Dec 5, 2024 | Volume 14 - Issue 3

Crystal M. Morris, Priscilla Rose Prasath

This study explored the effects of the 8-week Mindfulness-Based Strengths Practice program on relationship satisfaction, mindfulness traits, and overall well-being in female survivors of military sexual trauma. Conducted via Zoom with 24 participants organized into three groups, the quasi-experimental design included pre- and post-intervention assessments. Although no statistically significant differences were found in relationship satisfaction, dispositional mindfulness, or overall well-being, a notable positive correlation emerged between gains in relationship satisfaction and mindfulness, as well as between well-being and relationship satisfaction during the intervention. The study suggests practical insights for trauma treatment using a non-pathological counseling approach, emphasizing the need for further research and offering implications for clinical application, group practice, counselor education, and future studies in the field.

Keywords: mindfulness, military sexual trauma, Mindfulness-Based Strengths Practice, relationship satisfaction, well-being

The global spotlight on violence against women, particularly sexual assault and harassment, has garnered substantial attention in recent years. The World Health Organization found sexual violence to be a major public health problem and a violation of women’s human rights (WHO; 2021). WHO estimated that 27% of women aged 15–49 years worldwide have reported being subjected to some form of sexual violence.

When trauma is prevalent among women such as female service members, particularly in the context of military sexual trauma (MST), it can often hinder the development of meaningful relationships (Department of Veterans Affairs, 2021; Wilson, 2018). The #IamVanessaGuillen movement, which gained traction in 2020, further underscored the problem. Guillen’s death was connected to sexual harassment and assault while she served in the military, sparking numerous accounts from veterans and active-duty service members who faced similar experiences (Meinert & Wentz, 2024). Despite the Department of Veterans Affairs mandating MST screening, 67% of female survivors do not report their traumatic experiences (Wilson, 2018).

Military culture, marked by language, norms, and beliefs, presents challenges in seeking mental health treatment despite the recognition of heightened risks for MST survivors (Burek, 2018; Litz, 2014). Understanding the interplay between military culture and mental health treatment is crucial, especially for female veterans facing barriers to care-seeking (Kintzle et al., 2015). MST has garnered attention, with the Veterans Health Administration providing counseling services since 1992. However, research indicates that women in the military experience higher rates of sexual assault than men in the military, emphasizing the need for multi-level interventions (Blais, 2019; Brownstone et al., 2018). Brownstone et al. (2018) underscored the factors contributing to MST and advocated for supportive and validating responses to survivors.

MST survivors face heightened risks of psychological, social, physical, and employment-related difficulties (Costello, 2022). Female MST survivors commonly experience issues such as declining sexual functioning, social support challenges, maladaptive coping mechanisms, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, and reduced relationship satisfaction (Blais, 2020; Georgia et al., 2018). Psychological trauma, triggered by such distressing events, can lead to fear, nightmares, helplessness, and difficulties in relationships (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). PTSD, a challenging diagnosis for trauma survivors, involves exposure to traumatic events and intrusive symptoms impacting intimate relationships (Campbell & Renshaw, 2018). Women who experience trauma are more susceptible to PTSD and may require exploration of the ramifications of PTSD on their relationships (W. J. Brown et al., 2021).

Relationship satisfaction is a critical outcome for trauma survivors, with positive psychology interventions addressing disparities in social functioning for survivors of MST as an option (Morris, 2022; Blais, 2020). Positive psychology has foundations rooted in ancient traditions. Concepts of human flourishing, character strengths, virtue, and well-being have shaped spiritual and philosophical thought across cultures (Peterson & Seligman, 2004; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). It is built on the idea that, rather than solely focusing on pathology or mental illness, psychology should explore and promote aspects of human life that contribute to happiness, fulfillment, and meaning (Peterson & Seligman, 2004; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). The five elements of Seligman’s PERMA model (positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishments) and character strengths, including wisdom, courage, humanity, justice, temperance, and transcendence, play a pivotal role in enhancing well-being (Seligman, 2012; VIA Institute on Character, 2019; Wagner et al., 2020). A non-pathological wellness approach, incorporating positive psychology interventions like the VIA Character Strengths (Niemiec, 2013, 2014) and mindfulness practices, have emerged as a promising intervention for trauma survivors (Carrola & Corbin-Burdick, 2015; Cebolla et al., 2017; Niemiec, 2014; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000; Wingert et al., 2022).

Mindfulness, which has proven effective in reducing PTSD symptoms, is integrated with character strengths in the Mindfulness-Based Strengths Practice (MBSP) program (Niemiec, 2014; Zhu et al., 2019). The 8-week program combining mindfulness and character strengths practices has shown positive effects on well-being and relationship satisfaction (Ivtzan et al., 2016; Pang & Ruch, 2019). Exploring the potential of MBSP in addressing relationship satisfaction, mindfulness practices, and overall well-being for MST survivors is crucial.

Theory of Well-Being—PERMA Model

Seligman’s PERMA model and theory of well-being incorporates the hedonic (i.e., connecting with feelings of pleasure) and eudaimonic (i.e., experiences of meaning and purpose) perspectives of well-being and poses that these two components are necessary for optimal well-being (Seligman, 2012). Seligman’s PERMA model measures each element, utilizing a subjective and objective approach in the form of positive psychology interventions (Goodman et al., 2018). Furthermore, Thompson et al. (2016) reported that using both subjective and objective well-being constructs with veterans may be appropriate. The PERMA-Profiler (Butler & Kern, 2016), a multidimensional scale that assesses the five pillars of well-being, has good reliability and acceptable levels of convergent, divergent, and criterion-related validity with student veterans (Umucu et al., 2020). The PERMA-Profiler may help researchers and counselors assess the well-being of individuals, including veterans, by providing an alternative path to conceptualizing psychological interventions (Umucu et al., 2020).

Aim of the Study and Research Questions

The primary objective of the present investigation was to assess the efficacy of the MBSP program concerning its impact on the levels of relationship satisfaction, mindfulness, and overall well-being among female survivors of MST. Simultaneously, this study sought to furnish valuable insights into the implementation of practical techniques rooted in mindfulness and character strengths that can facilitate the cultivation of robust and healthy relationships in this specific population. The research questions and hypotheses that guided the study were:

RQ1. Is there a positive relationship between the use of the MBSP program and relationship satisfaction in females who experienced MST as measured by the Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS)?

H1: There will be a positive effect on relationship satisfaction of female survivors of MST after completing the MBSP program.

RQ2. Will the MBSP program improve dispositional (trait) mindfulness as measured by the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) in female survivors of MST?

H2: The MBSP program will improve dispositional (trait) mindfulness in female survivors of MST.

RQ3. What is the effect of the MBSP program on overall well-being in female survivors of MST as measured by the PERMA-Profiler?

H3: The MBSP program will improve overall well-being in female survivors of MST.

Method

Recruitment and Screening Procedures

In this research, a multifaceted recruitment strategy was employed, encompassing recruitment flyers, letters, referrals, and social media channels. Targeted areas included military behavioral clinics, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the Steven A. Cohen Military Family Clinic, private practices, and social media counseling groups. Word-of-mouth referrals were also completed. A pre-screening phase, conducted by phone or online, featured two questions related to MST experiences, aligning with VA-MST criteria. Upon meeting the inclusion criteria (i.e., female, 18 years of age or older, veteran or active-duty service member, has experienced sexual harassment or sexual assault while serving in the U.S. military), participants then submitted demographic information online. A counselor-in-training (CIT) and Crystal M. Morris (first author and researcher) managed the pre-screening. Qualified individuals underwent a comprehensive trauma history and psychosocial interview led by Morris and the CIT as part of the screening process.

Participants

Several studies employing the MBSP program as an intervention within the general population reported individual sample sizes ranging from 20 to 126 (Hofmann et al., 2020; Ivtzan et al., 2016; Pang & Ruch, 2019; Whelan-Berry & Niemiec, 2021; Wingert et al., 2022). The sample size for the study was determined using G-Power software, adhering to Cohen’s (1998) conventions, with a medium effect size of .5, error probability of .05, and a power of .8. A priori statistical power analyses (Faul et al., 2007) indicated a sample size of 15 participants, ensuring adequate statistical power throughout the study.

A total of 24 female survivors of MST from various military branches (i.e., Army, Navy, and Air Force), both enlisted members and officers, participated in the study. After cleaning the data, participants who had greater than 20% missing data on the scale items were removed from the study (Hair et al., 2018). For the remaining participants with missing data, mean substitution was used for the Likert scale items (Hair et al., 2018). Of the 24 participants, 41.7% (n = 10) identified as Black/African American, 45.8% (n = 11) identified as White/Caucasian, and 12.5% (n = 3) identified as Latina/Hispanic. Participants were between the ages of 22 and 63, with a mean age of 43.38%. Of the participants, 54.2% served in the Army, 33.3% in the Air Force, and 12.5% in the Navy. The majority (78.3%) had an enlisted military rank and 21.7% were officers. Of the participants, 91.67% received unwanted, threatening, or repeated sexual attention while in the military; 41.67% had prior mindfulness practice experience; 79.17% received prior treatment for PTSD/trauma in therapeutic counseling; 83.33% reported no diagnosis of bipolar, schizophrenia, borderline personality disorder, or dissociative identity disorder; and 66.67% reported never being a client for PTSD/trauma with Morris.

Research Design

This study employed a quantitative quasi-experimental design, collecting data pre- and post-intervention, utilizing one-way repeated measures ANOVA, the Friedman test, and the Pearson product coefficient for analysis. The dependent variables include relationship satisfaction, mindfulness, and well-being, assessed at three time points. The independent variable was the MBSP intervention, conducted online because of COVID-19. The Relationship Assessments Scale (RAS), PERMA-Profiler, and Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) were used as assessments. Table 1 outlines the 8-week MBSP program.

Data Collection Procedures

Data collection for this study occurred online from May 2022 to August 2022, with the approval of the University of Texas at San Antonio Institutional Review Board. All participants were provided with an IRB-approved consent form before joining the study. The research involved a pre-screening process, demographic data collection, trauma history interviews, and pretest and posttest assessments conducted at different stages (i.e., baseline, Week 4, and Week 8) of the MBSP program. Participant information was securely stored on Qualtrics. Instruments used in the study included the VA-MST screening questions (2 items), the RAS (Hendrick et al., 1998), the MAAS (Bishop et al., 2004), and the PERMA-Profiler (Butler & Kern, 2016). Those who completed the study received a $50 Amazon gift card as compensation. The MBSP sessions were conducted virtually via Zoom, with Morris, a licensed professional counselor, as the facilitator and a CIT as process observer.

Table 1

Standard Structure of MBSP Sessions and Program (Niemiec, 2014)

| Session |

Core Topic |

Mindfulness Practice Description |

Session Description |

Overall

Internal Session Structure of MBSP |

| 1 |

Mindfulness and Autopilot |

Raisin exercise

(Kabat-Zinn, 1990) |

The autopilot mind is pervasive; insights and change opportunities start with mindful attention. |

I. Opening meditation |

| 2 |

Your Signature Strengths |

You at your best (includes strength-spotting; Niemiec, 2014) |

Identify what is best in you; this can unlock potential to engage more in work and relationships and reach higher personal potential. |

II. Dyads or group discussion |

| 3 |

Obstacles are Opportunities |

Statue meditation

(Niemiec, 2014) |

The practice of mindfulness and strengths exploration leads immediately to two things—obstacles/barriers to the practice and a wider appreciation for the little things in life. |

III. Introduction to new material |

| 4 |

Strengthening Mindfulness in Everyday Life (Strong Mindfulness) |

Mindful walking |

Mindfulness helps us attend to and nourish the best, innermost qualities in everyday life in ourselves and others while reducing negative judgements of self and others; conscious use of strengths can help us deepen and maintain mindfulness practices. |

IV. Experiential–mindfulness/character strengths experience |

| 5 |

Valuing Your Relationships |

Loving-kindness/strength-exploration meditation

(Neff, 2011; Salzberg, 1995) |

Mindful attending can nourish two types of relationships: relationships with others and our relationship with ourselves. Our relationship with ourselves contributes to self-growth and can have an immediate impact on our connection with others. |

V. Debriefing or Virtue circle |

| 6 |

Mindfulness of the Golden Mean (Mindful Strengths Use) |

Character strengths 360 review and fresh start meditation |

Mindfulness helps to focus on problems directly, and character strengths help to reframe and offer different perspectives not immediately apparent. |

VI. Suggested homework exercises for next session |

| 7 |

Authenticity and Goodness |

Best possible self exercise |

It takes character (e.g., courage) to be a more authentic “you” and it takes character (e.g., hope) to create a strong future that benefits both oneself and others. Set mindfulness and character strengths goals with authenticity and goodness in the forefront of the mind. |

VII. Closing meditation (strengths Gatha)—mindfully transitioning to the next day |

| 8 |

Your Engagement with Life |

Golden nuggets exercise |

Stick with those practices that have been working well and watch for the mind’s tendency to revert to automatic habits that are deficit-based, unproductive, or that prioritize what’s wrong in you and others. Engage in an approach that fosters awareness and celebration of what is strongest in you and others. |

VIII. Reflect, assessments, close |

Note. Source: Adapted from Mindfulness-Based Strengths Practice (MBSP) Group Intervention: A Systematic Review (Prasath et al., 2021).

MBSP Program Group Intervention

In this study, the MBSP intervention was implemented using a structured curriculum from Niemiec (2014) aimed at enhancing treatment fidelity. The curriculum encompassed three main sections: an introductory portion outlining the foundational assumptions and change process in MBSP; essential information for conducting MBSP groups, including format and timing; and key reminders. The core of MBSP group sessions involved typical group dynamics, including participant interactions with themselves, fellow group members, and the group leader. Notably, the MBSP program comprises eight sessions, usually lasting 2 hours, though the duration can be adjusted based on the setting; for this study, sessions ran for 90 minutes. The MBSP program was selected for this study because it emphasizes discovering individuals’ strengths and fostering what is right within them, in contrast to focusing on deficiencies. MBSP integrates mindfulness and character strengths practices to enhance participants’ relationship satisfaction, mindfulness skills, and overall well-being (Niemiec, 2014). Morris conducted two groups per week, each accommodating 4–10 participants, over an 8-week period, with an additional group added to account for attrition, and following the standard structure outlined in Table 1.

Group Leadership

Morris has previous training in MBSP, a certification in mindfulness meditation, commitment to group work and leadership through the Association for Specialists in Group Work Leadership Institute in 2024, experience with multicultural populations, and experience living in a diverse military community, all of which equipped her for leading the MBSP program and study. Through her training to become an effective group leader, she learned to consider intersectionality, group dynamics, fostering a positive environment, promoting awareness, group cohesion, and compassion among participants sharing personal information (Corey et al., 2018).

Instruments

Demographic Questionnaire

Demographic questionnaires were given to all participants for screening purposes reporting age, ethnicity, gender, race, level of education, and military experience. Participants who met the criteria for the group (i.e., female, 18 years and older, military veteran/active-duty service member, and have experienced sexual assault or harassment while serving in the military) were assessed with a trauma history psychosocial interview.

VA-MST Screening Items

Thirty-one female veterans or service members were screened for MST with the following questions using two trichotomously scored (i.e., yes, no, decline to answer) questions: “When you were in the military: (a) Did you receive uninvited and unwanted sexual attention, such as touching, cornering, pressure for sexual favors, or verbal remarks? and (b) Did someone ever use force or threat of force to have sexual contact with you against your will?” The items may be referred to as “harassment-only MST” and “assault MST,” independently (Gibson et al., 2016). After screening, 31 participants met the criteria for the study, however, 24 completed the entire study due to attrition.

PERMA-Profiler

The PERMA-Profiler scale, developed by Butler and Kern (2016), assesses the five pillars of well-being: positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment. Comprising 23 items, with 15 items dedicated to PERMA elements and eight fillers, each domain is measured using three items on an 11-point scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 10 (always), or 0 (not at all) to 10 (completely). Butler and Kern reported Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from .71 to .89 for positive emotion, .60 to .81 for engagement, .75 to .85 for relationships, .85 to .92 for meaning, and .70 to .86 for accomplishment. Mahamid et al. (2023) validated the PERMA-Profiler in diverse populations, reporting a 5-factor solution with 85.49% cumulative variance. Their study showed a high Cronbach’s alpha (α = .93), confirming internal consistency. Ryan et al. (2019) found acceptable internal consistency (α = .80 to .93) in Australian adults and established moderate convergent validity with health outcomes (r = 0.46 to 0.68). Umucu et al. (2020) validated the instrument utilizing Pearson correlation coefficients and the Kruskal-Wallis test among student veterans, demonstrating satisfactory reliability, convergent and divergent validity, and criterion-related aspects. The current study reported well-being domain Cronbach alphas of .96 and .94 with 95% CIs [.93, .98], [.89, 97], and [.89, .97] across data collection periods, confirming the PERMA-Profiler’s robustness and effectiveness in assessing the dimensions of well-being. The omega coefficients for well-being for this study were .96 and .94 with 95% CIs [.93, .98], [.89, .97], and [.89, .97].

Relationship Assessment Scale

The RAS (Hendrick et al., 1998) is a 7-item self-report scale, designed to measure general relationship satisfaction. The RAS can be used for anyone in a relationship, whether romantic or non-romantic (Hayden et al., 1998). The brevity of the scale makes it applicable in clinical settings and for online administration (Hendrick, 1988). The estimated time of completion is 5 minutes. Furthermore, the RAS uses a Likert-type scale with 1 representing low and 5 representing high. The scores for each item are added, totaled, and then divided by 7 to produce a mean score. Higher scores indicate higher levels of relationship satisfaction. The RAS is favored, as it is concise and useful in measuring satisfaction in relationships, including non-romantic relationships. Sample items ask the respondents to “rate their level of problems in the relationship” and “the extent to which their expectations had been met.” The RAS has generated good test–retest reliability, internal consistency, item reliabilities, and validity (Fallahchai et al. 2019; Maroufizadeh et al., 2020). Emergent data also support its convergent and predictive ability (Topkaya et al., 2023).

Hendrick et al. (1998) endorsed the RAS for several settings and populations. The RAS revealed significant connections to commitment, love, sexual attraction, self-disclosure, and relationship investment. Furthermore, Hendrick (1988) also discovered an inter-item correlation of .49 and internal consistency of α = .86 in her assessment of reliability. In this study, the Cronbach alphas for the relationship satisfaction at each data collection period were .86, .92, and .96 with 95% CIs [.66, .91], [.86, .96], and [.92, .98], showing good internal consistency and reliability. The omega coefficients for relationship satisfaction for this study were .81, .92, and .96 with 95% CIs [.66, .91], [.86, .96], and [.92, .98].

Mindful Attention Awareness Scale

The MAAS (Bishop et al., 2004) is a 15-item self-report instrument assessing dispositional mindfulness. Participants rate items on a 6-point scale, measuring how frequently they experience mindfulness-related behaviors. Higher scores indicate greater dispositional mindfulness. The MAAS does not have subscales. High scores on the MAAS correlate positively with self-consciousness, positive affect, self-esteem, and optimism and correlate negatively with anxiety, depression, and negative affect (Phang et al., 2016). Dispositional mindfulness, as measured by the MAAS, reflects a general tendency to be more aware and attentive in everyday life (Bishop et al., 2004). Examples of items include “I find myself preoccupied with the future or the past” and “I find myself doing things without paying attention.” The instrument yields a mean score by averaging responses across all items. Internal consistency estimates (Cronbach’s alpha) for the MAAS in adult samples consistently exceed .80 (K. W. Brown & Ryan, 2003). Additionally, Duffy et al. (2022) demonstrated the MAAS’s reliability and validity in measuring mindfulness in veterans with PTSD. Cronbach’s alphas for the mindfulness trait in this study were .89, .84, and .90 with 95% CIs [.81, .95], [.73, .92], and [.84, .95] across data collection periods, indicating strong internal consistency. The omega coefficients for mindfulness for this study were .89, .84, and .90 with 95% CIs [.81, .95], [.73, .92], and [.84, .95].

Data Analysis Procedure

Morris used the IBM SPSS Version 28 software package to analyze the data for this study. To examine if the MBSP group intervention (i.e., treatment condition) had any effect on the three dependent variables (i.e., relationship satisfaction, dispositional [trait] mindfulness, and well-being) over time, Morris analyzed the data using repeated measures analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA). Data was entered on an Excel spreadsheet from Qualtrics and exported to SPSS for a series of repeated measures analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA) models to include non-parametric tests such as the Friedman test. The Pearson product moment correlation coefficients were calculated to examine the relationships between the gain scores for relationship satisfaction, mindfulness, and overall well-being. The researcher checked for RM-ANOVA assumptions including (a) multivariate and univariate normality, (b) linearity, (c) multicollinearity, and (d) adequate sample size (Hahs-Vaughn & Lomax, 2020).

Results

Examining the effectiveness of the MBSP program on relationship satisfaction, dispositional trait mindfulness, and well-being, an analysis was conducted and revealed there was a positive relationship between relationship satisfaction, mindfulness, and well-being. Further analysis was provided through a one-way ANOVA repeated measure, and a Friedman test (a non-parametric) for the identified variables and assessment scores. A Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was computed to examine gain scores between dependent variables. Table 2 provides descriptive results over each time point measured at Week 1 (baseline), Week 4, and Week 8 for relationship satisfaction, mindfulness, and overall well-being.

Table 2

Pearson Correlation Among Relationship Satisfaction, Mindfulness, and Well-Being at Baseline, Week 4, and Week 8

| Variables |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

| 1. Relationship Satisfaction |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2. Mindfulness |

0.15 |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3. Well-Being |

.71* |

.53* |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 4. Relationship Satisfaction (Wk. 4) |

|

|

|

— |

|

|

|

|

|

| 5. Mindfulness (Wk. 4) |

|

|

|

.09 |

— |

|

|

|

|

| 6. Well-Being (Wk. 4) |

|

|

|

.61* |

.27 |

— |

|

|

|

| 7. Relationship Satisfaction (Wk. 8) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

— |

|

|

| 8. Mindfulness (Wk. 8) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.52* |

— |

|

| 9. Well-Being (Wk. 8) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.84* |

.59* |

— |

*p < .01.

Research Question 1

In answering RQ1, a one-way RM-ANOVA examined if there were significant changes in participants’ relationship satisfaction throughout the MBSP intervention program. The independence assumption was met because the study design measured each participant’s response only once at the time of the study. The normality assumption was shown to be violated, as the p-value for the Shapiro-Wilk normality test at Week 4 was statistically significant (Shapiro-Wilk = .88, p < .001). The sphericity assumption was met because Mauchly’s test of sphericity was not found to be statistically significant, 𝜒2 (2, N = 24) = 4.39, 𝑝 = .111. No significant change over time was found, F(2, 46) = 1.74, p = .187. Therefore, H1 was rejected, as data analysis failed to demonstrate a statistically significant change in pre- and post-intervention of the MBSP group intervention on relationship satisfaction. See Table 3.

Table 3

One-Way Repeated Measures ANOVA for Changes of Relationship Satisfaction Scores Over Time (RQ1)

| Source |

Measure |

SS |

df |

MS |

F |

p |

Partial Eta Squared |

| Time |

Sphericity Assumed |

52.78 |

2.00 |

26.39 |

1.74 |

0.19 |

0.07 |

|

Greenhouse-Geisser |

52.78 |

1.69 |

31.16 |

1.74 |

0.19 |

0.07 |

|

Huynh-Feldt |

52.78 |

1.81 |

29.10 |

1.74 |

0.19 |

0.07 |

|

Lower-bound |

52.78 |

1.00 |

52.78 |

1.74 |

0.20 |

0.07 |

| Error |

Sphericity Assumed |

697.89 |

46.00 |

15.17 |

|

|

|

|

Greenhouse-Geisser |

697.89 |

38.96 |

17.92 |

|

|

|

|

Huynh-Feldt |

697.89 |

41.72 |

16.73 |

|

|

|

|

Lower-bound |

697.89 |

23.00 |

30.34 |

|

|

|

Research Question 2

In answering RQ2, a one-way RM-ANOVA examined whether participants’ mindfulness scores significantly changed throughout the MBSP intervention program. The normality assumption was shown to be violated because the p-value for the Shapiro-Wilk normality test at week 8 was statistically significant (Shapiro-Wilk = .82, p < .001). The sphericity assumption was found to be met because the sphericity statistic was not found to be statistically significant, 𝜒 2 (2, N = 24) = .78, 𝑝 = .676. Because of the non-normal data, a Friedman test (a non-parametric version of a one-way ANOVA) was implemented. The Friedman test results showed no significant change in mindfulness scores 𝜒 2 (2, N = 24) = 5.32, 𝑝 = .069. Therefore, H2 was rejected, as data analysis failed to demonstrate a statistically significant change in pre- and post-intervention of the MBSP group intervention on mindfulness (traits).

Research Question 3

In answering RQ3, a one-way RM-ANOVA examined whether participants’ overall well-being scores significantly changed throughout the MBSP intervention program. The normality assumption was met because the p-values for overall well-being scores for each time period were greater than .05. The sphericity assumption was found to be met because the sphericity statistic was found to be statistically significant 𝜒 2 (2, N =24) = 6.41, 𝑝 = .041. The Greenhouse-Geisser correction was implemented due to the sphericity assumption violation. The one-way ANOVA results found no significant change over time, 𝐹(1.60, 36.72) = 2.63, 𝑝 = .096. Therefore, H3 was rejected, as data analysis failed to demonstrate a statistically significant change in pre- and post-intervention of the MBSP program for overall well-being. See Table 4.

Table 4

One-Way Repeated Measures ANOVA for Changes of Overall Well-Being Scores Over Time (RQ3)

| Source |

Measure |

SS |

df |

MS |

F |

p |

Partial Eta Squared |

| Time |

Sphericity Assumed |

3.05 |

2.00 |

1.52 |

2.63 |

0.08 |

0.10 |

|

Greenhouse-Geisser |

3.05 |

1.60 |

1.91 |

2.63 |

0.10 |

0.10 |

|

Huynh-Feldt |

3.05 |

1.70 |

1.80 |

2.63 |

0.09 |

0.10 |

|

Lower-bound |

3.05 |

1.00 |

3.05 |

2.63 |

0.12 |

0.10 |

| Error |

Sphericity Assumed |

26.68 |

46.00 |

0.58 |

|

|

|

|

Greenhouse-Geisser |

26.68 |

36.72 |

0.73 |

|

|

|

|

Huynh-Feldt |

26.68 |

39.02 |

0.68 |

|

|

|

|

Lower-bound |

26.68 |

23.00 |

1.16 |

|

|

|

A Pearson’s correlation coefficient was calculated to assess the bivariate relationships between relationship satisfaction, mindfulness, and well-being. Well-being was shown to be positively associated with relationship satisfaction (r (22) =.71, p < .001) and mindfulness (r (22) = .53, p = .007). At Week 4 of the intervention, well-being was positively associated with relationship satisfaction (r (22) =.61, p =.002). At Week 8 of the intervention, well-being was shown to be positively associated with relationship satisfaction (r (22) =.84, p < .001) and mindfulness (r (22) = .59, p =.003). Mindfulness was positively associated with relationship satisfaction (r (22) = .52, p = .009). See Table 2.

Process Observation Results

The function of process observation, as described by Yalom and Leszcz (2020), is carried out by one of the group facilitators, referred to as the process observer (i.e., CIT). The process observer’s role is to observe the interaction and behaviors of the group (Yalom & Leszcz, 2020). Because the group was online, it was recommended to have a process observer, as it can help gain insight into the interpersonal interactions of group members (Prasath et al., 2023). In this study the process observer (CIT) took notes during the MBSP group and noted processes, behaviors of members, and group dynamics. In summary, they noted that most participants shared experiences and engaged in mindfulness and strengths activities, whether meditations or character strengths exercises. Additionally, the process observer noticed that the participants started to be less distracted during the mindfulness exercises after Week 4 of the MBSP group.

Discussion

The current study investigated MBSP program effectiveness with adult female survivors of MST, examining changes in relationship satisfaction, mindfulness, and well-being. In determining the efficacy of the MBSP program on female survivors of MST, Morris made several assumptions. Some assumptions were validated, and others were not. There was some congruence between previous literature and the current study. Findings are discussed based on the hypotheses in three areas: positive relationship between relationship satisfaction and the MBSP program, improvement in mindfulness practice, and improvement in well-being because of the MBSP program.

Positive Relationship Between Relationship Satisfaction and the MBSP Program

In line with previous studies, results reveal a similar positive change in mindfulness, showing that as mindfulness practice increased, so did relationship satisfaction and well-being, as reported by the participants during some part of the group intervention. It is not surprising that participants of this study reported some increase in mindfulness as a dispositional trait at the end of the intervention, because the MBSP program regularly incorporates several mindfulness practices, particularly meditative practices (i.e., mindful listening, walking, eating, breathing, listening, speaking, and self-compassion), during the session and for homework. This is not unusual, as there is abundant literature on mindfulness practices indicating benefits for trauma survivors (Hofmann et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2019). Mindfulness practices with individuals impacted by trauma have revealed an improvement in self-regulation of emotions, PTSD symptoms, interpersonal relationships, and overall well-being (Hofmann et al., 2020; Shankland et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2019).

Improvement in Well-Being Because of the MBSP Program

Consistent with previous studies, the MBSP program shows positive influence on well-being (Pang & Ruch, 2019; Whelan-Berry & Niemiec, 2021; Wingert et al., 2022). In the current study, well-being was shown to be positively associated with relationship satisfaction; as one increased, so did the other. From Week 1 to Week 4, well-being increased but did not hold statistical significance throughout the study. Results also reveal that participants struggled with completing homework tasks such as strength activities because of outside priorities, which has been mentioned in a previous study (Whelan-Berry & Niemiec, 2021). Thus, the results may have been affected, with no positive outcome at the end of the intervention for well-being.

Additional Significant Results

In the context of the MBSP program, the study reveals a slight increase in participants’ relationship satisfaction, well-being, and mindfulness from baseline to 4 weeks, followed by a plateau from Week 4 to Week 8. This apparent plateau may be attributed to a ceiling effect, in which the MBSP program’s influence on these dependent variables reached a saturation point (Chyung et al., 2020). Notably, the COVID-19 pandemic introduced a unique external factor impacting the study’s results, as previous MBSP studies occurred pre-pandemic. This study was conducted online, mirroring a broader shift toward virtual counseling services (e.g., Zoom) during the pandemic, potentially influencing participant experiences and outcomes (Kadafi et al., 2021).

Implications for Counselors

In the Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs 2016 standards (CACREP; 2015), there’s a notable gap, as few programs teach non-trauma modalities like positive psychology and mindfulness-based practices to address trauma survivor symptoms. The lack of CACREP guidance on crisis, trauma, and disaster counseling has necessitated creative pedagogical approaches to present realistic clinical challenges to CITs in a supportive and safe learning environment (Greene et al., 2016). This could help counselor educators develop innovative wellness tools and support for clients seeking non-pathology–based treatment. Therefore, it is recommended that CACREP establish standards to incorporate these alternative modalities, as the current CACREP standards focus on crisis intervention, trauma-informed, community-based, and disaster mental health strategies. Additionally, counselor educators can teach the MBSP intervention to students, which incorporates mindfulness and the VIA Character Strengths, which have been shown to build strengths, help with anxiety, and increase confidence; likewise, mindfulness can be beneficial during supervision (Evans et al., 2024, Niemiec, 2014). The VIA Character Strengths survey can aid educators in guiding students toward self-awareness of emotions, identifying strength, and identifying theoretical orientations aligning with their values (Sharp & Rhinehart, 2018).

The study reveals a positive correlation between relationship satisfaction, mindfulness, and well-being scores during the intervention. Adapting the MBSP program to a shorter duration for trauma survivors may be beneficial in future interventions. Existing literature on veterans with PTSD symptoms recommends incorporating wellness-based models like positive psychology in rehabilitation, with consideration for the timing and severity of trauma experiences (Carrola & Corbin-Burdick, 2015). For participants with varying recency and types of traumas, the MBSP program’s impact varied, indicating the importance of trauma processing before non-pathological treatments. Despite statistically insignificant outcomes, the study provides valuable mindfulness skills and character strength utilization for participants, offering practical tools for improving relationships for both clients and counselors. This research contributes insights into tailoring interventions for interpersonal traumas, enabling the development of non-pathological, preventive approaches utilizing positive psychology and mindfulness techniques to enhance the well-being of trauma survivors.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

The research study has several limitations, including the use of a quasi-experimental design that posed threats to internal and external validity. The absence of a control group and issues with the relationship satisfaction scale’s design could have impacted the study’s results. Self-report and social desirability biases may have been present, especially among the 33% of respondents who were previous clients of the researcher and first author. The small sample size due to convenience sampling (N = 24) raises concerns about generalizability and the risk of Type II errors. Participant attrition further reduced the sample size and validity. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic introduced confounding factors, as previous studies on the intervention were conducted under different conditions. Zoom fatigue, resulting from increased online counseling services, also may have influenced participant experiences. Despite these limitations, a slight improvement in relationship satisfaction, well-being, and mindfulness was observed, possibly due to a ceiling effect. Although addressing these limitations is crucial, the study’s findings hold potential for enhancing counseling practice and research in the field.

Miller and Le Borgne (2020) suggested that further research is needed to evaluate the MBSP program’s effectiveness for enhancing the well-being and relationship satisfaction of MST survivors. This could involve larger sample sizes, addressing social desirability biases, and extending program exposure. A tailored relationship satisfaction assessment for trauma survivors should be developed, and qualitative investigations into post-MBSP program experiences are recommended. The program’s impact on symptoms like anxiety, depression, insomnia, and PTSD should be explored, not only for MST survivors but also for those with different trauma experiences. Couple satisfaction within the program context should be studied, and alternative program formats, such as shorter, intensive sessions or in-person delivery, should be considered. Changing the clinical environment and conducting long-term follow-up assessments are also suggested to enhance the study’s validity. These steps can improve the applicability of the MBSP program for supporting the well-being and relationships of trauma survivors.

Conclusion

This study investigated the impact of the MBSP program on female survivors of MST, examining their relationship satisfaction, dispositional mindfulness, and overall well-being. A total of 31 participants were initially recruited, with 24 completing all study requirements. Data analysis involved various statistical tests. Although statistical significance was not consistently demonstrated, a significant positive correlation was found between relationship satisfaction and mindfulness, and well-being and relationship satisfaction. These findings raise questions about the suitability of the MBSP program for trauma survivors, necessitating further exploration of relevant factors in this context.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

Data collected and content shared in this article

were part of a dissertation study, which was

awarded the 2023 Dissertation Excellence Award

in Quantitative Research by The Professional Counselor

and the National Board for Certified Counselors.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th edition). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., Segal, Z. V., Abbey, S., Speca, M., Velting, D., & Devins, G. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 230–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bph077

Blais, R. K. (2019). Lower sexual satisfaction and function mediate the association of assault military sexual trauma and relationship satisfaction in partnered female service members/veterans. Family Process, 59(2), 586–596. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12449

Blais, R. K. (2020). Higher anhedonia and dysphoric arousal relate to lower relationship satisfaction among trauma-exposed female service members/veterans. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 76(7), 1327–1338. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22937

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822

Brown, W. J., Hetzel-Riggin, M. D., Mitchell, M. A., & Bruce, S. E. (2021). Rumination mediates the relationship between negative affect and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in female interpersonal trauma survivors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(13–14), 6418–6439. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518818434

Brownstone, L. M., Holliman, B. D., Gerber, H. R., & Monteith, L. L. (2018). The phenomenology of military sexual trauma among women veterans. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 42(4), 399–413. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684318791154

Burek, G. (2018). Military culture: Working with veterans. American Journal of Psychiatry Residents’ Journal, 13(9), 3–5. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp-rj.2018.130902

Butler, J., & Kern, M. L. (2016). The PERMA-Profiler: A brief multidimensional measure of flourishing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 6(3), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v6i3.526

Campbell, S. B., & Renshaw, K. D. (2018). Posttraumatic stress disorder and relationship functioning: A comprehensive review and organizational framework. Clinical Psychology Review, 65, 152–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2018.08.003

Carrola, P., & Corbin-Burdick, M. (2015). Counseling military veterans: Advocating for culturally competent and holistic interventions. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 37(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.37.1.v74514163rv73274

Cebolla, A., Enrique, A., Alvear, D., Soler, J. M, & Garcia-Campayo, J. J. (2017). Contemplative positive psychology: Introducing mindfulness into positive psychology. Papeles Del Psicólogo, 38(1), 12–18. https://www.papelesdelpsicologo.es/English/2816.pdf

Chyung, S. Y., Hutchinson, D., & Shamsy, J. A. (2020). Evidence-based survey design: Ceiling effects associated with response scales. Performance Improvement, 59(6), 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/pfi.21920

Cohen, M. P. (1998). Determining sample sizes for surveys with data analyzed by hierarchical linear models. Journal of Official Statistics, 14(3), 267–275.

Corey, M. S., Corey, G., & Corey, C. (2018). Groups: Process and practice (10th ed). Cengage.

Costello, K. (2022). Distress tolerance and institutional betrayal factors related to posttraumatic stress outcomes in military sexual trauma (MST) (Publication No. 29322504) [Doctoral dissertation, Hofstra University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2015). 2016 CAREP standards. https://www.cacrep.org/for-programs/2016-cacrep-standards

Department of Veterans Affairs. (2021). Women and military sexual trauma. https://www.research.va.gov/topics/womens_health.cfm#research6

Duffy, J. R., Thomas, M. L., Bormann, J., & Lang, A. J. (2022). Psychometric comparison of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale and the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire in veterans treated for posttraumatic stress disorder. Mindfulness, 13(9), 2202–2214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-01948-x

Evans, A., Griffith, G. M., & Smithson, J. (2024). What do supervisors’ and supervisees’ think about mindfulness-based supervision? A grounded theory study. Mindfulness, 15, 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-023-02280-8

Fallahchai, R., Fallahi, M., Chahartangi, S., & Bodenmann, G. (2019). Psychometric properties and factorial validity of the Dyadic Coping Inventory–the Persian Version. Current Psychology, 38, 486–496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-017-9624-6

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Georgia, E. J., Roddy, M. K., & Doss, B. D. (2018). Sexual assault and dyadic relationship satisfaction: Indirect associations through intimacy and mental health. Violence Against Women, 24(8), 936–951. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801217727371

Gibson, C. J., Gray, K. E., Katon, J. G., Simpson, T. L., & Lehavot, K. (2016). Sexual assault, sexual harassment, and physical victimization during military service across age cohorts of women veterans. Women’s Health Issues, 26(2), 225–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2015.09.013

Goodman, F. R., Disabato, D. J., Kashdan, T. B., & Kauffman, S. B. (2018). Measuring well-being: A comparison of subjective well-being and PERMA. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 13(4), 321–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2017.1388434

Greene, C. A., Williams, A. E., Harris, P. N., Travis, S. P., & Kim, S. Y. (2016). Unfolding case-based practicum curriculum infusing crisis, trauma, and disaster preparation. Counselor Education and Supervision, 55(3), 216–232. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12046

Hahs-Vaughn, D. L., & Lomax, R. G. (2020). Statistical concepts: A first course. Routledge.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. (2018). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed.). Cengage.

Hayden, L. C., Schiller, M., Dickstein, S., Seifer, R., Sameroff, S., Miller, I., Keitner, G., & Rasmussen, S. (1998). Levels of family assessment: I. Family, marital, and parent–child interaction. Journal of Family Psychology, 12(1), 7–22. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.12.1.7

Hendrick, S. S. (1988). A generic measure of relationship satisfaction. Journal of Marriage and Family, 50(1), 93–98. https://doi.org/10.2307/352430

Hendrick, S. S., Dicke, A., & Hendrick, C. (1998). The Relationship Assessment Scale. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 15(1), 137–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407598151009

Hofmann, J., Heintz, S., Pang, D., & Ruch, W. (2020). Differential relationships of light and darker forms of humor with mindfulness. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 15(2), 369–393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9698-9

Ivtzan, I., Niemiec, R. M., & Briscoe, C. (2016). A study investigating the effects of Mindfulness-Based Strengths Practice (MBSP) on wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 6(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v6i2.557

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. Dell Publishing.

Kadafi, A., Alfaiz, A., Ramli, M., Asri, D. N., & Finayanti, J. (2021). The impact of Islamic counseling intervention towards students’ mindfulness and anxiety during the Covid-19 pandemic. Islamic Guidance and Counseling Journal, 4(1), 55–66.

Kintzle, S., Schuyler, A. C., Ray-Letourneau, D., Ozuna, S. M., Munch, C., Xintarianos, E., Hasson, A. M., & Castro, C. A. (2015). Sexual trauma in the military: Exploring PTSD and mental health care utilization in female veterans. Psychological Services, 12(4), 394–401. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000054

Litz, B. T. (2014). Clinical heuristics and strategies for service members and veterans with war-related PTSD. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 31(2), 192–205. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036372

Mahamid, F., Veronese, G., & Bdier, D. (2023). The factorial structure and psychometric properties of the PERMA-Profiler Arabic version to measure well-being within a Palestinian adult population. Middle East Current Psychiatry, 30(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-023-00282-9

Maroufizadeh, S., Omani-Samani, R., Hosseini, M., Almasi-Hashiani, A., Sepidarkish, M., & Amini, P. (2020). The Persian version of the Revised Dyadic Adjustment Scale (RDAS): A validation study in infertile patients. BMC Psychology, 8, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-0375-z

Meinert, E. K., & Wentz, E. A. (2024). Protecting but not protected: Sexual assault in the military. Victims & Offenders, 19(4), 671–691. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2023.2299007

Miller, M., & Le Borgne, A. (2020, July 7). Statistical significance: How to validate your incrementality test results. Adikteev. https://www.adikteev.com/blog/statistical-significance-how-to-validate-your-incrementality-test-results

Morris, C. M. (2022). Silent no more: Exploring the effects of mindfulness-based strengths practice on relationship satisfaction, mindfulness, and well-being in female survivors of military sexual trauma (Publication No. 30000181) [Doctoral dissertation, The University of Texas at San Antonio]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Neff, K. D. (2011). Self-compassion, self-esteem, and well-being. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00330.x

Niemiec, R. M. (2013). VIA character strengths: Research and practice (The first 10 years). In H. H. Knoop & A. Delle Fave (Eds.), Well-being and cultures: Perspectives on positive psychology (pp. 11–30). Springer.

Niemiec, R. M. (2014). Mindfulness and character strengths: A practical guide to flourishing. Hogrefe.

Pang, D., & Ruch, W. (2019). Fusing character strengths and mindfulness interventions: Benefits for job satisfaction and performance. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 24(1), 150–162. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000144

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. American Psychological Association.

Phang, C.-K., Mukhtar, F., Ibrahim, N., & Mohd. Sidik, S. (2016). Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS): Factorial validity and psychometric properties in a sample of medical students in Malaysia. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 11(5), 305–316. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMHTEP-02-2015-0011

Prasath, P. R., Morris, C., & Maccombs, S. (2021). Mindfulness-Based Strengths Practice (MBSP) group intervention: A systematic review. Journal of Counselor Practice, 12(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.22229/asy1212021

Prasath, P. R., Xiong, Y., & Zhang, Q. (2023). A practical guide to planning, implementing, and evaluating the mindfulness-based well-being group for international students. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 63, 214–227. https://doi.org/10.1002/johc.12200

Ryan, J., Curtis, R., Olds, T., Edney, S., Vandelanotte, C., Plotnikoff, R., & Maher, C. (2019). Psychometric properties of the PERMA Profiler for measuring wellbeing in Australian adults. PloS ONE, 14(12), e0225932. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225932

Salzberg, S. (1995). Lovingkindness: The revolutionary art of happiness. Shambhala Publications.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2012). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Simon and Schuster.

Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5

Shankland, R., Tessier, D., Strub, L., Gauchet, A., & Baeyens, C. (2021). Improving mental health and well-being through informal mindfulness practices: An intervention study. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 13(1), 63–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12216

Sharp, J. E., & Rhinehart, A. J. (2018). Infusing mindfulness and character strengths in supervision to promote beginning supervisee development. Journal of Counselor Practice, 9(1), 64–80. https://www.journalofcounselorpractice.com/uploads/6/8/9/4/68949193/sharp_rhinehart_vol9_iss1.pdf

Thompson, J. M., MacLean, M. B., Roach, M. B., Banman, M., Mabior, J., & Pedlar, D. (2016). A well-being construct for veterans’ policy, programming and research (Technical Report). Research Directorate, Veterans Affairs Canada. https://cimvhr.ca/vacreports/data/reports/Thompson%202016_WellBeing%20Construct%20for%20Veterans%20policy,%20programming,%20and%20research.pdf

Topkaya, N., Şahin, E., & Mehel, F. (2023). Relationship-specific irrational beliefs and relationship satisfaction in intimate relationships. Current Psychology, 42(2), 1257–1269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01426-y

Umucu, E., Wu, J.-R., Sanchez, J., Brooks, J. M., Chiu, C.-Y., Tu, W.-M., & Chan, F. (2020). Psychometric validation of the PERMA-Profiler as a well-being measure for student veterans. Journal of American College Health, 68(3), 271–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2018.1546182

VIA Institute on Character. (2019). The VIA Character Strengths Survey. https://www.viacharacter.org/survey/account/register

Wagner, L., Gander, F., Proyer, R. T., & Ruch, W. (2020). Character strengths and PERMA: Investigating the relationships of character strengths with a multidimensional framework of well-being. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 15(2), 307–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9695-z

Whelan-Berry, K., & Niemiec, R. (2021). Integrating mindfulness and character strengths for improved well-being, stress, and relationships: A mixed-methods analysis of Mindfulness-Based Strengths Practice. International Journal of Wellbeing, 11(1), 38–50. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v11i2.1545

Wilson, L. C. (2018). The prevalence of military sexual trauma: A meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 19(5), 584–597. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838016683459

Wingert, J. R., Jones, J. C., Swoap, R. A., & Wingert, H. M. (2022). Mindfulness-based strengths practice improves well-being and retention in undergraduates: A preliminary randomized controlled trial. Journal of American College Health, 70(3), 783–790. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2020.1764005

World Health Organization. (2021). Violence against women. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

Yalom, I. D., & Leszcz, M. (2020). The theory and practice of group psychotherapy (6th ed.). Basic Books.

Zhu, J., Wekerle, C., Lanius, R., & Frewen, P. (2019). Trauma- and stressor-related history and symptoms predict distress experienced during a brief mindfulness meditation sitting: Moving toward trauma-informed care in mindfulness-based therapy. Mindfulness, 10, 1985–1996. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01173-z

Crystal M. Morris, PhD, NCC, CSC, LPC-S, is an assistant professor at St. Mary’s University. Priscilla Rose Prasath, PhD, MBA, LPC, GCSC, is an associate professor at The University of Texas at San Antonio. Correspondence may be addressed to Crystal M. Morris, St. Mary’s University, One Camino Santa Maria, San Antonio, TX 78228, cmorris4@stmarytx.edu.

Feb 26, 2021 | Volume 11 - Issue 1

Priscilla Rose Prasath, Peter C. Mather, Christine Suniti Bhat, Justine K. James

This study examined the relationships between psychological capital (PsyCap), coping strategies, and well-being among 609 university students using self-report measures. Results revealed that well-being was significantly lower during COVID-19 compared to before the onset of the pandemic. Multiple linear regression analyses indicated that PsyCap predicted well-being, and structural equation modeling demonstrated the mediating role of coping strategies between PsyCap and well-being. Prior to COVID-19, the PsyCap dimensions of optimism and self-efficacy were significant predictors of well-being. During the pandemic, optimism, hope, and resiliency have been significant predictors of well-being. Adaptive coping strategies were also conducive to well-being. Implications and recommendations for psychoeducation and counseling interventions to promote PsyCap and adaptive coping strategies in university students are presented.

Keywords: university students, psychological capital, well-being, coping strategies, COVID-19

In January 2020, the World Health Organization declared the outbreak of a new coronavirus disease, COVID-19, to be a public health emergency of international concern, and the effects continue to be widespread and ongoing. For university students, the pandemic brought about disruptions to life as they knew it. For example, students had to stay home, adapt to online learning, modify internship placements, and/or reconsider graduation plans and jobs. The aim of this study was to understand how the sudden changes and uncertainty resulting from the pandemic affected the well-being of university students during the early period of the pandemic. Specifically, the study addresses coping strategies and psychological capital (PsyCap; F. Luthans et al., 2007) and how they relate to levels of well-being.

University Students and Mental Health

Although mental health distress has been an issue on college campuses prior to the pandemic (Flatt, 2013; Lipson et al., 2019), COVID-19 has and will continue to magnify this phenomenon. Experts are projecting increases in depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicide in the United States (Wan, 2020). Johnson (2020) indicated that 35% of students reported increased anxiety associated with a move from face-to-face to online learning in the spring 2020 semester, matching the early phases of the COVID-19 outbreak. Stress associated with adapting to online learning presented particular challenges for students who did not have adequate internet access in their homes (Hoover, 2020).

Researchers have reported that high levels of technology and social media use are associated with depression and anxiety among adolescents and young adults (Huckins et al., 2020; Primack et al., 2017; Twenge, 2017). Given the current realities of physical distancing, there are fewer opportunities for traditional-age university students attending primarily residential campuses to maintain social connections, resulting in social fragmentation and isolation. Research has demonstrated that this exacerbates existing mental health concerns among university students (Klussman et al., 2020).

The uncertainties arising from COVID-19 have added to anticipatory anxiety regarding the future (Ray, 2019; Witters & Harter, 2020). From the Great Depression to 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina, victims of these life-shattering events have had to deal with their present circumstances and were also left with worries about how life and society would be inexorably altered in the future. University students are dealing with uncertain current realities and futures and may need to bolster their internal resources to face the challenges ahead. In this context, positive coping strategies and PsyCap may be increasingly valuable assets for university students to address the psychological challenges associated with this pandemic and to maintain or enhance their well-being.

Coping Strategies

Coping is often defined as “efforts to prevent or diminish the threat, harm, and loss, or to reduce associated distress” (Carver & Connor-Smith, 2010, p. 685). There are many ways to categorize coping responses (e.g., engagement coping and disengagement coping, problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping, accommodative coping and meaning-focused coping, proactive coping). Engagement coping includes problem-focused coping and some forms of emotion-focused coping, such as support seeking, emotion regulation, acceptance, and cognitive restructuring. Disengagement coping includes responses such as avoidance, denial, and wishful thinking, as well as aspects of emotion-focused coping, because it involves an attempt to escape feelings of distress (Carver & Connor-Smith, 2010; de la Fuente et al., 2020). Findings on the effectiveness of problem-focused coping strategies versus emotion-focused coping strategies suggest the effectiveness of the particular strategy is contingent on the context, with controllable issues being better addressed through problem-focused strategies, while emotion-focused strategies are more effective with circumstances that cannot be controlled (Finkelstein-Fox & Park, 2019). In general, problem-focused coping strategies, also known as adaptive coping strategies, include planning, active coping, positive reframing, acceptance, and humor (Carver & Connor-Smith, 2010). Other coping strategies, such as denial, self-blame, distraction, and substance use, are more often associated with negative emotions, such as shame, guilt, lower perception of self-efficacy, and psychological distress, rather than making efforts to remediate them (Billings & Moos, 1984). These strategies can be harmful and unhealthy with regard to effectively coping with stressors. Researchers have recommended coping skills training for university students to modify maladaptive coping strategies and enhance pre-existing adaptive coping styles to optimal levels (Madhyastha et al., 2014).

Flourishing: The PERMA Well-Being Model

Positive psychologists have asserted that studies of wellness and flourishing are important in understanding adaptive behaviors and the potential for growth from challenging circumstances (Joseph & Linley, 2008; Seligman, 2011). Flourishing (or well-being) is defined as “a dynamic optimal state of psychosocial functioning that arises from functioning well across multiple psychosocial domains” (Butler & Kern, 2016, p. 2). Seligman (2011) proposed a theory of well-being stipulating that well-being was not simply the absence of mental illness (Keyes, 2002), but also the presence of five pillars with the acronym of PERMA (Seligman, 2002, 2011). The first pillar, positive emotion (P), is the affective component comprising the feelings of joy, hope, pleasure, rapture, happiness, and contentment. Next are engagement (E), the act of being highly interested, absorbed, or focused in daily life activities, and relationships (R), the feelings of being cared about by others and authentically and securely connected to others. The final two pillars are meaning (M), a sense of purpose in life that is derived from something greater than oneself, and accomplishment (A), a persistent drive that helps one progress toward personal goals and provides one with a sense of achievement in life. Seligman’s (2011) PERMA model is one of the most highly regarded models of well-being.

Seligman’s multidimensional model integrates both hedonic and eudaimonic views of well-being, and each of the well-being components is seen to have the following three properties: (a) it contributes to well-being, (b) it is pursued for its own sake, and (c) it is defined and measured independently from the other components (Seligman, 2011). Studies show that all five pillars of well-being in the PERMA model are associated with better academic outcomes in students, such as improved college life adjustment, achievement, and overall life satisfaction (Butler & Kern, 2016; DeWitz et al., 2009; Tansey et al., 2018). Additionally, each pillar of PERMA has been shown to be positively associated with physical health, optimal well-being, and life satisfaction and negatively correlated with depression, fatigue, anxiety, perceived stress, loneliness, and negative emotion (Butler & Kern, 2016). At a time of significant stress, promoting the highest human performance and adaptation not only helps with well-being in the midst of the challenge but also can provide a foundation for future potential for optimal well-being (Joseph & Linley, 2008).

Psychological Capital (PsyCap)

PsyCap is a state-like construct that consists of four dimensions: hope (H), self-efficacy (E), resilience (R), and optimism (O), often referred to by the acronym HERO (F. Luthans et al., 2007). F. Luthans et al. (2007) developed PsyCap from research in positive organizational behavior and positive psychology. PsyCap is defined as an

individual’s positive psychological state of development characterized by (1) having confidence (self-efficacy) to take on and put in the necessary effort to succeed at challenging tasks; (2) making a positive attribution (optimism) about succeeding now and in the future; (3) persevering toward goals and, when necessary, redirecting paths to goals (hope) in order to succeed; and (4) when beset by problems and adversity, sustaining and bouncing back and even beyond (resilience) to attain success. (F. Luthans et al., 2015, p. 2)

Over the past decade, PsyCap has been applied to university student development and mental health. There is robust empirical support suggesting that individuals with higher PsyCap have higher levels of performance (job and academic); satisfaction; engagement; attitudinal, behavioral, and relational outcomes; and physical and psychological health and well-being outcomes. Further, they have negative associations with stress, burnout, negative health outcomes, and undesirable behaviors at the individual, team, and organizational levels (Avey, Reichard, et al., 2011; Newman et al., 2014). Researchers have also examined the mediating role of PsyCap in the relationship between positive emotion and academic performance (Carmona-Halty et al., 2019; Hazan Liran & Miller, 2019; B. C. Luthans et al., 2012; K. W. Luthans et al., 2016); relationships and predictions between PsyCap and mental health in university students (Selvaraj & Bhat, 2018); and relationships between PsyCap, well-being, and coping (Rabenu et al., 2017).

Aim of the Study and Research Questions

The aim of the current study was to examine the relationships among well-being in university students before and during the onset of COVID-19 with PsyCap and coping strategies. The following research questions guided our work:

- Is there a significant difference in the well-being of university students prior to the onset of COVID-19 (reported retrospectively) and after the onset of COVID-19?

- What is the predictive relationship of PsyCap on well-being prior to the onset of COVID-19 and after the onset of COVID-19?

- Do coping strategies play a mediating role in the relationship between PsyCap and well-being?

Method

Participants

A total of 806 university students from the United States participated in the study. After cleaning the data, 197 surveys were excluded from the data analyses. Of the final 609 participants, 73.7% (n = 449) identified as female, 22% (n = 139) identified as male, and 4.3% (n = 26) identified as non-binary. The age of participants ranged from 18 to 66 (M = 27.36, SD = 9.9). Regarding race/ethnicity, most participants identified as Caucasian (83.6%, n = 509), while the remaining participants identified as African American (5.3%, n = 32), Hispanic or Latina/o (9.5%, n = 58), American Indian (0.8%, n = 5), Asian (3.6%, n = 22), or Other (2.7%, n = 17). Fifty-four percent of the participants were undergraduate students (n = 326), and the remaining 46% were graduate students (n = 283). The majority of the participants were full time students (82%, n = 498) compared to part-time students (18%, n = 111). Sixty-three percent of the students were employed (n = 384) and the remaining 37% were unemployed (n = 225).

Data Collection Procedures

After a thorough review of the literature, three standardized measures were identified for use in the study along with a brief survey for demographic information. Instruments utilized in the study measured psychological capital (Psychological Capital Questionnaire [PCQ-12]; Avey, Avolio et al., 2011), coping (Brief COPE; Carver, 1997), and well-being (PERMA-Profiler; Butler & Kern, 2016). Data were collected online in May and June 2020 using Qualtrics after obtaining approval from the IRBs of our respective universities. An invitation to participate, which included a link to an informed consent form and the survey, was distributed to all university students at two large U.S. public institutions in the Midwest and the South via campus-wide electronic mailing lists. The survey link was also distributed via a national counselor education listserv, and it was shared on the authors’ social media platforms. Participants were asked to complete the well-being assessment twice—first, by responding as they recalled their well-being prior to COVID-19, and second, by responding as they reflected on their well-being during the pandemic.

Instruments

Demographic Questionnaire

A brief questionnaire was used to capture participant information. The questionnaire included items related to age, gender, race/ethnicity, relationship status, education classification, and employment status.

Psychological Capital Questionnaire – Short Version (PCQ-12)

The PCQ-12 (Avey, Avolio et al., 2011), the shortened version of PCQ-24 (F. Luthans et al., 2007), consists of 12 items that measure four HERO dimensions: hope (four items), self-efficacy (three items), resilience (three items), and optimism (two items), together forming the construct of psychological capital (PsyCap). The PCQ-12 utilizes a 6-point Likert scale with response options ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients as a measure of internal consistency of the HERO subscales in the current study were high—hope (α = .86), self-efficacy (α = .86), resilience (α = .73), and optimism (α = .83)—consistent with the previous studies.

Brief COPE Questionnaire

Coping strategies were evaluated using the Brief COPE questionnaire (Carver, 1997), which is a short form (28 items) of the original COPE inventory (Carver et al., 1989). The Brief COPE is a multidimensional inventory used to assess the different ways in which people generally respond to stressful situations. This instrument is used widely in studies with university students (e.g., Madhyastha et al., 2014; Miyazaki et al., 2008). Fourteen conceptually differentiable coping strategies are measured by the Brief COPE (Carver, 1997): active coping, planning, using emotional support, using instrumental support, venting, positive reframing, acceptance, denial, self-blame, humor, religion, self-distraction, substance use, and behavioral disengagement. The 14 subscales may be broadly classified into two types of responses—“adaptive” and “problematic” (Carver, 1997, p. 98). Each subscale is measured by two items and is assessed on a 5-point Likert scale. Thus, in general, internal consistency reliability coefficients tend to be relatively smaller (α = .5 to .9).

PERMA-Profiler

The PERMA-Profiler (Butler & Kern, 2016) is a 23-item self-report measure that assesses the level of well-being across five well-being domains (i.e., positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, accomplishment) and additional subscales that measure negative emotion, loneliness, and physical health. Each item is rated on an 11-point scale ranging from never (0) to always (10), or not at all (0) to completely (10). The five pillars of well-being are defined and measured separately but are correlated constructs that together are considered to result in flourishing (Seligman, 2011). A single overall flourishing score provides a global indication of well-being, and at the same time, the domain-specific PERMA scores provide meaningful and practical benefits with regard to the possibility of targeted interventions. The measure demonstrates acceptable reliability, cross-time stability, and evidence for convergent and divergent validity (Butler & Kern, 2016). For the present study, reliability scores were high for four pillars—positive emotion (α = .88), relationships (α = .83), meaning (α = .89), accomplishment (α = .82); high for the subscales of negative emotion (α = .73) and physical health (α = .85); and moderate for the pillar of engagement (α = .65). The overall reliability coefficient of well-being items is very high (α = .94).

Data Analysis Procedure

The data were screened and analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, v25). Changes in PERMA elements were calculated by subtracting PERMA scores reported retrospectively by participants before the pandemic from scores reported at the time of data collection during COVID-19, and a repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted to examine the difference. Point-biserial correlation and Pearson product moment correlation coefficients were calculated to examine the relationships of demographic variables, PsyCap, and coping strategies with change in PERMA scores. Multivariate multiple regression was carried out to understand the predictive role of PsyCap on PERMA at two time points (before and during COVID-19). Structural equation modeling in Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS, v23) software was used to test the mediating role of coping strategies on the relationship between PsyCap and change in PERMA scores. Mediation models were carried out with bootstrapping procedure with a 95% confidence interval.

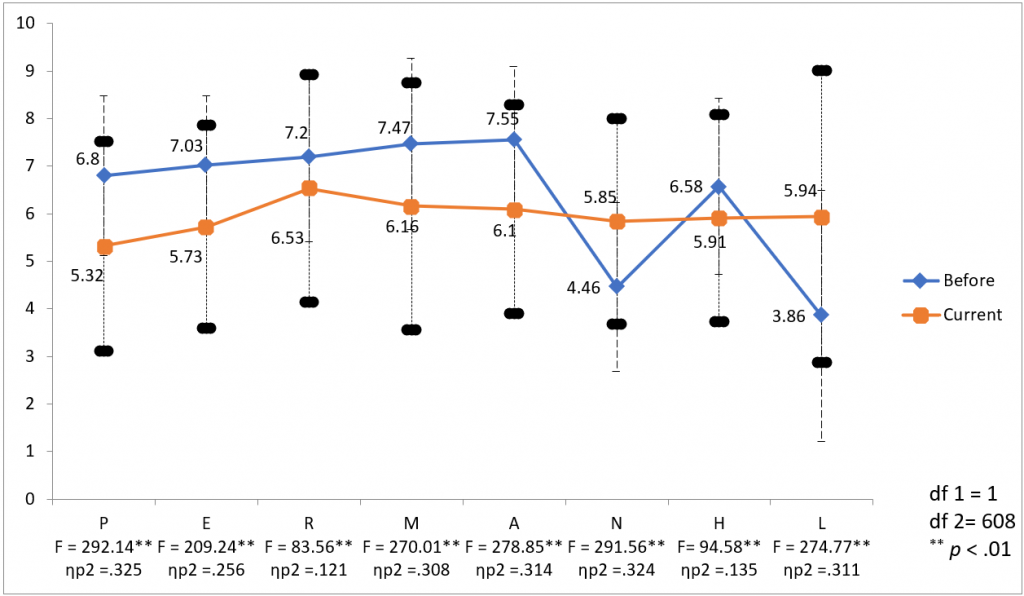

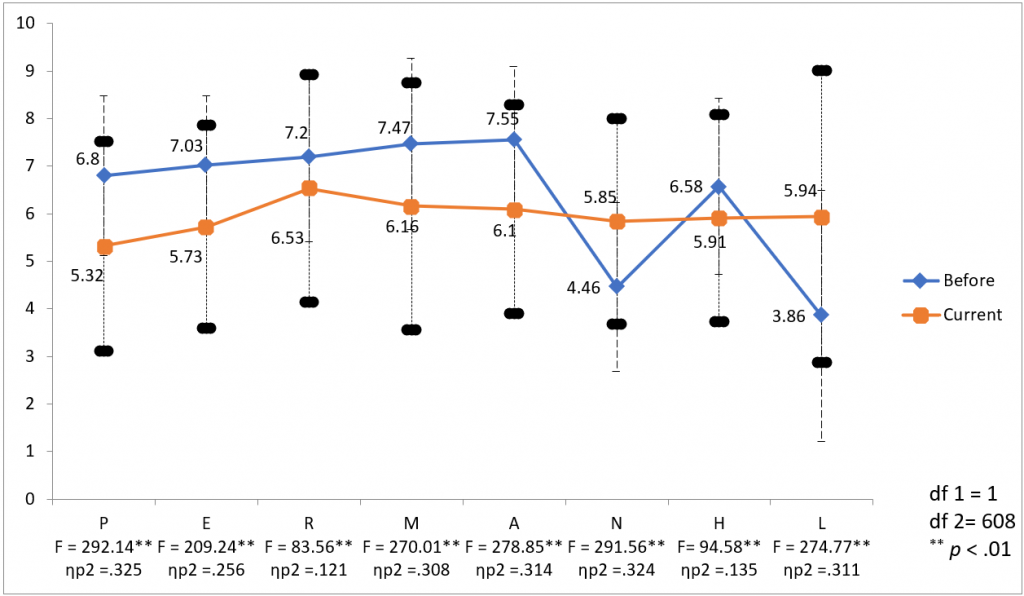

Results

Prior to exploring the role of PsyCap and coping strategies on change in well-being due to COVID-19, an initial analysis was conducted to understand the characteristics and relationships of constructs in the study. Correlation analyses (see Table 1) revealed significant and positive correlations between four PsyCap HERO dimensions (i.e., hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism; Avey, Avolio et al., 2011) and the six PERMA elements (i.e., positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, accomplishment, and physical health; Butler & Kern, 2016). Further, PsyCap HERO dimensions were negatively correlated to negative emotion and loneliness. Age was positively correlated with change in PERMA elements, but not gender. Similarly, approach coping strategies such as active coping, positive reframing, and acceptance (Carver, 1997) were resilient strategies to handle pandemic stress whereas using emotional support and planning showed weaker but significant roles. Similarly, religion also tended to be an adaptive coping strategy during the pandemic. Behavioral disengagement and self-blame (Carver, 1997) were found to be the dominant avoidant coping strategies that were adopted by students, which led to a significant decrease in well-being during the pandemic. Overall, as seen in Table 1, all three variables studied—PsyCap HERO dimensions, eight PERMA elements, and coping strategies—were highly related.

Table 1

Relationship of Demographic Factors, Psychological Capital, and Coping Strategies With Change in PERMA Elements

| Variables |

Mean |

SD |

P |

E |

R |

M |

A |

N |

H |

L |

| Age |

27.36 |

9.91 |

.15** |

.11** |

.14** |

.16** |

.14** |

.01 |

.03 |

-.17** |

| Course Ф |

– |

– |

.19** |

.10* |

.19** |

.16** |

.06 |

-.05 |

.09* |

-.14** |

| Nature of course Ф |

– |

– |

.06 |

.06 |

.12** |

.13** |

.09* |

.03 |

.03 |

-.10** |

| Gender Ф |

– |

– |

-.01 |

-.06 |

.01 |