Sep 13, 2024 | Volume 14 - Issue 2

Dax Bevly, Elizabeth A. Prosek

Professional counselors may choose to increase self-awareness and/or engage in self-care through the use of personal therapy. Some counselors may feel reluctant to pursue personal therapy due to stigma related to their professional identity. To date, researchers have paid limited attention to the unique concerns of counselors in personal therapy. The purpose of this descriptive phenomenological study was to explore counselors’ experiences and decision-making in seeking personal therapy. Participants included 13 licensed professional counselors who had attended personal therapy with a licensed mental health professional within the previous 3 years. We identified six emergent themes through adapted classic phenomenological analysis: presenting concerns, therapist attributes, intrapersonal growth, interpersonal growth, therapeutic factors, and challenges. Findings inform mental health professionals and the field about the personal and professional needs of counselors. Limitations and future research directions are discussed.

Keywords: professional counselors, self-awareness, self-care, personal therapy, phenomenological

Self-awareness is a fundamental part of the counseling profession. Not only do professional counselors seek to increase the self-awareness and personal growth of their clients, but counselor educators call upon counselor trainees to increase their own self-awareness before entering the field (Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs [CACREP], 2023, Section 3A11). Additionally, counselor educators often recommend self-growth experiences such as personal counseling to increase counselor trainees’ self-awareness in preparation for professional practice (Remley & Herlihy, 2020). Several scholars define counselor self-awareness as the mindfulness of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in the self and in the counseling relationship (Fulton & Cashwell, 2015; Merriman, 2015; Rosin, 2015). Pompeo and Levitt (2014) asserted that self-awareness parallels awareness of personal values and enables counselors to explore best practices in counseling. However, after training, it becomes less clear how, if at all, counselors access their own counseling for self-growth and self-awareness; therefore, we designed the current study to explore how practicing counselors utilize personal therapy.

Correlates of Self-Awareness Among Counselors

Counselor self-awareness relates to awareness of the counseling relationship, which is helpful to client satisfaction and growth (Pompeo & Levitt, 2014); as such, several researchers have examined the clinical implications of counselor self-awareness, including professional competence, client treatment outcomes, and wellness. For example, Rake and Paley (2009) found that the therapists in their study reported modeling themselves after their own therapist as well as learning about technical aspects of a therapeutic approach. In regard to wellness, Gleason and Hays (2019) found that counselor self-awareness helped identify stressors and needs regarding personal wellness in doctoral-level counselor trainees. Similarly, Merriman (2015) discussed how self-awareness can help prevent burnout or compassion fatigue. Many researchers have investigated the importance of self-awareness as a characteristic of counselors who can competently work with culturally diverse clients (Ivers et al., 2016; Sue et al., 2022). Thus, some evidence of the clinical impact of counselor self-awareness already exists in the literature.

Expanding upon the impacts of self-awareness on the therapeutic relationship, Anderson and Levitt (2015) articulated the importance of self-awareness in how counselors’ social influence impacts the working alliance. Additionally, Tufekcioglu and Muran (2015) described how the working alliance provides a laboratory wherein the client can focus on and more clearly delineate their experience in relation to the therapist’s experience. Thus, the counseling goal of cultivating mindfulness in clients with respect to the details of their own experience involves counselors becoming mindful of the corresponding details of their own experience. Tufekcioglu and Muran argued that every encounter with a client demands the counselor’s self-reflection in the form of greater self-awareness in relation to the working alliance, and maintained that the therapeutic process should involve change for both participants.

Counselors Seeking Mental Health Care

Counselors can gain self-awareness in a variety of ways, including personal therapy. Mearns and Cooper (2017) stated that the term therapy loosely signifies the receiving of mental health services from any mental health professional who holds a license to practice. We use the word therapist in reference to researchers who did not specify the type of mental health professional (e.g., counselor, psychologist, social worker) who provided therapy to the participants in their study. Several scholars have suggested that therapists who participated in their own personal therapy experienced increased professional development as well as positive client outcomes. For example, VanderWal (2015) found that clients of counselor trainees with personal therapy experience demonstrated reduced rates of distress more quickly than clients of counselor trainees without personal therapy experience. Other researchers have noted the impact of therapy on therapists’ personal growth. Although not specific to professional counselors, Moe and Thimm (2021) conducted a systematic review of the literature regarding mental health professionals’ experiences in personal therapy and discovered benefits related to genuineness, empathy, and creation of a working alliance. Outcomes of this previous research support the positive impact of personal therapy for therapists.

Some counselors may seek personal therapy due to mental health concerns. Therefore, it is worth exploring the needs of this unique population. In one study, Orlinsky (2013) reported that therapists’ most frequently cited presenting concerns were resolving personal problems. Additionally, Moore et al. (2020) reported that counselors experienced interpersonal stress as a response to threatening situations in their clinical work and, in order to cope, neglected their own personal needs. Other investigators found a relationship between higher rates of ethical dilemmas in clinical practice and increased stress and burnout among counselors (Mullen et al., 2017). Robino (2019) introduced the concept of global compassion fatigue, a phenomenon wherein counselors experience “extreme preoccupation and tension as a result of concern for those affected by global events without direct exposure to their traumas through clinical intervention” (p. 274). In this conceptual piece, Robino summarized the literature findings on how indirect exposure of distressing events impact the mental well-being of professional helpers and advocated for the role of self-awareness as an important coping skill. Furthermore, Prosek et al. (2013) found that counselor trainees presented with elevated levels of anxiety and depression, providing further evidence that counselors are at risk for mental health concerns related to occupational and personal stressors.

Purpose of the Study

The psychological needs of counselors coupled with the emphasis on gaining self-awareness highlight the necessity for counselors’ personal therapy. Self-awareness is an important component of counselor development due to the personal nature of the profession (Pompeo & Levitt, 2014; Remley & Herlihy, 2020). Personal therapy is one way to enhance counselor self-awareness (Mearns & Cooper, 2017). Additionally, counselors may experience a variety of mental health concerns, including compassion fatigue, interpersonal conflict, depression, and anxiety (Moore et al., 2020; Mullen et al., 2017; Orlinsky, 2013; Prosek et al., 2013; Robino, 2019). Researchers have primarily focused on the perceived outcomes of personal therapy, including personal growth, professional development, and positive client outcomes (Moe & Thimm, 2021; VanderWal, 2015). However, scarce research exists regarding counselors’ decision-making processes in seeking personal therapy. Thus, if counselors could benefit from personal therapy, and if little knowledge exists regarding how counselors decide to seek personal therapy, professional counselors, counselor educators, counselor supervisors, and other mental health providers have limited information regarding how to facilitate that decision-making process.

Researchers employing qualitative investigation typically seek to holistically understand meaning. More specifically, the goal of a phenomenological approach is to capture the experiences and meaning-making from the participants’ perspectives (Creswell & Creswell, 2017). We want to illuminate how professional counselors make meaning of their experiences in personal therapy, as much of the existing literature focuses on trainees, clinical outcomes, or quantitative data. We believe describing the lived experiences, or essence (Moustakas, 1994), of counselors receiving personal therapy may lead to a deeper body of research regarding the perceptions, emotions, and behaviors of this population. The following questions guided our inquiry:

- What contributes to counselors’ decisions to seek personal therapy?

- How do professional counselors make meaning of their experiences in utilizing

personal therapy?

Method

Phenomenologists seek to understand the distinctive characteristics of human behavior and first-person experience (Hays & Singh, 2023). Based on an existentialist research paradigm, we wanted to understand how counselors make meaning of their experiences in personal therapy. Because we aimed to describe the lived experiences of counselors receiving personal therapy, descriptive phenomenology answers the research questions appropriately (Prosek & Gibson, 2021). Consistent with descriptive phenomenology, we used Miles et al.’s (2019) adaptation of classic data analysis, an inductive–deductive approach.

Research Team and Reflexivity

At the time of data collection (pre–COVID pandemic), Dax Bevly, who identifies as a White, Latina cisgender woman in her late 20s, was completing a doctoral degree in counseling. Elizabeth A. Prosek, who identifies as a White, cisgender woman, brought experience in conducting, teaching, and mentoring qualitative research studies. Bevly utilized a research team for data analysis that included four women in their early 20s completing master’s degrees in counseling; three identified as White and one identified as Asian. As instruments in the research themselves, the team needed to embrace their potential influence and impact (Hays & Singh, 2023); therefore, Bevly and Prosek participated in research reflexivity meetings several times during data collection and analysis, where they discussed thoughts and emotions evoked through their participation in the study. Descriptive phenomenology requires researchers to establish epoche, an exchange of assumptions that can be held accountable to bracket or identify throughout the process. Our research team demonstrated epoche by journaling and discussing biases and assumptions regarding the present study throughout the data analysis process. Bevly in particular was especially aware of her own personal biases due to long-term participation in personal therapy, believing it to have highly influenced her personal and professional development in a positive way. Bevly consulted with the research team as we examined experiences, reactions, and any assumptions or biases that could interfere with the coding process during data analysis. The research team members held Bevly accountable for her responses to the research process (Creswell & Creswell, 2017). The four other members of the research team also engaged in the examination of their experiences, reactions, and assumptions or biases during analysis, reporting assumed benefits including increased awareness, higher functioning in relationships, and increased self-esteem. Bevly also utilized the research team for the purpose of engaging in critical discussion during the analysis process in order to develop a trustworthy study. Furthermore, Bevly and Prosek kept a journal in order to document the research team members’ bracketing throughout the study. The journal also noted the connection and validation that Bevly experienced in interviewing participants and the care and mindfulness to not insert her personal experiences, especially regarding the overlapping roles of client and counselor as well as feelings of vulnerability.

Procedure

We obtained IRB approval before participant recruitment. Eligibility for the study included identifying as a licensed professional counselor (LPC) aged 18 or older who utilized counseling services with a licensed mental health therapist either currently or within the previous 3 years (similar criteria to Yaites, 2015). We used purposive sampling to select participants for this phenomenological study (Hays & Singh, 2023), recruiting participants through email, word of mouth, and networking with LPCs in a 50-mile radius of our institution, which is located in a large state in the Southwestern United States. This radius allowed us to intentionally reach more diverse areas of the geographical region. We also recruited participants through personal contacts and professional counseling organizations. Potential participants completed an eligibility online survey via Qualtrics. We contacted them via phone or email to explain the study and confirm their eligibility. We excluded participants who reported holding expired LPC licenses, experienced therapy more than 3 years ago, or described personal therapy from an individual without a license in a mental health profession. We scheduled face-to-face meetings with participants in their professional counseling office at their convenience. Although participants read and acknowledged the informed consent before meeting face-to-face, we readdressed informed consent before proceeding. Bevly conducted and audio recorded 60-minute interviews with each participant. At the conclusion of each interview, Bevly also facilitated a sand tray activity with the participant.

Participants

We recruited participants based on gaining depth with adequate sampling (Prosek & Gibson, 2021). Participants (N = 13) identified mostly as White, cisgender women with an average age of 37.23; see Table 1 for complete demographics. Although we sought to recruit participants with diverse social identities, geographic limitations presented a challenge. Thus, our findings should be interpreted with caution, as the external validity, or generalizability, of the findings to other populations or different contexts is impacted by the limited diversity among our participant demographics. Lastly, we asked participants to choose pseudonyms in an effort to protect their anonymity and confidentiality.

Data Sources

Demographic Form

In order to determine eligibility and collect demographic information, we asked potential participants to complete a Qualtrics survey, an online initial screening tool that included questions about age, gender, racial and ethnic identification, sexual orientation, religious/spiritual identity, number of personal therapy sessions completed, length of time since termination of personal therapy (if applicable), number of years as an LPC, disability status, licensure of therapist, therapist demographic information, and whether or not their counseling training program required personal therapy. The online demographic survey also included information about informed consent and confidentiality. Although it was not required for the study, all participants reported that therapy took place face-to-face.

Table 1

Participants of the Study

| Participant |

Age |

Race/Ethnicity |

Gender |

Religious/Spiritual Affiliation |

Sexual Orientation |

| Alma |

37 |

Latina |

Woman |

Christian |

Heterosexual |

| Amy |

30 |

Latina |

Woman |

Christian |

Heterosexual |

| Ashley |

29 |

Multiracial |

Woman |

Spiritual |

Heterosexual |

| Betty |

55 |

White |

Woman |

None |

Heterosexual |

| Elenore |

30 |

Multiracial |

Woman |

Christian |

Queer |

| Felicity |

44 |

White |

Woman |

Christian |

Heterosexual |

| Jennifer |

40 |

White |

Woman |

Christian |

Heterosexual |

| Liz |

35 |

White |

Woman |

Pagan |

Bisexual |

| Lynn |

48 |

White |

Woman |

Christian |

Heterosexual |

| Michelle |

37 |

White |

Woman |

Christian |

Heterosexual |

| Rose |

30 |

White |

Woman |

Christian |

Heterosexual |

| Sophia |

35 |

White |

Woman |

None |

Heterosexual |

| Thomas |

34 |

White |

Man |

None |

Heterosexual |

Semi-Structured Interview Protocol

We developed a semi-structured interview protocol to guide the interviews. We drafted the questions based on existing literature concerning counselors and personal therapy. The protocol consisted of six open-ended questions and follow-up prompts to understand the experiences of professional counselors who have engaged in personal therapy (see Table 2).

Table 2

Interview Protocol

| Grand tour question: |

| Please tell me about your experience in personal therapy in as much detail as you feel comfortable sharing. |

| Follow-up:

What motivated you to seek personal therapy?

What was happening in your life at the time?

How did you go about selecting a therapist?

Can you tell me about what your internal process (thoughts/feelings) was like leading up to your decision to seek personal therapy? |

| What outcomes did you experience as a result of personal therapy? |

| How, if at all, has personal therapy affected your personal growth? |

| How, if at all, has personal therapy affected your own clinical work? |

| Describe the experience of being both a client and a counselor.

Some literature suggests that counselors feel stigmatized when seeking personal therapy. What do you make of this? How is that similar or different for you? |

| Is there anything else that you would like to share? |

Sand Tray Activity

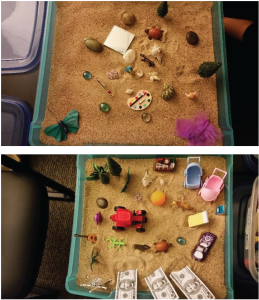

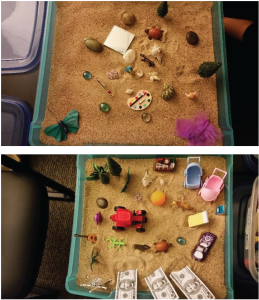

Hays and Singh (2023) stated that “visual methods in general provide participants the opportunity to express themselves in a nonverbal manner that may access deeper aspects of their understanding and/or experience of a phenomenon” (p. 332). After the semi-structured interview, Bevly invited participants to create their personal therapy experience in a sand tray using the figures and materials provided. This method is consistent with Measham and Rousseau (2010), who used sand trays as a method of data collection for understanding the experiences of children with trauma. The sand trays were documented by digital photos (see Appendix), and participants’ discussions about their creations are part of the audio recordings.

Data Analysis

We sent the audio recordings to a professional transcriptionist for transcription of each interview and sand tray session. We reviewed transcripts while listening to the recordings for participants’ tone and to verify accuracy. Consistent with phenomenological procedures, the research team conducted data analysis according to an adaptation of classic analysis (Miles et al., 2019), in which three main activities take place: data reduction, data presentation, and conclusion or verification.

Prior to initial coding, the research team completed several tasks in order to develop the preliminary coding manual: taking notes, summarizing notes, playing with words, and making comparisons (Miles et al., 2019). Taking notes involved the research team as well as Bevly’s own independent analysis of a subset of the first three interviews and sand tray explanation transcripts. We divided the transcripts into 10-line segments and wrote notes in the margins. The research team noted our initial reactions to the material.

Summarizing notes involved discussion between the team regarding our reactions to the interview material. We compared and contrasted our margin notes and highlighted shared perspectives and inconsistent viewpoints in a summary sheet. To play with words, we generated metaphors based on our summary sheet. We developed phrases that represented our interpretation of the participants’ interview responses.

During the making comparisons task, we compared and contrasted the key phrases developed in the previous step and grouped them into categories. The team then facilitated reduction of the data as we combined similar phrases and merged overlapping categories. Hays and Singh (2023) asserted the importance of sieving the data to eliminate redundancy. We continued to merge categories and reformat the category headings. From this process, we developed preliminary themes based on the data. To develop initial codes, we established agreement by independently applying the preliminary codes to a subset of three interviews. The research team met weekly to discuss inconsistencies and points of agreement, adjust the preliminary codes, and reapply them to the data subset. We continued to discuss any remaining discrepancies and concerns until we reached a mean agreement of 86% to 90% (Creswell & Creswell, 2017). We reached a mean agreement of 95.1% and then finalized the codes to use in our coding manual.

It is important to note that the research team sensed that we had reached saturation during the final coding process once we began to read the same comments repeatedly in the participant transcripts. In final coding, we applied the final coding manual to each of the interviews and sand tray explanations. We used the same coding manual for both the interviews and the sand tray explanations. The same research team member coded both the interview and sand tray explanation for the same participant. Bevly coded all 13 interviews and sand tray explanations; all four research team members coded the first three interviews and sand tray explanations. Two research team members coded interviews and sand tray explanations 4 through 8, and the other two research team members coded interviews and sand tray explanations 9 through 13. The research team’s finalized codes included the meaning and depth of participants’ experiences in personal therapy. However, if necessary, researchers could still recode during final coding to maintain consistency with the revised definitions (Creswell & Creswell, 2017). When recoding occurred, we reviewed previously analyzed transcripts with the updated codebook on four occasions. Once we completed final coding, Bevly performed member checks with the participants.

Establishing Trustworthiness

To develop trustworthiness in qualitative research, Lincoln and Guba (1985) presented four criteria: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. We established credibility in this study through the use of research partners in debriefing, researcher reflexivity, and participant checks. Participant checks occurred after we completed final coding. In this process, we emailed all participants a summary of the identified themes and inquired if the summary portrayed an accurate representation of the experience. Nine out of 13 participants responded and informed Bevly that no adjustments were necessary because the summary adequately captured their experiences. The remaining four participants did not respond to the follow-up email. Additionally, we utilized researcher partners in debriefing and data analysis steps to strengthen the development of the coding manual. In relation to researcher reflexivity, we bracketed our experiences by reflecting on biases and assumptions as counselors who experienced personal therapy through journaling and discussing assumptions with each other, particularly those related to positive personal experience in our own counseling. We demonstrated transferability by openly and honestly providing information about the researchers, the proposed study’s context, the participants, and study methods. This transparency allows readers to have a sense of the context when interpreting findings. We achieved dependability through documenting each task that we completed for the study by keeping an audit trail, allowing for replication. Additionally, the use of multiple data sources, including the demographic survey, interviews, and sand trays, increased the complexity of analysis (i.e., dependability). Also, we provided an in-depth description of our methodology to increase dependability of the study, including information about sample size, data collection, and data analysis that the research team used. Lastly, confirmability was based on an acknowledgement that we, as the primary researchers, cannot be truly objective (Cope, 2014). However, we triangulated the findings using participant checks, consultation with colleagues, and research team consensus to facilitate confirmability.

Findings

The research team identified six major themes and 11 subthemes (see Table 3). The six major themes were: (a) presenting concerns, (b) therapist attributes, (c) intrapersonal growth, (d) interpersonal growth, (e) therapeutic factors, and (f) challenges. We present the subthemes in more detail in the following sections using participant data as supporting evidence.

Table 3

Themes and Subthemes

| Themes |

Subthemes |

| Theme 1: Presenting concerns |

Subtheme 1a: Mental health

Subtheme 2a: Life transitions |

| Theme 2: Therapist attributes |

Subtheme 2a: Practicality

Subtheme 2b: Quality |

| Theme 3: Intrapersonal growth |

Subtheme 3a: Cognitive

Subtheme 3b: Emotional |

| Theme 4: Interpersonal growth |

Subtheme 4a: Personal

Subtheme 4b: Professional |

| Theme 5: Therapeutic factors |

Subtheme 5a: Nurturing

Subtheme 5b: Normalization

Subtheme 5c: Vulnerability

Subtheme 5d: Transference |

| Theme 6: Challenges |

Subtheme 6a: Finances

Subtheme 6b: Stigma

Subtheme 6c: Role adjustment |

Theme 1: Presenting Concerns

Presenting concerns included participants’ thoughts and feelings prior to engaging in personal therapy. Participants shared their decision-making processes and motivations leading to the initiation of personal therapy. Participants described two subthemes that captured their motivation to engage: mental health concerns and life transitions. Mental health concerns represented grief, trauma, anxiety, depression, emotional dysregulation, and relational stressors. For example, Michelle shared:

I would say those were the times when it was like I was pulled to my end, and so the depression, it was like I needed something else more than just the regular support from family and friends and then the miscarriages. It was like I felt so isolated, and then with my dad dying it was like I, gosh, this is . . . it was like both of them dying so close together.

Participants also described life transitions that served as motivation to engage in personal therapy, such as changes in relationships, careers, and living arrangements. As Lynn represented,

some of that was related to like, as a result of the divorce. I’ve moved three times in the past, like sold a house and moved out of it or kind of moved into storage while in that house in order to be able to stage it and sell it. Then out of the house into an apartment, out the apartment into a rent house. And so there’s been a lot of upheaval for me and for my child.

Presenting concerns may also be interactional in nature. For some participants (n = 10), life transitions overlapped with their mental health concerns, such as a career change triggering anxiety. However, the remaining three participants cited either mental health concerns or life transitions as a reason for initiating personal therapy. All participants differentiated their experience of internal mental health distress and external life stressors.

Theme 2: Therapist Attributes

As participants reflected on the different feelings and thought processes they experienced during the initiation of personal therapy, they also shared different attributes they looked for in a therapist. Two subthemes emerged: practicality and quality. Practicality involved factors such as location and affordability. Quality consisted of therapist credentials, training, experience, and specialty areas. All participants shared factors related to both subthemes, including Liz and Alma:

So I was like, “Okay. Well I know this person, I know this person, I know this one. Oh. I don’t know this person, okay. Let’s see if they have an opening.” I wanted someone that was close to my work because it’s easier for me just to go straight from work considering working at a hospital, I can work ridiculously long hours. Sometimes, you know, 12-hour days . . . so I needed someone in [city withheld], and I needed someone I didn’t know. (Laughs) And they took my insurance. (Liz)

I really wanted somebody who was not an intern and not a grad student. I need somebody who was fully licensed. I was looking for somebody who’d done their own work. I wouldn’t really know, but I can kind of tell. I was looking for somebody who had done their own work, their own process, and somebody who’d work with therapists. And so the first therapist that I found, she’d been a therapist for about 12 years. She had a successful private practice on her own. (Alma)

Some participants (n = 8) prioritized affordability and location over other attributes, while other participants (n = 5) emphasized education, specialty area, and recommendations as their way of selecting therapists. Each participant highlighted their need for accessibility and a good fit into their hectic schedules and personal lives. Participants described these factors as a method of narrowing down the pool of possible therapists.

Theme 3: Intrapersonal Growth

All participants expressed changes in thoughts related to self that were associated with increased perspective represented by the theme of intrapersonal growth and narrowed into subthemes of cognitive and emotional. Participants specifically reported cognitive intrapersonal growth through internal changes such as awareness, mindfulness, and a sense of purpose as outcomes of receiving personal therapy. Twelve participants described these cognitive changes as a positive experience. Jennifer described the experience as distressing due to the increased awareness of unpleasant knowledge of self and others:

I think a lot of self-awareness in the sense of why I function the way I function and an understanding of why, not only the why, but what I was needing and what I was seeking. And so, just a greater understanding of those pieces that I really had no awareness of before that. . . . I had a little awareness of it, I should say. I probably knew a little bit, but I don’t think I trusted myself in seeing that, trust in myself, trust in my intuition, and trust in my decision-making.

All participants described emotional intrapersonal growth within themselves related to regulation, stability, and expression as a result of personal therapy. Participants reported a decrease in distressing emotion, increased attunement to their emotional well-being, and an increased ability to express emotions in a healthier manner. Additionally, participants experienced fewer negative feelings toward themselves, including Thomas, who shared, “Back then I was just hiding from a lot of pain. I was hiding a lot of pain. So now I’ve been able to work through that in therapy, I’m just more emotionally attuned in general.”

All participants expressed the overlap between cognitive and emotional intrapersonal growth; furthermore, participants explained how this intrapersonal growth that occurred as a result of personal therapy carried over into other relationships. Participants shared that these internal benefits influenced external factors in their lives. Thus, the theme of intrapersonal growth led directly into the fourth theme, interpersonal growth.

Theme 4: Interpersonal Growth

All participants shared interpersonal growth, changes in relationships, and depth of social connection, both in their personal relationships and their professional relationships with clients. Participants reflected on how their growth affected relationships with romantic partners, family, friends, and clients. As a result, the two subthemes of personal relationships and professional relationships arose in the data, as expressed by Betty and Thomas:

I believe that it helped me connect with people on a deeper level. Because it’s hard to empathize or connect with someone if you can’t feel yourself. ‘Cause if you can’t feel yourself, you can’t feel what they’re feeling either. So, with my kids, I would be able to first of all, set firmer boundaries with them. And they would take me more seriously. And I’ll then also be able to connect more. And in another area, I was able to learn to ask for help. . . . instead of trying to always take care of things and handle things by myself, and to actually feel safe enough to ask for help. (Betty)

I could empathize. I could play the role of counselor and do my job, but I wasn’t doing it, like “for real for real” . . . I was falling out of what I really needed to be doing, and now I’m able to sit with clients, and every now and then my mind wanders to “oh, I gotta do this or that,” but I’m quick, I become aware of it more quickly, and I’m able to feel deeply with clients. . . . I have sessions all the time now where I’m tearing up with my clients and just feeling so moved by them. And also, I cry more in my personal life and professional life. (Thomas)

Twelve participants experienced their interpersonal growth as helpful in alleviating their presenting concerns. The remaining participant described the interpersonal growth as tense and uncomfortable. All participants explained that their interpersonal growth in personal relationships was connected to interpersonal growth in professional relationships with their clients. For example, increased boundaries with family extended to increased boundaries with clients. Participants shared that the relationship with their therapist acted as a surrogate for relationships with other people in their lives, which emerged in the therapeutic factors theme.

Theme 5: Therapeutic Factors

All participants reported avenues of healing within the context of the therapeutic alliance that led to the changes in self and in relationships. Participants reflected on how engaging in the relationship with their therapist facilitated their intrapersonal and interpersonal growth. This theme included four subthemes: nurturing, normalization, vulnerability, and transference. Seven participants described their therapist as nurturing or felt nurtured throughout the process of personal therapy. Participants reported that nurturing meant feeling safe with, trusting of, and cared for by their therapist. This atmosphere of nurturing helped participants foster the courage to take risks without fear of judgment or criticism, as expressed by Jennifer:

I felt prized, and loved, and 100% accepted. And nothing was abnormal or weird, like, what I shared. . . . her response was always super supportive. . . . My schedule was really odd, and so she made it work for my schedule. So, sometimes we met at 7:30 in the morning. Which I really appreciate. Sometimes we met at 8:00, sometimes we met at 2:00 in the afternoon . . . and I never felt like that was a burden . . . she never made it sound like I was burdening her . . . and I’m super appreciative for that.

All participants reported that their therapist, in different ways, normalized their experience. Many participants (n = 12) believed something was atypical or flawed about their personhood for needing personal therapy. Receiving help triggered feelings of stigma, self-rejection, or self-criticism. Thus, a large part of participants’ healing process was feeling normalized by the therapist. Thomas shared:

There’s even been times when I’ve asked her, like, “do I fit a diagnosis? Like, what’s wrong with me?” You know, there’s even been times when I’ve kind of demanded from her, like “what, what’s the deal? I’ve been seeing you for 2 years, tell me what’s wrong with me.” And she won’t do it. She will not do it, and she’s just like, “No, that’s not what I do.” And so that’s helped me immensely. She’s like “everything you’ve told me, every, everything fits.” And it’s helped me to see it that way.

Participants also reported feeling vulnerable as the client and described the feeling of opening themselves to the presence and feedback of another as uncomfortable but also inducing growth. Participants described this level of vulnerability as it related to their counselor identity; they explained that they were most accustomed to structuring the session and managing the time and felt more comfortable in the therapeutic relationship in the role of counselor. As the client, participants experienced a new kind of vulnerability that led to intrapersonal and interpersonal growth due to the reversed power differential, as described by Betty:

When I’m the client, it’s like, “I don’t know where we’re going, I don’t know what’s gonna come up.” It’s kind of scary sometimes. Like you know? He’s the guy with the flashlight, and I don’t know where he’s, what’s gonna happen sometimes. Like what’s going to get uncovered, [what] I’m suddenly gonna become aware of or feel, or something. So it’s a little scary.

Several participants (n = 9) shared that healing occurred as a result of therapeutic transference in the relationship with their therapist. Participants reported perceiving the therapist as a significant relationship in their life, sometimes describing their therapists as a parental presence. At times, the therapists themselves were the healing catalyst, acting as a substitute for redirecting emotional wounds. This subtheme also encompassed feelings of attachment. In many cases, participants’ early attachment figures were either emotionally or physically unavailable or harmful. Participants explained that their therapists acted as a healthy attachment figure and described this aspect of the relationship as reparative. Some participants shared feeling re-parented by their therapist, like Michelle:

She probably was the age of my mom at the time, and so I felt very nurtured by her in a way that, like I always wanted to be nurtured by mom but it hadn’t happened like that. . . . I mean, there was that transference kind of feeling that was happening, but it was very positive and she was very warm, and I feel like that relationship was so healing and allowed me to process through more things, feeling supported and encouraged by someone who is kinda like my mom but not my mom, almost like it was like a reparative thing within the relationship.

Theme 6: Challenges

Two participants shared that personal therapy was a purely positive experience without negative or uncomfortable feelings. However, 11 participants reported challenges during the course of therapy that inhibited their healing processes. These challenges included three subthemes: finances, stigma, and role adjustment, as explained by Felicity, Michelle, and Rose:

Um and then I kind of thought I was done and then I realized it was like, okay I have to add the money aspect, because every time I’m just like ugh, because I am perpetually broke. And so, I added the money like off to the side just like it’s not really part of the process but it’s this thing that exists that I can’t erase. (Felicity)

There is a stigma like that if you need to go see someone that you’re somehow like inadequate to deal with your own stuff, or that you’re crazy or that you’re really far gone, like only people who are really far gone need to do that, but I still think it’s a pride thing, you know? (Michelle)

It’s weird and it’s distracting as a client because . . . I know what she’s doing. Why is she doing that? Huh. Like it’s a good place to run to if you don’t want to go where they’re trying to take you; you can go into your analytical, left brain, logical mode. Oh, I know exactly, and you feel like an expert. You know what they’re doing. They’re not pulling it over on you. (Rose)

Five participants discussed the idea of stigma related to their counselor status. The remaining participants (n = 9) explained that they did not personally feel stigmatized, but were aware of the stigma that existed with regard to counselors who receive personal therapy. All participants shared that they would attend personal therapy longer or more frequently if not for financial barriers. Additionally, each participant described the difficulty of experiencing the identity of both client and counselor.

Discussion

We aimed to answer two overarching research questions: 1) What contributes to counselors’ decisions to seek personal therapy? and 2) How do professional counselors make meaning of their experiences in utilizing personal therapy? The results of the current study are both similar and contradictory to previous literature. For example, many researchers have demonstrated evidence of counselor burnout and compassion fatigue (Moore et al., 2020; Robino, 2019; Thompson et al., 2014). Participants described feeling burned out and lacking in empathy as motivations to seek personal therapy. Additionally, Day and colleagues (2017) outlined behavioral symptoms of burnout and compassion fatigue, including mood changes, sleep disturbances, becoming easily distracted, and increased difficulty concentrating. Many participants shared similar symptoms when discussing thoughts and feelings in their decision-making processes to initiate personal therapy, as well as when describing their mental health concerns. Therefore, it is important to assess counselors for levels of burnout and compassion fatigue in addition to raising awareness of their signs and symptoms.

The subtheme of stigma in participant voices within the current study is consistent with the existing literature. Kalkbrenner et al. (2019) found that stigma was one of three primary barriers to counseling among practicing counselors and human service professionals. Participants in our study described the general stigma and personal shame in seeking mental health treatment. Furthermore, participants differentiated between general stigma regarding mental health and stigma specific to counselors. Based on this finding, counselors may experience greater stigma than the general population when seeking personal therapy due to their professional identity. We would also like to note the research team’s personal reactions of feeling affirmed and normalized, as we had all experienced some level of stigma in seeking our own therapy—hearing and reading the participants’ experience of stigma created increased feelings of universality among our team.

With regard to theories about the working alliance, Mearns and Cooper (2017) described the notion of working at the intimate edge of the ever-shifting interface between client and counselor, referring to both the boundary between self and other and the boundary of self-awareness. Most notably in our study, the subtheme of professional interpersonal growth illuminates how the self-awareness gained in therapy impacted participants’ clinical work, supporting the working alliance theory, outlined by Mearns and Cooper (2017), which posits that expanding self-discovery and becoming more intimate with one’s own experience through the evolving relationship with the other increases intimacy in interpersonal relationships as one becomes more attuned to the self.

Aligned with the concept of professional growth, many researchers have emphasized that personal therapy was an educational or training experience for therapists and added to their professional repertoire of knowledge and skills (Anderson & Levitt, 2015; Moe & Thimm, 2021). However, these findings are not congruent with the experiences of participants in the present study. Although participants reported enhanced professional growth in terms of boundaries with clients and professional advocacy outside of the therapeutic relationship, participants shared that the intellectual aspect of personal therapy within the relationship served as a barrier to the healing process. All participants expressed a desire or intent to release themselves of their counselor identity while experiencing the client role. Thus, some counselors may not see personal therapy as a means for education or professional role modeling and instead find those aspects as distracting to the experience. It is also interesting to note that our research team’s perspectives mirrored this varied experience; through our journaling and discussion, we acknowledged that some research team members shared the experience of participants in our study, while other members felt more similarly to the preexisting literature’s conclusions.

Limitations and Future Research

The current study includes many strengths, such as the rigor we followed and trustworthiness we demonstrated. However, some limitations exist. Firstly, we collected data prior to the pandemic; a replication study post–COVID-19 could shed light on specific factors related to how the pandemic has impacted counselors’ experiences in personal therapy. Additionally, we used a single interview design, which limits the amount of extended field experience with participants. Participants may have offered more intimate and sensitive information after spending more time in the interviewing process. Due to the sensitive nature of the topic of the study, we worked to establish trust and build rapport with the participants by using introductory questions at the beginning of the interview. Researchers may collect richer data through the use of longitudinal studies that examine participants’ experiences in personal therapy over time and with other data sources. Despite plans to recruit a sample that was diverse in terms of age, gender, ethnic identification, sexual orientation, and religious/spiritual orientation, participants in this study were similar to each other. Only one participant identified as a man, and the majority of participants (n = 9) were White. We attempted to rectify the above limitations through networking with licensed professional counselors who worked in a variety of counseling settings. However, future researchers could examine the experience of counselors who identify as men or non-binary, as well as counselors of color.

Implications for Counselors

The knowledge gained from our study offers both suggestions for how clinicians can approach counselors in personal therapy and broader advocacy for the profession to increase engagement in counseling. In terms of clinical practice, participants often emphasized the struggle in assuming the client role, as they were most comfortable with the typical power differential in their professional work. This phenomenon was especially salient in the participant voices of this study; vulnerability and role adjustment were crucial themes of their experience. Therefore, it may behoove clinicians to maintain awareness of this possibility or discuss it within personal therapy. For example, Moore et al. (2020) suggested engaging in conversations about interpersonal stress, self-care, and burnout within the supervision relationship; however, we purport that clinicians of clients who are also counselors could facilitate intentional space to address these issues in counseling. That being said, mental health professionals may find benefit in balancing attending to the person of the counselor with focus on professional identity due to the barrier of role adjustment presented in this study. Neswald-Potter and colleagues (2013) suggested the use of the Wheel of Wellness Model developed by Witmer and Sweeney (1992) to facilitate an integrated approach in promoting wellness in counselors: spirituality, self-direction, work and leisure, friendship, and love. Finding meaning in all life tasks could assist clinicians in balancing professional and personal concerns in working with counselors as clients. Wellness is often associated with self-care practices in counseling.

Self-care is not a novel topic of discussion in counselor training or professional practice. However, in light of this study’s findings, we aim to describe therapeutic interventions for mental health professionals who may have counselors as clients. Coaston (2017) summarized much of the literature on self-care for counselors and recommended several strategies for interventions in three main areas: mind, body, and spirit. Concretely, interventions may include mindfulness, boundary setting, time management, cognitive reappraisal writing activities, stretching, moral inventory, and listing life principles (Coaston, 2017; Posluns & Gall, 2020). Finally, Bradley et al. (2013) outlined a variety of creative approaches to counselor self-care, as well as facilitative questions that may lend well to opening dialogue in a therapy session. Example questions include: (a) What are the indications that you are doing well and healthy? (b) Which things in the environment can be changed to help you continue to grow? and (c) Do you experience this emotion or pattern of emotions frequently? How did you respond? These suggested self-care interventions are only useful if counselors attend personal therapy, and in the results of our study, participants described how stigma remained a barrier.

Clinicians may consider normalizing thoughts and feelings related to stigma in order to encourage engagement in counseling. Sommers-Flanagan and Sommers-Flanagan (2018) defined normalization as the therapist’s use of indirect or direct statements that reframe client problems as contextual responses to the difficulties of life. Therapists use normalization to depathologize client concerns and convey implicit acceptance of the person of the client. Varying degrees of normalization skills include psychoeducation, reframing, and self-disclosure (Sommers-Flanagan & Sommers-Flanagan, 2018). Reducing the stigma of accessing counseling as a counselor may need to begin with normalizing it during training. Knaak et al. (2014) reported that the most effective anti-stigma interventions incorporate social contact, education, personal testimonies, teaching skills, and myth-busting. Therefore, creating space for anti-stigma interventions in professional development activities (e.g., conference presentations, continuing education sessions) as well as incorporating these strategies into counselor training (e.g., class or group supervision) may advocate for engagement in counseling across the counselor profession spectrum. Additionally, a follow-up study examining counselors seeking therapy to improve their own clinical efficacy with clients may also serve as a way to decrease stigma.

Lastly, we believe that the findings of our study support the need for and advocacy of personal therapy after graduate training. Unlike counselor trainee program requirements that often mandate a certain number of hours in personal therapy, fully licensed professional counselors are not regulated by licensing boards with regard to continuing personal therapy. Policy changes that include a personal therapy requirement in a similar vein as continuing education credits may positively impact counselor stigma and wellness.

Conclusion

Counselors face many challenges in their clinical work, including occupational stressors and the need for self-awareness (Moore et al., 2020; Mullen et al., 2017; Prosek et al., 2013; Robino, 2019; Thompson et al., 2014). The current descriptive phenomenological study serves to provide an understanding of the lived experiences of counselors who utilize personal therapy, including their motives to engage and meaning made while engaged. We offer clinical suggestions within the counseling relationship, steps to reduce stigma, and recommendations for facilitating self-care strategies among counselor trainees and professional counselors directly from voices of counselors who have accessed personal therapy.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Anderson, R. S., & Levitt, D. H. (2015). Gender self-confidence and social influence: Impact on working alliance. Journal of Counseling & Development, 93(3), 280–288. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12026

Bradley, N., Whisenhunt, J., Adamson, N., & Kress, V. E. (2013). Creative approaches for promoting counselor self-care. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 8(4), 456–469. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2013.844656

Coaston, S. C. (2017). Self-care through self-compassion: A balm for burnout. The Professional Counselor, 7(3), 285–297. https://doi.org/10.15241/scc.7.3.285

Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2023). 2024 CACREP standards. https://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/2024-Standards-Combined-Version-6.27.23.pdf

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). SAGE.

Day, K. W., Lawson, G., & Burge, P. (2017). Clinicians’ experiences of shared trauma after the shootings at Virginia Tech. Journal of Counseling & Development, 95(3), 269–278. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12141

Fulton, C. L., & Cashwell, C. S. (2015). Mindfulness-based awareness and compassion: Predictors of counselor empathy and anxiety. Counselor Education and Supervision, 54(2), 122–133. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12009

Gleason, B. K., & Hays, D. G. (2019). A phenomenological investigation of wellness within counselor education programs. Counselor Education and Supervision, 58(3), 177–194. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12149

Hays, D. G., & Singh, A. A. (2023). Qualitative research in education and social sciences. Cognella.

Ivers, N. N., Johnson, D. A., Clarke, P. B., Newsome, D. W., & Berry, R. A. (2016). The relationship between mindfulness and multicultural counseling competence. Journal of Counseling & Development, 94(1), 72–82. https://doi.org10.1002/jcad.12063

Kalkbrenner, M. T., Neukrug, E. S., & Griffith, S.-A. M. (2019). Appraising counselor attendance in counseling: The validation and application of the Revised Fit, Stigma, and Value Scale. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 41(1), 21–35. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.41.1.03

Knaak, S., Modgill, G., & Patten, S. B. (2014). Key ingredients of anti-stigma programs for health care providers: A data synthesis of evaluative studies. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 59(1 suppl), 19–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371405901S06

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. SAGE.

Mearns, D., & Cooper, M. (2017). Working at relational depth in counselling and psychotherapy (2nd ed.). SAGE.

Measham, T., & Rousseau, C. (2010). Family disclosure of war trauma to children. Traumatology, 16(4), 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765610395664

Merriman, J. (2015). Enhancing counselor supervision through compassion fatigue education. Journal of Counseling & Development, 93(3), 370–378. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12035

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2019). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (4th ed.). SAGE.

Moe, F. D., & Thimm, J. (2021). Personal therapy and the personal therapist. Nordic Psychology, 73(1), 3–28.

https://doi.org/10.1080/19012276.2020.1762713

Moore, C. M., Andrews, S. E., & Parikh-Foxx, S. (2020). “Meeting someone at the edge”: Counselors’ experiences of interpersonal stress. Journal of Counseling & Development, 98(2), 123–135. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12307

Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. SAGE.

Mullen, P. R., Morris, C., & Lord, M. (2017). The experience of ethical dilemmas, burnout, and stress among practicing counselors. Counseling and Values, 62(1), 37–56. https://doi.org/10.1002/cvj.12048

Neswald-Potter, R. E., Blackburn, S. A., & Noel, J. J. (2013). Revealing the power of practitioner relationships: An action-driven inquiry of counselor wellness. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 52(2), 177–190. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1939.2013.00041.x

Orlinsky, D. E. (2013). Reasons for personal therapy given by psychoanalytically oriented psychotherapists and their effects on personal wellbeing and professional development. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 30(4), 644–662. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034587

Pompeo, A. M., & Levitt, D. H. (2014). A path of counselor self-awareness. Counseling & Values, 59(1), 80–94. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-007X.2014.00043.x

Posluns, K., & Gall, T. L. (2020). Dear mental health practitioners, take care of yourselves: A literature review on self-care. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 42, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-019-09382-w

Prosek, E. A., & Gibson, D. M. (2021). Promoting rigorous research by examining lived experiences: A review of four qualitative traditions. Journal of Counseling & Development, 99(2), 167–177. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12364

Prosek, E. A., Holm, J. M., & Daly, C. M. (2013). Benefits of required counseling for counseling students. Counselor Education & Supervision, 52(4), 242–254. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2013.00040.x

Rake, C., & Paley, G. (2009). Personal therapy for psychotherapists: The impact on therapeutic practice. A qualitative study using interpretative phenomenological analysis. Psychodynamic Practice, 15(3), 275–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/14753630903024481

Remley, T. P., Jr., & Herlihy, B. (2020). Ethical, legal and professional issues in counseling (6th ed.). Merrill.

Robino, A. E. (2019). Global compassion fatigue: A new perspective in counselor wellness. The Professional Counselor, 9(4), 272–284. https://doi.org/10.15241/aer.9.4.272

Rosin, J. (2015). The necessity of counselor individuation for fostering reflective practice. Journal of Counseling & Development, 93(1), 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2015.00184.x

Sommers-Flanagan, J., & Sommers-Flanagan, R. (2018). Counseling and psychotherapy theories in context and practice: Skills, strategies, and techniques (3rd ed.). Wiley.

Sue, D. W., Sue, D., Neville, H. A., & Smith, L. (2022). Counseling the culturally diverse: Theory and practice (9th ed.). Wiley.

Thompson, I. A., Amatea, E. S., & Thompson, E. S. (2014). Personal and contextual predictors of mental health counselors’ compassion fatigue and burnout. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 36(1), 58–77. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.36.1.p61m73373m4617r3

Tufekcioglu, S., & Muran, J. C. (2015). Case formulation and the therapeutic relationship: The role of therapist self-reflection and self-revelation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 71(5), 469–477. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22183

VanderWal, B. L. (2015). The relationship between counselor trainees’ personal therapy experiences and client outcome (Publication No. 1199) [Doctoral dissertation, Western Michigan University]. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/1199

Witmer, J. M., & Sweeney, T. J. (1992). A holistic model for wellness and prevention over the life span. Journal of Counseling & Development, 71(2), 140–148. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1992.tb02189.x

Yaites, L. D. (2015). The essence of African Americans’ decisions to seek professional counseling services: A phenomenological study [Doctoral dissertation, University of North Texas]. https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc804978

Appendix

Dax Bevly, PhD, is core faculty at Antioch University Seattle. Elizabeth A. Prosek, PhD, NCC, LPC, is an associate professor at The Pennsylvania State University. Correspondence may be addressed to Dax Bevly, Antioch University Seattle, School of Applied Psychology, Counseling, and Family Therapy, 2400 3rd Ave #200, Seattle, WA 98121, dbevly@antioch.edu.

Aug 24, 2023 | Volume 13 - Issue 2

Kyoung Mi Choi, Jung H. Hyun

This study, using a transcendental phenomenological approach, explored the perceptions and experiences of school counselor trainees participating in a self-care course grounded in mindfulness and social–emotional learning. Seven students who enrolled in a master’s-level school counseling program and completed a summer self-care course shared their experiences, leading to the identification of five key themes: (a) recognizing the importance and need for self-care, (b) cultivating a nonjudgmental mindset toward challenging emotions, (c) integrating self-care into both personal and professional settings, (d) an increase in compassion and empowerment, and (e) a commitment to ongoing learning and advocacy. The school counselor trainees’ narratives highlight the importance of self-care as a way to reclaim power within themselves and become change agents in their school communities.

Keywords: school counselor trainees, self-care, mindfulness, social–emotional learning, advocacy

The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically changed the way we live, work, learn, and interact on a daily basis, making self-care a crucial topic of discussion in both schools and workplaces (Harrichand et al., 2021; Norcross & Phillips, 2020). Many K–12 students are facing increased emotional distress and mental health issues, such as high levels of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic symptoms (Chen et al., 2020; Marques de Miranda et al., 2020; Prime et al., 2020). At the same time, school counselors are also struggling with issues such as fatigue, burnout, and even vicarious trauma (Parker & Henfield, 2012), along with other challenges like high workloads, uncertainty about their role, and a lack of perceived support and professional development opportunities (Savitz-Romer et al., 2021). This makes self-care for school counselors and trainees more critical now than ever before (Harrichand et al., 2021).

Self-care refers to engaging in activities or behaviors that promote one’s overall wellness and prevent burnout (Christopher et al., 2016). This concept can also be expanded to include a larger sense of self-care that encompasses embracing one’s humanity; increasing awareness of internalized negative cultural messages; and fostering a positive cultural identity that embraces one’s heritage and community strengths, assets, traditions, and legacy (Duncan-Andrade & Morrell, 2008). Some scholars view self-care as the start of personal power (hooks, 1994) and a process of humanization in education that is reciprocal, anti-oppressive, and supportive of collective well-being (Paris & Winn, 2013). Additionally, many educators and scholars believe that dismantling oppressive ideologies and power structures is an important objective in the transformative process of self-care, which involves critical self-reflection, recognition of dehumanization, and reclaiming agency (Berila, 2016; Freire, 1970/2000; hooks, 1994; Litam & Hipolito-Delgado, 2021).

The significance of self-care has led to it being viewed not just as an individual responsibility, but also a professional one. Leading counseling organizations, such as the American Counseling Association (ACA) and the Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP), consider self-care to be a crucial aspect of a mental health professional’s duties. The ACA Code of Ethics (2014) states that “counselors engage in self-care activities to maintain and promote their own emotional, physical, mental, and spiritual well-being to best meet their professional responsibilities” (p. 8). The CACREP (2015) standards, under the Professional Counseling Identity section, include standards for counselor education programs that emphasize self-care strategies appropriate to the counselor role (Section 2.F.1.i). The American School Counselor Association (ASCA; 2019) promotes the monitoring of “emotional and physical health and practice wellness to ensure optimal professional effectiveness” for school counselors (p. 7).

However, despite the recognition of self-care as an ethical responsibility, most counseling training programs do not incorporate it as part of their curriculum (Chen et al., 2020; Christopher & Maris, 2010; Shapiro et al., 2007). Lack of time, academic pressure, and the absence of guidance and faculty role models are cited as barriers (Campbell & Christopher, 2012; Christopher & Maris, 2010; Nelson et al., 2018). Nevertheless, there is a pressing need for self-care strategies to be included in counselor training and curriculum (Mitchell & Binkley, 2021). This study utilized transcendental phenomenology to investigate the essence of self-care experiences among school counseling trainees who participated in a 10-session seminar course that focused on mindfulness and social–emotional learning (SEL).

Literature Review

Mindfulness as Humanizing Process in Self-Care

The integration of mindfulness as a self-care practice into counseling training and programs has been widely adopted over the past three decades (Bohecker & Horn, 2016; Bohecker et al., 2016; Campbell & Christopher, 2012; Christopher & Maris, 2010; Shapiro et al., 2007). Research has shown that mindfulness can lead to numerous benefits, including reduced levels of anxiety and depression, enhanced life satisfaction, increased social connection, optimism, tolerance, empathy, and self-efficacy (Bohecker & Horn, 2016; Bohecker et al., 2016; Brown & Ryan, 2003). Christopher and Maris (2010) asserted that incorporating mindfulness practices into counselor training programs could help reduce burnout, compassion fatigue, and other stress-related physical and psychological symptoms by providing education in self-care and stress management. Furthermore, Shapiro and his team (2007) found that Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction training had a significant impact, decreasing stress levels, negative affect, rumination, and anxiety, and boosting positive affect and self-compassion.

Moreover, mindfulness is more than just a form of relaxation, but a transformative and proactive approach to self-care. It involves increased awareness of internalized negative cultural messages and the cultivation of a positive cultural identity (Duncan-Andrade & Morrell, 2008). The practice of mindfulness can lead to critical self-reflection and bring to the surface issues of power and privilege, and through deep reflection and honest dialogue, can support the process of humanization and the dismantling of oppressive ideologies (Berila, 2016; del Carmen Salazar, 2013).

Given the high levels of stress and burnout that school counselors commonly experience, prioritizing self-care practices is crucial for maintaining their personal and professional well-being. Mindfulness-based self-care has emerged as a promising approach for addressing these challenges and provides a unique opportunity for school counselors to reflect on their identities within societal and cultural contexts. Additionally, the SEL framework can be helpful in self-care training by outlining specific skills essential for managing stress, fostering well-being, and developing advocacy in both personal and professional contexts.

Social–Emotional Learning

SEL is defined as “the process in which children enhance their ability to integrate thinking, feelings, and behaving to achieve important life tasks” (Zins et al., 2007, p. 194). The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) outlines five core competencies of SEL: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making (CASEL, 2023a). CASEL’s mission is to make SEL a fundamental aspect of every child’s education through offering training and educational opportunities to advance scientific research, assessment, and implementation of effective SEL practices in schools (CASEL, 2023b). Numerous studies have demonstrated the positive impact of SEL programs on students’ growth (Carrell & Carrell, 2006; Durlak & DuPre, 2008; Lapan & Harrington, 2009).

Despite the positive effects of SEL in education, its traditional definition has faced numerous criticisms for its inadequacy in addressing equity and justice issues in classrooms and the educational system in light of recent racial and gender awareness. Higheagle Strong and McMain (2020) argued that the traditional SEL approach reinforces oppressive ideologies by valuing White, middle-class knowledge systems above others, portraying marginalized students as troubled and incompetent, and perpetuating injustice. With a growing emphasis on cultural responsiveness in the SEL definition (Higheagle Strong & McMain, 2020; Jagers et al., 2019), a critical question arises: “Are we teaching individual students to manage their emotions and behaviors simply for the sake of upward mobility or recognize and reclaim their emotions and relationships as fuel for social and cultural healing and transformation?” (Camangian & Cariaga, 2021, p. 16).

CASEL subsequently revised their definition of SEL and introduced a new concept of transformative SEL, defined as “a process whereby students and teachers build strong, respectful relationships founded on an appreciation of similarities and differences; learn to critically examine root causes of inequity; and develop collaborative solutions to community and social problems” (Jagers et al., 2018, p. 2). This updated definition acknowledges existing educational disparities and places an emphasis on authentic partnerships between schools, families, and communities. It also calls for a re-examination of the curriculum, instructional methods, and evaluation systems. Educators are encouraged to adopt an equity-focused lens when assessing the five core SEL competencies, asking questions such as “What are the social dynamics among students from different backgrounds in your class? Do you view these differences as a liability or an asset?”, “How do you create an inclusive and safe learning environment for all your students?”, and “Are there policies or practices in your school that prevent your students from receiving the quality education they deserve?”

Overall, the principles of SEL are closely aligned with the goals of school counseling, particularly in developing the skills necessary for promoting the social, emotional, and cognitive development of their students and promoting equity, social justice, and cultural competence necessary for supporting diverse student populations. School counselors can leverage SEL strategies to create a welcoming and inclusive environment that fosters learning, resilience, and well-being among students. Van Velsor (2009) emphasized the role of school counselors as SEL consultants, empowering students to achieve their personal goals and promoting prosocial behaviors, with the ultimate aim of improving the well-being of both the school and society.

Self-care has been integrated into the ethical standards of school counselor preparation programs (Christopher et al., 2016; Nelson et al., 2018), and mindfulness is often taught and studied in these programs (Campbell & Christopher, 2012; Christopher & Maris, 2010). However, there has been a lack of research investigating the experiences of school counselor trainees when learning and practicing self-care alongside mindfulness and SEL competencies in counselor education. In this study, we created and implemented a self-care curriculum for school counseling trainees and examined how this curriculum impacted their personal and professional lives through the use of transcendental phenomenology. The goal was to delve into the experiences of master’s students who took part in a summer course on self-care that was grounded in both mindfulness and SEL.

Methodology

The transcendental phenomenological investigation is often used in research to explore individuals’ subjective experiences and perceptions of a particular phenomenon (Giorgi, 2009; Moustakas, 1994). Using this approach, we aimed to explore the school counseling trainees’ thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of the personal and professional changes in the areas of self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making. The umbrella research question that guided this study was “What is the essence of the lived experiences of self-care of school counseling trainees who took 10 seminar sessions grounded in mindfulness and SEL in a master’s-level counseling program over a 5-week period?” Semi-structured interview questions were used to explore the participants’ experiences in their own words, which are detailed in Appendix A. After the approval from the IRB, we invited counseling trainees to participate in the study and followed the three steps of Moustakas’s (1994) transcendental approach: (a) the epoche, (b) the eidetic reduction, and (c) the transcendental reduction in data analysis.

Participants

The purposive sampling method outlined by Glesne (2011) was utilized to select participants for the study. Invitations were extended to all 15 students who had completed the EDCO 298 Seminar in Professional Counseling during the summer course. Based on the guidelines set by Polkinghorne (1989), a sample size of 5–25 individuals is recommended for a phenomenological study. Seven participants, who were female graduate students in the counselor education program, agreed to take part in the study through in-depth interviews. The participants were between the ages of 21 and 45 and attended a single, midsized, public university designated as a Hispanic-Serving Institution in Northern California, United States. Five of the participants identified as Hispanic, Mexican, or Latinx, while two identified as White.

Data Collection

The data for this study was collected through qualitative interviews with individuals who had completed a summer course, EDCO 298 Seminar in Professional Counseling, taught by Kyoung Mi Choi. To ensure impartiality and minimize the impact of the professor’s influence, three precautions were taken: (a) participants were contacted at least 14 days after the course had ended and their grades were posted, (b) they were informed that participation in the study was voluntary, and (c) all interviews were conducted by Jung Hee Hyun, who had no association with the program and held no power over the students’ grades.

Description of the Course

In summer 2020, Choi created an online 5-week course called EDCO 298 Seminar in Professional Counseling, which is detailed in Appendix B. The focus of the course was on self-care, combining six mindfulness core values (such as presence, gratitude, and compassion) and the five SEL competencies framework (self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making). The course was attended by 15 master’s-level school counseling students. The aim of the class was to encourage and inspire the students to make a deeper connection with their thoughts, emotions, and physical well-being.

The objectives of the course were to (a) explore the five SEL competencies, (b) explore the mindfulness-based self-care and SEL interventions for counseling and personal growth, (c) understand the effectiveness of the SEL tools and practice mindfulness in daily life, and (d) create a workshop that serves the community the student hopes to serve. The instructor’s role was to create a supportive and safe environment in which students could share their personal narratives and experiences, including their strengths, cultural assets, resilience, privilege, discrimination, and oppression. Throughout the course, various mindfulness practices were utilized, such as collective breathing, body scan, mindful walking, mindful eating, mindful speaking, journaling, storytelling, visualization, and meditation.

Individual Interviews

After the summer session was over, Choi’s counselor education department gave permission to announce the research project via email. Those who showed interest in participating were given a research packet containing details of the study, informed consent, and a demographic sheet, as well as contact information for further inquiries. At every stage of the recruitment and research process, it was emphasized that participation or non-participation in the study would not affect the participants’ course credit or final grade. To be eligible for the study, participants had to meet the following criteria: (a) enrolled in the counselor education program, (b) completed the summer seminar, (c) successfully finished the entire course, and (d) willing to participate in a voluntary lengthy interview.

Once students agreed to participate in the study and submitted their informed consent, contact information, and demographic questionnaire (including a pseudonym, gender, age, self-identified ethnicity, and specialization), they were individually interviewed by Hyun through Zoom. The interviews lasted for approximately an hour and followed a semi-structured format consisting of 16 open-ended questions asked in a consistent order (see Appendix A). The interviews were recorded in their entirety and then transcribed by a graduate student who was not affiliated with the study. After being reviewed by the participants and analyzed by the researchers, the audio recordings were deleted. To maintain the confidentiality of the participants, only pseudonyms were used in all written materials.

Data Analysis