Sep 13, 2024 | Volume 14 - Issue 2

Sapna B. Chopra, Rebekah Smart, Yuying Tsong, Olga L. Mejía, Eric W. Price

This mixed methods program evaluation study was designed to assist faculty in better understanding students’ multicultural and social justice training experiences, with the goal of improving program curriculum and instruction. It also offers a model for counselor educators to assess student experiences and to make changes that center social justice. A total of 139 first-semester students and advanced practicum students responded to an online survey. The Consensual Qualitative Research-Modified (CQR-M) method was used to analyze brief written narratives. The Multicultural Counseling Competence and Training Survey (MCCTS) and the Advocacy Competencies Self-Assessment Survey (ACSA) were used to triangulate the qualitative data. Qualitative findings revealed student growth in awareness, knowledge, skills, and action, particularly for advanced students, with many students reporting a desire for more social justice instruction. Some students of color reported microaggressions and concerns that training centers White students. Quantitative analyses generally supported the qualitative findings and showed advanced students reporting higher multicultural and advocacy competencies compared to beginning students. Implications for counselor education are discussed.

Keywords: social justice, program evaluation, training, multicultural counseling, counselor education

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic and the long-standing inequities it brought to light, many universities began examining the ways that injustice unfolds within their institutions (Mull, 2020). Arredondo et al. (2020) noted that counseling and counselor education continue to uphold white supremacy and center the experiences of White people within theories, training, and research. White supremacy culture promotes Whiteness as the norm and standard, intersects with and reinforces other forms of oppression, and shows up in institutions in both overt and covert ways, such as emphasis on individualism, avoidance of conflict, and prioritizing White comfort (Okun, 2021). Arredondo et al. (2020) called for counselor educators to engage in social justice advocacy and to unpack covert White supremacy in training programs. The present study investigated the multicultural and social justice training experiences of students in a Western United States counseling program so that counseling faculty can be empowered to uncover biases and better integrate social justice in the curriculum.

Counselor education programs are products of the larger sociopolitical environment and dominant patriarchal, cis-heteronormative, Eurocentric culture that often fails to “challenge the hegemonic views that marginalize groups of people” which “perpetuate deficit-based ideologies” (Goodman et al., 2015, p. 148). For example, the focus on the individual in traditional counseling theories can reinforce oppression by failing to address the role of systemic oppression in a client’s distress (Singh et al., 2020). Counseling theory textbooks usually provide an ancillary section at the end of each chapter focusing on multicultural issues (Cross & Reinhardt, 2017). White supremacy culture is so ubiquitous that it is typically invisible to those immersed within it (DiAngelo, 2018). It is not surprising then that counseling is often viewed as a White, middle-class endeavor, and BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) clients frequently perceive that they should leave their cultural identities and experiences outside the counseling session (Turner, 2018). Counselor educators have been encouraged to reflect on how Eurocentric curricula and pedagogy may marginalize students and seek liberatory teaching practices that promote critical consciousness (Sharma & Hipolito-Delgado, 2021).

Students’ Perceptions of Their Growth, Learning Process, and Critiques of Their Training

Studies of mostly White graduate students show gains in expanding awareness of their own biases and privilege, knowledge about other cultures and experiences of oppression, as well as the importance of empowering and advocating for clients (Beer et al., 2012; Collins et al., 2015; Sanabria & DeLorenzi, 2019; Singh et al., 2010). Others indicated the benefits of integrating feminist principles in treatment (Hoover & Morrow, 2016; Singh et al., 2010). Consciousness-raising and self-reflection were key parts of multicultural and social justice learning (Collins et al., 2015; Hoover & Morrow, 2016), and could be emotionally challenging. Indeed, Goodman et al. (2018) identified a theme of internal grappling reflecting students’ experiences of intellectual and emotional struggle; others noted students’ experiences of overwhelm and isolation (Singh et al., 2010), as well as resistance, such as withdrawing or dismissing information that challenged their existing belief system (Seward, 2019). Researchers have also documented student complaints about their social justice training; for example, that social justice is not well integrated or that there was inadequate coverage of skills and action (Collins et al., 2015). Kozan and Blustein (2018) found that even among programs that espouse social justice, there was a lack of training in macro level advocacy skills. Barriers to engaging in advocacy included: lack of time (Field et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2010), emotional exhaustion stemming from observations of the harms caused by systemic inequities (Sanabria & DeLorenzi, 2019), and ill-informed supervisors (Sanabria & DeLorenzi, 2019).

The studies reviewed thus relied on samples of mainly White, cisgender, heterosexual women. Some noted that education on social justice is often centered on helping White students expand their awareness (Haskins & Singh, 2015). In one study focused on challenges faced by students of color, participants expressed frustration with the lack of diversity among their professors, classmates, and curriculum (Seward, 2019). Participants also experienced marginalization and disconnection when professors and students made offensive or culturally uninformed comments and when course content focused on teaching students with privileged identities. Students from marginalized communities also face isolation in academic settings and sometimes question the multicultural competence of their professors (Haskins & Singh, 2015), which in turn contributes to the underrepresentation of students of color in counseling and psychology (Arney et al., 2019).

The Present Study

Counselor educators must critically examine their curriculum, course materials, and overall learning climate for students (Haskins & Singh, 2015). Listening to students’ experiences and perceptions of their training offers faculty an opportunity to model cultural humility, gain useful feedback, and make necessary changes. Given the increased recognition of racial trauma and societal inequities, it is critical that counseling programs engage with students of diverse backgrounds as they seek to shift their pedagogy. Historically, academic institutions have responded to student demands with performative action rather than meaningful change (Zetzer, 2021). This mixed methods study is part of a larger process of counseling faculty working to invite student feedback and question internalized assumptions and biases in order to implement real change. The goal of program evaluation is to investigate strengths and weaknesses in order to improve the program (Royse et al., 2010). According to the 2024 Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) standards, program evaluation is essential to assess and improve the program (CACREP, 2023). Thus, the purpose of this program evaluation study was to understand students’ self-assessment and experiences with the counseling program’s curriculum in the area of multicultural and social justice advocacy, with the overarching goal of program curriculum and instruction improvement. This article offers counselor educators a model of how to assess program effectiveness in multicultural and social justice teaching and practical suggestions based on the findings. The research questions were: What are beginning and advanced students’ self-perceptions regarding their multicultural and social justice advocacy competencies? What are beginning and advanced students’ perceptions of the multicultural and social justice advocacy competencies training they are receiving in their program?

Method

We employed a mixed method, embedded design in which the quantitative data offered a supportive and secondary role to the qualitative results (Creswell et al., 2003). Qualitative and mixed methods research designs are particularly useful in program evaluation (Royse et al., 2010). Mixed method approaches also offer value in research that centers social justice advocacy, as the integration of diverse methodological techniques within a single study fosters the understanding of multiple perspectives and facilitates a deeper comprehension of intricate issues (Ponterotto et al., 2013). We used an online survey to collect written narratives (qualitative) and survey data (quantitative) from two counseling courses: a beginning counseling course in the first semester (beginning students), and an advanced practicum course, taken by those who had completed at least part of their year-long practicum (advanced students).

Participants

Participants were counseling students enrolled in a CACREP-accredited program at a large West Coast public university in the United States that is both a federally designated Hispanic-serving institution and an Asian American and Native American Pacific Islander–serving institution. Responses were collected from two courses, which included 94 beginning students (84% response rate) and 62 advanced students (71% response rate). Twelve percent of the advanced practicum students also completed the survey when they were first-semester (beginning) students. The mean age of the 139 participants was 27.7 (SD = 7.11), ranging from 20 to 58 years. Racial identifications were 40.3% White, 33.1% Latinx, 14.4% Asian, 7.2% Biracial or Multiracial, 2.9% Black, 0.7% Middle Eastern, 0.7% American Indian/Alaska Native, and 0.7% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. The majority identified as women (82.0%), followed by 14.4% as men, and 2.9% as nonbinary/queer. Students self-identified as heterosexual (71.2%), bisexual (11.5%), lesbian/gay (6.5%), queer (4.3%), pansexual (1.4%), and about 1% each as asexual, heteroflexible, and unsure. About 19.4% of students were enrolled in a bilingual/bicultural (Spanish/Latinx) emphasis within the program.

Procedure

After receiving university IRB approval, graduate students enrolled in the first-semester beginning counseling course (fall 2018 and 2019) or the advanced practicum course (summer 2019 and 2020) were asked to complete an online survey through Qualtrics with both quantitative measures and open-ended questions as part of their preparation for class discussion. Students were informed that this homework would not be graded and was not intended to “test” their knowledge but rather would serve as an opportunity to reflect on their experience of the program’s multicultural and social justice training. Students were also given the option to participate in the current study by giving permission for their answers to be used. Those who consented were asked to continue to complete the demographic questionnaire. In accordance with the American Counseling Association Code of Ethics (2014), students were informed that there would be no repercussions for not participating. A faculty member outside the counseling program managed the collection of and access to the raw data in order to protect the identities of the students and ensure that their participation or lack of participation in the study could not affect their grade for the course or standing in the program. All students, regardless of participation status, were given the option to enter an opportunity drawing for a small cash prize ($20 for data collection in 2018 and 2019, $25 for 2020) through a separate link not connected to their survey responses.

Data Collection

We collected brief written qualitative data and responses to two quantitative measures from both beginning and advanced students.

Qualitative Data

The faculty developed open-ended questions that would elicit student feedback on their multicultural and social justice training. Prior to beginning the counseling program, first-semester students were asked two questions about their experiences and impressions: How would you describe your knowledge about and interest in multiculturalism/diversity and social justice from a personal and/or academic perspective? and How would you describe your initial impressions or experience of the focus on multicultural and social justice in the program so far? They were also asked, if it was relevant, to include their experience in the Latinx counseling emphasis program component. Advanced students, who were seeing clients, were asked the same questions and also asked to: Consider/describe how this experience of multiculturalism and social justice in the program may impact you personally and professionally (particularly in work with clients) in the future.

Quantitative Data

Two instruments were selected to quantitatively assess students’ perceptions of their own multicultural and advocacy competencies. The Multicultural Counseling Competence and Training Survey (MCCTS; Holcomb-McCoy & Myers, 1999) is designed to assess counselors’ perceptions of their multicultural competence and the effectiveness of their training. The survey contains 32 statements for which participants answer on a 4-point Likert scale (not competent, somewhat competent, competent, extremely competent). Sample items include: “I can discuss family therapy from a cultural/ethnic perspective” and “I am able to discuss how my culture has influenced the way I think.” The reliability coefficients for each of the five components of the MCCTS ranged from .66 to .92: Multicultural Knowledge (.92), Multicultural Awareness (.92), Definitions of Terms (.79), Knowledge of Racial Identity Development Theories (.66), and Multicultural Skills (.91; Holcomb-McCoy & Myers, 1999). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranged from .75 to .96.

The Advocacy Competencies Self-Assessment Survey (ACSA; Ratts & Ford, 2010) assesses for competency and effectiveness across six domains: (a) client/student empowerment, (b) community collaboration, (c) public information, (d) client/student advocacy, (e) systems advocacy, and (f) social/political advocacy. It contains 30 statements that ask participants to respond with “almost always,” “sometimes,” or “almost never.” Sample questions include “I help clients identify external barriers that affect their development” and “I lobby legislators and policy makers to create social change.” Although Ratts and Ford (2010) did not provide psychometrics of the original ACSA, it was validated with mental health counselors (Bvunzawabaya, 2012), suggesting an adequate internal consistency for the overall measure, but not the specific domains. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranged from .69 to.79 for the six domains, and .94 for the overall scale. For the purposes of this study, we were not interested in specific domains and used the overall scale to assess students’ overall social justice/advocacy competencies.

Data Analysis

Qualitative Data Analysis

To analyze the qualitative data, we used Consensual Qualitative Research-Modified (CQR-M; Spangler et al., 2012), which was based on Hill et al.’s (2005) CQR but modified for larger numbers of participants with briefer responses. In contrast to the in-depth analysis of a small number of interviews, CQR-M was ideal for our data, which consisted of brief written responses from 139 participants. CQR-M involves a consensus process rather than interrater reliability among judges, who discuss and code the narratives, and relies on a bottom-up approach, in which categories

(i.e., themes) are derived directly from the data rather than using a pre-existing thematic structure. Frequencies (i.e., how many participants were represented in each category) are then calculated. We analyzed the beginning and advanced students’ responses separately, as the questions were adjusted for their time spent in the program.

After immersing themselves in the data, the first two authors, Sapna B. Chopra and Rebekah Smart, met to outline a preliminary coding structure, then met repeatedly to revise the coding into more abstract categories and subcategories. The computer program NVivo was used to organize the coding process and determine frequencies. After all data were coded, the fifth author, Eric W. Price, served as auditor and provided feedback on the overall coding structure. Both the consensus process and use of an auditor are helpful in countering biases and preconceptions. Brief quantitative data, as used in this study, can be used effectively as a means of triangulation (Spangler et al., 2012).

Quantitative Data Analysis

To examine for significant differences in the self-perceptions of multicultural competencies and advocacy competencies between White and BIPOC students as well as between beginning and advanced students, a two-way (2×2) ANOVA was conducted with the overall MCCT as the criterion variable and student levels (beginning, advanced) and race (White, BIPOC) as the two independent variables. In addition, two (5×2) multivariate analyses of variances (MANOVAs) were conducted with the five factors of multicultural competencies (knowledge, awareness, definition of terms, racial identity, and skills) as criterion variables and with student levels (beginning, advanced) and student races (White, BIPOC) as independent variables in each analysis. Data for beginning and advanced students were analyzed separately to assess whether time in the counseling program helped to expand their interest and commitment to social justice.

Research Team

We were intentional in examining our own social identities and potential biases throughout the research process. Chopra is a second-generation South Asian American, heterosexual, cisgender woman. Smart is a White European American, heterosexual, cisgender woman. Yuying Tsong identifies as a genderqueer first-generation Taiwanese and Chinese American immigrant. Olga L. Mejía is an Indigenous-identified Mexican immigrant, bisexual, cisgender woman. Price is a White, gay, cisgender male. All have experience as counselor educators and in qualitative research methods, and all have been actively engaged in decolonizing their syllabi and incorporating multicultural and social justice into their pedagogy.

Results

The research process was guided by the overarching question: What are beginning and advanced counseling students’ perceptions of their multicultural and social justice competencies and training and how can their feedback be used to improve their counselor education program? We explore the qualitative findings first, as the primary data for the study, followed by the quantitative data.

Qualitative Findings for Beginning Counseling Students

Two higher-order categories emerged from the beginning students’ narratives: developing competencies and learning process so far.

Developing Competencies

Students’ descriptions of the competencies they were developing included themes of awareness, knowledge, and skills and action. Some students entered the program with an already heightened awareness, while others were making new discoveries. Awareness included subthemes of humility (24.5%), awareness of own privilege (6.4%), and awareness of bias (3.2%). “There’s a lot to learn” was a typical sentiment, particularly from White students. One White female student wrote: “I definitely need more and I believe that open discussions, even hard ones would be some of the best ways to go about this.” A large group expressed knowledge of oppression and systemic inequities (33%); a smaller group referenced intersectionality (3.2%). Within skills and action, some students expressed specific intentions in allyship (11.7%); a number of students expressed commitment to social action but felt unsure how to engage in social justice (11.7%).

Learning Process So Far

Central themes in this category were support for growth, concerns in training, and internal challenges. Some students felt excited and supported, while some were cautiously optimistic or concerned. Support for growth was a strong theme that reflected excited and enthusiastic to learn (22.3%); appreciation for the Latinx emphasis (18.1%); and receiving support from professors and program (17.0%). For example, one Mexican student in the Latinx emphasis who noted that mental health was rarely discussed in her family shared: “For me to see that there is a program that teaches students how to communicate to individuals who are unsure of what counseling is about, gave me a sense of happiness and relief.”

A few students were adopting a wait-and-see attitude and expressed some concerns about their training. Although the percentage for these subthemes is low, they provide an important experience that we want to amplify. This theme had multiple subthemes. The subtheme concerns from students of color included centering White students (3.2%), microaggressions (3.2%), and lack of representation (1.1%). A student who identified as a Mexican immigrant shared experiences of microaggressions, including classmates using a hurtful derogatory phrase referring to immigrants with no comment from the professor until the student raised the issue. Concerns in training also included the subtheme concerns with how material is presented in classes (7.0%). For some, the concern related to the potential for harm in classes in which White and BIPOC students were encouraged to process issues of privilege and oppression. For example, one Asian Pacific Islander student wrote that although they appreciated the emphasis on social justice, “Time always runs out and I believe it’s careless and dangerous to cut off these types of conversations in a rushed manner.” A small minority seemed to suggest a backlash to the emphasis on social justice, stating that the content was presented in ways that were too “politically correct,” “biased,” or “repetitive.”

Multiple subthemes emerged from the theme of internal challenges. Both BIPOC and White students shared feeling afraid to speak up (5.3%). BIPOC students expressed struggling with confidence or wanting to avoid conflict, while White students’ fear of speaking up was also connected to discomfort and uncertainty as a White person (2.1%). A small minority of White students did not express explicit discomfort but seemed to engage in a color-blind strategy, as indicated in the theme of people are people (2.1%): “I find people are people, regardless of any differences, and love hearing the good and bad about everybody’s experiences.” Some students of color expressed limited knowledge about cultures other than one’s own (4.3%). For example, an Asian American student stated that they had gravitated to “those who were most similar to me” growing up. Lastly, a few students shared feeling overwhelmed and exhausted (3.2%).

Qualitative Findings for Advanced Counseling Students

Four higher-order themes emerged: competencies in process, multiculturalism and diversity in the program, social justice in the program, and the learning process.

Competencies in Process

Similar to beginning students, advanced students described growing self-awareness, knowledge and awareness of others, skills, and action. Their disclosures often related to clinical work, now that they had been seeing clients. Self-awareness included strong subthemes of: humility and desire to keep learning (25.8%); increased open-mindedness, acceptance of others, and compassion (22.6%); awareness of personal privilege and oppression (17.7%); awareness of personal bias and value systems (17.7%); and awareness of personal cultural identity (14.5%). One Mexican American student wrote: “I have also gained an increased awareness of how my prejudices can impact my work with clients and learned about how to check-in with myself.”

Knowledge and awareness of others had subthemes of privilege and oppression (19.4%) and increased knowledge of culture (14.5%), with awareness of the potential impact on clients. The advanced students also had more to say about skills, which included subthemes of diversity considerations in conceptualization (29%), and in treatment (12.9%), and cultural conversations in the therapy room (21%). One White student wrote: “I have been able to have difficult conversations that once were unheard of. I have also been able to bring culture, ethnicity, and oppression into the room so that my clients can feel understood and safe.” Within the theme of action, 52% wrote about their commitment to social justice and intention to advocate. Although this strongest subtheme suggested action was still more aspirational than currently enacted, a smaller group also wrote about the experiences that they have already had with client advocacy (12.9%), community and/or political action (12.9%), and unspecified action (11.3%).

Multiculturalism and Diversity in the Program

Many students (44%) indicated that they appreciated that multicultural issues were integrated or addressed well within the program. However, with more time spent in the program, 26% felt that there was more nuance, depth, or scope needed. Some wanted more attention to specific issues, such as disability, gender identity, and religion/spirituality. One Asian American student wrote that the focus had been “basic and surface-level,” adding “I feel like it has also generally catered to the protection of White feelings and voices, which is inherently complicit in the system of White supremacy, especially in higher ed.” Others (9.7%) said more training in clinical application was needed.

Social Justice in the Program

Students expressed a variety of opinions. The largest number (29%) were satisfied that social justice issues were well integrated into the program. Although more students were satisfied than not, many (24%) noted that social justice is addressed but not demonstrated. Similarly, 24% noted minimal attention, specifically that social justice was not addressed much beyond the one course focused on culture, and 24% noted a desire for more opportunities within the program to engage in advocacy. Some suggested requiring social justice work rather than leaving it as an optional activity. Others (13%), mostly from 2020, noted the relevance of current events and sociopolitical climate. One White student shared about a presentation on Black Lives Matter: “This project opened my eyes to my limited knowledge of systemic oppression in the U.S. and impacted me in ways that I will NEVER be the same.” A small number of students (3%) reported that there was no need or room for more training in social justice. One White student wrote that they felt “frustrated” and that the social justice “agenda is so in my face all the time,” adding “sometimes I feel like I am being trained to be an advocate and an activist, which is/are a different job.”

The Learning Process

Three central themes emerged: enrichment experienced, challenges, and suggestions for change. Many students were appreciative of their experience. A strong subtheme within enrichment experienced was professors’ encouragement and modeling (24%). Others commented on how much came from learning from peers (21%). Some shared feeling personally empowered (14.5%). For example, a student who identified as coming from an Asian culture wrote about the hesitancy to be an activist, stating, “There is an underlying belief that our voices will not really ever be heard which is strongly tied to systemic oppression and racism throughout history. Consequently, I appreciate this challenge to grow more in social justice issues.” Others shared ways that the program prompted them to engage in social justice outside the classroom (11.3%). For example, one student wrote: “This program gave me the knowledge and education I needed to make sure that when I did speak out I wasn’t just talking to talk. I would actually have facts, stats, evidence-based research to back up my argument.” A number of students noted the unique benefits of the Latinx program (9.7%). One Mexican American student reflected that they had learned about diversity within Latinx cultures, and that, “As a result, I feel more confident in being able to serve clients from various Latinx cultures or at least know where to obtain relevant information when needed.” Many students expressed a sense of belonging (8.1%).

Challenges. Nearly 10% wrote about struggling to make time [for social justice] and 6.5% noted the emotional impact. For example, one White student wrote: “It was a rude and brutal awakening, to say the least. It was riddled with emotion and heartache but was worth the process.” A few had conflicted or mixed feelings (8.1%)—they felt appreciative but wanted more. A few noted possible harm to marginalized students (6.5%). One Asian American student wrote that faculty should be “calling out microaggressions . . . otherwise, their stance on social justice feels more performative and about protecting their own liability rather than caring for their students of color.” A smaller number (4.8%) struggled with peers and colleagues who seemed uninformed.

Suggestions for Change. Students offered suggestions for improvement, with a strong theme to develop more diverse representation (16.1%), including more representation in faculty, students, case examples, and class discussions. Some comments were specifically about needed attention to Black experiences; one concerned teaching about resiliencies and strengths in the face of oppression. Almost 15% suggested making changes to courses or curriculum. One White student wrote: “If it were me running the program (lol) I would . . . remove the culture class and have all those topics embedded into the fabric of each class because culture and diversity are in all those topics.” A few suggested that faculty require social justice assignments (8.1%), adding that many students will not act unless required. A few also suggested that the program provide more education of White students (8.1%).

Quantitative Findings

Quantitative analyses were conducted to provide triangulation for the qualitative findings and a different view of the data, including possible differences between BIPOC and White students and beginning and advanced students. Table 1 includes descriptive statistics providing an overview of beginning and advanced students’ self-perception of their multicultural and social justice competencies.

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics of Competencies

|

|

|

Multicultural |

Social Justice/Advocacy |

|

|

N |

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

| White |

Beginning |

35 |

2.58 |

.50 |

62.97 |

24.23 |

| Advanced |

27 |

3.09 |

.38 |

76.07 |

19.11 |

| Total |

62 |

2.80 |

.52 |

68.68 |

22.93 |

| BIPOC |

Beginning |

59 |

2.66 |

.56 |

63.05 |

29.30 |

| Advanced |

35 |

3.01 |

.30 |

77.14 |

20.71 |

| Total |

94 |

2.79 |

.51 |

68.30 |

27.19 |

| Total |

Beginning |

94 |

2.63 |

.54 |

63.02 |

27.39 |

| Advanced |

62 |

3.05 |

.34 |

76.68 |

19.87 |

| Total |

156 |

2.80 |

.51 |

68.45 |

25.51 |

To examine if there were discernable differences between the beginning and advanced students’ perceptions of their competencies, and if there were differences between White and BIPOC students, a two-way (2×2) ANOVA was conducted with the overall MCCT as the criterion variable and student levels (beginning, advanced) and race (White, BIPOC) as the two independent variables. Results indicated that although there were no interaction effects between race and student levels, there were significant differences in overall multicultural competencies between beginning and advanced students, F(1, 152) = 30.54, p < .001, indicating that advanced practicum students reported significantly higher overall multicultural competencies than beginning students. There were no statistically significant differences between White and BIPOC students in their overall multicultural competencies. Two (5×2) MANOVAs were conducted with the five factors of multicultural competencies as criterion variables (knowledge, awareness, definition of terms, racial identity, and skills). Student levels (beginning, advanced) and student race (White, BIPOC) were independent variables. Results indicated that there were significant differences between beginning and advanced students in at least one of the multicultural competencies components, Wilks’ Lambda = .72, F(5, 150) = 11.97, p < .001. More specifically, follow-up univariate ANOVAs indicated that advanced students reported significantly higher multicultural competencies in their knowledge, F(1, 154) = 43.74, p < .001, µ2 = .22; awareness, F(1, 154) = 6.20, p = .014, µ2 = .04; and racial identity, F(1, 154) = 43.17, p < .001, µ2 = .21. However, there were no significant differences in definitions of terms or skills. Even though there were no significant differences between White and BIPOC students in their overall multicultural competencies, the results of the 5×2 MANOVA indicated that there were significant differences in at least one of the components, Wilks’ Lambda = .87, F(5, 150) = 4.49, p = .001. Follow-up univariate ANOVAs indicated that White students reported higher multicultural competencies in racial identity than BIPOC students in this study, F(1, 154) = 4.51, p = .035, µ2 = .03. There were no differences in the other areas.

A two-way (2×2) ANOVA was conducted with the overall ACSA as the criterion variable and student levels (beginning, advanced) and race (White, BIPOC) as the two independent variables. Results indicated that while there were no interaction effects between race and student levels, there were significant differences in overall advocacy competencies between beginning and advanced students, F(1, 152) = 10.78, p = .001, indicating that advanced students reported significantly higher overall advocacy competencies (M = 76.68) than beginning students (M = 63.02). There were no statistically significant differences between White and BIPOC students in their overall advocacy competencies.

Discussion

This study was designed to examine students’ experiences of their multicultural and social justice training as an aspect of program evaluation, specifically to assist faculty in improving curriculum and instruction with regard to multicultural and advocacy competencies; the study also offers a unique contribution to existing literature by including a more racially diverse (60% BIPOC) sample. Students reported growth in the core areas of multicultural and social justice competency as outlined by Ratts et al. (2016): awareness, knowledge, skills, and action. Consistent with Field et al.’s (2019) findings, students reported more growth in awareness and knowledge than in social justice action, with some differences as students moved through the program. Although beginning students identified personal biases, the theme of self-awareness was more complex for them later in the program. This suggests that a longer time spent in the program contributed to personal growth; although this seems expected, these outcomes have not necessarily been examined before and confirm that the programs’ increasing effort on multiculturalism and social justice are showing gains. The advanced students wrote about clinical application as well and made overt statements of their commitment to social justice. The quantitative results supported these qualitative findings, with advanced students reporting higher multicultural competencies in knowledge, awareness, and racial identity and higher overall advocacy competencies compared to beginning students. With one exception, there were no significant differences between White and BIPOC students in their self-assessment of multicultural or advocacy competencies. Across racial groups, students expressed humility and desire to learn more.

Although students expressed mixed opinions about their experience of the multicultural and social justice training, a greater number of advanced students reported that they thought multicultural (44%) and social justice issues (30%) were well integrated into the program compared to the number of students with critiques. Students reported that support from faculty and peers facilitated their growth and learning, consistent with previous research (e.g., Beer et al., 2012; Keum & Miller, 2020). Some students noted a sense of belonging, particularly those in the Latinx emphasis.

Similar to other researchers, we found that many students wanted social justice issues to be integrated across the curriculum rather than into one course (Beer et al., 2012; Collins et al., 2015); they also wanted more focus on skills and action (Collins et al., 2015; Kozan & Blustein, 2018). Students’ scores on the ACSA advocacy competencies scale reflect this gap in training as well. Though fewer students offered critiques of their training, these responses are important to amplify because some of these concerns are rarely solicited or acknowledged. For example, BIPOC students echoed the challenges faced by students in Seward’s (2019) study, including lack of representation in their faculty, classmates, and curriculum as well as feelings of marginalization when microaggressions in the classroom went unchecked and when instruction centered the needs of White students. Additionally, a few advanced students from 2020, during a time of significant racial-sociopolitical uprising in the United States, expressed concern that class discussions potentially caused harm to students from marginalized communities. Though more students expressed a desire for greater in-depth training, a small minority of mostly White students indicated that they did not want more social justice training and would rather focus solely on traditional counseling skills. These different student perspectives point to the challenges of teaching social justice amidst diverse political and ideological backgrounds and the need to increase community and collaboration.

Listening to Student Feedback and Implications for Decolonizing Program Curriculum

This study’s findings support the benefits of listening to students’ voices related to multicultural and social justice to inform counselor educators on program strengths and areas for growth. Although student feedback was not the sole impetus for making program changes, accessing this more detailed response was helpful in refining our purpose and direction, as well as highlighting weaknesses. Perhaps more important was the faculty’s willingness to engage in this self-reflective process and to take necessary actions. Rather than waiting for exit interview feedback from graduating students, counselor educators can conduct ongoing program evaluations through anonymous online surveys as well as town hall meetings that invite students to share their process of learning, perceptions of the cultural climate, and experiences of microaggressions. We have a growing understanding that during such evaluations great care needs to be taken for building safety, so as not to retraumatize students from marginalized communities. Based on the results and a series of Zoom town hall meetings, we have implemented changes, such as more consistent integration of social justice across the curriculum; training and day-long retreats focused on increasing faculty competence; faculty participation in Academics for Black Survival and Wellness, an intensive training led by Dr. Della Mosely and Pearis Bellamy; accountability support groups in social justice work; and decolonizing syllabi and class content (e.g., including BIPOC voices and non–APA-style writing assignments). Faculty have also made significant modifications to course materials. For example, beginning students complete weekly modules that include readings and exercises from The Racial Healing Handbook (Singh, 2019), and students study Liberation Psychology during the first week of theories class so they can consider ways to decolonize more traditional models throughout the semester. These strategies have been helpful in preparing students for more difficult conversations surrounding anti-racism in more advanced courses throughout the program. Forming faculty accountability partners or small groups is helpful so that faculty can support each other as a part of their ongoing development in addressing internalized White supremacy and avoiding harm to students.

Student feedback also called attention to the need for self-care, which our program continues to explore. Consistent with previous research (Collins et al., 2015; L. A. Goodman et al., 2018; Hoover & Morrow, 2016; Singh et al., 2010), students reported that their multicultural and social justice learning was often accompanied by moments of overwhelm, hopelessness, and despair. Without tools to manage these emotions, some students may retreat into defensiveness and withdrawal (Seward, 2019), and some may experience activist burnout (Gorski, 2019). Sustainability is necessary for effective social change efforts (Toporek & Ahluwalia, 2021). Counseling programs can offer resources and guidance for students to practice self-care with counselor educators modeling self-care behavior. For example, the Psychology of Radical Healing Collective (Chen et al., 2019) offered strategies to practice radical self-care, including making space for one’s own healing, finding joy and a sense of belonging, and engaging in advocacy at the local community level. Mindfulness practices can be integrated into social justice education to help students and counselor educators manage difficult emotions, increase their ability to be present, and strengthen compassion and curiosity (Berila, 2016). In addition to individual self-care practices, counselor educators can advocate for community care by tending to the community’s needs and drawing on collective experience and wisdom (Gorski, 2019).

The findings point to the need for counselor educators to better address Whiteness and White supremacy, as well as to center the experiences of students from marginalized communities. Counselor educators may be able to mobilize and direct White students’ feelings of guilt into racial consciousness and action by helping them explore Whiteness, White privilege, and what it means to them while allowing and confronting feelings that arise (Grzanka et al., 2019). It may be helpful for educators to read and assign books on White fragility and ways to address it (DiAngelo, 2018; Helms, 2020; Saad, 2020), so that they can assist White students in managing these emotions. It is important that educators explicitly name and recognize White supremacy as it shows up in counseling theory and practice, and to include a shift from the primary focus on the individual to understanding and dismantling oppressive systems. Counselor educators must also attend to the ways in which they center the comfort of White students over the needs of BIPOC students, so that they do not perpetuate harm and trauma (Galán et al., 2021). Although students with privileged identities may learn powerful lessons about oppression from their classmates, it is important that such learning does not occur at the expense of students with marginalized identities. Offering spaces for White students, especially those who are new to conversations about race and racism, to process their feelings may be helpful to avoid harm to BIPOC students who have experienced racial trauma. Similarly, BIPOC students may benefit from spaces in which they can talk freely and support each other as they unpack their own experiences of microaggressions and trauma (Galán et al., 2021).

Based on the finding that support from faculty was important in facilitating student growth and learning, counselor educators may benefit from implementing strategies informed by relational pedagogy and relational–cultural theory (Dorn-Medeiros et al., 2020). Relational pedagogy centers the relationship between teachers and students and posits that all learning takes place in relationships. Relational–cultural theory emphasizes mutual empathy and empowerment and is rooted in feminist multicultural principles. Practices grounded in these approaches include professors’ use of self-disclosure to model openness, vulnerability, and self-reflection; and their work to reduce power imbalances and invite student feedback at multiple points in time through anonymous surveys and one-on-one meetings. Counselor educators can uplift students as the experts of their experience (Sharma & Hipolito-Delgado, 2021).

Limitations and Future Research

The results of this study must be considered in light of a number of limitations. The use of the online survey meant that we were not able to follow up with students for further discussion or clarification of their responses. Adding focus groups or interviews to this methodology would likely provide a more thorough picture. In spite of assurances to the contrary, some students may have been hesitant to be honest out of concern that their own professors would be reading their feedback. It is possible that different themes would have emerged if all students had participated. In addition, 12% of the advanced students had participated as beginning students and therefore were previously exposed to the survey materials. Although this could have impacted their later responses, we suspect that given the nearly 2-year time lapse this may not have been meaningful. Nevertheless, future research and program evaluation would be strengthened with longitudinal analyses. Lastly, the reliability for the ACSA was relatively low, so conclusions are tentative; however, the results support the qualitative data. Despite these limitations, this study offers a model for assessing students’ learning and experiences with the goal of program improvement. The process of counselor educators humbling themselves and inviting and integrating student feedback is an important step in decolonizing counselor education and better serving students and the clients and communities that they will serve.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

American Counseling Association. (2014). ACA code of ethics. https://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/default-document-library/ethics/2014-aca-code-of-ethics.pdf?sfvrsn=55ab73d0_1

Arney, E. N., Lee, S. Y., Printz, D. M. B., Stewart, C. E., & Shuttleworth, S. P. (2019). Strategies for increased racial diversity and inclusion in graduate psychology programs. In M. T. Williams, D. C. Rosen, & J. W. Kanter (Eds.), Eliminating race-based mental health disparities: Promoting equity and culturally responsive care across settings (pp. 227–242). Context Press.

Arredondo, P., D’Andrea, M., & Lee, C. (2020). Unmasking White supremacy and racism in the counseling profession. Counseling Today. https://ctarchive.counseling.org/2020/09/unmasking-white-supremacy-and-racism-in-the-counseling-profession

Beer, A. M., Spanierman, L. B., Greene, J. C., & Todd, N. R. (2012). Counseling psychology trainees’ perceptions of training and commitments to social justice. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 59(1), 120–133. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026325

Berila, B. (2016). Integrating mindfulness into anti-oppression pedagogy: Social justice in higher education. Routledge.

Bvunzawabaya, B. (2012). Social justice counseling: Establishing psychometric properties for the Advocacy Competencies Self-Assessment Survey (Doctoral dissertation, Auburn University). https://etd.auburn.edu/handle/10415/3369

Chen, G. A., Neville, H. A., Lewis, J. A., Adames, H. Y., Chavez-Dueñas, N. Y., Mosley, D. V., & French, B. H. (2019). Radical self-care in the face of mounting racial stress: Cultivating hope through acts of affirmation. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/healing-through-social-justice/201911/radical-self-care-in-the-face-mounting-racial-stress

Collins, S., Arthur, N., Brown, C., & Kennedy, B. (2015). Student perspectives: Graduate education facilitation of multicultural counseling and social justice competency. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 9(2), 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1037/tep0000070

Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2023). 2024 CACREP standards.

https://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/2024-Standards-Combined-Version-6.27.23.pdf

Creswell, J. W., Plano Clark, V. L., Gutmann, M. L., & Hanson, W. E. (2003). Advanced mixed methods research designs. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), SAGE handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research (1st ed.; pp. 209–240). SAGE.

Cross, W. E., Jr., & Reinhardt, J. S. (2017). Whiteness and serendipity. The Counseling Psychologist, 45(5), 697–705. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000017719551

DiAngelo, R. (2018). White fragility: Why it’s so hard for White people to talk about racism. Beacon Press.

Dorn-Medeiros, C. M., Christensen, J. K., Lértora, I. M., & Croffie, A. L. (2020). Relational strategies for teaching multicultural courses in counselor education. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 48(3), 149–160. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmcd.12174

Field, T. A., Ghoston, M. R., Grimes, T. O., Sturm, D. C., Kaur, M., Aninditya, A., & Toomey, M. (2019). Trainee counselor development of social justice counseling competencies. Journal for Social Action in Counseling and Psychology, 11(1), 33–50. https://doi.org/10.33043/JSACP.11.1.33-50

Galán, C. A., Bekele, B., Boness, C., Bowdring, M., Call, C., Hails, K., McPhee, J., Mendes, S. H., Moses, J., Northrup, J., Rupert, P., Savell, S., Sequeira, S., Tervo-Clemmens, B., Tung, I., Vanwoerden, S., Womack, S., & Yilmaz, B. (2021). Editorial: A call to action for an antiracist clinical science. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 50(1), 12–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2020.1860066

Goodman, L. A., Wilson, J. M., Helms, J. E., Greenstein, N., & Medzhitova, J. (2018). Becoming an advocate: Processes and outcomes of a relationship-centered advocacy training model. The Counseling Psychologist, 46(2), 122–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000018757168

Goodman, R. D., Williams, J. M., Chung, R. C.-Y., Talleyrand, R. M., Douglass, A. M., McMahon, H. G., & Bemak, F. (2015). Decolonizing traditional pedagogies and practices in counseling and psychology education: A move towards social justice and action. In R. D. Goodman & P. C. Gorski (Eds.), Decolonizing “multicultural” counseling through social justice (pp. 147–164). Springer.

Gorski, P. C. (2019). Fighting racism, battling burnout: Causes of activist burnout in US racial justice activists. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 42(5), 667–687. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2018.1439981

Grzanka, P. R., Gonzalez, K. A., & Spanierman, L. B. (2019). White supremacy and counseling psychology: A critical–conceptual framework. The Counseling Psychologist, 47(4), 478–529. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000019880843

Haskins, N. H., & Singh, A. (2015). Critical race theory and counselor education pedagogy: Creating equitable training. Counselor Education and Supervision, 54(4), 288–301. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12027

Helms, J. E. (2020). A race is a nice thing to have: A guide to being a White person or understanding the White persons in your life (3rd ed.). Cognella.

Hill, C. E., Knox, S., Thompson, B. J., Williams, E. N., Hess, S. A., & Ladany, N. (2005). Consensual qualitative research: An update. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 196–205. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.196

Holcomb-McCoy, C. C., & Myers, J. E. (1999). Multicultural competence and counselor training: A national survey. Journal of Counseling & Development, 77(3), 294–302. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1999.tb02452.x

Hoover, S. M., & Morrow, S. L. (2016). A qualitative study of feminist multicultural trainees’ social justice development. Journal of Counseling & Development, 94(3), 306–318. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12087

Keum, B. T., & Miller, M. J. (2020). Social justice interdependence among students in counseling psychology training programs: Group actor-partner interdependence model of social justice attitudes, training program norms, advocacy intentions, and peer relationships. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 67(2), 141–155. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000390

Kozan, S., & Blustein, D. L. (2018). Implementing social change: A qualitative analysis of counseling psychologists’ engagement in advocacy. The Counseling Psychologist, 46(2), 154–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000018756882

Mull, R. C. (2020). Colleges are in for a racial reckoning. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/colleges-are-in-for-a-racial-reckoning

Okun, T. (2021). White supremacy culture – Still here. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1XR_7M_9qa64zZ00_JyFVTAjmjVU-uSz8/view

Ponterotto, J. G., Mathew, J. T., & Raughley, B. (2013). The value of mixed methods designs to social justice research in counseling and psychology. Journal for Social Action in Counseling and Psychology, 5(2), 42–68. https://doi.org/10.33043/JSACP.5.2.42-68

Ratts, M. J., & Ford, A. (2010). Advocacy Competencies Self-Assessment (ACSA) Survey©: A tool for measuring advocacy competence. In M. J. Ratts, R. L. Toporek, & J. A. Lewis (Eds.), ACA advocacy competencies: A social justice framework for counselors (pp. 21–26). American Counseling Association.

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar-McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2016). Multicultural and social justice counseling competencies: Guidelines for the counseling profession. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 44(1), 28–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmcd.12035

Royse, D., Thyer, B. A., & Padgett, D. K. (2010). Program evaluation: An introduction (5th ed.). Cengage.

Saad, L. F. (2020). Me and White supremacy: Combat racism, change the world, and become a good ancestor. Sourcebooks.

Sanabria, S., & DeLorenzi, L. (2019). Social justice pre-practicum: Enhancing social justice identity through experiential learning. Journal for Social Action in Counseling and Psychology, 11(2), 35–53. https://doi.org/10.33043/JSACP.11.2.35-53

Seward, D. X. (2019). Multicultural training resistances: Critical incidents for students of color. Counselor Education and Supervision, 58(1), 33–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12122

Sharma, J., & Hipolito-Delgado, C. P. (2021). Promoting anti-racism and critical consciousness through a critical counseling theories course. Teaching and Supervision in Counseling, 3(2), 15–25. https://doi.org/10.7290/tsc030203

Singh, A. A. (2019). The racial healing handbook: Practical activities to help you challenge privilege, confront systemic racism, and engage in collective healing. New Harbinger.

Singh, A. A., Appling, B., & Trepal, H. (2020). Using the multicultural and social justice counseling competencies to decolonize counseling practice: The important roles of theory, power, and action. Journal of Counseling & Development, 98(3), 261–271. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12321

Singh, A. A., Hofsess, C. D., Boyer, E. M., Kwong, A., Lau, A. S. M., McLain, M., & Haggins, K. L. (2010). Social justice and counseling psychology: Listening to the voices of doctoral trainees. The Counseling Psychologist, 38(6), 766–795. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000010362559

Spangler, P. T., Liu, J., & Hill, C. E. (2012). Consensual qualitative research for simple qualitative data: An introduction to CQR-M. In C. E. Hill (Ed.), Consensual qualitative research: A practical resource for investigating social science phenomena (pp. 269–283). American Psychological Association.

Toporek, R. L., & Ahluwalia, M. K. (2021). Taking action: Creating social change through strength, solidarity, strategy, and sustainability. Cognella Press.

Turner, D. (2018). “You shall not replace us!” White supremacy, psychotherapy and decolonisation. Journal of Critical Psychology, Counselling and Psychotherapy, 18(1), 1–12. https://cris.brighton.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/495044/JCPCP+18-1+-+Turner+article.pdf

Zetzer, H. A. (2021). Decolonizing the curriculum in health service psychology. Association of Psychology Training Clinics Bulletin: Practicum Education & Training, 20–22. https://aptc.org/images/File/newsletter/APTC_Bulletin_PET_2021_Spring%20FINAL.pdf

Sapna B. Chopra, PhD, is an associate professor at California State University, Fullerton. Rebekah Smart, PhD, is a professor at California State University, Fullerton. Yuying Tsong, PhD, is a professor and Associate Vice President for Student Academic Support at California State University, Fullerton. Olga L. Mejía, PhD, is a licensed psychologist and an associate professor at California State University, Fullerton. Eric W. Price, PhD, is an associate professor at California State University, Fullerton. Correspondence may be addressed to Sapna B. Chopra, Department of Human Services, California State University, Fullerton, P.O. Box 6868, Fullerton, CA 92834-6868, sapnachopra@fullerton.edu.

Aug 10, 2022 | Volume 12 - Issue 2

Lacey Ricks, Malti Tuttle, Sara E. Ellison

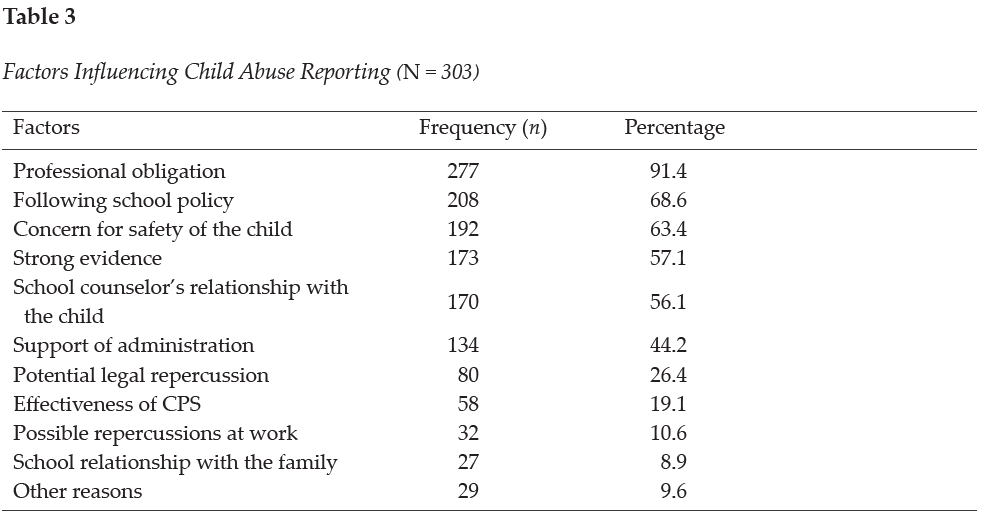

Quantitative methodology was utilized to assess factors influencing veteran school counselors’ decisions to report suspected child abuse. Veteran school counselors were defined as having 6 or more years of experience working as a school counselor within a public or private school. This study is a focused examination of the responses of veteran school counselors from a larger data set. The results of the analysis revealed that academic setting, number of students within the school, and students’ engagement in the free or reduced lunch program were significantly correlated with higher reporting among veteran school counselors. Moreover, veteran school counselors’ self-efficacy levels were moderately correlated with their decision to report. Highly rated reasons for choosing to report suspected child abuse included professional obligation, following school protocol, and concern for the safety of the child. The highest rated reason for choosing not to report was lack of evidence. Implications for training and advocacy for veteran school counselors are discussed.

Keywords: child abuse, reporting, veteran school counselors, self-efficacy, training

In 2019, approximately 4.4 million reports alleging maltreatment were made to U.S. child protective services (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services [HHS] et al., 2021). Of these reports, nearly two thirds were made by professionals who encounter children as a part of their occupation. Child maltreatment is identified as all types of abuse against a child under the age of 18 by a parent, caregiver, or person in a custodial role, and includes physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect (Fortson et al., 2016). Public health emergencies, such as the continued COVID-19 pandemic, increase the risk for child abuse and neglect due to increased stressors (Swedo et al., 2020). Factors such as financial hardship, exacerbated mental health issues, lack of support, and loneliness may contribute to increased caregiver distress, ultimately resulting in negative outcomes for children and adolescents (Collin-Vézina et al., 2020).

The psychological impact of child abuse and neglect on victims can increase the risk of mental health disorders such as depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder (Heim et al., 2010; Klassen & Hickman, 2022). Similarly, trauma experienced in childhood is associated with higher rates of long-term physical health issues when compared to individuals with less trauma; these include cancer (2.4 times more likely to develop), diabetes (3.0 times as likely to develop), and stroke (5.8 times more likely to experience; Bellis et al., 2015). Children who are victims of child abuse and neglect may also experience educational difficulties, low self-esteem, and trouble forming and maintaining relationships (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2019).

Voluntary disclosure of childhood abuse is relatively uncommon; one study found that less than half of adults with histories of abuse reported disclosing the abuse to anyone during childhood, and only 8%–16% of those disclosures resulted in reporting to authorities (McGuire & London, 2020). For this reason, mandated reporting by professionals is an integral piece of child abuse prevention. School counselors, by virtue of their ongoing contact with children, are uniquely positioned to identify and report child abuse (Behun et al., 2019). We recognize that school-based professionals such as teachers, administrators, and other school-based staff are mandated reporters as well. However, for the purpose of this article, we specifically focus on school counselors based on their role, responsibility, and training that best equips them to fulfill this expectation. School counselors have a unique role within the school system and play a critical role in ensuring schools are a safe, caring environment for all students (American School Counselor Association [ASCA], 2017). School counselors also work to identify the impact of abuse and neglect on students as well as ensure the necessary supports for students are in place (ASCA, 2021).

Ethical and Legal Mandates for Reporting Suspected Child Abuse

Although current estimates for the reporting frequency within schools are not available, it appears likely that high numbers of school counselors encounter the decision to report suspected child abuse each year. In fact, a 2019 survey of 262 school counselors indicated that 1,494 cases of child abuse had been reported by participants over a 12-month period (Ricks et al., 2019). Despite the frequency with which it occurs, reporting can be a distressing part of school counselors’ responsibilities (Remley et al., 2017); this could be because of limited knowledge or competency in reporting procedures, unfamiliarity with the law, or potential repercussions for the child (Bryant, 2009; Bryant & Milsom, 2005; Lambie, 2005). Additionally, laws, definitions, and mandates of child abuse and neglect vary by state; therefore, confusion may arise when school counselors relocate to another area (ASCA, 2021; Hogelin, 2013; Lambie, 2005; Tuttle et al., 2019). School counselors need to identify and familiarize themselves with the unique laws in their state in addition to reviewing federal law and ethical codes.

Federally, school counselors are mandated by the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act of 1974, Public Law 93-247, to report suspected abuse and neglect to proper authorities (ASCA, 2021). Failure to report suspected abuse could result in civil or criminal liability (Remley et al., 2017; White & Flynt, 2000). ASCA Ethical Standards echo this mandate, directing school counselors to report suspected child abuse and neglect while protecting the privacy of the student (ASCA, 2022a, A.12.a). School counselors should also assist students who have experienced abuse and neglect by connecting them with appropriate services (ASCA, 2022a). Moreover, school counselors should work to create a safe environment free from abuse, bullying, harassment, and other forms of violence for students while promoting autonomy and justice (ASCA, 2022a).

School Counselors as Advocates in Mandated Reporting

Barrett et al. (2011) recognized school counselors as social justice leaders based on their role to advocate for students who are underserved, disadvantaged, maltreated, or living in abusive situations. Child abuse impacts children and adolescents from every race, socioeconomic status, gender, and age (Lambie, 2005; Tillman et al., 2015). School counselors who are trained to provide culturally sustaining school counseling will work with students and families from all demographics to promote student wellness within their comprehensive school counseling program (ASCA, 2021). As leaders within the school, school counselors, and especially veteran school counselors, can work to educate all stakeholders on the implications of child abuse.

School counselors not only are legally positioned to serve as mandated reporters but also ethically positioned to train school personnel in recognizing and identifying child abuse symptoms and in reporting procedures (Hodges & McDonald, 2019). Training of school personnel, such as teachers, to identify and report suspected child abuse is essential because they are also recognized legally as mandated reporters (Hupe & Stevenson, 2019) and they interact with students daily. It is vital that school counselors advocate for ongoing comprehensive training related to child abuse because their knowledge affects many stakeholders in the school setting (ASCA, 2021; Tuttle et al., 2019).

Self-Efficacy Among Veteran School Counselors

Previous literature from this data set highlighted the reporting behaviors of early career school counselors (Ricks et al., 2019), and a framework was developed to assist new professionals in reporting (Tuttle et al., 2019). However, the child abuse reporting behaviors and needs of veteran school counselors are understudied. Therefore, this article focuses on veteran school counselors. For the purpose of this study, veteran school counselors are considered licensed school counselors having 6 or more years of experience. Professional literature has highlighted the unique needs and experiences of novice counselors as compared to veteran school counselors (Buchanan et al., 2017; Johnson et al., 2017). One study (Mishak, 2007) examined differences in instructional strategies for early career and veteran school counselors in elementary schools in Iowa. Although that study does not specifically address child abuse reporting, it does highlight differences found among the respondents based on their experience level.

One factor supporting the unique needs of veteran school counselors is self-efficacy. Self-efficacy theory posits that an individual’s expectations of mastery are strongly influenced by personal experience and indirect exposure to a phenomenon (Bandura, 1977, 1997). Veteran school counselors, based on their years of experience in a school setting, are likely to have multiple exposures to child abuse reporting. They may have filed reports themselves, spoken to peers about their reporting experiences, or assisted other professionals in the school with reporting. Bandura (1997) suggested that self-efficacy is supported when individuals not only possess the skill and ability to complete a task, but also have the confidence and motivation to execute it.

Veteran school counselors can receive ongoing training from workshops, university courses, webinars, district training, or other professional organizations that may further impact self-efficacy levels. Previous research has shown that as an individual’s knowledge of child abuse increases, their levels of self-efficacy in recognizing or reporting child abuse also increases (Balkaran, 2015; Jordan et al., 2017). However, little research linking school counselors’ self-efficacy levels to child abuse reporting has been published. Despite the paucity of research on this topic, Ricks et al. (2019) found a moderate relationship between early career school counselors’ self-efficacy and their ability to identify types of abuse. Additionally, Tang (2020) found that school counseling supervision increased school counselor self-efficacy; differences between early career and veteran school counselors were not addressed in Tang’s study. Although the positive correlation found by Tang did not directly address child abuse reporting, assisting students with crisis situations was one of the principal components of the analysis. Even though veteran school counselors have experience serving as mandated reporters, they require ongoing professional development in this area to effectively fulfill their roles as advocates in maintaining the welfare and safety of students (ASCA, 2021; Tuttle et al., 2019). Therefore, we seek to utilize this article as a form of advocacy on behalf of veteran school counselors by providing additional research and literature in the field.

Purpose of the Present Study

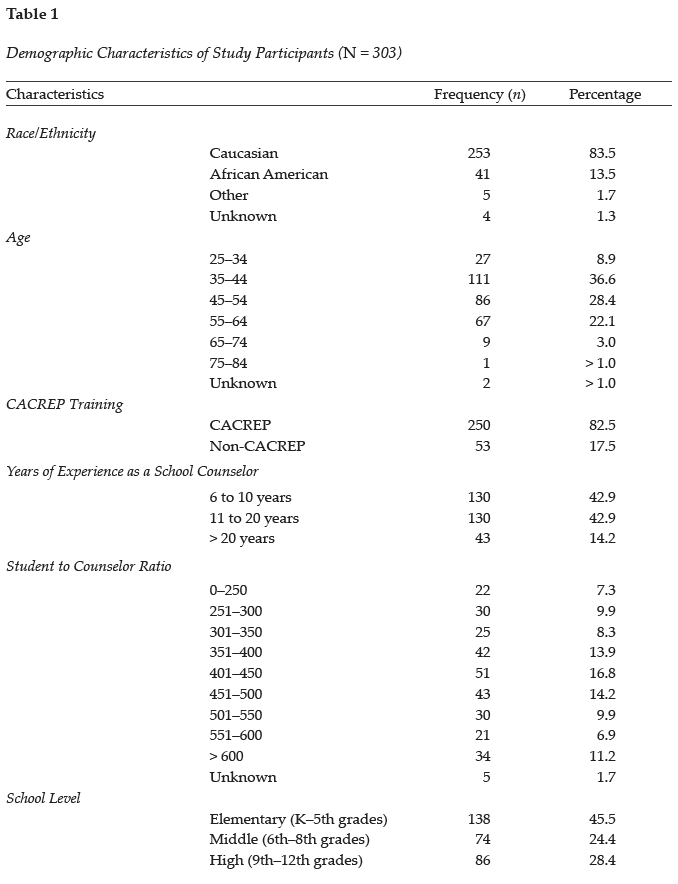

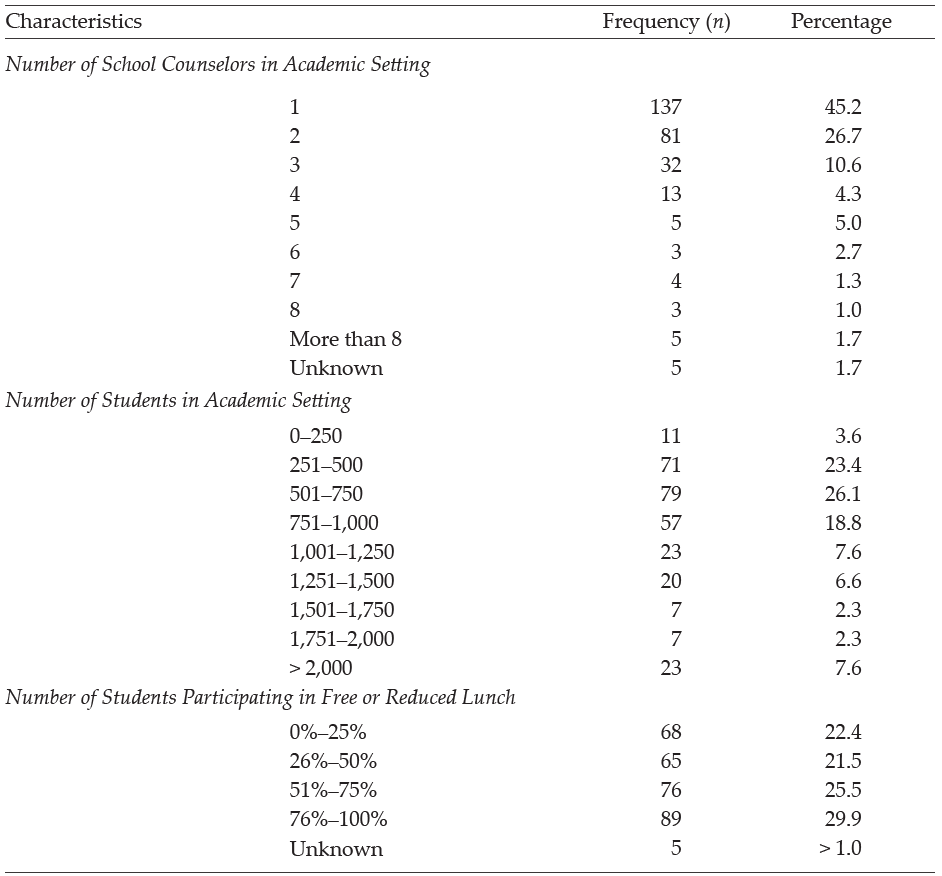

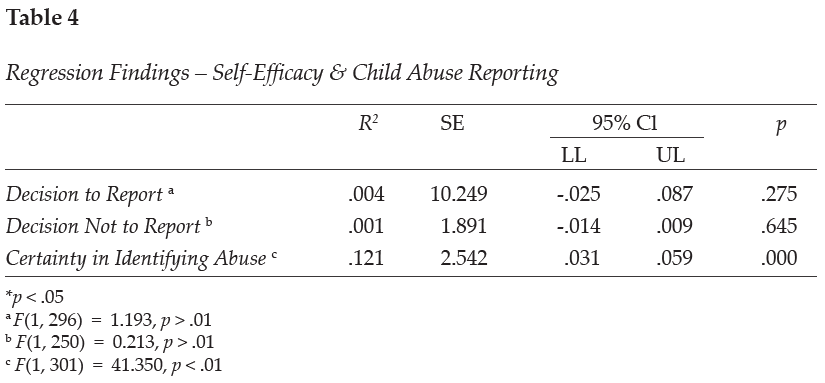

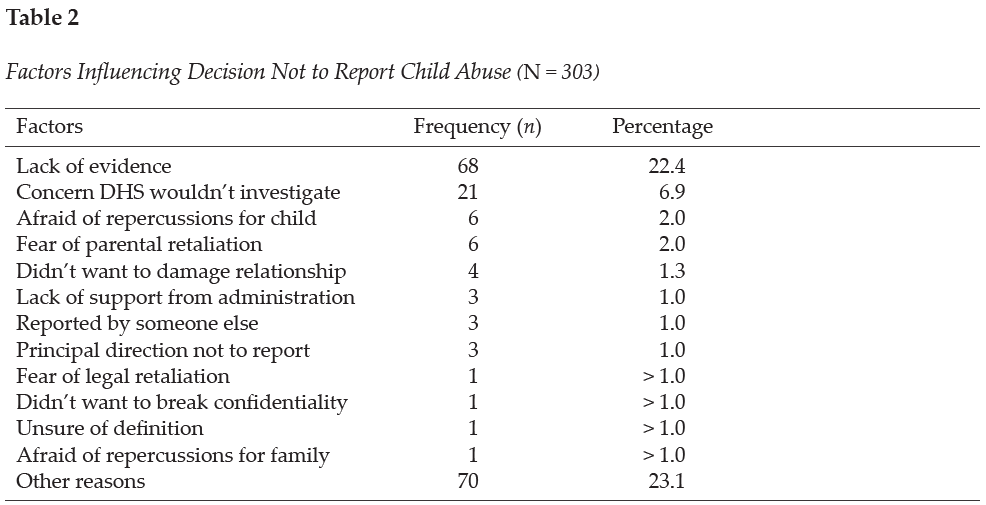

The purpose of this quantitative study is to examine (a) the prevalence of child abuse reporting by veteran school counselors within the school year; (b) the factors affecting veteran school counselors’ decisions to report or not report suspected child abuse; (c) reasons for reporting or not reporting suspected child abuse by veteran school counselors; and (d) veteran school counselors’ self-efficacy levels related to child abuse reporting. Our intent was to build upon an initial larger study to examine veteran school counselors’ knowledge of procedures and experiences with child abuse reporting. The present study is a focused examination of the data collected from veteran school counselors as part of the primary study, which solicited data from school counselors across their careers related to their experiences with child abuse reporting (see Ricks et al., 2019). Demographic variables were collected from participants to assess their impact on child abuse reporting; see Table 1 for a complete list of variables.

Methods

Multiple correlation and regression analyses were conducted to assess factors influencing veteran school counselors’ decisions to report suspected child abuse. After obtaining IRB approval, the authors recruited school counselors in the Southeastern United States (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia). Participants were recruited using a professional school counseling association membership list, a southeastern state counseling association listserv, and social media. Participants were informed that participation in the online study was voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study at any time. Participants were also informed that the survey would take between 10–15 minutes and that the information collected in the survey would remain anonymous.

Participants

A total of 848 surveys were collected from participants. Veteran school counselor data was extracted from the total sample and analyzed to assess the unique experiences of these individuals in child abuse reporting. Veteran school counselors were defined as having 6 or more years of experience working as a school counselor within a public or private school. Four hundred and twenty-eight veteran school counselors began the survey, but data from 125 participants was excluded from the analysis for incomplete responses, resulting in a final sample of 303 participants. Most participants (n = 265, 87.5%) reported being licensed/certified as a school counselor. Some participants may not have possessed a license because of working in the private school sector or working on a provisional basis. See Table 1 for all demographic frequencies and percentages related to participants in the study.

Measures

Three measures were selected and employed as part of the larger study. These included the Child Abuse Reporting Questionnaire (Bryant & Milsom, 2005), the School Counselor Self-Efficacy Scale (Bodenhorn & Skaggs, 2005), and the Knowledge of Child Abuse Reporting Questionnaire (Ricks et al., 2019). Each measure is described below as previously reported in Ricks et al. (2019).

Child Abuse Reporting Questionnaire

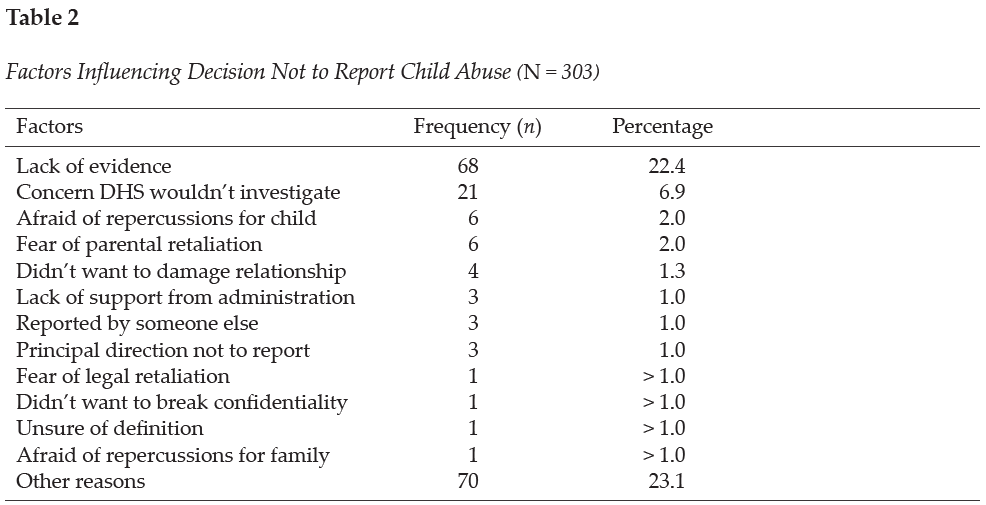

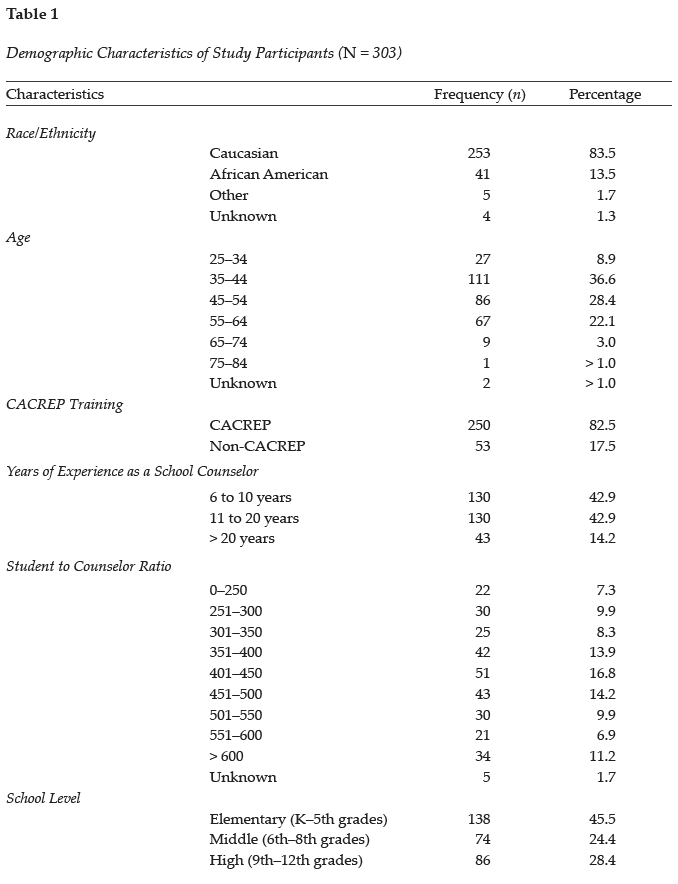

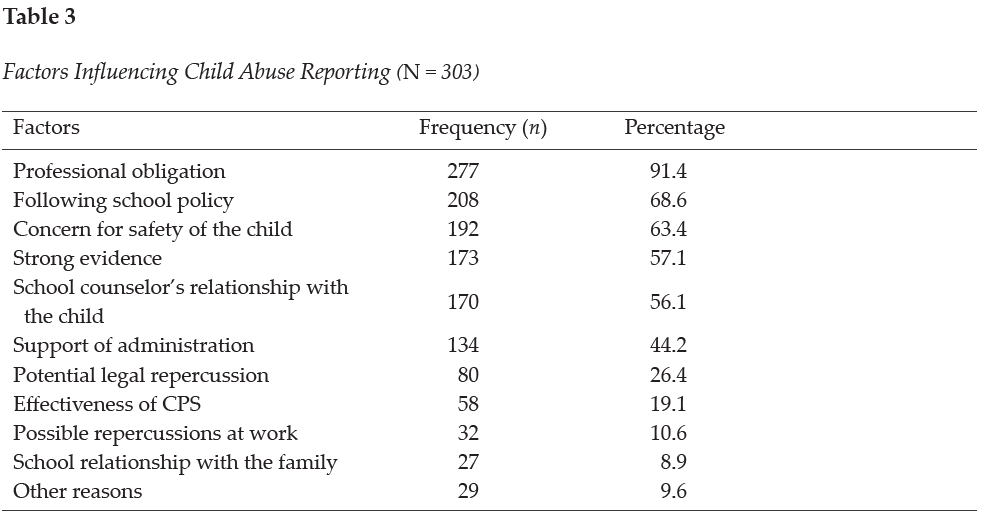

The Child Abuse Reporting Questionnaire was developed to assess three domains, including school counselor General Information, Training in Child Abuse Reporting, and Child Abuse Reporting Experience (Bryant & Milsom, 2005). In the first section of the questionnaire, Training in Child Abuse Reporting, participants were asked to list where they obtained their knowledge of child abuse reporting and to assess four different types (physical, sexual, neglect, emotional) of child abuse. In the Child Abuse Reporting Experience section, the participants were asked two questions. The first question asked participants to recall the number of suspected child abuse cases they encountered during the preceding school year and the number of child abuse cases they reported. The next question asked participants how many cases of suspected child abuse they did not report. Participants were also asked in the survey to indicate reasons for choosing not to report suspected child abuse cases based on 12 commonly reported barriers or to list other reasons for not reporting the suspected cases. See Table 2 for a complete list of the common reasons given for not reporting suspected child abuse cases. Internal consistency measures were not obtained for this questionnaire because of the demographic nature of assessing participants’ personal experiences with child abuse reporting.

School Counselor Self-Efficacy Scale

The School Counselor Self-Efficacy Scale (SCSE) was used to assess school counselors’ self-efficacy and to link their personal attributes to their career performance (Bodenhorn & Skaggs, 2005). Participants completed Likert scale questions to indicate their confidence in performing school counseling tasks for 43 scale items. An example question would ask school counselors to indicate their confidence in advocating for integration of student academic, career, and personal development into the mission of their school. A rating of 1 indicated not confident and a rating of 5 indicated highly confident. The coefficient alpha for the scale score was found to be .95 (Bodenhorn & Skaggs, 2005). The SCSE subscales include five domains: Personal and Social Development (12 items), Leadership and Assessment (9 items), Career and Academic Development (7 items), Collaboration and Consultation (11 items), and Cultural Acceptance (4 items). The correlations of the subscales ranged from .27 to .43.

Knowledge of Child Abuse Reporting Questionnaire

The Knowledge of Child Abuse Reporting Questionnaire was developed to assess respondents’ knowledge of child abuse reporting and procedures within three areas (Ricks et al., 2019). To develop the survey, the researchers and outside counselor educators reviewed the questionnaire to determine if it clearly measured the constructs. In the first section of the questionnaire, Identifying Types of Abuse, participants’ perceptions of their ability to identify the four different types of child abuse were assessed. To complete this section, participants rated their comfort level using a 4-point Likert scale. A rating of 1 indicated very uncertain and a rating of 4 indicated very certain. The coefficient alpha for the scale score was found to be .902. The Knowledge of Guidelines section assessed participants’ knowledge of the state rules, ASCA Ethical Standards, and child abuse reporting protocol within their current school and district. To complete this section, participants rated their comfort level using a 5-point Likert scale. A rating of 1 indicated not knowledgeable and a rating of 5 indicated extremely knowledgeable. The coefficient alpha for the scale score was found to be .799. Lastly, the Child Abuse Training section assessed where participants received training on general knowledge of child abuse reporting, how to make a referral, and indicators of child abuse. To complete this section, participants selected options from a dropdown menu based on commonly reported agencies or listed an organization not provided. Options included in the survey list were universities or colleges, schools or districts, conferences or workshops, colleagues, journals, professional organizations, or the state department of education.

Data Analysis

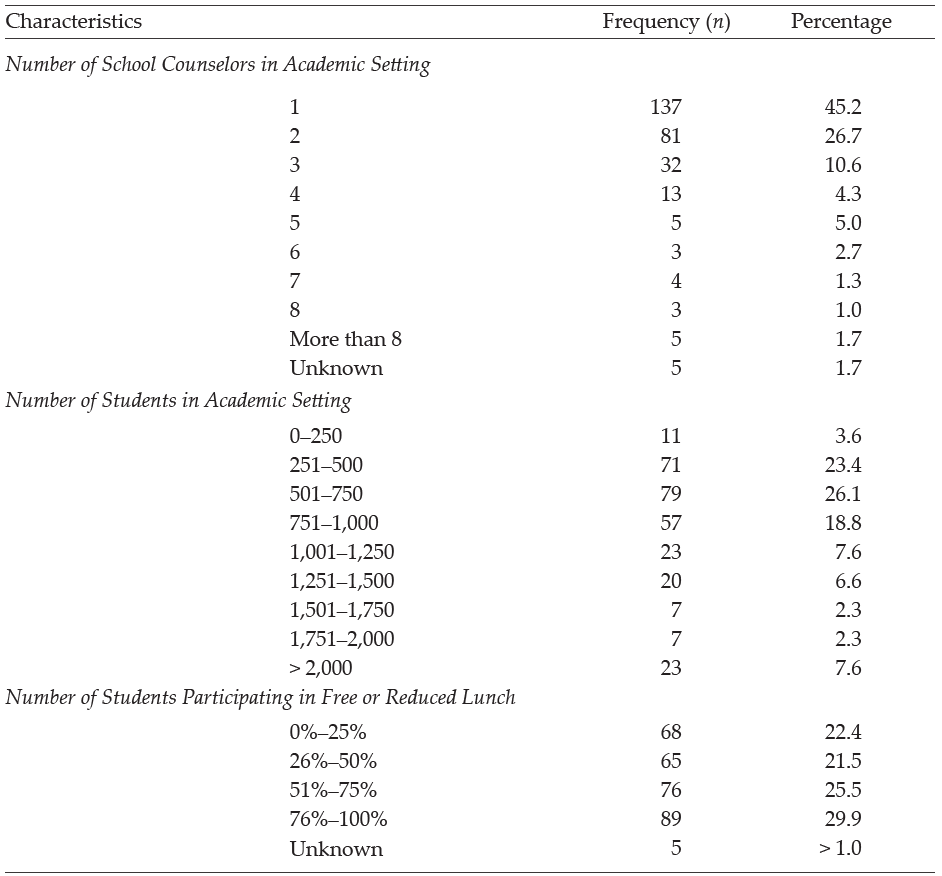

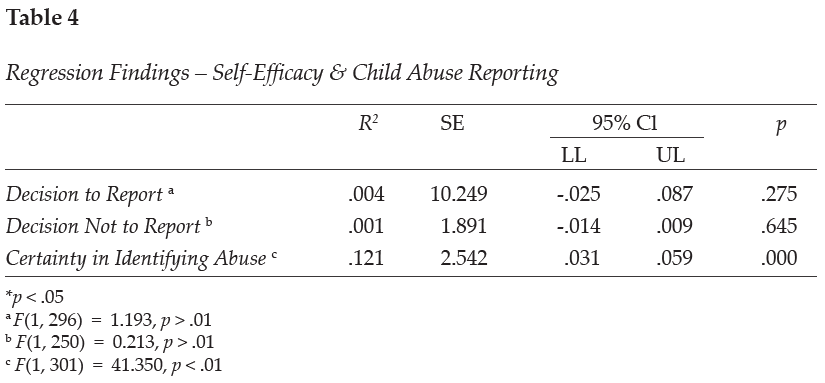

SPSS Statistics 27 was used to analyze data within this study. First, a correlation analysis was executed to assess the strength of the relationship across variables. Next, analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were performed to assess the relationship between the number of reported child abuse cases and five demographic variables, which included academic setting (elementary, middle, high); number of students participating in the school’s free or reduced lunch program; number of school counselors working in a school setting; years of experience as a school counselor; and number of students enrolled in a school setting. Lastly, regression analyses were used to determine the relationship between school counselors’ self-efficacy and their decisions to report or not report suspected child abuse cases as well as to assess the relationship between school counselors’ self-efficacy and their certainty in identifying types of abuse.

Results

Suspected and Reported Cases of Abuse

Descriptive statistics generated from the child abuse survey included the participants (N = 303) suspecting 2,289 cases of child abuse during the school year. Scores reported by participants ranged from 0 to 100 (M = 7.71, SD = 10.58). Seven participants omitted this question within the questionnaire. Participants indicated reporting a total of 2,140 cases of suspected child abuse; individual frequency ranged from 0 to 100 (M = 7.21, SD = 10.25). Physical child abuse cases (M = 4.03, SD = 7.12) were reported at a higher rate than cases of neglect (M = 2.72, SD = 5.10), emotional abuse (M = 0.56, SD = 1.52), and sexual abuse (M = 0.57, SD = 1.37).

School Demographics