Aug 20, 2021 | Volume 11 - Issue 3

Louisa L. Foss-Kelly, Margaret M. Generali, Michael J. Crowley

The consequences of adolescent drug and alcohol use may be serious and far-reaching, forecasting problematic use or addictive behaviors into adulthood. School counselors are particularly well suited to understand the needs of the school community and to seamlessly deliver sustainable substance use prevention. This pilot study with 46 ninth-grade students investigates the impact of the Making Choices and Reducing Risk (MCARR) program, a drug and alcohol use prevention program for the school setting. The MCARR curriculum addresses general knowledge of substances and their related risks, methods for evaluating risk, and skills for avoiding or coping with drug and alcohol use. Using a motivational interviewing framework, MCARR empowers students to choose freely how they wish to behave in relation to drugs and alcohol and to contribute to the health of others in the school community. The authors hypothesized that the implementation of the MCARR curriculum would influence student attitudes, knowledge, and use of substances. Results suggest that the MCARR had a beneficial impact on student attitudes and knowledge. Further, no appreciable increases in substance use during the program were observed. Initial results point to the promise of program feasibility and further research with larger samples including assessment of longitudinal impact.

Keywords: MCARR, school counselors, drug and alcohol use, substance use prevention, motivational interviewing

Adolescent substance use continues to wreak havoc in the United States, resulting in tragic consequences for adolescents, their families, and communities. Although some substances of abuse and modes of delivery have faded in prominence, others have taken their place. For instance, data from the National Institute on Drug Abuse’s Monitoring the Future Survey reflect an alarming rise in e-cigarette use, which may predict an easier transition to combustible cigarettes and cause serious lung injuries (Johnston et al., 2020; Singh et al., 2020). Use of illicit drugs among adolescents is down, yet cannabis use has increased among younger adolescents to levels that the Food and Drug Administration has described as epidemic (Johnston et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020). Reports have shown a rise in 30-day marijuana vaping, a common metric for assessing recent use, which has doubled or tripled among eighth, 10th, and 12th graders (Johnston et al., 2020). Concerns remain that early initiation of drug use may further fuel the United States’ ongoing opioid epidemic (D. A. Clark et al., 2020; D. J. Clark & Schumacher, 2017). Historically, alcohol has been the most prominent substance of abuse among adolescents (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2018); however, binge alcohol use, defined as more than five drinks on a single occasion, has been declining since the 1970s (Johnston et al., 2020). Regardless, alcohol use and its related risks, such as homicide, suicide, and motor vehicle crashes, continue to be a significant problem for youth (Hadland, 2019; Lee et al., 2018).

Among adolescent risk-taking behaviors, substance use is particularly concerning because of potential impacts on the developing brain (Jordan & Andersen, 2017; Renard et al., 2016). Adolescence offers a “window of opportunity” for the establishment of neural pathways that may protect against the development of drug and alcohol use problems (Whyte et al., 2018). Brain structure may impact function in the areas of working memory, attention, and cognitive and social skill development in adolescence (Fuhrmann et al., 2015; Randolph et al., 2013). The developmental tasks of adolescence, such as identity formation, social connectedness, and patterns of interpersonal relatedness, may also be negatively impacted by substance use (Finkeldey et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2018). Incidents of adolescent intoxication may lead to early sexual debut, high-risk sexual activity, physical altercations, or other regrettable behavior (Clark et al., 2020). Moreover, drug use has consistently been linked to depression, anxiety, and poor school performance (e.g., D’Amico et al., 2016; M. S. Dunbar et al., 2017; Ohannessian, 2014). Suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury have also been associated with substance use (e.g., Carretta et al., 2018; Gobbi et al., 2019). In a study of 4,800 adolescents, illicit drug use was more strongly associated with suicidal behavior than other high-risk behaviors (Ammerman et al., 2018). The risks of adolescent drug and other substance use are sweeping, significant, and important for informing prevention efforts.

Early identification and intervention for adolescents is critical for preventing later substance use disorders and staving off this public health problem (Levy et al., 2016). In 2011, of young adults aged 18–30 admitted for substance use disorder treatment, 74% initiated use at age 17 or younger (SAMHSA, 2014). Research suggests that the increase of lifetime problem alcohol use increases by a factor of four when adolescents drink prior to age 15, compared to those who drink prior to age 20 (Kuperman et al., 2013). The current literature identifies a clear relationship between early alcohol and marijuana use and future patterns of prescription opioid abuse (B. R. Harris, 2016). A recent study of over 1,300 adolescents found that those who screened positive for highest risk in a simple 2-question assessment were shown to have a higher number of drinking days and to be at higher risk for alcohol use disorder 3 years later (Linakis, 2019).

School Personnel as Frontline Responders to Adolescent Substance Use Risk

School personnel and the school community have important roles to play in promoting mental health and preventing substance use among students (E. T. Dunbar et al., 2019; Eschenbeck et al., 2019; Lintz et al., 2019). School-based services may range from prevention to treatment, with efficacious results demonstrated using motivational interviewing and other evidence-based approaches (Winters et al., 2012). A number of prevention programs implemented by school leaders or trained youth facilitators have demonstrated efficacy, including Youth to Youth (Wade-Mdivanian et al., 2016), an empowerment-focused, positive youth development approach for ages 13–17 in a 4-day summer conference format. Another is Refuse, Remove, Reasons (RRR; Mogro-Wilson et al., 2017), a 5-session curriculum for ages 13–17 delivered in health classrooms by clinical service providers from the community. The RRR involves caregivers and uniquely focuses on mutual aid between students.

The keepin’ it R.E.A.L. program (Hecht et al., 2003), designed for younger adolescents, Grades 6–9, involves urban or rural culturally grounded curricula focused on social norms and networking to make behavior change and has been adopted by the national Drug Abuse Resistance Education (D.A.R.E.) program. The Life Skills Training program (Botvin & Griffin, 2004), designed for middle school students, relies on cognitive behavioral principles to help students develop self-management and social skills. Also designed for middle school students, the All Stars curriculum (McNeal et al., 2004), emphasizes social skills, social norms, and debunking inaccurate beliefs about adolescent substance use, violence, and early sexual debut. All Stars uses 22 sessions, with some groups outside of class and in a one-on-one meeting format. Each of the programs described here has contributed to the efforts to prevent drug and alcohol abuse among young people; however, none of these offer a school counselor–implemented classroom guidance curriculum specifically designed for middle adolescence, including students aged 14–17 years.

The Role of School Counselors

As stable members of the school community, school counselors hold knowledge of their students and the culture of the school and surrounding community, allowing for a seamless response to student needs. The schoolwide multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) model used to prevent and respond to academic and behavioral difficulties in children provides a structure for delivering prevention in comprehensive school counseling services (Pullen et al., 2019). MTSS utilizes student assessment for the development of tiers of intervention or support to address identified student needs in comprehensive school counseling services (Ziomek-Daigle, 2016). MTSS defines a Tier 1 intervention as primary prevention and includes evidence-based programming for all students. These interventions are used to support student knowledge, skill acquisition, and healthy decision-making and are appropriate for addressing conflict resolution, nutrition and health, and substance use.

The comprehensive school counseling model provides a sound means for delivering substance use prevention interventions. Classroom guidance education, a key responsibility of school counselors, provides an ideal opportunity to implement primary prevention of substance use for all students. However, to date no comprehensive substance use prevention program has focused specifically on delivery by school counselors.

The MCARR Program

Making Choices and Reducing Risk (MCARR) is a school counseling–based program for addressing substance use among adolescents. MCARR utilizes a structured classroom educational program. The program is implemented throughout the academic year as a Tier 1 schoolwide approach with ninth graders in a classroom setting (Ziomek-Daigle, 2016). The program involves meeting once per month to deliver psychoeducation and to engage in reflective and team-oriented learning experiences as part of a health education or related class. MCARR is a naturally sustainable intervention based on school community concepts and highly effective adolescent counseling interventions, described below.

Motivational Interviewing

The MCARR is based on motivational interviewing (MI) and risk reduction principles, both of which are well-established approaches in clinical settings (e.g., Cushing et al., 2014; DiClemente et al., 2017) and in schools (Rollnick et al., 2016). MI focuses primarily on the decision-making process, including resolving ambivalence about change and respecting the client’s autonomy to make their own choices (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). MI has been described as more of a philosophy or method of communication rather than a set of specific techniques. Alongside the Rogerian value of respect, MI offers a form of freedom by providing a validating, encouraging, and safe space to explore one’s identity and learn to make adaptive life choices. Other MI concepts include developing and amplifying discrepancies between one’s current behavior and desired behavior. MI also calls counselors to “roll with resistance” when clients verbalize a lack of desire to change or refusal to change or make healthy choices (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). Rolling with resistance is particularly helpful for adults working with adolescents familiar with authority figure conflict. These adults may quickly slide into an authoritarian tug-of-war to win the adolescent over to behaving in a certain way, inadvertently causing even more resistance. MI may be ideal for supporting adolescents who yearn for personal freedom and the right to make their own choices (Naar-King & Suarez, 2011).

Risk Reduction

Risk reduction is a widely used public health concept in drug and alcohol treatment, especially in terms of relapse prevention (Hendershot et al., 2011). Risk reduction is not directed at abstinence—rather it aims to help those who use alcohol or drugs to engage in use at a lower risk level. The concept of risk reduction is a response to data suggesting that abstinence-only approaches may not be effective for adolescents (Blackman et al., 2018). There is arguably no acceptably low risk level for adolescents. However, when used as a complement to MI, risk reduction ideas can be used to demonstrate that the ultimate decision to use can only be made by the adolescent. Instead of fighting against the developmental task of individuation, this approach could allow adolescents to freely choose whether or not to use and begin to consider future levels of substance use as an adult.

Evaluating Consequences: The CRAFFT

The CRAFFT (Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Friends, and Trouble) is a simple screening instrument incorporated into MCARR to assess substance use consequences and identify problem substance use (Knight, 2016; Knight et al., 1999). The CRAFFT 2.0 instrument is composed of six questions related to use of drugs and alcohol in the prior year, in various situations such as use in motor vehicles, use to relax or when alone, problems with memory related to intoxication, problems with friends, and violations resulting in trouble with school or legal entities. The MCARR curriculum encourages students to consider substance use situations presented on the CRAFFT not to screen peers, but rather as “red flags” to inform healthier decision-making and action.

Neurobiological Education for Risk Literacy

In the MCARR program, students learn about the neurological and physiological impacts of substance abuse in adolescence, including neural plasticity and the functional and structural changes that may permanently affect working memory, attention, and other processes in the developing brain (Fuhrmann et al., 2015). A meta-analytic study by Day and colleagues (2015) suggested that alcohol use can lead to problems with executive functioning, including attention and mental flexibility, as well as mechanisms of self-control. Some drinking and drug use behaviors may be associated with the development of mood and anxiety-related problems (Pedrelli et al., 2016). In addition to this information, MCARR also presents the physiological impact of alcohol and specific drugs, including fatigue, muscle weakness, and damage to organs. MCARR applies these concepts to the daily routine of an adolescent, including specific examples of how these changes may impact athletic performance, academic performance, or social interactions. This information may inform decision-making and contribute to risk literacy, or the ability to consider, interpret, and act on accurate information to make decisions about whether one will engage in substance use (Nagy et al., 2017).

Refusal Skills

Adolescent expectations about the positive or negative effects of substance use may be an important factor in prevention and refusal skills (Lee et al., 2020). For instance, cannabis use is less likely when adolescents perceive it as riskier (Miech et al., 2017). Knowledge about the various impacts of drugs and alcohol have been correlated with the development of beliefs about use, including social aspects, physiological aspects, and general expectancies of use (Zucker et al., 2008). Attitudes about drugs and alcohol and their risks appear to be an important part of effective prevention efforts (Miech et al., 2017; Stephens et al., 2009). For these reasons, the development of healthy attitudes about drug and alcohol use becomes an important life task (Schulenberg & Maggs, 2002).

Peer Influence

Understanding the power of peer influence in adolescent substance use (Henneberger et al., 2019), the MCARR approach also employs the social context of the caring school community to support primary prevention efforts and promote overall student wellness. It is well documented that social pressures are particularly heightened during adolescence, when the desire to affiliate with peers and find acceptance within a peer group is highly valued (Trucco et al., 2011). During the adolescent developmental period, decision-making reference points are more likely to shift away from family and important adults and toward peer groups. According to normative social behavior theory, perceptions that most of one’s peers use drugs and alcohol may increase the likelihood of one’s own substance use (Rimal & Real, 2005). Students often overestimate the frequency and level of use of alcohol and other substances by their peers, resulting in increased likelihood of earlier experimentation (Prestwich et al., 2016). Community-building efforts have the potential to promote a climate wherein students are aware of the risks related to substance use and support positive decision-making among their peers. In this way, students can learn to advocate for others as well as themselves.

Coping and Self-Regulation

The MCARR program also emphasizes coping and emotion regulation skills, both of which are associated with decreased risk-taking behaviors among adolescents (Wills et al., 2016). Skills for coping with stress have been shown to impact future substance use (Zucker et al., 2008). The development of coping skills and substance use knowledge is combined to support informed choices and reduced risk throughout adolescence. Additionally, the MCARR curriculum includes skill-building instruction and practice on drug refusal skills, as these skills have been shown to increase self-efficacy for resisting use (Karatay & Baş, 2017). To support decision-making, students are taught how to analyze and cope with the increasing prevalence of marketing messages in video and social media. These media messages have been shown to significantly impact adolescent perceptions of substance use, resulting in calls for educational interventions to help students cope with messages that encourage substance use (Romer & Moreno, 2017). Ideally, group norms that encourage emotional well-being and self-care may facilitate a student’s receptivity to healthy messages about the risks of drug and alcohol use and may help students make choices accordingly.

Purpose of the Present Study

The purpose of this pilot study was to examine the feasibility of a primary prevention intervention delivered by school counselors targeting decision-making and attitudes around substance use in a Northeastern urban high school with ninth-grade students. We posed the following questions: First, does the MCARR program impact student attitudes and knowledge related to substance use, including perceived risk and readiness to change? Second, does the MCARR program impact substance use behaviors? Using research and literature cited above, we hypothesized that the implementation of the MCARR curriculum would influence student attitudes, knowledge, and use of substances as measured by paired-samples t-tests of data gathered prior to and following implementation of the curriculum.

Method

Participants and Sampling Procedures

This study was approved by both the school district and researchers’ university IRB. Participants of this study were 46 ninth-grade students at an urban high school (54.2% female, 45.8% male), ages 13–15 years (M = 14.13, SD = .57), who provided responses before and after participating in the MCARR program. The ethnic background of participants was as follows: 37% Hispanic or Latino, 30.4% African American, 21.7% Caucasian, 6.5% Mixed ethnic background, 2.2% Asian, and 2.2% preferred not to say.

The families of all ninth graders were notified of the MCARR lessons being delivered within their child’s dramatic arts classroom. The MCARR program and study procedures were described in the informed consent letter to parents. Students gave assent to participate by signing an assent form that was both read aloud and provided to each student. Data collection via a survey was explained along with the risks and benefits of study participation. Although this curriculum was approved for all ninth graders at the school, parents were given the option to opt their child out of the survey portion of this lesson. The study survey was given prior to their first lesson, then repeated following their ninth lesson. None of the students or families opted out of the survey portion of the MCARR program.

Measure

The survey we constructed included non-identifying demographic items, 20 Likert-type scale items, and two open-ended questions. The 20 Likert-type scale items included items from the following subscales: Substance Use Days, CRAFFT Items, Readiness to Change, and Attitudes Regarding Riskiness of Substance Use. The following sources of material informed the development of our MCARR survey: the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (Kann et al., 2018); the CRAFFT 2.0 survey (Knight, 2016); Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) screening and interviewing (S. K. Harris et al., 2014); and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism guidelines (NIAAA; 2011).

Substance use was measured by asking participants to retrospectively estimate their drug or alcohol use in the prior 30 days, a time period consistent with national surveys of youth substance use (Zapolski et al., 2017). Then participants completed six items from the CRAFFT 2.0 survey (Knight, 2016). These questions used a yes/no format, each question relating to a letter in the CRAFFT acronym describing situations or circumstances involving drug or alcohol use. Using the 30-day interval, our survey asked participants the following CRAFFT questions: “Have you ever ridden in a CAR driven by someone (including yourself) who was ‘high’ or had been using alcohol or drugs?,” “Do you ever use alcohol or drugs to RELAX, feel better about yourself or fit in?,” “Do you ever use alcohol or drugs while you are by yourself, or ALONE?,” “Do you ever FORGET things you did while using alcohol or drugs?,” “Do your FAMILY or FRIENDS ever tell you that you should cut down on your drinking or drug use?,” and “Have you ever gotten into TROUBLE while you were using alcohol or drugs?” In general, higher scores indicate higher risk for a substance use disorder (Knight, 2016; Knight et al., 2002). The CRAFFT can be used as a self-report screening tool and has been shown to have strong psychometric properties (e.g., Dhalla et al., 2011; Levy et al., 2004). In an early study of 538 participants, the CRAFFT demonstrated sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value in identifying adolescents with substance use problems (Knight et al., 2002). Further, in a study of 4,753 participants, the CRAFFT 2.0 demonstrated strong concurrent and predictive validity (Shenoi et al., 2019).

Readiness to Change items were informed by components of the brief negotiation interview in SBIRT (D’Onofrio et al., 2005; Whittle et al., 2015) and substance use attitudes items were adapted from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (Kann et al., 2018). Knowledge items were developed based on NIAAA guidelines and norms, such as alcohol volume in various types of beverages and adult low-risk use levels (Alcohol Research Editorial Staff, 2018). Item composition of the four subscales is presented in the supplementary materials (Appendix A).

Procedure

The MCARR is intended to be a universal intervention for students in at least one grade, with ninth graders as the primary target population. MCARR consists of nine learning modules each lasting 1.5 hours, offered once per month in a classroom with 15–20 students in each meeting. The nine modules are: 1) Orientation to the MCARR Program and Community Building, 2) Personal Coping, 3) Attitudes and Messages About Use, 4) Alcohol, 5) Community Partners, 6) Assumptions and Low-Risk Limits, 7) Cannabis, Nicotine, and E-Cigarettes, 8) Opioids and Cocaine, and 9) Review: Decisions. Each module, including the learning objectives and a summary of activities, is provided in Appendix B.

The education curriculum (MCARR) was delivered each month within the dramatic arts classroom at the school. School counselors delivered the curriculum via overhead slides and brief videos, with related reflection and application activities throughout. Each lesson closed with an exit slip used to support and monitor lessons learned that day. The exit slip helped remind students of key concepts in the lesson and gave counselors a sense of the relevance of the lesson and the content retained. In this way, the school counselor could address confusing concepts in the following lesson as needed and continuously improve the program. The survey was administered via computer immediately preceding the presentation of the first module and at the conclusion of the last module.

Results

Descriptive statistics for major study variables are provided in Table 1. Data reported by participants on each of the four scales used in the study were evaluated by way of paired-samples t-tests. The first research question explored the impact of the MCARR curriculum on substance use attitudes and knowledge. We observed significant increase in readiness to change, t(45) = −3.70, p < .001, and a significant increase in knowledge and perception about the riskiness of substance use, t(45) = −4.91, p < .001. The second research question compared student self-reported substance use pre- and post-intervention. Notably, we observed no significant change in substance use days. The absence of significant increases in use may be important during an adolescent period when experimentation with substance use typically increases. However, CRAFFT scores did increase from pre- to post-intervention: t(45) = −2.41, p = .020. We further explored significant increases in the CRAFFT at both the participant level and the item level (see Table 2). Individual CRAFFT items data revealed clear differences in relative impact of each item, with the motor vehicle item “Have you ever ridden in a CAR driven by someone (including yourself) who was ‘high’ or had been using alcohol or drugs?” presenting prominently with the greatest increase in student endorsement (3 at pre- to 12 at post-intervention). The Relax item remained the same (2 at both pre- and post). There was an increase in reported use of substances while Alone (1 to 4), and a slight increase in scores related to Family/Friends (0 to 1), Forgetting (0 to 3), and Trouble (0 to 1). During the course of the study, students with a total CRAFFT items score of 2 or higher, the established CRAFFT 2.0 threshold for suggesting higher risk (Shenoi et al., 2019), rose from 1 participant to 7 participants (N = 46). These results appear to be linked to the motor vehicle item in the CRAFFT, which could point to a potential refinement of MCARR, discussed below. The design of this study does not permit these patterns to be conclusively linked with participation in the MCARR program; however, our data provide promising preliminary evidence for the effectiveness of the MCARR curriculum for targeting attitudes around substance use and readiness for behavior change.

Discussion

In this pilot study, we show the feasibility of the MCARR program delivered by school counselors to ninth-grade students in an urban setting. This primary prevention curriculum was particularly well-suited for universal implementation in the classroom setting. Promising results included significant increases in healthy attitudes about substances, which are important in helping prevent future substance use problems (Nagy et al., 2017). Pre- and post-CRAFFT data showed a slight increase in risky use, with a clear increase in students riding in a car with a person who had been using substances. It should be noted that participants spending more time with others who use while in motor vehicles, not the student’s own use per se, appears to have contributed substantially to the rise in overall CRAFFT scores in this particular study. In fact, because we did not see an appreciable change in self-reported substance use from pre- to post-intervention, which remained low, we believe the uptick in the CRAFFT motor vehicle item does not reflect the adolescent reporting on their own use in a car, but rather an increase in riding with others who are under the influence of substances. This finding has significance for future curriculum development, which may increase content related to managing situations involving substance use and motor vehicles.

Table 1

Means and Standard Deviations of Major Study Variables

| |

Pre-Assessment |

Post-Assessment |

|

| |

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

t |

p |

| Substance Use Days |

0.58 |

3.04 |

0.59 |

2.21 |

0.09 |

.930 |

| CRAFFT Items |

0.15 |

0.52 |

0.52 |

1.03 |

−2.41 |

.020 |

| Readiness to Change |

12.10 |

7.84 |

16.50 |

7.85 |

−3.70 |

< .001 |

| Attitudes Regarding Riskiness of Substance Use |

14.33 |

2.87 |

16.65 |

2.80 |

−4.91 |

< .001 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note. Maximum score for Substance Use Days: 30, CRAFFT Items: 6, Readiness to Change: 24, and Attitudes

Regarding Riskiness of Substance Use: 18. No significant changes were found in substance use days.

Significance was also found in increased readiness for change among those reporting current substance use, perhaps reflecting the utility of offering decisional freedom during a time associated with increasing ambivalence about the choice to initiate drug and alcohol use (Hohman et al., 2014). We did not observe appreciable increases in substance use or abuse across the length of the program, which is noteworthy, as the adolescent years may commonly be a time of increasing substance experimentation and use (Johnston et al., 2020).

Adolescent drug and alcohol use continues to cause ongoing, intractable public health problems (Whyte et al., 2018). As established members of the school community network, school counselors are ideally positioned to play an important role in preventing and reducing drug and alcohol use and other mental health problems among adolescents (Fisher & Harrison, 2018; Haskins, 2012). Their unique integrated role in the school and in the students’ school life offers background knowledge of student experience, positive relational influence, and access to school and community resources when support is needed. Moreover, a program such as MCARR, which aligns with the roles of school personnel such as the school counselor, could lead to a sustainable approach for mitigating teen substance use. The spirit of MI, allowing individuals to make life choices freely, is a sound approach to counseling adolescents and lends itself well to school counseling interventions and changes in attitudes (Naar-King & Suarez, 2011). Further, the MCARR curriculum may increase general knowledge of drugs and alcohol and related risk literacy, which likely contributes to delaying drug and alcohol use until adulthood (Kuperman et al., 2013). Consistent with prior research, the MCARR may effectively use student connections and interaction to teach skills for coping with challenges related to drug and alcohol use (Henneberger et al., 2019).

Table 2

Pre- and Post-MCARR CRAFFT Endorsement by Item and Total Score

| CRAFFT Individual Items Endorsed |

|

Pre |

Post |

1. Have you ever ridden in a car driven by someone (including yourself) who

was “high” or had been using alcohol or drugs? |

no |

43 |

34 |

| yes |

3 |

12 |

| 2. Do you ever use alcohol or drugs to relax, feel better about yourself, or fit in? |

no |

44 |

44 |

| yes |

2 |

2 |

| 3. Do you ever use alcohol or drugs while you are by yourself, or alone? |

no |

45 |

42 |

| yes |

1 |

4 |

| 4. Do you ever forget things you did while using alcohol or drugs?

|

no |

46 |

43 |

| yes |

0 |

3 |

5. Do your family or friends ever tell you that you should cut down on your

drinking or drug use? |

no |

46 |

45 |

| yes |

0 |

1 |

| 6. Have you ever gotten into trouble while using alcohol or drugs? |

no |

46 |

45 |

| |

yes |

0 |

1 |

| Student CRAFFT Total Scoresa |

Score |

Pre |

Post |

| |

0 |

41 |

33 |

| |

1 |

4 |

6 |

| |

2 |

0 |

5 |

| Number of items endorsed “yes” |

3 |

1 |

1 |

| |

4 |

0 |

0 |

| |

5 |

0 |

1 |

| |

6 |

0 |

0 |

a This portion of the table shows the number of students endorsing 0–6 items on the CRAFFT survey. Students with higher-risk scores (total score ≥ 2) changed from 1 student at pre to 7 students at post.

Study Limitations

Although an important first step in developing and evaluating a primary prevention curriculum for school personnel, this pilot study has limitations worth noting. First, this is an open trial. Thus, without a matched control group or an active control group in the context of an experiment, we cannot make strong causal inferences about the impact of our intervention on youth attitudes and readiness for change around substance use. Second, this was a small sample study. A larger sample would more strongly speak to the robustness of the results we report here. Third, the incorporation of more comprehensive substance use instruments into the survey would improve the strength of inferences about the impact of MCARR on substance use behavior. Fourth, the assessment of readiness to change was only applicable to students self-reporting substance use. Future studies may focus on readiness to change among all participants, regardless of substance use self-assessment. In addition, in spite of the specificity of the curriculum, it is possible that the methods of content delivery and program facilitation were impacted by the personal style or characteristics unique to the instructor. These factors could be measured in future work. Lastly, we did not include a follow-up assessment that could speak to the robustness of our observed effects and longer term impact on substance use as students move through their high school years and beyond.

Future Directions

Research is needed to establish evidence to support school interventions such as the MCARR. Future research may support the efficacy of the MCARR through measures of substance use knowledge, risk assessment evaluation competencies, and attitudes about substance use. Longitudinal studies may explore how the MCARR impacts students’ future drug and alcohol use, and research should also explore the relevance of the MCARR for students of different ages, in a variety of school settings, across a diverse range of communities. Future research should focus on the feasibility of this curriculum in online learning environments, including possible delivery adaptations and content considerations. Collaboration with school staff, health educators, and other members of the school community could improve any impact offered by the MCARR. Using school counselors, the MCARR curriculum offers promise in mitigating drug and alcohol use, heading off problematic use, and encouraging students to intentionally reflect on their choices. For the longer term, we hope that a program such as the MCARR could be sustainable, drawing on the roles that counselors already fill within schools and with bridges to counselor education programs, where new school counselors enter the workforce with the MCARR program on board. Problematic substance use continues to plague our youth. We hope that the MCARR, realized through school counselors and other school professionals, can address an important gap via a systemic approach to mitigating youth substance use risk. For the future, we are planning a larger, multi-school study that addresses the limitations just noted and a deeper phenotyping of student characteristics and assessment of processes that may affect the potency of our program (e.g., student relationship with school, peer and parental attitudes about substance use).

In conclusion, with MCARR we provide the profession with a promising primary preventive school-based approach for reducing adolescent substance use behaviors. MCARR is the first program designed specifically to harness the professional strengths of school counselors, with findings in an open trial suggesting impacts on student attitudes and knowledge related to substance use including perceived risk and readiness to change, but without appreciable increases in substance use during a high-risk period. Future work in a randomized trial and follow-up across the high school years will further evaluate MCARR impacts and sustainability in the school milieu.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Alcohol Research Editorial Staff. (2018). Drinking patterns and their definitions. Alcohol Research, 39(1), 17–18.

Ammerman, B. A., Steinberg, L., & McCloskey, M. S. (2018). Risk-taking behavior and suicidality: The unique role of adolescent drug use. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(1), 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2016.1220313

Blackman, S., Bradley, R., Fagg, M., & Hickmott, N. (2018). Towards ‘sensible’ drug information: Critically exploring drug intersectionalities, ‘Just Say No,’ normalisation and harm reduction. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 25(4), 320–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2017.1397100

Botvin, G. J., & Griffin, K. W. (2004). Life skills training: Empirical findings and future directions. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 25, 211–232. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOPP.0000042391.58573.5b

Carretta, C. M., Burgess, A. W., Dowdell, E. B., & Caldwell, B. A. (2018). Adolescent suicide cases: Toxicology reports and prescription drugs. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 14(7), 552–558.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurpra.2018.05.010

Clark, D. A., Donnellan, M. B., Durbin, C. E., Nuttall, A. K., Hicks, B. M, & Robins, R. W. (2020). Sex, drugs, and early emerging risk: Examining the association between sexual debut and substance use across adolescence. PLoS ONE, 15(2). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0228432

Clark, D. J., & Schumacher, M. A. (2017). America’s opioid epidemic: Supply and demand considerations. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 125(5), 1667–1674. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000002388

Cushing, C. C., Jensen, C. D., Miller, M. B., & Leffingwell, T. R. (2014). Meta-analysis of motivational interviewing for adolescent health behavior: Efficacy beyond substance use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(6), 1212–1218. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036912

D’Amico, E. J., Tucker, J. S., Miles, J. N. V., Ewing, B. A., Shih, R. A., & Pedersen, E. R. (2016). Alcohol and marijuana use trajectories in a diverse longitudinal sample of adolescents: Examining use patterns from age 11 to 17 years. Addiction, 111(10), 1825–1835. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13442

Day, A. M., Kahler, C. W., Ahern, D. C., & Clark, U. S. (2015). Executive functioning in alcohol use studies: A brief review of findings and challenges in assessment. Current Drug Abuse Reviews, 8(1), 26–40. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874473708666150416110515

Dhalla, S., Zumbo, B. D., & Poole, G. (2011). A review of the psychometric properties of the CRAFFT instrument: 1999–2010. Current Drug Abuse Reviews, 4(1), 57–64. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874473711104010057

DiClemente, C. C., Corno, C. M., Graydon, M. M., Wiprovnick, A. E., & Knoblach, D. J. (2017). Motivational interviewing, enhancement, and brief interventions over the last decade: A review of reviews of efficacy and effectiveness. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31(8), 862–887. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000318

D’Onofrio, G., Pantalon, M. V., Degutis, L. C., Fiellin, D. A., & O’Connor, P. G. (2005). Development and implementation of an emergency practitioner-performed brief intervention for hazardous and harmful drinkers in the emergency department. Academic Emergency Medicine, 12(3), 249–256.

https://doi.org/10.1197/j.aem.2004.10.021

Dunbar, E. T., Jr., Nelson, M. D., & Tarabochia, D. S. (2019). Substance use disorders: What school counselors should know. Journal of School Counseling, 17(21), 1–29.

Dunbar, M. S., Tucker, J. S., Ewing, B. A., Pedersen, E. R., Miles, J. N. V., Shih, R. A., & D’Amico, E. J. (2017). Frequency of e-cigarette use, health status, and risk and protective health behaviors in adolescents. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 11(1), 55–62. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000272

Eschenbeck, H., Lehner, L., Hofmann, H., Bauer, S., Becker, K., Diestelkamp, S., Kaess, M., Moessner, M., Rummel-Kluge, C., & Salize, H.-J. (2019). School-based mental health promotion in children and adolescents with StresSOS using online or face-to-face interventions: A study protocol for a randomized controlled trial within the ProHEAD Consortium. Trials, 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-018-3159-5

Finkeldey, J. G., Longmore, M. A., Giordano, P. C., & Manning, W. D. (2020). Identifying as a troublemaker/partier: The influence of parental incarceration and emotional independence. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29, 802–816. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01561-y

Fisher, G. L., & Harrison, T. C. (2018). Substance abuse: Information for school counselors, social workers, therapists, and counselors (6th ed.). Pearson.

Fuhrmann, D., Knoll, L. J., & Blakemore, S.-J. (2015). Adolescence as a sensitive period of brain development. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 19(10), 558–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2015.07.008

Gobbi, G., Atkin, T., Zytynski, T., Wang, S., Askari, S., Boruff, J., Ware, M., Marmorstein, N., Cipriani, A., Dendukuri, N., & Mayo, N. (2019). Association of cannabis use in adolescence and risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidality in young adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(4), 426–434. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.4500

Hadland, S. E. (2019). Epidemiology and historical drug use patterns. In J. W. Welsh & S. E. Hadland (Eds.), Treating adolescent substance use: A clinician’s guide (pp. 3–14). Springer.

Harris, B. R. (2016). Talking about screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for adolescents: An upstream intervention to address the heroin and prescription opioid epidemic. Preventive Medicine, 91, 397–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.08.022

Harris, S. K., Louis-Jacques, J., & Knight, J. R. (2014). Screening and brief intervention for alcohol and other abuse. Adolescent Medicine State of the Art Review, 25(1), 126–156.

Haskins, N. H. (2012). The school counselor’s role with students at-risk for substance abuse. VISTAS 2012, Vol. 1, 1–8. American Counseling Association.

Hecht, M. L., Marsiglia, F. F., Elek, E., Wagstaff, D. A., Kulis, S., Dustman, P., & Miller-Day, M. (2003). Culturally-grounded substance use prevention: An evaluation of the keepin’ it R.E.A.L. curriculum. Prevention Science, 4, 233–248. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026016131401

Hendershot, C. S., Witkiewitz, K., George, W. H., & Marlatt, G. A. (2011). Relapse prevention for addictive behaviors. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 6(17). https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-6-17

Henneberger, A. K., Gest, S. D., & Zadzora, K. M. (2019). Preventing adolescent substance use: A content analysis of peer processes targeted within universal school-based programs. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 40, 213–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-019-00544-5

Hohman, Z. P., Crano, W. D, Siegel, J. T., & Alvaro, E. M. (2014). Attitude ambivalence, friend norms, and adolescent drug use. Prevention Science, 15(1), 65–74.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-013-0368-8

Johnston, L. D., Miech, R. A., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., Schulenberg, J. E., & Patrick, M. E. (2020). Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use: 1975–2019: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan.

Jordan, C. J., & Andersen, S. L. (2017). Sensitive periods of substance abuse: Early risk for the transition to dependence. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 25, 29–44.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2016.10.004

Kann, L., McManus, T., Harris, W. A., Shanklin, S. L., Flint, K. H., Queen, B., Lowry, R., Chyen, D., Whittle, L., Thornton, J., Lim, C., Bradford, D., Yamakawa, Y., Leon, M., Brener, N., & Etheir, K. A. (2018). Morbidity and mortality weekly report: Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2017. Surveillance Summaries, 67(8), 1–114. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6708a1

Karatay, G., & Baş, N. G. (2017). Effects of role-playing scenarios on the self-efficacy of students in resisting against substance addiction: A pilot study. The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing, 54, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/0046958017720624

Knight, J. R. (2016). The CRAFFT interview (version 2.0). Boston Children’s Hospital. https://crafft.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/CRAFFT-2.0_Clinician-Interview.pdf

Knight, J. R., Sherritt, L., Shriter, L. A., Harris, S. K., & Chang, G. (2002). Validity of the CRAFFT substance abuse screening test among adolescent clinic patients. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine, 156(6), 607–614. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.156.6.607

Knight, J. R., Shrier, L. A., Bravender, T. D., Farrell, M., Vander Bilt, J., & Shaffer, H. J. (1999). A new brief screen for adolescent substance abuse. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine, 153(6), 591–596. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.153.6.591

Kuperman, S., Chan, G., Kramer, J. R., Wetherill, L., Bucholz, K. K., Dick, D., Hesselbrock, V., Porjesz, B., Rangaswamy, M., & Schuckit, M. (2013). A model to determine the likely age of an adolescent’s first drink of alcohol. Pediatrics, 131(2), 242–248. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-0880

Lee, C.-K., Corte, C., & Stein, K. F. (2018). Drinker identity: Key risk factor for adolescent alcohol use. Journal of School Health, 88(3), 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12603

Lee, C.-K., Corte, C., Stein, K. F., Feng, J.-Y., & Liao, L.-L. (2020). Alcohol-related cognitive mechanisms underlying adolescent alcohol use and alcohol problems: Outcome expectancy, self-schema, and self-efficacy. Addictive Behaviors, 105, 106349. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106349

Levy, S., Sherritt, L., Harris, S. K., Gates, E. C., Holder, D. W., Kulig, J. W., & Knight, J. R. (2004). Test-retest reliability of adolescents’ self-report of substance use. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 28(8), 1236–1241. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.alc.0000134216.22162.a5

Levy, S. J. L., Williams, J. F., & Committee on Substance Abuse Use and Prevention. (2016). Substance use screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. Pediatrics, 138(1), 143.

http://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1211

Linakis, J. G., Bromberg, J. R., Casper, T. C., Chun, T. H., Mello, M. J., Richards, R., Mull, C. C., Shenoi, R. P., Vance, C., Ahmad, F., Bajaj, L., Brown, K. M., Chernick, L. S., Cohen, D. M., Fein, J., Horeczko, T., Levas, M. N., McAninch, B., Monuteaux, M. C., . . . Dean, J. M. (2019). Predictive validity of a 2-question alcohol screen at 1-, 2-, and 3-year follow-up. Pediatrics, 143(3). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-2001

Lintz, M. J., Thurstone, C., Hull, M., & Ladegard, K. (2019). Development of a school-based substance treatment model. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 28(2), 127–131.

https://doi.org/10.1080/1067828X.2019.1623145

McNeal, R. B., Jr., Hansen, W. B., Harrington, N. G., & Giles, S. M. (2004). How All Stars works: An examination of program effects on mediating variables. Health Education & Behavior, 31(2), 165–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198103259852

Miech, R., Patrick, M. E., O’Malley, P. M., & Johnston, L. D. (2017). E-cigarette use as a predictor of cigarette smoking: Results from a 1-year follow up of a national sample of 12th grade students. Tobacco Control, 26(E2), e106–e111. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053291

Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2013). Motivational interviewing: Helping people change (3rd ed.). Guilford.

Mogro-Wilson, C., Allen, E., & Cavallucci, C. (2017). A brief high school prevention program to decrease alcohol usage and change social norms. Social Work Research, 41(1), 53–62.

https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/svw023

Naar-King, S., & Suarez, M. (2011). Motivational interviewing with adolescents and young adults. Guilford.

Nagy, E., Verres, R., & Grevenstein, D. (2017). Risk competence in dealing with alcohol and other drugs in adolescence. Substance Use & Misuse, 52(14), 1892–1909. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2017.1318149

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2011). Alcohol screening and brief intervention for youth: A practitioner’s guide. www.niaaa.nih.gov/YouthGuide

Ohannessian, C. M. (2014). Anxiety and substance use during adolescence. Substance Abuse, 35(4), 418–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2014.953663

Pedrelli, P., Shapero, B., Archibald, A., & Dale, C. (2016). Alcohol use and depression during adolescence and young adulthood: A summary and interpretation of mixed findings. Current Addiction Reports, 3(1), 91–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-016-0084-0

Prestwich, A., Kellar, I., Conner, M., Lawton, R., Gardner, P., & Turgut, L. (2016). Does changing social influence engender changes in alcohol intake? A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(10), 845–860. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000112

Pullen, P. C., van Dijk, W., Gonsalves, V. E., Lane, H. B., & Ashworth, K. E. (2019). Response to intervention and multi-tiered systems of support: How do they differ and how are they the same, if at all? In P. C. Pullen & M. J. Kennedy (Eds.), Handbook of response to intervention and multi-tiered systems of support (pp. 5–10). Routledge.

Randolph, K., Turull, P., Margolis, A., & Tau, G. (2013). Cannabis and cognitive systems in adolescents. Adolescent Psychiatry, 3(2), 135–147. https://doi.org/10.2174/2210676611303020004

Renard, J., Vitalis, T., Rame, M., Krebs, M.-O., Lenkei, Z., Le Pen, G., & Jay, T. M. (2016). Chronic cannabinoid exposure during adolescence leads to long-term structural and functional changes in the prefrontal cortex. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 26(1), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.11.005

Rimal, R. N., & Real, K. (2005). How behaviors are influenced by perceived norms: A test of the theory of normative social behavior. Communication Research, 32(3), 389–414. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650205275385

Rollnick, S., Kaplan, S. G., & Rutschman, R. (2016). Motivational interviewing in schools: Conversations to improve behavior and learning. Guilford.

Romer, D., & Moreno, M. (2017). Digital media and risks for adolescent substance abuse and problematic gambling. Pediatrics, 140(S2), S102–S106. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1758L

Schulenberg, J. E., & Maggs, J. L. (2002). A developmental perspective on alcohol use and heavy drinking during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 14, 54–70. http://doi.org/10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.54

Shenoi, R. P., Linakis, J. G., Bromberg, J. R., Casper, T. C., Richards, R., Mello, M. J., Chun, T. H., & Spirito, A. (2019). Predictive validity of the CRAFFT for substance use disorder, 144(2).

https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-3415

Singh, S., Windle, S. B., Filion, K. B., Thombs, B. D., O’Loughlin, J. L., Grad, R., & Eisenberg, M. J. (2020). E-cigarettes and youth: Patterns of use, potential harms, and recommendations. Preventive Medicine, 133, 106009. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106009

Stephens, P. C., Sloboda, Z., Stephens, R. C., Teasdale, B., Grey, S. F., Hawthorne, R. D., & Williams, J. (2009). Universal school-based substance abuse prevention programs: Modeling targeted mediators and outcomes for adolescent cigarette, alcohol and marijuana use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 102(1–3), 19–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.12.016

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). The Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality (CBHSQ) Report. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26913315

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 18-5068, NSDUH Series H-53). Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHFFR2017/NSDUHFFR2017.pdf

Trucco, E. M., Colder, C. R., & Wieczorek, W. F. (2011). Vulnerability to peer influence: A moderated mediation study of early adolescent alcohol use initiation. Addictive Behaviors, 36(7), 729–736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.02.008

Wade-Mdivanian, R., Anderson-Butcher, D., Newman, T. J., Ruderman, D. E., Smock, J., & Christie, S. (2016). Exploring the long-term impact of a positive youth development-based alcohol, tobacco and other drug prevention program. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education, 60(3), 67–89.

Whittle, A. E., Buckelew, S. M., Satterfield, J. M., Lum, P. J., & O’Sullivan, P. (2015). Addressing adolescent substance use: Teaching Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) and Motivational Interviewing (MI) to residents. Substance Abuse, 36(3), 325–331.

https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2014.965292

Whyte, A. J., Torregrossa, M. M., Barker, J. M., & Gourley, S. L. (2018). Editorial: Long-term consequences of adolescent drug use: Evidence from pre-clinical and clinical models. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 12(83), 6–8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00083

Wills, T. A., Simons, J. S., Sussman, S., & Knight, R. (2016). Emotional self-control and dysregulation: A dual-process analysis of pathways to externalizing/internalizing symptomatology and positive well-being in younger adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 163(S1), S37–S45.

http://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.039

Winters, K. C., Fahnhorst, T., Botzet, A., Lee, S., & Lalone, B. (2012). Brief intervention for drug-abusing adolescents in a school setting: Outcomes and mediating factors. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 42(3), 279–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2011.08.005

Yu, B., Chen, X., Chen, X., & Yan, H. (2020). Marijuana legalization and historical trends in marijuana use among US residents aged 12–25: Results from the 1979–2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. BMC Public Health, 20, 156. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8253-4

Zapolski, T. C. B., Fisher, S., Banks, D. E., Hensel, D. J., & Barnes-Najor, J. (2017). Examining the protective effect of ethnic identity on drug attitudes and use among a diverse youth population. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46, 1702–1715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0605-0

Ziomek-Daigle, J. (Ed.). (2016). School counseling classroom guidance: Prevention, accountability, and outcomes. SAGE.

Zucker, R. A., Donovan, J. E., Masten, A. S., Mattson, M. E., & Moss, H. B. (2008). Early developmental processes and the continuity of risk for underage drinking and problem drinking. Pediatrics, 121(S4), S252–S272. http://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-2243B

Appendix A

Study Subscales

| |

Substance Use

0 days; 1–2 days; 3–5 days; 6–9 days; 10–19 days; 20–29 days; everyday |

| 1 |

In the past 30 days, how many days did you have at least one drink of alcohol? |

| 2 |

In the past 30 days, how many days have you used marijuana? |

| 3 |

In the past 30 days, how many days have you vaped? |

| 4 |

In the past 30 days, how many days have you used tobacco? |

| 5 |

In the past 30 days, how many days have you used prescription drugs in a way other than prescribed? |

| 6 |

In the past 30 days, how many days have you used illegal drugs? |

| 7 |

In the past 30 days, how many days have you used other means to get high? |

| |

Self-Assessment of Use

Yes or No |

| 1 |

Have you ever ridden in a car driven by someone (including yourself) who was “high” or using alcohol or drugs? |

| 2 |

Do you ever use alcohol or drugs to relax, feel better about yourself, or fit in? |

| 3 |

Do you ever use alcohol or drugs while you are by yourself, or alone? |

| 4 |

Do you ever forget things you did while using alcohol or drugs? |

| 5 |

Do your family or friends ever tell you that you should cut down on your drinking or your drug use? |

| 6 |

Have you ever gotten in trouble while you were using alcohol or drugs? |

| 7 |

Are you worried about alcohol or drug abuse among your friends? |

| 8 |

Are you worried about alcohol or drug abuse in your family? |

| |

Attitudes About Use

1 – not very bad for you; 2 – somewhat bad for you; 3 – very bad for you |

| 1 |

How harmful is it to occasionally use alcohol? |

| 2 |

How harmful is it to occasionally use marijuana? |

| 3 |

How harmful is it to occasionally use e-cigs or vaporizers (vaping)? |

| 4 |

How harmful is it to occasionally use tobacco? |

| 5 |

How harmful is it to occasionally use prescription drugs in a way other than prescribed? |

| 6 |

How harmful is it to occasionally use illegal drugs or other ways to get high? |

| |

Readiness to Change |

| |

1 – very likely; 2 – somewhat likely; 3 – somewhat unlikely; 4 – not at all likely |

| |

If you currently use any of the substances below, on a scale of 1–4, how likely is it you would reduce or stop your use? |

| 1 |

Alcohol |

| 2 |

Marijuana |

| 3 |

Vaping |

| 4 |

Tobacco |

| 5 |

Prescription drugs outside of their intended purpose |

| 6 |

Illegal drugs or other ways to get high |

Appendix B

MCARR Curriculum

| MCARR Curriculum |

| Module 1

Orientation to the MCARR Program and Community Building |

| Learning Objectives

At the end of this lesson, students will:

Establish the foundation for the development of community within the classroom group.

Recognize community and civic responsibility within the students’ own school.

Identify the benefits of being a part of a classroom community, including the value in being socially and emotionally supported by others in social environments.

Activities

Psychoeducational lecture.

Team-building activity.

Scenarios: Students consider scenarios of school- and community-related challenges that require social connectedness and help students develop solutions that promote stronger social bonds and support. |

| Module 2

Personal Coping |

| Learning Objectives

At the end of this lesson, students will:

Recall the potential impact of stress and how it may correlate with less healthy choices, such as drug and alcohol use, including warning signals within self and others.

Identify coping skills that can mediate the negative impact of stress on student well-being.

Recognize healthy stress-reducing behaviors already used by students and introduce new coping strategies for managing stress.

Activities

Psychoeducational lecture.

Students practice several basic methods for managing life stress, including diaphragmatic breathing and abbreviated progressive muscle relaxation.

Students identify life stress and coping strategies, with special emphasis on the potential for strategies to reduce the risk of drug and alcohol use. |

| Module 3

Attitudes and Messages About Use |

| Learning Objectives

At the end of this lesson, students will:

1. Recognize the impact of societal attitudes and messages on adolescent substance use.

2. Identify the messages received through the media about substances and the impact on student

decision-making.

3. Define the impact of stress and normalization of common responses to stress.

Activities

Psychoeducational lecture.

Group discussion on a series of photos and statements made by popular musicians. Students assume the perspective of the popular figure, theorize about attitudes they may have had, and evaluate the impact of those attitudes on the lives of those figures.

Students are then challenged to understand other popular culture influences on drug and alcohol use. |

| Module 4

Alcohol |

| Learning Objectives

At the end of this lesson, students will:

1. Identify the physiological and neurological mechanisms of alcohol use and potential harm and

consequences of use.

2. Recognize the impact of alcohol on the body.

3. Define the long-term and short-term physiological and psychosocial effects of alcohol on adolescents.

Activities

Psychoeducational lecture.

Students complete and share a body map worksheet to draw arrows and make linkages of the impact of alcohol use on the adolescent body.

Small groups are given scenarios to consider a day in the life of an alcoholic beverage, from the perspective of the beverage as a character in the scenario.

Students consider elements of the CRAFFT as applied to hypothetical characters involved in their story. |

| Module 5

Community Partners |

| Learning Objectives

At the end of this lesson, students will:

1. Discuss the influence of the community on adolescent drug and alcohol use and methods by which

the community can be used to support those at risk of drug and alcohol problems.

2. Describe the potential benefit or harm of specific peer attitudes and behaviors related to drug and

alcohol use.

3. Recognize signs of possible alcohol or drug use problems among members of the community.

Activities

Psychoeducational lecture

In small groups, students describe a caring school community, followed by a group discussion of harmful and helpful aspects of peer influence.

Exposure to assessment methods such as yellow and red flags that may indicate a substance use problem and the CRAFFT screening tool.

Using role play, students practice methods for communicating with a peer that may minimize defensiveness and identify points of intervention. |

| Module 6

Assumptions and Low-Risk Limits |

| Learning Objectives

At the end of this lesson, students will:

Recognize assumptions made about substance use in school and society.

Classify facts and myths about drug and alcohol use.

Understand risk levels of use for both adolescents and adults and how these may present in various situations.

Activities

Psychoeducational lecture.

Team-building activity, with processing focused on the dynamics of group decision-making.

Myths are presented in a series of group discussion true/false questions about descriptive norms to help students understand that drug or alcohol use is not an inevitable part of the adolescent experience.

Established guidelines for adult limits and moderate use of alcohol are presented, while simultaneously emphasizing that no amount of alcohol represents low or moderate risk for minors.

Case studies are used to apply yellow and red flag warning signs discussed in prior lesson. |

| Module 7

Cannabis, Nicotine, and E-Cigarettes |

| Learning Objectives

At the end of this lesson, students will:

1. Identify a variety of hazards associated with cannabis and nicotine, with special focus on e-cigarettes.

2. Comprehend the physiological and neurological impacts of cannabis and nicotine on adolescents.

3. Describe and practice refusal skills related to cannabis and nicotine.

Activities

Students are provided with an overview of the mechanisms involved in cannabis use and learn about the impact of cannabis on the developing brain, such as learning and memory deficits, loss of motivation, and mood swings.

In the “Whose truth is it, anyway?” discussion, students are given a series of statements and asked to measure the likelihood of the statement’s veracity, depending on the source of the statement and other influencing factors.

After this content, students move around the classroom to find classmates who can answer various questions correctly. |

| Module 8

Opioids and Cocaine |

| Learning Objectives

At the end of this lesson, students will:

Recognize the classes of drugs related to opioids and cocaine and trends in use and abuse of these drugs, including risk of serious injury or death.

Recall facts about physiological and neurological impacts of various forms of opioids and cocaine.

Summarize the dangers of opioid use.

Activities

Psychoeducational lecture.

Video to demonstrate neurological dynamics and physiological mechanisms, including the potential for overdose.

Students brainstorm resources in their school community and receive information on community resources for helping those with addiction, including professional networks, such as counselors and other mental health providers, and informal networks, such as neighborhood and faith leaders.

In dyads, students are asked to role-play skills for persuading a peer or loved one to seek professional help and weigh the pros and cons of these decisions. |

| Module 9

Review: Decisions |

| Learning Objectives

At the end of this lesson, students will:

1. Identify the experiences and information presented throughout the curriculum, with an overarching

theme of decisional balance.

2. Recall key information related to each module.

3. Describe what the curriculum has meant to each student and how they envision the experience

impacting future decisions.

Activities

Students participate in a learning game in which teams compete to give correct answers about key concepts, including facts about the dynamics of problem alcohol and drug use and its consequences and risks.

Students report on identifying and coping with stress, connecting with a caring community, and advocating for their and others’ needs.

Students are reminded of the influence of myths, attitudes, and assumptions on the use of alcohol and drugs and recollect components of the CRAFFT. |

Louisa L. Foss-Kelly, PhD, NCC, ACS, LPC, is a professor at Southern Connecticut State University. Margaret M. Generali, PhD, is a certified school counselor and a professor and department chair at Southern Connecticut State University. Michael J. Crowley, PhD, is a licensed psychologist and an associate professor at Yale University. Correspondence may be addressed to Louisa L. Foss-Kelly, Counseling and School Psychology, Southern Connecticut State University, 501 Crescent St., New Haven, CT 06515, fossl1@southernct.edu.

Feb 26, 2021 | Volume 11 - Issue 1

Diane M. Stutey, Jenny L. Cureton, Kim Severn, Matthew Fink

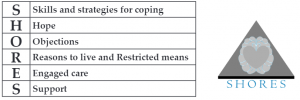

Recently, a mnemonic device, SHORES, was created for counselors to utilize with clients with suicidal ideation. The acronym of SHORES stands for Skills and strategies for coping (S); Hope (H); Objections (O); Reasons to live and Restricted means (R); Engaged care (E); and Support (S). In this manuscript, SHORES is introduced as a way for school counselors to address protective factors against suicide. In addition, the authors review the literature on comprehensive school suicide prevention and suicide protective factors; describe the relevance of a suicide protective factors mnemonic that school counselors can use; and illustrate the mnemonic’s application in classroom guidance, small-group, and individual settings.

Keywords: suicide prevention, protective factors, school counselors, SHORES, mnemonic

Rates of youth suicide have increased tremendously in the last decade. A report by the National Center for Health Statistics in 2019 indicated that suicide rates among American youth ages 10–24 increased 56% from 2007 to 2017, making it the second leading cause of death in this age group; during this same time period, the rate almost tripled for those ages 10–14 (Curtin & Heron, 2019). Additionally, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; 2017) reported that suicide is now the ninth leading cause of death for children ages 5–11.

The suicide rates for children as young as 5 can seem alarming and impact school counselors at all grade levels. Sheftall et al. (2016) stated that children who died by suicide in this younger age range were frequently diagnosed with a mental health disorder. In children, this diagnosis was usually attention deficit disorder with or without hyperactivity, and in young adolescents the diagnosis was most often depression or dysthymia. Researchers have also found that certain risk factors, such as childhood trauma, bullying, and academic pressure, can increase suicidal risk for youth (Cha et al., 2018; Jobes et al., 2019; Lanzillo et al., 2018).

Researchers agree that early prevention and intervention is essential to reduce youth suicides

(Cha et al., 2018; Lanzillo et al., 2018; Sheftall et al., 2016). Similarly, postvention efforts, or crisis response strategies following a student’s suicide, can lessen school suicide contagion and support future prevention efforts (American Foundation for Suicide Prevention [AFSP] et al., 2019). In this article, we review the literature on youth suicide and efforts to address it including leveraging protective factors, and we introduce the relevance of a suicide protective factors mnemonic that school counselors can apply in classroom guidance, small-group, and individual settings (American School Counselor Association [ASCA], 2019).

School Suicide Prevention

Curtin and Heron (2019) called for proactive efforts to help address the rising statistics for youth suicide, and schools are a natural place for prevention, intervention, and postvention to occur. Students spend the majority of their waking hours at school and have frequent contact with teachers, counselors, administrators, and peers. School efforts to address suicide risk must include these stakeholders, as well as parents and community members (Ward & Odegard, 2011).

A suicide prevention effort is a strategy intended to reduce the chance of suicide and/or possible harm caused by suicide (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], Office of the Surgeon General and National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, 2012). Best practice for suicide prevention in schools includes training all stakeholders, including students (Wyman et al., 2010). This training, frequently referred to as gatekeeper training, should include information about suicide warning signs and risk factors, as well as suicide protective factors, such as seeking help and having social connections. The World Health Organization’s (WHO; 2006) booklet for counselors on suicide prevention lists several suicide warning signs, including ones with relevance to school-age youth, such as decreased school achievement, changed sleeping and eating, preoccupation with death, sudden promiscuity, or reprieve from depression (pp. 5–6). Another important component of school suicide prevention is training and practice on how to help a student who exhibits these and/or other suicidal warning signs (AFSP et al., 2019). Institutional efforts, such as forming crisis teams (AFSP et al., 2019), and anti-bullying programs can also contribute to school suicide prevention efforts (HHS, 2012).

Other school prevention efforts involve small-group and whole classroom lessons on resiliency, coping skills, executive functioning skills, and help-seeking behavior (Sheftall et al., 2016). Many programs exist and are beneficial at elementary, middle, and high school levels. The Suicide Prevention Resource Center (SPRC; 2019a) listed many options: Signs of Suicide, More Than Sad, Sources of Strength, and Kognito. Of these examples, only Signs of Suicide contains training for warning signs, suicide risk factors, and suicide protective factors. Some suicide prevention programs are state and population specific, but all include the information needed to help stakeholders to know the risks and signs, and to have a plan on how to help youth with suicidal thoughts. Talking about suicide prevention with all stakeholders promotes increased help-seeking behavior in children and adolescents (Wyman et al., 2010).

School Suicide Intervention

Suicide is an ongoing issue that many school counselors handle via intervention efforts. A suicide intervention effort is a strategy to change the course of an existing circumstance or risk trajectory for suicide (HHS, 2012). School counselors are a natural choice for helping to implement suicide prevention and intervention programs, as they often have training on working with students at risk for suicidal ideation (Gallo, 2018). Additionally, school counselors are ethically responsible to help create a “safe school environment . . . free from abuse, bullying, harassment and other forms of violence” and to “advocate for and collaborate with students to ensure students remain safe at home and at school” (ASCA, 2016, pp. 1, 4). One key component of school suicide intervention is suicide risk assessment. Gallo (2018) researched 200 high school counselors representing 43 states and found that 95% agreed it was their role to assess for suicidal risk, and 50.5% were conducting one or more suicide risk assessments each month. Other aspects of intervention include potential involvement of administrators, parents, and emergency or law enforcement services; referral to outside health care providers; and safety planning, including lethal means counseling (AFSP et al., 2019). School and other counselors are also involved in ongoing check-ins with students, re-entry planning after a mental health crisis, and responses to in-school and out-of-school suicide attempts.

School Suicide Postvention

Suicide postvention involves attending to those “affected in the aftermath of a suicide attempt or suicide death” (HHS, 2012, p. 141). ASCA, in collaboration with AFSP, the Trevor Project, and the National Association of School Psychologists, released the Model School District Policy on Suicide Prevention that outlines policies and practices for districts, schools, and school professionals to protect student health and safety (AFSP et al., 2019). The model policy addresses postvention by summarizing a 7-step action plan involving school counselors and other professionals: 1) get the facts, 2) assess the situation, 3) share information, 4) avoid suicide contagion, 5) initiate support services, 6) develop memorial plans, and 7) postvention as prevention (pp. 11–13). The latest edition of a suicide postvention toolkit for schools (SPRC, 2019a) highlighted counselors’ collaborative work for crisis response and suicide contagion; how they help students with coping and memorialization; and their involvement with community, media, and social media.

Addressing factors that protect against suicide is an important component of school district policies to combat suicide (AFSP et al., 2019) and of comprehensive school suicide prevention (Granello & Zyromski, 2018). Leveraging suicide protective factors is one way for school counselors to fulfill professional obligations and recommendations concerning student suicide risk. What remains unclear from the literature is how school counselors explore and enhance protective factors in their suicide prevention, intervention, and postvention efforts.

Suicide Risk and Protective Factors

The SPRC (2019b) defined suicide risk factors as “characteristics that make it more likely that individuals will consider, attempt, or die by suicide” and protective factors as those which make such events less likely (p. 1). High suicide risk involves a combination of risk factors. Examples of suicide risk factors include a prior attempt, mood disorders, alcohol abuse, and access to lethal means, whereas examples of suicide protective factors include connectedness, health care availability, and coping ability (SPRC, 2019b). Protective factors “are considered insulators against suicide,” which can “counterbalance the extreme stress of life events” (WHO, 2006, p. 3). Both risk and protective factors have varying levels of significance depending on the individual and their community (SPRC, 2019b).

Guidance from multiple sources stresses the salience of incorporating attention to suicide risk and protective factors into school counseling. The AFSP et al. (2019) Model School District Policy on Suicide Prevention notes risk and protective factors as crucial content in staff development and youth suicide prevention programming. In addition to the risk factors named above, the policy names high-risk groups, such as students who are involved in juvenile or child welfare systems; those who have experienced homelessness, bullying, or suicide loss; those who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or questioning; or those who are American Indians/Alaska Natives (AFSP et al., 2019).

School counselors should know suicide protective factors that are specific to school settings and to the ages of students that they serve. The Model School District Policy on Suicide Prevention (AFSP et al., 2019) also highlights the role that accepting parents and positive connections within social institutions can play in a student’s resiliency. Despite suicide prevention policy guidelines, numerous structured programs, and growing research on youth suicide protective factors, very little guidance is offered on practical methods for school counselors to address students’ suicide protective factors. The purpose of this manuscript is to introduce to school counselors a recently published, research-based mnemonic—SHORES (Cureton & Fink, 2019). The acronym of SHORES stands for Skills and strategies for coping (S); Hope (H); Objections (O); Reasons to live and Restricted means (R); Engaged care (E); and Support (S). SHORES equips school counselors with a promising tool to guide suicide prevention, intervention, and postvention via direct and indirect school counseling services.

SHORES

Cureton and Fink (2019) created a mnemonic device called SHORES for counselors to utilize when working with clients. SHORES represents protective factors against suicide and the letters in the acronym were carefully selected based on support in the literature.

Figure 1

Cureton, J. L., & Fink, M. (2019). SHORES: A practical mnemonic for suicide protective factors. Journal of Counseling &