Dec 2, 2014 | Article, Volume 4 - Issue 5

Ian Martin, John Carey

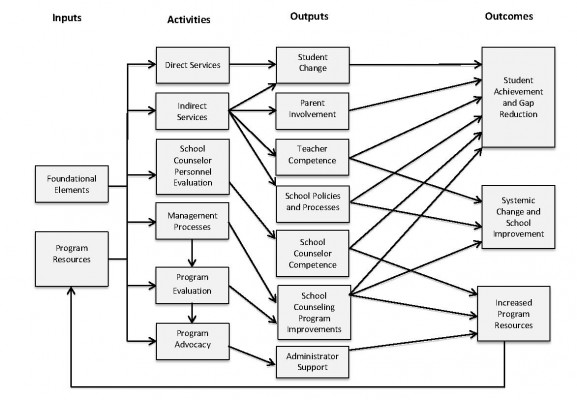

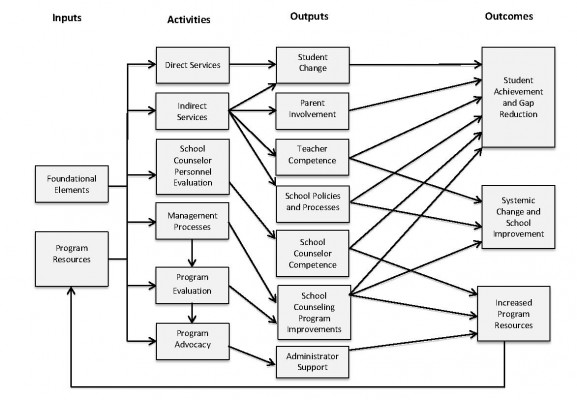

A logic model was developed based on an analysis of the 2012 American School Counselor Association (ASCA) National Model in order to provide direction for program evaluation initiatives. The logic model identified three outcomes (increased student achievement/gap reduction, increased school counseling program resources, and systemic change and school improvement), seven outputs (student change, parent involvement, teacher competence, school policies and processes, competence of the school counselors, improvements in the school counseling program, and administrator support), six major clusters of activities (direct services, indirect services, school counselor personnel evaluation, program management processes, program evaluation processes and program advocacy) and two inputs (foundational elements and program resources). The identification of these logic model components and linkages among these components was used to identify a number of necessary and important evaluation studies of the ASCA National Model.

Keywords: ASCA National Model, school counseling, logic model, program evaluation, evaluation studies

Since its initial publication in 2003, The ASCA National Model: A Framework for School Counseling Programs has had a dramatic impact on the practice of school counseling (American School Counselor Association [ASCA], 2003). Many states have revised their model of school counseling to make it consistent with this model (Martin, Carey, & DeCoster, 2009), and many schools across the country have implemented 3the ASCA National Model. The ASCA Web site, for example, currently lists over 400 schools from 33 states that have won a Recognized ASCA Model Program (RAMP) award since 2003 as recognition for exemplary implementation of the model (ASCA, 2013).

While the ASCA National Model has had a profound impact on the practice of school counseling, very few studies have been published that evaluate the model itself. Evaluation is necessary to determine if the implementation of the model results in the model’s anticipated benefits and to determine how the model can be improved. The key studies typically cited (see ASCA, 2005) as supporting the effectiveness of the ASCA National Model (e.g., Lapan, Gysbers, & Petroski, 2001; Lapan, Gysbers, & Sun, 1997) were actually conducted before the model was developed and were designed as evaluations of Comprehensive Developmental Guidance, which is an important precursor and component of the ASCA National Model, but not the model itself.

Two recent statewide evaluations of school counseling programs focused on the relationships between the level of implementation of the ASCA National Model and student outcomes. In a statewide evaluation of school counseling programs in Nebraska, Carey, Harrington, Martin, and Hoffman (2012) found that the extent to which a school counseling program had a well-implemented, differentiated delivery system consistent with practices advocated by the ASCA National Model was associated with lower suspension rates, lower discipline incident rates, higher attendance rates, higher math proficiency and higher reading proficiency. These results suggest that model implementation is associated with increased student engagement, fewer disciplinary problems and higher student achievement. In a similar statewide evaluation study in Utah, Carey, Harrington, Martin, and Stevens (2012) found that the extent to which the school counseling program had a programmatic orientation, similar to that advocated in the ASCA National Model, was associated with both higher average ACT scores and a higher number of students taking the ACT. This suggests that model implementation is associated with both increased achievement and a broadening of student interest in college. While these studies suggest that benefits to students are associated with the implementation of the ASCA National Model, additional evaluations are necessary that use stronger (e.g., quasi-experimental and longitudinal) designs and investigate specific components of the model in order to determine their effectiveness or how they can be improved.

There are several possible reasons why the ASCA National Model has not been evaluated extensively. The school counseling field as a whole has struggled with general evaluation issues. For example, questions have been raised regarding the effectiveness of practitioner training in evaluation (Astramovich, Coker, & Hoskins, 2005; Heppner, Kivlighan, & Wampold, 1999; Sexton, Whiston, Bleuer, & Walz, 1997; Trevisan, 2000); practitioners have cited lack of time, evaluation resources and administrative support as major barriers to evaluation (Loesch, 2001; Lusky & Hayes, 2001); and some practitioners have feared that poor evaluation results may negatively impact their program credibility (Isaacs, 2003; Schmidt, 1995). Another contributing factor is that while the importance of evaluation is stressed in the literature, few actual examples of program evaluations and program evaluation results have been published (Astramovich & Coker, 2007; Martin & Carey, 2012; Martin et al., 2009; Trevisan, 2002).

In addition, there are several features of the ASCA National Model that make evaluations difficult. First, the model is complex, containing many components grouped into four interrelated, functional subsystems referred to as the foundation, delivery system, management system and accountability system. Second, ASCA created the National Model by combining elements of existing models that were developed by different individuals and groups. For example, the principle influences of the model (ASCA, 2012) are cited as Gysbers and Henderson (2000), Johnson and Johnson (2001) and Myrick (2003). Furthermore, principles and concepts derived from important movements such as the Transforming School Counseling Initiative (Martin, 2002) and evidence-based school counseling (Dimmitt, Carey, & Hatch, 2007) also were incorporated into the model during its development. While these preexisting models and movements share some common features, they differ in important ways. Elements of these approaches were combined and incorporated into the ASCA National Model without a full integration of their philosophical and theoretical perspectives and principles. Consequently, the ASCA National Model does not reflect a single cohesive approach to program organization and management. Instead, it reflects a collection of presumably effective principles and practices that have been applied in school counseling programs. Third, instruments for measuring important aspects of model implementation are lacking (Clemens, Carey, & Harrington, 2010). Fourth, the theory of action of the ASCA National Model has not been fully explicated, so it is difficult to determine what specific benefits are intended to result from the implementation of specific elements of the model. For example, it is not entirely clear how changing the performance evaluation of counselors is related to the desired benefits of the model.

In this article, the authors present the results of their work in developing a logic model for the ASCA National Model. Logic modeling is a systematic approach to enabling high-quality program evaluation through processes designed to result in pictorial representations of the theory of action of a program (Frechtling, 2007). Logic modeling surfaces and summarizes the explicit and implicit logic of how a program operates to produce its desired benefits and results. By applying logic modeling to an analysis of the ASCA National Model, the authors intended to fully explicate the relationships between structures and activities advocated by the model and their anticipated benefits so that these relationships can be tested in future evaluations of the model.

The purpose of this study, therefore, was to develop a useful logic model that describes the workings of the ASCA National Model in order to promote its evaluation. More specifically, the purpose was to mine the logic elements, program outcomes and implicit (unstated) assumptions about the relationships between program elements and outcomes. In developing this logic model, the authors followed the processes suggested by the W. K. Kellogg Foundation (2004) and Frechtling (2007). Several different frameworks exist for logic models, but the authors elected to use Frechtling’s framework because it focuses specifically on promoting evaluation of an existing program (as opposed to other possible uses such as program planning). This framework identifies the relationships among program inputs, activities, outputs and outcomes. Inputs refer to the resources needed to deliver the program as intended. Activities refer to the actual program components that are expected to be related to a desired outcome. Outputs refer to the immediate products or results of activities that can be observed as evidence that the activity was actually completed. Outcomes refer to the desired benefits of the program that are expected to occur as a consequence of program activities. The authors’ logic model development was guided by four questions:

What are the essential desired outcomes of the ASCA National Model?

What are the essential activities of the ASCA National Model and how do these activities relate to its outputs?

What are the essential outputs of the ASCA National Model and how do these outputs relate to its desired outcomes?

What are the essential inputs of the ASCA National Model and how do these inputs relate to its activities?

Methods

All analyses in this study were based on the latest edition of the ASCA National Model (ASCA, 2012). In these analyses, every attempt was made to base inferences on the actual language of the model. In some instances (for example, when it was unclear which outputs were expected to be related to a given activity) the professional literature about the ASCA National Model was consulted.

Because the authors intended to develop a logic model from an existing program blueprint (rather than designing a new program), they began, according to recommended procedures (W. K. Kellogg Foundation, 2004), by first identifying outcomes and then working backward to identify activities, then outputs associated with activities and finally, inputs.

Identification of Outcomes

The authors independently reviewed the ASCA National Model (2012) and identified all elements in the model. The two authors’ lists of elements (e.g., vision statement, annual agreement with school leaders, indirect service delivery and curriculum results reports) were merged to create a common list of elements. The authors then independently created a series of if, then statements for each element of the model that traced the logical connections explicitly stated in the model (or in rare instances, stated in the professional literature about the model) between the element and a program outcome. In this way, both the desired outcomes of the ASCA National Model and the desired logical linkages between elements and outcomes were identified.

During this process, some ASCA National Model elements were included in the same logic sequence because they were causally related to each other. For example, both the vision statement and the mission statement were included in the same logic sequence because a strong vision statement was described as a necessary prerequisite for the development of a strong mission statement. Some ASCA National Model elements also were included in more than one logical sequence when it was clear that two different outcomes were intended to occur related to the same element. For example, it was evident that closing-the-gap reports were intended to result in intervention improvements, leading to better student outcomes and also to apprising key stakeholders of school counseling program results, in order to increase support and resources for the program.

Identification of Activities

Frechtling (2007) noted that the choice of the right amount of complexity in portraying the activities in a logic model is a critically important factor in a model’s utility. If activities are portrayed in their most differentiated form, the model can be too complex to be useful. If activities are portrayed in their most compact form, the model can lack enough detail to guide evaluation. Therefore, in the present study, the authors decided to construct several different logic models with different sets of activities that ranged from including all the previously identified ASCA National Model elements as activities to including only the four sections of the ASCA National Model (i.e., foundation, management system, delivery system and accountability system) as activities. As neither of the two extreme options proved to be feasible, the authors began clustering ASCA National Model elements and developed six activities, each of which represented a cluster of program elements.

Identification of Outputs Related to Activities

Outputs are the observable immediate products or deliverables of the logic model’s inputs and activities (Frechtling, 2007). After the authors identified an appropriate level for representing model activities, they generated the same level of program outputs. Reexamining the logic sequences, clustering products of identified activities and then creating general output categories from the clustered products accomplished this task. For example, the activity known as direct services contained several ASCA National Model products, such as the curriculum results report, the small-group results report and the closing-the-gap results report (among others), and the resulting output was finally categorized as student change. Ultimately, seven logic model outputs were identified through this process to help describe the outputs created by ASCA National Model activities.

Identifying the Connections Between Outputs and Outcomes

Creating connections between model outputs and outcomes was accomplished by linking the original logic sequences to determine how the ASCA National Model would conceive of outputs as being linked to outcomes. Returning to the above example, the output known as student change, which included such products as results reports, was connected to the outcome known as student achievement and gap reduction in several logic sequences. At the conclusion of this process, each output had straightforward links to one or multiple proposed model outcomes. Not only was this process useful in identifying links between outputs and outcomes, but it also functioned as an opportunity to test the output categories for conceptual clarity.

Identification of Inputs and Connections Between Inputs and Activities

The authors reviewed the ASCA National Model to determine which inputs were necessary to include in the logic model. They identified two essential types of inputs: foundational elements (conceptual underpinnings described in the foundation section of the ASCA National Model) and program resources (described throughout the ASCA National Model). The authors determined that these two types of inputs were necessary for the effective operation of all six activities.

Identifying Other Connections Within the Logic Model

After the inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes and the connections between these levels were mapped, the authors again reviewed the logic sequences and the ASCA National Model to determine if any additional linkages needed to be included in the logic model (see Frechtling, 2007). They evaluated the need for within-level linkages (e.g., between two activities) and feedback loops (i.e., where a subsequent component influences the nature of preceding components). The authors determined that two within-level and one recursive linkage were needed.

Results

Outcomes

A total of 65 logic sequences were identified for the ASCA National Model sections: foundation (n = 7), management system (n = 30), delivery system (n = 7) and accountability system (n = 21). Table 1 contains sample logic sequences.

Table 1

Examples of Logic Sequences Relating ASCA National Model Elements to Outcomes

|

National Model

Section

|

Logic Sequence

|

|

|

|

|

| Foundation |

a. If counselors go through the process of creating a set of shared beliefs, then they will establish a level of mutual understanding.b. If counselors establish a level of mutual understanding, then they will be more successful in developing a shared vision for the program.c. If counselors develop a shared vision for the program, then they can develop an effective vision statement.d. If counselors create a vision statement, then they will have the clarity of purpose that is needed to develop a mission statement.e. If counselors create a mission statement, then the program will be more focused.f. If the program is better focused, counselors will create a set of program goals, which will enable counselors to specify how the attainment of the goals should be measured.

g. If counselors specify how the attainment of goals should be measured, then effective program evaluation will be conducted.

h. If effective program evaluation is conducted, then the program will be continuously improved.

i. If the program will be continuously improved, then improved student achievement will result. |

| Management System |

a. If school counselors create annual agreements with the leader in charge of the school, then the goals and activities of the counseling program will be more aligned with the goals of the school.b. If the goals and activities of the counseling program are more aligned with the goals of the school, then school leaders will recognize the value of the school counseling program.c. If school leaders recognize the value of the school counseling program, then they will commit resources to support the program. |

| Delivery System |

a. If school counselors engage in indirect services (e.g., consultation and advocacy), then school policies and processes will improve.b. If school policies and processes improve, then teachers will develop more competency, and systemic change and school improvement will occur. |

| Accountability System |

a. If counselors complete curriculum results reports, then they will have the information they need to demonstrate the effectiveness of developmental and preventative curricular activities.b. If counselors have the information they need to demonstrate the effectiveness of developmental and preventative curricular activities, then they can communicate their impact to school leaders.c. If school leaders are aware of the impact of developmental and preventative curricular activities, then they will recognize their value.d. If school leaders recognize the value of developmental and preventative curricular activities, then they will commit resources to support them. |

Forty of these logic sequences terminated with an outcome related to increased student achievement or (relatedly) to a reduction in the achievement gap. Twenty-two sequences terminated with an outcome related to an increase in program resources. Only three sequences terminated with an outcome related to systemic change in the school. From this analysis, the authors concluded that the primary desired outcomes of the ASCA National Model are increased student achievement/gap reduction and increased school counseling program resources. They also concluded that systemic change and school improvement is another desired outcome of the ASCA National Model.

Activities

Based on a clustering of ASCA National Model elements identified previously, six activities were developed for the logic model. These activities included the following: direct services, indirect services, school counselor personnel evaluation, program management processes, program evaluation processes and program advocacy processes. Each of these activities represents a cluster of elements within the ASCA National Model. For example, the activity known as direct services includes the school counseling core curriculum, individual student planning and responsive services. Consequently, the direct services activity represents the spectrum of services that would be delivered to students in an ASCA National Model school counseling program.

Activities Related to Outputs

Based on the clustering of the ASCA National Model products or deliverables around the related logic model activities, seven outputs were identified. These outputs included the following: student change, parent involvement, teacher competence, school policies and processes, school counselor competence, school counseling program improvements, and administrator support. The outputs represent all of the ASCA National Model products generated by model activities and help to collect evidence and determine to what degree an activity was successfully accomplished. In essence, for evaluation purposes, these outputs represent the intermediate outcomes (Dimmitt et al., 2007) of an ASCA National Model program. Activities should result in measurable changes in outputs, which in turn should result in measurable changes in outcomes. For example, the output known as student change reflects student changes such as increased academic motivation, increased problem-solving skills, enhanced emotional regulation and better interpersonal problem-solving skills; these changes lead to the longer-term outcome of student achievement and gap reduction.

Connections Between Outputs and Outcomes

Connecting the seven ASCA National Model outputs to its outcomes strengthens the logic model by identifying the hypothesized relationships between the more immediate changes that result from school counseling program activities (i.e., outputs) and the more distal changes that result from the operation of the program (i.e., outcomes). As described earlier, two primary outcomes (student achievement and gap reduction and increased program resources) and one secondary outcome (systemic change and school improvement) were identified within the ASCA National Model. Three of the seven outputs (student change, parent involvement and administrator support) were connected to only one outcome. Three other outputs (teacher competence, school policies and processes, and school counselor competence) were connected to two outcomes. One output (administrator support) was connected to all three outcomes. Interpreting these linkages is useful in understanding the implicit theory of change of the ASCA National Model and consequently in designing appropriate evaluation studies. The authors’ logic model, for example, indicates that student changes (related to both direct and indirect services of an ASCA National Model program) are expected to result in measurable increases in student achievement and a reduction in the achievement gap.

It also is helpful to scan backward in the logic model to identify how changes in outcomes are expected to occur. For example, student achievement and gap reduction is linked to six model outputs (student change, parent involvement, teacher competence, school policies and processes, school counselor competence, and school counseling program improvements). Student achievement and gap reduction is multiply determined and is the major focus of the ASCA National Model. Increased program resources are connected to three model outputs (school counselor competence, school counseling program improvements and administrator support). Systemic change and school improvement also can be connected to three outputs (teacher competence, school policies and processes, and school counseling program improvements).

Inputs and Connections Between Inputs and Activities

Based on an analysis of the ASCA National Model, two inputs were identified for inclusion in the logic model: foundational elements (which include the elements in the ASCA National Model’s foundation section considered important for program planning and operation) and program resources (which include elements essential for effective program implementation such as counselor caseload, counselor expertise, counselor professional development support, counselor time-use and program budget). Both of these inputs were identified as being important in the delivery of all six activities.

Additional Connections Within the Logic Model

Based on a final review of the logical sequences and another review of the ASCA National Model, three additional linkages were added to the authors’ logic model. The first linkage was a unidirectional arrow leading from management processes to program evaluation in the activities column. This arrow was intended to represent the tight connection between management processes and evaluation activities that is evident in the ASCA National Model. Relatedly, a unidirectional arrow leading from the school counseling program evaluation activity to the program advocacy activity was added. This arrow was intended to represent the many instances of the ASCA National Model suggesting that program evaluation activities should be used to generate essential information for program advocacy. The final additional link was a recursive arrow leading from the increased program resources outcome to the program resources input. This linkage was intended to represent the ASCA National Model’s concept that investment of additional resources resulting from successful implementation and operation of an ASCA National Model program will result in even higher levels of program effectiveness and eventually even better outcomes.

The Logic Model

Figure 1 contains the final logic model for the ASCA National Model for School Counseling Programs. Logic models portray the implicit theory of change underlying a program and consequently facilitate the evaluation of the program (Frechtling, 2007). Overall, the theory of change for an ASCA national program could be described as follows: If school counselors use the foundational elements of the ASCA National Model and have sufficient program resources, they will be able to develop and implement a comprehensive program characterized by activities related to direct services, indirect services, school counselor personnel evaluation, management processes, program evaluation and (relatedly) program advocacy. If these activities are put in place, several outputs will be observed, including the following: student changes in academic behavior, increased parent involvement, increases in teacher competence in working with students, better school policies and processes, increased competence of the school counselors themselves, demonstrable improvements in the school counseling program, and increased administrator support for the school counseling program. If these outputs occur, then the following outcomes should result: increased student achievement and a related reduction in the achievement gap, notable systemic improvement in the school in which the program is being implemented, and increased program support and resources. If these additional resources are reinvested in the school counseling program, the effectiveness of the program will increase.

Figure 1. Logic Model for ASCA National Model for School Counseling Programs

Discussion

Logic models can be used for a number of purposes including the following: enhancing communication among program team members, managing the program, documenting how the program is intended to operate and developing an approach to evaluation and related evaluation questions (Frechtling, 2007). The present study was conducted in order to develop a logic model for ASCA National Model programs so that these programs could be more readily evaluated, and based on the results of these evaluations, the ASCA National Model could then be improved.

Evaluations can focus on the question of whether or not a program or components of a program actually result in intended changes. At the most global level, an evaluation can focus on discovering the extent to which the program as a whole achieves its desired outcomes. At a more detailed level, an evaluation can focus on discovering the extent to which the components (i.e., activities) of the program achieve their desired outputs (with the assumption that achievement of the outputs is a necessary precursor to achievement of the outcomes).

In both types of evaluations, it is important to use a design that allows some form of comparison. In the simplest case, it would be possible to compare outputs and outcomes before and after implementation of the ASCA National Model. In more complex cases, it would be possible to compare outputs and outcomes of programs that have implemented the ASCA National Model with programs that have not. In these cases, it is essential to control for the confounding effects of extraneous variables (e.g., the affluence of students in the school) by the use of matching or covariates. If the level of implementation of the ASCA National Model program as a whole can be measured, it is even possible to use multivariate correlation approaches to examine whether the level of implementation of the program is related to desired outcomes while simultaneously controlling statistically for potential confounding variables. These same correlational procedures can be used to examine the relationships between the more discrete activities of the program and their corresponding outputs.

At the most global level, it is important to evaluate the extent to which the implementation of the ASCA National Model results in the following: increases in student achievement (and associated reductions in the achievement gap), measurable systemic change and school improvements, and increases in resources for the school counseling program. At present, there is some evidence that implementation of the ASCA National Model is related to achievement gains (Carey, Harrington, Martin, & Hoffman, 2012; Carey, Harrington, Martin, & Stevens, 2012). No evaluations to date have examined whether ASCA National Model implementation results in systemic change and school improvement or in an increase in program resources.

It also is important to evaluate the extent to which specific program activities achieve their desired outputs. Table 2 contains a list of sample evaluation questions for each activity. Within these questions, evaluation is focused on whether or not components of the program result in overall benefits. No evaluation study to date has evaluated the impact of ASCA National Model implementation on these factors.

Table 2

Sample Evaluation Questions for ASCA National Model Activities

|

Activities

|

Evaluation Questions

|

|

|

|

|

| Direct Services |

Does organizing and delivering school counseling direct services in accordance with ASCA National Model principles result in an increase in important aspects of students’ school behavior that are related to academic achievement? |

| Indirect Services |

Does organizing and delivering school counseling indirect services in accordance with ASCA National Model principles result in an increase in parent involvement? |

| Does organizing and delivering school counseling indirect services in accordance with ASCA National Model principles result in an increase in teachers’ abilities to work effectively with students? |

| Does organizing and delivering school counseling indirect services in accordance with ASCA National Model principles result in improvements in school policies and procedures that support student achievement? |

| School Counselor Personnel Evaluation |

Does the implementation of personnel and processes recommended by the ASCA National Model result in increases in the professional competence of school counselors? |

| Management Processes |

Does the implementation of the management processes recommended by the ASCA National Model result in demonstrable improvements in the school counseling program? |

| Program Evaluation |

Does the implementation of program evaluation processes recommended by the ASCA National Model result in demonstrable improvements in the school counseling program? |

| Program Advocacy |

Does the implementation of the program advocacy practices recommended by the ASCA National Model result in increases in administrator support for the program? |

In addition to examining program-related change, it is important to evaluate whether a basic assumption of the ASCA National Model bears out in reality. The major assumption is that school counselors who use the foundational elements of the ASCA National Model (e.g., vision statement, mission statement) and have access to typical levels of program resources can develop and implement all the activities associated with an ASCA National Model program (e.g., direct services, indirect services, school counselor personnel evaluation, management processes, program evaluation and program advocacy). Qualitative evaluations of the relationships between inputs and quality of the activities are necessary to determine what levels of inputs are necessary for full implementation. While full evaluation studies of this type have yet to be undertaken, Martin and Carey (2012) have recently reported the results of a two-state qualitative comparison of how statewide capacity-building activities to promote school counselors’ competence in evaluation were used to promote the widespread implementation of ASCA National Model school counseling programs. More studies of this type that focus on the relationships between a broader range of program inputs and school counselors’ ability to fully implement ASCA National Model program activities are needed.

Limitations and Future Directions

Constructing a logic model retrospectively is inherently challenging and complex. This is especially true when the program for which the logic model is being created was not initially developed with reference to an explicit, coherent theory of action. In the present study, the authors approached the work systematically and are confident that others following similar procedures would generate similar results. With that said, a limitation of this work is that the logic model was created based on the authors’ analyses of the written description of the ASCA National Model (2012) and literature surrounding the ASCA National Model. Engaging individuals who were involved in the development and implementation of the ASCA National Model in dialogue might have resulted in a richer logic model with even more utility in directing evaluation of the ASCA National Model. As a follow-up to the present study, the authors intend to continue this inquiry by asking key individuals involved with the ASCA National Model to evaluate the present logic model and to suggest revisions and extensions. Even given this limitation, the current study has potential immediate implications for improving practice that go beyond its role in providing focus and direction for ASCA National Model evaluation.

A potentially fertile testing ground for the implementation of the logic model is present within the RAMP Award process. As aforementioned, RAMP awards are given to exemplary schools that have successfully implemented the ASCA National Model. Currently, schools provide evidence (data) and create narratives regarding how they have successfully met RAMP criteria. Twelve independent rubrics are scored and totaled to determine whether a school receives a RAMP Award. At least two contributions of the logic model for improving the RAMP process seem feasible. First, practitioners can use the logic model to help construct narratives that better articulate how ASCA National Model activities/outputs relate to model outcomes. Second, the logic model may also help improve the RAMP process by highlighting clearer links between activities, outputs and outcomes. In future revisions of the RAMP process, more attention could be paid to the documentation of benefits achieved by the program in terms of both outputs (i.e., the immediate measurable positive consequences of program activities) and outcomes (i.e., the longer-term positive consequences of program operation). In this vein, the authors hope that the logic model developed in this study will help to improve the RAMP process for both practitioners and RAMP evaluators.

Retrospective logic models map a program as it is. In that sense, they are very useful in directing the evaluation of existing programs. Prospective logic models are used to design new programs. Using logic models in program design (or redesign) has some distinct advantages. “Logic models help identify the factors that will impact your program and enable you to anticipate the data and resources you will need to achieve success” (W. K. Kellogg Foundation, 2004, p. 65). When programs are planned with the use of a logic model, greater opportunities exist to explore foundational theories of change, to explore issues or problems addressed by the program, to surface community needs and assets related to the program, to consider desired program results, to identify influential program factors (e.g., barriers or supports), to consider program strategies (e.g., best practices), and to elucidate program assumptions (e.g., the beliefs behind how and why the strategies will work; W. K. Kellogg Foundation, 2004). The authors hope that logic modeling will be incorporated prospectively into the next revision process of the ASCA National Model. Basing future editions of the ASCA National Model on a logic model that comprehensively describes its theory of action should result in a more elegant ASCA National Model with a clearer articulation between its components and its desired results. Such a model would be easier to articulate, implement and evaluate. The authors hope that the development of a retrospective logic model in the present study will facilitate the prospective use of a logic model in subsequent ASCA National Model revisions. The present logic model provides a map of the current state of the ASCA National Model. It is a good starting point for reconsidering such questions as how the model should operate, whether the outcomes are the right outcomes, whether the activities are sufficient and comprehensive enough to lead to the desired outcomes, and whether the available program resources are sufficient to support implementation of program activities.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of

interest or funding contributions for

the development of this manuscript.

References

American School Counselor Association. (2003). The ASCA national model: A framework for school counseling programs. Alexandria, VA: Author.

American School Counselor Association. (2005). The ASCA national model: A framework for school counseling programs. (2nd ed.). Alexandria, VA: Author.

American School Counselor Association. (2012). The ASCA national model: A framework for school counseling programs (3rd ed.). Alexandria, VA: Author.

American School Counselor Association. (2013). Past RAMP Recipients. Retrieved from http://www.ascanationalmodel.org/learn-about-ramp/past-ramp-recipients

Astramovich, R. L., & Coker, J. K. (2007). Program evaluation: The accountability bridge model for counselors. Journal of Counseling & Development, 85, 162–172. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2007.tb00459.x

Astramovich, R. L., Coker, J. K., & Hoskins, W. J. (2005). Training school counselors in program evaluation. Professional School Counseling, 9, 49–54.

Carey, J., Harrington, K., Martin, I., & Hoffman, D. (2012). A statewide evaluation of the outcomes of ASCA National Model school counseling programs in rural and suburban Nebraska high schools. Professional School Counseling, 16, 100–107.

Carey, J. C., Harrington, K., Martin, I., & Stevens, D. (2012). A statewide evaluation of the outcomes of the implementation of ASCA National Model school counseling programs in high schools in Utah. Professional School Counseling, 16, 89–99.

Clemens, E. V., Carey, J. C., & Harrington, K. M. (2010). The school counseling program implementation survey: Initial instrument development and exploratory factor analysis. Professional School Counseling, 14, 125–134.

Dimmitt, C., Carey, J. C., & Hatch, T. A. (2007). Evidence-based school counseling: Making a difference with data-driven practices. New York, NY: Corwin Press.

Frechtling, J. A. (2007). Logic modeling methods in program evaluation. New York, NY: Wiley & Sons.

Gysbers, N. C., & Henderson, P. (2000). Developing and managing your school guidance program (3rd ed.). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Heppner, P. P., Kivlighan, D. M., Jr., & Wampold, B. E. (1999). Research design in counseling (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Isaacs, M. L. (2003). Data-driven decision making: The engine of accountability. Professional School Counseling, 6, 288–295.

Johnson, C. D., & Johnson, S. K. (2001). Results-based student support programs: Leadership academy workbook. San Juan Capistrano, CA: Professional Update.

Lapan, R. T., Gysbers, N. C., & Petroski, G. F. (2001). Helping seventh graders be safe and successful: A statewide study of the impact of comprehensive guidance and counseling programs. Journal of Counseling & Development, 79, 320–330. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2001.tb01977.x

Lapan, R. T., Gysbers, N. C., & Sun, Y. (1997). The impact of more fully implemented guidance programs on the school experiences of high school students: A statewide evaluation study. Journal of Counseling & Development, 75, 292–302. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.1997.tb02344.x

Loesch, L. C. (2001). Counseling program evaluation: Inside and outside the box. In D. C. Locke, J. E. Myers, & E. L. Herr (Eds.), The handbook of counseling (pp. 513–525). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lusky, M. B., & Hayes, R. L. (2001). Collaborative consultation and program evaluation. Journal of Counseling & Development, 79, 26–38. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2001.tb01940.x

Martin, I., & Carey, J. C. (2012). Evaluation capacity within state-level school counseling programs: A cross-case analysis. Professional School Counseling, 15, 132–143.

Martin, I., Carey, J. C., & DeCoster, K. (2009). A national study of the current status of state school counseling models. Professional School Counseling, 12, 378–386.

Martin, P. J. (2002). Transforming school counseling: A national perspective. Theory Into Practice, 41, 148–153. doi:10.1207/s15430421tip4103_2

Myrick, R. D. (2003). Developmental guidance and counseling: A practical approach (4th ed.). Minneapolis, MN: Educational Media Corporation.

Schmidt, J. J. (1995). Assessing school counseling programs through external interviews. School Counselor, 43, 114–123.

Sexton, T. L., Whiston, S. C., Bleuer, J. C., & Walz, G. R. (1997). Integrating outcome research into counseling practice and training. Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Trevisan, M. S. (2000). The status of program evaluation expectations in state school counselor certification requirements. American Journal of Evaluation, 21, 81–94. doi:10.1177/109821400002100107

Trevisan, M. S. (2002). Evaluation capacity in K-12 school counseling programs. American Journal of Evaluation, 23, 291–305. doi:10.1016/S1098-2140(02)00207-2

W. K. Kellogg Foundation. (2004). Logic model development guide. Battle Creek, MI: Author.

Ian Martin is an assistant professor at the University of San Diego. John Carey is a professor at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and the Director of the Ronald H. Fredrickson Center for School Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation. Correspondence can be addressed to: Ian Martin, 5998 Alcala Park, San Diego, CA 92110, imartin@sandiego.edu.

Oct 15, 2014 | Article, Volume 3 - Issue 1

Jeffrey M. Warren, Edwin R. Gerler, Jr.

Consultation is an indirect service frequently offered as part of comprehensive school counseling programs. This study explored the efficacy of a specific model of consultation, rational emotive-social behavior consultation (RE-SBC). Elementary school teachers participated in face-to-face and online consultation groups aimed at influencing irrational and efficacy beliefs. A modified posttest, quasi-experimental design was utilized. Findings suggested face-to-face RE-SB consultation is useful in directly promoting positive mental health among teachers and indirectly fostering student success. Implications and recommendations for school counselors are presented.

Keywords: school counseling, irrational beliefs, rational emotive behavior therapy, consultation, efficacy beliefs, cognitive behavioral therapy

Professional school counselors are largely responsible for developing and maintaining comprehensive school counseling programs. Comprehensive programming includes collaboration and consultation aimed at supporting teachers and influencing student achievement. The recently released third edition of the ASCA National Model further supports collaboration and consultation to help teachers influence student achievement (ASCA, 2012). Consultation has been defined by Caplan (1970) as “a process of interactions between two professional persons—the consultant, who is a specialist, and the consultee, who invokes a consultant’s help in regard to a current work problem” (p. 19). More recently, Kampwirth and Powers (2012) noted that engaging in collaborative endeavors during the consultation process fosters egalitarian relationships and often yields the greatest degree of change. School counselors engaging in consultation with teachers from a collaborative perspective are typically successful in advancing educational opportunities and fostering student growth (Baker & Gerler, 2008; Schmidt, 2010; Schmidt, 2014; Sink, 2008).

Parsons and Kahn (2005) describe an integrated consultation model in which school counselors are agents of change and students are influenced systemically. In this model, for example, school counselors may provide consultation to a teacher or group of teachers in efforts to identify goals, solutions and resources aimed at meeting the needs of the school. School counselors also may engage in consultation when providing information, instructing or resolving adversities (Purkey, Schmidt, & Novak, 2010; Schmidt, 2010; Schmidt, 2014). Consultation can be conducted using various theoretical paradigms of counseling (see Crothers, Hughes, & Morine, 2008; Henderson, 1987; Jackson & Brown, 1986; Warren, 2010a). Regardless of the process or approach, however, it is important that school counselors consider consultee factors (i.e., training, culture, and emotional and cognitive characteristics) that may hinder or promote the consultation process (Brown, Pryzwansky, & Shulte, 2011).

In a review of the literature, Warren (2010b) suggested rational-emotive behavior consultation (REBC) was a viable means for addressing thoughts and emotions of teachers. REBC is a model of consultation based on rational-emotive behavior therapy (Ellis, 1962). In REBC, school counselors help identify and challenge irrational beliefs that impede teachers’ classroom performance. An irrational belief is considered a strong, unrealistic cognition that leads to self-destructive emotions and behaviors (Dryden, 2009). In a study conducted by Warren and Dowden (2012), relationships between teachers’ irrational beliefs and emotions were confirmed. REBC was effective in addressing irrational beliefs and promoting healthy emotions (Warren, 2010b, 2013a). Teachers who participated in face-to-face and asynchronous, online group consultation across eight weeks reported more flexible and preferential thought patterns as well as decreases in stress.

In addition to finding relationships between irrational beliefs and emotions, Warren and Dowden (2012) also noted that irrational beliefs and efficacy beliefs were strongly correlated. Efficacy beliefs are “beliefs in one’s capacity to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce given attainments” (Bandura, 1997, p. 3). Due to emerging research on irrational beliefs and efficacy beliefs, Warren and Baker (2013) explored the potential for school counselors to incorporate components of social cognitive theory (SCT; Bandura, 1986) in REBC. This integrated model of consultation uses converging aspects of SCT and REBT to comprehensively conceptualize cognitions and responses of teachers and students.

The present study builds on current literature and research related to school counselor consultation with teachers. Based on the work of Brown and Schulte (1987), Bernard and DiGiuseppe (1994), Warren (2010a, 2010b, 2013a), and Warren and Dowden (2012), rational emotive-social behavior consultation (RE-SBC) was employed in elementary schools via face-to-face and online formats. It was hypothesized that both modes of consultation would reduce the irrational beliefs of teachers. It also was hypothesized that efficacy beliefs would increase as a result of the consultation.

Method

Participants

Teacher participation was solicited during weekly staff meetings at three elementary schools in the southeastern United States. Information, including a recruitment letter about the study, was provided to prospective subjects during staff meetings. Across the three schools, 42 out of 67 teachers agreed to participate in the consultation; thirty-five teachers completed the study titled, Performance Enhancing Strategies and Techniques-Teachers (PEST-T). Thirty-two (91%)of the participants were female and three (9%) were male. The median years of teaching experience for the participants was between a range of six and fifteen.

Consultant

A doctoral candidate in counselor education and supervision provided rational emotive-social behavior consultation (RE-SBC) to both PEST-T treatment groups. The consultant’s work history included school counseling and private practice therapy. The primary theoretical orientation of the consultant was cognitive behavior therapy (CBT). The consultant, and author of this paper, completed primary and advanced practica in Rational Emotive-Cognitive Behavior Therapy at the Albert Ellis Institute in New York.

Study Design

A modified posttest, quasi-experimental design was implemented in this study. Participating teachers were grouped according to their school affiliation. The three groups were randomly assigned to one of three treatment conditions (face-to-face, online, or control). All participants completed a pretest. The posttest measures differed from those of the pretest.

Measures

The Irrational Beliefs Inventory (IBI), developed by Koopmans, Sanderman, Timmerman, and Emmelkamp (1994), was used in a preliminary analysis of the treatment groups. The IBI is a 50-item self-report measure used to assess irrational beliefs. The IBI was designed in an attempt to focus solely on irrational cognition, while isolating the construct from emotions (Bridges & Sanderman, 2002). The irrational beliefs measured on the IBI are consistent with those described in REBT (Ellis, 1962). A five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from “1” (strongly disagree) to “5” (strongly agree) is provided for respondents to demonstrate a level of agreement for each item. A sample item reads, “If I can’t keep something from happening, I don’t worry about it.” The IBI is scored by summing all item responses. Low scores reflect a tendency to think rationally, while high scores indicate a propensity to think irrationally. The IBI includes five factors: worrying, rigidity, need for approval, problem avoidance, and emotional irresponsibility. The internal consistency of the subscales of the IBI for American samples ranges from .69 (emotional irresponsibility) to .79 (worrying). When evaluated, the IBI was found more reliable and valid than other measures of irrational beliefs (DuPlessis, Moller, & Steel, 2004)

The General Self Efficacy Scale (GSES; Schwarzer & Jerusalem, 1995) is a measure of self-efficacy designed for use with general populations, but can be used as a measure for specific samples as well. Statements include “I can always manage to solve difficult problems if I try hard enough” and “I am confident that I could deal efficiently with unexpected events.” The ten self-report items are rated on a 4-point scale ranging from “1” (not at all true) to “4” (exactly true). Higher scores on the GSES indicate a greater sense of agency, or the capacity to act. In most samples, the mean score per GSES item was around 2.9. The internal consistency of the GSES is .86. The validity of this measure is well-documented by studies and related literature (Scholz, Dona, Sud, & Schwarzer, 2002).

The Teachers’ Irrational Beliefs Scale (TIBS; Bernard, 1990) is used to measure irrational beliefs of teachers; its 22 self-report items are scored on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). High scores on the TIBS suggest rigidity and irrationality. The irrational beliefs measured are consistent with the theory of REBT and include low frustration tolerance, ‘awfulizing,’ demandingness, and global worth/rating. The TIBS evaluates these irrational beliefs across various teaching-related areas. These areas are represented by four subscales: Self-Downing Attitudes, Low-Frustration Tolerance Attitudes, Attitudes to School Organization, and Authoritarian Attitudes Toward Students. These areas account for 41.5% of the variance, which is similar to other scales of irrationality, thus providing evidence for construct validity (Bora, Bernard, Trip, Decsei-Radu, & Chereji, 2009). Internal consistency for the English version of the TIBS ranges from .70–.85 across the subscales and the total scale score; test-rest reliability is .80.

The Teacher Sense of Efficacy Scale (TSES; Tschannen-Moran & Woolfolk Hoy, 2001) is a measure that captures teachers’ perceived efficacy consisting of 24 items rated on a nine-point scale anchored by “1” (Nothing) to “9” (A Great Deal). The TSES includes three subscales; Efficacy in Student Engagement, Efficacy in Instructional Strategies, and Efficacy in Classroom Management. The mean score for the TSES is 7.1. Higher scores on the TSES and its subscales indicate a greater likelihood for perceived control during the completion of teaching-related tasks. Low scores reflect a poor sense of ability to affect student learning. Reliability estimates for the three sub-scales, Engagement (.87), Instruction (.91), Management (.90), and the total scale (.94) of the TSES are high. Scores on the TSES are positively correlated to scores of other existing validated measures of teacher efficacy providing evidence for construct validity (Tschannen-Moran & Woolfolk Hoy, 2001).

Procedure

Participating teachers from one elementary school met face-to-face with the consultant. All participants from another school met asynchronously, online with the consultant. The participants of the remaining school were designated as the control group. The face-to-face group met in weekly seventy-minute consultation sessions, spanning an eight-week period. The online group consultation consisted of five, asynchronous, yet interactive discussion modules, completed across an eight-week period.

Both formats of the group consultation (PEST-T) were derived from a consultation model implemented by Warren (2010a, 2013a). Decreases in irrational beliefs were noted as a result of providing face-to-face and online consultation to teachers based on rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT; Ellis, 1962). Warren, (2010a) also found a negative relationship exists between irrational beliefs and efficacy beliefs. As a result of this finding and the extrapolation of theoretical nuances of SCT (Bandura, 1986) and REBT (Ellis, 1962), suggested by Warren (2010a, 2010b), participants in this study received group rational emotive-social behavioral consultation (RE-SBC).

During the first consultation session, the face-to-face group was presented with concepts including observational learning, efficacy and reciprocal determinism. Irrational beliefs, emotions, self-defeating behaviors and other principles of REBT were explored throughout the remaining group consultation sessions. Cognitive, emotive, and behavioral strategies and techniques for increasing rational thought and efficacy beliefs were provided and demonstrated throughout the consultation (see Ellis & MacLaren, 2005). Case examples and analogies focused on teaching and classroom situations were used to explain the information presented. Interactive discussions, songs, humor and participation in demonstrations were encouraged throughout the consultation.

Throughout the asynchronous, online group consultation, the consultant provided the participants with select, layperson-oriented articles on REBT and SCT. During each session, participants were asked to read articles provided via the discussion module. The discussion modules focused on ways to increase self-efficacy, the ABC model, benefits of living rationally, and how to dispute irrational beliefs. Participants were responsible for commenting on the readings and responding to other participants’ comments. The consultant moderated the discussion modules. Participants could access and complete the discussion modules at their convenience due to the asynchronous format of the group consultation. Participants were required to dedicate approximately 1.25 hours a week to the group consultation, completing the online discussion modules and applying concepts discussed to daily living. At the conclusion of the study, members of the control group received copies of the articles used during online consultation.

Results

Preliminary Analysis

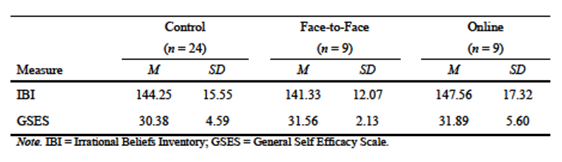

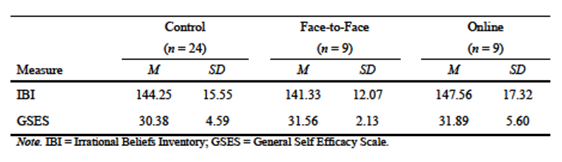

Univariate analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted on scores of the IBI and the GSES compiled from both treatment conditions and the control group. No significant differences were found among the three conditions in terms of irrational beliefs, F(2, 39) = .37, p > .05. Pre-test equivalency also was noted for efficacy beliefs for all conditions F(2, 39) = .48, p > .05. In summation, irrational beliefs and efficacy beliefs held by elementary school teachers in this study were comparable across all groups.

Treatment Efficacy

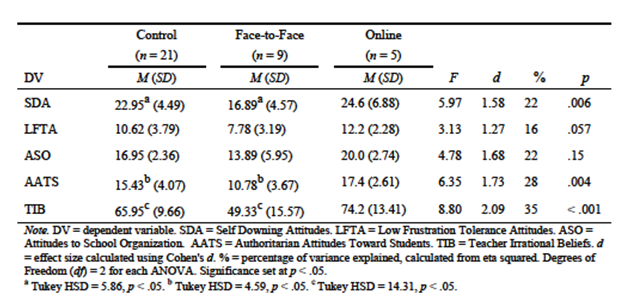

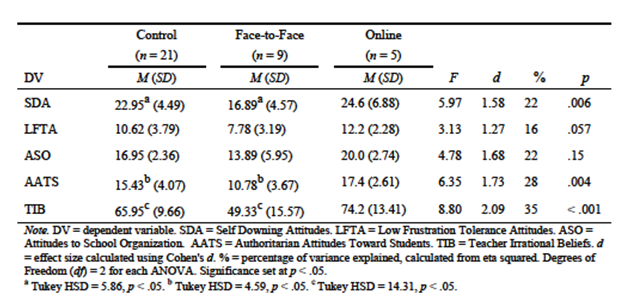

Means and standard deviations for the face-to-face, on-line and control groups are presented in Table 1. Teachers who received the treatments were expected to respond by maintaining fewer irrational beliefs than the control group. Analysis revealed statistical significance for teachers’ irrational beliefs, F(2, 33) = 8.80, p < .001, which accounted for approximately 35% of the variance among the three groups. Post hoc analyses using Tukey HSD criterion for significance indicated the average level of irrational beliefs was significantly lower in the face-to-face treatment (M = 49.33, SD = 15.57), when compared to the control group (M = 65.95, SD = 9.66). Contrary to the hypothesis, the effect of the on-line treatment on teachers’ irrational beliefs (M = 74.2, SD = 13.41) was not statistically different from the control group.

Table 1

Means and Standard Deviations of Pre-Intervention Measures

Further analyses on the items from the subscales of the TIBS provided additional insight into the effects of the treatments on specific irrational beliefs. Analysis of the three groups indicated statistical significance for self-downing attitudes (SDA), F(2, 35) = 5.97, p = .006. Post hoc comparisons indicated the mean for the face-to-face group (M = 16.89, SD = 4.57) statistically differed from the control group (M = 22.95, SD = 4.49) in terms of SDA. An omnibus ANOVA indicated that means for low frustration tolerance attitudes (LFTA) were not significantly different across groups, although a slight trend toward significance was present, F(2, 33) = 3.13, p = .057. Another analysis indicated statistical significance across groups for attitudes of school organization (ASO), F(2, 33) = 4.78, p =. 015. However, criterion for significance in a Tukey HSD analysis was not met when comparing the mean of the control group (M = 16.95, SD = 2.36) with the mean of either treatment, face-to-face (M = 13.89, SD = 5.95) or online (M = 20.0, SD = 2.74). Group means for authoritarian attitudes toward students (AATS) also were found to be statistically significant when an ANOVA was conducted, F(2, 33) = 6.35, p = .004. Post hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD analysis indicated the mean scores of the face-to-face treatment (M = 10.78, SD = 3.67) were significantly different from the control group (M = 15.43, SD = 4.07). However, the effect of the online treatment on AATS (M = 17.4, SD = 2.61) was not statistically different from the control group. The effects of the treatments on the participants’ irrational thoughts are presented in Table 2.

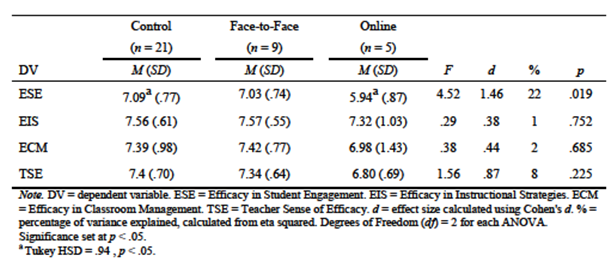

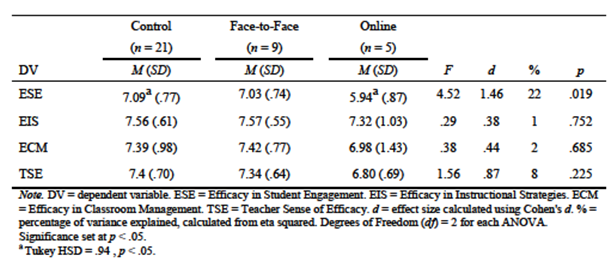

Table 2

Means, Standard Deviations, and Group Comparisons on Measures of Teachers’ Specific and General Irrational Beliefs at Posttest

It also was expected that participants receiving the treatments would report higher levels of efficacy than the control group. Results indicated no statistical significance across groups in terms of teacher sense of efficacy (TSE), F(2, 33) = 1.56, p = .225. Additional analyses were conducted on the subscales of the TSES. Analyses measuring the group differences in terms of efficacy in instructional strategies (EIS), F(2, 33) = .29, p = .752, and efficacy in classroom management (ECM), F(2, 33) = .38, p = .685, yielded no significant difference. A statistically significant difference was found on efficacy in student engagement (ESE) when the three groups were compared, F(2, 33) = 4.52, p = .018, accounting for 22% of the variance. A post hoc comparison indicated the mean of the face-to-face treatment (M = 7.03, SD = .74) was not significant in terms of ESE when compared to the control group (M = 7.09, SD = .77). However, the mean of the online group (M = 5.94, SD = .87) was significantly less than the mean of the control group. The effects of the treatments on the participants’ irrational thoughts are presented in Table 3.

Table 3

Means, Standard Deviations, and Group Comparisons on Measure of Specific and General Teacher Efficacy at Posttest

Discussion

The findings of this study contribute to the literature on consultation as an indirect, responsive service school counselors can incorporate in comprehensive programs. In this study, teachers participating in the face-to-face RE-SBC group reported fewer irrational beliefs as compared to the control group. While low frustration tolerance attitudes (LFTA) and attitudes of school organization (ASO) were not statistically different, participants reported significant differences in irrational beliefs related to self-downing attitudes (SDA) and authoritarian attitudes toward students (AATS). The face-to-face RE-SB consultation appeared successful; however, the online consultation was not found to be effective in decreasing teachers’ irrational beliefs. Inconsistent with expectation, the online group consultation appeared to increase irrational beliefs experienced by participants. Therefore, the hypothesis that both modes of consultation would reduce the irrational beliefs of teachers was partially supported.

The apparent impact of the face-to-face RE-SB group consultation on teachers’ irrational beliefs is consistent with previous studies exploring face-to-face REBT group consultation (see Forman & Forman, 1980; Warren, 2010b, 2013a). In each of these studies, group consultation was found to reduce irrational beliefs and promote positive mental health among teachers. In this study, the influence of RE-SB on specific teacher beliefs is particularly noteworthy, given the negative impact of self-downing and authoritarian teaching styles on student success (see Bernard & DiGiuseppe, 1994; Phelan, 2005).

RE-SB face-to-face group consultation did not appear to influence teacher efficacy beliefs. Efficacy beliefs remained relatively unchanged for this consultation group, as compared to the control group. This finding is important to note when considering concurrent lack of change in LFTA among face-to-face group consultation participants. In an explanation of school counselors’ use of cognitive behavioral consultation, Warren and Baker (2013) posited that teacher efficacy beliefs and low frustration tolerance beliefs converge. Teachers with low self-efficacy for engaging students, for example, essentially think student engagement is “too hard” or “unbearable,” signature thoughts of low frustration tolerance. Warren and Dowden (2012) supported this claim in a study exploring the relationships between irrational beliefs and efficacy beliefs of teachers. In short, since low frustration tolerance beliefs were not impacted by the consultation, a lack of change in efficacy beliefs is expected. The findings of this study may further support the relationship between these constructs. However, an alternative explanation for the lack of change in efficacy beliefs and LFTA of teachers participating in the face-to-face group consultation may lie with the presentation of the consultation. It is plausible that the delivery of the consultation, related to these constructs, was slightly flawed. Positive relationships have been noted between teacher efficacy and student achievement (Goddard, Hoy, & Woolfolk Hoy, 2004; Henson, 2001; Pintrich & Schunk, 1996; Ross, 1998). More emphasis on low frustration tolerance and teacher efficacy beliefs may be needed in this consultation model if a goal for school counselors is to indirectly impact student achievement.

Regarding the online group consultation, decreases in efficacy beliefs were found among these participants. The difference in efficacy in student engagement (ESE) was significant for participants in this group as compared to the control group. On-line consultation participants reported decreases in efficacy beliefs. This finding was contrary to the hypotheses that the consultation groups would increase teachers’ efficacy beliefs. Because neither consultation group was deemed to significantly increase efficacy beliefs of teachers, this hypothesis was not supported.

Implications and Recommendations for School Counselor

This study offers promise for school counselors eager to implement responsive services that have the potential to support teachers and effect systemic change. The study is consistent with current literature on school counseling practices suggesting the value of multilevel, responsive interventions that support teachers and students (see ASCA, 2012; Erford, 2011; Lee & Goodnough, 2011). Maximizing the success of students is a crucial role of professional school counselors (Dahir & Stone, 2012; Lapan, Gysbers, & Kayson, 2007). School counselors providing group consultation to teachers systemically influence student success (Parsons & Kahn, 2005). This consultation model, in its face-to-face format, has the potential to offer multilevel support, directly promoting positive mental health of teachers and indirectly influencing the success of students and parents. Teachers who think in rational ways will respond more favorably during encounters with students and parents, thus enhancing the relationship and the potential for educational success.

The findings of this study offer several implications for school counselors. First, school counselors should embrace the consultative role in their comprehensive school counseling programs. This includes intentional demonstrations of leadership, advocacy and collaboration. School counselors must play a leadership role when assessing and conceptualizing the social-emotional needs of teachers and students. Preparing, establishing and implementing systemic services such as group consultation also require leadership (Schmidt, 2014). School counselors providing consultation must possess adequate knowledge of school and classroom settings and how these environments interact with the social-emotional wellness of teachers and students. Advocacy for the success of teachers and students is inherently demonstrated by the leadership displayed when implementing responsive services such as consultation. School counselors should diligently and methodically find productive ways to advocate for students when engaging in RE-SB group consultation with teachers. As suggested by Kampwirth and Powers (2012), school counselors will find consultation with teachers is most effective when a collaborative approach is taken. Collaborating and teaming encourages teachers to be proactive and invest in the goals of the consultation efforts. School counselors can support teachers and students through consultation most readily, and ultimately effect systemic change when demonstrating these necessary roles of comprehensive services.

Next, school counselors will need to have a basic understanding of recent research and assessment procedures in order to determine the overall social-emotional health in their schools. By understanding the social-emotional climate, school counselors can tailor consultation efforts to meet individual and group needs of teachers and students. Based on recent research (Nucci, 2002; Pirtle & Perez, 2003) and data collection at the school level, school counselors may want to target beginning teachers, for example, for participation in RE-SBC. There are several models and approaches of RE-SBC that school counselors can use depending on the needs of the school (Warren & Baker, 2013).

Finally, school counselors must be knowledgeable of and understand how cognitive behavioral theory, specifically REBT, can be applied to the school setting. Some of the core tenets of REBT appear to debunk the typical mindset of teachers and school counselors. For example, teachers usually think that “students should listen and follow directions” or “parents should help their children with homework.” However, these thoughts are desirable, but not mandatory as the word “should” implies. Therefore, teachers may be skeptical, experience cognitive dissonance, or simply reject the content of the trainings altogether. School counselors will need to navigate theoretical concerns carefully, accepting teachers’ positions, yet providing clear alternative perspectives. While advanced training in REBT-CBT may not be required, it is vital that school counselors prepare and equip themselves appropriately for conducting group consultation (Warren, 2013b). Failure to adequately prepare will likely impact the effectiveness of the consultation.

Limitations and Future Research

The current study was limited in several ways. First, based on school affiliation, participants were grouped in either a control, face-to-face or online group. This cluster, convenience sampling may have led to non-equivalent groups. Preliminary analyses were conducted to control for this threat and to determine the level of homogeneity across groups. A two-stage random sample also may have been useful in ensuring randomness and equivalent groups (Ross, 2009).

Second, history is typically a threat to the validity of a study when the design includes only one group (Heppner, Kivlighan, & Wampold, 2008). Aspects of this study may be influenced by history, despite a three-group experimental design. Levels of stress for each group potentially increased toward the conclusion of the consultation due to upcoming end-of-grade testing. If this occurred, the posttest responses may have reflected the influence of the upcoming event, thus negating the true effects of the consultation. It also is important to note other factors that may have influenced the outcomes of this study, such as socio-cultural factors, the mean age of staff members, and the “culture” or “personality” each school assumes as a result of administrative leadership.

Next, experimenter expectancies may have influenced the responses of the participants beyond the effects of the consultation. If this occurred, the scores of the measures may be elevated, implying the training was more effective than it actually was. While the face-to-face group was most vulnerable to this threat due to the format of the consultation, differential attrition (44%) may have influenced the findings of the online group consultation.

Finally, all types of irrational beliefs were decreased, to some degree, for participants of the face-to-face consultation group. Teacher efficacy beliefs were not influenced and remained consistent with mean scores proposed by Tschannen-Moran and Woolfolk Hoy (2001). Due to the size of the sample of the face-to-face group, Type II errors may exist for LFTA and ASO and teacher efficacy beliefs. A significant difference may have existed, although not detected because of the limited number of participants.

Moving forward, this study may lead researchers in several directions. For example, conducting classroom observations or interviews of teachers post-consultation would provide insight into the lasting effects of the training. Ellis (2005) and Dryden (2009) have emphasized that cognitive change occurs most readily when individuals continue to challenge irrational beliefs and practice rational thinking. Replicating this study, while exploring the influence of the addition of homework assignments on irrational beliefs and efficacy beliefs of teachers, would also offer additional insight into the amount of practice required for cognitive change. Additionally, conducting a six-month follow-up may help answer questions related to level of teacher engagement, consultation duration and degree of support needed for teachers to maintain cognitive-behavioral change.

As advancements in technology occur, a redesigned online group RE-SBC model may be warranted. School counselor researchers should explore additional ways to design online RE-SBC models that are supportive and accommodating of teachers. For example, the inclusion of synchronous sessions within an asynchronous online design is worth exploring. Researchers also may want to explore synchronous, online models of consultation using technology such as webinars or three-dimensional, virtual worlds. YouTube, in particular, seems to be a useful online tool for improving online offerings for school counselors and teachers. The Halo Rational Emotive Therapy (2011) video, for example, shows the creative possibilities offered by YouTube. Apps for cell phones and tablet computing devices offer seemingly endless possibilities for convenient, online consultation and collaboration strategies for school counselors. Additionally, a modification of the face-to-face consultation to include online components may be a viable option and worth studying.

Advancements in the preparation of school counselors also may influence and increase the effectiveness of school counselors’ use of technology for RE-SBC. Counselor education programs need to challenge and support graduate students in creative and inventive applications of technology in the practice of school counseling. Gerler’s (1995) early challenge for school counselors to explore the edges of technology, and then later challenges by Hayden, Poynton, and Sabella (2008) for using technology to apply the ASCA National Model offer hope that the preparation of school counselors will improve online and other technological strategies in school counseling, including the use of technology for RE-SB consultation.

School counselor researchers also may want to explore the effects of RE-SB group consultation on various critical school issues. RE-SB group consultation may impact factors that influence student success, including academic achievement, bullying, disciplinary problems, motivation and teacher burnout. Warren and Stewart (2012) also suggested cognitive behavioral approaches to school counselor-teacher consultation may be effective in reducing student dropout rates. Research in these areas will be invaluable as school counselors continue to refine their roles as consultants.

In conclusion, the findings of this study provide direction for school counselors providing consultation. Cognitive behavioral consultation, such as the RE-SBC face-to-face group approach, appears to influence the irrational beliefs of elementary school teachers. Specifically, decreases in self-downing attitudes and authoritarian attitudes toward students were noted. While teacher efficacy beliefs, a predictor of student achievement, were not found, the decrease in irrational beliefs alone is important and potentially a factor in promoting student success. The online group RE-SBC effort was largely ineffective in reducing irrational beliefs or increasing efficacy beliefs. The online model of consultation should be carefully considered before implementation and deemed useless pending a significant redesign. However, both formats of RE-SBC demonstrate leadership, advocacy for the well-being of teachers and students, and collaboration among stakeholders— qualities mandatory for school counselors wishing to effect systemic change. It is hoped that this study will encourage school counselors to become familiar with and implement models of consultation that promote positive mental health of teachers and have the potential to support the educational success of students and parents.

References

American School Counselor Association. (2012). The ASCA national model: A framework for school counseling programs (3rd ed.). Alexandria, VA: Author.

Baker, S. B., & Gerler, E. R. (2008). School counseling for the twenty-first century (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Merrill.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-Efficacy the exercise of control. New York, NY: Freeman.

Bernard, M. E. (1990). Taking the stress out of teaching. Melbourne, Vic: Collins-Dove.

Bernard, M. E., & DiGiuseppe, R. (1994). Rational-emotive consultation in applied settings.Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Bora, C., Bernard, M. E., Trip, S., Decsei-Radu, A., & Chereji, S. (2009). Teacher irrational belief scale—preliminary norms for Romanian population. Journal of Cognitive and Behavioral Psychotherapies, 9, 211–220.

Bridges, K. R., & Sanderman, R. (2002). The Irrational Beliefs Inventory: Cross cultural comparisons between American and Dutch samples. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy, 20, 65–71. doi: 10.1023/A:1015133004916

Brown, D., & Schulte, A. C. (1987). A social learning model of consultation. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 18, 283–287. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.18.3.283

Brown, D., Pryzwansky, W. B., & Shulte, A. C. (2011). Psychological consultation and collaboration: Introduction to theory and practice (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Caplan, G. (1970). The theory and practice of mental health consultation. New York, NY: Basic.