Nov 9, 2022 | Volume 12 - Issue 3

Michael T. Kalkbrenner

Conducting and publishing rigorous empirical research based on original data is essential for advancing and sustaining high-quality counseling practice. The purpose of this article is to provide a one-stop-shop for writing a rigorous quantitative Methods section in counseling and related fields. The importance of judiciously planning, implementing, and writing quantitative research methods cannot be understated, as methodological flaws can completely undermine the integrity of the results. This article includes an overview, considerations, guidelines, best practices, and recommendations for conducting and writing quantitative research designs. The author concludes with an exemplar Methods section to provide a sample of one way to apply the guidelines for writing or evaluating quantitative research methods that are detailed in this manuscript.

Keywords: empirical, quantitative, methods, counseling, writing

The findings of rigorous empirical research based on original data is crucial for promoting and maintaining high-quality counseling practice (American Counseling Association [ACA], 2014; Giordano et al., 2021; Lutz & Hill, 2009; Wester et al., 2013). Peer-reviewed publication outlets play a crucial role in ensuring the rigor of counseling research and distributing the findings to counseling practitioners. The four major sections of an original empirical study usually include: (a) Introduction/Literature Review, (b) Methods, (c) Results, and (d) Discussion (American Psychological Association [APA], 2020; Heppner et al., 2016). Although every section of a research study must be carefully planned, executed, and reported (Giordano et al., 2021), scholars have engaged in commentary about the importance of a rigorous and clearly written Methods section for decades (Korn & Bram, 1988; Lutz & Hill, 2009). The Methods section is the “conceptual epicenter of a manuscript” (Smagorinsky, 2008, p. 390) and should include clear and specific details about how the study was conducted (Heppner et al., 2016). It is essential that producers and consumers of research are aware of key methodological standards, as the quality of quantitative methods in published research can vary notably, which has serious implications for the merit of research findings (Lutz & Hill, 2009; Wester et al., 2013).

Careful planning prior to launching data collection is especially important for conducting and writing a rigorous quantitative Methods section, as it is rarely appropriate to alter quantitative methods after data collection is complete for both practical and ethical reasons (ACA, 2014; Creswell & Creswell, 2018). A well-written Methods section is also crucial for publishing research in a peer-reviewed journal; any serious methodological flaws tend to automatically trigger a decision of rejection without revisions. Accordingly, the purpose of this article is to provide both producers and consumers of quantitative research with guidelines and recommendations for writing or evaluating the rigor of a Methods section in counseling and related fields. Specifically, this manuscript includes a general overview of major quantitative methodological subsections as well as an exemplar Methods section. The recommended subsections and guidelines for writing a rigorous Methods section in this manuscript (see Appendix) are based on a synthesis of (a) the extant literature (e.g., Creswell & Creswell, 2018; Flinn & Kalkbrenner, 2021; Giordano et al., 2021); (b) the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (American Educational Research Association [AERA] et al., 2014), (c) the ACA Code of Ethics (ACA, 2014), and (d) the Journal Article Reporting Standards (JARS) in the APA 7 (2020) manual.

Quantitative Methods: An Overview of the Major Sections

The Methods section is typically the second major section in a research manuscript and can begin with an overview of the theoretical framework and research paradigm that ground the study (Creswell & Creswell, 2018; Leedy & Ormrod, 2019). Research paradigms and theoretical frameworks are more commonly reported in qualitative, conceptual, and dissertation studies than in quantitative studies. However, research paradigms and theoretical frameworks can be very applicable to quantitative research designs (see the exemplar Methods section below). Readers are encouraged to consult Creswell and Creswell (2018) for a clear and concise overview about the utility of a theoretical framework and a research paradigm in quantitative research.

Research Design

The research design should be clearly specified at the beginning of the Methods section. Commonly employed quantitative research designs in counseling include but are not limited to group comparisons (e.g., experimental, quasi-experimental, ex-post-facto), correlational/predictive, meta-analysis, descriptive, and single-subject designs (Creswell & Creswell, 2018; Flinn & Kalkbrenner, 2021; Leedy & Ormrod, 2019). A well-written literature review and strong research question(s) will dictate the most appropriate research design. Readers can refer to Flinn and Kalkbrenner (2021) for free (open access) commentary on and examples of conducting a literature review, formulating research questions, and selecting the most appropriate corresponding research design.

Researcher Bias and Reflexivity

Counseling researchers have an ethical responsibility to minimize their personal biases throughout the research process (ACA, 2014). A researcher’s personal beliefs, values, expectations, and attitudes create a lens or framework for how data will be collected and interpreted. Researcher reflexivity or positionality statements are well-established methodological standards in qualitative research (Hays & Singh, 2012; Heppner et al., 2016; Rovai et al., 2013). Researcher bias is rarely reported in quantitative research; however, researcher bias can be just as inherently present in quantitative as it is in qualitative studies. Being reflexive and transparent about one’s biases strengthens the rigor of the research design (Creswell & Creswell, 2018; Onwuegbuzie & Leech, 2005). Accordingly, quantitative researchers should consider reflecting on their biases in similar ways as qualitative researchers (Onwuegbuzie & Leech, 2005). For example, a researcher’s topical and methodological choices are, at least in part, based on their personal interests and experiences. To this end, quantitative researchers are encouraged to reflect on and consider reporting their beliefs, assumptions, and expectations throughout the research process.

Participants and Procedures

The major aim in the Participants and Procedures subsection of the Methods section is to provide a clear description of the study’s participants and procedures in enough detail for replication (ACA, 2014; APA, 2020; Giordano et al., 2021; Heppner et al., 2016). When working with human subjects, authors should briefly discuss research ethics including but not limited to receiving institutional review board (IRB) approval (Giordano et al., 2021; Korn & Bram, 1988). Additional considerations for the Participants and Procedures section include details about the authors’ sampling procedure, inclusion and/or exclusion criteria for participation, sample size, participant background information, location/site, and protocol for interventions (APA, 2020).

Sampling Procedure and Sample Size

Sampling procedures should be clearly stated in the Methods section. At a minimum, the description of the sampling procedure should include researcher access to prospective participants, recruitment procedures, data collection modality (e.g., online survey), and sample size considerations. Quantitative sampling approaches tend to be clustered into either probability or non-probability techniques (Creswell & Creswell, 2018; Leedy & Ormrod, 2019). The key distinguishing feature of probability sampling is random selection, in which all prospective participants in the population have an equal chance of being randomly selected to participate in the study (Leedy & Ormrod, 2019). Examples of probability sampling techniques include simple random sampling, systematic random sampling, stratified random sampling, or cluster sampling (Leedy & Ormrod, 2019).

Non-probability sampling techniques lack random selection and there is no way of determining if every member of the population had a chance of being selected to participate in the study (Leedy & Ormrod, 2019). Examples of non-probability sampling procedures include volunteer sampling, convenience sampling, purposive sampling, quota sampling, snowball sampling, and matched sampling. In quantitative research, probability sampling procedures are more rigorous in terms of generalizability (i.e., the extent to which research findings based on sample data extend or generalize to the larger population from which the sample was drawn). However, probability sampling is not always possible and non-probability sampling procedures are rigorous in their own right. Readers are encouraged to review Leedy and Ormrod’s (2019) commentary on probability and non-probability sampling procedures. Ultimately, the selection of a sampling technique should be made based on the population parameters, available resources, and the purpose and goals of the study.

A Priori Statistical Power Analysis. It is essential that quantitative researchers determine the minimum necessary sample size for computing statistical analyses before launching data collection (Balkin & Sheperis, 2011; Sink & Mvududu, 2010). An insufficient sample size substantially increases the probability of committing a Type II error, which occurs when the results of statistical testing reveal non–statistically significant findings when in reality (of which the researcher is unaware), significant findings do exist. Computing an a priori (computed before starting data collection) statistical power analysis reduces the chances of a Type II error by determining the smallest sample size that is necessary for finding statistical significance, if statistical significance exists (Balkin & Sheperis, 2011). Readers can consult Balkin and Sheperis (2011) as well as Sink and Mvududu (2010) for an overview of statistical significance, effect size, and statistical power. A number of statistical power analysis programs are available to researchers. For example, G*Power (Faul et al., 2009) is a free software program for computing a priori statistical power analyses.

Sampling Frame and Location

Counselors should report their sampling frame (total number of potential participants), response rate, raw sample (total number of participants that engaged with the study at any level, including missing and incomplete data), and the size of the final useable sample. It is also important to report the breakdown of the sample by demographic and other important participant background characteristics, for example, “XX.X% (n = XXX) of participants were first-generation college students, XX.X% (n = XXX) were second-generation . . .” The selection of demographic variables as well as inclusion and exclusion criteria should be justified in the literature review. Readers are encouraged to consult Creswell and Creswell (2018) for commentary on writing a strong literature review.

The timeframe, setting, and location during which data were collected are important methodological considerations (APA, 2020). Specific names of institutions and agencies should be masked to protect their privacy and confidentiality; however, authors can give descriptions of the setting and location (e.g., “Data were collected between April 2021 to February 2022 from clients seeking treatment for addictive disorders at an outpatient, integrated behavioral health care clinic located in the Northeastern United States.”). Authors should also report details about any interventions, curriculum, qualifications and background information for research assistants, experimental design protocol(s), and any other procedural design issues that would be necessary for replication. In instances in which describing a treatment or conditions becomes exorbitant (e.g., step-by-step manualized therapy, programs, or interventions), researchers can include footnotes, appendices, and/or references to refer the reader to more information about the intervention protocol.

Missing Data

Procedures for handling missing values (incomplete survey responses) are important considerations in quantitative data analysis. Perhaps the most straightforward option for handling missing data is to simply delete missing responses. However, depending on the percentage of data that are missing and how the data are missing (e.g., missing completely at random, missing at random, or not missing at random), data imputation techniques can be employed to recover missing values (Cook, 2021; Myers, 2011). Quantitative researchers should provide a clear rationale behind their decisions around the deletion of missing values or when using a data imputation method. Readers are encouraged to review Cook’s (2021) commentary on procedures for handling missing data in quantitative research.

Measures

Counseling and other social science researchers oftentimes use instruments and screening tools to appraise latent traits, which can be defined as variables that are inferred rather than observed (AERA et al., 2014). The purpose of the Measures (aka Instrumentation) section is to operationalize the construct(s) of measurement (Heppner et al., 2016). Specifically, the Measures subsection of the Methods in a quantitative manuscript tends to include a presentation of (a) the instrument and construct(s) of measurement, (b) reliability and validity evidence of test scores, and (c) cross-cultural fairness and norming. The Measures section might also include a Materials subsection for studies that employed data-gathering techniques or equipment besides or in addition to instruments (Heppner et al., 2016); for instance, if a research study involved the use of a biofeedback device to collect data on changes in participants’ body functions.

Instrument and Construct of Measurement

Begin the Measures section by introducing the questionnaire or screening tool, its construct(s) of measurement, number of test items, example test items, and scale points. If applicable, the Measures section can also include information on scoring procedures and cutoff criterion; for example, total score benchmarks for low, medium, and high levels of the trait. Authors might also include commentary about how test scores will be operationalized to constitute the variables in the upcoming Data Analysis section.

Reliability and Validity Evidence of Test Scores

Reliability evidence involves the degree to which test scores are stable or consistent and validity evidence refers to the extent to which scores on a test succeed in measuring what the test was designed to measure (AERA et al., 2014; Bardhoshi & Erford, 2017). Researchers should report both reliability and validity evidence of scores for each instrument they use (Wester et al., 2013). A number of forms of reliability evidence exist (e.g., internal consistency, test-retest, interrater, and alternate/parallel/equivalent forms) and the AERA standards (2014) outline five forms of validity evidence. For the purposes of this article, I will focus on internal consistency reliability, as it is the most popular and most commonly misused reliability estimate in social sciences research (Kalkbrenner, 2021a; McNeish, 2018), as well as construct validity. The psychometric properties of a test (including reliability and validity evidence) are contingent upon the scores from which they were derived. As such, no test is inherently valid or reliable; test scores are only reliable and valid for a certain purpose, at a particular time, for use with a specific sample. Accordingly, authors should discuss reliability and validity evidence in terms of scores, for example, “Stamm (2010) found reliability and validity evidence of scores on the Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL 5) with a sample of . . . ”

Internal Consistency Reliability Evidence. Internal consistency estimates are derived from associations between the test items based on one administration (Kalkbrenner, 2021a). Cronbach’s coefficient alpha (α) is indisputably the most popular internal consistency reliability estimate in counseling and throughout social sciences research in general (Kalkbrenner, 2021a; McNeish, 2018). The appropriate use of coefficient alpha is reliant on the data meeting the following statistical assumptions: (a) essential tau equivalence, (b) continuous level scale of measurement, (c) normally distributed data, (d) uncorrelated error, (e) unidimensional scale, and (f) unit-weighted scaling (Kalkbrenner, 2021a). For decades, coefficient alpha has been passed down in the instructional practice of counselor training programs. Coefficient alpha has appeared as the dominant reliability index in national counseling and psychology journals without most authors computing and reporting the necessary statistical assumption checking (Kalkbrenner, 2021a; McNeish, 2018). The psychometrically daunting practice of using alpha without assumption checking poses a threat to the veracity of counseling research, as the accuracy of coefficient alpha is threatened if the data violate one or more of the required assumptions.

Internal Consistency Reliability Indices and Their Appropriate Use. Composite reliability (CR)

internal consistency estimates are derived in similar ways as coefficient alpha; however, the proper computation of CRs is not reliant on the data meeting many of alpha’s statistical assumptions (Kalkbrenner, 2021a; McNeish, 2018). For example, McDonald’s coefficient omega (ω or ωt) is a CR estimate that is not dependent on the data meeting most of alpha’s assumptions (Kalkbrenner, 2021a). In addition, omega hierarchical (ωh) and coefficient H are CR estimates that can be more advantageous than alpha. Despite the utility of CRs, their underuse in research practice is historically, in part, because of the complex nature of computation. However, recent versions of SPSS include a breakthrough point-and-click feature for computing coefficient omega as easily as coefficient alpha. Readers can refer to the SPSS user guide for steps to compute omega.

Guidelines for Reporting Internal Consistency Reliability. In the Measures subsection of the Methods section, researchers should report existing reliability evidence of scores for their instruments. This can be done briefly by reporting the results of multiple studies in the same sentence, as in: “A number of past investigators found internal consistency reliability evidence for scores on the [name of test] with a number of different samples, including college students (α =. XX, ω =. XX; Authors et al., 20XX), clients living with chronic back pain (α =. XX, ω =. XX; Authors et al., 20XX), and adults in the United States (α = . XX, ω =. XX; Authors et al., 20XX) . . .”

Researchers should also compute and report reliability estimates of test scores with their data set in the Measures section. If a researcher is using coefficient alpha, they have a duty to complete and report assumption checking to demonstrate that the properties of their sample data were suitable for alpha (Kalkbrenner, 2021a; McNeish, 2018). Another option is to compute a CR (e.g., ω or H) instead of alpha. However, Kalkbrenner (2021a) recommended that researchers report both coefficient alpha (because of its popularity) and coefficient omega (because of the robustness of the estimate). The proper interpretation of reliability estimates of test scores is done on a case-by-case basis, as the meaning of reliability coefficients is contingent upon the construct of measurement and the stakes or consequences of the results for test takers (Kalkbrenner, 2021a). The following tentative interpretative guidelines for adults’ scores on attitudinal measures were offered by Kalkbrenner (2021b) for coefficient alpha: α < .70 = poor, α > .70 to .84 = acceptable, α > .85 = strong; and for coefficient omega: ω < .65 = poor, ω > .65 to .80 = acceptable, ω > .80 = strong. It is important to note that these thresholds are for adults’ scores on attitudinal measures; acceptable internal consistency reliability estimates of scores should be much stronger for high-stakes testing.

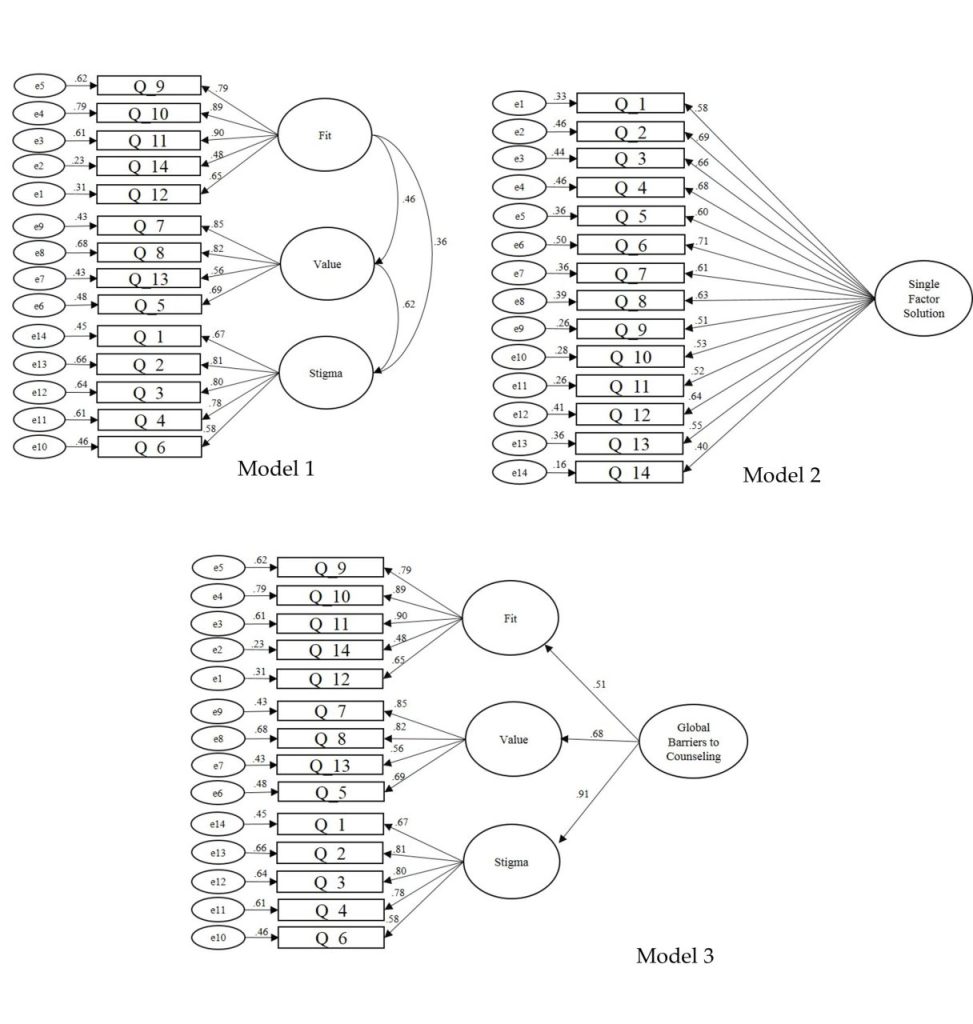

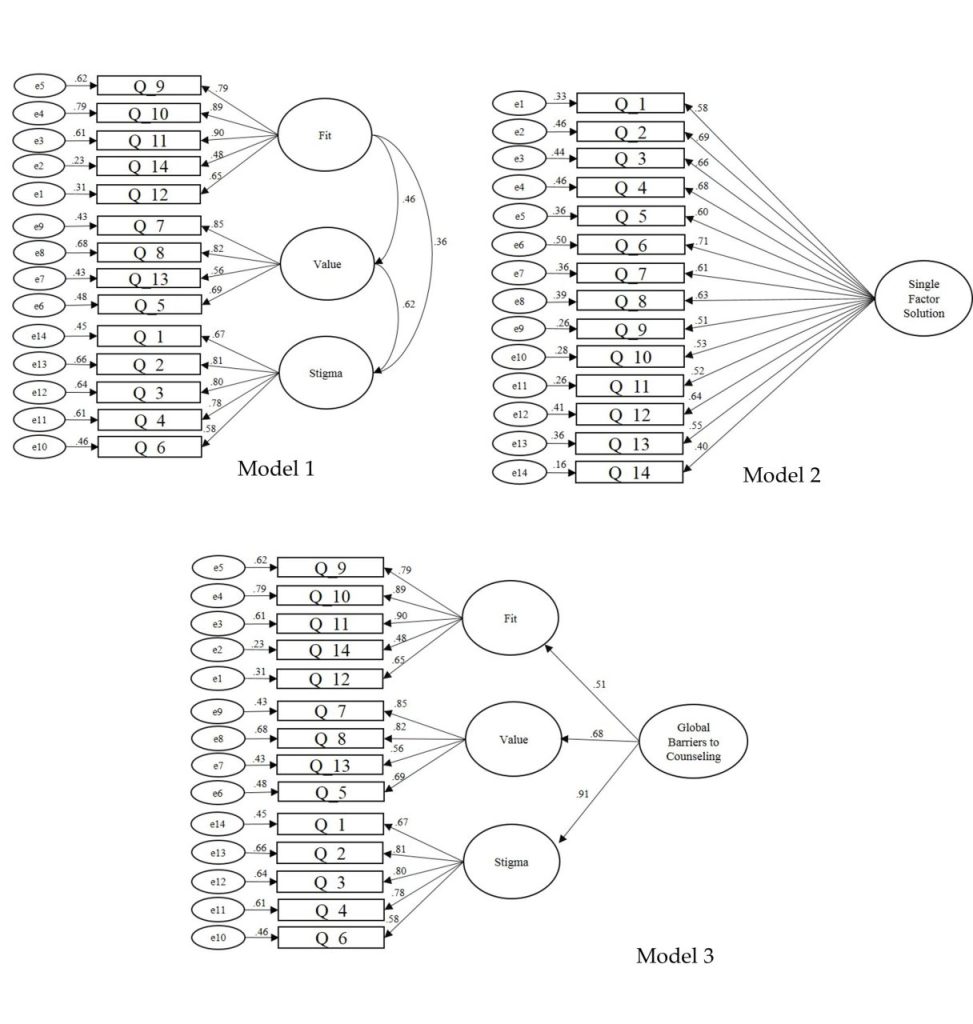

Construct Validity Evidence of Test Scores. Construct validity involves the test’s ability to accurately capture a theoretical or latent construct (AERA et al., 2014). Construct validity considerations are particularly important for counseling researchers who tend to investigate latent traits as outcome variables. At a minimum, counseling researchers should report construct validity evidence for both internal structure and relations with theoretically relevant constructs. Internal structure (aka factorial validity) is a source of construct validity that represents the degree to which “the relationships among test items and test components conform to the construct on which the proposed test score interpretations are based” (AERA et al., 2014, p. 16). Readers can refer to Kalkbrenner (2021b) for a free (open access publishing) overview of exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) that is written in layperson’s terms. Relations with theoretically relevant constructs (e.g., convergent and divergent validity) are another source of construct validity evidence that involves comparing scores on the test in question with scores on other reputable tests (AERA et al., 2014; Strauss & Smith, 2009).

Guidelines for Reporting Validity Evidence. Counseling researchers should report existing evidence of at least internal structure and relations with theoretically relevant constructs (e.g., convergent or divergent validity) for each instrument they use. EFA results alone are inadequate for demonstrating internal structure validity evidence of scores, as EFA is a much less rigorous test of internal structure than CFA (Kalkbrenner, 2021b). In addition, EFA results can reveal multiple retainable factor solutions, which need to be tested/confirmed via CFA before even initial internal structure validity evidence of scores can be established. Thus, both EFA and CFA are necessary for reporting/demonstrating initial evidence of internal structure of test scores. In an extension of internal structure, counselors should also report existing convergent and/or divergent validity of scores. High correlations (r > .50) demonstrate evidence of convergent validity and moderate-to-low correlations (r < .30, preferably r < .10) support divergent validity evidence of scores (Sink & Stroh, 2006; Swank & Mullen, 2017).

In an ideal situation, a researcher will have the resources to test and report the internal structure (e.g., compute CFA firsthand) of scores on the instrumentation with their sample. However, CFA requires large sample sizes (Kalkbrenner, 2021b), which oftentimes is not feasible. It might be more practical for researchers to test and report relations with theoretically relevant constructs, though adding one or more questionnaire(s) to data collection efforts can come with the cost of increasing respondent fatigue. In these instances, researchers might consider reporting other forms of validity evidence (e.g., evidence based on test content, criterion validity, or response processes; AERA et al., 2014). In instances when computing firsthand validity evidence of scores is not logistically viable, researchers should be transparent about this limitation and pay especially careful attention to presenting evidence for cross-cultural fairness and norming.

Cross-Cultural Fairness and Norming

In a psychometric context, fairness (sometimes referred to as cross-cultural fairness) is a fundamental validity issue and a complex construct to define (AERA et al., 2014; Kane, 2010; Neukrug & Fawcett, 2015). I offer the following composite definition of cross-cultural fairness for the purposes of a quantitative Measures section: the degree to which test construction, administration procedures, interpretations, and uses of results are equitable and represent an accurate depiction of a diverse group of test takers’ abilities, achievement, attitudes, perceptions, values, and/or experiences (AERA et al., 2014; Educational Testing Service [ETS], 2016; Kane, 2010; Kane & Bridgeman, 2017). Counseling researchers should consider the following central fairness issues when selecting or developing instrumentation: measurement bias, accessibility, universal design, equivalent meaning (invariance), test content, opportunity to learn, test adaptations, and comparability (AERA et al., 2014; Kane & Bridgeman, 2017). Providing a comprehensive overview of fairness is beyond the scope of this article; however, readers are encouraged to read Chapter 3 in the AERA standards (2014) on Fairness in Testing.

In the Measures section, counseling researchers should include commentary on how and in what ways cross-cultural fairness guided their selection, administration, and interpretation of procedures and test results (AERA et al., 2014; Kalkbrenner, 2021b). Cross-cultural fairness and construct validity are related constructs (AERA et al., 2014). Accordingly, citing construct validity of test scores (see the previous section) with normative samples similar to the researcher’s target population is one way to provide evidence of cross-cultural fairness. However, construct validity evidence alone might not be a sufficient indication of cross-cultural fairness, as the latent meaning of test scores are a function of test takers’ cultural context (Kalkbrenner, 2021b). To this end, when selecting instrumentation, researchers should review original psychometric studies and consider the normative sample(s) from which test scores were derived.

Commentary on the Danger of Using Self-Developed and Untested Scales

Counseling researchers have an ethical duty to “carefully consider the validity, reliability, psychometric limitations, and appropriateness of instruments when selecting assessments” (ACA, 2014, p. 11). Quantitative researchers might encounter instances in which a scale is not available to measure their desired construct of measurement (latent/inferred variable). In these cases, the first step in the line of research is oftentimes to conduct an instrument development and score validation study (AERA et al., 2014; Kalkbrenner, 2021b). Detailing the protocol for conducting psychometric research is outside the scope of this article; however, readers can refer to the MEASURE Approach to Instrument Development (Kalkbrenner, 2021c) for a free (open access publishing) overview of the steps in an instrument development and score validation study. Adapting an existing scale can be option in lieu of instrument development; however, according to the AERA standards (2014), “an index that is constructed by manipulating and combining test scores should be subjected to the same validity, reliability, and fairness investigations that are expected for the test scores that underlie the index” (p. 210). Although it is not necessary that all quantitative researchers become psychometricians and conduct full-fledged psychometric studies to validate scores on instrumentation, researchers do have a responsibility to report evidence of the reliability, validity, and cross-cultural fairness of test scores for each instrument they used. Without at least initial construct validity testing of scores (calibration), researchers cannot determine what, if anything at all, an untested instrument actually measures.

Data Analysis

Counseling researchers should report and explain the selection of their data analytic procedures (e.g., statistical analyses) in a Data Analysis (or Statistical Analysis) subsection of the Methods or Results section (Giordano et al., 2021; Leedy & Ormrod, 2019). The placement of the Data Analysis section in either the Methods or Results section can vary between publication outlets; however, this section tends to include commentary on variables, statistical models and analyses, and statistical assumption checking procedures.

Operationalizing Variables and Corresponding Statistical Analyses

Clearly outlining each variable is an important first step in selecting the most appropriate statistical analysis for answering each research question (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). Researchers should specify the independent variable(s) and corresponding levels as well as the dependent variable(s); for example, “The first independent variable, time, was composed of the three following levels: pre, middle, and post. The dependent variables were participants’ scores on the burnout and compassion satisfaction subscales of the ProQOL 5.” After articulating the variables, counseling researchers are tasked with identifying each variable’s scale of measurement (Creswell & Creswell, 2018; Field, 2018; Flinn & Kalkbrenner, 2021). Researchers can select the most appropriate statistical test(s) for answering their research question(s) based on the scale of measurement for each variable and referring to Table 8.3 on page 159 in Creswell and Creswell (2018), Figure 1 in Flinn and Kalkbrenner (2021), or the chart on page 1072 in Field (2018).

Assumption Checking

Statistical analyses used in quantitative research are derived based on a set of underlying assumptions (Field, 2018; Giordano et al., 2021). Accordingly, it is essential that quantitative researchers outline their protocol for testing their sample data for the appropriate statistical assumptions. Assumptions of common statistical tests in counseling research include normality, absence of outliers (multivariate and/or univariate), homogeneity of covariance, homogeneity of regression slopes, homoscedasticity, independence, linearity, and absence of multicollinearity (Flinn & Kalkbrenner, 2021; Giordano et al., 2021). Readers can refer to Figure 2 in Flinn and Kalkbrenner (2021) for an overview of statistical assumptions for the major statistical analyses in counseling research.

Exemplar Quantitative Methods Section

The following section includes an exemplar quantitative methods section based on a hypothetical example and a practice data set. Producers and consumers of quantitative research can refer to the following section as an example for writing their own Methods section or for evaluating the rigor of an existing Methods section. As stated previously, a well-written literature review and research question(s) are essential for grounding the study and Methods section (Flinn & Kalkbrenner, 2021). The final piece of a literature review section is typically the research question(s). Accordingly, the following research question guided the following exemplar Methods section: To what extent are there differences in anxiety severity between college students who participate in deep breathing exercises with progressive muscle relaxation, group exercise program, or both group exercise and deep breathing with progressive muscle relaxation?

——-Exemplar——-

Methods

A quantitative group comparison research design was employed based on a post-positivist philosophy of science (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). Specifically, I implemented a quasi-experimental, control group pretest/posttest design to answer the research question (Leedy & Ormrod, 2019). Consistent with a post-positivist philosophy of science, I reflected on pursuing a probabilistic objective answer that is situated within the context of imperfect and fallible evidence. The rationale for the present study was grounded in Dr. David Servan-Schreiber’s (2009) theory of lifestyle practices for integrated mental and physical health. According to Servan-Schreiber, simultaneously focusing on improving one’s mental and physical health is more effective than focusing on either physical health or mental wellness in isolation. Consistent with Servan-Schreiber’s theory, the aim of the present study was to compare the utility of three different approaches for anxiety reduction: a behavioral approach alone, a physiological approach alone, and a combined behavioral approach and physiological approach.

I am in my late 30s and identify as a White man. I have a PhD in counselor education as well as an MS in clinical mental health counseling. I have a deep belief in and an active line of research on the utility of total wellness (combined mental and physical health). My research and clinical experience have informed my passion and interest in studying the utility of integrated physical and psychological health services. More specifically, my personal beliefs, values, and interest in total wellness influenced my decision to conduct the present study. I carefully followed the procedures outlined below to reduce the chances that my personal values biased the research design.

Participants and Procedures

Data collection began following approval from the IRB. Data were collected during the fall 2022 semester from undergraduate students who were at least 18 years or older and enrolled in at least one class at a land grant, research-intensive university located in the Southwestern United States. An a priori statistical power analysis was computed using G*Power (Faul et al., 2009). Results revealed that a sample size of at least 42 would provide an 80% power estimate, α = .05, with a moderate effect size, f = 0.25.

I obtained an email list from the registrar’s office of all students enrolled in a section of a Career Excellence course, which was selected to recruit students in a variety of academic majors because all undergraduate students in the College of Education are required to take this course. The focus of this study (mental and physical wellness) was also consistent with the purpose of the course (success in college). A non-probability, convenience sampling procedure was employed by sending a recruitment message to students’ email addresses via the Qualtrics online survey platform. The response rate was approximately 15%, with a total of 222 prospective participants indicating their interest in the study by clicking on the electronic recruitment link, which automatically sent them an invitation to attend an information session about the study. One hundred forty-four students showed up for the information session, 129 of which provided their voluntary informed consent to enroll in the study. Participants were given a confidential identification number to track their pretest/posttest responses, and then they completed the pretest (see the Measures section below). Respondents were randomly assigned in equal groups to either (a) deep breathing with progressive muscle relaxation condition, (b) group exercise condition, or (c) both exercise and deep breathing with progressive muscle relaxation condition.

A missing values analysis showed that less than 5% of data was missing for all cases. Expectation maximization was used to impute missing values, as Little’s Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) test revealed that the data could be treated as MCAR (p = .367). Data from five participants who did not return to complete the posttest at the end of the semester were removed, yielding a robust sample of N = 124. Participants (N = 124) ranged in age from 18 to 33 (M = 21.64, SD = 3.70). In terms of gender identity, 65.0% (n = 80) self-identified as female, 32.2% (n = 40) as male, 0.8% (n = 1) as transgender, and 2.4% (n = 3) did not specify their gender identity. For ethnic identity, 50.0% (n = 62) identified as White, 26.7% (n = 33) as Latinx, 12.1% (n = 15) as Asian, 9.6% (n = 12) as Black, 0.8% (n = 1) as Alaskan Native, and 0.8% (n = 1) did not specify their ethnic identity. In terms of generational status, 36.3% (n = 45) of participants were first-generation college students and 63.7% (n = 79) were second-generation or beyond.

Group Exercise and Deep Breathing Programs

I was awarded a small grant to offer on-campus deep breathing with progressive muscle relaxation and group exercise programs. The structure of the group exercise program was based on Patterson et al. (2021), which consisted of more than 50 available exercise classes each week (e.g., cycling, yoga, swimming, dance). There was no limit to the number of classes that participants could attend; however, attending at least one class each week was required for participation in the study. Readers can refer to Patterson et al. for more information about the group exercise programming.

Neeru et al.’s (2015) deep breathing and progressive muscle relaxation programming was used in the present study. Participants completed daily deep breathing and Jacobson Progressive Muscle Relaxation (JPMR). JPMR was selected because of its documented success with treating anxiety disorders (Neeru et al., 2015). Specifically, the program consisted of four deep breathing steps completed five times and JPMR for approximately 25 minutes daily. Participants attended a weekly deep breathing and JPMR session facilitated by a licensed professional counselor. Participants also practiced deep breathing and JPMR on their own daily and kept a log to document their practice sessions. Readers can refer to Neeru et al. for more information about JPMR and the deep breathing exercises.

Measures

Prospective participants read an informed consent statement and indicated their voluntary informed consent by clicking on a checkbox. Next, participants confirmed that they met the following inclusion criteria: (a) at least 18 years old and (b) currently enrolled in at least one undergraduate college class. The instrumentation began with demographic items regarding participants’ gender identity, ethnic identity, age, and confidential identification number to track their pretest and posttest scores. Lastly, participants completed a convergent validity measure (Mental Health Inventory – 5) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)-7 to measure the outcome variable (anxiety severity).

Reliability and Validity Evidence of Test Scores

Tests of internal consistency were computed to test the reliability of scores on the screening tool for appraising anxiety severity with undergraduate students in the present sample. For internal consistency reliability of scores, coefficient alpha (α) and coefficient omega (ω) were computed with the following minimum thresholds for adults’ scores on attitudinal measures: α > .70 and ω > .65, based on the recommendations of Kalkbrenner (2021b).

The Mental Health Inventory–5. Participants completed the Mental Health Inventory (MHI)-5 to test the convergent validity of undergraduate students in the present samples’ scores on the GAD-7, which was used to measure the outcome variable in this study, anxiety severity. The MHI-5 is a 5-item measure for appraising overall mental health (Berwick et al., 1991). Higher MHI-5 scores reflect better mental health. Participants responded to test items (example: “How much of the time, during the past month, have you been a very nervous person?”) on the following Likert-type scale: 0 = none of the time, 1 = a little of the time, 2 = some of the time, 3 = a good bit of the time, 4 = most of the time, or 5 = all of the time. The MHI-5 has particular utility as a convergent validity measure because of its brief nature (5 items) coupled with the myriad of support for its psychometric properties (e.g., Berwick et al., 1991; Rivera-Riquelme et al., 2019; Thorsen et al., 2013). As just a few examples, Rivera-Riquelme et al. (2019) found acceptable internal consistency reliability evidence (α = .71, ω = .78) and internal structure validity evidence of MHI-5 scores. In addition, the findings of Thorsen et al. (2013) demonstrated convergent validity evidence of MHI-5 scores. Findings in the extant literature (e.g., Foster et al., 2016; Vijayan & Joseph, 2015) established an inverse relationship between anxiety and mental health. Thus, a strong negative correlation (r > −.50; Sink & Stroh, 2006) between the MHI-5 and GAD-7 would support convergent validity evidence of scores.

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder–7. The GAD-7 is a 7-item screening tool for appraising anxiety severity (Spitzer et al., 2006). Participants respond to test items based on the following prompt: “Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by the following problems?” and anchor definitions: 0 = not at all, 1 = several days, 2 = more than half the days, or 3 = nearly every day (Spitzer et al., 2006, p. 1739). Sample test items include “being so restless that it’s hard to sit still” and “feeling afraid as if something awful might happen.” The GAD-7 items can be summed into an interval-level composite score, with higher scores indicating greater levels of Anxiety Severity. GAD-7 scores can range from 0 to 21 and are classified as mild (0–5), moderate (6–10), moderately severe (11–15), or severe (16–21).

In the initial score validation study, Spitzer et al. (2006) found evidence for internal consistency (α = .92) and test-retest reliability (intraclass correlation = .83) of GAD-7 scores among adults in the United States who were receiving services in primary care clinics. In more recent years, a number of additional investigators found internal consistency reliability evidence for GAD-7 scores, including samples of undergraduate college students in the southern United States (α = .91; Sriken et al., 2022), Black and Latinx adults in the United States (α = .93, ω = .93; Kalkbrenner, 2022), and English-speaking college students living in Ethiopia (ω = .77; Manzar et al., 2021). Similarly, the data set in the present study displayed acceptable internal consistency reliability evidence for GAD-7 scores (α = .82, ω = .81).

Spitzer et al. (2006) used factor analysis to establish internal structure validity, correlations with established screening tools for convergent validity, and criterion validity evidence by demonstrating the capacity of GAD-7 scores for detecting likely cases of generalized anxiety disorder. A number of subsequent investigators found internal structure validity evidence of GAD-7 scores via CFA and multiple-group CFA (Kalkbrenner, 2022; Sriken et al., 2022). In addition, the findings of Sriken et al. (2022) supported both the convergent and divergent validity of GAD-7 scores with other established tests. The data set in the present study (N = 124) was not large enough for internal structure validity testing. However, a strong negative correlation (r = −.78) between the GAD-7 and MHI-5 revealed convergent validity evidence of GAD-7 scores with the present sample of undergraduate students.

In terms of norming and cross-cultural fairness, there were qualitative differences between the normative GAD-7 sample in the original score validation study (adults in the United States receiving services in primary care clinics) and the non-clinical sample of young adult college students in the present study. However, the demographic profile of the present sample is consistent with Sriken et al. (2022), who validated GAD-7 scores with a large sample (N = 414) of undergraduate college students. For example, the demographic profile of the sample in the current study for gender identity closely resembled the composition of Sriken et al.’s sample, which included 66.7% women, 33.1% men, and 0.2% transgender individuals. In terms of ethnic identity, the demographic profile of the present sample was consistent with Sriken et al. for White and Black participants, although the present sample reflected a somewhat smaller proportion of Asian students (19.6%) and a greater proportion of Latinx students (5.3%).

Data Analysis and Assumption Checking

The present study included two categorical-level independent variables and one continuous-level dependent variable. The first independent variable, program, consisted of three levels: (a) deep breathing with progressive muscle relaxation, (b) group exercise, or (c) both exercise and deep breathing with progressive muscle relaxation. The second independent variable, time, consisted of two levels: the beginning of the semester and the end of the semester. The dependent variable was participants’ interval-level score on the GAD-7. Accordingly, a 3 (program) X 2 (time) mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA) was the most appropriate statistical test for answering the research question (Field, 2018).

The data were examined for the following statistical assumptions for a mixed-design ANOVA: absence of outliers, normality, homogeneity of variance, and sphericity of the covariance matrix based on the recommendations of Field (2018). Standardized z-scores revealed an absence of univariate outliers (z > 3.29). A review of skewness and kurtosis values were highly consistent with a normal distribution, with the majority of values less than ± 1.0. The results of a Levene’s test demonstrated that the data met the assumption of homogeneity of variance, F(2, 121) = 0.73, p = .486. Testing the data for sphericity was not applicable in this case, as the within-subjects IV (time) only comprised two levels.

——-End Exemplar——-

Conclusion

The current article is a primer on guidelines, best practices, and recommendations for writing or evaluating the rigor of the Methods section of quantitative studies. Although the major elements of the Methods section summarized in this manuscript tend to be similar across the national peer-reviewed counseling journals, differences can exist between journals based on the content of the article and the editorial board members’ preferences. Accordingly, it can be advantageous for prospective authors to review recently published manuscripts in their target journal(s) to look for any similarities in the structure of the Methods (and other sections). For instance, in one journal, participants and procedures might be reported in a single subsection, whereas in other journals they might be reported separately. In addition, most journals post a list of guidelines for prospective authors on their websites, which can include instructions for writing the Methods section. The Methods section might be the most important section in a quantitative study, as in all likelihood methodological flaws cannot be resolved once data collection is complete, and serious methodological flaws will compromise the integrity of the entire study, rendering it unpublishable. It is also essential that consumers of quantitative research can proficiently evaluate the quality of a Methods section, as poor methods can make the results meaningless. Accordingly, the significance of carefully planning, executing, and writing a quantitative research Methods section cannot be understated.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

American Counseling Association. (2014). ACA code of ethics.

American Psychological Association. (2020). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association: The official guide to APA style (7th ed.).

American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, & National Council on Measurement in Education. (2014). The standards for educational and psychological testing.

https://www.aera.net/Publications/Books/Standards-for-Educational-Psychological-Testing-2014-Edition

Balkin, R. S., & Sheperis, C. J. (2011). Evaluating and reporting statistical power in counseling research. Journal of Counseling & Development, 89(3), 268–272. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2011.tb00088.x

Bardhoshi, G., & Erford, B. T. (2017). Processes and procedures for estimating score reliability and precision. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 50(4), 256–263.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2017.1388680

Berwick, D. M., Murphy, J. M., Goldman, P. A., Ware, J. E., Jr., Barsky, A. J., & Weinstein, M. C. (1991). Performance of a five-item mental health screening test. Medical Care, 29(2), 169–176.

https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199102000-00008

Cook, R. M. (2021). Addressing missing data in quantitative counseling research. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 12(1), 43–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/21501378.2019.171103

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). SAGE.

Educational Testing Service. (2016). ETS international principles for fairness review of assessments: A manual for developing locally appropriate fairness review guidelines for various countries. https://www.ets.org/content/dam/ets-org/pdfs/about/fairness-review-international.pdf

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160.

https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

Field, A. (2018). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS Statistics (5th ed.). SAGE.

Flinn, R. E., & Kalkbrenner, M. T. (2021). Matching variables with the appropriate statistical tests in counseling research. Teaching and Supervision in Counseling, 3(3), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.7290/tsc030304

Foster, T., Steen, L., O’Ryan, L., & Nelson, J. (2016). Examining how the Adlerian life tasks predict anxiety in first-year counseling students. The Journal of Individual Psychology, 72(2), 104–120. https://doi.org/10.1353/jip.2016.0009

Giordano, A. L., Schmit, M. K., & Schmit, E. L. (2021). Best practice guidelines for publishing rigorous research in counseling. Journal of Counseling & Development, 99(2), 123–133. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12360

Hays, D. G., & Singh, A. A. (2012). Qualitative inquiry in clinical and educational settings. Guilford.

Heppner, P. P., Wampold, B. E., Owen, J., Wang, K. T., & Thompson, M. N. (2016). Research design in counseling (4th ed.). Cengage.

Kalkbrenner, M. T. (2021a). Alpha, omega, and H internal consistency reliability estimates: Reviewing these options and when to use them. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation.

https://doi.org/10.1080/21501378.2021.1940118

Kalkbrenner, M. T. (2021b). Enhancing assessment literacy in professional counseling: A practical overview of factor analysis. The Professional Counselor, 11(3), 267–284. https://doi.org/10.15241/mtk.11.3.267

Kalkbrenner, M. T. (2021c). A practical guide to instrument development and score validation in the social sciences: The MEASURE Approach. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 26(1), Article 1.

https://doi.org/10.7275/svg4-e671

Kalkbrenner, M. T. (2022). Validation of scores on the Lifestyle Practices and Health Consciousness Inventory with Black and Latinx adults in the United States: A three-dimensional model. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 55(2), 84–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2021.1955214

Kane, M. (2010). Validity and fairness. Language Testing, 27(2), 177–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532209349467

Kane, M., & Bridgeman, B. (2017). Research on validity theory and practice at ETS. In R. E. Bennett & M. von Davier (Eds.), Advancing human assessment: The methodological, psychological and policy contributions of ETS (pp. 489–552). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58689-2_16

Korn, J. H., & Bram, D. R. (1988). What is missing in the Method section of APA journal articles? American Psychologist, 43(12), 1091–1092. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.43.12.1091

Leedy, P. D., & Ormrod, J. E. (2019). Practical research: Planning and design (12th ed.). Pearson.

Lutz, W., & Hill, C. E. (2009). Quantitative and qualitative methods for psychotherapy research: Introduction to special section. Psychotherapy Research, 19(4–5), 369–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300902948053

Manzar, M. D., Alghadir, A. H., Anwer, S., Alqahtani, M., Salahuddin, M., Addo, H. A., Jifar, W. W., & Alasmee, N. A. (2021). Psychometric properties of the General Anxiety Disorders-7 Scale using categorical data methods: A study in a sample of university attending Ethiopian young adults. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 17(1), 893–903. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S295912

McNeish, D. (2018). Thanks coefficient alpha, we’ll take it from here. Psychological Methods, 23(3), 412–433. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000144

Myers, T. A. (2011). Goodbye, listwise deletion: Presenting hot deck imputation as an easy and effective tool for handling missing data. Communication Methods and Measures, 5(4), 297–310.

https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2011.624490

Neeru, Khakha, D. C., Satapathy, S., & Dey, A. B. (2015). Impact of Jacobson Progressive Muscle Relaxation (JPMR) and deep breathing exercises on anxiety, psychological distress and quality of sleep of hospitalized older adults. Journal of Psychosocial Research, 10(2), 211–223.

Neukrug, E. S., & Fawcett, R. C. (2015). Essentials of testing and assessment: A practical guide for counselors, social workers, and psychologists (3rd ed.). Cengage.

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Leech, N. L. (2005). On becoming a pragmatic researcher: The importance of combining quantitative and qualitative research methodologies. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(5), 375–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645570500402447

Patterson, M. S., Gagnon, L. R., Vukelich, A., Brown, S. E., Nelon, J. L., & Prochnow, T. (2021). Social networks, group exercise, and anxiety among college students. Journal of American College Health, 69(4), 361–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2019.1679150

Rivera-Riquelme, M., Piqueras, J. A., & Cuijpers, P. (2019). The Revised Mental Health Inventory-5 (MHI-5) as an ultra-brief screening measure of bidimensional mental health in children and adolescents. Psychiatry Research, 247(1), 247–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.02.045

Rovai, A. P., Baker, J. D., & Ponton, M. K. (2013). Social science research design and statistics: A practitioner’s guide to research methods and SPSS analysis. Watertree Press.

Servan-Schreiber, D. (2009). Anticancer: A new way of life (3rd ed.). Viking Publishing.

Sink, C. A., & Mvududu, N. H. (2010). Statistical power, sampling, and effect sizes: Three keys to research relevancy. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 1(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150137810373613

Sink, C. A., & Stroh, H. R. (2006). Practical significance: The use of effect sizes in school counseling research. Professional School Counseling, 9(5), 401–411. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X0500900406

Smagorinsky, P. (2008). The method section as conceptual epicenter in constructing social science research reports. Written Communication, 25(3), 389–411. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088308317815

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097.

https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

Sriken, J., Johnsen, S. T., Smith, H., Sherman, M. F., & Erford, B. T. (2022). Testing the factorial validity and measurement invariance of college student scores on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) Scale across gender and race. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 55(1), 1–16.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2021.1902239

Stamm, B. H. (2010). The Concise ProQOL Manual (2nd ed.). bit.ly/StammProQOL

Strauss, M. E., & Smith, G. T. (2009). Construct validity: Advances in theory and methodology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 5, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153639

Swank, J. M., & Mullen, P. R. (2017). Evaluating evidence for conceptually related constructs using bivariate correlations. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 50(4), 270–274.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2017.1339562

Thorsen, S. V., Rugulies, R., Hjarsbech, P. U., & Bjorner, J. B. (2013). The predictive value of mental health for long-term sickness absence: The Major Depression Inventory (MDI) and the Mental Health Inventory (MHI-5) compared. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), Article 115. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-115

Vijayan, P., & Joseph, M. I. (2015). Wellness and social interaction anxiety among adolescents. Indian Journal of Health and Wellbeing, 6(6), 637–639.

Wester, K. L., Borders, L. D., Boul, S., & Horton, E. (2013). Research quality: Critique of quantitative articles in the Journal of Counseling & Development. Journal of Counseling & Development, 91(3), 280–290.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2013.00096.x

Appendix

Outline and Brief Overview of a Quantitative Methods Section

Methods

- Research design (e.g., group comparison [experimental, quasi-experimental, ex-post-facto], correlational/predictive) and conceptual framework

- Researcher bias and reflexivity statement

Participants and Procedures

- Recruitment procedures for data collection in enough detail for replication

- Research ethics including but not limited to receiving institutional review board (IRB) approval

- Sampling procedure: Researcher access to prospective participants, recruitment procedures, and data collection modality (e.g., online survey)

- Sampling technique: Probability sampling (e.g., simple random sampling, systematic random sampling, stratified random sampling, cluster sampling) or non-probability sampling (e.g., volunteer sampling, convenience sampling, purposive sampling, quota sampling, snowball sampling, matched sampling)

- A priori statistical power analysis

- Sampling frame, response rate, raw sample, missing data, and the size of the final useable sample

- Demographic breakdown for participants

- Timeframe, setting, and location where data were collected

Measures

- Introduction of the instrument and construct(s) of measurement (include sample test items)

- Reliability and validity evidence of test scores (for each instrument):

- Existing reliability (e.g., internal consistency [coefficient alpha, coefficient omega, or coefficient H], test/retest) and validity (e.g., internal structure, convergent/divergent, criterion) evidence of scores

- *Note: At a minimum, internal structure validity evidence of scores should include both exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

- Reliability and validity evidence of test scores with the data set in the present study

- *Note: Only using coefficient alpha without completing statistical assumption checking is insufficient. Compute both coefficient omega and alpha or alpha with proper assumption checking.

- Cross-cultural fairness and norming: Commentary on how and in what ways cross-cultural fairness guided the selection, administration, and interpretation of procedures and test results

- Review and citations of original psychometric studies and normative samples

Data Analysis

- Operationalized variables and scales of measurement

- Procedures for matching variables with appropriate statistical analyses

- Assumption checking procedures

Note. This appendix is a brief summary and not a substitute for the narrative in the text of this article.

Michael T. Kalkbrenner, PhD, NCC, is an associate professor at New Mexico State University. Correspondence may be addressed to Michael T. Kalkbrenner, 1780 E. University Ave., Las Cruces, NM 88003, mkalk001@nmsu.edu.

Nov 9, 2022 | Volume 12 - Issue 3

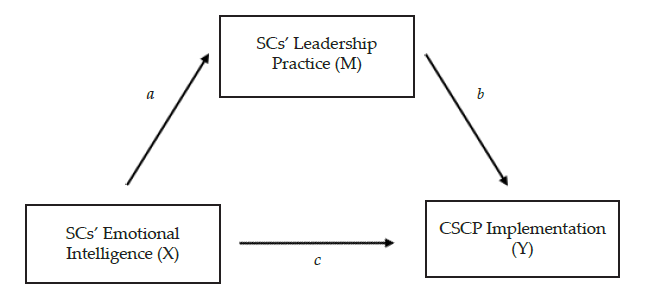

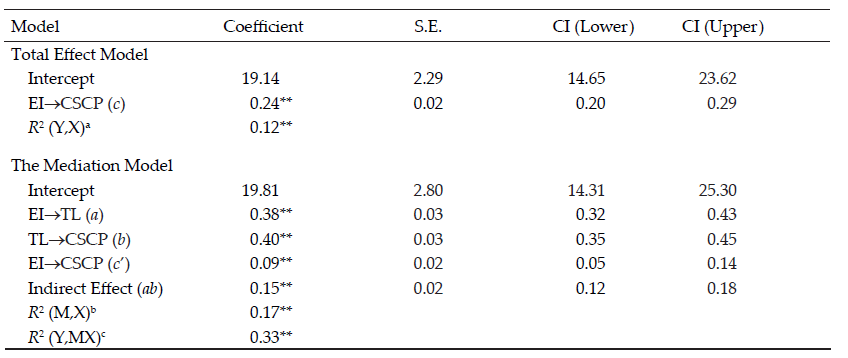

Derron Hilts, Yanhong Liu, Melissa Luke

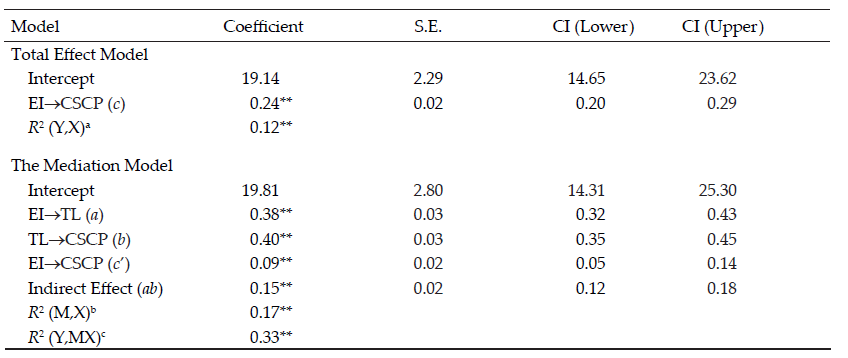

The authors examined whether school counselors’ emotional intelligence predicted their comprehensive school counseling program (CSCP) implementation and whether engagement in transformational leadership practices mediated the relationship between emotional intelligence and CSCP implementation. The sample for the study consisted of 792 school counselors nationwide. The findings demonstrated the significant mediating role of transformational leadership on the relationship between emotional intelligence and CSCP implementation. Implications for the counseling profession are discussed.

Keywords: emotional intelligence, school counselors, transformational leadership, comprehensive school counseling program, implementation

School counselors have been called upon to design and implement culturally responsive comprehensive school counseling programs (CSCPs) that have a deliberate and systemic focus on facilitating optimal student outcomes and development (American School Counselor Association [ASCA], 2017, 2019b). To this end, school counselors are expected to align their activities with the ASCA National Model (ASCA, 2019b) with an aim toward facilitating students’ knowledge, attitudes, skills, and behaviors to be academically and socially/emotionally successful and preparing students for college and career (ASCA, 2021). Relatedly, ASCA (2019a) urges school counselors to apply and enact a model of leadership in the process of program implementation. Several studies (e.g., Mason, 2010; Mullen et al., 2019; Shillingford & Lambie, 2010) have provided empirical evidence that supports the predictive role of school counselors’ leadership on their program implementation outcomes. Still, little is known about the relationship between school counselors’ program implementation and their leadership practices grounded in a specific model such as transformational leadership (Bolman & Deal, 1997; Kouzes & Posner, 1995). Understanding this relationship may allow school counselors to better align their practices within a specific leadership framework consistent with best practice (ASCA, 2019a).

Although leadership has been broadly established as a macro-level capability, emotional intelligence has started to gain interest in recent literature, as intra- and interpersonal competencies are central to school counselors’ practice (Hilts et al., 2019; Hilts, Liu, et al., 2022; Mullen et al., 2018). For instance, school counselors must be emotionally attuned to themselves and others to more effectively navigate the complexities of systems in which they operate (Mullen et al., 2018). One way to achieve such emotional attunement may be by respecting and validating others’ perspectives and providing emotional support to enact interpersonal influence aimed at facilitating educational partners’ keenness toward programmatic efforts (Hilts et al., 2019; Hilts, Liu, et al., 2022; Jordan & Lawrence, 2009). The purpose of the current study is to examine the mechanisms between school counselors’ emotional intelligence, transformational leadership, and CSCP implementation.

Comprehensive School Counseling Programs

Although school counseling programs will vary in structure based on the unique needs of school and community partners (Mason, 2010), programs should be comprehensive in scope, preventative by design, and developmental in nature (ASCA, 2017). CSCP implementation, which comprises a core component of school counseling practice, involves multilevel services (e.g., instruction, consultation, collaboration) and assessments (e.g., program assessments, annual results reports). The functioning of these services and assessments is further defined and managed within the broader school community by the CSCP (Duquette, 2021). Moreover, CSCPs are generally aligned with the ASCA National Model (ASCA, 2019b) to create a shared vision among school counselors to have a more deliberate and systemic focus on facilitating optimal student outcomes and development.

Over the past 20 years, researchers have consistently found positive relationships between CSCP implementation and student achievement reflected through course grades and graduation/retention rates (Sink et al., 2008) and achievement-related outcomes such as behavioral issues and attendance (Akos et al., 2019). Students who attend schools with more well established and fully implemented CSCPs are more likely to perform well academically and behaviorally (Akos et al., 2019). Additionally, researchers have found that school counselors who engage in multilevel services associated with a CSCP are more likely to have higher levels of wellness functioning compared to those who are less engaged in delivering these services (Randick et al., 2018). As such, CSCP implementation seems to not only be positively related to student development and achievement but also the overall well-being of school counselors.

Designing and implementing a culturally responsive CSCP demands a collaborative effort between both school counselors and educational partners to create and sustain an environment that is responsive to students’ diverse needs (ASCA, 2017). This ongoing and iterative process requires school counselors to be emotionally attuned with school, family, and community partners to co-construct, facilitate, and lead initiatives to more efficaciously implement equitable services within their programs (ASCA, 2019b; Bryan et al., 2017). School counselors must engage in leadership and be attentive toward their self- and other-awareness and management to traverse diverse contexts involving differences in personalities, values and goals, and ideologies (Mullen et al., 2018). Although researchers have reported that school counselors’ CSCP implementation is positively related to their leadership (e.g., Mason, 2010), no studies have investigated the relationship between emotional intelligence and CSCP implementation.

Emotional Intelligence

Emotional intelligence generally refers to the ability to recognize, comprehend, and manage the emotions of oneself and others to accomplish individual and shared goals (Kim & Kim, 2017). Scholars have purported that emotional intelligence can be subsumed into two overarching forms: trait emotional intelligence and ability emotional intelligence (Petrides & Furnham, 2000a, 2000b, 2001). Trait emotional intelligence, also known as trait emotional self-efficacy, involves “a constellation of behavioral dispositions and self-perceptions concerning one’s ability to recognize, process, and utilize emotional-laden information” (Petrides et al., 2004, p. 278). Ability emotional intelligence, also referred to as cognitive-emotional ability, concerns an individual’s emotion-related cognitive abilities (Petrides & Furnham, 2000b). Said differently, trait emotional intelligence is in the realm of an individual’s personality (e.g., social awareness), whereas ability emotional intelligence denotes an individual’s actual capabilities to perceive, understand, and respond to emotionally charged situations.

Over the past two decades, scholars have expanded the scope of emotional intelligence to have a deliberate focus on how emotional intelligence occurs within teams or groups in the workforce context (Jordan et al., 2002; Jordan & Lawrence, 2009). Given the salience of emotions in various professional and work contexts (e.g., Jordan & Troth, 2004), Jordan and colleagues’ (2002) Workgroup Emotional Intelligence Profile (WEIP) facilitates a better understanding of how emotional intelligence manifests in teams. The WEIP centralizes emotional intelligence around the “understanding of emotional processes” (Jordan et al., 2002, p. 197). Using the WEIP, researchers revealed that higher emotional intelligence scores are positively related to job satisfaction, organizational citizenship (e.g., performing competently under pressure), organizational commitment, and school and work performance (Miao et al., 2017a, 2017b; Van Rooy & Viswesvaran, 2004). Conversely, higher scores of emotional intelligence were negatively associated with turnover intentions and counterproductive behavior (Miao et al., 2017a, 2017b).

Emotional intelligence has also gained increased attention in the counseling literature. For example, Easton et al. (2008) found emotional intelligence as a significant predictor of counseling self-efficacy in the areas of attending to the counseling process and dealing with difficult client behavior. Following a two-phase investigation, Easton and colleagues demonstrated the stability of emotional intelligence during a 9-month timeframe in both groups of professional counselors and counselors-in-training; thus, the researchers argued that emotional intelligence may be an inherent characteristic associated with the career choice of counseling. In an earlier study with a sample with 108 school counselors, emotional intelligence was found to be significantly and uniquely related to school counselors’ multicultural counseling competence (Constantine & Gainor, 2001). More recently, school counselors’ emotional intelligence was found to be positively related to leadership self-efficacy and experience (Mullen et al., 2018).

School Counseling Leadership Practice

Leadership practice is a dynamic, interpersonal phenomenon within which school counselors engage in behaviors that mobilize support from educational partners to achieve programmatic and organizational objectives aimed at promoting student achievement and development (Hilts, Peters, et al., 2022). The focus on leadership practice entails an emphasis on the actual behavior of the individual, which scholars have contended is a byproduct of both individual and contextual factors in which these behaviors occur (Hilts, Liu, et al., 2022; Mischel & Shoda, 1998; Scarborough & Luke, 2008). For instance, school counselors’ support from other school partners (Dollarhide et al., 2008; Robinson et al., 2019) and previous leadership experience (Hilts, Liu, et al., 2022; Lowe et al., 2017) have been found to influence school counselors’ engagement in leadership. Hilts, Liu, and colleagues (2022) found that intra- and interpersonal factors significantly predicted school counselors’ engagement in leadership such as multicultural competence, leadership self-efficacy, and psychological empowerment. Across several models of leadership (e.g., Bolman & Deal, 1997; Kouzes & Posner, 1995), transformational leadership has been situated in the context of school counseling (Gibson et al., 2018).

Transformational School Counseling Leadership

Transformational leadership is described as behaviors aimed at encouraging others to enact leadership, challenge the status quo, and actively pursue learning and development to achieve higher performance (Bolman & Deal, 1997; Kouzes & Posner, 1995). Individuals employing transformational leadership foster a climate of trust and respect and inspire motivation among others by facilitating emotional attachments and commitment to others and the organization’s mission. More recently, Gibson et al. (2018) constructed and validated the School Counseling Transformational Leadership Inventory (SCTLI) in an effort to support school counselors in conceptualizing and informing their approach to leadership. The SCTLI (Gibson et al., 2018)—grounded in the ASCA National Model (ASCA, 2012) and the general transformational leadership literature (e.g., Avolio et al., 1991)—offers a framework to support engagement in leadership within a school context. For example, school counselors build partnerships with important decision-makers in the school and community and empower educational partners to act to improve the program and the school. School counselors engaging in transformational leadership ascribe to an egalitarian structure in which they engage in shared decision-making, promote a united vision, and inspire others to work toward positive change among students and the broader school community (Lowe et al., 2017). Beyond being studied as an outcome variable itself (Hilts, Liu, et al., 2022), school counselors’ enactment of leadership has also been found to be positively associated with their outcomes of CSCP implementation (Mason, 2010; Mullen et al., 2019).

Emotional Intelligence and the Mediating Role of Transformational Leadership

Over the past several decades, emotional intelligence has been increasingly attributed as a critical trait and ability of individuals employing effective leadership (Kim & Kim, 2017). For instance, Gray (2009) asserted that effective school leaders are able to perceive, understand, and monitor their own and others’ internal states and use this information to guide the thinking and actions of themselves and others. Mullen and colleagues (2018) found that, among a sample of 389 school counselors, domains of emotional intelligence (Jordan & Lawrence, 2009) were significant predictors of leadership self-efficacy and leadership experience. Specifically, Mullen et al.’s (2018) results showed that (a) awareness of own emotions and management of own and others’ emotions were positively related to leadership self-efficacy; (b) management of own and others’ emotions significantly predicted leadership experience; and (c) awareness and management of others’ emotions was positively associated with self-leadership.

Moreover, initial research has revealed that not only is emotional intelligence an antecedent of leadership (Barbuto et al., 2014; Harms & Credé, 2010; Mullen et al., 2018), but that leadership, particularly transformational leadership, mediates the relationship between emotional intelligence and job-related behavior such as job performance (Hur et al., 2011; Hussein & Yesiltas, 2020; Rahman & Ferdausy, 2014). For example, Hussein and Yesiltas’s (2020) results indicated that not only were higher scores of emotional intelligence positively associated with organizational commitment, but that transformational leadership partially mediated the relationship between emotional intelligence and organizational commitment. In another study, Hur and colleagues (2011) sought to examine whether transformational leadership mediated the link between emotional intelligence and multiple outcomes among 859 public employees across 55 teams. The researchers’ results showed that transformational leadership mediated the relationship between emotional intelligence and service climate, as well as between emotional intelligence and leadership effectiveness. Scholars have explained this relationship as the ability of individuals employing transformational leadership to inspire and motivate others to accomplish beyond self- and organizational expectations and redirect feelings of frustration from setbacks to constructive solutions (Hur et al., 2011; Hussein & Yesiltas, 2020).

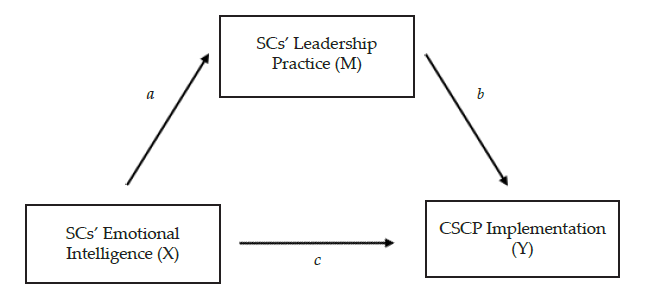

Purpose of the Study

Taken together, emotional intelligence has been identified in the counseling literature as a significant predictor of counseling self-efficacy and competence (Constantine & Gainor, 2001; Easton et al., 2008). It has also been well established in the workforce literature as being positively related to job performance and leadership outcomes (Hussein & Yesiltas, 2020; Kim & Kim, 2017). The broader leadership literature also comprises evidence in support of the mediating role of transformational leadership between emotional intelligence and performance outcomes (Hur et al., 2011; Hussein & Yesiltas, 2020; Rahman & Ferdausy, 2014). Emotional intelligence has not been examined in relation to school counselors’ CSCP implementation and service outcomes, although CSCP implementation has been widely embraced as a core of the ASCA National Model. Likewise, although emotional intelligence has been studied with counseling practice and leadership separately, we identified no empirical research that has examined the mechanisms between school counselors’ emotional intelligence, transformational leadership practice, and outcomes of program implementation. The present study seeks to address these gaps. Thus, the two research questions that guided our study were: (a) Does school counselors’ emotional intelligence predict their CSCP implementation? and (b) Does engagement in transformational leadership practice mediate the relationship between emotional intelligence and CSCP implementation? Given the synergistic focus on collaboration (or teamwork) shared by the school and workforce contexts coupled with previous empirical evidence, we hypothesized that (a) school counselors’ emotional intelligence predicts their CSCP implementation, and (b) transformational leadership practice mediates the relationship between emotional intelligence and CSCP implementation.

Method

Research Design

In the present study, we utilized a correlational, cross-sectional survey design. We used the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, version 27). To test our hypotheses, we performed a mediation analysis using Hayes’s PROCESS in order to establish the extent of influence of an independent variable on an outcome variable (through a mediator; Hayes, 2012). Mediation analysis answered how an effect occurred between variables and is based on the prerequisite that the independent variable/predictor is often considered the “causal antecedent” to the outcome variable of interest (Hayes, 2012, p. 3). Furthermore, we expected that the effects of school counselors’ emotional intelligence on their CSCP implementation would be partly explained by the effects of their engagement in transformational leadership.

Participants

Participants included for final analysis were 792 practicing school counselors in the United States, 94.6% (n = 749) of which reported to be certified/licensed as school counselors and 5.4% (n = 43) indicated to be either not certified/licensed or “unsure.” The sample’s geographic location was mostly suburban (n = 399, 50.4%), followed by rural (n = 195, 24.6%) and urban (n = 184, 23.2%); and 1.8% of participants (n = 14) did not disclose their setting. Public schools accounted for 86.2% (n = 683) of participants’ work settings, followed by charter (n = 42, 5.3%) and private (n = 40, 5.1%), while 3.4% (n = 27) of participants indicated “other” or did not disclose. For grade levels served by participants, 13% (n = 103) worked at the PK–4 level, 20.8% (n = 165) at the 5–8 level, 28.4% (n = 225) at the 9–12 level, and 37.8% (n = 299) worked at the combined K–12 level. Participants’ race/ethnicity included Asian/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (n = 26, 3.3%), Multiracial (n = 47, 5.9%), Black/African American (n = 56, 7.1%), Hispanic/Latino (n = 70, 8.8%), and White (n = 593, 74.9%). Lastly, participants’ mean age was 43, ranging from 23 to 77 years of age. Of the 792 participants, 82.4% (n = 653) identified as cisgender female, 11.0% (n = 88) as cisgender male, 0.3% (n = 2) as transgender female, 0.3% (n = 2) as transgender male, 3.8% (n = 30) chose “prefer to self-identify,” and 2.2% (n = 17) chose “not to answer.” Our sample was representative of the larger population based on the results of a recent nationwide study by ASCA (2021), in which approximately 7,000 school counselors were surveyed; demographic statistics from that study similar to ours included 88% of participants working in public, non-charter schools; 19% working at the middle school level; and 24% working in urban schools..

Procedures and Data Collection