Sep 6, 2014 | Article, Volume 1 - Issue 2

Michael Lee Powell, Rebecca A. Newgent

Aligning with a particular theoretical orientation or personal multi-theory integration is often a formidable task to entry-level counselors. A better understanding of how personal strengths and abilities fit with theoretical approaches may facilitate this process. To examine this connection, thirty-five mental health professionals completed a series of inventories to determine if passive counselors adhere to more nondirective, insight-oriented theories, while assertive counselors adhere to more directive, action-oriented approaches. Analyses revealed a significant difference between level of assertiveness and theoretical orientation, with action-oriented counselors demonstrating significantly higher levels of assertiveness than insight-oriented counselors. Implications for professional practice and counselor education are discussed.

Keywords: assertiveness, theoretical orientation, action-oriented, insight-oriented, professional practice, counselors

Murdock, Banta, Stromseth, Viene, and Brown (1998) assert that research into the predictors of theory construction benefits the profession, because the information aids educators and clinical supervisors in helping students and beginning counselors to adopt an appropriate theoretical orientation. If counselors knew what personal strengths and abilities fit best with potential therapeutic approaches (Johnson, Germer, Efran, & Overton, 1988), then adhering to a model of therapy might be less complex, more satisfying, and essentially advantageous for their clientele. To assist in the alleviation of this issue, this study intends to examine the difference between insight-oriented and action-oriented counselors on level of assertiveness.

One of the most exciting and typically daunting tasks for counselors is choosing a theoretical orientation (Halbur & Halbur, 2005). Particularly, choosing one that adequately explains human development and functioning while also attempting to purport interventions that can facilitate greater personal growth and behavioral change in clients. Doing so, however, requires more than simple investigation into the diverse multitude of therapeutic approaches available to counselors. According to Patterson (1985), extensive self-exploration into one’s own personality, values, abilities, and beliefs about human nature are equally salient, as is mandatory longstanding experience. Even then, counselors find that no one theory may suffice or help explain human complexity, which leads to personal theory construction, attempts at theoretical integration, and/or technical eclecticism (Corey, 2008).

Simplifying personal theory construction, or single/multi-theory integration, might assist counselors in choosing a theory that is a better fit for them. With over 400 available therapeutic models (Corsini & Wedding, 2008), counselors find themselves overwhelmed and indifferent to obtaining a sound theoretical foundation, and opt for more technique-oriented practices (Cheston, 2000; Freeman, 2003). Improvements in the manner in which counselors choose a theory would advance knowledge and understanding about the usefulness of adhering to a particular model of therapy. This would also increase treatment consistency and decrease the haphazard, inexperienced practice common with counselors who compile a therapeutic toolbox of empirically-supported interventions, but fail to grasp the rationale that supports their use (Corey, 2008). According to Corsini and Wedding (2008), good therapists follow a particular theory and use techniques associated with that theory and that “technique and method are always secondary to the clinician’s sense of what is the right thing to do with a given client at a given moment in time” (Corsini & Wedding, 2008, p. 10). Further, MacCluskie (2010) discusses the role of theory in counseling and states that, “Practitioners need theories because it is our theory that drives our understanding and conceptualization of the client, the client’s problem, and what strategies and techniques we might use to help the client grow and/or feel better” (p. 9).

Style and Theoretical Orientation

Researchers interested in how a counselor constructs or chooses a particular theory examine multiple predictive factors. For example, Scragg, Bor, and Watts (1999) examined graduate students’ scores on personality assessments as predictors of a chosen theoretical model. They categorized students into two groups derived from their interest in studying directive or nondirective approaches, and found that students interested in the nondirective theories tend to prefer dealing with the abstract and working in an unstructured manner, and that students interested in learning more directive approaches appear to have more charm and leadership ability than the nondirective group. Similarly, Erickson (1993) found differences between theoretical groups based on personality assessment. She measured counselors using the thinking/feeling typology of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator and found that thinking types reported preferences toward cognitive approaches (e.g., REBT), and feeling types favored affective approaches (e.g., Person-Centered).

Murdock et al. (1998) investigated whether one’s philosophical assumptions, interpersonal style, and supervisor orientation were consistent with specific theoretical orientations. They found that existential/gestalt counselors favor holistic philosophies rather than behavioral ones, which is consistent with their orientation. The systems/interpersonal group preferred observable and contextual causes of behavior rather than mental explanations, and the cognitive/cognitive-behavioral counselors scored high on elementarism (mechanistic, as opposed to holistic) due to their tendency to attend to client’s thoughts and behaviors as the source of change. The psychoanalytics, however, were the only group to score significantly higher on all other measures, meaning they tend to be more dominant interpersonally and prefer supervision from same-orientation supervisors.

Walton (1978) examined counselor self-concept, or view of personal self, as a potential factor predicting theoretical orientation. Among the factors analyzed on a semantic differential instrument, differences between complexity and seriousness were found between the psychodynamic counselor and one who adheres to a rational-emotive approach. Psychodynamic counselors reported themselves as serious and intricate, contrasted to the rational-emotive group who viewed themselves as simple and humorous.

Cummings and Luchese (1978) postulated, “The emergence of an orientation is one given to the whims of fate” (p. 327), not choice, which Steiner (1978) identified as a direct result of one’s chosen graduate training and persuasive influence from professors and supervisors. Norcross and Prochaska (1983) disagree, arguing that it is foolish to think “clinicians select an orientation largely on inexplicable or accidental grounds” (p. 197). They questioned experienced psychologists, not graduate students, as to what factors fueled their theory selection. Among the various influences obtained via survey, clinical experience rated as the most influential. Other factors such as values, graduate training, postgraduate training, life experiences, internship, and the theory’s ability to help in self-discovery received strong ratings. Client type, orientations of colleagues, undergraduate training, and accidental circumstances received a weak or no influential rating.

Although client type was found less influential than other predictive factors (Norcross & Prochaska, 1983), researchers who support technical eclecticism argue otherwise, asserting that a client’s needs should determine a clinician’s orientation (Cheston, 2000; Erickson, 1993). Supporters of this approach encourage clinicians to consider adhering to methodologies that utilize specific empathic techniques that build greater rapport and subsequent growth in clients who conceptually do better with a particular interpersonal style (Bayne, 1995; Churchill & Bayne, 2001). Bayne (1995), for example, contends that if a client appears less innovative and more practical, then he or she should receive cognitive-behavioral counseling, rather than approaches that require creative expression. Extroverts, according to Bayne (1995), are more suitable for humanistic or insight-oriented approaches and group counseling, because they tend to be more sociable and talkative.

Assertiveness and Orientation

According to Gass and Seiter (2003), “Assertive people are not afraid to speak up, express their feelings, or take initiative” (p. 115). Assertive people are viewed as more socially influencing (Cialdini, 2001). In the clinical community, assertive people are sometimes defined by the amount of directiveness utilized in therapy. Kottler and Brown (2000) explain that directiveness involves one’s ability to influence an individual or family in such a way that they are motivated to make positive changes one goal at a time. They state that by taking initiative, setting limits, structuring sessions, and defending their suggestions, directive counselors are more likely to use their expert position for positive therapeutic gains. However, this does not mean that assertiveness equals directiveness, per se. No known research exists to validate that the two are parallel.

Although assertiveness on the part of the counselor is an influential factor in client growth and development, and essential for conflict resolution (Ramirez & Winer, 1983; Smaby & Tamminen, 1976), it has not been isolated or tested as an actual predictor for theoretical orientation. This study aims to add to the list of predictive factors that potentially contribute to the adoption of a theoretical orientation by examining whether an experienced counselor’s level of assertiveness relates to his or her chosen approach. Namely, whether passive counselors tend to adhere to more nondirective, insight-oriented theories, and if assertive counselors tend to adhere to more directive, action-oriented approaches.

Method

Participants

Thirty-five (N = 35) mental health professionals from two mid-south community mental health agencies participated in this study. Fifty packets containing each instrument were hand delivered to qualifying participants, resulting in a 70% response rate. Purposive sampling was used to ensure that respondents had at least two years of clinical experience, and to obtain enough participants from different experience levels. The reason experienced counselors were chosen is that they have had more time to practice different approaches and are more likely to have identified the orientation that best fits them, whereas “students are not capable of formulating a theory,” since “theories are developed by mature individuals on the basis of a thorough knowledge of existing theories and long experience” (Patterson, 1985, p. 349).

Participants had the following licenses: Clinical Psychologist (n = 1); Counseling Psychologist (n = 3); Psychological Examiner (n = 7); Social Worker (n = 12); and Professional Counselor (n = 13). There were 20 females and 15 males. Nineteen participants reported between 2–5 years of experience, while six reported having between 5–10 years of experience, and 10 reported having more than 10 years of experience. Sixteen participants reported adhering to an insight-oriented approach, and 19 were action-oriented. Each participant self-identified as Caucasian.

Instruments

Assertiveness Self-Report Inventory. The Assertiveness Self-Report Inventory (ASRI; Herzberger, Chan, & Katz, 1984) is a brief measure of behavioral assertiveness, developed intentionally with adequate validity data in mind. Other measures of assertiveness have been criticized for not reporting psychometric information (Corcoran, 2000). The instrument is a 25-item measurement with a forced-choice, true/false scale, with half of the items reverse scored to decrease the likelihood of a response set.

Herzberger et al. (1984) report high internal consistency with the ASRI (Cronbach’s Alpha = .78), strong test/retest reliability (r = .81, p < .001), and strong convergent validity with the Rathus Assertiveness Schedule (Rathus, 1973) during two testing sessions (r = .70, p < .001; r = .63, p < .001). For further validation, two criterion-related studies were conducted measuring participants’ ability to offer assertive-like solutions to social dilemmas and peer ratings of participants’ assertiveness. Both studies produced significant relationships to scores on the ASRI (r = .67, p < .001; r = .40, p < .005).

Bakker Assertiveness-Aggressiveness Inventory. The Bakker Assertiveness-Aggressiveness Inventory (AS-AG; Bakker, Bakker-Rabdau, & Breit, 1978) is a 36-item inventory that measures two dimensions of assertiveness necessary for social functioning: the ability to refuse unreasonable requests (Assertiveness) and the ability to take initiative, make requests, or ask for favors (Aggressiveness), with both scales available for use as separate 18-item instruments (Corcoran, 2000). Each item provides the reader with a specific conflict situation and a specific behavioral response, and asks examinees to rate the likelihood that they would respond in the same manner. Half the items contain an assertive response, whereas the other half contains more passive, submissive responses (Bakker et al., 1978). Each item is scored on a five-point likert scale ranging from almost always (AA = 1) to almost never (AN = 5).

Normative data were collected from seven groups, including health professionals, city employees, college students, and clients of an adult development program seeking assertiveness training. Test-retest reliability data are strong for both scales: .75 for the assertiveness scale and .88 for the aggressiveness scale, and split-half reliability of .58 and .67 for both scales, respectively (Bakker et al., 1978). Validity measures were obtained by comparing each group with the college sample, since it was the largest (n = 250). The only group to significantly differ in assertiveness/aggressiveness was the adult development program clients (p < .001), confirming “that the scales are sensitive to differences in functioning” (Bakker et al., p. 282).

The Simple Rathus Assertiveness Schedule. The Simple Rathus Assertiveness Schedule (SRAS; McCormick, 1985) is a revised measure of the Rathus Assertiveness Schedule (Rathus, 1973) designed to improve the original measure’s readability and usability (Corcoran, 2000). A 30-item instrument, the schedule measures social boldness by asking readers to rate themselves on various personal inclinations, such as I enjoy meeting and talking to people for the first time and I have sometimes not asked questions for fear of sounding stupid (McCormick, 1985). Items are scored on a six-point Likert scale, ranging from 6 (very much like me) to 1 (very unlike me).

Reliability for the SRAS is “very good” (Corcoran, 2000, p. 746) when compared with the original Rathus, with the correlation between odd and even items on both versions at .90, and overall total scores correlating at .94, suggesting that “a satisfactory degree of equivalence had been obtained between both measures” (McCormick, 1985, p. 97). The original Rathus reported test/retest reliabilities of .77 (p < .01) and strong convergent validity with other measures of assertiveness.

Procedure

Participants were placed in one of two groups based on their reported theoretical orientation, which Kottler and Brown (2000) categorized as insight-oriented and action-oriented. Insight-oriented approaches believe that self-discovery and revelation is the path to true growth and consists of humanistic, psychodynamic, interpersonal, and experiential theories. Action-oriented approaches are defined as theories that utilize direct interventions and action for symptom reduction. Theories within this category are behavioral, cognitive, strategic, and solution-focused in nature.

Both groups completed an assessment packet, consisting of an informed consent form, a demographic sheet, and the three measurements of assertiveness. Presentation of instruments was identical in both groups. Scores were totaled and compared between each group. Consent forms were kept separate to ensure confidentiality of the information.

Results

A Pearson product-moment correlation analyzed the relationship between all three assertiveness instruments to investigate convergent validity. This analysis revealed a significant positive correlation between the ASRI and SRAS (r = .78, p < .0001) between the ASAG and SRAS (r = .56, p = .0017) and between the ASRI and ASAG (r = .51, p = .0004). The nature of the correlation coefficients indicates a strong convergent validity between all three instruments.

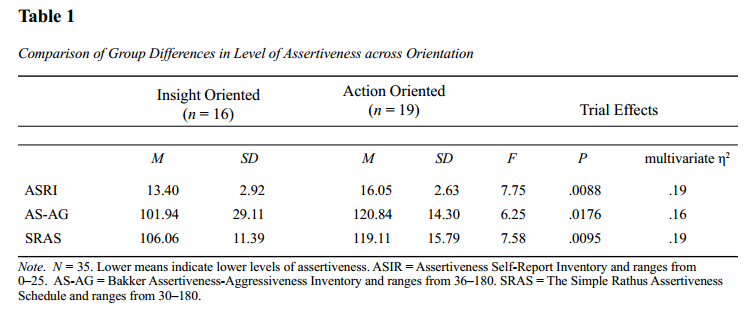

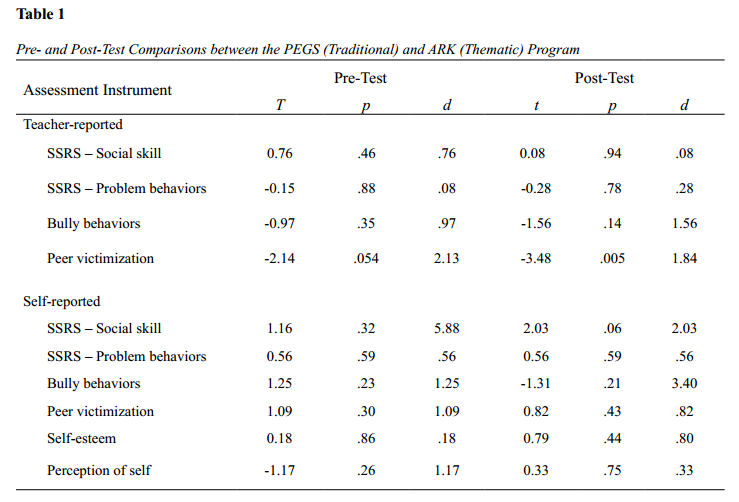

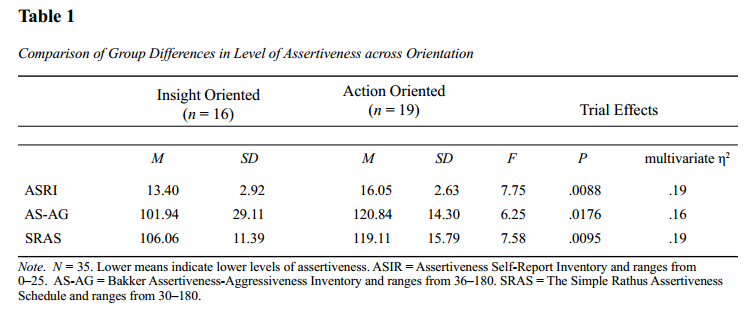

Data were analyzed via a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) in order to find differences between insight-oriented and action-oriented counselors on three assertiveness instruments. Additionally, effect sizes are reported as small ≥ .02, medium ≥ .13, and large ≥ .26 (see Steyn & Ellis, 2010). Sample means and trial effects are presented in Table 1. The ANOVA on the ASRI revealed a significant difference between each group: F(1, 33) = 7.75, MSE = 7.66, p < .0088. The mean score for the insight-oriented group was 13.40 (SD = 2.92), and the mean for the action-oriented group was 16.05 (SD = 2.63). The multivariate effect size η2 = .19 indicates a moderate relationship between theoretical orientation and participant assertiveness.

Next, the ANOVA on the AS-AG revealed a significant difference between each group: F(1, 33) = 6.25, MSE = 496.53, p < .0176. The mean score for the insight-oriented group was 101.94 (SD = 29.11), and the mean for the action-oriented group was 120.84 (SD = 14.30). The multivariate effect size η2 = .16 indicates a moderate relationship between theoretical orientation and participant assertiveness.

Finally, the results of the ANOVA on the SRAS revealed a significant difference between each group: F(1, 33) = 7.58, MSE = 195.05, p < .0095. The mean score for the insight-oriented group was 106.06 (SD = 11.39), and the mean for the action-oriented group was 119.11 (SD = 15.79). The multivariate effect size η2 = .19 indicates a moderate relationship between theoretical orientation and participant assertiveness.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine if passive counselors tend to adhere to more nondirective, insight-oriented theories, and if assertive counselors tend to adhere to more directive, action-oriented approaches. Data from scores on the Assertiveness Self-Report Inventory, the Bakker Assertiveness-Aggressiveness Inventory, and the Simple Rathus Assertiveness Schedule suggest that a significant difference does exist between insight-oriented and action-oriented counselors on level of assertiveness, suggesting that level of assertiveness in mental health professionals is a viable factor in theoretical orientation development. In fact, action-oriented counselors had significantly higher levels of assertiveness than the insight-oriented counselors did across all three measures, with the variability of the scores on the AS-AG indicating substantial differences between the two orientations. Not surprisingly, the results on all three measures were in the same direction, consistent with the convergent validity of the measures.

Effect size analyses indicate that moderate relationships exist between theoretical orientation and participant assertiveness, which are clinically meaningful and of practical significance in addition to statistical significance (LeCroy & Krysik, 2007). This finding supports Kottler and Brown’s (2000) position on the nature and quality of directiveness in the therapeutic relationship. That is how assertiveness on the part of the counselor can be an influential factor in client growth and development. This suggests that possibly the two may in fact be parallel. Nonetheless, according to the results, counselors that choose directive approaches appear to be assertive themselves.

Previous research has investigated several predictive factors that contribute to the adoption of a theoretical orientation by counselors (Bayne, 1995; Erickson, 1993; Freeman, 2003; Johnson et al., 1988; Murdock et al., 1998; Norcross & Prochaska, 1983; Steiner, 1978; Walton, 1978). No one study, however, has been able to identify each factor interdependently, opting to isolate specific factors independently via multiple examinations. This study aimed to add to the established list of identified predictive factors by examining whether an experienced counselor’s level of assertiveness relates to his or her chosen approach. We believe that we can now add assertiveness to the list of predictive factors, which include personality type, therapist training, age of clients, and level of counselor development. A limitation in this study was the ability to generalize to different races. All mental health professionals that participated were Caucasian. Another possible limitation was that the participants self-reported on their theoretical orientation.

Implications and Conclusions

The counseling profession benefits from research designed to identify the predictive factors leading to one’s choice of a theoretical orientation. Graduate programs, for example, could use the current data to facilitate the process of theory formation and adoption, including theoretical integration and technical eclecticism, in addition to general instruction that covers the history of theory and the art of the therapeutic relationship. Supervisors of beginning clinicians might profit, not only in facilitating a supervisee’s development of professionalism, but by assisting them to re-examine their strengths and limitations, which may lead to an investigation into new theoretical possibilities that create a better “clinical fit.” Even agencies, conceivably, could utilize the predictors in an attempt to match a client to a particular counselor based on theory and personality. Although this may not seem practical, such an effort could be a positive ingredient for increasing community outcome measures and reducing counselor burnout. Further research supporting this idea would be beneficial. Conversely, further research is necessary to investigate whether matching a counselor’s personality to a theoretical orientation is actually empirically effective. This study is limited by the fact that it does not provide support for such a hypothesis, but does support its consideration.

Although the list of predictive factors leading to a counselor’s choice of orientation is extensive and complex, and no study has been able to identify them in their entirety, it does not mean that isolating the factors for clinical research is meaningless. On the contrary, identifying the predictive factors is advantageous. Doing so could make theory adoption more counselor-centered and satisfying to the adopting practitioner, who can choose an approach that “fits” best.

References

Bakker, C. B., Bakker-Rabdau, M. K., & Breit, S. (1978). The measurement of assertiveness and aggressiveness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 42(3), 277–284.

Bayne, R. (1995). Psychological type and counselling. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 23(1), 95–106.

Cheston, S. E. (2000). A new paradigm for teaching counseling theory and practice. Counselor Education and Supervision, 39(4), 254–270.

Churchill, S., & Bayne, R. (2001). Psychological type and conceptions of empathy in experienced counsellors: Qualitative results. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 14(3), 203–217.

Cialdini, R. B. (2001). Influence: Science and practice (4th ed.). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Corcoran, K. J. (2000). Measures for clinical practice: A sourcebook. New York: Free Press.

Corey, G. (2008). Theory and practice of counseling and psychotherapy (8th ed.). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Corsini, R. J., & Wedding, D. (2008). Current psychotherapies (8th ed.). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Cummings, N. A., & Luchese, G. (1978). Adoption of a psychological orientation: The role of the inadvertent. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, and Practice, 15, 375–381.

Erickson, D. B. (1993). The relationship between personality type and preferred counseling model. Journal of Psychological Type, 27, 39–41.

Freeman, M. S. (2003). Personality traits as predictors of a preferred theoretical orientation in beginning counselor education students. Dissertation Abstracts International, 64(02), 407B.

Gass, R. H., & Seiter, J. S. (2003). Persuasion, social influence, and compliance gaining (2nd ed.). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Halbur, D. A., & Halbur, K. V. (2005). Developing your theoretical orientation in counseling and psychotherapy. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Heppner, P. P., Kivlighan, Jr., D. M., & Wampold, B. E. (1999). Research design in counseling (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Herzberger, S. D., Chan, E., & Katz, J. (1984). The development of an assertiveness self-report inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment, 48(3), 317–323.

Johnson, J. A., Germer, C. K., Efran, J. S., & Overton, W. F. (1988). Personality as the basis for theoretical predilections. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55(5), 824–835.

Kottler, J. A., & Brown, R. W. (2000). Introduction to therapeutic counseling: Voices from the field (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

LeCroy, C. W., & Krysik, J. (2007). Understanding and interpreting effect size measures. Social Work Research, 31(4), 223–248.

MacCluskie, K. (2010). Acquiring counseling skills: Integrating theory, multiculturalism, and self-awareness. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

McCormick, I. A. (1985). A simple version of the Rathus assertiveness schedule. Behavioral Assessment, 7, 95–99.

Murdock, N. L., Banta, J., Stromseth, J., Viene, D., & Brown, T. M. (1998). Joining the club: Factors related to choice of theoretical orientation. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 11(1), 63–78. doi:10.1080/09515079808254043

Norcross, J. C., & Prochaska, J. O. (1983). Clinicians’ theoretical orientations: Selection, utilization, and efficacy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 14(2), 197– 207.

Patterson, C. H. (1985). New light for counseling theory. Journal of Counseling and Development, 63(6), 349–350.

Ramirez, J., & Winer, J. L. (1983). Counselor assertiveness and therapeutic effectiveness in treating depression. The Personnel and Guidance Journal, 62(3), 167–170.

Rathus, S. A. (1973). A 30-item schedule for assessing assertive behavior. Behavior Therapy, 4, 398–406.

Scragg, P., Bor, R., & Watts, M. (1999). The influence of personality and theoretical models on applicants to a counseling psychology course: A preliminary study. Counseling Psychology Quarterly, 12(3), 263–270.

Smaby, M. H., & Tamminen, A. W. (1976). Counselors can be assertive. Personnel and Guidance Journal, 54(8), 421–424.

Steiner, G. L. (1978). A survey to identify factors in therapists’ selection of a theoretical orientation. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, and Practice, 15(4), 371–374.

Steyn, H. S., Jr., & Ellis, S. M. (2010). Estimating an effect size in one-way multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). Multivariate Behavioral Research, 44(1), 106–129. doi:10.1080/00273170802620238

Walton, D. E. (1978). An exploratory study: Personality factors and theoretical orientations of therapists. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, and Practice, 15(4), 390–395.

Michael Lee Powell is a Licensed Professional Counselor and Licensed Alcoholism and Drug Abuse Counselor at Youth Bridge, Inc. in Fayetteville, AR, and Rebecca A. Newgent, NCC, is a Licensed Professional Clinical Counselor with Supervision Designation in Ohio, a Licensed Professional Counselor with Supervision Specialization in Arkansas, and Professor and Chairperson at Western Illinois University – Quad Cities. Correspondence can be addressed to Michael Lee Powell, 4257 Gabel Drive, Fayetteville, AR, 72703, dr.michael.powell@gmail.com.

Sep 5, 2014 | Article, Volume 1 - Issue 2

Michelle Perepiczka, Nichelle Chandler, Michael Becerra

Statistics plays an integral role in graduate programs. However, numerous intra- and interpersonal factors may lead to successful completion of needed coursework in this area. The authors examined the extent of the relationship between self-efficacy to learn statistics and statistics anxiety, attitude towards statistics, and social support of 166 graduate students enrolled in master’s and doctoral programs within colleges of education. Results indicated that statistics anxiety and attitude towards statistics were statistically significant predictors of self-efficacy to learn statistics, yet social support was not a statistically significant predictor of self-efficacy. Insight into how this population responds to statistics courses and implications for educators as well as students are presented.

Keywords: graduate students, statistics, anxiety, self-efficacy, attitudes, social support

More graduate programs in various social science fields are requiring students to complete research methods including statistics courses or a blended combination thereof (Davis, 2003; Schau, Stevens, Dauphinee, & Del Vecchio, 1995). These course requirements pose a dilemma for educators and students because many students perceive statistics as difficult and unpleasant (Berk & Nanda, 1998). Some students can struggle in statistics courses as a related complication of this perception as well as other intrapersonal factors related to the course.

To investigate graduate students’ experiences in statistics courses, researchers studied different avenues to understand what occurs with students so steps can be taken to improve learning as well as satisfaction in college statistics courses. For instance, researchers suggested non-cognitive factors such as motivation for further learning (Gal & Ginsburg, 1994; Finney & Schraw, 2003), statistics self-efficacy (Onwuegbuzie & Wilson, 2003), and attitude toward statistics (Araki & Schultz, 1995; Elmore, Lewis, & Bay, 1993; Waters, Martelli, Zakrajsek & Popovich, 1988; Wise, 1985) should be assessed and addressed with students. Finney and Schraw theorized that the difficulty students experience with statistics is not necessarily due to lack of intelligence or poor aptitude, but may be a result of the above mentioned factors. Bonilla (1997), Cohen and McKay (1984), and Solberg and Villarreal (1997) hypothesized that social support may act as a buffer against the development of these psychological manifestations.

The purpose of this study was to examine the various factors that have been introduced in previous research in one comprehensive study. The goal was to determine how graduate student self-efficacy to learn statistics is predicted by statistics anxiety, attitude toward statistics, and social support (Gall, Gall, & Borg, 2007). The overarching intent was to document graduate student self-efficacy to learn statistics and identify how certain variables influence statistics self-efficacy (Pan & Tang, 2005).

Self-Efficacy to Learn Statistics

In order to understand the implications of this research, an explanation of the key variables found in the literature review must first be discussed. Self-efficacy to learn statistics is the dependent variable in this study. Bandura (1977) originally defined general self-efficacy as one’s judgments of his or her capabilities to organize and carry out courses of action required to attain specific types of performances. Bandura asserted that self-efficacy beliefs are manifested from four primary sources, which include the following: (a) personal accomplishments, (b) vicarious learning experiences, (c) verbal persuasion, and (d) emotional arousal. These primary sources lay the foundation for building the concept of self-efficacy to learn statistics. Finney and Schraw (2003) defined self-efficacy to learn statistics and developed an assessment to measure this phenomenon. Self-efficacy to learn statistics is an individual’s confidence in his or her ability to successfully learn statistical skills necessary in a statistics course.

A large amount of information is available on self-efficacy related to academic performance (Lent, Brown, & Larkin, 1984, 1986; Pajares, 1996; Pajares & Miller, 1995; Zimmerman, 2000; Zimmerman, Bandura, & Martin-Pons, 1992). However, little is known specifically about self-efficacy to learn statistics. Finney and Schraw (2003) investigated whether self-efficacy to learn statistics is related to performance in a statistics course and whether self-efficacy to learn statistics increased during a 12-week introductory statistics course. One hundred and three undergraduate students from a large Midwestern university participated in the survey. Finney and Schraw reported a positive relationship between statistics self-efficacy and academic performance as well as an increase in self-efficacy to learn statistics over the duration of the course. Onwuegbuzie (2000) also reported students with the lowest levels of perceived competence had the highest levels of statistics anxiety. Additionally, Pajares and Miller (1995) documented an inverse relationship between self-efficacy and math anxiety.

Statistics Anxiety

Statistics anxiety is one of the three independent variables in this study. Researchers have documented a large amount of information on statistics anxiety over the years. For instance, there are multiple definitions of statistics anxiety available in the literature. Onwuegbuzie, DaRos, and Ryan (1997) defined statistics anxiety as “a state-anxiety reaction to any situation in which a student is confronted with statistics in any form and at any time” (p. 28). Cruise, Cash, and Bolton (1985) defined statistics anxiety as “the feelings of anxiety encountered when taking a statistics course or doing statistical analyses: that is, gathering, processing, and interpret[ing]” (p. 92). The latter is the definition utilized for this study.

We know that instructors of research and statistics courses often encounter students with high levels of statistics anxiety upon their arrival to class (Perney & Ravid, 1991). According to Onwuegbuzie, Slate, Paterson, Watson, and Schwartz (2000), 75% to 80% of graduate students in the social sciences appeared to experience high levels of statistics anxiety. Statistics anxiety was found to be higher among female and minority graduate students in comparison to their male and Caucasian counterparts (Onwuegbuzie, 1999; Zeidner, 1991).

Researchers identified three categories of variables—situational, dispositional, and environmental—that are related to statistics anxiety (Onwuegbuzie & Wilson, 2003). Situational antecedents are factors that surround the student, including previous statistics experiences (Sutarso, 1992). Researchers found a negative connection between the number of completed mathematics courses and statistics anxiety (Auzmendi, 1991; Robert & Saxe, 1982; Zeidner, 1991). Forte (1995) found minimal previous math experience, late introduction to quantitative analysis, anti-quantitative bias, lack of appropriation for the significance of analytical models, and lack of mental imagery were factors contributing to statistics anxiety among social work students.

Dispositional antecedents are intrapersonal factors students bring to the classroom (Onwuegbuzie & Daly, 1999), which includes issues such as perfectionism and perception of abilities at developmental stages in life (Pan & Tang, 2004). Walsh and Ugumba-Agwunobi (2002) found evaluation concern, fear of failure, and perfectionism provoked statistics anxiety. Environmental antecedents are interpersonal factors related to the classroom experience (Onwuegbuzie & Daly, 1999), which can include the student’s experiences with the professor. Tomazie and Katz (1988) reported previous experiences in statistics courses have influenced learning in a current course. Moreover, the environmental antecedent has the least research available in the literature.

Attitude Toward Statistics

Attitude toward statistics is the second independent variable in this study. Attitude towards statistics is defined in this study as a combination of a students’ attitude toward the use of statistics in their field of study and the students’ attitudes towards the statistics course (Cashin & Elmore, 1997; Wise, 1985). Researchers explored this area; however, there are many gaps left to fulfill. Gal and Gingsburg (1994) reported students often enter statistics courses with negative views or later develop negative feelings regarding the subject matter of statistics. Researchers found no statistically significant differences among females’ and males’ attitudes towards statistics (Araki & Schultz, 1995; Cashin & Elmore, 2005; Harvey, Plake, & Wise, 1985). However, conflictingly, Waters et al. (1988) and Roberts and Saxe (1982) found male students had more positive attitudes towards statistics than female students.

According to Perney and Ravid (1991), statistics courses are viewed by most college students as a road block to obtaining their degree. Students often delay taking their statistic courses until the end of their program. Researchers found students’ negative attitudes toward statistics is an influencing factor in low student performance in statistics courses (Araki & Schultz, 1995; Elmore et al., 1993; Harvey et al., 1985; Schulz & Koshino, 1998; Robert & Saxe, 1982; Waters et al., 1988; Wise, 1985).

Perceived Social Support

Perceived social support is the final independent variable in this study. Perceived social support for this study is defined as the level of support an individual self identifies as received from friends, family, and significant others (Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, & Farley, 1988). This variable is influential in this study in terms of the potential buffering effect it may have on the other independent variables, statistics anxiety and attitude towards statistics.

According to Bonilla (1997), social support acts as a buffer to dysfunctional thoughts or attitudes. In 1985, Cohen and Wills investigated the process through which social support has a beneficial effect on well-being. The buffering model maintains that support is related to well-being primarily for persons under stress. Cohen and Wills identified four support resources, which include the following: (a) esteem support such as the person is valued and accepted, (b) informational support, (c) social companionship such as engaging in leisurely activities with others, and (d) instrumental support such as an individual providing a person with financial aid, material resources, or need-based services.

Solberg and Villarreal (1997) conducted a study to explore the interactions between social support and physical as well as psychological distress of Latino college students. The authors reported social support moderated the distress. Specifically, the Latino students who believed social support was available had lower psychological distress than students who believed that social support was less accessible.

Research Questions

Six research questions were included in this study. The first four focus on descriptive information from our sample and include the following: (a) what is the graduate student self-efficacy level, (b) what is the graduate student statistics anxiety level, (c) what is the graduate student attitude toward statistics, and (d) what is the graduate student level of perceived social support? The predominate research question driving this study is, what is the extent of the relationship, if any, between graduate students’ self-efficacy to learn statistics and statistics anxiety, attitude towards statistics, and social support? A supplemental research question was, what is the influence of social support on statistics anxiety and attitude towards statistics?

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited by the researcher emailing faculty members of doctoral and master’s programs within colleges of education at 250 universities within the United States. The faculty members were asked to forward information about the opportunity to participate in the study to their students. One hundred sixty-six graduate students within colleges of education representing 27 states fully completed the online survey within the 8-week data collection timeframe. An a priori power analysis was conducted considering involvement of three predictors in the multiple regression equation and estimating a moderate effect size based on similar studies. It was determined that 119 participants are needed to achieve adequate power in the study (Faul, 2006); thus, an appropriate sample size was achieved to obtain adequate power in the analysis (Gall et al., 2007).

The sample was predominately female (N = 136, 81.9%) compared to males (N = 30, 18.1%). Participants’ age ranged from 21 to 71 with 34.4 as the mean age. The cultural makeup of the sample consisted of 4 Native American (2.4%), 4 Asian/Pacific Islander (2.4%), 24 African American (14.5%), 124 Caucasian (74.7%), and 10 Latino participants (6%).

The academic level of the participants was close to evenly split with 92 master’s students (55.4%) and 74 doctoral students (44.5%). The majority of the sample (N = 144, 86.7%) were enrolled in counseling or related educational programs such as mental health counseling, school counseling, rehabilitation counseling, student affairs, and counselor education and supervision. Twenty-two (13.3%) participants were enrolled in education graduate programs such as educational leadership, curriculum and instruction, and educational technology. One hundred thirty-six participants (81.9%) were enrolled in programs that were accredited by at least one accreditation body appropriate to their program.

Participants had different backgrounds in terms of taking statistics courses. The mean number of completed graduate statistics classes at the time of participating in the study was 1.63 classes for the sample. The range of courses was 0 to 6, and the mode was 0 classes with 45 participants (27.1%) not having completed a single graduate level statistics course. Of the 121 who completed a statistics course previously, the mean final grade was 89.34% with the lowest grade earned reported as 70%.

Instruments

A demographic questionnaire was used to collect information related to participants’ personal characteristics as well as previous experiences with graduate statistics classes. The Self-Efficacy to Learn Statistics (SELS) scale was used to measure the dependent variable (Finney & Schraw, 2003). The SELS measures confidence in one’s ability to learn necessary statistics while in a statistics course in order to successfully complete 14 specific tasks using a 1 (no confidence at all) to a 6 (complete confidence) response scale. Only a total score is obtained from the instrument. Internal consistency reliability was reported as .975 Cronbach’s alpha. Validity evidence of SELS to other variables was reported. The SELS was positively correlated with the Math Self-Efficacy scale and negatively correlated to the general and statistics Test Anxiety Inventory subscale providing evidence of concurrent validity. The norm group for the instrument was a total of 154 college students enrolled in an introductory statistical methods course.

The Statistics Anxiety Rating Scale (STAR) was used to measure the independent variable statistics anxiety (Baloglu, 2002; Cruise &Wilkins, 1980). The assessment is a 51-item Likert scale ranging from 1 (no anxiety) to 5 (very much anxiety) and measures anxiety in two parts. The first part includes 23 statements related to statistics anxiety and the second part has 28 items related to dealing with statistics. A total score as well as six subscores including the following are generated with this instrument: Worth of Statistics, Interpretation Anxiety, Test and Class Anxiety, Computation Self-Concept, Fear of Asking for Help, and Fear of Statistics Teacher. Reliability for each of the subscales ranged between .68 to .94 with a median of .88 (Worth of Statistics .94, Interpretation Anxiety .87, Test and Class Anxiety .69, Computational Self-Concept .88, Fear of Asking for Help .89, and Fear of Statistics Teachers .80). Validity evidence of STARS to other variables was reported. The STARS had a strong correlation (r = .76) to the Math Anxiety Scale (Roberts & Bilderback, 1980). The instrument was normed with 1,150 university students enrolled in statistics courses.

The independent variable, attitude toward statistics, was measured by the Attitude Toward Statistics (ATS) scale (Schultz & Koshino, 1998). This is a 29 item, 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. A total score and two subscale scores, Attitudes Toward the Field and Attitudes Toward the Course, are obtained from the instrument. Both subscales were reported as reliable with Cronbach’s alpha at .92 for Attitudes Toward the Field and .91 for Attitudes Toward the Course (Wise, 1985). The ATS was reported to have strong concurrent validity with the Statistics Attitude Survey. The norm group consisted of 162 university students enrolled in an introductory educational statistics course.

The third independent variable, social support, was measured by the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) (Zimet, Powell, Farley, Werkman, & Berkoff, 1990). The instrument has 12 items and utilized a 7-point Likert scale ranging from very strongly disagree to very strongly agree. A total score and three subscale scores (support from significant others, support from family, and support from friends) were obtained. The instrument was reported as reliable with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients reported as .85 to .91 for the three subscales. Test-retest values ranges from .72 to .85. Zimet et al. reported significant correlations between the MSPSS subscales and the Depression and Anxiety subscales of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist as evidence of construct validity for their instrument. The norm group consisted for 275 university students at Duke University.

Data Analysis

A simultaneous multiple regression was analyzed to determine the extent of the relationship between graduate students’ self-efficacy to learn statistics and statistics anxiety, attitude towards statistics, and social support. Alpha level was set at .05 for the analysis and semipartial correlation coefficients were assessed for practical significance. The multiple regression was repeated, removing social support from the analysis to explore any moderating effects of social support on the model.

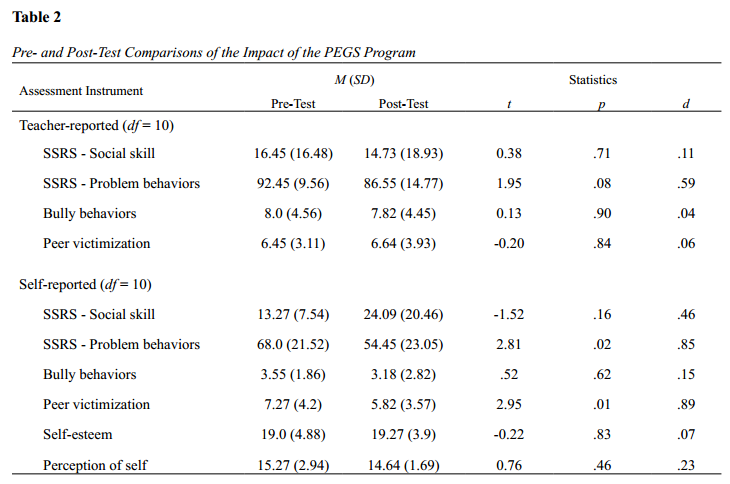

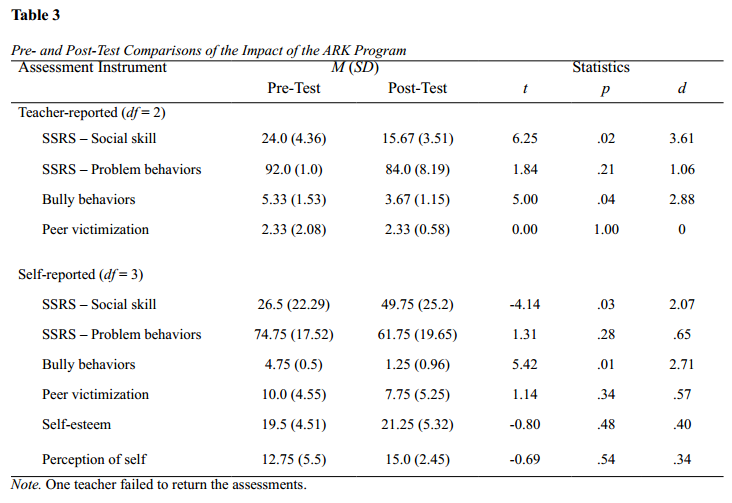

Results

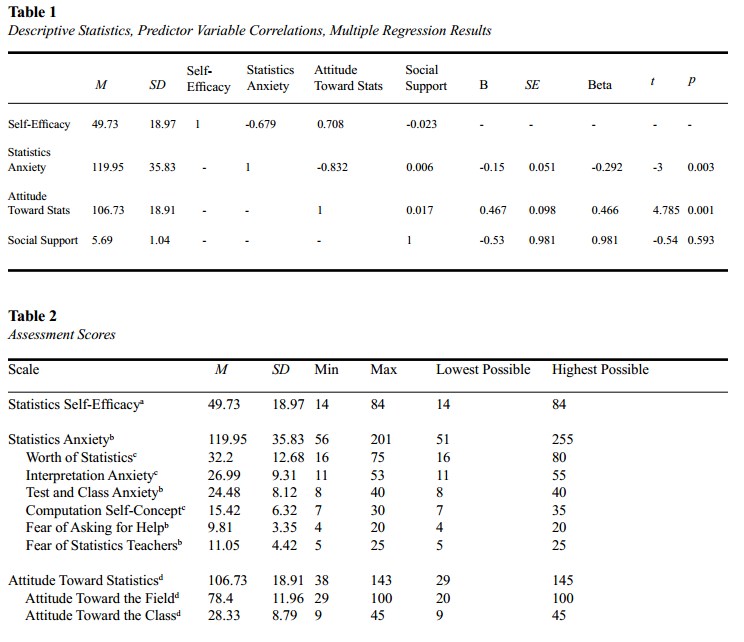

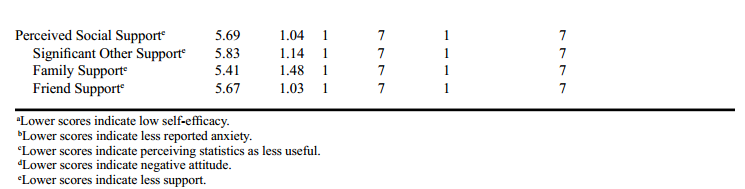

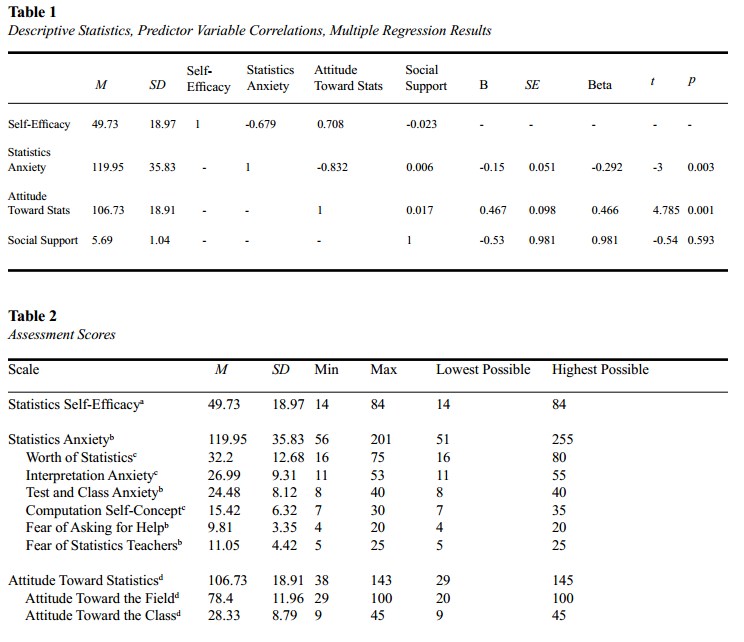

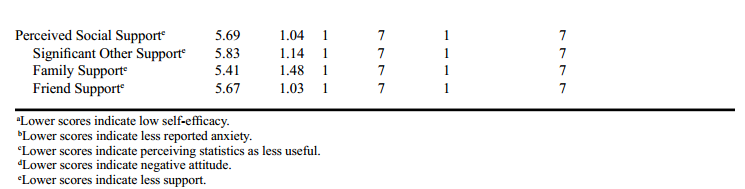

Descriptive statistics of the sample data are displayed in Table 1 and sample scores for the assessments with a comparison to the maximum and minimum scores for the instruments are included in Table 2. Self-efficacy to learn statistics scores were normally distributed (SW(173) = .986, p = .076) and the box plot for the criterion variable confirmed normality as well. Standardized residuals also were normally distributed (SW(173) = .988, p = .159) and the box plot for the standardized residuals and scatterplots confirmed normality of the error variance or homoscedasticity. Scatterplots were analyzed for linearity, and it was determined no curvilinear relationships between the criterion variable and predictor variables were evident. Statistics anxiety and attitude towards statistics were highly correlated (-0.83), indicating multicollinearity.

There was a statistically significant relationship between self-efficacy to learn statistics and statistics anxiety, attitude towards statistics, and social support: F(3, 162) = 60.489, p < .001. A moderate effect size was noted with 52.8% of the variance accounted for in the model, R2 = .528. Statistics anxiety and attitude towards statistics were statistically significant predictors of self-efficacy to learn statistics and accounted for 3% and 7% of the variance, respectively. Social support was not a statistically significant predictor of self-efficacy to learn statistics and accounted for .1% of the variance. When social support was removed from the analysis, there was no change in statistical or practical significance.

Discussion

This study sought to explore the relationships of graduate students’ self-efficacy to learn statistics, statistical anxiety, attitudes towards statistics, and social support. The scores from the various instruments identifying each of the aforementioned variables produced both negative and positive correlations among each other. A statistically significant relationship was found among self-efficacy and statistical anxiety, attitudes towards statistics and social support indicating the importance of the graduate students’ belief in their competence of facing the challenges of learning statistics. However, there was no change in the relationship when social support was removed from the analysis; thus, it was not a contributing variable. Statistics self-efficacy scores from participants indicated moderate responses which mirrored the prior studies involving undergraduate students (Pajares, 1996; Zimmerman, 2000). As this was the first study that investigated graduate students, these results create a path for future research.

There was a negative correlation between self-efficacy to learn statistics and statistical anxiety of the graduate students. The negative correlation is consistent with Onwuegbuzie’s (2000) findings. Participants reported the lowest responses in the Fear of Asking for Help and Worth of Statistics subscales, signaling graduate students reluctance for asking for assistance from the professor and peers as well as a low belief in the applicability and purpose of statistics. Overall, these results and the negative correlation between self-efficacy and anxiety seem to depict a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy that graduate students assume when faced with taking statistics which is similar to Perney and Ravid’s (1991) report.

A positive correlation was found between self-efficacy to learn statistics and attitudes towards statistics. This results indicated that the better the attitude of the graduate students towards statistics, the higher self-efficacy beliefs to learn the subject. Results indicated a more moderate response to attitudes not found in other studies where students were coming in with a negative attitude or were developing negative attitudes towards the end of the course (Gal & Gingsburg, 1994). It may be considered that graduate students in this study were neutral in their attitudes towards learning statistics without extreme reactions.

Participants reported a high level of social support, which indicates that most of the graduate students believed they had adequate support. The sample perceived social support as an influential factor in their lives, which is similar to most college student population reports (Solberg & Villarreal, 1997). However, social support was not a statistically significant predictor of self-efficacy to learn statistics. Also, when this variable was removed from the multiple regression analysis, there was no statistical or practical change in the regression. The insignificant result implies that social support was present for students, but it did not interact as a buffer between variables and possibly decrease anxiety or increase positive attitudes as indicated by Bonilla (1997), Cohen and McKay (1984), and Solberg and Villarreal (1997). Thus, social support may possibly help one cope but not necessarily remove the problem, change attitudes, or change thinking.

Multicollinearity between statistics anxiety and attitude toward statistics suggests an interrelationship between the two variables (Gall et al., 2007). Both variables may be measuring the relatively same characteristic; thus, neither variable may have brought something completely new to the analysis. It is interesting to note that statistics anxiety and attitude toward statistics as measured by the instruments in this particular study may be focusing on the same phenomenon.

Significance

There were multiple benefits of this study. First, this study contributed to counselor education and student support services by increasing our knowledge of self-efficacy to learn statistics as experienced by graduate students. It also is significant because it documented students’ experiences, which may act as a spring board for (a) future research, (b) implementing support interventions to increase statistics self-efficacy or success in statistics courses, and (c) helping students prepare for intrapersonal challenges that might impact their success in statistics. Each of these improvements are beneficial because they may increase graduate student self-efficacy and success in statistics courses as well as increase the incorporation of statistics into professional work after graduation.

Recommendations for Counselor Educators

Decreasing anxiety among graduate students is vital to developing high levels of self-efficacy towards statistics. Implementing numerous opportunities for students to engage in research throughout their graduate studies allows for opportunities to be exposed to statistics, thus increasing students’ confidence when faced with taking a statistics course. Also, inserting research and statistics into the curriculum of every graduate course exposes graduate students to the terminology and the function statistics play in their development as professionals. Possible ways to decrease statistical anxiety are through language and experience. Allowing graduate students to learn what is being said in a statistics course through weekly vocabulary tests can be one example of decreasing their anxiety. Also, getting the students involved with their own research throughout their course of study will help in promoting statistics mastery.

Improving attitudes towards statistics can help graduate students reframe their negative views towards the course. Helping graduate students to choose a positive view, explore origins or core of negative attitudes, and to appreciate the usefulness of statistics in their profession are good starting points for developing salient attitudes towards the subject. Counselor educators in a position to help graduate students confront negative attitudes, model positive attitudes and enthusiasm for statistics, and place a high value on statistics through verbal support and high expectations of research and statistics for students in graduate programs. The professor teaching statistics can play a key role in positively impacting their students’ attitude toward the subject. Injecting humor, displaying empathy, providing a safe space for students to talk about their challenges, and celebrating their small successes can be tools in combating negative attitudes. Anecdotal stories of statistics professors engaging in statistical rap songs have been reported to successfully alleviate attitudes towards the subject as well as provide a positive environment to engage in learning.

Limitations of the Study

There were limitations to this study. For instance, graduate students in counseling and education related programs were recruited for the study; thus, due to the general nature of the population, there were a disproportionate number of females and Caucasian students in the sample. As a result, a diverse sample was not obtained. However, a representative sample was acquired. Also, there were four scales for participants to answer in the study, therefore putting a time constraint burden on students to finish the instruments. Finally, these instruments were self-reporting, which can promote bias in how the graduate students answered (Gall et al., 2007).

Suggestions for Future Research

Future research should expand investigations into statistics self-efficacy predictor variables that include number of statistics courses taken, previous statistics experience, and broad demographics of graduate students to include more participants representing the various races and ethnicities, marital status, and life experiences. Longitudinal studies to monitor how statistics self-efficacy changes for graduate students over time would provide a snapshot of the development of attitudes throughout their graduate study tenure. Experimental designs to assess classroom and counseling based intervention effectiveness in reducing anxiety and improving attitudes should be conducted to improve the reliability of students learning statistics and influence the participation of conducting their own research for the betterment of the counseling profession. Finally, qualitative studies need to be conducted to better capture students’ experiences in statistics classes.

Conclusion

Researching predictors of graduate students’ statistical self-efficacy beliefs is important to identifying possible barriers to professional growth and development. Exploring how statistical self-efficacy beliefs relate to predicting future academic expectations, performance, effort, persistence, and course selection (Pajares, 1996; Zimmerman, 2000) also is important to explore as a means of promoting professional development (Lent et al., 1984, 1986).

Graduate students who believed they were incapable of achieving success in a statistics course demonstrated higher levels of anxiety (Onwuegbuzie, 2000). This anxiety was pervasive among the 75% to 80% of graduate students in the social sciences profession in previous research studies (Onwuegbuzie et al., 2000), as well as to the 53% of the graduate students in this study. Additionally, graduate students hold off from taking a statistics course due to their negative attitudes towards the subject matter (Gal & Gingsburg, 1994). Teaching graduate students how to reduce their anxiety and improve their attitude will likely enhance their value of statistics and further encourage their professional development in the counseling profession.

References

Araki, L. T., & Shultz, K. S. (1995, April). Students attitudes toward statistics and their retention of statistical concepts. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Western Psychological Association, Los Angeles.

Auzmendi, E. (1991, April). Factors related to attitudes toward statistics: A study with a Spanish sample. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Chicago, IL.

Baloglu, M. (2002). Psychometric properties of the statistics anxiety rating scale. Psychological Reports, 90, 315–325.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavior change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–251.

Berk, R. A. & Nanda, J. P. (1998). Effects of jocular instructional methods on attitudes, anxiety, and achievement in statistics courses. International Journal of Humor Research, 11, 383–409.

Bonilla, J. (1997). Vulnerabilidad a la intomatologia depresiva: Variables personales, cognoscitivas y contextuales. Manuscrito sin publicar, University of Puerto Rico, Rio Piedras: PR.

Cashin, S. E., & Elmore, P. B. (1997, March). Instruments used to assess attitudes toward statistics. A psychometric evaluation. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Chicago.

Cashin, S. E., & Elmore, P. B. (2005). The survey of attitudes toward statistics scale: A construct validity study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 65, 509–524.

Cohen, S., & McKay, G. (1984). Social support, stress and the buffering hypothesis: A theoretical analysis. In A. Baum, J. E. Singer, & S. I. Taylor (Eds.), Handbook of psychology and health (Vol. 4, pp. 253–267). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 310–357.

Cruise, R. J., Cash, R. W., & Bolton D. L. (1985, August). Development and validation of an instrument to measure statistical anxiety. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Statistical Association Statistics Education Section. Las Vegas, Nevada.

Cruise, R., & Wilkins, E. (1980). STARS: Statistical anxiety rating scale. Unpublished manuscript, Andrews University, Michigan.

Davis, S. (2003). Statistics anxiety among female African American graduate-level social work students. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 23, 143–158.

Elmore, P. B., Lewis, E. L., & Bay, M. L. G. (1993, April). Statistics achievement: A function of attitudes and related experiences. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Atlanta, GA.

Faul, F. (2006). G*Power Version 3.0.3 [Computer software]. Retrieved October 12, 2007, from http://www.psycho.uni-duesseldorf.de/abteilungen/aap/gpower3/

Finney, S. J., & Schraw, G. (2003). Self-efficacy beliefs in college statistics courses. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 28, 161–186.

Forte, J. A. (1995). Teaching statistics without sadistics. Journal of Social Work Education, 31, 204–218.

Gal, I., & Ginsburg, L. (1994). The role of beliefs and attitudes in learning statistics: Towards an assessment framework. Journal of Statistics Education, 14(3). Retrieved September 8, 2010, from http://www.amstat.org/publications/jse/v14n3/vanhoof.html.

Gall, M. D., Gall, J. P., & Borg, W. R. (2007). Educational research: An introduction (8th ed.). Boston: Pearson.

Harvey, A. L., Plake, B. S., & Wise, S. L. (1985, April). The validity of six beliefs about factors related to statistics achievement. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Chicago, IL.

Lane, A. M., Hall, R., & Lane, J. (2004). Self-efficacy and statistics performance among sports studies students. Teaching in Higher Education, 9, 435–448.

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Larkin, K. C. (1984). Relation of self-efficacy expectations to academic achievement and persistence. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 31, 356–362.

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Larkin, K. C. (1986). Self-efficacy in the prediction of academic performance and perceived career options. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 33, 347–382.

Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (1999). Statistics anxiety of among African American graduate students: An affective filter. Journal of Black Psychology, 25, 189–209.

Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2000). Statistics anxiety and the role of self-perception. Journal of Educational research, 93, 323–335.

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., DaRos, D., & Ryan, J. M. (1997). The components of statistics anxiety: A phenomenological study. Focus on Learning Problems in Mathematics, 19, 11–35.

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Daly, C. E. (1999). Perfectionism and statistics anxiety. Personal and Individual Differences, 26, 1089–1102.

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., Slate, J. R., Paterson, F., Watson, M. H., & Schwartz, R. A. (2000). Factors associated with achievement in educational research courses, Research in Schools, 7, 53–65.

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Wilson, V. A. (2003). Statistics anxiety: Nature, etiology, antecedents, effects, and treatments. A comprehensive review of literature. Teaching in Higher Education, 8, 195–209.

Pajares, F. (1996). Self-efficacy beliefs in academic settings. Review of Educational Research, 66, 543–578.

Pajares, F., & Miller, M. D. (1995). Mathematics self-efficacy and math outcomes: The need for specificity in assessment. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 42, 190–198.

Pan, W., & Tang, M. (2005). Students’ perceptions on factors of statistics anxiety and instructional strategies. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 32, 205–214.

Pan, W., & Tang, M. (2004). Examining the effectiveness of innovative instructional methods on reducing statistics anxiety for graduate students in the social sciences. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 31, 149–159.

Perney, J., & Ravid, R. (1991). The relationship between attitudes towards statistics, math self- efficacy concept, test anxiety and graduate students’ achievement in an introductory statistics course. Unpublished manuscript, National College of Education, Evanston, IL.

Roberts, D. M., & Bilderback, E. W. (1980). Reliability and validity of a statistics attitude survey. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 40, 235–238.

Roberts, D. M., & Saxe, J. E. (1982). Validity of a statistics attitude survey. A follow-up study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 42, 907–912.

Schau, S., Stevens, J., Dauphinee, T. L., & Del Vecchio, A. (1995). The development and validation of the survey of attitudes toward statistics. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 55, 868–875.

Schultz, K. S., & Koshino, H. (1998). Evidence of reliability and validity for Wise’s attitude towards statistics scale. Education and Psychological Measurement, 82, 27–31.

Solberg, V. S., & Villarreal, P. (1997). Examination of self-efficacy and assertiveness as mediators of student stress. Psychology: A Journal of Human Behavior, 34, 61–69.

Sutarso, T. (1992, November). Some variables related to students’ anxiety in learning statistics. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Mid-South Educational Research Association. Knoxville, TN.

Tomazic, T. J., & Katz, B. M. (1988, August). Statistics anxiety in introductory applied statistics. Paper presented at the meeting of the American Statistical Association, New Orleans, LA.

Walsh, J. J., & Ugumba-Agwunobi, (2002). Individual differences in statistics anxiety: The roles of perfectionism, procrastination and trait anxiety. Personal and Individual Differences, 33, 239–251.

Waters, L. K., Martelli, T. A., Zakrajsek, T., & Popovich, P. M. (1998). Attitudes toward statistics: An evaluation of multiple measures. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 48, 513–516.

Wise, S. L. (1985). The development and validation of a scale measuring attitudes towards statistics. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 45, 401–405.

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52, 30–41.

Zimet, G. D., Powell, S. S, Farley, G. K, Werkman, S., & Berkoff, K. A. (1990). Psychometric characteristics of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 55, 610–617.

Zeidner, M. (1991). Statistics and mathematics anxiety in social students: Some interesting parallels. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 61, 319–328.

Zimmerman, B. J., Bandura, A., & Martinez-Pons, M. (1992). Self-motivation for academic attainment: The role of self-efficacy beliefs and personal goal setting. American Educational Research Journal, 31, 845–862.

Zimmerman, B. (2000). Self-efficacy: An essential motive to learn. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 82–91.

Michelle Perepiczka, NCC, and Nichelle Chandler, NCC, are professors at Walden University. Michael Becerra, NCC, is an Assistant Professor at the University of Alabama. Correspondence can be addressed to Michelle Perepiczka, Walden University, School of Social Work and Human Services, 100 Washington Avenue South, Suite 900, Minneapolis, MN, 55401,

mperepiczka@gmail.com.

Sep 4, 2014 | Author Videos, Volume 1 - Issue 2

Robert C. Reardon, Sara C. Bertoch

Educational counseling has declined as a counseling specialization in the United States, although the need for this intervention persists and is being met by other providers. This article illustrates how career theories such as Holland’s RIASEC theory can inform a revitalized educational counseling practice in secondary and postsecondary settings. The theory suggests that six personality types—Realistic, Investigative, Artistic, Social, Enterprising, and Conventional—have varying relationships with one another and that they can be associated to the same six environmental areas to assess educational and vocational adjustment. Although educational counseling can be viewed as distinctive from mental health counseling and/or career counseling, modern career theories can inform the practice of educational counseling for the benefit of students and schools.

Keywords: educational counseling, career theory, Holland, secondary education, postsecondary education

In searching for a formal definition of educational counseling, we found only one in the APA Dictionary of Psychology (VandenBos, 2007):

The counseling specialty concerned with providing advice and assistance to students in the development of their educational plans, choice of appropriate courses, and choice of college or technical school. Counseling may also be applied to improve study skills or provide assistance with school-related problems that interfere with performance, for example, learning disabilities. Educational counseling is closely associated with vocational counseling because of the relationship between educational training and occupational choice. (p. 314)

The Counseling Dictionary (Gladding, 2006) does not mention the term “educational counseling” in the following definition of counseling.

The application of mental health, psychological or human development principles, through cognitive, affective, behavioral or systemic interventions, strategies that address wellness, personal growth, or career development, as well as pathology. (Gladding, 2006, p. 37)

A renewed focus on educational counseling may be underway. The American Counseling Association meeting in Pittsburgh in 2010 brought together delegates from 29 major counseling organizations who agreed for the first time on a common definition of counseling. Educational goals were explicitly included in this definition: “Counseling is a professional relationship that empowers diverse individuals, families and groups to accomplish mental health, wellness, education, and career goals” (Breaking News, May 7, 2010).

The purpose of this article is to describe five functions essential for educational counseling (Hutson, 1958) and to use them to illustrate how Holland’s RIASEC theory might inform this counseling practice: (a) choosing a college or school for postsecondary training, (b) selecting an academic program or major, (c) adjusting to the college or academic program, (d) assessing academic performance, and (e) connecting education, career, and life decisions.

Historical Perspective

In tracing what has happened to educational counseling, a brief historical review can be helpful. In the early days of the vocational guidance movement, Brewer (1932) shifted the focus of guidance from vocation and occupation to education and instruction. He went so far as to institutionalize guidance as a professional field by linking the terms education and guidance and even using them synonymously. This could have elevated educational counseling to a more prominent position in the profession, but that did not happen. Brewer and others viewed guidance as limited by the descriptive adjective “vocational” with an emphasis on occupational choice (Shertzer & Stone, 1976), and this resulted in an estrangement between vocational and educational counseling.

Shertzer and Stone (1976) reported that the term “educational guidance” was first used in a doctoral dissertation by Truman L. Kelley at Teachers College, Columbia University, in 1914, and that he used it to describe the help given to students who had questions about choice of studies and school adjustment. Stephens (1970) pointed out that the shift from vocational choice to “guidance as education” ruptured the basic nature of the vocational guidance movement, separating the focus on “vocation” to “education.” Thus, vocational theory became associated with occupational choice and only tangentially related to educational choice, and we view this as leading to the separation of educational guidance and counseling from career theory.

In a comprehensive review of educational guidance literature published from 1933–1956, Hutson (1958) saw the counseling element of the educational guidance program as its most important function. He devoted a chapter to “Counseling for Some Common Problems” in which he identified 10 discrete but overlapping counseling situations. Several elements focused on educational counseling, including choice of subjects and curriculums, college-going (choice of going to college or working; choice of a particular college), and length of stay in school. Each of these problem areas involved counseling related to student psychological and educational characteristics, goals, and decision-making skills. Of relevance to this article, Hutson identified no theory related to educational counseling and cited only the vocational theory of Eli Ginzberg (Ginzberg, Ginsburg, Axelrad, & Herma, 1946) as informing vocational counseling. Theory-based educational counseling had not yet arrived.

The practice of educational counseling has faded from view in contemporary guidance and counseling literature. We conducted a search of journal titles and abstracts within the social sciences area using the term “educational counseling” and our university’s online library database system using Cambridge Scientific Abstracts (CSA) and PsychInfo. We were interested in how many “hits” for the past 10 years we would find in the following journals: Career Development Quarterly, Journal of Career Assessment, Journal of College Counseling, Journal of College Student Development, Journal of Counseling & Development, and Journal of Counseling Psychology. The search provided a total of seven results with only four falling into one of these six journals.

Advising, Coaching, Brokering

While the field of educational counseling seems to have been in decline for the past 50 years, other specialties have emerged to take its place, including academic advising, academic coaching, and educational brokering.

The field of academic advising has been very active in the past 30 years. Ender, Winston, and Miller (1984) defined developmental academic advising as “a systematic process based on a close student-advisor relationship intended to aid students in achieving educational, career, and personal goals through the utilization of the full range of institutional and community resources” (p. 19). Later, Creamer (2000) defined it as “an educational activity that depends on valid explanations of complex student behaviors and institutional conditions to assist college students in making and executing educational and life plans” (p. 18). While generally careful to distinguish between the terms advising and counseling, the National Academic Advising Association (NACADA; http://www.nacada.ksu.edu/index.htm) has fully embraced most of the educational planning and adjustment issues faced by postsecondary students that heretofore might have been included in the domain of educational counseling.

It is beyond the scope of this article to fully explore the notion of academic coaching, so we will limit our comments to the general field of life and career coaching (Chung & Gfroerer, 2003; Patterson, 2008). In general, proponents view coaching as a service focused on a student’s future goals and the creation of a new life path based on less formal collegial mentoring relationships and a positive, preventive wellness model. Opponents view coaching as practicing counseling without proper training or certification because there are limited professional standards or requirements in the coaching field.

Finally, the educational brokering movement in the 1970s was focused on helping adult learners navigate their way through postsecondary educational experiences (Heffernan, 1981). The educational broker independently assisted learners in the process of exploring, researching, and deciding on educational alternatives available. Some educational brokering proponents (Heffernan, 1981) held the view that an educational counselor employed by a specific institution would be biased and “guide” prospective students into the academic programs offered by the employing organization. Brokers were seen as neutral guides to the full range of educational options available to postsecondary learners.

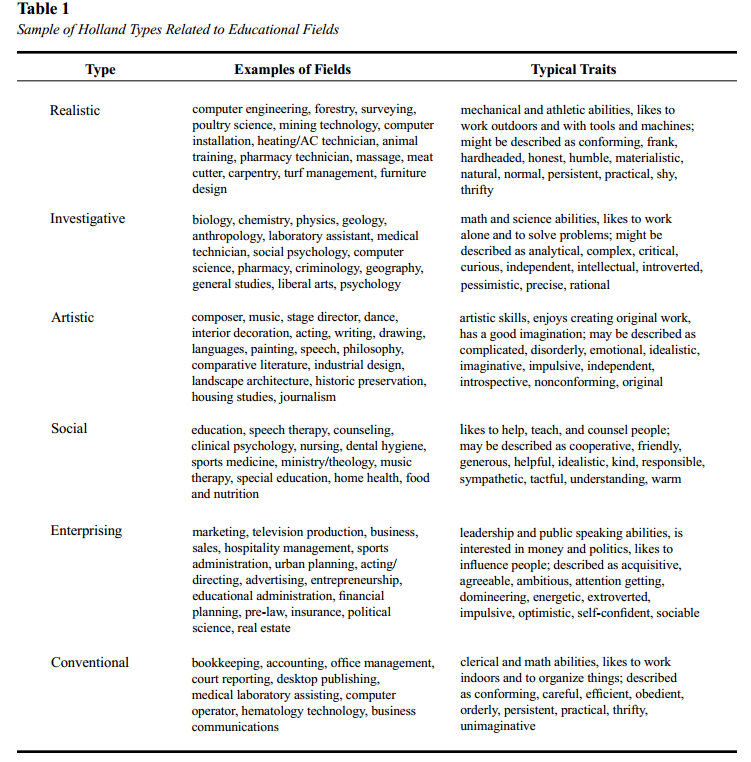

Modern Career Theories

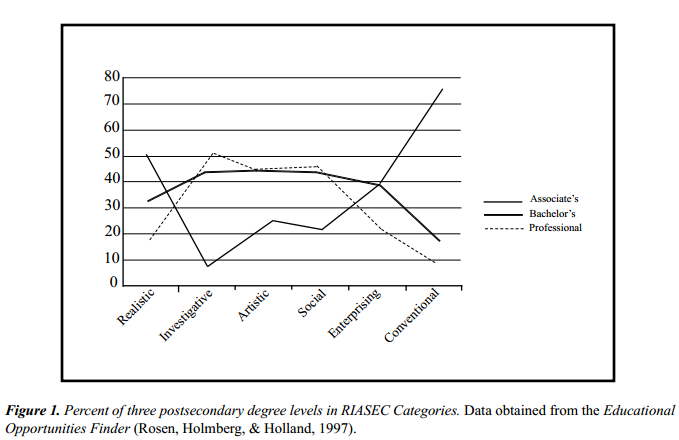

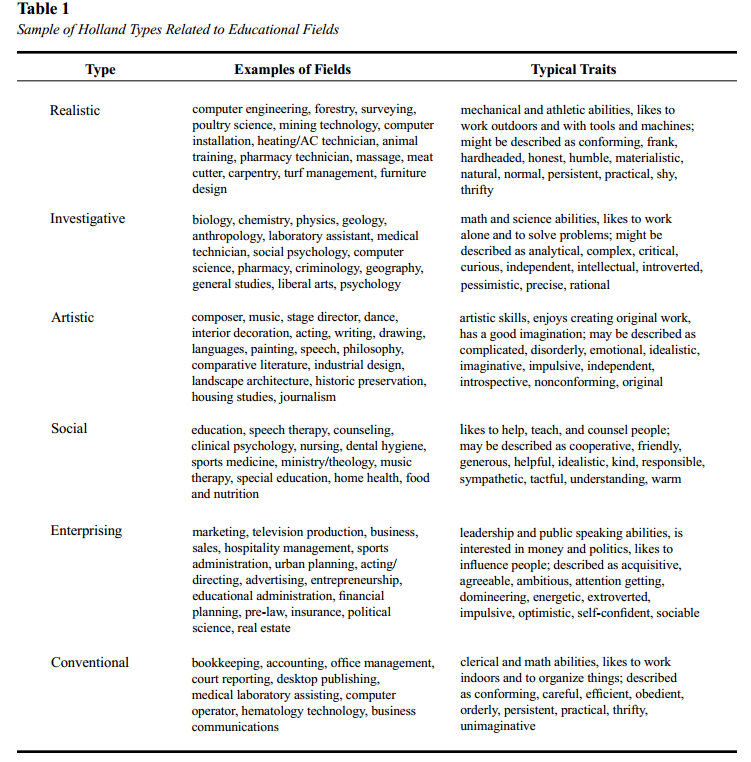

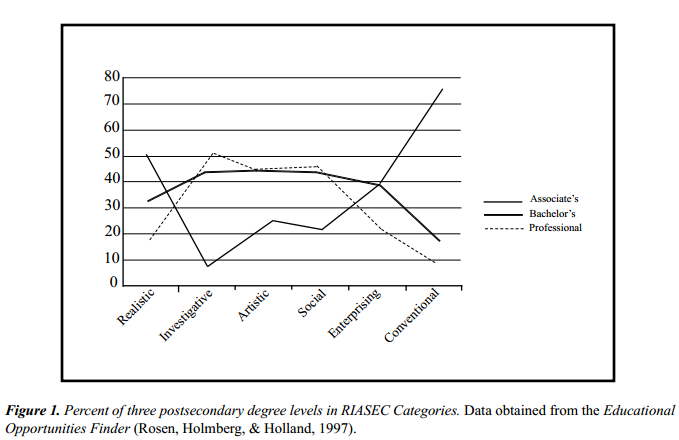

In this article, we examine the topic of educational counseling and suggest that modern career theories could contribute to a revitalization of this function. These theories, identified and described by Brown (2002), include career contextualist theory (Young, Valach, & Collin, 2002); Gottfredson’s theory of circumscription, compromise, and self-creation (L. Gottfredson, (2002); cognitive information processing theory (Sampson, Reardon, Peterson & Lenz, 2004); life stage/life space theory (Super, Savickas, & Super, 1996); narrative construction theory (Savickas, 2002); person-environment correspondence theory (Dawis, 2002); RIASEC theory (Holland, 1997); and social cognitive career theory (Lent, Brown, & Hackett, 2002). We illustrate our idea of how career theory might be useful in educational guidance and counseling programs using Holland’s (1997) RIASEC theory, emphasizing the environmental aspect of the theory.

Thus far, we have identified the function of educational counseling as an early component of the developing field of guidance and counseling, and we have outlined trends that have negated that function more recently. The irony is that the need for educational counseling services remains strong today, but it needs revitalization. We believe that the application of new theory, especially career theory, would be useful in that process and inform practice and research in the field. In this article, we focus on Holland’s RIASEC theory as one theory for accomplishing this revitalization. At the same time, we draw upon some of the basic functions of educational counseling drawn from the literature (Hutson, 1958; VandenBos, 2007).

Holland’s RIASEC Theory

Holland’s theory and the related tools such as the Self-Directed Search (SDS; Holland, 1994) have become familiar icons in the career counseling field. Since the introduction of the SDS in 1972 and its use with over 29 million people worldwide (Psychological Assessment Resources, 2009), its incorporation into the Strong Interest Inventory (Harmon, Hansen, Borgen, & Hammer, 1994) and many other tools, we believe that most counselors feel comfortable and knowledgeable about this system. However, we also believe that the widespread familiarity with the hexagon and SDS is based on incomplete and outdated understandings of Holland’s contributions. For many, the theory is viewed as a simple matching model of three personality types, e.g., the three-letter SDS summary code, and the codes of occupations taken from some source, e.g., O*Net (http://online.onetcenter.org/), Occupations Finder (Holland, 2000).