Apr 1, 2021 | Volume 11 - Issue 2

Fei Shen, Yanhong Liu, Mansi Brat

The present study examined the relationships between childhood attachment, adult attachment, self-esteem, and psychological distress; specifically, it investigated the multiple mediating roles of self-esteem and adult attachment on the association between childhood attachment and psychological distress. Using 1,708 adult participants, a multiple-mediator model analysis following bootstrapping procedures was conducted in order to investigate the mechanisms among childhood and adult attachment, self-esteem, and psychological distress. As hypothesized, childhood attachment was significantly associated with self-esteem, adult attachment, and psychological distress. Self-esteem was found to be a significant mediator for the relationship between childhood attachment and adult attachment. In addition, adult attachment significantly mediated the relationship between self-esteem and psychological distress. The results provide insight on counseling interventions to increase adults’ self-esteem and attachment security, with efforts to decrease the negative impact of insecure childhood attachment on later psychological distress.

Keywords: childhood attachment, adult attachment, self-esteem, psychological distress, mediator

Attachment has been widely documented across disciplines, following Bowlby’s (1973) foundational work known as attachment theory. Attachment, in the context of child–parent interactions, is defined as a child’s behavioral tendency to use the primary caregiver as the secure base when exploring their surroundings (Bowlby, 1969; Sroufe & Waters, 1977). Research has shed light on the significance of childhood attachment in predicting individuals’ intrapersonal qualities such as self-esteem and emotion regulation during adulthood (Brennan & Morris, 1997), interpersonal orientations examined through attachment variation and adaptation across different developmental stages (Sroufe, 2005), and overall psychological well-being (Cassidy & Shaver, 2010; Wright et al., 2014).

Given its clinical significance, attachment has gained increased interest across disciplines. For example, childhood attachment was found to significantly predict coping and life satisfaction in young adulthood (Wright et al., 2017). Relatedly, a 30-year longitudinal study reinforces the vital role of childhood attachment in predicting individuals’ development of “the self and personality” (Sroufe, 2005, p. 352). Sroufe’s (2005) study reinforced the vital role of attachment across the life span. As an outcome variable, attachment is asserted to be associated with empathy (Ruckstaetter et al., 2017) and parenting practice in the adoptive population (Liu & Hazler, 2017). Considering the interplay between individuals’ relationship evolvement and their living contexts (Bowlby, 1973; Sroufe, 2005), attachment is examined at different stages generally labelled as childhood attachment and adult attachment, with the former focusing on the infant/child–parent relationship and the latter on adults’ generalized relationships with intimate others (e.g., romantic partners, close friends). Because of the abstract nature of attachment, it is commonly measured in the form of childhood attachment styles (Ainsworth et al., 1978) or adult attachment orientations (Turan et al., 2016).

Conceptual Framework

The present study is grounded in attachment theory, which is centered around a child’s ability to utilize their primary caregiver as the secure base when exploring surroundings, involving an appropriate balance between physical proximity, curiosity, and wariness (Bowlby, 1973; Sroufe & Waters, 1977). A core theoretical underpinning of attachment theory is the internal working model capturing a child’s self-concept and expectations of others (Bretherton, 1996). Internal working models of self and other are complementary. Namely, a child with strong internal working models is characterized with a perception of self as being worthy and deserving of love and a perception of others as being responsive, reliable, and nurturing (Bowlby, 1973; Sroufe, 2005).

In the context of attachment theory, childhood attachment is considered an outcome of consistent child–caregiver interactions and serves as the foundation for individuals’ later personality development (Bowbly, 1973; Sroufe, 2005). In line with child–caregiver interactions, Ainsworth et al. (1978) came up with three attachment styles based upon Bowlby’s seminal work, including secure, anxious-ambivalent, and anxious-avoidant attachment, following sequential phases of laboratory observations. Attachment theory was subsequently extended beyond the child–parent relationship to include later relationships in adulthood, given the parallels between these relationships (Cassidy & Shaver, 2010). Likewise, four distinct adult attachment styles (i.e., secure, dismissing, preoccupied, and fearful) are referred to based on the two-dimensional models of self and other (Konrath et al., 2014). Adult attachment styles are commonly examined under two orientations: attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety (Turan et al., 2016). Individuals showing low avoidance and low anxiety are considered securely attached, whereas those with high levels of anxiety and avoidance tend to be insecurely attached. Although childhood attachment and adult attachment are broadly considered distinct concepts in the literature, they share a spectrum of behaviors spanning from secure to insecure attachment. The levels of avoidance and anxiety involved in these behaviors are used as parameters to differentiate securely attached individuals from those who are insecurely attached.

Childhood Attachment, Self-Esteem, and Adult Attachment

Despite the conceptual overlaps, childhood attachment to caregivers and adult attachment to intimate others are commonly investigated as two distinct variables associated with individuals’ needs and features of different relationships. Childhood attachment captures a child’s distinct relationship with the primary caregiver (e.g., the mother figure) as well as their ability to differentiate the primary caregiver from other adults (Bowlby, 1969, 1973), whereas adult attachment may involve an individual’s multiple relationships (with parents, a romantic partner, or close friends). Noting the general stability of attachment from childhood to adulthood (Fraley, 2002), previous conceptual work stresses the importance of contexts in individuals’ attachment evolvement, highlighting that “patterns of adaptation” and “new experiences” reinforce each other in a reciprocal way (Sroufe, 2005, p. 349). For instance, an individual may develop secure attachment in adulthood because of healthy interpersonal experiences likely facilitated by trust, support, and nurturing received from significant others or their relationships, despite showing insecure attachment patterns in early childhood. A dynamic view of attachment development is thus warranted.

From a dynamic lens, researchers have generated evidence for the association between childhood attachment and adult attachment (Pascuzzo et al., 2013; Styron & Janoff-Bulman, 1997). For example, in a study of 879 college students (Styron & Janoff-Bulman, 1997), participants’ perception of their childhood attachment to both mother and father significantly predicted 7.9% of the variance in their adult attachment scores. Similarly, Pascuzzo et al. (2013) followed 56 adolescents at age 14 through age 22 and found that attachment insecurity to both parents and peers during adolescence was significantly associated with anxious romantic attachment in adulthood as measured by the Experience in Close Relationships Scale (ECR; Brennan et al., 1998). Studies that rely on retrospective data to assess childhood attachment (e.g., Styron & Janoff-Bulman, 1997) may be limited in validity because of time elapsed and potential compounding variables.

Childhood attachment is well recognized as the foundation for the growth of self-reliance and emotional regulation (Bowlby, 1973). Aligning with self-reliance, self-esteem appears to be frequently studied primarily through self-liking and self-competence (Brennan & Morris, 1997). Brennan and Morris (1997) defined self-liking as general self-evaluation based on perceived positive regard from others, and self-competence as concrete self-evaluation based on personal abilities and attributes. Previous research has suggested that secure attachment (to parents and peers) is significantly associated with higher levels of self-esteem (e.g., Wilkinson, 2004). In contrast, individuals who reported insecure attachment tended to endorse low self-esteem (Gamble & Roberts, 2005).

These results provide theoretical and empirical evidence for links between childhood attachment and adult attachment, but these links are likely to be indirect and mediated by other relevant variables from developmental perspectives. To our knowledge, no study has investigated the effect of self-esteem on the relationship between childhood attachment and adult attachment. The theoretical framework of attachment theory indicates that childhood attachment can have not only direct effects on adult attachment, but also indirect effects on adult attachment via self-esteem. In order to develop effective interventions tackling issues with adult attachment, it is important to examine potential mediators (e.g., self-esteem) between childhood attachment and adult attachment. To address this gap, the present study tests this hypothesized mediation function of self-esteem with a nonclinical sample of adults.

Self-Esteem, Attachment, and Psychological Distress

The extant literature comprises prolific information on the relationship between attachment and psychological well-being (Gnilka et al., 2013; Karreman & Vingerhoets, 2012; M. E. Kenny & Sirin, 2006; Turan et al., 2016; Wright et al., 2014). Existing evidence focuses on the relationship between adult attachment orientations and individuals’ psychological well-being (e.g., Karreman & Vingerhoets, 2012; Lynch, 2013; Roberts et al., 1996; Sowislo & Orth, 2013). Nevertheless, previous research has shed some light on the role of early childhood attachment in predicting psychological distresses in adulthood, including depression and anxiety (Bureau et al., 2009; Lecompte et al., 2014; Styron & Janoff-Bulman, 1997). Lecompte and colleagues (2014) conducted a longitudinal study of a sample of preschoolers (N = 68) with data collected at 4 years and again at 11–12 years; results of the study suggested that children with disorganized attachment at the baseline scored higher in both anxiety and depressive symptoms compared to those classified as securely attached.

Likewise, the effect of self-esteem on psychological distress is well established. A meta-analysis on 80 longitudinal studies published between 1994 and 2010 yielded consistent evidence supporting the relationship between low self-esteem and depressive symptoms (Sowislo & Orth, 2013). More recently, Masselink et al. (2018) examined data collected at four different points of participants’ development from early adolescence to young adulthood, which demonstrated that low self-esteem constitutes a persistent risk factor for participants’ depressive symptoms across developmental stages. Moreover, self-esteem scores in early adolescence significantly predicted the participants’ depressive symptoms at later stages, specifically during late adolescence and young adulthood.

Research has also supported the association between self-esteem, adult attachment, and psychological distress. Lopez and Gormley (2002) followed 207 college students from the beginning to the end of their freshman year and identified adjustment outcomes in association with the participants’ attachment styles and changes of their attachment styles measured by the ECR (e.g., secure-to-insecure attachment, insecure-to-secure attachment). The authors found that participants who remained securely attached scored higher in self-confidence and lower in both psychological distress and reactive coping compared to those who reported consistent insecure attachment. Moreover, participants who maintained secure attachment presented better outcomes in self-confidence and psychological well-being than the comparative group with secure-to-insecure or insecure-to-secure attachment changes (Lopez & Gormley, 2002). Adult attachment (measured by the ECR) was also found to be a mediator for the effects of traumatic events on post-traumatic symptomatology among a sample of female college students (Sandberg et al., 2010). In addition, Roberts et al. (1996) suggested attachment insecurity contributed to negative beliefs about oneself, which in turn activated cognitive structures of psychological distress, such as depression and anxiety, with a sample of 152 undergraduate students.

Taken together, the literature provides consistent support for the significant relationships between childhood attachment and various outcome variables in later adulthood, including adult attachment, self-esteem, and psychological distress. It further reveals a two-fold gap: (a) the variables tended to be investigated separately in previous studies, yet the mechanisms among these variables remained underexplored; and (b) little is known about the role of self-esteem and adult attachment in the association between childhood attachment and psychological distress. Disentangling the mechanisms, including potential mediating roles, involved in the variables will enrich the current knowledge based on attachment and can facilitate counseling interventions surrounding the effects of childhood attachment. In tackling the gap, three hypotheses were posed:

1. Childhood attachment is significantly associated with adult attachment, self-esteem, and psychological distress.

2. Self-esteem mediates the relationship between perceived childhood attachment and adult attachment.

3. Adult attachment mediates the relationship between self-esteem and

psychological distress.

Method

Participants

Of the 2,373 voluntary adult participants who took the survey, 1,708 (72%) completed 95% of all the questions and were retained for final analysis. Among the participants, 76.2% (n = 1,302) were female, 22.3% (n = 381) were male, and 1.3% (n = 25) chose not to specify their gender. The mean age of the participants was 29.89, ranging from 18 to 89 years old (SD = 12.44). A total of 66.3% (n = 1,133) of participants described themselves as White/European American, 8.7% (n = 148) as African American, 10.2% (n = 175) as Asian/Pacific Islander, 2.6% (n = 44) as American Indian/Native American, 7.3% (n = 124) as biracial or multiracial, 3.6% (n = 61) as other race, and 1.3% (n = 23) did not specify.

Sampling Procedures

The study was approved by the university’s IRB. We posted the recruitment information on various websites (e.g., Facebook, discussion board, university announcement board, Craigslist) in order to recruit a diverse pool of participants. Individuals who were 18 years old or above and were able to fill out the questionnaire in English were eligible for participating in this project. Participants were directed to an online Qualtrics survey consisting of the measures discussed in the following section. An informed consent form was included at the beginning of the survey outlining the confidentiality, voluntary participation, and anonymity of the study. Participants were prompted to enter their email addresses to win one of ten $15 e-gift cards. Participants’ email addresses were not included in the survey questions and data analysis.

Measures

Psychological Distress

Psychological distress was measured using the 10-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10; Kessler et al., 2003). Participants were asked about their emotional states in the past four weeks (e.g., “How often did you feel nervous?”). Responses were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (None of the time) to 4 (All of the time). Scores were averaged, with a higher score indicating a higher level of psychological distress. Previous studies using K10 have provided evidence of validity (Andrews & Slade, 2001). The internal consistency for K10 has been well established with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient ranging from .88 (Easton et al., 2017) to .94 (Donker et al., 2010). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .94.

Childhood Attachment

Childhood attachment was measured using the Parental Attachment subscale of the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA; Armsden & Greenberg, 1987). Previous research has demonstrated evidence that this measure has great convergent and concurrent validity (M. E. Kenny & Sirin, 2006). The IPPA has been used to recall childhood attachment in adult populations (Aspelmeier et al., 2007; Cummings-Robeau et al., 2009). This 25-item subscale directs participants to recall their attachment to the parent(s) or caregiver(s) who had the most influence on them during childhood. The subscale consists of three dimensions, including 10 items on trust, nine items on communication, and six items on alienation. Some sample items are: “My parent(s)/primary caregiver(s) accepts me as I am” for trust, “I tell my parent(s)/primary caregiver(s) about my problems and troubles)” for communication, and “I do not get much attention from my parent(s)/primary caregiver(s)” for alienation. Participants rated the items using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Almost never or never true) to 5 (Almost always or always true). Items were averaged to form the subscale, with a higher score reflecting more secure childhood attachment. The subscale has demonstrated high internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of .93 (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for the subscale was .96.

Adult Attachment

Adult attachment was measured using the ECR (Brennan et al., 1998). The ECR consists of 36 items with 18 items assessing each of the two orientations: attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance. In order to avoid confounding factors, we only assessed adult attachment with close friends or romantic partners, as relationships with parents can confound the childhood attachment outcomes. Responses were rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 7 (Strongly agree). Two scores were averaged, with a higher score reflecting a higher level of attachment anxiety or avoidance. In terms of validity, the ECR subscales have been found to be positively associated with psychological distress and intention to seek counseling, and negatively associated with social support (Vogel & Wei, 2005). The ECR has a high internal consistency for both the anxiety (α = .91) and avoidance (α = .94) dimensions (Brennan et al., 1998). For this study, Cronbach’s alphas for attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance were .93 and .92, respectively.

Self-Esteem

Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale (RSES; Rosenberg, 1965) is a 10-item scale designed to assess an adult’s self-esteem. The scale assesses both self-competency (e.g., “I feel that I have a number of good qualities”) and self-liking (e.g., “I certainly feel useless at times”). Responses were coded using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 4 (Strongly agree). Negatively worded statements were reverse-coded. Scores were averaged, with a higher score reflecting a higher level of self-esteem. RSES has been frequently used in various studies with high reliability and validity (Brennan & Morris, 1997; Chen et al., 2017). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .89.

Data Analysis

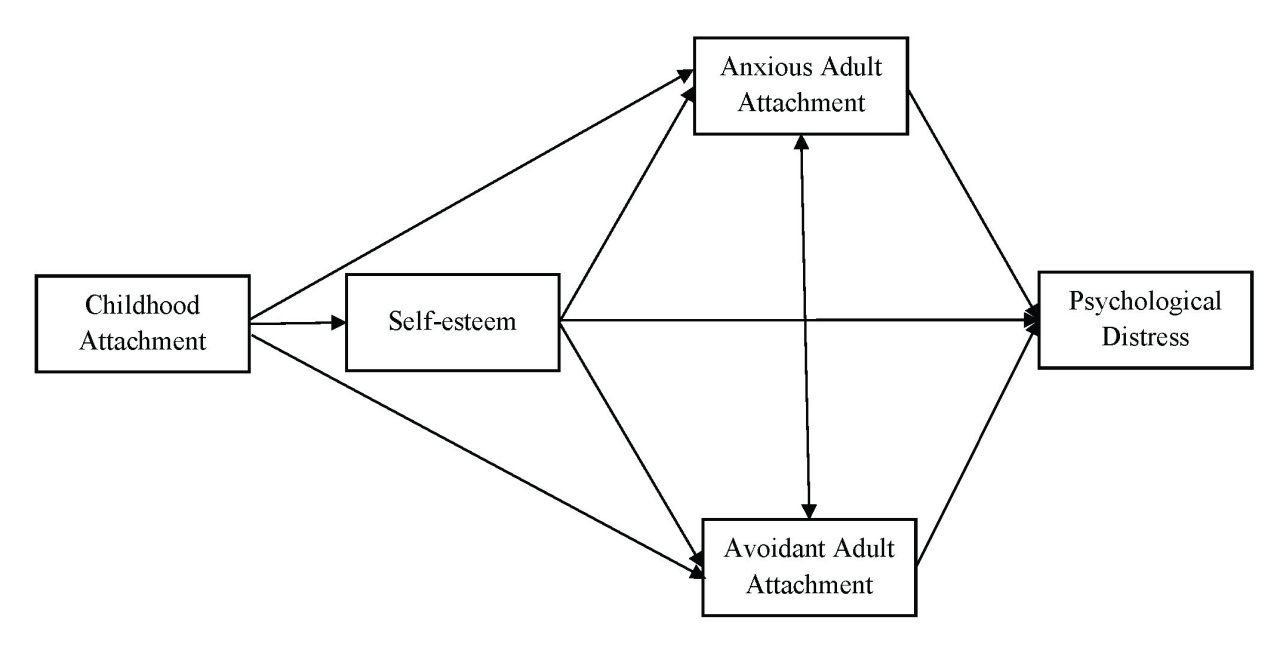

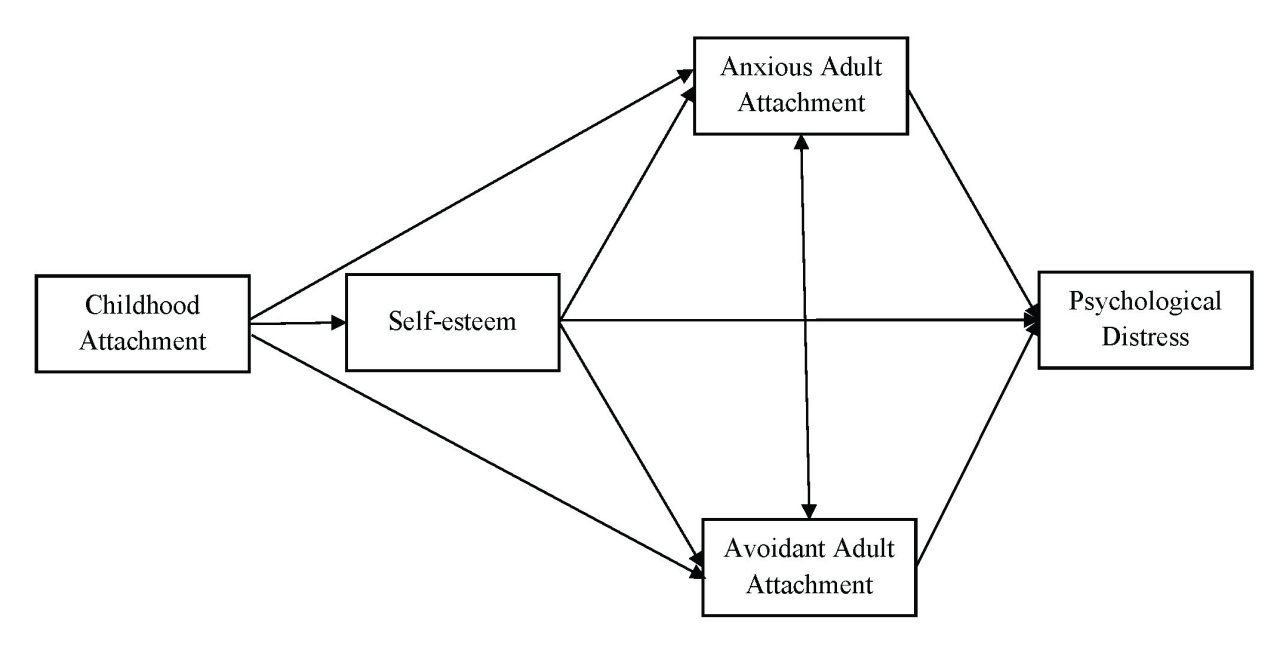

Descriptive statistics were computed using SPSS version 23 followed by a multiple-mediator model analysis using Mplus version 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012). Missing data were treated with the full information maximum likelihood estimation in Mplus, which was one of the most pragmatic approaches in producing unbiased parameter estimates (Acock, 2005). The multiple-mediator model includes childhood attachment as the predictor, self-esteem and adult attachment anxiety and avoidance as mediators, and psychological distress as the outcome variable (see Figure 1). The mediation analysis was conducted using bootstrapping procedures (J = 2,000), which was a resampling method to construct a confidence interval for the indirect effect (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Several model fit indices based on Kline’s (2010) guidelines were employed, including the ratio of chi-square to degree of freedom (χ2/df), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI), and standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR). Indicators of good model fit are a nonsignificant chi-square value, a CFI and TLI of .90 or greater, RMSEA of .08 or less, and an SRMR of .05 or less (Hooper et al., 2008).

Figure 1

Multiple-Mediator Model: Self-Esteem, Anxious Adult Attachment, and Avoidant Adult Attachment as Multiple Mediators Between Childhood Attachment and Psychological Distress

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

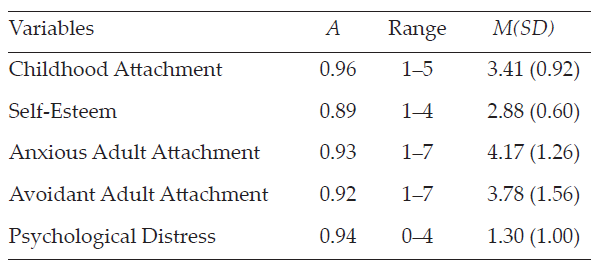

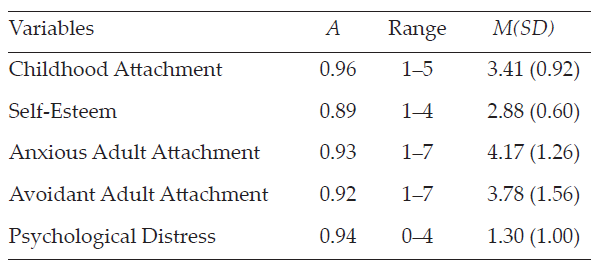

The descriptive statistics of each variable are reported in Table 1.

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics for Variables (N = 1,708)

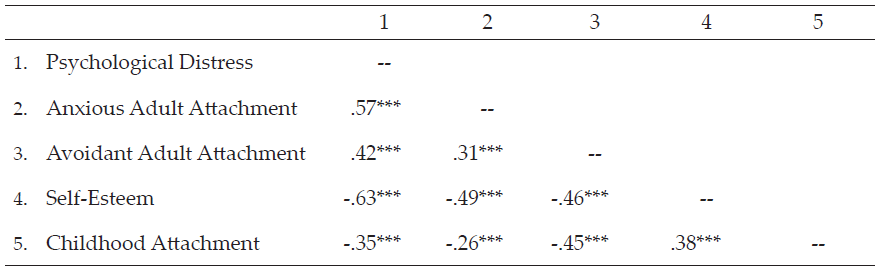

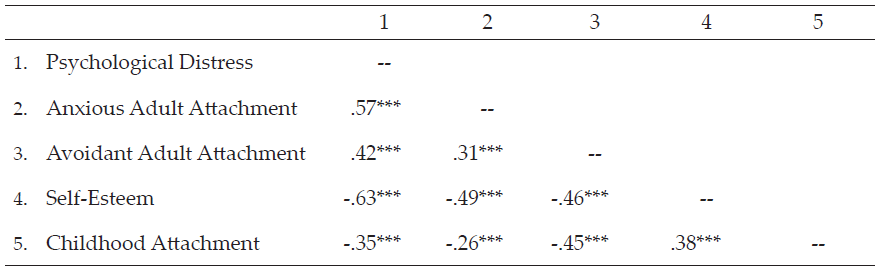

Pearson’s correlations between variables were computed. All bivariate statistics are presented in Table 2 and provided full support for our Hypothesis 1. For instance, childhood attachment was positively associated with self-esteem (r = .38, p < .001) and negatively correlated with adult attachment anxiety (r = -.26, p < .001) and avoidance (r = -.45, p < .001), as well as with psychological distress (r = -.35, p < .001). Significant negative correlations were found between self-esteem and adult attachment anxiety (r = -.49, p < .001) and avoidance (r = -.46, p < .001), and between self-esteem and psychological distress (r = -.63, p < .001). Both adult attachment anxiety (r = .57, p < .001) and avoidance (r = .42, p < .001) were positively associated with psychological distress. Significant correlation was found between adult attachment anxiety and avoidance (r = .31, p < .001).

Table 2

Correlation Matrix of Variables (N = 1,708)

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001 (two-tailed).

The Multiple-Mediator Model

The multiple-mediator model involving self-esteem and adult attachment as mediators, with bootstrapping procedures, yielded satisfactory fit indices: χ2(1) = 12.24, p < .001, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 0.96, SRMR = .01. However, the index of RMSEA = .08, 90% CI [0.05, 0.12] indicated a mediocre fit, with the upper value of 90% CI larger than the suggested cutoff score of 0.08. D. A. Kenny et al. (2015) suggested that the models with small degrees of freedom had the average width of the 90% CI above 0.10, unless the sample size was extremely large. The nonsignificant χ2 value was interpreted as a good fit index.

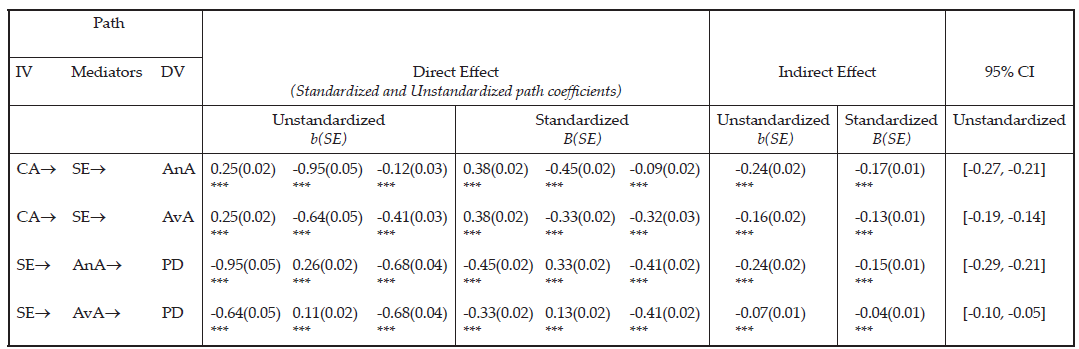

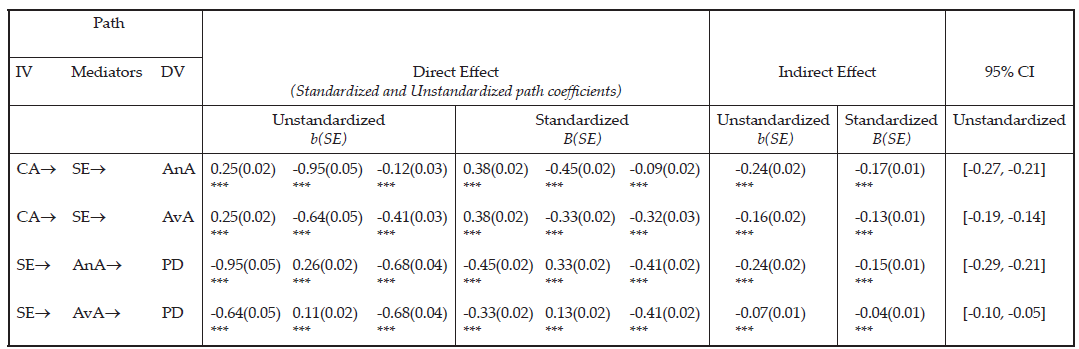

The present study further revealed that secure childhood attachment was associated with high self-esteem (β = .25, p < .001) and low levels of anxiety (β = -.12, p < .001) and avoidance (β = -.41, p < .001) of adult attachment. Meanwhile, high self-esteem was associated with low anxiety (β = -.95, p < .001) and low avoidance (β = -.64, p < .001) of adult attachment. In addition, high self-esteem (β = -.68, p < .001) and low adult attachment anxiety (β = .26, p < .001) and avoidance (β = .11, p < .001) were significantly associated with low psychological distress. The results supported both Hypotheses 2 and 3 in that self-esteem mediated the relationship between childhood attachment and adult attachment, and adult attachment mediated the relationship between self-esteem and psychological distress.

The mediating role of self-esteem was examined using bootstrapping procedures. Results demonstrated that self-esteem significantly mediated the association between childhood attachment and adult attachment anxiety (b = -.24, 95% CI [-0.27, -0.21]) and avoidance (b = -.16, 95% CI [-0.19, -0.14]).

The present study further supported the mediating role of adult attachment (i.e., anxiety and avoidance). The association between self-esteem and psychological distress was significantly mediated by both adult attachment anxiety (b = -.24, 95% CI [-0.29, -0.21]) and avoidance (b = -.07, 95% CI [-0.10, -0.05]). Mediation effects are denoted in Table 3.

Table 3

Mediation Analysis With Bootstrapping: Unstandardized and Standardized Estimates and Confidence Intervals for Mediation Effects

Note. Bootstrap J = 2,000, CI = confidence interval; IV = independent variable; DV = dependent variable; CA = Childhood Attachment; SE = Self-Esteem; AnA = Anxious Adult Attachment; AvA = Avoidant Adult Attachment; PD = Psychological Distress. Direct effect of path direction, IV® Mediator, Mediator ® DV, IV ® DV. Statistical significance was evaluated based on whether 95% bias corrected bootstrap CIs include zero or not. If zero was included in the CI, then it was not a significant indirect effect. Model fit: χ2(1) = 12.24, p < .001, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 0.96, SRMR = .01, RMSEA = .08 (90% CI [0.05, 0.12]).

Discussion

The present study highlights the significance of childhood attachment and its associations with self-esteem and psychological distress in adulthood. Participants who reported secure childhood attachment scored higher on self-esteem and lower on psychological distress. Secure childhood attachment was also found to be associated with low adult attachment anxiety and avoidance. Our study builds upon previous research (e.g., Sroufe, 2005) to capture the complexity of key variables related to attachment and its evolvement from childhood to adulthood. The results shed further light on the mechanisms among childhood attachment, self-esteem, adult attachment, and psychological distress. Self-esteem was found to be a significant mediator between childhood attachment and adult attachment; meanwhile, adult attachment was found to be a mediator between self-esteem and psychological distress.

The findings support Hypothesis 1 in that individuals with more secure childhood attachment reported higher levels of self-esteem, lower levels of adult attachment anxiety and avoidance, and less psychological distress. The results echo attachment theory (Bowlby, 1973), positing childhood attachment as a predictor of later adjustment as well as self-esteem, indicating that the quality of attachment appears to be intimately related to how to cope with stress and how to perceive oneself (Wilkinson, 2004). The results are also consistent with previous research that highlighted secure childhood attachment as a protective factor against anxiety, depression, and later emotional and relational distress (e.g., Karreman & Vingerhoets, 2012).

Results also lend support to Hypothesis 2 in that self-esteem mediated the relationship between childhood attachment and adult attachment. Self-esteem as a mediator echoed previous research that indicated the influence of childhood attachment on one’s self-esteem may be mitigated by expanded social networks in adulthood (Steiger et al., 2014). For instance, it is likely that improving self-esteem through peer connections (e.g., friendship; romantic relationships) may contribute to individuals’ adaptation to close relationships and enhance attachment security in adulthood, despite their insecure attachment with primary caregivers in childhood (Fraley, 2002; Sroufe, 2005).

Congruent with Hypothesis 3, adult attachment was a mediator for the relationship between self-esteem and psychological distress. Previous research provided evidence that low self-esteem increases the risk of developing psychological distress such as depressive and anxious symptoms (Li et al., 2014); nevertheless, individuals may experience less psychological impact with secure attachment manifested through their close relationships. Little is known about the relationship between insecure adult attachment (i.e., anxious and avoidant attachment) and psychological distress, and the mediating role of adult attachment has rarely been addressed. In a sample of 154 women in a community context, Bifulco et al. (2006) found that fearful and angry-dismissive attachment partially mediated the relationship between childhood adversity and depression or anxiety. The present study extends the Bifulco et al. study to include a larger, gender-inclusive, and racially diverse population that captures a wider age range. Further, using continuous measurements, the present study counteracts the limitations of dichotomous measures used in Bifulco et al.’s study, thus reflecting the spectrum and complexity of attachment.

Implications for Counseling Practice

The present study sheds light on interventions for clients’ psychological distress. The results corroborated positive associations between psychological distress and insecure childhood attachment and attachment anxiety and avoidance during adulthood. Although adults can no longer change their childhood experiences, including their attachment-related adversities, interventions that target improving adult attachment may still mitigate the negative effect of childhood attachment on psychological distress later during adulthood. Considering the reciprocal influence noted between self-esteem and adult attachment (Foster et al., 2007), counseling strategies encompassing both self-esteem and adult attachment are thus desirable.

Specifically, counselors could conceptualize self-esteem in a relational context in which they may incorporate clients’ support systems (e.g., partner, close friends, parents) into the treatment. A key treatment goal may be utilizing close relationships to boost self-esteem. On the contrary, counselors may engage clients with low self-esteem in communicating their attachment needs while involving significant others (e.g., partners) to enact positive responses, such as attentive listening and validation of mutual needs. Counselors are encouraged to assess how childhood attachment experiences may have influenced the client’s adult attachment, as insecure attachment may lead to challenges with perceived trustworthiness of self and others, which could hinder growth in the interpersonal relationships. Clients may further benefit from reflecting over specific attachment behaviors and interactional patterns within close relationships (e.g., how they manage proximity to an attachment figure when they experience distress) in order to restructure and enhance their attachment security internally and externally (Cassidy et al., 2013).

The finding of self-esteem as a significant mediator supports the proposition that self-esteem is responsive to life events and that these can influence one’s perception and evaluation of self. Previous research indicated that individuals with low self-esteem may be easily triggered by stressful life events and consequently respond irrationally and negatively (Taylor & Montgomery, 2007). Counselors may consider adapting Fennell’s (1997) Cognitive Behavioral Therapy model comprising early experience, bottom line, and rules for living to help clients enhance self-esteem. Fennell’s model suggests that clients’ early experiences (e.g., childhood attachment, traumatic experience, cultural context) may have an influence on the development of a fundamental bottom line about themselves (e.g., “I am not good enough,” “I am worthless”). Counselors may further assist clients with mapping out the rules for living (e.g., dysfunctional assumptions) related to distorted thoughts on what they should do in order to cultivate their core beliefs (as being loved or accepted or vice versa). For example, if clients have formed insecure attachment during childhood (early experience), they may develop a bottom line that “I am not good enough.” In making efforts to feel accepted in the family, they may have the rules for living that “I have to receive all As in all my classes.” If clients fail to achieve the rules for living, they likely would develop anxious and depressive symptoms, which may activate the confirmation of the bottom line. To counteract the negative patterns, counselors may work with clients to process the impact of early experience (e.g., early insecure attachment) on their bottom line and revise the rules of living to develop healthier coping strategies. When clients develop alternative rules of living, counselors may further help them to re-evaluate the bottom line and enhance self-acceptance.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Although the results supported all three hypotheses, the present study was subject to a few limitations. First, the self-report measures may have been subject to biases, especially for the memory of childhood attachment. Another limitation pertains to a retrospective assessment of perceptions of childhood attachment that may be changed over time because of life experiences (e.g., death, parental divorce). Relatedly, the cross-sectional study could not capture the changes over a period of time. Not knowing the types of childhood attachment (i.e., anxious attachment, avoidant attachment) presented as another limitation for researchers’ understanding of the variations of attachment and how each type might impact long-term outcomes. In the future, researchers may consider longitudinal studies to explore the variations and changes in attachment over the life span and examine what other mechanisms contribute to the changes to protect against the negative impact. Future research may also incorporate other-report data filled out by significant others (e.g., parents, romantic partners) to minimize social desirability and provide multiple perspectives.

Conclusion

Attachment theory provides a strong theoretical framework in understanding individuals’ psychological well-being over the life span (DeKlyen & Greenberg, 2008). Informed by attachment theory, the present study investigated the mediating roles of self-esteem and adult attachment (measured through the levels of anxiety and avoidance) on the relations between childhood attachment and psychological distress, and between self-esteem and psychological distress, respectively. The multiple-mediator analysis with bootstrapping supports both self-esteem and adult attachment as significant mediators. Our results also support the associations between childhood attachment with self-esteem, adult attachment, and psychological distress. The study contributes to the gap pertaining to adult attachment and provides practical implications for counselors working in various settings in their work with clients surrounding attachment security, self-esteem, and psychological well-being.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Acock, A. C. (2005). Working with missing values. Journal of Marriage and Family Therapy, 67(4), 1012–1028.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00191.x

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Andrews, G., & Slade, T. (2001). Interpreting scores on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10). Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 25(6), 494–497. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-842x.2001.tb00310.x

Armsden, G. C., & Greenberg, M. T. (1987). The Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 16(5), 427–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02202939

Aspelmeier, J. E., Elliott, A. N., & Smith, C. H. (2007). Childhood sexual abuse, attachment, and trauma symptoms in college females: The moderating role of attachment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31(5), 549–566.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.12.002

Bifulco, A., Kwon, J., Jacobs, C., Moran, P. M., Bunn, A., & Beer, N. (2006). Adult attachment style as mediator between childhood neglect/abuse and adult depression and anxiety. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 41, 796–805. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-006-0101-z

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss, Vol. 1: Attachment. Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss. Vol. 2: Separation: Anxiety and anger. Basic Books.

Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46–76). Guilford.

Brennan, K. A., & Morris, K. A. (1997). Attachment styles, self-esteem, and patterns of seeking feedback from romantic partners. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(1), 23–31.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167297231003

Bretherton, I. (1996). Internal working models of attachment relationships as related to resilient coping. In G. G. Noam & K. W. Fischer (Eds.), Development and vulnerability in close relationships (pp. 3–27). Lawrence Erlbaum.

Bureau, J. F., Easlerbrooks, M. A., & Lyons-Ruth, K. (2009). Attachment disorganization and controlling behavior in middle childhood: Maternal and child precursors and correlates. Attachment & Human Development, 11(3), 265–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730902814788

Cassidy, J., Jones, J. D., & Shaver, P. R. (2013). Contributions of attachment theory and research: A framework for future research, translation, and policy. Development and Psychopathology, 25(4), 1415–1434.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579413000692

Cassidy, J., & Shaver, P. R. (Eds.). (2010). Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed.). Guilford.

Chen, W., Zhang, D., Pan, Y., Hu, T., Liu, G., & Luo, S. (2017). Perceived social support and self-esteem as mediators of the relationship between parental attachment and life satisfaction among Chinese adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 108, 98–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.12.009

Cummings-Robeau, T. L., Lopez, F. G., & Rice, K. G. (2009). Attachment-related predictors of college students’ problems with interpersonal sensitivity and aggression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 28(3),

364–391. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2009.28.3.364

DeKlyen, M., & Greenberg, M. T. (2008). Attachment and psychopathology in childhood. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 637–665). Guilford.

Donker, T., Comijs, H., Cuijpers, P., Terluin, B., Nolen, W., Zitman, F., & Penninx, B. (2010). The validity of the Dutch K10 and extended K10 screening scales for depressive and anxiety disorders. Psychiatry Research, 176(1), 45–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2009.01.012

Easton, S. D., Safadi, N, S., Wang, Y., & Hasson, R. G., III. (2017). The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale: Translation and validation of an Arabic version. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 15(1), 215.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0783-9

Fennell, M. J. V. (1997). Low self-esteem: A cognitive perspective. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 25(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465800015368

Foster, J. D., Kernis, M. H., & Goldman, B. M. (2007). Linking adult attachment to self-esteem stability. Self and Identity, 6(1), 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860600832139

Fraley, R. C. (2002). Attachment stability from infancy to adulthood: Meta-analysis and dynamic modeling of developmental mechanisms. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6(2), 123–151.

https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0602_03

Gamble, S. A., & Roberts, J. E. (2005). Adolescents’ perceptions of primary caregivers and cognitive style: The roles of attachment security and gender. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 29, 123–141.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-005-3160-7

Gnilka, P. B., Ashby, J. S., & Noble, C. M. (2013). Adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism as mediators of adult attachment styles and depression, hopelessness, and life satisfaction. Journal of Counseling & Development, 91(1), 78–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2013.00074.x

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. R. (2008). Structural equation modeling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal on Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60.

Karreman, A., & Vingerhoets, A. J. J. M. (2012). Attachment and well-being: The mediating role of emotion regulation and resilience. Personality and Individual Differences, 53(7), 821–826.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.06.014

Kenny, D. A., Kaniskan, B., & McCoach, D. B. (2015). The performance of RMSEA in models with small degrees of freedom. Sociological Methods & Research, 44(3), 486–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124114543236

Kenny, M. E., & Sirin, S. R. (2006). Parental attachment, self-worth, and depressive symptoms among emerging adults. Journal of Counseling & Development, 84(1), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2006.tb00380.x

Kessler, R. C., Barker, P. R., Colpe, L. J., Epstein, J. F., Gfroerer, J. C., Hiripi, E., Howes, M. J., Normand, S.-L. T., Manderscheid, R. W., Walters, E. E., & Zaslavsky, A. M. (2003). Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60(2), 184–189. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184

Kline, R. B. (2010). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). Guilford.

Konrath, S. H., Chiopik, W. J., Hsing, C. K., & O’Brien, E. (2014). Changes in adult attachment styles in American college students over time: A meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 18(4), 326–348.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868314530516

Lecompte, V., Moss, E., Cyr, C., & Pascuzzo, K. (2014). Preschool attachment, self-esteem and the development of preadolescent anxiety and depressive symptoms. Attachment & Human Development, 16(3), 242–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2013.873816

Li, S. T., Albert, A. B., & Dwelle, D. G. (2014). Parental and peer support as predictors of depression and self-esteem among college students. Journal of College Student Development, 55(2), 120–138.

https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2014.0015

Liu, Y., & Hazler, R. J. (2017). Predictors of attachment security in children adopted from China by US families: Implication for professional counsellors. Asia Pacific Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 8(2), 115–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/21507686.2017.1342675

Lopez, F. G., & Gormley, B. (2002). Stability and change in adult attachment style over the first-year college transition: Relations to self-confidence, coping, and distress patterns. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 49(3), 355–364. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.49.3.355

Lynch, M. F. (2013). Attachment, autonomy, and emotional reliance: A multilevel model. Journal of Counseling & Development, 91(3), 301–312. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2013.00098.x

Masselink, M., Van Roekel, E., & Oldehinkel, A. J. (2018). Self-esteem in early adolescence as predictor of depressive symptoms in late adolescence and early adulthood: The mediating role of motivational and social factors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47, 932–946. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0727-z

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2012). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). http://www.statmodel.com/download/users

guide/Mplus%20user%20guide%20Ver_7_r3_web.pdf

Pascuzzo, K., Cyr, C., & Moss, E. (2013). Longitudinal association between adolescent attachment, adult romantic attachment, and emotion regulation strategies. Attachment & Human Development, 15(1), 83–103.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2013.745713

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891.

https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

Roberts, J. E., Gotlib, I. H., & Kassel, J. D. (1996). Adult attachment security and symptoms of depression: The mediating roles of dysfunctional attitudes and low self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(2), 310–320. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.2.310

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press.

Ruckstaetter, J., Sells, J., Newmeyer, M. D., & Zink, D. (2017). Parental apologies, empathy, shame, guilt, and attachment: A path analysis. Journal of Counseling & Development, 95(4), 389–400.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12154

Sandberg, D. A., Suess, E. A., & Heaton, J. L. (2010). Attachment anxiety as a mediator of the relationship between interpersonal trauma and posttraumatic symptomatology among college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25(1), 33–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260508329126

Sowislo, J. F., & Orth, U. (2013). Does low self-esteem predict depression and anxiety? A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 139(1), 213–240. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028931

Sroufe, L. A. (2005). Attachment and development: A prospective, longitudinal study from birth to adulthood. Attachment & Human Development, 7(4), 349–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730500365928

Sroufe, L. A., & Waters, E. (1977). Attachment as an organizational construct. Child Development, 48(4), 1184–1199. https://doi.org/10.2307/1128475

Steiger, A. E., Allemand, M., Robins, R. W., & Fend, H. A. (2014). Low and decreasing self-esteem in adolescence predict adult depression two decades later. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(2), 325–338. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035133

Styron, T., & Janoff-Bulman, R. (1997). Childhood attachment and abuse: Long-term effects on adult attachment, depression, and conflict resolution. Child Abuse & Neglect, 21(10), 1015–1023.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(97)00062-8

Taylor, T. L., & Montgomery, P. (2007). Can cognitive-behavioral therapy increase self-esteem among depressed adolescents? A systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review, 29(7), 823–839.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.01.010

Turan, N., Kocalevent, R.-D., Quintana, S. M., Erdur-Baker, Ö., & Diestelmann, J. (2016). Attachment orientations: Predicting psychological distress in German and Turkish samples. Journal of Counseling & Development, 94(1), 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12065

Vogel, D. L., & Wei, M. (2005). Adult attachment and help-seeking intent: The mediating roles of psychological distress and perceived social support. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(3), 347–357.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.3.347

Wilkinson, R. B. (2004). The role of parental and peer attachment in the psychological health and self-esteem of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 33, 479–493.

https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOYO.0000048063.59425.20

Wright, S. L., Firsick, D. M., Kacmarski, J. A., & Jenkins-Guarnieri, M. A. (2017). Effects of attachment on coping efficacy, career decision self-efficacy, and life satisfaction. Journal of Counseling & Development, 95(4), 445–456. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12159

Wright, S. L., Perrone-McGovern, K. M., Boo, J. N., & White, A.V. (2014). Influential factors in academic and career self-efficacy: Attachment, supports, and career barriers. Journal of Counseling & Development, 92(1), 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00128.x

Fei Shen, PhD, is a staff therapist at Syracuse University. Yanhong Liu, PhD, NCC, is an assistant professor at Syracuse University. Mansi Brat, PhD, LPC, is a staff therapist at Syracuse University. Correspondence may be addressed to Fei Shen, 150 Sims Drive, Syracuse, NY 13210, fshen02@syr.edu.