May 10, 2023 | Volume 13 - Issue 1

Shainna Ali, John J. S. Harrichand, M. Ann Shillingford, Lea Herbert

Guyana has the highest rate of suicide in the Western Hemisphere. Despite this statistic, a wide gap exists in the literature regarding the exploration of mental wellness in this population. This article shares the first phase in a phenomenological study in which we explored the lived experiences of 30 Guyanese American individuals to understand how mental health is perceived. The analysis of the data revealed that participants initially perceived mental health as negative and then transitioned to a positive perception of mental health. We discuss how these perceptions affect the lived experience of the participants and present recommendations for counselors and counselor educators assisting Guyanese Americans in cultivating mental wellness.

Keywords: Guyanese American, mental health, phenomenological, mental wellness, perceptions

In 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported Guyana as having the highest suicide rate in the world (44.2 suicides per 100,000 people; global average is 11.4 per 100,000 people). According to World Population Review (2023), within the Western Hemisphere, even after almost 10 years, Guyana remains the country with the highest rate of suicide—a concerning statistic. Responding to the WHO (2014) report, Arora and Persaud (2020) engaged in research to better understand the barriers Guyanese youth experience in relation to mental health help-seeking and suicide. Their research included 17 adult stakeholders (i.e., teachers, administrative staff, community workers) via focus groups, and 40 high school students who engaged in interviews. Arora and Persaud used a grounded theory approach and found the following themes as barriers to mental health help-seeking in Guyanese youth: shame and stigma about mental illness, fear of negative parental response to mental health help-seeking, and limited awareness and negative beliefs about mental health service. They recommended integrating culturally informed suicide prevention programs in schools and communities. In efforts to extend Arora and Persaud’s findings, we sought to further understand how Guyanese Americans define and experience mental health to better serve them in counseling.

Startled by the statistics presented by the WHO (2014) and Arora and Persaud (2020), we were compelled to focus our attention on this unique immigrant subgroup in the United States. It is important to note that between the WHO’s 2014 report and Aurora and Persaud’s research, no other studies related to Guyanese American suicidality are recorded in the literature. However, two studies on Guyanese American mental health emerged by Hosler and Kammer (2018) and Hosler et al. (2019). Our decision to conduct research on the Guyanese American community was further informed by Forte and colleagues’ (2018) review of immigrant literature in the United States, which stated that “immigrants and ethnic minorities may be at a higher risk for suicidal behavior as compared to the general population” (p. 1). Forte et al. found that immigrants, when compared with individuals in their homeland, were at an increased risk of experiencing mental health challenges like depression and other psychotic disorders. Currently, suicide is listed as the 10th leading cause of death overall in the United States (Heron, 2021). More specifically, within ages 10–34 and 35–44, suicide is the second and fourth leading cause of death, respectively. Heron’s (2021) report, referencing the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), highlighted that in the United States, death by suicide (47,511) is 2.5 times higher than homicides (19,141). The prevalence of suicide among Guyanese people within and without the United States warranted further exploration of the experiences of this marginalized group.

The Guyanese American Experience

Comparing all countries with a population of at least 750,000 people, Guyana, a Caribbean nation, is said to have “the biggest share of its native-born population—36.4%—living abroad” due to remoteness and limited opportunities within the country to move from a lower to a higher socioeconomic status (Buchholz, 2022, para. 2). It is estimated that the United States is home to approximately 232,000 Guyanese Americans whose ancestry can be traced back to Guyana (United States Census Bureau, 2019), a country in the northeast of South America, bordered by Brazil, Venezuela, and Suriname. Although approximately 50% of all Guyanese immigrants in the United States reside in New York City alone (Indo-Caribbean Alliance, Inc., 2014), Guyanese people can be found across all 50 states and the District of Columbia (Statimetric, 2022). This draw to the United States, an English-speaking nation, might be linked to the fact that Guyana is the only country in South America that recognizes English as its official language (One World Nations Online, n.d.).

Like most immigrants, Guyanese immigrants travel to the United States seeking a better life and opportunities for themselves and their families. However, the process of transplanting can be bittersweet, in that Guyanese immigrants might be forced to relinquish their identity and customs and embrace American customs through assimilation (Arvelo, 2018; Cavalcanti & Schleef, 2001). For many Guyanese immigrants, being caught between leaving their homeland and beginning life in their adoptive home can lead to a cultural clash, resulting in problematic coping mechanisms (e.g., minimizing/hiding mental health challenges, cultural shedding [adopting American identity and losing cultural heritage]; Arvelo, 2018).

As discussed above, suicide in the Guyanese community is unquestionably a serious concern, but the community faces other challenges in the United States as well. For example, Hosler et al. (2019) found a statistically significant association between discrimination experience and major depressive symptoms in a sample of Guyanese Americans. However, Hosler et al. (2019) also found mean scores on the Everyday Discrimination Scale (EDS; Williams et al., 1997) were lower (i.e., less discriminatory experiences in everyday life) for Guyanese Americans when compared to other groups (Black, White, and Hispanic) because Guyanese Americans have a more cohesive interpersonal network. It would appear that Guyanese Americans experience lower everyday discrimination because they operate within interpersonal spaces that are more cohesive, yet their discriminatory experiences are positively associated with depression symptoms, which is a source of concern.

Another area of concern among Guyanese Americans is intimate partner violence (IPV), yet research remains lacking (Baboolal, 2016), leading us to draw directly from Guyanese literature. In Guyana, IPV is one of the most prevalent forms of violence (Parekh et al., 2012). As a country, although Guyana endorses the commitment to gender equality, women are the majority only in the tertiary sector (e.g., education, human services, clerical services, and tourism). Nicolas et al. (2021) stated that “domestic duties, marriage, and child-bearing, particularly for women between the ages of 25–29, have hindered their labor force participation” (p. 147). They documented that 1 in 6 Guyanese women, mostly from rural parts of the country, hold the belief that beating one’s wife is necessary (i.e., husbands are justified in beating their wives, resulting in domestic violence being a relevant mental health issue). In fact, suicide is identified as a public health issue for Guyanese women, who use it as a means of coping “with economic despair, poverty, and hopelessness . . . [and] to escape family turmoil, relationship issues, and domestic violence” (Nicolas et al., 2021, p. 148). However, even with access to mental health services increasing in Guyana, seeking out mental health care is uncommon due to stigma, lack of communication, inadequate financial resources, limited providers, and other barriers related to access (Nicolas et al., 2021). Within the U.S. literature, there remains a dearth of information on the experiences of this group as it relates to suicide and IPV. Most likely, this is a result of racial categorization within the United States, where, based on phenotype and racial composite, individuals are often lumped into one category, such as Black. As important as Guyanese literature on IPV is to inform the work of counselors, we believe it is equally important for us to engage in research regarding IPV and other mental health challenges on Guyanese Americans specifically. Learning about Guyanese Americans’ perceptions of mental health may facilitate closing the gap in the utilization of mental health services, warranting the current investigation.

Recognizing the noticeable research gap related to the mental health experiences of Guyanese Americans, we conducted a thorough review of the literature related to mental health and well-being. Through databases such as PsycINFO, ProQuest Central, Web of Science, MEDLINE, and SocINDEX, using the search terms “Guyanese Americans, Health and Wellbeing, Mental Health of Guyanese Americans, Access to Mental Health,” 54 search results were found. However, only two applicable studies were found to address Guyanese Americans’ mental health specifically (Hosler & Kammer, 2018; Hosler et al., 2019). The other search results were either not research manuscripts (i.e., reflections and newspaper articles) or addressed other constructs specific to the Guyanese people (e.g., family, education). The first study by Hosler and Kammer (2018) focused specifically on the health profiles of Guyanese immigrants in Schenectady, New York. This study was conducted with 1,861 residents between the ages of 18–64 years. Guyanese Americans from Schenectady were mostly from a low socioeconomic status, which resulted in them being less likely to have health insurance coverage, an identified place to receive care, and access to cancer screenings. They were also identified as being more likely to engage in alcohol binge drinking—all conditions of significant concern to us, resulting in the present study. In fact, Hosler and Kammer reported that Guyanese Americans are among the lowest group of those insured in the United States when compared with other minority groups such as Black and Latinx groups. Some researchers believe ethnocentric stereotyping, cultural incompetence by professionals, a lack of steady employment, and poor previous interactions with the health care system are barriers Guyanese immigrants experience when accessing medical and mental health services (Arvelo, 2018; Cheng & Robinson, 2013; Jackson et al., 2007).

The second study of Guyanese immigrants was conducted by Hosler et al. (2019) and explored everyday discrimination experiences and depressive symptoms in relation to urban Black, Hispanic, and White adults. This study included 180 Guyanese Americans (i.e., both citizens by birth and naturalized citizens/immigrants), all 18 years and older, from Schenectady, New York. The researchers found a significant independent association between the EDS score and major depressive symptoms for Guyanese Americans, suggesting that discrimination experiences might be an important social cause for depression within this community. Based on the reported challenges faced by Guyanese Americans, as well as our desire to contribute meaningfully to the extant body of literature on the Guyanese American community, we conducted a phenomenological inquiry. More specifically, we sought to better understand the lived experiences of Guyanese Americans pertaining to mental health (i.e., definitions, beliefs, practices), and how they access and incorporate mental health resources to mitigate the known mental health risks of this population in the United States, in the hopes of creating tailored methods for culturally responsive care.

Method

Because limited mental health research exists on this unique community, the present study, which is part of a larger research endeavor, sought to explore Guyanese Americans’ lived experiences with mental health. To lay the foundation of understanding, the present study focused on Guyanese Americans’ perceptions of mental health. Phenomenology, a constructivist approach, recognizes the existence of multiple realities and provides an understanding of participants’ lived experiences using their own voices (Haskins et al., 2022). We selected transcendental phenomenology (Moustakas, 1994) as the appropriate methodology for answering our research questions, as it is congruent with the counseling profession’s similar objective of understanding the human being. Akin to the practice of counseling, transcendental phenomenology emphasizes methods of the researcher to best set aside the potential clouds caused by bias in an effort to allow the explored phenomenon to surface. Transcendental phenomenology aligns with one of the core professional values in the American Counseling Association’s Code of Ethics (ACA, 2014), that of supporting “the worth, dignity, potential, and uniqueness of people within their social and cultural contexts” (p. 3). It also aligns with Ratts et al.’s (2015) Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies (MSJCC), specifically understanding the client’s worldview domain. Our focus on Guyanese Americans, an understudied minority group in the United States (Hosler & Kammer, 2018) originating from a country that has been identified as having the world’s highest suicide rate (WHO, 2014), led us to select this method so that we could maintain cognizance of our surroundings, hold respect for the population, and examine participants’ experiences (Haskins et al., 2022; Hays & Singh, 2012; Hays & Wood, 2011).

Participants

Before participants were recruited for the study, IRB approval was obtained from the university with whom Shainna Ali, M. Ann Shillingford, and Lea Herbert are affiliated. Purposive criterion sampling was used to recruit participants, leading to a sample of adults who self-identified as Guyanese American (i.e., either immigrated to the United States themselves or had at least one parent who was born in Guyana). Recruitment materials were shared with Guyanese Americans using counseling listservs (i.e., ACA–AMCD Connect and CESNET) and social media platforms (i.e., LinkedIn, Facebook, and Instagram). Members of the research team contacted all participants using email to share details regarding the study and the informed consent document, collect demographic data, and schedule individual interviews. According to qualitative research, sample size recommendations range from six to 12 participants (Creswell, 2013; Guest et al., 2006; Onwuegbuzie & Leech, 2007). Hence, we sought to recruit 15–20 participants to account for the possibility of attrition.

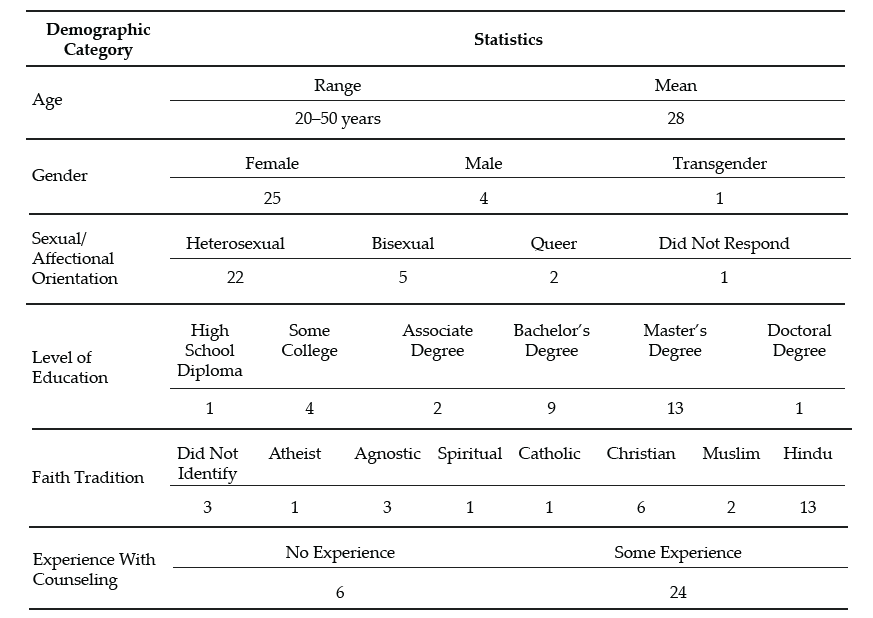

Our recruitment efforts yielded 73 individuals who expressed interest in the study, 60 of whom met all inclusion criteria and were initially contacted. Forty-three individuals were unable to complete an individual interview due to scheduling conflicts; hence, we secured a total of 30 participants who completed the study. Of this number, 17 participated in individual interviews and a total of 23 individuals participated in a one-time focus group to further clarify data from the individual interviews. It should be noted that 10 of the 23 focus group participants also participated in the individual interview. Further recruitment was deemed unnecessary, as the data analysis reached saturation with data from the individual interviews and focus group. We present demographic data on all participants who engaged in the study, both individual interviews and the focus group (N = 30), in Table 1.

Table 1

Participant Demographic Data

Note. This table provides a breakdown of the demographic characteristics of Guyanese American participants (N = 30).

Data Collection and Analysis

Participants engaged in a semi-structured interview lasting 30–60 minutes, conducted by Ali and Shillingford. Interviews were conducted via Zoom, audio-recorded, and transcribed verbatim. The interview protocol consisted of three primary questions, and sub-questions were used to clarify responses: 1) How do you define mental health?; 2) Who in your life has had experiences with mental health?; and 3) What experiences have you had with mental health? Prior to conducting our study, we included in our IRB documentation that data collection of individual interviews would follow saturation guidelines and that a focus group could be used for further data illumination. Following initial data analysis, we found it necessary to conduct a 1-hour follow-up focus group via Zoom to probe deeper into the data and to allow participants to clarify concepts related to emerging themes. Upon the first round of analysis, it was noted that several participants experienced a shift in perceptions regarding mental health. Focus group probes explored whether participants noticed this shift, what may have contributed to this shift, and when the shift occurred.

After all focus group and individual interviews were transcribed, we used guidelines outlined by Moustakas (1994) to analyze the data. First, we immersed ourselves in the data, reviewing each transcript individually. The transcripts were then divided equally among the four researchers, who read through each to become familiar with the data. With each transcript, we identified relevant statements reflecting participants’ lived experiences (horizontalization) as Guyanese Americans within the contexts of mental health beliefs and experiences.

Following this process, we met multiple times to review all transcripts and confer about the textural descriptions. We identified relevant codes, then synthesized the textural descriptions into themes based on commonalities, distilling the meaning expressed by participants. Then we engaged in reduction and elimination via consensus coding. This process included reading and rereading transcripts together, which followed an iterative process of reviewing the text and code, coding, rereading, and recoding, before determining which thematic content was a new horizon or new dimension of the phenomenon.

After all transcripts were analyzed following this reduction process, clustering and thematizing occurred (i.e., thematic content was clustered into core themes based on participant experiences; Hays & Singh, 2012; Moustakas, 1994). We extracted verbatim examples from the transcripts to generate a thematic and visual description of the phenomenon being examined. After completing the initial data analysis, we conducted member checking by sending each participant their individual transcript as well as the written results section. Participants were requested to provide feedback on the accuracy of their transcripts. Additionally, following the focus group and elucidation of themes all participants were offered an opportunity to member check and clarify the degree to which the results aligned with their lived experiences. The participants did not report any errors; however, clarification was offered by one participant.

Trustworthiness and Positionality

Trustworthiness is a key element of qualitative research in which the research findings accurately reflect the data (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). A critical element of maintaining research credibility is through reflexivity, wherein researchers critically examine procedures employed in relation to power, privilege, and oppression (Hunting, 2014). To safeguard against researcher bias, we worked collaboratively to establish and maintain credibility throughout data collection and analysis processes. Our research team consisted of one Indo-Guyanese American female faculty member, one Afro-Guyanese American female doctoral student, one Black female faculty member, and one Indo-Chinese-Guyanese Canadian male faculty member. All three faculty members belong to CACREP-accredited counselor education programs, and all four researchers have clinical experience working with diverse populations.

To address researcher bias, we engaged in bracketing to minimize the ways in which our experiences influence our approach to research and expectations of the outcomes of the study. Prior to data collection, we discussed our experiences in relation to Guyana, mental health in the Guyanese American community, and our roles as mental health leaders and advocates. We identified our personal experiences, acknowledged our biases, and attempted to bracket while conducting the interviews and focus group. Throughout the data collection and analysis processes, we participated in personal reflection and kept analytic memos documenting our reactions and initial thoughts about the data collected.

Before analyzing the data, we met to confirm analysis procedures, ensuring consistency. We initially analyzed data individually, then determined codes and themes as a team to reduce bias. Throughout the data analysis process, we consulted with each other, addressing questions or concerns related to the data. We also consulted with an outside researcher experienced in qualitative research to obtain critical feedback on the data analysis process and the research findings (Marshall & Rossman, 2006). Our consultant served as an external check of the research methodology and theoretical interpretation of the data.

Findings

The results of the analysis increase understanding of the lived mental health experiences of Guyanese Americans by elucidating perceptions of mental health (Creswell, 2013). All participants shared their beliefs about mental health and the direct and indirect experiences that informed their conceptualization. Three themes surfaced. The first two showed a clear divide in the data: 1) mental health being perceived as negative, stigmatized, elusive, and intimidating; and 2) mental health being perceived as positive, important, helpful, and empowering. It is important to note that these primary themes were not representative of two subsets of participants, and this extracted another theme, which centered on the tendency of participants’ beliefs to transition from negative to positive views of mental health.

The Perception of Mental Health as Negative

When exploring obstacles, subthemes emerged in which hindrances to mental health were acknowledged to exist across three levels: individual, familial, and sociocultural. In parallel, these three subthemes were echoed in the exploration of factors that participants acknowledged have contributed to their mental wellness. The following section explores the primary themes in detail by highlighting the participants’ voices in describing their lived experiences.

Mental Health Concerns Are a Sign of Weakness

All participants in the individual interviews shared that they originally believed that mental health developed out of weakness. This belief was often attributed to minimizing remarks from family members. Oftentimes these comments were paired with other suggestions of how to ameliorate symptoms such as praying more, working harder, or contributing to physical health (e.g., drinking tea). Sharon shared:

It was just like, oh no, you just need to read a book or you just need to go and do something and take your mind off of however it is you’re feeling, like there’s no reason for you to be sad, you have a roof over your head and you’re going to school and you’re doing all of these things, it doesn’t matter. There’s no reason for you to be sad or feel any type of way about anything because we provide everything for you.

Several participants noted that investment in physical wellness was preferable to mental wellness, although physical health was not genuinely prioritized. Participants shared personal and observed maladaptive coping with poor eating habits (i.e., quality and quantity) and excessive substance abuse, namely alcohol. Some participants shared that these tactics were used to manage mental health symptoms or avoidance. Christine shared, “When you’re struggling with things . . . you have nowhere to go to with them except alcohol and the bottom of a rum bottle.” Many participants recognized that coping with alcohol is normalized within the culture. Further, the commonality of these methods normalized consumption and have caused additional issues (e.g., diabetes, heart disease, alcoholism). Arjun noted:

We all have relatives that are kind of stuck on the whole drinking issue. We know a lot of them. They get together with their friends and they “lime,” as we like to call it. They drink in groups and they “gyaff,” they have fun. But it’s a completely different story when they’re by themselves and they’re drinking.

Mental Health Is Taboo

A general consensus was that all participants in the study once believed that mental health was not important and that mental health problems were shameful and not to be discussed. This consistent trend was one of the reasons that we opted to further understand responses through a focus group. Therefore, a direct probe was offered to the focus group participants to explore if they believed discussing mental health was taboo. When delving deeper into these perceptions, participants noted that these thoughts were informed by the beliefs of others and upheld in the wider cultural paradigm. All participants reported that, generally, mental health should not be talked about in order to save face and be respectful. Because mental health issues were seen to be synonymous with weakness, sharing about mental health was equated with the risk of bringing shame to oneself or to one’s family. For example, Chandra shared that “Guyanese people don’t want a kid that’s broken or a little off.” Hence, if someone opts to discuss their mental illness, it is to be done carefully, or secretly.

Most participants shared that typically, when divulging their symptoms, they went to an elder, often a parent, grandparent, or elder sibling, in an effort to keep concerns within the family system. However, many participants noted being minimized or dismissed when sharing their concerns with family members. Ramona explained her feeling that her family

is really strong about, like, don’t be selfish. And I wonder if they would categorize it under that. Like if you’re taking up too much space or time or whatever, you’re trying to center the attention on you or whatever, so that’s a self-serving thing.

A generational rule of discourse emerged from the data. Though the tendency was to keep mental health discussions within the family system, it was also atypical for a younger member to address observed issues with an elder. Several participants noted that this hidden guideline kept informed younger generations from being able to utilize their recognition of warning signs to help the given person and the family system. Arjun shared that as he’s gotten older and has learned more about mental health, he has acquired the courage to address the problems he sees with elders, including his uncle:

I said, “Uncle, what’s wrong?” And he said, “No, nothing is wrong.” But he was crying, you could see tears were streaked on his face, but he wouldn’t talk about it—he wouldn’t say anything. It’s not only one time I saw him, it’s multiple times that I’ve seen him when he has been drinking by himself, that he kind of has the same face all the time. Prior to the times that I asked him, I kind of looked at him and I kind of walked away the first couple of times. Because I was kind of like, this is not something that looked like I should butt in, as a child especially. When you’re younger, your parents tell you, “Mind your business.” Or they say, “You’re not an adult, go with the kids.” So . . . the first couple of times I saw him, I kind of avoided it.

Others Are Not To Be Trusted

Some participants noted that beyond the purpose of family protection, caution to mental health discourse was also due to lack of trust of others. Christine explained: “We had a counseling center on campus, but I was like, ‘Oh, I can’t go talk to anybody,’ because that’s what I was raised with. You don’t talk to strangers about your problems. I had to keep everything inside.” Nevertheless, some families encouraged talking to a religious leader to assist the individual in enhancing devotion and reducing mental health symptoms. Still, regarding professional mental health services, many participants believed, at least at one time, that such services are not helpful, providers are not to be trusted, assistance of that nature is for other (e.g., White) people, and succumbing to that level of desperation is a sign of weakness. When sharing about mistrust in professional mental health assistance, misconceptions and stereotypes surfaced. Ramesh shared:

Oh boy. I have to be honest with you, I feel counseling is, I’ll speak to a shrink and they’ll prescribe drugs to me, like Ritalin or . . . I was like, you know what, I’m better than that. I’m probably totally wrong about it, but that’s just the perception that I have. I’ll be laying on the couch and I’m going to speak into someone and then they’re going to prescribe drugs to me. I don’t want that. I can try to figure this out on myself by talking and trying to do things—positive behavior.

Mental Health Perceived as Positive

All participants in the individual interviews acknowledged a shift in their perceptions of mental health. Their newfound conceptualization included a holistic view of wellness in which mental wellness was seen as an important component to overall well-being and quality of life. In this newer perception, participants acknowledged the ability to consider more variables influencing mental health than they recognized in the past. For example, many participants noted a link between mind and body, versus the previously held notion that physical health is more important than mental health. A few participants noted that mental health can be influenced by genetics, while some noted that it could be influenced by personality, and others noted that it can be influenced by people and the surrounding environment.

All participants, from both the individual interviews and focus group, concurred that everyone feels mental health effects; furthermore, showing signs of a problem is not attributed to weakness. Moreover, because mental health affects everyone, a widespread belief emerged that we all have the responsibility to foster our mental wellness. Additionally, participants shared several examples of what naturally ensued without investing in strategies for mental health such as challenges with emotional regulation, coping, relationships, and worsening mental health problems.

The Transition Between Negative and Positive Perceptions

The transition between old and new conceptualizations of mental health was informed by direct and indirect experiences. All participants shared a transition in beliefs in the individual interviews, and this was explored in the focus group for further clarification. Most participants shared that their personal mental health history informed a change in their beliefs. Many of these participants noted the influence of their healing process, most notably seeking professional help. All participants, from both the individual interviews and the focus group, shared at least one example of learning about mental health by observing another person’s experience. For example, Jessie shared, “Unfortunately, I came from a home of domestic violence . . . I was around maybe six, my dad was bipolar . . . [and] he was just a wife beater. That is probably when I can recall [learning] of mental health.” Another example of learning about mental health from others is captured in Reginald’s comment:

[As] an only child . . . my parents took it upon themselves to [teach me]. . . . It wasn’t like, “Okay, sit down. Let me tell you why these things are.” It was just we’ll be talking about somebody else or going over something that happened and then they’ll explain why, but never directly for me. It was always about other people’s kids.

Many of these individuals emphasized the belief that by paying attention to others, you can learn what is helpful and unhelpful for mental health. Oftentimes this was in their own family; however, extended family and community members were also highlighted. Moreover, a few participants shared their recognition that living with someone who is struggling with their mental health may negatively impact personal wellness (e.g., be triggering). Beyond the family system, some participants noted that exposure to other cultures and perceptions of mental health informed a conceptualization of mental wellness. Seeta shared:

I had friends of other religions or like no religions. And then we would talk about a lot of different things. Like I would ask them questions like, “Oh, so how do things work in your house? Do your parents talk about your God or whatever?” And they’re like, “No.” And I’m like, “So where do your emotions come from?” And they’re like, “Well, you know, we just feel them. Some days I feel angry and some days I feel sad, some days I feel happy.” And I’m just like, “Okay, this is interesting.”

From the quote, it might appear that one’s emotions are in some way connected with God or another higher power; however, this is not something that was observed with other participants of our study. It was more common for participants to share stories of their families using religion as the solution to mental health concerns. For example, Yolanda shared:

My grandmother came when I turned 16 and she kept trying to tell my mom I was showing signs of depression. And my mom was like, “No, she’s like that all the time, like, that’s just how she is.” And my grandma was like, “That’s not normal. You should get her checked out.” And my mom kept saying, “No” and kept denying it. And then my grandma said, “You have to do something.” And then my mom replied, “Oh, I’m going to pray for her.”

In addition to personal experiences and observations of others, participants noted that improved mental health awareness and education prompted them to think critically about their mental health schemas. Ramesh shared:

My education, I always feel like this is what saved me in the end, because I was able to be around other people to know better and to come back home and be like, “Excuse me, this is not how we do things. This is not how we say things. I don’t know what it was like in Guyana.”

Some participants associated this with growing older, and others noted their personal initiative to improve mental health knowledge by following mental health pages on social media, taking a related class, and for some, becoming a part of the mental health field themselves. From this vantage point, many participants were able to equate their previously held notions with beliefs embedded in the culture such as generational rules of respect, gender differences, and the impact of colonialism. Participants, despite their gender differences, noted that within the cultural framework, the rule that mental health should not be discussed is disproportionately applicable to males. Participants shared that this is often due to the perception that it is important for men to be strong, and again, mental illness is a symptom of weakness. This was also linked to the breadwinner role and the pressure to provide for the family. However, this was only noted to have detrimental effects, as anger issues, IPV, and alcoholism were noted to arise out of this rule. Some participants noted that the survival aspect of colonialism may have contributed to the lack of privilege to focus on mental health. In addition, the history of colonialism in Guyana (i.e. slavery, indentured labor) could have informed the lack of trust in professional services.

The change in mental health conceptualization was noted to have benefits beyond the participants themselves. Some participants remarked that the shift in perception was recognized in the wider generation. Ramona reflected:

I will say that a lot of folks from my generation have been a lot more like, “Go to therapy. We should be taking care of our thoughts and our feelings or emotions.” That’s important to you in the same way that if you tore a ligament that you would need to get surgery or do whatever.

Within the newfound conceptualization of mental wellness emerged a vow of social responsibility. All participants, from both the individual interviews and the focus group, shared their intention to help others, and some even noted it as their duty. Ways to help others included advocating for mental health awareness, access, and education; helping to challenge unhelpful cultural beliefs; breaking generational cycles; and protecting others from experiencing similar struggles (e.g., child, sibling).

Discussion

The findings from this study are enlightening, and some are the first to be documented through research, even if they were observed in practice. Initial perceptions of all participants, from both the individual interviews and the focus group, were that mental health is a taboo topic and seeking mental health services is bad. These perceptions stemmed from fear, mistrust, and limited awareness of the benefits of mental health services. This is consistent with findings from Arora and Persaud (2020), who surmised that Guyanese individuals hold negative views of mental health that significantly impact their help-seeking. Furthermore, the findings point to strong familial and sociocultural influences, such as beliefs about mental health, that swayed individual perceptions of mental health, which is in keeping with recent literature on affirming cultural strengths and incorporating familial identity in working with clients of Guyanese descent (Groh et al., 2018; Nicolas et al., 2021).

Discussing issues related to mental health was viewed as a sign of weakness, which translated to help-seeking being a taboo. It would appear that the stigma associated with mental health remains a common experience for Guyanese Americans, and when coupled with limited communication, insufficient funding, and lack of providers, we can see how Nicolas et al. (2021) found this to be concerning. Cultural clash, ethnocentric stereotyping, and cultural incompetency may also be responsible for Guyanese Americans being distrustful of the health care system, leading them to engage in maladaptive behaviors (i.e., avoidance, use of substances, IPV) and not receive the mental health attention and care they need (Arvelo, 2018; Cheng & Robinson, 2013; Jackson et al., 2007).

It appears that even in the face of discrimination and experiences of mental health challenges like alcoholism, depression (Hosler & Kammer, 2018), and IPV (Parekh et al., 2012), leaning on the support of the community serves to buffer against mental health challenges for Guyanese Americans. It also seems that changing mental health perceptions from negative to positive was significantly related to mental health literacy and exposure to other systems such as school, work, and community (i.e., cross-cultural exchange).

Findings that were not previously documented in the literature suggest that an integrated view of wellness enabled participants to augment their negative abstractions of mental health care. These findings serve as an indication that among Guyanese Americans, although mental health has been perceived as negative, weak, and a taboo, the narrative is beginning to shift to make space for mental health awareness, education, access, and functioning, thereby creating unique implications for counselors seeking to meet the needs of this immigrant subgroup.

Implications

In combination with prior literature, the results of this study provide a rationale for mental health counselors, marriage and family counselors, school counselors, and counselor educators to inspire dialogue to foster mental wellness. Based on the findings from this study, when working with Guyanese Americans, counselors should focus on three key strategies to support Guyanese American clients: (a) mental health awareness, (b) mental health education, and (c) mental health experience.

Mental Health Awareness

Participants in this study initially held limited views and awareness of the signs and symptoms of mental health. When awareness was heightened through various means, they were more open to exploring the benefits of services. Counselors can be instrumental in creating awareness by first raising their own awareness pertaining to cultural stigma and its influence on Guyanese Americans’ mental health. For example, unwillingness to attend counseling sessions may be linked to the culturally held perception that discussing mental health, especially beyond the core family system, is taboo. In acknowledging this, counselors can raise awareness of confidentiality, which can be seen as an alignment with the cultural notion that talking about mental health is taboo when it means talking to anyone, and the role of the counselor can be highlighted as a professional collaboration versus communal gossip. Counselors need to be mindful of the collectivistic nature of Guyanese American culture, which causes personal and familial illnesses alike to be perceived as personal problems. Rather than dismiss a client’s concerns about mental health, a counselor can benefit from exploring how the family members’ symptoms, perceptions about mental health, and willingness to adhere to treatment influence the client’s symptoms, perceptions, and commitment to counseling. Further, collectivism spans beyond the protective family system. On one hand, this community orientation can be used to explore a broad range of support, yet on the other hand, depending on the client’s experience, this may also be a widened range of societal pressure (e.g., judgment, criticism, shame).

Mental Health Education

Increased understanding of mental health appeared to have led participants to seek services and resources to increase their mental health literacy, with the hope of improving their well-being. Counselors and counselor educators can be instrumental in offering Guyanese Americans mental health education. To begin, all mental health professionals should demonstrate a posture of cultural humility when engaged in psychoeducation on mental health and wellness for this population. In order to raise awareness through education, mental health professionals are encouraged to model trust, respect, sensitivity, compassion, and a nonjudgmental stance. Within session, counselors should be prepared to offer information regarding early signs of mental illness, compounding factors (e.g., alcohol, suicidal ideation, domestic violence), obstacles (e.g., stigma), and resources. Additionally, counselors may need to offer psychoeducation on the family system, roles, dynamics, beliefs, experiences, and generational patterns that can influence individual mental health. In the event that a family member with mental health problems is unwilling to seek assistance, helping the client to better understand the diagnosis and cope personally can be empowering. Finally, to employ the collectivistic nature of Guyanese American culture, stigma can be confronted, and mental health education can be effectively offered by providing group counseling within this population. Group counseling can offer a variety of therapeutic factors that can benefit Guyanese Americans such as universality, hope, and corrective recapitulation of the primary family group (Yalom & Leszcz, 2005).

Beyond the counseling office, counselors and counselor educators should consider collaborating with culturally supportive organizations. Workshops and information sessions can be tailored to explore and address cultural, religious, ethnic, and generational differences in addition to offering mental health resources (e.g., signs, symptoms, treatment). Several of the participants in our study shared that access to psychology courses in school helped to improve their knowledge about mental health. In addition to these classes continuing to be offered, accessibility to such courses should be expanded. Schools and universities may benefit from offering workshops and other informational sessions to support mental health. Beyond information being offered, a follow-up may be beneficial by linking school or campus counselors in order to connect an improvement in awareness and education to action, change, and health.

Several participants shared that because of a lack of access to mental health education, their knowledge was attained through social media platforms such as Instagram and TikTok. Although the quality of mental health education was not assessed in the present study, the lack of regulation on social platforms could perpetuate misleading, confusing, and stigmatizing misinformation surrounding mental health. Counselor educators should consider their roles beyond the classroom. In addition to empowering counselor trainees to utilize the suggestions above to foster awareness and education, counselor educators can offer responsive and succinct information via social media. Whereas social media is not an appropriate platform for tailored education or services, brief information can be offered to bridge the gap between awareness, education, and access.

Mental Health Experience

Growth in awareness and knowledge around mental health resulted in participants intentionally engaging in positive experiences as a way of resisting past harmful and hurtful practices and generational patterns, reauthoring a new narrative of hope and healing. Being wellness-focused, counselors are uniquely positioned to support this community by facilitating positive experiences impacting overall mental health and well-being.

Counselors can honor clients from this community by creating safe spaces for them to share their narratives without judgment. Counselors can foster healing communities through group counseling, where clients collaboratively share each other’s mental burdens and celebrate successes (Yalom & Leszcz, 2005). Counselors can honor collectivism by encouraging clients to participate in support groups in addition to personal counseling. Counselors and counselor educators can enhance the approachability of counselors by improving their visibility in the community. Examples include a community counselor being involved in outreach with a local cultural center, a school counselor offering mentorship with student clubs, a college counselor guest-speaking at a Guyanese American student organization meeting, or a counselor educator offering tailored workshops for the community.

In addition to the aforementioned implications, we believe that in order for counselors to bridge generational gaps in counselor distrust, counselors must acknowledge the lack of representation of diversity within the profession of counseling, the predominance of Western and European cultural and psychologist-centered curriculum, and lapses in poor bioethics and power dynamics among counselors and marginalized communities (Singh et al., 2020). Next, the specific intersectional impacts suggest counselors must adapt a multicultural orientation and illuminate cultural sensitivity. When a clinician enacts cultural sensitivity in session, clients can examine their perceptions of illness and center their multiple identities (Davis et al., 2018).

Limitations and Future Research

Several limitations that arose from the research process are important to mention. All interviews were conducted virtually. Although secured virtual platforms such as Zoom are considered acceptable for research, lack of face-to-face interviewing may have excluded subtle visual cues and induced video-conferencing fatigue (Spataro, 2020). Though researchers made great attempts to increase participant comfort and review the informed consent before the interview process, it is also plausible that respondents may have censored their responses out of concern for potential breach in confidentiality. A majority of respondents are college-educated, female, first generation, and of Indo-Guyanese descent; hence, the results may not be representative of all Guyanese Americans. Additionally, aligned with phenomenological methods of exploring lived experiences, research prompts were general. Recognizing the concerning statistics surrounding suicide (WHO, 2014), a future study exploring suicidality could be beneficial. Future research might seek to explore a more diverse pool of participants, including diversity in gender, age, ethnicity, and number of years in the United States. To build on the findings from the present study, future studies should explore what factors contribute to Guyanese American mental health as well as what variables may hinder mental wellness. It may also be beneficial to include research from the perspective of children and parents to further understand the influence of family systems and cross-generational norms.

Conclusion

This study highlighted the crucial need to address the mental health literacy of Guyanese Americans. The findings illuminate Guyanese Americans’ perceptions of mental health, including the transition from negative to positive perceptions and its potential influences. Efforts should be made to promote awareness, education, and experience related to mental health awareness for Guyanese Americans. Supporting mental health may help to reduce alarming rates of mental illness in Guyanese Americans and may also have the potential to influence related groups such as Guyanese, American, and Caribbean individuals. Counselors and counselor educators have the potential to play a significant role in supporting these clients by being cognizant and informed about cultural considerations.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

American Counseling Association. (2014). ACA code of ethics. https://www.counseling.org/resources/aca-code-of-ethics.pdf

Arora, P. G., & Persaud, S. (2020). Suicide among Guyanese youth: Barriers to mental health help-seeking and recommendations for suicide prevention. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 8(1), 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2019.1578313

Arvelo, S. D. (2018). Biculturalism: The lived experience of first- and second-generation Guyanese immigrants in the United States (Order No. 10749930) [Doctoral dissertation, Chicago School of Professional Psychology]. ProQuest One Academic. (2027471070).

Baboolal, A. A. (2016). Indo-Caribbean immigrant perspectives on intimate partner violence. International Journal of Criminal Justice Sciences, 11(2), 159–176. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336926774_Indo-Caribbean_Immigrant_Perspectives_on_Intimate_Partner_Violence

Buchholz, K. (2022, November 11). The world’s biggest diasporas [Infographic]. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/katharinabuchholz/2022/11/11/the-worlds-biggest-diasporas-infographic/?sh=4185fd634bde

Cavalcanti, H. B., & Schleef, D. (2001). Cultural loss and the American dream: The immigrant experience in Barry Levinson’s Avalon. Journal of American and Comparative Cultures, 24(3–4), 11–22.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1537-4726.2001.2403_11.x

Cheng, T. C., & Robinson, M. A. (2013). Factors leading African Americans and Black Caribbeans to use social work services for treating mental and substance use disorders. Health & Social Work, 38(2), 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/hlt005

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Davis, D. E., DeBlaere, C., Owen, J., Hook, J. N., Rivera, D. P., Choe, E., Van Tongeren, D. R., Worthington, E. L., Jr., & Placeres, V. (2018). The multicultural orientation framework: A narrative review. Psychotherapy, 55(1), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000160

Forte, A., Trobia, F., Gualtieri, F., Lamis, D. A., Cardamone, G., Giallonardo, V., Fiorillo, A., Girardi, P., & Pompili, M. (2018). Suicide risk among immigrants and ethnic minorities: A literature overview. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(7), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15071438

Groh, C. J., Anthony, M., & Gash, J. (2018). The aftermath of suicide: A qualitative study with Guyanese families. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 32(3), 469–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2018.01.007

Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903

Haskins, N. H., Parker, J., Hughes, K. L., & Walker, U. (2022). Phenomenological research. In S. V. Flynn (Ed.), Research design for the behavioral sciences: An applied approach (pp. 299–325). Springer.

Hays, D. G., & Singh, A. A. (2012). Qualitative inquiry in clinical and educational settings. Guilford.

Hays, D. G., & Wood, C. (2011). Infusing qualitative traditions in counseling research designs. Journal of Counseling & Development, 89(3), 288–295. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2011.tb00091.x

Heron, M. (2021). Deaths: Leading causes for 2019. National Vital Statistics Reports, 70(9), 1–113. https://doi.org/10.15620/cdc:107021

Hosler, A. S., & Kammer, J. R. (2018). A comprehensive health profile of Guyanese immigrants aged 18–64 in Schenectady, New York. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 20(4), 972–980.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-017-0613-5

Hosler, A. S., Kammer, J. R., & Cong, X. (2019). Everyday discrimination experience and depressive symptoms in urban Black, Guyanese, Hispanic, and White adults. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 25(6), 445–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078390318814620

Hunting, G. (2014). Intersectionality-informed qualitative research: A primer. The Institute for Intersectionality Research and Policy. https://nanopdf.com/download/intersectionality-informed-qualitative-research-a-primer-gemma-hunting_pdf

Indo-Caribbean Alliance, Inc. (2014, February 3). Population analysis of Guyanese and Trinidadians in NYC.

https://www.indocaribbean.org/blog/population-analysis-of-guyanese-and-trinidadians-in-nyc

Jackson, J. S., Neighbors, H. W., Torres, M., Martin, L. A., Williams, D., & Baser, R. (2007). Use of mental health services and subjective satisfaction with treatment among Black Caribbean immigrants: Results from the National Survey of American Life. American Journal of Public Health, 97(1), 60–67. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1716231/

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. SAGE.

Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (2006). Designing qualitative research (4th ed.). SAGE.

Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. SAGE.

Nicolas, G., Dudley-Grant, G. R., Maxie-Moreman, A., Liddell-Quintyn, E., Baussan, J., Janac, N., & McKenny, M. (2021). Psychotherapy with Caribbean women: Examples from USVI, Haiti, and Guyana. Women & Therapy, 44(1–2), 136–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703149.2020.1775993

One World Nations Online. (n.d.). Guyana. https://www.nationsonline.org/oneworld/guyana.htm

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Leech, N. L. (2007). A call for qualitative power analyses. Quality & Quantity, 41, 105–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-005-1098-1

Parekh, K. P., Russ, S., Amsalem, D. A., Rambaran, N., Langston, S., & Wright, S. W. (2012). Prevalence of intimate partner violence in patients presenting with traumatic injuries to a Guyanese emergency department. International Journal of Emergency Medicine, 5(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1865-1380-5-23

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar-McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2015). Multicultural and social justice counseling competencies. American Counseling Association. https://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/competencies/multicultural-and-social-justice-counseling-competencies.pdf

Singh, A. A., Appling, B., & Trepal, H. (2020). Using the Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies to decolonize counseling practice: The important roles of theory, power, and action. Journal of Counseling & Development, 98(3), 261–271. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12321

Spataro, J. (2020). The future of work—the good, the challenging & the unknown. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/blog/2020/07/08/future-work-good-challenging-unknown/

Statimetric. (2022). Distribution of Guyanese people in the US. https://www.statimetric.com/us-ethnicity/Guyanese

United States Census Bureau. (2019). People reporting ancestry: American community survey. http://bit.ly/42RazKC

Williams, D. R., Yu, Y., Jackson, J. S., & Anderson, N. B. (1997). Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology, 2(3), 335–351.

https://doi.org/10.1177/135910539700200305

World Health Organization. (2014). First WHO report on suicide prevention. https://www.who.int/news/item/04-09-2014-first-who-report-on-suicide-prevention

World Population Review. (2023). Suicide rate by country 2023. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/suicide-rate-by-country

Yalom, I. D., & Leszcz, M. (2005). The theory and practice of group psychotherapy (5th ed.). Basic Books.

Shainna Ali, PhD, NCC, ACS, LMHC, is the owner of Integrated Counseling Solutions. John J. S. Harrichand, PhD, NCC, ACS, CCMHC, CCTP, LMHC, LPC-S, is an assistant professor at The University of Texas at San Antonio. M. Ann Shillingford, PhD, is an associate professor at the University of Central Florida. Lea Herbert is a doctoral student at the University of Central Florida. Correspondence may be addressed to Shainna Ali, 3222 Corrine Drive, Orlando, FL 32803, hello@drshainna.com.

Nov 9, 2022 | Volume 12 - Issue 3

Melissa J. Fickling, Matthew Graden, Jodi L. Tangen

The purpose of this phenomenological study was to explore how feminist-identified counselor educators understand and experience power in counselor education. Thirteen feminist women were interviewed. We utilized a loosely structured interview protocol to elicit participant experiences with the phenomenon of power in the context of counselor education. From these data, we identified an essential theme of analysis of power. Within this theme, we identified five categories: (a) definitions and descriptions of power, (b) higher education context and culture, (c) uses and misuses of power, (d) personal development around power, and (e) considerations of potential backlash. These categories and their subcategories are illustrated through narrative synthesis and participant quotations. Findings point to a pressing need for more rigorous self-reflection among counselor educators and counseling leadership, as well as greater accountability for using power ethically.

Keywords: counselor education, power, phenomenological, feminist, women

The American Counseling Association (ACA; 2014) defined counseling, in part, as “a professional relationship that empowers” (p. 20). Empowerment is a process that begins with awareness of power dynamics (McWhirter, 1994). Power is widely recognized in counseling’s professional standards, competencies, and best practices (ACA, 2014; Association for Counselor Education and Supervision [ACES], 2011; Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs [CACREP], 2015) as something about which counselors, supervisors, counselor educators, and researchers should be aware (Bernard & Goodyear, 2014). However, little is known about how power is perceived by counselor educators who, by necessity, operate in many different professional roles with their students

(e.g., teacher, supervisor, mentor).

In public discourse, power may carry different meaning when associated with men or women. According to a Pew Research Center poll (K. Walker et al., 2018) of 4,573 Americans, people are much more likely to use the word “powerful” in a positive way to describe men (67% positive) than women (8% positive). It is possible that these associations are also present among counselors-in-training, professional counselors, and counselor educators.

Dickens and colleagues (2016) found that doctoral students in counselor education are aware of power dynamics and the role of power in their relationships with faculty. Marginalized counselor educators, too, experienced a lack of power in certain academic contexts and noted the salience of their intersecting identities as relevant to the experience of power (Thacker et al., 2021). Thus, faculty members in counselor education may have a large role to play in socializing new professional counselors in awareness of power and positive uses of power, and thus could benefit from openly exploring uses of power in their academic lives.

Feminist Theory and Power in Counseling and Counselor Education

The concept of power is explored most consistently in feminist literature (Brown, 1994; Miller, 2008). Although power is understood differently in different feminist spaces and disciplinary contexts (Lloyd, 2013), it is prominent, particularly in intersectional feminist work (Davis, 2008). In addition to examining and challenging hegemonic power structures, feminist theory also centers egalitarianism in relationships, attends to privilege and oppression along multiple axes of identity and culture, and promotes engagement in activism for social justice (Evans et al., 2005).

Most research about power in the helping professions to date has been focused on its use in clinical supervision. Green and Dekkers (2010) found discrepancies between supervisors’ and supervisees’ perceptions of power and the degree to which supervisors attend to power in supervision. Similarly, Mangione and colleagues (2011) found another discrepancy in that power was discussed by all the supervisees they interviewed, but it was mentioned by only half of the supervisors. They noted that supervisors tended to minimize the significance of power or express discomfort with the existence of power in supervision.

Whereas most researchers of power and supervision have acknowledged the supervisor’s power, Murphy and Wright (2005) found that both supervisors and supervisees have power in supervision and that when it is used appropriately and positively, power contributed to clinical growth and enhanced the supervisory relationship. Later, in an examination of self-identified feminist multicultural supervisors, Arczynski and Morrow (2017) found that anticipating and managing power was the core organizing category of their participants’ practice. All other emergent categories in their study were different strategies by which supervisors anticipated and managed power, revealing the centrality of power in feminist supervision practice. Given the utility of these findings, it seems important to extend this line of research from clinical supervision to counselor education more broadly because counselor educators can serve as models to students regarding clinical and professional behavior. Thus, understanding the nuances of power could have implications for both pedagogy and clinical practice.

Purpose of the Present Study

Given the gendered nature of perceptions of power (Rudman & Glick, 2021; K. Walker et al., 2018), and the centrality of power in feminist scholarship (Brown, 1994; Lloyd, 2013; Miller, 2008), we decided to utilize a feminist framework in the design and execution of the present study. Because power appears to be a construct that is widely acknowledged in the helping professions but rarely discussed, we hope to shed light on the meaning and experience of power for counselor educators who identify as feminist. We utilized feminist self-identification as an eligibility criterion with the intention of producing a somewhat homogenous sample of counselor educators who were likely to have thought critically about the construct of power because it figures prominently in feminist theories and models of counseling and pedagogy (Brown, 1994; Lloyd, 2013; Miller, 2008).

Method

We used a descriptive phenomenological methodology to help generate an understanding of feminist faculty members’ lived experiences of power in the context of counselor education (Moustakas, 1994; Padilla-Díaz, 2015). Phenomenological analysis examines the individual experiences of participants and derives from them, via phenomenological reduction, the most meaningful shared elements to paint a portrait of the phenomenon for a group of people (Moustakas, 1994; Starks & Trinidad, 2007). Thus, we share our findings by telling a cohesive narrative derived from the data via themes and subthemes identified by the researchers.

Sample

After receiving IRB approval, we recruited counselor educators via the CESNET listserv who were full-time faculty members (e.g., visiting, clinical, instructor, tenure-track, tenured) in a graduate-level counseling program. We asked for participants of any gender who self-reported that they integrated a feminist framework into their roles as counselor educators. Thirteen full-time counselor educators who self-identified as feminist agreed to be interviewed on the topic of power. All participants were women. Two feminist-identified men expressed initial interest in participating but did not respond to multiple requests to schedule an interview. The researchers did not systematically collect demographic data, relying instead on voluntary participant self-disclosure of relevant demographics during the interviews. All participants were tenured or tenure-track faculty members. Most were at the assistant professor rank (n = 9), a few were associate professors (n = 3), and one was a full professor who also held various administrative roles during her academic career (e.g., department chair, dean). During the interviews, several participants expressed concern over the high potential for their identification by readers due to their unique identities, locations, and experiences. Thus, participants will be described only in aggregate and only with the demographic identifiers volunteered by them during the interviews. The participants who disclosed their race all shared they were White. Nearly all participants disclosed holding at least one marginalized identity along the axes of age, disability, religion, sexual orientation, or geography.

Procedure

Once participants gave informed consent, phone interviews were scheduled. After consent to record was obtained, interviewers began the interviews, which lasted between 45–75 minutes. We utilized an unstructured interview format to avoid biasing the data collection to specific domains of counselor education while also aiming to generate the most personal and nuanced understandings of power directly from the participants’ lived experiences (Englander, 2012). As experienced interviewers, we were confident in our ability to actively and meaningfully engage in discourse with participants via the following prompt: “We are interested in understanding power in counselor education. Specifically, please speak to your personal and/or professional development regarding how you think about and use power, and how you see power being used in counselor education.” After the interviews, we all shared the task of transcribing the recordings verbatim, each transcribing several interviews. All potentially identifying information (e.g., names, institutional affiliations) was excluded from the interview transcripts.

Data Analysis

Data analysis began via horizontalization of two interview transcripts by each author (Moustakas, 1994; Starks & Trinidad, 2007). Next, we began clustering meaning units into potential categories (Moustakas, 1994). This initially revealed 21 potential categories, which we discussed in the first research team meeting. We kept research notes of our meetings, in which we summarized our ongoing data analysis processes (e.g., observations, wonderings, emerging themes). These notes helped us to revisit earlier thinking around thematic clustering and how categories interrelated. The notes did not themselves become raw data from which findings emerged. Through weekly discussions over the course of one year, the primary coders (Melissa Fickling and Matthew Graden) were able to refine the categories through dialoguing until consensus was reached, evidenced by verbal expression of mutual agreement. That is, the primary coders shared power in data analysis and sometimes tabled discussions when consensus was not reached so that each could reflect and rejoin the conversation later. As concepts were refined, early transcripts needed to be re-coded. Our attention was not on the quantification of participants or categories, but on understanding the essence of the experience of power (Englander, 2012; Moustakas, 1994). The themes and subthemes in the findings section below were a fit for all transcripts by the end of data analysis.

Researchers and Trustworthiness

Fickling and Jodi Tangen are White, cis-hetero women, and at the time of data analysis were pre-tenured counselor educators in their thirties who claimed a feminist approach in their work. Graden was a master’s student and research assistant with scholarly interests in student experiences related to gender in counseling and education. We each possess privileged and marginalized identities, which facilitate certain perspectives and blind spots when it comes to recognizing power. Thus, regular meetings before, during, and after data collection and analysis were crucial to the epoche and phenomenological reduction processes (Moustakas, 1994) in which we shared our assumptions and potential biases. Fickling and Graden met weekly throughout data collection, transcription, and analysis. After the initial research design and data collection, Tangen served primarily as auditor to the coding process by comparing raw data to emergent themes at multiple time points, reviewing the research notes written by Fickling and Graden and contributing to consensus-building dialogues when needed.

Besides remaining cognizant of the strengths and limitations of our individual positionalities with the topic and data, we shared questions and concerns with each other as they arose during data analysis. Relevant to the topic of this study, Fickling served as an administrative supervisor to Graden. This required acknowledgement of power dynamics inherent in that relationship. Graden had been a doctoral student in another discipline prior to this study and thus had firsthand context for much of what was learned about power and its presence in academia. Fickling and Graden’s relationship had not extended into the classroom or clinical supervision, providing a sort of boundary around potential complexities related to any dual relationships. To add additional trustworthiness to the findings below, we utilized thick descriptions to describe the phenomenon of interest while staying close to the data via quotations from participants. Finally, we discuss the impact and importance of the findings by highlighting implications for counselor educators.

Findings

Through the analysis process, we concluded that the essence (Moustakas, 1994)—or core theme—of the experience of power for the participants in this study is engagement in a near constant analysis of power—that of their colleagues, peers, students, as well as of their own power. Participants analyzed interactions of power within and between various contexts and roles. They shared many examples of uses of power—both observed and personally enacted—which influenced their development, as well as their teaching and supervision styles. Through the interviews, participants shared the following:

(a) definitions and descriptions of power, (b) higher education context and culture, (c) uses and misuses of power, (d) personal development around power, and (e) considerations of potential backlash. These five categories comprised the overarching theme of analysis of power and are described below with corresponding subcategories where applicable, identified in italics.

Definitions and Descriptions of Power

Participants spent much of their time defining and describing just what they meant when they discussed power. For the feminist counselor educators in this study, power is about helping. One participant, when describing power, captured this sentiment well when she said, “I think of the ability to affect change and the ability to have a meaningful impact.” Several participants shared this same idea by talking about power as the ability to have influence. Participants expressed a desire to use power to do good for others rather than to advance their personal aspirations or improve their positions. Use of power for self-promotion was referenced to a far lesser extent than using power to promote justice and equity, and any self-promotional use was generally in response to perceived personal injustice or exploitation. At times, participants described power by what it is not. One participant said, “I don’t see power as a negative. I think it can be used negatively.” Several others shared this sentiment and described power as a responsibility.

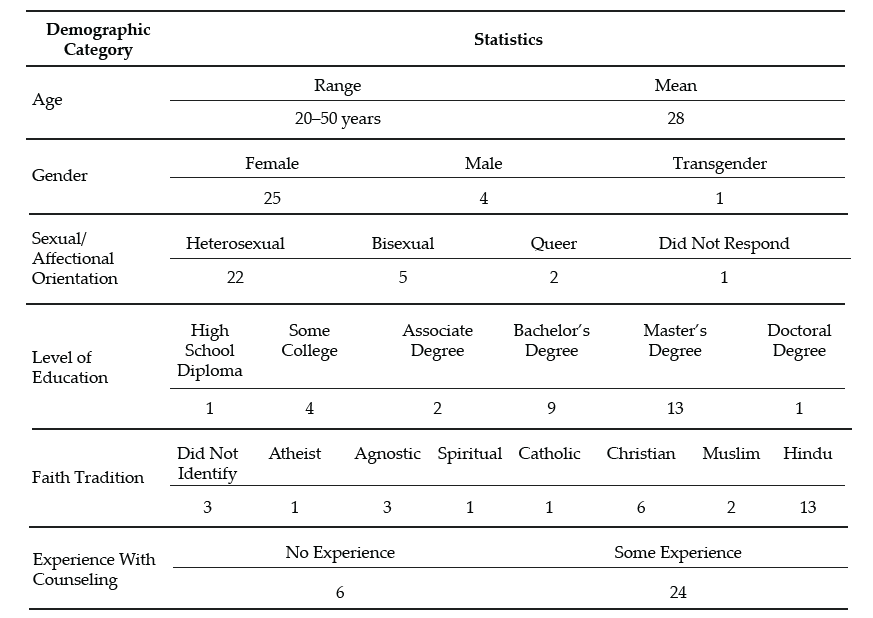

In describing power, participants identified feelings of empowerment/disempowerment (Table 1). Disempowerment was described with feeling words that captured a sense of separation and helplessness. Empowerment, on the other hand, was described as feeling energetic and connected. Not only was the language markedly different, but the shifts in vocal expression were also notable (nonverbals were not visible) when participants discussed empowerment versus disempowerment. Disempowerment sounded like defeat (e.g., breathy, monotone, low energy) whereas empowerment sounded like liveliness (e.g., resonant, full intonation, energetic).

Table 1

Empowered and Disempowered Descriptors

| Descriptors |

| Empowered |

Disempowered |

| Authentic

Free

Good

Heard

Congruent

Genuine

Selfless

Hopeful

Confident

Serene

Connected

Grounded

Energized |

Isolated

Disenfranchised

Anxious

Separated Identity

Not Accepted

Disheartened

Helpless

Small

Weak

Invisible

Wasting Energy

Tired

Powered Down |

Participants identified various types of power, including personal, positional, and institutional power. Personal power was seen as the source of the aspirational kinds of power these participants desired for themselves and others. It can exist regardless of positional or institutional power. Positional power provides the ability to influence decisions, and it is earned over time. The last type of power, institutional, is explored more through the next theme labeled higher education context and culture.

Higher Education Context and Culture

Because the focus of the study was power within counselor educators’ roles, it was impossible for participants not to discuss the context of their work environments. Thus, higher education context and culture became a salient subtheme in our findings. Higher education culture was described as “the way things are done in institutions of higher learning.” Participants referred to written/spoken and unwritten/silent rules, traditions, expectations, norms, and practices of the academic context as barriers to empowerment, though not insurmountable ones. Power was seen as intimately intertwined with difficult departmental relationships as well as the roles of rank and seniority for nearly all participants. Most also acknowledged the influence of broader sociocultural norms (i.e., local, state, national) on higher education in general, noting that institutions themselves are impacted by power dynamics.

One participant who said that untenured professors have much more power than they realize also said that “power in academia comes with rank.” This contradiction highlights the tension inherent in power, at least among those who wish to use it for the “greater good” (as stated by multiple participants) rather than for personal gain, as these participants expressed.

More than one participant described power as a form of currency in higher education. This shared experience of power as currency, either through having it or not having it, demonstrated that to gain power to do good, as described above, one must be willing or able to be seen as acceptable within the system that assigns power. Boldness was seen by participants as something that can happen once power is gained. Among non-tenured participants, this quote captures the common sentiment: “Now, once I get tenure, that can be a different conversation. I think I would feel more emboldened, more safe, if you will, to confront a colleague in that way.” The discussion of context and boldness led to the emergence of a third theme, which we titled uses and misuses of power.

Uses and Misuses of Power

Participants provided many examples of their perceptions of uses and misuses of power and linked these behaviors to their sense of ethics. Because many of the examples of uses of power were personal, unique, and potentially identifiable, participants asked that they not be shared individually in this manuscript. Ethical uses of power were described as specific ways in which participants remembered power being used for good such as intervention in unfair policies on behalf of students. Ethical uses of power shared the characteristics of being collaborative and aligned with the descriptors of “feeling empowered” (Table 1).