Feb 9, 2015 | Article, Volume 5 - Issue 1

Ashley J. Blount, Patrick R. Mullen

Supervision is an integral component of counselor development with the objective of ensuring safe and effective counseling for clients. Wellness also is an important element of counseling and often labeled as the cornerstone of the counseling profession. Literature on supervision contains few models that have a wellness focus or component; however, wellness is fundamental to counseling and the training of counselors, and is primary in developmental, strengths-based counseling. The purpose of this article is to introduce an integrative wellness model for counseling supervision that incorporates existing models of supervision, matching the developmental needs of counselors-in-training and theoretical tenets of wellness.

Keywords: supervision, wellness, counselors-in-training, integrative wellness model, developmental

The practice of counseling is rich with challenges that impact counselor wellness (Kottler, 2010; Maslach, 2003). Consequently, counselors with poor wellness may not produce optimal services for the clients they serve (Lawson, 2007). Furthermore, wellness is regarded as a cornerstone in developmental, strengths-based approaches to counseling (Lawson, 2007; Lawson & Myers, 2011; Myers & Sweeney, 2005, 2008; Witmer, 1985; Witmer & Young, 1996) and is an important consideration when training counselors (Lenz & Smith, 2010; Roach & Young, 2007). Therefore, a focus on methods by which counselor educators can prepare counseling trainees to obtain and maintain wellness is necessary.

Clinical supervision is an integral component of counselor training and involves a relationship in which an expert (e.g., supervisor) facilitates the development of counseling competence in a trainee (Loganbill, Hardy, & Delworth, 1982). Supervision is a requirement of master’s-level counseling training programs and is a part of developing and evaluating counseling students’ skills (Borders, 1992), level of wellness (Lenz, Sangganjanavanich, Balkin, Oliver, & Smith, 2012), readiness for change (Aten, Strain, & Gillespie, 2008; Prochaska & DiClemente, 1982) and overall development into effective counselors (Bernard & Goodyear, 2014). Supervisors use pedagogical methods and theories of supervision to assess and evaluate trainees with the goal of enhancing their counseling competence (American Counseling Association [ACA], 2014; Bernard & Goodyear, 2014). The method or theory of supervision relates to the interaction between counselor educators and counseling trainees and is isomorphic to a counselor using a theory with a client.

The number of supervision theories and methods has increased over recent years. In addition, integrated supervision models have been established with a focus on specific trainee groups (e.g., Carlson & Lambie, 2012; Lambie & Sias, 2009) or specific purposes (e.g., Luke & Bernard, 2006; Ober, Granello, & Henfield, 2009). These integrated models combine the theoretical tenets of key models with the goal of formulating a new perspective for clinical training that adapts to the needs of the supervisee or context. Lenz and Smith (2010) and Roscoe (2009) suggested that the construct of wellness needs further clarification and articulation as a method of supervision. Currently, a single model of supervision with a wellness perspective is available (see Lenz & Smith, 2010). However, it does not specifically apply to master’s-level counselors-in-training (CITs) or focus on the wellness constructs highlighted in the proposed integrative wellness model (IWM). Therefore, this manuscript serves to review relevant literature on supervision and wellness, introduce the IWM, and present implications regarding its implementation and evaluation.

Supervision

ACA (2014), the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP; 2009), and the Association for Counselor Education and Supervision (ACES; 2011) have articulated standards for best practices in supervision. For example, ACES’ (2011) Standards for Best Practices Guidelines highlights 12 categories as integral components of the supervision process. The categories include responsibilities of supervisors and suggestions for actions to be taken in order to ensure best practices in supervision. The ACA Code of Ethics (2014) states that supervision involves a process of monitoring “client welfare and supervisee performance and professional development” (Standard F.1.a). Furthermore, supervision can be used as a tool to provide supervisees with necessary knowledge, skills and ethical guidelines to provide safe and effective counseling services (Bernard & Goodyear, 2014).

Supervision has two central purposes: to foster supervisees’ personal and professional development and to protect clients (Vespia, Heckman-Stone, & Delworth, 2002). Supervisors work to ensure client welfare by monitoring and evaluating supervisee behavior, which serves as a gatekeeping tool for the counseling profession (Robiner, Fuhrman, Ristvedt, Bobbit, & Schirvar, 1994). Thus, supervisors protect the counseling profession and clients receiving counseling services by providing psychoeducation, modeling appropriate counselor behavior, and evaluating supervisees’ counseling skills and other professional behaviors. In order to do this, supervisors and supervisees must have a strong supervisory relationship that supports positive supervision outcomes (Rønnestad & Skovholt, 2003).

Supervision is a distinct intervention (Borders, 1992) that is separate from teaching, counseling and consultation. Supervision is unique in that it is comprised of multifaceted (e.g., teacher, counselor and consultant) roles that occur at different times throughout the supervision process (Bernard, 1997). Bernard’s (1979, 1997) discrimination model (DM) of supervision is an educational perspective positing that supervisors can match the needs of supervisees with a supervisor role and supervision focus. The DM is situation specific, meaning that supervisors can change roles throughout the supervision session based on their goal for supervisee interaction (Bernard, 1997). Therefore, supervisees require different roles and levels of support from their supervisors at different times throughout the supervision process, which can be determined by a process of assessment and matching of supervisee needs.

According to Worthen and McNeill (1996), supervision varies according to the developmental level of trainees. Beginning supervisees need more support and structure than intermediate or advanced supervisees (Borders, 1990). Additionally, supervisors working with beginning supervisees must pay more attention to student skills and aid in the development of self-awareness. With intermediate supervisees, supervision may focus on personal development, more advanced case conceptualizations of clients and operating within a specific counseling theory (McNeill, Stoltenberg, & Pierce, 1985). Advanced supervisees work on more complex issues of personal development, parallel processes or a replication of the therapeutic relationship in a variety of settings (e.g., counseling, supervision; Ekstein & Wallerstein, 1972), and advanced responses and reactions to clients (Williams, Judge, Hill, & Hoffman, 1997). Consequently, supervision progresses from beginning stages to advanced stages for supervisees, with a developmental framework central to the process. Supervision is tailored to the specific developmental level of a supervisee, and tasks are personalized for needs at specific times throughout the supervision process. Developmental stages in supervision have been identified as key processes that counselor trainees undergo (e.g., Rønnestad & Skovholt, 2003; Stoltenberg & McNeill, 2012), a conceptualization that necessitates a supervision model that aids supervisees in a developmental fashion.

Recent models of supervision represent trends toward integrative and empirically based supervision modalities (e.g., Bernard & Goodyear, 2014; Lambie & Sias, 2009). The current integrated model of supervision draws from the theoretical tenets of the DM (Bernard, 1979, 1997), matching supervisee developmental needs (Lambie & Sias, 2009; Loganbill et al., 1982; Stoltenberg, 1981) and wellness constructs (Lenz et al., 2012; Myers, Sweeney, & Witmer, 1998). Wellness is a conscious, thoughtful process that requires increased awareness of choices that are being made toward optimal human functioning and a more satisfying lifestyle (Johnson, 1986; Swarbrick, 1997). As such, the IWM includes wellness undertones in order to support optimal supervisee functioning. This article presents the IWM’s theoretical tenets, implementation and methods for supervisee evaluation. In addition, a case study is presented to demonstrate the IWM’s application in clinical supervision.

Theoretical Tenets Integrated Into the IWM of Supervision

The DM (Bernard, 1979, 1997) is considered “one of the most accessible models of clinical supervision” (Bernard & Goodyear, 2014, p. 52) and includes the following three supervisor roles: teacher, counselor and consultant. In the teacher role, the supervisor imparts knowledge to the supervisee and serves an educational function. The counselor role involves the supervisor aiding the supervisee in increasing self-awareness, enhancing reflectivity, and working through interpersonal and intrapersonal conflicts. Lastly, the consultant role provides opportunities for supervisors and supervisees to have discussions on a balanced level (Bernard, 1979). The three roles are used throughout the supervision process to promote supervisee learning, growth and development.

The DM of supervision is situation specific in that supervisors enact different roles throughout the supervision session based on the observed need of the supervisee (Bernard & Goodyear, 2014). As needs arise in supervision, the supervisor decides which role is best suited for the issue or concern. This process requires the supervisor to identify or assess a need and to make a decision regarding the appropriate role (i.e., teacher, counselor or consultant) to facilitate appropriate supervision. Furthermore, the use of supervisory roles is fluid, with its ebb and flow contingent upon the supervisee needs or issues. For example, if a supervisee is struggling with how to review informed consent, a supervisor can use the teacher role to educate the student on how to proceed, and then address the supervisee’s anxiety about seeing his or her first client using the counseling role. The DM roles are integrated into the IWM, and supervisors alternate between roles to match supervisee needs throughout the supervision process.

Developmental Tenets

The authors of developmental models have suggested that counseling trainees progress in a structured and sequential fashion through stages of development that increase in complexity and integration (e.g., Blocher, 1983; Loganbill et al., 1982; Stoltenberg, 1981; Stoltenberg & McNeill, 2010). In early experiences, supervisees engage in rigid thinking, have high anxiety and dependence on the supervisor, and express low confidence in their abilities (Borders & Brown, 2005; Rønnestad, & Skovholt, 2003; Stoltenberg & McNeill, 2012). Moreover, supervisees have limited understanding of their own abilities and view their supervisor as an expert (Borders & Brown, 2005; Stoltenberg & McNeill, 2010). Struggles between independency and autonomy, as well as bouts of self-doubt, occur during the middle stages of counselor development (Borders & Brown, 2005; Stoltenberg & McNeill, 2010). In addition, counselors experience decreased anxiety paired with an increase in case conceptualization, skill development and crystallization of theoretical orientation (Stoltenberg & McNeill, 2010). Thinking becomes more flexible and there is an increased understanding of unique client qualities and traits (Borders & Brown, 2005). The later stages of counselor development are marked by increased stability and focus on clinical skill development and professional growth, which promotes a flexibility and adaptability that allows for trainees to overcome setbacks with minimal discouragement (Stoltenberg & McNeill, 1997). Furthermore, supervisees focus on more complex information and diverse perspectives as they learn to conceptualize clients more effectively (Borders & Brown, 2005).

In summary, supervisees’ movement through the developmental stages is marked by individualized supervision needs. Structured, concrete feedback and information are desired in early supervision experiences (Bernard, 1997; Stoltenberg & McNeill, 2010). The middle stages have a general focus on processing the interpersonal reactions in which supervisees engage, and supervisors provide support to help supervisees increase their awareness of transference and countertransference (Borders & Brown, 2005; Stoltenberg, 1981). Toward the later stages of supervision, supervisees seek collaborative relationships with supervisors. This collaboration provides supervisees with more freedom and autonomy, which allows them to progress through the stages as they begin to self-identify the focus of their supervision (Borders & Brown, 2005).

Similar to the IWM, models of supervision that are development-focused derive from Hunt’s (1971) matching model that suggests a person–environment fit (Stoltenberg, McNeill, & Crethar, 1994). The matching model advocates that the developmental level of supervisees should be matched with environmental or contextual structures to enhance the opportunity for learning (Lambie & Sias, 2009). Specifically, the developmental models account for trainees’ needs specific to their experience level and contextual environment, with the goal of matching interventions to support movement into more advanced developmental levels (Bernard & Goodyear, 2014; Stoltenberg & McNeill, 2012). The IWM derives its developmental perspective from the unique levels trainees experience during supervision and the cycling and recycling of stages that occurs (Loganbill et al., 1982).

Wellness and Unwellness

Wellness is a topic that has received much attention in counseling literature (Hattie, Myers, & Sweeney, 2004), including several perspectives on how to define wellness (Keyes, 1998). Dunn (1967) is considered the architect of the wellness crusade and described wellness as an integration of spirit, body and mind. The World Health Organization (1968) defined health as more than the absence of disease and emphasized a wellness quality, which includes mental, social and physical well-being. Cohen (1991) described wellness as an idealistic state that individuals strive to attain, and as something that is situated along a continuum (i.e., people experience bouts of wellness and unwellness). Witmer and Sweeney (1992) depicted wellness as interconnectedness between health characteristics, life tasks (spirituality, love, work, friendship, self), and life forces (family, community, religion, education). Additionally, Roscoe (2009) depicted wellness as a holistic paradigm that includes physical, emotional, social, occupational, spiritual, intellectual and environmental components. Witmer and Granello (2005) stated that the counseling profession is distinctively suited to promoting health and wellness with a developmental approach and, coincidentally, supervision could serve as a tool to promote wellness in supervisees as well as in clients receiving counseling services.

Smith, Robinson, and Young (2007) found that counselor wellness is negatively influenced by increased exposure to psychological distress. Furthermore, research has shown that counselors face stress because of the nature of their job (Cummins, Massey, & Jones, 2007). Increased stress and anxiety associated with counseling may have deleterious effects on counselor wellness, and supervisors and supervisees who are unwell may adversely impact their clients. In addition, Lawson and Myers (2011) suggested that increasing counselors’ wellness could lead to increased compassion satisfaction and aid counselors in avoiding compassion fatigue and burnout. Thus, supervisee and supervisor wellness should be an important component of counselor training and supervision. The IWM makes counselor wellness a focus of the supervision process.

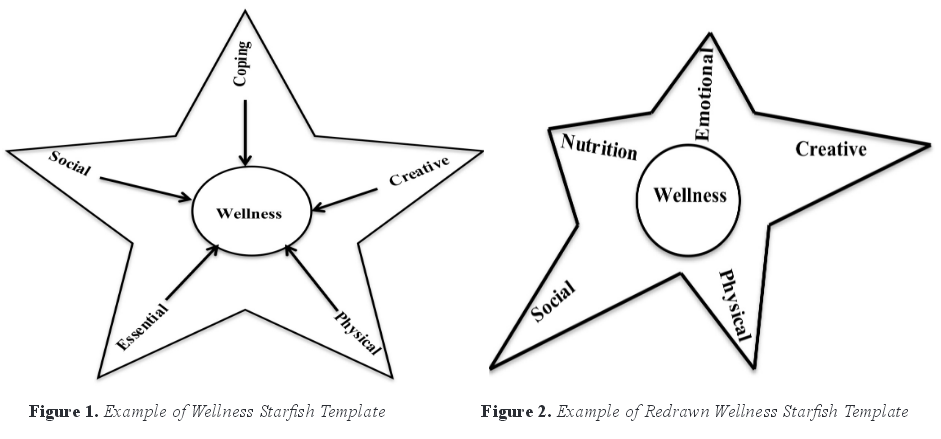

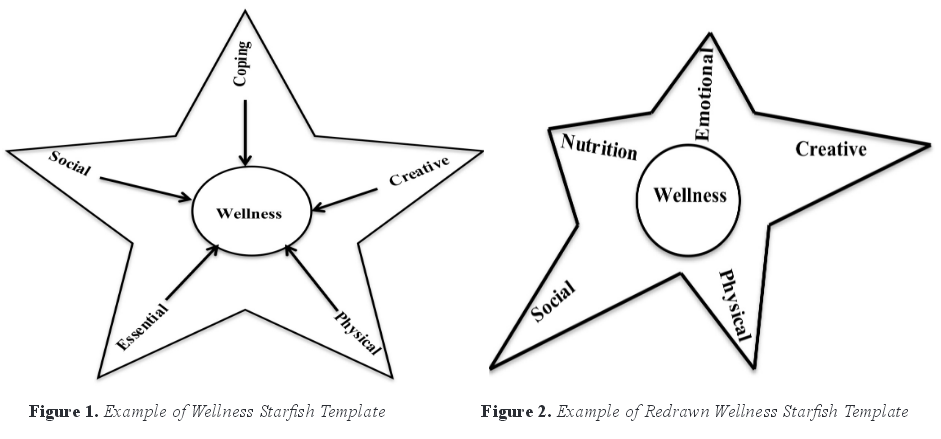

Supervision literature contains few supervision models that include wellness components and/or focus on wellness as a key aspect of the supervision experience (e.g., Lenz et al., 2012; Lenz & Smith, 2010). Nevertheless, the paradigm of wellness has emerged in the field of counseling and is primary in developmental, strengths-based counseling (Lenz & Smith, 2010; Myers & Sweeney, 2005). The CACREP 2009 Standards note the importance of wellness for counseling students and counselor educators by promoting human functioning, wellness and health through advocacy, prevention and education. To illustrate, the CACREP 2009 Standards include suggestions of facilitating optimal development and wellness, incorporating orientations to wellness in counseling goals, and using wellness approaches to work with a plethora of populations. The overall goal of wellness counseling is to support wellness in clients (Granello & Witmer, 2013). However, if supervisees seeing clients are unwell, how efficient are they in promoting wellness in others? In order to support development of wellness in supervisees, the IWM incorporates the five wellness domains of creative, coping, physical, essential and social (Myers, Luecht, & Sweeney, 2004) by implementing the use of the Five Factor Wellness Evaluation of Lifestyle (5F-Wel; Myers et al., 2004). In addition, supervisees can use a starfish template (Echterling et al., 2002) to gauge their own wellness and prioritize the constructs that influence their personal and professional levels of wellness and unwellness, as well as create plans to increase their overall wellness.

Implementing the IWM

The IWM was created to offer an integrative method of supervision that is concise and easy to facilitate. Specifically, the IWM consists of several processes, including supervisory relationship development, evaluation of developmental phase, allocation of supervision need, and assessment and matching of wellness intervention. The following section outlines each process.

Supervisory Relationship Development

Rapport building and relationship development between supervisor and supervisee constitute a critical step in supervision (Hird, Cavalieri, Dulko, Felice, & Ho, 2001). Similar to counseling, establishing a strong, trusting supervisory relationship is essential because the relationship is an integral component of the supervision experience (Borders & Brown, 2005; Rønnestad & Skovholt, 1993). During initial sessions, supervisors describe the process of the IWM to supervisees in order to maintain open, transparent communication and to promote a safe environment for supervisees to learn, share emotions and feelings, and develop counseling skills. It is hoped that modeling appropriate professional behaviors and setting up supervision sessions to promote a trusting environment will aid in the overall development of counseling supervisees and matriculate into their normal routines as professional counselors. As with counseling, supervisors can promote a strong relationship with supervisees by focusing on the core conditions of empathy, genuineness and unconditional positive regard (Rogers, 1957). Open communication and supervisor authenticity are just two examples of processes that help develop a sound supervisor–supervisee relationship.

Evaluation of Developmental Phase

Supervisee development is an important consideration in the IWM. The IWM divides supervisee development into three phases that consist of distinct developmental characteristics. Similar to Stoltenberg and McNeill’s (2010) suggestion and other integrative models (e.g., Carlson & Lambie, 2012; Young, Lambie, Hutchinson, & Thurston-Dyer, 2011), the phases in the IWM are hierarchical in nature, with the highest phase (phase three) being ideal for developed supervisees. In addition, the IWM acknowledges the preclinical experiences (e.g., lay helper; Rønnestad, & Skovholt, 2003) of supervisees as valuable and relevant to their development. In the IWM, it is important to acknowledge and address the experiences that supervisees have had prior to their work as counselors because they may impact perceptions and expectations.

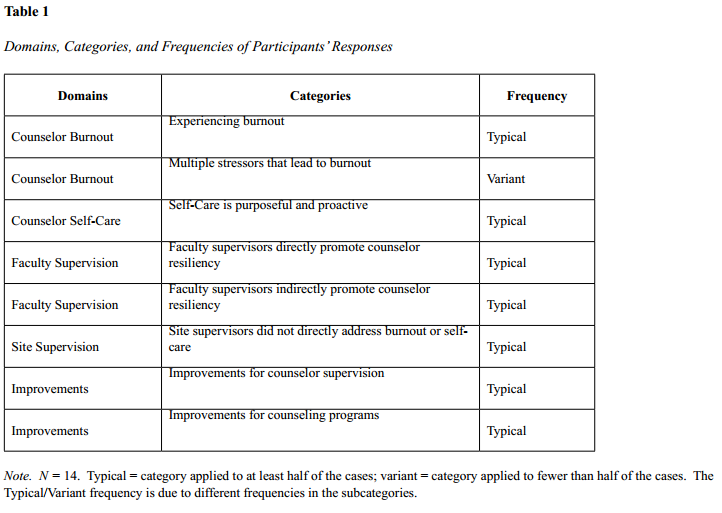

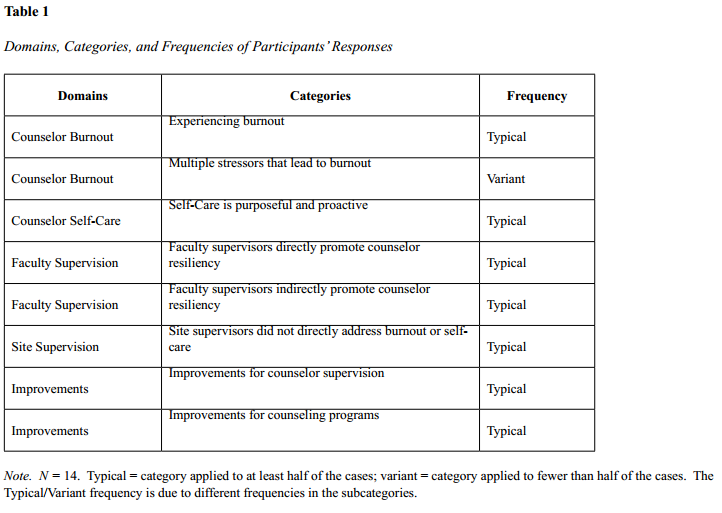

For example, supervisors can facilitate activities to promote awareness of how supervisees influence counseling sessions. To illustrate, supervisees may participate in activities highlighting culture, family-of-origin, character strengths and bias, and evaluate how those factors may influence their counseling skills, views of clients and interactions with clients, peers and supervisors. One example of a technique that can generate conversation on the aforementioned areas is the genogram (Lim & Nakamoto, 2008). Supervisees can use the genogram to map out their family history, life influences and path to becoming a counselor during a supervision session. Ultimately, the genogram can be used as a tool to assess where supervisees are developmentally and what might have contributed to their worldview and presence as counselors. With any technique used during the supervision process, the goal of increasing awareness is emphasized. Furthermore, supervisees can implement these activities for use with their own clients. Ultimately, supervisors work to facilitate supervisee progression toward being more self-actualized, self-aware counselors. Table 1 provides descriptions of awareness of well-being, developmental characteristics, supervisory descriptors and supervision considerations for each developmental phase.

Table 1

IWM Phases of Supervisee Development

|

Awareness of Well-being

|

Developmental Characteristics

|

Supervisory Descriptors

|

Supervision Considerations

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Phase 1 |

|

Low awareness |

Low independenceIncreased anxietyFollows the lead of others

Low self-efficacy |

SupportiveEducationalStructured |

Live supervisionFeedbackPsychoeducation

Modeling |

| Phase 2 |

|

Pursuit of awareness |

Seeking independenceModerate anxietyMakes attempts to lead

Modest self-efficacy |

Generating awarenessCelebrating successesChallenging |

Advanced skill feedbackChallenge awareness |

| Phase 3 |

|

Increased awareness |

Mostly independentNominal anxietyLeads others

Moderate–high self-efficacy |

Increased mutualityCollaborative |

Active listeningConsultation |

One way supervisors seek to assess supervisees’ developmental phase is through active inquiry. Similar to Young and colleagues’ (2011) recommendations, the assessment of supervisees’ developmental phase is achieved through the use of questioning, reflecting, active listening and challenging incongruences. In addition, direct and intentional questions are used to target specific topics. For example, a supervisor seeking to assess the wellness of a supervisee might ask, “How are you feeling?” and then if there is incongruence, the supervisor might state, “You’re saying that you feel ‘fine,’ but you appear to be anxious tonight.” Based on supervisee reaction, the supervisor can judge the level of awareness the trainee has into his or her own well-being. Additionally, supervisors might want to ask about specific issues such as planned interventions, diagnostic interpretations or theoretical orientation. For example, a supervisor might ask, “How do you plan to assess for suicide?” Then, based on the trainee’s reaction (e.g., asking for help, giving a tentative answer or giving a confident answer) the supervisor can determine his or her developmental phase.

Supervisors also can assess supervisee developmental phase through evaluation. By observing a supervisee in a number of settings (e.g., counseling, triadic supervision, group supervision), supervisors can gauge where he or she is developmentally. Furthermore, observing the supervisee’s counseling skills, professional behaviors and dispositions (Swank, Lambie, & Witta, 2012) can provide increased insight into what phase the supervisee is experiencing at that particular point in time.

Allocation of Supervision Need

The allocation of supervision need is the next process in the IWM of supervision. The supervisor assesses the developmental phase of the supervisee and then provides a supervision intervention (contextual or educational) with the goal of supporting and/or challenging the supervisee (Lambie & Sias, 2009). Phase one of supervisee development is marked by high anxiety, low self-efficacy, decreased awareness of wellness and poor initiative. The supervision environment is one of structure with prescribed activities. Activities to support growth in phase one include live supervision, critical feedback, education on relevant issues, and modeling of behavior and skill.

Gaining insight into trainee wellness also is critical. Supervisors can use insight-oriented activities such as scrapbook journaling, which allows supervisees to gain awareness through the use of multiple media such as photos, music, quotes and poems in the journaling process (Bradley, Whisenhunt, Adamson, & Kress, 2013), or openly discussing the supervisee’s current state of wellness to help foster an increased awareness of it. Supervisees in this developmental phase can be encouraged to explore the five wellness domains (creative self, coping self, social self, essential self, physical self) and begin increasing awareness of their current level of wellness. An example of an activity for assessing supervisee wellness is the starfish technique, which is adapted from Echterling and colleagues’ (2002) sea star balancing exercise. Within this technique, supervisees receive a picture of a five-armed starfish marked with the five wellness constructs (creative, coping, physical, essential, social; Hattie et al., 2004; Myers et al., 2004) and are asked to evaluate the areas that influence or contribute to their overall wellness. Following this, supervisors and supervisees can pursue a discussion regarding the constructs. After the discussion, supervisees redraw the starfish with arm lengths representing the amount of influence that each construct has on their overall wellness or change the constructs into things that they feel better represent their personal wellness. Figure 1 is an example of a supervisee’s initial starfish. Figure 2 is the redrawn wellness starfish based on prioritizing or changing the wellness constructs; this supervisee’s redrawn starfish prioritizes social, physical and creative aspects. In contrast, nutritional and emotional constructs are depicted as smaller arms, indicating areas for growth or a potential imbalance.

Supervisees’ progression to higher levels of development is facilitated through educational and reflective interventions that their supervisors deliver. Phase two of supervisee development is marked by increased autonomy and self-efficacy, decreased anxiety, and attempts to lead or take initiatives. The context of supervision is less concrete and structured but still supportive and encouraging. Supervisees may seek independence, as well as reassurance that they are correct when working through challenges (Borders & Brown, 2005). Supervisors can provide feedback on advanced skills, challenge supervisee awareness and foster opportunities for supervisees to take risks (i.e., challenge, support; Lambie & Sias, 2009). Supervisees in phase two have an increased awareness of their well-being but may be reluctant to integrate support strategies. Therefore, supervisors may integrate activities, assignments or challenges to enhance supervisees’ wellness. For example, supervisors can have supervisees create wellness plans or discuss current wellness plans. Thus, the supervisor can hold the supervisee accountable for personal well-being.

Supervisees in phase three exhibit high autonomy and self-efficacy, low anxiety, and greater efforts to lead (Borders & Brown, 2005). The supervision environment is less structured and the supervisor assumes a consultative role. In addition, the supervisee may serve as a leader by supporting less developed peers. Interventions at this level take the form of consulting on tough cases, working through unresolved issues and providing guidance on advanced skills. Furthermore, supervisees have higher awareness of their wellness and its implications on their work with clients. Finally, supervisees in this phase seek to minimize negative well-being and may need encouragement to overcome this challenge.

Assessment and Matching of Wellness Interventions

Evaluation is a key component of the supervision process (Borders & Brown, 2005) and therefore, wellness, supervisee skill level and supervisor role are assessed in the IWM. A key feature of the IWM is the emphasis on promoting supervisee wellness. Therefore, the IWM emphasizes the evaluation of supervisees and matching of wellness interventions. Furthermore, it is important to assess supervisees’ counseling skills throughout the supervision process to provide formative and summative feedback.

The IWM utilizes the five factors of the indivisible self model (Myers & Sweeney, 2004, 2005) as points of assessment. Furthermore, the development of personal well-being is dependent upon education of wellness, self-assessment, goal planning and progress evaluation (Granello, 2000; Myers, Sweeney, & Witmer, 2000). Therefore, the IWM utilizes these aspects of wellness development as a modality for enhancing supervisee well-being. Supervisees are viewed from a positive, strengths-based perspective in the IWM and thus, activities in supervision should highlight positive attributes, increase understanding of supervisees’ level of wellness and promote knowledge of holistic wellness. Wellness plans (WPs) and the starfish activity are used to assess supervisee wellness by promoting communication and self-awareness in the supervision session. Furthermore, both evaluations are valuable self-assessment measures for supervisees and allow for initial wellness goal setting. WPs should be developed during early supervision sessions and used as a check-in mechanism for formative wellness feedback. Concurrently, the starfish assessment can be used early on to gauge initial wellness and areas for wellness growth.

Progress evaluation is assessed with the 5F-Wel (Myers et al., 2004), a model used to consider factors contributing to healthy lifestyles. The 5F-Wel is a frequently used assessment of wellness and is based on the creative, coping, essential, physical and spiritual self components of the indivisible self model (Myers et al., 2004; Myers & Sweeney, 2005). Supervisees take this assessment during the initial and final sessions to assess their wellness. Myers and Sweeney (2005) have reported the internal consistency of the 5F-Wel as ranging from .89 to .96.

Supervisee counseling skills should be evaluated using a standardized assessment tool. For example, the Counselor Competency Scale (CCS; Swank et al., 2012) can be used as a formative (e.g., midterm or weekly) and summative (e.g., end of semester) assessment of supervisee competencies. In addition, the CCS examines whether supervisees have the knowledge, self-awareness and counseling skills to progress to additional advanced clinical practicum or internship experiences. The CCS assesses supervisee development of skill, professional behavior and professional disposition (Swank et al., 2012). Therefore, supervisors can utilize the CCS to match and support supervisees’ growth by taking on appropriate roles (i.e., teacher, counselor, consultant) to enhance work on specific developmental issues.

Evaluation allows supervisors to monitor supervisee development of career-sustaining mechanisms that enhance well-being, as well as counseling skills, dispositions and professional behaviors. Specifically, the goals of supervisee development are to increase or maintain level of wellness and increase or maintain counseling skills by the end of the supervision process. However, if a supervisee does not improve well-being, the WP should be reevaluated and a remediation plan set so that the supervisee continues to work toward increased wellness. Similarly, if a student does not meet the minimal counseling skill requirements, a remediation plan can be created to support the student’s continued development.

Matching. Supervisors gain a picture of where counseling trainees are developmentally based on the assessment and evaluation process. Then supervisors can match supervisee developmental levels (of skill and wellness) by assuming the appropriate role (i.e., counselor, teacher, consultant) and using the role to provide the appropriate level of support for each trainee. This process allows for individualization of the supervision process and for supervisors to tailor specific events, techniques and learning experiences to the needs of their supervisees. Furthermore, matching supervisee developmental needs and gauging levels of awareness and anxiety allows for appropriate discussions during supervision. Discussing wellness during the latter part of supervision is appropriate for beginning counselors who may be anxious about their skills and work with clients (Borders, 1990) and may not absorb information about their wellness. Each supervisee is an individual, and as a result, it is important to make sure that the supervisee is ready to hear wellness feedback during the supervision session.

IWM: Goals, Strengths and Limitations

The overall goals of the IWM of supervision are for supervisees to increase their wellness, progress through developmental stages and gain counseling skills required to be effective counselors. Additionally, supervisors using the IWM can aid supervisees in increasing wellness awareness via completion of wellness-related assessments (e.g., WPs and starfish technique). Furthermore, supervisors can work to increase supervisees’ self-awareness and professional awareness of counseling issues such as multicultural wellness concerns, the therapeutic alliance, becoming a reflective practitioner, and positive, strengths-based approaches of counseling under the IWM framework.

The IWM is innovative in that it is one of a few supervision models to contain a wellness component. Additionally, the IWM tenets (i.e., wellness, discrimination, development) are empirically supported on individual levels. Furthermore, the IWM includes techniques and assessments for promoting open communication relating to supervisee wellness and counseling skills, and therefore supports supervisory relationships and greater self-awareness, and ultimately allows supervisors to encourage and promote wellness.

As with all models of supervision, the IWM has limitations. Specifically, the IWM may not be applicable to advanced counselors and supervisees. The IWM includes three developmental phases, which are applicable to CITs. In addition, the model may not be as beneficial to supervisees who already have a balanced wellness plan or practice wellness, because the wellness component may be repetitive for such individuals. Additionally, all aspects of the IWM might not be effective or appropriate across all multicultural groups (i.e., races, ethnicities, genders, religions). For example, in relation to wellness, supervisees may not adhere to a holistic paradigm or believe in certain wellness constructs. Lastly, the IWM is in its infancy and empirical evidence directly associated with the integrative prototype does not exist. Nevertheless, supervisors using the IWM can tailor the wellness, developmental and role-matching components to meet specific supervisee needs. The following case study depicts the use of the IWM with a counseling supervisee.

Case Study

Kayla is a 25-year-old female master’s-level counseling student taking her first practicum course. She is excited about the idea of putting the skills she has learned during her program into practice with clients. However, Kayla also is anxious about seeing her first clients and often questions whether she will be able to remember everything she is supposed to do. People tell her she will be fine; however, Kayla questions whether she will actually be able to help her clients.

In addition to the practicum course, Kayla is taking three other graduate courses. She has a full-time job and is in a steady relationship. Family is very important to her, but since beginning her graduate program, she has been unable to find enough time to spend with friends and family. Kayla feels the pull between these areas of her life and struggles to find a balance between family, school, work and her partner.

Kayla is in phase one (i.e., high anxiety); therefore, her supervisor assumes the counselor and teacher roles most often, to match Kayla developmentally. This choice of roles allows Kayla to receive appropriate levels of support and structure to help ease anxiety. During this phase, the supervisor introduces a WP to Kayla and has her complete the 5F-Wel and starfish activity. After discussing the supervisory process and explaining the IWM, Kayla and the supervisor have a conversation about the areas influencing her overall wellness. Based on her starfish results, Kayla is encouraged to develop a WP that coincides with the areas depicted on the starfish, emphasizing those that she wishes to develop further. Additionally, the 5F-Wel provides a baseline of well-being to use in future sessions. Along with the wellness focus, the supervisor explains how imbalance or unwellness influences counselors and, in turn, how it can influence clients.

Initial supervision sessions will continue to provide Kayla with appropriate levels of support and psychoeducation so that she will be able to transition from low awareness to a greater sense of counseling skill awareness and increased mindfulness regarding her overall wellness. If the supervisor and supervisee are able to establish a strong working relationship, it is expected that Kayla will eventually move developmentally into phase two, where she will continue to gain insight into her counseling and wellness, begin to increase her autonomy, and work on increasing self-efficacy.

Implications for Counseling

The IWM integrates developmental and DM supervision tenets with domains of wellness. A supervision model that incorporates wellness is a logical fit in counseling and counselor education, where programs can and should address personal development through wellness strategies for CITs (Roach & Young, 2007). Furthermore, the IWM supports the idea that wellness is important. According to White and Franzoni (1990), CITs often show higher psychological disturbances than the general population. Cummins, Massey, and Jones (2007) highlighted the fact that counselors and CITs often struggle to take their own advice about wellness in their personal lives. Thus, while counseling is theoretically and historically a wellness-oriented field, many counselors are unwell and failing to practice what they preach (Lawson, Venart, Hazler, & Kottler, 2007; Myers & Sweeney, 2005). Implementing the IWM can aid in supporting overall wellness in supervisees as well as educating CITs to practice wellness with their clients and with themselves.

In relation to developmental matching and DM roles, counseling supervisors using the IWM have the following theoretical issues (e.g., Bernard, 1997; Myers et al., 2004; Myers & Sweeney, 2005) to facilitate: supervisee change, skill development, increased self-awareness and increased professional development. The IWM is a holistic, strengths-based model that focuses on supervisee development, matching supervisee needs through supervisor role changing, and wellness to promote knowledgeable, well and effective counseling supervisees.

Conclusion

The IWM is designed to integrate wellness, developmental stages and role matching to allow supervisors to encourage holistic wellness through supervision. Wellness has a positive relationship with counselors’ increased use of career-sustaining mechanisms and increased professional quality of life (Lawson, 2007; Lawson & Myers, 2011). Likewise, increased professional quality of life has been shown to make a positive contribution to counselors’ self-efficacy and counseling service delivery (Mullen, 2014). Therefore, it is logical to promote wellness and career-sustaining behaviors throughout the supervision process.

In summary, the IWM offers a new, integrated model of supervision for use with CITs. Supervisors using the IWM have the unique opportunity to operate from a wellness paradigm, familiarize their supervisees with wellness practices, and monitor supervisees’ wellness and how their wellness influences their client outcomes, while simultaneously supporting supervisee growth, counseling skill development and awareness of professional dispositions.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of

interest or funding contributions for

the development of this manuscript.

References

American Counseling Association. (2014). ACA code of ethics. Alexandria, VA: Author.

Association for Counselor Education and Supervision. (2011). Best practices in clinical supervision. Retrieved from http://www.acesonline.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/ACES-Best-Practices-in-clinical-supervision-document-FINAL.pdf

Aten, J. D., Strain, J. D., & Gillespie, R. E. (2008). A transtheoretical model of clinical supervision. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 2, 1–9. doi:10.1037/1931-3918.2.1.1

Bernard, J. M. (1979). Supervisor training: A discrimination model. Counselor Education and Supervision, 19, 60–68. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.1979.tb00906.x

Bernard, J. M. (1997). The discrimination model. In C. E. Watkins (Ed.), Handbook of psychotherapy supervision (pp. 310–327). New York, NY: Wiley.

Bernard, J. M., & Goodyear, R. K. (2014). Fundamentals of clinical supervision (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Blocher, D. H. (1983). Toward a cognitive developmental approach to counseling supervision. The Counseling Psychologist, 11, 27–34. doi:10.1177/0011000083111006

Borders, L. D. (1990). Developmental changes during supervisees’ first practicum. The Clinical Supervisor, 8, 157–167. doi:10.1300/J001v08n02_12

Borders, L. D. (1992). Learning to think like a supervisor. The Clinical Supervisor, 10, 135–148. doi:10.1300/J001v10n02_09

Borders, L. D., & Brown, L. L. (2005). The new handbook of counseling supervision. New York, NY: Routledge.

Bradley, N., Whisenhunt, J., Adamson, N., & Kress, V. E. (2013). Creative approaches for promoting counselor self-care. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 8, 456–469. doi:10.1080/15401383.2013.844656

Carlson, R. G., & Lambie, G. W. (2012). Systemic-developmental supervision: A clinical supervisory approach for family counseling student interns. The Family Journal, 20, 29–36. doi:10.1177/1066480711419809

Cohen, E. L. (1991). In pursuit of wellness. American Psychologist, 46, 404–408.

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2009). 2009 standards. Retrieved from http://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/2009-Standards.pdf

Cummins, P. N., Massey, L., & Jones, A. (2007). Keeping ourselves well: Strategies for promoting and maintaining counselor wellness. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education and Development, 46, 35–49. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1939.2007.tb00024.x

Dunn, H. L. (1967). High-level wellness. Arlington, VA: Beatty.

Echterling, L. G., Cowan, E., Evans, W. F., Staton, A. R., Viere, G., & McKee, J. (2002). Thriving!: A manual for students in the helping professions. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Ekstein, R., & Wallerstein, R. S. (1972). The teaching and learning of psychotherapy (2nd ed.). New York, NY: International Universities Press.

Granello, P. (2000). Integrating wellness work into mental health private practice. Journal of Psychotherapy in Independent Practice, 1, 3–16. doi:10.1300/J288v01n01_02

Granello, P. F., & Witmer, J. M. (2013). Theoretical models for wellness counseling. In P. F. Granello (Ed.), Wellness counseling (pp. 29–36). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Hattie, J. A., Myers, J. E., & Sweeney, T. J. (2004). A factor structure of wellness: Theory, assessment, analysis, and practice. Journal of Counseling & Development, 82, 354–364. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2004.tb00321.x

Hird, J. S., Cavalieri, C. E., Dulko, J. P., Felice, A. A. D., & Ho, T. A. (2001). Visions and realities: Supervisee perspectives of multicultural supervision. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 29, 114–130. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1912.2001.tb00509.x

Hunt, D. E. (1971). Matching models in education: The coordination of teaching methods with student characteristics. Toronto, Canada: Ontario Institute for Studies in Education.

Johnson, J. A. (1986). Wellness: A context for living. Thorofare, NJ: Slack.

Keyes, C. L. M. (1998). Social well-being. Social Psychology Quarterly, 61, 121–140.

Kottler, J. A. (2010). On being a therapist (4th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Lambie, G. W., & Sias, S. M. (2009). An integrative psychological developmental model of supervision for professional school counselors-in-training. Journal of Counseling & Development, 87, 349–356. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2009.tb00116.x

Lawson, G. (2007). Counselor wellness and impairment: A national survey. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education and Development, 46, 20–34.

Lawson, G., & Myers, J. E. (2011). Wellness, professional quality of life, and career-sustaining behaviors: What keeps us well? Journal of Counseling & Development, 89, 163–171. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2011.tb00074.x

Lawson, G., Venart, E., Hazler, R. J., & Kottler, J. A. (2007). Toward a culture of counselor wellness. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education and Development, 46, 5–19. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1939.2007.tb00022.x

Lenz, A. S., Sangganjanavanich, V. F., Balkin, R. S., Oliver, M., & Smith, R. L. (2012). Wellness model of supervision: A comparative analysis. Counselor Education and Supervision, 51, 207–221. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2012.00015.x

Lenz, A. S., & Smith, R. L. (2010). Integrating wellness concepts within a clinical supervision model. The Clinical Supervisor, 29, 228–245. doi:10.1080/07325223.2020.518511

Lim, S.-L., & Nakamoto, T. (2008). Genograms: Use in therapy with Asian families with diverse cultural heritages. Contemporary Family Therapy: An International Journal, 30, 199–219. doi:10.1007/s10591-008-9070-6

Loganbill, C., Hardy, E., & Delworth, U. (1982). Supervision, a conceptual model. The Counseling Psychologist, 10, 3–42. doi:10.1177/0011000082101002

Luke, M., & Bernard, J. M. (2006). The school counseling supervision model: An extension of the discrimination model. Counselor Education and Supervision, 45, 282–295. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2006.tb00004.x

Maslach, C. (2003). Burnout: The cost of caring. Cambridge, MA: Malor Books.

McNeill, B. W., Stoltenberg, C. D., & Pierce, R. A. (1985). Supervisees’ perceptions of their development: A test of the counselor complexity model. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 32, 630–633. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.32.4.630

Mullen, P. R. (2014). The contribution of practicing school counselors’ self-efficacy and professional quality of life to their programmatic service delivery. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL.

Myers, J. E., Luecht, R. M., & Sweeney, T. J. (2004). The factor structure of wellness: Reexamining theoretical and empirical models underlying the wellness evaluation of lifestyle (WEL) and the Five-Factor Wel. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 36, 194–208.

Myers, J. E., & Sweeney, T. J. (2004). The indivisible self: An evidence-based model of wellness. The Journal of Individual Psychology, 60, 234–244.

Myers, J. E., & Sweeney, T. J. (2005). The indivisible self: An evidence-based model of wellness. (Reprint.). The Journal of Individual Psychology, 61, 269–279.

Myers, J. E., & Sweeney, T. J. (2008). Wellness counseling: The evidence base for practice. Journal of Counseling & Development, 86, 482–493.

Myers, J. E., Sweeney, T. J., & Witmer, J. M. (1998). The wellness evaluation of lifestyle. Palo Alto, CA: Mind Garden.

Myers, J. E., Sweeney, T. J., & Witmer, J. M. (2000). The wheel of wellness counseling for wellness: A holistic model for treatment planning. Journal of Counseling & Development, 78, 251–266. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2000.tb01906.x

Ober, A. M., Granello, D. H., & Henfield, M. S. (2009). A synergistic model to enhance multicultural competence in supervision. Counselor Education and Supervision, 48, 204–221. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2009.tb00075.x

Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (1982). Transtheoretical therapy: Toward a more integrative model of change. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 19, 276–288. doi:10.1037/h0088437

Roach, L. F., & Young, M. E. (2007). Do counselor education programs promote wellness in their students? Counselor Education and Supervision, 47, 29–45. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2007.tb00036.x

Robiner, W. N., Fuhrman, M., Ristvedt, S., Bobbitt, B., & Schirvar, J. (1994). The Minnesota Supervisory Inventory (MSI): Development, psychometric characteristics, and supervisory evaluation issues. The Clinical Psychologist, 47(4), 4–17.

Rogers, C. R. (1957). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 21, 95–103. doi:10.1037/h0045357

Rønnestad, M. H., & Skovholt, T. M. (1993). Supervision of beginning and advanced graduate students of counseling and psychotherapy. Journal of Counseling & Development, 71, 396–405. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.1993.tb02655.x

Rønnestad, M. H., & Skovholt, T. M. (2003). The journey of the counselor and therapist: Research findings and perspectives on professional development. Journal of Career Development, 30, 5–44.

Roscoe, L. J. (2009). Wellness: A review of theory and measurement for counselors. Journal of Counseling & Development, 87, 216–226. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2009.tb00570.x

Smith, H. L., Robinson, E. H. M., III, & Young, M. E. (2007). The relationship among wellness, psychological distress, and social desirability of entering master’s-level counselor trainees. Counselor Education and Supervision, 47, 96–109. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2007.tb00041.x

Stoltenberg, C. D. (1981). Approaching supervision from a developmental perspective: The counselor complexity model. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 28, 59–65.

Stoltenberg, C. D., & McNeill, B. W. (1997). Clinical supervision from a developmental perspective: Research and practice. In C. E. Watkins, Jr. (Ed.), Handbook of psychotherapy supervision (pp. 184–202). New York, NY: Wiley.

Stoltenberg, C. D., & McNeill, B. W. (2010). IDM supervision: An integrative developmental model of supervision (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Stoltenberg, C. D., & McNeill, B. W. (2012). Supervision: Research, models, and competence. In N. A. Fouad (Ed.), APA handbook of counseling psychology: Vol. 1. Theories, research, and methods (pp. 295–327). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Stoltenberg, C. D., McNeill, B. W., & Crethar, H. C. (1994). Changes in supervision as counselors and therapists gain experience: A review. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 25, 416–449. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.25.4.416

Swank, J. M., Lambie, G. W., & Witta, E. L. (2012). An exploratory investigation of the counseling competencies Scale: A measure of counseling skills, dispositions, and behaviors. Counselor Education and Supervision, 51, 189–206. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2012.00014.x

Swarbrick, M. (1997). A wellness model for clients. Mental Health Special Interest Section Quarterly, 20, 1–4.

Vespia, K. M., Heckman-Stone, C., & Delworth, U. (2002). Describing and facilitating effective supervision behavior in counseling trainees. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 39, 56–65. doi:10.1037/0033-3204.39.1.56

White, P. E., & Franzoni, J. B. (1990). A multidimensional analysis of the mental health of graduate counselors in training. Counselor Education and Supervision, 29, 258–267. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.1990.tb01165.x

Williams, E. N., Judge, A. B., Hill, C. E., & Hoffman, M. A. (1997). Experiences of novice therapists in prepracticum: Trainees’, clients’, and supervisors’ perceptions of therapists’ personal reactions and management strategies. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 44, 390–399. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.44.4.390

Witmer, J. M. (1985). Pathways to personal growth. Muncie, IN: Accelerated Development.

Witmer, J. M., & Granello, P. F. (2005). Wellness in counselor education and supervision. In J. E. Myers & T. J. Sweeney (Eds.), Counseling for wellness: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 261–272). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Witmer, J. M., & Sweeney, T. J. (1992). A holistic model for wellness and prevention over the life span. Journal of Counseling & Development, 71, 140–148. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.1992.tb02189.x

Witmer, J. M., & Young, M. E. (1996). Preventing counselor impairment: A wellness approach. The Journal of Humanistic Education and Development, 34, 141–155. doi:10.1002/j.2164-4683.1996.tb00338.x

World Health Organization. (1968). Constitution of the World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland: Author.

Worthen, V., & McNeill, B. W. (1996). A phenomenological investigation of “good” supervision events. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 43, 25–34. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.43.1.25

Young, T. L., Lambie, G. W., Hutchinson, T., & Thurston-Dyer, J. (2011). The integration of reflectivity in developmental supervision: Implications for clinical supervisors. The Clinical Supervisor, 30, 1–18. doi:10.1080/07325223.2011.532019

Ashley J. Blount, NCC, is a doctoral student at the University of Central Florida. Patrick R. Mullen, NCC, is an Assistant Professor at East Carolina University. Correspondence can be addressed to Ashley J. Blount, The Department of Child, Family, and Community Sciences, University of Central Florida, P.O. Box 161250, Orlando, Florida, 32816-1250, ashleyjwindt@gmail.com.

Dec 2, 2014 | Article, Volume 4 - Issue 5

Daniel Cinotti

Recent research has focused on the discrepancy between school counselors’ preferred roles and their actual functions. Reasons for this discrepancy range from administrators’ misperceptions of the role of the school counselor to the slow adoption of comprehensive school counseling approaches such as the American School Counselor Association’s National Model. A look at counseling history reveals that competing professional identity models within the profession have inhibited the standardization of school counseling practice and supervision. School counselors are counseling professionals working within an educational setting, and therefore they receive messages about their role as both counselor and educator. The present article includes a discussion of the consequences of these competing and often conflicting messages, as well as a description of three strategies to combat the role stress associated with this ongoing debate.

Keywords: school counseling, counseling history, professional identity, supervision, educational setting

The profession of school counseling has existed for more than 100 years, and throughout that time, competing professional identity constructs have impacted the roles, responsibilities and supervision of school counselors. Since the inception of school counseling, when it was known as vocational guidance, confusion has existed on how best to use and manage the resource that is the school counselor (Gysbers & Henderson, 2006; Pope, 2009). Although the focus of the profession has changed from vocational guidance to the current concept of comprehensive school counseling, problems surrounding the use and supervision of school counselors persist. Today, although the profession has identified a National Model (American School Counselor Association [ASCA], 2012) that provides an example of a comprehensive programmatic approach, many practicing school counselors and administrators continue to work with outdated service models and reactive approaches (Hatch & Chen-Hayes, 2008; Lambie & Williamson, 2004). A look at the historical roots of school counseling provides insight into the lasting problems for school counselor utilization and supervision.

Historical Context of School Counselor Practice

At the outset of the school counseling profession, the role of vocational guidance slowly became recognized as an integral ingredient in effective vocational placement and training. With the creation of the National Vocational Guidance Association in 1913, and the proliferation of vocational guidance programs in cities such as Boston and New York, the profession rapidly expanded (Gysbers & Henderson, 2006). Concerns over the lack of standardized duties, centralized supervision and evaluation of services soon followed. As Myers (1924) pointed out in a historic article titled “A Critical Review of Present Developments in Vocational Guidance with Special Reference to Future Prospects,” vocational guidance was quickly being recognized as “a specialized educational function requiring special natural qualifications and special training” (p. 139, emphasis in original). However, vocational guidance was mostly being performed by teachers in addition to their other duties, with very few schools hiring specialized personnel. Although Myers (1924) and others expressed concerns over the lack of training and supervision, educators and administrators were slow to recognize the consequences of asking teachers to perform such vital duties in addition to their teaching responsibilities without proper training and extra compensation. Additionally, districts in which specific individuals were hired as vocational guidance professionals soon overloaded these professionals with administrative and clerical duties, which inhibited their effectiveness. Myers (1924) highlighted the situation as follows:

Another tendency dangerous to the cause of vocational guidance is the tendency to load the vocational counselor with so many duties foreign to the office that little real counseling can be done. . . . If well chosen he [or she] has administrative ability. It is perfectly natural, therefore, for the principal to assign one administrative duty after another to the counselor until he [or she] becomes practically assistant principal, with little time for the real work of a counselor. In order to prevent this tendency from crippling seriously the vocational guidance program it is important that the counselor shall be well trained, that the principal shall understand more clearly what counseling involves, and that there shall be efficient supervision from a central office. (p. 141)

In 1913, Jesse B. Davis introduced a vocational guidance curriculum to be infused into English classes in middle and high schools, an idea which he presented at the first national conference on vocational guidance in Grand Rapids, Michigan (Pope, 2009). It was summarily rejected by his colleagues, who would not embrace the idea of a guidance curriculum within the classroom. Slowly, however, as the profession grew and Davis and others gained respect and notoriety throughout the country, his “Grand Rapids Plan” gained support. Though Davis did not expect it, his model sparked debate between those who envisioned the expansion of counselor responsibilities and those who wished to maintain counselors’ primary duty as vocational guidance professionals (Gysbers & Henderson, 2006). Ultimately, the heart of this debate was the role of vocational guidance as a supplemental service to the learning in the classroom or a distinctive set of services with a different goal than simply educating students. Although no definitive answer was agreed upon at the time, the realization that academic factors influence career choice and vice versa has helped to move the profession from a systemic approach of strictly vocational guidance to a comprehensive approach in which career, academic and personal/social development are all addressed (ASCA, 2003). The disagreement over Davis’s Grand Rapids Plan launched a debate between competing professional identity models that continues in the profession to this day.

Competing Professional Identity Models: Educator or Counselor?

Even during the time of vocational guidance in which the counseling profession’s singular purpose was to prepare students for the world of work, disagreement over the best way to perform this duty existed. As the profession began to define itself during the 1930s and ’40s, school administrators heavily determined the professional responsibilities of the school counselor (Gysbers & Henderson, 2006). When the profession expanded to include personal adjustment counseling as a reaction to the growing popularity of psychology, administrators reacted by expanding vocational guidance to include a more educational focus. During the 1950s, school counselors were placed under the umbrella term pupil personnel services along with the school psychologist, social worker, nurse or health officer, and attendance officer. Although the primary role of the school counselor throughout the ’60s and ’70s was to provide counseling services, concerns over the perception of the profession existed. As a result of the lack of defined school counselor roles and responsibilities, the position was still seen as an ancillary support service to teachers and administrators. It was therefore extremely easy for administrators to continue to add to the counselor’s responsibilities as they saw fit (Lambie & Williamson, 2004), aligning school counselor duties with their own identity as educators.

The 1970s brought about the beginning of school counseling as a comprehensive, developmental program. Some within the profession attempted to create comprehensive approaches, which included goals and objectives, activities or interventions to address them, planning and implementation strategies, and evaluative measures. It was the first time that school counseling was defined in terms of developmentally appropriate, measurable student outcomes (Gysbers & Henderson, 2006). However, environmental and economic factors slowed the adoption of this new concept. The 1970s were a decade of decreasing student enrollment and budgetary reductions, which led to cutbacks in counselor positions (Lambie & Williamson, 2004). As a result, counselors began to take on more administrative duties either out of necessity or a desire to become more visible and increase the perception of the school counselor position as necessary. During this time, many of the counseling duties of the position were lost among other responsibilities more aligned with those of an educator.

In 1983, the National Commission of Excellence in Education published “A Nation at Risk,” a report examining the quality of education in the United States (Lambie & Williamson, 2004). Among its initiatives, the report jump-started the testing and accountability movement in education. Standardized testing coordination duties were almost immediately assigned to the counselor. In fact, over the course of the past century in the profession of school counseling, the list of counselor duties and responsibilities has steadily grown to include administrative duties such as scheduling, record keeping and test coordination. With the ever-growing and expanding role of the counselor, and in an attempt to articulate the appropriate responsibilities of the counselor, the concept of comprehensive school counseling programming, which was established in the late 1970s, grew in popularity during the ’80s and ’90s (Gysbers & Henderson, 2006; Mitchell & Gysbers, 1978). As time passed, programs became increasingly articulated and workable, and an emphasis on accountability and evaluation of practice emerged (Gysbers & Henderson, 2001).

Comprehensive School Counseling Programs

What separates comprehensive school counseling from traditional guidance models is a focus on the program and not the position (Gysbers & Henderson, 2006). The pupil personnel services models of the ’60s and ’70s listed the types of services offered but lacked an articulated, systemic approach, and therefore allowed for the constant assignment of other duties to school counselors. The concept of comprehensive programming was created in response to this problem (Gysbers & Henderson, 2006).

As early as 1990, Gysbers offered five foundational premises on which comprehensive school counseling is based. First, school counseling is a program and includes characteristics of other programs in education, including standards, activities and interventions that help students reach these standards; professionally certificated personnel; management of materials and resources; and accountability measures. Second, school counseling programs are developmental and comprehensive. They are developmental in that the activities and interventions are designed to facilitate student growth in the three areas of student development: academic, personal/social and career development (ASCA, 2003). They are comprehensive in that they provide a wide range of services to meet the needs of all students, not just those with the most need. The third premise is that school counseling programs utilize a team approach. Although professional school counselors are the heart of a comprehensive program, Mitchell and Gysbers (1978) established that the entire school staff must be committed and involved in order for the program to successfully take root. The fourth premise is that school counseling programs are developed through a process of systematic planning, designing, implementing and evaluating (Gysbers & Henderson, 2006). This process has been described in different ways but often using the same or similar terminology (Dollarhide & Saginak, 2008). Lastly, the fifth premise offered by Gysbers and Henderson (2006) is that comprehensive school counseling programs have established leadership. A growing message in the school counseling literature is the need for school counselors to provide leadership and advocacy for systemic change (Curry & DeVoss, 2009; McMahon, Mason, & Paisley, 2009; Sink, 2009). Without the knowledge and expertise of school counseling leaders, comprehensive programs will not take hold.

The ASCA National Model

Only within the past decade has the school counseling profession as a whole embraced the concept of comprehensive programs (Dollarhide & Saginak, 2008), a movement which was spurred by ASCA’s creation of a National Model (ASCA, 2003). In 2001, ASCA created the first iteration of its National Model; intended as a change agent, it is a framework for states, districts and counseling departments toward the creation of comprehensive developmental school counseling programs. The ASCA National Model contains four elements, or quadrants, for creating and maintaining effective comprehensive programs (ASCA, 2012). The quadrants are the tools school counselors utilize to address the academic, personal/social and career needs of their students. The first, Foundation, is the philosophy and mission upon which the program is built. The second, Delivery System, consists of the proactive and responsive services included in the program. These services can be focused individually, in small groups or school-wide, and are delivered from—or are at least influenced by—the program’s Foundation and mission statement. The third quadrant, Management, is organization and utilization of resources. Because a comprehensive program uses data to drive its Delivery System, the fourth quadrant is Accountability, which incorporates results-based data and intervention outcomes to create short- and long-term goals for the program (ASCA, 2012; Dollarhide & Saginak, 2008).

The National Model is the most widely accepted conceptualization of a comprehensive school counseling program (Burnham, Dahir, Stone, & Hooper, 2008). It resulted from a movement toward comprehensive programs born out of school counselors’ need to clarify their roles and responsibilities. Beginning with the Education Trust’s (2009) Transforming School Counseling Initiative and continuing with the creation of National Standards for Student Academic, Career and Personal/Social Development, the National Model has been built upon the concepts of social advocacy, leadership, collaboration and systemic change, which are slowly but profoundly shaping the profession (Burnham et al., 2008; Campbell & Dahir, 1997; Dollarhide & Saginak, 2008). Since the release of the National Model, however, the movement toward comprehensive school counseling programs has remained slow (Hatch & Chen-Hayes, 2008). Such slow growth inhibits school counselors from standardizing or professionalizing their roles and responsibilities (Dollarhide & Saginak, 2008).

Consequences of Competing Professional Identity Models

Lambie and Williamson (2004) stated that “based on this historical narrative, school counseling roles have been vast and ever-changing, making it understandable that many school counselors struggle with role ambiguity and incongruence while feeling overwhelmed” (p. 127). While the addition of many responsibilities has been a result of the natural expansion of the profession from vocational guidance to guidance and counseling to comprehensive school counseling, the influence of administrators has directly led to the assignment of inappropriate duties. From the outset of the profession, an essential question has involved these two competing identity models: Should school counselors be acting as educators or counselors?

The historically relevant and often opposing sets of expectations for school counselors come from both counselor educators during training and school administrators (such as principals) upon entering the profession. There is evidence to suggest that school counselors are not practicing as the profession indicates, both in terms of the ASCA National Model and the Education Trust’s Transforming School Counseling Initiative (Clemens, Milsom, & Cashwell, 2009; Hatch & Chen-Hayes, 2008; Scarborough & Culbreth, 2008). Therefore, a common source of role conflict and role ambiguity is the school administrators’ perceptions of the school counselor function, a concern that Myers (1924) established and Lambie and Williamson (2004) reiterated. The concern that school counselors are being used as quasi-administrators instead of counseling professionals continues to persist.

According to ASCA (2012), school counselors are responsible for activities that foster the academic, career and personal/social development of students. The primary role of the school counselor, therefore, is direct service and contact with students. Among the activities ASCA (2012) listed as appropriate for school counselors are individual student academic planning, direct counseling for students with personal/social issues impacting success, interpreting data and student records, collaborating with teachers and administrators, and advocating for students when necessary. Among the activities listed as inappropriate are the following: registration and scheduling; coordinating and administering standardized tests; performing disciplinary actions; covering classes, hallways, and cafeterias; clerical record keeping; and data entry. In terms of role conflict, when faced with a task, school counselors often wish to respond in a manner that is congruent with their counselor identity, but are told to apply another professional identity—namely that of educator. For example, when a school counselor is asked to provide services to a student who has bullied, while also informing the student that he or she has been suspended from school for that behavior, the counselor may experience role conflict. Role ambiguity occurs when some of the duties listed as inappropriate are included as part of the counselor’s responsibilities. For example, if a school counselor is asked to coordinate and proctor state standardized aptitude tests, the counselor experiences role ambiguity, as this duty is noncounseling-related, yet requires a significant time commitment (Culbreth, Scarborough, Banks-Johnson, & Solomon, 2005; Olk & Friedlander, 1992). These examples are but two of many possible scenarios in which the conflicting messages from competing professional identity orientations contribute to role stress for practicing school counselors.

Strategies for Addressing Competing Models

Within the recent literature on school counseling, many articles highlight the differences between school counselors’ preferred practice models and actual functioning (Burnham & Jackson, 2000; Culbreth et al., 2005; Lieberman, 2004; Scarborough & Culbreth, 2008), as well as between administrators’ view of the role of the school counselor and models of best practice within the profession (Clemens et al., 2009; Kirchner & Setchfield, 2005; Zalaquett & Chatters, 2012). However, these discrepancies were identified virtually from the outset of the profession (Ginn, 1924; Myers, 1924) and can be attributed in large part to the different orientations encountered by counseling professionals working in educational settings. Despite the concept of comprehensive school counseling and the creation of a National Model delineating appropriate roles and responsibilities, the reality is that school counselors utilize different service models depending on the region, state, district and even school in which they work. From a historical perspective, it is clear that administrators often impose their identity as educators on school counselors through the assignment of noncounseling duties. However, it is also clear that school counselors themselves have been unsuccessful in advocating for the use of current best practices. Ironically, strategies to prevent counselors from becoming quasi-administrators were identified as early as 1924.

Myers (1924) not only identified the risk for counselors to be overloaded with administrative duties, but also listed three strategies that could be used to combat this possibility. First, he suggested that “counselor[s] shall be well trained” (p. 141). This suggestion is especially important for counselor educators, who are responsible for training future counselors and acting as gatekeepers to the profession. In addition to relevant theories, techniques and practices in individual and group counseling and assessment, it is clear that school counselors-in-training also need enhanced knowledge and skill in advocacy. In order to achieve these goals, critical thought is necessary regarding school counselors’ handling of the role stress created by competing professional identity models. Emphasizing the importance of maintaining a strong relationship with administrators also is critical, as history has suggested. Furthermore, comfort and enthusiasm in gathering and using data to provide evidence of effectiveness are essential skills. In short, in addition to preparing knowledgeable and skilled counselors, counselor educators are charged with preparing leaders and advocates; they should approach their work with school counselors-in-training with this intention.

Myers’ (1924) next suggestion was that “principal[s] shall understand more clearly what counseling involves” (p. 141). As the literature suggests, school counselors and administrators share responsibility because of the inherent difference in their orientations. For administrators and others who supervise school counselors, it is important to understand that the training and professional identity of a school counselor is different from that of an educator, and that counselors are trained to address not only academic issues, but career and personal/social issues as well. Without this understanding, it is easy to impose inappropriate models of supervision and noncounseling-related activities on the counselor. It is necessary for practicing counselors to develop a strong sense of professional identity beginning in their training program. For some counselors, it is difficult to differentiate appropriate from inappropriate roles and responsibilities. This process is complicated for the many counselors who are former teachers and have been trained as both educators and counselors. However, it is essential to be able to articulate to administrators and other stakeholders the role of the counselor in maximizing student success. Practicing school counselors should portray themselves as counseling experts with the ability to create and maintain a developmentally appropriate and comprehensive program of services as defined by Gysbers and Henderson (2006). Knowledge of the ASCA National Model and other relevant state models aids in the practicing counselors’ ability to position themselves as counseling professionals and to articulate their appropriate roles as such.

Myers’ (1924) final suggestion was that “there shall be efficient supervision from a central office” (p. 141). Supervision can be provided by building administrators, district directors of school counseling or even experienced colleagues. Practicing school counselors can receive three distinct types of supervision: administrative, program and clinical. Administrative supervision is likely to occur, as it is provided by an assigned individual—usually a principal, vice principal or other administrator (Lambie & Sias, 2009). Program supervision, because it is related to comprehensive school counseling, is often present only if the district, school or counseling department adopts a comprehensive, programmatic approach (Dollarhide & Saginak, 2008). Clinical supervision is perhaps the rarest of the three (Somody, Henderson, Cook, & Zambrano, 2008), and the most necessary, because it impacts counseling knowledge and skills, and decreases the risk of unethical practice (Bernard & Goodyear, 2009; Lambie & Sias, 2009).