Apr 1, 2014 | Article, Volume 4 - Issue 2

Lauren K. Osborne

Unemployment continues to be a growing concern among both civilian and veteran populations. As 14% of the veteran population currently identify as disabled because of service, this population’s need for specialized vocational rehabilitation is increasing. Specifically in Veterans Affairs (VA) Blind Rehabilitation Centers (BRC) where holistic treatment is used in treatment and rehabilitation, career services may be useful in improving quality of life for visually impaired veterans. A group approach to career counseling with visually impaired veterans is discussed using the principles and theory of the cognitive information processing (CIP) approach. This approach emphasizes metacognitions, self-knowledge, occupations knowledge, and the use of a decision-making cycle to improve career decision states and decrease negative career thinking. A group outline is provided and discussion of special considerations and limitations are included.

Keywords: veterans, cognitive information processing, group, career counseling, visually impaired

As of August 2014, the Bureau of Labor and Statistics (BLS) reports the unemployment rate for all veterans as 6.0% (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014b). For men and women who once held steady employment as part of the armed services, this lack of security can prove stressful. All branches of the military are required to provide some sort of preseparation counseling to service members and offer workshops aimed at providing assistance for veteran transitions out of the military. There is limited data on the effectiveness of these programs (Clemens & Milsom, 2008), and it has been estimated that only one out of five veterans is aware of vocational services provided by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA; Ottomanelli, Bradshaw, & Cipher, 2009). As troops continue to withdraw from current operations and unemployment remains high among all Americans, the outlook for postmilitary careers can seem bleak to transitioning veterans and veterans who have been out of service for longer periods of time.

While many transition variables may affect employment opportunities, veterans with disabilities are particularly vulnerable to unemployment and to the perception that employment is not possible (Mpofu & Harley, 2006). The BLS estimates that as of March 2014, approximately 15% of all veterans reported having service-related disabilities (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014a). Bullock, Braud, Andrews, and Phillips (2009) found that 15% of veterans reported that they viewed their physical disability as an obstacle to gaining employment. Of the many types of disabilities reported by veterans, it is estimated that more than one million of these are low vision, with likely over 45,000 veterans having been diagnosed as legally blind (Williams, 2007). In recent years, the VA has put forth a substantial amount of effort to establish a system of inpatient Blind Rehabilitation Centers (BRC) that are designed to improve overall quality of life to veterans with visual impairment (Williams, 2007). As part of this care, a team of rehabilitation and counseling specialists attend to patients and assist veterans in building strength, skills and confidence in the face of their disability (Williams, 2007). One inadequate aspect of the VA’s attempts to increase these individuals’ quality of life is providing quality interventions aimed at improving veterans’ views of employment opportunities as well as their ability to acquire employment.

Current Use of Evidence-Based Interventions

Approximately 67% of veterans attended at least one counseling session in 2006 and of these, 24.1% attended at least one group therapy session with the average number of group visits being approximately 15.9 (Hunt & Rosenheck, 2011). Veterans with service-connected disabilities are more likely than those without disabilities to engage in counseling, and typically the number of sessions veterans may make is unlimited (Hunt & Rosenheck, 2011). Most group intervention research regarding veterans incorporates a combination of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), trauma-focused therapy, interpersonal problem solving, and relapse prevention, and focuses on treatment of mental health diagnoses like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression (Ready et al., 2012). These approaches have been found effective in relieving symptoms of such diagnoses through implementation of theory- and evidence-based techniques (Ready et al., 2012).

Holistic approaches to treating the overall wellness of veterans is a growing trend in research. The use of a combination of interpersonal strategies and cognitive behavioral techniques such as behavioral activation also has been found to improve overall wellness in veterans, even as physical functioning is diminished because of chronic illness (Perlman et al., 2010). Across treatment approaches, a common finding is that veterans perceive the use of groups positively. In one study using interpersonal and cognitive-based approaches to aid transitioning veterans, the researchers found that the group-based format was the key factor in positive outcomes (Westwood, McLean, Cave, Borgen, & Slakov, 2010). Likewise, Ready et al. (2012) attributed low dropout rates to strong group cohesion and resulting positive peer pressure. Hunt and Rosenheck (2011) noted that veterans are likely to prefer group therapy because of reduced perceived stigma and increased cost effectiveness for all involved.

In the arena of vocational psychology, a substantial amount of research exists regarding career decision making, specifically using the cognitive information processing (CIP) approach developed by Sampson, Reardon, Peterson, and Lenz (2004) to conceptualize employment concerns. One of the largest components of the research here focuses on dysfunctional career thoughts and their ability to hinder effective career decision making. Bullock et al. (2009) specifically found that dysfunctional career thoughts can stunt readiness for career choices. Furthering this assertion, Bullock-Yowell, Peterson, Reardon, Leierer, and Reed (2011) found that negative career thoughts in fact mediate the relationship between life stress and career decision states. A CIP approach to career counseling with veterans has only been applied in individual cases in the research, and in such applications, significant progress toward making career decisions and improving satisfaction with current career situations has been reported (Clemens & Milsom, 2008).

Components of a CIP approach to career counseling such as homework assignments, providing resources, and empowering clients to complete research have been found to contribute to positive career outcomes (Ryder, 2003). Similarly, a de-emphasis on pathology and a shift in focus toward coping skills and concrete goals have been found to play a part in veterans’ commitment to group therapy (Perlman et al., 2010). Veterans with increased awareness of available vocational services and opportunities have been shown to be five times more likely to return to work after service-related injuries than those without knowledge of available resources (Ottomanelli et al., 2009). Evaluations of veterans’ interests, skills and abilities according to John Holland’s RIASEC (realistic, investigative, artistic, social, enterprising, conventional) theory have found that veterans endorse a wide range of Holland interest codes, which can characterize both people and career choices (Bullock et al., 2009). That is, when reporting aspects of career development according to the six areas delineated by Holland (listed above), veterans report a wide range of career-related interests, skills and abilities (Bullock et al., 2009). Through education regarding these factors and the variability among both employees and employers, further options for employment may be considered that were not considered before engaging in career counseling. Because Bullock et al. (2009) did not find significant differences between veterans and the general adult population regarding their skills, abilities and interests, this article asserts that counselors can readily apply the evidence-based CIP approach to veterans’ career issues without great concern that dramatic differences may hinder effectiveness of the approach.

Using CIP Groups as Career Interventions for Veterans

The CIP Model: Theoretical Framework

The CIP approach to counseling as developed by Sampson et al. (2004) is based on two core concepts: (1) the pyramid of information-processing domains, and (2) the CASVE cycle of decision making. This approach focuses on the holistic nature of careers, the process of choosing a career path and the generalizability of the decision-making process to areas beyond occupations (Bullock-Yowell et al., 2011). The CASVE cycle refers to a decision-making process that involves five steps to make up the acronym, which are communication, analysis, synthesis, valuing and execution. The first step is communication, which entails identifying what decision needs to be made or “identifying the gap” between where one is and where he or she wants to be following implementation of a decision (Sampson et al., 2004). The following step, analysis, involves one identifying his or her own value as an employee and what he or she wants to receive from a career or job (Sampson et al., 2004). Following this, during synthesis, one elaborates and crystallizes the occupational options available depending on the self-knowledge gained (Sampson et al., 2004). After identifying top choices, the next step is valuing, in which the individual engages a cost-and-benefit analysis of the options available, and using the self-knowledge gained during analysis, ranks the options that have been identified (Sampson et al., 2004). The final stage of the CASVE cycle is execution, in which the decider puts his or her action plan into place and carries out the choice or decision made through the process (Sampson et al., 2004).

The four assumptions underlying the process and theory of CIP are the following: (1) emotions and cognitions can influence career problem solving and decision making; (2) effective problem solving requires both gaining knowledge and thinking about the knowledge gained; (3) what is known about the self and the environment is constantly interacting and evolving, and organization of this information occurs in complex ways; and (4) career problem solving and career decision making are skills that can be improved through learning and practice (Sampson et al., 2004). CIP-focused career counseling uses cognitive behavioral-based techniques such as cognitive restructuring, behavioral activation, and homework to facilitate the basic aims of the counseling process (Bullock-Yowell et al., 2011).

Application of CIP Model to Veteran Interventions

As stated previously, approximately 15% of the veteran population report having service-related disabilities and of this group, more than one million suffer from service-related visual impairment (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014a; Williams, 2007). The purpose of a group-based approach to vocational intervention is to further the current goals set forth by existing VA BRC: of enhancing and improving quality of life for these disabled individuals (Williams, 2007). In addition to medical rehabilitation activities such as mobility training and orientation, veterans deemed likely to benefit from mental health treatment should also engage in individual and/or group counseling (Kuyk et al., 2004). The purpose of rehabilitation activities is to increase veterans’ independence through improving their self-efficacy toward tasks that become extremely difficult for visually impaired individuals (Kuyk et al., 2004). Offering vocational counseling in addition to these skill-building activities is meant to further enhance this purpose by providing insight and progress toward satisfying independence for these individuals in vocational domains. The group format would best be served in conjunction with current treatment offered to veterans in established VA BRC.

The CIP approach aims to assist people in making appropriate career choices through education and practice of problem-solving and decision-making skills (Sampson et al., 2004). As the world of work continues to evolve, even for civilians who have been a part of it for decades, teaching disabled veterans how to approach this new world is extremely relevant to helping them further adapt to this dynamic environment (Sampson et al., 2004). Career counseling in general has this goal of assisting clients in recognizing and resolving issues (McAuliffe et al., 2006), and the CIP approach provides a standardized outline to address this need. In the case of visually impaired veterans, as with most disabilities, the need for advocacy also plays a part in approaching career counseling (Bullock et al., 2009). It will be important for counselors to continue monitoring perceived barriers and assessing how veteran participants may be able to overcome these independently, while also recognizing when advocacy may be appropriate (Clemens & Milsom, 2008).

Group Goals Using the CIP Model

The group’s goals are in line with the majority of research regarding veteran transitions and career counseling for individuals with disabilities (Clemens & Milsom, 2008; Perlman et al., 2010; Westwood et al, 2010). However, the goals of the CIP approach to career counseling (Sampson et al., 2004) should be noted and incorporated according to established veteran goals regarding employment and careers. Goals include the following: (1) decreasing negative career thoughts and increasing confidence in one’s ability to make career decisions, (2) increasing knowledge of an effective career decision-making process and how to apply it to decisions outside occupational domains, (3) increasing self-knowledge regarding skills, abilities and interests in relation to decision making, (4) increasing independence through education and practice of completing work outside group sessions, and (5) creating a cohesive and safe environment for participants to feel comfortable to make both mistakes and progress.

Individual Factors to Consider

Suggested Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

In attempt to achieve the aforementioned goals, prescreening for inclusion in the suggested group should occur in individual settings with the group leader. The group is formatted such that it is a closed group, but because of the nature of most treatment facilities, staggered start and end dates may allow for continuous enrollment in the protocol. Optimally, groups will be composed of five to eight patients and meet once a week for an hour over the course of 7 weeks. Suggested prescreening should include evaluation of eligibility as well as completion of assessments to aid in achieving group goals. Some assessments may be used as outcome measures to assess effectiveness, while some serve informative purposes for the group participants.

Inclusion criteria that should be considered are an individual diagnosis of visual impairment, current receipt of treatment at a VA BRC where groups may be conducted, and ability to articulate a career-related gap that can benefit from the CIP approach. Exclusion criteria to consider include current clinically significant substance abuse or dependence, unwillingness to engage in group work or work outside group, and extreme distress as assessed by the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS) or other assessments used by the rehabilitation center to assess psychopathology. Extreme distress may be characterized by “severe” classifications according to scores on any scales or “moderate” classification of scores on the depression scale of the DASS. Further, individuals who are only able to identify a single question that needs to be addressed or noncareer-related goals would likely not benefit from the group as outlined. Additionally, individuals with complete blindness may be excluded from the group-based CIP treatment, as they are likely to need more focused treatment. These individuals should be offered the option of engaging in the protocol on an individual basis, because of the need for additional augmentation and specialized attention with regard to completing and interpreting assessments, as well as adapting homework assignments.

Suggested Assessments to Include

The outlined assessments are suggested for use in evaluating eligibility of participants, measuring outcomes, and as informative tools for participants to use in sessions:

Career Thoughts Inventory (CTI). The CTI (Sampson, Peterson, Lenz, Reardon, & Saunders, 1996) is a measure of negative or dysfunctional career thoughts that interfere with career decision making. It is a 48-item self-report inventory that uses a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0=strongly disagree to 3=strongly agree. This inventory includes items such as “I’m so confused, I’ll never be able to choose a field of study or occupation,” and “I’m afraid that if I try out my chosen occupation I won’t be successful.” The CTI has three subscales—decision-making confusion, commitment anxiety, and external conflict—which are used to measure negative career thoughts.

Career Planning Confidence Scale (CPCS). The CPCS (McAuliffe et al., 2006) is a 39-item measure of career planning confidence. It uses a 5-point Likert Scale ranging from 1=no confidence to 5=completely confident with items such as “ready to invest time and energy necessary to make a career decision” and confidence in “finding general career information.” The CPCS has six subscales: readiness to make a career decision, self-assessment confidence, generating options, information-seeking confidence, deciding confidence, and confidence in implementing one’s decision.

Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS). The DASS (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) is a 42-item self-report measure of depression, anxiety and stress. It consists of three subscales using a 4-point Likert scale that ranges from 0=did not apply to me at all to 3=applied to me very much, or most of the time. Scales are measured using items such as “I couldn’t seem to experience any positive feeling at all” and “I felt sad and depressed,” and the three subscales are depression, anxiety and stress.

Self-Directed Search (SDS). The SDS (Holland, Fritzsche, & Powell, 1994) is an interest inventory based on Holland’s RIASEC theory, which yields a three-letter code to classify individual interests. The assessment requests that test takers rate their preferences or perceptions of tasks, capabilities, occupations and self-estimates. Items on the SDS require yes or no responses in each RIASEC area and scale. Users can enter codes yielded from this assessment on the O*NET website, which will generate occupational options in line with their codes and information regarding individual occupations. The recently developed fifth edition of this measure added to the resources available for veterans with the development of a Military Occupations Finder. This resource allows veterans and active-duty military to link military occupation titles with civilian titles that can aid in transferring skills and experiences to civilian employment.

All measures except for the SDS are recommended to be administered at completion of the group protocol to assess treatment outcomes. After initial screening and assessment, all participants will engage in a pregroup meeting as well as six sessions outlined according to recommendations by Sampson et al. (2004) regarding applications of CIP theory to career counseling (refer to Appendix for session outlines).

Special Considerations

There are several considerations to be made for use of a CIP group with the intended population. If used with groups of veterans as discussed, individuals will likely maintain interactions in other areas of their lives, which constitute increased contact outside group settings. Because of the nature of veteran groups and rehabilitation centers such as VA BRC, group members are also likely to engage in other treatment and social settings together, and thus, group leaders should carefully discuss confidentiality with all group members. Likewise, group treatment as part of a holistic approach by a treatment team is often the case at veteran treatment centers, so issues regarding expectations of confidentiality should be addressed. Because of the hierarchical nature of the group content, consistent attendance is necessary, and group facilitators should explain this to participants and have a discussion regarding consequences for missing sessions, as a part of the initial group rules.

Group facilitators should pay attention to the intended participant pool and the potential for complicated interactions between disability, racial and other identities and worldviews that may influence perceptions and engagement in the group process (Mpofu & Harley, 2006). As career intervention research provides no evidence for specifically engaging in career counseling among blind veterans, it is critical to continually consider the nature of this disability as well as individual differences. The disability status of the veterans is likely not the only influential factor on career decisions and possibly not the primary lens through which participants may perceive career options and identities (Mpofu & Harley, 2006). As such, it is crucial that providers not make assumptions regarding their perceptions, and that each individual receives the opportunity to respectfully voice opinions and points of view.

For these visually impaired individuals, there will still be many barriers regarding implementing homework, completing assessments and carrying out career goals. The counselor must expect that there will be a need for both advocacy and additional individual assistance to members for them to complete the career group. Throughout sessions, continual assessment of perceived barriers by participants may aid in improving the decision-making process for veterans, especially as related to gaining employment. Patients at VA BRC may have access to state-of-the-art equipment that allows them to conduct online research and carry out tasks on their own, so with this in mind, clinical judgment will be critical in deciding when to step in and when to promote autonomy. In particular, administration of assessments must be adapted to accommodate visual disabilities. In treatment settings where this level of technology is not available, counselors should make special considerations for completion of homework. Specifically, finding the resources for group members should be a priority to allow for optimal retention of concepts.

Limitations to Consider

One significant limitation in conducting this group among visually impaired veterans is the emphasis placed on participants completing work outside sessions, as the participant pool will likely vary in level of visual impairment. The use of handouts will be limited unless the group leader adapts their formatting according to individual participants’ visual needs. Another limitation is that the VA’s individual treatment facilities may have policies and procedures that require altering some aspects of this proposal. Without previous research backing the use of this or any other vocational protocol for blind veterans, this approach may provide a promising avenue for future interventions; but because of stringent policies, counselors may not be allowed to create this group. Another possible limitation of group work with veterans is the use of a leader without service history. On one hand, the group members might view a civilian leader with respect for his or her experience in the civilian workforce; on the other, the group members might distrust a leader who lacks affiliation with military service and experiences. If this question is deemed significant, the use of a co-leader with military background may be beneficial to the group’s success.

References

Bullock, E. E., Braud, J., Andrews, L., & Phillips, J. (2009). Career concerns of unemployed U.S. war veterans: Suggestions from a cognitive information processing approach. Journal of Employment Counseling, 46, 171–181. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1920.2009.tb00080.x

Bullock-Yowell, E., Peterson, G. W., Reardon, R. C., Leierer, S. J., & Reed, C. A. (2011). Relationships among career and life stress, negative career thoughts, and career decision state: A cognitive information processing perspective. The Career Development Quarterly, 59, 302–314. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.2011.tb00071.x

Clemens, E. V., & Milsom, A. S. (2008). Enlisted service members’ transition into the civilian world of work: A cognitive information processing approach. The Career Development Quarterly, 56, 246–256. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.2008.tb00039.x

Holland, J. L., Fritzsche, B. A., & Powell, A. B. (1994). The self-directed search technical manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Hunt, M. G., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2011). Psychotherapy in mental health clinics of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67, 561–573. doi:10.1002/jclp.20788

Kuyk, T., Elliot, J. L., Wesley, J., Scilley, K., McIntosh, E., Mitchell, S., & Owsley, C. (2004). Mobility function in older veterans improves after blind rehabilitation. Journal of Rehabilitation Research & Development, 41, 337–345.

Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales (2nd ed.). Sydney, Australia: Psychology Foundation.

McAuliffe, G., Jurgens, J. C., Pickering, W., Calliotte, J., Macera, A., & Zerwas, S. (2006). Targeting low career confidence using the career planning confidence scale. Journal of Employment Counseling, 43, 117–129. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1920.2006.tb00011.x

Mpofu, E., & Harley, D. A. (2006). Racial and disability identity: Implications for the career counseling of African Americans with disabilities. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 50, 14–23. doi:10.1177/00343552060500010301

Ottomanelli, L., Bradshaw, L. D., & Cipher, D. J. (2009). Employment and vocational rehabilitation services use among veterans with spinal cord injury. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 31, 39–43. doi:10.3233/JVR-2009-0470

Perlman, L. M., Cohen, J. L., Altiere, M. J., Brennan, J. A., Brown, S. R., Mainka, J. B. & Diroff, C. R. (2010). A multidimensional wellness group therapy program for veterans with comorbid psychiatric and medical conditions. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 41, 120–127. doi:10.1037/a0018800

Ready, D. J., Sylvers, P., Worley, V., Butt, J., Mascaro, N., & Bradley, B. (2012). The impact of group-based exposure therapy on the PTSD and depression of 30 combat veterans. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4, 84–93. doi:10.1037/a0021997

Ryder, B. E. (2003). Counseling theory as a tool for vocational counselors: Implications for facilitating clients’ informed decision making. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 97, 149–156.

Sampson, J. P., Peterson, G. W., Lenz, J. G., Reardon, R. C., & Saunders, D. E. (1996). Career Thoughts Inventory: Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Sampson, J. P., Jr., Reardon, R. C., Peterson, G. W., & Lenz, J. G. (2004). Career counseling & services: A cognitive information processing approach. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2014a, April 4). Table A-5. Employment status of the civilian population 18 years and over by veteran status, period of service, and sex, not seasonally adjusted [Economic news release]. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.t05.htm

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2014b). Economic news release: Employment situation of veterans summary. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/vet.nr0.htm

Westwood, M. J., McLean, H., Cave, D., Borgen, W., & Slakov, P. (2010). Coming home: A group-based approach for assisting military veterans in transition. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 35, 44–68. doi:10.1080/01933920903466059

Williams, M. D. (2007). Visual impairment and blindness: Addressing one of the growing concerns of today’s veterans. Exceptional Parent, 37, 78–80.

Appendix

Session Outlines

Pregroup Meeting

Discussion regarding the nature of the group.

- Note differences between this and other groups they may engage in as part of rehabilitation treatment.

- Discuss expectations of the group (for both members and leaders).

- Outline overall goals and structure of sessions and importance of attendance.

- Discuss confidentiality limits.

Session 1

- Review expectations regarding group and confidentiality.

- Set group rules through discussion and agreement of group members.

- Conduct group member introductions and begin discussion regarding expected gains from group.

- Introduce CIP Pyramid and discuss Metacognitions domain.

- Return CTI and CPCS results and provide broad interpretation of scores.

- Encourage discussion regarding reactions and thoughts about results.

- Introduce individual learning plan.

- Homework: outlining specific goals for group process.

- Discuss different types of goals: increasing confidence, outlining concrete career plans, find a new career path, and so on.

Session 2

- Review previous session: Metacognitions, assessment results, CIP Pyramid.

- Review homework. Allow for discussion regarding goals and process of writing them.

- Discuss possible activities to be filled in, and allow for group member interaction and feedback.

- Introduce Self-Knowledge: link to homework and interests.

- Introduce Holland’s RIASEC model and theory, and allow for discussion of members’ expected codes.

- Discuss SDS results: reactions and thoughts.

- Discuss how current knowledge, skills and abilities from military may fall in or out of this code.

- Introduce Military Occupations Finder.

- Homework: Look up occupations related to Holland code on O*NET and finalize activities for Individual Learning Plan.

Session 3

- Review metacognitions and self-knowledge pieces of CIP pyramid.

- Review Individual Learning Plans and discuss difficulties regarding outlining activities.

- Allow for discussion among group members regarding feedback or discussion about possible activities.

- Introduce options knowledge and review O*NET experience and feedback regarding information found or not found.

- Discuss perceived barriers to employment in occupations of interest.

- Introduce CASVE cycle.

- Allow for discussion of how decisions are currently carried out by participants.

- Explain CASVE cycle and provide example regarding decision of when to disclose disability and disability needs to future employers.

- Encourage participants to suggest new examples regarding their current state of decision making and where they may be in the cycle.

- Homework: Complete at least one activity on Individual Learning Plan and narrow down possible occupations to 3-5.

- Discuss possible barriers to completing activities.

Session 4

- Review last session: CASVE cycle, options knowledge and self-knowledge.

- Review homework: experiences of completing activities, discuss what helped or hindered the process.

- Members will further discuss current individual positions in CASVE cycle.

- Discuss process of synthesizing and valuing choices, and expand on purpose of homework to complete this process.

- Ask for examples from participants regarding weighing costs and benefits of options.

- Discuss perception of current confidence levels in making decisions.

- Homework: Complete two activities on Individual Learning Plan.

- Discuss perceived barriers to completing these.

Session 5

- Review last session: CASVE cycle, synthesis and valuing.

- Review homework: Outcomes of completing activities, what helped or hindered the process? What is the next activity that should be completed?

- Conduct pretermination discussion regarding current status of participants in the CASVE cycle.

- Where do you see yourself, and how much further do you need to go to execute your goals?

- What would help you to further close your identified gap? Discussion regarding previously anticipated barriers and current perceived barriers.

- Homework: Develop a plan for execution of action needed to close gap.

- Administer post-CTI and CPCS.

Session 6

- Review homework: What are plans for closing gaps?

- Discussion regarding returning to Communication phase of CASVE cycle.

- What will your life look like when gap is closed?

- What other steps will be taken to close this gap?

- How can you apply this decision-making process to other decisions outside careers?

- Discuss post-CTI and CPCS results and broad interpretation.

- Encourage participants to share their reactions to changes in scores.

- Discuss plans to continue to increase career planning confidence and decrease negative thoughts.

- Termination

- Discuss content: What has changed, what did you learn about decision making and career choices?

- Discuss process: What did you learn from engaging in this process? About yourself, from others?

- Provide further options for career counseling at the Rehabilitation Center, Veteran Centers and VA Hospitals. Administer post-DASS.

Lauren K. Osborne is a doctoral student in counseling psychology at the University of Southern Mississippi. Correspondence can be addressed to Lauren K. Osborne, 118 College Drive, #5025, Hattiesburg, MS 39402, lauren.osborne@eagles.usm.edu.

Apr 1, 2014 | Author Videos, International, Volume 4 - Issue 1

Viviana Demichelis Machorro, Antonio Tena Suck

The authors conducted an exploratory study using cultural domain analysis to better understand the meaning that advanced students and professional counselors in Mexico give to their professional identity. More similarities than differences were found in the way students and professionals define themselves. The most relevant concepts were empathy, ethics, commitment, versatility, training and support. Students gave more weight to multiculturalism and diversity, whereas professionals prioritized commitment and responsibility at work. Prevention did not appear as a relevant concept, posing challenges for professional counselor training programs in Mexico.

Keywords: professional identity, multiculturalism, ethics, prevention, counselor training, Mexico

In the field of professional counseling, it is important to consider the benefit of developing a strong professional identity. Initiative 20/20: Vision for Counseling’s Future, represented by influential organizations such as the American Counseling Association (ACA), the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP), and the National Board for Certified Counselors (NBCC), identifies principles that must be developed in order to strengthen the counseling profession (ACA, n.d.). These principles include sharing a common professional identity and presenting the counseling profession in a unified way. CACREP (2009) recognizes the relevance of promoting professional development in counseling programs; the organization’s standards were written to ensure that counseling student development is congruent with professional identity, as well as the necessary knowledge and skills to practice counseling effectively and efficiently.

In Mexico, steps have been taken toward developing such standards. The Mexican Association for Counseling and Psychotherapy (AMOPP), founded in 2008, has stated in its mission and objectives the promotion of counselor identity and stimulation of professional development (AMOPP, 2014). However, the process of defining professional identity for counselors has complex aspects that imply a great challenge for the Mexican counseling guild (Calva & Jiménez, 2005; Portal, Suck, & Hinkle, 2010).

First, there are few Mexican university programs that train counselors. The only such Mexican graduate program is the master in counseling (maestría en orientación psicológica) at Universidad Iberoamericana, which started in fall 2003 and was awarded CACREP accreditation in 2009. This program prepares students in prevention, evaluation and intervention using an integrative approach that includes theories and techniques, promotion of multicultural sensibility, and a focus on vulnerable populations (Universidad Iberoamericana, n.d.-a). Most students in this master in counseling program have a bachelor’s degree in psychology, which makes for a mixed psychologist/counselor identity that is not easy to separate, and that is likely experienced as a psychological specialty by faculty, students and the general public.

In contrast to countries like the United States and Canada, where a bachelor’s degree is awarded first and students professionalize afterward at the graduate level, in Mexico, students professionalize at the undergraduate level, which promotes professional identity at this point. Thus, in Mexico the possibility of studying for an undergraduate professional program in counseling does not exist, which contributes to the difficulty of counseling being recognized as an independent profession.

There are plenty of reasons to study the professional identity of counselors in Mexico. First, counseling awareness within the community could be increased, making counseling accessible to a population that needs quality mental health services. The Mexican Poll of Psychiatric Epidemiology (ENEP) of the National Institute of Psychiatry reveals that 28.6% of the population presents some type of psychiatric disorder at some point in life, mostly anxiety (14.3%), followed by the use of illegal substances (9.2%) and affective disorders (9.1%). Nevertheless, despite this high incidence of mental health problems, only 10% of the population that presents with a mental disorder receives the attention it needs (Medina-Mora et al., 2003).

Secondly, there is limited professional literature in Mexico regarding professional counseling. Searching behavioral science databases revealed only one reference in a Mexican book regarding psychologists’ professional identity (Harsh, 1994) and no articles about counselors’ professional identity. If the professional identity of counselors in Mexico were more defined, it could help prospective students who are interested in studying counseling. It also could help practicing counselors form a solid base to serve as a platform to strengthen and enrich their professional behavior and clarify their professional identity. Neukrug (2007) has stated that when counselors find out who they are, they will know their limits and relationships with other professions. Therefore, the authors explored the professional identity of counselors in Mexico to better understand their definitive characteristics.

Professional identity, according to Balduzzi and Corrado (2010), is the definition one makes about self in relation to work and an occupational guild. It begins with training, during which professional identity can be promoted or obstructed, and includes interactions with others as well as modeling. Counselors begin to develop professional identity as they are trained (Auxier, Hughes, & Kline, 2003; Brott & Myers, 1999), integrating personal characteristics in the context of a professional community (Nugent & Jones, 2009). Brott and Myers (1999) studied how professional identity is developed among school counseling graduate students in the United States and reported that counselors develop an identity that serves as a reference for professional decisions and assumed roles. These researchers used grounded theory to explain the identity development process of counselors in training. First, students go through a stage of dependence to attain the stage of independence at which the locus of control is internal and the counseling student has the opportunity for self-evaluation without external evaluation. In this advanced stage, experience is integrated with theory, joining personal and professional identities.

To analyze the development of professional identity in counseling students in the United States, Auxier et al. (2003) developed their research from a constructivist model that assumed reality is socially developed, determined by the place where it is elaborated and based on the participants’ experience. They developed the model of “recycling identity formation processes” (p. 32). This model explains that for constructing an identity, a person needs to go through (a) conceptual learning via classes and lectures; (b) experiential learning by practices, dynamics and internship; and (c) external evaluation from teachers, supervisors, coworkers and clients.

Nelson and Jackson (2003) wanted to better understand the development of professional identity among Hispanic counseling students in the United States. They conducted a qualitative study and found seven relevant topics: knowledge, personal growth, experience, relationships, achievements, costs, and perceptions of the counseling profession (Nelson & Jackson, 2003). Although the results were congruent with other findings, such as the need to be accepted and included, relationships such as those available from caring faculty or the support of family and friends were identified as meaningful factors that contribute to formation of a professional identity.

Similarly, du Preez and Roos (2008) used social constructivism to analyze the development of professional identity in South African students between the fourth and last year of their studies as undergraduate counselors. Participants elaborated on visual and written projects regarding their professional development training. Through an analysis of this work, four professional identity themes were identified: capacity for uncertainty, greater self-knowledge, self-reflection and growth (du Preez & Roos, 2008).

Skovholt and Ronnestad (1992) explained that identity development implies progress of attitudes about responsibility, ethical standards, and membership in professional associations. According to the Skovholt and Ronnestad (1992), a counselor’s identity differs from other professional identities because a therapeutic self is shaped by a mixture of professional and personal development. The researchers explained that professional identity is a combination of professional self (e.g., roles, decisions, applying ethics) and personal self (e.g., values, morals, perceptions) that create frameworks for decision making, problem-solving patterns, attitudes toward responsibilities, and professional ethics.

In one of the few quantitative investigations on the topic, Yu, Lee and Lee (2007) used the concept of “collective self-esteem” (p. 163) as a synonym for collective and professional identity. They conducted a study to learn whether the collective self-esteem of counselors influences or mediates their work satisfaction and how they relate to clients. The researchers found that “job dissatisfaction is negatively related to greater levels of private collective self-esteem, and in turn, greater private collective self-esteem is positively related to better client relationships” (p. 170). Based on their conclusions, it is important to study the professional identity of counselors in Mexico, who must work from a place of job satisfaction and good client relationships in order to successfully address their clients’ social needs.

Hellman and Cinamon (2004) performed a series of semi-structured interviews for 15 professional school counselors with a consensual qualitative research (CQR) strategy to classify counselors through the stages of Super’s (1992) career theory: exploration, establishment, maintaining and specialization. The classification was made according to the perceptions the researchers described about counseling, professional identity, work patterns, and resources and barriers at work. In the beginning stages of their career, counselors describe school counseling as a job or a role, but later they consider counseling a profession. Furthermore, counselors start by depending on external recognition, specific techniques, and highly structured programs. As they become more experienced, counselors gain self-confidence and rely more on their professional judgment.

In general, researchers have described subjective experience to explain the development of professional identity. Furthermore, findings suggests that counselors in their identity development gain more self-knowledge, confidence in their abilities and judgment, knowledge and involvement in their profession and its standards, and a combination of personal and professional characteristics and experiences.

Method

Cultural domain with free listing was chosen as the data collection technique. Cultural domain is “the set of concepts chosen by memory through a reconstructive process that allows participants to have an action plan as well as the subjective evaluation of the events, actions or objects, and it has gradually become one of the most powerful techniques to evaluate the meaning of concepts” (Valdez, 2010, p. 62). It has been accepted in Mexico and applied principally in social psychology and education to define and delineate several concepts such as psychologist (García-Silberman & Andrade, 1994); love, men and women (Hernández & Benítez, 2008); parenting (Medina et al., 2011); the rich and poor (Valdez, 2010); family (Andrade, 1994, 1996; Camacho & Andrade, 1992); and corruption (Avendaño & Ferreira, 1996), among others. This methodology was chosen because “professional identity” is a subjective concept to which different meanings are granted based on personal experiences; the idea was to show the concepts related to the meaning counselors give to their identity.

In this study, the authors posed the following question: What meaning do Mexican counselors give to their professional identity? The dependent variable was professional identity and the attributive variable was level of preparation (student or professional). The study was transversal (data recovery at a unique time frame) and descriptive.

Participants

The participants in the study included advanced students in at least their third semester in the master’s counseling program at Universidad Iberoamericana and professional counselors who graduated from the program at least one year ago. Fifteen of 17 advanced students (88.23%) participated, including 3 men and 12 women with an average age of 29.40 years. Twelve of 29 graduates (41%) participated, including 1 man and 11 women, with an average age of 42.75 years.

Survey Development and Procedure

Each participant was asked to list 10 words or brief terms to describe the concept counselor professional identity. Afterward, participants were asked to rank each word from 1–10, assigning 1 to the characteristic word considered the most relevant and 10 to the word considered least relevant. Advanced counseling students were given the survey in their classrooms and graduate counselors were sent the survey via e-mail. The surveys were analyzed following Valdez (2010), obtaining the definitions with the semantic weight (M), for both students and professionals, considering the frequency with which the words were mentioned, as well as the assigned rankings. The authors used a mathematical procedure called el valor M total [Total M Value] (VMT; Valdez, 2010), which entails multiplying the frequency of occurrence times the weight of each defining word. Next, a cross-multiplication was done, considering the highest VMT as 100% in order to obtain the semantic distance between each concept and the stimulus concept (i.e., counselor professional identity). This procedure is referred to as FMG (Valdez, 2010).

Results

For the students, the defining terms for the stimulus counselor professional identity, listed in the order of the frequency and relevance with which the participants used and ranked them, were as follows:

empathic, understands, sensitive, ethical, honest, sincerity, fair, prepared, knowledge, trained, updated, flexible, adapts, support, help, backup, listening, human, warm, congruence, authentic, mental health, well-being, trustable, integrative, responsible, commitment, intervening, implementing, action, professionalism, respect, tolerance, multicultural, contextualized, diversity, observer, acceptance, non-judgment, structure, organizes, collaboration, design, planning, creativity, patience, goal recognition, positive view, growth, development, contention, service attitude, dedication, different, brief, social commitment, interdisciplinary, reflective, analyzes, guides, communicates, open, wide view, curious, scientific, relationship, psychotherapist, therapist, educates, prudent, diagnoses, prevention, dynamic, specialized, assertive, personal, practical, resilient, facilitator, personal therapy, strategic and consultant.

Consensually, the researchers separated these concepts into semantic categories, taking into account terms that are synonyms or that have a very similar meaning, leaving 57 definitions. Similarly, those concepts with more semantic weight were detected, resulting in the Semantic Association Memory (SAM) group according to Valdez (2010), which refers to the 15 categories with the most relevance (M total). This process is done considering frequency and weight. This group includes 17 categories since the last 3 present the same value. Table 1 shows terms that counseling students used to define counselor identity, weighted in order of relevance.

Table 1

Counseling Students’ Identity

For graduated professional counselors, the defining terms for the stimulus counselor professional identity, listed in the order of frequency with which participants used and ranked them, were as follows:

empathic, commitment, dedicated, responsible, ethical, serves vulnerable populations, social service, prepared, experienced, updated, supervised, studious, research, listening, authentic, genuine, congruent, support, assistance, orientation, guidance, honesty, integrity, integrative, trustable, educates, informative, professional, versatile, adaptable, flexible, active, guide, creative, discipline, work, therapeutic relationship, curious, healthy, motivated, reflective, framing, intelligent, strength, ecological, humble, sensitize, acceptance, verbal, focused, aware, systemic, problem-solving, catalyze, assertiveness, decision-making, practical, positive, growth, development, fair, influence, self-knowledge, respectful, tolerant, reflects, cheerful and certified.

Once more, the defining words were classified into semantic categories, obtaining 48 definitions, as well as detecting those with the most semantic weight, resulting in a SAM group with the 15 most relevant categories. The authors derived these categories by considering higher frequencies and weight. The participants indicated that being empathic was the closest concept to counselor professional identity. The authors established empathic as FMG = 100, and cross-multiplied the other concepts to obtain their distance. Table 2 shows terms that professional counselors used to define counselor identity, weighted in order of relevance.

Table 2

Professional Counselors’ Identity

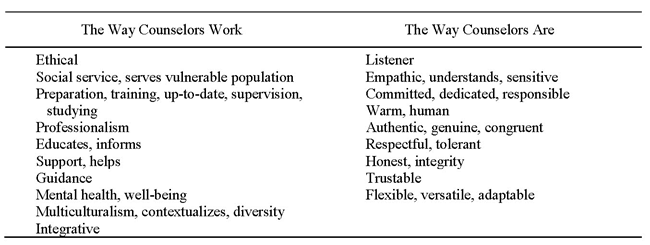

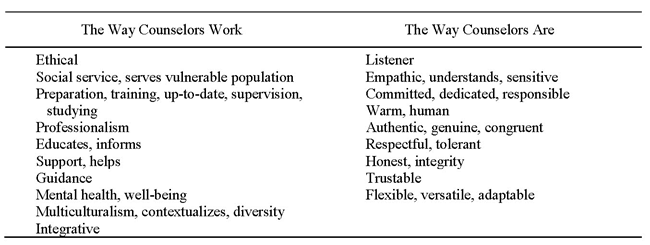

The resulting defining concepts also were divided into two categories: (a) the way counselors work and (b) the way counselors are. The authors believe it is important to understand how counselors actually perceived their role in their work (e.g., professional behaviors, attitudes, approaches, roles, and functions) and also the way they identify themselves personally (e.g., characteristics and abilities; see Table 3).

Table 3

Counselors’ Roles and Characteristics

Discussion

It is possible to distinguish professional identity with common themes that begin during counselor training and continue as a process (Auxier et al., 2003; Balduzzi & Corrado, 2010; Brott & Myers, 1999). More similarities than differences were found comparing students and graduates.

For students and professionals, empathy occupies the most relevant place when describing counselor identity. It is interesting to observe how counselors, students and professionals prioritize values and concepts that come from a humanistic approach (e.g., empathy, authenticity, being genuine, congruent, warmth). This finding coincides with what Hansen (2003) expressed in that the counseling profession has its roots in the humanistic model, which is an undeniable part of its identity. This is also congruent with the values that the Universidad Iberoamericana promotes with students.

Ethics appear predominantly in both sets of participants, likely since professional identity and ethics are closely related (Nugent & Jones, 2009; Ponton & Duba, 2009; Skovholt & Ronnestad, 1992). Responsibility and commitment, as well as training and preparation, appear to be important defining words for counseling students and graduates, indicating that these concepts are considered fundamental. Furthermore, students and graduates consider flexibility as one of a counselor’s professional identity characteristics, which relates to versatility in counselor roles and functions. Attending to the vulnerable population and social commitment were prominent for graduates, which fortunately matches well with the mission of counseling at their university (Universidad Iberoamericana, n.d.-b).

According to the data, the concept of prevention does not emerge as a direct priority that Mexican counselors believe distinguishes them. Students mention this concept, but just once and with low relevance; however, it does not reveal itself at all as a defining term for professionals. This finding does not correlate well with actual course descriptions within the counseling master’s degree program (Universidad Iberoamericana, n.d.-a); therefore, changes in the program curricula may be needed. Students identified multiculturalism and diversity in the description of their professional identity; however, graduates did not. This distinction could be related to the recent teaching of this topic in Mexico and is expected to increase in the new generation of graduates.

It is important to note the limitations to this preliminary descriptive study. The sample was limited to 27 participants and no in-depth interviews were done in order to more comprehensively understand student and counselor perceptions. There is no basis for suggesting that the results can be generalized to other counselor populations, given that the study was specific to the particular context of one program at a private university. It is imperative to continue the study of counselor professional identity in Mexico with more participants and in-depth interviews.

There are several implications for Mexican counselor educators in regard to the development of counselor professional identity. First, there is the understanding that counselors are models in their professional activities including writing, affiliations and certification. It is imperative that educators invite students to get involved in national and international associations; promote practice, research and writing; and exalt the relevance of counselor certification.

Prevention—on the one hand a historic activity of many counselors—has proven to be a less important to Mexican counselors. To enhance this concept, the university curricula design may need to emphasize this topic in the thematic content of the program’s courses. Practica and internships might as well include prevention strategies in the student’s roles and functions. Furthermore, an elective course about prevention program design and implementation could be offered. On the other hand, it may be that prevention is a good idea, but not actually practiced by professional counselors because people tend to not pay for preventive services.

In summary, counseling students and graduates in Mexico share a common professional identity self-described as empathic, ethical, committed, versatile, trained and supportive. Efforts should be made to continue enhancing counseling core values as the profession continues to grow in Mexico, as well as internationally.

References

American Counseling Association. (n.d.). 20/20: A vision for the future of counseling. Retrieved from http://www.counseling.org/20-20/index.aspx

Andrade, P. P. (1994). El significado de la familia [The meaning of family]. La Psicología Social en México, V, 83–87.

Andrade, P. P. (1996). El significado del padre y madre [The meaning of father and mother]. La Psicología Social en México, VI, 337–342.

Asociación Mexicana de Orientación Psicológica y Psicoterapia. (2014). Misión y objetivos [Mission and objectives].

Auxier, C. R., Hughes, F. R., & Kline, W. B. (2003). Identity development in counselors-in-training. Counselor Education and Supervision, 43, 25–38. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2003.tb01827.x

Avendaño, S. R., & Ferreira, N. L. (1996). Significado psicológico de corrupción en estudiantes universitarios [Psychological meaning of corruption in college students]. La Psicología Social en México, VI, 132–136.

Balduzzi, M. M., & Corrado, R. E. (2010). Representaciones sociales e ideología en la construcción de la identidad profesional de estudiantes universitarios avanzados [Social representations and ideology in professional identity of advanced college students]. Revista Intercontinental de Psicología y Educación, 12, 65–83.

Brott, P. E., & Myers, J. E. (1999). Development of professional school counselor identity: A grounded theory. Professional School Counseling, 2, 339–348.

Camacho, V. M., & Andrade, P. P. (1992). El concepto de familia en los adolescentes [The concept of family in adolescents]. La Psicología Social en México, IV, 295–302.

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2009). 2009 CACREP standards. Retrieved from http://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/2009-Standards.pdf

Calva, G., & Jiménez, N. (2005). En busca de la identidad del orientador psicológico en México [In search of counselor identity in Mexico]. Temas selectos en Orientación Psicológica, 1, 9–15.

du Preez, E., & Roos, V. (2008). The development of counsellor identity: A visual expression. South African Journal of Psychology, 38, 699–709.

García-Silberman, S., & Andrade P. (1994). La imagen del psicólogo en los adolescentes [The psychologist image for adolescents]. In AMEPSO (Ed.), La Psicología Social en México (5th ed., pp. 672–678). Mexico City: AMEPSO..

Hansen, J. T. (2003). Including diagnostic training in counseling curricula: Implications for professional identity development. Counselor Education and Supervision, 43, 96–107. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2003.tb01834.x

Hellman, S., & Cinamon, R. G. (2004). Career development stages of Israeli school counsellors. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 32, 39–55. doi:10.1080/03069880310001648085

Hernández, C., & Benítez, M. (2008). El amor, las mujeres y los hombres [Love, women and men]. Archivos Hispanoamericanos de Sexología, 14, 103–135.

Medina, J., Fuentes, N., Escobar, S., Valdez, V., Farías, P., Guerrero, I., . . . Manjarrez, A. (2011). Orientación que transmiten los padres a sus hijos adolescentes [Orientation transmitted from parents to their adolescent sons]. Revista Mexicana de Orientación Educativa, 8, 2–9.

Medina-Mora, M. E., Borges, G., Muñoz C. L., Benjet, C., James, J. B., Bautista, C. F., . . . Aguilar-Gaxiola, S. (2003). Prevalence of mental disorders and use of services: Results from the Mexican National Survey of Psychiatric Epidemiology. Salud Mental, 26, 1–16.

Nelson, K. W., & Jackson, S. A. (2003). Professional counselor identity development: A qualitative study of Hispanic student interns. Counselor Education and Supervision, 43, 2–14. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2003.tb01825.x

Nugent, F. A., & Jones, K. D. (2009). Introduction to the profession of counseling (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Neukrug, E. (2007). The world of the counselor: An introduction to the counseling profession (3rd ed.). Belmont, CA: Brooks-Cole.

Ponton, R. F., & Duba, J. D. (2009). The ACA Code of Ethics: Articulating counseling’s professional covenant. Journal of Counseling and Development, 87, 117–121. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2009.tb00557.x

Portal, E. L., Suck, A. T., & Hinkle, J. S. (2010). Counseling in Mexico: History, current identity, and future trends. Journal of Counseling and Development, 88, 33–37. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00147.x

Skovholt, T. M., & Ronnestad, M. H. (1992). The evolving professional self: Stages and themes in therapist and counselor development. Chichester, England: Wiley.

Super, D. E. (1992). Toward a comprehensive theory of career development. In D. H. Montross & C. J Shinkman (Eds.), Career development: Theory and practice (2nd ed., pp. 35–64). Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas.

Universidad Iberoamericana. (n.d.-a). Maestría en orientación psicológica [Master in Counseling]. Retrieved from http://www.uia.mx/web/site/tpl-Nivel2.php?menu=mgPosgrado&seccion=M_orientacionPsicologica

Universidad Iberoamericana. (n.d.-b). Misión y visión [Mission and vision]. Retrieved from http://www.uia.mx/web/site/tpl-Nivel2.php?menu=mgPerfil&seccion=mgPerfil

Valdez, J. L. (2010). Las redes semánticas naturales, usos y aplicaciones en psicología social [Cultural domain, uses and applications in social psychology]. (4th ed.). Mexico City: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México.

Yu, K., Lee. S-H., & Lee, S. M. (2007). Counselors’ collective self-esteem mediates job dissatisfaction and client relationships. Journal of Employment Counseling, 44, 163–172. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1920.2007.tb00035.x

Viviana Demichelis Machorro is a doctoral student at Universidad Iberoamericana in Mexico City. Antonio Tena Suck is the Director of the Psychology Department at the Universidad Iberoamericana in Mexico City. Correspondence can be addressed to Viviana Demichelis Machorro, Universidad Iberoamericana, Departamento de Psicología, Prolongación Paseo de la Reforma 880, Lomas de Santa Fe, 01219 México Distrito Federal, viviana.demichelis@amopp.org.

Mar 14, 2014 | Video Reviews

Whether a counselor is working with a mother experiencing anxiety and depression, a man presenting with severe social anxiety, a teacher with panic symptoms, an individual battling chronic pain, or a recovering alcoholic, Hayes and other contributing therapists in the ACT in Action DVD Series provide a solid foundation for practitioners to understand the main principles and processes involved in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). Hayes effectively delivers in each of his 6 DVDs, providing extensive details and instruction. For each DVD, Hayes further created an instructor’s manual resource that includes a complete transcript, summarizes basic treatment principles and strategies, offers discussion questions, and provides information on additional websites, readings, and videos.

Whether a counselor is working with a mother experiencing anxiety and depression, a man presenting with severe social anxiety, a teacher with panic symptoms, an individual battling chronic pain, or a recovering alcoholic, Hayes and other contributing therapists in the ACT in Action DVD Series provide a solid foundation for practitioners to understand the main principles and processes involved in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). Hayes effectively delivers in each of his 6 DVDs, providing extensive details and instruction. For each DVD, Hayes further created an instructor’s manual resource that includes a complete transcript, summarizes basic treatment principles and strategies, offers discussion questions, and provides information on additional websites, readings, and videos.

During the first video of this series, Facing the Struggle, Hayes beautifully normalizes the human condition, shows how pain represents an ally, and demonstrates the process of obtaining informed consent using an ACT approach. In his second video, Control and Acceptance, Hayes delicately illustrates techniques to help clients accept what they cannot control and behave based on personal values. This video uses appropriate self-disclosure and provides the audience with warning signs and strategies to overcome what Hayes labels “pseudoacceptance.” Similarly, in video three, Cognitive Defusion, clinicians implement a variety of thought-diffusion techniques, such as deliteralization, and physicalizing, which can be easily integrated into therapists’ toolboxes and used to reduce anxiety and depression. Appropriate metaphors allow Hayes to connect with material presented in earlier DVDs.

During the fourth DVD, Mindfulness, Self, and Contact with the Present Moment, Hayes provides the audience with a fruitful dialogue on mindfulness practices. Specifically, he demonstrates using an eyes-closed exercise with a recovering addict to promote self-mind-body connection and deeper engagement in therapy. In this DVD, ACT co-founder Kelly Wilson further demonstrates the utility of ACT in clinical supervision with another therapist working with a resistant client. In this segment, viewers observe powerful role-plays and other empowering techniques for ACT therapists.

Values and Action and Psychological Flexibility, the fifth and sixth DVD in the series, demonstrate how each prior process, component, and ACT technique build upon and work together. Values and Action highlights the significance of values in psychotherapy and the importance of identifying, incorporating, and creating meaningful goals based on personal values. In the example of working with a client diagnosed with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), exposure exercises are implemented and viewers observe what it means for clients to remain in the present moment without engaging in defense mechanisms, while concurrently remaining grounded and practicing psychological flexibility. These final two DVDs are highly active and show the ways that ACT can be applied across gender, age, race, socioeconomic status, disability status and cultural background.

In this DVD series, the authors do a sufficient job of demonstrating how clinicians with a variety of therapeutic styles can adopt components of ACT in their own practices, while also noting that this approach is no better than others. For example, Hayes demonstrates how ACT serves as a brief but integrative approach, combining elements from mindfulness, cognitive-behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy. Throughout the series, Hayes provides summaries and explanations for what he is doing and why to enhance the understanding of his audience.

While this series includes numerous strengths, several caveats and limitations should be noted. At times, the terminology is complex and vague (e.g., cognitive entanglement; creative hopelessness) and it would be helpful to give visual and written definitions, or at least link audience members not as familiar with ACT to specific handouts to obtain such definitions. Another area for improvement relates to the video recording procedures; at times, the camera zooms in on Hayes and the audience may benefit from seeing the client’s non-verbal behaviors or reactions to Hayes. Third, a gun analogy is used during Control and Acceptance and the current reviewer found this technique somewhat violent and inappropriate to use with clients. Finally, the DVD series would be more complete if it included Hayes using ACT to work with a resistant client.

Watching these DVDs is probably more helpful than reading books and articles, as audience members visually observe key processes involved in ACT. Additionally, clinicians and other professionals in the field who are interested in honing his/her ACT skills can learn practical tools to use in psychotherapy with over twelve hours of instruction, live sessions and diverse therapeutic case examples. The author skillfully enlists several ACT therapists from across the United States to participate in this DVD series, including Ann Bailey-Ciarrochi, JoAnne Dahl, Rainer Sonntag, Kirk Strosahl, Robyn Walser, Rikard Wicksell, and Kelly Wilson. In summary, viewers will develop significant insight into applying ACT with a variety of clients and in numerous therapeutic settings after watching this entire series.

Visit http://www.psychotherapy.net/ to read more about the series.

Hayes, S.C. (Ed.). (2007). ACT in Action DVD Series. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger.

Reviewed by: Mary-Catherine McClain, Johns Hopkins University Counseling Center, Baltimore, MD.

The Professional Counselor

https://tpcwordpress.azurewebsites.net

Feb 28, 2014 | Book Reviews

Conceptualization and Treatment Planning for Effective Helping by Barbara F. Okun and Karen L. Suyemoto (2013) is presented as a two-section book. The chapters in section one are intended to facilitate the choice and development of a theoretical orientation for counseling trainees. These chapters intend to accentuate the connection that exists between theoretical approaches to counseling and the specific implications in formulating a case conceptualization, as well as a sound treatment plan. Section two of the book focuses on the process of conceptualization and treatment planning. This section incorporates an integrative approach and is intended to be more practically oriented.

Conceptualization and Treatment Planning for Effective Helping by Barbara F. Okun and Karen L. Suyemoto (2013) is presented as a two-section book. The chapters in section one are intended to facilitate the choice and development of a theoretical orientation for counseling trainees. These chapters intend to accentuate the connection that exists between theoretical approaches to counseling and the specific implications in formulating a case conceptualization, as well as a sound treatment plan. Section two of the book focuses on the process of conceptualization and treatment planning. This section incorporates an integrative approach and is intended to be more practically oriented.

The specific goals stated by the authors of this book are: (1) assist counselors-in-training in developing their own theoretical orientation; (2) explore the conceptualization process in light of specific theoretical approaches; (3) identify the impact that the counselors’ and clients’ worldviews, as well as their therapeutic relationships, have in case conceptualization and treatment planning; (4) assist counselors-in-training in gathering, organizing and integrating information necessary for case conceptualization and treatment planning; and (5) further develop the case conceptualization and treatment planning skills of counselors-in-training.

Section one of the book mainly focuses on the strong connection between the counselor-in-training’s understanding of change, his or her theoretical orientation and the formulation of a case conceptualization. A significant emphasis is placed on the counselor’s worldview and how it affects the understanding of clients, formulation of a case conceptualization and treatment plan, as well as the course and outcomes of counseling. The authors assume an ecological perspective and stress the importance of looking at both the counselor and client contexts. From a multicultural, advocacy and a social justice perspective, this section of the book facilitates a brief but comprehensive understanding of how these very important relational factors play a concrete role in the process of understanding both the client’s and counselor’s perspective, as well as the implications for case conceptualization and intervention.

The main goal in section two of the book is to help counselors apply their self-awareness, skills in gathering and incorporating information from clients, and understanding of the process of problem formation and change to case conceptualization and treatment planning. The authors used an integrative approach to illustrate this process and emphasize the continuous nature of the case conceptualization and treatment process. This section includes several significant contributions, including the emphasis placed on integrating information provided by multiple sources in the client’s systems, the connection to issues of multicultural competent diagnosis, and the iterative nature of the conceptualization process as an event that needs to be revisited and developed continuously and collaboratively with clients.

In general, the authors do a great job of formulating the basic parameters that could be used by advanced counselors-in-training in the often-confusing process of selecting a theoretical approach. They specifically facilitate a practical and reflective context in which counselors-in-training are able to explore the influences in their personal world views. They are able to explore, for instance, the relationship between their ideas of problem formation, change, power, privilege, health, and pathology and how this influences the choice of a specific theoretical approach. A point they are trying to make throughout the book is the importance of looking at the case conceptualization and treatment planning process through the lens of both the client and the counselor, as well as considering the issues that arise because of their interaction, and the contexts in which these interactions occur.

The authors provide specific reflective and practical strategies to illustrate the process of organizing and integrating information at different points of the case conceptualization and treatment planning process. As a whole, the book provides a good integration of conceptualization and treatment planning, and explores the connection between these factors and other aspects of the counseling process, from initial assessment and establishing therapeutic rapport to evaluation and termination.

Okun, B. F., & Suyemoto, K. L. (2013). Conceptualization and treatment planning for effective helping. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Reviewed by: Raul Machuca, NCC, Barry University, Miami Shores, FL.

The Professional Counselor Journal

HOME PAGE

Feb 28, 2014 | Book Reviews

The counselor’s role when working with an individual with a life-threatening illness is not always straightforward. Counselors sometimes do not know or fully understand how to work with these clients, as treatment is frequently exclusively biological and often ignores psychological, social and spiritual factors. However, Doka stresses the importance of interdisciplinary teams using the biopsychosocial-spiritual model in the treatment of individuals with life-threatening illness. In his book, Doka clearly outlines and demystifies the role of counselors who are working with these individuals and their families.

The counselor’s role when working with an individual with a life-threatening illness is not always straightforward. Counselors sometimes do not know or fully understand how to work with these clients, as treatment is frequently exclusively biological and often ignores psychological, social and spiritual factors. However, Doka stresses the importance of interdisciplinary teams using the biopsychosocial-spiritual model in the treatment of individuals with life-threatening illness. In his book, Doka clearly outlines and demystifies the role of counselors who are working with these individuals and their families.

The second edition of Counseling Individuals with Life-Threatening Illness includes updated information, such as models of concurrent care and counseling families throughout life-threatening illness and during the grieving process. Following a brief introduction, Doka begins Chapter 2 by discussing historical perspectives on dying and illness, and then explores early and contemporary contributions on dying. Doka follows with a chapter on the seven sensitivities of effective professional caregivers: sensitivity to the whole person, pain and discomfort, communication, autonomy, needs, cultural differences and treatment goals (Chapter 3). He thoroughly depicts each of these sensitivities, and then describes the specific skills counselors need in order to work effectively with families and individuals impacted by life-threatening illness (Chapter 4). In this chapter, Doka includes a discussion on sensitivity to various age groups, populations and generational cohorts, as life-threatening illness impacts individuals in various phases of the life cycle in vastly different ways. This segment includes information on working with children, adolescents, older adults and individuals with intellectual disabilities. Chapter 5 describes possible responses to life-threatening illness, including physical, cognitive, emotional, behavioral and spiritual responses. Doka outlines the role counselors have in assisting clients with recognizing how they are impacted in each of these areas when responding to the crisis of illness. For counselors who desire to strengthen their understanding of the illness experience, Chapter 6 provides a discussion on the numerous factors that may influence the client’s experience of illness.

Chapters 7–11 recommend ways to effectively work with clients in each phase of illness: “The Prediagnostic Phase: Understanding the Road Before,” “Counseling Clients Through the Crisis of Diagnosis,” “Counseling Clients in the Chronic Phase of Illness,” “Counseling Clients in Recovery,” and “Counseling Clients in the Terminal Phase.” Doka gives a great deal of attention to assisting the client with expressing his or her feelings and fears, as well as preserving and redefining relationships with family members, friends, and caregivers. Chapter 12 explores ways to counsel families throughout each phase of a life-threatening illness, including how to continue to work with these individuals following the death of their loved one.

Counseling Individuals with Life-Threatening Illness provides a practical guide for counselors who work with clients and families impacted by life-threatening illness. The language and content are appropriate for undergraduate and graduate courses, as well as workshops and trainings for professionals. Doka integrates examples from his own personal work with clients, which makes the application of concepts and theories presented in this book easy to comprehend. Doka also includes an appendix with discussion questions, role-playing scenarios, and case studies that may be used for workshops, trainings, or activities in a classroom setting. As the healthcare system continues to evolve, Counseling Individuals with Life-Threatening Illness is a valuable resource for counselors as they find themselves working on interdisciplinary teams with individuals and families impacted by life-threatening illness.