Rural Mothers’ Postpartum Social and Emotional Experiences: A Qualitative Investigation

Katherine M. Hermann-Turner, Jonathan D. Wiley, Corrin N. Brown, Alyssa A. Curtis, Dessie S. Avila

The social and emotional challenges experienced by new mothers residing in rural areas are distinct from those confronted by their urban and suburban counterparts. However, the existing literature on postpartum social and emotional experiences of rural mothers is limited. To address this gap in knowledge, we conducted a phenomenological study to explore the postpartum social and emotional experiences of rural mothers. The study revealed that rural mothers experience feelings of powerlessness, thwarted help-seeking, and resilience. Findings are discussed in the context of the wider discourse on childbirth and postpartum experiences of rural mothers and have important implications for professional counselors serving rural communities.

Keywords: rural mothers, postpartum, social, emotional, rural communities

It is estimated that approximately 3.6 million women give birth in the United States annually (Osterman et al., 2023). The process of becoming a mother is a challenging and transformative experience that may bring about emotional vulnerability, radical changes in identity, and the risk of adverse psychosocial outcomes (Darvill et al., 2010). This transition can have a significant impact on a mother’s overall social and emotional well-being, including their self-efficacy, self-esteem, and sense of empowerment (Fenwick et al., 2003). For example, mothers who have reported a traumatic birth described subsequent difficulties with maternal self-efficacy and emotional disconnection from their child after delivery (Molloy et al., 2021). Furthermore, balancing family responsibilities, caring for a newborn, and focusing on career postpartum provide less available time and fewer energy resources to support self-care behaviors and to manage stress (Dugan & Barnes-Farrell, 2020), factors that have been shown to be a part of the experience of maternal postpartum depression and anxiety (Cho et al., 2022).

The purpose of this study is to explore the experiences of postpartum biological mothers residing in rural communities. Through qualitative inquiry, the study seeks to provide a comprehensive understanding of social support networks, emotional health, and the overall adjustment of mothers living in rural areas following childbirth. While we recognize that many individuals are impacted by the birth of a child (biological parents, adoptive parents, surrogate parents, grandparents, kin, and friends), that the role of a mother can be assumed by various individuals in families, and that not all individuals who give birth identify as a mother, this study specifically investigated the experiences of women who identified as biological birth mothers. By exploring the unique contexts of rural settings, we aim to uncover the nuanced factors that influence psychological well-being during the postpartum period. The findings are intended to inform clinical interventions and support strategies that will ultimately contribute to improved postpartum support and family health in rural communities.

Postpartum Social and Emotional Experiences

Social support or the absence of social support can be connected to maternal rates of depression, anxiety, self-harming behaviors, and general maladjustment (Bedaso et al., 2021; Milgrom et al., 2019). Enlander and colleagues (2022) qualitatively explored relevant themes regarding mothers’ perceptions of support as they related to perinatal distress and recovery. They found that mothers communicated themes of limited practical and emotional support, vulnerability to long-term relational or familial norms, and the relevance of sociocultural norms related to subjective feelings of perinatal distress. In addition, they found that having supportive and understanding relationships with friends and family can help protect against feelings of postpartum distress. On the other hand, a lack of such supportive relationships can reinforce unhelpful social norms related to motherhood and mental health (Enlander et al., 2022). These norms include both high expectations of new mothers and mental health stigma. Furthermore, the cumulative benefit of large support systems throughout the perinatal period can be beneficial in promoting psychological wellness (Vaezi et al., 2019).

Like the quantity of maternal social relationships, the quality of relational support is also an influential characteristic in new mothers’ social and emotional experiences. The quality of social relationships or support, including romantic and familial, can significantly minimize the maternal risk of postpartum psychosocial distress (Smorti et al., 2019). For example, the influence of new mothers having contact with other new mothers has been identified as beneficial social support in early postpartum recovery, as it promotes confidence and connection through shared history (Darvill et al., 2010; Enlander et al., 2022). Acknowledging the skills and abilities of mothers, as well as forming reliable and unconditional relationships where support is provided consistently, can not only serve as protective measures against postpartum depression, anxiety, and stress (Milgrom et al., 2019), but can also promote positive postpartum recovery (Zamani et al., 2019).

Given that social support has been found to be associated with a decreased probability of a mother developing postpartum depression (Cho et al., 2022), it can be inferred that public health guidance such as social distancing measures, neonatal visitation limitations, and reduced interpersonal contact with hospital staff during COVID-19 have had an impact on the maternal social and emotional experiences that can contribute to maternal psychosocial well-being or distress. For example, Ford and Ayers (2009) found that the support provided by hospital staff during childbirth had a more significant impact on mothers’ emotional responses to childbirth than perinatal and postpartum stressors.

Rural Postpartum Social and Emotional Experiences

Mothers who reside in rural localities have unique challenges compared to their urban and suburban counterparts. Due to the scarcity of health care providers and infrastructure in rural communities, significant differences in access to critical care obstetrics in rural and frontier areas of the United States exist (Kozhimannil et al., 2016, 2019; Kroelinger et al., 2021). Mothers in these areas often cope with challenges such as poverty, transportation barriers, and long distances to health care facilities, sometimes beyond a 50-mile radius. Hung and colleagues (2017) found that 45% of rural counties had no hospitals with obstetric services, with 9% experiencing a loss of in-county obstetric services. Rural counties that did not have hospital obstetric services tended to be smaller in geographical area; more significant gaps in service increased with the removal of hospital-based obstetric care. This evidence points to an overall decline in critical infrastructure related to childbirth and postpartum care in rural communities.

Disparities in mental health outcomes, including symptoms of depression during pregnancy and the postpartum period, have been observed in rural areas among mothers when compared to those residing in urban areas (Nidey et al., 2020). Factors associated with poor mental health outcomes outlined by Nidey and colleagues (2020) included socioeconomic barriers commonly found in rural contexts, such as limited access to services. Additionally, mothers living in rural areas were more likely to be younger, unmarried, and publicly insured and to possess lower education levels than their urban counterparts (Nidey et al., 2020).

Geographic isolation, limited resources, and the stigma associated with mental illness can cause rural residents to avoid seeking mental health care (Letvak, 2002). Within low-income rural populations, maternal distress is significantly predicted by experiences of emotional abuse, recent stressors, and discrimination (Ruyak et al., 2022). New mothers in rural communities deal with several challenges regarding limited health care services and support access. These challenges can be further complicated by a history of trauma and rejection, which may create barriers to seeking social relationships and hinder their recovery (Hine et al., 2017). Building trust with others can be difficult when social support is limited. According to a study conducted in the midwestern United States (Eapen et al., 2019), pregnant women living in rural areas received significant support from their partners and female relatives. The mothers often expressed their desire to have access to emotional support and maintain social support throughout their pregnancy from partners and social networks of relatives and friends.

Understanding Rural Mothers’ Postpartum Social and Emotional Experiences

Counseling researchers have not thoroughly explored the postpartum experiences of rural mothers. The current understanding of childbirth is limited to outdated studies related to prenatal care (Choate & Gintner, 2011) and postpartum depression (Albright, 1993; Pfost et al., 1990), with little to no understanding of the social and emotional factors contributing to these conditions. Furthermore, a lack of knowledge about rural mothers’ social and emotional experiences during the postpartum period exists, including what factors contribute to these experiences. This study sought to understand mothers’ postpartum social and emotional experiences in rural communities. We defined social experiences as the verbal, nonverbal, and interactive events that occurred between the postpartum women and individuals (e.g., friends, family, neighbors) in their community. We defined emotional experiences as events that impacted the mothers psychologically during the period after giving birth. The research question that this study aimed to address was: What are the postpartum social and emotional experiences of mothers in rural communities?

Method

We used a qualitative research approach to understand the postpartum experiences of women who identify as biological mothers in rural communities. Specifically, we selected transcendental phenomenology (Moustakas, 1994) for this study’s methodology. Drawing from a realist ontology and constructivist epistemology (Flynn et al., 2019), Moustakas’s (1994) transcendental phenomenology is congruent with this study’s purpose and research question, which desired to understand the lived experiences of postpartum mothers in rural communities. Additionally, Moustakas’s (1994) transcendental phenomenology provided a methodological context that emphasized the bracketing of prior assumptions and knowledge (i.e., epoche) among the members of the research team to distinguish, understand, and describe the particular postpartum experiences of the participants.

Participants

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained prior to recruitment from the university with whom we were affiliated at the time this study was conducted. Participants were recruited from five rural counties in the Appalachian region of the Southeastern United States. Each of the five counties identified was selected based on its classification as rural by the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (2022). Purposive criterion sampling was used to recruit participants based on the following selection criteria: biological mothers, at least 18 years old, residing in one of the identified rural counties, and having a child under the age of 2. Recruitment materials in the form of flyers were shared (in person and via email) with various community venues within each of the five counties, such as childcare facilities, medical clinics, and public libraries. The flyers included information on the study, inclusion criteria, and notification of a $100 gift card for compensation (research was supported by a grant from the Tennessee Tech Center for Rural Innovation). Members of our research team contacted representative gatekeepers from these recruitment venues and gained permission to share the recruitment flyers with potential participants within these settings. Potential participants interested in the study could voluntarily communicate their interest in participating to the research team; a member of our research team screened each participant based on the study’s inclusion criteria.

Our recruitment strategy resulted in a sample size of 16 participants from four counties. We organized focus groups based on the geographic residency of the participants within the four counties. This approach resulted in participants from the same rural county being grouped into the same focus group. The mean composition of participants per focus group was four, with a standard deviation of 2.3 across the four focus groups. Participants ranged from 25 to 34 years of age (M = 30, SD = 2.6). Fifteen participants identified as White/Caucasian and one as multiracial/multiethnic. The total household income reported by participants included $10,000–$24,999 (n = 1), $25,000–$49,999 (n = 5), $50,000–$74,999 (n = 5), $75,000–$99,999 (n = 4), and $100,000–$149,999 (n = 1). The participants had between one and four children (M = 2.25, SD = 0.9), who at the time of the study were between the ages of 4 months to 14 years (M = 4.2, SD = 3.3). Thirteen participants reported being married, two reported being in committed relationships, and one reported being single. Five participants were high school or equivalent graduates. One engaged in some college coursework, three earned associate degrees, six earned bachelor’s degrees, and one earned a master’s degree. Ten participants reported being employed; six reported not being employed outside of the home at the time of the study. Twelve participants reported that they did not receive any postpartum professional counseling, while four participants indicated they had received some form of postpartum professional counseling services.

Data Collection and Analysis

Data was collected through focus group interviews led by Katherine M. Hermann-Turner. Discussions were held in large meeting spaces familiar to that community (e.g., library, church hall, community center). Participants provided informed consent before engaging in research activities. Participants attended one of four focus groups and engaged in a semi-structured interview designed to last 90 minutes. Focus groups were moderated by Hermann-Turner, who has extensive qualitative interviewing experience, and were conducted in person and audio recorded. At each focus group meeting, institutionally approved childcare specialists offered participants no-cost childcare in a designated area of the meeting space.

The semi-structured interview protocol consisted of three primary areas of focus related to understanding participants’ descriptions of their postpartum social and emotional experiences (e.g., What are your feelings about this experience?), processing of postpartum social and emotional experiences (e.g., What has helped you process your postpartum social and emotional experiences?), and their experiences of postpartum social and emotional meaning-making (e.g., Who have you talked to about your postpartum social and emotional experiences since you went home with [your baby]?). To increase the accuracy of participants’ recall during data collection, Hermann-Turner asked the participants to discuss their last birth experience and if they had multiple children. The research team provided each participant with contact information for mental health resources and services should they want to follow up on any topics discussed during the focus groups. The focus group audio recordings were manually transcribed by the research team to ensure the accuracy of the transcripts used for data analysis.

Hermann-Turner, Jonathan D. Wiley, and Corrin N. Brown served as the data analysis team. They worked together to analyze the data by meeting as a group and reaching a consensus during each stage of the research process. Once the focus group interviews were transcribed, the team used the guidelines Moustakas (1994) provided to analyze the data. Based on these data analysis guidelines, they selected the Stevick-Colaizzi-Keen phenomenological data analysis method. This method, completed for each focus group transcript, involved identifying salient descriptions of participants’ experiences. These descriptions were then grouped into themes that were used to create a detailed description of the meanings and essences of the participants’ experiences. They then constructed a composite textual–structural description of the meanings and essences of participants’ experiences across all the focus group transcripts, including verbatim examples from the transcripts to describe the themes reported in this study.

Trustworthiness and Positionality

Epoche—setting aside prejudgments, biases, and preconceptions throughout the research process—is essential to transcendental phenomenological research (Husserl, 1931; Moustakas, 1994). As such, we aspired to maintain epoche by employing trustworthiness strategies focused on bracketing our prejudgments, biases, and preconceptions throughout the research process. Before engaging in any research activities, we explored our subjectivity related to the phenomenon of the study by engaging in a reflective writing process to explore the connections we had with the conceptualization of the study, the phenomenon of study, the participant population, and the context of the research.

Collectively, we acknowledge how our anecdotal observations and experiences guided us to explore this topic and understand how mothers’ postpartum social and emotional experiences in rural communities can be enhanced. Although we share this unified belief, we represent a variety of backgrounds and experiences related to the present study. Specifically related to the phenomenon of inquiry, two researchers are biological mothers and have had their own postpartum social and emotional experiences. One of the researcher’s postpartum recoveries was in a non-rural context. In contrast, the other researcher’s postpartum recovery was within a rural community. The remaining three researchers have not experienced postpartum social and emotional experiences as biological parents. Concerning experience with rural communities, three of the five authors have direct experience with rurality, as they reside and serve as counselors in rural communities. The remaining two authors acknowledge limited experience related to living and working within rural communities.

We employed several trustworthiness strategies that supported the bracketing of our various experiences to the study phenomenon and context. In addition to the a priori reflective writing exercise mentioned above, all researchers engaged in weekly reflexive journaling during study formulation, recruitment, and data collection. Weekly reflexive journal entries were discussed among the research team. These group-based reflexive discussions focused on making sense of and, when necessary, bracketing the influence of prejudgments, biases, and preconceptions in relation to the study such as our personal and professional commitments to advocating for the presence of familial support, family-oriented community structures, and greater accessibility to postpartum services. As the research process transitioned to the data analysis phase, we reserved our reflexive responses and primary interpretations of the data for discussion in face-to-face meetings. Containing the data analysis process to the group milieu supported our use of analyst triangulation, providing that no one member of the data analysis team engaged in the analysis and interpretation of the data alone.

Findings

Four themes were found using Moustakas’s (1994) transcendental phenomenology methodology: powerlessness, help-seeking, recovering power, and here and now. Below, we present these themes, building on the theme of powerlessness and culminating with the participants’ empowering experience of being heard in the present moment during the focus groups. While this data is presented in a progressive sequence that seemingly indicates a transition from powerlessness to empowerment, we would like to note that we are not proposing a developmental model. Each theme is described and elaborated upon below using the participants’ words.

Powerlessness

The first theme pertains to the feelings of powerlessness experienced by participants from rural communities regarding childbirth and postpartum recovery (i.e., physical and emotional). Participants expressed feelings of powerlessness within childbirth by sharing ways this feeling impacted their delivery and how the experience of being inadequate, out of control, or powerless extended into their role as mothers and sometimes into their postpartum recovery.

In talking about childbirth, the participants recounted intense experiences where they felt that they did not have a choice or a voice when birthing their child or have autonomy over their body. One participant stated, “I could have pushed. But the doctor was busy, and I was like, this is ridiculous.” Others collectively described the limitations of epidurals: “My back looked like I had been shot with a BB gun because they kept trying to poke. And I’m like, can you please get somebody that’s going to get it right the first time at this point?” Another participant noted the disregard for knowledge of her own body:

But the epidural didn’t work for me either. I had a hot spot, so they kept trying to put it back in and there was one spot that it wasn’t working on, which I knew would happen because of my back problems.

Other participants shared their lack of voice when deciding to have a vaginal delivery or an epidural, stating:

The doctor was like, well, we’ll schedule C-section for tomorrow. I was like, oh no we will not! What’s my options here? So, I had a C-section with her at 38 weeks. When she came out, I got to see her for a minute, but they told me all kinds of things were wrong with her. And then she went to the NICU.

Another similarly recounted:

I was in labor for 4 nights with my first. Four nights, we’re talking contractions 5 minutes or less apart for 4 days and all the trauma on my body. . . . I begged for a C-section towards the end, and they just kept telling me “No.” On the fourth night, I begged, and I begged, and begged. They said, “No, no, no.” No one listened to me. And then when his heart rate started dropping, they were like, “Okay, we have to do a C-section.’’

Powerlessness within participants’ postpartum recovery was also expressed. Similar to the statements above concerning powerlessness within the birth experience, participants described continued barriers to recovery, bonding with their baby, and building memories due to external constraints (e.g., physical recovery or sleep deprivation). One participant stated, “I kind of don’t remember any of his first couple of months because I had three surgeries after he was born, and I couldn’t take care of him by myself.” Another shared, “I was so sleep deprived . . . I don’t remember their first year of life.” Participants’ ability to fully embrace the experience with their newborn was seemingly governed by secondary factors.

In addition, participants stated a lack of empowerment in their follow-up care and in making decisions regarding the care of their newborn. Two participants shared, “When I breastfed, I had no idea what I was doing. Nobody helped me,” and “I skipped my appointment because I just felt not heard. I didn’t want to go . . . I felt like it was pointless.” One participant shared, “They’re almost pushing formula . . . ‘No, you’re giving me an out. I really want to do this [breastfeed],’ like ‘Let me do this please.’ . . . They’re not hearing you at all.” Another participant expressed the weight of expectation of “having it together,” where seeking support is met with, “You got it, you’re such a super mom,” communicating a further sense of perceived abandonment.

Powerlessness in postpartum recovery also emerged through participant disclosures concerning their position as a mother. One participant stated, “We don’t get the option to walk away,” communicating the longevity and sense of direct responsibility experienced as a new mother. Another participant shared, “I remember lifting her up and the midwife was like, ‘Now you have to burp her.’ And I’m like, ‘Every time I feed her, I have to burp her?’ and I just started crying.” Another participant described a similar moment realizing that having a child is “gonna take work. And that was just the beginning.”

Experiencing powerlessness extended beyond overarching postpartum adjustment to subjective emotional aspects of recovery. Participants described a certain vulnerability to emotions that emerged, stating, “It hits you in the wildest of places. Like, I’m in Target.” And another shared, “I’d just be driving down the road in the car again . . . it’s so hard . . . babies are easy, but then it feels so hard, like in the moment.” Another participant shared her mechanism for navigating through intense emotions throughout postpartum recovery, stating, “I feel these feelings, I’ve had these thoughts run across my mind and I just shut them out” to cope in the moment.

Help-Seeking

A salient theme in the participants’ interviews relates to the disparity that they faced in effectuating requisite emotional and physiological needs. Participants identified postpartum needs such as sustaining physiological routines, emotional processing of postpartum experiences, and exploring postpartum selfhood and identity. Alternately, they also identified inconsistencies in their ability to meet these needs. Overall, the participants communicated support-seeking incongruities through their use of affective language relating fear and shame.

Participants described complexities related to sustaining the physiological routine needs of those in their care quickly after birth. Many participants described the rapid speed at which they returned to caring for their families after giving birth. For example, one participant stated, “We aren’t told to rest. We’re told to . . . have your baby and then keep going with your life.” This rapid transition to caring for their families after birth was described by several participants as a bewildering time. One participant illustrated this perplexing time by sharing, “I don’t know what I need. I don’t even know. My husband says, ‘What do you need from me?’ I don’t really know. I don’t know what I need.” This explanation describes the bewilderment many of the participants expressed.

Many participants described an interdependent relationship between meeting their and others’ physiological needs and their individual emotional experiences. For example, one participant stated, “I’m struggling physically, which is making me struggle mentally.” Many of the participants described challenging experiences related to the physical process of birth concerning the safety and livelihood of their child. Also, several participants described the postpartum period as more difficult emotionally. When asked to compare their emotional experiences of childbirth to the postpartum period, one participant answered, “That’s more postpartum, postpartum experience because that was harder for me than the births.” A few participants used words such as “debilitating” and “extreme” to characterize their postpartum emotional experience. One participant stated she “just didn’t understand how everybody else could be so normal around me, and I felt such extreme anxiety and fear.”

Another need frequently described by participants was the exploration of their postpartum identity and sense of self. Participants characterized this need as navigating the changes to their selfhood and identity due to their transition to parenthood. One participant candidly stated this need: “Like you’re still a person.” Within the context of parenthood, one participant described a process of “figuring out who you are outside of that [parenthood].” Many participants described challenges in integrating their individuality within their new role as a mother. For example, one participant explained, “It would help me to not just talk about the kids. Of course, your kids are a big chunk of your life, but actually being a person and having adult problems is a big chunk, too.” Explicitly referring to parenthood, one participant remarked, “I get resentful because I still deserve to be treated like a woman and not just like ‘mom and dad.’”

Whereas the dimensions above describe the postpartum needs of mothers for physiological routines, emotional processing, and identity exploration, most participants in the study had challenges in accessing these identified needs. These challenges were particularly noted in seeking social and emotional support. Most of the participants within this study described the accessibility they experience related to social support postpartum in affective terms; one of the most prominent affective dimensions identified was shame in seeking postpartum support. For example, one participant described their experience seeking available interpersonal and intrapersonal resources in their community: “There are resources all around me, but it’s like you feel ashamed.”

For some of the participants in this study, the experience of shame was associated with a fear of the consequences of being open and authentic with health care providers about their social and emotional experiences. One participant explained this shame and fear, stating:

You feel ashamed to say it. At one of my postpartum follow-ups, they’re like, “Oh, you feel like hurting yourself?” And, I’m thinking, “Yes, I want to die, I feel so depressed,” but you say “No” because you’re scared they’re gonna take your child away or they’re gonna call the police, they’re going to hospitalize you.

Several participants described similar patterns of desiring to be honest with health care providers but instead choosing to refrain from sharing their social and emotional experiences. Most of the participants described these types of inconsistencies in self-advocating for social and emotional support postpartum, given the acceptability of mental health within their specific rural communities. In response to discussion of providers’ preferred responses when seeking emotional support, one participant declared she would prefer a provider said, “‘Let’s go to counseling. Let’s have another follow-up appointment.’ Instead of, ‘Maybe we should call DCS’ and assuming she’s harming these kids or herself. It’s not that type of situation.” The discrepancy between self-identified needs and the potential repercussions of sharing their need for support, particularly emotional and mental health support, was a common theme across participants.

Recovering Power

Participants shared their processes of recovering their sense of power within the postpartum period. One participant explained their process of carving out personal time while navigating the challenges of the day:

Nursing her this whole time, I think has really helped with processing because I have to stop and sit down and breathe. So, I think it’s really helped having that 30–40 minutes of just sitting down because I don’t sit down when I’m home. I’m up cleaning and running, but yeah, nursing has really helped me process this birth a lot.

Other participants shared experiences of recovering their sense of power through personal growth and adapting to life’s challenges as new mothers. One participant stated:

I think you find yourself in motherhood. Not to say that women aren’t their true selves before they’re a mother. Who you are as a mother is who you are, you don’t have to be different or go back to who you were. It’s a growing experience and it’s hard, definitely.

Another participant shared how the experiences of childbirth and postpartum recovery helped shape her capacity for self-advocacy, stating, “I think through all of it, I learned to stand up for myself more than I ever have.”

Lastly, participants illustrated the moments of acceptance with their new roles as mothers and the decision to exercise gratitude for the profound changes associated with postpartum recovery. One participant recognized the position of mothers in providing care and support to their children with little acknowledgment or reciprocation, sharing, “You give so much, because you chose them, they owe you nothing in return. I think you come to terms with that too when you have babies because what are they going to give you?” Another participant shared the complexity of varied comfort levels of motherhood while recognizing the swiftness of childhood development, stating, “Postpartum is really hard for me. I’m just not good at it. But luckily, it’s such like a small time, I think just seeing them grow and knowing you’re doing it for a reason,” leading to assumed acceptance within the postpartum recovery process for many participants and that their efforts are not without meaning.

Here and Now

In addition to the themes presented about the birthing and postpartum period, throughout the interview processes, we became aware of the connectedness among the participants. The participants spoke about their here-and-now experiences, feeling supported in the focus group setting. Participants commented about the experience of being together, expressed support and empathy, and described hopes for ongoing opportunities to connect.

We were aware of the vulnerability of the participants as they found a safe place to share their stories. One participant described how she felt that the group was different from her previous group experiences, stating, “I hate group therapy. I do not speak in group therapy, but obviously, I can’t shut up. It just came out so openly because there’s a comfort here; there’s no uppity.” Another participant playfully shared, “I’m sharing a lot. Don’t judge me,” identifying how she felt comfortable talking about herself in the focus group setting.

The ability to be open was likely encouraged by the experience of being in a group of mothers who shared similar histories. One participant stated, “It’s nice knowing that you’re not alone like, you know, whenever you feel sad or upset or whatever, like, knowing other moms feel that too,” which was a similar sentiment to a participant of another group who said, “You know, it makes you feel so much better. It’s like, man, [you’re] going through it too, I’m not crazy.” The mothers also appreciated one another’s support, stating, “Yeah, it’s nice for someone to say, ‘Yeah, I get it.’”

The participants’ willingness to be vulnerable could result from the expression of support and empathy among the participants. The participants made frequent comments like, “That’s right. That’s how I feel too,” “Oh, that’s a good idea. I never thought about that,” “I didn’t even realize it till you just said that,” and “You’ve done a great job!” Sometimes, these expressions were minimal encouragers as the participants supported one another with ongoing head nods, mm-hmms, and the occasional expression of “Oh my gosh!” or “It really is!” At other times, the expression of support was more overt, as in statements like, “I don’t blame you for not having any more [children] after everything you went through. I’d be done, too.” The participants seemed to connect even when there were differences in their experiences, such as one participant describing respect for the participants who had C-sections: “Y’all are the women having C-sections that terrifies me. They said something about the C-section, and I was like [gasp!] no, I will get her out. . . . y’all are amazing for doing that.”

The participants not only supported one another in the conversations related to the group, but they also expressed warmth toward one another’s children. As described in the methodology section, the participants’ children were in the same large room with caregivers provided by the study. In the instances where a child was drawing their mother’s attention, the participants were open to the children, such as the comment by one mother normalizing the behavior: “The one thing we know about being a mom is that kids are unpredictable.” The participants also frequently complimented one another’s family with statements about the other children like, “You’re so cute” or “They’re lovely, beautiful.” The participants seemed to accept one another wholeheartedly without judgment.

Another consistent occurrence at the end of the groups was the participants’ gratitude for the experience of being together and a desire to continue meeting. For instance, one participant stated, “It would be nice if there were a mom group here because I’m not aware of that, some kind of a meetup or something.” Another mother brainstormed, “We could take the kids to the park. That way, they could play, and we can talk.” Overall, the feeling was consistent among the participants. Being with other moms was enjoyable, as shown in the statement, “I could do this all day, every day. Like, let’s talk everything babies” and “I do love talking about birth with other people. The same as you. I’ve never met another person with experience like I have. This is really great.” Overall, while the participants described many personal struggles, they also demonstrated their individual strength and empathic ability to support one another.

Discussion

Overall, this study extends the understanding of rural mothers’ postpartum social and emotional experiences, which have been overlooked in the professional counseling literature. The present study provides a focused insight into the rurality and postpartum social and emotional experiences related to the broader category of childbirth experiences. Although there have been important and recent contributions to the literature related to counselors’ perceptions of rural women clients (Leagjeld et al., 2021), our study provides an even more focused account of a specific dimension of rural mothers’ postpartum social and emotional experiences. While the authors anticipated themes related to multigenerational support, postpartum family support, and community support due to the rurality of the setting, we were surprised to uncover more universal themes related to motherhood.

Perhaps the most compelling finding is how participants experienced social and emotional powerlessness, which directly impacted their postpartum recovery. As mentioned in the literature review, a mother’s sense of self-efficacy, self-esteem, and empowerment has been found to impact maternal mental health (Fenwick et al., 2003; Molloy et al., 2021). Given the importance of autonomy as one of the fundamental principles of ethical behavior, according to the National Board for Certified Counselors (NBCC; 2023) and the American Counseling Association (ACA; 2014), the findings of this study highlight an important area of advocacy for the counseling profession. Participants in this study described proximal and systemic factors that impacted their experience of social and emotional powerlessness.

Participants referenced these proximal factors through the way they described not having a choice or voice regarding their care during and after childbirth. Across the participants in this study, the experiences during and immediately after childbirth seemed to set a tone for their postpartum recovery, with powerlessness at birth serving as a precursor to powerlessness postpartum. Some of the participants hinted at what has been referred to in the anthropological literature as a technocratic model of birth whereby the birth experience is characterized by mechanistic separation and control, reducing mothers’ autonomy during birth (Davis-Floyd, 2004). Although this reference to this technocratic model pertains specifically to childbirth, the initial childbirth experiences of participants described as mechanical, separate, and informed by external control in this study point to the development of longer-term postpartum social and emotional powerlessness. This social and emotional powerlessness and autonomy might be related to the development of postpartum anxiety and depression. Although social support has been found to decrease the probability of a mother developing postpartum depression (Cho et al., 2022), it is possible, therefore, that social and emotional powerlessness may also contribute to the development of postpartum anxiety and depression. Although this relationship can be surmised through the findings of this study, additional explanatory (i.e., causal) analyses are needed to further confirm the social and emotional determinants of postpartum distress, such as powerlessness.

Another important finding is that rural mothers desired and expressed an active openness to support their postpartum social and emotional experiences. Participants identified postpartum needs such as sustaining physiological routines, emotional processing of postpartum experiences, and exploring postpartum selfhood and identity. However, the participants in this study described experiencing barriers to supporting their postpartum social and emotional experience due to systemic barriers that impacted their ability to realize this desired support. The help-seeking theme reported in this study highlights that participants desired social and emotional help-seeking that was ultimately thwarted based on a variety of sociocultural factors such as geographic isolation, mental health stigma, and cultural norms of help-seeking behavior in addition to the reduced availability and accessibility of postpartum social and emotional supports in rural localities. This finding is consistent with previous studies that indicate an overall decline in critical structure related to childbirth and postpartum care in rural communities (Hung et al., 2017; Kozhimannil et al., 2016, 2019; Kroelinger et al., 2021). However, the findings of this present study provide localized insight into the demand side of postpartum social and emotional help-seeking. Although the supply of postpartum social and emotional support, in addition to critical health care infrastructure, was lacking, the rural mothers who participated in this study readily identified and desired needed social and emotional support.

Implications

The study’s results have various implications for counselors, particularly those working in rural communities or with a perinatal population. While there is a precedence for targeted interventions to support postpartum women through mental health programs (Geller et al., 2018), traumatic birth recovery support (Miller et al., 2021), and postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder recovery (P-PTSD; Cirino & Knapp, 2019), we did not observe these practices being implemented in any of the rural communities studied. The participants frequently described impactful, possibly traumatic, birth experiences and identified a lack of support during delivery and after being released from the hospital. Counselors, especially in rural communities, would benefit from establishing systems for support for postpartum mothers.

The participants also described a desire to feel supported by the medical community. Although they described crafting birth plans, they often felt that these were disregarded or ignored during childbirth, which contradicts recommendations to use birth plans to create security for women (Greenfield et al., 2019). The women also expressed apprehension toward assessment for postpartum depression by their doctor. Creating an environment where mothers feel safe with an emphasis on both depression and a holistic understanding of life’s current difficulties provides a more effective assessment (Corrigan et al., 2015). Counselors could benefit from providing psychoeducation to the medical community, particularly nurses in OBGYN clinics, or those having a role in supporting mothers within a medical setting.

A final implication for counselors is to help new mothers find social support and connections in their community. While literature supports the need for social support in rural communities (Letvak, 2002) and for postpartum mothers (Geller et al., 2018), throughout the groups, the mothers frequently identified the desire to stay connected yet being unable to find mothers’ groups. However, they identified a lack of opportunities within the community (e.g., no community meeting space and parks that are inaccessible in winter months) and not having the time, energy, or knowledge to form a group themselves. As a result, counselors can help by advocating for community spaces and creating postpartum support groups, which would greatly benefit the rural communities we studied.

Recommendations for Professional Counselors

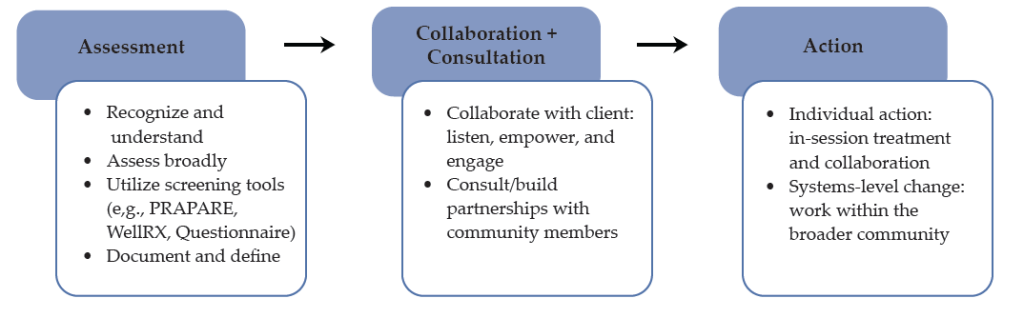

Given the findings of this study, we propose the following strategies for professional counselors to employ in supporting the social, emotional, and overall mental wellness of postpartum mothers in rural areas:

- Empowerment practices: In the context of postpartum mothers, it is crucial for counselors to address feelings of powerlessness that can impact mental health. Counselors should focus on empowering practices such as positive self-talk, affirmations, and promoting self-care to counteract external factors that diminish autonomy and control.

- Client autonomy: Autonomy is a fundamental ethical principle, and counselors must recognize the systemic relationship between clients’ life experiences and the support they can offer. Building a strong therapeutic alliance and emphasizing foundational counseling skills and relational dimensions can help establish a sense of safety and comfort in the therapeutic relationship.

- Support and counseling groups: We recommend providing support and counseling groups for postpartum mothers, as participants in this study responded positively to the group format. These groups can provide safe spaces for mothers to share their experiences and connect with one another. Counselors specializing in this area should facilitate the development of these groups to leverage the therapeutic benefits of group counseling.

- Telemental health infrastructure: The challenges related to the availability and accessibility of counseling services in rural areas have been well-documented. A commonly proposed solution is telemental health counseling, which enables facilitating support groups, conducting individual counseling, and working with postpartum mothers in remote communities. Professional counselors must advocate for improving physical infrastructure in rural areas in order to enhance telemental health services, including better internet access to facilitate the provision of these services.

- Continuing education and training: When providing telemental health counseling in rural areas, it is important to consider cultural competencies and approach differences with humility. Counselors not located in the same geographical areas as their clients may need more clarification on the specific context of their rural clients. Continuing education and training opportunities should be provided to counselors in rural communities, and they should be encouraged to share their work at state- and national-level conferences.

- Integrated primary and mental health care: Advocacy for counselors includes encouraging the integration of primary and mental health care services. This integration is critical in rural areas where the accessibility and availability of primary and mental health care is limited. Therefore, we suggest that counselors reach out to physical health professionals in their communities in order to find ways to integrate services and to address the physical and mental aspects of wellness for clients in rural areas.

Limitations and Future Research

A robust research methodology is incomplete without recognizing limitations, and we identify minor limits in recruitment, sampling, and interviewing. We intentionally selected a focus group format to create a sense of community and facilitate memory recall. Due to the rural environment, participants often had preexisting relationships. We speculated that the relationships among participants could affect their interactions, leading to either selective sharing or a sense of comfort with disclosure. We felt that the latter context was present, as the participants supported one another in vulnerable moments with empathy and self-disclosure.

Before collecting data, we identified an ideal group size of four to six participants; nevertheless, the four groups had significant variation as they had two, three, three, and eight participants. We held a fifth focus group, but because there was only one attendee, the data was not used for this study, as we felt the difference in setting was too great from the intended study. We also selected focus group times to accommodate mothers of young children (i.e., not offered during nap times or mealtimes). However, morning meeting times could have prevented mothers who worked during the day or outside of the home from attending. We also felt engagement in the community could have facilitated trust and recruitment, yet we did not have a preexisting connection to the communities. We considered that individual interviews could better accommodate participants’ schedules.

In addition, one participant was a mother of twins, which we recognize could lead to different experiences from the mothers of singletons, but at the time of the group, we felt creating a culture of inclusiveness outweighed the need for homogeneity. In retrospect, we felt the participant was a valuable contributor, and the decision toward inclusivity was correct. We recommend that future research on this population similarly create a climate of openness and community. Finally, we recognize that while using incentives is an accepted practice, the $100 gift cards may have not only motivated participants but also captured a specific demographic that was financially driven.

Additional research should pinpoint the specific challenges faced by new mothers and identify impactful support practices, especially for mothers in rural areas. Future research replicating this study in other rural areas could also strengthen the understanding of the population. As described in this study, every rural area is unique, so additional data from rural communities could further confirm this study’s understanding of women’s postpartum experiences. A final recommendation is the exploration of the impact of children in the family system as a source of postpartum support. One participant described her preteen daughter’s expression of curiosity about childbirth as a loving, supportive context where she could share developmentally appropriate information about her experience, and we wondered if this opportunity for processing is helpful for other postpartum women.

Conclusion

This study highlights the urgent need to address the disparities in postpartum support for mothers living in rural areas. The findings describe rural mothers’ social and emotional experiences, including feelings of powerlessness, a desire to seek help, and their resilience in the face of difficulties. By advocating for expansion of the overall infrastructure for care during childbirth and postpartum, counselors can enhance their support of rural mothers’ social and emotional needs. Counselors can play a vital role in developing this kind of support by being knowledgeable about the experiences of rural mothers and advocating for a holistic response to this identified need.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

in the development of this manuscript.

The research for this study was supported

by a grant from the Center for Rural

Innovation at Tennessee Tech University.

References

Albright, A. (1993). Postpartum depression: An overview. Journal of Counseling & Development, 71(3), 316–320. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1993.tb02219.x

American Counseling Association. (2014). ACA code of ethics. https://bit.ly/acacodeofethics

Bedaso, A., Adams, J., Peng, W., & Sibbritt, D. (2021). The relationship between social support and mental health problems during pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Reproductive Health, 18, 1–23. https://www.doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01209-5

Cho, H., Lee, K., Choi, E., Cho, H. N., Park, B., Suh, M., Rhee, Y., & Choi, K. S. (2022). Association between social support and postpartum depression. Scientific Reports, 12, 3128. https://www.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-07248-7

Choate, L. H., & Gintner, G. G. (2011). Prenatal depression: Best practice guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Counseling & Development, 89(3), 373–381. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2011.tb00102.x

Cirino, N. H., & Knapp, J. M. (2019). Perinatal posttraumatic stress disorder: A review of risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey, 74(6), 369–376. https://doi.org/10.1097/OGX.0000000000000680

Corrigan, C. P., Kwasky, A. N., & Groh, C. J. (2015). Social support, postpartum depression, and professional assistance: A survey of mothers in the Midwestern United States. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 24(1), 48–60. https://www.doi.org/10.1891/1058-1243.24.1.48

Darvill, R., Skirton, H., & Farrand, P. (2010). Psychological factors that impact on women’s experiences of first-time motherhood: A qualitative study of the transition. Midwifery, 26(3), 357–366. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2008.07.006

Davis-Floyd, R. (2004). Birth as an American rite of passage. University of California Press.

Dugan, A. G., & Barnes-Farrell, J. L. (2020). Working mothers’ second shift, personal resources, and self-care. Community, Work & Family, 23(1), 62–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2018.1449732

Eapen, D. J., Wambach, K., & Domian, E. W. (2019). A qualitative description of pregnancy-related social support experiences of low-income women with low birth weight infants in the Midwestern United States. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 23, 1473–1481. https://www.doi.org/10.1007/s10995-019-02789-2

Enlander, A., Simonds, L., & Hanna, P. (2022). “I want you to help me, you’re family”: A relational approach to women’s experience of distress and recovery in the perinatal period. Feminism & Psychology, 32(1), 62–80. https://www.doi.org/10.1177/09593535211047792

Federal Office of Rural Health Policy. (2022). List of rural counties and designated eligible census tracts in metropolitan counties. https://data.hrsa.gov/Content/Documents/tools/rural-health/forhpeligibleareas.pdf

Fenwick, J., Gamble, J., & Mawson, J. (2003). Women’s experiences of Caesarean section and vaginal birth after Caesarian: A birthrites initiative. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 9(1), 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-172X.2003.00397.x

Flynn, S. V., Korcuska, J. S., Brady, N. V., & Hays, D. G. (2019). A 15-year content analysis of three qualitative research traditions. Counselor Education and Supervision, 58(1), 49–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12123

Ford, E., & Ayers, S. (2009). Stressful events and support during birth: The effect on anxiety, mood and perceived control. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23(2), 260–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.07.009

Geller, P. A., Posmontier, B., Horowitz, J. A., Bonacquisti, A., & Chiarello, L. A. (2018). Introducing Mother Baby Connections: A model of intensive perinatal mental health outpatient programming. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 41(5), 600–613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-018-9974-z

Greenfield, M., Jomeen, J., & Glover, L. (2019). “It can’t be like last time” – Choices made in early pregnancy by women who have previously experienced a traumatic birth. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 56. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00056

Hine, R. H., Maybery, D., & Goodyear, M. J. (2017). Challenges of connectedness in personal recovery for rural mothers with mental illness. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(2), 672–682. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12353

Hung, P., Henning-Smith, C. E., Casey, M. M., & Kozhimannil, K. B. (2017). Access to obstetric services in rural counties still declining, with 9 percent losing services, 2004–14. Health Affairs, 36(9), 1663–1671. https://www.doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0338

Husserl, E. (1931). Ideas: General introduction to pure phenomenology (W. R. B. Gibson, Trans). Macmillan.

Kozhimannil, K. B., Casey, M. M., Hung, P., Prasad, S., & Moscovice, I. S. (2016). Location of childbirth for rural women: Implications for maternal levels of care. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 214(5), 661.E1–661.E10. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2015.11.030

Kozhimannil, K. B., Interrante, J. D., Henning-Smith, C., & Admon, L. K. (2019). Rural-urban differences in severe maternal morbidity and mortality in the US, 2007–15. Health Affairs, 38(12), 2077–2085. https://www.doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00805

Kroelinger, C. D., Brantley, M. D., Fuller, T. R., Okoroh, E. M., Monsour, M. J., Cox, S., & Barfield, W. D. (2021). Geographic access to critical care obstetrics for women of reproductive age by race and ethnicity. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 224(3), 304.E1–304.E11.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.08.042

Leagjeld, L. A., Waalkes, P. L., & Jorgensen, M. F. (2021). Mental health counselors’ perceptions of rural women clients. The Professional Counselor, 11(1), 86–101. https://doi.org/10.15241/lal.11.1.86

Letvak, S. (2002). The importance of social support for rural mental health. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 23(3), 249–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/016128402753542992

Milgrom, J., Hirshler, Y., Reece, J., Holt, C., & Gemmill, A. W. (2019). Social support—A protective factor for depressed perinatal women? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(8), 1426. https://www.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16081426

Miller, P. G. T., Sinclair, M., Gillen, P., McCullough, J. E. M., Miller, P. W., Farrell, D. P., Slater, P. F., Shapiro, E., & Klaus, P. (2021). Early psychological interventions for prevention and treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and post-traumatic stress symptoms in post-partum women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS ONE, 16(11), e0258170–e0258170.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258170

Molloy, E., Biggerstaff, D. L., & Sidebotham, P. (2021). A phenomenological exploration of parenting after birth trauma: Mothers perceptions of the first year. Women and Birth, 34(3), 278–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2020.03.004

Moustakas, C. E. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. SAGE.

National Board for Certified Counselors. (2023). NBCC code of ethics. https://bit.ly/NBCCCodeofEthics

Nidey, N., Tabb, K. M., Carter, K. D., Bao, W., Strathearn, L., Rohlman, D. S., Wehby, G., & Ryckman, K. (2020). Rurality and risk of perinatal depression among women in the United States. The Journal of Rural Health, 36(1), 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12401

Osterman, M. J. K., Hamilton, B. E., Martin, J. A., Driscoll, A. K., & Valenzuela, C. P. (2023). Births: Final data for 2021. National Vital Statistics Reports, 72(1), 1–52. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr72/nvsr72-01.pdf

Pfost, K. S., Stevens, M. J., & Matejcak, A. J., Jr. (1990). A counselor’s primer on postpartum depression. Journal of Counseling & Development, 69(2), 148–151. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1990.tb01476.x

Ruyak, S. L., Boursaw, B., & Cacari Stone, L. (2022). The social determinants of perinatal maternal distress. Journal of Rural Mental Health, 46(4), 277–284. https://www.doi.org/10/1037/rmh0000212

Smorti, M., Ponti, L., & Pancetti, F. (2019). A comprehensive analysis of post-partum depression risk factors: The role of socio-demographic, individual, relational, and delivery characteristics. Frontiers in Public Health, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00295

Vaezi, A., Soojoodi, F., Banihashemi, A. T., & Nojomi, M. (2019). The association between social support and postpartum depression in women: A cross-sectional study. Women and Birth, 32(2), e238–e242. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2018.07.014

Zamani, P., Ziaie, T., Lakeh, N. M., & Leili, E. K. (2019). The correlation between perceived social support and childbirth experience in pregnant women. Midwifery, 75, 146–151. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2019.05.002

Katherine M. Hermann-Turner, PhD, NCC, BC-TMH, LPC (TN), is an associate professor at Tennessee Tech University. Jonathan D. Wiley, PhD, NCC, LPC (VA), is an assistant professor at Tennessee Tech University. Corrin N. Brown, EdS, NCC, LPC-MHSP-Temp. (TN), is a doctoral candidate at Tennessee Tech University. Alyssa A. Curtis, MS, MA, is a graduate of Tennessee Tech University. Dessie S. Avila, MA, LPC-MHSP (TN), is a doctoral candidate at Tennessee Tech University. Correspondence may be addressed to Katherine M. Hermann-Turner, Tennessee Tech University, Box 5031, Cookeville, TN 38505, khturner@tntech.edu.