Jun 27, 2022 | Book Reviews

by Beatriz Sheldon and Albert Sheldon

by Beatriz Sheldon and Albert Sheldon

Beatriz Sheldon, MEd, and her partner, Albert Sheldon, MD, describe their novel therapeutic approach, Complex Integration of Multiple Brain Systems (CIMBS), in this new publication. Throughout the book, references are made to the Sheldons’s 20 years of working together, 15 years of clinical experience, and 10 years of training other practitioners in CIMBS therapy. The authors emphasize that they “are practical, empirical therapists” (p. xvii). The book is seeded with references to scientists who inspire the duo, especially Daniel J. Siegel, Joseph LeDoux, Antonio Domasio, and the late Jaak Panksepp. It must be noted that CIMBS therapy as laid out in this text contains no peer-reviewed qualitative or quantitative studies; instead, the authors utilize vignettes to discuss their methods.

The brain systems referred to in CIMBS are organized into sections much like those of the triune brain model, with an additional peripheral system in the heart, lungs, and intestines. What the triune brain model labels the lizard brain relates to the primary level, the mammal brain is the secondary level, and the human brain is the tertiary level. The Sheldons assign awareness, attention, authority, autonomy, and agency (the “A Team”) to the conscious tertiary level. The secondary level holds nonconscious, inhibitory systems of fear, grief, shame, and guilt. The primary level, also nonconscious, contains the systems of safe, care, connection, sensory, assertive, play, and seeking.

The patient accesses the hidden strengths of the nonconscious mind via the CIMBS therapist’s use of techniques like Transpiring Present Moment, Go the Other Way, and Initial Directed Activation. Transpiring Present Moment is reminiscent of Fritz Perls’s emphasis on the “here-and-now.” Go the Other Way asks the patient to avoid getting bogged down in traumatic memories and instead reach for personal strengths. The CIMBS therapist cultivates the therapeutic alliance using the Therapeutic Attachment Relationship, which includes physical postures that suggest safety, reminding us of Egan’s SOLER stance taught in many counseling programs. This intervention also recommends intense focus on the patient’s micro-expressions as a guide to their conscious and nonconscious processes. Ultimately, the patient will integrate all 20 brain systems effectively and reach Fail-Safe Complex Network, a new, durable neural structure generating improved mental health.

Although the authors refer several times to the text’s internal contradictions or incongruence, the writing has the same appeal as the work of the Sheldons’s mentor, Dan Siegel, who wrote the Foreword. The book asks readers to lean on their intuition, often reminding them to “trust the process.” Nicola Swaine has provided line drawings to clarify central concepts, much as Siegel uses a curled fist to describe the triune brain. The authors relate that this text was written expressly to provide an overview of the Sheldons’s 16-part CIMBS training series (recorded and live) for students and trainees, who will find the glossary and bibliography especially useful.

In the Foreword, Siegel refers to the “cross-disciplinary framework known as interpersonal neurobiology . . . [using] universal principles discovered by independent pursuits of knowledge” (p xii). It would be useful to know which principles are considered universal in this book. Psychology sits forever on the fence between hard and soft science; some declarations of fact are based on microscopic studies of physical structures, and some are useful models that are at least partly philosophical. This text contains both. Neurologists have observed neural repairs and rerouting; thus, neuroplasticity is a demonstrable fact. The Sheldons describe 20 brain systems while noting that “one could certainly make the case for more or fewer systems” (p. 26). Clearly the number and definition of these brain systems can be thought of as helpful metaphors, a bit like Marsha Linehan describes a “wise mind” that is not a physical structure existing in the brain.

Professional counselors who like eclectic methods and enjoy pulling inspiration from many sources will appreciate CIMBS and this flagship text. The authors caution practitioners not to use CIMBS for patients who struggle with borderline personality disorder or dissociative, bipolar, or psychotic disorders. Although the Sheldons encourage clinicians to practice with their highest-functioning patients, the wise professional counselor will first disclose methods and procedures to patients.

Sheldon, B., & Sheldon, A. (2021). Complex integration of multiple brain systems in therapy. W. W. Norton.

Reviewed by: Christine Sheppard, MA, LCPC, NCC

The Professional Counselor

https://tpcwordpress.azurewebsites.net

Jun 13, 2022 | TPC Outstanding Scholar

Shaywanna Harris-Pierre, Christopher T. Belser, Naomi J. Wheeler, and Andrea Dennison received the 2021 Outstanding Scholar Award for Concept/Theory for their article, “A Review of Adverse Childhood Experiences as Factors Influential to Biopsychosocial Development for Young Males of Color.”

Shaywanna Harris-Pierre, PhD, LPC, is an assistant professor of professional counseling at Texas State University. Her research centers on the psychological and physiological impact of trauma and race-based traumatic stress. Dr. Harris-Pierre serves her community through facilitating free workshops for couples where she provides psychoeducation on communication skills. Dr. Harris-Pierre also serves the counseling profession through her position as secretary for the Association for Assessment and Research in Counseling, and her role as an editorial board member for the Journal of Addictions & Offender Counseling, Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, and the Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development.

Christopher T. Belser, PhD, NCC, is an assistant professor in the counselor education program at the University of New Orleans. He earned his PhD in counselor education and supervision at the University of Central Florida and his MEd in school counseling at Louisiana State University. Dr. Belser has experience in Louisiana public and charter schools as a middle school counselor and a high school career coach. His research interests include school counselor preparation/practice and interdisciplinary P–16 STEM career development initiatives. Dr. Belser has delivered dozens of presentations at local, state, national, and international conferences and has published numerous articles and book chapters on counseling and career-related topics. He is the current associate editor of the Journal of Child & Adolescent Counseling, served as Chi Sigma Iota’s 2020–2021 Edwin Herr Fellow, and previously won The Professional Counselor’s 2018 Dissertation Excellence Award.

Naomi J. Wheeler, PhD, NCC, LPC, LMHC, is an assistant professor in counselor education and supervision at Virginia Commonwealth University. Her research builds on her professional and clinical experiences to examine relationship health across the life span, including the role of early life family adversity (such as ACEs) and couple stress as contributors to health disparities. Dr. Wheeler is also the co-director for the Urban Education and Family Center at VCU, which serves as a hub for community-engaged research and program services that address educational attainment, economic mobility, and individual and family well-being for historically marginalized populations living in poverty from a two-generational approach. The Center strives to harness research to improve the quality of life for Black and Latinx families in the greater Richmond area through community-based work.

Andrea Dennison, PhD, is an assistant professor at Texas State University.

Read more about the TPC scholarship awards here.

Jun 13, 2022 | TPC Outstanding Scholar

Fei Shen, Yanhong Liu, and Mansi Brat received the 2021 Outstanding Scholar Award for Quantitative or Qualitative Research for their article, “Attachment, Self-Esteem, and Psychological Distress: A Multiple-Mediator Model.”

Fei Shen, PhD, is a staff therapist at the Barnes Center at the Arch – Counseling at Syracuse University. Her clinical and research interests include attachment and trauma healing. She specifically focuses on understanding the impact and prevention of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in marginalized communities, as well as identifying mediating and moderating factors that can protect survivors from the negative effects of trauma.

Yanhong Liu, PhD, NCC, is an associate professor in the Counseling & Human Services Department at Syracuse University. She also serves as the MS in School Counseling P–12 Program Coordinator. Her scholarship centers around marginalized youth and supporting systems. She has published widely and consistently in counseling as well as interdisciplinary journals on the topics of adopted youth, school bullying, school-based programs, and counselor training.

Mansi Brat, PhD, LPC, LMHC, is an adjunct professor at Syracuse University. Dr. Brat’s scholarship focuses on mindfulness-based programs (MBP), social justice, counselor professional identity and advocacy, contemplative sciences, and humanistic psychology. She has published across interdisciplinary journals and is extremely passionate about furthering her research in highlighting the many layers of implicit bias that remain critical in dismantling racism and oppression amongst dominant groups.

Read more about the TPC scholarship awards here.

Jun 13, 2022 | Article

In the ninth year of TPC‘s Dissertation Excellence Award program, the award was expanded to include two winning dissertations, one in qualitative research and one in quantitative research. After receiving submissions from across the United States and through implementation of an improved selection process, the committee selected Anabel Mifsud and Chelsey Zoldan-Calhoun to receive the 2022 Dissertation Excellence Awards. Dr. Mifsud received the award in qualitative research for her dissertation entitled Exploring Community- and Society-Level Interventions for Healing Historical Trauma: A Grounded Theory Study, and Dr. Zoldan-Calhoun received the award in quantitative research for her work entitled The Contribution of Spiritual Well-Being to the Self-Efficacy, Resilience, and Burnout of Substance Use Disorder Counselors.

Anabel Mifsud, PhD, NCC, is an assistant professor of professional practice in the counselor education program at the University of New Orleans. She earned her PhD in counselor education and supervision from the University of New Orleans and her MSc in health psychology from University College London and King’s College London. Dr. Mifsud’s research interests include historical and intergenerational trauma; multicultural issues; social justice and advocacy; the internationalization of counseling and counselor education; the role of counseling in community healing and development; and behavioral health services for immigrants, refugees, and persons with HIV. She has worked with individuals and couples experiencing homelessness and comorbid issues, persons with HIV, immigrants, and asylum seekers. Dr. Mifsud has presented at local, state, national, and international conferences and seminars and has published articles and book chapters on social justice, immigrants, and counseling ethics.

Anabel Mifsud, PhD, NCC, is an assistant professor of professional practice in the counselor education program at the University of New Orleans. She earned her PhD in counselor education and supervision from the University of New Orleans and her MSc in health psychology from University College London and King’s College London. Dr. Mifsud’s research interests include historical and intergenerational trauma; multicultural issues; social justice and advocacy; the internationalization of counseling and counselor education; the role of counseling in community healing and development; and behavioral health services for immigrants, refugees, and persons with HIV. She has worked with individuals and couples experiencing homelessness and comorbid issues, persons with HIV, immigrants, and asylum seekers. Dr. Mifsud has presented at local, state, national, and international conferences and seminars and has published articles and book chapters on social justice, immigrants, and counseling ethics.

Chelsey Zoldan-Calhoun, PhD, NCC, LPCC-S, LICDC, earned her MSEd in clinical mental health counseling from Youngstown State University and her PhD in counselor education and supervision from the University of Akron. She is an adjunct faculty member in both the Department of Psychological Sciences and Counseling at Youngstown State University and the School of Counseling at the University of Akron. She enjoys teaching courses on diagnosis, counseling interventions, and ethics, as well as supervising counseling trainees during their practicum experiences.

Chelsey Zoldan-Calhoun, PhD, NCC, LPCC-S, LICDC, earned her MSEd in clinical mental health counseling from Youngstown State University and her PhD in counselor education and supervision from the University of Akron. She is an adjunct faculty member in both the Department of Psychological Sciences and Counseling at Youngstown State University and the School of Counseling at the University of Akron. She enjoys teaching courses on diagnosis, counseling interventions, and ethics, as well as supervising counseling trainees during their practicum experiences.

In clinical practice, Dr. Zoldan-Calhoun specializes in the treatment of adults presenting with PTSD, trauma-related issues, and substance use disorders. She is a Certified EMDR Therapist and has a special interest in working with military service members, veterans, and emergency first responders. Additionally, she has a passion for working with both those in recovery from substance use disorders and their loved ones. Dr. Zoldan-Calhoun has experience providing and supervising counseling services in university and community-based mental health and addiction counseling centers across northeastern Ohio.

Dr. Zoldan-Calhoun has contributed numerous book chapters and peer-reviewed journal articles to the professional counseling literature. Her research has focused on spiritual well-being, resilience, and burnout among counselors treating substance use disorders. Dr. Zoldan-Calhoun is a member of the Editorial Review Board of The Professional Counselor and has served on boards for the American Counseling Association, Ohio Counseling Association, and Association for Humanistic Counseling. She is a previous recipient of the Ohio Counseling Association’s Graduate Student Award and the Association for Humanistic Counseling’s Emerging Leader Award.

TPC looks forward to recognizing outstanding dissertations like those of Drs. Mifsud and Zoldan-Calhoun for many years to come.

Read more about the TPC scholarship awards here.

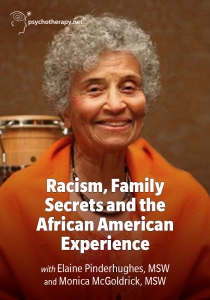

Apr 12, 2022 | Video Reviews

with Elaine Pinderhughes, interviewed by Monica McGoldrick

In the African American community, there is a theme of pain and hurt that is often hidden behind family secrets. These family secrets are deeply rooted in the African American experience of slavery and racism that is carried throughout generations. In her 35-minute interview with Monica McGoldrick, MA, LCSW, PhD (honorary), Elaine Pinderhughes, MSW, provides a comprehensive and in-depth narrative about her family heritage, supported by 30 years of research on her family’s genealogy. After the death of her father in 1976 and inspired by Alex Haley’s book entitled Roots, Pinderhughes set out to explore her own family’s roots. This video provides viewers with a glimpse into Pinderhughes’s family’s history, their secrets, and the truth that she discovered.

In the African American community, there is a theme of pain and hurt that is often hidden behind family secrets. These family secrets are deeply rooted in the African American experience of slavery and racism that is carried throughout generations. In her 35-minute interview with Monica McGoldrick, MA, LCSW, PhD (honorary), Elaine Pinderhughes, MSW, provides a comprehensive and in-depth narrative about her family heritage, supported by 30 years of research on her family’s genealogy. After the death of her father in 1976 and inspired by Alex Haley’s book entitled Roots, Pinderhughes set out to explore her own family’s roots. This video provides viewers with a glimpse into Pinderhughes’s family’s history, their secrets, and the truth that she discovered.

A strength in this video was the consistent use of a genogram that highlighted Pinderhughes’s family tree. Genograms may serve as useful tools for counselors working with African American clients and for gathering family history information during the assessment phase. On the genogram, her paternal and maternal family are identified. Pinderhughes provides a brief summary of her paternal family’s education and accomplishments, and she describes the type of community that her father grew up in; however, because of the lack of information available because of slavery, Pinderhughes was unable to research her paternal family prior to 1870.

Pinderhughes then discusses her maternal family history. She explains that her mother died when she was 16 years old, and during the video, Pinderhughes recounts her experience of growing up with a mother whom she describes as an extremely fair-skinned Black woman, who was often mistaken for White by both Black and White people. Pinderhughes reports that her mother never spoke about her biological father, and she also discusses the challenges that she experienced when attempting to obtain information about her mother’s paternity from her maternal relatives. Pinderhughes’s research revealed a shocking family secret: Her mother’s father was a White sheriff from her mother’s town, and she believes that her mother was born as a result of rape. She identifies other mixed-race maternal relatives on her genogram, who she also believes were born as a result of rape. The information provided in this part of the video reveals the hidden historical truth about the sexual abuse of Black women. Because of the pain associated with this knowledge, this information also provides insight into why Pinderhughes’s family chose to hide this secret for so long.

Within the video, Pinderhughes also broaches the salient topic of skin color, which remains a sensitive subject among African Americans. Pinderhughes is very transparent in providing the viewer with several poignant examples of her own experiences with skin color. In one example, she describes feeling like she did not “belong” to her mother, because her mother looked White and Pinderhughes did not. She then goes on to discuss an incident where she was lectured by her father for using the term dark-skinned when describing another girl. This causes her to reflect on the challenges that she experienced with having a mother who looked White and a father who looked African, and not being able to speak about skin color within her household. A final example that she provides is an internal conflict that she felt toward her paternal aunt, who came to care for her after her mother’s death, and whom she characterizes as a loving individual, yet one that looked similar to “Aunt Jemima” in her perspective. She discussed feeling ashamed of her aunt’s appearance and the dichotomy of having a mother who looked White and an aunt who looked the opposite. She discussed coming to terms with those feelings of shame around 4 months prior to this video recording and “weeping” because of it.

Elaine Pinderhughes’s transparency is both courageous and inspiring, and her family’s narrative is reflective of the African American experience. The secrets that are maintained within these families as a result of racism have the ability to do harm to each generation. Counselors-in-training and professional counselors will benefit from watching this video to gain an understanding about the historical layers of pain often carried by African Americans. The Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies encourage counselors to explore the client’s worldview as well as obtain knowledge about the client’s history (Ratts et al., 2016). This video would be valuable to utilize in courses for both multicultural counseling and marriage and family counseling.

McGoldrick, M. (Host), & Pinderhughes, E. (2021). Racism, family secrets and the African American experience [Video]. Psychotherapy.net. https://www.psychotherapy.net/video/mcgoldrick-racism-family-secrets

Reviewed by: Lori Nixon Bethea, PhD, NCC, ACS, LPC

The Professional Counselor

tpcjournal.nbcc.org

References

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar‐McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2016). Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies: Guidelines for the counseling profession. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 44(1), 28–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmcd.12035

by Beatriz Sheldon and Albert Sheldon

by Beatriz Sheldon and Albert Sheldon

Anabel Mifsud, PhD, NCC, is an assistant professor of professional practice in the counselor education program at the University of New Orleans. She earned her PhD in counselor education and supervision from the University of New Orleans and her MSc in health psychology from University College London and King’s College London. Dr. Mifsud’s research interests include historical and intergenerational trauma; multicultural issues; social justice and advocacy; the internationalization of counseling and counselor education; the role of counseling in community healing and development; and behavioral health services for immigrants, refugees, and persons with HIV. She has worked with individuals and couples experiencing homelessness and comorbid issues, persons with HIV, immigrants, and asylum seekers. Dr. Mifsud has presented at local, state, national, and international conferences and seminars and has published articles and book chapters on social justice, immigrants, and counseling ethics.

Anabel Mifsud, PhD, NCC, is an assistant professor of professional practice in the counselor education program at the University of New Orleans. She earned her PhD in counselor education and supervision from the University of New Orleans and her MSc in health psychology from University College London and King’s College London. Dr. Mifsud’s research interests include historical and intergenerational trauma; multicultural issues; social justice and advocacy; the internationalization of counseling and counselor education; the role of counseling in community healing and development; and behavioral health services for immigrants, refugees, and persons with HIV. She has worked with individuals and couples experiencing homelessness and comorbid issues, persons with HIV, immigrants, and asylum seekers. Dr. Mifsud has presented at local, state, national, and international conferences and seminars and has published articles and book chapters on social justice, immigrants, and counseling ethics. Chelsey Zoldan-Calhoun, PhD, NCC, LPCC-S, LICDC, earned her MSEd in clinical mental health counseling from Youngstown State University and her PhD in counselor education and supervision from the University of Akron. She is an adjunct faculty member in both the Department of Psychological Sciences and Counseling at Youngstown State University and the School of Counseling at the University of Akron. She enjoys teaching courses on diagnosis, counseling interventions, and ethics, as well as supervising counseling trainees during their practicum experiences.

Chelsey Zoldan-Calhoun, PhD, NCC, LPCC-S, LICDC, earned her MSEd in clinical mental health counseling from Youngstown State University and her PhD in counselor education and supervision from the University of Akron. She is an adjunct faculty member in both the Department of Psychological Sciences and Counseling at Youngstown State University and the School of Counseling at the University of Akron. She enjoys teaching courses on diagnosis, counseling interventions, and ethics, as well as supervising counseling trainees during their practicum experiences. In the African American community, there is a theme of pain and hurt that is often hidden behind family secrets. These family secrets are deeply rooted in the African American experience of slavery and racism that is carried throughout generations. In her 35-minute interview with Monica McGoldrick, MA, LCSW, PhD (honorary), Elaine Pinderhughes, MSW, provides a comprehensive and in-depth narrative about her family heritage, supported by 30 years of research on her family’s genealogy. After the death of her father in 1976 and inspired by Alex Haley’s book entitled Roots, Pinderhughes set out to explore her own family’s roots. This video provides viewers with a glimpse into Pinderhughes’s family’s history, their secrets, and the truth that she discovered.

In the African American community, there is a theme of pain and hurt that is often hidden behind family secrets. These family secrets are deeply rooted in the African American experience of slavery and racism that is carried throughout generations. In her 35-minute interview with Monica McGoldrick, MA, LCSW, PhD (honorary), Elaine Pinderhughes, MSW, provides a comprehensive and in-depth narrative about her family heritage, supported by 30 years of research on her family’s genealogy. After the death of her father in 1976 and inspired by Alex Haley’s book entitled Roots, Pinderhughes set out to explore her own family’s roots. This video provides viewers with a glimpse into Pinderhughes’s family’s history, their secrets, and the truth that she discovered.