Nov 29, 2018 | Volume 8 - Issue 4

Joshua D. Smith, Neal D. Gray

This interview is the third in the Lifetime Achievement in Counseling Series at TPC that presents an annual interview with a seminal figure who has attained outstanding achievement in counseling over a career. Many people are deserving of this recognition, but I am happy that Josh Smith and Dr. Neal Gray have interviewed a visionary in the counseling profession. I first became aware of Dr. Capuzzi over 30 years ago when I was reading his vast research and scholarship as I prepared to teach my first classes as a counselor educator. Over the years, I have been amazed at Dr. Capuzzi’s contribution to the profession and his impact on countless educators, clinicians, and supervisors. I appreciate Josh Smith and Neal Gray for accepting my editorial assignment to interview Dr. Capuzzi. What follows are thought-provoking reflections from a counseling icon and leader.

—J. Scott Hinkle, Editor

David Capuzzi, PhD, NCC, LPC, is past President of the American Counseling Association (ACA), and past Chair of both the ACA Foundation and the ACA Insurance Trust. Currently, Dr. Capuzzi is a member of the senior core faculty in community mental health counseling at Walden University and professor emeritus at Portland State University. Previously, he served as an affiliate professor in the Department of Counselor Education, Counseling Psychology, and Rehabilitation Services at Pennsylvania State University, and as Scholar in Residence in counselor education at Johns Hopkins University.

David Capuzzi, PhD, NCC, LPC, is past President of the American Counseling Association (ACA), and past Chair of both the ACA Foundation and the ACA Insurance Trust. Currently, Dr. Capuzzi is a member of the senior core faculty in community mental health counseling at Walden University and professor emeritus at Portland State University. Previously, he served as an affiliate professor in the Department of Counselor Education, Counseling Psychology, and Rehabilitation Services at Pennsylvania State University, and as Scholar in Residence in counselor education at Johns Hopkins University.

From 1980 to 1984, Dr. Capuzzi was editor of The School Counselor. He has authored several textbook chapters and monographs on the topic of preventing adolescent suicide and is coeditor and author with Dr. Larry Golden of Helping Families Help Children: Family Interventions with School-Related Problems (1986) and Preventing Adolescent Suicide (1988). He coauthored and edited with Douglas R. Gross numerous editions of Introduction to Group Work (2010); Counseling and Psychotherapy: Theories and Interventions (2011); Introduction to the Counseling Profession (2013); and Youth at Risk: A Prevention Resource for Counselors, Teachers, and Parents (2019).

In addition to several editions of Foundations of Addictions Counseling with Dr. Mark Stauffer, he and Dr. Stauffer have published Foundations of Couples, Marriage and Family Counseling (2015); Human Growth and Development Across the Life Span: Applications for Counselors (2016); and Counseling and Psychotherapy: Theories and Interventions (2016). Other texts include Approaches to Group Work: A Handbook for Practitioners (2003), Suicide Across the Life Span (2006), and Sexuality Counseling (2002), the last coauthored and edited with Larry Burlew. Additionally, Dr. Capuzzi has authored or coauthored articles in a number of ACA division journals.

A frequent speaker at professional conferences and institutes, Dr. Capuzzi has consulted with a variety of school districts and community agencies interested in initiating prevention and intervention strategies for adolescents at risk for suicide. He has facilitated the development of suicide prevention, crisis management, and postvention programs in communities throughout the United States; provided training on the topics of at-risk youth, grief, and loss; and served as an invited adjunct faculty member at other universities as time permits.

An ACA Fellow, Dr. Capuzzi is the first recipient of ACA’s Kitty Cole Human Rights Award and also is a recipient of the Leona Tyler Award in Oregon. In 2010, he received ACA’s Gilbert and Kathleen Wrenn Award for a Humanitarian and Caring Person. In 2011, he was named to the Distinguished Alumni of the College of Education at Florida State University and, in 2016, he received the Locke/Paisley Mentorship Award from the Association for Counselor Education and Supervision. In 2018 he received the Mary Smith Arnold Anti-Oppression Award from the Counselors for Social Justice, a division of ACA, as well as the U.S. President’s Lifetime Achievement Award.

In this interview, Dr. Capuzzi responded to six questions about his career, his impact on the counseling profession, and his thoughts about the current state and future of the counseling profession.

- Counseling has made substantial progress during the time you have been a member of the profession. In your opinion, what are the three major accomplishments of the profession?

I joined ACA in 1965, when it was known as the American Personnel and Guidance Association, and there was no such thing as counselor licensure. Although there were many excellent master’s and doctoral programs, there also were many that did not require much coursework to practice as a counselor. There were some university programs that only required 15 or so semester credits as part of a master’s degree in education to be able to seek employment as a counselor. Master’s degrees in counseling were one-year programs requiring 36 to 39 semester credits. There was little standardization of coursework requirements until licensure requirements were gradually adopted state by state. Today, all 50 states have counselor licensure, which has been instrumental in the progression of the counseling profession, and I see this as a major accomplishment.

The development of the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) has provided the profession with assurances that graduates of CACREP-accredited programs meet standards that elevate best practices when working with clients. CACREP accreditation has assisted universities by providing them with support for curriculum revision and improvement and impacted the requirements of the state professional counselor licensing boards.

There was little interest or emphasis on the importance of the inclusion of diverse populations, personalities, lifestyles, and cultures through most of the 1980s, even though the United States has always been a melting pot for immigrants from around the world. The affirmation of differences and the richness that diverse points of view add to our country’s tapestry has been slow to develop, and ACA has made major contributions in this area.

- Which of these major accomplishments was the most difficult to achieve for the counseling profession and why?

The acceptance of diverse populations, personalities, lifestyles, and cultures was the most difficult to achieve. Quite often, over the years, members of diverse populations have not been at the forefront of the profession, not because of lack of astuteness or competence, but because they have not been able to assume elected leadership positions. I am thankful that this is changing and affirm that this development is an asset-based characteristic of the counseling profession. I am so thankful that individuals such as Thelma T. Daley, Beverly O’Bryant, Courtland Lee, Marie Wakefield, Patricia Arredondo, Thelma Duffey, Cirecie West-Olatunji, and Marcheta Evans (and others I am probably forgetting to mention) have been willing to run for and serve in the ACA presidency position because their contributions have been stellar and essential to the maturation of the profession of counseling.

- What do you consider to be your major contribution to the development of the counseling profession and why?

I am relatively certain that I was the first ACA President to establish a diversity theme for the year that I was ACA President. My theme for 1986–1987 was Human Rights and Responsibilities: Developing Human Potential, even though colleagues and friends advised me against naming it in this manner as part of my platform for fear I would lose the election. I decided I should identify a diversity agenda as part of my pre-election platform statement because I wanted members to understand what I stood for in advance of the voting process. During my ACA presidency, I contacted all the editors of our counseling journals and requested that they consider developing special editions focused on some aspect of diversity. I think there were 16 special issues of division journals during my year as immediate past president that were diversity focused. Additionally, the opening session of the annual conference focused on diversity and human rights vignettes (presented by actors) to set the tone for the conference.

Few people know that my early years living in a mining town in Western Pennsylvania provided the backdrop for my interest in diversity and its importance. Many immigrants from other countries settled in Western Pennsylvania, and I spent the first 10 years of my life hearing three or four languages being spoken daily (newcomers could get jobs in the mines and mills, prior to learning much English, and therefore support their families). When my family left the region and moved south, I was surprised to learn that the America I experienced early in life was not typical of the rest of our country. I also was shocked when some of my classmates told me their parents wanted them to check to make sure I was not Jewish (if I was, they could not be my friends), and I was questioned about why I looked so different. When I asked what that meant I was told that most people they knew were tall, blond, and tanned. This early set of life experiences made an indelible impression, precipitated my ACA theme for 1986–87, and has stayed with me to this day.

- What three challenges to the counseling profession as it exists today concern you most, and what needs to change for these three concerns to be successfully resolved?

First, there is a lack of grassroots input to the ACA President and membership of the ACA Governing Council. During recent years, the membership in the state branches and divisions of ACA has declined and there has not been the amount of input and suggestions for agenda items at meetings of the Governing Council as in the past. For a variety of reasons and from time to time, ACA staff and leaders have not always been able to garner needed input and suggestions. Every effort needs to be made to reach out to grassroots members and identify and affirm their concerns based on the philosophy that the role of an elected leader or ACA staff member is to serve the wishes of those who are depending on their leadership.

Second, there is a lack of membership growth in ACA. In 1986, there were 55,000 members of ACA and our battle cry was “60,000—yes we can.” Currently, the association still has about the same number of members. I think grassroots members need to be re-engaged and encouraged to participate in local projects as well as ACA leadership and governance so that interest and involvement, and subsequently membership, can be reinvigorated.

Lastly, the composition of the Governing Council needs changing. Currently, there are more members of ACA who do not belong to ACA divisions than members who do belong to divisions. Yet, the composition of the Governing Council is still based on a model developed several decades ago when divisional membership was very strong and those seated “around the table,” so to speak, were primarily divisional representatives. Now that the composition of the membership has changed, I think there should be a large proportion of seated representatives for the membership at large. Granted, divisions would still need to be represented and seated, but possibly several divisions could be represented by a single member of the Governing Council if collaboration could occur.

- Assuming some challenges will get resolved and others will not, what do you think the counseling profession will look like 20 years from now?

I believe a revised governance structure of ACA, including membership on the Governing Council, will emerge. Perhaps the structure comprised of state branches, regions, and divisions will no longer exist as we now know it, and another way of organizing to insure input and renewed interest in grassroots participation will replace it to increase ACA membership numbers. The continued development of licensure portability and reciprocity across states could enhance the unification of the profession and encourage more interdisciplinary collaboration.

Accreditation and CACREP standards will continue, but hopefully with more tolerance and affirmation options for adult learners seeking specialization options. Currently, there is not much leeway in decision making regarding coursework. Also related, the increased acceptance of online counselor education programs will occur, as well as more clearly articulated requirements and expectations for online counseling.

Lastly, there is increased interest in the importance of advocacy and social justice on the part of ACA and its members. Universal acceptance and affirmation of the importance of diverse populations, personalities, lifestyles, and cultures as they contribute, not only to the profession, but also to the fabric and strength of democracy in the United States, will continue to be at the forefront of what we do.

- If you were advising current counseling leaders, what advice would you give them about moving the counseling profession forward?

First, never forget that your role is to listen to those who elected or appointed you, because your role is to serve members of the counseling profession and advocate for their best interests. Second, even though those elected to represent divisions on the Governing Council have the responsibility to articulate and explain the wishes of their division, in the end, the outcome of decisions made by the Governing Council must reflect what is best for ACA and the counseling profession. Third, although it is always appropriate for those serving in elected positions within ACA to put forward their ideas for changes, initiatives, or innovations, it is never reasonable to expect such agendas to be adopted unless they truly reflect the interests and wishes of those being served through the leadership position.

This concludes the third interview for the annual Lifetime Achievement in Counseling Series. TPC is grateful to Joshua Smith, NCC, and Dr. Neal Gray for providing this interview. Joshua Smith is a doctoral student in counselor education and supervision at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. Neal D. Gray is a professor and Chair of the School of Counseling at Lenoir-Rhyne University. Correspondence can be emailed to Joshua Smith at jsmit643@uncc.edu.

Nov 29, 2018 | Volume 8 - Issue 4

Michael T. Kalkbrenner, Edward S. Neukrug

The primary aim of this study was to cross-validate the Revised Fit, Stigma, & Value (FSV) Scale, a questionnaire for measuring barriers to counseling, using a stratified random sample of adults in the United States. Researchers also investigated the percentage of adults living in the United States that had previously attended counseling and examined demographic differences in participants’ sensitivity to barriers to counseling. The results of a confirmatory factor analysis supported the factorial validity of the three-dimensional FSV model. Results also revealed that close to one-third of adults in the United States have attended counseling, with women attending counseling at higher rates (35%) than men (28%). Implications for practice, including how professional counselors, counseling agencies, and counseling professional organizations can use the FSV Scale to appraise and reduce barriers to counseling among prospective clients are discussed.

Keywords: barriers to counseling, FSV Scale, confirmatory factor analysis, attendance in counseling, factorial validity

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), mental health disorders are widespread, with over 300 million people struggling with depressive disorders, 260 million living with anxiety disorders, and hundreds of millions having any of a number of other mental health disorders (WHO, 2017, 2018). The symptoms of anxiety and depressive disorders can be dire and include hopelessness, sadness, sleep disturbances, motivational impairment, relationship difficulties, and suicide in the most severe cases (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Worldwide, one in four individuals will be impacted by a mental health disorder in their lifetime, which leads to over a trillion dollars in lost job productivity each year (WHO, 2018). In the United States, approximately one in five adults has a diagnosable mental illness each year, and about 20% of children and teens will develop a mental disorder that is disabling (Centers for Disease Control, 2018).

Substantial increases in mental health distress among the U.S. and global populations have impacted the clinical practice of counseling practitioners who work in a wide range of settings, including schools, social service agencies, and colleges (National Institute of Mental Health, 2017; Twenge, Joiner, Rogers, & Martin, 2017). Identifying the percentage of adults in the United States who attend counseling, as well as the reasons why many do not, can help counselors develop strategies that can make counseling more inviting and, ultimately, relieve struggles that people face. Although perceived stigma and not having health insurance have been associated with reticence to seek counseling (Han, Hedden, Lipari, Copello, & Kroutil, 2014; Norcross, 2010; University of Phoenix, 2013), the literature on barriers to counseling among people in the United States is sparse. Appraising barriers to counseling using a psychometrically sound instrument is the first step toward counteracting such barriers and making counseling more inviting for prospective clients. Evaluating barriers to counseling, with special attention to cultural differences, has the potential to help understand differences in attendance to counseling and can help develop mechanisms that promote counseling for all individuals. This is particularly important as research has shown that there are differences in help-seeking behavior as a function of gender identity and ethnicity (Hatzenbuehler, Keyes, Narrow, Grant, & Hasin, 2008).

Attendance in Counseling by Gender and Ethnicity

Previous investigations on attendance in counseling indicated that 15–38% of adults in the United States had sought counseling at some point in their lives (Han et al., 2014; University of Phoenix, 2013), with discrepancies in counselor-seeking behavior found as a function of gender and ethnicity (Han et al., 2014; Lindinger-Sternart, 2015). For instance, women are more likely to seek counseling compared to men (Abrams, 2014; J. Kim, 2017). In addition, individuals who identify as White tend to seek personal counseling at higher rates compared to those who identify with other ethnic backgrounds (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2008; Seidler, Rice, River, Oliffe, & Dhillon, 2017). Parent, Hammer, Bradstreet, Schwartz, and Jobe (2018) examined the intersection of gender, race, ethnicity, and poverty with help-seeking behavior and found the income-to-poverty ratio to be positively related to help-seeking for White males and negatively associated for African American males. In other words, as White males gained in income, they were more likely to seek counseling, whereas the opposite was true for males who identified as African American (Parent et al., 2018).

Barriers to Mental Health Treatment and Attendance in Counseling

Despite the fact that large numbers of individuals in the United States and worldwide will develop a mental disorder in their lifetime, two-thirds of them will avoid or do not have access to mental health treatment (WHO, 2018). In wealthier countries, there is one mental health worker per 2,000 people (WHO, 2015); however, in poorer countries, this drops to 1 in 100,000, and such disparities need to be addressed (Hinkle, 2014; WHO, 2015). Although the lack of attendance in counseling and related services in poorer countries is explained by lack of services, in the United States and other wealthy countries, the availability of mental health services is relatively high, and the lack of attendance is usually explained by other reasons (Neukrug, Kalkbrenner, & Griffith, 2017; WHO, 2015). Research on the lack of attendance in counseling by the general public shows adults in the United States might be reticent to seek counseling because of perceived stigma, financial burden, lack of health insurance, uncertainty about how to find a counselor, and suspicion that counseling will not be helpful (Han et al., 2014; Norcross, 2010; University of Phoenix, 2013).

Appraising Barriers to Counseling

The quantification and appraisal of barriers to counseling is a nuanced and complex construct to measure and has been previously assessed with populations of mental health professionals and with counseling students (Kalkbrenner & Neukrug, 2018; Kalkbrenner, Neukrug, & Griffith, in press; Neukrug et al., 2017). Knowing that personal counseling is a valuable self-care strategy for mental health professionals (Whitfield & Kanter, 2014), Neukrug et al. (2017) developed the original version of the Fit, Stigma, & Value (FSV) Scale, which is comprised of three latent variables, or subscales, of barriers to counseling for human service professionals: fit (the degree to which one trusts the process of counseling), stigma (hesitation to seek counseling because of feelings of embarrassment), and value (the extent to which a respondent thinks that attending personal counseling will be beneficial). Kalkbrenner et al. (in press) extended and validated a revised version of the FSV Scale with a sample of professional counselors, and Kalkbrenner and Neukrug (2018) validated the Revised FSV Scale with a sample of counselor trainees. Although the FSV Scale appears to have utility for appraising barriers to counseling among mental health professionals (Neukrug et al., 2017; Kalkbrenner et al., in press) the factorial validity of the measure has only been tested with helping professionals and counseling students. The appraisal of barriers to seeking counseling among adults in the United States is an essential first step in understanding why prospective clients do, or do not, seek counseling. If validated, researchers and practitioners can potentially use the results of the Revised FSV Scale to aid in the early identification of specific barriers and to inform the development of interventions geared toward reducing barriers to counseling among adults in the United States. Thus, we sought to answer the following research questions (RQs): RQ 1: Is the three-dimensional hypothesized model of the Revised FSV scale confirmed with a stratified random sample of adults in the United States? RQ 2: To what extent do adults in the United States attend counseling? RQ 3: Are there demographic differences to the FSV barriers among adults in the United States?

Method

The psychometric properties of the Revised FSV Scale were tested with a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) based on structural equation modeling (RQ 1). Descriptive statistics were used to compute participants’ frequency of attendance in counseling (RQ 2). A factorial multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was computed to investigate demographic differences in respondents’ sensitivity to the FSV barriers (RQ 3). A minimum sample size of 320 (10 participants for each estimated parameter) was determined to be sufficient for computing a CFA (Mvududu & Sink, 2013). An a priori power analysis was conducted using G*Power to determine the sample size for the factorial MANOVA (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007). Results revealed that a minimum sample size of 269 would provide an 80% power estimate (α = .05), with a moderate effect size, f 2 = 0.25 (Cohen, 1988).

Participants and Procedures

After obtaining IRB approval, an online sampling service (Qualtrics, 2018) was contracted to survey a stratified random sample (stratified by age, gender, and ethnicity) of the general U.S. population based on the 2016–2017 census data. A Qualtrics project management team generated a list of parameters and sample quota constraints for data collection. Once the researchers reviewed and confirmed these parameters, a project manager initiated the stratified random sampling procedure and data collection by sending an electronic link to the questionnaire to prospective participants. A pilot study was conducted using 41 participants and no formatting or imputation errors were found. Data collection for the main study was initiated and was completed in less than one week.

A total of 431 individuals responded to the survey. Of these, 21 responses were omitted because of missing data, yielding a useable sample of 410. Participants ranged in ages from 18 to 84 (M = 45,

SD = 15). The demographic profile included the following: 52% (n = 213) identified as female, 44%

(n = 181) as male, 0.5% (n = 2) as transgender, and 3.4% (n = 14) did not specify their gender. For ethnicity, 63% (n = 258) identified as White, 17% (n = 69) as Hispanic/Latinx, 12% (n = 49) as African American, 5% (n = 21) as Asian, 1% (n = 5) as American Indian or Alaska Native, 0.5% (n = 2) as Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and 1.5% (n = 6) did not specify their ethnicity. For highest degree completed, 1% (n = 5) held a doctoral degree, 7% (n = 29) held a master’s degree, 24% (n = 98) held a bachelor’s degree, 16% (n = 65) had completed an associate degree, 49% (n = 199) had a high school diploma, and 3% (n = 14) did not specify their highest level of education. Eighty-four percent (n = 343) of participants had health insurance at the time of data collection. The demographic profile of our sample is consistent with those found in recent surveys of the general U.S. population (Lumina Foundation, 2017; U.S. Census Bureau, 2017).

Instrumentation

Using the Qualtrics e-survey platform (Qualtrics, 2018), participants were asked to respond to a series of demographic questions as well as the Revised FSV Scale.

Demographic questionnaire. Participants responded to a series of demographic items about their age, ethnicity, gender, highest level of education completed, and if they had health insurance. They also were asked to indicate if they had ever recommended counseling to another person and if they had ever participated in at least one session of counseling as defined by the American Counseling Association (ACA) in the 20/20: Consensus Definition of Counseling: “counseling is a professional relationship that empowers diverse individuals, families, and groups to accomplish mental health, wellness, education, and career goals” (2010, para. 2).

The FSV Scale. The original version of the FSV Scale contained 32 items that comprise three subscales (Fit, Stigma, and Value) for appraising barriers to counselor seeking behavior (Neukrug et al., 2017). Kalkbrenner et al. (in press) developed and validated the Revised FSV Scale by reducing the number of items to 14 (of the original 32) and confirmed the same 3-factor structure of the scale. The Revised FSV Scale (see Table 1) was used in the present study for temporal validity, as it is more current and because it is likely to reduce respondent fatigue, because it is shorter than the original. The Fit subscale appraises the degree to which one trusts the process of counseling (e.g., item 11: “I couldn’t find a counselor who would understand me.”). The Stigma subscale measures respondents’ hesitation to seek counseling because of feelings of embarrassment (e.g., item 1: “My friends would think negatively of me.”). The Value scale reflects the extent to which a respondent thinks that attending personal counseling will be beneficial (e.g., item 8: “It is not an effective use of my time.”). For each item, respondents were prompted with the stem, “I am less likely to attend counseling because . . . ” and asked to rate each item on a Likert-type scale: 1 (strongly disagree), 2 (disagree), 3 (neither agree or disagree), 4 (agree), or 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores designate a greater sensitivity to each barrier. Previous investigators demonstrated adequate to strong internal consistency reliability coefficients for the Revised FSV Scale: α = .82, α = .91, and α = .78, respectively (Kalkbrenner et al., in press) and α = .81, α = .87, and α = .77 (Kalkbrenner & Neukrug, 2018). Past investigators found validity evidence for the 3-dimensional factor structure of the original and revised versions of the FSV Scale through rigorous psychometric testing (factor analysis) with populations of human services professionals (Neukrug et al., 2017), professional counselors (Kalkbrenner et al., in press), and counseling students (Kalkbrenner & Neukrug, 2018).

Results

CFA

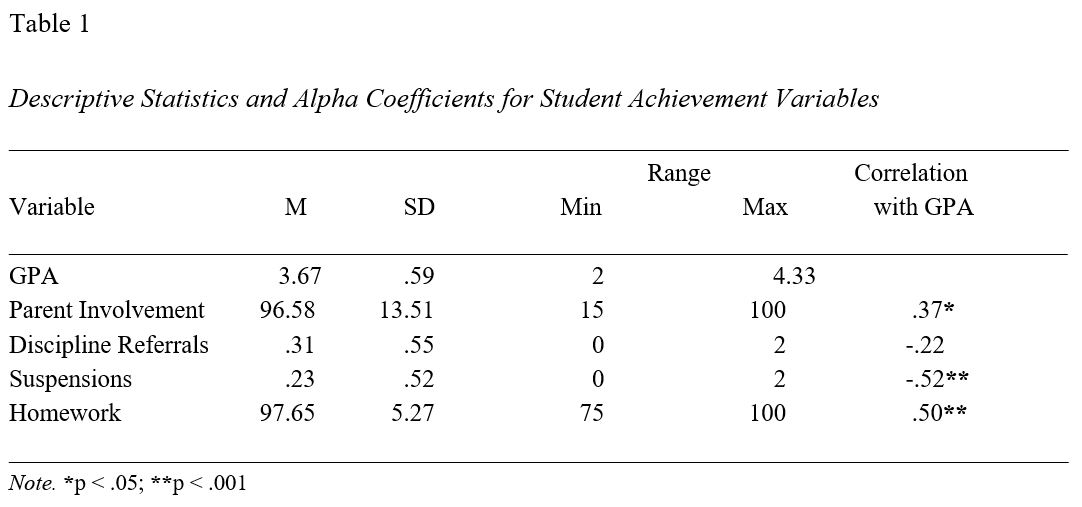

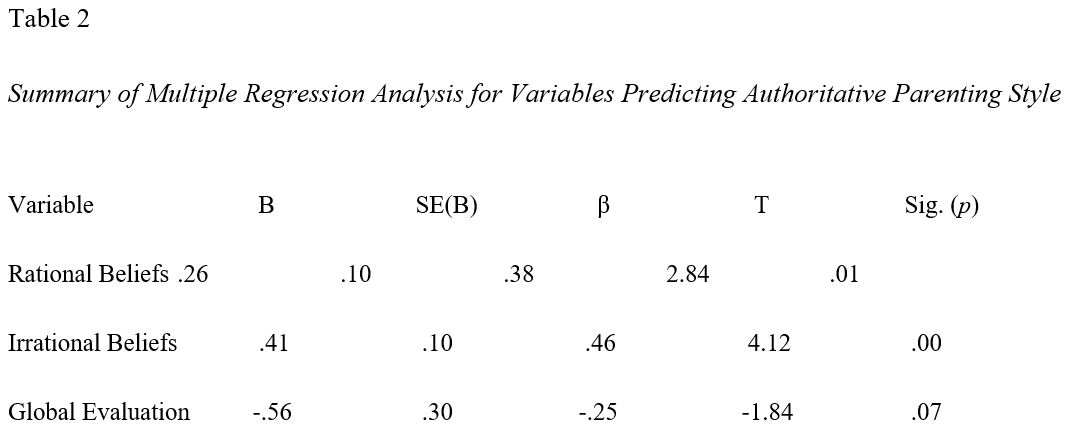

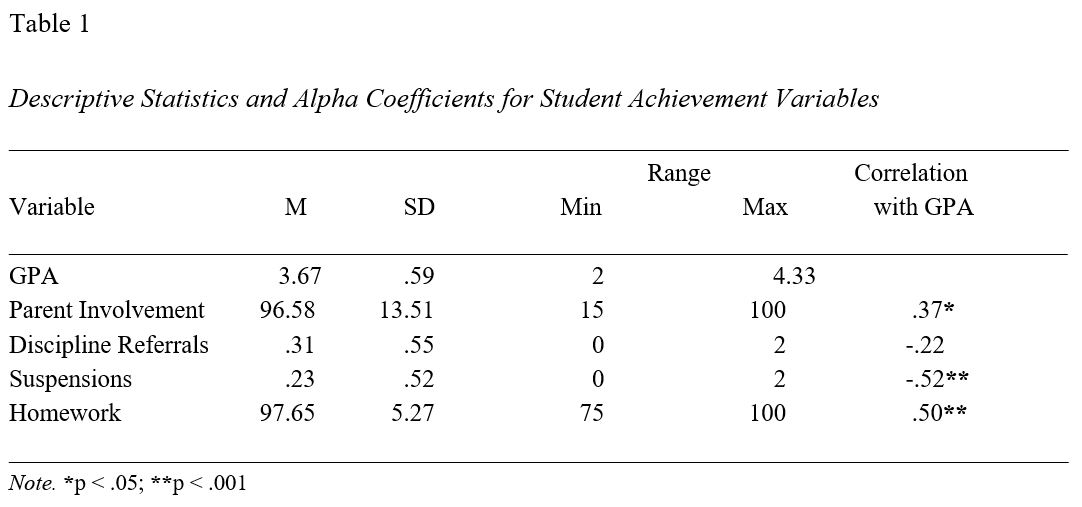

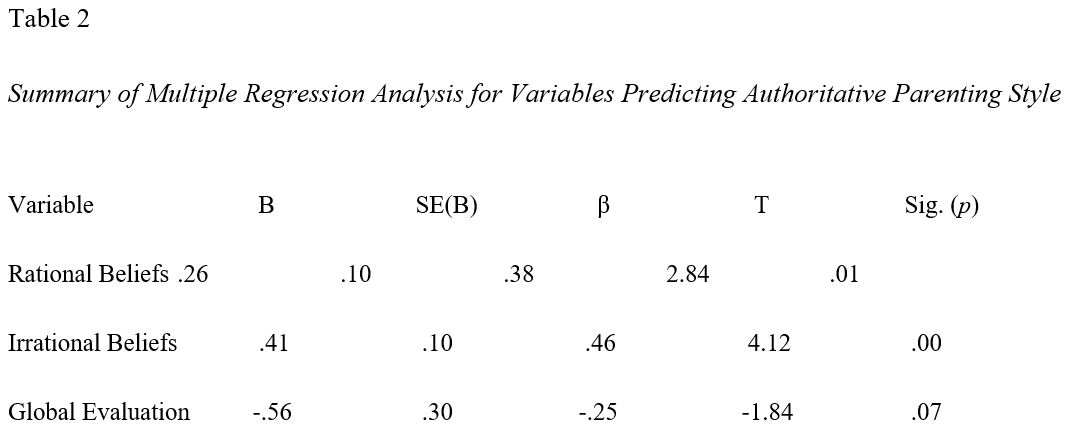

A review of skewness and kurtosis values (see Table 1) indicated that the 14 items on the revised FSV scale were largely within the acceptable range of a normal distribution (absolute value < 1; Field, 2013). Mahalanobis d2 indices showed no extreme multivariate outliers. An inter-item correlation matrix (see Table 2) was computed to investigate the suitability of the data for factor analysis. Inter-item correlations were favorable and ranged from r = 0.42 to r = 0.82 (see Table 2).

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics: The Revised Version of the FSV Scale (N = 410)

| Items |

M |

SD |

Skew |

Kurtosis |

| My friends would think negatively of me. (Stigma) |

2.27 |

1.18 |

0.63 |

-0.50 |

| It would suggest I am unstable. (Stigma) |

2.55 |

1.25 |

0.29 |

-0.97 |

| I would feel embarrassed. (Stigma) |

2.72 |

1.20 |

-0.02 |

-1.00 |

| It would damage my reputation. (Stigma) |

2.43 |

1.20 |

0.41 |

-0.78 |

| It would be of no benefit. (Value) |

2.46 |

1.20 |

0.39 |

-0.71 |

| I would feel badly about myself if I saw a counselor. (Stigma) |

2.35 |

1.13 |

0.45 |

-0.61 |

| The financial cost of participating is not worth the personal benefits. (Value) |

2.61 |

1.18 |

0.25 |

-0.68 |

| It is not an effective use of my time. (Value) |

2.40 |

1.16 |

0.45 |

-0.57 |

I couldn’t find a counselor with my theoretical orientation

(personal style of counseling). (Fit) |

2.42 |

1.12 |

0.62 |

-0.68 |

| I couldn’t find a counselor competent enough to work with me. (Fit) |

2.31 |

1.12 |

0.50 |

-0.47 |

| I couldn’t find a counselor who would understand me. (Fit) |

2.41 |

1.20 |

0.48 |

-0.66 |

| I don’t trust a counselor to keep my matters just between us. (Fit) |

2.50 |

1.21 |

0.33 |

-0.82 |

| Counseling is unnecessary because my problems will resolve naturally. (Value) |

2.56 |

1.31 |

0.22 |

-0.61 |

| I have had a bad experience with a previous counselor in the past. (Fit) |

2.34 |

1.17 |

0.44 |

-0.71 |

Table 2

Inter-Item Correlation Matrix

|

Q1 |

Q2 |

Q3 |

Q4 |

Q5 |

Q6 |

Q7 |

Q8 |

Q9 |

Q10 |

Q11 |

Q12 |

Q13 |

Q14 |

| Q1 |

1 |

0.70 |

0.64 |

0.72 |

0.54 |

0.63 |

0.53 |

0.57 |

0.57 |

0.60 |

0.60 |

0.53 |

0.47 |

0.53 |

| Q2 |

|

1 |

0.76 |

0.72 |

0.51 |

0.61 |

0.52 |

0.54 |

0.55 |

0.58 |

0.60 |

0.57 |

0.42 |

0.46 |

| Q3 |

|

|

1 |

0.68 |

0.51 |

0.64 |

0.54 |

0.53 |

0.53 |

0.55 |

0.58 |

0.57 |

0.50 |

0.43 |

| Q4 |

|

|

|

1 |

0.62 |

0.68 |

0.55 |

0.59 |

0.58 |

0.61 |

0.63 |

0.61 |

0.51 |

0.53 |

| Q5 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

0.67 |

0.58 |

0.69 |

0.52 |

0.59 |

0.59 |

0.48 |

0.57 |

0.49 |

| Q6 |

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

0.58 |

0.68 |

0.59 |

0.68 |

0.69 |

0.60 |

0.56 |

0.48 |

| Q7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

0.72 |

0.60 |

0.60 |

0.57 |

0.58 |

0.59 |

0.53 |

| Q8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

0.64 |

0.66 |

0.68 |

0.61 |

0.64 |

0.54 |

| Q9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

0.71 |

0.71 |

0.61 |

0.56 |

0.57 |

| Q10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

0.82 |

0.65 |

0.56 |

0.56 |

| Q11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

0.65 |

0.52 |

0.58 |

| Q12 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

0.57 |

0.52 |

| Q13 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

0.44 |

| Q14 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

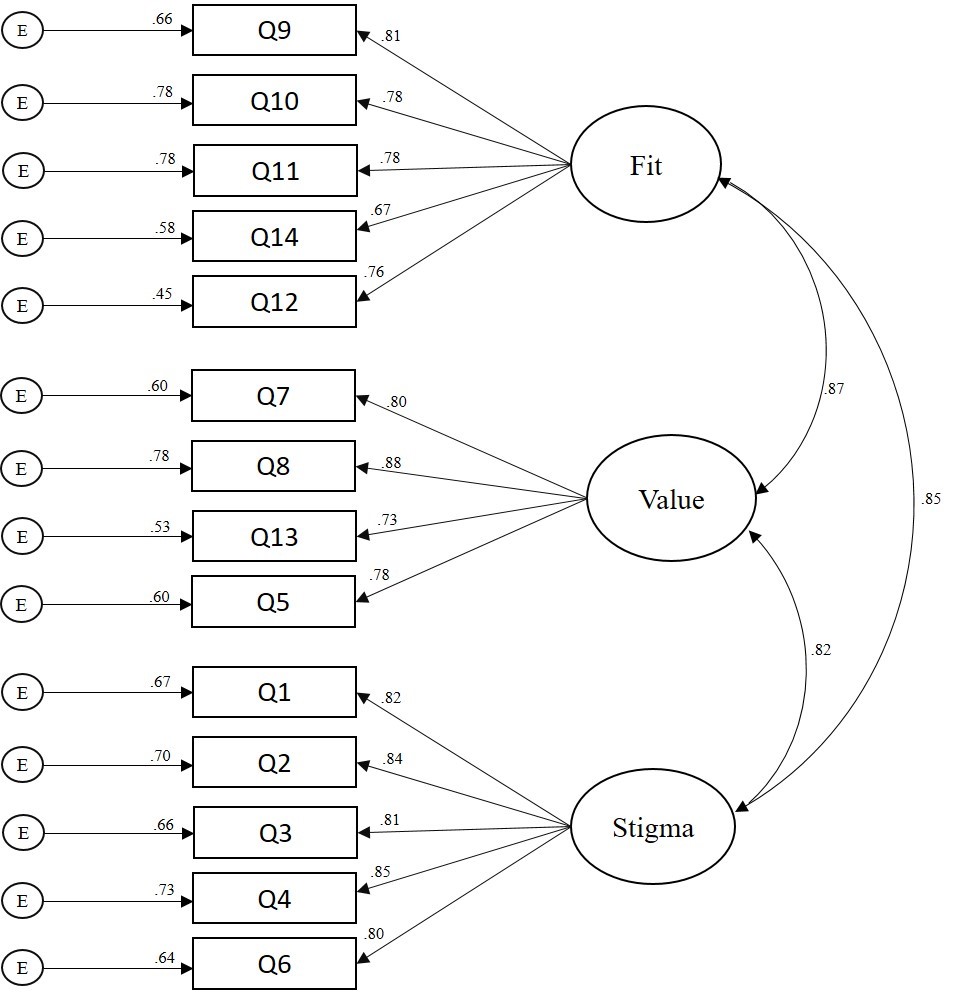

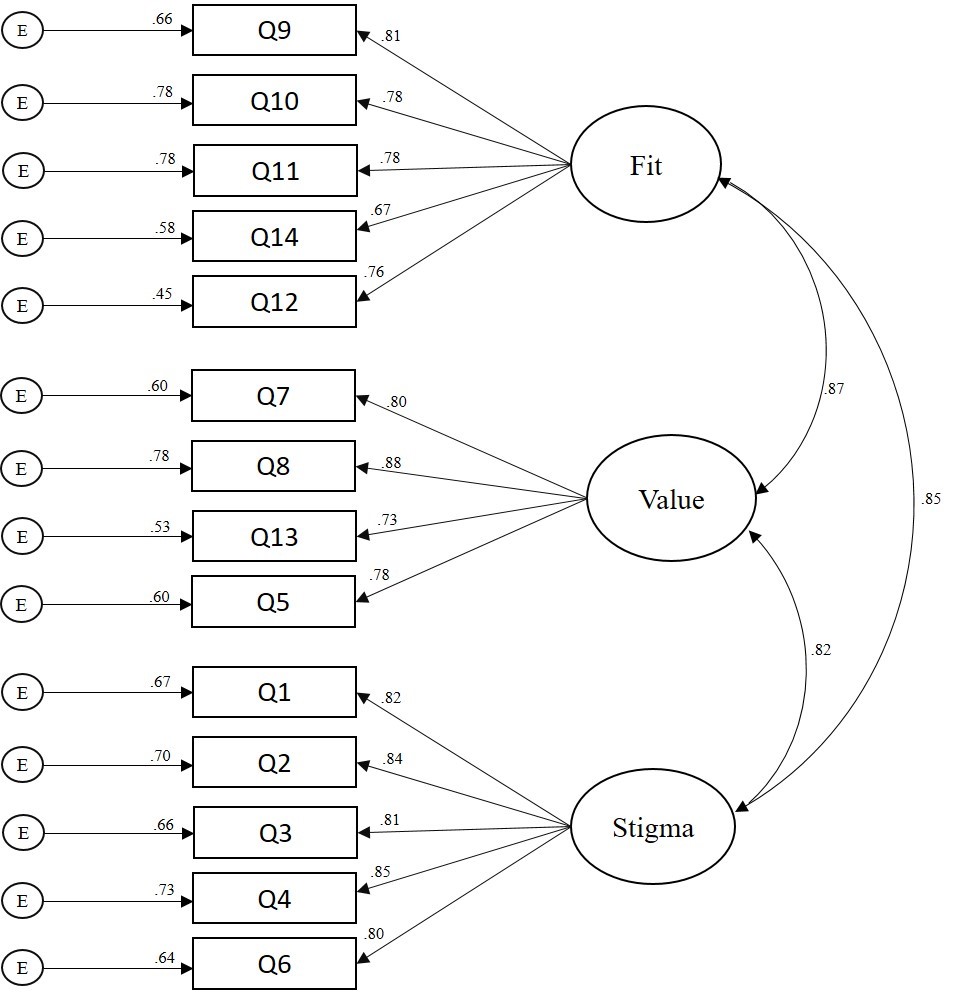

A CFA based on structural equation modeling was computed using IBM SPSS Amos version 25 to test the psychometric properties of the revised 14-item scale with adults in the United States (RQ1). A number of goodness-of-fit (GOF) indices recommended by Byrne (2016) were investigated to determine model fit. The Chi Square CMIN absolute fit index was statistically significant: χ2 (74) = 3.54, p < 0.001. More suitable GOF indices for large sample sizes (N > 200) were examined and revealed adequate model fit: comparative fit index (CFI = .96); root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA = .07); 90% confidence interval [.06, .08]; standardized root mean square residual (SRMR = .038); incremental fit index (IFI = .96); and normed fit index (NFI = .94). Collectively, the GOF indices above demonstrated adequate model fit based on the guidelines provided by Byrne. The path model with standardized coefficients is displayed in Figure 1. Tests of internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s Alpha) revealed strong reliability coefficients for all three FSV subscales: α = .90, α = .91, and α = .87, respectively. An investigation of the path model coefficients (see Figure 1) revealed a moderate to strong association between the FSV barriers. Consequently, researchers computed a follow-up CFA to test if a single-factor model solution for the FSV Scale was a better fit with the data. Results revealed a poor model fit for the single-factor solution, suggesting that retaining the 3-factor model was appropriate for the data.

Figure 1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis Path Model (N = 410)

Figure 1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis Path Model (N = 410)

Frequency and Multivariate Analyses

Of the 374 participants who responded to the item regarding whether they had previously attended counseling, 32% (n = 121) indicated they had. A total of 362 participants specified both their gender and past attendance in counseling. Females’ (n = 199) rate of attendance in counseling was 35% (n = 70) and males’ (n = 163) rate of attendance in counseling was 28% (n = 45). Eleven percent

(n = 45) of participants were attending counseling at the time of data collection.

A factorial 2 (gender) X 2 (attendance in counseling) X 2 (ethnicity) MANOVA was computed to examine demographic differences in participants’ sensitivity to barriers to counseling. All three independent variables had two levels: gender (male or female), attendance in counseling (no previous attendance in counseling or previous attendance in counseling), and ethnicity (White or non-White). Based on the recommendations of Kaneshiro, Geling, Gellert, and Millar (2011), the second level of the ethnicity independent variable, non-White, was aggregated by merging all participants who did not identify as White; this ensured comparable groups for statistical analyses. The dependent variables consisted of respondents’ composite scores on each of the three FSV barriers. Because we were interested in investigating all significant main effects and interaction effects across the univariate and multivariate nature of the data, both MANOVA and follow-up univariate ANOVAs were computed (Field, 2013). Bonferroni corrections were applied to control for the familywise error rate.

A significant main effect emerged for gender: F = (7, 354) = 4.73, p = 0.003, Wilks’ Λ = 0.96, η2p = 0.04. The univariate ANOVAs (see Table 3) revealed significant main effects for all three FSV barriers:

Fit: [F = (7, 354) = 6.26, p = 0.013, η2p = 0.02]; Stigma: [F = (7, 354) = 13.71, p < 0.001, η2p = .04]; and

Value: [F = (7, 354) = 5.52, p = 0.02, η2p = .02]. Males (M = 2.56, M = 2.73, M = 2.60) scored higher than females (M = 2.25, M = 2.24, M = 2.23) on Fit, Stigma, and Value, respectively. A significant multivariate main effect also emerged for attendance in counseling: F = (7, 354) = 3.80, p = 0.01, Wilks’ Λ = 0.97, η2p = 0.031. The univariate ANOVA revealed that participants who had not attended counseling (M = 2.60) scored higher than participants who had attended counseling (M = 2.30) on the Value barrier: F = (7, 354) = 4.65, p = 0.03, η2p = 0.01. There were no other statistically significant main effects or any interaction effects (see Table 3). That is, there were no other significant group differences in respondents’ sensitivity to the FSV barriers by gender, attendance in counseling, or ethnicity.

Discussion

The primary aim of the present study was to validate the revised version of the FSV Scale with adults in the United States. Researchers also investigated the percentage of adults that have attended counseling and examined demographic differences in participants’ sensitivity to barriers to counseling. Frequency analyses revealed that 32% of our sample had attended at least one session of personal counseling, and among those who did, females reported a higher rate of attendance (35%) than males (28%). At the time of data collection, 11% of participants were seeing a counselor. Our findings are largely consistent with previous investigations that suggested 15–38% of adults in the United States had sought counseling at some point in their lives (Hann et al., 2014; University of Phoenix, 2013).

Table 3

Demographic Differences in Sensitivity to Barriers to Counseling

2 (gender) X 2 (attendance in counseling) X 2 (ethnicity) Analysis of Variance

| Independent Variable Barrier |

F |

Sig. |

Partial Eta Squared |

| Gender |

*Fit |

6.26 |

0.01 |

0.02 |

|

|

| **Stigma |

13.71 |

0.00 |

0.04 |

|

|

| *Value |

5.52 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

|

|

| Ethnicity |

Fit |

0.34 |

0.56 |

0.00 |

|

|

| Stigma |

0.00 |

0.96 |

0.00 |

|

|

| Value |

0.11 |

0.74 |

0.00 |

|

|

| Attendance in Counseling |

Fit |

0.69 |

0.41 |

0.00 |

|

|

| Stigma |

0.01 |

0.93 |

0.00 |

|

|

| *Value |

4.65 |

0.03 |

0.01 |

|

|

| Gender X Ethnicity |

Fit |

0.00 |

0.96 |

0.00 |

|

|

| Stigma |

0.12 |

0.73 |

0.00 |

|

|

| Value |

0.14 |

0.71 |

0.01 |

|

|

| Gender X Counseling |

Fit |

1.38 |

0.24 |

0.01 |

|

|

| Stigma |

3.00 |

0.08 |

0.01 |

|

|

| Value |

1.32 |

0.25 |

0.00 |

|

|

| Ethnicity X Counseling |

Fit |

0.07 |

0.79 |

0.00 |

|

|

| Stigma |

0.00 |

0.98 |

0.00 |

|

|

| Value |

0.21 |

0.65 |

0.00 |

|

|

| Gender X Ethnicity X Counseling |

Fit |

0.81 |

0.37 |

0.00 |

|

|

| Stigma |

1.19 |

0.28 |

0.00 |

|

|

| Value |

0.24 |

0.62 |

0.00 |

|

|

df = (1, 354) Note: 0.00 denotes values < 0.01. *Indicates statistical significance at the p < 0.05 level (2-tailed). ** Indicates statistical significance at the p < 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Similar to previous literature on attendance in counseling and congruent with gender theory (Levant, Wimer, & Williams, 2011; Seidler et al., 2017; Vogel, Heimerdinger-Edwards, Hammer, & Hubbard, 2011), we found that males were less likely to seek counseling and were particularly susceptible to the Stigma, Fit, and Value barriers when compared to females. Susceptibility to the Stigma barrier suggests that men might be less likely to attend counseling because of feelings of shame or embarrassment (Cheng, Kwan, & Sevig, 2013; Cheng, Wang, McDermott, Kridel, & Rislin, 2018; J. E. Kim, Saw, & Zane, 2015). Males also reported a higher sensitivity to the Fit and Value barriers as compared to women, suggesting they might place less worth on the anticipated benefits of counseling, and if they were to enter counseling, they may be particularly concerned about finding a counselor with whom they are compatible. It is possible that men’s sensitivity to all FSV barriers may simply be related to their underutilization of counseling services when compared to women, although other explanations also might be plausible.

Consistent with Kalkbrenner et al. (in press), we found that independent of gender, participants who had not attended at least one session of personal counseling placed less value on its potential benefits as compared to those who had attended counseling. This finding suggests that to some extent, attendance in personal counseling might moderate the aforementioned gender differences in participants’ sensitivity to the Value barrier. It is possible that attendance in counseling accounts for a more meaningful amount of the variance in sensitivity to the Value barrier to counseling than gender. Also, consistent with the findings of Kalkbrenner et al. (in press) and Kalkbrenner and Neukrug (2018), we found psychometric support for the factorial validity of the revised version of the FSV scale. Similar to these previous investigations (Kalkbrenner & Neukrug, 2018; Kalkbrenner et al., in press), tests of internal consistency revealed strong reliability coefficients for all three FSV scales. The findings of the present investigators add to the growing body of literature on Fit, Stigma, and Value as three primary barriers to seeking counseling among a variety of populations, including human services professionals (Neukrug et al., 2017), professional counselors (Kalkbrenner et al., in press), counselor trainees (Kalkbrenner & Neukrug, 2018), and now with members of the general U.S. population.

An investigation of the path model coefficients (see Figure 1) revealed moderate to strong associations between the FSV barriers, higher compared to past investigations (Kalkbrenner & Neukrug, 2018; Kalkbrenner et al., in press). A follow-up CFA was computed to test if a single-factor model (aggregated FSV barriers into a single scale) was a better factor solution for the data. However, the follow-up CFA revealed poor model fit for the single factor solution, suggesting that Fit, Stigma, and Value comprise three separate dimensions of a related construct. The differences in the strength of association between the FSV scales in the present study and in the studies by Kalkbrenner et al. (in press) and Kalkbrenner and Neukrug (2018) might be explained by differences between the samples. These investigators validated the FSV barriers with populations of professional counselors and counseling students. It is possible that professional counselors and counseling students were better able to discriminate between different types of barriers to counseling compared to members of the general U.S. population because of the clinical nature of their training. In addition, minor discrepancies are expected in any psychometric study in which authors are attempting to confirm the dimensionality of an attitudinal measure with a new sample (Hendrick, Fischer, Tobi, & Frewer, 2013).

To summarize, the results of internal consistency reliability and CFA indicated that the Revised FSV Scale and its dimensions were estimated adequately with a stratified random sample of adults in the United States. We found close to one-third of our sample had attended counseling, 11% were in counseling at the time of data collection, and there were demographic differences in participants’ sensitivity to barriers to counseling by gender and past attendance in counseling. A number of implications for enhancing counseling practice have emerged from these findings.

Implications for Counseling Practice

With 20% of individuals in the general U.S. population living with a mental disorder, 11% in counseling, 32% having attended counseling, and others wanting counseling but wary of attending, counselors, counseling programs, and counseling organizations can all play a part in reducing the barriers that the public faces when deciding whether or not they should attend counseling. Professional counselors can become leaders in reducing barriers to attending counseling among the general U.S. population through outreach and advocacy. The implications of the following strategies for outreach and advocacy are discussed in the subsequent sub-sections: connecting prospective clients with counselors, interprofessional communication, mobile health, and reducing stigma toward seeking counseling.

Connecting Prospective Clients With Counselors

Nationally, counseling organizations can operate campaigns aimed at reducing the stigma associated with counseling and speaking to its value. The National Board for Certified Counselors (NBCC) advocates for the development and implementation of grassroots community mental health approaches for supporting the accessibility of mental health services on both national and international levels (Hinkle, 2014). Like NBCC, other professional organizations (e.g., ACA and the American Mental Health Counselors Association) might include a directory of professional counselors on their website, along with their specialty areas, who work in a variety of geographic locations to help connect prospective clients with services. On a local level, it is recommended that professional counselors engage in outreach with members of their community to identify the potential unique mental health needs of people in their community and learn about potential barriers to counseling in their local area. Specifically, professional counselors can attend town board meetings and other public events to briefly introduce themselves and use their active listening skills to better understand the needs of the local community. The Revised FSV Scale is one potential tool that professional counselors might use when engaging in outreach with members of their community to gain a better understanding about local barriers to counseling.

We found that participants who had previously attended at least one session of personal counseling reported a higher perceived value of the benefits of counseling compared to those who did not attend counseling. It is possible that individuals’ attendance in counseling is related to their attributing a higher value to the anticipated benefits of counseling. Thus, we suggest community mental health counselors consider offering one free counseling session to promote prospective clients’ attendance in counseling. Just one free session might have the benefit of adding value to a client’s perceived worth of the counseling relationship and increase the likelihood of continued attendance in counseling. Offering one free session may be particularly important for men and minorities, who have traditionally attended counseling at lower rates (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2008; Seidler et al., 2017).

Interprofessional Communication

The flourishing of integrated behavioral health and interprofessional practice across the health care system might provide professional counselors with an opportunity to identify and reduce barriers to seeking counseling among the general U.S. population. In particular, integrated behavioral health involves infusing the delivery of physical and mental health care through interprofessional collaborations or teamwork among a variety of different professionals, thus providing a more holistic model for the patient (Johnson, Sparkman-Key, & Kalkbrenner, 2017). Professional counselors can collaborate with primary care physicians and consider the utility of administering the FSV Scale to patients while they are in the waiting room, as the FSV Scale can be accessed electronically via a tablet or smart phone. We recommend that counseling practitioners reach out to local primary care physicians to discuss the utility of integrated behavioral health and make themselves available to physicians for consultation on how to recognize and refer patients to counseling.

Mobile Health (mHealth)

mHealth refers to the delivery of interventions geared toward promoting physical or mental health by means of a cellular phone (Johnson & Kalkbrenner, 2017). Professional counselors can use mHealth to provide prospective clients with a brief overview of counseling, address prominent barriers to counseling faced by students, and provide mental health resources that are available to students. mHealth might be particularly useful for college and school counselors as academic institutions typically have access to students’ cell phone numbers, and students “appear to be open and responsive to the utilization of mHealth” (Johnson & Kalkbrenner, 2017, p. 323). The campus counseling center is underutilized on some college campuses because of stigma (Rosenthal & Wilson, 2016) and students’ unawareness of the services that are available at the counseling center (Dobmeier, Kalkbrenner, Hill, & Hernández, 2013). College counselors might consider using mHealth as a platform for both reducing stigma toward counselor-seeking behavior and for spreading students’ awareness of the services that are available to them for reduced or no fees at the counseling center.

Reducing Stigma Toward Seeking Counseling

Our results are consistent with the body of evidence indicating that when compared to women, men are less likely to attend counseling, more susceptible to barriers to attending counseling, and more likely to terminate counseling early (Levant et al., 2011; Seidler et al., 2017). Consistent with Vogel et al. (2011), we found that stigma was a predominant barrier to counseling among male participants. It is recommended that counseling practitioners focus on normalizing common presenting concerns that men are facing and find venues (e.g., barber shops, sports arenas) where they can reach out to men and lessen their concerns about attending counseling (Neukrug, Britton, & Crews, 2013).

Professional counselors can become leaders in reducing stigma toward help-seeking among men by normalizing common presenting concerns. As one example, the stress, anxiety, and depression men face when given a diagnosis of prostate cancer can potentially be reduced by counselors and their professional associations. By developing ways for the public to understand prostate cancer and its related mental health concerns, counselors and their professional associations can lessen the stigma of the disease. Promoting public awareness also can increase men’s likelihood of talking about a diagnosis of prostate cancer with friends, loved ones, and counselors, in a similar way that a diagnosis of breast cancer has been destigmatized over the past few decades. Professional counselors should consider other strategies that can be utilized to enhance the likelihood for men to attend counseling, such as group counseling or an informal setting.

Limitations and Future Research

Because causal attributions cannot be inferred from a cross-sectional survey research design, future researchers can extend the line of research on the FSV barriers using an experimental design by administering the scale to clients prior to and following attendance in counseling. Results might provide evidence of how counseling lessens one’s sensitivity to some barriers. Consistent with the U.S. Census Bureau (2017), the ethnic identity of the majority of participants in our sample was White. Thus, future research should replicate the present study using a more ethnically diverse sample, especially because individuals who identify with ethnicities other than White tend to seek counseling at lower rates (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2008; Vogel et al., 2011). In addition, despite having used a rigorous stratified random sampling procedure, it is possible that because of the sample size, this sample is not representative of adults in the United States. In addition, self-report bias is a limitation of the present study.

Our findings, coupled with existing findings in the literature (Kalkbrenner & Neukrug, 2018; Kalkbrenner et al., in press), suggest that the psychometric properties of the revised version of the FSV Scale are adequate for appraising barriers to seeking counseling among mental health professionals and adults in the United States. The next step in this line of research is to confirm the 3-factor structure of the FSV Scale with populations that are susceptible to mental health disorders and who might be reticent to seek counseling (e.g., veterans, high school students, non-White populations, and the older adult population; Akanwa, 2015; American Public Health Association, 2014; Bartels et al., 2003). Because we did not place any restrictions on sampling based on prospective participants’ history of mental illness, it is possible that the mean differences between participants’ sensitivity to the FSV barriers were influenced by the extent to which they were living with clinical problems at the time of data collection. Thus, future researchers should validate the FSV barriers with participants who are living with psychiatric conditions. Future researchers might also investigate the extent to which there might be differences in participants’ sensitivity to the FSV barriers based on the amount of time they have been in counseling (e.g., the number of sessions).

Because of the global increase in mental distress (WHO, 2018), future researchers should consider confirming the psychometric properties of the FSV Scale with international populations. In addition, we found that when gender, ethnicity, and previous attendance in counseling were entered into the MANOVA as independent variables, significant differences in the Value barrier only emerged for attendance in counseling. Therefore, previous attendance in counseling might account for a more substantial portion of the variance in barriers to counseling than gender and ethnicity. Future researchers can test this hypothesis using a path analysis.

Summary and Conclusion

Attendance in counseling among members of the general U.S. population has become increasingly important because of the frequency and complexity of mental disorders within the U.S. and global populations (WHO, 2017). The primary aim of the present study was to test the psychometric properties of the Revised FSV Scale, a questionnaire for measuring barriers to counseling using a stratified random sample of U.S. adults. The results of a CFA indicated that the Revised FSV Scale and its dimensions were estimated adequately with a stratified random sample of adults in the United States. The appraisal of barriers to seeking counseling is an essential first step in understanding why prospective clients do or do not seek counseling. At this stage of development, the Revised FSV Scale appears to have utility for screening sensitivity to three primary barriers (Fit, Stigma, and Value) to seeking counseling among mental health professionals and adults in the United States. Further, the Revised FSV Scale can be used tentatively by counseling practitioners who work in a variety of settings as one way to measure and potentially reduce barriers associated with counseling among prospective clients.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest or funding contributions for the development of this manuscript.

References

Abrams, A. (2014). Women more likely than men to seek mental health help, study finds. TIME Health. Retrieved from

http://time.com/2928046/mental-health-services-women/

Akanwa, E. E. (2015). International students in Western developed countries: History, challenges, and

prospects. Journal of International Students, 5, 271–284.

American Counseling Association. (2010). 20/20: Consensus definition of counseling. Retrieved from https://www.counseling.org/knowledge-center/20-20-a-vision-for-the-future-of-counseling/consensus-definition-of-counseling

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

American Public Health Association. (2014). Removing barriers to mental health services for veterans. Retrieved from https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2015/01/28/14/51/removing-barriers-to-mental-health-services-for-veterans

Bartels, S. J., Dums, A. R., Oxman, T. E., Schneider, L. S., Areán, P. A., Alexopoulos, G. S., & Jeste, D. V. (2003). Evidence-based practices in geriatric mental health care: An overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 26, 971–990, x–xi. doi:10.1016/S0193-953X(03)00072-8

Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Learn about mental health. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/learn/index.htm

Cheng, H.-L., Kwan, K.-L. K., & Sevig, T. (2013). Racial and ethnic minority college students’ stigma associated with seeking psychological help: Examining psychocultural correlates. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60, 98–111. doi:10.1037/a0031169

Cheng, H.-L., Wang, C., McDermott, R. C., Kridel, M., & Rislin, J. L. (2018). Self-stigma, mental health literacy, and attitudes toward seeking psychological help. Journal of Counseling & Development, 96, 64–74. doi:10.1002/jcad.12178

Cohen, J. E. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Dobmeier, R. A., Kalkbrenner, M. T., Hill, T. L., & Hernández, T. J. (2013). Residential community college student awareness of mental health problems and resources. New York Journal of Student Affairs, 13(2), 15–28.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191.

Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS Statistics (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Han, B., Hedden, S. L., Lipari, R., Copello, E. A. P., & Kroutil, L. A. (2014). Receipt of services for behavioral health problems: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Retrieved from https://www.samh sa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DR-FRR3-2014/NSDUH-DR-FRR3-2014/NSDUH-DR-FRR3-2014.htm

Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Keyes, K. M., Narrow, W. E., Grant, B. F., &, Hasin, D. S. (2008). Racial/ethnic disparities in service utilization for individuals with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders in the general population: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69, 1112–1121.

Hendrick, T. A. M., Fischer, A. R. H., Tobi, H., & Frewer, L. J. (2013). Self-reported attitude scales: Current practice in adequate assessment of reliability, validity, and dimensionality. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43, 1538–1552. doi:10.1111/jasp.12147

Hinkle, J. S. (2014). Population-based mental health facilitation (MHF): A grassroots strategy that works. The Professional Counselor, 4, 1–18. doi:10.15241/jsh.4.1.1

Johnson, K. F., & Kalkbrenner, M. T. (2017). The utilization of technological innovations to support college student mental health: Mobile health communication. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 35(4), 1–26. doi:10.1080/15228835.2017.1368428

Johnson, K. F., Sparkman-Key, N., & Kalkbrenner, M. T. (2017). Human service students’ and professionals’ knowledge and experiences of interprofessionalism: Implications for education. Journal of Human Services, 37, 5–13.

Kalkbrenner, M. T., & Neukrug, E. S. (2018). A confirmatory factor analysis of the Revised FSV Scale with counselor trainees. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Kalkbrenner, M. T., Neukrug, E. S., & Griffith, S. A. (in press). Barriers to counselors seeking counseling: Cross validation and predictive validity of the Fit, Stigma, & Value (FSV) Scale. Journal of Mental Health Counseling.

Kaneshiro, B., Geling, O., Gellert, K., & Millar, L. (2011). The challenges of collecting data on race and ethnicity in a diverse, multiethnic state. Hawai’i Medical Journal, 70(8), 168–171.

Kim, J. (2017, January 30). Why I think all men need therapy: A good read for women too. Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-angry-therapist/201701/why-i-think-all-men-need-therapy

Kim, J. E., Saw, A., & Zane, N. (2015). The influence of psychological symptoms on mental health literacy of college students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 85, 620–630. doi:10.1037/ort0000074

Levant, R. F., Wimer, D. J., & Williams, C. M. (2011). An evaluation of the Health Behavior Inventory-20 (HBI-20) and its relationship to masculinity and attitudes towards seeking psychological help among college men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 12, 26–41. doi:10.1037/a0021014

Lindinger-Sternart, S. (2015). Help-seeking behaviors of men for mental health and the impact of diverse cultural backgrounds. International Journal of Social Science Studies, 3, 1–6. doi:10.11114/ijsss.v3i1.519

Lumina Foundation. (2017). A stronger nation: Learning beyond high schools builds American talent. Retrieved from http://strongernation.luminafoundation.org/report/2018/#nation

Mvududu, N. H., & Sink, C. A. (2013). Factor analysis in counseling research and practice. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 4(2), 75–98. doi:10.1177/2150137813494766

National Institute of Mental Health. (2017). Mental Illnesses. Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness.shtml#part_154787

Neukrug, E., Britton, B. S., & Crews, R. C. (2013). Common health-related concerns of men: Implications for counselors. Journal of Counseling & Development, 91, 390–397. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2013.00109

Neukrug, E., Kalkbrenner, M. T., & Griffith, S. A. (2017). Barriers to counseling among human service professionals: The development and validation of the Fit, Stigma, & Value Scale. Journal of Human Services, 37, 27–40.

Norcross, A. E. (2010). A case for personal therapy in counselor education. Counseling Today, 53(2), 40–42.

Parent, M. C., Hammer, J. H., Bradstreet, T. C., Schwartz, E. N., & Jobe, T. (2018). Men’s mental health help-seeking behaviors: An intersectional analysis. American Journal of Men’s Health, 12, 64–73. doi:10.1177/1557988315625776

Qualtrics [Online survey platform software]. (2018). Provo, UT. Retrieved from https://www.qualtrics.com/

Qualtrics Sample Services [Online sampling service service]. (2018). Provo, UT. Retrieved from https://www.qualtrics.com/online-sample/

Rosenthal, B. S., & Wilson, W. C. (2016). Psychosocial dynamics of college students’ use of mental health services. Journal of College Counseling, 19(3), 194–204. doi:10.1002/jocc.12043

Seidler, Z. E., Rice, S. M., River, J., Oliffe, J. L., & Dhillon, H. M. (2017). Men’s mental health services: The case for a masculinities model. Journal of Men’s Studies, 25, 92–104. doi:10.1177/1060826517729406

Twenge, J. M., Joiner, T. E., Rogers, M. L., & Martin, G. N. (2017). Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among U.S. adolescents after 2010 and links to increased new media screen time. Clinical Psychological Science, Advanced online publication. doi:10.1177/2167702617723376

University of Phoenix. (2013). University of Phoenix survey reveals 38 percent of individuals who seek mental health counseling experience barriers. Retrieved from http://www.phoenix.edu/news/releases/2013/05/university-of-phoenix-survey-reveals-38-percent-of-individuals-who-seek-mental-health-counseling-experience-barriers.html

U.S. Census Bureau. (2017). Population estimates, July 1, 2017. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/quick facts/fact/table/US/PST045216

Vogel, D. L., Heimerdinger-Edwards, S. R., Hammer, J. H., & Hubbard, A. (2011). “Boys don’t cry”: Examination of the links between endorsement of masculine norms, self-stigma, and help-seeking attitudes for men from diverse backgrounds. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58, 368–382.

doi:10.1037/a0023688

Whitfield, N., & Kanter, D. (2014). Helpers in distress: Preventing secondary trauma. Reclaiming Children and Youth, 22(4), 59–61.

World Health Organization. (2015). Global health workforce, finances remain low for mental health. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/notes/2015/finances-mental-health/en/

World Health Organization. (2017). World mental health day, 2017: Mental health in the workplace. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mental_health/world-mental-health-day/2017/en/

World Health Organization. (2018). World health report: Mental disorders affect one in four people. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/whr/2001/media_centre/press_release/en/

Nov 13, 2018 | Volume 8 - Issue 4

Jessica Gonzalez, Sejal M. Barden, Julia Sharp

Exploring client outcomes is a primary goal for counselors; however, gaps in empirical research exist related to the relationship between client outcomes, the working alliance, and counselor characteristics. Thus, the purpose of this investigation was to explore the relationship between the effects of multicultural competence and the working alliance on client outcomes from both client (n = 119) and counselor-in-training (n = 72) perspectives, while controlling for social desirability. Hierarchical regression results indicated counselors-in-training’s perceptions of multicultural competence and client outcome pretest scores were a significant predictor of client outcomes, after controlling for social desirability. Linear mixed effects modeling indicated significant differences in perceptions between both clients and counselors on the working alliance and multicultural competence. Findings highlight the importance of exploring what has already been working for clients before coming to counseling. Additionally, counselors are encouraged to self-reflect and explore how their clients view the relationship between the working alliance and multicultural competence.

Keywords: client outcomes, multicultural competence, working alliance, social desirability, client perspective

The past three decades of research have identified the therapeutic relationship between client and counselor as the most important predictor of change in counseling for clients (Ardito & Rabellino, 2011; Horvath & Bedi, 2002; Norcross, 2002); however, there is limited research on the associations between the working alliance and multicultural competence. Cultivating multicultural competence for counselor trainees has been the focus of considerable empirical research (Horvath & Bedi, 2002), yet the majority of studies have focused on trainees’ self-report of multicultural competence, failing to account for clients’ perceptions of trainees’ competencies (Constantine, 2001; Fuertes et al., 2006). Specifically, more research is needed exploring the influence of multicultural competence as perceived by both clients and counselors-in-training (CITs) on client outcomes (Hays & Erford, 2017; Katz & Hoyt, 2014).

Working Alliance and Client Outcomes

The working alliance is a collaborative approach that refers to the extent of agreement between clients and counselors on the goals, tasks (how to accomplish goals), and bond (development of personal bond between client and counselor) in counseling (Horvath & Greenberg, 1989). The working alliance has been identified as a key factor in positive client outcomes, despite choice of treatment modality or counseling setting (Bachelor, 2013; Baldwin, Wampold, & Imel, 2007). Considerable research has been conducted on the working alliance in relation to clients’ and CITs’ perceptions and client outcomes. Research has shown consistent similarities and differences between clients’ and counselors’ perceptions of the working alliance (Bachelor, 2013; Fitzpatrick, Iwakabe, & Stalikas, 2005; Hatcher & Barends, 1996). For example, Huppert et al. (2014) looked at the effect of counselor characteristics and the therapeutic alliance on client outcomes for clients receiving cognitive behavioral therapy for panic disorder with agoraphobia. The working alliance was measured in Sessions 3 and 9. Multilevel modeling indicated that counselors’ involvement in the alliance predicted attrition. However, client perspective of the working alliance predicted both client outcomes and attrition in counseling.

Studies such as Huppert et al. (2014) highlight the important role that the working alliance has in client outcomes in counseling. However, Drisko (2013) acknowledged that the therapeutic relationship is not the sole predictor of client outcomes and highlighted that additional factors in counseling, combined with a strong therapeutic relationship, can influence outcomes. Other common factors can include client motivation and counselor characteristics such as multicultural competence. Collins and Arthur (2010) described the working alliance as the cornerstone in the counseling process that facilitates a transformative collaborative approach in helping clients explore and understand their cultural self-awareness.

Multicultural Competence and Client Outcomes

In 1992, Sue, Arredondo, and McDavis developed the Multicultural Counseling Competencies, and in 1996 Arredondo and colleagues presented a paper outlining the Tripartite Model of Multicultural Counseling that categorized multicultural competence into three factors: awareness, knowledge, and skills. More recently, the Association for Multicultural Counseling and Development and the American Counseling Association (ACA) have endorsed a set of updated competencies, including a social justice framework entitled the Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies (MSJCC; Ratts, Singh, Nassar-McMillan, Butler, & McCullough, 2015). Research supports positive associations between clients’ perceptions of their counselors’ multicultural competence and (a) client outcomes (Owen, Leach, Wampold, & Rodolfa, 2011); (b) the counseling relationship (Fuertes & Brobst, 2002; Fuertes et al., 2006; Li & Kim, 2004; Pope-Davis et al., 2002); and (c) satisfaction with counseling (Constantine, 2002; Fuertes & Brobst, 2002). These associations show how influential clients’ perceptions of their counselors’ multicultural competence are based on a variety of aspects of the counseling process. However, the majority of studies have focused on exploring counselors’ multicultural competence from only the counselor’s perspective (Worthington, Soth-McNett, & Moreno, 2007).

Self-report multicultural measures have been criticized for being prone to participants responding in a socially desirable manner and having a tendency to measure anticipated behaviors of multicultural competence rather than actual behaviors and attitudes of multicultural competence (Constantine & Ladany, 2000; Worthington, Mobley, Franks, & Tan, 2000). In addition, counselors’ ratings of their multicultural competence can differ from ratings from an observer (e.g., supervisor; Worthington et al., 2000) or their client (Smith & Trimble, 2016). Social desirability is a response bias in which research participants attempt to make a good impression when completing research studies by answering in an overly positive manner (Crowne & Marlowe, 1960). One way researchers can minimize the potential threat of social desirability is to input a social desirability scale (Drisko, 2013) and to control for social desirability, which can improve the accuracy of the research design (McKibben & Silvia, 2016).

In addition to the majority of studies only looking at counselors’ perspectives, there is a need for further research on how CITs’ multicultural competence associates with client outcomes (D’Andrea & Heckman, 2008). For example, Soto, Smith, Griner, Rodríguez, and Bernal (2018) conducted a meta-analysis looking at how many studies have explored how client outcomes are related to their counselors’ level of multicultural competence. Only 15 studies were found that explored client outcomes and counselors’ multicultural competence. From the 15 studies, 73% appeared since 2010, including several unpublished dissertations (40%). The fact that only 15 studies were identified that met inclusion criteria for this study and were found several decades after the multicultural competencies have emerged suggests the need for further investigation on this topic (Soto et al., 2018). Two specific studies, Owen et al. (2011) and Tao, Owen, Pace, and Imel (2015), explored the relationships between multicultural competence and the counseling process. Owen and colleagues’ findings indicated a positive association between clients’ ratings of their counselors’ multicultural competence and client outcomes. Tao and colleagues’ meta-analysis comparing the correlations and effect sizes between quantitative studies (between the years of 2002–2014) of multicultural competence and other measures of the clinical process indicated that clients ratings of their counselors’ multicultural competence accounted for 37% of the variance in the working alliance. Owen et al.’s and Tao et al.’s findings highlight the need to further explore the dynamics between clients’ and counselors’ perceptions of multicultural competence and the working alliance.

Overall, the lack of multicultural competence outcome research may be a hindrance to counselors being able to fulfill the ACA Code of Ethics because of a lack of empirical justification (D’Andrea & Heckman, 2008). In order for multicultural competence scholarship to further advance, professional counseling organizations and scholars (ACA, 2014; Bachelor, 2013; Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs, 2016; Owen et al., 2011) recommend exploring how multicultural competence may influence client outcomes. Additionally, research is needed exploring the similarities and differences between clients’ and counselors’ views on the working alliance and multicultural competence. Further, in self-report counseling investigations, researchers can minimize potential threat to the study by using a social desirability scale as a control variable (Drisko, 2013; McKibben & Silvia, 2016). Thus, the purpose of this investigation was to explore the relationship between the effects of multicultural competence and the working alliance on client outcomes from both client and CIT perspectives, while controlling for social desirability.

As such, we aimed to answer three research questions: (a) Do CITs’ multicultural competence and the working alliance (as perceived by clients) predict client outcomes, while controlling for social desirability from the client’s perspective? (b) Do CITs’ multicultural competence and the working alliance (as perceived by counselors) predict client outcomes, while controlling for social desirability from the CIT’s perspective? and (c) What differences exist between clients’ and CITs’ perceptions of CITs’ multicultural competence and the working alliance, while controlling for social desirability?

Method

Participants

This investigation was conducted at a university-based community counseling research center located in the southeastern region of the United States. The primary investigator worked in the clinic in which the research study was conducted; thus, convenience sampling was used. CITs’ criteria to participate in this study was that the student had to be enrolled in their first or second semester of practicum in a master’s-level counselor education program. In addition, client criteria to participate was that they had to be an adult (over the age of 18) receiving counseling services from the CITs at the counseling research center. A total of 146 adult clients and 85 CITs participated in this study. Missing values and clients who completed the assessments more than twice were removed, yielding a response rate of 82% for clients and 84% for CITs.

Client participants self-identified as female (n = 71, 59.7%) and male (n = 48, 40.3%). The number of clients by age range was: 18–30 (n = 56, 47.1%), 31–40 (n = 27, 47.1%), 41–50 (n = 22, 18.5%), 51–60 (n = 12, 10.1%), and 61–65 (n = 2, 1.7%). Lastly, clients identified as White (n = 64, 53.8%), African American/Black (non-Hispanic, n = 21, 17.6%), Hispanic/Latino (n = 20, 16.8%), Biracial/Multiracial (n = 7, 5.9%), American Indian (n = 2, 1.7%), Asian (n = 1, 8%), and Other (n = 4, 3.4%). CIT participants self-identified as female (n = 61, 84.7%) and as male (n = 11, 15.3%). A majority of counselors were between the ages of 21–26 (n = 54, 75%), followed by 27–37 (n = 18, 25%). CITs identified as White (n = 48, 66.7%), African American/Black (non-Hispanic, n = 7, 9.7%), Hispanic/Latino (n = 7, 9.7%), Biracial/Multiracial (n = 8, 11.1%), Asian (n = 1, 1.4%), and Other (n = 1, 1.4%).

Procedure