needed to examine comparative hiring rates of online versus in-person programs to ascertain whether graduates of online programs are filling needed faculty positions. Hiring school counselor educators is particularly challenging (Bernard, 2006), and studies are needed that examine the proportion of school counselor educators that graduate from online counseling programs.

Counselor education programs are continually seeking to increase the diversity of their faculty (Cartwright et al., 2018; Holcomb-McCoy & Bradley, 2003; Shin et al., 2001; Stadler et al., 2006). Because prospective doctoral students from minority backgrounds may be more inclined to restrict their applications to doctoral programs within close proximity to their current location (Bersola et al., 2014; Linder & Winston Simmons, 2015; Ramirez, 2013), online doctoral programs appear to be a viable option for students from culturally diverse backgrounds who live in regions with few in-person doctoral programs. Data are needed to support whether online graduates are (a) filling open faculty vacancies in the Western region and New England states, (b) filling school counselor educator positions, and (c) contributing to faculty diversity.

This study represents the first-ever analysis of regional differences in the number of CACREP-accredited doctoral CES programs. Because this was an ex post facto study, the results are non-experimental and thus have the potential for error because of the lack of experimental control and randomization. To mitigate the potential for error, the confounding variable of population size was included in our inferential statistical analyses. Examination of variables such as the demand for counselor education program entry are also important to examine in the future to ascertain whether programs are turning away students because of capacity issues related to faculty hiring. Such studies could appraise application numbers, enrollment numbers, and the program’s ideal yield should capacity not be an issue. Furthermore, a more detailed analysis into the relationship between a state’s educational requirements for licensure (i.e., whether graduates must complete a CACREP-accredited program) and the demand for doctoral counselor educators within a state is important. Lawson et al. (2017) have proposed that advocating for CACREP accreditation as the educational requirement for counselor licensure is important to the advancement of professionalization and professional identity. It is possible that the lack of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs in a state may be a barrier to establishing CACREP as the educational standard for licensure.

Conclusion

A large and statistically significant difference exists in the number of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs by region, even when controlling for population size. The Western region has by far the fewest doctoral programs and thus the greatest need for new doctoral programs. The lack of doctoral programs in the Western region and New England states may present a pipeline problem. The number of CACREP-accredited master’s programs has doubled in the Western region since 2009 while the number of doctoral programs has remained the same. As a result, CACREP-accredited master’s programs in the Western region and New England states may struggle to recruit qualified core faculty from in-region doctoral programs. The ratio of in-process master’s versus doctoral programs suggests that any existing pipeline issue will continue if not worsen in the coming years.

Even though the number of CACREP-accredited master’s programs within a state appears to be a strong independent predictor of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs, new doctoral programs may be difficult to establish because of state regulatory issues, the existence of competing doctoral programs (e.g., counseling psychology), or the lack of research support infrastructure (e.g., smaller teaching loads, funding for doctoral students).

In addition to small, private, teaching-focused institutions that seem to be developing doctoral programs in regions with few CACREP-accredited doctoral programs (e.g., Antioch University-Seattle, City University of Seattle, and Seattle Pacific University in the Western region), online CACREP-accredited doctoral CES programs are a potential solution to training prospective doctoral students in regions with few in-person doctoral programs. Online programs may also help to address any existing specific pipeline issues regarding faculty with school counseling specialties and faculty from culturally diverse backgrounds. Future studies are needed to support whether online CACREP-accredited doctoral programs are helping master’s programs to address these recruitment needs. Additional follow-up studies are also needed to examine the role of geographic location in candidate selection of in-person and online faculty positions, as it is possible that geographic location has less prominence in candidate selection of faculty roles today compared to several decades ago when prior studies in counselor education were conducted (e.g., Magnuson et al., 2001).

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Adkison-Bradley, C. (2013). Counselor education and supervision: The development of the CACREP doctoral standards. Journal of Counseling and Development, 91(1), 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2013.00069.x

Altekruse, M. K., & Wittmer, J. (1991). Accreditation in counselor education. In F. O. Bradley (Ed.), Credentialing in counseling (pp. 53–67). Association for Counselor Education and Supervision.

American Psychological Association. (2019). APA-accredited programs. https://www.apa.org/ed/accreditation/programs

/using-database

Bernard, J. M. (2006). Counselor education and counseling psychology: Where are the jobs? Counselor Education and Supervision, 46(1), 68–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2006.tb00013.x

Bersola, S. H., Stolzenberg, E. B., Love, J., & Fosnacht, K. (2014). Understanding admitted doctoral students’ institutional choices: Student experiences versus faculty and staff perceptions. American Journal of Education, 120(4), 515–543. https://doi.org/10.1086/676923

Bodenhorn, N., Hartig, N., Ghoston, M. R., Graham, J., Lile, J. J., Sackett, C., & Farmer, L. B. (2014). Counselor education faculty positions: Requirements and preferences in CESNET announcements 2005-2009. Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 6(1), 1–16.

California State Department of Education (1960). A master plan for higher education in California: 1960-1975. https://www.ucop.edu/acadinit/mastplan/MasterPlan1960.pdf

The Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education. (2019). Basic classification description. http://carnegieclassifications.iu.edu/classification_descriptions/basic.php

Cartwright, A. D., Avent Harris, J. R., Munsey, R. B., & Lloyd-Hazlett, J. (2018). Interview experiences and diversity concerns of counselor education faculty from underrepresented groups. Counselor Education and Supervision, 57(2), 132–146. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12098

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Erlbaum.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

Commission on Accreditation for Marriage and Family Therapy Education. (n.d.). Directory of COAMFTE accredited programs. Retrieved January 20, 2020, from https://coamfte.org/COAMFTE/Directory_of_Accredited_Programs/

MFT_Training_Programs.aspx

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (n.d.). Find a program. Retrieved January 20, 2020, from https://www.cacrep.org/directory

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2008). CACREP 2009 standards. http://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/2009-Standards.pdf

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2013). 2012 annual report. http://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/CACREP-2012-Annual-Report.pdf

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2015). CACREP 2016 standards. http://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/2016-Standards-with-citations.pdf

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2017). CACREP/CORE merger information. https://www.cacrep.org/home/cacrepcore-updates

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2019a). CACREP policy document. http://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/2016-Policy-Document-January-2019-revision.pdf

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2019b). Annual report 2018. http://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/CACREP-2018-Annual-Report.pdf

Douglass, J. A. (2000). The California idea and American higher education: 1850 to the 1960 master plan. Stanford University Press.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics (4th ed.). SAGE.

Field, T. A. (2017). Clinical mental health counseling: A 40-year retrospective. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 39(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.39.1.01

Hertlein, K. M., & Lambert-Shute, J. (2007). Factors influencing student selection of marriage and family therapy graduate programs. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 33(1), 18–34.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2007.00002.x

Holcomb-McCoy, C., & Bradley, C. (2003). Recruitment and retention of ethnic minority counselor educators: An exploratory study of CACREP-accredited counseling programs. Counselor Education and Supervision, 42(3), 231–243. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2003.tb01814.x

Honderich, E. M., & Lloyd-Hazlett, J. (2015). Factors influencing counseling students’ enrollment decisions: A focus on CACREP. The Professional Counselor, 5(1), 124–136. https://doi.org/10.15241/emh.5.1.124

Hunt, S. C., & Jones, K. T. (2015). Recruitment and selection of accounting faculty in a difficult market. Global Perspectives on Accounting Education, 12, 23–51.

Institute of Medicine. (2010). Provision of mental health counseling services under TRICARE. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/12813

Lambie, G. W., & Vaccaro, N. (2011). Doctoral counselor education students’ levels of research self-efficacy, perceptions of the research training environment, and interest in research. Counselor Education and Supervision, 50(4), 243–258. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2011.tb00122.x

Lawson, G. (2016). On being a profession: A historical perspective on counselor licensure and accreditation. Journal of Counselor Leadership and Advocacy, 3(2), 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/2326716X.2016.1169955

Lawson, G., Trepal, H. C., Lee, R. W., & Kress, V. (2017). Advocating for educational standards in counselor licensure laws. Counselor Education and Supervision, 56(3), 162–176. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12070

Linder, C., & Winston Simmons, C. (2015). Career and program choice of students of color in student affairs programs. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 52(4), 414–426.

https://doi.org/10.1080/19496591.2015.1081601

Magnuson, S., Norem, K., & Haberstroh, S. (2001). New assistant professors of counselor education: Their preparation and their induction. Counselor Education and Supervision, 40(3), 220–229.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2001.tb01254.x

Mascari, J. B., & Webber, J. (2013). CACREP accreditation: A solution to license portability and counselor identity problems. Journal of Counseling & Development, 91(1), 15–25.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2013.00066.x

Meyers, L. S., Gamst, G. C., & Guarino, A. J. (2013). Performing data analysis using IBM SPSS. Wiley.

Millar, M., Kincaid, C., & Baloglu, S. (2009). Hospitality doctoral students’ job selection criteria for choosing a career in academia. Hospitality Management, 7. https://repository.usfca.edu/hosp/7

National Board for Certified Counselors. (2018, August). NBCC delays start of new standard to obtain certification. NBCC Visions. https://nbcc.informz.net/NBCC/pages/August2018CACREPdelay?_zs=z9bqb&_zmi=?

National Center for Education Statistics. (n.d.). College navigator. Retrieved January 20, 2020, from https://nces.ed.gov/collegenavigator

Pace, R. L., Jr. (2016). Relationship of institutional characteristics to CACREP accreditation of doctoral counselor education programs [Doctoral dissertation, Walden University]. ScholarWorks. https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations/2097

Peek, M. E., Kim, K. E., Johnson, J. K., & Vela, M. B. (2013). “URM candidates are encouraged to apply”: A national study to identify effective strategies to enhance racial and ethnic faculty diversity in academic departments of medicine. Academic Medicine, 88(3), 405–412. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318280d9f9

Poock, M. C., & Love, P. G. (2001). Factors influencing the program choice of doctoral students in higher education administration. NASPA Journal, 38(2), 203–223. https://doi.org/10.2202/1949-6605.1136

Ramirez, E. (2013). Examining Latinos/as’ graduate school choice process: An intersectionality perspective. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 12(1), 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538192712452147

Shin, R. Q., Smith, L. C., Goodrich, K. M., & LaRosa, N. D. (2011). Attending to diversity representation among Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) master’s programs: A pilot study. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 33(2), 113–126.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-011-9116-6

Stadler, H. A., Suh, S., Cobia, D. C., Middleton, R. A., & Carney, J. S. (2006). Reimagining counselor education with diversity as a core value. Counselor Education and Supervision, 45(3), 193–206.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2006.tb00142.x

U.S. Census Bureau. (2020). National population totals and components of change. https://www.census.gov/data/tab

les/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-national-total.html#par_textimage_2011805803

U.S. Department of Defense. (2014, July 17). TRICARE certified mental health counselors. 32 CFR Part 199. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2014/07/17/2014-16702/tricare-certified-mental-health-counselors

Wittmer, J. (2010). Evolution of the CACREP standards. In A. K. Mobley and J. E. Myers (Eds.), Developing and maintaining counselor education laboratories (2nd ed.). Association of Counselor Education and Supervision. https://acesonline.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Developing-and-Maintaining-Counselor-Education-Laboratories-Full-Text.pdf

Appendix

CACREP-Accredited and In-Process Programs by State and Region (December 2018)

| State |

Region |

Population |

CACREP Doctoral Programs |

CACREP Master’s Programs |

Doctoral Programs “In Process” of CACREP Accreditation |

Master’s Programs “In Process” of CACREP Accreditation |

| Connecticut |

North Atlantic |

3,572,665 |

|

6 |

|

1 |

| Delaware |

North Atlantic |

967,171 |

|

1 |

|

|

| District of Columbia |

North Atlantic |

702,455 |

1 |

4 |

|

3 |

| Maine |

North Atlantic |

1,338,404 |

|

2 |

|

|

| Massachusetts |

North Atlantic |

6,902,149 |

|

5 |

|

1 |

| New Hampshire |

North Atlantic |

1,356,458 |

|

2 |

|

1 |

| New Jersey |

North Atlantic |

8,908,520 |

1 |

12 |

|

|

| New York |

North Atlantic |

19,542,209 |

3 |

19 |

|

4 |

| Pennsylvania |

North Atlantic |

12,807,060 |

3 |

21 |

1 |

|

| Rhode Island |

North Atlantic |

1,057,315 |

|

2 |

|

|

| Vermont |

North Atlantic |

626,299 |

|

1 |

|

|

| |

North Atlantic |

57,780,705 |

8 |

75 |

1 |

10 |

| Illinois |

North Central |

12,741,080 |

5 |

22 |

|

3 |

| Indiana |

North Central |

6,691,878 |

|

9 |

|

2 |

| Iowa |

North Central |

3,156,145 |

1 |

3 |

|

|

| Kansas |

North Central |

2,911,505 |

1 |

3 |

|

|

| Michigan |

North Central |

9,995,915 |

4 |

8 |

|

1 |

| Minnesota |

North Central |

5,611,179 |

3 |

6 |

|

1 |

| Missouri |

North Central |

6,126,452 |

1 |

7 |

|

3 |

| Nebraska |

North Central |

1,929,268 |

|

4 |

|

|

| North Dakota |

North Central |

760,077 |

1 |

2 |

|

|

| Ohio |

North Central |

11,689,442 |

6 |

24 |

|

2 |

| Oklahoma |

North Central |

3,943,079 |

|

5 |

|

|

| South Dakota |

North Central |

882,235 |

1 |

3 |

|

|

| Wisconsin |

North Central |

5,813,568 |

|

8 |

1 |

1 |

| |

North Central |

72,251,823 |

23 |

104 |

1 |

13 |

| Colorado |

Rocky Mountain |

5,695,564 |

3 |

9 |

|

|

| Idaho |

Rocky Mountain |

1,754,208 |

2 |

4 |

|

|

| Montana |

Rocky Mountain |

1,062,305 |

1 |

4 |

|

|

| New Mexico |

Rocky Mountain |

2,095,428 |

1 |

3 |

|

1 |

| Utah |

Rocky Mountain |

3,161,105 |

|

3 |

|

|

| Wyoming |

Rocky Mountain |

577,737 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

| |

Rocky Mountain |

14,346,347 |

8 |

24 |

0 |

1 |

| Alabama |

Southern |

4,887,871 |

2 |

11 |

|

1 |

| Arkansas |

Southern |

3,013,825 |

1 |

4 |

|

1 |

| Florida |

Southern |

21,299,325 |

5 |

14 |

|

3 |

| Georgia |

Southern |

10,519,475 |

2 |

15 |

2 |

3 |

| Kentucky |

Southern |

4,468,402 |

3 |

9 |

1 |

|

| Louisiana |

Southern |

4,659,978 |

2 |

15 |

|

1 |

| Maryland |

Southern |

6,042,718 |

1 |

6 |

|

2 |

| Mississippi |

Southern |

2,986,530 |

2 |

5 |

|

|

| North Carolina |

Southern |

10,383,620 |

5 |

18 |

|

1 |

| South Carolina |

Southern |

5,084,127 |

1 |

7 |

|

|

| Tennessee |

Southern |

6,770,010 |

4 |

14 |

|

7 |

| Texas |

Southern |

28,701,845 |

8 |

26 |

|

8 |

| Virginia |

Southern |

8,517,685 |

9 |

16 |

|

4 |

| West Virginia |

Southern |

1,805,832 |

|

2 |

|

|

| |

Southern |

119,141,243 |

45 |

162 |

3 |

31 |

| Alaska |

Western |

737,438 |

|

1 |

|

|

| Arizona |

Western |

7,171,646 |

|

4 |

|

|

| California |

Western |

39,557,045 |

|

11 |

|

6 |

| Hawaii |

Western |

1,420,491 |

|

1 |

|

|

| Nevada |

Western |

3,034,392 |

1 |

1 |

|

2 |

| Oregon |

Western |

4,190,713 |

1 |

9 |

|

|

| Washington |

Western |

7,535,591 |

|

8 |

|

|

| |

Western |

63,647,316 |

2 |

35 |

0 |

8 |

| |

Grand Total |

327,167,434 |

86 |

400 |

5 |

63 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

*Ratios rounded to closest whole number. Source of CACREP data: https://www.cacrep.org/directory/. Source of U.S. Census data: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-national-total.html#par_textimage_2011805

Thomas A. Field, PhD, NCC, CCMHC, ACS, LPC, LMHC, is an assistant professor at the Boston University School of Medicine. William H. Snow, PhD, is a professor at Palo Alto University. J. Scott Hinkle, PhD, ACS, BCC, HS-BCP, is a core faculty member at Palo Alto University. Correspondence may be addressed to Thomas Field, 72 E Concord St., Suite B-210, Boston, MA 02118, tfield@bu.edu.

Dec 16, 2020 | Volume 10 - Issue 4

Jennifer Preston, Heather Trepal, Ashley Morgan, Justin Jacques, Joshua D. Smith, Thomas A. Field

The doctoral degree in counselor education and supervision is increasingly sought after by students, with the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) reporting a 27% enrollment increase in just a 4-year span. As new programs are started and existing programs sustained, administrators and faculty may be seeking guidance in how to build a high-quality program. Yet no literature currently exists for how doctoral counseling faculty define a high-quality program. This study used a basic qualitative research design to examine faculty perceptions of high-quality doctoral programs (N = 15). The authors analyzed data from in-depth interviews with core faculty members at CACREP-accredited doctoral programs. Five themes emerged from the data: relationships, mission alignment, development of a counselor educator identity, inclusiveness of diversity, and Carnegie classification. The findings of this study can be important for faculty and administrators to consider when establishing and maintaining a counselor education and supervision doctoral program.

Keywords: doctoral programs, counselor education and supervision, CACREP, faculty perceptions, high-quality

Doctoral education in counselor education and supervision (CES) is surging, with both the number of programs and enrollment head count increasing over the past few years. According to the most recent annual report from the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP), there are currently 85 CACREP-accredited CES doctoral programs (CACREP, 2019b) compared to 63 in 2014 (CACREP, 2017). This constitutes a 35% increase over a 4-year span. In addition, enrollment in CACREP-accredited doctoral programs has increased from 2,291 in 2014 to 2,917 in 2018, a 27% increase (CACREP, 2017, 2019a). The number of doctoral graduates in CES also increased by 35% between 2017 and 2019, from 355 to 479 (CACREP, 2017, 2019a). A registry does not exist for non–CACREP-accredited programs, and thus the exact number of doctoral programs in CES (i.e, CACREP- and non–CACREP-accredited programs) is unknown.

According to Hinkle et al. (2014), students’ motivations to pursue a doctorate in CES include

(a) to become a professor, (b) to be a respected professional with job security, (c) to become a clinical leader, and (d) to succeed for family and community amid obstacles. Student motivations appear tempered by CES departmental culture, mentoring, academics, support systems, and personal and related issues that impact their doctoral experience (Protivnak & Foss, 2009).

While students enter CES programs with one set of motivations, the programs themselves have their own goals for whom they admit, how they train, and what they perceive as a desired outcome to doctoral training. Doctoral programs in CES are considered training grounds for shaping students’ professional (Dollarhide et al., 2013; Limberg et al., 2013) and research identities (Perera-Diltz & Sauerheber, 2017). In addition, mentoring and advising relationships are viewed as important to supporting research motivation and productivity (Kuo et al., 2017).

Given students’ motivations and expectations for career preparation and advancement, it would make sense that they would want to choose a doctoral program that fits their needs. In addition to matching academic needs, it can also be assumed that as consumers of doctoral education, students would want to choose a high-quality doctoral program in CES. Bersola et al. (2014) conducted a study into factors that influenced admitted doctoral students’ (N = 540) choice of program. The students in the study were all from programs and departments located within one university. Both underrepresented minority and majority students cited program reputation, institutional reputation, faculty quality, research quality, and faculty access/availability as primary reasons for their choice of doctoral program. Participants reported these factors as more important to their choice of doctoral program than non–quality-related factors such as cost of living, housing, location, and urbanity (Bersola et al., 2014).

There are many program options for CES doctoral study, but little is known about what constitutes a high-quality program in counselor education apart from CACREP accreditation. Although the perceptions of CES doctoral graduates remain unknown, researchers have utilized data from doctoral graduates across disciplines regarding their satisfaction with their programs (Barnes & Randall, 2012; Morrison et al., 2011). Graduates identified aspects such as academic rigor, funding opportunities, mentoring in meeting program requirements, research skill training, and developing a sense of community as contributing to their satisfaction and perceptions of the doctoral programs (Barnes & Randall, 2012; Morrison et al., 2011).

Despite considerable knowledge of doctoral graduates’ perceptions, little is known about faculty perspectives on these issues (Kim et al., 2015). There is evidence that faculty perceptions of doctoral program quality can differ from alumni perceptions. Morrison et al. (2011) examined program faculty and alumni perceptions of quality doctoral education in the social sciences. Both faculty and alumni considered training in research skills and diversity characteristics of the program as important to quality. However, alumni also tended to place greater emphasis on the importance of faculty support in meeting program requirements and fostering belonging, whereas program faculty placed greater emphasis on the scholarly reputation of faculty when defining doctoral program quality.

Purpose of the Present Study

Very few studies have explored program faculty perceptions of high-quality doctoral education, and no studies exist in CES specifically. As educators and mentors, faculty who teach in CES programs should be both interested and invested in enhancing educational environments that meet students’ career aspirations as well as advancing the profession. Although industry standards for quality exist (e.g., CACREP standards), there is a need to better understand which components CES faculty believe comprise a high-quality doctoral program in CES. The purpose of this study was to address this gap in knowledge.

Methodology

This particular study was conducted as part of a larger comprehensive qualitative study of CES doctoral programs organized by the last author that followed the basic qualitative research design described by Merriam and Tisdell (2016). In the basic qualitative research paradigm, the research team collects, codes, and categorizes qualitative data using the constant comparative method from grounded theory methodology (Corbin & Strauss, 2015; Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). The researchers first use open coding, followed by categorization using axial coding to identify themes in the data (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). Data collection continues until data reach saturation and redundancy. Unlike other qualitative traditions, this qualitative design is not employed to develop theory (i.e., grounded theory), capture the essence of a lived experience (i.e., phenomenology), nor describe cultural and environmental observations (i.e., ethnography; Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). Instead, researchers using basic qualitative designs seek to collect and analyze qualitative data for the purpose of answering research questions outside other specialized qualitative focus areas. A qualitative design was selected because the authors shared an underlying philosophical belief in the constructivist position that participants’ reality was socially co-constructed and that all responses should be given importance regardless of frequency (Lincoln & Guba, 2013).

The basic qualitative design was selected because it best fit the purpose of this larger qualitative project. The purpose of the larger qualitative study was to identify current perceptions of doctoral-level counselor educators regarding four major issues pertinent to doctoral counselor education: (a) components of high-quality programs, (b) strategies to recruit and retain underrepresented students, (c) strategies for working with administrators, and (d) strategies for successful dissertation advising. Our study collected and analyzed in-depth interviews with doctoral-level counselor educators to answer a series of research questions that addressed the issues above pertaining to doctoral-level counselor education.

Interview questions were designed to directly answer each research question. The research questions explored in the larger project were as follows: 1) What are the components of high-quality doctoral programs in CES, and what are the most and least important components? 2) Which strategies are doctoral programs using to recruit, support, and retain underrepresented doctoral students from diverse backgrounds, and how successful are those? 3) Which strategies are helpful in gaining initial and ongoing support from administrators when seeking to start a new doctoral program in CES, and how successful are those? and 4) Which strategies help students navigate the dissertation process, and how successful are those?

This manuscript represents the first of four articles from the larger qualitative project that each addressed one of the research questions listed above. This study therefore examined the first research question and sought to identify the components of high-quality doctoral programs in CES. The interview questions directly addressed this research question and were as follows: 1) How might you define a high-quality doctoral program in CES? and 2) What do you believe to be the most and least important components?

Participants