Aug 10, 2022 | Volume 12 - Issue 2

Gregory T. Hatchett

This study involved a longitudinal analysis of the journal article publications accrued by counselor educators at comprehensive universities over the first 20 years since receiving their doctoral degrees. A review of electronic databases revealed these counselor educators accrued a median of three journal article publications over the first 20 years since degree completion. Faculty rank, inferred binary gender, and the date of terminal degree all predicted cumulative journal article publication counts. An analysis of sequence charts revealed that journal article publication counts are not invariant over the first 20 years since degree completion, but vary based on time, faculty rank, and inferred binary gender. The implications of this research for counselor education training are discussed.

Keywords: counselor educators, journal article publications, faculty rank, comprehensive universities, gender

The primary purpose of doctoral-level training in counselor education is to prepare program graduates for careers as counselor educators and clinical supervisors (Snow & Field, 2020). Consistent with this objective, graduates of counselor education and supervision programs accredited by the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) are required to attain numerous research competencies that will equip them for making scholarly contributions to the counseling literature (CACREP, 2015). Likewise, the PhD degree, which is the terminal degree offered to graduates of nearly all these programs, has been traditionally designed to prepare graduates for research and teaching in higher education (e.g., Dill & Morrison, 1985).

Be that as it may, most graduates of counselor education and supervision programs do not become faculty members, let alone faculty at research-intensive universities (e.g., Lawrence & Hatchett, 2022; Schweiger et al., 2012; Zimpfer, 1996). For example, Lawrence and Hatchett (2022) recently investigated the occupational outcomes of 314 graduates of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs. Overall, they found that 41.4% of these graduates had some type of faculty position in higher education. However, faculty positions as assistant professors in CACREP-accredited programs were much less common (23.9% of the total sample), and assistant professor positions in CACREP-accredited counseling programs at universities classified by the Carnegie Classification System (https://carnegieclassifications.acenet.edu) as either R1 (Very high research activity) or R2 (High research activity) were relatively rare (8.3% of the total sample). Thus, fewer than 1 in 10 of these recent program graduates attained professor positions at universities that expect high levels of scholarly productivity.

At the time of this writing, 401 colleges and universities in the United States and Puerto Rico have at least one CACREP-accredited counseling program. However, only 134 (33.5%) of these institutions have a Carnegie Classification of either an R1 or R2. More common are CACREP-accredited programs at master’s degree–granting institutions designated by the Carnegie system as M1 (Larger programs), M2 (Medium programs), or M3 (Smaller programs). Many of these universities would fall under the general umbrella of what are commonly denoted as comprehensive universities. At comprehensive universities, the focus is typically on undergraduate education, and graduate education tends to be limited to master’s degrees in professional disciplines, such as education and business (Youn & Price, 2009). Compared to their colleagues at research-intensive universities, faculty at comprehensive universities tend to have high teaching loads and greater expectations for service along with substantially lower expectations for faculty scholarly productivity (Hatchett, 2021; Henderson, 2011).

Though the scholarship expectations are lower, counselor educators at comprehensive universities are still commonly expected to exhibit some level of scholarly productivity for performance evaluations as well as tenure and promotion decisions (Fairweather, 2005; Hatchett, 2020; Youn & Price, 2009). Specific to counselor education, Hatchett (2020) recently surveyed 168 counselor educators about their perceptions of the tenure process, workloads, and their annual scholarly productivity. Regarding journal article publications, these counselor educators reported accruing a median of 0.45 national or international journal article publications a year. However, there is reason to believe that this sample statistic may be an overestimate. For one, only about 20% of the counselor educators at comprehensive universities completed the survey. Secondly, the rate of journal article publications reported by this sample of counselor educators greatly exceeds estimates attained from archival research.

For example, Hatchett et al. (2020) assessed the journal article publications of a large sample (N = 821) of counselor educators employed in CACREP-accredited master’s-level counseling programs housed in comprehensive universities. To identify peer-reviewed journal articles, they searched these counselor educators’ names through three electronic databases (i.e., PsycINFO, ERIC, Academic Search Complete) for the time interval of January 1, 2008, through December 31, 2017. They found that these counselor educators had attained a median of only 1 (M = 1.99, SD = 3.46) peer-reviewed publication over this

10-year time interval; notably, nearly half of this sample (n = 381, 46.4%) did not have any journal article publications indexed in any of the three databases. Granted, these three electronic databases do not capture all the journal article publications attained by counselor educators. Nonetheless, the gap between self-report (Hatchett, 2020) and archival publication estimates (Hatchett et al., 2020) is so large that it probably cannot be explained away by publications that were not referenced in any of these databases.

A second shortcoming of the archival research by Hatchett et al. (2020) was its cross-sectional nature. A cross-section cannot directly answer the question as to whether publication rates might vary or decline over the course of counselor educators’ careers. Hatchett et al. (2020) and Lambie et al. (2014) found some evidence that journal article publications may decline over counselor educators’ careers. To better evaluate this phenomenon, Lambie et al. recommended that future researchers use a longitudinal research design that tracks publication counts across time. Not only would a longitudinal design better detect changes and trends in publication rates across time, but such a design could also better illuminate the extent to which counselor educators at comprehensive universities publish in peer-reviewed journals across their careers.

Purpose of the Present Study

Accordingly, the purpose of the current study was to use a longitudinal research design to summarize and track the rate of journal article publications by counselor educators at comprehensive universities over an extended period of time. Specifically, this study assessed the cumulative journal article publications attained by counselor educators at master’s-only counseling programs at comprehensive universities for the first 20 years since receiving their terminal degrees. A secondary objective of this study was to evaluate whether factors identified in previous research would also be useful for predicting journal article publication counts in this sample. Previous researchers have found that binary gender (Lambie et al., 2014; Newhart et al., 2020; Ramsey et al., 2002), faculty rank (Hatchett et al., 2020; Newhart et al., 2020; Ramsey et al., 2002), and year of degree completion (Hatchett et al., 2020; Lambie et al., 2014) predict journal article publication counts. Thus, these same three variables were used to predict cumulative journal article publication counts accrued by these counselor educators over the 20 years since their degree completion.

Method

Procedures and Participants

Because this study involved only the collection and analysis of publicly available data, the internal IRB determined this study was exempt from IRB oversight. As in the methodology used by Hatchett et al. (2020), a comprehensive university was operationally defined as an institution classified by the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education as a master’s-level institution with a designation of M1 (Larger programs), M2 (Medium programs), or M3 (Smaller programs). In addition, any M1, M2, or M3 institution was excluded from this study if it did not denote at least part of its faculty with traditional academic ranks (i.e., assistant professor, associate professor, professor) or if the program also offered a doctoral degree program in counseling or counselor education. The process for collecting data involved three steps. The first step was to identify CACREP-accredited master’s programs at comprehensive universities that met the abovementioned criteria.

As a result of this search process, 157 colleges and universities were identified for potential study inclusion. At the second step, the websites of these colleges and universities were searched to identify counselor educators with the rank of either associate or full professor. In addition to the rank of at least associate professor, a minimum of 20 years must have passed since the counselor educator received their doctoral degree to be included in this study. At the end of this process, 162 counselor educators were eventually identified. For each identified counselor educator, the following information was recorded: (a) name of the counselor educator, (b) Carnegie Classification of their current university, (c) inferred binary gender based on name and any contextual information, (d) type of terminal degree (e.g., PhD, EdD), (e) academic discipline of terminal degree, and (h) date of doctoral degree. If any of this data was not available on a counseling program’s website, additional public resources were searched, such as university catalogs, Dissertations Abstracts International, Google, and LinkedIn. There were six counselor educators for whom a terminal degree date could not be identified; these counselor educators were removed from the sample, leaving a final sample size of 156.

Count of Journal Article Publications

To identify journal article publications, each counselor educator’s name was searched through three major electronic databases: PsycINFO, ERIC, and Academic Search Complete. The beginning date for each search was the year following a counselor educator’s terminal degree date and the end date of the search was 20 years later. A journal article publication was operationally defined as any authored publication in a peer-reviewed journal indexed in any of the three databases that involved theory, counseling practice, quantitative research, qualitative research, mixed method research, or published responses to other published works; for the purpose of this study, editor notes and book reviews were excluded. The number of journal article publications for each counselor educator over the first 20 years after degree completion was summed to represent journal article publication counts.

Results

Data Analysis Strategy

Prior to conducting any analyses, the dataset was screened for data entry errors, unusual values, and extreme outliers; none were identified. Prior to running the negative binomial regression analysis, the categorical predictor variables (inferred binary gender, faculty rank) were dummy coded. All screening procedures and subsequent analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS (Version 28).

To predict journal article publication counts, a negative binomial regression analysis was conducted because the criterion variable, journal article publications, represented a count variable that contained a large number of zero values and the variance of the distribution exhibited overdispersion (Fox, 2008). Power estimates for negative binomial regression models are less developed than those available for linear models. Nonetheless, traditional power estimates for general linear models (Cohen, 1988) and experimental estimates for generalized linear models (Doyle, 2009; Lyles et al., 2007) suggested that the negative binomial regression analysis likely had sufficient statistical power (> .80) to detect at least medium effect sizes. The following assumptions for negative binomial regression were examined: multicollinearity, residual plots, independence of residual errors, and the presence of any highly influential cases. No difficulties were identified.

Ideally, a time series analysis is recommended for identifying trends or changes in longitudinal data across time (Yaffee & McGee, 2000). However, it is commonly recommended that a time series analysis should be based on a minimum of 50 observation periods (e.g., Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019). Power estimates for time series analyses can become very complex, and in some cases, 100 to 250 observational periods may be needed to reliably detect trends or seasonal patterns in time series data (Yaffee & McGee, 2000). It would not be feasible to track even a minimum of 50 years of journal article publications for a sizeable sample of counselor educators. Furthermore, inferential statistics—and accompanying power analyses—are needed for making inferences from a sample to the larger population from which the sample was drawn. Aside from inaccuracies on department websites, the counselor educators in this study represent the entire population of counselor educators at master’s-only programs in comprehensive universities who received their doctoral degrees at least 20 years ago. As Garson (2019) pointed out, “having data on all the cases in the population of interest eliminates the need for a random sample and, indeed, for significance testing at all” (p. 25). Consequently, the longitudinal analysis of this data will be limited to the creation and visual analysis of sequence charts.

Characteristics of the Sample

Regarding inferred binary gender, 51.9% (n = 81) of these counselor educators appeared to identify as female, and 48.1% (n = 75) appeared to identify as male. Two-thirds (n = 104, 66.7%) held the rank of full professor, and 33.3% (n = 52) held the rank of associate professor. The years in which they earned their terminal degrees ranged from 1970 to 2000 (Mdn = 1995.00, M = 1992.70, SD = 6.48). The number of years after earning their terminal degrees ranged from 20 to 50 (Mdn = 25.00, M = 27.30, SD = 6.48). Their terminal degrees included PhDs (n = 118, 75.6%), EdDs (n = 31, 19.9%), PsyDs (n = 4, 2.6%), and other (n = 3, 1.9%). Slightly over half of these faculty members had terminal degrees in counseling/counselor education (n = 80, 51.3%), followed in frequency by counseling psychology, clinical psychology, or educational psychology (n = 47, 30.1%); education (n = 13, 8.3%); rehabilitation or rehabilitation psychology (n = 10, 6.4%); and other (n = 6, 3.8%). Almost two-thirds (n = 102, 65.4%) were faculty at public universities with the remainder (n = 54, 34.6%) being faculty at private universities. Regarding current Carnegie Classifications, over four-fifths were faculty at M1 institutions (n = 128, 82.1%), which was followed in frequency by M2 institutions (n = 20, 12.8%) and M3 institutions (n = 8, 5.1%).

Journal Article Publication Counts

At the end of the first 20 years after receiving their terminal degrees, these counselor educators had accrued a median of three (M = 5.26, SD = 6.92) journal article publications referenced in at least one of the three electronic databases. Notably, a fourth of the sample (n = 39, 25%) did not have any journal article publications indexed in any of the electronic databases. Expressed on an annual basis, the entire sample of counselor educators had accrued a median of 0.15 (M = 0.26, SD = 0.35) journal articles each year for the first 20 years after completing their terminal degrees.

Prediction of Publication Counts

Based on prior research in counselor education (e.g., Hatchett et al., 2020; Lambie et al., 2014; Newhart et al., 2020; Ramsey et al., 2002), the next set of analyses evaluated whether cumulative journal article publication counts could be predicted from faculty rank, inferred binary gender, and year of terminal degree. In fitting a negative binomial regression model to the data, the likelihood ratio chi-square statistic was statistically significant, indicating that the three combined variables were useful for predicting publication counts: χ2(3, N = 156) = 21.22, p < .001, McFadden R2 = .024. All three predictor variables made unique contributions to the prediction of journal article publication counts (see Table 1). The estimated number of publications for full professors was 1.73 times higher (95% CI [1.18, 2.53]; p = .005) than for associate professors. For reference, over the first 20 years since degree completion, associate professors had accrued an average of 3.31 (SD = 5.52) journal article publications compared to an average of 6.24 (SD = 7.36) journal article publications for full professors. The estimated number of publications for male counselor educators was 1.45 times higher (95% CI [1.02, 2.06]; p = .037) than for female counselor educators. For reference, male counselor educators had accrued a mean of 6.17 (SD = 7.89) journal article publications compared to a mean of 4.42 (SD = 5.81) for female counselor educators. Finally, with each 1-year increase in terminal degree date, the estimated number of cumulative publications increased by 4.1% (95% CI [1.01, 1.07]; p = .005).

Table 1

Prediction of Journal Article Publication Counts From Faculty Rank, Inferred Binary Gender, and Terminal Degree Date

________________________________________________________________________________

Predictors B SE Wald χ2 p

________________________________________________________________________________

Faculty Rank .55 .19 8.01 .005

Inferred Binary Gender .37 .18 4.36 .04

Year of Terminal Degree .04 .01 7.75 .005

________________________________________________________________________________

Longitudinal Analyses

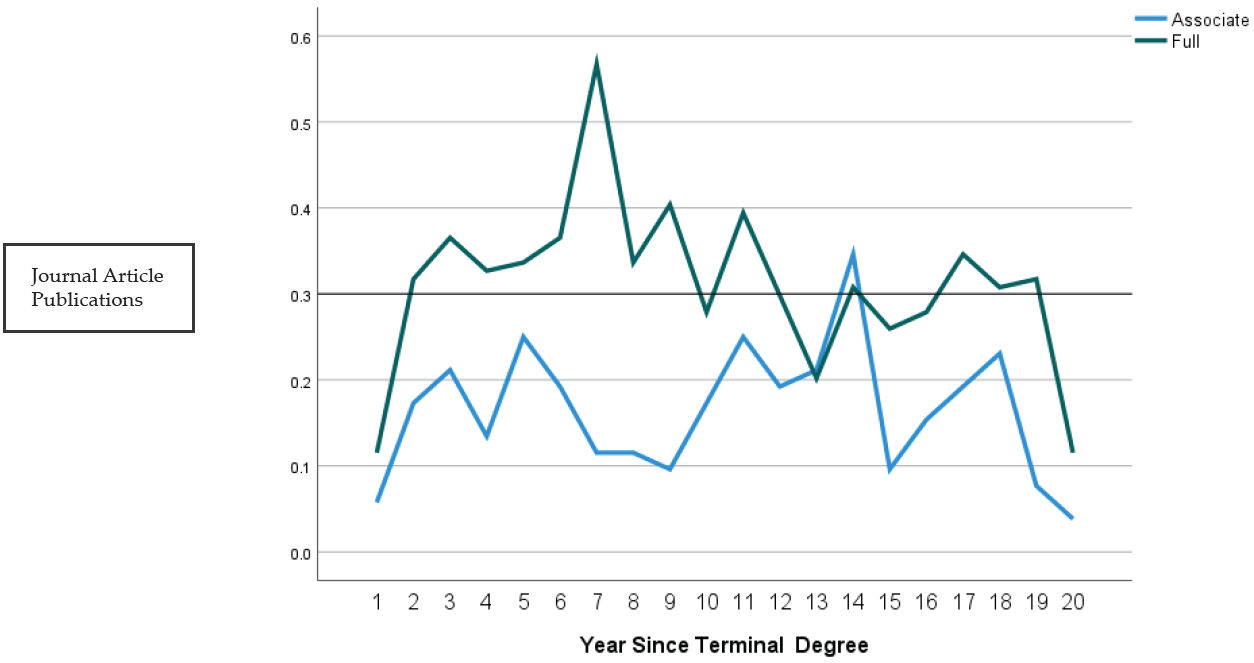

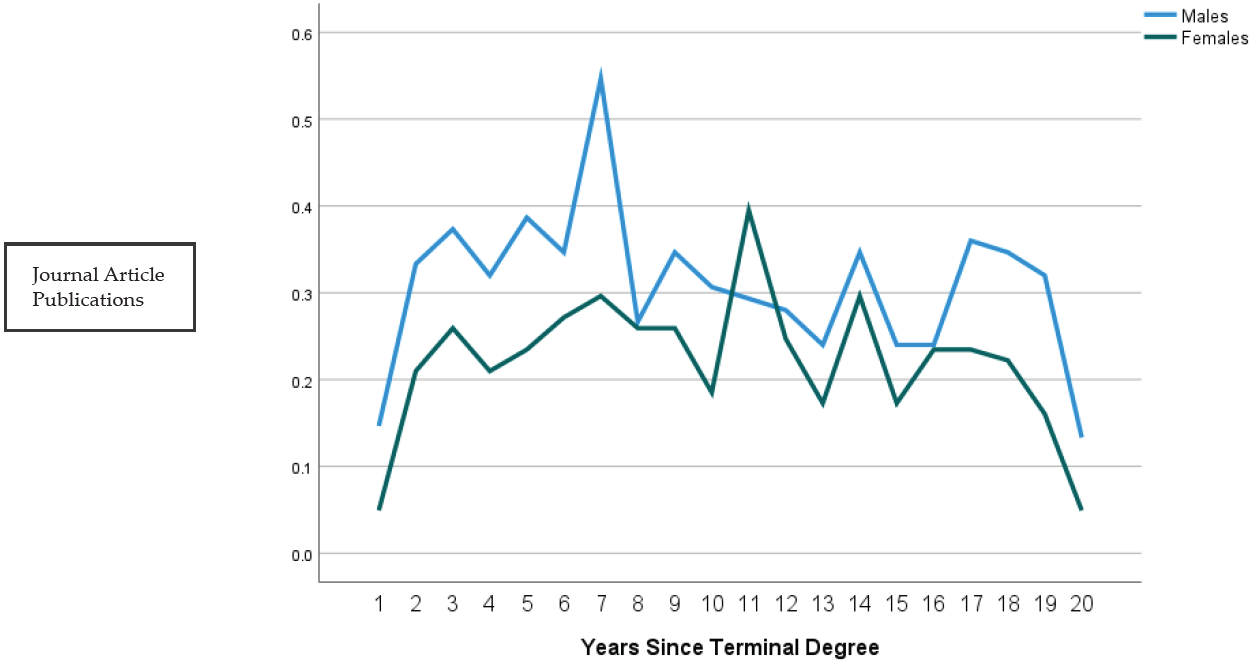

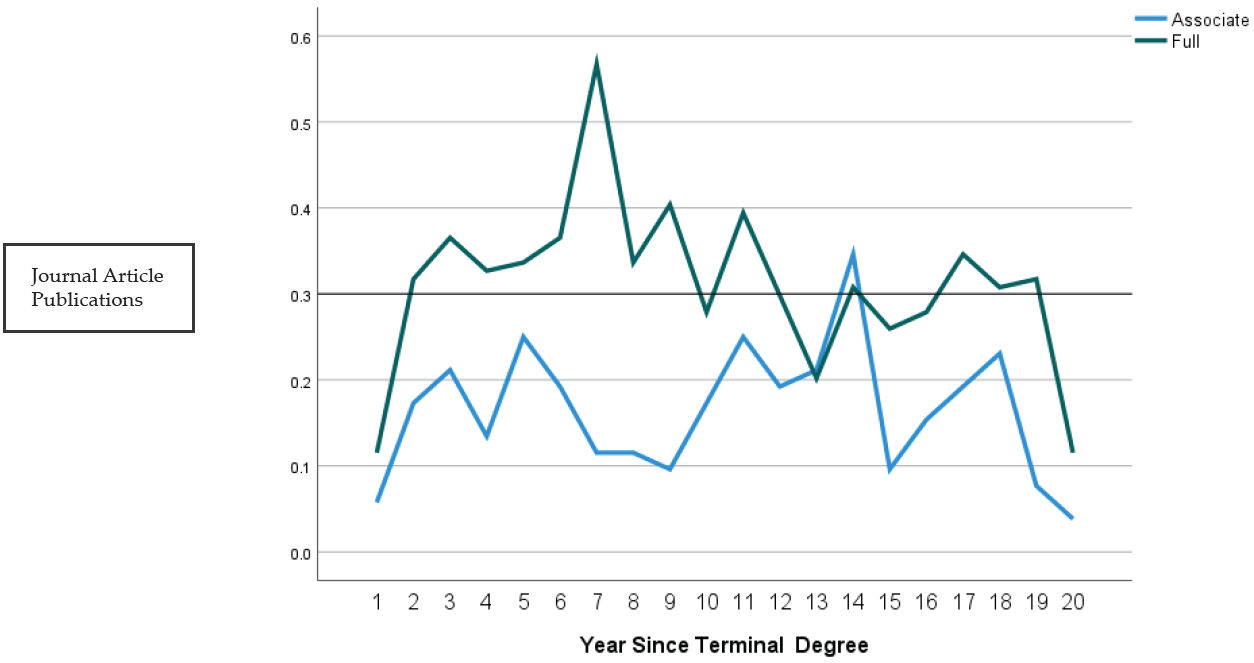

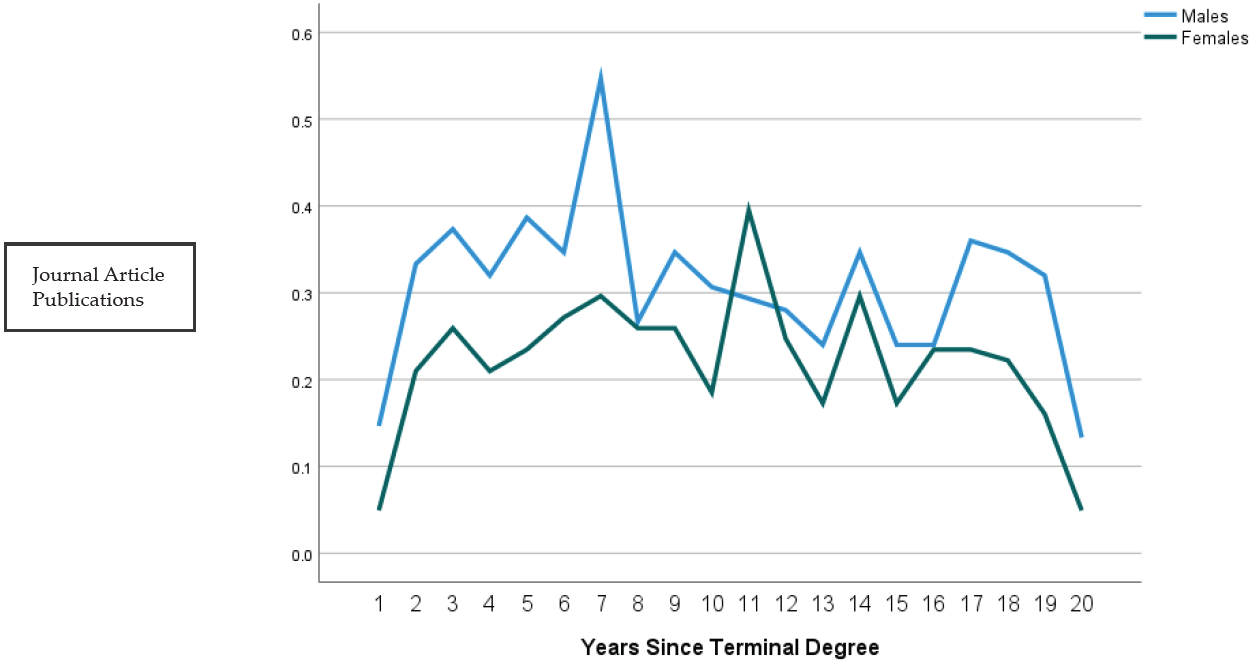

As reported previously, cumulative journal article publications varied as a function of both faculty rank and inferred binary gender. Because of this, two sequence charts were created to illuminate how journal article publication trajectories varied based on faculty rank and inferred binary gender. SPSS (Version 28) was used to create two sequence charts of the average number of journal article publications accrued each year for the first 20 years since degree completion. Figure 1 represents a sequence chart for journal article publications disaggregated by faculty rank. Figure 2 represents a sequence chart for journal article publications disaggregated by inferred binary gender.

Figure 1

Average Number of Journal Article Publications for Associate and Full Professors Over 20 Years After Degree Completion

Figure 2

Average Number of Journal Article Publications for Male and Female Counselor Educators Over 20 Years After Degree Completion

Discussion

The main objective of this study was to conduct a longitudinal analysis of the journal article publications of counselor educators at comprehensive universities for the first 20 years after receiving their doctoral degrees. A secondary objective was to evaluate how well these publication counts could be predicted from faculty rank, inferred binary gender, and year of terminal degree. Parallel to the results section, summary statistics will be discussed first, followed by the results of the regression analysis, and ending with the results of the longitudinal analyses.

Over the first 20 years since receiving their terminal degrees, the counselor educators in this sample had accrued a median of three (M = 5.26, SD = 6.62) journal article publications, which translates to a median of 0.15 (M = 0.26, SD = 0.35) journal articles published per year. Notably, a fourth (n = 39, 25%) of the sample did not have any journal article publications referenced in any of three major electronic databases. These findings are consistent with those of Hatchett et al. (2020), who investigated the journal article publications of this same population over a discrete 10-year period (2008–2017) using a similar methodology. They found that counselor educators at comprehensive universities had a median of 0.10 journal article publications each year, but a much higher proportion (46.4%) of their sample did not have any journal article publications referenced in any of the electronic databases. These differences may be the result of both the specific compositions of their samples and the timeframes for data collection. The current study examined the publication records of only associate and full professors, whereas Hatchett et al. (2020) examined the publication records of assistant, associate, and full professors of counselor education. Consistent with that expanded population, some of the counselor educators in the study by Hatchett et al. were just starting their careers and may not yet have attained many publications. There is also the possibility that some of the assistant professors in that study will be, or have been, turned down for promotion to associate professor because of inadequate scholarly productivity. Of course, it is not surprising that the current study, which examined a 20-year timeframe, uncovered a lower percentage of counselor educators without any journal article publications; after all, the counselor educators in the current study had double the time in which to accrue journal article publications.

Based on previous research in counselor education (Hatchett et al., 2020; Lambie et al., 2014; Newhart et al., 2020; Ramsey et al., 2002), this study also examined how well faculty rank, inferred binary gender, and year of terminal degree predicted journal article publication counts. Full professors had more journal article publications for the first 20 years after receiving their terminal degrees than those at the rank of associate professor. Not only would more publications be expected for a counselor educator at the rank of full professor, but other studies in counselor education have also found higher levels of scholarly productivity for full professors compared to associate professors (Hatchett et al., 2020; Ramsey et al., 2002). Although Lambie et al. (2014) found that associate professors had more journal article publications than full professors, their study included only counselor educators at doctoral-level programs and covered a discrete 6-year period of journal article publication counts. Thus, these two studies are not directly comparable. Several researchers have also found that male counselor educators attain more journal article publications than female counselor educators (Lambie et al., 2014; Newhart et al, 2020; Ramsey et al., 2002). Thus, the results from the current study are consistent with the majority of other research on this topic. Finally, in the current study, the date of terminal degree attainment had a minor impact on journal article publication counts. This is consistent with two other studies in the literature (Hatchett et al., 2020; Lambie et al., 2014). There are at least two plausible explanations for this finding. On the one hand, expectations for scholarly productivity have increased in recent years (Fairweather, 2005; Youn & Price, 2009); thus, it is not surprising that counselor educators who have attained their terminal degrees more recently have more journal article publications. From another perspective, Lambie et al. (2014) hypothesized that more recent graduates of counselor education programs may have stronger research skills than those who graduated earlier. Both explanations are speculative, so future research might better elucidate the role of time and training experiences on journal article publications.

The final objective of the study was to evaluate the extent to which journal article publication rates change over the course of counselor educators’ careers. The sequence charts presented in Figures 1 and 2 provide evidence that scholarly productivity is not invariant over the first 20 years since doctoral degree completion but tends to vary based on time, current academic rank, and inferred binary gender. There seems to be a relative peak around Year 7 for full professors and Year 14 for associate professors. The peak at Year 7 for full professors may be attributable to the typical timeframe for applying for tenure and promotion to associate professor; however, it is unclear why the associate professors exhibited a relative peak at Year 14. There also seems to be a peak around Year 7 for male counselor educators and Year 11 for female counselor educators. Again, the peak around Year 7 for male counselor educators is consistent with the typical timeframe for applying for tenure and promotion to associate professor. Though speculative, the delayed peak for female counselor educators may be the result of childbirth and early childcare responsibilities. Some research indicates that female faculty members plan childbirth around the academic calendar and tenure clock (e.g., Armenti, 2004), so perhaps a similar phenomenon occurred among the female counselor educators in this sample. More research is needed on how childbirth and childcare experiences impact the career decisions and scholarly productivity of female counselor educators (e.g., Trepal & Stinchfield, 2012). Finally, for the entire sample, there seems to be a relative decline in journal article publications near the end of the 20-year observational period. This lower level of scholarly productivity may reflect fewer institutional incentives to continue publishing, less interest in conducting original research, or a shift to other professional responsibilities, such as leadership positions on campus or in professional counseling associations.

Limitations

One clear limitation to the current study was the inability to apply a time series analysis to the data. As already mentioned, there were not enough observation periods to run a time series analysis with sufficient statistical power. In addition, the sequence charts were based on the average number of publications attained by these counselor educators on a yearly basis. The distribution of journal article publications for every observational unit was positively skewed, and the median number of publications for every observational unit was zero. Consequently, if the median number of publications each year had been plotted on the sequence charts, both graphs would have included two flat lines directly on the x-axis. Expressed differently, the typical counselor educator at a comprehensive university did not attain any journal article publications in a typical year. Thus, to some extent, the trends plotted in Figures 1 and 2 reflect only the most active researchers in this population.

It is also important to note that this study operationalized a very narrow definition of scholarly productivity: journal articles referenced in the PsycINFO, ERIC, or Academic Search Complete electronic databases. Though a highly reliable operational definition, and one used by other researchers (Barrio Minton et al., 2008; Hatchett et al., 2020; Lambie et al., 2014), this index certainly does not capture the full breadth of scholarly productivity. Counselor educators across all types of universities write book chapters and books, present at conferences, prepare reports, and secure external grant funding, among many other additional activities (e.g., Ramsey et al., 2002).

A final limitation of this study was the professional backgrounds of the counselor educators in this sample. Though all the counselor educators were faculty at CACREP-accredited programs, only about 50% had terminal degrees in counseling or counselor education. At the time of these counselor educators’ terminal degrees, CACREP did not stipulate that core faculty must have doctoral degrees in counselor education and supervision from CACREP-accredited programs. Even accounting for the grandfathering clause of 2013, a clear majority of the faculty in CACREP-accredited counseling programs now have doctoral degrees from CACREP-accredited counselor education and supervision programs (Hatchett, 2021). It is unknown whether this shift in the professional backgrounds of counselor education faculty will eventually impact the long-term trajectory of counselor educators at comprehensive universities.

Implications for Counselor Education

The results from the current study indicate that the typical counselor educator at a master’s-only counseling program at a comprehensive university will generate less than six journal article publications over the course of their career. Also, if these reported trends are stable across time, a significant minority will not attain any referenced journal article publications across their careers. These trends do not mean that counselor educators at comprehensive universities do not make meaningful contributions to the field of counseling in other ways, such as conference presentations, book chapters, grants, or evaluation reports (e.g., Ramsey et al., 2002). Also, as already mentioned, the electronic databases selected for this study and the study by Hatchett et al. (2020) do not capture all of the journals in which counselor educators publish. Nonetheless, it does reflect a relatively low level of original research published in peer-reviewed journals that is easily accessible through searching three popular electronic databases.

The results from this study—combined with the typical occupational outcomes of program graduates—should have implications for doctoral-level training in counselor education. As previously mentioned, all graduates of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs are required to acquire numerous research competencies that will equip them for making original and meaningful contributions to the counseling literature (CACREP, 2015). Yet, most graduates of these programs do not attain faculty positions in higher education, and among those who do, relatively few will be employed at research-intensive universities (e.g., Lawrence & Hatchett, 2022; Schweiger et al., 2012; Zimpfer, 1996). Furthermore, based on the distribution of CACREP programs across the Carnegie Classification System, program graduates who do secure faculty positions will be more likely to be employed at master’s-level universities than at institutions classified as R1 or R2.

It might be argued that the low rate of journal article publications produced by counselor educators at comprehensive universities is not problematic. Counselor educators at comprehensive universities spend proportionately more of their worktime on teaching and administrative tasks (Hatchett, 2021), and they often lack the institutional resources experienced by their colleagues at more research-intensive universities, such as access to research assistants (Henderson, 2011). Expecting counselor educators at comprehensive universities to do more research might be as fair as asking counselor educators at research-intensive universities to do more teaching and service (Hatchett et al., 2020). Yet, on the other hand, one should also consider what is being lost by the low levels of research found among many of the counselor educators at comprehensive universities. Many of these counselor educators are presumably not using the multitude of research competencies they developed during their doctoral-level training. The research training prescribed by CACREP is not just the means to a single end, a completed dissertation. One of the explicit training objectives of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs is to prepare program graduates to generate and disseminate new knowledge in the field of counseling (CACREP, 2015), an objective commonly discharged through publishing original research in peer-reviewed journal articles. The current study cannot resolve this conflict, but hopefully it will facilitate additional discussions on the value and role of research training in CACREP-accredited doctoral-level programs.

Recommendations for Future Research

One recommendation for future research, and one directly derived from the previous discussion, would be to investigate the extent to which graduates of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs use the skills and competencies acquired as part of their training. For example, researchers might investigate the extent to which program graduates use specific skills in teaching, research, grant work, clinical supervision, program evaluation, consultation, and clinical practice as part of their postgraduate occupations. The distributions of these actual work responsibilities could then be compared to the relative emphases of these competencies in doctoral-level training programs. Another recommendation for future research would be to replicate this study with counselor educators at universities with higher expectations of scholarly productivity, such as counselor educators at R1 or R2 universities, and those universities that offer CACREP-accredited doctoral degrees in counselor education, irrespective of Carnegie Classifications. Such research might identify trends and patterns in publication patterns for those counselor educators who are expected to produce and maintain higher levels of scholarly productivity over the entire course of their careers.

Conclusion

Consistent with the results of earlier research (Hatchett et al., 2020), the current study suggests that counselor educators at comprehensive universities—in general—publish minimal research in peer-reviewed journals. Furthermore, the journal article publications of these counselor educators exhibited a relative decline over the course of the first 20 years of the educators’ careers. These findings are somewhat in conflict with the accreditation standards delineated by CACREP and the objectives of doctoral-level training in counselor education. CACREP (2015) requires that all new core faculty have a doctoral degree in counselor education and supervision from accredited doctoral programs. These accredited doctoral programs stipulate that all program graduates attain numerous competencies in research and scholarship, irrespective of the graduates’ career plans. Yet, most graduates of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs do not attain faculty positions as counselor educators (Lawrence & Hatchett, 2022; Schweiger et al., 2012; Zimpfer, 1996), and for those who do, they are more likely to be employed at comprehensive universities at which scholarly productivity tends to be minimal than at more research-intensive universities at which high levels of scholarly productivity will be needed for promotion and tenure. Given these outcomes, counselor educators should revisit the nature of doctoral-level training and reevaluate the extent to which the curricula of CACREP-accredited programs prepare program graduates for the most common career pathways after graduation.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Armenti, C. (2004). May babies and posttenure babies: Maternal decisions of women professors. The Review of Higher Education, 27(2), 211–231. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2003.0046

Barrio Minton, C. A., Fernando, D. M., & Ray, D. C. (2008). Ten years of peer-reviewed articles in counselor education: Where, what, who? Counselor Education and Supervision, 48(2), 133–143.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2008.tb00068.x

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum.

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2015). 2016 CACREP standards.

http://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/2016-Standards-with-citations.pdf

Dill, D. D., & Morrison, J. L. (1985). EdD and PhD research training in the field of higher education: A survey and a proposal. The Review of Higher Education, 8(2), 169–186.

Doyle, S. R. (2009). Examples of computing power for zero-inflated and overdispersed count data. Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods, 8(2), 360–376. https://doi.org/10.22237/jmasm/1257033720

Fairweather, J. S. (2005). Beyond the rhetoric: Trends in the relative value of teaching and research in faculty salaries. The Journal of Higher Education, 76(4), 401–422. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2005.0027

Fox, J. (2008). Applied regression analysis and generalized linear models (2nd ed.). SAGE.

Garson, G. D. (2019). Multilevel modeling: Applications in STATA®, IBM® SPSS®, SAS®, R, & HLM™. SAGE.

Hatchett, G. T. (2020). Perceived tenure standards, scholarly productivity, and workloads of counselor educators at comprehensive universities. The Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 13(4).

https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/jcps/vol13/iss4/9

Hatchett, G. (2021). Tenure standards, scholarly productivity, and workloads of counselor educators at doctoral and master’s-only counseling programs. The Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 14(4).

https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/jcps/vol14/iss4/4

Hatchett, G. T., Sylvestro, H. M., & Coaston, S. C. (2020). Publication patterns of counselor educators at comprehensive universities. Counselor Education and Supervision, 59(1), 32–45.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12164

Henderson, B. B. (2011). Publishing patterns at state comprehensive universities: The changing nature of faculty work and the quest for status. The Journal of the Professoriate, 5(2), 35–66. http://caarpweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/5-2_Henderson_p.35.pdf

Lambie, G. W., Ascher, D. L., Sivo, S. A., & Hayes, B. G. (2014). Counselor education doctoral program faculty members’ refereed article publications. Journal of Counseling & Development, 92(3), 338–346.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00161.x

Lawrence, C., & Hatchett, G. T. (2022). Academic employment prospects for counselor education doctoral candidates [Manuscript submitted for publication]. Northern Kentucky University, School of Kinesiology, Counseling, and Rehabilitative Sciences.

Lyles, R. H., Lin, H.-M., & Williamson, J. M. (2007). A practical approach to computing power for generalized linear models with nominal, count, or ordinal responses. Statistics in Medicine, 26(7), 1632–1648.

https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.2617

Newhart, S., Mullen, P. R., Blount, A. J., & Hagedorn, W. B. (2020). Factors influencing publication rates among counselor educators. Teaching and Supervision in Counseling, 2(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.7290/tsc020105

Ramsey, M., Cavallaro, M., Kiselica, M., & Zila, L. (2002). Scholarly productivity redefined in counselor education. Counselor Education and Supervision, 42(1), 40–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2002.tb01302.x

Schweiger, W. K., Henderson, D. A., McCaskill, K., Clawson, T. W., & Collins, D. R. (2012). Counselor preparation: Programs, faculty, trends (13th ed.). Routledge.

Snow, W. H., & Field, T. A. (2020). Introduction to the special issue on doctoral counselor education. The Professional Counselor, 10(4), 406–413. https://doi.org/10.15241/whs.10.4.406

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2019). Using multivariate statistics (7th ed.). Pearson.

Trepal, H. C., & Stinchfield, T. A. (2012). Experiences of motherhood in counselor education. Counselor Education and Supervision, 51(2), 112–126. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2012.00008.x

Yaffee, R., & McGee, M. (2000). Introduction to time series analysis and forecasting with applications of SAS and SPSS. Academic Press.

Youn, T. I. K., & Price, T. M. (2009). Learning from the experience of others: The evolution of faculty tenure and promotion rules in comprehensive institutions. The Journal of Higher Education, 80(2), 204–237.

Zimpfer, D. G. (1996). Five-year follow-up of doctoral graduates in counseling. Counselor Education and Supervision, 35(3), 218–229. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.1996.tb00225.x

Gregory T. Hatchett, PhD, NCC, LPCC-S, is a professor at Northern Kentucky University. Correspondence may be addressed to Gregory T. Hatchett, MEP 211, Highland Heights, KY 41099, hatchettg@nku.edu.

Jul 20, 2016 | Article, Volume 6 - Issue 2

Dee C. Ray, David D. Huffman, David D. Christian, Brittany J. Wilson

The vast majority of graduate students in the social sciences, especially in mental health fields, are females (Crothers et al., 2010; Healey & Hays, 2012). In a recent report on counseling programs, an average of 76% of students admitted and graduated yearly from entry-level counseling programs were women (Schweiger, Henderson, McCaskill, Clawson, & Collins, 2012). Although counseling is one field that attracts mostly female graduate level students, a historical review indicates that males made up approximately 80% of counselor education faculties in the 1980s (Anderson & Rawlins, 1985). In recent years, as the number of females who seek doctoral degrees in counseling has increased, so has the number of female counselor educators, correlating to fewer males entering the field of counselor education. Currently, the average number of males admitted and graduated yearly from doctoral-level counseling programs has been reported at a meager 25% (Schweiger et al., 2012). As counselor educators strive to build best practices for working with diverse populations, it seems relevant to explore the experiences of male counselor educators as well as suggest practices that improve conditions for male counselor education faculty.

In the preparation of counselors, counselor educators are encouraged to build relationships with students that lead to greater self-awareness, personal development and interpersonal learning, which inform their work as counselors. Literature cites the importance of the relationships between counseling faculty and students as “paramount” (Dollarhide & Granello, 2012, p. 290), suggesting that it “stands out above all other factors” (McAuliffe, 2011, p. 32) in the education of adults. It seems reasonable to assume that if counselor educators espouse the importance of the relationship between client and counselor, they extend this value to their students, building relationships that facilitate learning. Thus, a belief that the relationship between teacher and student leads to mutual support and growth comprises the hallmark of humanistic education (Dollarhide & Granello, 2012).

Although the American Counseling Association (ACA) Code of Ethics (2014) asserted that counselor educators are restricted from sexual or romantic relationships with students, universities and counselor education programs typically do not clearly articulate boundaries when approaching the multiple roles adopted by faculty members (Owen & Zwahr-Castro, 2007). In the absence of guidelines and open discussion regarding faculty–student relationships, legal concerns can permeate the university environment. Sexual harassment suits have increased, and many universities have responded by going beyond sexual harassment policies and adding additional policies that restrict sexual or romantic consensual relationships between faculty and students (Bartlett, 2002; Kiley, 2011). Male faculty members seem especially affected by the legal environment and Nicks (1996) reported males had significantly higher concerns than females regarding unjust accusations of harassing a student. In the current environment of legality and ambiguous ethical guidelines, Kress and Dixon (2007) cautioned that counselor educators might choose to distance themselves from students to avoid the appearance of impropriety or placing themselves in complex ethical situations. However, there is a dearth of literature regarding issues of relationship dynamics based on sexuality and gender in academia over the last 20 years.

Further complicating the issue of faculty–student relationships is that female professors and students are more likely to perceive complex relationship issues as unethical when compared to their male counterparts. In a comparison between female and male counselor educators and counselor education students, Bowman, Hatley, and Bowman (1995) found that females were significantly more likely to rate activities outside the traditional student–teacher relationship as unethical. This finding has been supported in multiple studies regarding undergraduate students (Ei & Bowen, 2002; Oldenburg, 2005; Owen & Zwahr-Castro, 2007). Female undergraduate students were more likely to rate a relationship scenario as unethical when the professor was identified as a male as compared to scenarios with female professors (Oldenburg, 2005) and more likely to be negative than males about questionable scenarios such as sexual relationships, doing favors for a professor, and doing things alone with an instructor (Ei & Bowen, 2002). Owen and Zwahr-Castro (2007) found that female undergraduate students judged approximately one-third of faculty–student interaction scenarios as significantly more inappropriate than male students, identifying nonacademic-related interaction that occurred off campus as most inappropriate. Although not specifically explored, the tendency of females to find behaviors unethical when compared to the perceptions of males has been attributed in the literature to sensitivity of women to power differentials and potential for exploitation based on cultural experience (Ei & Bowen, 2002; Owen & Zwahr-Castro, 2007). In the context of current ratios in counselor education of a majority number of female faculty to a minority number of male graduate students, it is difficult to ascertain the perception of power dynamics based on gender.

The changing context of counselor education may present unique challenges for male faculty to navigate with little guidance. A review of the literature highlights a complex environment where male counselor educators engage in faculty–student relationships within a context of power differences and potential legal complications. The current study was conceived in a doctoral level clinical course in which male and female doctoral students processed their teaching experiences with master’s students. During the discussion, male doctoral students serving as instructors shared experiences regarding relationships with their students that appeared uniquely different from experiences shared by female colleagues. Concerns emerged regarding practices of male counselor educators when entering a female-prevalent field as a person in a position of power. As a result, we proposed that the following factors might influence the interactions of male counselor educators on a daily basis in their roles with students: majority of female graduate students, decreasing number of male faculty, increases in legal action, ambiguity of ethical guidelines, possible attraction between professors and students, and a contextual field that values human relationships. The purpose of this study was to discover attitudes and practices of male counselor educators regarding faculty-student relationships. Our research questions included: (a) what are the practices and attitudes of male counselor educators related to relationships with students and colleagues? and (b) what specific practices do male counselor educators employ to maintain boundaries with students?

Methodology

Participants and Data Collection

Using Schweiger et al.’s (2012) compilation of counseling program information, a member of the research team identified names typically attributed to males among listed faculty names, resulting in the identification of 330 males within the United States. The research team then matched the names with e-mails on university Web sites. An initial recruitment e-mail was sent to the identified sample asking for participation. Following the initial recruitment e-mail, 41 of the identified original sample responded as ineligible (22 contact e-mails were immediately returned as unavailable; 6 identified as female; and 13 identified as no longer working as a counselor educator or having never worked as a counselor educator). This resulted in a potential sample of 289. Two more e-mails were sent as reminders regarding participation. The final sample consisted of 163 male counselor educators who completed the survey, resulting in a response rate of 56%.

A summary of demographic characteristics of the 163 male counselor educators who completed the survey is presented in Table 1. In this sample, male counselor educators were mostly White, non-Hispanic (n=125). African American (n=14) and Hispanic (n=11) males also were represented, but only in small numbers, and Asian males (n=4) were few. Most of the sample identified as married/partnered (87%) and heterosexual (89%), with gay or bisexual males represented by approximately 10% of participants. The sample was more diverse in areas of age, rank, child status, and years as counselor educators.

Survey Development

We developed our survey in two phases. The research team brainstormed issues that emerged during discussion, such as the possible attitudes of male counselor educators, including feeling isolated or unsupported due to fewer numbers of male colleagues, or practices that might emerge in working with students of the opposite gender with the intent of ensuring a sense of safety. Based on discussion and an extensive literature review, the research team created a list of quantitative items surveying demographics, attitudes and practices of male counselor educators. We distributed the survey to a pilot group of six male counselor educators who represented diversity in age, experience, ethnicity and sexual orientation. The pilot participants reviewed each question and commented on its usefulness, acceptability and clarity. Based on pilot feedback, the research team modified the survey to include 22 demographic questions, 32 attitude and practice questions, and four open-ended questions. The survey was formatted for the Survey Research Suite (Qualtrics) and final quantitative data was transferred into SPSS for analysis.

Demographic questions included items regarding personal, family and program characteristics of the faculty members, and questions regarding the faculty members’ professional designations and teaching assignments. Attitude items (Cronbach’s α = .66) consisted of questions related to the impact of being male on both collegial and student relationships. Practice items (Cronbach’s α = .64) consisted of questions related to the participant’s actual practices in relating to students (e.g., private meetings, lunch/dinner, after class). For the full scale, Cronbach’s α was calculated at .70. Four open-ended questions addressed ethical challenges, thoughts related to being male, ways the counselor educator might act differently, and strategies used to avoid complications with students.

Table 1

Demographic Characteristics of Male Counselor Educator Participants

|

Variable

|

N

|

%

|

M

|

SD

|

Mdn

|

Range

|

| Age |

155

|

|

51.61

|

11.08

|

53

|

27–76

|

| Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| African American |

14

|

8.6

|

|

|

|

|

| Asian |

4

|

2.5

|

|

|

|

|

| White, Non-Hispanic |

125

|

76.7

|

|

|

|

|

| White, Hispanic |

11

|

6.7

|

|

|

|

|

| Self-Identified as Other |

8

|

4.9

|

|

|

|

|

| Relationship Status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Single |

14

|

8.6

|

|

|

|

|

| Married/Partnered |

142

|

87.1

|

|

|

|

|

| Divorced/Separated |

5

|

3.1

|

|

|

|

|

| Widowed |

1

|

.6

|

|

|

|

|

| Sexual Identity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Gay |

13

|

8.0

|

|

|

|

|

| Heterosexual |

145

|

89.0

|

|

|

|

|

| Bisexual |

3

|

1.8

|

|

|

|

|

| Status Regarding Children |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No Children |

30

|

18.4

|

|

|

|

|

| Adult Children |

74

|

45.4

|

|

|

|

|

| Minor Children in Home |

55

|

33.7

|

|

|

|

|

| Minor Children Part Home |

1

|

.6

|

|

|

|

|

| Minor Children Not in Home |

2

|

1.2

|

|

|

|

|

| Years As Counselor Educator |

161

|

|

15.07

|

10.85

|

12

|

1–45

|

| Faculty Rank |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Assistant |

38

|

23.3

|

|

|

|

|

| Associate |

50

|

30.7

|

|

|

|

|

| Full |

58

|

35.6

|

|

|

|

|

| Lecturer/Interim |

4

|

2.5

|

|

|

|

|

| Other |

13

|

8.0

|

|

|

|

|

| Total Number of Male Faculty |

156

|

|

4.04

|

1.81

|

4

|

1–10

|

| Total Number of Female Faculty |

155

|

|

4.27

|

2.27

|

4

|

0–13

|

| Estimated % of Male Students |

163

|

|

18.21

|

11.24

|

16

|

0–78

|

| Estimated % of Female Students |

162

|

|

77.66

|

18.55

|

80

|

0–99

|

The first three open-ended questions were used for qualitative analysis and the final question was used to create a list of strategies employed by male counselor educators to aid in their student relationships.

Analysis and Results

The research team used a parallel mixed-methods design (Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2009) to explore the experiences of male counselor educators. We utilized qualitative thematic analysis for data generated from three open-ended questions and optional comments following each quantitative survey question and quantitative statistical analysis for multiple-choice survey questions. By conducting independent quantitative and qualitative analyses in a parallel simultaneous nature, we allowed the separate analyses to inform one another and provide a more integrated understanding of the data (Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2009). Due to overlap in analysis and results consequential from a mixed-methods approach, we chose to present analyses and results categorized by method (qualitative and quantitative) in the following section.

Qualitative Analyses

Responses to the three open-ended questions and optional comments were analyzed from a perspective of transcendental phenomenology to explore the lived experiences of participants (Creswell, 2007; Moustakas, 1994). Within this qualitative tradition, we worked to bracket or set aside our own preconceptions about the phenomenon as much as possible to remain focused on the views of participants (Moerer-Urdahl & Creswell, 2004; Moustakas, 1994). The research team, consisting of two male doctoral students and one female tenured faculty member, discussed our student–teacher relationship experiences regarding gender and power differences. Through reflection and discussion, we developed greater awareness of how our experiences have influenced our views of being and working with male counselor educators. Team discussion allowed us to understand and bracket our positions in the development of data collection and analysis methods.

Because the experiences of male counselor educators have received little attention in literature and research, a phenomenological approach allowed for understanding to emerge from participants’ written reports as data was broken down into smaller units of meaning and reconstructed into broader themes that were clearly defined (Creswell, 2007; Giorgi, 1985). Following data collection, we independently coded responses to three open-ended questions, a smaller portion of the data, to identify initial concepts. Next, we met to review and compare our concepts. Silverman and Marvasti (2008) identified the appropriate use of smaller portions of data to establish preliminary categories. We discussed each unit of meaning in the text that was relevant to the focus of study (Giorgi, 1985), compared each concept to previous statements and discovered an initial list of broader themes suggesting common experiences among participants (Creswell, 2007). The research team clarified category definitions by comparing data units within each category for similarities and differences. Responses to optional comments sections in the survey were reviewed for inclusion in the text. Comments that offered information beyond the scope of the survey question referenced were included in the text for qualitative analysis. Then individual team members independently examined the entire text and coded each unit of meaning under the appropriately perceived category. Finally, we met as a group to develop consensus on final categories and to assign textural excerpts to appropriate themes. As suggested by Potrata (2010), research team members focused on exploring potential differences in coding rather than focusing on consistency when coming to consensus in order to illuminate complexities of the male counselor educator experience. Frequencies were tabulated to represent the magnitude of each category within the sample, and verbatim illustrative quotes were selected to clarify the meaning of each category. Saldaña (2013) suggested that magnitude coding adds supplemental texture to provide richer results in qualitative analysis.

Qualitative Results

In order to address our first research question regarding practices and attitudes of male counselor educators, participants were asked to respond to three open-ended questions to address their experiences and practices as male counselor educators. Seventy-one responses were recorded for the first question, “What ethical challenges, if any, are related to being male in counselor education?” One hundred responses were recorded for the second question, “What are your thoughts related to being male in counselor education?” Ninety-six responses were recorded for the third question, “What are the ways you act differently in student relationships because you are male?” We also coded additional comments of significance that followed each survey item. In all, qualitative analysis included the coding of 359 answers of varying lengths. During qualitative analysis, the research team discovered that participants’ answers appeared to be addressing similar themes across all questions. Hence, all answers were collapsed into one analysis.

The research team identified 10 distinct themes expressed by participants regarding the experiences of being a male counselor educator. We identified “modify behavior” as the most predominant theme, magnified by frequency (32%). This theme included intentional changes in action or interpersonal expression related to being male in professional relationships. Another major theme, “no difference” (frequency 23%) included beliefs and experiences that no unique relationship challenges exist in counselor education related to being male. Expressions of feeling “isolated or lonely” (frequency 11%) described participant experiences of feeling a lack of support as well as awareness of being a minority in the profession. Responses regarding “sexual attraction” (frequency 11%) involved experiences of sexual attraction in professional relationships. A theme of “perception of impropriety” (frequency 10%) included attention to the perception of others regarding appropriate behavior. Expressions of “prejudice or discrimination” (frequency 9.5%) involved experiences of negative beliefs or actions of others related to one’s gender. Additionally, qualitative data revealed themes related to participants’ “awareness” of professional relationships, “awareness of power difference” in relationships, the importance of a “caring or safe environment,” and “ethnicity or orientation” as part of one’s identity as a male counselor educator. A comprehensive presentation of all themes is included in Table 2.

Our second research question regarding specific practices of male counselor educators was addressed through our fourth open-ended survey question, which indicated participants cited over 40 different strategies they used to structure their relationships with students. In general faculty–student interactions, respondents indicated that they did not meet alone with students; only met with students on campus; interacted in groups when others were present; avoided jokes, conversations or language that could be perceived as too friendly; referred to family/significant others in class and conversation; avoided sharing too much personal information; made no physical contact; and avoided being overtly interested in students’ relationship issues. When meeting with students, respondents reported that they kept their doors open, structured meetings with an agenda, met in classrooms, ensured others were around, and avoided engaging in counseling with students. Participants also indicated that they consulted with colleagues regarding student relationships, had colleagues present for potentially problematic student interactions, addressed student relationship issues as soon as they arose, notified department chairs of any concerns and documented interactions. On a personal level, participants reported that they focused on having a balanced personal life, increased self-awareness of interactions, reminded self of boundaries, and engaged in honest and transparent interactions.

Quantitative Analyses

We used results from qualitative analysis to inform decision making regarding variables of interest for quantitative analysis. Due to the extensive data resultant from the 32-question survey of practices and attitudes and need for manuscript brevity, we narrowed survey data results to the survey items that matched qualitative theme results. We chose to explore one survey item per qualitative theme that appeared to closely match the qualitative analysis. Following final coding discussion, the research team identified five attitude and practice questions from the survey that appeared to be related to content evolving from the qualitative analysis. The qualitative theme of modifying behavior appeared most closely linked to the survey item, “I interact differently with female students than male students.” The theme represented by some respondents, that there were no differences related to being male, most closely aligned with the item, “I have unique ethical challenges related to being male in counselor education.” The item linked to the qualitative theme of avoiding the appearance of impropriety, “I structure my individual interaction with students to avoid the appearance of impropriety,” was further explored. The qualitative themes of isolation and discrimination were matched to two items: “I feel isolated in my faculty because I am male,” and “I feel discriminated against by faculty members because I am male.” Although most respondents did not agree with these final two statements, we chose to explore them further due to the distinct voices of some respondents related to ethnicity and sexual orientation within the data.

Table 2

Themes Related to Male Counselor Educators’ Experiences

| Theme |

Definition

|

Freq.

|

Responses

|

Sample Statements

|

| Modify Behavior |

Intentional changes in action or interpersonal expression related to being male |

32%

|

115

|

“. . . crucial to make sure distinct boundaries are established”“. . . have to focus on being appropriately relational”“must balance being supportive with providing clear boundaries” |

| NoDifference |

No unique challenges in counselor education related to being male |

23%

|

82

|

“No specific challenges related to my gender”“Ethics are ethics, male or female”“How I act has little to do with being male” |

| Awareness |

Indicating awareness or self-awareness regarding professional relationships |

13%

|

47

|

“. . . we need to be very aware of situations and interactions with female students”“Know one’s self”“I am now more aware of how I interact” |

| IsolatedorLonely |

Experiencing lack of support and awareness of being a minority in profession |

11%

|

39

|

“I feel a bit like an endangered species”“There are simply some things I can only talk with other men about”“I recognize males are a minority in the field” |

| Sexual Attraction |

Experiences of sexual attraction in professional relationships |

11%

|

38

|

“Dealing with feelings of attraction with students and colleagues”“I am attracted to female students but do not act on it”“I have to refocus my thoughts if I feel an attraction to a student or colleague” |

| Perception of Impropriety |

Attention to the perception of others regarding appropriate behavior |

10%

|

37

|

“. . . don’t want to give the impression of being unethical”“Avoiding any appearance of misconduct”“. . . vigilant in protecting myself from false accusations” |

| Awareness of Power Difference |

Awareness of the impact of privilege and power in relationships |

10%

|

35

|

“Being aware of my male privilege and not abusing it”“I can be male without being dominating”“I do see the same gender politics and gender roles in my profession as I see in society…” |

| PrejudiceorDiscrimination |

Experiences of negative or devaluing beliefs or actions of others related to being male |

9.5%

|

34

|

“tendency to view males as the victimizer”“. . . uniquely male issues that could arise in counseling situations are downplayed”“I sometimes experience sexism against men in the comments of my female colleagues” |

| Caringor Safe Environment |

Intention to provide support and safety to students |

6%

|

21

|

“We want to provide a caring environment”“I want students to feel comfortable around me.”“. . . do not want any female to feel anxious” |

| Ethnicityor Orientation as Part of Identity |

Influences of ethnicity and sexual identity upon male professional experiences |

4%

|

15

|

“Being a male and an ethnic minority is challenging and often lonely”“. . . being Black and male is more of a challenge than being male alone”“I feel isolated not because I am male but because I am a gay male” |

Note: Frequency = Number of participants who shared theme-related statements

Quantitative Results

Descriptive results for the five survey items are presented in Table 3. In order to explore relationships between survey items of interest, we employed Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient analyses on the five variables. There were statistically significant positive correlations between perception of unique ethical challenges and the four other variables: feeling isolated

(r = .290, n = 149, p < .001); interacting differently with female students (r = .317, n = 147, p < .001); structuring interactions to avoid appearance of impropriety (r = .190, n = 148, p = .021); and feeling discriminated against (r = .217, n = 150, p = .008). The more a male counselor educator felt there were unique ethical challenges related to being male, the more likely he was to feel isolated and discriminated against, structure interactions with students to avoid the appearance of impropriety, and interact differently with females than males. Additionally, there was a statistically significant positive correlation between feeling isolated and feeling discriminated against (r = .371, n = 149, p < .001). The more isolated a male counselor educator felt, the more likely he was to feel discriminated.

Table 3

Survey Items Related to Relationships for Male Counselor Educators

|

|

|

|

Percent of Responses

|

|

Survey Item

|

N

|

|

Σ

|

SD

1

|

D

2

|

N

3

|

A

4

|

SA

5

|

| I feel isolated in my faculty because I am male. |

149

|

1.89

|

.94

|

36.8

|

36.8

|

11.7

|

5.5

|

1.2

|

| I interact differently with female students than male students. |

147

|

2.90

|

1.02

|

6.7

|

29.4

|

21.5

|

30.7

|

1.8

|

| I structure my individual interactions with students to avoid the appearance of impropriety. |

148

|

3.76

|

.92

|

1.8

|

9.2

|

13.5

|

50.9

|

15.3

|

| I have unique ethical challenges related to being male in counselor education. |

150

|

2.79

|

1.03

|

9.2

|

30.7

|

23.9

|

26.4

|

1.8

|

| I feel discriminated against by faculty members because I am male. |

150

|

2.05

|

1.06

|

31.9

|

39.9

|

6.1

|

12.3

|

1.8

|

Note: SD=Strongly Disagree, D=Disagree, N=Neutral, A=Agree, SA=Strongly Agree

We further explored ethnicity and sexual orientation in relationship to the dependent variables of isolation and discrimination based on qualitative findings that indicated these characteristics impact the views of male counselor educators. We conducted four separate one-way between-groups analyses of variance to explore the impact of ethnicity and gender on isolation and discrimination. There was a statistically significant difference in ethnicity for isolation, F(4, 144) = 5.78, p < .001, η2 = .14. Means for ethnicity included Asian x̅ = 2.0; African American x̅ = 1.71; White/Non-Hispanic x̅ = 1.84; White/Hispanic x̅ = 1.64; Self-Identified as Other x̅ = 3.43. There was a statistically significant difference in ethnicity for discrimination, F(4, 144) = 5.25, p = .001, η2 = .13. Means for ethnicity included Asian x̅ = 2.0; African American x̅ = 2.23; White/Non-Hispanic x̅ = 1.94; White/Hispanic x̅ = 1.91; Self-Identified as Other x̅ = 3.71. There was a statistically significant difference in sexual orientation for isolation, F(2, 145) = 3.81, p = .024, η2 = .05. Means for sexual orientation included Gay x̅ = 2.58; Heterosexual x̅ = 1.83; Bisexual x̅ = 1.67. There was no statistically significant difference in sexual orientation for discrimination, F(2, 145) = .70, p = .50, η2 = .01.

Discussion

The sample in this study reasonably represents the current population of male counselor educators in CACREP-accredited programs. Although the sample reported equivalent numbers between male and female faculty, they also reported a disproportionate number of female students (78%) to male students (18%), as indicated in previous literature (Schweiger et al., 2012). The sizeable response rate to this survey, as well as its representativeness, lends credibility to findings.

Themes and Characteristics Related to Being a Male in Counselor Education

Qualitative analyses indicated that participants expressed diversity of attitudes and practices regarding the impact of being male upon professional relationships. The most predominant theme, “modify behavior,” indicated that being male influenced choices made by male counselor educators in their interactions with students. Conversely, the second dominant theme, “no difference,” indicated that some counselor educators do not feel that there is any difference in interactions with students or colleagues related to being male. A lack of consensus existed among male counselor educators regarding the influence of being male upon their professional relationships.

When male counselor educators acknowledged there were differences related to being a male in the field, qualitative analysis revealed additional themes related to isolation, discrimination, fear of appearing inappropriate, interacting differently with females than males and need for awareness. We wanted to explore characteristics related to these feelings, which prompted the correlational analyses.

Quantitative and qualitative analyses indicated that the appearance of impropriety was of considerable concern for male counselor educators. A majority of participants agreed or strongly agreed that they structured their interactions to avoid appearance of impropriety. Results revealed a statistically significant positive relationship between expressing a perception of unique ethical challenges for males and structuring interactions to avoid appearance of impropriety. Participants who perceived unique challenges as males also tended to take steps to avoid appearing inappropriate in their professional relationships. This finding supports qualitative themes of male counselor educators’ concerns regarding the appearance of impropriety and fear of the cultural myth of the lecherous professor (Bellas & Gossett, 2001).

Sexual attraction emerged as a relevant issue through qualitative analyses. A vast majority of respondents reported that they had experienced being attracted to a student, with frequency of feelings ranging from rare to a regular occurrence. Also, a majority of the sample reported experiencing a student being attracted to them. These results suggest that sexual attraction was experienced as a common phenomenon in male teacher–student relationships. However, participants often described their feelings of attraction as natural reactions that posed no threat if not acted upon.

When addressing the influence of student gender upon their behavior with students, male counselor educators reported diverse perspectives. Participants were asked if they interacted differently with female students than male students. Responses were about evenly distributed from “disagree” to “agree.” The variance in responses may reflect the larger disagreement among participants regarding the influence of gender upon professional relationships. The qualitative themes of “modify behavior” and “no difference” may provide context for understanding diverse results regarding this question. Correlational analysis revealed that the more a participant perceived unique challenges as a male counselor educator, the more he reported interacting differently with female students compared to male students.

Some participants also reported experiencing isolation related to being a male counselor educator. Qualitative data revealed unique experiences of isolation related to ethnicity and sexual orientation. Although there were a small number of participants who identified as gay, bisexual, African American, Latino, Asian, or other ethnicity, we chose to conduct quantitative analysis to further explore their voices, which were clearly articulated as unique in qualitative analyses. Further quantitative analysis indicated that participants who self-identified as “other” for ethnicity were more likely to feel isolated in comparison with other ethnicities. Likewise, gay male counselor educators also were more likely to feel isolated in the profession. However, gay males did not report higher levels of feeling discriminated against as compared to heterosexual males. Previous research indicates gay males may experience isolation related to not being out to co-workers, often motivated by fear of discrimination (Wright, Colgan, Creegany, & McKearney, 2006). Another possible interpretation could be that gay male counselor educators feel isolated due to interacting with fewer colleagues who are similar to them, but who they experience as accepting or non-discriminatory.

Linked to isolation, we also asked male counselor educators if they had faculty colleagues with whom they could discuss challenges. This point seemed especially salient due to qualitative results indicating male counselor educators rely on consultation as one intervention for dealing with student relationship issues. A majority of respondents agreed or strongly agreed to having a colleague on their faculty with whom they could discuss male-related issues. Qualitative and quantitative analyses identified ethnicity as an important contributor to the experiences of male counselor educators. Qualitative data included a small but consistent voice of African American male counselor educators who expressed increased isolation due to a combination of ethnicity and gender. Quantitative analysis also indicated that participants who identified as African American reported more frequent experiences of discrimination in their professional environment. These findings coincide with research indicating that African American males experience prejudice and discrimination in higher education due to stereotype images of African American males as underachieving, disengaged and threatening (Harper, 2009). Brooks and Steen (2010) discussed concerns related to the lack of African American male counselor educators and the obstacles they face in the academic setting. Participants who self-identified as “other” on ethnicity also showed increased experiences of discrimination as well as isolation. Correlational analysis confirmed the co-occurrence of these two themes, revealing a positive relationship between feeling isolated and feeling discriminated against. Asian males were more likely to feel isolated and structure their interactions to avoid appearances of impropriety, which reflects previous accounts of Asian professors in the literature (Culotta, 1993) in which they experienced isolation from their colleagues and increased student mentoring demands because of their minority status.