Promoting Doctoral Student Researcher Development Through Positive Research Training Environments Using Self-Concept Theory

Margaret R. Lamar, Elysia Clemens, Adria Shipp Dunbar

Conceptualizing doctoral training programs as research training environments (RTEs) allows for the exploration of theory to help counselor educators facilitate doctoral students’ development from practitioners toward counseling researchers. Researchers have proposed self-concept theory as a way to understand identity development. In this article, the authors applied self-concept theory to understand how researcher identity may develop in a counseling RTE. Organizational theory also is described, as it provides insight for how doctoral students are socialized to the profession. Suggestions are made for how counselor education programs can utilize self-concept theory and organizational theory to create positive RTEs designed to facilitate researcher development.

Keywords: doctoral students, development, researcher identity, research training environments, self-concept theory

Conceptualizing doctoral training programs as research training environments (RTEs) allows for the exploration of theories to help counselor educators facilitate doctoral students’ development from having an identity primarily focused on being a helper toward a research identity (Gelso, 2006). Gelso (2006) defined RTEs as all “forces in graduate training programs . . . that reflect attitudes toward research and science” (p. 6). The RTE includes formal coursework; interactions with faculty, other students, and staff; informal mentoring experiences; and institutional culture that promotes or devalues research. However, there is little information about how counselor educators can practically develop a systematic approach to creating positive RTEs that facilitate the development of counselor education and supervision (CES) doctoral student researchers.

It is important to attend to the RTE because it has an impact on the researcher’s identity, researcher self-efficacy, research interest, and scholarly productivity of CES doctoral students (Borders, Wester, Fickling, & Adamson, 2014; Gelso, 2006; Gelso, Baumann, Chui, & Savela, 2013; Kuo, Woo, & Bang, 2017; Lamar & Helm, 2017; Lambie, Hayes, Griffith, Limberg, & Mullen, 2014; Lambie & Vaccaro, 2011). Researchers have found that CES doctoral student research self-efficacy and research interest were related to productivity (Kuo et al., 2017; Lambie & Vaccaro, 2011). Research self-efficacy is defined as the belief one has in their ability to engage in research tasks (Bishop & Bieschke, 1998). A related but separate construct, research interest is the desire to learn more about research. Lambie and Vaccaro (2011) found that doctoral students with scholarly publications had higher research self-efficacy and research interest, while Kuo et al. (2017) found that scholarly productivity can be predicted by research self-efficacy and intrinsic research motivation. Given that most CES doctoral students enter their programs with little research experience (Borders et al., 2014), the RTE likely contributes to a doctoral student’s ability to gain research and publication experience. However, much of the early exposure to research in counselor education rests primarily on research coursework, not extracurricular experiences, such as working on a manuscript with a faculty member (Borders et al., 2014). Though some programs provide systematic extracurricular non-dissertation research experiences, about half of the CES programs surveyed by Borders et al. (2014) offered no structured research experiences early in the program sequence or relied on doctoral students to create their own opportunities. Lamar and Helm (2017) found that the RTE, including faculty mentoring and research experiences, was an essential part of CES doctoral student researcher identity development. Given prior findings (Borders et al., 2014; Kuo et al., 2017; Lamar & Helm, 2017; Lambie & Vaccaro, 2011), it seems crucial for CES doctoral faculty to systematically create an RTE that is conducive to CES doctoral student researcher identity, research self-efficacy, and research interest development.

Leadership in the counseling field has stressed the importance of research in furthering the profession by stating that “expanding and promoting our research base is essential to the efficacy of professional counselors and to the public perception of the profession” (Kaplan & Gladding, 2011, p. 372). Therefore, it is essential to strengthen the training of future researchers so they are successful at achieving this vision. Thus, there are two primary purposes of this manuscript: 1) propose that the state of research in the field of counselor education is a reflection, in part, of an RTE issue; and 2) provide practical ways for programs to facilitate researcher development among doctoral students. The authors provide insight on how self-concept theory and organizational development theory may be a useful means for conceptualizing researcher development and facilitating change in RTEs.

Self-Concept Theory

Self-concept theory provides a framework for conceptualizing the way a person organizes beliefs about themselves. Purkey and Schmidt (1996) defined self-concept theory as “the totality of a complex and dynamic system of learned beliefs that an individual holds to be true about their personal experience” (p. 31). Learned beliefs are subjective and not necessarily based on reality but instead are reflections of individuals’ perceptions of themselves. These perceptions are related to past experiences and expectations about future goals. Purkey and Schmidt (1996) suggested conceptualizing the self-concept using the following categories: (a) organized, (b) learned, (c) dynamic, and (d) consistent. Discussions of each of these categories are presented in the context of applying self-concept theory to researcher development.

Current counselor training literature has discussed the development of student professional counselor identity (e.g., Prosek & Hurt, 2014); however, until recently (e.g., Jorgensen & Duncan, 2015; Lamar & Helm, 2017), counseling professional identity literature has not included a focus on how research is integrated into a student’s identity. Self-concept theory can be used to conceptualize the inclusion of researcher identity into the professional identity of CES doctoral students.

Organization of the Self-Concept

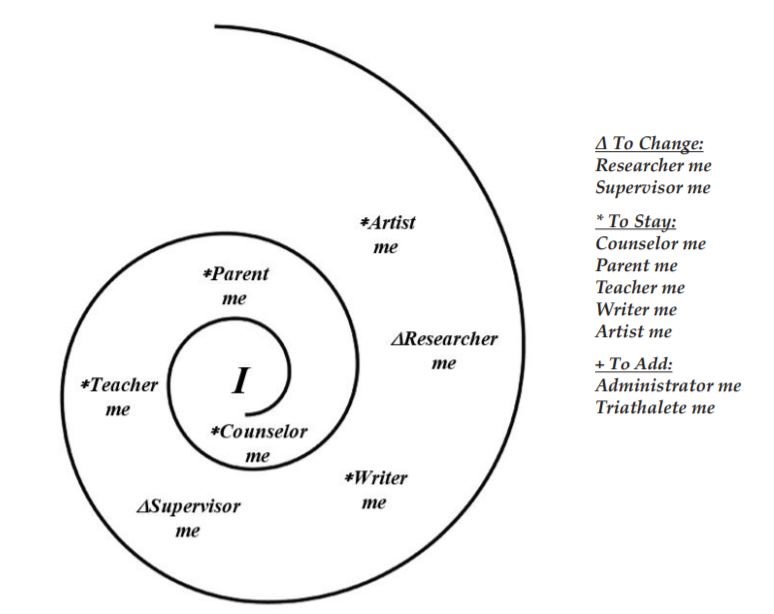

Purkey and Schmidt (1996) used a spiral as a visual representation of how the self is organized (Figure 1). They referred to the sense of self, or overarching view of who you are, as the central I, and placed it at the very center of the spiral. In addition, people also have other specific identities, or what Purkey and Schmidt termed me’s, that inform their global identity. These multiple identities can be considered hierarchical, meaning that one of the me identities might be more important to a person than another aspect of their identity and is placed more proximal to the central I on the spiral than more distal me’s. Developmentally, it makes sense that a beginning CES doctoral student, for example, may have a stronger counselor me (located closer to their central I), whereas their researcher me might be located closer to the periphery of the spiral. This is confirmed through previous research findings suggesting that CES students enter doctoral programs with stronger helper identities and integrate research into their self-concept throughout their academic experience (Gelso, 2006; Lamar & Helm, 2017; Lambie & Vaccaro, 2011). It would be expected that these me’s would be more likely to shift throughout the course of a doctoral program with greater exposure to a positive RTE. The relative importance of these identities to a doctoral student’s professional identity is illustrated for exemplary purposes in Figure 1. Faculty have a significant role in creating positive RTEs so that a doctoral student’s researcher me can be strengthened and become more fully integrated into their self-concept.

Figure 1. Self-Concept Spiral

Learning for a Lifetime

Developing the self-concept is a task that takes a lifetime of learning (Purkey & Schmidt, 1996). Self-

concept learning occurs in three ways: (a) exciting or devastating events, (b) professional helping relationships, and (c) everyday experiences. Individually, and in combination, these experiences can reorganize and shape a person’s self-concept. For example, receiving a first decision letter from an editor can be an exciting or devastating event that influences a doctoral student’s self-concept. Faculty members can process and contextualize the experience so a doctoral student’s researcher self-concept is positively promoted (e.g., a lengthy revise and resubmit letter can feel overwhelming but is a fantastic outcome; Gelso, 2006; Lamar & Helm, 2017). Similarly, the counseling RTE can promote positive research attitudes for doctoral students on a daily basis (e.g., displaying examples of student and faculty research).

Dynamic and Consistent Self-Concept Processes

Self-concept is dynamic; it is constantly changing and has the potential to propel doctoral student researchers forward (Purkey & Schmidt, 1996). Change occurs when a doctoral student incorporates new beliefs into existing ones. When new information is presented to the doctoral student, contrary to what they currently believe about themselves (e.g., ability to understand the methods section of an article), they are challenged to merge the new information with their current beliefs (e.g., “I’m a clinician,” and skip to the implications section). As they revise their belief system, they may be able to behave in new ways (e.g., making connections between the methods section and clinical application or engaging in critical discussions of research). However, reconciling new beliefs about their self-concept and demonstrating new research skills can be challenging. Consistency is highly valued by doctoral students faced with a need to adopt new ideas into their self-concept (Purkey & Schmidt, 1996). A doctoral student may experience what is commonly known as imposter syndrome, which occurs when a student is unable to internalize their accomplishments and attributes their success to good luck (Parkman, 2016). As CES doctoral students become proficient in research pursuits, they may still have difficulty seeing themselves as researchers (e.g., articulating hesitancy to share findings with peers or at professional conferences). They might tell others they are a counselor, a teacher, or a supervisor and they also conduct research, thus distancing that identity from the core of their self-concept (Lamar & Helm, 2017). They may need to repeatedly have their new researcher identity confirmed by faculty and their own personal experiences before they can communicate a fully integrated self-concept to others.

As learning occurs, the self-concept reorganizes toward a more stable professional identity. Incorporation of a researcher identity into their self-concept is likely to be dynamic, with consistency increasing throughout the doctoral students’ academic program. As CES doctoral students move into new stages of their career, their researcher identity is likely to become a more fixed aspect of their self-concept.

Development of the self-concept occurs in a CES doctoral program, which exists within the larger academic culture. Doctoral students are initially presented with the challenge of navigating a new culture. The culture of academe has its own processes, language, and roles. In addition to development of their researcher self-concept, doctoral students also must integrate their roles within higher education into their self-concept.

Organizational Development

A primary goal of doctoral education is to prepare and acculturate doctoral students to their future professional life as counselor educators (Austin, 2002; Johnson, Ward, & Gardner, 2017; Weidman & Stein, 2003). Many doctoral students in CES programs will pursue a CES faculty position within higher education organizations. Higher education organizations demonstrate various forms of culture and socialization processes (Tierney, 1997). University cultural norms include expectations for how to act, what to strive for, and how to define success and failure. Graduate education literature has included discussions on helping doctoral students transition into faculty life and university organizational culture (e.g., Austin, 2002; Austin & McDaniels, 2006). This socialization process has not been extensively discussed in the counselor training literature, yet there is potential for it to be useful in creating positive RTEs.

Socialization Into the Academy

Socialization is the process by which doctoral students learn the culture of an institution, including both the spoken and unspoken rules (Johnson et al., 2017). The process of socializing doctoral students to graduate school is a part of a greater socialization to higher education (Gardner & Barnes, 2007). Weidman, Twale, and Stein (2001) described four stages and characterized three elements of socialization—knowledge acquisition, investment, and involvement—that are experienced over the four stages. These stages provide insight for doctoral programs looking to provide intentional support for their students acclimating to the RTE within higher education.

Anticipatory stage. Doctoral students begin developing an understanding of the organizational culture even before they start a program of study (Clarke, Hyde, & Drennan, 2013; Weidman et al., 2001). During recruitment and introduction to the program, doctoral students gather information about the program (knowledge acquisition), decide to enroll (investment), and begin to make sense of organizational norms, expectations, and roles (involvement). CES doctoral students are, therefore, entering counseling programs with preconceived ideas about their roles as students, including their function as student researchers.

Formal and informal stages. The formal and informal stages co-occur but are differentiated in that the formal stage is more faculty or program driven, whereas the informal stage is peer socialization (Gardner, 2008; Weidman et al., 2001). Some of the formal stage methods of socialization can include classroom instruction, faculty direction, and focused observation. Courses grounded in the 2016 Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) standards related to doctoral professional identity or research are part of the formal socialization process. Out-of-classroom conversations with faculty and other university staff orient doctoral students to the value of research in the program and university. Doctoral students learn through faculty direction and observation about networking at conferences, publishing, and what types of research are considered valuable in the field. Students also observe faculty working around obstacles to keep their own research active. These examples are all consistent with knowledge acquisition.

Informal socialization happens as new doctoral students observe and learn how more advanced students and incoming cohorts define norms (Gardner, 2008). This stage has many parallels to existing research about how faculty acculturate to new organizations. Tierney and Rhoads (1994) proposed new faculty members learn the culture of the organization in mostly informal ways. As they observe the established tenured faculty, new faculty learn what is important to the department and develop understanding about the institution’s priorities. This acculturation process is important because it is likely to impact the RTE faculty create for doctoral students.

Similarly, doctoral students learning about culture, investment, and involvement in research are likely guided by the knowledge they acquire through observing and engaging with more advanced doctoral students in their programs of study (Gardner, 2008; Gelso, 2006). Acquisition of knowledge, occurring “through exposure to the opinions and practices of others also working in the same context” (Mathews & Candy, 1999, p. 49), creates norms among doctoral students. Norms regarding participation in research, such as whether it is done only to meet degree requirements or with more intrinsic motivation, may be conveyed across cohorts. Lamar and Helm (2017) found CES doctoral students were intrinsically motivated by their research when it was connected to their counselor identity and they could see how their research would help their clients. Jorgensen and Duncan (2015) identified external facilitators, such as faculty, coursework, and program expectations, that shaped the researcher identity development of master’s counseling students. Faculty communicated the culture of the institution and indirectly communicated their own intrinsic motivation, or lack of it, through their research activity. New students also gain insight from advanced doctoral students about the degree to which research should be aligned with faculty members and the more subtle messages about departmental expectations. For example, is qualitative research supported and valued as much as quantitative? Are certain research methodologies prioritized by faculty or the institution? The combination of formal and informal socialization leads to an understanding of the academic organization and counselor education profession.

Personal stage. During this final stage, doctoral students internalize and act upon the role they have taken within their organization (Gardner, 2008; Weidman et al., 2001). They solidify their professional identity at the student level and have, perhaps, begun to integrate their researcher identity into their self-concept. They also can use the knowledge they have acquired to make purposeful decisions about investment and involvement in research. Doctoral students make decisions about their course of study and the amount of time dedicated to developing as a researcher compared to other aspects of counselor education such as teaching, supervision, and service. In this stage, it is important for faculty to attend to whether doctoral students feel caught in the role they occupy within the program. Some doctoral students might more quickly adopt research into their self-concept and find opportunities to engage in research, while others take longer to develop their researcher identity and might not find themselves with as many options to get involved in faculty research projects. Additionally, those students’ strong helper identities might make them valuable doctoral-level supervisors or clinicians that programs can lean on to train master’s-level students. They may feel stuck in their clinical roles and miss out on opportunities to gain informal research experience. This is not to diminish doctoral students who are primarily interested in a CES degree with the goal of strengthening their clinical work. It is the position of these authors that scholarship is an integral part of all clinical work and, therefore, programs should provide equitable opportunities for all doctoral students, regardless of their professional goals, to engage in the research process.

Implications for Counselor Education RTEs

Thinking about CES programs as RTEs allows for a programmatic approach to researcher identity that can be informed by self-concept identity theory and organizational development literature. Specifically, there are implications for the RTE connected to fostering researcher identity, increasing both research self-efficacy and research interest, and attending to the process of socializing doctoral students to academia (Gelso et al., 2013). The strategies presented in this section are written with the goal of integrating self-concept identity theory and organizational development theory. They are designed based on the assumption that programs want to train researchers and celebrate that aspect of counselor education identity.

Transparency Regarding Identity Development

Formal socialization of doctoral students to the program should include intentional conversations about identity development (Lamar & Helm, 2017; Prosek & Hurt, 2014). Programs can choose to be transparent about the expectation that part of the transition from counseling to counselor education is strengthening their researcher identity. Attending to doctoral student development and class-based activities can be part of monitoring this transition.

Much like counselor educators assess and address the identity development of master’s students through student learning outcomes (CACREP, 2015), programs might choose to intentionally include researcher development in the systematic review of doctoral students’ progress. This could be accomplished through advising conversations, faculty feedback forms, and standardized instruments such as the Interest in Research Questionnaire (Bishop & Bieschke, 1998), Research Identity Scale (Jorgensen & Schweinle, 2018), or the Research Self-Efficacy Scale (Bieschke, Bishop, & Garcia, 1996). Considering this information at the program level, in addition to individual student level, can provide insight into opportunities to improve the RTE for program-level assessment and to impact the broader professional understanding of doctoral research education (e.g., does research interest or research self-efficacy consistently shift at identifiable points in a CES doctoral program?).

One class-based strategy is to use Purkey and Schmidt’s (1996) self-concept spiral to raise doctoral students’ awareness of professional identity transition. Counselor educators can consider asking students as a class to brainstorm all of the me’s that are part of counselor education. Individually, doctoral students can then create a list of me’s that are part of their identity in general (e.g., parent, musician). Once the counselor education and personal identity lists are generated, invite doctoral students to depict on the spiral the me’s from both lists that apply to their identity today and organize them relative to the central I (or center of the spiral). Next, encourage students to indicate with a star or asterisk aspects of their identity they want to remain stable throughout their doctoral program. Use a triangle, which symbolizes delta or change, to identify aspects of their identity they would like to shift as they progress through their doctoral program. Doctoral students might want to indicate in a space near the spiral counselor education me’s that are not currently part of their identity but that they would like to incorporate. Figure 1 is an example of a completed self-concept spiral. This spiral helps doctoral students visualize how their researcher identity relates to their other professional and personal identities. Faculty can facilitate conversation with doctoral students about their hopes, fears, concerns, and anticipation around their researcher identities. It would be even more valuable for doctoral students to hear their faculty’s researcher development using the spiral (e.g., draw one representing their years as a student and draw one where they see themselves now or at other points in their professional development).

Counselor educators can consider assigning research articles that address different aspects of counselor researcher development. Students can read about CES doctoral student researcher identity development (e.g., Jorgensen & Duncan, 2015; Lamar & Helm, 2017), RTEs (e.g., Borders et al., 2014; Gelso, 2006; Gelso et al., 2013), research self-efficacy and research interest (e.g., Kuo et al., 2017; Lambie & Vaccaro, 2011), and counseling research competencies (Wester & Borders, 2014). These articles provide insight for a doctoral student’s individual development and also demonstrate the applicability of research in the profession.

Sequencing of Research Experiences

Most incoming CES doctoral students have little or no research experience, which means their research self-efficacy and research interest is likely to be low and vary substantially (Borders et al., 2014; Gelso at al., 2013; Lambie & Vaccaro, 2011). This makes the sequencing of coursework and extracurricular research experiences important to consider (Borders et al., 2014; Gelso et al., 2013). Students on the extreme ends of research self-efficacy and research interest may see a quicker transition into a stable identity. Those with a higher research self-efficacy and research interest might more quickly identify as a researcher, while those with a lower research self-efficacy and research interest can move away from research toward other areas of focus. It is important, therefore, to sequence research experiences that can help doctoral students with higher levels of both research self-efficacy and research interest capitalize on that momentum without further disenfranchising students with lower research self-efficacy and research interest. The strategies presented in this section are described with the modifiers of higher and lower self-efficacy and interest for clarity purposes; however, individual doctoral student’s research self-efficacy and research interest could be anywhere on the continuum from very high to very low.

Determining a doctoral student’s sequence of research coursework or experiences can be accomplished through advising with the student (Kuo et al., 2017). A positive RTE is one in which care is taken to create developmentally appropriate research opportunities for all doctoral students (Borders et al., 2014; Kuo et al., 2017). Students with higher research self-efficacy and research interest might be ready to engage in a statistics sequence at the start of their program and then transition quickly into conducting independent research or engaging in data analysis. Doctoral students with lower research self-efficacy and research interest might benefit by first being exposed to research in a conceptual rather than technical environment, such as a counseling research seminar. Focusing on developing research ideas and reviewing the literature might be a better introduction to research for lower self-efficacy or interest doctoral students than a statistics course (Gelso, 2006). Kuo et al. (2017) found that it was important for CES programs to offer research opportunities that presented a small risk to doctoral students in order to foster researcher development.

For the optimal researcher development, it is important to provide doctoral students research experiences outside of their coursework (Borders et al., 2014; Kuo et al., 2017; Lamar & Helm, 2017). Providing doctoral students with opportunities to do “minimally threatening” research early in their program is consistent with a positive RTE (Gelso, 2006, p. 6). What each student might consider to be minimally intimidating research is likely connected to research self-efficacy (Kuo et al., 2017). Engaging in conversations with doctoral students about what might be a good first research experience is a way to help students intentionally sequence their experiences. Faculty can take an active role in connecting doctoral students with opportunities that are developmentally appropriate (Borders et al., 2014; Kuo et al., 2017; Lamar & Helm, 2017; Lambie & Vaccaro, 2011). Lambie and Vaccaro (2011) found that doctoral students with published work had higher levels of research self-efficacy than those who did not. This is an important finding for faculty to consider when creating research opportunities for doctoral students. One possible explanation for this result could be that doctoral students with a published work already have higher levels of research self-efficacy prior to their publication. If this is the case, it is important for researchers to investigate what other factors are contributing to their research self-efficacy. Nevertheless, an RTE that facilitates doctoral student confidence around research, regardless of their pre-existing research self-efficacy, is one where faculty are helping students publish, either on their own or in or in partnership with faculty actively engaged in research (Gelso, 2006; Kuo et al., 2017; Lambie & Vaccaro, 2011).

It is important to consider a doctoral student’s level of autonomy when planning sequencing of research experiences. Early experiences might be more positive if there is a community or social aspect to the research experience, rather than independent research projects, which can be isolating (Gelso et al., 2013). Additionally, Cornér, Löfström, and Pyhältö (2017) found that having an increased sense of a scholarly community helps doctoral students feel supported during their dissertations. Love, Bahner, Jones, and Nilsson (2007) found positive social interactions in research teams could positively influence research self-efficacy. Additionally, Kuo et al. (2017) found that the advisory relationship was instrumental in a doctoral student’s engagement in research, suggesting that faculty can make research a fun, social process in which students want to continually engage. It is evident that doctoral students can benefit from experiencing research as a social activity throughout their studies. Therefore, faculty might consider structuring research opportunities that encourage research as a social activity throughout the doctoral program. For example, first-year doctoral students can be encouraged to join research groups that are already in place or join a faculty member working on a manuscript for publication, while students working on a dissertation might create a weekly writing group.

Faculty should be intentionally thoughtful of doctoral student dynamics, including individual student need, research self-efficacy, and research interest, when designing research partnerships. Research partnerships can take the form of class research projects, informal research dyads, or research mentorships (Lamar & Helm, 2017; Lambie & Vaccaro, 2011). When deciding class research groups, faculty can connect doctoral students who can create a positive research group environment for each other (Love et al., 2007). Groups may be based on research interests or personality variables. Advisors might have insight into certain doctoral student characteristics that would negatively impact a research partnership. Negative group experiences, such as group conflict, do not contribute positively to research self-efficacy (Love et al., 2007). However, it is important for faculty to balance letting research groups form organically with formal assignment of such partnerships.

Attending to Subtle Messages About Research

Socialization to a doctoral program occurs formally through faculty- and program-driven processes and informally through interactions with peers (Gardner, 2008; Weidman et al., 2001). Neither formal nor informal socialization is synonymous with intentional socialization. There are likely subtle messages occurring through the socialization processes that contribute to the RTE and impact researcher development (Gelso, 2006). It is important to point out that program faculty and administrators might also send messages about research that are not subtle. These messages (e.g., a good dissertation is a done dissertation, or just get through your stats classes) are likely sent with the best of intention to help a student complete their degree successfully, but communicate values around research that can damage a doctoral student’s researcher identity development, research self-efficacy, and research interest. Recognizing and intentionally attending to all messages sent by students, faculty, and the program are part of shaping the RTE.

Student messages. Individual doctoral student and cohort dynamics may impact students’ research identity development both positively and negatively (Lamar & Helm, 2017). Different career aspirations among cohort individuals can also impact the RTE. For example, doctoral students who are interested in pursuing academic careers might have a higher level of motivation to involve themselves in research early in their graduate program. Students who plan to pursue other careers and do not have a strong interest in research might receive subtle messages from their peers or faculty about a hierarchy within the doctoral student body of “researchers” versus “practitioners.”

It is important for faculty to encourage positive interactions regarding research and to intervene should negative messages damage the RTE (Gelso, 2006; Lamar & Helm, 2017). Continuing with the above example, faculty can facilitate doctoral student discussions around the science–practitioner model. Focusing on the importance of integrating research into practice (and vice versa) can motivate all doctoral students in their research endeavors. The majority of students enter their doctoral program with their identities structured around helping others (Borders et al., 2014; Gelso, 2006). This value can be reinforced throughout the research process (Wachter Morris, Wester, Vaishnav, & Austin, 2018). For instance, faculty can facilitate discussion about how a doctoral student’s research can impact practitioners’ work and, ultimately, a client’s life. Additionally, faculty can reinforce subtle messages that contribute to the development of a positive RTE. For example, intentionally developing a culture of supportive inquiry, talking with each other about idea development, and celebrating each other’s research achievements can be encouraged and lauded (Gelso et al., 2013).

Faculty messages. Subtle messages faculty send about doctoral students’ abilities may influence students’ research self-efficacy and researcher identity development (Gelso, 2006; Lamar & Helm, 2017). Reflecting on the patterns of how research opportunities are provided to doctoral students may yield opportunities to improve the RTE. Consider if the culture to disseminate research-related opportunities includes all doctoral students or if opportunities are offered more frequently to a subset of students. If the latter proves to be true, faculty can send a subtle and unintentional message. Borders et al. (2014) found that doctoral students in many CES programs get involved in research opportunities by coincidence rather than by program intentionality. Students can receive a subtle message that not all doctoral students are welcome to participate in research or that faculty do not engage in research themselves. Similarly, messages about research ability can come in the form of differential faculty responses to doctoral students’ research-related work. Heightening awareness around the balance of feedback that is given to doctoral students when discussing their research ideas can contribute to an improved RTE. In addition, reflection on the rigor of the discussion helps faculty become more intentional about the messages they are sending.

Program messages. While programs often tout research-related accomplishments, faculty can contextualize those celebrations by talking about their process, not just the final products (Gelso, 2006; Gelso et al., 2013; Lamar & Helm, 2017). Orienting doctoral students to the substantial amount of time it takes to conduct research and to write for publication is part of intentionally socializing students to academia. Making the process more visible can be as simple as having a research project list visible in faculty offices or indicating blocks of time on office hour sign-ups that are set aside for writing. These are subtle messages that are designed to indicate that research takes dedicated time and that productivity is more than one manuscript at a time but having a variety of projects at different points in the pipeline. Similarly, Gelso (2006) recommended faculty share their failures as well as successes, as this sends doctoral students a message that research is a process. When faculty are transparent about research outcomes, both good and bad, and still maintain positive attitudes, they communicate subtle but important messages about the process of research (Gelso, 2006; Gelso et al., 2013; Lamar & Helm, 2017).

Directions for Future Research

Researchers (Gelso et al., 2013; Lambie et al., 2014; Lambie & Vaccaro, 2011) to date have focused primarily on identifying constructs that relate to research engagement and productivity of CES doctoral students. Increasing attention to understanding doctoral student researcher developmental processes and connecting those investigations to theory are important next steps. This could come in the form of investigations that explore experiences of doctoral students in the context of their RTEs. It also is important to increase understanding about how counseling master’s-level students and practitioners develop as researchers, specifically around the constructs of researcher identity, research self-efficacy, and research interest, as they provide important information about the state of researchers in the field and of doctoral students entering CES programs. As mentioned above, it would be valuable to understand if researcher identity, research self-efficacy, or research interest develops at specific points in a doctoral program or if certain doctoral benchmarks (e.g., comprehensive exams, dissertation proposal) contribute to the development of those variables. Researchers can look at educational interventions designed to increase research self-efficacy, research interests, and researcher identity for both doctoral and master’s counseling students. This is valuable for program evaluation and for informing the profession at large. Researchers also can test the relevance of the theoretical frameworks applied in this manuscript to the outcomes of the research competencies suggested by Wester and Borders (2014).

Conclusion

Counselor education doctoral programs as RTEs are the foundation for creating a programmatic climate that fosters the development of strong researchers. Faculty members are encouraged to take an intentional approach to promoting the development of researcher identity and research self-efficacy of doctoral students. This intentionality includes assessing the formal and informal socialization that occurs in a doctoral program. Program faculty can actively engage in the research identity development of doctoral students through the use of interventions, including attending to subtle messages, sequencing developmentally appropriate research experiences, and encouraging research as a social activity. Additionally, program faculty should be transparent about the research identity development process and attend to research self-efficacy beliefs through providing interventions designed to boost research self-efficacy and research interest.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Austin, A. E. (2002). Preparing the next generation of faculty: Graduate school as socialization to the academic career. The Journal of Higher Education, 73, 94–122. doi:10.1353/jhe.2002.0001

Austin, A. E., & McDaniels, M. (2006). Using doctoral education to prepare faculty to work within Boyer’s four

domains of scholarship. New Directions for Institutional Research, 2006(129), 51–65. doi:10.1002/ir.171

Bieschke, K. J., Bishop, R. M., & Garcia, V. L. (1996). The utility of the Research Self-Efficacy Scale. Journal of Career Assessment, 4, 59–75. doi:10.1177/106907279600400104

Bishop, R. M., & Bieschke, K. J. (1998). Applying social cognitive theory to interest in research among counseling psychology doctoral students: A path analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 45, 182–188. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.45.2.182

Borders, L. D., Wester, K. L., Fickling, M. J., & Adamson, N. A. (2014). Researching training in doctoral programs accredited by the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. Counselor Education and Supervision, 53, 145–160. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2014.00054.x

Clarke, M., Hyde, A., & Drennan, J. (2013). Professional identity in higher education. In B. M. Kehm & U. Teichler (Eds.), The academic profession in Europe: New tasks and new challenges (pp. 7–22). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

Cornér, S., Löfström, E., & Pyhältö, K. (2017). The relationship between doctoral students’ perceptions of supervision and burnout. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 12, 91–106. doi:10.28945/3754

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2015). 2016 CACREP

standards. Retrieved from http://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/2016-Standards-with-Glossary-5.3.2018.pdf

Gardner, S. K. (2008). Fitting the mold of graduate school: A qualitative study of socialization in doctoral education. Innovative Higher Education, 33, 125–138. doi:10.1007/s10755-008-9068-x

Gardner, S. K., & Barnes, B. J. (2007). Graduate student involvement: Socialization for the professional role. Journal of College Student Development, 48, 369–387.

Gelso, C. J. (2006). On the making of a scientist–practitioner: A theory of research training in professional psychology. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, S(1), 3–16. doi:10.1037/1931-3918.S.1.3

Gelso, C. J., Baumann, E. C., Chui, H. T., & Savela, A. E. (2013). The making of a scientist–psychotherapist: The

research training environment and the psychotherapist. Psychotherapy, 50(2), 139–149. doi:10.1037/a0028257

Johnson, C. M., Ward, K. A., & Gardner, S. K. (2017). Doctoral student socialization. In J. Shin & P. Teixeira (Eds.), Encyclopedia of international higher education systems and institutions. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

Jorgensen, M. F., & Duncan, K. (2015). A grounded theory of master’s-level counselor research identity. Counselor Education and Supervision, 54, 17–31. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2015.00067.x

Jorgensen, M. F., & Schweinle, W. E. (2018). The Research Identity Scale: Psychometric analyses and scale refinement. The Professional Counselor, 8, 21–28. doi:10.15241/mfj.8.1.21

Kaplan, D. M., & Gladding, S. T. (2011). A vision for the future of counseling: The 20/20 principles for unifying

and strengthening the profession. Journal of Counseling & Development, 89, 367–372.

doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2011.tb00101.x

Kuo, P. B., Woo, H., & Bang, N. M. (2017). Advisory relationship as a moderator between research self-efficacy, motivation, and productivity among counselor education doctoral students. Counselor Education and Supervision, 56(2), 130–144. doi:10.1002/ceas.12067

Lamar, M. R., & Helm, H. M. (2017). Understanding the researcher identity development of counselor education and supervision doctoral students. Counselor Education and Supervision, 56, 2–18. doi:10.1002/ceas.12056

Lambie, G. W., Hayes, B. G., Griffith, C., Limberg, D., & Mullen, P. R. (2014). An exploratory investigation of the research self-efficacy, interest in research, and research knowledge of Ph.D. in education students. Innovative Higher Education, 39, 139–153. doi:10.1007/s10755-013-9264-1

Lambie, G. W., & Vaccaro, N. (2011). Doctoral counselor education students’ level of research self-efficacy, perceptions of the research training environment, and interest in research. Counselor Education and Supervision, 50, 243–258. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2011.tb00122.x

Love, K. M., Bahner, A. D., Jones, L. N., & Nilsson, J. E. (2007). An investigation of early research experience and research self-efficacy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 38, 314–320.

doi:10.1037/0735-7028.38.3.314

Mathews, J. H., & Candy, P. C. (1999). New dimensions in the dynamics of knowledge and learning. In D. Boud & J. Garrick (Eds.), Understanding learning at work (pp. 47–64). London, UK: Routledge.

Parkman, A. W. (2016). The imposter phenomenon in higher education: Incidence and impact. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 16, 51–60.

Prosek, E. A., & Hurt, K. M. (2014). Measuring professional identity development among counselor trainees. Counselor Education and Supervision, 53, 284–293. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2014.00063.x

Purkey, W. W., & Schmidt, J. J. (1996). Invitational counseling: A self-concept approach to professional practice. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks Cole.

Tierney, W. G. (1997). Organizational socialization in higher education. The Journal of Higher Education, 68, 1–16. doi:10.1080/00221546.1997.11778975

Tierney, W. G., & Rhoads, R. A. (1994). Faculty socialization as cultural process: A mirror of institutional commitment

(ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 93-6). Washington, DC: The George Washington University

School of Education and Human Development.

Wachter Morris, C. A., Wester, K. L., Vaishnav, S., & Austin, J. L. (2018). Introduction. In C. A. Wachter Morris & K. L. Wester (Eds.), Making research relevant: Applied research designs for the mental health practitioner (pp. 1–13). New York, NY: Routledge.

Weidman, J. C., & Stein, E. L. (2003). Socialization of doctoral students to academic norms. Research in Higher Education, 44, 641–656. doi:10.1023/A:1026123508335

Weidman, J. C., Twale, D. J., & Stein, E. L. (2001). Socialization of graduate and professional students in higher education: A perilous passage? (ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report, 28, No. 3). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Wester, K. L., & Borders, L. D. (2014). Research competencies in counseling: A Delphi study. Journal of Counseling & Development, 92, 447–458. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00171.x

Wester, K. L., Borders, L. D., Boul, S., & Horton, E. (2013). Research quality: Critique of quantitative articles in the Journal of Counseling & Development. Journal of Counseling & Development, 91, 280–290.

doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2013.00096.x

Margaret R. Lamar, NCC, is an assistant professor at Palo Alto University. Elysia Clemens is Deputy Director of the Colorado Evaluation and Action Lab. Adria Shipp Dunbar is an assistant professor at North Carolina State University. Correspondence may be addressed to Margaret Lamar, Palo Alto University, 1791 Arastradero Road, Palo Alto, CA 94304, mlamar@paloaltou.edu.