May 22, 2024 | Volume 14 - Issue 1

Kaprea F. Johnson, Alexandra Gantt-Howrey, Bisola E. Duyile, Lauren B. Robins, Natese Dockery

Career counselors practicing in rural communities must understand and address social determinants of mental health (SDOMH). This conceptual article details the relationships between SDOMH domains and employment and provides evidence-based recommendations for integrating SDOMH into practice through a rural community health and well-being framework. Description of the adaptation of the framework for career counselors in rural communities, SDOMH assessment strategies and tools, and workflow adjustments are included. Conclusions suggest next steps for practice and research.

Keywords: social determinants of mental health, career counselors, rural communities, health and well-being framework, assessment

Career counselors in rural communities address standard employment needs of the population, but they also must be aware of the socioeconomic circumstances that impact their community’s mental health and, in return, employment. Such socioeconomic factors are termed the social determinants of mental health (SDOMH). SDOMH are nonclinical psychosocial and socioeconomic circumstances that contribute to mental health outcomes (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion [ODPHP], n.d.). Healthy People 2030, a government initiative to promote health and well-being, describes a five-domain framework of SDOMH which includes: economic stability, education access and quality, health care access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, and social and community context (ODPHP, n.d.). Collectively, SDOMH can disrupt overall well-being and have a cyclical relationship with employment. For example, in rural communities, minimal access to public transportation may make sustaining employment difficult, which can then impact health insurance. Without insurance, a person loses access to health care; with unmet health care needs, a person who is unwell and without access to treatment has less opportunity for employment. Thus, understanding and addressing SDOMH is critically important for career counselors working in rural and other underserved communities (Pope, 2011). This conceptual paper will define SDOMH, introduce a theoretical framework for addressing SDOMH, provide evidence-based recommendations for assessment and treatment, and conclude with national resources to support career counselors in rural communities as they incorporate addressing SDOMH into their work.

Rural Communities, Employment, and Career Counselors

The U.S. Census Bureau considers rural communities as a group of people, counties, and housing outside of an urban area. More specifically, the Office of Management and Budget defines rural as areas with an urban core population of fewer than 50,000 people (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2017). After the 2010 Census, it was estimated that approximately 15% of the population lives in rural communities (Health Resources & Services Administration, 2017). Rural communities experience higher rates of unemployment and poverty, and residents are therefore more likely to live below the poverty line (United States Department of Agriculture [USDA], 2014). This is largely rooted in the fact that rural communities experience underdevelopment, economic decline, and neglect (Dwyer & Sanchez, 2016). Economic focus in rural environments typically centers around agriculture, rather than technological advancement (Dwyer & Sanchez, 2016). This contributes in part to a dearth of economic resources and thereby to increased unemployment and poverty and reduced health and well-being outcomes (Bradshaw, 2007; Brassington, 2011; Dwyer & Sanchez, 2016).

According to research conducted by the USDA, the unemployment rate in rural communities steadily declined for approximately 10 years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic; in September of 2019, the rural unemployment rate was 3.5% (Dobis et al., 2021). However, unemployment in rural communities reached 13.6% in April 2020, with unemployment disparately affecting those in more impoverished communities (Dobis et al., 2021). The role and goal of the career counselor is to help individuals in a specific community obtain or retain employment (Landon et al., 2019). For example, career counselors start the counseling process by systematically assessing clients’ needs, qualifications, and job aspirations. They provide career planning services and effective job search strategies. They help with résumé writing, interview preparations, skill development, and training opportunities (Amundson, 1993). Further, career counselors provide case management services by tracking and monitoring their clients’ progress. They record client information, document counseling sessions, track job applications, and survey employment outcomes (Amundson, 1993). Through tailored support, the career counselor works with the client throughout the life span to support the search for and maintaining of employment, while building client resilience and feelings of empowerment along the way.

However, rural communities have limited employment options and self-employment opportunities, which makes the role of the career counselor difficult in rural settings. Individuals in rural communities seeking employment may find it difficult to trust an outside counselor, and they may experience limited or no access to mental health services, health care practitioners, and transportation services, thereby negatively impacting their ability to participate effectively in the employment process (Landon et al., 2019). Career counselors in rural settings must develop a broader range of skills and connections to better serve their clients. These inequities experienced in rural settings reflect SDOMH and are factors which interfere with the role of the career counselor.

Social Determinants of Mental Health and Employment

SDOMH are the nonmedical factors shaped by the unequal distribution of power, privilege, and resources that influence the health outcomes of individuals and communities (World Health Organization, 2014). SDOMH concern the environmental living conditions that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). In the Healthy People 2030 framework, the ODPHP (n.d.) defined social determinants of health (SDOH) through five primary domains: Economic Stability, Education Access and Quality, Health Care Access and Quality, Neighborhood and Built Environment, and Social and Community Context. These five domains are important to understand within the context of employment. In the Economic Stability domain, employment is the most pertinent issue (ODPHP, n.d.), as a lack of employment typically influences both mental and physical health (Norström et al., 2019). A few distinct factors related to economic stability and employment include job security, work environment, monetary factors (e.g., pay), and the demands of the job (ODPHP, n.d.). For example, in rural communities, agriculture is a significant source of employment for individuals. However, this source of income is seemingly unstable, as farming and agriculture are mostly dependent on the season (Liebman, 2010). In the Education Access and Quality domain, enrollment in higher education or holding a higher education degree has been found to have a positive impact on employment, as well as yielding more positive overall health outcomes and optimal well-being (ODPHP, n.d.; USDA, 2017). For adults living in rural communities, unemployment rates are higher for those with lower education attainment, further supporting the connection between education and employment (USDA, 2017). Regarding the Health Care Access and Quality domain—specifically in rural communities—factors such as proximity to hospitals, lack of insurance, and the overall cost of health care can reduce accessibility. Health care, especially higher-quality health care, aids in preventing disease and improving individuals’ quality of life (ODPHP, n.d.). However, inadequate health care leads to higher rates of disease, which have a direct impact on individuals’ ability to sustain employment, due to factors such as missing work because of illness or having to travel further to receive health care (Dueñas et al., 2016).

Ability to travel is also a cause for concern in rural communities and is closely related to the Neighborhood and Built Environment domain. Healthy People 2030 proposed various objectives related to neighborhood and built environment, with one being to increase access to mass transit (ODPHP, n.d.). It is apparent that a lack of reliable transportation is directly tied to unemployment, especially in rural communities due to distance and limited accessibility (U.S. Department of Transportation, 2019). Public transportation carries many noteworthy benefits, such as reducing air pollution, being inexpensive compared to purchasing a car, minimizing the cost of fuel and upkeep for personal vehicles, and increased convenience. Although these positive aspects of public transportation are ideal, individuals living in rural communities may not be able to reap these benefits due to the lack of public transportation in these areas, perhaps also limiting employment options (Shoup & Homa, 2010; U.S. Department of Transportation, 2019).

Lastly, the fifth domain, Social and Community Context, is interrelated with employment, as it tends to have a significant impact on workplace conditions, influences individuals’ overall mental and physical health, and can hinder growth and development (Norström et al., 2019). Additionally, social cohesion and adequate support in communities can be leveraged to locate and obtain employment and other helpful resources; however, this often falls short in rural communities. For example, in rural communities, the inability to secure gainful employment is notably linked to geographical disparities, such as those within the Neighborhood and Built Environment SDOH domain. Examples of such geographic disparities which affect employment include limited or nonexistent options for public transportation, a lack of available local jobs, and a lack of childcare facilities for use by working parents. Rural communities also often experience a lack of resources to improve the employment outlook and overall well-being of their population (Bradshaw, 2007; Dwyer & Sanchez, 2016). In addition, structurally, it has been observed that economic resources tend to cluster or aggregate together. For example, businesses that have been successful in a community invite and attract more businesses, thus pulling resources away from rural communities that might not have such a history of business success. Meanwhile, communities that are left behind experience economic restructuring and delays in receiving new technologies, leading to fewer employment opportunities (Bradshaw, 2007; Landon et al., 2019). Thus, providing employment or vocational services in rural America can be particularly challenging.

Furthermore, unemployment, poverty, and mental health concerns are inextricably linked. When career counselors uncover and address these factors in rural America, they must consider the surplus of needed services and resources to systemically address interrelated issues. To be intentional, career counselors practicing in rural communities should consider using a theoretical foundation that provides direction for action on the SDOMH which impact their clients’ lives and ability to be gainfully employed. The Rural Community Health and Well-Being Framework (Annis et al., 2004) is a framework that would be exceedingly helpful in this pursuit.

Theoretical Framework for Action: Rural Community Health and Well-Being Framework

Rural communities make up over 20% of the population and are often classified by a lack of necessary resources, lower levels of education, and persistent economic inequities (Hughes et al., 2019; Mohatt et al., 2006). Although they face many challenges, individuals in rural communities have been found to be resilient, especially when the proper resources are available (Annis et al., 2004). Application of a theoretical framework to practice centered on the unique needs of rural communities is important in addressing SDOMH through career counseling. The Rural Community Health and Well-Being Framework (Annis et al., 2004) strategically builds upon community resiliency and identifies economic, social, and environmental factors which are seen as essential components of health in rural communities. This framework also implores career counselors to consider how SDOMH indicators impact the community as a whole as well as individual people. For example, the framework provides specific areas for increased career counselor awareness and action: health, safety and security, economics, education, environment, community infrastructure and processes, recreation, social support and cohesion, and the overall population. These specific areas for rural communities are within the SDOMH domains, but emphasis is placed on recognition of the specific areas within the SDOMH domains that have the greatest impact on the community.

This comprehensive framework centers the needs of rural communities and provides direction for assessing and addressing SDOMH that impact employment and overall well-being. This framework will assist in uncovering employment issues and barriers faced by individuals within rural communities. Using this framework to assess SDOMH conditions (e.g., economic, social, environmental) will aid in developing employment and mental health interventions that are socially conscious and address root causes of unemployment and poor mental health. Overall, this framework provides a model for assessing and addressing SDOMH in rural communities.

Adaptation for Career Counselors

Career counselors in rural communities who wish to use the Rural Community Health and Well-Being Framework for practice should consider doing the following: (a) increasing their awareness and understanding of SDOMH and the framework, (b) increasing their understanding of the specific community needs outlined by the framework, and (c) assessing the values and needs of the community. However, because the framework is primarily focused on community-level indicators of need, career counselors will need to adapt what they learn about the community to inform their practice with individual community members. The role of the career counselor is multifaceted; thus, career counselors can engage various aspects of their role, such as listener, leader, and evaluator, in their advocacy efforts.

To begin this process of learning about community and individual needs, Annis et al. (2004) suggested the importance of listening. For example, based on the community-level indicators of need, career counselors can assess individual clients for their unmet needs within those specific areas. By understanding how members of the community are experiencing indicators such as health, recreation, social support, transportation, and resources, career counselors will become better equipped to understand and address issues that are impacting their clients’ ability to obtain and maintain employment. Beyond the use of assessments, this framework equips career counselors to broach important conversations about social needs (Andermann, 2016) with their clients, to inform potential connection with community resources. These conversations may include explicit discussion about particular SDOMH challenges (e.g., education, safety, access to affordable childcare), as well as about the client’s sense of belonging, or lack thereof, within their community. These conversations should allow for increased understanding and rapport building through genuine listening and empathy (Annis et al., 2004; Covey, 1989).

Finally, the framework implores career counselors to advocate with and for individuals within their rural community to provide equitable employment opportunities (Crumb et al., 2019). Such advocacy may take place through connection with local rural community leaders, who may have power to alter or increase the distribution of certain resources within the community setting. For example, a career counselor may advocate on behalf of their clients to the local county board of commissioners for increased budget toward affordable transportation access within that county, thereby broadening clients’ access to job opportunities. Advocacy with local leaders outside of government might include collaboration with community college administrators for provision of additional support for working adults and parents who wish to return to school, such as more evening course options, advisor support, or readily available information on scholarships. Again, considering the aforementioned roles career counselors may have (e.g., leader, evaluator), career counselors may also consider further training in program evaluation—or collaboration with those who have such training—to better understand the efficacy of their community partnerships, referrals, and other advocacy-related efforts made toward supporting clients’ SDOMH.

Assessing and Addressing Social Determinants of Mental Health

As noted earlier, SDOMH are inextricably linked to employment, which means career counselors in rural communities must acknowledge these challenges and seek to address these issues with their clients. However, researchers have also highlighted the importance of considering both facilitators and barriers to addressing SDOMH challenges (Browne et al., 2021). In a qualitative case study of staff at a community health center and hospital, participants identified practical facilitators of SDOMH response, including community collaboration and support from leadership, as well as barriers such as time limitations and lack of resources (Browne et al., 2021). As career counselors hold similar client outcome goals as community mental health providers, they can take these findings into consideration when determining how to best respond to clients’ SDOMH challenges through attention to opportunities for collaboration with community leaders (e.g., religious leaders, politicians) and resources within the community (e.g., food banks, health care providers). Another study highlighted the importance of collaboration, partnerships with local agencies, and understanding the role of the counselor in SDOMH response (Johnson & Brookover, 2021; Robins et al., 2022). With these findings in mind, career counselors in rural communities are well positioned to assess for and address SDOMH challenges faced by their clients (Crucil & Amundson, 2017; Tang et al., 2021) through individual-level action (i.e., counseling) and systems-level advocacy action.

Systems-Level Advocacy Through Assessment

To effectively engage in systems-level advocacy, it is important for career counselors to recognize and understand the needs of their rural communities. When using the Rural Community Health and Well-Being Framework in practice, it is important to complete an assessment of the rural health of one’s community. Ryan-Nicholls and Racher (2004) purport that it is imperative to assess rural health within five categories: health status, health determinants, health behavior, health resources, and health service utilization. Counselors may consider these items when assessing the needs of their clients in rural communities, as these items provide a basis for assessment of other health factors, such as indicators of community health (e.g., environment and lifestyle) and economic well-being, and provide a foundation for systems-level advocacy and planning. This level of action focuses on improving the lives of the entire community through strategic advocacy efforts that improve population health and well-being (Ryan-Nicholls & Racher, 2004). A career counselor engaged at this level might focus their energy on advocating for increased economic development in their rural community, livable wages, universal health care, immigration issues, employment discrimination legislation, and other employment-related issues that impact the community directly or indirectly. Additionally, a career counselor may address client self-advocacy and utilize empowerment approaches to increase the voices of community members and their clients as related to work and employment needs.

In connection with this framework (Annis et al., 2004), career counselors can utilize this broader community-level assessment to inform specific points of advocacy. As an example, Annis et al. (2004) provided a sample form that may be utilized to collect community data on alcohol consumption (p. 79). Upon noting concern from individual clients on alcohol consumption, a career counselor may collaborate with public health professionals, for instance, to collect such data from the local community. Annis et al. encourage consideration of the implications for such findings, as well as opportunities for follow-up. After determining a need in the community for support regarding high alcohol consumption, the career counselor may utilize the framework to consider points of community resilience, including existing supports, attitudes about alcohol consumption, existing resources, and any actions the community is already taking in this area. Overall, assessment through the context suggested by Ryan-Nicholls and Racher (2004) may yield individual and community data to inform action to address SDOMH challenges through Annis et al.’s (2004) framework.

Individual-Level Action Through Assessment

When a client seeks services from a career counselor, the relationship centers on exploration and evaluation of the client’s education, training, work history, interests, skills, personality, and career goals. Through engaging with the Rural Community Health and Well-Being Framework, the career counselor might also examine the SDOMH facilitators and barriers that impact a client’s employment goals. To address employment and SDOMH, a career counselor must understand the community-level needs (i.e., systems approach) and the individual needs of their clients; for these goals, one strategy is to use assessments. There are various assessment tools that career counselors may find helpful, including the Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks, and Experiences (PRAPARE; National Association of Community Health Centers, 2017), an SDOH assessment tool purposed to empower professionals to not only understand their clients more holistically through assessment, but to better meet clients’ needs through the use of such information. The PRAPARE assessment tool includes questions related to four domains: Personal Characteristics, Family and Home, Money and Resources, and Social and Emotional Health. PRAPARE emphasizes the importance of assessing SDOMH needs of clients in order for providers to “define and document the complexity of their patients; transform care with integrated services and community partnerships to meet the needs of their patients; demonstrate the value they bring to patients, communities, and payers; and advocate for change in their communities” (https://prapare.org/). There are several benefits of using the PRAPARE assessment tool, such as it being free of charge, having a website linked to the tool with an “actionable toolkit and resources,’’ and being evidence-based. Barriers to using PRAPARE include that it is a long assessment tool that clients must complete in-office, which may slow workflow.

Another SDOH assessment tool is the WellRx Questionnaire (Page-Reeves et al., 2016). The WellRx Questionnaire is an 11-item screening tool that gathers information on various SDOMH, like food security, access to transportation, employment, and education. Participants are to answer “yes” or “no” to each item on the questionnaire. According to Page-Reeves and colleagues (2016), the WellRx Questionnaire provides a feasible means of assessing patients’ social needs and thereby addressing those needs. Benefits to using the WellRx include that it is free of cost, questions are at a 4th-grade reading level, and it can typically be completed by a client individually without the help of a professional. A potential barrier is that it does not assess a wide range of SDOMH challenges. Lastly, Andermann (2018) conducted a scoping review of social needs screening tools and found that the focus on such screening has increased over time. Andermann suggested that health care workers take advantage of the existing means of assessment, and made a number of specific resource recommendations, such as the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (2019) and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (2022).

Addressing SDOMH Through Action

Documenting and defining the needs of clients through assessment is the first step in addressing SDOMH. The next step is taking action through an integrated career counseling approach. An integrated approach may include consistent collaboration with other professionals, like medical doctors, nurse practitioners, social workers, probation officers, or case managers. Additionally, scholars like Andermann (2016) suggest integrated efforts such as ensuring social challenges are included in client records and shared with other professionals to best support care. For “particularly isolated and hard-to-reach patients . . . [actions like] assertive outreach, patient tracking and individual case managers” may be helpful (para. 19). Another practical suggestion for beginning to address clients’ SDOMH challenges is adding an SDOMH assessment tool or specific SDOMH questions to an intake form that the client completes independently or during the intake session. Selection of specific questions can be derived from the data that displays community-level needs (e.g., systems-level advocacy through assessment). For example, if a community-level assessment found that public transportation was lacking, then transportation might be an important assessment question on the SDOMH screener.

Another consideration specific for career counselors is that counselors are obligated by their code of ethics to take appropriate action based on assessment results (American Counseling Association [ACA], 2014, Section E.2.b.). Appropriate action can include consultation and collaboration with other professionals within and outside of counseling and/or advocacy to address the SDOMH need. After establishing the need through assessment, it is important for the career counselor to support the client in understanding system-level challenges and to work to address SDOMH issues while simultaneously supporting employment needs. For example, a career counselor who determines that their client is struggling with food insecurity might address this issue in several ways. At the individual level, the counselor might print resources for local food pantries, assist the client in applying for SNAP benefits, and counsel the client on resources within the community to access food. They could establish a small food pantry within the office, collaborate with local restaurants to receive pre-packaged food that might otherwise be disposed of, or consult with local food pantries and free food kitchens to establish a mobile pantry and kitchen. At the systems level, a career counselor may build partnerships with local farmers to increase locations where fresh fruits and vegetables are available for little or no cost.

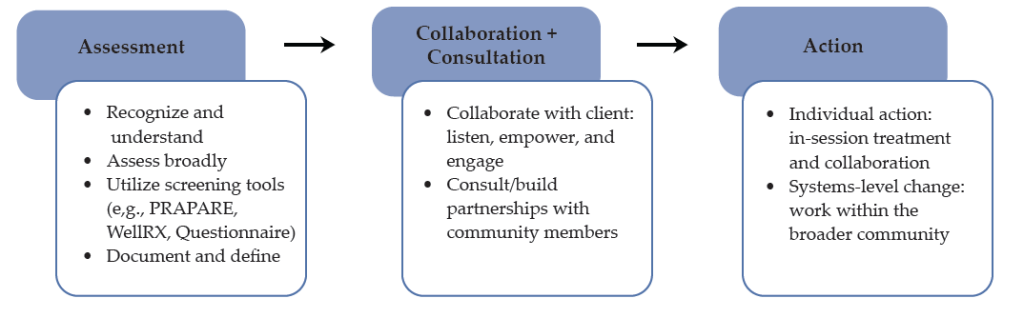

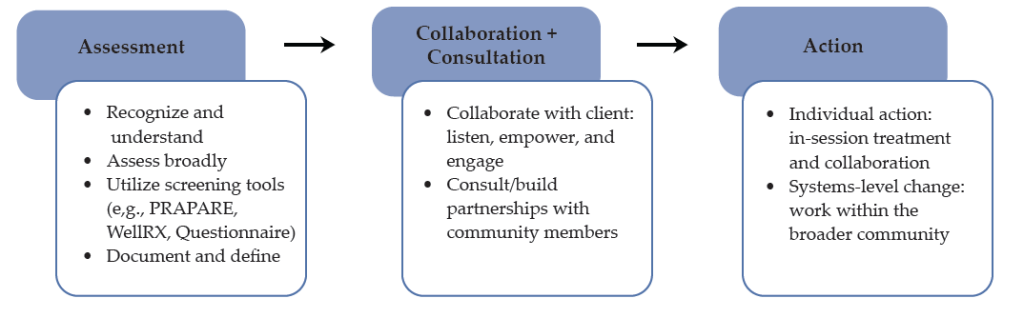

Collaboration and consultation are imperative to addressing the complex needs of clients in rural communities who are both seeking career counseling and challenged by SDOMH issues. For example, as noted earlier, health care access and quality are major disruptors of employment, and addressing these challenges will afford benefits for employment. The career counselor can consider using interprofessional collaboration and telehealth to support the health care needs of their rural clients (Johnson & Mahan, 2020). Interprofessional collaboration is a practice in which health care providers from two or more professional backgrounds interact and practice with the client at the center of care (Prentice et al., 2015). Using telehealth, the distribution of health-related services via telecommunication technologies is a useful strategy to support the health care needs of persons in rural communities. A career counselor can address health care access through telehealth in several ways, including education (e.g., introduce their client to telehealth; assist them in understanding the technology), telehealth (e.g., provide the telecommunication equipment in the office), and collaborative partnership (e.g., use a portion of the career counseling session to assist the client in connecting with health care providers using distance technology). As a collaborative partner in addressing health care access and quality, the career counselor can also use future sessions to follow up with the client on their experience with telehealth and, if needed, assist them in connecting to other health care providers. Figure 1 provides a visual for conceptualizing how career counselors may navigate the SDOMH needs of their clients, from assessment to action.

Figure 1

Working to Address Clients’ SDOMH Needs

Lastly, in the work of addressing SDOMH and employment, counselors should be aware of local, state, and national resources. Local and state resources are unique to every state but have similar purposes which include disseminating information on local resources and initiatives and providing public services that address SDOMH (e.g., food banks, public programs). National resources that are accessible to every community include 211 and the “findhelp.org” website. The Federal Communications Commission designated 211 as a national number in the United States that anyone can call for information and referrals to social services and other assistance. The services provided by 211 are confidential and free, available 24/7, and help connect people in the United States to essential community services. Moreover, the “findhelp.org” website is designed to help people search and connect with social care support based on their ZIP Code.

Integrating career counseling and social care support in rural communities is a strategy to facilitate the readiness of clients for work and the sustainability of employment for clients because basic needs are met or being addressed. While every rural community is unique, the foundation of understanding both systemic and individual SDOMH needs—and addressing those needs through strategic partnerships and individual counseling, as well as advocacy—is important in every rural community and to the success of any career counseling endeavor.

Discussion

In rural communities, career counselors hold a significant role. They are tasked with aiding individuals with employment needs; they may often address mental health concerns, and while doing so, it is important for them to be aware of and prepared to address SDOMH. Career counselors can gain more insight into issues related to SDOMH through consultation, collaboration, and advocacy, which should all be a part of the repertoire of a rural career counselor. The use of theoretical frameworks such as the Rural Community Health and Well-Being Framework (Racher et al., 2004) provides direction for career counselors seeking to understand the systemic issues impacting employment access and opportunities in the community, as well as direction for intervention. This framework will assist in identifying and minimizing barriers to employment that may exist within rural communities. More specifically, this framework will help to uncover SDOMH challenges that exist in the community and serve as barriers to well-being and employment and provide direction for advocating for resources necessary for equitable work opportunities and environments. Being that individuals in rural America experience various barriers that have huge impacts on their lives, such a guide for career counselors is essential.

Lastly, addressing SDOMH within career counseling is a social justice issue that counselors should address (ACA, 2014; Crucil & Amundson, 2017; Ratts et al., 2016). The Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies (MSJCC; Ratts et al., 2016) serve as a guide for counselors to address social justice issues and were endorsed by the ACA in 2015. Like the aforementioned framework and empirically based suggestions, the MSJCC includes four areas of competence: counselor self-awareness, client worldview, counseling relationship, and counseling and advocacy interventions. The authors of the MSJCC also implore counselors to consider “attitudes and beliefs, knowledge, skills, and action,” and suggest that competent counselors are aware of the experiences of marginalized clients (Ratts et al., 2016; p. 3). Thus, career counselors’ efforts to assess and address the individual and systems-based SDOMH challenges faced by their clients is social justice work that career counselors are trained and prepared to address.

Implications

Given this review, there are specific implications for career counselors practicing in rural communities, counselor educators training career counselors, and pertinent policy needs.

Practicing Career Counselors

The role of the career counselor often entails identifying employment objectives, goals, and needs for both the job seeker and employer. In addition, the career counselor is responsible for résumé development, teaching job placement and retention skills, providing self-advocacy tips, teaching organizational goal–redefining skills, and many other components (Ysasi et al., 2018). However, providing these services can be difficult when the individuals reside in rural communities because of the SDOMH disparities such as limited available resources, isolation, increased poverty, and decreased educational and employment opportunities (Temkin, 1996).

Therefore, career counselors must actively work to ensure their visibility and accessibility to individuals in rural areas who are seeking employment opportunities. Further, career counselors need to market themselves and their skills to employers and job seekers of rural communities. Consequently, marketing generally entails engaging and developing community partnerships with employers and job seekers, which involves educating individuals unfamiliar with the specific services that career counselors provide. In addition, employers are often interested in services that improve their business (e.g., increase revenue), while job seekers may be searching for skill training to achieve employment goals (Richardson et al., 2010). Therefore, career counselors can enhance service delivery and provide adequate services when they intentionally market their services to the community members.

Furthermore, job insecurity has been linked to mental health concerns like stress and anxiety, financial concerns, and fear of organizational change (Holm & Hovland, 1999). Therefore, career counselors need to be aware of the impact of job insecurity on rural communities and devise strategies to help organizations and workers manage job insecurity. Managing job insecurity of workers in rural organizations could include helping organizations to redefine their present and future goals and commitments made to employees. Organizations could also manage organizational transitions depending on the skills and resources available to affected employees (Holm & Hovland, 1999). Clearly stated organizational objectives, goals, and plans can help employees feel less insecure about their jobs and increase focus on their roles and responsibilities instead of devising means to move out of the community for a better and more secure future. In addition, career counselors in rural communities should be aware of the mental health concerns experienced by employees and job seekers and connect them to available mental health resources.

Counselor Educators

Counselor educators are responsible for the training and development of the next generation of counselors, including career counselors. It will be important for counselor educators to include training on SDOMH, interprofessional collaboration, and telehealth, as these are especially relevant for rural communities ( Johnson & Mahan, 2021; Johnson & Rehfuss, 2021). It is essential to provide adequate time to review and discuss SDOMH in all courses throughout the curriculum (Waters et al., 2022) to ensure the competence of career counselors. To ensure this continuity, counselor educators should advocate for an SDOMH module across the curriculum. This would ensure the inclusion of this content throughout the program, providing ample opportunity for the understanding of SDOMH and how they should be addressed. Career counselors must be prepared to address the complex employment and social health needs with which their clients might present. Without adequate education and training, these will seem much more difficult to address.

Policy

In addressing both SDOMH and employment needs in rural communities, advocating for policy and legislative change is imperative. Lewis et al. (2002) described counselors’ roles in sharing public information as awakening the public to macro-systemic issues related to human dignity and engaging in social/political advocacy, or “influencing public policy in a large, public arena” (p. 2). Thus, career counselors are encouraged to benefit their clients through engaging in advocacy to influence policy at the local, state, and national levels. Similarly, Crucil and Amundson (2017) implore career counselors to engage in the work of influencing politics and policy and suggest awareness as a first step to enacting change through the sharing of information and impacting policy. To develop such awareness, career counselors may begin by reading about SDOMH disparities related specifically to employment issues from reputable sources. For instance, the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI; 2014) has published various reports related to such issues, including the informative publication entitled Road to Recovery: Employment and Mental Illness. NAMI (2021) also published a legislative coalition letter written in support of increased SDOH funding to Congress. Career counselors may work to build their own awareness and understanding of the social and political events and influences which impact their clients, building toward eventual action in this realm.

Moreover, regarding policy change, researchers have suggested career counselors should be aware of and actively engaged in policy efforts (Crucil & Amundson, 2017; Watts, 2000). Watts (2000) described public policy considering career development as including four distinct roles: legislation, remuneration, exhortation, and regulation. Watts described these roles in detail and implored career counselors to influence these policy processes by seeking the support of interest groups and communicating with policy makers. Again, career counselors can work individually and within their own communities to increase their awareness and knowledge of policies and their impact. They can work toward influencing policies at the state and national levels to improve the accessibility and existence of important social programs and resources.

Conclusion

Career counselors in rural communities have a responsibility to acknowledge and address SDOMH challenges that are disproportionately impacting their clients. Collaboration, consultation, counseling framed through the lens of SDOMH, and advocacy appear to be strategies to support the employment needs of individuals and the rural community. Employment services in rural communities must be framed through a socially conscious (e.g., aware of the SDOMH systemic issues), action-oriented (e.g., prepared to engage in advocacy), and resiliency-focused lens that provides tailored individual services while simultaneously addressing systemic issues.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

American Counseling Association. (2014). ACA code of ethics. https://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/default-document-library/2014-code-of-ethics-finaladdress.pdf

Amundson, N. E. (1993). Mattering: A foundation for employment counseling and training. Journal of Employment Counseling, 30(4), 146–152. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1920.1993.tb00173.x

Andermann, A. (2016). Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: A framework for health professionals. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 188(17–18), E474–E483. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.160177

Andermann, A. (2018). Screening for social determinants of health in clinical care: Moving from the margins to the mainstream. Public Health Reviews, 39(1), 1–17.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-018-0094-7

Annis, R. C., Racher, F., & Beattie, M. (Eds.). (2004). Rural community health and well-being: A guide to action. Rural Development Institute. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242551842_Rural_Community_Health_and_Well-Being_A_Guide_to_Action

Bradshaw, T. K. (2007). Theories of poverty and anti-poverty programs in community development. Community Development, 38(1), 7–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330709490182

Brassington, I. (2011). What’s wrong with the brain drain? Developing World Bioethics, 12(3), 113–120.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-8847.2011.00300.x

Browne, J., Mccurley, J. L., Fung, V., Levy, D. E., Clark, C. R., & Thorndike, A. N. (2021). Addressing social determinants of health identified by systematic screening in a Medicaid accountable care organization: A qualitative study. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health, 12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150132721993651

Canadian Task Force on Preventative Health Care. (2019). Canadian task force on preventive health care.

https://canadiantaskforce.ca

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). CDC 2020 in review. https://archive.cdc.gov/#/details?url=

https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p1229-cdc-2020-review.html

Covey, S. (1989). The 7 habits of highly effective people: Restoring the character ethic. Simon & Schuster.

Crucil, C., & Amundson, N. (2017). Throwing a wrench in the work(s): Using multicultural and social justice competency to develop a social justice–oriented employment counseling toolbox. Journal of Employment Counseling, 54(1), 2–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/joec.12046

Crumb, L., Haskins, N., & Brown, S. (2019). Integrating social justice advocacy into mental health counseling in rural, impoverished American communities. The Professional Counselor, 9(1), 20–34. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1215753.pdf

Dobis, E. A., Krumel, T. P., Jr., Cromartie, J., Conley, K. L., Sanders, A., & Ortiz, R. (2021). Rural America at a glance: 2021 edition. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/102576/eib-230.pdf

Dueñas, M., Ojeda, B., Salazar, A., Mico, J. A., & Failde, I. (2016). A review of chronic pain impact on patients, their social environment and the health care system. Journal of Pain Research, 2016(9), 457–467. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S105892

Dwyer, R. E., & Sanchez, D. (2016). Population distribution and poverty. In M. J. White (Ed.), International handbook of migration and population distribution (pp. 485–504). Springer Science & Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-7282-2

Health Resources and Services Administration. (2017). Defining rural population. https://www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/about-us/definition/index.html

Holm, S., & Hovland, J. (1999). Waiting for the other shoe to drop: Help for the job-insecure employee. Journal of Employment Counseling, 36(4), 156–166.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1920.1999.tb01018.x

Hughes, M. C., Gorman, J. M., Ren, Y., Khalid, S., & Clayton, C. (2019). Increasing access to rural mental health care using hybrid care that includes telepsychiatry. Journal of Rural Mental Health, 43(1), 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1037/rmh0000110

Johnson, K. F., & Brookover, D. L. (2021). School counselors’ knowledge, actions, and recommendations for addressing social determinants of health with students, families, and in communities. Professional School Counseling, 25(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X20985847

Johnson, K. F., & Mahan, L. B. (2020). Interprofessional collaboration and telehealth: Useful strategies for family counselors in rural and underserved areas. The Family Journal, 28(3), 215–224.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480720934378

Johnson, K. F., & Rehfuss, M. (2021). Telehealth interprofessional education: Benefits, desires, and concerns of counselor trainees. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 16(1), 15–30.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2020.1751766

Johnson, K. F., & Robins, L. B. (2021). Counselor educators’ experiences and techniques teaching about social-health inequities. Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 14(4), 1–25. https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/jcps/vol14/iss4/7

Landon, T., Connor, A., McKnight-Lizotte, M., & Peña, J. (2019). Rehabilitation counseling in rural settings: A phenomenological study on barriers and supports. Journal of Rehabilitation, 85(2), 47–57. https://bit.ly/4cvWSoT

Lewis, J., Arnold, M. S., House, R., & Toporek, R. L. (2002). ACA advocacy competencies. http://www.counseling.org/Resources/Competencies/Advocacy_Competencies.pdf

Liebman, A. K., & Augustave, W. (2010). Agricultural health and safety: Incorporating the worker perspective. Journal of Agromedicine, 15(3), 192–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/1059924x.2010.486333

Mohatt, D. F., Bradley, M. M., Adams, S. J., & Morris, C. D. (2006). Mental health and rural America: 1994-2005. An overview and annotated bibliography. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED591902

National Alliance on Mental Health. (2014). Road to recovery: Employment and mental illness. https://nami.org/Support-Education/Publications-Reports/Public-Policy-Reports/RoadtoRecovery

National Alliance on Mental Health. (2021, April 8). Letter to congressional leadership. https://www.nami.org/getattachment/c3b797bf-5116-457f-ada9-b6b6f1f6adfb/Letter-to-Congressional-Committee-Leadership-on-So

National Association of Community Health Centers. (2017). PRAPARE. https://www.nachc.org/research-and-data/prapare

Norström, F., Waenerlund, A.-K., Lindholm, L., Nygren, R., Sahlén, K.-G., & Brydsten, A. (2019). Does unemployment contribute to poorer health-related quality of life among Swedish adults? BMC Public Health, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6825-y

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2020). Healthy People 2030: Social determinants of health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health

Page-Reeves, J., Kaufman, W., Bleecker, M., Norris, J., McCalmont, K., Ianakieva, V., Ianakieva, D. & Kaufman, A. (2016). Addressing social determinants of health in a clinic setting: The WellRx pilot in Albuquerque, New Mexico. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 29(3), 414–418. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2016.03.150272

Pope, M. (2011). The Career Counseling With Underserved Populations model. Journal of Employment Counseling, 48(4), 153–155. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1920.2011.tb01100.x

Prentice, D., Engel, J., Taplay, K., & Stobbe, K. (2015). Interprofessional collaboration: The experience of nursing and medical students’ interprofessional education. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 2, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333393614560566

Racher, F., Everitt, J., Annis, R., Gfellner, B., Ryan-Nicholls, K., Beattie, M., Gibson, R., & Funk, E. (2004). Rural community health & well-being. In R. Annis, F. Racher, & M. Beattie (Eds.), Rural community health and well-being: A guide to action (pp. 18–37). Rural Development Institute.

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar-McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2016). Multicultural and social justice counseling competencies: Guidelines for the counseling profession. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 44(1), 28–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmcd.12035

Richardson, N., Gosnay, R. M., & Carroll, A. (2010). A quick start guide to social media marketing: High impact low-cost marketing that works. Kogan Page Publishers.

Robins, L. B., Johnson, K. F., Duyile, B., Gantt-Howrey, A., Dockery, N., Robins, S., & Wheeler, N. (2022). Family counselors addressing social determinants of mental health in underserved communities. The Family Journal, 31(2), 213–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/10664807221132799

Ryan-Nicholls, K. D., & Racher, F. E. (2004). Investigating the health of rural communities: Toward framework development. Rural and Remote Health, 4(1), 1–10.

https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/informit.613919155641626

Shoup, L., & Homa, B. (2010). Principles for improving transportation options in rural and small town communities. https://t4america.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/T4-Whitepaper-Rural-and-Small-Town-Communities.pdf

Tang, M., Montgomery, M. L. T., Collins, B., and Jenkins, K. (2021). Integrating career and mental health counseling: Necessity and strategies. Journal of Employment Counseling, 58, 23–35.

https://doi.org/10.1002/joec.12155

Temkin, A. (1996). Creative options for rural employment: A beginning. In N. L. Arnold (Ed.), Self-employment in vocational rehabilitation: Building on lessons from rural America (pp. 61–64). Research and Training Center on Rural Rehabilitation Services.

United States Census Bureau. (2014). 2010-2014 ACS 5-year estimates. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/technical-documentation/table-and-geography-changes/2014/5-year.html

United States Department of Agriculture. (2014). Rural America at a glance: 2014 edition. https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=42897

United States Department of Agriculture. (2017). Rural education at a glance, 2017 edition. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/83078/eib-171.pdf

United States Preventive Services Taskforce. (2022). US preventative services taskforce. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf

U.S. Department of Transportation. (2019). Rural public transportation systems. https://www.transportation.gov/mission/health/Rural-Public-Transportation-Systems

Waters, J. M., Gantt, A., Worth, A., Duyile, B., Johnson, K. F., & Mariotto, D. (2022). Motivated but challenged: Counselor educators’ experiences teaching about social determinants of health. Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 15(2), 1–30. https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/jcps/vol15/iss2/6

Watts, A. G. (2000). Career development and public policy. Journal of Employment Counseling, 37(2), 62–75. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1920.2000.tb00824.x

World Health Organization. (2014). Social determinants of mental health. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/112828/9789241506809_eng.pdf

Ysasi, N. A., Tiro, L., Sprong, M. E., & Kim, B. J. (2018). Marketing vocational rehabilitation services in rural communities. In D. A. Harley, N. A. Ysasi, M. L. Bishop, & A. R. Fleming (Eds.), Disability and vocational rehabilitation in rural settings: Challenges to service delivery (pp. 545–552). Springer.

Kaprea F. Johnson, PhD, LPC, is a professor and Associate Vice Provost for Faculty Development & Recognition at The Ohio State University. Alexandra Gantt-Howrey, PhD, LPC (ID), is an assistant professor at Idaho State University. Bisola E. Duyile, PhD, LPC, CRC, is an assistant professor at Montclair State University. Lauren B. Robins, PhD, is a clinical assistant professor and distance learning coordinator at Old Dominion University. Natese Dockery, MS, NCC, LPC, CSAM, is a licensed professional counselor and doctoral student. Correspondence may be addressed to Kaprea F. Johnson, The Ohio State University, 1945 N. High Street, Columbus, OH 43210, johnson.9545@osu.edu.

Aug 20, 2021 | Volume 11 - Issue 3

Alison M. Boughn, Daniel A. DeCino

This article introduces the development and implementation of the Psychological Maltreatment Inventory (PMI) assessment with child respondents receiving services because of an open child abuse and/or neglect case in the Midwest (N = 166). Sixteen items were selected based on the literature, subject matter expert refinement, and readability assessments. Results indicate the PMI has high reliability (α = .91). There was no evidence the PMI total score was influenced by demographic characteristics. A positive relationship was discovered between PMI scores and general trauma symptom scores on the Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children Screening Form (TSCC-SF; r = .78, p = .01). Evidence from this study demonstrates the need to refine the PMI for continued use with children. Implications for future research include identification of psychological maltreatment in isolation, further testing and refinement of the PMI, and exploring the potential relationship between psychological maltreatment and suicidal ideation.

Keywords: psychological maltreatment, child abuse, neglect, assessment, trauma

In 2012, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC; 2012) reported that the total cost of child maltreatment (CM) in 2008, including psychological maltreatment (PM), was $124 billion. Fang et al. (2012) estimated the lifetime burden of CM in 2008 was as high as $585 billion. The CDC (2012) characterized CM as rivaling “other high profile public health problems” (para. 1). By 2015, the National Institutes of Health reported the total cost of CM, based on substantiated incidents, was reported to be $428 billion, a 345% increase in just 7 years; the true cost was predictably much higher (Peterson et al., 2018). Using the sensitivity analysis done by Fang et al. (2012), the lifetime burden of CM in 2015 may have been as high as $2 trillion. If these trends continue unabated, the United States could expect a total cost for CM, including PM, of $5.1 trillion by 2030, with a total lifetime cost of $24 trillion. More concerning, this increase would not account for any impact from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Mental health first responders and child protection professionals may encounter PM regularly in their careers (Klika & Conte, 2017; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS], 2018). PM experiences are defined as inappropriate emotional and psychological acts (e.g., excessive yelling, threatening language or behavior) and/or lack of appropriate acts (e.g., saying I love you) used by perpetrators of abuse and neglect to gain organizational control of their victims (American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children [APSAC], 2019; Klika & Conte, 2017; Slep et al., 2015). Victims may experience negative societal perceptions (i.e., stigma), fear of retribution from caregivers or guardians, or misdiagnosis by professional helpers (Iwaniec, 2006; López et al., 2015). They often face adverse consequences that last their entire lifetime (Spinazzola et al., 2014; Tyrka et al., 2013; Vachon et al., 2015; van der Kolk, 2014; van Harmelen et al., 2010; Zimmerman & Mercy, 2010). PM can be difficult to identify because it leaves no readily visible trace of injury (e.g., bruises, cuts, or broken bones), making it complicated to substantiate that a crime has occurred (Ahern et al., 2014; López et al., 2015). Retrospective data outlines evaluation processes for PM identification in adulthood; however, childhood PM lacks a single definition and remains difficult to assess (Tonmyr et al., 2011). These complexities in identifying PM in children may prevent mental health professionals from intervening early, providing crucial care, and referring victims for psychological health services (Marshall, 2012; Spinazzola et al., 2014). The Psychological Maltreatment Inventory (PMI) is the first instrument of its kind to address these deficits.

Child Psychological Maltreatment

Although broadly conceptualized, child PM experiences are described as literal acts, events, or experiences that create current or future symptoms that can affect a victim without immediate physical evidence (López et al., 2015). Others have extended child PM to include continued patterns of severe events that impede a child from securing basic psychological needs and convey to the child that they are worthless, flawed, or unwanted (APSAC, 2019). Unfortunately, these broad concepts lack the specificity to guide legal and mental health interventions (Ahern et al., 2014). Furthermore, legal definitions of child PM vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction and state to state (Spinazzola et al., 2014). The lack of consistent definitions and quantifiable measures of child PM may create barriers for prosecutors and other helping professionals within the legal system as well as a limited understanding of PM in evidence-based research (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013; APSAC, 2019; Klika & Conte, 2017). These challenges are exacerbated by comorbidity with other forms of maltreatment.

Co-Occurring Forms of Maltreatment

According to DHHS (2018), child PM is rarely documented as occurring in isolation compared to other forms of maltreatment (i.e., physical abuse, sexual abuse, or neglect). Rather, researchers have found PM typically coexists with other forms of maltreatment (DHHS, 2018; Iwaniec, 2006; Marshall, 2012). Klika and Conte (2017) reported that perpetrators who use physical abuse, inappropriate language, and isolation facilitate conditions for PM to coexist with other forms of abuse. Van Harmelen et al. (2011) argued that neglectful acts constitute evidence of PM (e.g., seclusion; withholding medical attention; denying or limiting food, water, shelter, and other basic needs).

Consequences of PM Experienced in Childhood

Mills et al. (2013) and Greenfield and Marks (2010) noted PM experiences in early childhood might manifest in physical growth delays and require access to long-term care throughout a victim’s lifetime. Children who have experienced PM may suffer from behaviors that delay or prevent meeting developmental milestones, achieving academic success in school, engaging in healthy peer relationships, maintaining physical health and well-being, forming appropriate sexual relationships as adults, and enjoying satisfying daily living experiences (Glaser, 2002; Maguire et al., 2015). Neurological and cognitive effects of PM in childhood impact children as they transition into adulthood, including abnormalities in the amygdala and hippocampus (Tyrka at al., 2013). Brown et al. (2019) found that adults who reported experiences of CM had higher rates of negative responses to everyday stress, a larger constellation of unproductive coping skills, and earlier mortality rates (Brown et al., 2019; Felitti et al., 1998). Furthermore, adults with childhood PM experiences reported higher rates of substance abuse than those compared to control groups (Felitti et al., 1998).

Trauma-Related Symptomology. Researchers speculate that children exposed to maltreatment and crises, especially those that come without warning, are at greater risk for developing a host of trauma-related symptoms (Spinazzola et al., 2014). Developmentally, children lack the ability to process and contextualize their lived experiences. Van Harmelen et al. (2010) discovered that adults who experienced child PM had decreased prefrontal cortex mass compared to those without evidence of PM. Similarly, Field et al. (2017) found those unable to process traumatic events produced higher levels of stress hormones (i.e., cortisol, epinephrine, norepinephrine); these hormones are produced from the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) and sympathetic-adrenal-medullary (SAM) regions in the brain. Some researchers speculate that elevated levels of certain hormones and hyperactive regions within the brain signal the body’s biological attempt to reduce the negative impact of PM through the fight-flight-freeze response (Porges, 2011; van der Kolk, 2014).

Purpose of Present Study

At the time of this research, there were few formal measures using child self-report to assess how children experience PM. We developed the PMI as an initial quantifiable measure of child PM for children and adolescents between the ages of 8 and 17, as modeled by Tonmyr and colleagues (2011). The PMI was developed in multiple stages, including 1) a review of the literature, 2) a content validity survey with subject matter experts (SMEs), 3) a pilot study (N = 21), and 4) a large sample study (N = 166). An additional instrument, the Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children Screening Form (TSCC-SF; Briere & Wherry, 2016), was utilized in conjunction with the PMI to explore occurrences of general trauma symptoms among respondents. The following four research questions were investigated:

- How do respondent demographics relate to PM?

- What is the rate of PM experience with respondents who are presently involved in an open CM case?

- What is the co-occurrence of PM among various forms of CM allegations?

- What is the relationship between the frequency of reported PM experiences and the frequency of general trauma symptoms?

Method

Study 1: PMI Item Development and Pilot

Following the steps of scale construction (Heppner et al., 2016), the initial version of the PMI used current literature and definitions from facilities nationwide that provide care for children who have experienced maltreatment and who are engaged with court systems, mental health agencies, or social services. Our lead researcher, Alison M. Boughn, developed a list of 20 items using category identifications from Glaser (2002) and APSAC (2019). Items were also created using Slep et al.’s (2015) proposed inclusion language for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) diagnostic codes and codes from the International Classification of Diseases, 11th edition (ICD-11) definition criteria (APA, 2013). Both Boughn and Daniel A. DeCino, our other researcher, reviewed items for consistency with the research literature and removed four redundant items. The final 16 items were reevaluated for readability for future child respondents using a web-based, age range–appropriate readability checker (Readable, n.d.) and were then presented to local SMEs in a content validity survey to determine which would be considered essential for children to report as part of a child PM assessment.

Expert Validation

A multidisciplinary team (MDT) serving as SMEs completed an online content validity survey created by Boughn. The survey was distributed by a Child Advocacy Center (CAC) manager to the MDT. Boughn used the survey results to validate the PMI’s item content relevance. Twenty respondents from the following professions completed the survey: mental health (n = 6), social services (n = 6), law enforcement (n = 3), and legal services (n = 5). The content validity ratio (CVR) was then calculated for the 16 proposed items.

Results. The content validity survey scale used a 3-point Likert-type scale: 0 = not necessary; 1 = useful, but not essential; and 2 = essential. A minimum of 15 of the 20 SMEs (75% of the sample), or a CVR ≥ .5, was required to deem an item essential (Lawshe, 1975). The significance level for each item’s content validity was set at α = .05 (Ayre & Scally, 2014). After conducting Lawshe’s (1975) CVR and applying the ratio correction developed by Ayre and Scally (2014), it was determined that eight items were essential: Item 2 (CVR = .7), Item 3 (CVR = .9), Item 4 (CVR = .6), Item 6 (CVR = .6), Item 7 (CVR = .8), Item 10 (CVR = .6), Item 15 (CVR = .5), and Item 16 (CVR = .6).

Upon further evaluation, and in an effort to ensure that the PMI items served the needs of interdisciplinary professionals, some items were rated essential for specific professions; these items still met the CVR requirements (CVR = 1) for the smaller within-group sample. These four items were unanimously endorsed by SMEs for a particular profession as essential: Item 5 (CVR Social Services = 1; CVR Law Enforcement = 1), Item 11 (CVR Law Enforcement = 1), Item 13 (CVR Law Enforcement = 1), and Item 14 (CVR Law Enforcement = 1).

Finally, an evaluation of the remaining four items was completed to explore if items were useful, but not essential. Using the minimum CVR ≥ .5, it was determined that these items should remain on the PMI: Item 1 (CVR = .9), Item 8 (CVR = .8), Item 9 (CVR = .9), and Item 12 (CVR = .9). The use of Siegle’s (2017) Reliability Calculator determined the Cronbach’s α level for the PMI to be 0.83, indicating adequate internal consistency. Additionally, a split-half (odd-even) correlation was completed with the Spearman-Brown adjustment of 0.88, indicating high reliability (Siegle, 2017).

Pilot Summary

The focus of the pilot study was to ensure effective implementation of the proposed research protocol following each respondent’s appointment at the CAC research site. The pilot was implemented to ensure research procedures did not interfere with typical appointments and standard procedures at the CAC. Participation in the PMI pilot was voluntary and no compensation was provided for respondents.

Sample. The study used a purposeful sample of children at a local, nationally accredited CAC in the Midwest; both the child and the child’s legal guardian agreed to participate. Because of the expected integration of PM with other forms of abuse, this population was selected to help create an understanding of how PM is experienced specifically with co-occurring cases of maltreatment. Respondents were children who (a) had an open CM case with social services and/or law enforcement, (b) were scheduled for an appointment at the CAC, and (c) were between the ages of 8 and 17.

Measures. The two measures implemented in this study were the developing PMI and the TSCC-SF. At the time of data collection, CAC staff implemented the TSCC-SF as a screening tool for referral services during CAC victim appointments. To ensure the research process did not interfere with chain-of-custody procedures, collected investigative testimony, or physical evidence that was obtained, the PMI was administered only after all normally scheduled CAC procedures were followed during appointments.

PMI. The current version of the PMI is a self-report measure that consists of 16 items on a 4-point Likert-type scale that mirrors the language of the TSCC-SF (0 = never to 3 = almost all the time). Respondents typically needed 5 minutes complete the PMI. Sample items from the PMI included questions like: “How often have you been told or made to feel like you are not important or unlovable?” The full instrument is not provided for use in this publication to ensure the PMI is not misused, as refinement of the PMI is still in progress.

TSCC-SF. In addition to the PMI, Boughn gathered data from the TSCC-SF (Briere & Wherry, 2016) because of its widespread use among clinicians to efficiently assess for sexual concerns, suicidal ideation frequency, and general trauma symptoms such as post-traumatic stress, depression, anger, disassociation, and anxiety (Wherry et al., 2013). The TSCC-SF measures a respondent’s frequency of perceived experiences and has been successfully implemented with children as young as 8 years old (Briere, 1996). The 20-item form uses a 4-point Likert-type scale (0 = never to 3 = almost all the time) composed of general trauma and sexual concerns subscales. The TSCC-SF has demonstrated high internal consistency and alpha values in the good to excellent ranges; it also has high intercorrelations between sexual concerns and other general trauma scales (Wherry & Dunlop, 2018).

Procedures. Respondents were recruited during their scheduled CAC appointment time. Each investigating agency (law enforcement or social services) scheduled a CAC appointment in accordance with an open maltreatment case. At the beginning of each respondent’s appointment, Boughn provided them with an introduction and description of the study. This included the IRB approvals from the hospital and university, an explanation of the informed consent and protected health information (PHI) authorization, and assent forms. Respondents aged 12 and older were asked to read and review the informed consent document with their legal guardian; respondents aged from 8 to 11 were provided an additional assent document to read. Respondents were informed they could stop the study at any time. After each respondent and legal guardian consented, respondents proceeded with their CAC appointment.

Typical CAC appointments consisted of a forensic interview, at times a medical exam, and administration of the TSCC-SF to determine referral needs. After these steps were completed, Boughn administered the PMI to those who agreed to participate in this research study. Following the completion of the TSCC-SF, respondents were verbally reminded of the study and asked if they were still willing to participate by completing the PMI. Willing respondents completed the PMI; afterward, Boughn asked respondents if they were comfortable leaving the assessment room. In the event the respondent voiced additional concerns of maltreatment during the PMI administration, Boughn made a direct report to the respondent’s investigator (i.e., law enforcement officer or social worker assigned to the respondent’s case).

Boughn accessed each respondent’s completed TSCC-SF from their electronic health record in accordance with the PHI authorization and consent after the respondent’s appointment. Data completed on the TSCC-SF allowed Boughn to gather information related to sexual concerns, suicidal ideation, and trauma symptomology. Data gathered from the TSCC-SF were examined with each respondent’s PMI responses.

Results. Respondents were 21 children (15 female, six male) with age ranges from 8 to 17 years with a median age of 12 years. Respondents described themselves as White (47.6%), Biracial (14.2%), Multiracial (14.2%), American Indian/Alaskan Native (10.0%), Black (10.0%), and Hispanic/Latino (5.0%). CM allegations for the respondents consisted of allegations of sexual abuse (86.0%), physical abuse (10.0%), and neglect (5.0%).

Every respondent’s responses were included in the analyses to ensure all maltreatment situations were considered. The reliability of the PMI observed in the pilot sample (N = 21) demonstrated high internal consistency with all 16 initial items (α = .88). The average total score on the PMI in the pilot was 13.29, with respondents’ scores ranging from 1 to 30. A Pearson correlation indicated total scores for the PMI and General Trauma Scale scores (reported on the TSCC-SF) were significantly correlated (r = .517, p < .05).

Study 2: Full Testing of the PMI

The next phase of research proceeded with the collection of a larger data sample (N = 166) to explore the item construct validity and internal reliability (Siyez et al., 2020). Study procedures, data collection, and data storage followed in the pilot study were also implemented with the larger sample. Boughn maintained tracking of respondents who did not want to participate in the study or were unable to because of cognitive functioning level, emergency situations, and emotional dysregulation concerns.

Sample

Based on a power analysis performed using the Raosoft (2004) sample size calculator, the large sample study required a minimum of 166 respondents for statistical significance (Ali, 2012; Heppner et al., 2016). The sample size was expected to account for a 10% margin of error and a 99% confidence level. The calculation of a 99% confidence interval was used to ensure the number of respondents could effectively represent the population accessed within the CAC based on the data from the CM Report (DHHS, 2018). Large sample population data was gathered between September 2018 and May 2019.

Measures

The PMI and TSCC-SF were also employed in Study 2 because of their successful implementation in the pilot. Administration of the TSCC-SF ensured a normed and standardized measure could aid in providing context to the information gathered on the PMI. No changes were made to the PMI or TSCC-SF measures following the review of procedures and analyses in the pilot.

Procedures

Recruitment and data collection/analyses processes mirrored that of the pilot study. Voluntary respondents were recruited at the CAC during their scheduled appointments. Respondents completed an informed consent, child assent, PHI authorization form, TSCC-SF, and PMI. Following the completion of data collection, Boughn completed data entry in the electronic health record to de-identify and analyze the results.

Results

Demographics

All data were analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 24 (SPSS-24). Initial data evaluation consisted of exploration of descriptive statistics, including demographic and criteria-based information related to respondents’ identities and case details. Respondents were between 8 to 17 years of age (M = 12.39) and primarily female (73.5%, n = 122), followed by male (25.3%, n = 42). Additionally, two respondents (n = 2) reported both male and female gender identities. Racial identities were marked by two categories: White (59.6%, n = 99) and Racially Diverse (40.4%, n = 67) respondents. The presenting maltreatment concerns and the child’s relationship to the offender are outlined in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively.

Reliability and Validity of the PMI

The reliability of the PMI observed in its implementation in Study 2 (N = 166) showed even better internal consistency with all 16 initial items (α =.91) than observed in the pilot. Using the Spearman-Brown adjustment (Warner, 2013), split-half reliability was calculated, indicating high internal reliability (.92). Internal consistencies were calculated using gender identity and age demographic variables (see Table 3).

Table 1

Child Maltreatment Allegation by Type (N = 166)

| Allegation |

f |

Rel f |

cf |

% |

| Sexual Abuse |

113 |

0.68 |

166 |

68.07 |

| Physical Abuse |

29 |

0.17 |

53 |

17.47 |

| Neglect |

14 |

0.08 |

24 |

8.43 |

| Multiple Allegations |

6 |

0.04 |

10 |

3.61 |

| Witness to Violence |

3 |

0.02 |

4 |

1.81 |

| Kidnapping |

1 |

0.01 |

1 |

0.60 |

Note. Allegation type reported at initial appointment scheduling

Table 2

Identified Offender by Relationship to Victim (N = 166)

| Offender Relationship |

f |

Rel f |

cf |

% |

| Other Known Adult |

60 |

0.36 |

166 |

36.14 |

| Parent |

48 |

0.29 |

106 |

28.92 |

| Other Known Child (≤ age 15 years) |

15 |

0.09 |

58 |

9.04 |

| Sibling-Child (≤ age 15 years) |

10 |

0.06 |

43 |

6.02 |

| Unknown Adult |

9 |

0.05 |

33 |

5.42 |

| Step-Parent |

8 |

0.05 |

24 |

4.82 |

| Multiple Offenders |

6 |

0.04 |

16 |

3.61 |

| Grandparent |

6 |

0.04 |

10 |

3.61 |

| Sibling-Adult (≥ age 16 years) |

3 |

0.02 |

4 |

1.81 |

| Unknown Child (≤ age 15 years) |

1 |

0.01 |

1 |

0.60 |

Note. Respondent knew the offender (n =156); Respondent did not know offender (n =10)

Table 3

Internal Consistency Coefficients (α) by Gender Identity and Age (N = 166)

| Gender |

n |

α |

M |

SD |

| Female |

122 |

0.90 |

13.2 |

9.1 |

| Male |

42 |

0.94 |

13.5 |

11.0 |

| Male–Female |

2 |

0.26 |

8.5 |

2.5 |

| Age |

|

|

|

|

| 8–12 |

83 |

0.92 |

12.75 |

10.06 |

| 13–17 |

83 |

0.90 |

13.69 |

9.01 |

Note. SD = Standard Deviation; M = Mean

Respondents’ Demographic Characteristics and PM Experiences

For Research Question (RQ) 1 and RQ2, descriptive data were used to generate frequencies and determine the impact of demographic characteristics on average PMI score. To explore this further in RQ1, one-way ANOVAs were completed for the variables of age, gender, racial identity, allegation type, and offender relationships. No significant correlations were found between demographic variables and the PMI items. On average, respondents reported a frequency score of 13.5 (M = 13.5, SD = 9.5) on the PMI. Eight respondents (5%) endorsed no frequency of PM while 95% (N = 158) experienced PM.

Co-Occurrence of PM With Other Forms of Maltreatment

For RQ3, frequency and descriptive data were generated, revealing average age rates of PM reported by maltreatment type. Varying sample representations were discovered in each form of maltreatment (see Table 4). Clear evidence was found that PM co-occurs with each form of maltreatment type; however, how each form of maltreatment interacts with PM is currently unclear given the multiple dimensions of each maltreatment case including, but not limited to, severity, frequency, offender, and victim characteristics.

Table 4

Descriptive and Frequency Data for Co-Occurrence of PM (N = 166)

| Allegation |

n |

M |

SD |

95% CI |

| Sexual Abuse |

113 |

13.04 |

9.01 |

[11.37, 14.72] |

| Physical Abuse |

29 |

12.45 |

10.53 |

[8.44, 16.45] |

| Neglect |

14 |

14.57 |

12.16 |

[7.55, 21.60] |

| Multiple Allegations |

5 |

17.40 |

8.88 |

[6.38, 28.42] |

| Witness to Violence |

3 |

7.67 |

5.03 |

[–4.84, 20.17] |

| Kidnapping |

1 |

n/a |

n/a |

Missing |

Note. CI = Confidence Interval; SD = Standard Deviation; M = Mean; n/a = not applicable

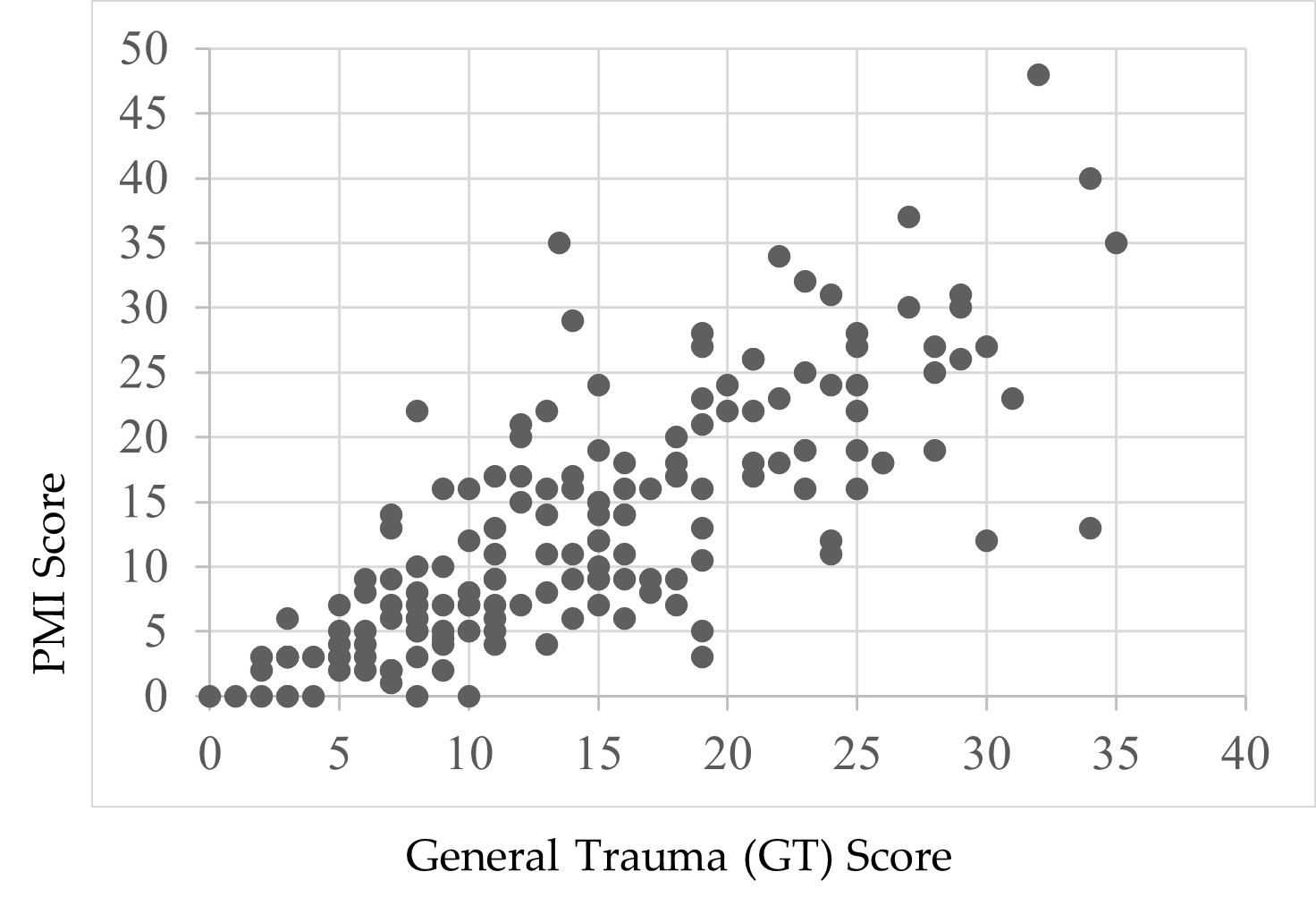

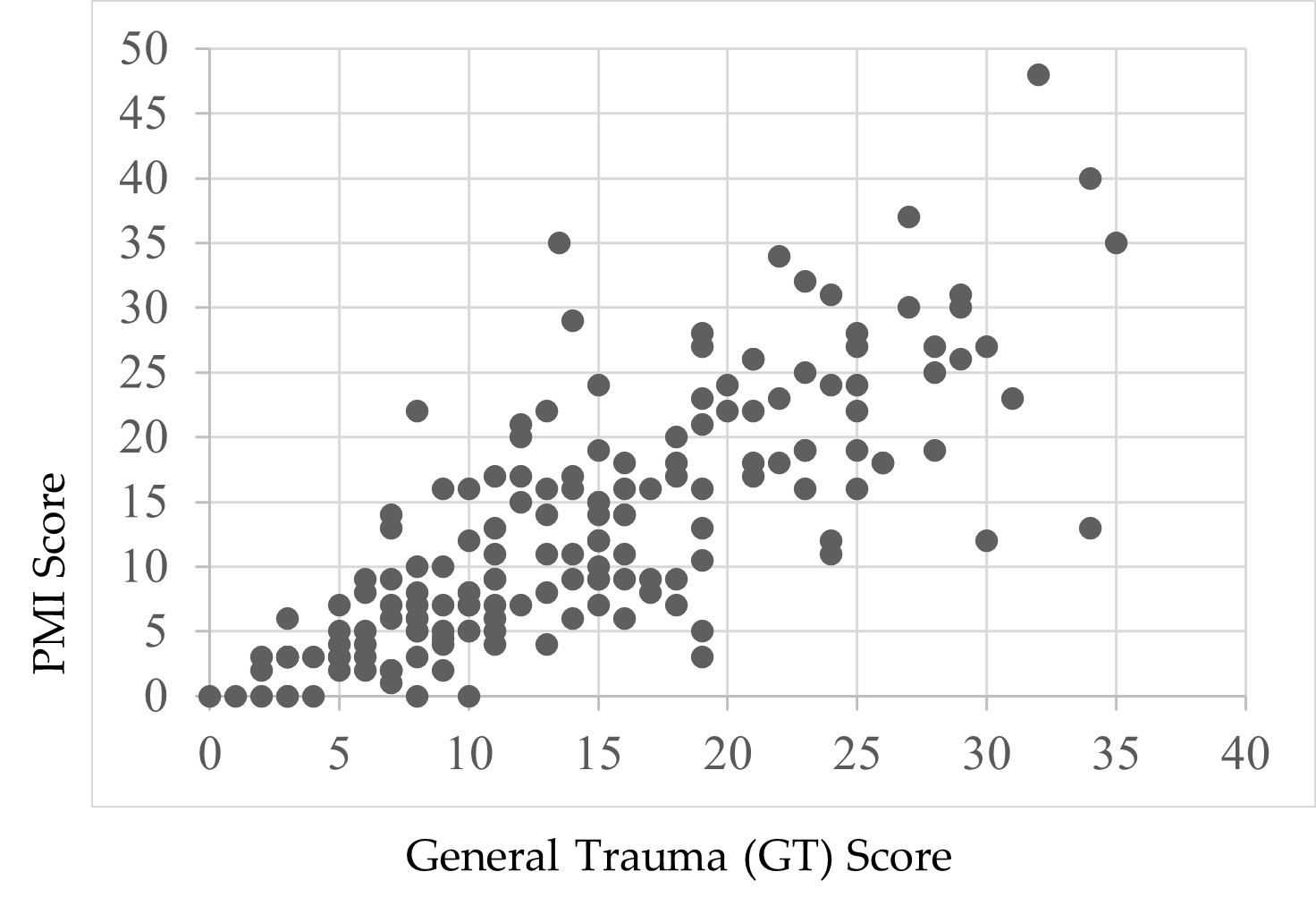

PM Frequency and General Trauma Symptoms

For RQ4, Pearson’s correlation was used to calculate frequency score relationships between the PMI and TSCC-SF. There was a statistically significant relationship between the PMI and total frequency of general trauma symptoms on the TSCC-SF [r(164) = .78, p < .01, r² = .61] (Sullivan & Feinn, 2012). Cohen’s d, calculated from the means for each item as well as the pooled standard deviation, indicated a small effect relationship (d = .15) between general trauma and PMI frequencies (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Correlation Between PMI and TSCC-SF General Trauma Subscale