Feb 7, 2022 | Volume 12 - Issue 1

Emily Sallee, Abraham Cazares-Cervantes, Kok-Mun Ng

Suicide is the second leading cause of death in adolescents (ages 12–19) in the United States, and more work is needed to shed light on the interpersonal protective factors associated with adolescent suicidality. To address this gap in the empirical literature, we examined the application of the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (IPTS) to the middle adolescent population. We analyzed survey data using the 2017 Oregon Healthy Teen dataset, which included 10,703 students in 11th grade. Binary logistic regressions were used to examine the extent to which the IPTS constructs of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness predicted middle adolescent suicide ideation and attempt. Findings indicate that three of the five proxy items were statistically significant in each model, with consistent mediators for each. These findings have the potential to guide development of appropriate treatment strategies based on the interpersonal constructs of the IPTS for clinicians working with this population.

Keywords: adolescents, suicide ideation, suicide attempt, suicidality, Interpersonal Theory of Suicide

Suicide is a leading cause of death worldwide, spanning across all ages, ethnicities, genders, cultures, and religions. In the United States from 2000 to 2015, suicide rates increased 28%, with 44,193 people dying by suicide yearly, equating to about one death every 12 minutes. Nationally, statistics now identify suicide as the second leading cause of death in adolescent populations (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2017). Specific to the state of Oregon, over 500 youth between the ages of 10–24 were hospitalized each year because of self-harm, including suicide attempts. In 2017 alone, more than 750 youth were hospitalized and 107 suicides were completed; considering that many ideations and attempts do not result in hospitalization, it is likely that there were more Oregonian youth who had attempted suicide but were never hospitalized, and an even greater number who had contemplated suicide (Oregon Suicide Prevention, n.d.).

Unfortunately, studies on suicide, particularly adolescent suicide, are rarely driven by theory. This results in a lack of integration between research findings and clinical practice (King et al., 2018). Clinicians working with the adolescent population are in need of research- and evidence-based practices ready for implementation. Although the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (IPTS; Joiner et al., 2009) was initially developed for and then applied to adult populations, it has the potential to inform clinicians in preventative and intervention efforts in other populations, offering an evidence-based framework to understand and address suicide prevention and intervention. In an earlier study (Sallee et al., 2021), we found evidence to support its use with the early adolescent (ages 11–14) population. The present study utilizes the IPTS as a framework to examine the interpersonal drivers of suicidality among middle adolescents (ages 14–17) in Oregon.

Joiner et al.’s (2009) IPTS offers a theoretical lens to explain suicide ideation and behavior in three dynamic constructs: perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and acquired capability. The first two are influential in suicidal desire. The dynamicity of the constructs is related to the fluctuation of interpersonal needs and cognitions over time. Together they contribute to significant risk for suicide ideation. Acquired capability is static and believed to develop in response to exposure to provocative, painful, and/or violent experiences, overpowering the human survival need of self-preservation. Acquired capability, in tandem with thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness, results in a high risk for suicidal behavior/attempt (King et al., 2018).

This field of research uses terms like suicide ideation, suicidal behavior, suicidology, self-harm, self-injury, and self-inflicted death to describe the thoughts and behaviors of a person ending their own life. The CDC defines suicide ideation within a broader class of behavior called self-directed violence, referring to “behaviors directed at oneself that deliberately results in injury or the potential for injury . . . [it] may be suicidal or non-suicidal in nature” (Stone et al., 2017, p. 7). The intent of suicidal self-directed violence is death, while the intent of non-suicidal self-directed violence is not. A suicide attempt may or may not result in death or other injuries. Because we held a particular interest in adolescent suicide ideation and behavior, its differentiation of lethal intent from non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) led us to leave NSSI ideation and/or behavior out of the scope of the study. However, recent studies addressing IPTS have included self-harm as an indicator of acquired capability (e.g., Barzilay et al., 2019) and should be included in future studies involving this construct.

Suicide ideation and attempt in adolescent populations is a serious public health concern in the United States that is growing in frequency and intensity every year. National statistics suggest that 17.2% of adolescents have experienced or currently experience suicide ideation, and 7.4% of adolescents have made a suicide attempt (CDC, 2017). Despite this growing health concern, most research in this body of work has focused primarily on adult populations (Horton et al., 2016; Stone et al., 2017). Limitations in the extant empirical literature include a lack of emphasis on theory as well as a lack of quantitative research on large samples in non-inpatient treatment settings (Czyz et al., 2015; Horton et al., 2016; Miller et al., 2014). In clinical practice, this challenges mental health practitioners’ ability to rely on evidence to serve their clients. Becker et al. (2020) found significant evidence of the applicability of IPTS to a large undergraduate (ages 18–29) population, suggesting that the interpersonal constructs might be applicable to younger non-inpatient groups. Based on the IPTS, this study examined the extent to which a specific set of interpersonal predictors of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belonging were associated with suicide ideation and attempt in a large non-clinical sample of middle adolescents.

Adolescents and Suicidality

Adolescence marks the developmental period between childhood and adulthood, corresponding to the time from pubertal onset to guardian independence. This period is associated with increased risk-taking behaviors as well as increased emotional reactivity, occurring in the context of developmental changes influenced by external and internal factors that elicit and reinforce behaviors. Cognitively, over the course of adolescence, the prefrontal cortex of the brain continues to develop and is responsible for impulse control and delayed gratification in favor of more goal-directed choices and behaviors (Jaworska & MacQueen, 2015). One apparent risk factor for suicide ideation and behavior in adolescents is their impaired decision-making. In addition, this developmental period also accounts for half of all emotional and behavioral disorder diagnoses and the highest rates of suicide with subsequent higher risks for suicidal behavior during their lifetime (Wyman, 2014). Wasserman et al. (2015) metabolized research supporting the theory that most pathological changes occur in childhood and adolescence, suggesting that it is during this developmental time period that prevention and intervention is imperative, as the adolescent years themselves prove to be a risk factor for suicide ideation and behavior.

The typical age of 11th grade students is 16 or 17, and these students are characterized as being in the developmental period known as “middle adolescence.” By this age, puberty is typically completed for both males and females, and adolescents begin setting long-term goals, concurrently becoming more interested in the meaning of life and moral reasoning. They experience an increased drive for independence and increased self-involvement. During the overall developmental stage of adolescence, youth must adjust to their physically and sexually maturing bodies and feelings; define their personal sense of identity and adopt a personal value system; renegotiate their relationships with parents, family, and caregivers; and develop stable and productive peer relationships (Teipel, 2013).

Of relevance to the present study, it is important to note that according to Teipel (2013), adolescents in 11th grade (ages 16–17) experience an increased concern with their appearances and bodies, incorporating a personal sense of masculinity or femininity into their identities and establishing values and preferences of sexual behavior. This period of self-involvement results in high expectations of self and low self-concept, coinciding with an increased drive for peer acceptance and reliance (American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 2021). Additionally, as the typical adolescent is tasked with gaining autonomy and independence from the nuclear family, they will likely experience periods of sadness as the psychological loss, not so unlike grief, takes place (Teipel, 2013). Adolescents in the 11th grade school environment are preparing for the final year of high school and potentially postsecondary education after graduation, creating unique stressors related to increasing autonomy and independence as they approach the formidable ascent into adulthood.

The IPTS

Theories of suicide have evolved over the past 70 years to reflect research and societal influences and implications, yet they all seem to agree that “perceived disruption of interpersonal relationships may serve as one potential mechanism of the association between child maltreatment and [suicide ideation]” (Miller et al., 2014, p. 999). Durkheim and Simpson (1951) suggested that suicide was the result of social causes like isolation, altruism, and anger/frustration. Behavioral theorists like Lester (1987) believed that suicide was a learned behavior, resulting from adverse childhood experiences and psychosocial environmental factors. Schneidman (1993) thought suicidal behaviors were motivated by the desire to escape emotional pain caused by the lack of socially supportive and nurturing relationships. Joiner’s IPTS focuses on the importance of interpersonal relationships, characterized by the confluence of two negative interpersonal states (i.e., perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness; Miller et al., 2014).

The present study was guided by several gaps in the literature related to the application of the IPTS to adolescent populations. Initially, the IPTS was constructed by Joiner and his colleagues (2009) through studying adults engaging in suicidal behaviors. Since its development, the theory has been studied primarily in its application to adult and college student populations (Horton et al., 2016). The lack of research on the application of the IPTS to non-inpatient adolescents may suggest its incompatibility to the uniqueness of adolescent suicidality; however, Horton et al. (2016) argued that the constructs of the theory are relevant in adolescence regardless of setting and presentation, though they may manifest in slightly different ways based on differences in developmental context. As such, they proposed that perceived burdensomeness in adolescents may manifest as low academic competency or social disconnection and thwarted belongingness may manifest as social isolation from peers or poor family cohesion. Adolescence is also a developmental period when children may begin to engage in health-risk behaviors, are particularly prone to impulsivity because of the immature nature of their prefrontal cortex, and have the increased pressure of peer behavior on their own, as well as a sense of invulnerability to consequences (Horton et al., 2016). Though adolescent suicide–related research based on the IPTS to date remains sparse, the theory’s focus on the dynamic constructs of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness appears attractive in consideration of potential application to preventative and responsive efforts.

Perceived Burdensomeness

Perceived burdensomeness is characterized by self-hatred and the belief that one is a burden to others, including family and friends, leading to the idea that they would be better off without them. It deals with the misperceptions of being a liability for family and intimate peers. As a dynamic interpersonal construct, it responds well to both interpersonal and intrapersonal interventions. However, although perceived burdensomeness responds more slowly to intervention, it may be a more significant predictor of suicide ideation and behavior than thwarted belongingness. There is also research that suggests that thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness are more enmeshed in adolescents, suggesting that only one of the dynamic interpersonal constructs is necessary to be coupled with acquired capability and lead to suicidal behavior (Chu et al., 2016; Joiner et al., 2012; Stewart et al., 2017).

Thwarted Belongingness

Thwarted belongingness is a dynamic condition of social disconnection described by the interpersonal state of loneliness in which the psychological need to belong is not met. Of the two dynamic interpersonal constructs within the IPTS that respond to both interpersonal and intrapersonal interventions (thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness), research suggests that thwarted belongingness may be easier to treat and respond more quickly to intervention than perceived burdensomeness (Chu et al., 2016; Joiner et al., 2012; Stewart et al., 2017). It has been well established that positive and negative effects of close relationships are particularly formative in the adolescent years, and therein lies the difficult developmental task of establishing strong peer relationships while also maintaining familial bonds (Miller et al., 2014). Relatedly, adolescents with histories of abuse or other maltreatment are at particular risk. It has been shown that low perceived quality of family and peer connectedness and belonging contribute to thwarted belongingness and its dynamic interpersonal state.

Acquired Capability

Acquired capability is a static construct in the IPTS, describing a decrease in or lack of fear about death and an elevated tolerance of physical pain. It is suggested to be developed through repeated exposure to painful and provocative events (Chu et al., 2016; Joiner et al., 2012; Stewart et al., 2017). Stewart et al. (2017) characterized it as “the combination of increased pain tolerance and decreased fear of death [that] results in progression from suicide intent to suicidal behavior, culminating in a suicide attempt” (p. 438). This construct’s combination of pain tolerance and fearlessness about death is significant in current conversations around adolescents engaging in violent video games, which could correlate to fearlessness about death but not necessarily pain tolerance (Stewart et al., 2017). Acquired capability as the combination of pain tolerance and fearlessness is also significant to other mental health disorders, including anorexia nervosa, in which risk factors for suicide ideation and behavior are prevalent and are characterized by increased pain tolerance and fearlessness about death.

According to the IPTS, these three constructs are proximal to suicidal behavior. Horton et al. (2016) suggested that “an important strength of the theory is that it explains the lower frequency of more severe levels of suicidality (such as suicide attempt) compared to less severe levels (such as passive suicide ideation)” (p. 1134) because it is the combination of the three constructs that leads to suicidal behavior. The theory also posits that the difference between passive and active suicide ideation is the difference between the presence of one or both of the dynamic interpersonal states of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness. In other words, one dynamic interpersonal construct suggests passive ideation, two suggest active ideation, and all three constructs lead to suicidal behavior.

Purpose of the Present Study

Most previous studies that applied the IPTS to suicidal adolescents of this specific age group only addressed inpatient populations (e.g., Czyz et al., 2015; Horton et al., 2016; Miller et al., 2014). However, our recent study (Sallee et al., 2021) indicated support for using this theory in understanding suicide ideation and attempts among non-inpatient early adolescents. Specifically, the findings revealed significance in multiple mediators representing the IPTS constructs of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness. The significant drivers for suicide ideation included emotional/mental health and feeling sad/hopeless as the proxy items for perceived burdensomeness, and not straight and bullied as the proxy items for thwarted belongingness. Similarly, the significant drivers for suicide attempt included emotional/mental health and feeling sad/hopeless as the proxy items for perceived burdensomeness, and non-binary and bullied as the proxy items for thwarted belongingness. The current study extends the efforts of using the IPTS in studying suicidality among adolescents to an older age range (ages 16–17). Using the theory to examine suicidal behavior among middle adolescents in school settings can potentially extend its utility and inform practitioners who are working with youth in this age group who struggle with suicide ideation and behavior in various settings such as mental health and medical.

Based on the IPTS, the focus of this study was to examine the extent to which the interpersonal constructs of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness predict adolescent suicide ideation and attempt. In consideration of the aforementioned needs and gaps in this field of study, we formulated two research questions: 1) To what extent do feelings of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness predict suicide ideation among 11th grade students (a middle adolescent population) in Oregon? and 2) To what extent do feelings of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness predict suicide attempts among 11th grade students (a middle adolescent population) in Oregon? We hypothesized that the two dynamic IPTS constructs would both statistically significantly predict suicide ideation and suicide attempts in this population.

Method

Participants

A dataset of 10,703 participants was selected from the randomized weighted sample of 11,895 students in 11th grade who participated in the 2017 Oregon Healthy Teen (OHT) survey, a comprehensive assessment measuring risk factors and assets shown to impact successful development (Oregon Health Authority [OHA], 2017). This dataset was selected for its representation of middle adolescents at the cusp of a monumental transition in life—finishing K–12 education and embarking on what is to come. Participants’ ages ranged from 16 to 17 years (M = 16.7 years). In terms of gender identity, 48.9% self-identified as female, 45.6% as male, and 5.5% as non-binary/gender nonconforming, which included those who identified as “transgender, gender nonconforming, genderqueer, gender fluid, intersex/intergender, or something else.” Among the participants, 85.9% spoke English at home. The racial/ethnic composition was as follows: 62.9% White, 25% Hispanic/Latino, 3.6% Asian, 2.2% Black or African American, 5.5% other, and 0.8% multiple.

Procedures

We conducted a secondary analysis of archival survey data collected in the 2017 OHT survey. The 2017 OHT study utilized a probability design (i.e., all participants’ datasets had equal chances to be selected for the sample) to minimize possible selection biases and a randomization process (lottery method or computer-generated random list) to minimize sampling error with stratification of school regions. The survey was administered by school officials during one designated school period, utilizing standardized procedures to protect student privacy and facilitate anonymous participation. The researchers obtained IRB approval prior to requesting and receiving the data in SPSS format from the OHA.

The OHT Dataset

The OHT survey has origins in the Youth Risk Behavior Survey, a biennial national survey developed by the CDC. The 2017 OHT survey, administered to volunteering eighth and 11th grade students with a school response rate of 83% (R. Boyd personal communication, February 22, 2019), was chosen for this study because it explores a variety of health-related items, including suicidality, and has additional items deemed suitable for proxy descriptors of the IPTS constructs. The 11th grade dataset was selected for the study to target this specific developmental period because of its characteristic of impaired decision-making serving as a risk factor for ideation and behavior. Additionally, adolescents who experience suicidality during this age range are at a higher risk of suicide ideation and attempt in subsequent life stages compared to adolescents who did not experience suicidality at this time (Wyman, 2014).

In this study, the dynamic interpersonal constructs of the IPTS—perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness—served as variables predicting the two outcome variables of suicide ideation and suicide behavior/attempt. The third construct of the IPTS, acquired capability, was not included as a predictor variable because of its staticity and ineffective response to intervention. We were also unable to locate items in the OHT survey that could be used as proxy items for acquired capability. The two predictor variables were measured with proxy items in the OHT survey (OHA, 2017). The proxy items for each predictor variable were chosen based on empirical research (Horton et al., 2016; Miller et al., 2014; Seelman & Walker, 2018; Zhao et al., 2010). Both outcome variables (suicide ideation and suicide behavior/attempt) were direct questions in the survey, surveyed as follows: 1) “During the past 12 months, did you ever seriously consider attempting suicide?” (Yes/No), and 2) “During the past 12 months, how many times did you actually attempt suicide?” (0, 1 time, 2 or 3 times, 4 or 5 times, 6 or more times). The second question was recorded to combine any number of times larger than zero, reflecting the response that either the participant had not attempted suicide (0) or had attempted suicide (1).

Instrumentation

As previously noted, the selection of proxy items was based on previous empirical research on suicidality, adolescent suicidality, and the IPTS (Horton et al., 2016; Miller et al., 2014; Seelman & Walker, 2018; Zhao et al., 2010). The proxy items selected for this specific study differed slightly from the researchers’ previous study with a younger population (early adolescents) because of the developmentally appropriate differences in the eighth and 11th grade OHT survey tools.

The first predictor variable (perceived burdensomeness) was measured with two proxy survey items: emotional/mental health and sad/hopeless feelings. Emotional/mental health was chosen as a proxy item for the predictor variable of perceived burdensomeness because of the research connecting mental health challenges to emotional strain in the family setting, suggesting a potential perception of being a burden on loved ones (Miller et al., 2014). The survey item for emotional/mental health read: “Would you say that in general your emotional and mental health . . .” with the answer options including: 1) Excellent, 2) Very good, 3) Good, 4) Fair, and 5) Poor. The proxy item of sad/hopeless feelings was chosen because of its inclusion in the definition of perceived burdensomeness but exclusion from many studies of the IPTS (Horton et al., 2016). The survey item for sad/hopeless feelings read: “During the past 12 months, did you ever feel so sad or hopeless almost every day for two weeks or more in a row that you stopped doing some usual activities?” with the answer options of simply Yes or No.

The second predictor variable (thwarted belongingness) was measured with three proxy survey items: sexual orientation, sexual identity, and volunteering (inverse). As previously described, thwarted belongingness constitutes the interpersonal state of loneliness and lack of social connection. Sexual orientation and sexual identity were chosen as proxy items for the variable of thwarted belongingness because sexual minority students experience higher rates of bullying and a greater likelihood of suicidal behaviors (Seelman & Walker, 2018); gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents attempt suicide at 2 to 6 times the rate of non–gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents, suggesting that a sexual minority status is in itself a risk factor for suicidal behaviors, and a child identifying as gay, lesbian, or bisexual and/or as a non-cisgender youth may experience feelings of thwarted belongingness among a peer group (Zhao et al., 2010). The survey item for sexual orientation read: “Do you think of yourself as . . .” with the answer options including: 1) Lesbian or gay; 2) Straight, that is, not lesbian or gay; 3) Bisexual; 4) Something else (Specify); and 5) Don’t know/Not sure. The survey item for sexual identity read: “How do you identify? (Select one or more responses)” with the answer options including: 1) Female, 2) Male, 3) Transgender,

4) Gender nonconforming/Genderqueer, 5) Intersex/Intergender, 6) Something else fits better (Specify), 7) I am not sure of my gender identity, and 8) I do not know what this question is asking. Volunteering (inverse) was chosen because of its suggestion of contributing to society and feeling a sense of belonging and value within the community. The survey item for volunteering read: “I volunteer to help others in my community” with the answer options including: 1) Very much true, 2) Pretty much true, 3) A little true, and 4) Not at all true. Data from this final question was inversely recoded in order to be comparable to the other proxy items.

The CDC utilized existing empirical literature to analyze the self-reported survey data, assessing for cognitive and situational factors that might affect the validity of adolescent self-reporting of behaviors. Through analysis, it was determined that self-reports are in fact affected by both cognitive and situational factors, but the factors do not threaten the validity of self-reports of each behavior equally (Brener et al., 2013).

Data Analysis

This study addresses what impact the predictor variables of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness have on the outcome variables of suicide ideation and suicide attempt in this particular adolescent population. The selected proxy items had variable answer options (ranging from binary choice to a 7-point Likert scale), so each proxy item for the predictor variables was individually entered with the intention of disaggregating to assess whether or not different combinations of the variables are better predictors of the outcome variables.

The two outcome variables were surveyed as follows: (a) suicide ideation (“During the past 12 months, did you ever seriously consider attempting suicide?”) and (b) suicide attempt (“During the past 12 months, how many times did you actually attempt suicide?”; OHA, 2017). The second question was recoded to allow both questions to be assessed on a binary scale (no/yes), with no equaling 0 and yes equaling 1.

With binary scaled data for the outcome variables, we decided to utilize a binomial logistic regression statistical test to assess the research questions. Additionally, each predictor variable was separately analyzed in order to isolate each outcome variable and consider how the predictor variables influenced each other.

In sum, we examined the descriptive statistics of the survey, created variables based on the selected proxy survey items, and tested the assumptions for utilizing a binomial logistic regression statistical test. Finally, we executed two logistic regression models to determine the relationships between the predictor variables and the two outcome variables—suicide ideation and suicide attempt.

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the study variables. Although 11,868 students in the 11th grade completed the 2017 OHT survey, data from only 10,703 students were included in the analysis because of recording and data collection errors on those excluded from the analyses, due to missing or incomplete data. Therefore, the descriptive statistics of the study variables reported in the table reflect the data of the 10,703 students applicable for use in the logistic regression model of this study. Given the large sample size, we utilized a p-value threshold of less than 0.01.

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics

| Variable |

M or %a |

SD (if applicable) |

| Emotional/Mental Health |

2.92 |

1.22 |

| Felt Sad/Hopeless (Yes) |

1.68 |

0.47 |

| Not Straight |

17.0% |

N/A |

| Non-Binary |

5.5% |

N/A |

| Volunteer |

2.38 |

0.99 |

| Consider Suicide |

18.0% |

N/A |

| Attempt Suicide |

6.6% |

N/A |

a Some variables were reported as means, and some variables were reported as percentages.

Results

A binomial logistic regression was conducted to quantify the effects of the individual proxy items measuring the predictor variables of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness on students experiencing suicide ideation (Research Question 1). All five proxy items were entered into the model for the outcome variable. During the data screening process, two proxy items were eliminated (i.e., non-binary, volunteer), as they did not indicate significant results. Regression results indicated the overall model of the three remaining predictors (emotional/mental health, felt sad/hopeless, not straight) was statistically reliable in distinguishing between 11th grade students who did not experience suicide ideation and those who did (Nagelkerke R2 = .413; p < .001). As such, the suicide ideation model was deemed statistically significant—X2(5) = 3104.194—with an overall positive predictive value of 85.5%.

Of the two proxy items for the perceived burdensomeness variable, both proved to be statistically significant (Table 2). Specifically, increased poor emotional/mental health was related to the increased likelihood and occurrence of suicide ideation. Additionally, participants who reported feeling sad or hopeless for at least 2 weeks were over twice as likely to experience suicide ideation than those who did not report feeling sad or hopeless. Of the three proxy items for the thwarted belongingness variable, only one proved to be statistically significant: Students who reported as not straight were more than twice as likely to experience suicide ideation as students who reported as straight.

Table 2

Logistic Regression Predicting Likelihood of Suicide Ideation

| Variable |

B |

SE |

Wald |

df |

p |

Odds |

| Perceived Burdensomeness |

| Emotional/Mental Health |

0.775 |

.033 |

535.821 |

1 |

< .001 |

2.170 |

| Felt Sad/Hopeless |

−1.694 |

.069 |

609.681 |

1 |

< .001 |

0.184 |

| Thwarted Belongingness |

| Not Straight |

0.705 |

.072 |

95.460 |

1 |

< .001 |

2.025 |

| Non-Binary |

0.149 |

.120 |

1.546 |

1 |

.214 |

1.160 |

| Volunteer |

−0.03 |

.031 |

0.949 |

1 |

.330 |

0.970 |

| Constant |

−1.716 |

.189 |

82.107 |

1 |

< .001 |

0.180 |

Similarly, a binomial logistic regression test was conducted to determine the effects of the proxy items measuring the predictor variables of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness on suicide attempt (Research Question 2). Again, all five items were entered into the model for the outcome variable of suicide attempt. During the data screening process, two proxy items were eliminated (i.e., non-binary, volunteer), as they did not indicate significant results. Regression results indicated that the overall model of the three remaining predictors (emotional/mental health, felt sad/hopeless, not straight) was statistically reliable in distinguishing between 11th grade students who did not attempt suicide and those who did (Nagelkerke R2 = .271; p < .001). The suicide attempt model was deemed statistically significant—X2(5) = 1182.692—with an overall positive predictive value of 93.4%. Both proxy items for the perceived burdensomeness variable proved to be statistically significant (Table 3).

Based on the overall regression analyses, increased poor emotional/mental health was related to the increased likelihood and occurrence of suicide attempt; however, students who reported feeling sad or hopeless for at least 2 weeks were nearly twice as likely to attempt suicide than students who did not report feeling sad or hopeless. Of the three proxy items for the thwarted belongingness variable, only one proved to be statistically significant (Table 3). Students who reported as not straight were nearly twice as likely as students who reported as straight to attempt suicide.

Table 3

Logistic Regression Predicting Likelihood of Suicide Attempt

| Variable |

B |

SE |

Wald |

df |

p |

Odds |

| Perceived Burdensomeness |

| Emotional/Mental Health |

0.599 |

.49 |

149.806 |

1 |

< .001 |

1.820 |

| Felt Sad/Helpless |

−1.856 |

.119 |

242.389 |

1 |

< .001 |

0.156 |

| Thwarted Belongingness |

| Not Straight |

0.533 |

.094 |

31.895 |

1 |

< .001 |

1.704 |

| Non-Binary |

0.055 |

.143 |

0.149 |

1 |

.700 |

1.057 |

| Volunteer |

−0.029 |

.042 |

0.490 |

1 |

.484 |

0.971 |

| Constant |

−2.222 |

.296 |

56.368 |

1 |

< .001 |

0.108 |

These results indicated that there were significant similarities between the predictors of suicide ideation and suicide attempt, supporting our hypotheses. The proxy items that comprised perceived burdensomeness (poor emotional health [odds = 1.820] and feeling sad/hopeless [odds = 6.410]) in conjunction with the proxy item that comprised thwarted belongingness (not straight [odds = 1.704]) all factored into increased likelihood of suicide ideation and suicide attempt. In other words, the mediators of suicide ideation were similar to the mediators of suicide attempt.

Discussion

In discussing the results of the study, it is important to first contextualize the descriptive statistics, as we were studying and applying results to adolescent students in Oregon. The dataset reports 18% of the participants as experiencing suicide ideation, which equates to 1,927 students in the 11th grade. This statistic for suicide ideation is a little higher than the national percentage of 17.2% (CDC, 2017). The dataset also reports 6.6% of the participants as attempting suicide, which equates to 703 students in the 11th grade. This statistic for suicide attempt is a little lower than the national 7.4% (CDC, 2017). In terms of our dataset, Oregon 11th graders were slightly higher than expected for suicide ideation and slightly lower than expected for suicide attempt.

Results from our binomial logistic regression analyses uncovered a model supporting our hypothesis that perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness would significantly predict suicide ideation and attempt in 11th grade students. Further, both variables representing perceived burdensomeness were statistically significant for both suicide ideation and attempt, as was one of the three proxy variables representing thwarted belongingness. These findings align with the IPTS, proposing that perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness are not only important predictors of suicidal behaviors, but are significant elements for both ideation and attempt (with the addition of acquired capability for attempt; Horton et al., 2016; King et al., 2018).

Though not a predetermined hypothesis, it seems reasonable to expect that there would be fewer predictors of suicide attempt, condensed from the predictors of suicide ideation, but that is not the case in our findings. It begs the question: What variables drove students in this population from ideation to attempt? According to the data, 18% of the 11th graders experienced suicide ideation, but only 6.6% reported being driven to attempt suicide. The IPTS would suggest that the missing component was a measure of acquired capability that moves a person from ideation to attempt (Joiner et al., 2009). According to the IPTS (Joiner et al., 2009), experiencing perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness without acquired capability leads to suicide ideation, but the presence of acquired capability is needed to result in suicide attempt. This will be discussed further as a limitation of this study.

These results corroborate previous literature on adolescence and suicidality. Horton et al. (2016) described adolescent perceived burdensomeness as social disconnection and adolescent thwarted belongingness as social isolation from peers. As previously described, with regard to poor emotional/mental health and feeling sad/hopeless, Jaworska and MacQueen (2015) highlighted the increased reactivity of adolescence, and Wyman (2014) indicated that half of the diagnoses of emotional and behavioral disorders take place during this age period (highlighting the importance of mental health clinicians being aware of these findings). With regard to not being straight, this time period also includes establishing values and preferences for sexual behavior and affective orientation (Teipel, 2013). These results also corroborate our previous findings on the application of the IPTS to early adolescents (ages 13–14), suggesting similar significant mediators for both suicide ideation (perceived burdensomeness: emotional/mental health, feeling sad/hopeless; thwarted belongingness: not straight, bullied) and suicide attempt (perceived burdensomeness: emotional/mental health, feeling sad/hopeless; thwarted belongingness: non-binary, bullied; Sallee et al., 2021).

Relative to the literature on suicidality and its role in our selection of proxy items within the OHT survey, research on the connection between poor emotional/mental health and emotional strain in the family setting supports our findings of its significance within the predictor variable of perceived burdensomeness (Miller et al., 2014). The significance of feeling sad/hopeless is supported by previous research discussing its inclusion in the definition of perceived burdensomeness itself (Horton et al., 2016). Sexual minority students experience higher rates of suicidal behaviors, attempting suicide at rates of 2 to 6 times that of straight adolescents (Seelman & Walker, 2018; Zhao et al., 2010). Our findings support this body of research in the significance of being not straight in relation to mental health wellness.

The other proxy predictors examined—being non-binary and volunteering—were not statistically predictive of suicidal behavior. This may be due in part to the developmental tasks and goals characteristic of the period of middle adolescence, or the proxy items themselves may not be significant indicators of the predictor variables in the study, or the wrong indicators were chosen or were conceptualized inaccurately. If that is the case, there would be concerns regarding the construct validity of these indicators and subsequent measures, and because that cannot be proven otherwise, it is a considerable limitation to the study. If the developmental tasks and goals of middle adolescence provide the most insight into the insignificance of being non-binary and volunteering, it is important to consider the developmental period of self-involvement resulting in high expectations of self in combination with low self-concept, impacting an increased drive for peer acceptance (American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 2021). Eleventh grade students are also preparing for their final year of high school and making plans for what their lives will look like after graduation, requiring a high degree of autonomy and independence. It is interesting to consider the insignificant predictors through this developmental lens. Although 11th grade students are seeking peer acceptance, being non-binary may not be a driver because of developing autonomy and independence.

We consider how the findings of this study might relate to research indicating a higher rate of suicide for sexual/gender minorities compared to youth from historically well-represented communities (Teipel, 2013), but perhaps disaggregating sexual/gender minority and focusing on non-binary youth in particular may impact that conversation. Volunteering could prove to be a protective factor but drive for peer acceptance and reliance on peers may determine whether or not a student in the 11th grade chooses to volunteer as opposed to self-motivation or fulfillment.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Several limitations must be considered when evaluating the findings of this study. First, because of their correlational nature, we were unable to draw any causal conclusions from the results. Relatedly, the results from this study, despite being based on a large sample, described 11th grade students in Oregon who elected to take the survey and had a complete dataset necessary for analysis; the sample was one of convenience, and the extraction of missing datasets impacted the researchers’ ability to gauge the sample’s ability to represent the whole population. As such, generalization of the results to the larger population of adolescents is limited.

Additionally, the data was taken retrospectively from a survey managed by a state government agency; it would have been preferable for us to have input on the questions included in the 2017 OHT survey. Instead, we were forced to select best-fit proxy items that might or might not have been most representative of the predictor variables. Relatedly, and as previously mentioned, there is cause to question the construct validity of these measures, particularly because the selected proxy items do not correlate to other measures of thwarted belongingness in particular. Because we relied on the 2017 OHT survey data, the models for examining the IPTS constructs were incomplete. Lastly, there is a lack of data about unique stressors experienced by students of color related to their social locations, particularly valuable because 25% of the participants were Hispanic/Latino.

Based on our results, despite the limitations previously discussed, there are a variety of avenues for further research on this topic. The first avenue would be to analyze similar data from another state survey or the national Youth Risk Behavior Survey. This would allow researchers to compare results with this study in order to offer more supported generalization to the adolescent population. Another avenue would be to revisit this dataset and theory to consider how they might apply to other behaviors of the adolescent population, such as NSSI and school violence. Further research could revisit this study by creating a survey that would more fully target the interpersonal constructs of the IPTS or create a qualitative or mixed-methods study incorporating additional data sources to examine more in-depth the suicide-related factors and experiences during adolescence.

Another avenue for future research may be to examine additional prospective mediators that may predict the evolution from ideation to attempt because our results presented the exact same predictors for both. Finally, a valuable possibility for future research would be to study factors that might differentially affect students of color and adolescents from sexual minority groups.

Implications

This particular study offers valuable support for the application of the IPTS in working with middle adolescents as well as useful implications for targeting specific interpersonal needs when working with this population. Perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness may be significant construct predictors of suicide ideation and attempt in adolescents according to the findings. Implications for clinical mental health counselors and other professionals working with this population support the importance of taking a systemic and unique approach to working with adolescents and their families that prioritizes and addresses these specific interpersonal needs individually and collectively.

Specific interventions addressing adolescent interpersonal needs of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness include an array of clinical practices, such as using a suicide screener as part of intake assessments or well-child checks that include items related to these two constructs. Existing suicide intervention modalities need to incorporate and/or integrate the constructs of the IPTS, utilizing counseling goals and interventions that specifically target belongingness and personal value. Further, clinicians must have a basic understanding of the developmental tasks of this period to attend to an adolescent’s stable and productive peer relationships, adoption of personal value systems, and renegotiation of relationships with parents/caregivers, realizing that this transitional stage is also characterized by feelings of grief and loss (Teipel, 2013).

Group counseling is an effective and efficient modality through which a mental health professional can bring together a number of adolescents and facilitate sessions normalizing these developmental tasks and associated feelings. Mental health literacy and bibliotherapy can be used in combination with group counseling, as research has demonstrated their effectiveness on providing structure in the group process, educating adolescents, and fostering connections among the group (Mumbauer & Kelchner, 2017). Groups can also offer parents and caregivers a safe space to navigate family complexities around adolescent suicidality and learn ways to promote a sense of belonging and reduce feelings of burdensomeness among adolescents.

Broader systemic outreach can involve community mental health providers and other professionals collaborating with school stakeholders to offer services such as parent workshops and educator professional development opportunities on understanding suicidality and evidence-based prevention, intervention, and postvention. Partnering with school stakeholders can include consulting on systemic interventions and programming, such as individual student behavior plans, IEPs, and 504 plans, in addition to school- or grade-wide postsecondary transition activities. These consultation and collaboration efforts are often interdependent, in the sense that clinical professionals gain referrals from school stakeholders, and school stakeholders help inform the work of clinical professionals with their adolescent clients.

Through engaging parents, families, school personnel, and their adolescent clients, clinical mental health counselors can work holistically to prevent and intervene in suicidal behaviors by targeting fulfillment and development of interpersonal needs. These findings may have the potential to inform laws and policies through legislative efforts to address adolescent suicide. Clinical mental health counselors have a professional obligation to utilize outcome data to advocate for systemic change to impact clients (Montague et al., 2016), and in this context they may also draw on these findings to provide information to society to assist in advocacy efforts and extend recommendations to professionals working with this population.

Conclusion

The findings of our study support the application of the IPTS in understanding suicidality among middle adolescents, particularly in the ideation model, and are significant in several ways. First, the IPTS has the potential to inform therapeutic interventions in clinical settings, as well as parents and social institutions (e.g., schools and youth development centers), on how best to support youth who experience suicidality. Another focus of our study was on interpersonal factors that are dynamic, rather than static risk factors that may not necessarily be venues for intervention and change for clinicians (e.g., family factors). Third, adolescent clients engaging in suicide ideation and behaviors require interventions that are unique from their adult counterparts and often require environmental and familial interventions as well as individual. Lastly, our findings may serve to provide information to society to assist in advocacy efforts and recommendations for serving adolescent populations within all systems, including laws and policies to address adolescent suicide. Overall, the findings of our study underscore the uniqueness and complexity of this developmental period of adolescence and the importance of theory- and research-based practices. We hope that our findings will inform mental health clinicians, educators, school counselors, parents, and policymakers in their efforts to meet adolescent mental health needs.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. (2021). Facts for families guide. https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/Layout/FFF_Guide-01.aspx

Barzilay, S., Apter, A., Snir, A., Carli, V., Hoven, C. W., Sarchiapone, M., Hadlaczky, G., Balazs, J., Kereszteny, A., Brunner, R., Kaess, M., Bobes, J., Saiz, P. A., Cosman, D., Haring, C., Banzer, R., McMahon, E., Keeley, H., Kahn, J.-P., . . . Wasserman, D. (2019). A longitudinal examination of the interpersonal theory of suicide and effects of school-based suicide prevention interventions in a multinational study of adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(10), 1104–1111. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13119

Becker, S. P., Foster, J. A., & Luebbe, A. M. (2020). A test of the interpersonal theory of suicide in college students. Journal of Affective Disorders, 260, 73–76. https://doi.org/10.1010/j/jad.2019.09.005

Brener, N. D., Kann, L., Shanklin, S., Kinchen, S., Eaton, D. K., Hawkins, J., & Flint, K. H. (2013, March 1). Methodology of the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System—2013. Recommendations and Reports, 62(1), 1–23. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6201a1.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Trends in the prevalence of suicide-related behaviors. National YRBS: 1991–2017. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/trends/2017_suicide_trend_yrbs.pdf

Chu, C., Rogers, M. L., & Joiner, T. E. (2016). Cross-sectional and temporal association between non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal ideation in young adults: The explanatory roles of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness. Psychiatry Research, 246, 573–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.07.061

Czyz, E. K., Berona, J., & King, C. A. (2015). A prospective examination of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior among psychiatric adolescent inpatients. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 45(2), 243–260. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12125

Durkheim, É. (1951). Suicide: A study in sociology. Free Press.

Horton, S. E., Hughes, J. L., King, J. D., Kennard, B. D., Westers, N. J., Mayes, T. L., & Stewart, S. M. (2016). Preliminary examination of the interpersonal psychological theory of suicide in an adolescent clinical sample, Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44, 1133–1144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-0109-5

Jaworska, N., & MacQueen, G. (2015). Adolescence as a unique developmental period. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience, 40(5), 291–293. https://doi.org/10.1503/jpn.150268

Joiner, T. E., Ribeiro, J. D., & Silva, C. (2012). Nonsuicidal self-injury, suicidal behavior, and their co-occurrence as viewed through the lens of the interpersonal theory of suicide. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(5), 342–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721412454873

Joiner, T. E., Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., & Rudd, M. D. (2009). The interpersonal theory of suicide: Guidance for working with suicidal clients. American Psychological Association.

King, J. D., Horton, S. E., Hughes, J. L, Eaddy, M., Kennard, B. D., Emslie, G. J., & Stewart, S. M. (2018, June). The interpersonal–psychological theory of suicide in adolescents: A preliminary report of changes following treatment. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 48(3), 294–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12352

Lester, D. (1987). Murders and suicide: Are they polar opposites? Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 5(1), 49–60.

https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2370050106

Miller, A. B., Adams, L. M., Esposito-Smythers, C., Thompson, R., & Proctor, L. J. (2014). Parents and friendships: A longitudinal examination of interpersonal mediators of the relationship between child maltreatment and suicidal ideation. Psychiatry Research, 220(3), 998–1006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.10.009

Montague, K. T., Cassidy, R. R., & Liles, R. G. (2016). Counselor training in suicide assessment, prevention, and management. In G. R. Walz & J. C. Bleuer (Eds). Ideas and research you can use: VISTAS 2016. https://bit.ly/Vistas2016

Mumbauer, J., & Kelchner, V. (2017). Promoting mental health literacy through bibliotherapy in school-based settings. Professional School Counseling, 21(1), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.5330/1096-2409-21.1.85

Oregon Health Authority. (2017). Oregon Healthy Teens Survey. https://bit.ly/OHTsurvey2017

Oregon Suicide Prevention. (n.d.). Youth. https://www.oregonsuicideprevention.org/community/youth

Sallee, E., Ng, K.-M., & Cazares-Cervantes, A. (2021). Interpersonal predictors of suicide ideation and attempt among early adolescents. Professional School Counseling, 25(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X211018653

Schneidman, D. (1993). 1993 health care reforms at the state level: An update. Bulletin of the American College of Surgeons, 78(12), 17–22. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10130176

Seelman, K. L, & Walker, M. B. (2018). Do anti-bullying laws reduce in-school victimization, fear-based absenteeism, and suicidality for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and questioning youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47, 2301–2319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0904-8

Stewart, S. M., Eaddy, M., Horton, S. E., Hughes, J., & Kennard, B. (2017). The validity of the interpersonal theory of suicide in adolescence: A review. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 46(3), 437–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2015.1020542

Stone, D., Holland, K., Bartholow, B., Crosby, A., Davis, S., & Wilkins, N. (2017). Preventing suicide: A technical package of policy, programs, and practices. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/suicidetechnicalpackage.pdf

Teipel, K. (2013, June). Understanding adolescence: Seeing through a developmental lens. State Adolescent Health Resource Center. http://www.amchp.org/programsandtopics/AdolescentHealth/projects/Documents

/SAHRC%20AYADevelopment%20MiddleAdolescence.pdf

Wasserman, D., Hoven, C. W., Wasserman, C., Wall, M., Eisenberg, R., Hadlaczky, G., Kelleher, I., Sarchiapone, M., Apter, A., Balazs, J., Bobes, J., Brunner, R., Corcoran, P., Cosman, D., Guillemin, F., Haring, C., Iosue, M., Kaess, M., Kahn, J.-P., . . . Carli, V. (2015). School-based suicide prevention programmes: The SEYLE cluster-randomized, controlled trial. The Lancet, 385(9977), 1536–1544. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61213-7

Wyman, P. A. (2014). Developmental approach to prevent adolescent suicides: Research pathways to effective upstream preventative interventions. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 47(3S2), S251–S256. https://doi.org/10.1016/ampere.2014.05.039

Zhao, Y., Montoro, R., Igartua, K., & Thombs, B. D. (2010). Suicidal ideation and attempt among adolescents reporting “unsure” sexual identity or heterosexual identity plus same-sex attraction or behavior: Forgotten groups? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(2), 104–113.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2009.11.003

Emily Sallee, PhD, BC-TMH, LSC, PCLC, is an assistant professor at the University of Montana. Abraham Cazares-Cervantes, PhD, LSC, is an assistant clinical professor at Oregon State University. Kok-Mun Ng, PhD, NCC, ACS, LPC, is a professor at Oregon State University. Correspondence may be addressed to Emily Sallee, 32 Campus Drive #335, Missoula, MT 59834, emily.sallee@umontana.edu.

Feb 7, 2022 | Volume 12 - Issue 1

Diane M. Stutey, Abigail E. Solis, Kim Severn, Lori Notestine, Kodi L. Enkler, Joseph Wehrman, Molly Cammell

There is a need for mental health interventions for youth in the United States. Youth mentoring programs have proven to be successful in helping in a variety of aspects. The purpose of this phenomenological study was to gain insight into the lived experiences of participants in a therapeutic youth mentoring program. In addition to being paired 1:1 with a mentor, all of the youth had access to individual counseling with counselors-in-training throughout the program. The participants in this study were 14 youth, ages 11–15, who were considered “at-promise youth” if they were not reaching their full potential in the school setting and might be vulnerable to school dropout, substance use/misuse, and/or criminal behavior. All participants were interviewed at the beginning and end of a 12-week therapeutic mentoring program. Five themes emerged from the data: life stressors, self-awareness, trusting others, adaptability and resiliency, and hope for the future. Researchers observed an increase in participants’ self-esteem, self-efficacy, and problem-solving and coping skills. Implications for counselors, particularly those interested in adding a therapeutic component to traditional mentoring programs, are discussed along with suggestions for future research.

Keywords: mentoring programs, therapeutic, mental health interventions, at-promise youth, phenomenological

Because of a staggering dropout rate of 1.2 million students a year, as well as an increase of juvenile delinquency in the United States, there is a need for interventions that will help youth stay in school and out of the juvenile justice system (Weiler, Chesmore, et al., 2019; Weiss et al., 2019). Researchers have indicated that the absence of education, including students who do not graduate from high school, has led to an increase of youth experiencing health complications, substance abuse, social skill deficits, and premature death (Schoeneberger, 2012; Weiler, Chesmore, et al., 2019; Weiler et al., 2015; Weiss et al., 2019). In the past, youth exhibiting behaviors that might lead to juvenile delinquency were referred to as at risk. However, the term at promise is now utilized by organizations such as the California Education Code (McKenzie, 2019). The phrase at-promise youth describes youth who have the ability to reach their full potential with additional time and resources.

One way to help at-promise youth reach their full potential and feel more engaged at school might be connecting them with a young adult who understands their struggles. Youth benefit from enhanced connectedness to adults outside their immediate family to help them navigate through difficult times, and this relationship can be protective against suicidal behavior (King et al., 2018; Rhodes, 2002). Individuals within adolescent ecosystems have voiced the positive changes youth have experienced by participating in youth mentoring programs (Raposa et al., 2019). At-promise youth might benefit even more from youth mentoring programs that incorporate a therapeutic component to address mental health concerns they may be experiencing (Liang et al., 2013).

Youth Mentoring Programs

Youth mentoring is a psychosocial intervention in which a nonparental adult and a younger individual aim to develop a supportive relationship (Karcher et al., 2005; Lund et al., 2019; Sacco et al., 2014; Weiler et al., 2013). During the mentoring program, the youth mentees experience a healthy environment, which often leads to them seeking out and learning to cultivate a healthier environment beyond the youth mentoring program. This shift in environment has allowed researchers to observe improvement in self-perception, social acceptance, parent–child interaction, and academic performance of youth participating in mentoring programs (Anastasia et al., 2012). Researchers have found that mentoring programs may also buffer against the impacts of youth exposed to adverse childhood experiences and improve behavioral, social, emotional, and academic outcomes (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019; David-Ferdon et al., 2016; Durlak et al., 2010; Tolan et al., 2014). The relationship between mentor and mentee is heavily credited to the success of youth mentoring, signifying the importance of the mentee picking a mentor similar to them (e.g., appearance, culture, interests).

Researchers discovered that both mentor and mentee benefit from the dyadic relationship when there is trust and the mentor is consistent, supportive, and encouraging instead of controlling (Marshall et al., 2016; Rhodes, 2002; Weiler, Boat, & Haddock, 2019; Weiler et al., 2015; Weiss et al., 2019). A mentor should be supportive and encouraging, especially when giving advice, which helps the youth to be open to a new perspective (Lund et al., 2019; Rhodes, 2002). Youth who participated in a positive mentoring relationship had increased feelings of connectedness with a trusted adult and higher rates of pursuing purpose (Lund et al., 2019). In addition, by the end of youth mentoring programs, the majority of mentees achieved a sense of self-worth and increased levels of intimacy, communication, and trust because of the dyadic relationship they had established with their mentors (Keller & Pryce, 2012; Rhodes, 2002).

Mentors and Youth Mentees

Research on youth mentoring programs has described mentees as individuals who are at risk, may have been in the juvenile justice system, or are in danger of offending or reoffending because of a variety of variables (e.g., substance use, academic failure, absences, aggressive behavior, family stressors) present in their lives (Cavell et al., 2009; Haddock et al., 2017; Weiler et al., 2013). Weiler et al. (2013) noted that more than 60% of the youth who participated in a mentoring program in their study had acquired at least a single charge with the juvenile justice system. Numerous researchers have discussed how the role of a mentor in a mentee’s life helped the mentee with improved self-esteem, enhanced health, instilled hope for the future, and reduced reoffending behaviors (Raposa et al., 2019; Rhodes, 2002; Weiler, Boat, & Haddock, 2019; Weiss et al., 2019).

Training is required before being paired with a mentee to ensure the competency of the adult who will be mentoring the youth facing hardships. Anastasia et al. (2012) emphasized the importance of preparatory training and ongoing training so that mentors, who are not in a helping profession, will have the tools necessary to mentor an adolescent successfully. In the preparatory stage of training, mentors learn about maintaining safety, program rules, child-focused social problem–solving skills, and the activities that will be used throughout the program (Anastasia et al., 2012; Cavell et al., 2009).

At the same time, mentors may feel overwhelmed when mentees exhibit mental health issues, behavioral issues, or racial or socioeconomic differences that surpass their basic training and expertise (Marshall et al., 2016; Weiler et al., 2013). With a majority of the adolescents facing difficulties, it can be daunting for the mentor to provide adequate mentoring; therefore, ongoing training is imperative. Ongoing training is meant to help the mentor increase their effectiveness with their mentee (Anastasia et al., 2012), allowing the adult to seek guidance when they start feeling overwhelmed with their mentee’s behavior and actions (Keller & Pryce, 2012). Through ongoing training and interaction with their paired youth, the adult mentor gains a new level of insight and improved health, self-esteem, and self-awareness that they did not have before (Rhodes, 2002).

However, even with ongoing training, mentees may exhibit mental health needs that are beyond the average mentor’s training and skill set. Liang et al. (2013) highlighted that mentees might benefit from receiving traditional therapy to help with their hardships. Therefore, some mentoring programs have added a therapeutic component incorporating trained mental health personnel to positively support both mentors and mentees (Weiler et al., 2013).

Therapeutic Component to Mentoring

Mental health professionals (e.g., counselors, social workers, psychologists) learn through their education how to be culturally competent, preserve client autonomy, and maintain an unbiased perspective that is crucial when trying to develop a mentoring relationship (Anastasia et al., 2012). Liang and colleagues (2013) emphasized how youth with therapeutic needs benefit from the way therapeutic guidance and a mentoring program complement each other. For instance, if a child is stressed about how to pay for college, then a mentor can help their mentee find resources, while a therapist could focus on teaching healthier coping skills to manage stress (Liang et al., 2013). Working in tandem allows for a two-dimensional approach, a noteworthy difference between therapeutic mentoring and traditional mentoring programs (Sacco et al., 2014).

Some therapeutic mentoring programs select mentors from a helping profession and provide additional training and supervision from trained mental health clinicians to create a more therapeutic setting for mentees (Johnson & Pryce, 2013). Other youth mentoring programs include a therapeutic component by incorporating additional staff consisting of mental health professionals, such as counselors-in-training (CITs), to directly address the mental health needs of mentees and support mentors (Sacco et al., 2014; Stark et al., 2021; Weiler et al., 2013). Therapeutic mentoring programs function as an intervention for youth who are engaging in risky behavior or have experienced trauma and other developmental issues (Johnson & Pryce, 2013; Sacco et al., 2014).

Litam and Hipolito-Delgado (2021) discussed how COVID-19 highlighted that communities of color have limited access to health care and education. Marginalized youth and their families may not seek mental health services at all or may be more prone to accept help from non–mental health professionals such as mentors (Dashiff et al., 2009). Therefore, an ideal youth mentoring program might have trained mentors from a helping profession who are supervised by mental health professionals, such as counselors, who are also available to meet with youth throughout the mentoring sessions. However, many mentoring programs are volunteer-based and this may limit access to mental health professionals. In addition, there is a shortage of mental health professionals prepared to work with youth (Dashiff et al., 2009) and there is a treatment gap for mental disorders in children (Patel et al., 2013).

Often youth have access to counselors in their schools, but researchers have found that school counselors report that they have limited time to address ongoing mental health needs (Carlson & Kees, 2013). Litam and Hipolito-Delgado (2021) encouraged counselors to use creative strategies such as reduced or no-cost services when working with communities of color. Dashiff and colleagues (2009) stressed that “innovative strategies of service delivery are needed” when working with youth who may come from poverty or areas with limited access to mental health services (p. 29). Partnering with a university, with a plethora of CITs needing supervised client hours, is an innovative and low- or no-cost approach. In this scenario, the mentor takes on a therapeutic role with their mentee, but the CIT is available to address and process ongoing mental health concerns. Incorporating CITs in a youth mentoring program allows both mentor and CIT to work together to create an environment in which youth feel safe, encompassing a secure attachment to the therapeutic program (Sacco et al., 2014).

The CIT’s position facilitates insight and awareness for the youth while offering tools that will help them reach their therapeutic goals (Johnson & Pryce, 2013; Sacco et al., 2014). The role of the mentor is to serve as a role model and advocate while maintaining open communication with the CIT to facilitate necessary therapeutic modifications (Sacco et al., 2014). Some researchers have found that as the mentor models healthy behavior, the youth will eventually begin to display a healthier interpersonal and intrapersonal self (Johnson & Pryce, 2013; Sacco et al., 2014). Overall, mentoring programs appear to be an effective intervention for youth that could also benefit from the incorporation of a therapeutic component.

Despite the amount of research being done to understand the relationship between mentor and mentee from different perspectives, there is less data that examines the participants’ lived experiences of a therapeutic youth mentoring program that includes CITs. The purpose of this study was to examine and gain further insight into participants’ lived experiences with a therapeutic youth mentoring program—specifically, a therapeutic youth mentoring program in which the mentors had additional training and supervision in mental health areas and additional support was provided by CITs while under supervision. The overarching question for this study was: What were participants’ lived experiences prior to and after participating in a therapeutic youth mentoring program?

Methodology

Phenomenology was utilized in this study to gather and analyze data in order to better understand participants’ lived experiences in a therapeutic youth mentoring program. According to Trusty (2011), “if little is known about a research area or target population, it is likely that a qualitative study would be needed first” (p. 262). Although some research has been conducted with participant perceptions of youth mentoring programs, there is less research with therapeutic mentoring programs; therefore, a qualitative approach was deemed appropriate.

Therapeutic Youth Mentoring Program

The therapeutic youth mentoring program in this study was at a university in the Rocky Mountain region of the United States and utilized the theoretical framework of Campus Corps (Weiler et al., 2013, 2014), now called Campus Connections (CC). CC is an innovative licensed program combining practices from mentoring, after-school programming, and integrated mental health. CC mentors were recruited and selected from a variety of undergraduate disciplines across campus, with more than half being from counseling and human services, psychology, or education majors. All mentors attended an orientation and background screening prior to being accepted for the program. The mentors who were selected spent the first 3 weeks of the semester in intensive training with counselor educators, who were also licensed professional counselors, to learn about child abuse reporting, ethics of working with minors, crises and trauma, and basic counseling skills. Potential mentees were referred by local school counselors and attended an intake with their guardians to go over the format of the program. Mentors created profiles about themselves that were utilized during the intake so that mentees could select their mentor based on preferences.

Once mentees were paired with mentors, the faculty and staff looked at the information provided by caregivers and counselors, demographics, and other relevant information to create diverse mentor families. Each mentor family consisted of approximately three mentor/mentee pairs. In this study, there were a total of three mentor families and each family was assigned a mentor coach. The mentor coaches were graduate-level counseling students who provided their mentor family with support throughout the semester. In addition, four graduate-level CITs were selected to provide ongoing counseling to mentees throughout the therapeutic mentoring program. All CITs were in their last semester of graduate studies and met weekly with counselor educators for supervision. Two counselor educators and supervisors, also licensed professional counselors, were also present each evening of CC to support mentees, mentors, and CITs.

All youth participated in the 12-week CC therapeutic youth mentoring program that met on the university campus, once a week for 4 hours. This therapeutic youth mentoring program was designed to bring youth to a college campus to help them become more comfortable and familiar with future college and career goals. Youth followed a schedule that consisted of:

- working for 60 minutes with their mentor on academic and study skills.

- going on a 30-minute “walk and talk” to learn about different locations on the university campus each week.

- participating in a 30-minute family-style meal at the dining hall with their mentor family.

- choosing two 45-minute prosocial or social justice activities.

The prosocial and social justice activities were directed at helping youth learn skills and concepts such as resiliency, coping, inclusiveness, and empathy. These activities were adapted from a manual created by the founders of CC. Each evening, two 45-minute lessons were facilitated by our graduate assistants and CITs and covered topics around the “Big 8” identities (i.e., gender/sex, race, class/socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, ethnicity, religion, age, and ability). Some examples of the activities included: Backpack, an activity adopted from Peggy Mcintosh’s (2003) The Knapsack, that examines privilege and societal benefits; Build a House, an activity designed to illustrate the differences in resources that people have based on socioeconomic status; and Pink, Blue and Purple, an activity designed to discuss assumptions made about gender.

At any point throughout their time on campus, mentors or mentees could request for the youth to have time to meet with a CIT. CITs also routinely set up check-ins with all mentees and were present throughout the entire process. Often the CITs would help with the after-dinner activities if youth weren’t requesting to meet 1:1. The participants in this study engaged in a total of 720 minutes of counseling with the average youth receiving 50 minutes of individual counseling.

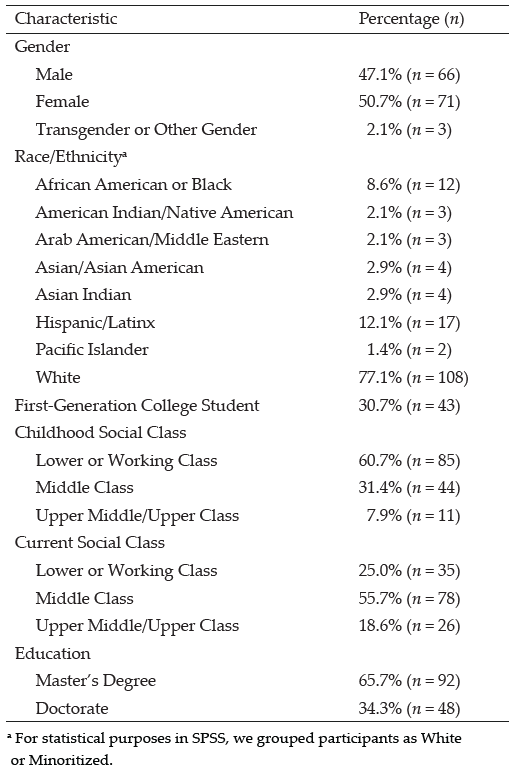

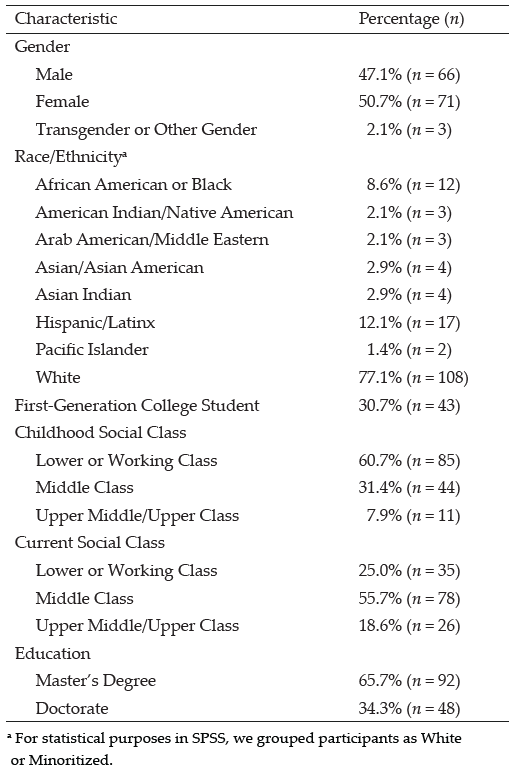

Participants

This was a purposeful sample of at-promise youth participating in the same CC therapeutic youth mentoring program in the spring of 2019. Of the 18 youth enrolled in CC, 14 youth agreed to participate in the research study. The participants in this study consisted of 14 youth, ages 11–15, with the following demographics: 71% male, 21% female, and 7% transgender/gender-expansive; 57% White, 29% Black/African American, 21% Hispanic/Latino, 14% American Indian/Alaska Native, and 7% Asian; and approximately half on free and reduced lunch. School district partners were asked to consider and recommend at-promise youth if they were not reaching their full potential and might be vulnerable to school dropout, substance use/misuse, and/or criminal behavior. Local school counselors submitted referrals based on this criterion for youth to participate in CC. Participation was voluntary and participants could remove themselves from the study at any time throughout the process.

Procedures

At-promise youth are considered a vulnerable population and therefore researchers must contemplate ethical considerations. Our research team went through a full IRB process to ensure youth participants were being treated with the highest ethical considerations. After obtaining IRB approval, informed consent and assent was secured and two audiotaped interviews were conducted with all participants—one at the beginning of the 12-week mentoring program and one 12 weeks later at the end. Semistructured interviews are progressive in design (Merriam, 1998); they allow the researcher to formulate questions ahead of time and adjust the questions based on the participants’ responses (Guba & Lincoln, 1989). Participants were asked a series of open-ended questions that were similar across interviews, such as how a mentor has helped them, their feelings about being on a college campus, and thoughts on meeting with a CIT (see Appendix for a complete list of interview questions). The final interview allowed the participants to describe their experience working with a mentor and CIT and their perceptions of meeting on a university campus each week for 12 weeks.

Our research team consisted of three PhD-level counselor educators, Diane Stutey, Lori Notestine, and Joseph Wehrman; one counselor education doctoral student, Kim Severn; one staff member in master’s-level student affairs and higher education, Molly Cammell; and two graduate students in counseling, Abigail E. Solis and Kodi L. Enkler. All members of the research team were present throughout the 12-week therapeutic youth mentoring program. We met on a regular basis to discuss the research protocol and any potential conflicts of interest or ethical concerns, ensuring trustworthiness of the study.

Data Analysis and Trustworthiness

All data were collected by the research team and Solis transcribed all the interviews. Data were analyzed and independently coded by Stutey, Solis, and Severn, utilizing Merriam’s (1998) two-level approach. After each researcher independently coded all the transcripts, we met to discuss and agree upon emerging themes. After data was further analyzed and organized to support each of the themes, we met again to come to consensus on the themes. Any disagreement of themes or supporting data was discussed until consensus was reached.