Oct 14, 2016 | Article, Volume 6 - Issue 4

Ashley J. Blount, Dalena Dillman Taylor, Glenn W. Lambie, Arami Nika Anwell

Wellness is an integral component of the counseling profession and is included in ethical codes, suggestions for practice and codes of conduct throughout the helping professions. Limited researchers have examined wellness in counseling supervision and, more specifically, clinical mental health supervisors’ experiences with their supervisees’ levels of wellness. Therefore, the purpose of this phenomenological qualitative research was to investigate experienced clinical supervisors’ (N = 6) perceptions of their supervisees’ wellness. Five emergent themes from the data included: (a) intentionality, (b) self-care, (c) humanness, (d) support, and (e) wellness identity. As counselors are at risk of burnout and unwellness because of the nature of their job (e.g., frequent encounters with difficult and challenging client life occurrences), research and education about wellness practices in the supervisory population are warranted.

Keywords: supervision, wellness, unwellness, phenomenological qualitative research, helping professions

Wellness is an integral component of the counseling profession (Myers & Sweeney, 2004; Witmer, 1985) and is included in ethical codes, suggestions for practice and codes of conduct throughout the helping professions of counseling, psychology and social work (American Counseling Association [ACA], 2014; American Psychological Association [APA], 2010; National Association of Social Workers [NASW], 2008). Yet, individuals in the helping professions do not necessarily practice wellness or operate from a wellness paradigm, even though counselors are susceptible to becoming unwell because of the nature of their job (Lawson, 2007; Skovholt, 2001). As a helping professional, proximity to human suffering and trauma, difficult life experiences and additional occupational hazards (e.g., high caseloads) make careers like counseling costly for helpers (Sadler-Gerhardt & Stevenson, 2011). Further, helpers may be vulnerable to experiencing burnout because of their ability (and necessity because of their career) to care for others (Sadler-Gerhardt & Stevenson, 2011). Compassion fatigue, vicarious traumatization and other illness-enhancing issues often coincide with burnout, increasing the propensity for therapists to become unwell (Lambie, 2007; Puig et al., 2012). Extended periods of stress also can lead to helping professionals’ impairment and burnout and can negatively impact quality of client services (Lambie, 2007). Furthermore, counselors who are unwell have the potential of acting unethically and may in turn harm their clients (Lawson, 2007). Thus, it is imperative that helping professionals’ wellness be examined.

More specifically, counseling professionals are required to follow guidelines that support a wellness paradigm. ACA (2014) states that counselors should monitor themselves “for signs of impairment from their own physical, mental, or emotional problems” (Standard C.2.g.). In addition, counselors are instructed to monitor themselves and others for signs of impairment and “refrain from offering or providing professional services when such impairment is likely to harm a client or others” (ACA, 2014, F.5.b.). The Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP; 2015) supports counselors having a wellness orientation and a focus on prevention (Section II.5.a.) and that counselors promote wellness, optimal functioning and growth in clients (Section II.2.e.). Thus, prevention of impairment and a wellness focus are intertwined throughout the standards of the counseling profession. Consequently, it is unethical for counseling professionals to operate while personally or professionally impaired.

Wellness and Supervision in Counseling

In the following section, the importance of wellness and potential impacts of unwellness in the counseling profession will be discussed. Specifically, stressors contributing to impairment will be highlighted. In addition, supervision within a counseling context and general information regarding the supervisory experience will be reviewed.

Wellness and the Counseling Profession

The counseling profession was founded on a wellness philosophy, with holistic wellness including personal characteristics, such as nutritional wellness, physical wellness, stress management and self-care (Puig et al., 2012), and other realms including spiritual, occupational and intellectual well-being (Myers & Sweeney, 2008). According to Carl Rogers (1961), personal characteristics influence counselors’ ability to help others. For instance, individual wellness may influence how knowledgeable, self-aware and skillful supervisees are in relation to working with clients (Lambie & Blount, 2016). Counselors who are well are more likely to be helpful to their clients (Lawson & Myers, 2011; Venart, Vassos, & Pitcher-Heft, 2007), and counselors’ mental health and wellness impacts the quality of services clients receive (Roach & Young, 2007). Therefore, counselor preparation programs and supervisors should discuss wellness and areas in which impairment could arise when training students to become counselors and supervisors (Roach & Young, 2007). Though wellness is a core aspect of counselor training and preparation, many practicing counselors report their colleagues to be stressed (33.29%), distressed (12.24%) and impaired (4.05%; Lawson, 2007).

Individuals who are attracted to and enter into helping fields often appear to have severe adjustment and personality issues, and these individuals may range from students entering into programs to faculty members employed by institutions (Witmer & Young, 1996). In addition, counselors are often remiss about taking their own advice about wellness (Cummins, Massey, & Jones, 2007) and frequently preach wellness to their clients but do not practice wellness personally (Myers, Mobley, & Booth, 2003). Many counselors do not see their own impairment or are unwilling to take the steps to get help (Kottler, 2010), supporting the importance of supervisors identifying and addressing their supervisees’ impairment. Consequently, counselors seeing clients in agency settings, private practices and other settings may experience stressors that are influencing their wellness and, in parallel, the wellness of their clients.

With the counseling profession having a wellness undertone, counselors are expected to promote well-being in their clients and model appropriate wellness lifestyles. Nevertheless, counselors experience job stressors that impact their abilities to be effective helping professionals (Puig et al., 2012). Counselors face several stressors within their career such as managed care, financial limitations, high caseloads, severe mental disorders in clientele and lack of support (O’Halloran & Linton, 2000). Other factors impacting counselors and mental health professionals include: (a) compassion fatigue (Perkins & Sprang, 2012), (b) unhappy workplace relationships (Lambie, 2007), (c) vicarious trauma (Trippany, White Kress, & Wilcoxon, 2004), and (d) general fatigue (Lambie, 2007). Moreover, these systemic factors contribute to increased likelihood for counselors to experience burnout and impairment, impacting their clients’ therapeutic outcomes (Puig et al., 2012). Furthermore, counselors may not disclose their impairment because of denial, shame, professional priorities, lack of responsibility and fear of reprisal (Kottler & Hazler, 1996).

Counselor impairment occurs when counselors ignore, minimize and dismiss their personal needs for health, self-care, balance and wellness (Lawson, Venart, Hazler, & Kottler, 2007). Lawson and colleagues (2007) stated counselors need awareness of their personal wellness and should work to maintain their wellness. In addition, ACA (2014) states that counselors are responsible for seeking help if they are impaired and that it is the duty of colleagues and supervisors to recognize professional impairment and take appropriate action (Standard C.2.g.). Thus, counselors and supervisors are responsible for not only maintaining their personal wellness, but are also responsible for monitoring the wellness or impairment of their colleagues. One of the platforms for monitoring counselor wellness is supervision.

Supervision

ACA (2014) stipulates that supervision involves a process of monitoring “client welfare and supervisee clinical performance and professional development” (Standard F.1.a.). Supervision is an integral component of the counseling profession, involving a relationship in which an experienced professional facilitates the development of therapeutic competence in another (Bernard & Goodyear, 2014). Furthermore, supervision is fundamental in developing and evaluating counselors’: (a) skills (Borders, 1993), (b) wellness (Lenz, Sangganjanavanich, Balkin, Oliver, & Smith, 2012), and (c) development into competent and effective counselors (Swank, Lambie, & Witta, 2012). Clinical supervisors are tasked with evaluating their supervisees’ effectiveness in addition to their level of wellness (Puig et al., 2012). Consequently, stressors, such as personal and cultural issues, addictions, burnout, and other counseling-related occupational challenges, may negatively influence supervisees’ wellness and ability to be effective helping professionals.

Supervision “provides a means to impart necessary skills; to socialize novices into particular profession’s values and ethics; to protect clients; and finally, to monitor supervisees’ readiness to be admitted to the profession” (Bernard & Goodyear, 2014, p. 5). Supervisors have the unique opportunity to operate from a wellness paradigm, socialize their supervisees to wellness practices, monitor supervisee wellness, and gauge how supervisees’ wellness influences client outcomes (Lambie & Blount, 2016). As a result, supervisors who operate from a wellness paradigm and evaluate their supervisees’ wellness may influence the wellness of supervisees’ clients by encouraging positive client outcomes (Lawson, 2007; Lenz & Smith, 2010). As such, supervisee and supervisor wellness is an important component of counselor preparation programs and clinical supervision (Lenz et al., 2012).

Counselor educators (Wester, Trepal, & Myers, 2009), clinical supervisors (Lenz & Smith, 2010; Storlie & Smith, 2012), counselors-in-training (Myers & Sweeney, 2004; Smith, Robinson, & Young, 2007), and licensed counselors (Lawson, 2007; Myers et al., 2003) face challenges in obtaining optimal well-being (e.g., high caseloads, proximity to client trauma, empathizing with students and clients). Supervisors play an integral role in counselor trainee development and can model appropriate wellness behaviors for their supervisees. Furthermore, supervisors have the unique opportunity to work closely with their supervisees and provide an in-depth look at how emerging counselors are learning about wellness behaviors, partaking in wellness actions and promoting wellness in their clients. Nevertheless, no available research has examined experienced clinical supervisors’ perceptions of their supervisees’ wellness. Because clinical supervisors have a close relationship with their supervisees, their perceptions of their supervisees’ wellness can provide important information for the counseling profession. Therefore, the following research question guided our investigation: What are clinical mental health supervisors’ experiences with their supervisees’ wellness?

Methodology

Identifying themes related to clinical supervisors’ experiences of their supervisees’ wellness provides insights for both supervisors and supervisees. The researchers followed a psychological phenomenological methodology (Creswell, 2013a; Moustakas, 1994), allowing for both the meaning (themes) and the essence (experience) of the participants to be examined. In phenomenological research, researchers attempt to identify the essence of participants’ experiences surrounding a phenomenon. By developing interview questions and using an interview protocol technique (Creswell, 2013b), the researchers petitioned participants’ (i.e., clinical supervisors) direct and conscious experiences (Hays & Wood, 2011) to assess their perceptions of their supervisees’ wellness (see Table 1). The following section includes discussion on: (a) epoche and bracketing, (b) participants, (c) procedure, (d) qualitative data analysis and (e) trustworthiness.

Epoche

The first course of action in phenomenological analysis is called epoche (Patton, 2015); therefore, the research team members are described with some of their potential biases. The research team consisted of two counselor educators, a counselor education doctoral candidate, and a counseling master’s student (one man and three women), all of whom identify as Caucasian. All of the researchers were affiliated with the same institution, a large, public, CACREP-accredited university located in the Southeastern United States. In addition, biases relating to the effectiveness of supervisory styles were discussed, and bracketing throughout the data analysis was implemented in order to minimize bias and allow for participant perspectives to be at the forefront. Participant experiences were documented in personal interviews and in the form of collaborative discussions.

Participants

The participants consisted of clinical supervisors who were purposefully selected from a Department of Health and Human Services counseling professional list from a large, southeastern state. Initial criteria for participation in the investigation included: (a) being clinical supervisors for 10 or more years and (b) being in an active supervisory role (i.e., providing supervision). Twenty-six participants initially responded, with 17 individuals meeting the necessary requirements for participation. The final sample consisted of six clinical supervisors, based on individuals who agreed to participate.

Criterion were established to support interviewing only “experienced” supervisors (i.e., supervisors with extensive supervision experience) and participants’ mean number of years of experience as clinical mental health supervisors was 21.2 years. Four of the experienced supervisors identified as female and two identified as male, and their ages ranged from 49 years to 63 years (M = 56.5 SD = 4.93). In addition, four of the participants identified as Caucasian (n = 4), one participant identified as Hispanic (n = 1), and one participant identified as Other (n = 1; i.e., chose not to disclose). The participants represented the following theoretical approaches: humanistic/Rogerian (n = 3), integrative/eclectic (n = 2) and cognitive-behavioral (n = 1). Primary supervision models for the clinical supervisors included: eclectic/integrative (n = 4), person-centered (n = 1) and solution focused (n = 1). The participants served as clinical supervisors at six different mental health agencies throughout a large southeastern state, supporting transferability of the findings.

In reference to wellness, the participants were asked to evaluate their level of wellness prior to participating in the interview process. Specifically, participants were asked to define what wellness meant for them as well as elaborate on the specific areas they felt influenced their wellness. Participants then rated on a 5-point Likert scale their level of overall wellness (i.e., 1 indicating very low wellness, 5 indicating very high wellness). Four of the six participants rated their overall wellness as 5 (very high wellness), while the remaining two individuals rated their overall wellness as 3 (average wellness) and 4 (high wellness) respectively. Thus, the participants reported having average to high levels of personal wellness.

Procedure

Before conducting the investigation, Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained. Following IRB approval, the researchers employed purposeful sampling (Hays & Wood, 2011) to recruit participants by accessing a public listing of all mental health practitioners in a southeastern state in the United States. The Department of Health and Human Services counseling professional list was utilized, which included e-mail addresses, telephone numbers and mailing addresses of potential participants. Twenty-six participants met the initial response criteria (i.e., 10 or more years of supervisory experience). Snowballing also was used to recruit additional participants (i.e., asking participants for a name of an individual who might fit the study criteria). However, of the 26 participants, 17 supervisors responded with complete general demographic questionnaires and sufficient number of years as supervisors (i.e., minimum of 10 years). Six individuals fit the final purposive sampling criteria for participating in the investigation (e.g., had over 10 years of clinical mental health supervisory experience, still practicing as supervisors in diverse agencies, and having a complete general demographic form).

The first round of data collection was essential in confirming the eligibility of the participants (e.g., completion of the general demographic questionnaire and informed consent form). The demographic questionnaire consisted of questions about personal wellness, ethnicity, theoretical orientation, age, gender and primary population served. Following completion of the initial documents, individual interviews were scheduled. The second round of data collection involved face-to-face or Skype interviews with each participant, where participants were asked the general research question: What are your experiences with your supervisees’ wellness? The researchers also had nine supporting interview questions, which were developed through a rigorous process involving: (a) researchers’ development of an initial question blueprint derived from the literature reviewed for the study, (b) experts’ review and modification of the initial questions, and (c) an initial pilot group testing the questions. The experts were comprised of educators with experience in conducting qualitative research, experience providing supervision and familiarity with the wellness paradigm.

The interview protocol included instructions for the interviewer, research questions, probes to follow the research questions (if needed), space for recording comments, and space for reflective comments to ensure all interviews followed the same procedure (Creswell, 2013a). The general interview questions were developed to aid in addressing the overall question of supervisors’ perceptions of their supervisees’ wellness and all individual interviews were audio recorded and then transcribed. The final list of interview questions is presented in Table 1. The researchers conducted all interviews individually, and to support the effectiveness of gathering the participants’ experiences, member checking was implemented (Creswell, 2013a). Specifically, all participants were e-mailed a copy of their interview transcription, along with a statement of themes and interpretation of the interview’s meaning. All participants (N = 6) responded to member checking and stated that their transcribed interview was accurate and agreed with the themes derived from their interviews.

Table 1

Interview Question Protocol

|

Data and Rationale

|

Draft Interview Questions

|

Prompts and Elicitations

|

| Values (gaining perceptions) |

1. What does wellness mean to you? |

Wellness, health, well-being |

| Beliefs, Values (learning expectations, perceptions) |

2. What influences wellness in counselors? |

Counselor-specific wellness |

| Values (gaining perceptions) |

3. What is the most important aspect of wellness? |

Crucial component(s) |

| Values, (gaining perceptions, opinions) |

4. Is wellness the same or different for everyone? |

Wellness looks like . . . individualized |

| Experiences, Values (what influences clients) |

5. Does wellness influence your supervisees’ client(s)? |

Wellness impacts clients, or supervisees’ clients |

| Experiences, Values (gaining information on standards of wellness and if they are being upheld) |

6. Do you feel your supervisees uphold to standards of wellness in the counseling field? |

Meeting standards, CACREP, ACA Ethics |

| Beliefs, Experiences (expectations of supervisors, experiences) |

7. What does unwellness in counseling supervisees look like? |

Depiction of unwellness |

| Beliefs, Experiences (expectations, experiences of seasoned counselors) |

8. What does unwellness in counselors-in-the field look like? |

Unwellness “picture” |

| Values, Beliefs (gaining other information relating to wellness) |

9. Is there anything else you would like to tell me about wellness? |

Personal wellness philosophy |

| Note: Draft Interview Questions were used in all participant interviews. |

Data Analysis

The researchers followed Creswell’s (2013a) suggested eight steps in conducting phenomenological research: (a) determining that the research problem could best be examined via a phenomenological approach (e.g., discussed the phenomenon of wellness and its relation to the counseling field and in the supervision of counselors); (b) identifying the phenomenon of interest (wellness); (c) bracketing personal experiences with the phenomenon; (d) collecting data from a purposeful sample; (e) asking participants interview questions that focused on gathering data relating to their personal experiences of the phenomenon; (f) analyzing data for significant statements (horizontalization; Moustakas, 1994) and developing clusters of meaning; (g) developing textural and structural descriptions from the meaning units; and (h) deriving an overall essence. In order to maintain organization, the researchers implemented color-coding of statements by selecting one color for initial significant statements or codes (e.g., step f), another color for textural descriptions (e.g., what participants experienced in step g) and a final color to represent structural descriptions (e.g., how participants experienced the phenomenon in step g) of the data (Creswell, 2013a). Finally, the researchers determined an overall essence (step h) based on the structural descriptions of the participants’ interview transcriptions. Following individual coding (i.e., steps f, g, and h), the researchers discussed their initial results and discrepancies, evaluating these discrepancies until reaching consensus.

Trustworthiness

The researchers established trustworthiness by bracketing researcher bias, implementing written epochs, triangulating data, implementing member checking, and providing a thick description of data (Creswell, 2013a; Hays & Wood, 2011). Coinciding with Denzin and Lincoln (2005), the researchers triangulated data collection using (a) a general demographic questionnaire, (b) semi-structured interviews and (c) open-ended research questions. Epochs allowed the researchers to increase their awareness on any biases present and set aside their personal beliefs. Member checking was employed in order to confirm the themes were consistent with the participants’ experiences. As such, participants were provided the opportunity to voice any concerns or discrepancies in their interview transcripts and in their derived meaning statements. The participants indicated no discrepancies or concerns. A thick description (detailed account of participants’ experiences; Lincoln & Guba, 1985) of the data was supported by the participants’ statements and derived themes. In addition, an external auditor was used to evaluate the overall themes and essence of the interviews and to mitigate researcher bias. The external auditor examined the transcripts separate from the other research members in order to evaluate the effectiveness of the derived themes and participant experiences.

Results

Following audio recording and transcription of the participant interviews, the researchers examined the participants’ responses and generated narratives of the emergent phenomena. As a result, themes of supervisees’ wellness from the clinical mental health supervisors’ experiences were derived and included: (a) intentionality, (b) self-care, (c) humanness, (d) support and (e) wellness identity. The themes are discussed in detail below.

Intentionality

Intentionality was defined as the supervisor purposefully utilizing supervisory techniques and behaviors that elicit self-awareness and understanding in their supervisees (i.e., both of self and of their clients). The process of intentionality involved the supervisor actively engaging supervisees in discussions about wellness as well as actively modeling for the supervisees. Within the interviews, supervisors alluded to a parallel process that occurred between the supervisor–supervisee and supervisee–client dyads. When the supervisor intentionally modeled appropriate wellness between self and supervisee, the supervisee could then implement similar wellness activities between self and client. Reflecting on the process of supervisory modeling, Supervisor #1 stated:

The supervisor . . . has a lot . . . a lot of influence . . . checking in, what are you doing to take care of yourself? You seem really stressed, what is your wellness plan? What is your stress management? How do you detach yourself and unplug yourself from your responsibilities with your clients at work . . . to take care of you?

As depicted, the supervisor intentionally asked the supervisee questions relating to personal wellness and started a conversation about supervisees separating themselves from their work life. Supervisor #2 confirmed the importance of modeling as evidenced by the statement, “you can’t preach to someone to do something if you are not doing it yourself.” In other words, the supervisor alluded to the idea that supervisors must model appropriate professional and personal behaviors to their supervisees. Additionally, the supervisors discussed the impact of a trickledown effect (e.g., parallel process): how the supervisor approaches supervisees in turn affects how supervisees approach their clients. For instance, if the supervisor exhibited signs of burnout, then the behaviors would directly impact their relationship and understanding of the supervisee, which would indirectly impact their supervisee’s clients. Supervisor #3 noted that the wellness of supervisees influenced client wellness by saying “Oh, I can definitely see when my supervisees are unwell and how that directly influences their work with clients. It’s like they’re (supervisees) not on top of their game . . . like they’re not as effective with clients.” Furthermore, supervisors noted the use of direct interventions to help supervisees gain increased self-awareness after recognizing supervisees’ potential unwellness. Supervisor #5 stated in reference to a conversation with a supervisee, “I want you to be in the field to better help people by helping yourself and looking at your own issues.” Thus, supervisors need to be intentional when helping supervisees become more effective and more well in both their personal and professional lives.

Self-Care

Self-care was defined as the necessity of taking care of one’s self in order to be a better asset to supervisees and clients. The self-care theme supported the idea that “you cannot give away that which you do not possess” (Bratton, Landreth, Kellam, & Blackard, 2006, p. 15), which is consistent in the counseling and other helping professional literature (Lawson, 2007). In other words, we must take care of ourselves before we are able to care for others. Self-care is delineated from the theme of intentionality in this investigation in that supervisors reflected the importance of their own self-awareness to gauge wellness, especially to alleviate the potential for burnout. For example, Supervisor #4 stated, “If I’m not well, I can’t really help someone else get well.” Whereas the theme of intentionality reflects encouraging supervisees’ self-awareness, the self-care theme notes the importance of supervisors being self-aware and the specific actions supervisors felt they and their supervisees could take to promote self-care in their own lives. As Supervisor #6 said, “it’s an incredible field and it can be a very, very draining field if you aren’t careful, if you don’t take care of yourself.” Through the supervisors’ process of reflection and recognition, they were able to respond with care and compassion to their supervisees. However, as Supervisor #5 indicated when reflecting on counselor and supervisor burnout,

[It] happens to every single counselor, they’re going to experience compassion fatigue at some point in their career because it is a burnout job, and so to recognize . . . the signs . . . sometimes it takes someone else to point it out to us.

It is crucial to take care of oneself in counseling and be open to feedback from others who may see our behaviors from an objective standpoint. Furthermore, the supervisors noted the critical impact of taking care of themselves through activities outside of the workplace and leaving client and supervisee concerns at work. For example, Supervisor #3 noted:

I feel you need to take care of yourself, you need to do stuff for you . . . I’m clear to sit down with all of them [supervisees] and say . . .what are you going to . . . do good for yourself today . . . what are you going to do for you?

By creating differentiation between personal and professional life, supervisors and supervisees are able to rejuvenate, leading to better care for supervisees as Supervisor #1 indicated:

I do feel there are many ways to go about it . . . there’s a whole mindfulness movement, and yoga . . . animals . . . those are all ways we can go ahead and keep ourselves well. I think play is a component of keeping yourself well and . . . there are different definitions of play, but I would define it as when you’re so involved in doing something that you lose track of time. That could be art activities . . . dancing, doing something fun with your dog . . . playing games . . . being involved in something where time stands still and you’re totally in the moment. . . . I think that’s another key piece of really staying well.

As a result, the self-care theme involves supervisors identifying and implementing strategies to keep themselves well, as well as supervisees engaging in activities to support their own self-care journeys. Similar to other wellness research in the helping professions (Lawson, 2007; Myers & Sweeney, 2005b; Skovholt, 2001), self-care is paramount to supporting personal wellness, as well as having the capacity to promote wellness in others—supervisors with supervisees and in parallel, supervisees with clients.

Humanness

Humanness was defined as the supervisors’ and supervisees’ culture, history, background and the influences of previous life experiences on the therapeutic relationship. Our past actions, memories and families of origin influence our worldview and current functioning. As Supervisor #3 noted, “I define wellness on a personal level, it has to do with me and my personhood, it is unique and is based on my wants and needs.” In reference to the influence of individuals’ history and background, Supervisor #2 stated, “for myself definitely it was pretty much the way I grew up . . . it depends on the population, it depends on where they were raised. . . . There’s just too many dependent variables for it.” At times, supervisors noted that these factors lead to unintentional blindness between and within the dyad (i.e., supervisor–supervisee, supervisee–client). Supervisor #3 noted that “we all have biases, we all have prejudices on some level. Are you willing to acknowledge that you are struggling with this, but I am willing to work on this, willing to go to workshops or go into therapy?” Without reflection or self-awareness, supervisors and supervisees are susceptible to similar roadblocks and “stuckness” as their clients. For instance, Supervisor #4 noted the influence of current life events impacting her overall wellness:

I think to add to that, it is the nature of our human experience. . . . we are going to go through phases in our lives where things are affected to the point to where you would say this aspect of my life is not well right now.

Thus, supervisors perceive both their humanness (e.g., backgrounds and cultures) and their supervisees’ humanness qualities as influential to the therapeutic relationship and important in supervisees’ actions in counseling situations as well as personal settings (Lambie, 2006).

Support

Support was defined as leaning on and connecting with others (e.g., peer-to-peer, colleagues, friends, partners). Supervisors emphasized the importance of both themselves and their supervisees developing and maintaining significant relationships within the context of their job and outside the work setting. Supervisor #6 reflected that “support is integral to . . . overall wellness and, being that we are social creatures . . . support [is] really important for us.” Relationships at work can be crucial for processing tough client cases and personal issues that appear to be encroaching upon work with clients. For example, Supervisor #3 emphasized, “I think there has to be a support system of counselors who have been in the field . . . and having your own therapist.” At the same time, social relationships outside work are equally important. Similar to self-care and intentionality, separating personal life and professional life aids the supervisor and supervisee in leaving client cases at work and enjoying life beyond the role as a counselor. Within the literature, the influence of support aids supervisors and supervisees in achieving wellness and minimizing the likelihood of counselor burnout (Lambie, 2007; Lee, Cho, Kissinger, & Ogle, 2010).

Wellness Identity

Wellness identity was defined as the supervisors and supervisees operating from a wellness platform. Supervisors noted the necessity of holding this wellness platform in the forefront of conversations with students, other supervisors, and other therapists and counselors. As Supervisor #3 reflected,

We practice a strengths-based model and we see that the wellness model is depicted much, much more not only in the literature but also in the things that come about. . . . I’d rather see research in wellness rather than case research in defects.

Through attaching wellness to one’s identity as a counselor, supervisors and supervisees are compelled to continuous self-reflection on how external factors impact their work with supervisees and clients. Supervisor #1 stated “wellness is who we are, if we find ourselves straying, we probably need to re-evaluate things.” Furthermore, supervisors indicated in their interviews that wellness is an important topic for counselors and counselor educators to reflect upon and teach and discuss with students and supervisees. For instance, Supervisor #2 stated in relation to the idea of a wellness identity: “It comes from the teaching that one receives in the classroom. . . . I think that the issues have really brought it to the forefront and it has allowed us to teach wellness and to talk about it. I think teaching is the driving force.”

As shown in the wellness identity theme, all of the supervisors supported the idea that having a wellness base from which helpers operate is important. Additionally, the participants noted the importance of an open dialogue on wellness between supervisors and supervisees and, coinciding with Granello (2013) and Roach and Young (2007), stressed the idea that as a supervisor, wellness education can play a key role in promoting healthy helping professionals.

Discussion

The results from this study provided the data to answer the research question: What are clinical mental health supervisors’ experiences with their supervisees’ wellness? Experienced supervisors (e.g., 10 or more years of supervisory experience) discussed areas that influenced their wellness as well as their supervisees’ wellness. Furthermore, several themes that supported an essence of supervisee wellness (Hays & Wood, 2011; Moustakas, 1994) were derived. In interviewing the supervisors, the themes of (a) intentionality, (b) self-care, (c) humanness, (d) support and (e) wellness identity were derived from the data analysis. From the results of this study, implications for clinical supervisors and counselor educators, limitations of the research investigation, and areas for future research were derived.

Implications for Clinical Supervisors and Counselor Educators

The counseling field is grounded in holistic wellness (Myers & Sweeney, 2004). Therefore, our findings reflected the theme that wellness is important to the counseling profession and in supporting supervisors’ and supervisees’ overall growth. Scholars in the helping fields (Keyes, 2002, 2007; Myers, Sweeney, & Witmer, 2000) and professional guidelines (ACA, 2014; CACREP, 2015) support the necessity of a wellness focus, identifying that a lack of a wellness focus may lead to unwellness and burnout (Bakker, Demerouti, Taris, Schaufeli, & Schreurs, 2003). Thus, creating and maintaining a wellness identity in supervision can aid in supporting holistic wellness in supervisees. In addition, self-care can be important for counselors, as they are not immune to difficult experiences and life events faced by their clients (Venart et al., 2007). Supervisor #6 noted that burnout was an inevitable part of working as a counselor and, similarly, researchers have identified that burnout can influence counselors’ work with their clients (Lambie, 2007; Puig et al., 2012). Thus, wellness provides the foundation of helping professionals’ work with clients (Venart et al., 2007), and exploration of counselor burnout and other negative consequences of counselor unwellness warrants attention.

The clinical supervisors in our investigation indicated a need for counselor educators to be more intentional in their focus and inclusion of wellness with the therapeutic relationship. In order to mitigate the effects of burnout and unwellness in supervisees, a wellness course or a wellness plan for counselors-in-training over the duration of their preparation program is suggested to support counselor educators in preparing future clinicians with a mindset of reflection, process and activities to enhance wellness. By implementing a wellness focus throughout preparation programs, supervisees can learn about the positive and negative influence of their wellness choices, as well as the effects their wellness may have on their colleagues and clients. Furthermore, wellness plans could be implemented throughout the program to promote wellness awareness in supervisees. Classroom discussions and wellness groups could also aid in supporting students in their wellness growth and development throughout their program while providing counselors-in-training with the tools to share their knowledge and promote wellness in others.

Supervisors also can mitigate the effects of unwellness by continuously evaluating their current levels of functioning through formal assessments such as the Five Factor Wellness Inventory (5F-Wel; Myers & Sweeney, 2005a), or the Helping Professional Wellness Discrepancy Questionnaire (HWPDS; Blount & Lambie, in press) or informal assessments such as wellness journaling or implementing wellness plans. Supervisors also may choose to include wellness in their supervision sessions by assessing pre- and post-wellness levels in supervisees, operating from a wellness-supervision paradigm (e.g., the Integrative Wellness Model; Blount & Mullen, 2015; Wellness Model of Supervision; Lenz & Smith, 2010), having educational discussions on the holistic components of wellness, and modeling appropriate wellness behaviors. Thus, there are numerous actions supervisors can take to promote individual wellness, include wellness in their supervision, and promote wellness in their supervisees.

Supervision is crucial to counselor development (Bernard & Goodyear, 2014). CACREP (2015) Standards and licensure requirements emphasize the importance of supervision throughout trainees’ growth and establishment as a professional counselor. ACA (2014) emphasizes additional professional development and supervision throughout counselors’ careers, stating that counselors should “regularly pursue continuing education activities including both counseling and supervision topics and skills” (Standard F.2.a.). Even though the field of counseling is grounded in a wellness paradigm (ACA, 2014; CACREP, 2015), the process of supervision does not always support a wellness focus, as supervisors do not model wellness for their supervisees or stress the importance of counselor well-being. According to the supervisors in our investigation, wellness should be integrated and discussed within the supervision realm. Further, clients are more likely to benefit from a well counselor (Lawson, 2007) and as such, counselor educators and supervisors face the challenge of promoting effective, well therapists-in-training. The wellness process, however, typically occurs in a negative trickledown method (e.g., burned out supervisors modeling inappropriate wellness behavior for trainees who in return model inappropriate wellness for clients).

Counselor educators can break the cycle of negatively modeling wellness by incorporating wellness throughout the trainees’ experience in their preparation programs and by modeling wellness and self-care. Through the wellness paradigm, counselor educators can begin to change the thought process of trainees’ own reluctance to engage in self-care and work to change the “do as I say” mentality (i.e., telling clients or trainees to be well when we are not well ourselves), which is present throughout the helping professions (Lawson, 2007; Witmer & Young, 1996). Based on our results, the counseling profession should embrace the belief that “you cannot give away that which you do not possess” (Bratton et al., 2006; p. 238). By adapting a wellness framework, the benefits of the wellness paradigm at the beginning of trainees’ careers is significant, impacting other counselors and clients that enter into their path in a positive way.

Expanding beyond supervisors, therapists-in-training and practitioners, wellness practices can be influential on a larger scale. Counseling and counselor education programs, as well as respective professional organizations, can use wellness philosophies and practices to promote self-care in their members. In addition, organizations can support strong wellness identities in their helping professionals by upholding their ethical standards, promoting wellness-related actions, and educating new professionals on the importance of practicing wellness in their personal and professional lives. As voiced by many of the supervisors interviewed in our study, professional organizations can support their members by encouraging wellness identities and offering platforms for individuals to form relationships with other practitioners in the field. Practitioners can use the connections to exchange wellness ideas and practices, and offer support as professionals. Finally, supervisors can be integral in promoting their supervisees’ wellness throughout the career, supporting the services they provide to diverse clients.

Limitations

We followed steps to support the trustworthiness of the data; however, some limitations are noted. Given that the first author is invested in the wellness approach to counseling, researcher bias may have occurred. However, the research team implemented steps to mitigate the role of bias. For instance, researcher bias was bracketed at the forefront of the interviews and an external auditor reviewed interviews to note themes separate from the research team. As with all qualitative research, the results from our study are not generalizable. Nevertheless, the six clinical mental health supervisors worked in six different mental health agencies, supporting the transferability of the findings (Yardley, 2008). In addition, the sample size for the investigation met the criteria outlined for qualitative analyses (5–25 participants; Polkinghorne, 1989), yet all of the participants volunteered for participation and may have had a greater interest in wellness than those who did not volunteer. Finally, even with a small sample size (N = 6), the researchers believed that saturation of the themes occurred by implementing rigorous data analytic procedures (i.e., coding for themes and essence) and reaching an inability to glean new information from the coding (Guest, Bunce, & Johnson, 2006).

Areas for Future Research

In relation to future research endeavors, participants in this study emphasized the importance of wellness-related research in counseling. Given that the counseling field is grounded in a wellness model (Myers & Sweeney, 2005b; Witmer, 1985) and that limited studies on wellness are available, quantitative and/or qualitative studies examining the overall effect of wellness within the supervisory relationship are needed. Further, researchers might assess the degree to which supervisors or supervisees actually engage in wellness behaviors. As with most qualitative studies, our findings reflect a starting point for quantitative research, focusing on the identified themes across supervisors and supervisees. Future researchers could examine the parallel process between (a) educator and student and (b) supervisor and supervisee that takes place when trusting and safe relationships are established (Bernard & Goodyear, 2014). Furthermore, future researchers could assess differences in supervisors or supervision styles in supervisors with formal supervision courses versus no formal experience; or similar studies with supervisors who have participated in a wellness course versus those who have not. In addition, future research could focus on client outcomes when one party (i.e., counselor) models appropriate wellness and a different counselor does not model these qualities. Future researchers are also encouraged to assess the effect of the five identified themes on client outcomes and/or student progress within counselor education programs.

In summary, “it is not possible to give to others what you do not possess” (Corey, 2000, p. 29); therefore, we must take care of ourselves before we are fully capable to help others. As such, it is important to bring wellness to the forefront of clinical supervision and remain engaged in promoting personal wellness and the wellness of others. Thus, assessing and evaluating wellness in all supervisors and supervisees (counselors) is integral in providing quality supervision and efficacious counseling services and protecting client welfare. By increasing awareness on wellness themes, such as self-care, support, wellness identity, and humanness, along with operating intentionality, clinical supervisors can support their supervisees in achieving greater levels of wellness.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

American Counseling Association. (2014). 2014 ACA code of ethics. Alexandria, VA: Author.

American Psychological Association. (2010). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/ethics/code/index.aspx

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., Taris, T. W., Schaufeli, W. B., & Schreurs, P. J. G. (2003). A multigroup analysis of the Job Demands–Resources Model in four home care organizations. International Journal of Stress Management, 10, 16–38. doi:10.1037/1072-5245.10.1.16

Bernard, J. M., & Goodyear, R. K. (2014). Fundamentals of clinical supervision (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Blount, A. J., & Lambie, G. W. (in press). The helping professional wellness discrepancy scale: Development and validation. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development.

Blount, A. J., & Mullen, P. R. (2015). Development of the integrative wellness model: Supervising counselors-in-training. The Professional Counselor, 5, 100–113. doi:10.15241/ajb.5.1.100

Borders, L. D. (1993). Learning to think like a supervisor. The Clinical Supervisor, 10, 135–148.

doi:10.1300/J001v10n02_09

Bratton, S. C., Landreth, G. L., Kellam, T., & Blackard, S. R. (2006). Child-parent relationship therapy (CPRT) treat-ment manual: A 10-session filial therapy model for training parents. New York, NY: Routledge.

Corey, G. (2000). Theory and practice of group counseling (5th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/ Thompson Learning.

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2015). CACREP 2016 standards. Retrieved from http://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/2016-CACREP-Standards.pdf

Creswell, J. W. (2013a). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J. W. (2013b). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cummins, P. N., Massey, L., & Jones, A. (2007). Keeping ourselves well: Strategies for promoting and main-taining counselor wellness. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 46, 35–49.

doi:10.1002/j.2161-1939.2007.tb00024.x

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). The Sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Granello, P. F. (2013). Wellness counseling. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data satur-ation and variability. Field Methods, 18, 59–82. doi:10.1177/1525822X05279903

Hays, D. G., & Wood, C. (2011). Infusing qualitative traditions in counseling research designs. Journal of Coun-seling & Development, 89, 288–295. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2011.tb00091.x

Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43, 207–222.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2007). Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: A complementary strategy for improving national mental health. American Psychologist, 62(2), 95–108. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.62.2.95

Kottler, J. A. (2010). On being a therapist (4th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Kottler, J. A., & Hazler, R. J. (1996). Impaired counselors: The dark side brought into light. The Journal of Human-istic Counseling, 34(3), 98–107. doi:10.1002/j.2164-4683.1996.tb00334.x

Lambie, G. W. (2006). Burnout prevention: A humanistic perspective and structured group supervision activity. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 45, 32–44. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1939.2006.tb00003.x

Lambie, G. W. (2007). The contribution of ego development level to burnout in school counselors: Implica-

tions for professional school counseling. Journal of Counseling & Development, 85, 82–88. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2007.tb00447.x

Lambie, G. W., & Blount, A. J. (2016). Tailoring supervision to the supervisee’s developmental level. In K.

Jordan (Ed.), Couple, marriage and family therapy supervision (pp. 71–86). New York, NY: Spring Publishing.

Lawson, G. (2007). Counselor wellness and impairment: A national survey. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 46, 20–34. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1939.2007.tb00023.x

Lawson, G., & Myers, J. E. (2011). Wellness, professional quality of life, and career-sustaining behaviors: What keeps us well? Journal of Counseling & Development, 89, 163–171. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2011.tb00074.x

Lawson, G., Venart, E., Hazler, R. J., & Kottler, J. A. (2007). Toward a culture of counselor wellness. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 46, 5–19. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1939.2007.tb00022.x

Lee, S. M., Cho, S. H., Kissinger, D., & Ogle, N. T. (2010). A typology of burnout in professional counselors. Journal of Counseling & Development, 88, 131–138. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00001.x

Lenz, A. S., Sangganjanavanich, V. F., Balkin, R. S., Oliver, M., & Smith, R. L. (2012). Wellness model of super-vision: A comparative analysis. Counselor Education and Supervision, 51, 207–221.

doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2012.00015.x

Lenz, A. S., & Smith, R. L. (2010). Integrating wellness concepts within a clinical supervision model. The Clinical Supervisor, 29, 228–245. doi:10.1080/07325223.2010.518511

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Myers, J. E., Mobley, A. K., & Booth, C. S. (2003). Wellness of counseling students: Practicing what we preach. Counselor Education and Supervision, 42, 264–274. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2003.tb01818.x

Myers, J. E., & Sweeney, T. J. (2004). The indivisible self: An evidence-based model of wellness. (Reprint.). The Journal of Individual Psychology, 61, 269–279.

Myers, J. E., & Sweeney, T. J. (2005a). The five factor wellness inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Mindgarden.

Myers, J. E., & Sweeney, T. J. (Eds.). (2005b). Counseling for wellness: Theory, research, and practice. Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Myers, J. E., & Sweeney, T. J. (2008). Wellness counseling: The evidence base for practice. Journal of Counseling & Development, 86, 482–493. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2008.tb00536.x

Myers, J. E., Sweeney, T. J., & Witmer, J. M. (2000). The Wheel of Wellness counseling for wellness: A holistic

model for treatment planning. Journal of Counseling & Development, 78, 251–266.

doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2000.tb01906.x

National Association of Social Workers. (2008). Code of ethics of the National Association of Social Workers. Wash-ington, DC: Author. https://www.socialworkers.org/pubs/code/code.asp

O’Halloran, T. M., & Linton, J. M. (2000). Stress on the job: Self-care resources for counselors. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 22, 354–364.

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Perkins, E. B., & Sprang, G. (2012). Results from the Pro-QOL-IV for substance abuse counselors working with offenders. International Journal of Mental Health Addiction, 11, 199–213. doi:10.1007/s11469-012-9412-3

Polkinghorne, D. E. (1989). Phenomenological research methods. In R. S. Valle & S. Halling (Eds.), Existential-phenomenological perspectives in psychology (pp. 41–60). New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Puig, A., Baggs, A., Mixon, K., Park, Y. M., Kim, B. Y., & Lee, S. M. (2012). Relationship between job burnout and personal wellness in mental health professionals. Journal of Employment Counseling, 49, 98–109. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1920.2012.00010.x

Roach, L. F., & Young, M. E. (2007). Do counselor education programs promote wellness in their students? Counselor Education & Supervision, 47, 29–45. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2007.tb00036.x

Rogers, C. R. (1961). On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin.

Sadler-Gerhardt, C. J., & Stevenson, D. L. (2011). When it all hits the fan: Helping counselors build resilience and avoid burnout. Ideas and Research You Can Use: VISTAS 2012, 1, 1–8. https://www.counseling.org/resources/library/vistas/vistas12/Article_24.pdf

Skovholt, T. M. (2001). The resilient practitioner: Burnout prevention and self-care strategies for counselors, therapists, teachers, and health professionals. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Smith, H. L., Robinson, E. H. M., III, & Young, M. E. (2007). The relationship among wellness, psychological distress, and social desirability of entering master’s-level counselor trainees. Counselor Education and Supervision, 47, 96–109. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2007.tb00041.x

Storlie, C. A., & Smith, C. K. (2012). The effects of a wellness intervention in supervision. The Clinical Supervisor, 31, 228–239. doi:10.1080/07325223.2013.732504

Swank, J. M., Lambie, G. W., & Witta, E. L. (2012). An exploratory investigation of the Counseling Competen-cies Scale: A measure of counseling skills, dispositions, and behaviors. Counselor Education and Super-vision, 51, 189–206. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2012.00014.x

Trippany, R. L., White Kress, V. E., & Wilcoxon, S. A. (2004). Preventing vicarious trauma: What counselors should know when working with trauma survivors. Journal of Counseling & Development, 82, 31–37. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2004.tb00283.x

Venart, E., Vassos, S., & Pitcher-Heft, H. (2007). What individual counselors can do to sustain wellness. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 46, 50–65. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1939.2007.tb00025.x

Wester, K. L., Trepal, H. C., & Myers, J. E. (2009). Wellness of counselor educators: An initial look. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 48, 91–109. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1939.2009.tb00070.x

Witmer, J. M. (1985). Pathways to personal growth. Muncie, IN: Accelerated Development.

Witmer, J. M., & Young, M. E. (1996). Preventing counselor impairment: A wellness approach. Journal of Human-istic Counseling, 34, 141–155. doi:10.1002/j.2164-4683.1996.tb00338.x

Yardley, L. (2008). Demonstrating validity in qualitative psychology. In J. A. Smith (Ed.), Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (pp. 235–251). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ashley J. Blount, NCC, is an Assistant Professor at the University of Nebraska Omaha. Dalena Dillman Taylor is an Assistant Professor at the University of Central Florida. Glenn W. Lambie, NCC, is a Professor at the University of Central Florida. Arami Nika Anwell is a recent graduate of the University of Central Florida. Correspondence can be addressed to Ashley Blount, 6001 Dodge Street, RH 101E, Omaha, NE 68182, ablount@unomaha.edu.

Sep 16, 2016 | Article, Volume 6 - Issue 3

Christopher A. Sink and Melissa S. Ockerman

Designed to improve preK–12 student academic and behavioral outcomes, a Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS), such as Positive Behavioral Intervention and Supports (PBIS) or Response to Intervention (RTI), is a broadly applied framework being implemented in countless schools across the United States. Such educational restructuring and system changes require school counselors to adjust their activities and interventions to fully realize the aims of MTSS. In this special issue of The Professional Counselor, the roles and functions of school counselors in MTSS frameworks are examined from various angles. This introductory article summarizes the key issues and the basic themes explored by the special issue contributors.

Keywords: school counselors, multi-tiered system of supports, Positive Behavioral Intervention and Supports, Response to Intervention, implementation

School counselors must proactively adapt to the varied mandates of school reform and educational innovations. Similarly, with new federal and state legislation, they must align their roles and functions in accordance with their changing requirements (Baker & Gerler, 2008; Dahir, 2004; Gysbers, 2001; Herr, 2002; Leuwerke, Walker & Shi, 2009; Paisley & Borders, 1995). One such initiative, the Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS), requires educators to revise their assessment strategies, curriculum, pedagogy and interventions to best serve the academic, behavioral, and post-secondary education and career goals of all students (Lewis, Mitchell, Bruntmeyer, & Sugai, 2016). Specifically, MTSS is an umbrella term for a variety of school-wide approaches to improve student learning and behavior. The most familiar MTSS frameworks are Response to Intervention (RTI) and Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS; also referred to as Culturally Responsive or CR PBIS). The latter model has been implemented throughout the U.S., spanning all 50 states and approximately 22,000 schools (H. Choi, personal communication, December 15, 2014). Moreover, 45 states have issued guidelines for RTI implementation and 17 states require RTI to be used in the identification of students with specific learning disabilities (Hauerwas, Brown, & Scott, 2013). Research indicates that when these frameworks are implemented with fidelity over several years, they are best practice for addressing students at risk for academic or behavioral problems (Lane, Menzies, Ennis, & Bezdek, 2013; Lewis et al., 2016).

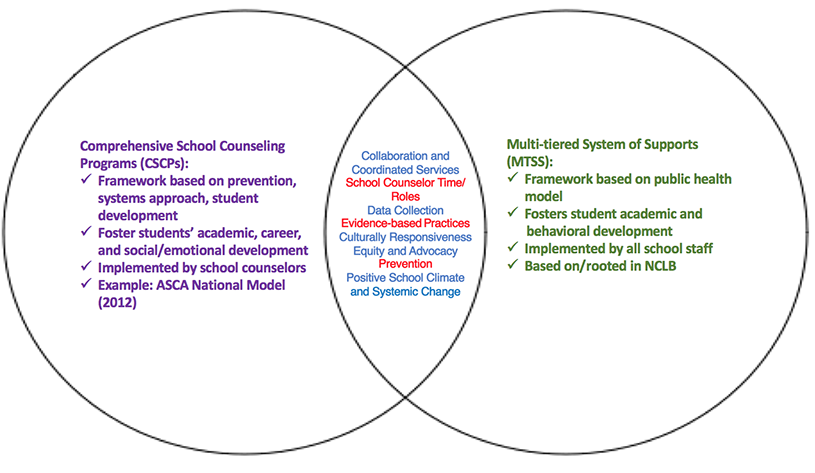

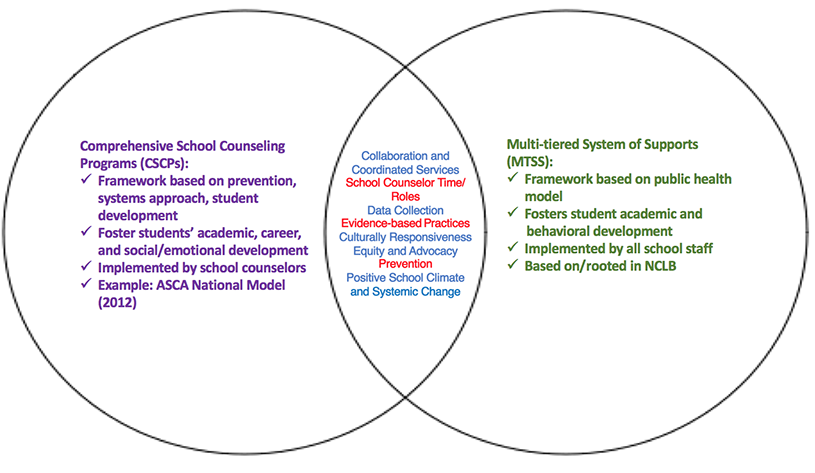

In 2014, the American School Counselor Association (ASCA) revised its RTI position statement to encompass MTSS, including both RTI and CR PBIS (ASCA, 2014). Although there is little evidence to support this assumption, the writers averred that MTSS seamlessly aligns with the ASCA National Model (2012a) in the three developmental domains (academic, social-emotional, and college/career). Nevertheless, school counselors should view MTSS frameworks as an opportunity to enhance their school counseling programs through the implementation of a data-driven, multi-tiered intervention system. Doing so allows school counselors to utilize and showcase their leadership skills with key stakeholders (e.g., parents, caregivers, teachers, administrators) and to create systemic changes in their schools and thus foster equitable outcomes for all children.

The implementation of MTSS and its alignment with comprehensive school counseling programs (CSCPs) position school counselors to advance culturally responsive preventions and interventions to serve students and their families more effectively (Goodman-Scott, Betters-Bubon, & Donohue, 2016). By working collaboratively with school personnel to tap students’ strengths and create common goals, school counselors can build capacity and thereby broaden their scope of practice and accountability. Politically astute school counselors are wise to leverage their school’s MTSS framework as a way to access necessary resources, obtain additional training and further impact student outcomes.

The research is scant on school counselor involvement with—and effectiveness in—MTSS implementation. The available publications, including those presented in this special issue, suggest that the level of MTSS education and training for pre-service and in-service school counselors is insufficient (Cressey, Whitcomb, McGilvray-Rivet, Morrison, & Shandler-Reynolds, 2014; Goodman-Scott, 2013, 2015; Goodman-Scott, Doyle, & Brott, 2014; Ockerman, Mason, & Hollenbeck, 2012; Ockerman, Patrikakou, & Feiker Hollenbeck, 2015). There are legitimate reasons for counselor reluctance and apprehension. For example, not only must school counselors add new and perhaps unfamiliar duties to an already harried work day, some evidence indicates that they are not well prepared for their MTSS responsibilities. Consequently, it is essential for both in-service professional development opportunities and pre-service preparation programs to focus on best practices for aligning CSCPs with MTSS frameworks (Goodman-Scott et al., 2016).

To address the gaps in the counseling literature on successful school counselor MTSS training, implementation, and collaboration with other school personnel, this special issue of The Professional Counselor was conceived. Moreover, the articles consider various facets of MTSS and their intersection with school counseling research and practice. Overall, the contributors hope to provide much needed MTSS assistance and support to nascent and practicing school counselors.

Summary of Contributions

Sink’s lead article in this special issue situates the contributions that follow by offering a general overview of foundational MTSS theory and research, including PBIS and RTI frameworks. Subsequently, literature-based suggestions for incorporating MTSS into school counselor preparation curriculum and pedagogy are provided. MTSS roles and functions summarized in previous research are aligned to ASCA’s (2012b) School Counselor Competencies, the 2016 Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) Standards for School Counselors (2016) and the ASCA (2012a) National Model.

The next two articles report on MTSS-related studies and specifically discuss new school counselor responsibilities associated with MTSS implementation. Ziomek-Daigle, Goodman-Scott, Cavin, and Donohue reveal through a case study the various ways MTSS and CSCPs reflect comparable features (e.g., school counselor roles, advocacy, accountability). The participating case study counselors were actively engaged in MTSS implementation at their school, suggesting that they had a relatively good idea of their responsibilities in this capacity. Addressing RTI in particular, Patrikakou, Ockerman, and Hollenbeck’s investigation reported that while most school counselors expressed positive opinions about this MTSS framework, they lacked the self-assurance to adequately perform key RTI tasks (e.g., accountability and collaboration). Perceived counselor deficiencies in RTI implementation also point to a potential disconnect between the ASCA (2012a) National Model’s program components and themes and current RTI training of pre-service and practicing school counselors, thus suggesting a need for improved pre-service and in-service education.

School counselors are called upon to be culturally responsive and competent. They are advocates for social justice and equity for all students (Ratts, Singh, Nassar-McMillan, Butler, & McCullough, 2016; Singh, Urbano, Haston, & McMahan, 2010). Two articles speak to this issue within the educational context of MTSS. Belser and colleagues maintain that the ASCA (2012a) National Model and MTSS are beneficial operational frameworks to support all students, including marginalized and so-called problem learners (e.g., at-risk students). An integrated model is then proffered as a way to improve the educational outcomes of disadvantaged students. Positive and culturally sensitive alternatives to punishment-oriented school discipline methods are discussed as well. Similarly, Betters-Bubon, Brunner, and Kansteiner address school counselor roles in devising and sustaining culturally responsive PBIS programs that meet student social, behavioral and emotional needs. In particular, they report on an action research case study showing how an elementary school counselor partnered with other stakeholders (i.e., school administrator, psychologist, teachers) to achieve this goal.

The final article by Harrington, Griffith, Gray, and Greenspan overviews a recent grant project intended to establish a quality data-driven MTSS model in an elementary school. The manuscript spotlights the role of the school counselor who collaborated with other project leaders and educators to use social-emotional data to inform and improve practice. Specifics are provided so other practitioners can replicate the project in their schools. In brief, this contribution emphasizes the importance of data-based decision-making in MTSS implementation.

Conclusion

School counselors are faced with a myriad of responsibilities that severely tax their energy and time. Competing demands from internal and external stakeholders as well as legislative changes and educational innovations stretch these practitioners to be more efficient and effective in their services to students and families. Regrettably, MTSS implementation adds to counselors’ “accountability stress.” Some counselors anticipate that PBIS and RTI frameworks will go the way of other short-lived educational trends, relieving them of the responsibility to take action. However, anecdotal and empirical evidence reported in this special issue and elsewhere suggests these professionals are in the minority. School counselors largely perceive the potential and real value of MTSS programs. They desire to partner with other school educators to help all children and youth succeed. As contributors to this issue indicate, the ASCA (2012a) National Model and PBIS and RTI frameworks can be integrated to achieve higher student academic and social-emotional outcomes. With these articles, school counselors-in-training and practitioners have additional support to successfully address their MTSS duties and advocate for increased education in this area. Continued research is needed to guide efficacious MTSS practice designed to foster equitable educational outcomes for all students.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

American School Counselor Association. (2012a). The ASCA national model: A framework for school counseling programs (3rd ed.). Alexandria, VA: Author.

American School Counselor Association. (2012b). ASCA school counselor competencies. Retrieved from https://www.schoolcounselor.org/asca/media/asca/home/SCCompetencies.pdf

American School Counselor Association. (2014). Position statement: Multi-tiered systems of support. Alexandria, VA: Author. Retrieved from https://www.schoolcounselor.org/asca/media/asca/PositionStatements/PS_MultitieredSupportSystem.pdf

Baker, S. B., & Gerler, E. R., Jr. (2008). School counseling in the twenty-first century (5th ed.). Columbus, OH: Merrill Prentice Hall.

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2016). 2016 CACREP standards. Retrieved from http://www.cacrep.org/for-programs/2016-cacrep-standards

Cressey, J. M., Whitcomb, S. A., McGilvray-Rivet, S. J., Morrison, R. J., & Shander-Reynolds, K. J. (2014). Handling PBIS with care: Scaling up to school-wide implementation. Professional School Counseling, 18, 90–99. doi:10.5330/prsc.18.1.g1307kql2457q668

Dahir, C. A. (2004). Supporting a nation of learners: The role of school counseling in educational reform. Journal of Counseling & Development, 82, 344–353. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2004.tb00320.x

Goodman-Scott, E. (2013). Maximizing school counselors’ efforts by implementing school-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports: A case study from the field. Professional School Counseling, 17, 111–119.

Goodman-Scott, E. (2015). School counselors’ perceptions of their academic preparedness and job activities. Counselor Education and Supervision, 54, 57–67.

Goodman-Scott, E., Betters-Bubon, J., & Donohue, P. (2016). Aligning comprehensive school counseling programs and positive behavioral interventions and supports to maximize school counselors’ efforts. Professional School Counseling, 19, 57–67.

Goodman-Scott, E., Doyle, B., & Brott, P. (2014). An action research project to determine the utility of bully prevention in positive behavior support for elementary school bullying prevention. Professional School Counseling, 17, 120–129

Gysbers, N. C. (2001). School guidance and counseling in the 21st century: Remember the past into the future. Professional School Counseling, 5(2), 96–105.

Hauerwas, L. B., Brown, R., & Scott, A. N. (2013). Specific learning disability and response to intervention: State-level guidance. Exceptional Children, 80, 101–120. doi:10.1177/001440291308000105

Herr, E. L. (2002). School reform and perspectives on the role of school counselors: A century of proposals for change. Professional School Counseling, 5, 220–234.

Lane, K. L., Menzies, H. M., Ennis, R. P., & Bezdek, J. (2013). School-wide systems to promote positive behaviors and facilitate instruction. Journal of Curriculum and Instruction, 7, 6–31.

doi:10.3776/joci.2013.v7n1pp6-31

Leuwerke, W. C., Walker, J., & Shi, Q. (2009). Informing principals: The impact of different types of information on principals’ perceptions of professional school counselors. Professional School Counseling, 12, 263–271. doi:10.5330/PSC.n.2010-12.263

Lewis, T. J., Mitchell, B. S., Bruntmeyer, D. T., & Sugai, G. (2016). School-wide positive behavior support and response to intervention: System similarities, distinctions, and research to date at the universal level of support. In S. R. Jimerson, M. K. Burns, & A. M. VanDerHeyden (Eds.), Handbook of response to intervention: The science and practice of multi-tiered systems of support (2nd ed.; pp. 703–717). New York, NY: Springer.

Ockerman, M. S., Mason, E. C. M., & Hollenbeck, A. F. (2012). Integrating RTI with school counseling programs: Being a proactive professional school counselor. Journal of School Counseling, 10(15), 1–37. Retrieved from http://jsc.montana.edu/articles/v10n15.pdf

Ockerman, M. S., Patrikakou, E., & Feiker Hollenbeck, A. (2015). Preparation of school counselors and response to intervention: A profession at the crossroads. The Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 7, 161–184. doi:10.7729/73.1106

Paisley, P. O., & Borders, L. D. (1995). School counseling: An evolving specialty. Journal of Counseling and Development, 74, 150–153. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232543894_School_Counseling_An_Evolving_Specialty

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar-McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2016). Multicultural and social justice counseling competencies: Guidelines for the counseling profession. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 44, 28–48. doi:10.1002/jmcd.12035

Singh, A. A., Urbano, A., Haston, M., & McMahan, E. (2010). School counselors’ strategies for social justice change: A grounded theory of what works in the real world. Professional School Counseling, 13(3), 135–145.

Christopher A. Sink, NCC, is a Professor and Batten Chair of Counseling at Old Dominion University and can be reached at Darden College of Education, Norfolk, VA 23508, csink@odu.edu. Melissa S. Ockerman is an Associate Professor in the Counseling Program at DePaul University and can be reached at College of Education, Chicago, IL 60614, melissa.ockerman@depaul.edu.

Sep 16, 2016 | Article, Volume 6 - Issue 3

Christopher A. Sink

With the advent of a multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) in schools, counselor preparation programs are once again challenged to further extend the education and training of pre-service and in-service school counselors. To introduce and contextualize this special issue, an MTSS’s intent and foci, as well as its theoretical and research underpinnings, are elucidated. Next, this article aligns MTSS with current professional school counselor standards of the American School Counselor Association’s (ASCA) School Counselor Competencies, the 2016 Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) Standards for School Counselors and the ASCA National Model. Using Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) and Response to Intervention (RTI) models as exemplars, recommendations for integrating MTSS into school counselor preparation curriculum and pedagogy are discussed.

Keywords:multi-tiered system of supports, school counselor, counselor education, American School Counselor Association, Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, Response to Intervention

When new educational models are introduced into the school system that affect school counseling practice, the training of pre-service and in-service school counselors needs to be updated. A multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) is one such innovation requiring school counselors to further refine their skill set. In fact, during the school counseling profession’s relatively short history, counselors have experienced several major shifts in foci and best practices (Gysbers & Henderson, 2012). The latest movement surfaced in the 1980s, when school counselors were encouraged to revisit their largely reactive, inefficient and ineffective practices. Specifically, rather than supporting a relatively small proportion of students with their vocational, educational and personal-social goals and concerns, pre-service and in-school practitioners, under the aegis of a comprehensive school counseling program (CSCP) orientation, were called to operate in a more proactive and preventative fashion.

Although there are complementary frameworks to choose from, the American School Counselor Association’s (ASCA; 2012a) National Model: A Framework for School Counseling Programs emerged as the standard for professional practice, offering K–12 counselors an operational scaffold to guide their activities, interventions and services. Preliminary survey research suggests that counselors are performing their duties in a more systemic and collaborative fashion to more effectively serve students and their families (Goodman-Scott, 2013, 2015). Other rigorous accountability research examining the efficacy of CSCP practices supports this transformation of counselors’ roles and functions (Martin & Carey, 2014; Sink, Cooney, & Adkins, in press; Wilkerson, Pérusse, & Hughes, 2013). As a consequence of the increased demand for retraining, university-level counselor preparation programs and professional counseling organizations (e.g., American Counseling Association, ASCA, National Board for Certified Counselors) have generally responded in kind. Over the last few decades, K–12 school counselors have been instructed to move from a positional approach to their professional work to one that is programmatic and systemic in nature.

As mentioned above, the implementation of MTSS (e.g., Positive Behavioral Supports and Responses [PBIS] and Response to Intervention [RTI] frameworks) in the nation’s schools requires in-service counselors to augment their collaboration and coordination skills (Shepard, Shahidullah, & Carlson, 2013). Essentially, MTSS programs are evidence-based, holistic, and systemic approaches to improve student learning and social-emotional-behavioral functioning. They are largely implemented in educational settings using three tiers or levels of intervention. In theory, all educators are involved at differing levels of intensity. For example, classroom teachers and teacher aides are the first line (Tier 1) of support for struggling students. As the need might arise, other more “specialized” staff (e.g., school psychologists, special education teachers, school counselors, addictions counselors) may be enlisted to provide additional and more targeted student interventions and support (Tiers 2 or 3). Even though ASCA (2014) released a position statement broadly addressing school counselors’ roles and functions within MTSS schools, research is equivocal as to whether these practitioners are implementing these directives with any depth and fidelity (Goodman-Scott, 2015; Goodman-Scott, Betters-Bubon, & Donahue, 2016; Ockerman, Mason, & Hollenbeck, 2012; Ockerman, Patrikakou, & Feiker Hollenbeck, 2015). Moreover, school counselor effectiveness with MTSS-related responsibilities is an open question.