Aug 18, 2020 | Volume 10 - Issue 3

Jacob Olsen, Sejal Parikh Foxx, Claudia Flowers

Researchers analyzed data from a national sample of American School Counselor Association (ASCA) members practicing in elementary, middle, secondary, or K–12 school settings (N = 4,066) to test the underlying structure of the School Counselor Knowledge and Skills Survey for Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (SCKSS). Using both exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, results suggested that a second-order four-factor model had the best fit for the data. The SCKSS provides counselor educators, state and district leaders, and practicing school counselors with a psychometrically sound measure of school counselors’ knowledge and skills related to MTSS, which is aligned with the ASCA National Model and best practices related to MTSS. The SCKSS can be used to assess pre-service and in-service school counselors’ knowledge and skills for MTSS, identify strengths and areas in need of improvement, and support targeted school counselor training and professional development focused on school counseling program and MTSS alignment.

Keywords: school counselor knowledge and skills, survey, multi-tiered systems of support, factor analysis, school counseling

The role of the school counselor has evolved significantly since the days of “vocational guidance” in the early 1900s (Gysbers, 2010, p. 1). School counselors are now called to base their programs on the American School Counselor Association (ASCA) National Model for school counseling programs (ASCA, 2019a). The ASCA National Model consists of four components: Define (i.e., professional and student standards), Manage (i.e., program focus and planning), Deliver (i.e., direct and indirect services), and Assess (i.e., program assessment and school counselor assessment and appraisal; ASCA, 2019a). Within the ASCA National Model framework, school counselors lead and contribute to schoolwide efforts aimed at supporting the academic, career, and social/emotional development and success of all students (ASCA, 2019b). In addition, school counselors are uniquely trained to provide small-group counseling and psychoeducational groups, and to collect and analyze data to show the impact of these services (ASCA, 2014; Gruman & Hoelzen, 2011; Martens & Andreen, 2013; Olsen, 2019; Rose & Steen, 2015; Sink et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2015). School counselors also support students with the most intensive needs by providing referrals to community resources, collaborating with intervention teams, and consulting with key stakeholders involved in student support plans (Grothaus, 2013; Pearce, 2009; Ziomek-Daigle et al., 2019).

This model for meeting the needs of all students aligns with a multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS) framework, one of the most widely implemented and researched approaches to “providing high-quality instruction and interventions matched to student need across domains and monitoring progress frequently to make decisions about changes in instruction or goals” (McIntosh & Goodman, 2016, p. 6). In an MTSS framework, there are typically three progressive tiers with increasing intensity of supports based on student responses to core instruction and interventions (J. Freeman et al., 2017). Schoolwide universal systems (i.e., Tier 1), including high-quality research-based instruction, are put in place to support all students academically, socially, and behaviorally; targeted interventions (i.e., Tier 2) are put in place for students not responding positively to schoolwide universal supports; and intensive team-based systems (i.e., Tier 3) are put in place for individual students needing function-based intensive interventions beyond what is received at Tier 1 and Tier 2 (Sugai et al., 2000).

Strategies for aligning school counseling programs and MTSS have been thoroughly documented in the literature (Belser et al., 2016; Goodman-Scott et al., 2015; Goodman-Scott & Grothaus, 2017a; Ockerman et al., 2012). There is also a growing body of research documenting the impact of this alignment on important student outcomes (Betters-Bubon & Donohue, 2016; Campbell et al., 2013; Goodman-Scott et al., 2014) and the role of school counselors (Betters-Bubon et al., 2016; Goodman-Scott, 2013). In addition, ASCA recognizes the significance of school counselors’ roles in MTSS implementation, highlighting that “school counselors are stakeholders in the development and implementation of a Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS)” and “align their work with MTSS through the implementation of a comprehensive school counseling program” (ASCA, 2018, p. 47).

The benefits of school counseling program and MTSS alignment are clear; however, effective alignment depends on school counselors having knowledge and skills for MTSS (Sink & Ockerman, 2016). Despite consensus in the literature about the knowledge and skills for MTSS that school counselors need to align their programs, there is a lack of psychometrically sound surveys that measure school counselors’ knowledge and skills for MTSS. Therefore, the validation of such a survey is a critical component to advancing the process of school counselors developing the knowledge and skills needed to contribute to MTSS implementation and align their programs with existing MTSS frameworks.

Knowledge and Skills for MTSS

The core features of MTSS include (a) universal screening, (b) data-based decision-making, (c) a continuum of evidence-based practices, (d) a focus on fidelity of implementation, and (e) staff training on evidence-based practices (Berkeley et al., 2009; Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, 2015; Chard et al., 2008; Hughes & Dexter, 2011; Michigan’s Integrated Behavior & Learning Support Initiative, 2015; Sugai & Simonsen, 2012). For effective MTSS implementation, school staff need the knowledge and skills to plan for and assess the systems and practices embedded in each of the core features (Eagle et al., 2015; Leko et al., 2015). Despite this need, researchers have found that school staff, including school counselors, often lack knowledge and skills of key components for MTSS (Bambara et al., 2009; Patrikakou et al., 2016; Prasse et al., 2012). For example, Patrikakou et al. (2016) conducted a national survey and found that school counselors understood the MTSS framework and felt prepared to deliver Tier 1 counseling supports. However, school counselors felt least prepared to use data management systems for decision-making and assessing the impact of MTSS interventions (Patrikakou et al., 2016).

As a result of the gap in knowledge and skills for MTSS, the need to more effectively prepare pre-service educators to implement MTSS has become an increasingly urgent issue across many disciplines within education (Briere et al., 2015; Harvey et al., 2015; Kuo, 2014; Leko et al., 2015; Prasse et al., 2012; Sullivan et al., 2011). This urgency is the result of the widespread use of MTSS and the measurable impact MTSS has on student behavior (Barrett et al., 2008; Bradshaw et al., 2010), academic engagement (Benner et al., 2013; Lassen et al., 2006), attendance (J. Freeman et al., 2016; Pas & Bradshaw, 2012), school safety (Horner et al., 2009), and school climate (Bradshaw et al., 2009). This urgency has been especially emphasized in recent calls for MTSS knowledge and skills to be included in school counselor preparation programs (Goodman-Scott & Grothaus, 2017b; Olsen, Parikh-Foxx, et al., 2016; Sink, 2016).

Given that many pre-service preparation programs have only recently begun integrating MTSS into their training, the opportunity for school staff to gain the knowledge and skills for MTSS continues to be through in-service professional development opportunities at the state, district, or school level (Brendle, 2015; R. Freeman et al., 2015; Hollenbeck & Patrikakou, 2014; Swindlehurst et al., 2015). For in-service school counselors, research shows that MTSS-focused professional development is related to increased knowledge and skills for MTSS (Olsen, Parikh-Foxx, et al., 2016). Further, when school counselors participate in professional development focused on MTSS, the knowledge and skills gained contribute to increased participation in MTSS leadership roles (Betters-Bubon & Donohue, 2016), increased data-based decision-making (Harrington et al., 2016), and decreases in student problem behaviors (Cressey et al., 2014; Curtis et al., 2010).

The knowledge and skills required to implement MTSS effectively have been established in the literature (Bambara et al., 2009; Bastable et al., 2020; Handler et al., 2007; Harlacher & Siler, 2011; Prasse et al., 2012; Scheuermann et al., 2013). In addition, it is evident that school counselors and school counselor educators have begun to address the need to increase knowledge and skills for MTSS so school counselors can better align their programs with MTSS and ultimately provide multiple tiers of support for all students (Belser et al., 2016; Ockerman et al., 2015; Patrikakou et al., 2016). Despite this encouraging movement in the profession, little attention has been given to the measurement of school counselors’ knowledge and skills for MTSS. Thus, the development of a survey that yields valid and reliable inferences about pre-service and in-service efforts to increase school counselors’ knowledge and skills for MTSS will be critical to assessing the development of knowledge and skills over time (e.g., before, during, and after MTSS-focused professional development).

Measuring Knowledge and Skills for MTSS

A critical aspect of effective MTSS implementation is evaluation (Algozzine et al., 2010; Elfner-Childs et al., 2010). Along with student outcome data, MTSS evaluation typically includes measuring the extent to which school staff use knowledge and skills to apply core components of MTSS (i.e., fidelity of implementation), and there are multiple measurement tools that have been developed and validated to aid external evaluators and school teams in this process (Algozzine et al., 2019; Kittelman et al., 2018; McIntosh & Lane, 2019). Despite agreement that school staff need knowledge and skills for MTSS to effectively apply core components (Eagle et al., 2015; Leko et al., 2015; McIntosh et al., 2013), little attention has been given to measuring individual school staff members’ knowledge and skills for MTSS, particularly those of school counselors. Therefore, efficient and reliable ways to measure inferences about school counselor knowledge and skills for MTSS are needed to provide a baseline of understanding and determine gaps that need to be addressed in pre-service and in-service training (Olsen, Parikh-Foxx, et al., 2016; Patrikakou et al., 2016). In addition, the validation of an instrument that measures school counselors’ knowledge and skills for MTSS is timely given that school counselors have been identified as potential key leaders in MTSS implementation given their unique skill set (Ryan et al., 2011; Ziomek-Daigle et al., 2016).

The purpose of this study was to examine the latent structure of the School Counselor Knowledge and Skills Survey for Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (SCKSS). Using confirmatory factor analysis, the number of underlying factors of the survey and the pattern of item–factor relationships were examined to address the research question: What is the factor structure of the SCKSS? Results of this study provide information on possible uses and scoring procedures of the SCKSS for examining MTSS knowledge and skills.

Method

Participants

The potential participants in this study were a sample of the 15,106 ASCA members who were practicing in K–12 settings at the time of this study. In all, 4,598 school counselors responded to the survey (30% response rate). In addition, 532 only responded to a few survey items (i.e., one or two) and were therefore excluded from the analyses. The final sample size for the analyses was 4,066. The sample used for this study mirrors school counselor demographics nationwide (ASCA, 2020; Bruce & Bridgeland, 2012). Overall, 87% of participants identified as female, 84% as Caucasian, and 74% as being between the ages of 31 and 60. Most of the school counselors in the sample reported being certified for 1–8 years (59%), working in schools with 500–1,000 students (40%) in various regions across the nation, and having student caseloads ranging from 251–500 students (54%). In addition, 25%–50% of their students were eligible for free and reduced lunch, and 54% reported that their students were racially or ethnically diverse. Lastly, most participants worked in suburban (45%) high school (37%) settings.

Sampling Procedures

Prior to conducting the research, a pilot study was conducted to assess 1) the clarity and conciseness of the directions and items on the demographic questionnaire and SCKSS, and 2) the amount of time it takes to complete the demographic questionnaire and survey (Andrews et al., 2003; Dillman et al., 2014). Four school counselors completed the demographic questionnaire and survey. Following completion, the school counselors were asked to provide feedback on the clarity and conciseness of the directions and items on the demographic questionnaire and survey as well as how much time it took to complete both measures. All pilot study participants reported that the directions were clear and easy to follow. Based on the feedback from the pilot study, the demographic questionnaire and survey were expected to take participants approximately 10–15 minutes to complete.

After obtaining approval from the IRB, SurveyShare was used to distribute an introductory email and survey link to ASCA members practicing in K–12 settings. After following the link, potential participants were given an informed consent form on the SurveyShare website. Participants who completed the survey were given the opportunity to participate in a random drawing using disassociated email addresses to increase participation (Dillman et al., 2014). Following informed consent, participants were directed to the demographic questionnaire and SCKSS. A follow-up email was sent to potential participants who did not complete the survey 7 days after the original email was sent. After 3 weeks, the link was closed.

Survey and Data Analyses

School Counselor Knowledge and Skills Survey for Multi-Tiered Systems of Support

The SCKSS was developed based on the work of Blum and Cheney (2009; 2012). The Teacher Knowledge and Skills Survey for Positive Behavior Support (TKSS) has 33 self-report items using a 5-point Likert scale to measure teachers’ knowledge and skills for Positive Behavior Supports (PBS; Blum & Cheney, 2012). Items incorporate evidence-based knowledge and skills consistent with PBS. Conceptually, items of the TKSS were developed based on five factors: (a) Specialized Behavior Supports and Practices, (b) Targeted Intervention Supports and Practices, (c) Schoolwide Positive Behavior Support Practices, (d) Individualized Curriculum Supports and Practices, and (e) Positive Classroom Supports and Practices. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) conducted by Blum and Cheney (2009) indicated reliability coefficients for the five factors as follows: 0.86 for Specialized Behavior Supports and Practices, 0.87 for Targeted Intervention Supports and Practices, 0.86 for Schoolwide Positive Behavior Support Practices, 0.84 for Individualized Curriculum Supports and Practices, and 0.82 for Positive Classroom Supports and Practices.

Table 1

Items, Means, and Standard Deviation for the SCKSS

| Rate the following regarding your knowledge on the item: |

M |

SD |

| 1. I know our school’s policies and programs regarding the prevention of behavior problems. |

3.66 |

0.95 |

| 2. I understand the role and function of our schoolwide behavior team. |

3.58 |

1.12 |

| 3. I know our annual goals and objectives for the schoolwide behavior program. |

3.33 |

1.19 |

| 4. I know our school’s system for screening with students with behavior problems. |

3.35 |

1.20 |

| 5. I know how to access and use our school’s pre-referral teacher assistance team. |

3.23 |

1.43 |

| 6. I know how to provide access and implement our school’s counseling programs. |

4.20 |

0.84 |

| 7. I know the influence of cultural/ethnic variables on student’s school behavior. |

3.83 |

0.87 |

8. I know the programs our school uses to help students with their social and emotional development

(schoolwide expectations, conflict resolution, etc.). |

3.92 |

0.95 |

| 9. I know a range of community services to assist students with emotional/behavioral problems. |

3.72 |

0.93 |

10. I know our school’s discipline process—the criteria for referring students to the office, the methods

used to address the problem behavior, and how and when students are returned to the classroom. |

3.72 |

1.03 |

11. I know what functional behavioral assessments are and how they are used to develop behavior

intervention plans for students. |

3.35 |

1.12 |

12. I know how our schoolwide behavior team collects and uses data to evaluate our schoolwide

behavior program. |

3.12 |

1.29 |

13. I know how to provide accommodations and modifications for students with emotional and

behavioral disabilities (EBD) to support their successful participation in the general education setting. |

3.34 |

1.09 |

| 14. I know our school’s crisis intervention plan for emergency situations. |

3.74 |

1.06 |

| Rate how effectively you use the following skills/strategies: |

|

|

| 15. Approaches for helping students to solve social/interpersonal problems. |

4.04 |

0.71 |

| 16. Methods for teaching the schoolwide behavioral expectations/social skills. |

3.62 |

0.96 |

| 17. Methods for encouraging and reinforcing the use of expectations/social skills. |

3.80 |

0.84 |

| 18. Strategies for improving family–school partnerships. |

3.35 |

0.92 |

| 19. Collaborating with the school’s student assistance team to implement student’s behavior intervention plans. |

3.50 |

1.11 |

| 20. Collaborating with the school’s IEP team to implement student’s individualized education programs. |

3.53 |

1.09 |

| 21. Evaluating the effectiveness of student’s intervention plans and programs. |

3.38 |

1.01 |

| 22. Modifying curriculum to meet individual performance levels. |

3.10 |

1.09 |

| 23. Selecting and using materials that respond to cultural, gender, or developmental differences. |

3.26 |

1.02 |

| 24. Establishing and maintaining a positive and consistent classroom environment. |

3.71 |

0.98 |

| 25. Identifying the function of student’s behavior problems. |

3.52 |

0.92 |

| 26. Using data in my decision-making process for student’s behavioral programs. |

3.39 |

1.01 |

| 27. Using prompts and cues to remind students of behavioral expectations. |

3.67 |

0.95 |

| 28. Using self-monitoring approaches to help students demonstrate behavioral expectations. |

3.48 |

0.96 |

| 29. Communicating regularly with parents/guardians about student’s behavioral progress. |

3.64 |

0.97 |

30. Using alternative settings or methods to resolve student’s social/emotional problems (problem-

solving, think time, or buddy room, etc. not a timeout room). |

3.45 |

1.06 |

| 31. Methods for diffusing or deescalating student’s social/emotional problems. |

3.76 |

0.87 |

| 32. Methods for enhancing interpersonal relationships of students (e.g., circle of friends, buddy system, peer mentors). |

3.62 |

0.92 |

| 33. Linking family members to needed services and resources in the school. |

3.72 |

0.91 |

The TKSS was adapted in collaboration with the authors to develop the SCKSS (Olsen, Blum, et al., 2016) to specifically target school counselors and to reflect the updated terminology recommended in the literature (Sugai & Horner, 2009). To update terminology, multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS) replaced Positive Behavior Supports (PBS) throughout the survey. In addition, school counselor replaced teacher to reflect the role of intended participants. Finally, item 6 was updated from “I know how to access and use our school’s counseling programs” to “I know how to provide access and implement our school’s counseling programs” because of school counselors’ roles and interactions with their own programs. Further, item 6 was adjusted to be an internally oriented question about the delivery of the school counseling program rather than the school counselor’s knowledge of another school service or system in order to assess participants’ perceived mastery of school counseling program implementation rather than their perception of another service not already measured in the SCKSS. A description of the 33 SCKSS items and the means and standard deviations of each item for the current study are located in Table 1.

Data Analyses

A cross-validation holdout method was used to examine the data–model fit of the SCKSS. Prior to statistical analyses, data were screened for missing data, multivariate outliers, and the assumptions for multivariate regression. Less than 5% of the data for any variable was missing and Little’s MCAR test (χ2 = 108.47, df = 101, p = .29) indicated missing values could be considered as missing completely at random. Multiple imputation was used to estimate missing values. Although there were some outliers, results of a sensitivity analysis indicated that none of the outliers were overly influential. The assumptions of linearity, normality, multicollinearity, and homoscedasticity suggested that all the assumptions were tenable. The original sample (N = 4,066) was randomly divided into two sub-samples (N = 2,033). The first subset was used to conduct exploratory analyses and develop a model that fit the data. The second subset of participants was used to conduct confirmatory analyses without modifications.

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA). Using the first subset from the sample, an EFA was conducted, using SPSS, to explore the number of factors and the alignment of items to factors. The number of factors extracted was estimated based on eigenvalues greater than 1.0 and a visual inspection of the scree plot. Several rotation methods were used, including varimax and direct oblimin with changing the delta value (from 0 to 0.2). The goal of the EFA was to find a factor solution that was theoretically sound.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). The estimation method employed for the CFA was maximum likelihood robust estimation, which is a more accurate estimate for non-normal data (Savalei, 2010). Although the data were ordinal (i.e., Likert-type scale), Mplus uses a different maximum likelihood fitting function for categorical variables. The Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square difference test was used to determine the best model. The pattern coefficient for the first indicator of each latent variable was fixed to 1.00. Indices of model–data fit considered were chi-square test, root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR), comparative fit index (CFI), and Akaike information criterion (AIC). Browne and Cudeck (1993) suggested that values greater than .10 might indicate a lack of fit. In this study, an upper 90% confidence interval value lower than .08 was used to suggest an acceptable fit. CFI values greater than .90, which indicate that the proposed model is greater than 90% of the baseline model, served as an indicator of adequate fit (Kline, 2016). Perfect model fit is indicated by SRMR = 0, and values greater than .10 may indicate poor fit (Kline, 2016). Reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha (α). CFAs were used in both the exploratory and confirmatory phases of this study. In the exploratory phase (i.e., using the first subset from the sample), the researchers used the residual estimates and modification indices to identify local misfit. Respecification of correlated error variances was expected because of the data collection method (i.e., counselors responding to a single

survey) and similar wording of the items.

Results

Exploratory Phase

Exploratory Factor Analysis

An EFA was used to evaluate the structure of the 33 items on the SCKSS. Principal axis factoring was used as the extraction method. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test value was .97, which suggests the sample was acceptable for conducting an EFA. The decrease in eigenvalues leveled off at five factors, with four factors having eigenvalues greater than 1.0. Parallel analysis confirmed that four factors should be retained in the solution. An oblique rotation, which was selected to allow correlation among the factors, was performed and used to determine the number of factors and item pattern.

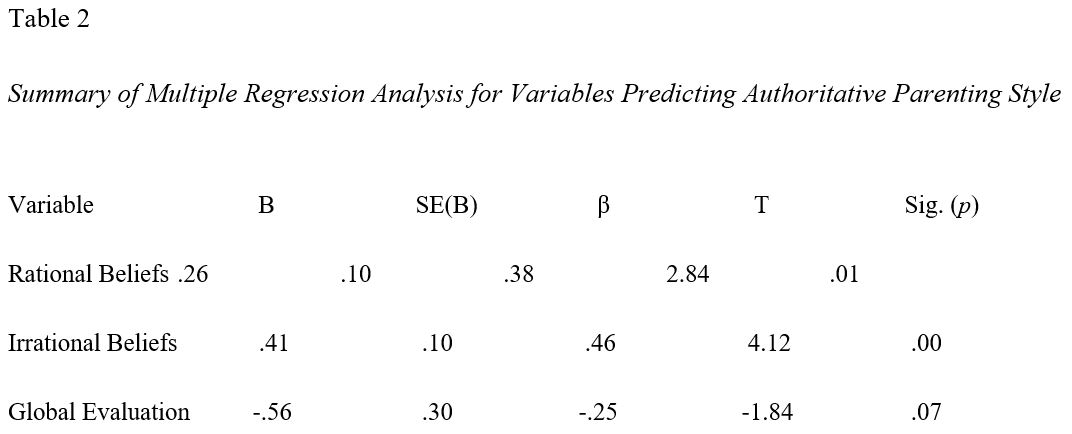

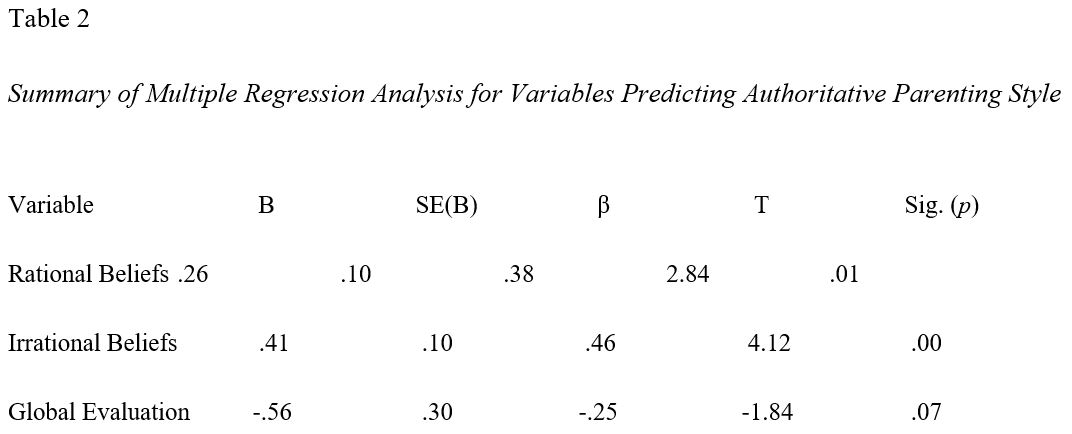

The total variance accounted for by four factors was 64%. The item communalities were all above 0.5. Item pattern (i.e., > 0.4) and structure (i.e., > 0.5) coefficients were examined to determine the relationship of the items to the factors. Twenty-nine items clearly aligned to one factor and three items loaded in multiple factors. In a review of the item patterns, it was determined by the researchers that the three items theoretically fit in specific factors. The fourth factor only aligned with three items. In an expert review, it was determined that the three items differentiated enough from the other factors to warrant a separate factor. The alignment of items and factors are reported in Table 2.

Table 2

Alignment of Items and Factors based on EFA

| Factor |

Items |

| Individualized Supports and Practices |

11, 13, 16, 17, 22, 23, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 |

| Schoolwide Supports and Practices |

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 10, 12, 14, 24 |

| Targeted Supports and Practices |

6, 7, 9, 15, 18, 33 |

| Collaborative Supports and Practices |

19, 20, 21 |

The first factor was named Individualized Supports and Practices. This factor contained 14 items focused on school counselors’ knowledge and skills for supporting students individually based on need. Examples of items on the Individualized Supports and Practices factor included: “Selecting and using materials that respond to cultural, gender, or developmental differences” and “Methods for diffusing or deescalating student’s social/emotional problems.” The second factor was Schoolwide Supports and Practices, with 10 items focused on school counselors’ knowledge and skills of schoolwide and team-based efforts aimed at supporting all students and preventing student problem behavior and academic decline. Examples of items on the Schoolwide Supports and Practices factor included: “I know our annual goals and objectives for the schoolwide behavior program” and “I know our school’s crisis intervention plan for emergency situations.” Factor 3 was named Targeted Supports and Practices and contained six items. These items focused on school counselors’ knowledge and skills related to providing targeted supports for small groups of students not responding positively to schoolwide prevention efforts. Examples of items on the Targeted Supports and Practices factor included: “I know the influence of cultural/ethnic variables on student’s school behavior” and “Strategies for improving family–partnerships.” The fourth and final factor was Collaborative Supports and Practices, which contained three items focused on school counselors’ knowledge and skills related to collaborating with school personnel to implement student interventions. An example item of the Collaborative Supports and Practices factor was: “Collaborating with the school’s IEP team to implement student’s individualized education programs.” This four-factor model served as our preferred model, but competing models were explored using CFA on the first subset from the sample.

CFA Using First Subset Sample

The competing models were examined to determine the best data–model fit by conducting a CFA using MPlus. The following models were tested: (a) one-factor model, (b) four-factor model, and

(c) second-order four-factor model. Model modifications were allowed during the exploratory phases. The results of the CFA are reported in Table 3.

Table 3

Results of the Confirmatory Factor Analyses for the Exploratory Phase

|

Competing Models |

Chi-square |

df |

SRMR |

RMSEA |

90% CI, RMSEA |

TLI |

CFI |

AIC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Exploratory Analyses |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

One-Factor (initial) |

8,518.75 |

495 |

.057 |

.084 |

[.083, .086] |

0.79 |

.80 |

168,279.20 |

|

One-Factor (modification) a |

4,465.60 |

478 |

.048 |

.060 |

[.059, .062] |

0.89 |

.90 |

162,654.94 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2 |

Four-Factor (initial) |

5,619.01 |

489 |

.058 |

.068 |

[.066, .069] |

0.86 |

.87 |

164,253.62 |

|

Four-Factor (modification) b |

3,866.27 |

481 |

.048 |

.055 |

[.054, .057] |

0.91 |

.92 |

161,407.48 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3 |

Four-Factor second order |

5,632.53 |

491 |

.058 |

.068 |

[.066, .069] |

0.86 |

.87 |

164,270.54 |

|

Four-Factor second order (modified) b |

3,866.27 |

483 |

.048 |

.055 |

[.054, .057] |

0.91 |

.91 |

161,432.63 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Confirmatory Analysis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Four-Factor second order |

5,424.82 |

490 |

0.058 |

0.066 |

[.065, .068] |

0.87 |

.88 |

164,999.81 |

|

Four-Factor second order (modified) b |

4,468.62 |

483 |

0.051 |

0.060 |

[.058, .062] |

0.89 |

.90 |

163,723.53 |

Note. All chi-square tests were statistically significant at < .001.

a Seventeen correlated error variances were estimated. b Eight correlated error variances were estimated.

The initial one-factor model did not fit the data (chi-square = 8,518.75, df = 495, p < .001; RMSEA = .084, 90% CI [.083, .086]; CFI = .80; SRMR = .057), but after modification (i.e., 17 correlated error variances between observed variables), the one-factor model had an adequate fit (chi-square = 4,465.60, df = 478, p < .001; RMSEA = .060, 90% CI [.059, .062]; CFI = .90; SRMR = .048). Reasonable data–model fit was obtained for the modified models in both the four-factor and four-factor second-order models (see Table 3). Modifications included freeing eight correlated error variances between observed variables. A content expert reviewed the suggested modification to determine the appropriateness of allowing the error variances to correlate. In all but one case, the suggested correlated item error variances were adjacent to each other on the survey (i.e., item 2 with 3, 6 with 7, 11 with 12, 17 with 18, 20 with 21, 22 with 23, and 27 with 28). Given the proximity of the items, it was plausible that some systematic error variance between items would correlate. The only pair of items that were not adjacent were item 5 and item 19. Both of these items referred to the school’s teacher assistance team. For all the models, the path coefficients were statistically significant (p < .001).

Results of the Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square difference test suggested that the four-factor model was a better model than the one-factor model (p < .001), and there was no statistically significant difference between the four-factor model and the second-order four-factor model. Because of the high intercorrelations among the factors (ranging from .81 to .92), the second-order four-factor model was tested using the second subset from the sample.

Confirmatory Phase

The holdout sample of 2,033 participants was used to verify the second-order four-factor model. The initial model (see bottom of Table 3) with no modifications suggested the model marginally fit the data (chi-square = 5,424.82, RMSEA = .066, CFI = .88, SRMR = .058). After modifying the model by allowing for the eight correlated error variances, which were the same eight correlated error variances identified in the exploratory stage, as expected there was an improvement in the model fit (chi-square = 4,468.62, RMSEA = .060, CFI = .90, SRMR = .051). The observed item loading coefficients and standard errors are reported in Table 4. All coefficients are statistically significant and all above 0.50, suggesting stable item alignment to the factor being measured. Coefficient alpha values were 0.95 for total score with all items, 0.88 for Factor 1 (Individualized Supports and Practices), 0.86 for Factor 2 (Schoolwide Supports and Practices), 0.78 for Factor 3 (Targeted Supports and Practices), and 0.65 for Factor 4 (Collaborative Supports and Practices). The results provide evidence that the SCKSS has potential to provide inferences about counselors’ knowledge and skills for MTSS.

Discussion and Implications

The SCKSS was based on the TKSS, which measured teachers’ knowledge and skills related to PBS. After adapting the survey to align to MTSS and the role of school counselors, this study aimed to examine the latent structure of the SCKSS for examining MTSS knowledge and skills. Using both exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, results suggest that a second-order four-factor model had the best fit. The findings indicate that the SCKSS has high internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha for the total score at 0.95, and a range between 0.65 and 0.88 for each of the four factors. The first factor, Individualized Supports and Practices, contains 14 items; the second factor, Schoolwide Supports and Practices, contains 10 items; the third factor, Targeted Supports and Practices, contains six items; and the fourth factor, Collaborative Supports and Practices, is composed of three items. These findings confirm that the SCKSS yields valid and reliable inferences about school counselors’ knowledge and skills for MTSS. Previous measures that were specific to school counselors focused on confidence and beliefs in implementing response to intervention (RtI; Ockerman et al., 2015; Patrikakou et al., 2016). Although these studies contribute to the literature by aligning RtI with the ASCA National Model, they did not focus on the specific knowledge and skills related to MTSS.

Table 4

Loading Coefficients and Standard Errors for Best Fitting Model

| Factor 1 |

Individualized Supports and Practices |

Item |

Loading |

SE |

|

|

11 |

.652 |

.014 |

|

|

13 |

.735 |

.011 |

|

|

16 |

.712 |

.013 |

|

|

17 |

.762 |

.011 |

|

|

22 |

.645 |

.014 |

|

|

23 |

.674 |

.013 |

|

|

25 |

.801 |

.009 |

|

|

26 |

.736 |

.012 |

|

|

27 |

.779 |

.010 |

|

|

28 |

.799 |

.009 |

|

|

29 |

.709 |

.012 |

|

|

30 |

.753 |

.012 |

|

|

31 |

.774 |

.010 |

|

|

32 |

.772 |

.010 |

| Factor 2 |

Schoolwide Supports and Practices |

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

.816 |

.009 |

|

|

2 |

.817 |

.010 |

|

|

3 |

.813 |

.010 |

|

|

4 |

.805 |

.010 |

|

|

5 |

.612 |

.016 |

|

|

8 |

.731 |

.012 |

|

|

10 |

.755 |

.011 |

|

|

12 |

.773 |

.011 |

|

|

14 |

.659 |

.014 |

|

|

24 |

.567 |

.017 |

| Factor 3 |

Targeted Supports and Practices |

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

.685 |

.015 |

|

|

7 |

.664 |

.014 |

|

|

9 |

.729 |

.012 |

|

|

15 |

.766 |

.011 |

|

|

18 |

.729 |

.012 |

|

|

33 |

.764 |

.012 |

| Factor 4 |

Collaborative Supports and Practices |

|

|

|

|

|

19 |

.760 |

.013 |

|

|

20 |

.618 |

.017 |

|

|

21 |

.806 |

.012 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Higher order coefficients |

F1 |

.968 |

.006 |

|

|

F2 |

.872 |

.009 |

|

|

F3 |

.911 |

.008 |

|

|

F4 |

.944 |

.010 |

The four factors of the SCKSS can be used to support improvement practices through the use of targeted professional development. This extends previous research that found when school counselors received MTSS-focused training, there was an increase in knowledge and skills (Olsen, Parikh-Foxx, et al., 2016). Accordingly, the four factors of the SCKSS may provide a baseline of school counselors’ knowledge and skills related to MTSS and help determine gaps that need to be addressed in pre-service and in-service training. Through targeted professional development and pre-service training activities, school districts and counselor educators can identify areas in which practitioners need additional training to increase knowledge and skills related to MTSS.

The four factors of the SCKSS align with MTSS tiers and school counselor roles recommended in the ASCA National Model (2019a). The first factor, Individualized Supports and Practices, aligns with the role of school counselors providing individualized indirect services (e.g., data-based decision-making, referrals) for students who need Tier 3 supports (Ziomek-Daigle et al., 2019). The second factor, Schoolwide Supports and Practices, aligns with the role of school counselors providing Tier 1 universal supports (e.g., school counseling lessons, schoolwide initiatives, family workshops) for all students (Sink, 2019). The third factor, Targeted Supports and Practices, aligns with Tier 2 supports provided by school counselors, including small group counseling and psychoeducational group instruction for students who do not successfully respond to schoolwide support services (Olsen, 2019). Finally, the fourth factor, Collaborative Supports and Practices, aligns with the school counselor’s role across multiple tiers of support, providing access to community resources through appropriate referrals and collaborating and consulting with intervention teams (Cholewa & Laundy, 2019).

The SCKSS survey can also be used to improve current school counseling practices. This is an important consideration given Patrikakou et al. (2016) found that although school counselors reported feeling prepared to deliver Tier 1 counseling support services, they felt least prepared to collect and analyze data to determine the effectiveness of interventions. Given that the ASCA National Model (2019a) has a theme entitled Assess, school counselors should be trained to engage in program improvements that move toward positively impacting students. As such, using the SCKSS to improve MTSS practices has the potential to improve ASCA National Model–related activities.

Limitations

There are several limitations in the current study. First, respondents were from a national school counseling association. Their responses could have been influenced by having access to professional development and literature related to MTSS. Second, this was a self-report survey, so the respondents could have answered in a manner that was socially desirable. Third, given the 30% survey return rate, generalizing these results to the population of counselors is not recommended. Fourth, rewording item 6 to an internally oriented question about delivery of the school counseling program rather than school counselors’ knowledge of another school service or system may have impacted the best fit model. Finally, because this was an online survey, only those with access to email and internet at the time of the survey had the opportunity to participate.

Future Research

Although participants in this study included a large national sample of school counselors, they were all members of a national association. Therefore, researchers could replicate this study with school counselors who are non-members and conduct further testing of the psychometric properties of the survey. Second, research could examine how professional development impacts specific aspects of knowledge and skills in relation to student outcomes. That is, if school counselors have targeted professional development around each of the four factors, does that affect student outcomes in areas such as discipline, social/emotional well-being, school climate, or even academic performance? Finally, future studies could explore other variables that impact the development and application of school counselors’ knowledge and skills for MTSS.

Conclusion

There is growing evidence supporting the impact of school counseling program and MTSS alignment (Betters-Bubon et al., 2016; Betters-Bubon & Donohue, 2016; Campbell et al., 2013; Goodman-Scott, 2013; Goodman-Scott et al., 2014). In order for school counselors to align their programs with MTSS and contribute to MTSS implementation, foundational knowledge and skills are essential. Given that research has shown that key factors such as school level (i.e., elementary, middle, high) and MTSS training impact school counselors’ knowledge and skills for MTSS (Olsen, Parikh-Foxx, et al., 2016), the development and validation of an MTSS knowledge and skills survey to measure school counselors’ knowledge and skills over time is an important next step to advancing school counseling program and MTSS alignment. The four factors of the SCKSS (i.e., Individualized Supports and Practices, Schoolwide Supports and Practices, Targeted Supports and Practices, Collaborative Supports and Practices) provide school counselors with an opportunity to reflect on their strengths and areas in need of improvement related to the tiers of the MTSS framework. Further application research and validation of the SCKSS is needed; however, this study indicates the SCKSS provides counselor educators, pre-service school counselors, and in-service school counselors with a tool to measure the development of MTSS knowledge and skills.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Algozzine, B., Barrett, S., Eber, L., George, H., Horner, R., Lewis, T., Putnam, B., Swain-Bradway, J., McIntosh, K., & Sugai, G. (2019). School-wide PBIS Tiered Fidelity Inventory version 2.1. OSEP Technical Assistance Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports. https://www.pbisapps.org/Resources/SWIS%20Publications/SWPBIS%20Tiered%20Fidelity%20Inventory%20(TFI).pdf

Algozzine, B., Horner, R. H., Sugai, G., Barrett, S., Dickey, C. R., Eber, L., Kincaid, D., Lewis, T., & Tobin, T. (2010). Evaluation blueprint for school-wide positive behavior support. National Technical Assistance Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Support. https://www.pbisapps.org/Resources/SWIS%20Publications/Evaluation%20Blueprint%20for%20School-Wide%20Positive%20Behavior%20Support.pdf

American School Counselor Association. (2014). The school counselor and group counseling. ASCA Position Statements, pp. 35–36. https://www.schoolcounselor.org/asca/media/asca/PositionStatements/PositionStatements.pdf

American School Counselor Association. (2018). The school counselor and multitiered system of supports. ASCA Position Statements, pp. 47–48. https://www.schoolcounselor.org/asca/media/asca/PositionStatements/PositionStatements.pdf

American School Counselor Association. (2019a). The ASCA national model: A framework for school counseling programs (4th ed.).

American School Counselor Association. (2019b). Role of the school counselor. https://www.schoolcounselor.org/administrators/role-of-the-school-counselor

American School Counselor Association. (2020). ASCA membership demographics. https://www.schoolcounselor.org/asca/media/asca/home/MemberDemographics.pdf

Andrews, D., Nonnecke, B., & Preece, J. (2003). Electronic survey methodology: A case study in reaching hard-to-involve internet users. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 16(2), 185–210.

https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327590IJHC1602_04

Bambara, L. M., Nonnemacher, S., & Kern, L. (2009). Sustaining school-based individualized positive behavior support: Perceived barriers and enablers. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 11(3), 161–176.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300708330878

Barrett, S. B., Bradshaw, C. P., & Lewis-Palmer, T. (2008). Maryland statewide PBIS initiative: Systems, evaluation, and next steps. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 10(2), 105–114.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300707312541

Bastable, E., Massar, M. M., & McIntosh, K. (2020). A survey of team members’ perceptions of coaching activities related to Tier 1 SWPBIS implementation. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 22(1), 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300719861566

Belser, C. T., Shillingford, M. A., & Joe, J. R. (2016). The ASCA model and a multi-tiered system of supports: A framework to support students of color with problem behavior. The Professional Counselor, 6(3), 251–262. https://doi.org/10.15241/cb.6.3.251

Benner, G. J., Kutash, K., Nelson, J. R., & Fisher, M. B. (2013). Closing the achievement gap of youth with emotional and behavioral disorders through multi-tiered systems of support. Education and Treatment of Children, 36(3), 15–29. https://doi.org/10.1353/etc.2013.0018

Berkeley, S., Bender, W. N., Peaster, L. G., & Saunders, L. (2009). Implementation of response to intervention: A snapshot of progress. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 42(1), 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219408326214

Betters-Bubon, J., Brunner, T., & Kansteiner, A. (2016). Success for all? The role of the school counselor in creating and sustaining culturally responsive positive behavior interventions and supports programs. The Professional Counselor, 6(3), 263–277. https://doi.org/10.15241/jbb.6.3.263

Betters-Bubon, J., & Donohue, P. (2016). Professional capacity building for school counselors through school-wide positive behavior interventions and supports implementation. Journal of School Counseling, 14(3). http://jsc.montana.edu/articles/v14n3.pdf

Blum, C., & Cheney, D. (2009). The validity and reliability of the Teacher Knowledge and Skills Survey for Positive Behavior Support. Teacher Education and Special Education, 32(3), 239–256.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406409340013

Blum, C., & Cheney, D. (2012). Teacher Knowledge and Skills Survey for Positive Behavior Support. Illinois State University.

Bradshaw, C. P., Koth, C. W., Thornton, L. A., & Leaf, P. J. (2009). Altering school climate through school-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports: Findings from a group-randomized effectiveness trial. Prevention Science, 10(2), 100–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-008-0114-9

Bradshaw, C. P., Mitchell, M. M., & Leaf, P. J. (2010). Examining the effects of schoolwide positive behavioral interventions and supports on student outcomes: Results from a randomized controlled effectiveness trial in elementary schools. Journal of Positive Behavioral Interventions, 12(3), 133–148.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300709334798

Brendle, J. (2015). A survey of response to intervention team members’ effective practices in rural elementary schools. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 34(2), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/875687051503400202

Briere, D. E., Simonsen, B., Sugai, G., & Myers, D. (2015). Increasing new teachers’ specific praise using a within-school consultation intervention. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 17(1), 50–60.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300713497098

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen and J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). SAGE.

Bruce, M., & Bridgeland, J. (2012). 2012 national survey of school counselors—True north: Charting the course to college and career readiness.https://secure-media.collegeboard.org/digitalServices/pdf/nosca/true-north.pdf

Campbell, A., Rodriguez, B. J., Anderson, C., & Barnes, A. (2013). Effects of a Tier 2 intervention on classroom disruptive behavior and academic engagement. Journal of Curriculum & Instruction, 7(1), 32–54.

https://doi.org/10.3776/joci.2013.v7n1p32-54

Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports. (2015). Positive behavioral interventions and supports (PBIS) implementation blueprint. University of Oregon. https://www.pbis.org/resource/pbis-implementation-blueprint

Chard, D. J., Harn, B. A., Sugai, G., Horner, R. H., Simmons, D. C., & Kame’enui, E. J. (2008). Core features of multi-tiered systems of reading and behavioral support. In C. G. Greenwood, T. R. Kratochwill, & M. Clements (Eds.), Schoolwide prevention models: Lessons learned in elementary schools (pp. 31–60). Guilford.

Cholewa, B., & Laundy, K. C. (2019). School counselors consulting and collaborating within MTSS. In E. Goodman-Scott, J. Betters-Bubon, & P. Donohue (Eds.), The school counselor’s guide to multi-tiered systems of support (pp. 222–245). Routledge.

Cressey, J. M., Whitcomb, S. A., McGilvray-Rivet, S. J., Morrison, R. J., & Shander-Reynolds, K. J. (2014). Handling PBIS with care: Scaling up to school-wide implementation. Professional School Counseling, 18(1), 90–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X0001800104

Curtis, R., Van Horne, J. W., Robertson, P., & Karvonen, M. (2010). Outcomes of a school-wide positive behavioral support program. Professional School Counseling, 13(3), 159–164.

Dillman, D. A., Smyth, J. D., & Christian, L. M. (2014). Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: The tailored design method. Wiley.

Eagle, J. W., Dowd-Eagle, S. E., Snyder, A., & Holtzman, E. G. (2015). Implementing a multi-tiered system of support (MTSS): Collaboration between school psychologists and administrators to promote systems-level change. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 25(2–3), 160–177.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10474412.2014.929960

Elfner Childs, K., Kincaid, D., & George, H. P. (2010). A model for statewide evaluation of a universal positive behavior support initiative. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 12(4), 198–210.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300709340699

Freeman, R., Miller, D., & Newcomer, L. (2015). Integration of academic and behavioral MTSS at the district level using implementation science. Learning Disabilities: A Contemporary Journal, 13(1), 59–72.

Freeman, J., Simonsen, B., McCoach, D. B., Sugai, G., Lombardi, A., & Horner, R. (2016). Relationship between school-wide positive behavior interventions and supports and academic, attendance, and behavior outcomes in high schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 18(1), 41–51.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300715580992

Freeman, J., Sugai, G., Simonsen, B., & Everett, S. (2017). MTSS coaching: Bridging knowing to doing. Theory Into Practice, 56(1), 29–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2016.1241946

Goodman-Scott, E. (2013). Maximizing school counselors’ efforts by implementing school-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports: A case study from the field. Professional School Counseling, 17(1), 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X0001700106

Goodman-Scott, E., Betters-Bubon, J., & Donohue, P. (2015). Aligning comprehensive school counseling programs and positive behavioral interventions and supports to maximize school counselors’ efforts. Professional School Counseling, 19(1), 57–67. https://doi.org/10.5330/1096-2409-19.1.57

Goodman-Scott, E., Doyle, B., & Brott, P. (2014). An action research project to determine the utility of bully prevention in positive behavior support for elementary school bullying prevention. Professional School Counseling, 17(1), 120–129. https://doi.org/10.5330/prsc.17.1.53346473u5052044

Goodman-Scott, E., & Grothaus, T. (2017a). RAMP and PBIS: “They definitely support one another”: The results of a phenomenological study. Professional School Counseling, 21(1), 119–129.

https://doi.org/10.5330/1096-2409-21.1.119

Goodman-Scott, E., & Grothaus, T. (2017b). School counselors’ roles in RAMP and PBIS: A phenomenological investigation. Professional School Counseling, 21(1), 130–141. https://doi.org/10.5330/1096-2409-21.1.130

Grothaus, T. (2013). School counselors serving students with disruptive behavior disorders. Professional School Counseling, 16(2), 245–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X12016002S04

Gruman, D. H., & Hoelzen, B. (2011). Determining responsiveness to school counseling interventions using behavioral observations. Professional School Counseling, 14(3), 183–190.

Gysbers, N. C. (2010). School counseling principles: Remembering the past, shaping the future: A history of school counseling. American School Counselor Association.

Handler, M. W., Rey, J., Connell, J., Thier, K., Feinberg, A., & Putnam, R. (2007). Practical considerations in creating school-wide positive behavior support in public schools. Psychology in the Schools, 44(1), 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20203

Harlacher, J. E., & Siler, C. E. (2011). Factors related to successful RtI implementation. Communique, 39(6), 20–22.

Harrington, K., Griffith, C., Gray, K., & Greenspan, S. (2016). A grant project to initiate school counselors’ development of a multi-tiered system of supports based on social-emotional data. The Professional Counselor, 6(3), 278–294. https://doi.org/10.15241/kh.6.3.278

Harvey, M. W., Yssel, N., & Jones, R. E. (2015). Response to intervention preparation for preservice teachers: What is the status for Midwest institutions of higher education. Teacher Education and Special Education, 38(2), 105–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406414548598

Hollenbeck, A. F., & Patrikakou, E. (2014). Response to intervention in Illinois: An exploration of school professionals’ attitudes and beliefs. Mid-Western Educational Researcher, 26(2), 58–82.

Horner, R. H., Sugai, G., Smolkowski, K., Eber, L., Nakasato, J., Todd, A. W., & Esperanza, J., (2009). A randomized, wait-list controlled effectiveness trial assessing school-wide positive behavior support in elementary schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 11(3), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300709332067

Hughes, C. A., & Dexter, D. D. (2011). Response to intervention: A research-based summary. Theory Into Practice, 50(1), 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2011.534909

Kittelman, A., Eliason, B. M., Dickey, C. R., & McIntosh, K. (2018). How are schools using the SWPBIS Tiered Fidelity Inventory (TFI)? OSEP Technical Assistance Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports. https://www.pbis.org/resource/how-are-schools-using-the-swpbis-tiered-fidelity-inventory-tfi

Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). Guilford.

Kuo, N.-C. (2014). Why is response to intervention (RTI) so important that we should incorporate it into teacher education programs and how can online learning help? Journal of Online Learning & Teaching, 10(4), 610–624.

Lassen, S. R., Steele, M. M., & Sailor, W. (2006). The relationship of school-wide positive behavior support to academic achievement in an urban middle school. Psychology in the Schools, 43(6), 701–712.

https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20177

Leko, M. M., Brownell, M. T., Sindelar, P. T., & Kiely, M. T. (2015). Envisioning the future of special education personnel preparation in a standards-based era. Exceptional Children, 82(1), 25–43.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402915598782

Martens, K., & Andreen, K. (2013). School counselors’ involvement with a school-wide positive behavior support intervention: Addressing student behavior issues in a proactive and positive manner. Professional School Counseling, 16(5), 313–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X1201600504

McIntosh, K., & Goodman, S. (2016). Integrated multi-tiered systems of support: Blending RTI and PBIS. Guilford.

McIntosh, K., & Lane, K. L. (2019). Advances in measurement in school-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports. Remedial and Special Education, 40(1), 3–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932518800388

McIntosh, K., Mercer, S. H., Hume, A. E., Frank, J. L., Turri, M. G., & Mathews, S. (2013). Factors related to sustained implementation of schoolwide positive behavior support. Exceptional Children, 79(3), 293–311.

Michigan’s Integrated Behavior & Learning Support Initiative. (2015). An abstract regarding multi-tier system of supports (MTSS) and Michigan’s integrated behavior and learning support initiative (MiBLSi). https://mimtsstac.org/sites/default/files/Documents/MIBLSI_Model/MTSS/MiBLSi%20MTSS%20Abstract%20May%202015.pdf

Ockerman, M. S., Mason, E. C. M., & Hollenbeck, A. F. (2012). Integrating RTI with school counseling programs: Being a proactive professional school counselor. Journal of School Counseling, 10(15). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ978870.pdf

Ockerman, M. S., Patrikakou, E., & Hollenbeck, A. F. (2015). Preparation of school counselors and response to intervention: A profession at the crossroads. Journal of Counselor Preparation & Supervision, 7(3), 161–184. https://doi.org/10.7729/73.1106

Olsen, J. (2019). Tier 2: Providing supports for students with elevated needs. In E. Goodman-Scott, J. Betters-Bubon, & P. Donohue (Eds.), The school counselor’s guide to multi-tiered systems of support (pp. 133–162). Routledge.

Olsen, J. A., Blum, C., & Cheney, D. (2016). School counselor knowledge and skills survey for multi-tiered systems of support. Unpublished survey, Department of Counseling, University of North Carolina at Charlotte.

Olsen, J., Parikh-Foxx, S., Flowers, C., & Algozzine, B. (2016). An examination of factors that relate to school counselors’ knowledge and skills in multi-tiered systems of support. Professional School Counseling, 20(1), 159–171. https://doi.org/10.5330/1096-2409-20.1.159

Pas, E. T., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2012). Examining the association between implementation and outcomes: State-wide scale-up of school-wide positive behavior intervention and supports. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 39(4), 417–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-012-9290-2

Patrikakou, E., Ockerman, M. S., & Hollenbeck, A. F. (2016). Needs and contradictions of a changing field: Evidence from a national response to intervention implementation study. The Professional Counselor, 6(3), 233–250. https://doi.org/10.15241/ep.6.3.233

Pearce, L. R. (2009). Helping children with emotional difficulties: A response to intervention investigation. The Rural Educator, 30(2), 34–46.

Prasse, D. P., Breunlin, R. J., Giroux, D., Hunt, J., Morrison, D., & Thier, K. (2012). Embedding multi-tiered

system of supports/response to intervention into teacher preparation. Learning Disabilities: A Contemporary Journal, 10(2), 75–93.

Rose, J., & Steen, S. (2015). The Achieving Success Everyday group counseling model: Fostering resiliency in middle school students. Professional School Counseling, 18(1), 28–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X0001800116

Ryan, T., Kaffenberger, C. J., & Carroll, A. G. (2011). Response to intervention: An opportunity for school

counselor leadership. Professional School Counseling, 14(3), 211–221.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X1101400305

Savalei, V. (2010). Expected versus observed information in SEM with incomplete normal and nonnormal data. Psychological Methods, 15(4), 352–367. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020143

Scheuermann, B. K., Duchaine, E. L., Bruntmyer, D. T., Wang, E. W., Nelson, C. M., & Lopez, A. (2013). An exploratory survey of the perceived value of coaching activities to support PBIS implementation in secure juvenile education settings. Education and Treatment of Children, 36(3), 147–160.

https://doi.org/10.1353/etc.2013.0021

Sink, C. A. (2016). Incorporating a multi-tiered system of supports into school counselor preparation. The Professional Counselor, 6(3), 203–219. https://doi.org/10.15241/cs.6.3.203

Sink, C. (2019). Tier 1: Creating strong universal systems of support and facilitating systemic change. In E. Goodman-Scott, J. Betters-Bubon, & P. Donohue (Eds.), The school counselor’s guide to multi-tiered systems of support (pp. 62–98). Routledge.

Sink, C. A., Edwards, C., & Eppler, C. (2012). School based group counseling. Brooks/Cole.

Sink, C. A., & Ockerman, M. S. (2016). Introduction to the special issue: School counselors and a multi-tiered system of supports: Cultivating systemic change and equitable outcomes. The Professional Counselor, 6(3), v–ix. https://doi.org/csmo.6.3.v

Smith, H. M., Evans-McCleon, T. N., Urbanski, B., & Justice, C. (2015). Check in/check out intervention with peer monitoring for a student with emotional-behavioral difficulties. Journal of Counseling & Development, 93(4), 451–459. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12043

Sugai, G., & Horner, R. H. (2009). Responsiveness-to-intervention and school-wide positive behavior supports: Integration of multi-tiered system approaches. Exceptionality, 17(4), 223–237.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09362830903235375

Sugai, G. M., Horner, R. H., Dunlap, G., Hieneman, M., Lewis, T. J., Nelson, C. M., Scott, T. M., Liaupsin, C.,

Sailor, W., Turnbull, A. P., Turnbull, H. R., Wickham, D., Wilcox, B., & Ruef, M. (2000). Applying positive behavior support and functional behavioral assessment in schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 2(3), 131–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/109830070000200302

Sugai, G., & Simonsen, B. (2012). Positive behavioral interventions and supports: History, defining features, and misconceptions (2012, June 19). University of Connecticut: Center for PBIS & Center for Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports. http://www.pbis.org/common/cms/files/pbisresources/PBIS_revisited_June19r_2012

.pdf

Sullivan, A. L., Long, L., & Kucera, M. (2011). A survey of school psychologists’ preparation, participation, and perceptions related to positive behavior interventions and supports. Psychology in the Schools, 48(10), 971–985. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20605

Swindlehurst, K., Shepherd, K., Salembier, G., & Hurley, S. (2015). Implementing response to intervention: Results of a survey of school principals. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 34(2), 9–16.

https://doi.org/10.1177/875687051503400203

Ziomek-Daigle, J., Cavin, J., Diaz, J., Henderson, B., & Huguelet, A. (2019). Tier 3: Specialized services for students with intensive needs. In E. Goodman-Scott, J. Betters-Bubon, & P. Donohue (Eds.), The school counselor’s guide to multi-tiered systems of support (pp. 163–188). Routledge.

Ziomek-Daigle, J., Goodman-Scott, E., Cavin, J., & Donohue, P. (2016). Integrating a multi-tiered system of support with comprehensive school counseling programs. The Professional Counselor, 6(3), 220–232. https://doi.org/10.15241/jzd.6.3.220

Jacob Olsen, PhD, is an assistant professor at California State University Long Beach. Sejal Parikh Foxx, PhD, is a professor and Chair of the Department of Counseling at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. Claudia Flowers, PhD, is a professor at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. Correspondence may be addressed to Jacob Olsen, College of Education, 1250 Bellflower Boulevard, Long Beach, CA 90840-2201, jacob.olsen@csulb.edu.

Apr 29, 2020 | Volume 10 - Issue 2

Hannah Brinser, Addy Wissel

Students in foster care frequently experience barriers that influence their personal, social, and academic success. These challenges may include trauma, abuse, neglect, and loss—all of which influence a student’s ability to be successful in school. Combined with these experiences, students in foster care lack the same access to resources and support as their peers. To this end, school counselors have the opportunity to utilize their unique position within the school community to effectively serve and address the complex needs of students in foster care. This paper addresses the current research, presenting problems, implications, and interventions school counselors can utilize when working with this population.

Keywords: students, foster care, school counseling, support, interventions

In 2017, there were a total of 442,995 children and youth in the foster care system (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018). Given the number of these students in schools and communities, school counselors have the opportunity to utilize their position within the school system to identify, respond to, and advocate for the needs of students in foster care to ensure equity and access in all areas. Although all students need positive relationships and stability to be successful, students in foster care often lack the same access to support, resources, and opportunities as their peers (McKellar & Cowen, 2011; Palmieri & La Salle, 2017). These barriers and challenges contribute to gaps in achievement, relationships, and skills for these students (Palmieri & La Salle, 2017). Compared to their peers, students in foster care are more likely to be absent from school, repeat a grade, and change schools (Cutuli et al., 2013; Palmieri & La Salle, 2017; Unrau et al., 2012), which ultimately impacts their ability to establish and maintain relationships. Additionally, students in foster care are twice as likely to receive out-of-school suspensions, over three times as likely to receive special education services, and over 20% less likely to graduate from high school (National Working Group for Foster Care and Education [NWGFCE], 2018).

When it comes to higher education, students in foster care are less likely to enroll in college preparatory classes, attend college, and obtain a 4-year degree when compared to their peers (Kirk et al., 2013; Unrau et al., 2012). Research suggests that as little as 3%–10.8% of youth previously in foster care attain a 4-year degree, compared to the national college completion rate of 32.5% (NWGFCE, 2018). However, it is important for school counselors to realize that between 70%–84% of students in foster care desire going to college (Courtney et al., 2010; NWGFCE, 2018). Although students in foster care feel motivated to attend and complete college, academic achievement can easily become another barrier. On average, students in foster care receive both lower ACT scores and high school GPAs and perform lower on standardized tests compared to their peers—all of which influence one’s admission to college (O’Malley et al., 2015; Unrau et al., 2012).

Unfortunately, it is also common for students in foster care to experience other challenges that influence their success in school, such as trauma. Trauma can include abuse; neglect; and the loss of family members, friends, and communities (Scherr, 2014). Without adequate support, trauma can impact a student’s executive functioning and memory, ultimately affecting their ability to learn (Avery & Freundlich, 2009). Additionally, separation from family members, disrupted relationships, and frequent transitions lead to an increased risk for difficulties in expressing and regulating emotions, tolerating ambiguity, and problem-solving (O’Malley et al., 2015; Unrau et al., 2012). These interrelated and complex factors contribute to the achievement gap experienced by students in foster care as evidenced by lower academic achievement and less engagement in school (Pecora et al., 2006; Unrau et al., 2012).

Importance of Serving This Population

When considering interventions to support students in foster care, it is important to explore what they believe will be helpful for their growth and success. It is likely that the majority of students in foster care already feel a lack of control over what occurs in their lives (Scherr, 2014). Therefore, this is an opportunity to encourage student involvement while increasing student self-efficacy. Clemens et al. (2017) found that students in foster care emphasize the importance of having opportunities to connect with others in similar situations, learning practical skills, and implementing different strategies to better their lives. To provide a sense of normalcy and belonging, school counselors can advocate for interventions that promote connectedness and engagement with other students (Unrau et al., 2012).

Removing barriers, improving access to services, maintaining enrollment, improving attendance, and facilitating academic progress is critical in promoting success for students in foster care (Gilligan, 2007). Therefore, school counselors should be aware of the barriers related to access that exist for students in foster care and should be intentional in taking steps to remove any inequities. Working proactively and using a strengths-based approach that acknowledges the skills, strengths, and resiliency of students are ways in which school counselors can effectively meet the needs of students in foster care (Gilligan, 2007; Scherr, 2014). To illustrate, a strengths-based approach can be utilized with students who have anxious attachment patterns by acknowledging their ability to care for others, rather than focusing on the negative aspects of their attachment behaviors (e.g., being too “needy”). Although it can be easy to focus on the behaviors and disruptions that occur, school counselors have the opportunity to instead focus on these students’ accomplishments, strengths, and dreams. Ultimately, it is evident that students in foster care face many challenges that influence their ability to be successful. In an effort to address this need, the following section outlines interventions for school counselors to use when working with students in foster care.

Interventions

School Climate

Positive school relationships are an essential part of school climate and can serve as a protective factor for students experiencing adversity (Furlong et al., 2011; O’Malley et al., 2015). Therefore, focusing on school climate may be an effective approach in supporting students in foster care, as positive school relationships can also help close achievement gaps between these students and their peers (Clemens et al., 2017). For example, positive school climate decreases rates of disruptive behaviors, truancy, fights, and suspensions at school (Hopson & Lee, 2011). In addition, Voight et al. (2013) found that students’ positive school climate perceptions also contributed to academic achievement as indicated by state standardized test scores. School counselors can enhance school climate by allowing student voices, utilizing empowerment strategies, implementing evidence-based programs, providing adult mentoring (O’Malley et al., 2015), and working to create a positive peer culture (Bergin & Bergin, 2009).

School Culture

It is particularly important to pay attention to school culture, as these shared norms, beliefs, and behaviors affect perceptions of school climate (MacNeil et al., 2009). To create a positive school culture, Ziomek-Daigle et al. (2016) recommended that school counselors implement interventions using a multi-tiered system of supports. For example, providing classroom lessons on topics such as kindness, empathy, and acceptance are Tier 1 interventions that work to cultivate a positive school culture (Bergin & Bergin, 2009; Ziomek-Daigle et al., 2016). Additionally, school culture can be influenced by creating shared values and expectations for students throughout the school community (MacNeil et al., 2009). For example, school counselors can utilize empowerment strategies when teaching students in foster care to advocate for themselves and find autonomy in meeting their needs. The school counselor might say, “Last week, you worked so hard at learning to use ‘I statements’ when expressing your needs and feelings to others! In class, I even saw that you raised your hand to ask for a break when you started to get overwhelmed in math. How might you use similar skills to advocate for yourself when you get frustrated in social studies?” In this way, the school counselor is improving school culture by creating a shared expectation among students, teachers, and staff.

Educational Experiences

Moreover, school counselors can enhance school climate by facilitating enriching educational experiences that contribute to academic success (Gilligan, 2007). To ensure that students in the foster care system receive the same educational experiences as their peers, school counselors can screen, monitor, plan, communicate, and collaborate with other stakeholders (e.g., teachers, administration, staff, and foster families) to ensure equity and access for students in foster care (Palmieri & La Salle, 2017). Educating stakeholders about working with students in foster care can encourage inclusive assignments, promote an understanding of potential responses and reactions from students, and decrease negative behavioral perceptions (McKellar & Cowen, 2011). Additionally, including students in decisions about their education, where they attend school, and the support they receive can increase their self-efficacy, goal development, and self-advocacy skills (Palmieri & La Salle, 2017). This intentionality can also help them feel welcome, respected, and important—all of which increase their school connection.

Collaborating With Stakeholders

Planning

School counselors should plan to accommodate and work with students who may enter school in the middle of the year, as 34% of students in foster care experience five or more school changes by the time they reach the age of 18 (NWGFCE, 2018). When these students arrive at school, it is important that school counselors welcome them, explain classroom and school procedures, show them around the school, and facilitate connections with other students (Palmieri & La Salle, 2017). From the beginning, school counselors can prioritize involving the foster family by calling to welcome them, answering any questions they have, providing them with helpful information (e.g., teacher contact information), and following up with them after a few weeks. For example, packets can be sent home with students so foster families have access to any relevant documents or previous newsletters containing helpful information (McKellar & Cowen, 2011). Additionally, it may be beneficial for school counselors to invite the foster family to meet with them in person to create a stronger foster family and school partnership. Furthermore, incomplete student records can have a significant effect on academic services for students in foster care. Therefore, school counselors should work diligently with other school districts to retrieve and maintain these records (McKellar & Cowen, 2011).

Training

Along with planning, school counselors can provide all stakeholders with evidence-based information to effectively serve and address the needs of students in foster care (Kerr & Cossar, 2014). With this purpose in mind, school counselors can provide training to stakeholders on topics such as reflective listening, creating secure attachments, recognizing and responding to feelings and behaviors, and setting limits and boundaries (Kerr & Cossar, 2014). Informed stakeholders can more effectively support and respond to the unique needs of students in foster care, and in turn, students may be more successful in managing their emotions and behaviors (Palmieri & La Salle, 2017). This awareness can also strengthen relationships that promote school success (Kerr & Cossar, 2014). Additionally, school counselors can be proactive in collaborating with stakeholders to create structured and supportive classroom environments where students in foster care feel safe while learning. For example, working with teachers to modify assignments that have the potential to be triggering (e.g., family-based assignments) is essential in promoting student–teacher relationships and academic achievement (C. Mitchell, 2010; Palmieri & La Salle, 2017).

Inclusion

Students in foster care often experience triggers at school, whether it is from an assignment (e.g., family-based assignments), a topic discussed in class, or a community event that seems to be exclusively for biological parents (West et al., 2014). When these experiences occur, students in foster care do not always have the ability to self-regulate and utilize healthy coping skills (West et al., 2014). For this reason, it is essential to not only advocate for inclusive assignments and events but to also help students effectively manage their triggers so they can be academically and relationally successful. Additionally, it may be helpful to provide stakeholders with information about why certain activities lack inclusivity for students in foster care and offer possible alternatives or modifications for these experiences. To illustrate, events such as “Muffins with Moms” and “Donuts with Dads” can be altered for inclusivity by expanding the population to include anyone in the student’s support system (e.g., “Floats with Friends” or “Popcorn with Important People”).