Jun 27, 2022 | Book Reviews

by Beatriz Sheldon and Albert Sheldon

by Beatriz Sheldon and Albert Sheldon

Beatriz Sheldon, MEd, and her partner, Albert Sheldon, MD, describe their novel therapeutic approach, Complex Integration of Multiple Brain Systems (CIMBS), in this new publication. Throughout the book, references are made to the Sheldons’s 20 years of working together, 15 years of clinical experience, and 10 years of training other practitioners in CIMBS therapy. The authors emphasize that they “are practical, empirical therapists” (p. xvii). The book is seeded with references to scientists who inspire the duo, especially Daniel J. Siegel, Joseph LeDoux, Antonio Domasio, and the late Jaak Panksepp. It must be noted that CIMBS therapy as laid out in this text contains no peer-reviewed qualitative or quantitative studies; instead, the authors utilize vignettes to discuss their methods.

The brain systems referred to in CIMBS are organized into sections much like those of the triune brain model, with an additional peripheral system in the heart, lungs, and intestines. What the triune brain model labels the lizard brain relates to the primary level, the mammal brain is the secondary level, and the human brain is the tertiary level. The Sheldons assign awareness, attention, authority, autonomy, and agency (the “A Team”) to the conscious tertiary level. The secondary level holds nonconscious, inhibitory systems of fear, grief, shame, and guilt. The primary level, also nonconscious, contains the systems of safe, care, connection, sensory, assertive, play, and seeking.

The patient accesses the hidden strengths of the nonconscious mind via the CIMBS therapist’s use of techniques like Transpiring Present Moment, Go the Other Way, and Initial Directed Activation. Transpiring Present Moment is reminiscent of Fritz Perls’s emphasis on the “here-and-now.” Go the Other Way asks the patient to avoid getting bogged down in traumatic memories and instead reach for personal strengths. The CIMBS therapist cultivates the therapeutic alliance using the Therapeutic Attachment Relationship, which includes physical postures that suggest safety, reminding us of Egan’s SOLER stance taught in many counseling programs. This intervention also recommends intense focus on the patient’s micro-expressions as a guide to their conscious and nonconscious processes. Ultimately, the patient will integrate all 20 brain systems effectively and reach Fail-Safe Complex Network, a new, durable neural structure generating improved mental health.

Although the authors refer several times to the text’s internal contradictions or incongruence, the writing has the same appeal as the work of the Sheldons’s mentor, Dan Siegel, who wrote the Foreword. The book asks readers to lean on their intuition, often reminding them to “trust the process.” Nicola Swaine has provided line drawings to clarify central concepts, much as Siegel uses a curled fist to describe the triune brain. The authors relate that this text was written expressly to provide an overview of the Sheldons’s 16-part CIMBS training series (recorded and live) for students and trainees, who will find the glossary and bibliography especially useful.

In the Foreword, Siegel refers to the “cross-disciplinary framework known as interpersonal neurobiology . . . [using] universal principles discovered by independent pursuits of knowledge” (p xii). It would be useful to know which principles are considered universal in this book. Psychology sits forever on the fence between hard and soft science; some declarations of fact are based on microscopic studies of physical structures, and some are useful models that are at least partly philosophical. This text contains both. Neurologists have observed neural repairs and rerouting; thus, neuroplasticity is a demonstrable fact. The Sheldons describe 20 brain systems while noting that “one could certainly make the case for more or fewer systems” (p. 26). Clearly the number and definition of these brain systems can be thought of as helpful metaphors, a bit like Marsha Linehan describes a “wise mind” that is not a physical structure existing in the brain.

Professional counselors who like eclectic methods and enjoy pulling inspiration from many sources will appreciate CIMBS and this flagship text. The authors caution practitioners not to use CIMBS for patients who struggle with borderline personality disorder or dissociative, bipolar, or psychotic disorders. Although the Sheldons encourage clinicians to practice with their highest-functioning patients, the wise professional counselor will first disclose methods and procedures to patients.

Sheldon, B., & Sheldon, A. (2021). Complex integration of multiple brain systems in therapy. W. W. Norton.

Reviewed by: Christine Sheppard, MA, LCPC, NCC

The Professional Counselor

http://tpcjournal.nbcc.org

Dec 10, 2021 | Book Reviews

by Andrew Christensen, Brian D. Doss, and Neil S. Jacobson

Any counselor working with individual clients should also develop competence for working with couples. Because we have instinctual needs to love and be loved, relationship issues are not foreign to the dialogue counselors have with patients in individual therapy sessions. Even when individual treatment plans do not delineate clear objectives for improving a relationship, counselors often explore solutions for relationship issues with their individual clients. So, why not look for those solutions in the work of three esteemed mental health experts with over 40 years of research and clinical practice in couples therapy?

The book Integrative Behavioral Couple Therapy: A Therapist’s Guide to Creating Acceptance and Change by Andrew Christensen, Brian D. Doss, and Neil S. Jacobson, includes a description of theoretical principles of Integrative Behavioral Couple Therapy (IBCT) along with differences and similarities to other evidence-based treatments. The authors’ description is supported by evidence of the efficacy of IBCT and the application thereof. IBCT is a contingency-shaped application rather than rule-governed. Christensen, Doss, and Jacobson encourage clinicians to use their best judgment when applying IBCT principles. For clinicians working under any capacity of experience, the IBCT concepts are thoroughly explained for the advanced practitioner and the intern therapist or practicum student.

Introduced in the book are two core concepts that promote acceptance and change: empathic joining and unified detachment. Empathic joining facilitates acceptance by kindling compassion and empathy. This leads to forgiveness and support from both individuals of a couple. This is described strategically through observing couple interacting patterns with intention to shift partners away from dissecting actions of the other and toward looking at their own reactions and feelings. Then, using empathic listening skills, IBCT therapists sensitively summarize “hard” and “hidden” emotions to the couple. With unified detachment, partners reduce negative affect by engaging in discussion in the sessions, and then thereafter, about salient incidents and issues in a nonjudgmental way. This kind of dyadic mindfulness allows for a safe, non-blaming analysis of problematic communication and behavior between a couple. IBCT happens in phases, but the core concepts are drawn upon through the entire course of IBCT therapy.

Phases include Evaluation and Assessment—joint session then individual sessions for formulating a DEEP analysis (Differences, Emotional sensitivities, External stressors, and Pattern of communication); Feedback session—conceptualizing problems and description of the intervention; and Intervention sessions. Interventions are both acceptance-focused and change-focused and executed by employing empathic joining and unified detachment, tolerance building, dyadic behavioral activation, and communication and problem-solving training.

Limitations for the IBCT guidebook and the counselor using the principles are that although the knowledge of the theories explained in this work are clearly presented, they still require training, consultation, and supervision to administer. The book includes many case examples of real issues (patient names have been changed to protect identities) presented in real IBCT therapy sessions (some with session videos on the American Psychological Association’s video library website). The case examples cover a rainbow of issues (including clinical consideration for diversity, violence, sexual problems, infidelity, and psychopathology); however, they do not replace the valued learning experience from working with a certified IBCT trainer (which the authors imply). Certified IBCT training involves “extensive observation” of actual sessions. More information is available at https://ibct.psych.ucla.edu/, another online tool that has a chapter devoted to IBCT in brief format using the OurRelationship program—an IBCT website intervention for distressed couples (OurRelationship.com).

Christensen, A., Doss, B. D., & Jacobson, N. S. (2020). Integrative behavioral couple therapy: A therapist’s guide to creating acceptance and change (2nd ed.). W. W. Norton.

Reviewed by: Evan P. Guetz, MA, LPC

The Professional Counselor

http://tpcjournal.nbcc.org

Nov 16, 2021 | Book Reviews

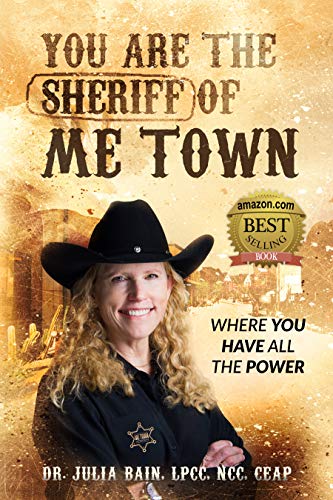

by Dr. Julia Bain, LPCC, NCC, CEAP

by Dr. Julia Bain, LPCC, NCC, CEAP

You Are the Sheriff of Me Town: Where You Have All the Power, by Dr. Julia Bain, is a book that explores the various aspects of our self-dialogue and self-image, especially areas that are sometimes overlooked. The author begins by introducing her metaphor that we are all the sheriffs of “Me Town,” and as a result, we have control over the choices and beliefs that run this town. The book progresses into the different aspects of our lives that we have control over and the ways that taking ownership of these areas can empower us. This involves diving into our beliefs, thoughts, values, and self-image.

A strength of this book is how the author breaks down and organizes the sections. When working with a multi-layered metaphor, readers can become overwhelmed with the different terms and ideas presented. Dr. Bain has sectioned the book in a way that introduces and explains topics while also moving the narrative toward more complex ideas.

Another strength of this book is the underlying philosophy driving its message. We are not static beings, and Dr. Bain reminds the reader that change is both possible and necessary to achieve our goals. In pursuit of these goals, Dr. Bain puts a strong emphasis on checking in with oneself.

I greatly enjoyed the resource section at the end of the book. The author uses a key phrase or idea for each letter of the alphabet and describes these ideas in a paragraph or two. These sections are condensed versions of topics discussed in the book and provide a brief summary of Dr. Bain’s points. I saw these sections as mini pep talks or even prompts for journal entries.

An area of improvement for this book would be a stronger recognition of external factors. Yes, we are in control of the choices we make, but oftentimes those choices are influenced by elements outside our control. Being able to separate the various motivators in our lives, whether internal or external, can be a powerful step toward change.

Fellow professionals may see this book as a good resource for clients who are hoping to improve their levels of self-esteem or confidence. Being able to identify different strengths and characteristics in our lives can be an empowering step toward change and growth.

I frequently utilize imagery and metaphors with my clients; I believe it helps build rapport and can help explain difficult or complex topics. I could see other professionals, myself included, using the idea of being “the sheriff of Me Town” as a way to empower clients to take charge of their lives.

Overall, I enjoyed the book, and I could see its usefulness in and out of the counseling session. It breaks down aspects of our identify and helps the reader find ways of nurturing these areas. Although a good starting point, I would encourage readers to use this book as a springboard to dive into deeper areas of reflection and study.

Bain, J. (2021). You are the sheriff of Me Town: Where you have all the power. Walton Publishing House.

Reviewed by: Amanda Condic, MA, NCC, LPC

The Professional Counselor

http://tpcjournal.nbcc.org

Aug 11, 2021 | Book Reviews

by Mark Treanor

Winner of the 2021 William E. Colby Military Writer’s Award, Mark Treanor’s first novel, A Quiet Cadence, deftly illustrates the interlacing dichotomies of humanity, both the compassion and malevolence, when hurtled into war and the deeply entrenched wounds that remain long after. Treanor depicts a brutally honest portrayal of the war in Vietnam from the perspective of 19-year-old Marty McClure. Touting a negligible amount of college credits and a hurried enthusiasm to do his part, McClure enlists in the Marine Corps. Treanor’s novel chronicles McClure’s tenebrific descent into darkness during the months he spends in the bush with his platoon and the seemingly insurmountable challenge of returning to the world afterward.

Throughout Treanor’s novel, he outlines several poignant and salient issues on military trauma during and after the war. Treanor’s characters discuss the courage necessary not just to be physically courageous in battle but to have the fortitude and valor necessary to make difficult decisions. As McClure and his fellow Marines begin their descent, Treanor is exacting in his depiction of the brutality these men are capable of in how they view the Vietnamese and their inability to distinguish civilians from the enemy. As McClure’s friends are injured and killed, the necessity of compartmentalization becomes clear, “Bad things went in boxes, some of which never got opened again until after we were back in the World.” In addition to boxing up his trauma, McClure begins to question his faith, wondering how God can do nothing as his world burns. He further questions his sacrifice, feeling as if he is not worthy of recognition or commendation, as his sacrifice pales to those made by others. While this maelstrom of conflicts rages on, the seemingly elusive and irrelevant concept of a world outside of the war comes into focus, elucidated by both a complex and innocuous question: “How are you doing?” As McClure returns to the world, Treanor illuminates the hardships of reintegration and the inconvenient truth of how Vietnam veterans were treated by their countrymen once on native soil.

Treanor’s depictions of the war in Vietnam are both vivid and gruesome, undoubtedly bolstered by his own experience in the Vietnam War. Readers familiar with the theater of war will undoubtedly recognize the nuanced descriptions, harkening them back to the sights, smells, and emotions tied to those memories. While the potential for triggering a reaction from the limbic system looms large for some readers, others may benefit from the knowledgeable insights offered by the author. Treanor paints a clear picture of a lived experience, providing a concise outline of expectations for those readers who may follow afterward. Admirably, Treanor conveys, in animated language, the importance of talking with others about their trauma and the benefit of seeking help sooner. As a Marine Corps veteran himself, conveying the advantages of seeking support is both significant and refreshing.

Regrettably, Treanor falls short of connecting with audiences who are not associated with the Marine Corps. The absence of footnotes becomes a significant hurdle for non–Marine Corps readers. The abundance of military jargon, acronyms, and abbreviations soon alienates readers, requiring them to discern meaning from contextual clues, which even then can be difficult to parse out. At times, the pacing of the novel while in Vietnam and afterward moves in a somewhat disjointed fashion where significant plot devices are stitched together without fluid transitions, making it difficult to become engrossed in the story. Not to detract from the book’s ending, it is poignant and powerful, and it will surely draw tears from even the most rigid, stoic individual.

To the counselors seeking ancillary texts to provide to their clients, A Quiet Cadence consistently conveys the value and long-term benefit of being open and emotionally vulnerable to others. Treanor delicately presents the real face of post-traumatic stress without the sensationalizing embellishments characteristic of Hollywood’s interpretations. This accurate portrayal makes tangible the elusive, unnamed emotions that so often inundate veterans returned from war. The value of Treanor’s descriptive meaning-making is enormous to those unconversant with the counseling profession, enabling them to find a foothold and contextualize their ever-abrupt torrent of emotions. Restraint, however, should be applied by counseling professionals working with clients not yet stable in treatment. The sometimes too elaborate depictions of carnage, enmeshed with language that stimulates a sensorial reaction, may provoke harmful manifestations. Alongside therapy and with an experienced counselor, this novel delivers the framework for a conversational agenda, potentially helping clients to identify subject matters to address during therapy they may have otherwise minimized or overlooked entirely.

Treanor, M. (2020). A quiet cadence: A novel. Naval Institute Press.

Reviewed by: Ashley E. Wadsworth, MS, NCC, LCMHC, LCAS-A

The Professional Counselor

http://tpcjournal.nbcc.org

Aug 11, 2021 | Book Reviews

by Daniel J. Siegel and Marion F. Solomon (Eds.)

Consciousness helps bring rise to equanimity and neural integration. Consciousness promotes well-being, resilience cultivation, and integrative neurological growth; raises telomerase levels for maintaining and repairing the ends of chromosomes; optimizes epigenetic regulators for decreasing inflammatory diseases; and improves physiological approaches to health care. The book Mind, Consciousness, and Well-Being (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology), edited by Daniel J. Siegel, MD, and Marion F. Solomon, PhD, is a symposium of the 2017 Interpersonal Neurobiology Conference presentations and embraces interdisciplinary perspectives. This in-depth scholarly, practical, and immersive collection explores the nature of the human mind, the experience of consciousness, and how our social brain influences our connections with others and with ourselves.

The book’s chapters consist of a collection of presentations offering an overview of current neuroscience research for the efficacy of mind–body integrative techniques in clinical psychotherapy. The presenters include counselors; psychiatrists; social workers; psychologists; marriage and family therapists; addiction specialists; mindfulness and Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) practitioners; crisis intervention counselors; educational and guidance professionals; and dance, movement, and somatic therapists.

What role might consciousness play in well-being? Interconnectedness and social integration are two considerations, according to this book, which is about understanding the different levels or aspects of our one reality. Topics introduced include the top-down model and the embodied brain, that is, the embodied mechanism of energy and information flow. This leads to self-organization within a complex system. Energy and information also give rise to subjective experience, consciousness, and processing of information. The system of energy and information exists between our own body and the rest of the world. According to the conclusive work herein, boundaries between inner and inter are illusions; culture is made up of constructs and perceptions. The top-down model explains the pathology of a self that is separate from others and the planet. As such, the mind is said to be located in a collective, in relation to others.

In the book’s last chapter, Dr. Daniel Siegel assimilates the lectures from the presenters, and he suggests applications with detailed models of delivery in the clinical environment. Dr. Siegel provides an exercise for mindfulness integration for readers to connect with others and the planet. Mindfulness, kindness, and compassion lift the veil of these illusions and allow us to embrace the importance of our differentiation—social justice and our linkage, or oneness. Seeing through the veil of illusion allows you to see yourself as separate from others, and once the veil is lifted, there is a we instead of me. Integration of me and we is called MWe, a word and movement introduced by Dr. Siegel. The flow of energy transforms our well-being—health and harmony flow from the integrated relationships with others and the planet, and when we bring inner compassion to this energy, we shape our quality of information and our embedded relationship to the world.

This book is appropriate for counselors interested in current findings in the scientific fields of mindfulness and compassion-based theoretical applications, therapeutic presence, quantum physics, neurology, and interpersonal neurobiology. The chapters offer evidence-based exercises, respective to the presenter’s discipline, for strengthening our awareness of interpersonal connectivity, or MWe. All of which are presented as applicable to the clinical practice of psychotherapy, including the empathy and receptive flexibility for delivering clinical services. Implications are suggested for social injustice, depressive disorders, trauma, and Alzheimer’s disease, among several other common conditions.

Siegel, D. J., & Solomon, M. F. (Eds.). (2020). Mind, consciousness, and well-being. W. W. Norton.

Reviewed by: Evan Guetz, MS, LAC

The Professional Counselor

http://tpcjournal.nbcc.org

Apr 9, 2021 | Book Reviews

by Kathy M. Evans and Aubrey L. Sejuit

Coursework and trainings in cultural competencies are often approached as an afterthought, a perspective used to enhance and improve existing practice. Counseling programs often include a course in multiculturalism and diversity focused on teaching theories of cultural and identity development, but this has a drawback: Students become responsible for integrating the course content into their intended area of practice. For career professionals, that can be a huge task—integrating counseling skills, career development theory, practical knowledge of vocations and employment law, cultural competencies, and social justice initiatives. Kathy Evans and Aubrey Sejuit’s second edition of Gaining Cultural Competence in Career Counseling is a valuable tool in this process; it seamlessly weaves together these categories to provide a thorough guide for the culturally competent career counselor.

The text is structured similarly to a typical multicultural counseling course. Chapters 1 through 4 discuss the importance of culturally competent career counseling, highlighting issues including the history of discrimination against marginalized groups in the workplace. Readers are introduced to concepts, such as worldview, locus of control and responsibility, and bias, and encouraged to explore their own biases and values. Each concept is framed from the perspective of career development, with examples and reflective activities emphasizing stereotypes or microaggressions related specifically to work- and workplace-related issues.

Chapters 5 through 7 delve into the application of cultural competencies in widely used career development theories and assessments. Evans and Sejuit examine classical career development theories (Parsons, Super, Holland) as well as newer theories to provide career professionals with guidance on how to reconcile those theories’ cultural shortcomings with ethical practice. Dimensions that are often measured in career assessments—interest, personality, and cognitive ability—are discussed, including the monochromatic landscape in which these assessments were developed. Evans and Sejuit then take the topic one step further, providing a framework for career professionals to administer and interpret assessments in a culturally informed manner.

Chapters 8 and 9 explore specific applications of cultural competencies, including in work with children and adolescents and social justice and advocacy. This is the text’s strongest section. Evans and Sejuit provide a multitude of evidence demonstrating how career information received in childhood and adolescence shapes adult career decisions, disproportionately affecting minority and low–socioeconomic status communities. Evans and Sejuit demonstrate that by simply engaging children and adolescents in an ethical and informed manner, practitioners are affecting outcomes. This is especially crucial information, as children and adolescents are often overlooked in the field of career counseling and development.

My only complaint is that Evans and Sejuit do not dive into more material in working with specific populations. The text is energizing and leaves the reader wanting to know more. However, this simplicity is also the text’s strength. At the core, the text is not only about working with and advocating for marginalized populations, but also about learning to effectively work with clients who differ from yourself as a practitioner. Activities and reflections are incorporated into each chapter of the text to provide a starting point for this process.

Gaining Cultural Competence in Career Counseling contains introductory information that will serve any professional looking to begin their journey toward cultural competency in career counseling. However, it is also an excellent tool for experienced practitioners who want to develop their knowledge of incorporating cultural competencies and social justice in their work. Again, Gaining Cultural Competence in Career Counseling takes practitioners beyond the material covered in social justice and multicultural and diversity trainings and provides a comprehensive guide for professionals of all levels.

Evans, K. M. & Sejuit, A. L. (2021). Gaining Cultural Competence in Career Counseling (2nd ed.). National Career Development Association.

Reviewed by: Erin Connelly, MS, EdS, University of North Georgia

The Professional Counselor

http://tpcjournal.nbcc.org

by Beatriz Sheldon and Albert Sheldon

by Beatriz Sheldon and Albert Sheldon

by Dr. Julia Bain, LPCC, NCC, CEAP

by Dr. Julia Bain, LPCC, NCC, CEAP