Aug 24, 2023 | Volume 13 - Issue 2

Amy Biang, Clare Merlin-Knoblich, Stella Y. Kim

Although researchers have found that patient weight bias negatively impacts health care professionals, research is limited on client weight bias toward counselors. Given that a client’s perception of their counselor impacts the therapeutic alliance, more research is needed to understand client weight bias toward counselors. To fill this research gap, we conducted a quasi-experimental study examining people’s weight bias toward a hypothetical counselor who was overweight, average weight, or underweight. Participants (N = 189) received a random assignment to a questionnaire featuring one of the three hypothetical counselors. Participants indicated their willingness to trust them, select them as a counselor, and follow their counsel. Results from a Welch ANOVA analysis showed a statistically significantly greater preference for average-weight and overweight counselors than those who are underweight. Additionally, the participants were less willing to follow counsel from overweight and underweight counselors. Implications for counselors are discussed.

Keywords: client weight bias, overweight, underweight, average weight, counselors

Body weight can inform a client’s perception of a health professional’s level of authority, trust, and competence (Hutson, 2013; Schwartz et al., 2006). Researchers have found that overweight bias toward health professionals like fitness instructors and medical physicians results in negative impressions (Hutson, 2013; Puhl et al., 2013; Puhl & Heuer, 2010). Clients may perceive lower competence, conscientiousness, personal grooming, and intrapersonal ability for overweight individuals compared to average-weight ones (Allison & Lee, 2015). When people seek mental health treatment, these perceptions may hinder their selection of a counselor who is perceived as overweight. Additionally, research on underweight bias has emerged that shows adverse outcomes toward underweight individuals (Allison & Lee, 2015; Beggan & DeAngelis, 2015; Davies et al., 2020a). Despite research on overweight and underweight bias in health professionals, limited research on either topic exists in the counseling profession.

Research on weight bias is necessary for counseling given that counselor attributes have the potential to be an integral part of a client’s decision-making and change process (Hauser & Hays, 2010). Attributes of a counselor that may affect client impressions, such as attractiveness (Grimes & Murdock, 1989) or race (Kim & Kang, 2018; Meyer & Zane, 2013), illuminate the social influence process of counseling (McKee & Smouse, 1983). Social influence is pervasive in the judgments of people everywhere. Weight bias continues to be a product of social influence and, as such, weaves stereotypes into the minds of those who consume the message of weight as a moral indiscretion (Beggan & DeAngelis, 2015). As clients search for, build trust with, and consider life changes with a counselor, weight bias ought to be explored as a potential issue for counselors.

In the past 35 years, researchers published only one study about weight perceptions toward overweight counselors (Moller & Tischner, 2019). Furthermore, there were no published studies about underweight counselors found. This gap in research is notable, as body weight can influence clients’ first impressions of a counselor and their expectations of the ensuing relationship (Moller & Tischner, 2019). Understanding how weight bias may impact this relationship is vital to building an authentic therapeutic relationship, which may otherwise be hindered by weight bias, which inaccurately frames a counselor’s competence (McKee & Smouse, 1983). Thus, we examined client weight bias toward overweight, underweight, and average-weight counselors in the current study.

Literature Review

Weight Bias

The term weight bias indicates a negative attitude about the perceived weight of an individual (Christensen, 2021). Historically, weight bias has been directed at people perceived as overweight; however, recent evidence suggests that underweight bodies generate weight bias as well (Allison & Lee, 2015; Beggan & DeAngelis, 2015; Christensen, 2021; Davies et al., 2020a, 2020b). Weight bias is pervasive throughout the United States (McHugh & Kasardo, 2012; Puhl et al., 2014). Negative stereotypes associated with being overweight include laziness, lack of motivation, psychological instability, social rejection, and incompetence in the workforce (Hinman et al., 2015; Lewis et al., 1997; Moller & Tischner, 2019). Likewise, incorrect stereotypes about underweight people include psychological instability or weakness (Marini, 2017). Body weight is not explicitly identified as an issue in the multicultural and social justice competencies (Ratts et al., 2016). However, weight bias is similar to sexism, racism, and classism in its harmful impact on people (Bucchianeri et al., 2013). It is still a common form of prejudice (McHugh & Kasardo, 2012).

Weight bias has become a social justice issue because of how it negatively impacts the lived experiences of people across social contexts (Nutter et al., 2018). Similar to other identities that elicit prejudice, weight bias impacts an individual’s opportunities in the workforce (Hutson, 2013), quality of mental health care (Puhl et al., 2014), and interpersonal relationships (Puhl & Heuer, 2010). Oppression from weight bias may deter a person from forming relationships or making connections with others out of fear of rejection or discrimination based on weight. Likewise, a person with weight bias may struggle to overlook the body of their counselor because of their worldview of weight and health. Even if the client remains in counseling, this initial bias may impede the therapeutic alliance process.

Therapeutic Alliance

The therapeutic alliance is a key variable in predicting client outcomes in counseling (Ackerman & Hilsenroth, 2001). This alliance represents the degree to which the client and counselor are engaged in collaboration, their commitment to one another, and their understanding of the counseling process (Allen et al., 2017; Lorr, 1965). Clients are as important as counselors in building this alliance, which involves their impression of and reaction to the counselor (Tudor, 2011). Disruptions in the therapeutic alliance can be generated from the client’s adverse reaction to the counselor, which thus impacts client outcomes (Ackerman & Hilsenroth, 2001). Weight can be a disruption, as some clients see a counselor being overweight as a barrier to opening up and engaging in counseling (Moller & Tischner, 2019). As the therapeutic alliance impacts clients remaining in counseling (Sharf et al., 2010), biases toward the counselor may hinder building the relationship, leading to early termination. Clients discriminating against counselors may limit capable counselors who fall outside socially acceptable weights from co-building the therapeutic alliance (McKee & Smouse, 1983).

Even with weight bias possibly diminishing the initial therapeutic relationship, Allen et al. (2017) found that communication on tasks/goals was a predictor of a strong therapeutic alliance and activation (i.e., the clients’ readiness and willingness to take on the management of their mental health care). Allen et al. found that alliance around the tasks/goals of therapy had long-term benefits, while an initial therapeutic bond was only associated with activation at the beginning of therapy. These findings suggest that despite client bias, a strong alliance may still form if there is a connection between counselor and client on their treatment goals and plan.

Despite a client and counselor’s mutual investment in a counseling relationship, research about weight bias in counseling has focused solely on counselors’ perceptions of clients’ weight and its influence on the therapeutic alliance (Kinavey & Cool, 2019; McHugh & Kasardo, 2012; Puhl et al., 2014). Thus, research has insufficiently examined how a counselor’s weight may hinder this alliance (Moller & Tischner, 2019). This gap is further concerning given that researchers have found that professionals in other disciplines identified as overweight or underweight face discrimination in the workplace (Beggan & DeAngelis, 2015; Hutson, 2013).

Overweight Bias Toward Counselors

Researchers have found that counselors are subject to weight bias from clients. Moller and Tischner (2019) examined client perceptions of counselors by specifically examining counselor weight. They conducted a qualitative story completion task with students from Great Britain aged 15–24 (N = 203) and found that participants perceived overweight counselors as incompetent. Counselors’ competence came into question because of the perception that being overweight implies a lack of emotional stability, personal discipline, and mental stability (Moller & Tischner, 2019). Participants also reported perceiving overweight counselors as distracting because of their physical appearance. Additionally, participants viewed an overweight counselor as having poor psychological health. Some participants noted that being overweight suggested an eating disorder (ED), such as bulimia or binge eating disorder. Furthermore, responses indicated that weight bias would impact the therapeutic relationship, and many participants would not want to work with an overweight counselor (Moller & Tischner, 2019).

These results are striking, and further research is needed to corroborate their value, as they point to a high level of bias toward overweight counselors. These types of inaccuracies can perpetuate prejudice and discrimination that may also hurt potential clients who would otherwise not have access to a counselor. Stereotypes and biases impact those who choose to work in this profession and could struggle to feel they belong in the helping professions.

Underweight Bias

Research geared toward overweight bias is well established in the health professions; however, evidence suggests that underweight health professionals also experience bias and discrimination (Allison & Lee, 2015; Beggan & DeAngelis, 2015; Davies et al., 2020a, 2020b). Researchers have noted stereotypes suggesting that extreme thinness may indicate a lack of wellness or the presence of a mental health issue like anorexia (Davies et al., 2020a). Furthermore, implicit bias toward underweight people may also come from the survival instinct that hunger, poverty, and war create underfed people, and we want to be with those who can help us survive (Marini, 2017).

Interestingly, scholars have noted that if being underweight is not perceived as stemming from health issues or an ED, people possess more favoritism toward underweight persons, limiting institutional discrimination toward them (Allison & Lee, 2015; Beggan & DeAngelis, 2015). In some social settings, a slender appearance of health follows socially accepted norms and may supersede the importance of actual health (Moller & Tischner, 2019). This leads to what is known as thin privilege; hence the possibility that there is enough benefit to being thin that it negates any negative attitudes or behaviors by others.

This thin privilege allows others to overstep the concept of civil inattention, which is how people are recognized appropriately in polite society. Civil inattention warrants people to be discrete in commenting on or noticing differences among those around them (e.g., those with disabilities, obesity, low socioeconomic status, or other marginalized identities). Some people believe that being underweight may invite a breakdown of civil inattention (Beggan & DeAngelis, 2015). This breakdown may lead a client to comment on a counselor’s body, such as “You are so skinny; how can you understand anything I am feeling about my body” or “If I were as thin as you, I would…” These types of comments are seen as acceptable because they infer a compliment about a socially desirable attribute. However, they can invite feelings of judgment and unease for the counselor, perpetuating a rupture in the therapeutic alliance. As we continue to understand that weight bias exists along a spectrum, counselors may feel prepared to broach the topic of weight regardless of where they fall.

One last finding that significantly impacts weight bias toward counselors comes from a qualitative study of adults (N = 18) with an average female body mass index (BMI) of 18.80 or male BMI of 21.68, both of which fall within the normal range of 18.5 to 24.9 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2022). Beggan and DeAngelis (2015) found that participants believed that underweight people lack empathy for others who struggle with weight. Such a belief would be impactful for a counselor, given that empathy is integral for a successful counseling relationship (Clark, 2010).

Empathy

Empathy is one of the six core conditions necessary for client change and contributes significantly to therapeutic outcomes. Clients can perceive empathy from counselors when counselors act in ways consistent with their frame of reference (Feller & Cottone, 2003).

Empathy is a deep understanding of the client’s circumstances. When there is weight bias, the client may not believe their counselor can understand their frame of reference if they are of differing body weights, especially if the client is coming in for body image concerns or health concerns. Even though the counselor has empathy, the client may not accept this as truth, hindering the building of a solid therapeutic alliance.

Weight as Credibility

Whether professionals are overweight or underweight, their bodies are part of their résumé. The term bodily capital describes one’s credibility as portrayed by the body and can influence how professionals are judged by their physical appearance (Hutson, 2013; Moller & Tischner, 2019). The body can be viewed as a symbolic container that indicates the investment of time and resources into health and well-being (Hutson, 2013). Previous scholars have asserted that the healthier a professional appears, the more likely clients and patients will accept their advice and trust their counsel (Hutson, 2013; Puhl et al., 2013). Health expectations are amplified for health professionals, as overweightness can be seen by some as a moral transgression and an inadequacy that may translate into their work (Beggan & DeAngelis, 2015). Some people believe that to be psychologically healthy, a person must appear to be of an appropriate weight; this indicates willpower, discipline, and self-control (Tischner, 2019). Though these ideas are inaccurate for psychological health, they may influence how clients see counselors on the far ends of the weight spectrum.

Antifat Attitudes

Antifat attitudes are a different but related construct to weight bias. An antifat attitude is “a negative attitude toward (dislike of), belief about (stereotype), or behavior against (discrimination) people perceived as being ‘fat’” (Meadows & Daníelsdóttir, 2016, p. 47). Weight bias refers to a negative attitude toward any size body (Christensen, 2021), whereas antifat attitudes describe dislike and discrimination toward people perceived as overweight (Meadows & Daníelsdóttir, 2016). Antifat attitudes have created a marginalized group that faces external stigma throughout society, with some individuals feeling internal stigma due to personal experiences.

Despite encounters with prejudice, some clients who are overweight will still prefer an average-weight counselor because of their own bias toward being overweight (Moller & Tischner, 2019) and will have similar antifat attitudes as average-weight individuals (Schwartz et al., 2006). Contingencies of self-worth encompass the domains in a person’s life that create self-esteem (Clabaugh et al., 2008). When body weight is a domain, success or failure in their ability to lose or gain weight can lead to lower self-worth. Because of weight bias, working with a counselor who mirrors the client’s undesired body weight may impact the client’s willingness to work with the counselor. Examining weight bias across the spectrum and correlating BMI with antifat attitudes will give us further insight into these findings and if they influence client bias toward counselors.

Purpose of the Study

This study examined if client weight bias influences a client’s trust in a counselor’s competence, willingness to follow a counselor’s advice, and desire to select a counselor for therapy. We further examined if a client’s antifat attitudes are associated with their weight bias toward counselors. The following research questions guided this study: 1) Does a counselor’s weight impact a client’s decision to trust, follow advice, and select the counselor? 2) Is there an association between a client’s antifat attitudes and weight bias toward counselors? 3) Are there differences in weight bias toward counselors based on the socio-demographics of the clients using their services? and 4) Do participants with eating disorders have similar perceptions of counselors due to weight bias as those without eating disorders?

Methodology

Recruitment

At the time the research was conducted, the researchers—Amy Biang, Clare Merlin-Knoblich, and Stella Kim—were affiliated with the same university; as such, IRB approval was obtained from that university before recruiting participants. People were eligible to participate in this study if they were 18 years or older and signed an electronic consent form indicating their willingness to participate. We recruited participants through purposive and snowball sampling in three ways. First, Biang emailed a compiled database of counseling professionals within their acquaintance to request they send the survey to previous clients in an effort to obtain sufficient participation from people who have received counseling. In addition, requested participation through two research boards of counseling associations (Academy of Eating Disorders and International Association of Eating Disorder Professionals) allowed us to recruit sufficient participation from previous clients with EDs, as well as other diagnoses, as we requested they send the survey to their former clients. Second, to obtain participation from people with and without experience in counseling, Biang posted calls for participation on social media accounts (i.e., Instagram and Facebook). Third, to further increase participation, Merlin-Knoblich forwarded a participation request to their university’s counseling program listserv. After 2 weeks of data collection, we sent a second follow-up call for participation and then continued data collection for an additional week.

To prevent recruitment bias and confirmation bias during data collection, we omitted the terms weight and weight bias and modified the study title to read “Counselor Attributes that Impact Client’s Selection, Trust, and Advice Following.” The call for participation informed potential participants that we were conducting a study about the attributes of a hypothetical counselor. The end of the questionnaire contained a full disclosure of the study’s purpose. Of the 255 participants who began the study questionnaire, 189 completed the study, representing a 74% completion rate. No data was collected from the 66 non-completers other than an average of 76 seconds with the survey open before ending the survey.

Participants

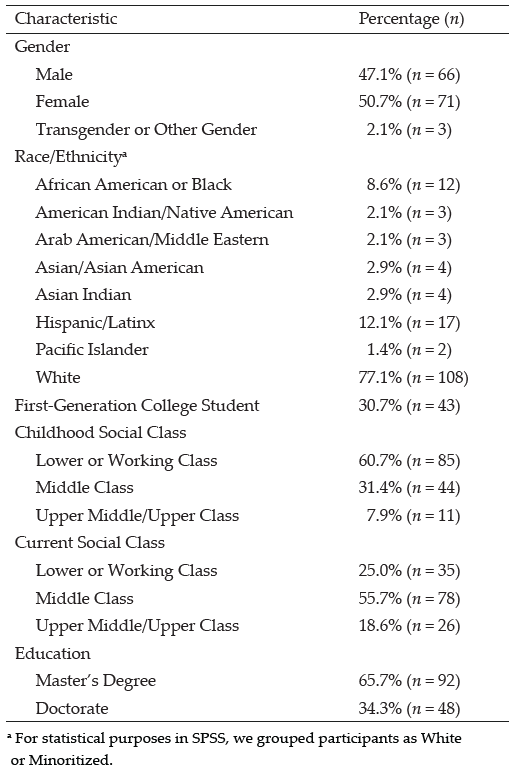

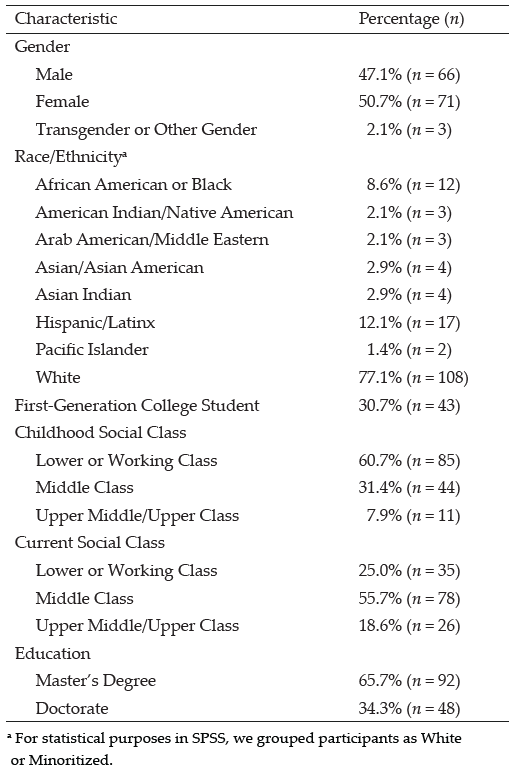

A sample of 189 participants from 26 states participated in the study. Table 1 presents a summary of the sample characteristics. The majority of participants were from North Carolina (n = 72, 38%),

Ohio (n = 23, 12%), California (n = 19, 10%), Utah (n = 11, 6%), and New York (n = 10, 5%). Participants primarily identified as female (n = 158, 84%). The majority of participants identified as White (n = 153, 81.4%), with other participants identifying as Asian (n = 13, 6.9%), Black/African American (n = 12, 6.4%), Latine/Hispanic (n = 5, 2.7%), and American Indian (n = 3, 1.6%). The majority of participants were over the age of 30 (n = 139, 74%), more than half had previously participated in personal counseling (n = 135, 71.8%), and just over a quarter indicated a previous ED diagnosis (n = 52, 27.7%).

Given the focus of this study, all participants were asked to indicate their height and weight but were informed that such information (like all demographic information) was optional to submit. One hundred and eighty-four participants (97%) shared their height and weight, from which we calculated their BMI—a person’s weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. The mean BMI was 28 (SD = 6.8) among the participants who shared their height and weight. This BMI is designated as “overweight” by the CDC (2022).

Study Design and Instrumentation

Physician Weight Survey Revised

We used a quasi-experimental research design in this study. With permission from Puhl and colleagues (2013), we revised the Physician Weight Survey (PWS), a 44-item questionnaire designed to assess patient weight bias of physicians who are obese, overweight, or seen as average weight. The instrument measures five constructs: physician health behaviors, physician selection, physician compassion, physician trust, and adherence to physician advice. Cronbach’s alpha tests instrument reliability and the internal consistency of the questions on a scale. Alpha scores over .70 are considered acceptable (Taber, 2018). Each subscale of the PWS has demonstrated sufficient internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of at least .90 (Puhl et al., 2013).

We adapted the questionnaire to address participants’ willingness to trust, follow the advice of, and select a hypothetical counselor based on the weight of that counselor. We replaced the term, physician with counselor and added the underweight category instead of the obese category. Using the underweight category allowed for consideration that weight bias exists on both ends of the weight spectrum. Because

of differences in occupational responsibilities and limiting the dependent variables of our study, we did not use the subscales for health behaviors or compassion. The Health Behavior subscale incorporated the physicians’ use of substances, health screenings, and illness prevention. The Compassion subscale measured the physician’s bedside manner. Without those two additional subscales, our revised measure had 23 items.

Table 1

Participant Demographic Data

| Demographics |

n |

% |

| Gender |

|

|

| Female |

158 |

84.0 |

| Male |

27 |

14.4 |

| Non-Binary |

1 |

0.05 |

| Race/Ethnicity |

|

|

| White |

153 |

81.4 |

| Black/African American |

12 |

6.4 |

| Latine/Hispanic |

5 |

2.7 |

| Asian |

13 |

6.9 |

| American Indian |

3 |

1.6 |

| Age Range |

|

|

| 18–29 |

48 |

25.6 |

| 30–42 |

64 |

34.1 |

| 43 and older |

74 |

39.4 |

| Prior History of Counseling |

|

|

| Yes |

135 |

71.8 |

| No |

51 |

27.1 |

| Prior History of Eating Disorder |

|

|

| Yes |

52 |

27.7 |

| No |

134 |

74.3 |

| BMI Range |

|

|

| Underweight |

4 |

2.1 |

| Average |

64 |

34.0 |

| Overweight |

54 |

28.7 |

| Obese |

60 |

31.9 |

Note. N = 189.

The subscales of Counselor Trust and Counselor Selection align well with our study. The subscale of Advice Following may seem counterintuitive when used with the counseling profession. The term advice equates to the construct of counseling together and incorporates the concept of counselors helping clients create and follow treatment goals, exploring ideas together for change, and even assigning homework. Advice aligns with how clients perceive what counselors do rather than the skills they use. For example, counselors using motivational interviewing and questions such as “What would it take for you to go from a 2 to a 4 in your willingness to reduce your alcohol consumption?” can be seen as advising clients to reduce their alcohol consumption. We chose to use the term advice instead of counsel so all participants, regardless of their experience with counseling, would understand the questions.

Parallel to Puhl and colleagues’ (2013) study, we then created three different versions of the questionnaire. Using Qualtrics, an electronic survey platform, consenting participants received a random assignment to one of three questionnaire versions. Seventy (37%) of the study participants completed the first version of the questionnaire, which described a hypothetical counselor as an overweight counselor. Fifty-eight (31%) participants completed the second questionnaire version, which described a hypothetical counselor as having average weight. And 61 (32%) of the participants completed the third version of the questionnaire, which described a hypothetical counselor as underweight. Participants responded to all items on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree/extremely unlikely) to 7 (strongly agree/extremely likely), with seven questions reverse scored.

Counselor Trust Subscale. The Counselor Trust subscale of the revised PWS consisted of nine questions focused on skills and competence (e.g., “If my counselor was [overweight/underweight/average weight], I would not trust them,” and “If my counselor was [overweight/underweight/average weight], I would have doubts about their credibility”). Other questions focused on believing the counselor would listen or understand their needs (e.g., “I believe an [overweight/underweight/average weight] counselor would listen carefully to what I have to say”). The scale demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .81) with this sample. Higher scores reflect greater trust in the counselor.

Counselor Advice Following Subscale. The Advice Following subscale contained six items. These items indicated making changes to diet, losing weight, and advice in general (e.g., “In general, my counselor’s weight affects whether I listen to their advice” and “If my counselor were [overweight/underweight/average weight], I would feel embarrassed when talking about losing weight”). Though counselors are not medical doctors, many clients explore topics associated with their bodies, exercise, and overall physical health (e.g., sleep issues, pain management, substance use, and daily routines), indicating relevance to counseling for the survey questions. Higher scores suggest more willingness to follow the advice (counsel) of the counselor. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .83 with this sample.

Counselor Selection Subscale. The Counselor Selection subscale had seven items indicating a willingness to select the counselor based on their appearance of weight (e.g., “If I went to a new counselor, and the counselor appeared [overweight/underweight/average weight], I would change counselors,” or “If my counselor was [overweight/underweight/average weight], I would not recommend them to my friends”). Similar to the other subscales, higher scores indicate more willingness to select the counselor. For this sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .71.

Antifat Attitudes Questionnaire

In addition to the revised PWS, participants completed the Antifat Attitudes Questionnaire (AFA; Crandall, 1994). The AFA assesses participants’ beliefs about overweight people and their feelings about becoming overweight. Three subscales, Dislike (α = .84), Fear of Fat (α = .79), and Willpower (α = .66), are combined for a composite antifat attitude score. Despite the low Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the Willpower subscale, it positively correlates with the Dislike subscale (r = .43, p < .001), whereas the Fear of Fat subscale remains uncorrelated with both subscales, suggesting discriminate validity (Lacroix et al., 2017; Ruggs et al., 2010). Both the reliability and validity of the AFA have been extensively assessed by researchers, and the AFA has been found to be a psychometrically sound measure (Ruggs et al., 2010). The Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency reliability was acceptable, with a value of .87 for the data used in the current study. Participants indicated agreement (e.g., “I really don’t like fat people much”) on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), with higher composite scores suggesting stronger negative antifat attitudes. Higher scores may correlate to weight bias toward the overweight counselor. Scores on the Fear of Fat subscale are directed toward a personal antifat fear and not toward others.

The AFA was also used to test the equivalence of groups and any effect of social desirability. Lastly, participants completed a voluntary 8-item demographic questionnaire describing their race/ethnicity, age, gender, height, weight, and experience with receiving counseling or having an ED.

Data Analysis

We conducted all analyses using SPSS Version 27. The first analysis had the four dependent variables of Counselor Trust, Counselor Selection, Advice Following, and Weight Bias, with the independent variable of Weight (overweight, underweight, and average weight). We conducted a series of assumption-checking procedures to draw valid interpretations of the findings. Engaging the Shapiro-Wilk test as a test of normality yielded a significant result (W = 0.92, p < .001) for the overweight counselor, indicating the sample was not normally distributed. After removing outliers, the sample for the overweight survey condition did not meet the assumption of normality. A test for homogeneity of variance yielded a statistically significant Levine’s score of F(2, 168) = .46, p = .013; degrees of freedom were adjusted due to unequal sample sizes for each survey condition.

Conducting a MANOVA yielded statistically significant results; however, not meeting the assumptions of multivariate normality and homogeneity of variance required, we used the Welch ANOVA, which is recommended for non-normal distributions. Using a Welch ANOVA is also a best practice when the homogeneity of variances test fails; it controls the type I error and gives more power in many instances (Liu, 2015). Although a parametric test such as a typical ANOVA or MANOVA is known to be more powerful than a non-parametric test (e.g., Welch ANOVA), it can lead to erroneous results if required assumptions are not satisfactorily met (Zar, 1998). Considering unequal variances and sample sizes across groups, we used Games-Howell for post hoc testing. We used G*Power version 3.1.9.7 (Faul et al., 2007) to perform the power analysis. For the Welch ANOVA test, the minimum sample size was 157, with a medium effect size of .25, a desired statistical power level of .8, and an alpha level of .05. Lastly, we measured the effect size using partial eta squared (ꞃ²), showing the strength of association as a proportion of variance in the dependent variable explained by group membership (Coladarci et al., 2011).

Table 2

Descriptive Statistics for Outcome Variables

|

n |

Mean |

Std.

Deviation |

Std. Error |

95% Confidence Interval for Mean |

Minimum |

Maximum |

| Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

| Trust |

OW |

70 |

49.70 |

9.89 |

1.18 |

47.34 |

52.06 |

16.00 |

63.00 |

| UW |

59 |

41.15 |

10.72 |

1.40 |

38.36 |

43.95 |

17.00 |

63.00 |

| AW |

60 |

47.48 |

7.75 |

1.00 |

45.48 |

49.49 |

29.00 |

63.00 |

| Total |

189 |

46.33 |

10.16 |

0.74 |

44.87 |

47.79 |

16.00 |

63.00 |

| Selection |

OW |

70 |

32.41 |

5.40 |

0.64 |

31.13 |

33.70 |

19.00 |

40.00 |

| UW |

59 |

30.00 |

5.12 |

0.67 |

28.67 |

31.33 |

21.00 |

40.00 |

| AW |

60 |

31.42 |

4.92 |

0.63 |

30.15 |

32.69 |

16.00 |

40.00 |

| Total |

189 |

31.34 |

5.23 |

0.38 |

30.59 |

32.09 |

16.00 |

40.00 |

| Advice |

OW |

70 |

25.76 |

8.72 |

1.04 |

23.68 |

27.84 |

8.00 |

42.00 |

| UW |

59 |

24.73 |

7.33 |

0.95 |

22.82 |

26.64 |

8.00 |

42.00 |

| AW |

60 |

31.93 |

4.64 |

0.60 |

30.73 |

33.13 |

23.00 |

42.00 |

| Total |

189 |

27.40 |

7.81 |

0.57 |

26.28 |

28.52 |

8.00 |

42.00 |

| Note. OW = overweight; UW = underweight; AW = average weight. |

In the second data analysis, we used the Pearson correlation to assess an association between data sets from the AFA and Composite Weight Bias. Composite Weight Bias was calculated by summing the scales of the revised PWS. Before computing a correlation, we examined the scatter plot between the independent and dependent variables to check the linearity between the two variables and the existence of outliers. We found less than three outliers on all four graphs and identified negative linearity. Using G*Power (Faul et al., 2007), we obtained the estimated sample size necessary to run the correlation analysis, which was 64 with a medium effect size of .3, an alpha level of .05, and power of .8. Lastly, we explored the relationships between demographics and weight bias toward counselors using a one-way ANOVA or an independent t-test. We selected statistical methods based on the number of categories of each demographic variable. See Table 2 for descriptive statistics of the outcome variables.

Results

Areas of Trust, Advice, and Selection

We found significantly different levels of trust, advice following, and counselor selection behaviors among participants assigned to hypothetical counselors of different weights.

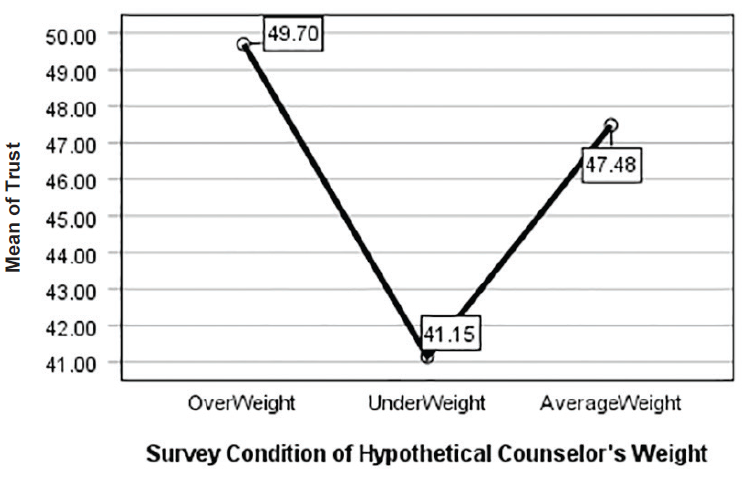

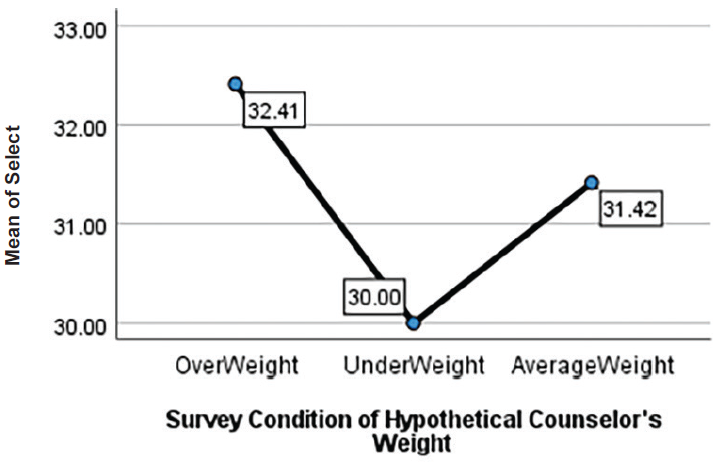

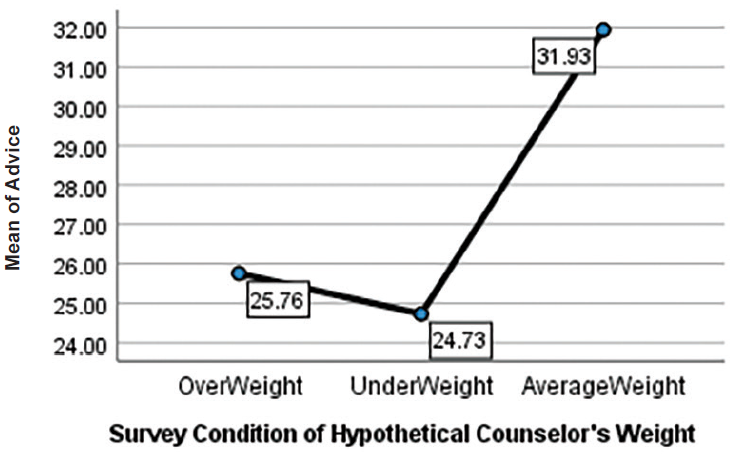

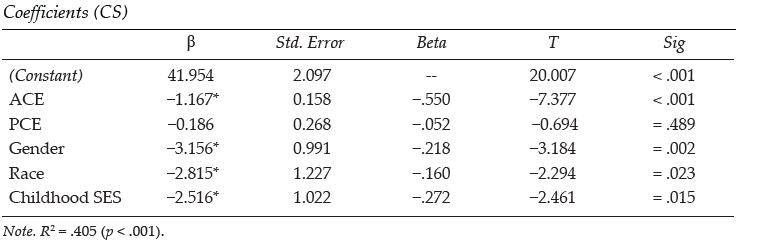

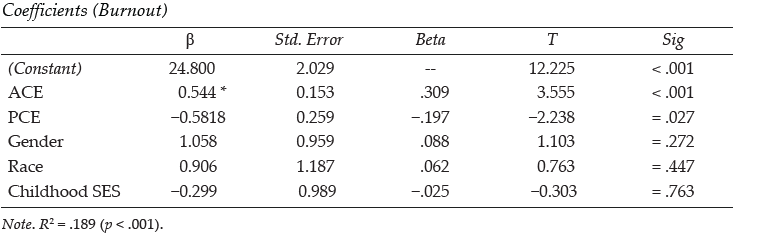

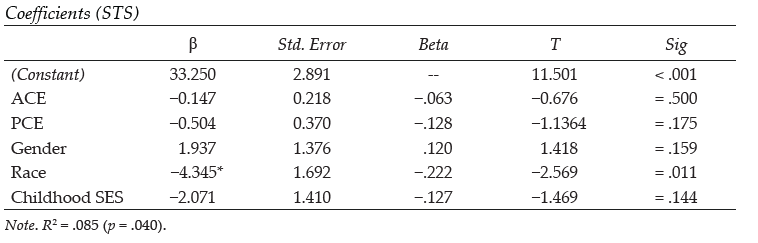

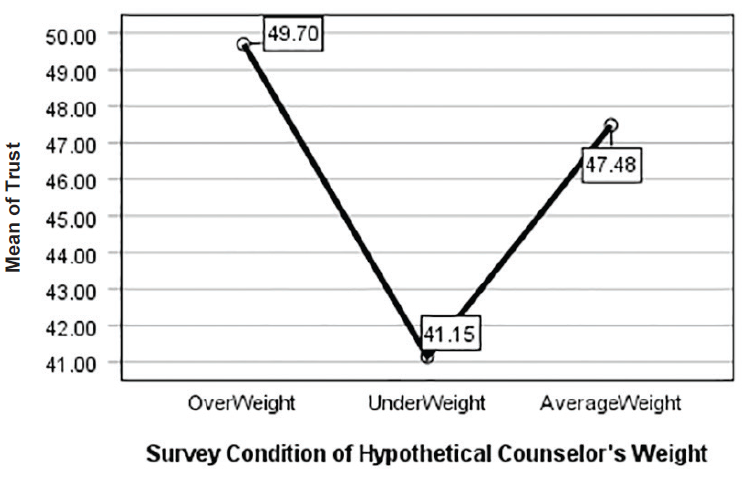

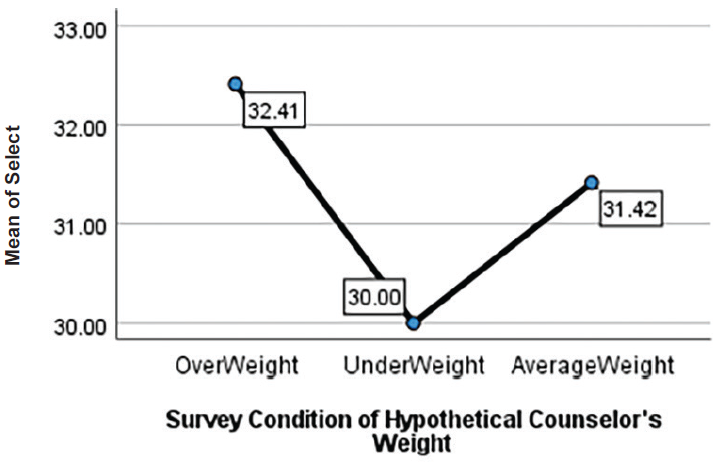

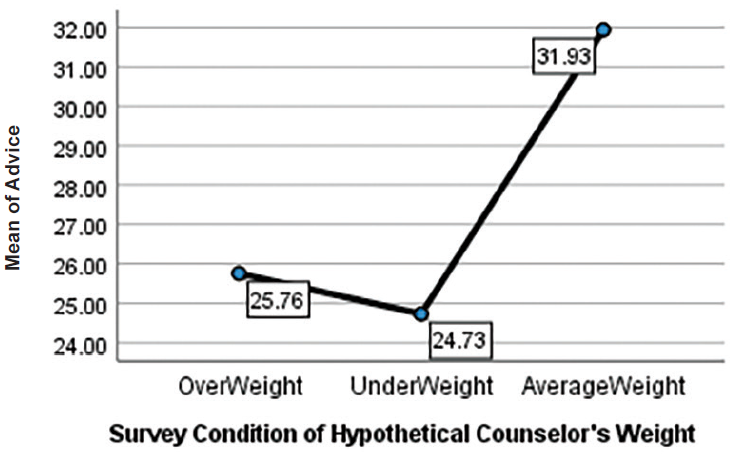

Welch ANOVA test results indicated a statistical significance in all three areas between groups, F(2, 120.60) = 12.89, p < .001 with a medium effect size (ꞃ² = .11). Post hoc comparisons using Games-Howell showed the following results at the significance level of α = .05. Counselor Trust for average-weight counselors (M = 47.48, SD = 7.75) was significantly higher than Counselor Trust for underweight counselors (M = 41.15, SD = 10.72) at p = .001. Counselor Trust of overweight counselors (M = 49.70, SD = 9.89) was also significantly higher than Counselor Trust for underweight counselors at p < .001. There was no statistical significance for Counselor Trust between average and overweight counselors. Advice Following for average-weight counselors (M = 31.93, SD = 4.65) was significantly higher than Advice Following for underweight counselors (M = 24.72, SD = 7.28) and Advice Following for overweight counselors (M = 25.75, SD = 8.72) at p < .001 for both. Finally, Counselor Selection for an overweight counselor (M = 32.41, SD = 5.73) was statistically higher than Counselor Selection for an underweight counselor (M = 30.00, SD = 5.59) with p = .028. There was no statistical significance in the Counselor Selection of average-weight counselors (M = 31.41, SD = 4.91) compared to overweight or underweight counselors. See Table 3 and Figures 1–3.

Next, we conducted a Welch ANOVA between overall composite scores and the three weight groups (see Table 4). Again, Welch test results indicated a statistical significance between groups, F(2, 118.73) = 11.71, p < .001 with a medium effect size (² = .10). Post hoc comparisons using Games-Howell showed statistical significance between overweight counselors (M = 107.87, SD = 21.68) and underweight counselors (M = 95.88, SD = 20.00). Underweight counselors were also significantly lower on the overall composite than average-weight counselors (M = 110.83, SD = 19.97). There was no statistical significance between overweight and average-weight counselors for their overall composite scores, which include all three variables.

Figure 1

Willingness to Trust Counselor

Figure 2

Willingness to Select Counselor

Figure 3

Following Counselor Advice

Table 3

Post Hoc Outcome Variables

|

| Dependent Variable |

Mean Difference (I-J) |

Std. Error |

Sig. |

95% Confidence Interval |

| Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

| Trust |

OW |

UW |

8.547a |

1.829 |

0.00 |

4.206 |

12.888 |

| AW |

2.216 |

1.548 |

0.32 |

−1.456 |

5.889 |

| UW |

OW |

−8.547a |

1.829 |

0.00 |

−12.888 |

−4.206 |

| AW |

−6.330a |

1.717 |

0.00 |

−10.414 |

−2.247 |

| AW |

OW |

−2.216 |

1.548 |

0.32 |

−5.889 |

1.456 |

| UW |

6.330a |

1.717 |

0.00 |

2.247 |

10.414 |

| Selection |

OW |

UW |

2.414a |

0.927 |

0.02 |

0.215 |

4.613 |

| AW |

0.997 |

0.904 |

0.51 |

−1.144 |

3.143 |

| UW |

OW |

−2.414a |

0.927 |

0.02 |

−4.613 |

−0.215 |

| AW |

−1.416 |

0.920 |

0.27 |

−3.601 |

0.767 |

| AW |

OW |

−0.997 |

0.904 |

0.51 |

−3.143 |

1.148 |

| UW |

1.416 |

0.920 |

0.27 |

−0.767 |

3.601 |

| Advice |

OW |

UW |

1.028 |

1.413 |

0.74 |

−2.323 |

4.379 |

| AW |

−6.176a |

1.202 |

0.00 |

−9.034 |

−3.313 |

| UW |

OW |

−1.028 |

1.413 |

0.74 |

−4.379 |

2.323 |

| AW |

−7.204a |

1.126 |

0.00 |

−9.885 |

−4.523 |

| AW |

OW |

6.176a |

1.202 |

0.00 |

3.318 |

9.034 |

| UW |

7.204a |

1.126 |

0.00 |

4.523 |

9.885 |

| Note. The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level. OW = overweight; UW = underweight; AW = average weight. Welch’s ANOVAs with Games-Howell post hoc tests were run owing to violations of the equality of variances assumption. |

Table 4

Post Hoc Composite Weight Bias

|

| (I) Group |

Mean Difference (I-J) |

Std. Error |

Sig. |

95% Confidence Interval |

| Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

| OW |

UW |

11.99a |

3.67 |

0.004 |

3.28 |

20.70 |

| AW |

−2.96 |

3.09 |

0.604 |

−10.29 |

4.36 |

| UW |

OW |

−11.99a |

3.67 |

0.004 |

−20.70 |

−3.28 |

| AW |

−14.95a |

3.10 |

0.000 |

−22.32 |

−7.58 |

| AW |

OW |

2.96 |

3.09 |

0.604 |

−4.36 |

10.29 |

| UW |

14.95a |

3.10 |

0.000 |

7.58 |

22.32 |

| Note. The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level. OW = overweight; UW = underweight; AW = average weight. Welch’s ANOVAs with Games-Howell post hoc tests were run owing to violations of the equality of variances assumption. |

|

In addition to statistical significance, we also examined effect size to quantify the significance found. Results indicated that Advice Following showed a large effect of association with the independent variable of Weight (² = .16). Counselor Trust had a medium effect size (² = .13), and Counselor Selection yielded a small effect size (² = .04). These results suggest that the weight of a counselor has a high association with clients following counselor advice, with average-weight counselors faring the best. Additionally, participants indicated they would trust average and overweight counselors more than underweight counselors. Lastly, overweight counselors were more favorable in Counselor Selection than underweight counselors.

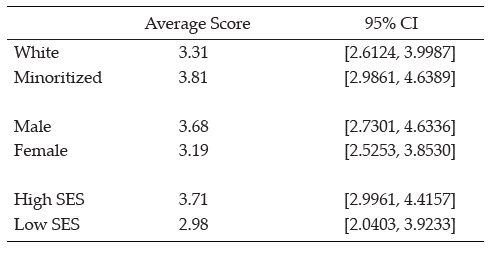

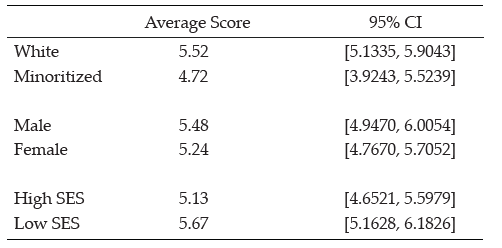

Antifat Attitudes and a Correlation With Counselor Trust, Advice Following, and Counselor Selection

We used Pearson correlations to examine associations between antifat attitudes and weight bias toward counselors (see Table 5). To do so, we examined data from participants assigned to all three counselor conditions in the study. Each group showed a significant relationship between antifat attitudes and weight bias toward counselors; thus, we combined data to attain a larger sample size. The Pearson correlations between the independent variable of antifat attitudes and dependent variables of Counselor Trust, Advice Following, Counselor Selection, and Composite Weight Bias score were significant at α = .05. We found positive correlations between antifat attitudes and Counselor Selection, r(186) = .400, p < .001, and Counselor Trust, r(186) = .211, p = .004. These results indicate that as antifat attitudes increase, participants’ trust in and selection of a counselor based on weight also increase. We found no significant correlation between Advice Following and Composite Weight Bias score with antifat attitudes.

Table 5

Correlation of AFA With Outcome Variables |

|

|

|

|

|

|

AFA |

Trust |

Selection |

| AFA |

Pearson Correlation |

1.000 |

0.211** |

0.400** |

| Sig. |

|

0.004 |

0.000 |

| N |

188.000 |

188.000 |

188.000 |

| Trust |

Pearson Correlation |

0.211** |

1.000 |

0.349** |

| Sig. |

0.004 |

|

0.000 |

| N |

188.000 |

188.000 |

188.000 |

| Selection |

Pearson Correlation |

0.400** |

0.349** |

1.000 |

| Sig. |

0.000 |

0.000 |

|

| N |

188.000 |

188.000 |

188.000 |

Note. AFA = Antifat Attitude. Advice was not statistically significantly correlated with AFA. One participant of the total study sample (N = 189) did not complete this portion and is not included in the table.

*Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed). |

Socio-Demographic Categories

We found no statistically significant differences in weight bias toward counselors based on ethnicity F(4, 181) = .037, p = .997; age F(4, 181) = 1.71, p = .149; BMI F(4, 177) = .193, p = .942; counseling status t(184) = .798, p = .426; eating disorder t(184) = 1.055. p = .137; or gender F(2, 183) = 1.423, p = .426. Additionally, we tested for Pearson correlations between BMI and antifat attitudes. Results indicated that BMI and antifat attitudes had no significant correlation, r(N = 187) = .004, p = .958.

Antifat Attitudes by Survey Condition

To test for undue influence from survey design or responses that stem from social desirability, we ran an ANOVA comparing participants in each questionnaire condition (i.e., underweight, average weight, and overweight counselor) and their scores on the AFA. We found no statistically significant differences between the three groups, F(2, 181) = 2.74, p = .067. For the AFA scores, M = 40.22 and SD = 12.57. However, with the results of the AFA correlation with Counselor Trust and Counselor Selection, these findings may indicate that there was social desirability across all three survey conditions.

Discussion

Contrary to previous research from McKee and Smouse (1983) that suggested counselors of any weight could address personal concerns, our study results indicated that clients might use weight to select a counselor, trust the counselors’ skills, and follow their counsel. When asked about weight, participants in this study slightly preferred to select and trust the average-weight and overweight counselors, with weight bias directed mainly at the underweight counselor. Like previous research about weight bias toward physicians (Puhl et al., 2013) and personal trainers (Hutson, 2013), our results showed some weight bias toward overweight counselors when following advice. For underweight counselors, weight bias was present in all three subscales and mirrored findings that underweight persons are not immune to weight discrimination (Beggan & DeAngelis, 2015).

Overweight Counselors

Our results yielded only one finding that supported the theme from Moller and Tischner’s (2019) study that “fat counselors cannot help” (p. 14). Statistically significant results from the present study showed less willingness to follow the advice of overweight counselors. Similar to the findings from Puhl et al. (2013), taking advice or counsel from an overweight health care professional may prove more difficult than trusting they can perform their job or being willing to work with them. With two-thirds of adults in the United States considered overweight or obese (CDC, 2022), these findings may reflect cause for concern that some clients may not perceive competence in counselors who are overweight.

The correlation between the AFA with Counselor Trust and Counselor Selection can give insight into the findings. The positive correlation between AFA and Counselor Trust was low but significant. With 60% of participants in the overweight-to-obese category, there could be an underlying factor that needs further exploration. There was no correlation between BMI and AFA. However, as Schwartz et al. (2006) suggested, overweight people have similar antifat attitudes as average-weight individuals. The slight correlation potentially relates to most participants having larger bodies and knowing that being in larger bodies does not equate to untrustworthiness. Likewise, for Counselor Selection, we should consider the concept of similar attraction. This concept posits that people associate with those perceived as similar to them and who have similar physical attributes (Montoya & Horton, 2013). Relating to this concept of similar attraction, the positive correlation between AFA and Counselor Selection could be attributed to the high percentage of larger-body participants feeling more comfortable selecting the overweight counselor.

Unlike findings from other studies (Moller & Tischner, 2019; Puhl et al., 2013), our results did not indicate that Counselor Trust or Counselor Selection were negatively related to being overweight. However, when looking at the Advice Following subscale, there was a marked difference in the scores. The hypothetical overweight counselor had higher mean scores than underweight counselors on all three subscales and overall composite scores. On the upside, weight may not be an issue for many clients seeking counseling. Despite continued weight bias and stigma in social media and society, people might recognize that overweight counselors’ skills and knowledge are more important than perceived body weight. On the downside, clients may hesitate to follow counsel associated with issues concerning their own physical well-being from a perceived overweight counselor. To combat this, counselors need to be willing to broach the issue of weight if they feel it is hindering the therapeutic alliance. Similar to other multicultural topics, differences in body weight between the counselor and client may be a potential barrier for the free expression of client concerns. The willingness of the counselor to explore this topic may put the client at ease and make them able to further explore their concerns in a nonjudgmental, therapeutic manner.

Underweight Counselors

We found surprising results suggesting that participants in our study would prefer an overweight or average-weight counselor to an underweight counselor. Participants scored counselors perceived as underweight significantly lower on a client’s willingness to select, trust, and follow a counselor’s advice than average-weight and overweight counselors. These results supported the decision to add this variable to our study and indicate the need for more research on weight bias toward underweight professionals.

The underweight variable yielded results that complement previous research on weight bias, indicating that people can be biased against underweight professionals (Allison & Lee, 2015; Davies et al., 2020b). Because of the persistent social desirability to be thin or underweight, research indicates that people may be pro-underweight on an explicit level; however, they implicitly prefer an average-weight person (Marini, 2017). In our findings, participants somewhat preferred to select an overweight counselor instead of an underweight counselor, upholding the notion that people do not necessarily trust those who are underweight despite the social pressure to be thin. This result highlights a striking mismatch in thought: people may prefer to be underweight because of social pressures but not fully trust an underweight counselor. It could indicate that societal pressures to be underweight are not as strong as once thought or it may suggest that people possess complicated views on being underweight in general.

These results reflect those found by Marini (2017), in which individuals implicitly preferred an overweight individual over an underweight individual, implying maladaptive behaviors and dangerous consequences. Additionally, with body positivity and body acceptance movements, underweight persons may be overlooked as recipients of negative weight bias (Beggan & DeAngelis, 2015). These results may give underweight counselors pause about how clients perceive them in session and the notion that experiences of thin privilege may not transfer into their professional identity. In response to these possible perceptions from clients, underweight counselors may benefit from seeking professional supervision or consulting with colleagues about the topic.

Antifat Attitudes

The AFA results indicated that as a person’s negative attitudes toward overweight people decrease, they disregard weight as a factor for selecting and trusting the skills of counselors. Currently, there is no measure for anti-thin attitudes to analyze whether this bias would yield similar results. Despite the lack of an anti-thin measure, these results reiterate the belief that we judge others based on what attributes are important to us or differentiate us from others (Cermák et al., 1993). When body weight is not an attribute of self-judgment, a person may not use it as a criterion toward others or in working with professionals. As a profession, we must continue supporting movements that promote acceptance of all bodies and destigmatize weight. With strong social media campaigns against weight bias, we can dispel the stereotypes about those who fall outside socially acceptable standards and replace them with acceptance.

Demographics

In addition to antifat attitudes, we chose to study socio-demographics because weight bias may fluctuate based on various group identities. Our results showed no statistically significant differences in age, gender, ethnicity, or BMI. These findings are relevant as they imply that weight bias may exist throughout all groups. However, we interpret these results cautiously, as the sample population was predominantly female, with fewer ethnically diverse participants, and more participation from people over 30. Notably, results for ethnicity were similar to previous research indicating that Black and White women had the same bias and weight stigma toward others who were overweight and underweight (Davies et al., 2020b).

Eating Disorder Consideration

Because of the nature of EDs, we added this category to the study to explore if a counselor’s weight would impact participants with an ED more. As counselors working with EDs often explore issues around weight, exercise, and eating concerns, we hypothesized that these participants might have a higher bias toward underweight and overweight counselors. We found that participants with EDs were not significantly different from participants without EDs in weight bias toward counselors in any of the variables. This finding is favorable information for counselors in this specialty, as it does not align with the findings from Moller and Tischner (2019) that suggest that the weight of a counselor is a barrier to treatment.

Experience of Counseling

A final surprising finding revealed in our results was that people with previous counseling experience had similar levels of weight bias to those who had not worked with a counselor. Participants who previously participated in counseling may recognize attributes, such as expertise, empathy, and compassion of a counselor, as more valuable in their relationship than weight. Because attributes such as genuineness, empathy, unconditional positive regard (Nienhuis et al., 2018) build the therapeutic relationship, it is feasible to see counselor weight as a non-factor. However, we found that prior experience in counseling did not mediate the weight bias participants demonstrated. This result gives room for concern that weight bias may diminish the initial value of core conditions and counselor attributes studied in the past. Perhaps weight bias is pervasive in the decision to work with a counselor.

Implications

Despite years of education and experience, weight bias may rule out competent counselors. Professionals who fall outside the average body weight are hyper-visible (Beggan & DeAngelis, 2015) and prone to judgment of their weight. This study fills a gap in the research pertaining to the way weight bias influences a client’s willingness to trust, follow counselor advice, and select their counselors. Knowing how weight bias impacts the counseling profession can help counselors become aware of an issue that may affect the therapeutic alliance. In response to the study results, we identified two key implications for the counseling profession.

First, the results are indicative of a multicultural issue. Many people see weight as a medical concern instead of a social justice issue (Christensen, 2021). This idea limits the amount of education and training counseling graduate students receive on the topic of weight, leading to the request to address weight in multicultural courses as a core topic. Weight becomes intersectional among identities, and counselors must train to be sensitive to and inclusive of the topic of weight. Broaching weight may feel uncomfortable but be necessary to strengthen the therapeutic relationship.

Second, recognizing that weight bias may impact a client’s willingness to select, follow the counsel of, or trust a counselor reiterates the importance of knowing the factors influencing the counseling relationship. Counselors should acknowledge that stereotypes, discrimination, and oppression influence the counseling relationship (Ratts et al., 2016). Counselors should not ignore weight bias as a possible stereotype and should be comfortable discussing it with their clients. Additionally, the multicultural competencies note that “Counselors know when to initiate discussions with regard to the influences of identity development, power, privilege, and oppression within the counseling relationship” (Ratts et al., 2016, p. 41). As society continues to push the thin ideal while simultaneously pushing body acceptance at any size, these contradictory messages will keep weight bias at the forefront of how others are judged.

Until weight bias is erased, counselors must be vigilant in understanding how they show up in the session, what message a client may perceive by their body weight, and how to broach the topic to strengthen the therapeutic alliance. If counselors seek to help reduce weight bias in society, they may benefit from reflecting on their own biases, privileges, and experiences with oppression in this area. They also may consider challenging potential biases through professional development, group or individual counseling supervision, or literature about weight bias in society.

Limitations

Like all studies, this study contains limitations. One limitation is the subjectivity of weight. Without guidelines for what constitutes overweight and underweight, this study heavily relied on participants’ perceptions of these variables, which may be inconsistent across participants. Not specifying these variables opened interpretation for the overlapping areas of overweight versus obese or underweight versus extremely thin. Participants in each treatment condition may have visualized different hypothetical counselors than peers in the same treatment group. Using images may improve the specificity of the variable in future studies.

Additionally, there was no identified gender for the hypothetical counselors in each treatment condition, allowing participants to visualize any gender of counselor they chose. This lack of specificity may have created a moderating variable. Women represent higher numbers in the counseling profession. Women experience more discrimination than men (McHugh & Kasardo, 2012; Roehling et al., 2007), and it is unknown if people who identify as gender non-binary experience more or less weight bias. By not distinguishing the gender of the counselor, our ability to make inferences across genders is limited. Creating a study that specifies multiple genders may yield more representative results.

Another limitation is that a non-parametric test (e.g., Welch’s ANOVA) was used instead of parametric tests with more statistical power. The decision to use the non-parametric test was unavoidable because of violating the required assumptions. At the same time, future research may corroborate our findings using a parametric test if data allow. Future research may also replicate this study using multivariate ANOVA (MANOVA), which considers correlations of dependent variables.

Lastly, social desirability and self-reporting may have impacted responses. While completing the questionnaire, feelings about weight bias may have occurred outside of participants’ awareness, causing cognitive dissonance. To resolve this dissonance, responses may have overtly favored accepting the overweight counselor or selecting fewer negative answers on the AFA. Participants also reported their own weight bias, which may have presented a self-report limitation. The results of overweight counselors having higher mean scores on Trust and Selection than average-weight counselors give room for consideration that social desirability may have influenced some of the participants’ answers. Future studies may benefit from including a test for social desirability or implicit association tests to increase the study’s validity.

Future Considerations

Future considerations for research encompassing weight bias across the spectrum would require developing an anti-thin attitude measure to identify weight attitudes toward underweight individuals accurately. This measure would be beneficial for bringing more awareness to underweight discrimination and measuring its impact on professionals and members of society. As society continues to push the thin ideal, people will strive to fit that ideal. However, as our results suggest, underweight counselors may face significant weight bias from clients. Consequently, counselors would benefit from a measure created to address underweight bias.

The counseling profession lacks extensive, meaningful research regarding the physical and educational factors that clients find most important in selecting, trusting, and following the advice of a counselor. Another factor to incorporate in future research is a counselor’s level of education and expertise. Clients may more favorably evaluate an average weight counselor with a specialist or doctoral degree than an underweight or overweight colleague with the same credentials. If weight bias influences these variables despite the skill level of the counselor, clients may miss receiving help from highly trained and educated people. Additionally, directly exploring the role that empathy, congruence, and strengths-based counseling have compared to weight bias may yield significant findings.

A final consideration for future research involves focusing on counselors who work in the ED field, a specialty that deals with eating, weight, body image, and exercise. Though we did not find significant differences in this study between those with and without an ED, our hypothetical counselor was not an ED counselor. These counselors may experience more judgment and assumptions of lifestyle choices by their clients, as they are considered specialists in EDs. Studies show that being underweight may indicate an ED, such as anorexia or binge eating disorder (Davies et al., 2020a; Marini, 2017). It is unknown if clients would replicate the results found in this study regarding counselors in the ED field.

Conclusion

This study examined participants’ weight bias toward hypothetical counselors of different weights. Our results highlight the existence of weight bias toward counselors on both ends of the weight spectrum. Even with strengthening the counseling relationship through empathy, congruence, and unconditional positive regard, counselors may benefit from reflecting on potential client weight bias and its impact on their therapeutic alliance. Additionally, weight as a multicultural issue increases counselors’ competence in addressing the prejudice and stereotypes that may limit their client’s willingness to trust them, follow their advice, or select them as their counselor.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Ackerman, S. J., & Hilsenroth, M. J. (2001). A review of therapist characteristics and techniques negatively impacting the therapeutic alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 38(2), 171–185.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.38.2.171

Allen, M. L., Cook, B. L., Carson, N., Interian, A., La Roche, M., & Alegría, M. (2017). Patient-provider therapeutic alliance contributes to patient activation in community mental health clinics. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 44(4), 431–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-015-0655-8

Allison, M., & Lee, C. (2015). Too fat too thin: Understanding bias against overweight and underweight in an Australian female university student sample. Psychology & Health, 30(2), 189–202.

https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2014.954575

Beggan, J. K., & DeAngelis, M. (2015). “Oh, my God, I hate you”: The felt experience of being othered for being thin. Symbolic Interaction, 38(3), 371–392. https://doi.org/10.1002/SYMB.162

Bucchianeri, M. M., Eisenberg, M. E., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2013). Weightism, racism, classism, and sexism: Shared forms of harassment in adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(1), 47–53.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.01.006

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, June 3). Defining adult overweight & obesity. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/basics/adult-defining.html

Cermák, I., Osecká, L., Rehulková, O., & Blatný, M. (1993). Judging others according to yourself: II. Interpersonal characteristics of personality and the structure of interpersonal attributions. Studia Psychologica, 35(2), 185. https://librarylink.uncc.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/judging-others-according-yourself-ii/docview/1306142557/se-2?accountid=14605

Christensen, K. N. (2021). Factors related to weight-bias among counselors (Order No. 28541740). Available from Dissertations & Theses @ University of North Carolina Charlotte. (2562239518).

Clabaugh, A., Karpinski, A., & Griffin, K. (2008). Body weight contingency of self-worth. Self and Identity, 7(4), 337–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860701665032

Clark, A. J. (2010). Empathy: An integral model in the counseling process. Journal of Counseling & Development, 88(3), 348–356. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00032.x

Coladarci, T., Cobb, C. D., Minium, E. W., & Clarke, R. B. (2011). Fundamentals of statistical reasoning in education (3rd ed.). Wiley.

Crandall, C. S. (1994). Prejudice against fat people: Ideology and self-interest. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(5), 882–894. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.66.5.882

Davies, A., Burnette, C. B., & Mazzeo, S. E. (2020a). Real women have (just the right) curves: Investigating anti-thin bias in college women. Eating and Weight Disorders, 25, 1711–1718.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00812-7

Davies, A., Burnette, C. B., & Mazzeo, S. (2020b). Black and White women’s attributions of women with underweight. Eating Behaviors, 39, 101446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2020.101446

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191.

https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Feller, C. P., & Cottone, R. R. (2003). The importance of empathy in the therapeutic alliance. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education and Development, 42(1), 53–61.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2164-490x.2003.tb00168.x

Grimes, W. R., & Murdock, N. L. (1989). Social influence revisited: Effects of counselor influence on outcome variables. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 26(4), 469–474. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0085465

Hauser, M., & Hays, D. G. (2010). The slaying of a beautiful hypothesis: The efficacy of counseling and the therapeutic process. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education and Development, 49(1), 32–44.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1939.2010.tb00085.x

Hinman, N. G., Burmeister, J. M., Kiefner, A. E., Borushok, J., & Carels, R. A. (2015). Stereotypical portrayals of obesity and the expression of implicit weight bias. Body Image, 12, 32–35.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.09.002

Hutson, D. J. (2013). “Your body is your business card”: Bodily capital and health authority in the fitness industry. Social Science & Medicine, 90, 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.05.003

Kim, E., & Kang, M. (2018). The effects of client–counselor racial matching on therapeutic outcome. Asia Pacific Education Review, 19(1), 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-018-9518-9

Kinavey, H., & Cool, C. (2019). The broken lens: How anti-fat bias in psychotherapy is harming our clients and what to do about it. Women & Therapy, 42(1–2), 116–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703149.2018.1524070

Lacroix, E., Alberga, A., Russell-Mathew, S., McLaren, L., & von Ranson, K. (2017). Weight bias: A systematic review of characteristics and psychometric properties of self-report questionnaires. Obesity Facts, 10(3), 223–237. https://doi.org/10.1159/000475716

Lewis, R. J., Cash, T. F., & Bubb-Lewis, C. (1997). Prejudice toward fat people: The development and validation of the Antifat Attitudes Test. Obesity Research, 5(4), 297–307. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1550-8528.1997.tb00555.x

Liu, H. (2015). Comparing Welch ANOVA, a Kruskal-Wallis test, and traditional ANOVA in case of heterogeneity of variance. https://doi.org/10.25772/BWFP-YE95

Lorr, M. (1965). Client perceptions of therapists: A study of the therapeutic relation. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 29(2), 146–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0021924

Marini, M. (2017). Underweight vs. overweight/obese: Which weight category do we prefer? Dissociation of weight-related preferences at the explicit and implicit level. Obesity Science & Practice, 3(4), 390–398. https://doi.org/10.1002/osp4.136

McHugh, M. C., & Kasardo, A. E. (2012). Anti-fat prejudice: The role of psychology in explication, education and eradication. Sex Roles, 66(9–10), 617–627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-0099-x

McKee, K., & Smouse, A. D. (1983). Clients’ perceptions of counselor expertness, attractiveness, and trustworthiness: Initial impact of counselor status and weight. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 30(3),

332–338. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.30.3.332

Meadows, A., & Daníelsdóttir, S. (2016). What’s in a word? On weight stigma and terminology. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1527. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01527

Meyer, O. L., & Zane, N. (2013). The influence of race and ethnicity in clients’ experiences of mental health treatment. Journal of Community Psychology, 41(7), 884–901. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21580

Moller, N., & Tischner, I. (2019). Young people’s perceptions of fat counsellors: “How can THAT help me?” Qualitative Research in Psychology, 16(1), 34–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2018.1536384

Montoya, R. M., & Horton, R. S. (2013). A meta-analytic investigation of the processes underlying the similarity-attraction effect. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 30(1), 64–94.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407512452989

Nienhuis, J. B., Owen, J., Valentine, J. C., Winkeljohn Black, S., Halford, T. C., Parazak, S. E., Budge, S., & Hilsenroth, M. (2018). Therapeutic alliance, empathy, and genuineness in individual adult psychotherapy: A meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy Research, 28(4), 593–605. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2016.1204023

Nutter, S., Russell-Mayhew, S., Arthur, N., & Ellard, J. H. (2018). Weight bias and social justice: Implications for education and practice. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 40(3), 213–226.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-018-9320-8

Puhl, R. M., Gold, J. A., Luedicke, J., & DePierre, J. A. (2013). The effect of physicians’ body weight on patient attitudes: Implications for physician selection, trust and adherence to medical advice. International Journal of Obesity, 37(11), 1415–1421. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2013.33

Puhl, R. M., & Heuer, C. A. (2010). Obesity stigma: Important considerations for public health. American Journal of Public Health, 100, 1019–1028. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.159491

Puhl, R. M., Latner, J. D., King, K. M., & Luedicke, J. (2014). Weight bias among professionals treating eating disorders: Attitudes about treatment and perceived patient outcomes. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47(1), 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22186

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar-McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2016). Multicultural and social justice counseling competencies: Guidelines for the counseling profession. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 44(1), 28–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmcd.12035

Roehling, M. V., Roehling, P. V., & Pichler, S. (2007). The relationship between body weight and perceived weight-related employment discrimination: The role of sex and race. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 71(2), 300–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2007.04.008

Ruggs, E. N., King, E. B., Hebl, M., & Fitzsimmons, M. (2010). Assessment of weight stigma. Obesity Facts, 3(1), 60–69. https://doi.org/10.1159/000273208

Schwartz, M. B., Vartanian, L. R., Nosek, B. A., & Brownell, K. D. (2006). The influence of one’s own body weight on implicit and explicit anti-fat bias. Obesity, 14(3), 440–447. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2006.58

Sharf, J., Primavera, L. H., & Diener, M. J. (2010). Dropout and therapeutic alliance: A meta-analysis of adult individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 47(4), 637–645.

https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021175

Taber, K. S. (2018). The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Research in Science Education, 48, 1273–1296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2

Tischner, I. (2019). Tomorrow is the start of the rest of their life—so who cares about health? Exploring constructions of weight-loss motivations and health using story completion. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 16(1), 54–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2018.1536385

Tudor, K. (2011). Rogers’ therapeutic conditions: A relational conceptualization. Person-Centered & Experiential Psychotherapies, 10(3), 165–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/14779757.2011.599513

Zar, J. H. (1998). Biostatistical analysis (4th ed.). Prentice Hall.

Amy Biang, PhD, LCMHC, CEDS, is an assistant professor at Northern Arizona University. Clare Merlin-Knoblich, PhD, is an associate professor at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. Stella Y. Kim, PhD, is an assistant professor at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. Correspondence may be addressed to Amy Biang, 15451 N 28th Ave, Phoenix, AZ 85053, amy.biang@nau.edu.

Feb 7, 2022 | Volume 12 - Issue 1

Eric M. Brown, Kristy L. Carlisle, Melanie Burgess, Jacob Clark, Ariel Hutcheon

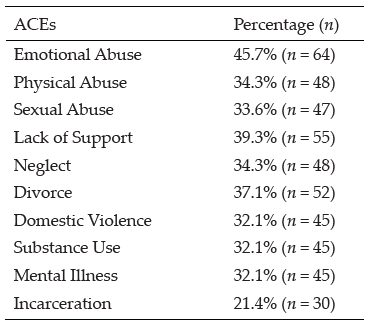

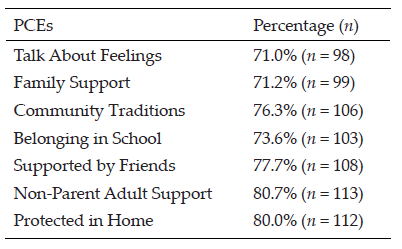

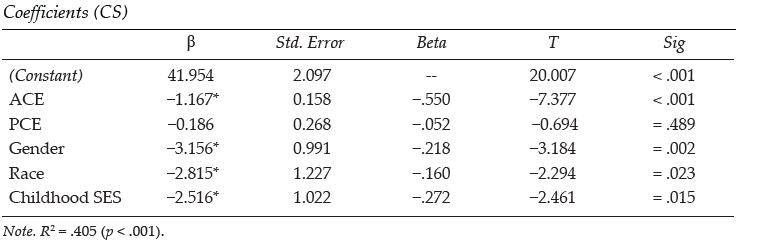

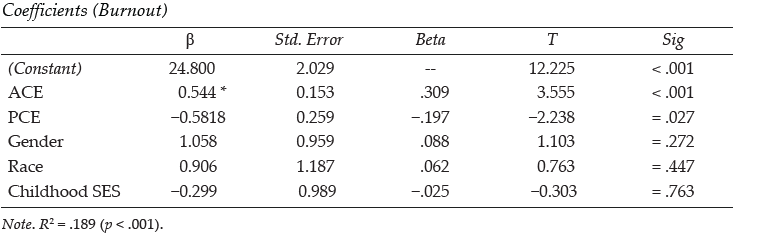

Despite an emphasis on self-care to avoid burnout and increase compassion satisfaction within the counseling profession, there is a dearth of research on the developmental experiences of counselors that may increase the likelihood of burnout. We examined the impact of mental health counselors’ (N = 140) experiences of adverse childhood experiences and positive childhood experiences on their present rates of compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress. We used a cross-sectional, non-experimental correlational design and reported descriptive statistics as well as results of multiple regression models. Results indicated significant relationships among counselors’ rates of adverse childhood experiences, positive childhood experiences, and compassion satisfaction and burnout. We include implications for the use of both the adverse and positive childhood experiences assessments in the training of counseling students and supervisees.

Keywords: counselors, burnout, childhood experiences, compassion satisfaction, secondary traumatic stress

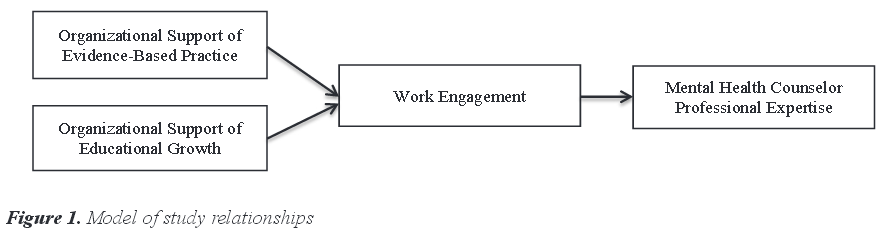

Over the past 20 years, public health research on adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and their deleterious effects on physical and mental health has proliferated and branched out to various disciplines (Campbell et al., 2016; Frampton et al., 2018). More recently, the importance of understanding the implications of ACEs for the mental health of clients has entered the counseling literature (Wheeler et al., 2021; Zyromski et al., 2020), yet the ways in which a counselor’s own experience of ACEs may affect their work have not been examined. The absence of such research is significant given the report that mental health workers have the highest rates of ACEs among those in the helping professions (Redford, 2016).

A thorough literature search of PsycINFO, ProQuest, and Google Scholar using terms including, but not limited to, adverse childhood experiences, positive childhood experiences (PCEs), compassion satisfaction (CS), burnout, secondary traumatic stress (STS), and mental health counselors (MHCs), found no peer-reviewed articles that examined the relationship between ACEs or PCEs and counselors’ rates of CS and burnout. Therefore, we chose to examine the effects of early developmental adversity, as well as early protective factors, on the professional quality of life of counselors, as measured by assessing the counselor’s levels of CS, burnout, and STS.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

In the mid-nineties, Felitti et al. (1998), with the support of the Centers for Disease Control, created the ACE Study Questionnaire to study early childhood trauma and deprivation experiences. The ACE Study Questionnaire consists of 10 questions related to whether a person before the age of 18 experienced emotional or physical abuse, substance addiction in the home, parental divorce or separation, a caretaker with mental illness, or emotional deprivation. Each question that is answered in the affirmative results in one “ACE,” with respondents’ scores ranging from 1 to 10. Studies have found that ACEs have a dose-response effect; therefore, every point increase can significantly raise the chance of experiencing negative mental and physical health effects into adulthood (Boullier & Blair, 2018; Campbell et al., 2016; Merrick et al., 2017). Additionally, individuals with four or more ACEs are significantly more likely to suffer from mental illness or substance addiction, be further traumatized as adults, and succumb to an early death (Anda et al., 2007; Metzler et al., 2017).

More recently, researchers have found that Black and Latinx individuals have significantly higher rates of ACEs compared to White individuals (R. D. Lee & Chen, 2017; Merrick et al., 2017; Strompolis et al., 2019). In a study involving 60,598 participants, R. D. Lee and Chen (2017) discovered not only that Black and Hispanic participants had higher rates of ACEs, but also that there was a correlation between ACEs and drinking alcohol heavily. In a sample of 214,517 participants across 23 states in the United States, Merrick et al. (2017) found that racially minoritized individuals, sexual minorities, the unemployed, those with less than a high school education, and those making less than $15,000 a year had significantly higher rates of ACEs than White individuals, heterosexuals, the employed, and those with higher education and income, respectively. Zyromski et al. (2020) noted that the preponderance of ACEs within marginalized communities, such as ethnic minority populations, make ACEs “a social justice issue” (p. 352).

There is scarce research related to the potential impact of ACEs on practitioners and graduate students in helping professions. Thomas (2016) evaluated the rates of ACEs with Master of Social Work (MSW) students, discovering that MSW students were 3.3 times more likely to have four or more ACEs compared to a general sample of university students. Similarly, counselors-in-training are not immune to the effects of childhood adversity; in fact, researchers noted that counselors-in-training may pursue a counseling degree because of personal trauma that drives their aspirations to help others (Conteh et al., 2017). Evans (1997) found that 93% of counselors-in-training reported at least one traumatic experience in their lives, while Conteh et al. (2017) discovered that 95% of counselors-in-training reported between one and eight traumas throughout their lifetime. Considering these results, researchers have suggested that practitioners with a history of trauma may be vulnerable to re-experiencing trauma with clients, which could negatively impact client care and increase the rate of counselor burnout (Conteh et al., 2017; Thomas, 2016). Because the rates of ACEs in practicing MHCs are unknown, it is difficult to determine how ACEs may play a role in impacting CS, burnout, and STS. Furthermore, we lack research on early developmental factors that may contribute to CS, burnout, and STS.

Positive Childhood Experiences (PCEs)