May 22, 2024 | Volume 14 - Issue 1

William B. Lane, Jr., Timothy J. Hakenewerth, Camille D. Frank, Tessa B. Davis-Price, David M. Kleist, Steven J. Moody

Interpretative phenomenological analysis was used to explore the simultaneous supervision experiences of counselors-in-training. Simultaneous supervision is when a supervisee receives clinical supervision from multiple supervisors. Sometimes this supervision includes a university supervisor and a site supervisor. Other times this supervision occurs when a student has multiple sites in one semester and receives supervision at each site. Counselors-in-training described their experiences with simultaneous supervision during the course of their education. Four superordinate themes emerged: making sense of multiple perspectives, orchestrating the process, supervisory relationship dynamics, and personal dispositions and characteristics. Results indicated that counselors-in-training experienced compounded benefits and challenges. Implications for supervisors, supervisees, and counselor education programs are provided.

Keywords: clinical supervision, simultaneous supervision, counselors-in-training, interpretative phenomenological analysis, counselor education

Supervision is a key component of counselor education in programs accredited by the Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP; 2015) and an ethical requirement in the ACA Code of Ethics (American Counseling Association, 2014). Supervision of counselors-in-training (CITs) serves the purpose of guiding counselor development, gatekeeping, and, ultimately, ensuring competent client care (Borders et al., 2014). For the present study, we defined simultaneous supervision as a pre-licensure CIT receiving weekly individual or triadic supervision from more than one supervisor over the same time period. At the time of the study, the 2016 CACREP standards required that internship and practicum students receive individual and/or triadic supervision averaging 1 hour per week throughout their clinical experience (Standards 3.L. & 3.H.). Some CITs may gain field experience at multiple clinical sites requiring individual site supervision at each site. Many programs require students to engage in faculty advising meetings (Choate & Granello, 2006), which may take a form analogous to formal supervision. Additionally, supervisees may have clinical supervision, focused on supervisee development and client welfare, as well as administrative supervision, focused on functionality and logistics within an agency; these roles may be fulfilled by the same person or at times by two separate supervisors (Kreider, 2014; Tromski-Klingshirn & Davis, 2007). Consequently, although simultaneous supervision is not required in and of itself, it often occurs in counselor education practice.

Supervision Foundations

Counseling supervision research has increased significantly in the last few decades (Borders et al., 2014). Borders and colleagues (2014) developed best practices for effective supervision, including emphasis on the supervision contract, social justice considerations, ethical guidelines, documentation management, and relational dynamics. Previous research has overwhelmingly demonstrated that a strong supervisory alliance is the bedrock of effective supervision (Bernard & Goodyear, 2019). Sterner (2009) further studied the supervisory relationship as a mediator for supervisee work satisfaction and stress. Lambie and colleagues (2018) developed a CIT clinical evaluation to be used in supervision, with strength in assessing personal dispositions in addition to clinical skills. A review of the supervision literature revealed that a strong supervisory relationship based in goal congruence, empathic rapport, and transparent feedback processes (Bernard & Goodyear, 2019; Borders et al., 2014; Sterner, 2009) generate mutual growth between supervisor and supervisee, enhancing clinical work. Additionally, CACREP mandates that faculty and site supervisors foster CIT professional counselor identity through the supervisory process (Borders, 2006; CACREP, 2015).

Counselor development is also a crucial factor in clinical supervision. An entire category of supervision models centralizes the professional development of supervisees in their approach (Bernard & Goodyear, 2019). One of the most widely known models, the Integrative Developmental Model, plots learning, emotion, and cognitive factors across multiple stages of therapist development (Stoltenberg & McNeill, 2010). By focusing on overarching themes of self–other awareness, autonomy, and motivation, the Integrative Developmental Model (Stoltenberg & McNeill, 2010) illuminates how supervisees fluctuate and grow in their anxiety, self-efficacy, reliance on structure, and independence. All these factors may have substantial impact when considering the complexity that simultaneous supervision brings. Furthermore, professional dispositions of openness to feedback and flexibility and adaptability (Lambie et al., 2018) may have additional developmental implications when considering the complexity of simultaneous supervision.

Ethics similarly serve as a foundation of supervisory experiences. Multiple standards and principles of the ACA Code of Ethics (2014) may be complicated by simultaneous supervision and require special attention. Veracity may be of particular interest given the commonality of supervisee nondisclosure (Kreider, 2014), multiplied by the added number of supervisors in one time period. Furthermore, specific standards in Section D: Relationships With Other Professionals may be implicated by obligations in working with multiple professionals; multiple standards in Section F: Supervision, Training, and Teaching may be indicated because of the convergence of both teaching and clinical supervision in counselor training programs; and, finally, reconciling the additional complexities of simultaneous supervision not explicitly identified elsewhere in the 2014 Code of Ethics may elicit a need to carefully consider Section I: Resolving Ethical Issues. With more parties involved, greater nuance would be expected in ethical decision-making.

Much of the foundational research and reviewed contextual factors have either focused specifically on sole supervision or do not differentiate between sole and simultaneous supervision. When considering best supervision practices, the phenomenon of simultaneous supervision presents distinct practical concerns. Exploration is needed to better understand how supervisees might navigate different but related supervisory relationships, how goals and tasks can be congruent across separate supervisory experiences, and how supervisees would make meaning of multiple sources of feedback. Despite the apparent use of simultaneous supervision in counselor education programs, few researchers have explored these dynamic concerns.

Multiple Supervisors and Multiple Roles

Early researchers began to conceptualize the challenges and strengths inherent in simultaneous supervision in both counseling (Davis & Arvey, 1978) and clinical psychology (Dodds, 1986; Duryee et al., 1996; Nestler, 1990), with mixed results overall. Nestler (1990) identified the difficulties in receiving contradictory feedback from multiple supervisors, reflective of fundamental differences in the supervisors’ approaches. Dodds (1986) similarly identified multiple potential stressors in having concurrent supervisors at agency and training settings. Dodds argued that although the general goals to teach and serve clients overlapped, each had inherent differences in their primary institutional goals and structures. Duryee and colleagues (1996) described a beneficial view of simultaneous supervision, in which supervisees overcome conflicts with site supervisors via support and empowerment from academic program coordinators. Davis and Arvey (1978) presented a case study in which supervisees, in a raw comparison, more highly favored the dual supervision overall. These findings highlight the dynamics that occur in the context of simultaneous supervision and connect with recent findings.

Recent researchers have focused on dual-role supervision, defined as one individual supervisor serving as both a clinical and administrative supervisor to one or more supervisees (Kreider, 2014). Kreider (2014) investigated supervisee self-disclosure as related to three factors: supervisor role (dual role or single role), supervisor training level, and supervisor disclosure. Level of supervisor disclosure was found to be significant in explaining differences in supervisee self-disclosure and was hypothesized as a mitigating factor in supervisor role differences (Kreider, 2014). Tromski-Klingshirn and Davis (2007) surveyed the challenges and benefits unique to dual-role supervision for post-degree supervisees. Most supervisees reported neutral to positive outcomes from a dual-role supervisor, but a minority of supervisees noted power dynamics and fear of disclosure as primarily problematic (Tromski-Klingshirn & Davis, 2007), similar to the earlier hypotheses of Nestler (1990) and Dodds (1986). The small amount of existing research solidifies the prevalence of simultaneous supervision and the challenges and benefits for the supervisees. A missing link emerges in understanding how CITs come to understand their experience in simultaneous supervision from a qualitative perspective.

The distinct focused phenomenon of simultaneous supervision is limited in counseling literature. The few conceptual examinations of simultaneous supervision in the mental health literature have indicated confusion and role ambiguity (Nestler, 1990), while at other times simultaneous supervision has been noted to improve comprehensive learning (Duryee et al., 1996). Our study addresses the gap in the literature regarding current simultaneous supervision in counselor education utilizing qualitative analysis.

Method

Given the limited research on simultaneous supervision and its prevalence within the profession, we decided to explore this phenomenon qualitatively. Our research question was “What is the experience of CITs receiving simultaneous supervision from multiple supervisors?” We used interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) to explore this question because of its utility with counseling research, grounded methods of analysis, and emphasis on both contextual individual experiences with the phenomenon and general themes (Miller et al., 2018).

Research Team

At the time of the study, the research team consisted of four doctoral students—William B. Lane, Jr., Timothy J. Hakenewerth, Camille D. Frank, and Tessa B. Davis-Price—who each had previous experience with simultaneous supervision as supervisees and supervisors. The team’s perspective of this phenomenon from both roles informed their interest in and analysis of the phenomenon. The fifth member of the team, David M. Kleist, was our doctoral faculty research advisor. The sixth author, Steven J. Moody, provided support in the writing process.

Participants and Procedure

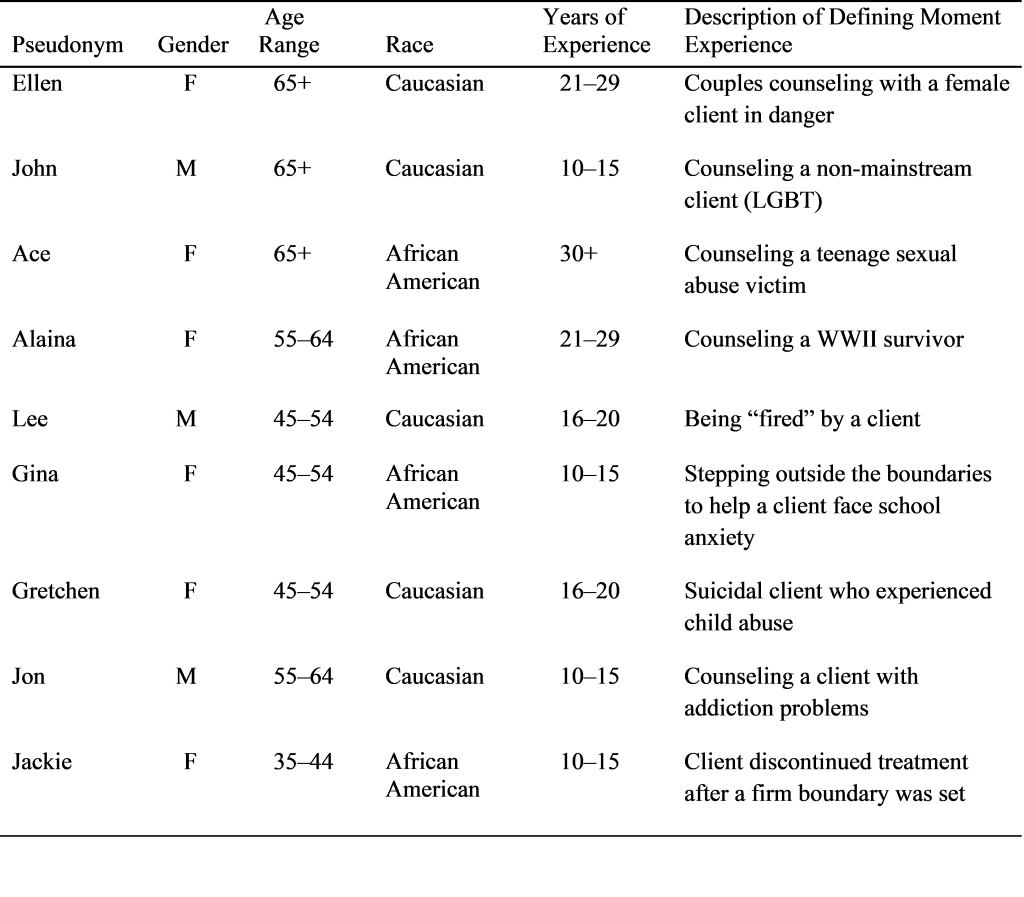

Our participants were four CITs from CACREP-accredited graduate programs accruing internship hours. Smith et al. (2009) suggested seeking three to six participants for IPA, as this allows researchers to explore the phenomenon with individual participants at a deeper level. All four participants specialized in either addiction, school, or clinical mental health counseling, and identified as White, female CITs ranging from 23 to 37 years old. Additionally, each participant reported receiving supervision from at least two supervisors to include university-affiliated supervisors and site supervisors. Each participant came from a different university representing the Rocky Mountain and North Central regions of the Association for Counselor Education and Supervision. To protect confidentiality, each participant selected a pseudonym for the study.

After securing approval from our university’s review board, we recruited participants through purposive convenience sampling. We posted a recruitment email to the CESNET listserv, an informational listserv for counselor educators and supervisors. This listserv was selected as an initial step of convenience sampling to increase the potential to reach a broad range of counseling programs. Nine individuals responded to the call to participate in the research by taking a participant screening survey that helped us determine suitability for the study. After removing individuals from research consideration because of potential dual relationships, nonresponse, or not meeting inclusion criteria, four individuals were selected as participants. We further planned to engage in serial interviewing to gain richer details of the phenomenon and achieve greater depth with the four participants (Murray et al., 2009; Read, 2018). Prior to data collection, the researchers completed a brief phone screening with each participant to review the interview protocol and explain the phenomenological approach guiding the questions. A $40 gift card was provided as a research incentive to participants. Our selection criteria included (a) being a master’s student within a CACREP counseling program, (b) currently accruing internship hours, and (c) receiving simultaneous supervision. We selected participants in internship only because homogenous sampling helps produce applicable results for a given demographical experience (Smith et al., 2009).

Data Collection

Consistent with the recommendations of Smith et al. (2009), we conducted two semi-structured interviews with each participant lasting between 45–90 minutes. We utilized the online videoconferencing platform Zoom to conduct and record the interviews. First-round interviews consisted of four open-ended questions (see Appendix) that allowed participants to explore the experience of simultaneous supervision in detail (Pietkiewicz & Smith, 2014). These questions were open-ended to allow participants to explore the how of the phenomenon (Miller et al., 2018). The final interview questions were developed through initial generation based off research and personal experiences with the phenomenon, refinement in consultation with the research advisor, and interview piloting with volunteer students who did not participate in the study. Research participants were asked about their overall experience with having multiple supervisors, benefits and detriments of simultaneous supervision, and the meaning they made as a result of experiencing simultaneous supervision. Second-round interview questions were developed based on participant responses to first-round interview questions. After two rounds of interviews and analysis, we conducted a final member check to confirm themes. All participants expressed that the developed themes were illustrative of their lived experiences with simultaneous supervision.

Data Analysis

We followed IPA’s 6-step analysis process as outlined by Smith et al. (2009) and added a seventh step with the use of the U-heuristic analysis for group research teams (Koltz et al., 2010). Our process consisted of first coding and contextualizing the data individually, followed by group analysis, triangulated with the fifth author, Kleist, as research advisor. We completed this process for each participant and then analyzed themes across participants as suggested by Smith et al. We reached consensus that four superordinate themes emerged with 11 subthemes across the two rounds of interviews. All participants endorsed agreement with the themes from their experiences in simultaneous supervision during the member check process.

Trustworthiness

We integrated Lincoln and Guba’s (1985) framework in conducting multiple procedures for establishing trustworthiness and credibility. We demonstrated prolonged engagement and persistent observation through consistent coding meetings over the span of 1 year. Additionally, we adapted the U-heuristic analysis process during data analysis to analyze data individually and collectively to strengthen the credibility of our findings (Koltz et al., 2010). Finally, after we developed the themes, we triangulated the results with participants via a member check, ensuring the individual and group themes matched their idiographic experiences.

We bridled our personal experiences with simultaneous supervision throughout the research process. Bridling recognizes that researchers have had close personal experiences with the phenomenon and that bias is best managed by recognition rather than elimination (Stutey et al., 2020). The four principal investigators, Lane, Hakenewerth, Frank, and Davis-Price, individually engaged in memo writing, discussed personal reactions to the data, and participated in group discussions regarding meaning-making of the phenomenon with Kleist serving as research advisor.

Results

Our data analysis produced four superordinate themes identified across all cases. These themes were (a) making sense of multiple perspectives, (b) orchestrating the process, (c) supervisory relationship dynamics, and (d) personal dispositions and characteristics. In the sections that follow, each theme is described in further detail and exemplar quotes are given to support their development.

Making Sense of Multiple Perspectives

Making sense of multiple perspectives was defined as the receipt and conceptualization of supervisory feedback from multiple supervisors during the same academic semester. Supervisees identified their supervisors as having differing professional orientations. At times, these differing backgrounds led to supervisors providing differing opinions for the same client.

Participants used metaphors to make meaning of the distinct offerings of their supervisors’ feedback. An example of capturing multiple perspectives was one participant, Emma, utilizing the ancient Indian parable of “The Blind Men and the Elephant” (Saxe, 1868): “The point of the story is all the world religions might have a piece of the picture of God, you know. And so between all of us [clinicians and supervisors] together, maybe we have a perspective of truth.” Through retelling of the Indian fable, this participant was able to vividly capture her personal perspective of differing viewpoints through an integrative lens as opposed to a conflict of ideas. Within this superordinate theme, the two subthemes of supervisee framing and safety net vs. minefield emerged.

Supervisee Framing

Supervisee framing focused on the participant’s personal view of hearing multiple perspectives from supervisors within simultaneous supervision. Some participants described hearing varying perspectives as being helpful and valuable, providing support, and increasing confidence. They typically framed the idea of receiving various feedback as a way to gain ideas and then make their own informed decisions. Molly shared this positive perspective when she stated, “I like coming to [my differing supervisors] with different issues I have with different clients because I feel like they both have valuable experience, but in different ways.” In contrast, Hailey identified multiple perspectives as being “really difficult,” and Diana noted they were “more frustrating than beneficial” and confusing. Similarly, Hailey stated, “My supervisors are all very different, so they give me different feedback, and a lot of times it conflicts with what the other one has said.” The supervisee’s framing of discrepant feedback impacted their overall perceptions with simultaneous supervision. Supervisees either valued or were confused by the feedback. Generally, participants spoke of times when multiple perspectives were beneficial and difficult, but it appeared all participants were left with the task of making sense of multiple perspectives while receiving simultaneous supervision.

Safety Net vs. Minefield

Making sense of multiple perspectives was described as creating a safety net of support, while others found the experience to be a minefield that increased confusion, ambiguity, and isolation. Emma and Molly characterized their experience as providing support in an often overwhelming profession. Molly articulated, “I feel like if I didn’t have that good support, that good foundation, I don’t think I could do it because it’s just so much.” She later added, “I feel like getting those different perspectives, getting that support, getting those encouragers is beneficial because I don’t feel as overwhelmed, even though it’s overwhelming.”

Participants also perceived their simultaneous supervision as a minefield wherein they believed they were in double binds. Hailey reflected on an experience when her supervisors contradicted each other and expressed, “It just sucked because I was doing what my supervisor told me to do and suggested I do, and then I was told everything I did was wrong.” Diana echoed that discrepant feedback felt like a constant dilemma needing to be managed “carefully.” In reflecting on contradicting supervision, Diana said, “It’s hard because everybody has their own thing. . . . You just kind of have to appease everyone.” In the face of conflict, it was easier to placate than resolve. Participants’ cognitive framing was a major element of the phenomenon. Whereas making sense of multiple perspectives focused on the cognitive elements of receiving feedback from different supervisors, the next theme focused on the behavioral elements.

Orchestrating the Process

Another theme that emerged in our data analysis was that of supervisees orchestrating the process of simultaneous supervision. This theme revolved around action-oriented steps in supervision. The essence of this theme was captured when Hailey acknowledged the need for “checking her motives” on what she shared with different supervisors. She asked herself, “Am I sharing this with this [supervisor] because I feel like they’re going to answer in the way that I feel like . . . they should answer, because it’s easier for me?” Hailey acknowledged the difficulty in this, countering with, “Or am I just going to them because it’s that person that I’m supposed to see?” Hailey recognized that having options when it came to approaching supervisors meant that disclosure needed to be intentional rather than straightforward as it is when CITs only have one choice. Participants were aware of their process as they picked and chose what to share with whom, through seeking out a preferred supervisor and through managing the practical aspects of having multiple supervisors. The subthemes of picking and choosing, seeking a preferred perspective, and managing practical considerations were a part of orchestrating the process.

Picking and Choosing

The subtheme of picking and choosing emerged in how our participants described what they would share in supervision and the course of action taken in their counseling practice. This subtheme was labeled as an in vivo code, derived from Hailey’s quote: “So I definitely pick and choose what I talk to about each one. Because—this sounds terrible—but I respect the one [supervisor] more.” Hailey also described feelings of vulnerability and self-efficacy from week to week, related to her reactions from feedback: “I knew after having such a hard supervision last week showing tape, I was like, ‘I cannot be super vulnerable right now. I need to choose something that’s more surface level.’” Molly experienced picking and choosing as a means of proactively managing the repetitive nature of supervision: “I think just bringing different things to different supervisors is really helpful, and not constantly talking about the same client or the same situation, because that gets obnoxious and repetitive, and you’re gonna get a hundred different opinions.”

After receiving feedback, participants had varying perspectives on how to integrate and transfer constructs into action. Some participants viewed discrepant feedback as mutually exclusive, whereas others had a more integrative perspective. Molly expressed frustration in choosing between differing feedback from multiple supervisors: “Sometimes I don’t really know which I should go with, which I should choose, and which would be best for the client. . . . It’s like a double-edged sword, like it’s good at some points, but then bad at others.” Diana, who expressed similar frustration in choosing between perspectives, relieved this tension by resolving that, “I have to live with myself at the end of the day, so as long as it’s not unethical, I don’t worry about it too much. And as far as the stuff that I’m told that needs to be done, I do what I can.” Other participants espoused a much more integrative perspective. Emma stated, “I think the thing I like the best about it is actually when [my supervisors] have different advice . . . because then I feel like between the two, I can kind of find what I really like.” All participants spoke about selecting what to share with supervisors and choosing how to integrate feedback into action.

Seeking a Preferred Perspective

Coinciding with picking and choosing, participants also sought a preferred perspective in the process of receiving simultaneous supervision and orchestrating the process. Some reported the decision to go to one supervisor over another was situationally based and determined by clinical skill or specialty of the supervisor. Diana captured this as follows, “Well, I can have a conversation with either. I just get very different answers. If it’s the technical stuff of what has to be done—her. If it’s ‘how would you approach the situation?’ I do tend to talk to him.” Diana also likened seeking a preferred perspective to a child searching for a desired answer: “It’s like, who do I want to talk to? It’s almost like, talk to the person you want for the answer you want. It’s like, ‘Well, if Mom doesn’t have the right answer, go talk to Dad.’”

Managing Practical Considerations

All participants spoke to the practicality of meeting with multiple supervisors. Even though some participants strongly valued having multiple supervisors, all participants spoke to the larger time commitment needed in having simultaneous supervision. Molly captured how simultaneous supervision felt overwhelming, adding to the many other sources of feedback she received: “I already have two group supervisions. I’ve heard opinions about this, and I’m hearing other perspectives of my classmates, of my coworkers. Now I have to have triadic and hear their opinions and have individual. . . . It’s just a lot.” Emma framed this time commitment as detracting from her other obligations: “It just starts adding up. Like, my whole Tuesday evenings are gone, and that’s time I could be seeing clients.” Hailey expressed frustration about the obligatory nature and placating to the program’s requirement to see multiple supervisors: “Honestly, I just give the other supervisor little things because I know I have to talk to him . . . and it’s more, like, checking a box.” Finally, Emma captured how this time commitment was epitomized in documentation: “And the paperwork got exhausting, too, because I had to do everything in triplicate sometimes.” She further talked about the additional mental labor: “And now what are we gonna talk about since I just talked about all of this with [a different supervisor] and feel like I found good solutions, you know?” Supervisees had to manage their time and fit more supervision into their schedules. Simultaneous supervision added complexity, and participants needed to orchestrate this process to manage it efficiently and effectively.

Supervisory Relationship Dynamics

Supervisory relationship dynamics was determined to be a superordinate theme as it reflected on the connecting and disconnecting elements of the supervisory relationship. This theme was broken into three subthemes. The subthemes of vulnerability, power dynamics, and systems of supervision illustrated the relational dynamics within simultaneous supervision.

Vulnerability

In supervisory relationships, feelings of safety and vulnerability influenced interactions with different supervisors. To illustrate, Hailey noted:

There are certain supervisors I feel more safe with. And so those are the ones that I share more with . . . versus some of them I feel less safe with . . . I don’t share as much with them that is vulnerable, or that makes me vulnerable.

Participant experiences highlighted how vulnerability dictated what and how elements were shared in simultaneous supervision.

Power Dynamics

The determination of safety occurred within power dynamics. Diana commented that multiple supervisors serving as evaluators and gatekeepers can create “this weird relationship where you don’t want to be too vulnerable because this person is also your boss and can decide if you are going to stay in that position or not.” Diana and Hailey noted feeling disempowered and disengaged from supervision, referring to supervisors as “bosses” throughout their interviews. When participants perceived their supervision as a firmly directive process, discrepant directives were especially distressing. Diana rephrased this sentiment: “I guess the best thing to compare it to would be if you have more than one boss, but they all give you a different, ‘I want this, I want this, I want this.’” Emma’s experience was more accordant, and she specifically expressed at one time, “None of [my supervisors] are really super bossy either.” Participants identified power dynamics as salient aspects of how they experienced supervision and with whom they connected. Working with more than one supervisor sometimes resulted in characterization of “good” and “bad” supervisors, making individual supervisory relationship dynamics crucial.

Systems of Supervision

Participants conceptualized the phenomenon as broader systems of supervision in which individual supervisors were interacting with each other. Emma noted, “The two faculty supervisors work very closely together and I assume talk all the time.” Emma and Molly provided multiple examples of supervisors working together to best serve clients, thus bolstering supervision through their combined expertise. Molly stated, “It was nice because [my two supervisors] were in agreement and I felt comfortable going into session with [my client].” Even negative experiences contributed to systems of supervision. Hailey reported seeking out additional support when her assigned supervisory relationships did not meet her needs, widening the reach of simultaneous supervision even more: “By not being a good supervisor, he helps me seek out other resources and figure it out for myself.” Finally, Molly noted that supervisor coordination was primarily for evaluation at the end of the semester and only if problems arose. However, she imagined what it would be like if they were more collaborative:

They would have had a better understanding of the way I work in a counseling room. . . . Because my site supervisor really understood how I approached things and the way I would interact with my clients, but I feel like my university supervisor didn’t really, like, she had little snippets of what I was like in a counseling room.

Power, vulnerability, and systems in the supervisory relationship impacted supervisees from multiple levels in their clinical journey.

Personal Dispositions and Characteristics

Personal dispositions and characteristics resulted from participants speaking about the phenomenon as well as what they said about their supervisors. Three dispositions that emerged as relevant were tolerance for ambiguity, curiosity, and availability. The first two subthemes were identified as they spoke about the phenomenon and the third subtheme was a characteristic present because of the nature of simultaneous supervision.

Tolerance for Ambiguity

Tolerance for ambiguity was found to be a critical disposition. This disposition allowed participants to see differences in opinion as helpful. Emma shared that she “very rarely” saw people as giving her “conflicting information.” She said that she saw it as everybody having their own perspective. This connected to her ability to view multiple perspectives as “pieces of the puzzle,” as she expressed earlier in her retelling of the Indian fable. Although participants sometimes expressed concern about direction, Diana shared, “You can ask questions and you can not know and it’s okay.” This disposition directly related to how they reconciled and then reacted to multiple perspectives of simultaneous supervisors.

Curiosity

Curiosity also manifested more implicitly with supervisees. Participants showed curiosity by taking interest in what supervisors had to say, seeking more information, or staying open to difficult feedback. Hailey shared that simultaneous supervision “definitely requires a lot of continuing to look inward and examining your motives and yourself and what the supervisors have said.” In speaking more broadly, Emma shared, “So I don’t think I’ll ever give [simultaneous supervision] up now that I’ve kind of experienced how valuable it is to get another professional opinion.” Curiosity manifested itself as a transient characteristic for other participants. Diana experienced transference with one of her supervisors, which was a barrier to her ability to exhibit this helpful disposition. One of her supervisors suggested that she try and work things out with another supervisor she was having difficulty with, to which Diana said, “No. Who is gonna walk into their supervisor and be like, ‘Okay, so my problem with you is you’re a bitch. You remind me of my abusive ex.’ . . . But at the same time, I have to work with her.” This was an example of Diana demonstrating a closing off to feedback. Both tolerance for ambiguity and curiosity manifested and impacted their experience of multiple perspectives.

Availability

An important disposition was emotional and physical availability. Emma expressed that “there’s always somebody I can get a hold of.” Hailey expressed that she had “more coverage just in general,” but also questioned her supervisors’ true availability: “Do I even need to bring this to supervision or can I work on this on my own? Because sometimes I feel like I annoy them.” All participants expressed that availability was important to their experience, although physical availability did not always translate to being available to discuss what the supervisee wanted. Those participants who identified supervisors within simultaneous supervision as being more available had more positive thoughts regarding simultaneous supervision.

Discussion

All four participants identified the complex position of CITs receiving supervision from more than one supervisor. The results align with the growing body of literature affirming the importance of a positive working relationship between CITs and supervisors (Bernard & Goodyear, 2019; Borders et al., 2014; Sterner, 2009) as well as significant differences between faculty and site supervision (Borders, 2006; Dodds, 1986). The results parallel supervision literature detailing the multiple roles of supervisees (Bernard & Goodyear, 2019) who, unlike supervisors, are not required to have specific education in supervision. The theme of personal dispositions has been studied extensively in counselor education, resulting in prominent placement in clinical assessment instruments (Lambie et al., 2018). The presented themes diverge from the current research base in their construction of a clear model of simultaneous supervision. The subthemes of picking and choosing, seeking a preferred perspective, and systems of supervision illustrate the interpersonal dynamics of simultaneous supervision that is distinct from sole supervision, an underrepresented phenomenon in the supervision literature. Participants in this study reported mixed feelings with simultaneous supervision. Four primary themes emerged from this study: making sense of multiple perspectives, orchestrating the process, supervisory relationship dynamics, and personal dispositions and characteristics. These four themes encompass many areas of the supervisory experience while illuminating guidelines for supervisors engaging in simultaneous supervision.

Implications

Results from this study reinforce the complex levels of integration CITs experience when receiving supervision from multiple supervisors. This process of integration can lead to confusion, ambiguity, and also deeper understanding. The results indicate that the perceived benefit of simultaneous supervision was often based on the relationship between the supervisor and CIT, ability and support to organize the process, and the personal dispositions of the CIT. The implications for this research target three populations.

Supervisors

The findings of this study indicate several implications for supervisors working with clinicians receiving simultaneous supervision. First and foremost, the critical importance of the supervisory relationship to supervision in general (Bernard & Goodyear, 2019) was further substantiated as a foundation for effective simultaneous supervision. Questionable supervisee behaviors such as intentional nondisclosure via seeking a preferred perspective or picking and choosing can be avoided through purposefully fostering trust in the relationship. Similarly, supervisors may support the perspective of simultaneous supervision as a safety net if support for vulnerability is established and the relationship is actively attended to. Supervisors should be mindful of their availability to CITs and periodically check in to see if they are meeting the needs of the supervisee.

Supervisors who are aware of the themes developed from this research may be better equipped to capitalize on benefits and mitigate challenges. One benefit was that simultaneous supervision allowed participants to receive multiple synergistic perspectives regarding their work with clients. Depending on the developmental level of the supervisee and the demeanor of the supervisor, however, these multiple perspectives may present challenges. Supervisors can apply their knowledge of developmental models to tailor their interventions. Supervisors might anticipate that CITs earlier in development (e.g., in practicum) may require structured support in simultaneous supervision to avoid performance anxiety and frustration from rigid applications of multiple perspectives consistent with this stage (Stoltenberg & McNeill, 2010). Supervisors may also wish to focus supervision on interventions that actively facilitate development of these dispositions, such as employing constructivism to elicit greater cognitive flexibility (Bernard & Goodyear, 2019).

Some early-stage supervisees may experience challenges when navigating varying perspectives and feedback provided to them by multiple supervisors. Challenges can be mitigated when supervisors broach the topic of simultaneous supervision with supervisees early. Additionally, when supervisors ensure they respect other supervisors and create collaborative relationships, supervisee difficulty with simultaneous supervision may decrease. When a supervisor learns of a differing opinion of another supervisor, it is important that it is broached as a variance in approach rather than an incorrect practice. Supervisees experiencing difficulties with simultaneous supervision may also benefit from supervisors checking in with them regarding the variable feedback they are receiving. A collaborative supervisory system may strengthen supervisee development and integration of counseling constructs. Counseling programs can play a key role in setting systemic expectations for supervisors and supervisees.

Counselor Education Programs

Accredited counselor education programs have autonomy in how they meet various CACREP (2015) supervision and clinical requirements. Programs may choose to require simultaneous supervision, may require multiple clinical sites, and may utilize faculty advising as supplementary clinical supervision. In unique situations such as students completing two tracks or receiving additional supervision for gatekeeping reasons, how programs manage simultaneous supervision can become complex. Best practice guidelines, policies, and procedures regarding simultaneous supervision can be made clear in clinical handbooks, with clinical coordinators, and in material for site supervisors. This would help to address the supervisee confusion from the programmatic side. Another important implication with simultaneous supervision is to consider the supervisory process through a systemic lens. When simultaneous supervision is utilized, there will be many interactions occurring outside of the dyad or triad apparent to one individual supervisor. When supervisors collaborate and communicate, supervisees may be more likely to receive congruent feedback, understand gatekeeping action, and receive consistent expectations. In particular, communication between academic and clinical supervisors can bridge the gap between idealism and practicality (Bernard & Goodyear, 2019; Choate & Granello, 2006). Programmatically mandated, semesterly site visits and opportunities for regular check-ins could fulfill this purpose.

Supervisees

Participants often spoke to the challenge of organizing simultaneous supervision effectively in relation to feedback, documentation, and case presentation material. Although a certain level of organizational skill is expected of graduate students, the coordination required in simultaneous supervision often seemed unanticipated and unwieldy for students. Preparing for the supervision experience in another course and/or an orientation in lab supervision may aid in this. All participants discussed, at varying distress levels, how having supervision scheduled too close together (e.g., same day or two days in a row) increased repetitiveness and thus made simultaneous supervision feel less efficacious. Supervisees may want to intentionally schedule supervision sessions spaciously to avoid potential repetition or redundancy. With the steady increase in virtual supervision, scheduling supervision in ideal time frames may be easier with increased access and absent travel time. Programmatic preparation, intentional scheduling, and collaborative supervision notes may aid the simultaneous supervision process.

In the areas of core dispositions, CITs who embraced ambiguity and fostered reflexivity, curiosity, and flexibility tended to navigate simultaneous supervision with more ease. Reflexivity, curiosity, and tolerance for ambiguity seemed to strengthen the ability to receive feedback from multiple sources, integrate feedback appropriately, and maintain strong supervisory relationships. A typical guiding question from participants was, “How can I apply this combined feedback to my particular site and client while still maintaining my own clinical identity?” Necessarily, students will enter a program with differing levels of core strengths, yet any student can be encouraged to strengthen their core dispositions. Supervisees are encouraged to think about simultaneous supervision with the same organization and openness required for other courses such as pre-practicum and multicultural counseling. Correspondingly, supervisors have complex responsibilities maintaining ethical competent care, organizing supervision, and fostering these core dispositions.

Ethical Implications of Simultaneous Supervision

In addition to recommendations for the three populations above, findings from this study highlight ethical considerations. Worthington et al. (2002) identified “intentional nondisclosure of important information” (p. 326) and “inappropriate methods of managing conflict with supervisors” (p. 329) as two major ethical issues that are unique to supervisees and correlate with some of the participant supervisees’ experiences of triangulating supervisors, seeking outside consultation to circumvent supervisors, or intentionally withholding information. To ensure client welfare, supervisors and supervisees may benefit from explicitly discussing ethical implications and considerations unique to this phenomenon at the outset of supervision and again when conflicts arise. Future research that addresses limitations of this study will further clarify the role of supervisors, supervisees, and programs in simultaneous supervision as well as specific ethical guidelines.

Limitations and Future Directions

Limited information was gathered about the specific counselor education programs in which our participants were enrolled, restricting the inferences able to be made about simultaneous supervision in context. We also chose a convenience sampling method using CESNET and selected four participants. The choice of indirect sampling, primarily through counselor educators redirecting calls to their students, may have limited participants. Further, all participants of this study identified as the same gender and race, which limits the diversity of experience shared. Future researchers may consider sampling more participants to get a broader exploration of the phenomenon. In doing so, researchers may be able to obtain greater representation in gender and race to increase the transferability of this study.

This study focused on the phenomenon of simultaneous supervision as experienced within individual and triadic supervision. Simultaneous supervision is embedded within the broader experience of supervision, and isolating the phenomenon required vigilance by the researchers. Future researchers would benefit from intentional follow-up questions that better focus participants on simultaneous supervision rather than individual experiences with supervisors. As our study did not explicitly ask participants to distinguish between university-affiliated and site supervisors, future researchers may pursue a qualitative study that highlights the difference. Other research may utilize grounded theory to develop a model of simultaneous supervision for supervisors and supervisees to follow or focus explicitly on supervisors’ perspectives of simultaneous supervision. Quantitative research may illuminate the frequency and use of simultaneous supervision in counselor education programs overall or identify correlations between counselor dispositions such as tolerance for ambiguity and supervision outcomes in simultaneous supervision. Because of the lack of information regarding the phenomenon of simultaneous supervision, many opportunities for research regarding the phenomenon persist.

Conclusion

Overall, the findings from this research indicate CITs valued greater support and thrived when integrating “both/and thinking” in navigating feedback from multiple supervisors. This perspective reinforces the need for systemic communication among counselor educators and supervisors. Additionally, results suggest CITs would benefit from supervisors broaching the topic of simultaneous supervision early in their clinical experience.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

American Counseling Association. (2014). ACA code of ethics. https://www.counseling.org/resources/aca-code-of-ethics.pdf

Bernard, J. M., & Goodyear, R. K. (2019). Fundamentals of clinical supervision (6th ed.). Pearson.

Borders, L. D. (2006). Snapshot of clinical supervision in counseling and counselor education: A five-year review. The Clinical Supervisor, 24(1–2), 69–113. https://doi.org/10.1300/J001v24n01_05

Borders, L. D., Glosoff, H. L., Welfare, L. E., Hays, D. G., DeKruyf, L., Fernando, D. M., & Page, B. (2014). Best practices in clinical supervision: Evolution of a counseling specialty. The Clinical Supervisor, 33(1), 26–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2014.905225

Choate, L. H., & Granello, D. H. (2006). Promoting student cognitive development in counselor preparation: A proposed expanded role for faculty advisers. Counselor Education and Supervision, 46(2), 116–130.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2006.tb00017.x

Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2015). 2016 CACREP standards. https://www.cacrep.org/for-programs/2016-cacrep-standards/

Davis, K. L., & Arvey, H. H. (1978). Dual supervision: A model for counseling and supervision. Counselor Education and Supervision, 17(4), 293–299. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.1978.tb01086.x

Dodds, J. B. (1986). Supervision of psychology trainees in field placements. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 17(4), 296–300. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.17.4.296

Duryee, J., Brymer, M., & Gold, K. (1996). The supervisory needs of neophyte psychotherapy trainees. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 52(6), 663–671. https://doi.org/bmp9p9

Koltz, R. L., Odegard, M. A., Provost, K. B., Smith, T., & Kleist, D. (2010). Picture perfect: Using photo-voice to explore four doctoral students’ comprehensive examination experiences. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 5(4), 389–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2010.527797

Kreider, H. D. (2014). Administrative and clinical supervision: The impact of dual roles on supervisee disclosure in counseling supervision. The Clinical Supervisor, 33(2), 256–268.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2014.992292

Lambie, G. W., Mullen, P. R., Swank, J. M., & Blount, A. (2018). The Counseling Competencies Scale: Validation and refinement. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 51(1), 1–15.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2017.1358964

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. SAGE.

Miller, R. M., Chan, C. D., & Farmer, L. B. (2018). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: A contemporary qualitative approach. Counselor Education and Supervision, 57(4), 240–254. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12114

Murray, S. A., Kendall, M., Carduff, E., Worth, A., Harris, F. M., Lloyd, A., Cavers, D., Grant, L., & Sheikh, A. (2009). Use of serial qualitative interviews to understand patients’ evolving experiences and needs. BMJ, 339, b3702. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b3702

Nestler, E. J. (1990). The case of double supervision: A resident’s perspective on common problems in psychotherapy supervision. Academic Psychiatry, 14(3), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03341284

Pietkiewicz, I., & Smith, J. A. (2014). A practical guide to using interpretative phenomenological analysis in qualitative research psychology. Psychological Journal, 20, 7–14. https://doi.org/10.14691/CPPJ.20.1.7

Read, B. L. (2018). Serial interviews: When and why to talk to someone more than once. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918783452

Saxe, J. G. (1868). The poems of John Godfrey Saxe. Ticknor and Fields.

Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research (1st ed.). SAGE.

Sterner, W. (2009). Influence of the supervisory working alliance on supervisee work satisfaction and work-related stress. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 31(3), 249–263. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.31.3.f3544l502401831g

Stoltenberg, C. D., & McNeill, B. W. (2010). IDM supervision: An integrative developmental model for supervising counselors and therapists (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Stutey, D. M., Givens, J., Cureton, J. L., & Henderson, A. J. (2020). The practice of bridling: Maintaining openness in phenomenological research. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 59(2), 144–156.

https://doi.org/10.1002/johc.12135

Tromski-Klingshirn, D., & Davis, T. E. (2007). Supervisees’ perceptions of their clinical supervision: A study of the dual role of clinical and administrative supervisor. Counselor Education and Supervision, 46(4), 294–304. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2007.tb00033.x

Worthington, R. L., Tan, J. A., & Poulin, K. (2002). Ethically questionable behaviors among supervisees: An exploratory investigation. Ethics & Behavior, 12(4), 323–351. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327019EB1204_02

William B. Lane, Jr., PhD, NCC, BC-TMH, LPCC, is an assistant professor at Western New Mexico University. Timothy J. Hakenewerth, PhD, NCC, LPC, is an assistant professor at the University of Illinois Springfield. Camille D. Frank, PhD, NCC, LMHC, LPC, is an assistant professor at Eastern Washington University. Tessa B. Davis-Price, PhD, LMHC, LCPC, is an assistant professor at Saint Martin’s University. David M. Kleist, PhD, LCPC, is a professor and department chair at Idaho State University. Steven J. Moody, PhD, is a clinical professor at Adams State University. Correspondence may be addressed to William B. Lane, Jr., 1000 W College Ave, Silver City, NM 88061, william.lanejr@wnmu.edu.

Appendix

Interview Protocol

| Interview Questions |

| Round 1 |

| What has been your experience with having multiple simultaneous supervisors?

In your own experience, how has simultaneous supervision been a strength?

In your own experience, how has simultaneous supervision been challenging?

What have you learned about yourself and the counseling profession as you’ve experienced simultaneous supervision? |

| Round 2 |

| How has having simultaneous supervision been different from times when you have only had one supervisor?

What has it been like to have your supervisors interact with each other in regard to the supervision that you have received from them?

What personal dispositions (characteristics/qualities) do you think you have that influenced your experience of simultaneous supervision?

How has simultaneous supervision impacted your experience of safety or vulnerability in supervision?

What practical considerations have you needed to consider for having multiple simultaneous supervisors? |

Nov 26, 2019 | Volume 9 - Issue 4

Matthew C. Fullen, Jonathan D. Wiley, Amy A. Morgan

This interpretative phenomenological analysis explored licensed professional counselors’ experiences of turning away Medicare beneficiaries because of the current Medicare mental health policy. Researchers used semi-structured interviews to explore the client-level barriers created by federal legislation that determines professional counselors as Medicare-ineligible providers. An in-depth presentation of one superordinate theme, ineffectual policy, along with the emergent themes confounding regulations, programmatic inconsistencies, and impediment to care, illustrates the proximal barriers Medicare beneficiaries experience when actively seeking out licensed professional counselors for mental health care. Licensed professional counselors’ experiences indicate that current Medicare provider regulations interfere with mental health care accessibility and availability for Medicare-insured populations. Implications for advocacy are discussed.

Keywords: Medicare, interpretative phenomenological analysis, mental health, advocacy, federal legislation

Medicare is the primary source of health insurance for 60 million Americans, including adults 65 years and over and younger individuals with a long-term disability; the number of beneficiaries is expected to surpass 80 million by 2030 (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2019; Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, 2015). According to the Center for Medicare Advocacy (2013), approximately 26% of all Medicare beneficiaries experience some form of mental health disorder, including depression and anxiety, mild and major neurocognitive disorder, and serious mental illness such as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Among older adults specifically, nearly one in five meets the criteria for a mental health or substance use condition, and if left unaddressed, these issues may lead to consequences such as impaired physical health, hospitalization, and even suicide (Institute of Medicine, 2012).

Past research demonstrates that Medicare-eligible populations respond appropriately to counseling (Roseborough, Luptak, McLeod, & Bradshaw, 2012). Federal agencies such as the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) publish entire guides on how to use counseling to treat depression and related conditions in older adults (SAMHSA, 2011). However, researchers have noted specific challenges that Medicare-eligible populations, such as older adults, face when trying to access mental health services. Stewart, Jameson, and Curtin (2015) described acceptability, accessibility, and availability as three intersecting dimensions that may influence whether an older adult in need of help is able to access care. In contrast to acceptability, which focuses on whether older individuals are willing to participate in specific mental health services, accessibility and availability are both supply-side issues that impede older adults’ engagement with mental health services. Accessibility refers to factors like funding for mental health services and providing transportation support to attend appointments. Availability is used to describe the number of mental health professionals who provide services to older adults within a particular community.

Stewart et al.’s (2015) framework is useful when examining current Medicare policy and its impact on beneficiaries’ ability to participate in mental health treatment when needed. Experts have criticized Medicare for its relative inattention to mental health care (Bartels & Naslund, 2013), noting a remarkably low percentage of its total budget is spent on mental health (1% or $2.4 billion; Institute of Medicine, 2012), as well as a lack of emphasis on prevention services. In terms of accessibility, Congress has made efforts to remove restrictions to using one’s health insurance to access mental health treatment. For example, mental health parity laws were passed in 2008 to ensure that Medicare coverage for mental illness is not more restrictive than coverage for physical health concerns (Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act of 2008, 2008). Yet current Medicare policy may restrict the availability of services at the mental health provider level. For example, the Medicare program has not updated its mental health provider licensure standards since 1989, when licensed clinical social workers were added as independent mental health providers and restrictions on services provided by psychologists were removed (H.R. Rep. No. 101-386, 1989). Although counseling is only one mental health care modality available to Medicare beneficiaries, counselors can play a prominent role in the mental health treatment of older adults and people with long-term disabilities.

Meanwhile, there are references in the literature to a provider gap that may influence the ability of Medicare beneficiaries, including older adults, to access mental health services. A 2012 Institute of Medicine report described the lack of mental health providers as a crisis, and experts on geriatric mental health care have decried the lack of mental health professionals who focus their work on older adults (Bartels & Naslund, 2013). Despite these concerns, relatively little attention has been given to the influence of Medicare provider regulations in limiting the number of available providers. Scholars have noted that a significant proportion of graduate-level mental health professionals are currently excluded from Medicare regulations, despite providing a substantial ratio of community-based mental health services (Christenson & Crane, 2004; Field, 2017; Fullen, 2016; Goodman, Morgan, Hodgson, & Caldwell, 2018). Licensed professional counselors (LPCs) and licensed marriage and family therapists (LMFTs) jointly comprise approximately 200,000 providers (Medicare Mental Health Workforce Coalition, 2019), which means that approximately half of all master’s-level providers are not available to provide services under Medicare. Since their recognition as independent mental health providers by Congress in 1989, only licensed clinical social workers and advanced practice psychiatric nurses have constituted the proportion of master’s-level providers eligible to provide mental health services through Medicare.

Despite current Medicare reimbursement restrictions, Medicare beneficiaries are likely to seek out services from LPCs. Fullen, Lawson, and Sharma (in press-a) found that over 50% of practicing counselors had turned away Medicare-insured individuals who sought counseling services, 40% had used pro bono or sliding scale approaches to provide services, and 39% were forced to refer existing clients once those clients became Medicare-eligible. When this occurs, the Medicare mental health coverage gap (MMHCG) impacts providers and beneficiaries in several distinct ways. First, some beneficiaries may begin treatment only to have services interrupted or stopped altogether once the provider is no longer able to be reimbursed by Medicare. This can occur because of confusion about whether a particular patient’s insurance coverage authorizes treatment by a particular provider type, or when beneficiaries who have successfully used one type of coverage to pay for services transition to Medicare coverage because of advancing age or qualifying for long-term disability.

Most Medicare beneficiaries (81%; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2019) have supplemental insurance, including 22% who have both Medicare and Medicaid. Medicare beneficiaries who are dually eligible for Medicaid may be particularly vulnerable to the MMHCG. In most states, Medicaid authorizes LPCs to provide counseling services; however, in certain cases when these individuals also qualify for Medicare, the inconsistency in provider regulations between these programs can interfere with client care. A similar problem occurs when the Medicare-insured attempt to use supplemental plans (e.g., private insurance, Medigap) because of Medicare functioning as a primary source of insurance, and supplemental plans requiring documentation that a Medicare claim has been denied. Regardless of the reason for having to terminate treatment prematurely, early withdrawal from mental health treatment has been described as inefficient and harmful to both clients and mental health providers (Barrett et al., 2008).

The MMHCG also can interfere with clients’ ability to access services because of a lack of Medicare-eligible providers in a particular geographical region. For example, beneficiaries who reside in rural localities can have more difficulty finding mental health providers because of a general shortage of providers in these areas (Larson, Patterson, Garberson, & Andrilla, 2016). Larson et al. (2016) found that rural communities were less likely to have licensed mental health professionals overall, although these localities were more likely to have a counseling professional than a clinical social worker, psychiatric nurse practitioner, or psychiatrist. Historically, older adults from rural and urban localities experience a comparable prevalence of mental health disorders (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2018). However, studies consistently describe low rates of mental health services accessibility and availability within rural communities (Smalley & Warren, 2012). Establishing counselors as Medicare-eligible providers can reduce the disparities of mental health services accessibility and availability experienced by older adults in rural communities.

Although it is known that LPCs are currently excluded from Medicare coverage, it is not well understood what sort of impact this has on mental health providers and the Medicare beneficiaries who seek their services. Recent efforts to raise awareness of this issue have emerged in the literature (Field, 2017; Fullen, 2016; Goodman et al., 2018), but there has not yet been an investigation into the phenomenological experiences of mental health providers who are directly impacted by existing Medicare policy. The purpose of this study was to explore the lived experiences of mental health professionals who have turned away clients because of their status as Medicare-ineligible providers. The primary research question for this study was: How do Medicare-ineligible providers make sense of their experiences turning away Medicare beneficiaries and their inability to serve these clients?

Research Design and Methods

This study was executed using interpretive phenomenological analysis (IPA) to guide both data collection and analysis. The study focused on the experiences of Medicare-ineligible mental health professionals as they navigated interactions with Medicare beneficiaries who sought mental health care from them. By using a hermeneutic approach to understand their unique perspectives on this phenomenon, we aimed to remain consistent with the philosophical approach of IPA, which is idiographic in nature (Smith, Flowers, & Larkin, 2009). This study received approval from the Western Institutional Review Board.

IPA focuses on the personal meaning-making of participants who share a particular experience within a specific context (Smith et al., 2009). We determined IPA to be the most appropriate method to answer our research question because of the personal impact on LPCs of turning away Medicare beneficiaries because of Medicare-ineligible provider status. Nationally, LPCs share the experience of being unable to serve Medicare beneficiaries because of the current Medicare mental health policy that establishes these licensed mental health professionals as Medicare-ineligible. IPA also is appropriate for this study because of the positionality of the researchers. The research team consisted of two LPCs and one LMFT who have denied services or had to refer clients because of the current Medicare mental health policy and have engaged in prior research and advocacy related to the professional and clinical implications of the current Medicare mental health policy. We selected IPA for this study because of the shared experience between the researchers and participants as Medicare-ineligible providers. A distinguishing feature of IPA, a variation of hermeneutic phenomenology, is the acknowledgment of a double-interpretative, analytical process: The researchers make sense of how the participants make sense of a shared phenomenon (Smith et al., 2009).

Participants

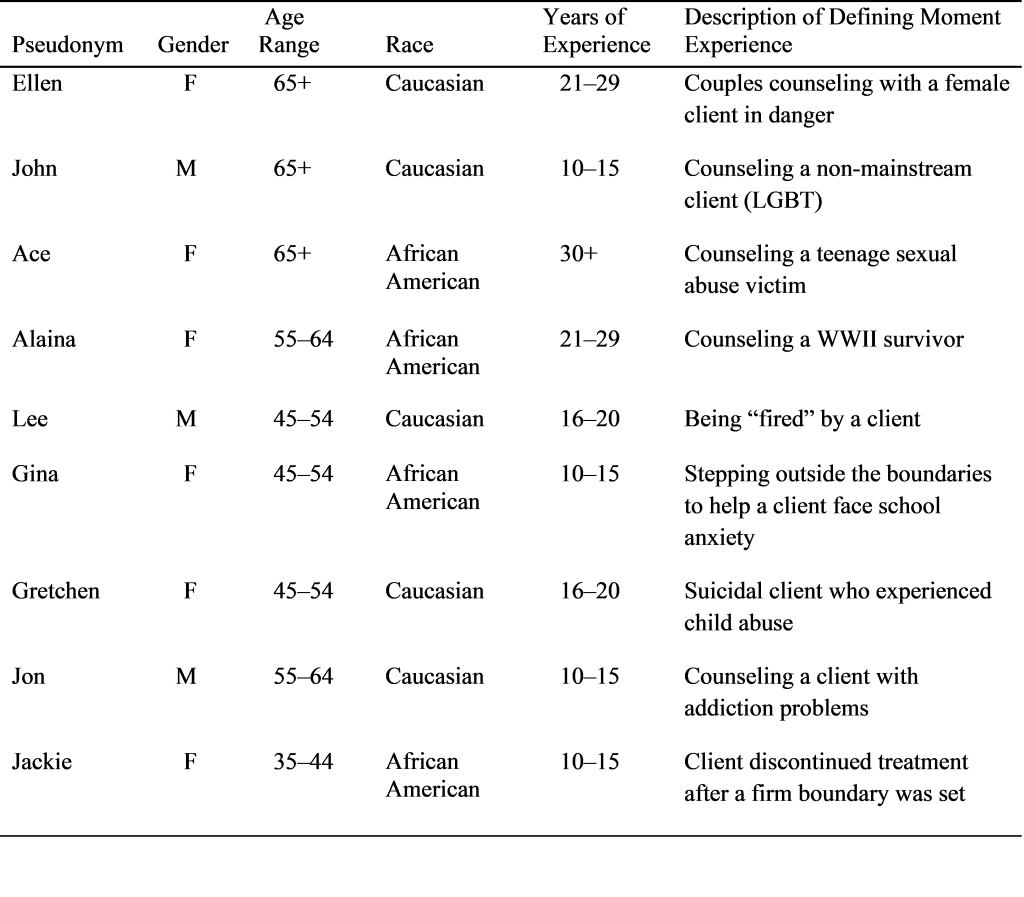

Participants were screened based on the inclusion criteria of having direct experience with turning away or referring Medicare beneficiaries and holding a mental health license as an LPC. Because states grant licenses to health care providers, we limited participation to LPCs who were practicing in a specific state in the Mid-Atlantic region. This allowed for consistency in licensure requirements, training provided, and current scope of practice across all participants. The nine participants interviewed all held the highest professional counseling license in this state, which allows these individuals to practice independent of supervision after completing 4,000 hours of supervised training. Post-license experience ranged from 6 months to 17 years, and participants practiced in both rural and non-rural settings. Pseudonyms were assigned by the research team (see Table 1 for participant information).

| Table 1

Participant Information

|

| Participant |

License Type |

Rural Statusa |

Years of Licensed Experience |

| Michelle |

LPC |

Rural |

4 years |

| Cecelia |

LPC |

Non-rural |

5 years |

| Mary |

LPC |

Non-rural |

17 years |

| Roger |

LPC |

Non-rural |

2 years |

| Aubrey |

LPC |

Rural |

4 years |

| Donna |

LPC |

Rural |

4 years |

| April |

LPC |

Non-rural |

0.5 years |

| Robert |

LPC/LMFT |

Non-rural |

22 years |

| Brandon |

LPC |

Rural |

5 years |

aThe table displays rural status as designated by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Services Administration (2016) according to the practice location of the participant. Non-rural includes metropolitan and micropolitan areas. Rural indicates any locality that is neither metropolitan or micropolitan.

Most participants were identified because of having completed a national survey of mental health providers unable to serve Medicare beneficiaries (Fullen et al., in press-a). Participants in the national survey were provided with a question in which they were able to indicate their openness to participating in follow-up individual interviews regarding their experiences with turning away clients as a result of Medicare policy. Two additional participants had not completed the national survey but were identified locally because of their unique experiences with the phenomenon under investigation. We selected nine participants in accordance with IPA participant selection and data saturation guidelines (Smith et al., 2009). Although the current Medicare policy excludes both LPCs and LMFTs, we chose to focus on the experiences of LPCs to ensure a purposive and homogeneous sample (Smith et al., 2009).

Data Collection

Semi-structured, in-depth interviews of the nine participants were conducted by the research team. All research team members are LPCs or LMFTs. Individual interviews were conducted by a single member of the team who digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim the interview procedure. Consent was obtained from the participants and pseudonyms were used to ensure participant confidentiality. Also, participants were given the option to stop the interview at any time. The elapsed time of each interview ranged between 47 and 66 minutes. The semi-structured interview protocol began with two initial questions to frame the interview: (a) Have you ever had to refer a potential client to another counselor/therapist/agency because of not being able to accept their Medicare insurance coverage? and (b) Have you ever established a working relationship with a client who later transitioned to Medicare insurance coverage?

Based on participant responses to these initial questions, two grand tour questions followed:

(a) Tell me about what typically occurs when someone with Medicare insurance contacts your office in search of counseling? and (b) Tell me about any times when you have had to alter a pre-existing working relationship with a client because of their Medicare coverage? Follow-up questions focused on the impact of current Medicare mental health policy on the interviewees, as well as their perceived impact on clients, local communities, other therapists in the area, and their employment contexts.

Data Analysis

The IPA process outlined by Smith et al. (2009) was employed to analyze the transcribed interview data. The following steps were employed throughout the analysis process: (a) reading and re-reading of transcripts, (b) initial noting, (c) developing emergent themes, (d) searching for connections across emergent themes, (e) moving to the next case, and (f) looking for patterns across cases. Codes and themes developed at each stage of the first transcript analysis required consensus agreement among the authors. After re-reading, initial noting, developing emergent themes, and clustering of superordinate themes for each of the remaining interviews, the authors proceeded to engage in a group-level analysis process of looking for patterns across all interviews. Patterns across all interviews were organized into a concept map to synthesize connections and relationships between the interviews. Connections and relationships identified through this cross-case analysis led to the identification of a group-level clustering of superordinate themes that resulted in the identification of the primary themes.

Trustworthiness

The authors attended to the credibility and trustworthiness of this analysis using four strategies. First, the authors have prolonged engagement in the fields of counseling and marriage and family therapy as licensed professionals. This prolonged engagement has allowed the authors to be situated to the contexts of the participants, account for abnormalities in the data, and transcend their own observations (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Second, the authors engaged in a team-based reflexive process through the sharing of personal reflections and group discussions about emerging issues (Barry, Britten, Barber, Bradley, & Stevenson, 1999). Third, negative case analysis was used in the analytical process of this study to develop, broaden, and confirm themes that emerged from the data (Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Patton, 1999). The fourth strategy was analyst triangulation (Denzin, 1978; Patton, 1999). All three authors participated in the development of the study, data collection, and data analysis to reduce the potential bias that can emerge from a single researcher performing each of these tasks (Patton, 1999). Each researcher independently analyzed the same data and compared their findings throughout data analysis to check selective perception and interpretive bias.

Results

Three superordinate themes emerged from our interviews with nine mental health professionals who have experience with the Medicare coverage gap: ineffectual policy, difficult transitions, and undue burden. We will discuss one superordinate theme, ineffectual policy, with the emergent themes of confounding regulations, programmatic inconsistencies, and impediment to care. By presenting a single meta-theme, we hope to provide increased depth and the nuanced experiences that our participants shared (see Levitt et al., 2018 for a discussion on dividing qualitative data into multiple manuscripts).

All nine participants expressed concerns about the ineffectiveness of current Medicare policy when it comes to treating people with mental disorders who live in their communities. The disconnect between Medicare’s intended aim—to provide sound health care to beneficiaries—and the present outcome for clients seeking out counseling led us to describe the policy as ineffectual or not producing the intended effect. Our participants perceived that the policy had severe shortcomings in terms of providing access to mental health care, which they viewed as a serious problem with cascading consequences for their clients, communities, and themselves.

Confounding Regulations

Several participants described the Medicare coverage gap as “confusing” and “frustrating” for mental health providers and Medicare beneficiaries who are seeking mental health services. Brandon, an LPC who serves as a director within a Federally Qualified Health Center, stated, “Most people are pretty shocked to realize we are not part of Medicare.” He went on to explain that most medical providers, including psychiatrists, were not aware of LPCs’ Medicare ineligibility when making client referrals. Participants described how the confusion interferes with referrals between medical providers and clients seeking mental health services.

Other participants described how frustrating the policy is, both for themselves and their clients. Robert, an LPC who also is credentialed as an LMFT, stated that “as a provider, it’s frustrating to turn people away,” and “it’s especially concerning for older people who can’t afford to pay out of pocket.” Michelle, who works as an LPC in a rural community, described how the MMHCG influences clients’ views of the larger Medicare system, stating, “[Clients are] very angry—not directed towards me, just the system . . . they’re on Medicare now [and] they have to leave. They paid into a system and then still can’t see the clinician that they want to see.” According to interviewees like Michelle, current Medicare provider regulations do not account for the preponderance of LPCs who provide care, particularly in rural communities. Regulations are then perceived by clients as an additional barrier to getting help at a time when they may be vulnerable.

In fact, in certain cases, current Medicare policy may result in all Medicare beneficiaries within a particular community losing access to mental health care. Brandon described a 4-month period when his Federally Qualified Health Center was unable to serve any Medicare beneficiaries because of job turnover: “[It] took us four months to find an LCSW. . . . We specifically had to weed out some very qualified licensed mental health professionals because they weren’t LCSWs.” Brandon went on to explain that during this 4-month period, his clients were unable to access mental health care at the community clinic. He concluded, “It was pretty disruptive to their care.”

Brandon’s description elucidates the cascading impact of the current policy on clients, community agencies that provide mental health services, and counselors seeking work. When specific providers are excluded from servicing Medicare beneficiaries, older adults with mental health conditions are vulnerable to gaps in coverage, such as the 4-month period that Brandon described.

Programmatic Inconsistencies

Several interviewees referenced confusion about how Medicare interfaces with other insurance programs. Roger and Mary, a couple in joint practice, explained how confusion among clients and health providers in their community is exacerbated by inconsistencies between Medicare and Medicaid, including the fact that in their state LPCs are eligible for reimbursement from Medicaid, but not Medicare. Roger explained, “[The] confusion is not just with clients who have low SES. It’s agency people, it’s case managers in the community, doctors that would make referrals, there really is a misunderstanding . . . and sometimes a disbelief.” They went on to describe their frustration in having to explain to referral sources that Medicare ineligibility has nothing to do with a lack of training. Roger concluded, “Yes, we are trained and . . . virtually every other insurance company accepts licensed professional counselors.”

Mary’s and Roger’s statements are indicative of the confusion that current policy creates among providers and clients. Several interviewees expressed annoyance that they had to explain to prospective clients that they possessed the requisite license and training required by the state to provide counseling and that they were recognized providers by non-Medicare insurance providers (i.e., Medicaid, Tricare, private insurance providers).