Dec 5, 2024 | Volume 14 - Issue 3

Matthew L. Nice, Arsh, Rachel A. Dingfelder, Nathan D. Faris, Jean K. Albert, Michael B. Sickels

Emerging adults (18–29 years) are at a vulnerable developmental stage for mental health issues. The counseling field has been slow to adapt to the evolving landscape of the specific needs of emerging adult clients. The purpose of this qualitative study was to investigate the experiences of professional counselors who primarily counsel emerging adult clients. Using interpretative phenomenological analysis, data was collected from 11 professional counselors to produce four major themes of their experiences working with emerging adult clients: parental pressures, self-discovery, transitions, and dating and attachment. The findings from this study provide insights regarding practices and preparation for professional counselors to work with emerging adult clients.

Keywords: emerging adults, professional counselors, experiences, phenomenological, qualitative study

Emerging adulthood (18–29 years) is a distinct human developmental stage between adolescence and adulthood. Arnett (2000) defined emerging adulthood after interviewing hundreds of young adults around the United States about their developmental experiences over several years. It is a period of life that is both theoretically and empirically different than late adolescence and early adulthood due to the psychosocial factors that young adults experience during this time in their lives (Lane, 2020). It is a time when individuals often leave their parents’ or guardians’ home, enter college or begin a career, seek romantic relationships, and begin to make decisions independently (Arnett, 2004). Emerging adults no longer experience the restrictions from their parents/guardians or teachers and they are not yet burdened with normative adult responsibilities. These freedoms allow individuals to develop qualities (e.g., self-sufficiency, new adult roles, major responsibilities) that are required during adulthood (Arnett, 2004).

As a result of this shift in human development, individuals in their twenties are marrying and starting families later, changing jobs more frequently, and pursuing higher levels of education than they were in previous decades (Arnett, 2015). Thus, the developmental factors and needs of this age group have been increasingly shifting. Although emerging adulthood is the most well-studied theory of young adult development, it is not without limitations. The most notable of these is the applicability of emerging adulthood features to young adults in all contexts. For example, the college experience offers young adults new opportunities to explore their identities and to try new things that non–college-going young adults may not experience (Mitchell & Syed, 2015). Additionally, emerging adulthood may be a Western-centric experience that young adults in other parts of the world may not experience in the same way (Hendry & Kloep, 2010).

Emerging adulthood is distinguished by its five defining features: identity exploration, sense of possibilities, self-focus, instability, and feeling in-between (Arnett, 2004, 2015). These features indicate normative developmental affordances and challenges, as well as help to define the common experiences of emerging adulthood (Nelson, 2021; Nice & Joseph, 2023). Identity exploration refers to emerging adults’ process of self-discovery in education, careers, and romantic partnerships. Sense of possibilities refers to emerging adults’ tendency to look to the future optimistically, imagining the many avenues they may take in their lives. Self-focus, not to be confused with selfishness, is the normative process in which emerging adults have the opportunity to focus on themselves without parental constraints, and before the responsibilities of marriage or parenthood. Feeling in-between is the developmental limbo between adolescence and adulthood, when emerging adults do not identify as an adolescent or an adult. Lastly, instability refers to emerging adults experiencing unstable and frequently changing life conditions, such as change in romantic partnerships, transitioning to and from college, or moving in and out of living situations (Arnett, 2015).

Experiencing these normative developmental features often results in challenges to emerging adults’ mental health (Arnett et al., 2014; Lane, 2015a; Lane et al., 2017). Navigating identity exploration and new possibilities by experimenting with anomalous life roles and experiences may lead to distress and failure (Lane, 2015b). The subjective experience of not feeling salient in adulthood but being tasked with new adult responsibilities that were not present in adolescence may cause periods of identity crisis and various psychological difficulties (Lane et al., 2017; Weiss et al., 2012). The various transitions such as entering and leaving college, starting and ending careers, or moving out of the house of a parent/guardian and moving in with roommates or living alone may contribute to instabilities and significant distress (Murphy et al., 2010; Nice & Joseph, 2023). Additionally, the salience of emerging adults’ cultural identities affects the ways in which they experience satisfaction with their lives (Nice, 2024). Although not every emerging adult will experience all of these difficulties (Buhl, 2007), many will respond with significant distress that may affect the critical juncture in mental health development that occurs during the emerging adulthood years (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2022; Lane, 2015a). The mental health needs of emerging adults is often overlooked, as society may only see the opportunities for new growth, fun, freedom, and promise of being a young adult, and may overlook the instabilities and distress that accompany this developmental period (C. Smith et al., 2011).

Although emerging adults are some of the most vulnerable of the age groups for developing mental health issues (Cheng et al., 2015), including being particularly prone to anxiety and depression (American College Health Association, 2019), the counseling field has been slow to adapt to the evolving landscape of these individuals. Many counselors are challenged with using outdated developmental models to conceptualize their work with emerging adult clients that do not adequately address the nuances within this age group (Lane, 2015a). During high school years, school counselors are often tasked with prioritizing students for college and career readiness, but not for their upcoming transition into emerging adults (Nice et al., 2023). Given these circumstances, counselors who work with emerging adult clients are uniquely positioned to foster resilience, wellness, and navigation of various challenges during this often tumultuous stage of human development (Lane, 2015a). Understanding the experiences of professional counselors who work primarily with emerging adult clients may be necessary to assess the unique needs and support that emerging adult clients can benefit from in the counseling setting. Although other studies have examined the lived experiences of counselors working with specific clients (e.g., Wanzer et al., 2021) and other phenomena (Coll et al., 2019), no studies have examined counselors’ experiences working with emerging adults.

Given that there is little systematic research exploring how counselors experience working with emerging adult clients, qualitative research is a warranted methodological approach to understanding these social phenomena. Conceptualizing this study using the theoretical lens of emerging adulthood (Arnett, 2000, 2004, 2015) and its five features can assist in exploring the experiences of counseling emerging adults through a developmental perspective that accounts for the current circumstances of young adults. The present research addresses this by investigating the following research question: What are the perspectives and experiences of professional counselors working with emerging adult clients?

Method

The present qualitative study used interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) by collecting data through semi-structured interviews. The IPA approach was selected as the methodology for this study in order to reveal the experiences of counselors working with emerging adult clients because it permits an abundant level of data collection and interpretation and allows for consideration of participant accounts within a broader context/theory (Hays & Singh, 2023). During the interviews, participants were given the opportunity to discuss their experiences of working with emerging adult clients in order to give voice to their thoughts, beliefs, and attitudes surrounding these experiences.

Research Team and Reflexivity

The research team consisted of the first author and principal investigator, Matthew L. Nice; four research assistants, Arsh, Rachel A. Dingfelder, Nathan D. Faris, and Jean K. Albert; and an external auditor, Michael B. Sickels. Nice holds a PhD in counselor education and supervision and has studied and worked with emerging adults in various settings. Albert is a doctoral student in a counselor education and supervision program who has worked with emerging adults in a clinical setting. Arsh, Dingfelder, and Faris were master’s students at the time of this study who were enrolled in a clinical mental health counseling program and who indicated interest in counseling emerging adults after graduation. Arsh and Faris identified as emerging adults. Sickels served as the external auditor and is a counselor educator who holds a PhD in counselor education and supervision and has several years of clinical experience counseling emerging adult clients. Nice pursued this study as part of a research agenda that includes emerging adulthood mental health. Arsh, Dingfelder, Faris, and Albert were research assistants who worked on this study because they had communicated interest in collaborating on this topic and as part of their paid graduate assistantships. Both prior to and throughout the study, these research assistants were trained on the qualitative research process, conducting qualitative interviews, and data analysis.

We engaged in bracketing to minimize the ways in which our experiences, expectations, or any potential biases might influence the study. We discussed our experiences in relation to being or having been an emerging adult, our roles as scholars who have researched emerging adults and clinicians who have counseled emerging adults, and our overall commitment to the counseling profession. During these discussions we identified our experiences, acknowledged any biases that we may have had, and talked about ways to bracket while conducting interviews. We kept analytic memos and personal notes during the data collection and coding process. Sickels examined our reflexivity in relation to data collection and coding to provide us with critical feedback.

Participants

This study consisted of a purposive criteria sample of 11 professional counselors who met the following criteria: graduation from a CACREP-accredited counseling program, a minimum of 2 years of professional counseling experience post-graduation, and a full-time caseload of at least 60% or more emerging adults (ages 18–29) during their time as a professional counselor. Demographic data for each participant are displayed in Table 1. Pseudonyms are used for each counselor selected for the study to maintain confidentiality (American Counseling Association [ACA], 2014), along with their age, gender, race/ethnicity, highest counseling degree, years of experience as a counselor, and the type of work setting. We chose to require 2 years of counseling experience as inclusion criteria given that most states require no less than 2 years of experience to become a fully licensed professional counselor (e.g., Pennsylvania Department of State, 2024), which is a benchmark of demonstrating experience as a professional counselor. We chose not to require that participants hold licensure as a professional counselor, as we hoped to include college counselors in our study, many of whom may not seek licensure as a professional counselor, as many universities do not require counselors to hold licensure to work in counseling centers. We elected to require a full-time caseload of at least 60% of clients currently within the ages of 18–29 years to ensure that the experiences of the counselors working with this age group were substantial enough to provide generalizability.

Table 1

Participant Demographics

| Pseudonym |

Age |

Gender |

Race/Ethnicity |

Education |

Total years as a professional counselor |

Type of practice |

| Judy |

30 |

Female |

White |

MA |

5 |

Private practice |

| Lorraine |

31 |

Female |

White |

PhD |

8 |

Private practice |

| Peter |

48 |

Male |

White |

MA |

10 |

College counseling center |

| Claire |

40 |

Female |

White |

MA |

16 |

Private practice |

| Christine |

30 |

Female |

White |

MA |

5 |

College counseling center |

| Patricia |

48 |

Female |

White |

MA |

20 |

College counseling center |

| Mark |

32 |

Male |

White |

PhD |

7 |

College counseling center |

| Theresa |

30 |

Female |

White |

MA |

5 |

Outpatient practice agency |

| Emily |

39 |

Female |

White |

MA |

2 |

College counseling center |

| Stephen |

37 |

Male |

Asian |

MA |

7 |

Community mental health |

| Sarah |

27 |

Female |

Hispanic |

MA |

3.5 |

Outpatient agency & private practice |

Note. N = 11.

Procedures and Data Collection

After we obtained university Institutional Review Board approval, participants were invited to participate through convenience sampling from agencies, private practices, and university counseling centers in the northeast region of the United States. We also searched online counselor directories for counselors who fit the criteria of our study. Upon completing interviews, we also recruited participants via snowball sampling by asking initial participants for recommendations for new potential participants to interview who also met our inclusion criteria. Given that many college counselors’ clients are almost all within the emerging adult age range, they served as valuable participants in our data collection. However, these counselors only see clients in the college context and do not see non-college emerging adult clients, an important and often forgotten population of emerging adults (Nice & Joseph, 2023). To assure the study focused on professional counselors, we limited our participants who worked in college counseling centers to account for less than half of our total participants (n = 5).

Interview questions were developed by the research team by first examining the extant counseling and young and emerging adulthood literature. Nice developed questions grounded by the literature and sent the questions to the research team for their suggestions, additions, and edits. The interview questions approved by the research team were sent to Sickels, who provided feedback for creating the final interview protocol. Prior to interviews, participants signed a consent form and completed a demographics questionnaire. Participants were also provided with a document outlining the five features of emerging adulthood (Arnett, 2004, 2015) that they were asked to review prior to the interview in order to better understand and answer the interview questions pertaining to these features. We conducted semi-structured interviews lasting approximately 60 minutes via Zoom over an 8-month span. Participants were offered a $20 electronic gift card as an incentive for participation. At the start of each interview, participants were reminded that questions pertaining to their clients only pertained to their emerging adult–aged clients, within the years of 18 to 29, and not any clients outside of that age range. Each interview consisted of eight open-ended questions (see Table 2). Participants were also asked follow-up questions for clarification. These questions were guided by Arnett’s (2000) theory of emerging adulthood, a well-studied and accepted understanding of the developmental markers and features that individuals experience during young adult development.

To understand participants’ experiences of counseling young adults during this developmental phase, we asked several questions pertaining to their experience of their clients’ developmental features of emerging adulthood (i.e., identity exploration, sense of possibilities, self-focus, instability, and feeling in-between) in counseling sessions. For consistency across participants, we asked each interview question in the same order during each interview (Creswell & Creswell, 2017). The pace of each interview was determined by the participant to allow for the development of richer data (Hays & Singh, 2023), with impromptu questions asked between established questions when elaboration was needed.

Table 2

Interview Questions

| Question Number |

|

Question Content |

| 1 |

|

What is your process for working with emerging adult clients? |

| 1a |

|

Why do you choose to work with this population? |

| 2 |

|

What developmental considerations do you make when working with emerging adult clients? |

| 2a |

|

Can you provide an example or case using developmental considerations working with emerging adult clients? |

| 3 |

|

To what extent does clients’ “identity exploration” factor into your counseling of emerging adult clients? |

| 4 |

|

To what extent does clients’ “sense of possibilities” factor into your counseling of emerging adult clients? |

| 5 |

|

To what extent does clients’ “feeling in-between” factor into your counseling of emerging adult clients? |

| 6 |

|

To what extent does clients’ “instability” factor into your counseling of emerging adult clients? |

| 7 |

|

To what extent does clients’ “self-focus” factor into your counseling of emerging adult clients? |

| 8 |

|

When you look back on the process of counseling emerging adults, what other thoughts stand out which we have not discussed about the outcomes of counseling emerging adult clients? |

| 8a |

|

How have those implications affected the outcome of the counseling process with emerging adult clients? |

| 8b |

|

How did you respond to these outcomes as a counselor? |

To enhance the trustworthiness, credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability of the data, we enlisted several procedures during data collection (Morrow, 2005; Prosek & Gibson, 2021). Field notes, researcher observations, and experiences pertaining to each interview were expressed and processed during research team meetings, which assisted in triangulation of data by confirming interpretations of interview data (Anney, 2015). Nice used member checking by sending each participant documents that outlined summaries of the emergent findings, quotes, themes, and data (Flynn & Korcuska, 2018). Of the 11 participants, 10 responded to member checking by confirming the accuracy of the documents to the best of their knowledge or suggesting new thoughts or ideas regarding the documents. To establish the confirmability of findings, analytic memos and a reflexivity journal were used to assist with objectivity in the interpretations during data analysis (Saldaña, 2021). Analytic memos were also kept to record thoughts around the meaning behind participants’ statements.

Nice used a reflexivity journal throughout the interviews and data analysis processes and made efforts to bracket assumptions as a professional in the counseling field (Hays & Singh, 2023). The purposive sampling method of clients based on their experiences of counseling emerging adults assisted in establishing transferability of the findings of the study (Anney, 2015). The trustworthiness and dependability of the study was assisted using an external auditor and peer briefer. Sickels served as the auditor throughout the study, reviewing interview transcripts, data collection, data analysis, themes, and overall processes, procedures, and coherence of the study (Flynn & Korcuska, 2018; Hays & Singh, 2023). Nice and Sickels met face-to-face or by phone to engage in peer-debriefing during all major points of the study, including Nice’s positionality, thoughts, emotions, and reactions to the procedures of the study.

Data Analysis

Data was analyzed by following Pietkiewicz and Smith’s (2014) guidelines of data analysis. The process involves three stages: immersion, transformation, and connection. This process began with Nice listening to recordings of each interview to review the content as a whole and to mark any additional observations. Nice and the research team manually transcribed each interview. All transcribed interviews were reviewed by Nice concurrently with recordings to ensure accuracy of the transcripts and to create a deeper immersion into the data. During this process any new insights or observations were recorded in field notes and a reflexivity journal (Pietkiewicz & Smith, 2014). The rest of the research team also engaged in this three-stage process by reviewing each team member’s recordings and processing them in team meetings. Research team members participated in consensus coding team meetings after every two or three interviews, resulting in a total of five meetings. Prior to meetings team members all examined the materials for coding and submitted them to Nice. During meetings Nice led the discussions about each participant interview and the research team discussed how and why they arrived at specific codes. Intercoder reliability was maintained by Sickels, who examined each initial coding from all research members as well as the coding results from consensus coding meetings (Cofie et al., 2022).

Following IPA qualitative methodology, Nice and the research team reviewed and interpreted their notes regarding the transcripts in order to transform them into emergent themes using both hand coding and ATLAS.ti coding software (J. A. Smith, 2024). These initial themes were linked together by their conceptual similarities, which developed a thematic hierarchy (Pietkiewicz & Smith, 2014). Finally, Nice and the research team created a narrative account of each theme, which included direct quotes from the participants. The interpretations of these emergent themes and the overall interview content were reviewed by Nice and the research team in order to reach agreement on the final, distinct themes. Afterward, Sickels conducted an independent cross-analysis on the interview transcripts, notes, and emergent and final themes to ensure the accuracy and clarity of the final themes.

Results

The data analysis process using IPA qualitative methods resulted in four distinct themes. These themes were identified and designated based on the meaning related with professional counselors’ experiences working with emerging adult clients. It should be noted that anxiety/stress was initially considered as a fifth theme; however, further coding and team meetings concluded that anxiety/stress is grounded within the other four themes and was not an independent distinct theme. Hence, the following four phenomenological themes emerged: parental pressures, self-discovery, transitions, and dating and attachment. The results of this interpretative phenomenological study are outlined in the following section.

Theme 1: Parental Pressures

This theme indicates the expectations, criticisms, and imposed beliefs that emerging adult clients often process in the counseling session. Participants expressed that much of their experiences counseling emerging adult clients involved working on their clients’ relationship with their parents. Within this theme, participants expressed that their clients struggle with meeting their parents’ expectations, criticisms, standards, and imposed beliefs. Sarah shared:

A lot of people, whether they had good or bad relationships with their families, are learning how that looks now in their adulthood, like how they incorporate their family. So like creating more boundaries and what not, boundaries is a huge thing for this.

Mark asserted: “Parents are always into the stuff [emerging adult clients] are doing and criticizing it, saying ‘no, do this or that instead.’ I think it pushes them into feeling like they are still this adolescent or kid.” Additionally, Stephen mentioned: “Clients might be going through, let’s say, gender identity. There’s this rejection of themselves from their parents when they were younger, and they struggle exploring who they want to be, because they were never fully accepted by their parents.” Participants largely expressed that although their emerging adult clients are adults, their parents still have a profound effect on them and what they bring to counseling sessions. Counselors experiencing their clients navigating their parental relationships is likely due to the individuation process (Youniss & Smollar, 1985). Individuation is an age-normative co-constructed process occurring in emerging adulthood in which young adults redefine their relationship with their parents after transitioning into emerging adulthood (Zupančič & Kavčič, 2014). This process often involves young adults’ fear of disappointing, seeking approval, and navigating parent intrusiveness (Nice & Joseph, 2023).

Theme 2: Self-Discovery

The theme self-discovery refers to counselors’ experiences of assisting emerging adult clients in finding who they are, how they fit into society, and their exploration of being an adult. Judy expressed:

I just recognize that there’s a really great impact for folks during these [emerging adult] years to explore themselves and really get to know who they are, but in a space that feels comfortable and accepting. And, hey, however, you want to show up to session, you know that the counselor there has got your back.

Similarly, Emily stated: “You know [emerging adult clients] are trying these identities possibilities on for size, you know, I could be this! What would that feel like? What would that be like?” Claire also had similar experiences working with emerging adult clients. She expressed:

Finding who they are is probably the biggest type of stress that I see [as a professional counselor]. What does it mean to be by myself? What does it mean to be outside of a family? What does it mean to be alone and not alone? But you know just kind of out there in the world.

This theme likely speaks to the features of emerging adulthood, namely identity exploration and instability (Arnett, 2000, 2004). Exploring identities can be a stressful time for young adults, especially when some identities are marginalized (Pender et al., 2023). Participants expressed the importance of being a stable and safe place for clients as they explore who they are, who they want to be, and their place in society.

Theme 3: Transitions

This theme highlights the worry and indecisiveness emerging adult clients struggle with as they transition to their new roles. Based on their experiences focusing on the transitions of emerging adult clients in therapy, participants identified and articulated the stressors and challenges to mental health experienced by clients facing frequent transitions. To this point, Theresa noted:

So there’s a lot of transitions that are happening within young adulthood that I find really helpful to not only manage within therapy, but just to help clients better understand themselves. It’s such a pivotal time to really test out the way in which they’re experiencing the world.

Judy also experienced how transitions can be difficult with some of her emerging adult clients. She shared: “I had some [emerging adult clients] who have not had a traumatic background, but the instability and chaos of all these changes and transitions really threw them for a loop.” Christine noted some specific transitions she sees in her emerging adult clients:

There’s a lot of like hopping around with sort of short timelines, especially if they’re not living at home. Their room, their dorm, their apartment, whatever it is, is changing every year. A lot of students are transferring in or transferring to other schools. Their jobs are changing. They’re getting internships. Their classes are different every semester. And so the entire emerging adult experience is pretty much based on some level of instability with transitions . . . that plays into the work that I do, because I’m trying to give them a place that is stable and consistent, and somewhere that they can go and feel safe and comfortable.

The frequent transitions and changes that occur in emerging adulthood often lead to instability and distress (Howard et al., 2010). Participants noted these transitions, their role in assisting clients with these transitions during emerging adulthood, and the importance of the counseling session providing clients with stability that they may not be receiving in other areas of their lives.

Theme 4: Dating and Attachment

This theme signifies the instability of romantic relationships and learning healthy attachment styles that emerging adult clients bring to the counseling session. When discussing some of the most prevalent concerns emerging adult clients bring to counseling sessions, Lorraine indicated:

Dating is an interesting time in early adulthood. So I pay attention to that and I spend a lot of time on psychoeducation, paying attention to healthy, unhealthy attachment styles, unhealthy and healthy relationship characteristics, and what people would identify as like red flags. And then going into attachment styles and how they’re attaching to others is serving them or not serving them.

On that note, Christine discussed a specific emerging adult client she is working with:

Someone I’m working with now is going through a breakup. She was with the same person for the past 3 years, and it recently ended. And so, a lot of the work that we’re doing now is processing who she is apart from the relationship and doing so in a way that feels safe for her.

Mark identified similar experiences working with emerging adult clients:

[Emerging adult clients say] “my dating relationships are nonexistent. So now I feel that I don’t have any worth because I know I can’t take somebody out on a date or go to the movies or whatever.” So I think that plays a huge role because it’s almost like something that clients that I work with experience. . . . like everything is just not stable.

Dating and navigating romantic relationships in therapy has been widely researched in counseling scholarship (Feiring et al., 2018). Exploring these concepts with emerging adults in therapy may be especially crucial given that emerging adulthood is the formative stage in which individuals explore romantic relationships (Shulman & Connolly, 2013). Participants indicated that they process healthy and unhealthy attachment styles with clients as they navigate dating, which may be significant given the effects of emerging adults’ attachment styles on their overall mental health (Riva Crugnola et al., 2021).

Discussion

Eleven professional counselors provided insight into their experiences and perceptions working with emerging adult clients in this study. Four phenomenological themes—parental pressures, self-discovery, transitions, and dating and attachment—were derived from participants’ perspectives. These findings support the available literature on the mental health needs of emerging adults (e.g., Cheng et al., 2015; Lane, 2015a) and extend this knowledge with increased direction.

The results of this study supported Arnett’s (2000, 2004, 2015) theory of emerging adulthood. Participants reported that their clients experience stress and anxiety from age-normative developmental experiences. The transitions and dating stress that emerging adults process in counseling can be linked to the emerging adulthood feature of instability (Arnett, 2004). The stress of self-discovery that is present in emerging adults’ counseling sessions is related to the emerging adulthood features of identity exploration, sense of possibilities, self-focus, and feeling in-between (Arnett, 2004). The parental pressure that counselors expressed are often prevalent when counseling emerging adults is consistent with individuation in emerging adulthood (Youniss & Smollar, 1985). Komidar and colleagues (2016) found that emerging adults often experience both a fear of disappointing their parents and feelings of parental intrusiveness in their lives while traversing the individuation process of redefining the parent–child relationship during emerging adulthood. The parental pressures that emerging adults process in counseling sessions is likely due to emerging adults individuating by establishing their own independence while sustaining a healthy level of connectedness with their parents (Nice & Joseph, 2023).

Participants’ experiences of their emerging adult clients expressing issues related to pressures from their parents stem from many contexts. These pressures came from parents exerting their expectations for their emerging adult children to choose specific education and careers and to perform well in them. Although emerging adults have newly entered adulthood and can explore their own belief systems, counselors still experienced their emerging adult clients feeling pressured to conform to the beliefs that their parents imposed on them. Emerging adult clients who were not meeting the specific expectations of their parents often expressed stress and anxiety from criticisms they received from their parents. These experiences are not to be confused with poor parenting. Mark reported that many parents are “helicopter parents” (Padilla-Walker & Nelson, 2012) who are overly involved in their emerging adult children’s lives; this increased involvement often results in their children experiencing stress and pressures.

The self-discovery that participants experienced their emerging adult clients undergoing was related to emerging adults not only determining who they are, but who they want to be. Given that individuals may not feel comfortable exploring their identities in the high school setting (Palkki & Caldwell, 2018), emerging adulthood may serve as a safer time for young adults to explore who they are. Discovering who they are is a formative task that is often met with much stress and instability (Arnett, 2004). Participants found that emerging adult clients often experience stress and anxiety about learning what they want in terms of careers, jobs, family roles, and communities.

Several participants used the word “scared” when describing how their emerging adult clients express their feelings about the many transitions they experience. Counselors noted that their emerging adult clients are facing many transitions, such as entering and leaving college, entering and leaving jobs, moving out of their parents’ home, moving in with roommates or romantic partners, and changing friend groups. With these transitions, counselors reported that their clients expressed a level of indecisiveness in knowing if they are following the correct path. Many of these transitions come with an increased level of new independence that counselors noted their clients had difficulty navigating. In line with prior research (Leipold et al., 2019), counselors expressed that promoting resilience and fostering coping methods during these transitions is beneficial to establishing consistency, safety, and security for emerging adults in counseling sessions.

Internet dating applications have led to emerging adults being more aware of the characteristics and criteria for who they want to date (Sprecher et al., 2019). Participants expressed that emerging adults often feel distress from the ending of relationships, conflicts with romantic partners, navigating who they want to date, and traversing internet dating applications. Several participants mentioned that their emerging adult clients’ self-worth was tied to their relationship status or who they are in a relationship. Participants reported that their clients’ attachment styles often lead to issues in dating. Participants noted that in their experiences, psychoeducation about healthy dating and attachment is often necessary to assist clients with these issues in the counseling session.

Implications for Counselor Practice and Training

The findings from this study provide valuable insights regarding counselors’ clinical experiences with emerging adult clients with several practice implications. Professional counselors can benefit from understanding the roles that emerging adults’ parental pressures, self-discovery, transitions, and dating and attachment have on their mental health. Counselors can benefit from asking about these four themes during the beginning of the counseling relationship to build rapport and immediately assist emerging adult clients with common developmental issues experienced by these clients.

To assist emerging adult clients with negative feelings regarding parental pressures, counselors can offer clients the opportunity to bring their parent(s) to therapy. Marriage and family counselors can also intentionally address and process parental pressures in applicable family systems. Attending to emerging adult clients’ issues surrounding self-discovery has potential implications for multicultural and social justice counseling (Ratts et al., 2016). For example, emerging adult clients who identify as gender diverse or as a sexual minority may be discovering themselves in new ways that can elicit transprejudice, discrimination, and stigmatization in society (Wanzer et al., 2021). Utilizing the Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies (MSJCCs; Ratts et al., 2016) in the counseling session provides a framework for emerging adults who are discovering and exploring their cultural identities (Nice, 2024). Counselors can use the MSJCCs to understand emerging adults’ specific intersections of their identities (e.g., race/ethnicity, sexual identity, gender identity, spirituality).

Counselors can assist clients with feelings of distress regarding self-discovery, identity, and fitting in by normalizing these developmental experiences and processing their values and life desires. Regarding transitions, counselors should be intentional to assure that the counseling session is a safe and stable environment for emerging adult clients. Given the stress and instability during emerging adulthood from frequently changing contexts in college, jobs, families, friends, romantic partnerships, and living situations, assuring that the counseling session remains stable and safe can provide clients with a sense of ease and security that they may be lacking in other areas of their lives.

Addressing dating and attachment in emerging adulthood can prove to be a difficult task, as some emerging adults may be seeking monogamous relationships while others may be more interested in hooking up or casual, no-strings-attached sexual encounters that are increasingly common during emerging adulthood (Stinson, 2010). Meeting clients where they are in terms of dating can be beneficial to supporting them in their specific needs. Given the relationship between dating and self-worth (Park et al., 2011), counselors may benefit from counseling modalities such as cognitive behavioral therapy to assist clients with cognitive distortions and feelings surrounding dating and their worth. Regarding attachment, counselors can consider using attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969) with emerging adult clients struggling with their attachment types in romantic relationships.

Lastly, findings demonstrated that counselors encounter unique developmental issues when counseling emerging adult clients. It may be beneficial for counselors to be instructed on these unique needs of emerging adult clients during their counselor education programs, given the vulnerability of this age group to mental health difficulties, and the needs that participants reported (Cheng et al., 2015). Counselor educators can implement case studies surrounding emerging adult clients struggling with parental pressures, self-discovery, transitions, and dating and attachment to prepare them for real-world scenarios that they are likely to encounter while working with this population. Information on Erikson’s (1968) stages of development, specifically aspects of identity achievement versus role confusion, can align with instruction on emerging adulthood. Counselor educators should also acknowledge that the majority of counselors-in-training may be within the emerging adulthood age range and consider developmental implications for these students during instruction and mentorship (Nice & Branthoover, 2024). The Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP; 2023) standards highlight lifespan development as a foundational counseling curriculum, with lifespan development standards addressing: “1. theories of individual and family development across the lifespan” and “7. models of resilience, optimal development, and wellness in individuals and families across the lifespan.” Counselor education should include training on the unique developmental needs and issues of emerging adulthood such as the themes found within this study in order to assist in meeting these standards.

Limitations and Future Research

Given the subjective nature of qualitative research, we implemented multiple measures of trustworthiness to account for our influence and positionality on this study. Regardless, our influence should still be considered a limitation of this study (Hays et al., 2016). Although we limited the total number of professional counselors working in college counseling centers to less than half of the total sample (n = 5), those participants only experienced emerging adults within the college context and could not speak to experiences of counseling emerging adults who have never attended college, an understudied population of young adults (Seiffge-Krenke et al., 2013). The semi-structured interviews were grounded in emerging adulthood theory and asked specifically about the five features of emerging adulthood. These questions may have influenced participants’ thoughts and feelings about their experiences with this population and affected the overall findings of the study. Finally, some members of our research team were master’s students who did not have doctoral-level research design and qualitative research classes or training. To combat this limitation, several steps were taken to assure the research team members were appropriately trained for their participation in this study, such as online trainings, training from Nice, reflexivity journals, and numerous research team meetings between interviews.

The findings from the present study suggest future investigation concerning the practices for counseling emerging adults is warranted. Whereas this study provides a distinct contribution to the professional counseling and emerging adulthood literature, studies can use these findings to explore future methods for counseling emerging adults. Given that the present study is a phenomenological examination of counselors’ experiences of counseling emerging adults, future studies should use a grounded theory methodology to generate the best practices for working with emerging adults in therapy. Interviews from both professional counselors and emerging adults currently in counseling would assist in providing a complete perspective of the needs for emerging adults in therapy.

Quantitatively, the four themes from this study can be examined in relation to stress, anxiety, wellness, and life satisfaction in order to understand the levels of distress these factors have on the mental health of emerging adults. For example, survey research seeking to understand emerging adults’ levels of stress and wellness can include the Revised Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Busby et al., 1995) and the Short Version of the Individuation Test for Emerging Adults (Komidar et al., 2016) to examine dating and attachment (i.e., Theme 4) and parental relationships and pressures (i.e., Theme 1) in relation to stress and wellness scales.

Conclusion

Counseling with emerging adult clients presents professional counselors with a unique task that includes important developmental implications to address. Consistent with emerging adulthood theory (Arnett, 2000, 2004), counselors experienced their emerging adult clients demonstrating high levels of stress and anxiety from developmental phenomena exclusive to this age range. Specifically, counselors experienced their emerging adults consistently bringing issues to counseling sessions related to parental pressures, self-discovery, transitions, and dating and attachment. Applying these insights derived from professional counselors’ experiences of counseling emerging adult clients in clinical settings and counselor education training programs can support counselors to better serve the specific needs of this frequently served population and, consequently, better address the mental health of emerging adults in therapy.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

American College Health Association. (2019). National college health assessment II reference group executive summary Spring 2019.

American Counseling Association. (2014). ACA code of ethics. https://bit.ly/acacodeofethics

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

Anney, V. N. (2015). Ensuring the quality of the findings of qualitative research: Looking at trustworthiness criteria. Journal of Emerging Trends in Educational Research and Policy Studies, 5(2), 272–281. https://bit.ly/Anney_truthworthiness

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469

Arnett, J. J. (2004). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties (1st ed.). Oxford University Press.

Arnett, J. J. (2015). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Arnett, J. J., Žukauskienė, R., & Sugimura, K. (2014). The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18–29 years: Implications for mental health. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(7), 569–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00080-7

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss, Vol. 1: Attachment. Random House.

Buhl, H. M. (2007). Well-being and the child-parent relationship at the transition from university to work life. Journal of Adolescent Research, 22(5), 550–571. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558407305415

Busby, D. M., Christensen, C., Crane, D. R., & Larson, J. H. (1995). A revision of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale for use with distressed and nondistressed couples: Construct hierarchy and multidimensional scales. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 21(3), 289–308. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.1995.tb00163.x

Cheng, H.-L., McDermott, R. C., & Lopez, F. G. (2015). Mental health, self-stigma, and help-seeking intentions among emerging adults: An attachment perspective. The Counseling Psychologist, 43(3), 463–487. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000014568203

Cofie, N., Braund, H., & Dalgarno, N. (2022). Eight ways to get a grip on intercoder reliability using qualitative-based measures. Canadian Medical Education Journal, 13(2), 73–76. https://doi.org/10.36834/cmej.72504

Coll, D. M., Johnson, C. F., Williams, C. U., & Halloran, M. J. (2019). Defining moment experiences of professional counselors: A phenomenological investigation. The Professional Counselor, 9(2), 142–155. https://doi.org/10.15241/dmc.9.2.142

Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2023). 2024 CACREP standards. https://www.cacrep.org/for-programs/2024-cacrep-standards

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). SAGE.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. W. W. Norton.

Feiring, C., Simon, V. A., & Markus, J. (2018). Narratives about specific romantic conflicts: Gender and associations with conflict beliefs and strategies. Journal of Counseling & Development, 96(3), 254–266. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12200

Flynn, S. V., & Korcuska, J. S. (2018). Credible phenomenological research: A mixed-methods study. Counselor Education and Supervision, 57(1), 34–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12092

Hays, D. G., & Singh, A. A. (2023). Qualitative research in education and social sciences (2nd ed.). Cognella Academic Publishing.

Hays, D. G., Wood, C., Dahl, H., & Kirk-Jenkins, A. (2016). Methodological rigor in Journal of Counseling & Development qualitative research articles: A 15-year review. Journal of Counseling & Development, 94(2), 172–183. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12074

Hendry, L. B., & Kloep, M. (2010). How universal is emerging adulthood? An empirical example. Journal of Youth Studies, 13(2), 169–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676260903295067

Howard, A. L., Galambos, N. L., & Krahn, H. J. (2010). Paths to success in young adulthood from mental health and life transitions in emerging adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 34(6), 538–546. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025410365803

Komidar, L., Zupančič, M., Puklek Levpušček, M., & Bjornsen, C. A. (2016). Development of the Short Version of the Individuation Test for Emerging Adults (ITEA–S) and its measurement invariance across Slovene and U.S. emerging adults. Journal of Personality Assessment, 98(6), 626–639.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2016.1171231

Lane, J. A. (2015a). Counseling emerging adults in transition: Practical applications of attachment and social support research. The Professional Counselor, 5(1), 30–42. https://doi.org/10.15241/jal.5.1.30

Lane, J. A. (2015b). The imposter phenomenon among emerging adults transitioning into professional life: Developing a grounded theory. Adultspan Journal, 14(2), 114–128. https://doi.org/10.1002/adsp.12009

Lane, J. A. (2020). Attachment, ego resilience, emerging adulthood, social resources, and well-being among traditional-aged college students. The Professional Counselor, 10(2), 157–169. https://doi.org/10.15241/jal.10.2.157

Lane, J. A., Leibert, T. W., & Goka-Dubose, E. (2017). The impact of life transition on emerging adult attachment, social support, and well-being: A multiple-group comparison. Journal of Counseling & Development, 95(4), 378–388. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12153

Leipold, B., Munz, M., & Michéle-Malkowsky, A. (2019). Coping and resilience in the transition to adulthood. Emerging Adulthood, 7(1), 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696817752950

Mitchell, L. L., & Syed, M. (2015). Does college matter for emerging adulthood? Comparing developmental trajectories of educational groups. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(1), 2012–2027. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0330-0

Morrow, S. L. (2005). Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative research in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 250–260. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.250

Murphy, K. A., Blustein, D. L., Bohlig, A. J., & Platt, M. G. (2010). The college-to-career transition: An exploration of emerging adulthood. Journal of Counseling & Development, 88(2), 174–181. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00006.x

Nelson, L. J. (2021). The theory of emerging adulthood 20 years later: A look at where it has taken us, what we know now, and where we need to go. Emerging Adulthood, 9(3), 179–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696820950884286

Nice, M. L. (2024). Exploring the relationships and differences of cultural identity salience, life satisfaction, and cultural demographics among emerging adults. Adultspan Journal, 23(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.33470/2161-0029.1158

Nice, M. L., & Branthoover, H. (2024). Wellness and the features of emerging adulthood as predictors of counseling leadership behaviors among counselors-in-training. Journal of Counselor Leadership and Advocacy, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/2326716X.2024.2361092

Nice, M. L., & Joseph, M. (2023). The features of emerging adulthood and individuation: Relations and differences by college-going status, age, and living situation. Emerging Adulthood, 11(2), 271–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/21676968221116545

Nice, M. L., Potter, P., & Hecht, C. L. (2023). The role of school counselors in preparing students for the developmental transition from adolescence to emerging adulthood. Journal of Child and Adolescent Counseling, 9(3), 260–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/23727810.2023.2183798

Padilla-Walker, L. M., & Nelson, L. J. (2012). Black hawk down?: Establishing helicopter parenting as a distinct construct from other forms of parental control during emerging adulthood. Journal of Adolescence, 35(5), 1177–1190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.03.007

Palkki, J., & Caldwell, P. (2018). “We are often invisible”: A survey on safe space for LGBTQ students in secondary school choral programs. Research Studies in Music Education, 40(1), 28–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103X17734973

Park, L. E., Sanchez, D. T., & Brynildsen, K. (2011). Maladaptive responses to relationship dissolution: The role of relationship contingent self-worth. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41(7), 1749–1773. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2011.00769.x

Pender, K. N., Hope, E. C., & Sondel, B. (2023). Reclaiming “Mydentity”: Counterstorytelling to challenge injustice for racially and economically marginalized emerging adults. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 33(2), 300–312. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2662

Pennsylvania Department of State. (2024). Social workers, marriage and family therapists and professional counselors licensure guide. https://www.pa.gov/en/agencies/dos/resources/professional-licensing-resources/licensure-processing-guides-and-timelines/social-workers-guide.html

Pietkiewicz, I., & Smith, J. A. (2014). A practical guide to using interpretative phenomenological analysis in qualitative research psychology. Psychological Journal, 20(1), 7–14.

Prosek, E. A., & Gibson, D. M. (2021). Promoting rigorous research by examining lived experiences: A review of four qualitative traditions. Journal of Counseling & Development, 99(2), 167–177. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12364

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar-McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2016). Multicultural and social justice counseling competencies: Guidelines for the counseling profession. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 44(1), 28–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmcd.12035

Riva Crugnola, C., Bottini, M., Madeddu, F., Preti, E., & Ierardi, E. (2021). Psychological distress and attachment styles in emerging adult students attending and not attending a university counselling service. Health Psychology Open, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/20551029211016120

Saldaña, J. (2021). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (4th ed.). SAGE.

Seiffge-Krenke, I., Persike, M., & Luyckx, K. (2013). Factors contributing to different agency in work and study: A view on the “forgotten half”. Emerging Adulthood, 1(4), 283–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696813487337

Shulman, S., & Connolly, J. (2013). The challenge of romantic relationships in emerging adulthood: Reconceptualization of the field. Emerging Adulthood, 1(1), 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696812467330

Smith, C., Christoffersen, K., Davidson, H., & Herzog, P. S. (2011). Lost in transition: The dark side of emerging adulthood. Oxford University Press.

Smith, J. A. (2024). Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (4th ed.). SAGE.

Sprecher, S., Econie, A., & Treger, S. (2019). Mate preferences in emerging adulthood and beyond: Age variations in mate preferences and beliefs about change in mate preferences. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(10), 3139–3158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407518816880

Stinson, R. D. (2010). Hooking up in young adulthood: A review of factors influencing the sexual behavior of college students. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 24(2), 98–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/87568220903558596

Wanzer, V. M., Gray, G. M., & Bridges, C. W. (2021). Lived experiences of professional counselors with gender diverse clients. Journal of LGBTQ Issues in Counseling, 15(2), 240–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2021.1914274

Weiss, D., Freund, A. M., & Wiese, B. S. (2012). Mastering developmental transitions in young and middle adulthood: The interplay of openness to experience and traditional gender ideology on women’s self-efficacy and subjective well-being. Developmental Psychology, 48(6), 1774–1784. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028893

Youniss, J., & Smollar, J. (1985). Adolescent relations with mothers, fathers, and friends. The University of Chicago Press.

Zupančič, M., & Kavčič, T. (2014). Student personality traits predicting individuation in relation to mothers and fathers. Journal of Adolescence, 37(5), 715–726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.12.005

Matthew L. Nice, PhD, is an assistant professor at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. Arsh, MA, is a doctoral student at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. Rachel A. Dingfelder, MA, is a professional counselor and a graduate of the clinical mental health counseling program at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. Nathan D. Faris, MA, is a professional counselor and a graduate of the clinical mental health counseling program at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. Jean K. Albert, MA, is a doctoral student at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. Michael B. Sickels, PhD, is a clinical assistant professor at Duquesne University. Correspondence may be addressed to Matthew L. Nice, 400 Penn Center Boulevard, Building 4, Suite 900, Indiana University of Pennsylvania Pittsburgh East, Pittsburgh, PA 15235, Mnice@iup.edu.

Sep 13, 2024 | Volume 14 - Issue 2

Dax Bevly, Elizabeth A. Prosek

Professional counselors may choose to increase self-awareness and/or engage in self-care through the use of personal therapy. Some counselors may feel reluctant to pursue personal therapy due to stigma related to their professional identity. To date, researchers have paid limited attention to the unique concerns of counselors in personal therapy. The purpose of this descriptive phenomenological study was to explore counselors’ experiences and decision-making in seeking personal therapy. Participants included 13 licensed professional counselors who had attended personal therapy with a licensed mental health professional within the previous 3 years. We identified six emergent themes through adapted classic phenomenological analysis: presenting concerns, therapist attributes, intrapersonal growth, interpersonal growth, therapeutic factors, and challenges. Findings inform mental health professionals and the field about the personal and professional needs of counselors. Limitations and future research directions are discussed.

Keywords: professional counselors, self-awareness, self-care, personal therapy, phenomenological

Self-awareness is a fundamental part of the counseling profession. Not only do professional counselors seek to increase the self-awareness and personal growth of their clients, but counselor educators call upon counselor trainees to increase their own self-awareness before entering the field (Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs [CACREP], 2023, Section 3A11). Additionally, counselor educators often recommend self-growth experiences such as personal counseling to increase counselor trainees’ self-awareness in preparation for professional practice (Remley & Herlihy, 2020). Several scholars define counselor self-awareness as the mindfulness of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in the self and in the counseling relationship (Fulton & Cashwell, 2015; Merriman, 2015; Rosin, 2015). Pompeo and Levitt (2014) asserted that self-awareness parallels awareness of personal values and enables counselors to explore best practices in counseling. However, after training, it becomes less clear how, if at all, counselors access their own counseling for self-growth and self-awareness; therefore, we designed the current study to explore how practicing counselors utilize personal therapy.

Correlates of Self-Awareness Among Counselors

Counselor self-awareness relates to awareness of the counseling relationship, which is helpful to client satisfaction and growth (Pompeo & Levitt, 2014); as such, several researchers have examined the clinical implications of counselor self-awareness, including professional competence, client treatment outcomes, and wellness. For example, Rake and Paley (2009) found that the therapists in their study reported modeling themselves after their own therapist as well as learning about technical aspects of a therapeutic approach. In regard to wellness, Gleason and Hays (2019) found that counselor self-awareness helped identify stressors and needs regarding personal wellness in doctoral-level counselor trainees. Similarly, Merriman (2015) discussed how self-awareness can help prevent burnout or compassion fatigue. Many researchers have investigated the importance of self-awareness as a characteristic of counselors who can competently work with culturally diverse clients (Ivers et al., 2016; Sue et al., 2022). Thus, some evidence of the clinical impact of counselor self-awareness already exists in the literature.

Expanding upon the impacts of self-awareness on the therapeutic relationship, Anderson and Levitt (2015) articulated the importance of self-awareness in how counselors’ social influence impacts the working alliance. Additionally, Tufekcioglu and Muran (2015) described how the working alliance provides a laboratory wherein the client can focus on and more clearly delineate their experience in relation to the therapist’s experience. Thus, the counseling goal of cultivating mindfulness in clients with respect to the details of their own experience involves counselors becoming mindful of the corresponding details of their own experience. Tufekcioglu and Muran argued that every encounter with a client demands the counselor’s self-reflection in the form of greater self-awareness in relation to the working alliance, and maintained that the therapeutic process should involve change for both participants.

Counselors Seeking Mental Health Care

Counselors can gain self-awareness in a variety of ways, including personal therapy. Mearns and Cooper (2017) stated that the term therapy loosely signifies the receiving of mental health services from any mental health professional who holds a license to practice. We use the word therapist in reference to researchers who did not specify the type of mental health professional (e.g., counselor, psychologist, social worker) who provided therapy to the participants in their study. Several scholars have suggested that therapists who participated in their own personal therapy experienced increased professional development as well as positive client outcomes. For example, VanderWal (2015) found that clients of counselor trainees with personal therapy experience demonstrated reduced rates of distress more quickly than clients of counselor trainees without personal therapy experience. Other researchers have noted the impact of therapy on therapists’ personal growth. Although not specific to professional counselors, Moe and Thimm (2021) conducted a systematic review of the literature regarding mental health professionals’ experiences in personal therapy and discovered benefits related to genuineness, empathy, and creation of a working alliance. Outcomes of this previous research support the positive impact of personal therapy for therapists.

Some counselors may seek personal therapy due to mental health concerns. Therefore, it is worth exploring the needs of this unique population. In one study, Orlinsky (2013) reported that therapists’ most frequently cited presenting concerns were resolving personal problems. Additionally, Moore et al. (2020) reported that counselors experienced interpersonal stress as a response to threatening situations in their clinical work and, in order to cope, neglected their own personal needs. Other investigators found a relationship between higher rates of ethical dilemmas in clinical practice and increased stress and burnout among counselors (Mullen et al., 2017). Robino (2019) introduced the concept of global compassion fatigue, a phenomenon wherein counselors experience “extreme preoccupation and tension as a result of concern for those affected by global events without direct exposure to their traumas through clinical intervention” (p. 274). In this conceptual piece, Robino summarized the literature findings on how indirect exposure of distressing events impact the mental well-being of professional helpers and advocated for the role of self-awareness as an important coping skill. Furthermore, Prosek et al. (2013) found that counselor trainees presented with elevated levels of anxiety and depression, providing further evidence that counselors are at risk for mental health concerns related to occupational and personal stressors.

Purpose of the Study

The psychological needs of counselors coupled with the emphasis on gaining self-awareness highlight the necessity for counselors’ personal therapy. Self-awareness is an important component of counselor development due to the personal nature of the profession (Pompeo & Levitt, 2014; Remley & Herlihy, 2020). Personal therapy is one way to enhance counselor self-awareness (Mearns & Cooper, 2017). Additionally, counselors may experience a variety of mental health concerns, including compassion fatigue, interpersonal conflict, depression, and anxiety (Moore et al., 2020; Mullen et al., 2017; Orlinsky, 2013; Prosek et al., 2013; Robino, 2019). Researchers have primarily focused on the perceived outcomes of personal therapy, including personal growth, professional development, and positive client outcomes (Moe & Thimm, 2021; VanderWal, 2015). However, scarce research exists regarding counselors’ decision-making processes in seeking personal therapy. Thus, if counselors could benefit from personal therapy, and if little knowledge exists regarding how counselors decide to seek personal therapy, professional counselors, counselor educators, counselor supervisors, and other mental health providers have limited information regarding how to facilitate that decision-making process.

Researchers employing qualitative investigation typically seek to holistically understand meaning. More specifically, the goal of a phenomenological approach is to capture the experiences and meaning-making from the participants’ perspectives (Creswell & Creswell, 2017). We want to illuminate how professional counselors make meaning of their experiences in personal therapy, as much of the existing literature focuses on trainees, clinical outcomes, or quantitative data. We believe describing the lived experiences, or essence (Moustakas, 1994), of counselors receiving personal therapy may lead to a deeper body of research regarding the perceptions, emotions, and behaviors of this population. The following questions guided our inquiry:

- What contributes to counselors’ decisions to seek personal therapy?

- How do professional counselors make meaning of their experiences in utilizing

personal therapy?

Method

Phenomenologists seek to understand the distinctive characteristics of human behavior and first-person experience (Hays & Singh, 2023). Based on an existentialist research paradigm, we wanted to understand how counselors make meaning of their experiences in personal therapy. Because we aimed to describe the lived experiences of counselors receiving personal therapy, descriptive phenomenology answers the research questions appropriately (Prosek & Gibson, 2021). Consistent with descriptive phenomenology, we used Miles et al.’s (2019) adaptation of classic data analysis, an inductive–deductive approach.

Research Team and Reflexivity

At the time of data collection (pre–COVID pandemic), Dax Bevly, who identifies as a White, Latina cisgender woman in her late 20s, was completing a doctoral degree in counseling. Elizabeth A. Prosek, who identifies as a White, cisgender woman, brought experience in conducting, teaching, and mentoring qualitative research studies. Bevly utilized a research team for data analysis that included four women in their early 20s completing master’s degrees in counseling; three identified as White and one identified as Asian. As instruments in the research themselves, the team needed to embrace their potential influence and impact (Hays & Singh, 2023); therefore, Bevly and Prosek participated in research reflexivity meetings several times during data collection and analysis, where they discussed thoughts and emotions evoked through their participation in the study. Descriptive phenomenology requires researchers to establish epoche, an exchange of assumptions that can be held accountable to bracket or identify throughout the process. Our research team demonstrated epoche by journaling and discussing biases and assumptions regarding the present study throughout the data analysis process. Bevly in particular was especially aware of her own personal biases due to long-term participation in personal therapy, believing it to have highly influenced her personal and professional development in a positive way. Bevly consulted with the research team as we examined experiences, reactions, and any assumptions or biases that could interfere with the coding process during data analysis. The research team members held Bevly accountable for her responses to the research process (Creswell & Creswell, 2017). The four other members of the research team also engaged in the examination of their experiences, reactions, and assumptions or biases during analysis, reporting assumed benefits including increased awareness, higher functioning in relationships, and increased self-esteem. Bevly also utilized the research team for the purpose of engaging in critical discussion during the analysis process in order to develop a trustworthy study. Furthermore, Bevly and Prosek kept a journal in order to document the research team members’ bracketing throughout the study. The journal also noted the connection and validation that Bevly experienced in interviewing participants and the care and mindfulness to not insert her personal experiences, especially regarding the overlapping roles of client and counselor as well as feelings of vulnerability.

Procedure

We obtained IRB approval before participant recruitment. Eligibility for the study included identifying as a licensed professional counselor (LPC) aged 18 or older who utilized counseling services with a licensed mental health therapist either currently or within the previous 3 years (similar criteria to Yaites, 2015). We used purposive sampling to select participants for this phenomenological study (Hays & Singh, 2023), recruiting participants through email, word of mouth, and networking with LPCs in a 50-mile radius of our institution, which is located in a large state in the Southwestern United States. This radius allowed us to intentionally reach more diverse areas of the geographical region. We also recruited participants through personal contacts and professional counseling organizations. Potential participants completed an eligibility online survey via Qualtrics. We contacted them via phone or email to explain the study and confirm their eligibility. We excluded participants who reported holding expired LPC licenses, experienced therapy more than 3 years ago, or described personal therapy from an individual without a license in a mental health profession. We scheduled face-to-face meetings with participants in their professional counseling office at their convenience. Although participants read and acknowledged the informed consent before meeting face-to-face, we readdressed informed consent before proceeding. Bevly conducted and audio recorded 60-minute interviews with each participant. At the conclusion of each interview, Bevly also facilitated a sand tray activity with the participant.

Participants

We recruited participants based on gaining depth with adequate sampling (Prosek & Gibson, 2021). Participants (N = 13) identified mostly as White, cisgender women with an average age of 37.23; see Table 1 for complete demographics. Although we sought to recruit participants with diverse social identities, geographic limitations presented a challenge. Thus, our findings should be interpreted with caution, as the external validity, or generalizability, of the findings to other populations or different contexts is impacted by the limited diversity among our participant demographics. Lastly, we asked participants to choose pseudonyms in an effort to protect their anonymity and confidentiality.

Data Sources

Demographic Form

In order to determine eligibility and collect demographic information, we asked potential participants to complete a Qualtrics survey, an online initial screening tool that included questions about age, gender, racial and ethnic identification, sexual orientation, religious/spiritual identity, number of personal therapy sessions completed, length of time since termination of personal therapy (if applicable), number of years as an LPC, disability status, licensure of therapist, therapist demographic information, and whether or not their counseling training program required personal therapy. The online demographic survey also included information about informed consent and confidentiality. Although it was not required for the study, all participants reported that therapy took place face-to-face.

Table 1

Participants of the Study

| Participant |

Age |

Race/Ethnicity |

Gender |

Religious/Spiritual Affiliation |

Sexual Orientation |

| Alma |

37 |

Latina |

Woman |

Christian |

Heterosexual |

| Amy |

30 |

Latina |

Woman |

Christian |

Heterosexual |

| Ashley |

29 |

Multiracial |

Woman |

Spiritual |

Heterosexual |

| Betty |

55 |

White |

Woman |

None |

Heterosexual |

| Elenore |

30 |

Multiracial |

Woman |

Christian |

Queer |

| Felicity |

44 |

White |

Woman |

Christian |

Heterosexual |

| Jennifer |

40 |

White |

Woman |

Christian |

Heterosexual |

| Liz |

35 |

White |

Woman |

Pagan |

Bisexual |

| Lynn |

48 |

White |

Woman |

Christian |

Heterosexual |

| Michelle |

37 |

White |

Woman |

Christian |

Heterosexual |

| Rose |

30 |

White |

Woman |

Christian |

Heterosexual |

| Sophia |

35 |

White |

Woman |

None |

Heterosexual |

| Thomas |

34 |

White |

Man |

None |

Heterosexual |

Semi-Structured Interview Protocol

We developed a semi-structured interview protocol to guide the interviews. We drafted the questions based on existing literature concerning counselors and personal therapy. The protocol consisted of six open-ended questions and follow-up prompts to understand the experiences of professional counselors who have engaged in personal therapy (see Table 2).

Table 2

Interview Protocol

| Grand tour question: |

| Please tell me about your experience in personal therapy in as much detail as you feel comfortable sharing. |

| Follow-up:

What motivated you to seek personal therapy?

What was happening in your life at the time?

How did you go about selecting a therapist?

Can you tell me about what your internal process (thoughts/feelings) was like leading up to your decision to seek personal therapy? |

| What outcomes did you experience as a result of personal therapy? |

| How, if at all, has personal therapy affected your personal growth? |

| How, if at all, has personal therapy affected your own clinical work? |

| Describe the experience of being both a client and a counselor.

Some literature suggests that counselors feel stigmatized when seeking personal therapy. What do you make of this? How is that similar or different for you? |

| Is there anything else that you would like to share? |

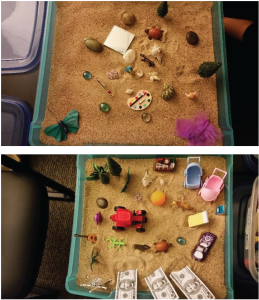

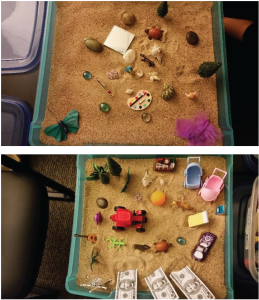

Sand Tray Activity

Hays and Singh (2023) stated that “visual methods in general provide participants the opportunity to express themselves in a nonverbal manner that may access deeper aspects of their understanding and/or experience of a phenomenon” (p. 332). After the semi-structured interview, Bevly invited participants to create their personal therapy experience in a sand tray using the figures and materials provided. This method is consistent with Measham and Rousseau (2010), who used sand trays as a method of data collection for understanding the experiences of children with trauma. The sand trays were documented by digital photos (see Appendix), and participants’ discussions about their creations are part of the audio recordings.

Data Analysis

We sent the audio recordings to a professional transcriptionist for transcription of each interview and sand tray session. We reviewed transcripts while listening to the recordings for participants’ tone and to verify accuracy. Consistent with phenomenological procedures, the research team conducted data analysis according to an adaptation of classic analysis (Miles et al., 2019), in which three main activities take place: data reduction, data presentation, and conclusion or verification.