Jul 25, 2025 | Volume 15 - Issue 2

Alexandra Frank, Amanda C. DeDiego, Isabel C. Farrell, Kirby Jones, Amanda C. Tracy

State policies and school district regulation largely shape the roles and responsibilities of school counselors in the United States. The American School Counselor Association (ASCA) provides guidance on recommendations for school counseling practice; however, state policies may not align with guiding principles. Using a rubric informed by the ASCA National Model, we conducted a problem-driven content analysis to explore state policy alignment with the Define, Manage, Deliver, and Assess components of the model. Our findings indicate state policy differences between K–8 and 9–12 grade levels and within each rubric component. School counselors and school counselor educators can use these findings to support strategic advocacy efforts aimed at increased clarity around school counselors’ roles and responsibilities.

Keywords: content analysis, advocacy, state policy, school counseling, ASCA National Model

What is a school counselor? The profession has a long history of attempting to answer this question, not always successfully. Role confusion in school counseling was highlighted by Murray (1995) who stated that the roles of school counselors often vary from the printed job description. Murray attributed unclear counseling duties to misunderstandings about school counselors’ roles by stakeholders, such as administrators, parents, and students. Murray also found that differences in legislative definitions of school counseling contributed to role confusion. As an early act of advocacy in school counseling, Murray suggested developing a uniform definition of school counseling, advocating for that definition, and engaging in effective communication strategies among stakeholders as solutions to role confusion. Since this early movement to define school counseling roles, professional groups (e.g., The American School Counselor Association [ASCA]), academic organizations (e.g., School Counselors for MTSS), and professional conferences (e.g., The Evidence-Based School Counseling Conference and ASCA conference) have joined in the efforts to describe school counselor identity and roles. Despite these efforts, school counselors across the United States struggle with the lack of clarity in their roles (Bardhoshi & Duncan, 2009; Chandler et al., 2018).

School counselors’ impacts on student outcomes are well-documented (O’Connor, 2018). When describing the role and influence of school counselors, researchers point to improved student outcomes, such as decreased student behavior issues (Reback, 2010), increased student achievement (Carrell & Hoekstra, 2014), and increased college-going behavior (Hurwitz & Howell, 2014). School counselors’ roles in supporting student social–emotional health became particularly important when navigating the effects of COVID-19 (McCoy-Speight, 2021). However, Murray’s (1995) concern about legislative differences in defining the role of a school counselor remains. Despite evidence describing positive impacts of school counselors on student outcomes, the school counselor role is often misunderstood and continues to vary from state to state (Carey & Dimmitt, 2012). Recently, state differences were most pronounced in Texas Senate Bill 763 (2023), which proposed to equip chaplains to serve as school counselors, and in Florida’s emphasis on parents as resiliency coaches (Florida Governor’s Press Office, 2023). Additionally, factors such as organizational constraints (Alexander et al., 2022), student–counselor ratios (Kearney et al., 2021), and engagement in non-counseling duties (Blake, 2020; Camelford & Ebrahim, 2017; Chandler et al., 2018) continue to hinder the impact that school counselors can make within their school settings. Intrigued by Murray’s observation regarding the long-standing issues with school counseling roles and duties differing from state to state and recent state initiatives to supplement the role of a school counselor with chaplains or parents (e.g., Texas and Florida), we sought to explore how state-level policies and statutes define school counselor roles and responsibilities and how they align with national recommendations.

Defining School Counseling

Noting the need for a uniform definition of school counseling, we turned to ASCA. Although ASCA is not the only professional organization supporting school counselors, it has the longest history (formed in 1952) and largest membership (approximately 43,000). Additionally, ASCA exists for the explicit purpose of supporting school counselors by “providing professional development, enhancing school counseling programs, and researching effective school counseling practices” (n.d.-a, About ASCA section). ASCA (2023) defines school counseling as a comprehensive, developmental, and preventative support aimed at improving student outcomes. ASCA (n.d.-b) advocates for a united school counseling vision and voice among stakeholders. Despite their efforts, researchers, educational leaders, and state policymakers continue to hold varied perspectives about the definitions, needs, and roles of school counselors. Although ASCA (2019; 2023) clearly delineates appropriate and inappropriate school counseling roles and responsibilities, school counselors often find themselves asked to engage in activities deemed inappropriate by ASCA (Bardhoshi & Duncan, 2009; Chandler et al., 2018).

School counselors can use collaboration and advocacy to promote a more appropriate use of their time (McConnell et al., 2020) and to mediate feelings of burnout (Holman et al., 2019). Researchers have discussed the importance of advocacy as integral to pre–school counselor training (Havlik et al., 2019), individual school counseling practice (Perry et al., 2020), and system-wide professional unity (Cigrand et al., 2015). However, such efforts are often limited to a single school or district and often do not include state-level advocacy.

The ASCA National Model

To support their mission of improving student outcomes, ASCA (2019) recommends a national model as a framework for school counselors. The ASCA National Model is aligned with school counseling priorities, such as data-informed decision-making, systemic interventions, and developmentally appropriate care considerations. Implementation is associated with both student-facing and school counselor–facing benefits. In an introduction to a special issue on comprehensive school counseling programs, Carey and Dimmitt (2012) described findings across six statewide studies highlighting the relationship between program implementation and positive student outcomes, including improved attendance and decreases in rates of student discipline. Pyne (2011) and more recently Fye and colleagues (2022) demonstrated correlations between program implementation and school counselor job satisfaction. Pyne found that school counselors with administrative support and staff collaboration related to program implementation experienced higher rates of job satisfaction. Fye et al. noted that as implementation of the ASCA National Model increased, role ambiguity decreased and job satisfaction increased.

The ASCA National Model consists of four components: Define, Manage, Deliver, and Assess. We outline the model in Table 1 below.

Table 1

Four Components of The ASCA National Model

| Define |

Standards to support school counselors

School counselors are supported in implementation and assessment of a comprehensive school counseling program by existing standards such as the ASCA Mindsets & Behaviors, the ASCA Ethical Standards for School Counselors, and the ASCA School Counselor Professional Standards & Competencies. |

| Manage |

Effective and efficient implementation of a comprehensive school counseling program

ASCA outlines planning tools to support a program focus, program planning, and appropriate school counseling activities. |

| Deliver |

The actual delivery of a comprehensive school counseling program

School counselors implement developmentally appropriate activities and services to support positive student outcomes. School counselors engage in direct (e.g., instruction, appraisal and advisement, counseling) and indirect (e.g., consultation, collaboration, referrals) student services. ASCA (2019) stipulates that school counselors should spend 80% of their time in direct or indirect student services. School counselors should spend 20% or less of their time on school support activities and/or program planning. |

| Assess |

Data-driven accountability measures to assess the efficacy of program delivery

School counselors are charged with evaluating their program’s efficacy and implementing improvements, based on student needs. School counselors should demonstrate that students are positively impacted because of the counseling program. |

We extend the Assess component to also include research-based examples on factors contributing to a school counselor’s efficacy. Such factors include student–school counselor ratios. For decades, ASCA has advocated for a student–school counselor ratio of 250:1 as well as broader support for school counselor roles (Kearney et al., 2021). Yet, data from the 2021–2022 school year put the average national student–school counselor ratio at 408:1 (National Center for Education Statistics [NCES], 2023). Researchers demonstrate that schools with ASCA-approved ratios experience increased student attendance, higher test scores, and improved graduation rates (e.g., Carey et al., 2012; Carrell & Carrell, 2006; Goodman-Scott et al., 2018; Lapan et al., 2012).

Alternatively, Donohue and colleagues (2022) demonstrated that higher ratios relate to worse outcomes for students. Notably, minoritized students and their school communities often face the brunt of increased student–school counselor ratios (Donohue et al., 2022; Education Trust, 2018). Thus, the ASCA alignment is not only concerned with improved student outcomes but also with the equitable provision of mental health services. Given the role ASCA plays in advocating for and structuring the school counselor’s role and responsibilities, we chose to use the components of the ASCA National Model (2019) as a theoretical framework guiding our study. We have incorporated our theoretical framework throughout, including data collection, data analysis, results, discussion, and implications.

Method

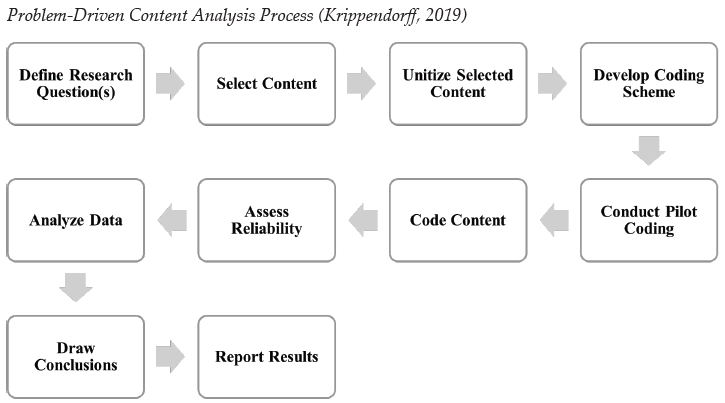

The purpose of our study was to understand how state policies align with the ASCA National Model. We analyzed state policies defining and guiding the practice of school counseling. In any inquiry, the type and characteristics of the data available should dictate the research methods (Flick, 2015). Content analysis allows researchers to identify recurring themes, patterns, and trends (Krippendorff, 2019). By systematically coding and categorizing content, researchers can uncover insights that might not be immediately apparent through casual observation. Additionally, it enables researchers to analyze large volumes of data in a systematic and replicable manner, reducing the impact of personal bias and increasing the reliability of findings. Because of these factors, we found content analysis to be the best method for our inquiry. We chose a subtype of content analysis—problem-driven content analysis (Krippendorff, 2019). Problem-driven content analysis aims to answer a research question. The research question guiding our analysis was: How are state policies aligned or misaligned with the ASCA National Model?

Sample

Using the State Policy Database maintained by the National Association of State Boards of Education (NASBE; 2023), we pulled current policies from all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia (N = 51) that dictate the role of school counselors and school counseling services. As ASCA (n.d.-c) describes, terms used for school counseling services can vary, and although “school counselor” is favorable to “guidance counselor,” both terms may be found. However, in NASBE’s State Policy Database, the category was specifically listed as “counseling, psychological, and social services,” and the subcategory was listed as “school counseling—elementary” and “school counseling—secondary” (NASBE, 2023). We included policies that govern kindergarten through eighth grade (K–8) and ninth through 12th grade (9–12). Data included all policies related to school counseling delivery and certification, with State Policy Databases sorted into policies governing K–8 (n = 156, 47.42%) and 9–12 (n = 173, 52.58%) levels, for a total of 329 policies.

Design

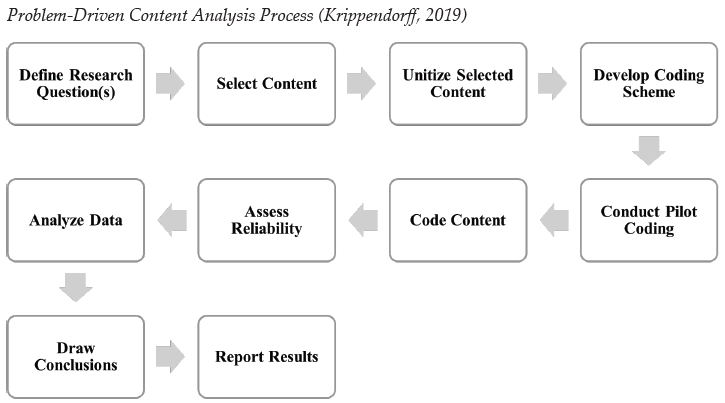

From our research question to data reporting, we followed the problem-driven content analysis steps (see Figure 1). We collected language from the policies, including policy type and policy name, and then determined if school counseling was encouraged, recommended, or not specified as either. We built a spreadsheet to divide, define, and identify the state policies into sampling units. We divided them into originating state, policy type, requirements for having school counselors in schools, policy name, and summary of the policy. Additionally, we separated the data into K–8 and 9–12 education designations.

Figure 1

Problem-Driven Content Analysis Process (Krippendorff, 2019)

The analytical process began with filtering policies for inclusion outlined in our selection criteria. We built a spreadsheet to divide, define, and identify the legislative bills into sampling units. We focused on dividing them into originating state, bill number, year, subcategory, and summary of the bill. After completing the spreadsheet with all the data, Kirby Jones and Amanda C. Tracy tested our coding frame on a sample of text. Although content analysis does not require piloting, Schreier (2012) suggested piloting around 20% of the data to test the reliability of the coding frame. We used 20% of our data (n = 66) to conduct pilot coding.

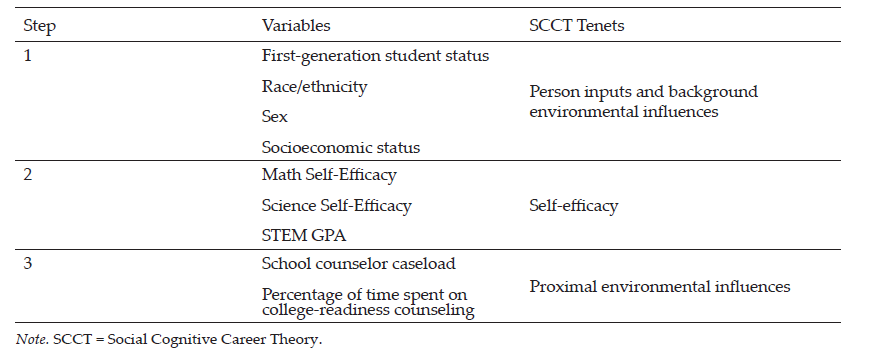

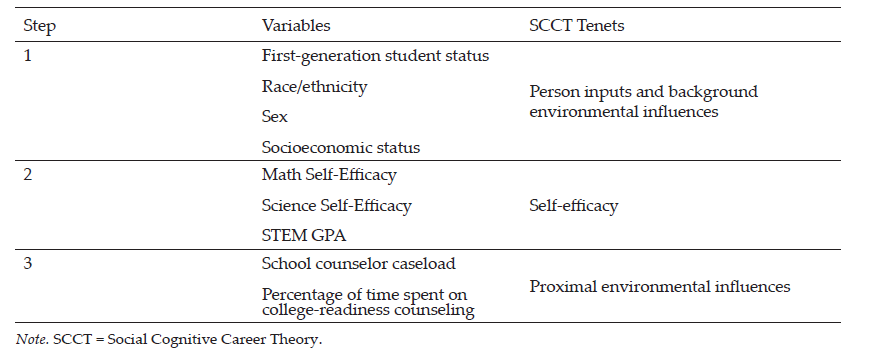

We approached the data analysis deductively, with the components of the ASCA National Model (2019) acting as our initial codes. Prior to analysis, we created a coding rubric that we used to analyze each state’s school counseling policy (see Table 2). We used the four components of the ASCA National Model as the rubric criteria: Define, Manage, Deliver, and Assess. Within each criterion, we developed standards ranging from 1 point to 5 points. We chose point ranges based on the information within each criterion. For example, the Define criterion included three standards for 5 total points. We awarded 1 point if a state required (versus recommended) school counselors in school; we awarded 1 point if a state required school counselors to be licensed and/or certified based on a graduate degree; and we awarded 3 points if a state specifically described all three focus areas of school counseling—academic, college/career, and social/emotional.

Alexandra Frank, Amanda C. DeDiego, and Isabel C. Farrell were involved in creating the rubric and completing initial pilot coding to ensure the usability and utility of the rubric. All team members met throughout the process to ensure workability and fidelity. Following initial testing, each coding pair was trained to appropriately analyze state-level policy data using the rubric. Before finalizing rubric metrics for each state, all team members met again to review metrics and to determine final scores for each state. Importantly, individual state-level rubric scores do not indicate grades, but rather demonstrate evidence of alignment between state-level policy as it is written and the ASCA National Model (2019).

Table 2

Rubric to Evaluate State Policy for Adherence to the ASCA National Model

| Aspects of the ASCA National Model |

|

Define

5 points

|

Manage

1 point |

Deliver

1 point |

Assess

2 points |

|

Required

1 point

|

Education

1 point |

Focus

3 points |

Implementation

1 point |

Use of Time

1 point |

Accountability

1 point |

Ratio

1 point

|

| State has provisions requiring school counselors |

Requires school counselors to be licensed/certified |

Areas of focus include:

(1) academic,

(2) college/career,

(3) social/emotional |

Role includes appropriate school counseling activities |

80% of time spent in direct/indirect services supporting student achievement, attendance, and discipline |

Evaluation of school counselor role included |

Maximum

of 250:1

|

Research Team

Our research team consisted of two counselor educators, two counselor education doctoral students, and one master’s-level counseling student. We began meeting as a research team in summer 2023. Conceptualization, data collection, and analysis occurred throughout the fall, ending in December 2023. Frank, DeDiego, and Farrell continued with edits and writing in 2024. Varying counseling backgrounds (including clinical mental health and school counseling), education settings (e.g., urban, rural, research, teaching), and personal identities were represented. All members are united by a passion for mentorship and advocacy. Additionally, DeDiego and Farrell provided expertise in legislative advocacy and content analysis, and Frank and Tracy provided expertise in school counseling. All members are affiliated with counseling programs accredited by the Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. Frank, DeDiego, and Farrell designed the coding frame and trained Jones and Tracy on the coding process. Frank, DeDiego, and Farrell also resolved any coding conflicts. For example, if a state regulation was unclear, Frank, DeDiego, and Farrell met and decided what code would apply. All members of the research team communicated via email, Google Docs, and/or Zoom meetings to build consensus through the data collection and data analysis processes.

Trustworthiness

To enhance trustworthiness in this study, we followed the checklist for content analysis developed by Elo et al. (2014), which includes three phases: preparation, organization, and reporting. The preparation phase involves determining the most appropriate data source to address the research question and the appropriate scope of the content and analysis. In this phase, we determined the focus of the project to be policy defining school counselor roles; thus, state-level legislation was the most appropriate data source. Use of the NASBE (2023) database offered a means of limiting scope and focus of the content. Using deductive coding (McKibben et al., 2022), we first developed the rubric coding framework based on the ASCA National Model (2019) and then conducted pilot coding to test the framework.

During the organization phase, the checklist addresses organizing coding and theming strategies. We first conducted pilot coding to establish how to apply the ASCA National Model (2019) to coding legislation. We evaluated the content using the rubric to determine how the legislation aligned with the ASCA National Model. Elo et al. (2014) suggested researchers also determine how much interpretation will be used to analyze the data. The coding framework using the ASCA National Model offers structure to this interpretation. Data were coded separately for trustworthiness by Jones and Tracy. Then we met to compare coding. If there was discrepancy, one of us reviewed the data in order to reach a two-thirds majority for all of the coding. By the end of the process, all coding met the threshold of two-thirds majority agreement.

In the Elo et al. (2014) checklist, the reporting phase addresses how to represent and share the results of the analysis. This includes ensuring that categories used to report findings capture the data well and that results are clear and understandable for targeted audiences. The use of a rubric framework offers a clear method to represent and share results of the analysis process.

Results

Our results highlighted trends in the scope and practice of school counseling across the United States. We organized results by rubric strands (Table 3) and by state, analyzing results for K–8 (Appendix A) and 9–12 (Appendix B). We further describe our results within each strand of the ASCA National Model (2019): Define, Manage, Deliver, and Assess.

Table 3

Summary of Rubric Outcomes by Category

|

K–8 |

9–12 |

|

Yesa |

Nob |

Yesa |

Nob |

| Required |

37 (72.55%) |

14 (27.45%) |

40 (78.73%) |

11 (21.57%) |

| Education |

40 (78.43%) |

11 (21.57%) |

50 (98.04%) |

1 (1.96%) |

| Focus

Academic

College/Career

Social/Emotional |

35 (68.63%)

37 (72.55%)

35 (68.63%) |

16 (31.37%)

14 (27.45%)

16 (31.37%) |

40 (78.43%)

41 (80.39%)

40 (78.43%) |

11 (21.57%)

10 (19.61%)

11 (21.57%) |

| Implementation |

34 (66.67%) |

17 (33.33%) |

36 (70.59%) |

15 (29.41%) |

| Use of Time |

17 (33.33%) |

34 (66.76%) |

10 (19.61%) |

41 (80.39%) |

| Accountability |

21 (41.18%) |

30 (58.82%) |

29 (56.86%) |

22 (43.14%) |

| Ratio |

2 (3.92%) |

49 (96.08%) |

3 (5.88%) |

48 (94.12%) |

aIndicates awarding of a point, as outcome was represented in the policy.

bIndicates no point was awarded, as outcome was not represented in the policy.

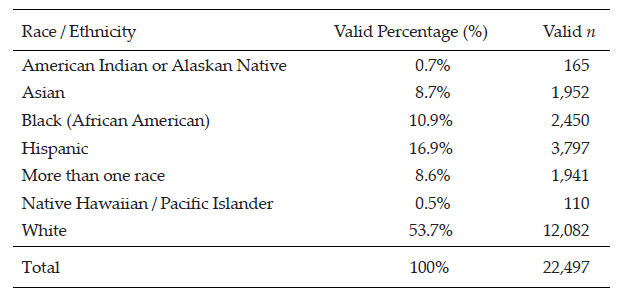

In the state policies, school counselors were designated as required, encouraged, or not specified. For the K–8 level, 72.55% (n = 37) of states required school counselors in schools, 19.61% (n = 10) encouraged the presence of school counselors, and 7.84% (n = 4) of states did not specify a requirement of school counselor presence. At the 9–12 level, 78.73% (n = 40) of states required school counselors in schools, 19.60% (n = 10) encouraged the presence of school counselors, and 1.96% (n = 1) of states did not specify a requirement of school counselor presence.

The category of not specified included policies that were uncodified or policies that did not address the requirement of school counselors at all. The majority of states required school counselors at the K–8 (n = 37, 72.55%) and 9–12 (n = 40, 78.73%) levels. At the K–8 level, one state had a policy that was uncodified (Michigan) and three did not address the requirements of school counselors (i.e., Hawaii, South Dakota, Wyoming). At the 9–12 level, one state had an uncodified policy (Hawaii) and one did not specify a requirement for school counselors (South Dakota). Forty states (80%) for K–8 and 50 states (98.04%) for 9–12 required school counselors to have a license or certification in school counseling. The only state that did not require certification or licensure was Florida. Thirty-five states (70%) for K–8 and 40 states (78.43%) for 9–12 described the role of a school counselor as supporting students’ academic success. Thirty-seven states (72.54%) for K–8 and 41 states (80.39%) for 9–12 described the role of a school counselor as supporting college and career readiness. Finally, 35 states (68.63%) for K–8 and 40 states (78.43%) for 9–12 described the role of a school counselor as supporting students’ social and emotional growth.

Within the Manage aspect of the ASCA National Model (2019), we determined if the state outlined appropriate school counseling activities in alignment with ASCA recommendations in policy or statute (e.g., small groups, counseling, classroom guidance, preventative programs). Thirty-four states (66.67%) for K–8 and 36 states (70.59%) for 9–12 outlined school counseling activities in their policy. For Deliver, only 17 states (33.33%) for K–8 and 10 states (20%) for 9–12 outlined whether or not the majority of school counselors’ time should be spent providing direct and indirect student services.

Moreover, for the Assess category, we evaluated whether the state policy required school counselors to do an evaluation of their role and/or counseling services. Twenty-one states (58.82%) for K–8 and 29 states (56.86%) for 9–12 outlined evaluation requirements. Finally, we evaluated whether the state complied with the ASCA student–school counselor ratio of 250:1. Two states for K–8 (3%; i.e., New Hampshire, Vermont) and three states for 9–12 (5.9%; i.e., Michigan, New Hampshire, Vermont) complied with the recommended ratios. A few states (i.e., Colorado, Illinois, Kentucky, Minnesota, Montana) recommended that state districts follow the ASCA 250:1 recommendation, but it was not a requirement; those state ratios exceeded 250:1.

Next, we examined overall trends of compliance by grade level and by state. For K–8, eight states (15.69%) had higher scores of ASCA National Model (2019) compliance (i.e., Arkansas, Maine, Nevada, New Hampshire, Oregon, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Wisconsin) compared to other states in our dataset with a score of 8 out of 9. For 9–12, six states (11.76%) scored 8 out of 9 (i.e., Arkansas, Maine, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Wisconsin). Excluding Hawaii, South Dakota, and Wyoming, because their state policies did not address the requirements of K–8 school counselors, the states with the lowest scores of ASCA National Model compliance, with 1 out of 9 for K–8 were Alabama, Maryland, Missouri, and North Dakota (n = 4, 7.8%). For 9–12 state policy, two states (3.9%)scored 1 out of 9 (i.e., Massachusetts, South Dakota).

Discussion

Given ASCA’s (n.d.-b) advocacy efforts to develop a unified definition of school counseling, there is a need to assess how those advocacy efforts translate to state policy. Although individual state and district policies shed light on existing discrepancies between school counselor roles and responsibilities, our analysis also provides evidence of alignment with the ASCA National Model (2019) in some areas. These results can inform strategic efforts for further alignment. School counselors can use advocacy to support their role and promote responsibilities more aligned with the ASCA National Model (McConnell et al., 2020). We outline our discussion by again utilizing the four components of the ASCA National Model as a conceptual framework.

Define

Our findings suggest that the Define component of the ASCA National Model (2019) is well-represented in state and district policies. Although our results highlight differences in policy governing practice in K–8 and 9–12 schools, for the most part, all state and district policies required or encouraged the presence of a school counselor. Additionally, the vast majority of states required that individuals practicing as school counselors hold the appropriate licensure and/or certification. Similarly, most state and district policies defined a school counselor’s role as contributing to students’ academic, college/career, and/or social/emotional development. Vigilance in advocacy efforts remains important, as language in policy can change with each legislative session. For example, Texas Senate Bill No. 763 (2023) introduced legislation allowing chaplains to serve in student support roles instead of school counselors. The Lone Star State School Counselor Association (2023) quickly took action with a published brief condemning the language in the bill. As a result of advocacy efforts, lawmakers changed the verbiage in the bill to hire chaplains in addition to school counselors, rather than in lieu of them.

Similarly, Florida’s First Lady, Casey DeSantis (Florida Governor’s Press Office, 2023), announced a shift in counseling services to emphasize resiliency and include resiliency coaches—a role in which “moms, dads, and community members will be able to take training covering counseling standards and resiliency education standards” and provide a “first layer of support to students” (para. 8). Although the Florida School Counselor Association emphasizes advocacy efforts, it has not yet published a response to the changes in Florida’s resilience instruction and support plans (Weatherill, 2023). The legislation in Texas and Florida and the response from state-level school counselor associations highlight, once again, the importance of advocacy for creating and maintaining a uniform definition of school counseling.

Manage

Although ASCA clearly defines appropriate and inappropriate school counseling activities, state policy is less specific on codifying the appropriate use of school counselors’ time and resources. Although most states encouraged appropriate school counseling activities, states did not specifically define appropriate school counseling activities or provide protection around school counselors’ time to implement appropriate school counseling activities. Such findings are consistent with the literature (Bardhoshi & Duncan, 2009; Chandler et al., 2018). Florida’s K–8 policy suggests that school counselors should implement a program that suits the school and department, whereas some states’ K–8 policy, such as New Jersey’s, recommends incorporating the ASCA National Model (2019). Several states include uncodified policy addressing the implementation of a school counseling program. However, as such recommendations are not codified into policy, they do not dictate the day-to-day activities of school counselors. Interestingly, new legislation introducing support roles for chaplains and family/community members only bolsters the need to protect school counselors’ time. Texas Senate Bill No. 763 references the need for support, services, and programming. Florida First Lady Casey DeSantis similarly emphasizes the need for support and mentorship. School counselors are trained professionals equipped to support student outcomes (ASCA, 2019). One wonders whether legislative efforts introducing chaplains and family members would be needed if school counselors’ time was protected in ways to better support students with appropriate school counseling duties. Thus, there remains an opportunity for increased advocacy surrounding the implementation of school counseling programs with specific attention on appropriate versus inappropriate school counseling activities.

Deliver

ASCA suggests that school counselors should spend 80% of their time in direct/indirect services to support student outcomes. Such efforts are pivotal, as research suggests that school counselors play a key role in supporting student outcomes (e.g., Carey & Dimmitt, 2012; O’Connor, 2018). Researchers indicate that school counselors within a comprehensive school counseling program play an integral role in supporting improved student attendance (Carey & Dimmitt, 2012), graduation rates (Hurwitz & Howell, 2014), and academic performance (Carrell & Hoekstra, 2014). However, few states support student outcomes by codifying a school counselor’s use of time into policy. Idaho’s 9–12 policy instructs school counselors to use most of their time on direct services. While not equivalent to ASCA’s 80%, such efforts represent a start to protecting school counselors’ time and ensuring that school counselors are able to make the impact they are well-trained to in their school settings. Similar to Manage, current legislative efforts only highlight the importance of school counselors spending a majority of their time supporting students through direct services.

Assess

ASCA continues to focus their advocacy efforts on student–school counselor ratios with good reason; our findings indicate that 2% of K–8 state and district policies and 3% of 9–12 policies specifically outlined a 250:1 ratio that aligns with ASCA recommendations. Yet, researchers demonstrate that reduced student–counselor ratios support improved student outcomes (Carey et al., 2012; Carrell & Carrell, 2006; Goodman-Scott et al., 2018; Lapan et al., 2012). Further, minoritized students and their communities often face the negative consequences of increased student–counselor ratios (Donohue et al., 2022). As such, further advocacy around student–school counselor ratios is also needed from an equity perspective. Some states, such as Colorado, Illinois, Kentucky, and Montana, recommended ASCA ratios, but as is the case with appropriate versus inappropriate school counseling activities, without policy “teeth” to enforce recommendations, school counselors are often continuing to practice in settings that far exceed ASCA ratios, as is consistent with recent findings (NCES, 2023).

Although many states did not codify policies aligned with the ASCA National Model (2019), several states (North Dakota, New Jersey, Delaware) made reference to the ASCA National Model and recommended alignment. Our analysis supports previous research indicating that advocacy works (Cigrand et al., 2015; Havlik et al., 2019; Holman et al., 2019; McConnell et al., 2020; Perry et al., 2020). Our findings also highlight the value of supporting professional identity through membership in both national organizations and state-level advocacy groups.

Implications

We explored implications for school counselor educators, school counselors, and school counseling advocates. School counselor educators must prepare future school counselors for their roles as advocates. Counselor educators also play an important role in equipping future school counselors with an understanding of the landscape of the profession (McMahon et al., 2009). As such, including state-level policy and district-level conversations in curriculum helps connect counseling students with the evolving policies guiding their work. The rubric created for this research offers a valuable tool to explore state and school district alignment with the ASCA National Model (2019) and demonstrate areas to focus advocacy efforts. Counseling programs often participate in advocacy efforts, such as Hill Day. School counselor educators can use state-level and district-level policy as a springboard to promote specific advocacy efforts with state and local legislation. On a local level, school counselor educators can use our rubric to frame practice conversations for future school counselors to prepare for future conversations with school principals. Finally, school counselor educators can continue engaging in policy-level research to support ongoing school counseling advocacy. School counselor educators can further illuminate the impacts of school counseling policy by describing perspectives of practicing school counselors. School counselor educators can also engage in quantitative research methods to study the relationships between school counselor satisfaction and state policy adherence to the ASCA National Model (2019).

School counselors can use our rubric to analyze alignment of school districts when examining job descriptions during their job searches. School counselors could also use the rubric as part of the evaluation component of a comprehensive school counseling program. From our analysis, it appears most imperative that advocacy efforts focus on school counselors’ use of time and student–counselor ratios. Using data, school counselors can continue to advocate for their role to become more closely aligned to ASCA’s recommendations. Kim et al. (2024) described the “urgent need” (p. 233) for school counselors to engage in outcome research. We hope that our framework provides a tool for school counselors to engage in evaluation and advocacy based on our findings. However, school counselors should not be alone in their advocacy efforts. School counseling advocates, including educational stakeholders, counselors, school counselor educators, and educational policymakers, should continue supporting school counselors by advocating on their behalf at the district, state, and national level.

Future research may focus on the disconnect between state policy and how the districts enact those policies. A content analysis comparing state policy to district rules, regulations, and practices is needed to understand how state policy and district practices align. Finally, although there is frequent legislative advocacy from ASCA, there is a lack of data on state legislators’ knowledge about the ASCA National Model (2019) and ASCA priorities. School counseling researchers can use qualitative methods to interview state legislators, especially after events such as Hill Day, to better detail what legislators understand about the roles and impacts of school counselors.

Limitations

The purpose of content analysis was to discover patterns in large amounts of data through a systematic coding process (Krippendorff, 2019). We are all professional counselors or counselors-in-training with a passion for advocacy. Thus, as with any qualitative work, there is potential for bias in the coding process. Interrater reliability was used to mitigate this risk. There are many factors that impact the practice of school counseling beyond state-level policy. District policies and school leadership vastly impact the ways that state policy is interpreted and enacted in schools. Thus, this content analysis represents only school counseling regulation as described in policy and may not fully represent the day-to-day experiences of school counselors.

Conclusion

Although confusion and role ambiguity muddy the school counseling profession, advocacy efforts and outcome research act as cleansers. By providing a rubric to assess alignment between state policy and the ASCA National Model, we hoped to clarify the current state of school counseling practice and provide a helpful tool for future school counselors, current practitioners, educational leaders, and policymakers.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Alexander, E. R., Savitz-Romer, M., Nicola, T. P., Rowan-Kenyon, H. T., & Carroll, S. (2022). “We are the heartbeat of the school”: How school counselors supported student mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Professional School Counseling, 26(1b). https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X221105557

American School Counselor Association. (n.d.-a). About ASCA. https://www.schoolcounselor.org/About-ASCA

American School Counselor Association. (n.d.-b). Advocacy and legislation. https://bit.ly/ASCAadvocacylegislation

American School Counselor Association (n.d.-c). Guidance counselor vs. school counselor. https://www.schoolcounselor.org/getmedia/c8d97962-905f-4a33-958b-744a770d71c6/Guidance-Counselor-vs-School-Counselor.pdf

American School Counselor Association. (2019). ASCA National Model: A framework for school counseling programs (4th ed.).

American School Counselor Association. (2023). The role of the school counselor. https://www.schoolcounselor.org/getmedia/ee8b2e1b-d021-4575-982c-c84402cb2cd2/Role-Statement.pdf

Bardhoshi, G., & Duncan, K. (2009). Rural school principals’ perception of the school counselor’s role. The Rural Educator, 30(3), 16–24. https://doi.org/10.35608/ruraled.v30i3.445

Blake, M. K. (2020). Other duties as assigned: The ambiguous role of the high school counselor. Sociology of Education, 93(4), 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040720932563

Camelford, K. G., & Ebrahim, C. H. (2017). Factors that affect implementation of a comprehensive school counseling program in secondary schools. Vistas Online, 1–10.

Carey, J., & Dimmitt, C. (2012). School counseling and student outcomes: Summary of six statewide studies. Professional School Counseling, 16(2), 146–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X0001600204

Carey, J., Harrington, K., Martin, I. M., & Hoffman, D. (2012). A statewide evaluation of the outcomes of the implementation of ASCA National Model school counseling programs in rural and suburban Nebraska high schools. Professional School Counseling, 16(2), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X0001600203

Carrell, S. E., & Carrell, S. A. (2006). Do lower student to counselor ratios reduce school disciplinary problems? The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 5(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.2202/1538-0645.1463

Carrell, S. E., & Hoekstra, M. (2014). Are school counselors an effective education input? Economics Letters, 125(1), 66–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2014.07.020

Chandler, J. W., Burnham, J. J., Riechel, M. E. K., Dahir, C. A., Stone, C. B., Oliver, D. F., Davis, A. P., & Bledsoe, K. G. (2018). Assessing the counseling and non-counseling roles of school counselors. Journal of School Counseling, 16(7), n7. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1182095.pdf

Cigrand, D. L., Havlik, S. G., Malott, K. M., & Jones, S. G. (2015). School counselors united in professional advocacy: A systems model. Journal of School Counseling, 13(8), n8. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1066331.pdf

Donohue, P., Parzych, J. L., Chiu, M. M., Goldberg, K., & Nguyen, K. (2022). The impacts of school counselor ratios on student outcomes: A multistate study. Professional School Counseling, 26(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X221137283

Education Trust. (2018). Funding gaps: An analysis of school funding equity across the U.S. and within each state.

https://edtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/FundingGapReport_2018_FINAL.pdf

Elo, S., Kääriäinen, M., Kanste, O., Pölkki, T., Utriainen, K., & Kyngäs, H. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. SAGE Open, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014522633

Flick, U. (2015). Qualitative Inquiry—2.0 at 20? Developments, trends, and challenges for the politics of research. Qualitative Inquiry, 21(7), 599–608. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800415583296

Florida Governor’s Press Office. (2023, March 22). First lady Casey DeSantis announces next steps in Florida’s first-in-the-nation approach to create a culture of resiliency and incentivize parental involvement in schools [Press release]. https://www.flgov.com/eog/news/press/2023/first-lady-casey-desantis-announces-next-steps-floridas-first-nation-approach

Fye, H. J., Schumacker, R. E., Rainey, J. S., & Guillot Miller, L. (2022). ASCA National Model implementation predicting school counselors’ job satisfaction with role stress mediating variables. Journal of Employment Counseling, 59(3), 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1002/joec.12181

Goodman-Scott, E., Sink, C. A., Cholewa, B. E., & Burgess, M. (2018). An ecological view of school counselor ratios and student academic outcomes: A national investigation. Journal of Counseling & Development, 96(4), 388–398. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12221

Havlik, S. A., Malott, K., Yee, T., DeRosato, M., & Crawford, E. (2019). School counselor training in professional advocacy: The role of the counselor educator. Journal of Counselor Leadership and Advocacy, 6(1), 71–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/2326716X.2018.1564710

Holman, L. F., Nelson, J., & Watts, R. (2019). Organizational variables contributing to school counselor burnout: An opportunity for leadership, advocacy, collaboration, and systemic change. The Professional Counselor, 9(2), 126–141. https://doi.org/10.15241/lfh.9.2.126

Hurwitz, M., & Howell, J. (2014). Estimating causal impacts of school counselors with regression discontinuity designs. Journal of Counseling & Development, 92(3), 316–327. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00159.x

Kearney, C., Akos, P., Domina, T., & Young, Z. (2021). Student-to-school counselor ratios: A meta-analytic review of the evidence. Journal of Counseling & Development, 99(4), 418–428. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12394

Kim, H., Molina, C. E., Watkinson, J. S., Leigh-Osroosh, K. T., & Li, D. (2024). Theory-informed school counseling: Increasing efficacy through prevention-focused practice and outcome research. Journal of Counseling & Development, 102(2), 226–238. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12507

Krippendorff, K. (2019). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (4th ed.). SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781071878781

Lapan, R. T., Gysbers, N. C., Stanley, B., & Pierce, M. E. (2012). Missouri professional school counselors: Ratios matter, especially in high-poverty schools. Professional School Counseling, 16(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X0001600207

Lone Star State School Counselor Association. (2023). SB 763 and Texas school counselors. https://www.lonestarstateschoolcounselor.org/news_issues

McConnell, K. R., Geesa, R. L., Mayes, R. D., & Elam, N. P. (2020). Improving school counselor efficacy through principal-counselor collaboration: A comprehensive literature review. Mid-Western Educational Researcher, 32(2). https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1063&context=mwer

McCoy-Speight, A. (2021). The school counselor’s role in a post-COVID-19 era. In I. Fayed & J. Cummings (Eds.), Teaching in the post COVID-19 era (pp. 697–706). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74088-7_68

McKibben, W. B., Cade, R., Purgason, L. L., & Wahesh, E. (2022). How to conduct a deductive content analysis in counseling research. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 13(2), 156–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/21501378.2020.1846992

McMahon, H. G., Mason, E. C. M., & Paisley, P. O. (2009). School counselor educators as educational leaders promoting systemic change. Professional School Counseling, 13(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X0901300207

Murray, B. A. (1995). Validating the role of the school counselor. The School Counselor, 43(1), 5–9. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23901422

National Association of State Boards of Education. (2023). State policy database. https://statepolicies.nasbe.org

National Center for Education Statistics. (2023). National teacher and principal survey. Institute of Education Sciences. https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/ntps

O’Connor, P. J. (2018). How school counselors make a world of difference. Phi Delta Kappan, 99(7), 35–39.

https://kappanonline.org/oconnor-school-counselors-make-world-difference

Perry, J., Parikh, S., Vazquez, M., Saunders, R., Bolin, S., & Dameron, M. L. (2020). School counselor self-efficacy in advocating for self: How prepared are we? Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 13(4), 5. https://research.library.kutztown.edu/jcps/vol13/iss4/5

Pyne, J. R. (2011). Comprehensive school counseling programs, job satisfaction, and the ASCA National Model. Professional School Counseling, 15(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X1101500202

Reback, R. (2010). Schools’ mental health services and young children’s emotions, behavior, and learning. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 29(4), 698–725. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.20528

S.B. 763, 88th Cong. (2023). https://capitol.texas.gov/BillLookup/History.aspx?LegSess=88R&Bill=SB763

Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice. SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781529682571

Weatherill, A. (2023). Florida Department of Education update. Florida Department of Education. https://www.myflfamilies.com/sites/default/files/2023-11/DOE%20Update-DCF%20committee%20meeting%206-28-23.pdf

Appendix A

Breakdown of State Rubric Scores for ASCA Alignment for K–8 Schools

|

Define

(5 points)

|

Manage

(1 point) |

Deliver

(1 point) |

Assess

(2 points) |

State Score

(9 points) |

|

Required

(1 point)

|

Education

(1 point) |

Focus

(3 points) |

Implementation

(1 point) |

Use of Time

(1 point) |

Accountability

(1 point) |

Ratio

(1 point) |

Total |

| AL |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| AK |

0 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

5 |

| AZ |

0 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

6 |

| AR |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

8 |

| CA |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| CO |

0 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

6 |

| CT |

0 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| DE |

1 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

| DC |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

| FL |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

| GA |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

| HI |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| ID |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

| IL |

0 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| IN |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

| IA |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

| KA |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

| KY |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

| LA |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

| ME |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

8 |

| MD |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| MA |

0 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

| MI |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

| MN |

0 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

| MI |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

| MO |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| MT |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

| NE |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

| NV |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

8 |

| NH |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

8 |

| NJ |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

4 |

| NM |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| NY |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| NC |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

| ND |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| OH |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

| OK |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| OR |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

8 |

| PA |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

8 |

| RI |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

| SC |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

| SD |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| TN |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

| TX |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

| UT |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

| VT |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

6 |

| VA |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

| WA |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

| WV |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

8 |

| WI |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

8 |

| WY |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Total |

37 |

40 |

107 |

34 |

17 |

21 |

2 |

– |

Note. Categories refer to the ASCA National Model (2019).

Appendix B

Breakdown of State Rubric Scores for ASCA Alignment for 9–12 Schools

|

Define

(5 points)

|

Manage

(1 point) |

Deliver

(1 point) |

Assess

(2 points) |

State Score

(9 points) |

|

Required

(1 point)

|

Education

(1 point) |

Focus

(3 points) |

Implementation

(1 point) |

Use of Time

(1 point) |

Accountability

(1 point) |

Ratio

(1 point) |

Total |

| AL |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

| AK |

0 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

| AZ |

0 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

6 |

| AR |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

8 |

| CA |

0 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

6 |

| CO |

0 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

6 |

| CT |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| DE |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| DC |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

| FL |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

4 |

| GA |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| HI |

0 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

| ID |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

| IL |

0 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| IN |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

| IA |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| KA |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

| KY |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

4 |

| LA |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

| ME |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

8 |

| MD |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

6 |

| MA |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| MI |

0 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

7 |

| MN |

0 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

6 |

| MI |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

| MO |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| MT |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

| NE |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

| NV |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| NH |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

8 |

| NJ |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

| NM |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| NY |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| NC |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

4 |

| ND |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

| OH |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

| OK |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| OR |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

| PA |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

8 |

| RI |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

| SC |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| SD |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| TN |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| TX |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| UT |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

| VT |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

6 |

| VA |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

| WA |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

| WV |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

8 |

| WI |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

8 |

| WY |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

| Total |

40 |

50 |

121 |

36 |

10 |

29 |

3 |

– |

Note. Categories refer to the ASCA National Model (2019).

Alexandra Frank, PhD, NCC, is an assistant professor at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. Amanda C. DeDiego, PhD, NCC, ACS, BC-TMH, LPC, is an associate professor at the University of Wyoming. Isabel C. Farrell, PhD, NCC, LPC, is an associate professor at Wake Forest University. Kirby Jones, MA, LCMHCA, is a licensed counselor at Camel City Counseling. Amanda C. Tracy, MS, NCC, PPC, is a doctoral candidate at the University of Wyoming. Correspondence may be addressed to Alexandra Frank, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, School of Professional Studies, 651 McCallie Ave, Room 105D, Chattanooga, TN 37403, Alexandra-Frank@utc.edu.

Oct 31, 2023 | Volume 13 - Issue 3

Nancy Chae, Adrienne Backer, Patrick R. Mullen

All counseling graduate students participate in fieldwork experiences and engage in supervision to promote their professional development. School counseling trainees complete these experiences in the unique context of elementary and secondary school settings. As such, school counselors-in-training (SCITs) may seek to approach supervision with specific strategies tailored for the roles, responsibilities, and dispositions required of competent future school counselors. This article suggests practical strategies for SCITs, including engaging in reflection; navigating feelings of vulnerability in supervision; developing appropriate professional dispositions for school counseling practice; and practicing self-advocacy, broaching, and self-care. Counselor educators can share these strategies to help students identify their needs for their field experiences and prepare for their professional careers as school counselors.

Keywords: supervision, professional development, school counseling, school counselors-in-training, strategies

School counselors-in-training (SCITs) are trainees enrolled in graduate-level counselor education programs and receive supervision as an integral component of their training (Bernard & Goodyear, 2019). Although the supervision relationship is often characterized as hierarchical, trainees must actively participate in the supervision process to develop competency as counseling professionals (Stark, 2017). Despite this, trainees in counseling programs generally receive little guidance on understanding their roles in supervision or how to make the most of their supervision experience to contribute to their learning (Pearson, 2004; Stark, 2017). Although Pearson (2004) offered suggestions for mental health counseling students to optimize their supervision experiences, there is limited literature about how school counseling students can maximize their supervision experiences. The intention of this article is to share strategies for SCITs to take the initiative to approach supervisors with questions and ideas about their overall supervision experience, though these suggestions are not limited to SCITs and may also be useful for trainees across other counseling disciplines.

School counseling site supervision is distinguishable from supervision in other helping professions in that the roles and responsibilities of professional school counselors extend beyond the individual and group counseling services that their community counseling partners provide (American School Counselor Association [ASCA], 2019a, 2021; Quintana & Gooden-Alexis, 2020). For example, comprehensive school counseling programming encompasses direct counseling services with students and families in addition to broader systemic consultation, advocacy, and support for school communities (ASCA, 2019a). School counselors encounter unique challenges in schools regarding student and staff mental health, issues related to equity and access, and navigating the political landscapes of school systems (Bemak & Chung, 2008). Even with an understanding of these distinct themes in school counseling, there is a lack of significance placed on supervision in school counseling within research and in practice to adequately respond to contemporary school counseling issues (Bledsoe et al., 2019). Examining how SCITs can approach supervision and their roles as trainees can ensure their own learning and developmental needs are met, along with the needs of their school communities.

Contexts of School Counseling Supervision

Supervision for SCITs is provided by experienced professional school counselors and characterized by an intentional balance of hierarchy, evaluation, and support during their practicum and internship fieldwork experiences (Bernard & Goodyear, 2019; Borders & Brown, 2005). School counselor supervision serves three primary purposes: (a) promoting competency in effective and ethical school counseling practice; (b) facilitating SCITs’ personal and professional development; and (c) upholding accountability of services and programs for the greater profession and the schools, students, and families receiving services (ASCA, 2021; L. J. Bradley et al., 2010). School counseling site supervisors utilize their training and experiences to guide SCITs through their induction to the profession and development of initial skills and dispositions.

ASCA (2021) compels school counseling supervisors to address the complexities specific to educational settings as they support the professional development of SCITs, which sets school counseling supervision apart from supervision in other clinical counseling disciplines. School counselors facilitate instruction and classroom management, provide appraisal and advisement, and support the developmental and social–emotional needs of students through data-informed school counseling programs (ASCA, 2019a). Within school and community settings, they also navigate systems with an advocacy and social justice orientation and attend to cultural competence and anti-racist work. Although there are school counseling–specific supervision models that address some of the complexities inherent in the work of school counselors (e.g., Lambie & Sias, 2009; Luke & Bernard, 2006; S. Murphy & Kaffenberger, 2007; Wood & Rayle, 2006), there is currently a gap in the school counseling literature about effectively addressing the unique supervision needs of SCITs. Therefore, school counselor practitioners and counselor educators may refer to professional standards for supervision to inform how they supervise and support the developmental needs of SCITs, which may also help SCITs to understand what they might expect to encounter in graduate-level supervision.

Professional Standards for School Counseling Supervision

School counseling professional standards underscore the need for school counselor supervisors to seek supervision and training (ASCA, 2019b; Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs [CACREP], 2015; Quintana & Gooden-Alexis, 2020). Professional associations and accrediting organizations (e.g., ASCA, CACREP) promote adherence to and integration of school counselor standards and competencies related to leadership, advocacy, collaboration, systemic change, and ethical practice (ASCA, 2022; CACREP, 2015; Quintana & Gooden-Alexis, 2020). As such, school counseling supervision facilitates ethical and professional skill development through school counselor standards and competencies, such as the ASCA School Counselor Professional Standards & Competencies (ASCA, 2019c) and the ASCA Ethical Standards for School Counselors (ASCA, 2022).

School counseling supervisors can support SCITs’ professional growth and development by aligning supervision activities with specific standards and competencies (Quintana & Gooden-Alexis, 2020). For example, a supervisor seeking to model the school counselor mindset and behavior standards focused on collaborative partnerships (i.e., M 5, B-SS 6; ASCA, 2019c) might provide opportunities for SCITs to develop relationships with stakeholders (e.g., families, administrators, community) while supporting student achievement. Similarly, an example of aligning supervision activities with ethical standards might involve guiding an SCIT through the process of utilizing an ethical decision-making model to resolve a potential dilemma (see Section F; ASCA, 2022).

Supervision in School Counseling

Supervision in school counseling ensures that new professionals enter the field prepared to understand and support the needs of students by effectively applying ethical standards and best practices of the profession. As such, gatekeeping is a crucial component of supervision. As gatekeepers, counselor educators or supervisors exercise their professional authority to take action that prevents a trainee who does not enact the required professional dispositions and ethical practices from entering the profession of counseling (Bernard & Goodyear, 2019). When a trainee is identified as unable to achieve counseling competencies or likely to harm others, ethical practice guides counselor educators to provide developmental or remedial services to work toward improvements before dismissal from a counseling program (American Counseling Association [ACA], 2014; Foster & McAdams, 2009).

Although supervised fieldwork experiences during graduate education and training are needed for accreditation (CACREP, 2015) and state certification, professional school counselors employed in the field may not be required to participate in any form of post-master’s clinical supervision for initial school counseling certification or renewal of their certification, unlike professional clinical mental health counselors, who require post-master’s supervision to attain licensure (Dollarhide & Saginak, 2017; Mecadon-Mann & Tuttle, 2023). Administrative supervision provided by a school administrator is more common for school counselors than clinical supervision, which promotes the competence of counselors by focusing on the development and refinement of counseling skills (Herlihy et al., 2002). In other words, though school counselors routinely encounter complex situations that involve supporting students with acute needs and responding to crises, they likely do not receive the clinical supervision needed to enhance their judgment, skills, and ethical decision-making (Bledsoe et al., 2019; Brott et al., 2021; Herlihy et al., 2002; McKibben et al., 2022; Sutton & Page, 1994). Given the reality that school counselors may not access or receive opportunities for postgraduate clinical supervision, it is important that SCITs experience robust supervision during their graduate training programs with the support of qualified site and university supervisors. This sets the stage for SCITs to effectively engage with the challenges of their future school counseling careers.

Expectations of Site and University Supervisors

For SCITs who are new to the experience of supervision in their fieldwork, it is helpful to understand what they may expect from their respective site and university supervisors. Borders et al. (2014) recommended that supervisors initiate supervision, set goals with trainees, provide feedback, facilitate the supervisory relationship, and attend to diversity, as well as engage in advocacy, ethical consideration, documentation, and evaluation. Supervisors select supervision interventions that attend to the developmental needs of trainees, and they also serve as gatekeepers for the profession (Bernard & Goodyear, 2019; Borders et al., 2014). Furthermore, supervisors facilitate an effective relationship with their trainees, characterized by empowerment, encouragement, and safety (Dressel et al., 2007; Ladany et al., 2013; M. J. Murphy & Wright, 2005). Supervisors provide a balance of support and challenge in their feedback and interactions with trainees (Bernard & Goodyear, 2019) and attend to multicultural issues by broaching with their trainees about their intersecting identities and experiences of power, privilege, and marginalization (Dressel et al., 2007; Jones et al., 2019; M. J. Murphy & Wright, 2005). Supervisors also validate trainees’ experiences by acknowledging any emergent issues of vicarious trauma and encouraging self-care (K. Jordan, 2018).

Supervisors and trainees have mutual responsibilities to facilitate an effective supervision experience. Although supervisors may hold a more significant stake of power in the relationship, trainees’ willingness to take an active role also matters. School counseling trainees are not passive bystanders in the learning process; instead, they can be thoughtful learners yearning to take full advantage of the growth from their clinical experiences. To help illuminate the opportunities and expectations SCITs can seek during supervision, the subsequent strategies from school counseling supervision research serve as suggested approaches for SCITs to make the most of this fundamental and practical learning experience.

Strategies for School Counseling Trainees

School counseling trainees can take an active role to ensure that their supervision experiences are relevant to their personal and professional development. The following approaches do not constitute an all-encompassing list but provide a foundation and guidelines rooted in existing research to get the most out of the supervision experience, including engaging in reflection and vulnerability, practicing self-advocacy, broaching, and maintaining personal wellness.

Reflection in Supervision

Reflection is key to school counselor development, especially in supervision. Researchers have reported that continuous reflection helps novice counselors move toward higher levels of cognitive complexity and expertise (Borders & Brown, 2005; Skovholt & Rønnestad, 1992). A reflective trainee demonstrates openness to understanding; avoids being defensive; and engages in profound thought processes that lead to changes in their perceptions, practice, and complexity (Neufeldt et al., 1996). Through reflection, trainees consider troubling, confusing, or uncertain experiences or thoughts and then reframe them to problem-solve and guide future actions (Ward & House, 1998; Young et al., 2011). Further, by developing relationships with supervisors, trainees become open to receiving and integrating feedback to support their development (Borders & Brown, 2005). Reflection becomes an ongoing process and practice throughout trainees’ academic and field experiences and postgraduation.

Trainees can engage in self-reflective practices in various ways over the course of their graduate training. First, trainees can use a journal to record thoughts, feelings, and events throughout their school counseling field experiences. Research has shown that written or video journaling can help trainees to reflect on the highs and lows of counseling training and foster self-awareness (Parikh et al., 2012; Storlie et al., 2018; Woodbridge & O’Beirne, 2017). For example, trainees can connect their practical experiences with knowledge from academic learning to note discrepancies and consistencies (e.g., learning about the ASCA National Model and the extent to which a school chooses to implement the model; navigating the bureaucracy of school systems that often dictate roles and responsibilities of school counselors). Trainees can also challenge their thoughts by exploring difficult experiences using reflective journaling. They can journal about the different perspectives of those involved in the situation (e.g., students, parents/guardians, teachers, administrators), process ethical dilemmas, and gauge and manage any emotional experiences attached to grappling with challenges. Trainees desiring structured prompts can consider writing about specific developmental, emotional, and interpersonal experiences to process events related to counselor and client interactions (Storlie et al., 2018).

Second, trainees can consult with their supervisors to seek guidance and constructive feedback about challenging experiences (Borders & Brown, 2005). Hamlet (2022) recommended using the S.K.A.T.E.S. form to reflect on issues related to trainees’ Skills, Knowledge, Attitudes, Thoughts, Ethics, and Supervision needs. Using S.K.A.T.E.S., for example, a school counseling intern may reflect on how they incorporated motivational interviewing counseling skills to support a student struggling with their declining grades (North, 2017). They might seek supervision about a challenging crisis response at the school and process how they might have responded differently. Even after supervision sessions, trainees should engage in continued self-reflection and apply new learning to their clinical practice.

Third, trainees can utilize the Johari window as a tool to reflect upon the knowledge, awareness, and skills required for school counseling practice (Halpern, 2009). Trainees work with supervisors to consider questions or experiences to identify: (a) open areas (i.e., things known to everyone, such as critically discussing school- and district-wide policies that contribute to inequitable access to college preparatory courses); (b) hidden areas (i.e., things only known to the trainee to be shared in supervision, such as the trainee’s hesitations about leading a group counseling session with middle school students independently for the first time); (c) blind spots (i.e., things that the supervisor is aware of that the trainee may not be, such as personal biases, prejudices, stereotypes, and discriminatory attitudes that may affect the trainee’s conceptualizations and interactions with students and families); and (d) undiscovered potential (i.e., things that the supervisor and trainee can experience and learn together, such as engaging in professional learning together to align school counseling programming with a school-wide movement toward implementing restorative justice practices). This strategy also compels trainees to align their supervision goals with ethical codes (see A.4.b., F.8.c., and F.8.d in the ACA Code of Ethics) and standards for professional practice (ACA, 2014). Trainees can feel empowered to utilize the Johari window with supervisors and peers to guide conversations, generate questions, and develop insights to inform school counseling practice and explore ethical dilemmas.

Vulnerability in Supervision

Vulnerability is an essential yet challenging experience within the hierarchical nature of supervision. Being vulnerable involves feelings of uncertainty, reluctance, and exposure; hence, trainees require a sense of psychological safety and support to explore their needs and areas of weakness (Bradley et al., 2019; Giordano et al., 2018; J. V. Jordan, 2003). Although site supervisors hold the primary responsibility for facilitating supervision relationships characterized by safety and support (Bernard & Goodyear, 2019), trainees can feel empowered to advocate for supervision environments that encourage authenticity and vulnerability, which are conducive to growth and development.

First, trainees can discuss with their supervisors and peers to define feelings of vulnerability and create group norms to promote supported vulnerability (Bradley et al., 2019). With a shared understanding, trainees, supervisors, and peers create an environment for continued growth and risk-taking. For example, during the first group supervision meeting, trainees can suggest norms that will individually and collectively sustain a safe classroom community for sharing and learning. A lack of clear norms about how to communicate feedback may result in experiences of shame and affect trainees’ confidence (J. V. Jordan, 2003; Ratts & Greenleaf, 2018). To mitigate this, trainees, supervisors, and peers can collaboratively discuss appropriate and preferred ways of giving and receiving feedback that is supportive, productive, and meaningful (Ladany et al., 2013). For example, trainees may prefer specific comments rather than general praise: “When the client expressed their frustration, you did well to remain calm and reflect content and feelings in that moment,” instead of “You did a great job.” This exchange among trainees, supervisors, and peers offers a constructive and engaging experience in which individuals can appropriately support and challenge one another.