Dec 16, 2020 | Volume 10 - Issue 4

Jennie Ju, Rose Merrell-James, J. Kelly Coker, Michelle Ghoston, Javier F. Casado Pérez, Thomas A. Field

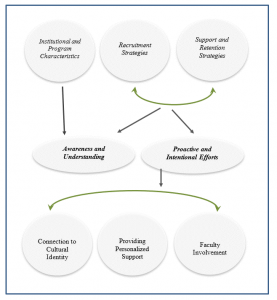

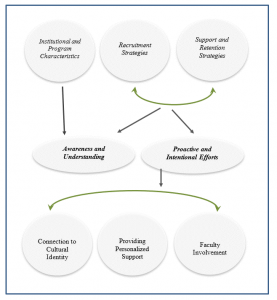

Few models exist that inform how counselor education programs proactively address the gap between diverse student needs and effective support. In this study, we utilized grounded theory qualitative research to gain a better understanding of how 15 faculty members in doctoral counselor education and supervision programs reported that their departments responded to the need for recruiting, retaining, and supporting doctoral students from underrepresented racial minority backgrounds. We also explored participants’ reported successes with these strategies. A framework emerged to explain the strategies that counselor education departments have implemented in recruiting, supporting, and retaining students from underrepresented racial minority backgrounds. The main categories identified were: (a) institutional and program characteristics, (b) recruitment strategies, and (c) support and retention strategies. The latter two main categories both had the same two subcategories, namely awareness and understanding, and proactive and intentional efforts. The latter subcategory had three subthemes of connecting to cultural identity, providing personalized support, and faculty involvement.

Keywords: underrepresented racial minority, recruitment, retention, counselor education, doctoral

For the past several years, doctoral counselor education and supervision (CES) programs accredited by the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) have experienced a greater enrollment of students from diverse backgrounds (CACREP, 2014, 2015). According to the CACREP Vital Statistics report (2018), two-fifths of doctoral students have a diverse racial or ethnic identity. This stands in contrast to the less than 30% of full-time faculty in CACREP-accredited programs who identify as having a diverse racial or ethnic identity. In 2012, the total doctoral-level enrollment in CACREP institutions was 2,028, where 37% of the students were from racially or ethnically diverse backgrounds (CACREP, 2014). Enrollment increased to 2,561 in 2017, with 1,016 students from racially or ethnically diverse communities, which translates to 39.7% of total enrollment (CACREP, 2018).

Accompanying this trend is a growing awareness that diverse doctoral students in counseling and related disciplines are not receiving adequate support and preparation to succeed (Barker, 2016; Henfield et al., 2011; Hollingsworth & Fassinger, 2002; Zeligman et al., 2015). CACREP-accredited programs are charged with making a “continuous and systematic effort to attract, enroll, and retain a diverse group of students and to create and support an inclusive learning community” (CACREP, 2016, section 1.K.). Yet few models exist that inform how CES programs proactively address the gap between diverse student needs and effective support. Literature is limited on this topic. Little is known about effective and comprehensive structures for recruiting, supporting, and retaining CES doctoral students from underrepresented minority (URM) backgrounds that take into consideration CACREP standards, student needs, economics, sociocultural barriers, and student opportunities.

In this study, we used Federal definitions of URM status in higher education to guide our inquiry. A section of the U.S. Code pertaining to minority persons provides the following definition for minority, and it is the one we chose to use in our study: “American Indian, Alaskan Native, Black (not of Hispanic origin), Hispanic (including persons of Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, and Central or South American origin), Pacific Islander, or other ethnic group” (Definitions, 20 U.S.C. 20 § 1067k, 2020). This definition is important to higher education, as it is used by institutions to allocate funding for URM students. We note here that cultural diversity also spans other aspects of minority status, such as gender identity, sexual/affectional identity, and ability/disability status, among others. We restricted the focus of this study to exploring racial identity pertinent to URM status, following the U.S. Code definition.

Recruitment of Doctoral Students From URM Backgrounds

Understanding the diversification of doctoral students in CES programs begins by first considering effective methods for recruitment used by those programs. Recruitment of CES doctoral students of color may necessitate intentional and active approaches, such as building personal connections in the community and family (Hipolito-Delgado et al., 2017; McCallum, 2016). CES doctoral programs might consider recruitment not as a yearly endeavor, but a long-term, day-to-day strategy. Early exposure, responsiveness to student needs (e.g., financial needs), commitment to diversity (e.g., hiring and retaining faculty members from diverse backgrounds), community relationships, and program location have all been identified as important factors to consider in the extant literature.

Early Exposure and Recruitment

Programs can promote more representative recruitment through earlier exposure to the disciplinary field and community connections (Grapin et al., 2016; Hipolito-Delgado et al., 2017; McCallum, 2016). Introducing the possibility of pursuing doctoral studies in CES during the high school and undergraduate experience can increase student familiarity with the profession and may promote their long-term attention to the field (Luedke et al., 2019; McCallum, 2016). McCallum (2015, 2016) found that early familial and social messages about the low viability of doctoral studies was a deterrent among African American students and that mentorship and exposure to doctoral careers by professionals can help renew interest. Many undergraduate students from culturally diverse backgrounds lack opportunities to learn and develop ownership of doctoral-level professions and in some cases lack knowledge that those professions even exist (Grapin et al., 2016; Luedke et al., 2019).

Responsiveness to Needs and Commitment to Diversity

To successfully recruit doctoral students from culturally diverse backgrounds, CES programs need to be responsive to potential students’ needs. In fact, a program’s commitment to diversity and the demonstration of that commitment through student and faculty representation have been found to be highly influential factors in applicants’ decisions to enter a doctoral program (Foxx et al., 2018; Grapin et al., 2016; Zeligman et al., 2015). An additional aspect of this responsiveness in recruitment is the program’s ability to ensure and provide financial support to incoming students (Dieker et al., 2013; Proctor & Romano, 2016). Given the unique barriers experienced by culturally diverse communities throughout the educational system, doctoral programs can be prepared to compensate for some of these obstacles through financial and academic support.

Community Relationships and Program Location

In keeping with recruitment as a long-term endeavor, research has found that community relationships and program location are essential when recruiting doctoral students from culturally diverse backgrounds (Foxx et al., 2018; Hipolito-Delgado et al., 2017). CES programs can look to build relationships with their local culturally diverse communities and recruit from those communities, rather than looking nationally for their doctoral students (Foxx et al., 2018; Hipolito-Delgado et al., 2017). Proctor and Romano (2016) found that proximity to representative communities and applicants’ support systems had a significant impact on their decision to enter doctoral programs. Community connections also offered more opportunities to clarify admission requirements for interested students, a barrier for many first-generation students (Dieker et al., 2013; Hipolito-Delgado et al., 2017).

Support and Retention of Culturally Diverse Doctoral Students

Once admitted to a doctoral program in CES, program faculty are required by the CACREP (2015) standards to make a continuous and systematic effort to not only recruit but also to retain a diverse group of students. To do so, faculty should be attentive to both common and unique personal and social challenges, experiences of marginalization and isolation, and acculturative challenges that students from URM backgrounds may face.

Personal and Social Challenges

Students from URM backgrounds have faced ongoing challenges with their ability to establish a clear voice and ethnic identity in predominately Euro-American CES programs (Baker & Moore, 2015; González, 2006; Guillory, 2009; Lerma et al., 2015). This phenomenon has been written about for decades (Lewis et al., 2004). Lewis et al. (2004) described the lived experiences of African American doctoral students at a predominantly Euro-American, Carnegie level R1 research institution. Key themes that emerged included feelings of isolation, tokenism, difficulty in developing relationships with Euro-American peers, and learning to negotiate the system. Further review of the literature found consistent challenges across diverse students, especially with establishing voice and ethnic identity (Baker & Moore, 2015; González, 2006; Lerma et al., 2015). Guillory (2009) noted that the level of difficulty American Indian students will face in college depends in large measure on how they see and use their ethnic identity. Utilizing a narrative inquiry approach, Hinojosa and Carney (2016) found that five Mexican American female students experienced similar challenges in maintaining their ethnic identities while navigating doctoral education culture.

Challenges of Marginalization and Isolation

Marginalization and isolation were additional common themes across diverse groups. Blockett et al. (2016) concluded that students experience marginalization in three areas of socialization, including faculty mentorship, professional involvement, and environmental support. Other researchers have also concluded that both overt and covert racism is a contributing factor to marginalization in the university culture (Behl et al., 2017; González, 2006; Haizlip, 2012; Henfield et al., 2013; Interiano & Lim, 2018; Protivnak & Foss, 2009). Study themes also indicated that students often expressed frustration from tokenism in which they felt expectations to represent the entire race during doctoral programs (Baker & Moore, 2015; Haizlip, 2012; Henfield et al., 2013; Lerma et al., 2015; Woo et al., 2015). Henfield et al. (2011) investigated 11 African American doctoral students and found that the challenges included negative campus climates regarding race, feelings of isolation, marginalization, and lack of racial peer groups during their graduate education. Similarly, using critical race theory to examine how race affects student experience, Henfield et al. (2013) found African American students experienced a lack of respect from faculty because of their racial and ethnic differences. Students who had previously studied at historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) or Hispanic serving institutions (HSIs) reported that the lack of racial/ethnic diversity representation during doctoral study in predominantly White institutions (PWIs) contributed to their experience of stress, anxiety, and irritation (Henfield et al., 2011, 2013).

Culture and Acculturation Challenges

Collectivity and community seem to be consistent values that doctoral students from URM backgrounds have expressed as missing or not understood by faculty (González, 2006; Lerma et al., 2015). For example, faculty may not understand familia, a Latinx student’s obligation to family (González, 2006; Lerma et al., 2015). Several authors have reported that culturally diverse doctoral students experience difficulty adjusting to a curriculum or program that values a Eurocentric individualist form of counseling (Behl et al., 2017; Interiano & Lim, 2018; Woo et al., 2015).

International students also experience similar anxiety and stress during their doctoral studies in the United States. In addition to adjusting to speaking and writing in a language that may not be their primary language, their supervision skills and clinical abilities can be questioned by Euro-American supervisees despite international students having advanced training and supervisory status (Behl et al., 2017). Interiano and Lim (2018) used the term “chameleonic identity” (p. 310) to describe foreign-born doctoral students’ attempts to adapt to the Euro-American cultural context of their CES programs. They posited that international students experienced a sense of conflict, loss, and grief associated with the pressure to adopt cultural norms embedded in Euro-American counseling and higher education in the United States.

Strategies to Support and Retain Culturally Diverse Doctoral Students

To address these stressors and barriers to persistence in doctoral studies, faculty members can employ several strategies to support and retain students from culturally diverse backgrounds, such as mentorship, advising, increasing faculty diversity, understanding students’ cultures, and offering student support services.

Mentorship

Some scholars recommend intentional utilization of mentorship as a strategy for improving retention and graduation rates of diverse students in higher education (Evans & Cokley, 2008; Rogers & Molina, 2006). Chan et al. (2015) defined mentoring relationships as a “one-to-one ongoing connection between a more experienced member (mentor) and less experienced member (protégé) that is aimed to promote the professional and personal growth of the protégé through coaching, support and guidance” (p. 593). Chan and colleagues added that mentoring can involve transferring needed information, feedback, and encouragement to the protégé as well as providing emotional support.

Zeligman and colleagues (2015) indicated that mentoring impacts both the recruitment and the retention of doctoral students from URM backgrounds. The quality and significance of mentoring relationships and participants’ connection with faculty members during a doctoral program seems to influence choice in continuing doctoral study for URM students (Baker & Moore, 2015; Protivnak & Foss, 2009). Blackwell (1987) noted that the most powerful predictor of enrollment and graduation of African American students at a professional school was the presence of an African American faculty member serving as the student’s mentor.

Although a powerful tool for recruiting and retaining diverse doctoral students, mentoring can also create retention issues if inadequate or problematic. Students may receive ambiguous answers to advising questions and may not receive support when life circumstances interfere with study (Baker & Moore, 2015; Henfield et al., 2013; Interiano & Lim, 2018). In such situations, some students may seek other faculty mentors within the department (Baker & Moore, 2015; Henfield et al., 2013; Interiano & Lim, 2018) or may specifically establish mentoring relationships with faculty from diverse cultural backgrounds to receive greater support for their experience of being a person of color (González, 2006; Woo et al., 2015; Zeligman et al., 2015). Diverse students may also seek mentors from outside of their doctoral program. Woo and colleagues (2015) found that international students selected professional counseling mentors from their home community that they considered to be caring and nonjudgmental of their doctoral work in comparison to faculty supervisors they felt were neither culturally sensitive nor supportive of international students.

Because of an existing disparity in the availability of African American counselor educators and supervisors who can serve as mentors to African American doctoral counseling students, Euro-American counselor educators and supervisors can provide mentorship support to underrepresented African American doctoral students. Brown and Grothaus (2019) conducted a phenomenological study with 10 African American doctoral counseling students. The authors found that trust was a primary factor in establishing successful cross-racial relationships, and that African American students could benefit from “networks of privilege” (p. 218) during cross-racial mentoring. The authors also found that if issues of racism and oppression are not addressed, it can interfere with establishing mentoring relationships.

Establishing same-race, cross-race, and/or cultural community affiliations provides support to culturally diverse doctoral students. In addition, increasing faculty diversity can be a viable measure to support and retain diverse doctoral students.

Increasing Faculty Diversity

The presence of diverse faculty members in CES has been discussed in the literature as a positive element in the recruitment, support, and retention of diverse doctoral students (Henfield et al., 2013; Lerma et al., 2015; Zeligman et al., 2015). Henfield and colleagues (2013) emphasized the need to proactively recruit and retain African American CES faculty to attract, recruit, and retain African American CES doctoral students. Recruiting and retaining faculty members from URM backgrounds requires intentional effort. Ponjuan (2011) suggested the development of mentoring policies that establish Hispanic learning communities and improve overall departmental climate as efforts to help increase the number of Latinx faculty at an institution. The next section discusses the relational significance of having counselor educator mentors who share cultural backgrounds and worldviews.

Understanding of Students’ Culture

Lerma et al. (2015) recommended that doctoral faculty in CES programs be responsive to both the professional and personal development of their students. One area of dissonance for doctoral students from URM backgrounds involves differences in cultural worldview. Marsella and Pederson (2004) posited that “Western psychology is rooted in an ideology of individualism, rationality, and empiricism that has little resonance in many of the more than 5,000 cultures found in today’s world” (p. 414). Ng and Smith (2009) found that international counselor trainees, particularly those from non-Western nations, struggle with integrating Eurocentric theories and concepts into the world they know. This presents opportunities for counselor educators to intentionally search for appropriate pedagogies and to critically present readings and other media that portray the multicultural perspective (Goodman et al., 2015).

Counseling departments can promote, facilitate, and value a multicultural orientation when focusing on student success and development. Lerma et al. (2015) and Castellanos et al. (2006) emphasized the need to understand the importance of family and peer support among Latinx students and faculty, specifically in recreating familia in the academic environment to help increase resilience. When working with African American students, Henfield et al. (2013) recommended that faculty should possess an understanding and respect of African American culture and be more “cognizant of how a history of oppression may influence students’ perception, behavior, and nonbehavior” (p. 134). Faculty members should also possess an understanding of student financial difficulties and potential knowledge gaps in preparation for graduate school (González, 2006; Zeligman et al., 2015).

Student Support Services

Another effective area of support for doctoral students from diverse backgrounds is student-based services. These services include broader institutionally based resources, student-guided groups or activities, and community-based efforts. Institutional resources that seem to hold promise in increasing support for and the potential success of diverse students include race-based organizations (Henfield et al., 2011). Peer support has been consistently identified as an important factor in doctoral student persistence (Chen et al., 2020; Henfield et al., 2011; Rogers & Molina, 2006). Student-centered organizations can effectively provide a sense of belonging and an environment that facilitates peer support among those with shared interests on campus (Rogers & Molina, 2006). Henfield et al. (2011) found that African American students sought collaborative support through race-based campus organizations and with students who share similar backgrounds and interests. Multicultural-based, student-centered organizations and events are resources that institutions utilize as active support for multicultural individuals that contribute to “sustaining diverse students to reach the finish line of graduation with a strong foundation from which to launch their counseling career” (Chen et al., 2020, p. 10).

Chen et al. (2020) and Behl et al. (2017) have both reported that writing centers are an important support for international students as well as students from refugee, immigrant, and underprivileged communities. Ng (2006) reported that counseling students from non–English-speaking countries often experience challenges related to English proficiency. Chen et al. (2020) added that tutoring in writing is critical for students who come from cultures that are unaccustomed to the formal use of writing styles (e.g., APA style). Furthermore, helping international students understand classroom norms and culture through an orientation as part of the onboarding process can be a preventive support (Behl et al., 2017).

Purpose of the Present Study

The CACREP standards have created expectations and requirements for counseling programs to recruit, retain, and support students from diverse backgrounds. There now exists a wide swath of literature that has reported a variety of efforts toward these goals (Baker & Moore, 2015; Evans & Cokley, 2008; Rogers & Molina, 2006; Woo et al., 2015). Yet at the time of writing, there is not a clearly articulated path for CES programs to follow with regard to these efforts. For example, there is currently no information available regarding which strategies are more successful or easier to implement than others. This study aimed to address this gap in knowledge for how to attract, support, and retain students from diverse backgrounds in CES doctoral programs. The purpose of our study was to explore: (a) strategies doctoral programs use to recruit, retain, and support underrepresented doctoral students from diverse backgrounds, and (b) the level of success these programs have had with their implemented strategies.

Methodology

Throughout the study, we were grounded by a shared belief in constructivist philosophy that participants’ realities are socially co-constructed, and therefore, all responses are valued regardless of frequency. From this philosophical position, we chose to approach the topic using a qualitative framework (Lincoln & Guba, 2013). Grounded theory was selected because it utilizes a systematic and progressive gathering and analysis of data, followed by grounding the concepts in data that accurately describe the participants’ own voices (Charmaz, 2014; Corbin & Strauss, 2015). This approach allows the integration of both the art and science aspects of inquiry while supporting systematic development of theoretical constructs that promote richer comprehension and explanation of social phenomena (Charmaz, 2014; Corbin & Strauss, 2015). Through the grounded theory approach, we hoped to establish an emergent framework to explain practice and provide recommendations for CES programs striving to support diverse doctoral students.

This study was part of a larger comprehensive qualitative study based on the basic qualitative research design described by Merriam and Tisdell (2016) that examined a series of issues pertinent to doctoral counselor education. Preston et al. (2020) described the larger qualitative project that involved the collection and analysis of in-depth qualitative interviews with 15 doctoral-level counselor educators. This article focuses on the analysis of interview data gathered through two of the interview questions: 1) Which strategies has your program used to recruit underrepresented students from diverse backgrounds? How successful were those? and 2) Which strategies has your program used to support and retain underrepresented students from diverse backgrounds? How successful were those?

Researcher Positioning, Role, and Bias

The last author utilized the etic position, which is through the perspective of the observer, to conduct all interviews with selected participants. Approaching the interview process around the topic of doctoral-level counselor education through the etic status was important because the author had not worked in a doctoral-level CES program previously but has been a member of the counselor education community.

The situational context was composed of the researchers’ and participants’ experiences and perceptions, the social environment, and the interaction between them (Ponterotto, 2005). Therefore, we engaged in reflexivity to increase self-awareness of biases related to this topic (Corbin & Strauss, 2015). This required continual examination of the potential influence that identified biases may have on the research process. In keeping with the standard of reflexivity, we recorded our personal experiences as they related to the research questions with the use of memoing to bracket potential biases throughout the coding and analysis process.

All members of the research team are from CACREP-accredited institutions in the Western and Eastern parts of the United States. The coding team consisted of the first four authors. The fifth author contributed to writing the manuscript, and the sixth author conducted the interviews as part of the larger study and assisted in writing sections of the methodology. All four coding team members had previously been doctoral students in a CES program, though only one of the coding team members had ever worked in a CES doctoral program as a full-time faculty member. This person thus had emic positioning, while other team members held etic positioning.

Four of the five members of the coding team were from diverse backgrounds themselves and were influenced by their personal experiences as doctoral students. Two members of the coding team identified as cisgender, heterosexual African American females. One member identified as a cisgender, heterosexual Asian American female and another as a cisgender, heterosexual Euro-American female. The coding team members were aware of potential biases around expectations toward the programs discussed in the transcripts and recognized the need to closely examine personal perceptions and understanding of the interview data.

Two coding team members observed the lack of racial/ethnic diversity at the counseling programs where they currently work. They experienced Eurocentric, non–culturally responsive methods of support and development that led them to recognize the potential bias of shared experience with multicultural participants. One coding team member was Euro-American and was a part of an all Euro-American doctoral cohort. The program they attended had an all Euro-American faculty and she wondered whether the predominantly Euro-American participants in this study had an understanding of the challenges of diverse students. Having taught in doctoral programs, this researcher was aware of potential biases around types of universities that might be successful in recruiting but less so in retaining diverse students.

Participants

Participants were selected based on the following study design criteria: 1) current full-time core faculty members in CES, and 2) currently working in a doctoral-level CES program that is accredited by CACREP. At the time of writing, there were 85 CACREP-accredited doctoral CES programs in the United States (CACREP, 2019). Purposeful sampling was used to identify and recruit participants who had experiences working in doctoral-level counselor education (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). Information-rich cases were sought to understand the phenomenon of interest.

Maximum variation sampling was also employed for the purposes of understanding the perspectives of counselor educators from diverse backgrounds with regard to demographic characteristics and program characteristics and to avoid premature saturation (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). Based on the belief that counselor educator perspectives may differ by background, the research team used the following criteria to select participants: (a) racial and ethnic self-identification; (b) gender self-identification; (c) length of time working in doctoral-level CES programs; (d) Carnegie classification of the university where the participant was currently working (The Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education, 2019); (e) region of the counselor education program where the participant was currently working, using regions commonly defined by national counselor education associations and organizations; and (f) delivery mode of the counselor education program where the participant was currently working (e.g., in-person, online; Preston et al., 2020).

The 15 study participants belonged to separate doctoral-level CES programs, with no more than one participant representing each program. The sample was composed of 11 participants (73.3%) who self-identified as White, with multiracial/multiethnic (n = 1, 6.7%), African American (n = 1, 6.7%), Asian (n = 1, 6.7%), and Latinx ethnic backgrounds (n = 1, 6.7%) also represented. Seven participants self-identified as female (46.7%), eight participants as male (53.3%), and none identified as non-binary or transgender. The majority of participants identified as heterosexual (n = 14, 93.3%), with one participant (6.7%) identifying as bisexual.

Participants’ experience as faculty members averaged full-time work for 19.7 years (SD = 9.0 years) and a median of 17 years, with a range from 4 to 34 years. For most of those years, participants worked in doctoral-level CES programs (M = 17.3 years, SD = 9.2 years, Mdn = 16 years), ranging from 3 to 33 years. More than half of participants (n = 9, 60%) spent their entire careers working in doctoral-level CES programs. Geographic distribution of the programs where participants worked were as follows: eight belonged to the Southern region (53.3%); two each (13.3%) belonged to the North Atlantic, North Central, and Western regions; and one program (6.7%) belonged to the Rocky Mountain region. Twelve participants (80%) were working in brick-and-mortar programs, and three participants (20%) were working in online or hybrid programs. With regard to Carnegie classification representation, nine (60%) were working at Doctoral Universities – Very High Research Activity (i.e., R1) institutions, two (13.3%) were working at Doctoral Universities – High Research Activity (i.e., R2) institutions, and four (26.7%) were working at universities with the Master’s Colleges and Universities: Larger Programs designation (The Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education, 2019; Preston et al., 2020).

Procedure

After receiving approval from the last author’s IRB, the last author used the CACREP (2018) website directory to identify and recruit doctoral-level counselor educators who worked at the CACREP-accredited CES programs. Recruitment emails were sent to one faculty member at each of the 85 accredited programs. Fifteen of the 34 faculty (40% response rate) who responded were selected to participate on the basis of maximal variation.

Interview Protocol

Each interview began with demographic questions that addressed self-identified characteristics such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual/affectional orientation, years as a faculty member, years working in doctoral-level CES programs, number of doctoral programs the participant had worked in, and regions of the programs in which the counselor educator had worked. A series of eight in-depth interviews followed to address the research questions of the larger qualitative study. Interview questions developed in accordance with Patton’s (2014) guidelines were open-ended, as neutral as possible, avoided “why” questions, and were asked one at a time in a semi-structured interview protocol, with sparse follow-up questions salient to the main questions to ensure understanding of participant responses. Adhering to the interview protocol as outlined in Appendix A helped to ensure that data was gathered for each research question to the highest extent possible. Participants received the interview questions ahead of time upon signing the informed consent agreement. A pilot of the interview protocol was conducted with a faculty member in a doctoral-level CES program prior to commencing the study.

The interviews lasted approximately 60 minutes and were recorded using the Zoom online platform. One exception was an interview that occurred in-person during a professional conference and thus was recorded via a Sony digital audio recorder. All demographic information and recordings were assigned an alphabetical identifier known only to the last author and were blinded to subsequent transcribers and coders.

Data Analysis

Data analysis, as outlined by Corbin and Strauss (2015), employs the techniques of coding interview data to derive and develop concepts. In the initial step of open coding, the primary task is to “break data apart and delineate concepts to stand for blocks of raw data” (Corbin & Strauss, 2015, p. 197). During this step, the coding team sought to identify a list of significant participant statements about how they and their department perceive, value, and experience the responsibility of recruiting, retaining, and supporting underrepresented cultural groups. We met to code the first three of 15 transcripts together via Zoom video platform. The task of identifying codes included searching for data that was salient to the research questions and engaging in constant comparison until reaching saturation (Corbin & Strauss, 2015). We maintained a master codebook of participant statements that the team decided were relevant, then added descriptions and categories to the codes. Utilizing this same strategy, the remaining 12 transcripts were coded in dyads to make sure the coding team was not overlooking pertinent information.

When discrepancies occurred, the coding team utilized the following methods to resolve them:

(a) checking with each other for clarification and understanding of each person’s view on the code, (b) reviewing previous and subsequent lines for context, (c) slowing down the pace of coding to allow space for reflection on the team members’ thoughts and feeling about a code, (d) considering the creation of a new code if one part of the statement added new data that was not covered in the first part of the statement, and (e) referring back to the research questions to determine relevance of the statement. Discrepancies in coding were questions around statements that: (a) were vague, (b) contained multiple codes, (c) were similarly phrased, (d) reflected a wish rather than an action on the part of the program, and (e) presented interesting information about the participant’s program but did not address the research question.

The subsequent step of axial coding involved the task of relating concepts and categories to each other, from which the contexts and processes of the phenomena emerge (Corbin & Strauss, 2015). The researchers then framed emerging themes and concepts to identify higher-level concepts and lower-level properties as well as delineated relationships between categories until saturation was reached. In the step of selective coding, the researchers engaged in an ongoing process of integrating and refining the framework that emerged from categories and relationships to form one central concept (Strauss & Corbin, 1998).

Trustworthiness

Standards of trustworthiness were achieved by incorporating procedures as outlined by Creswell et al. (2007) and Merriam and Tisdell (2016). The strategies included enhancing credibility through clarification of researcher bias to illustrate the researchers’ position as well as identifying a priori biases and assumptions that could potentially impact our inquiry. In addition, the research team members were from different counselor education programs, which contributed to moderating bias in coding and analysis. In an attempt to avoid interpreting data too early during the coding process, the researchers used emergent, in vivo, verbatim, line-by-line open coding. Furthermore, the interviewer intentionally chose not to participate in coding the data in order to minimize bias through being too close to the data. To promote consistency, the last author clearly identified and trained research teams associated with the larger study. The last author also used member checking and kept an audit trail of the process to enhance credibility. Purposive sampling and thick description were used to ensure adequate representation of perspectives and thus strengthen the transferability and dependability qualities of the study (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016).

Results

Implementing strategies that make a difference was the central concept in describing the process of CES faculty participants’ experience with recruiting and retaining diverse doctoral students. These strategies refer to programmatic steps that counselor educator interview participants had found to be effective in the recruitment, support, and retention of culturally diverse doctoral students. This central concept was composed of three progressive and interconnected categories, each with its own subcategories, properties, and accompanying dimensions. These three categories were institutional and program characteristics, recruitment strategies, and support and retention strategies. The three major categories shared the subcategory of awareness and understanding, while the recruitment strategies and support and retention strategies categories shared the subcategory of proactive and intentional efforts. The conceptual diagram of these categories and subcategories is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Conceptual Diagram of Strategies That Make a Difference in Recruiting and Supporting

Culturally Diverse Doctoral Students

Institutional and Program Characteristics

The category institutional and program characteristics refers to features that are a part of program identity. This category was significant, as it represents the backdrop for a unique set of conditions in which the participants experienced the limitations as well as strengths of the program environment. Institutional and program characteristics may be part of the institution’s natural setting that the faculty participant had little control over, such as geographic location, institution size, institution reputation, tuition cost, or demographic composition of the area in which the program was located. At times, these factors were helpful for recruitment purposes. One participant described how the program’s geographic location positively impacted the recruitment of prospective students, including diverse students: “We are the only doctoral program in the state, so I think that carries some clout.” Another participant added, “A lot of it is financial . . . They largely choose programs because they are geographically convenient, so they can work or be close to family. So, their choice is largely guided by economic and geographic factors.”

Institutional and program characteristics also included factors that influenced support and retention of diverse students through their doctoral journey. Characteristics mentioned as either a hindrance or a support for diverse students included: (a) presence of diverse faculty, visual representation, and student body; (b) supportive environment for diverse students; (c) faculty attitudes and dispositions which create either a welcoming or hostile sociocultural climate; (d) fellowship or scholarship monies intended for diverse students; (e) evidence of valuing of and commitment to diversity; (f) multicultural and social justice focused activities; and (g) faculty who share common research interests with their students. From this list, it was evident that doctoral students seemed best supported by program qualities and actions that communicated a valuing of and commitment to diversity.

Awareness and Understanding

Participants indicated awareness that the context in which the institution and program exist presents as either a hindrance or a benefit to diversity. For example, geographic location and demographic composition of the locality can pose a barrier to recruitment as one participant expressed: “Our university itself is not going to attract people. It is a very White community.” This participant understands that this means the program will need to develop specific recruitment efforts to mitigate this potential barrier to “show students that this is a program that would be welcoming and take proactive steps to do that.”

Participants also indicated an awareness that students can sense whether diversity-related issues will be given priority. One participant stated, “Students are really astute about getting a sense for how committed a department is to diversity. So, having tangible evidence there is a willingness to commit to diversity at the faculty level is super important.” Another participant shared, “Our interview process is a barrier . . . There can be some privileged White males who are highly, highly confrontational, and I don’t think that’s an appropriate recruitment style for sending a welcoming message to minority candidates.”

Recruitment Strategies

The second major category identified in the data, recruitment strategies, pertains to the process of developing and implementing plans for the primary purpose of attracting individuals from diverse backgrounds to apply and enroll in the program. The recruitment strategies category is composed of two subcategories that are shared with the support and retention strategies, namely awareness and understanding and proactive and intentional efforts.

Awareness and Understanding

Participants shared a variety of responses regarding their awareness and understanding of the importance of creating a diverse learning community. Some participants reported that their departments proactively sought to recruit underrepresented students, whereas others acknowledged that their departments made no such attempt. At times, this was due to the structure of recruiting at the university: “Our program doesn’t necessarily get involved in admissions that much . . . We have an admissions team, and they have a whole series of strategies in place.” At other times, participants reported that their program was unintentional about recruiting diverse students: “We don’t have any good strategy particularly. It’s accident, dumb luck and accident.” One participant experienced distress and confusion because of their program’s perceived misalignment with CACREP standards: “These are key standards for programs, and one that programs have struggled with, and we certainly have too.”

Proactive and Intentional Efforts

Participants reported engaging social resources such as personal connections and networks to recruit diverse students. As one participant described, “Recruiting diverse students begins with personal networks. So, we use personal networks, professional networks, alumni network.” In addition to recruiting through alumni and professional organizations and conferences, participants found success through partnerships with community agencies as well as building relationships with HBCUs and HSIs. One participant captured the process this way: “It’s about maintaining relationships with graduates, with colleagues. We know, for us to diversify our student body, we cannot just look to the surrounding states to produce a diverse student body. We have to go beyond that.”

In addition to reaching out to master’s programs with sizable diverse student populations, one common strategic effort involved finding financial support for diverse doctoral students, from departmental, institutional, or external funding sources. One participant stated, “We also know in our program where the sources for funding underrepresented populations are; we know how to hook people into those sources of funding.” Another participant shared, “Our institutions have funding mechanisms, including some that are for historically marginalized populations or underrepresented populations. We have been successful in applying for those and getting those.”

Participants indicated a commitment to making changes to their typical mode of recruitment strategy and recognized that supporting diverse students required the implementation of strategies that differed from typical recruiting and retaining activities. Three subcategories that emerged as representing effective recruitment and support strategies were (a) connection to cultural identity, (b) providing personalized support, and (c) involvement of faculty.

Connection to Cultural Identity. Consistent with the literature, participants reported that students seemed drawn to programs that valued their cultural background and research interests associated with their identity. For example, participants reported that it was important to have faculty who are interested in promoting social justice and diversity and sharing similar research interests to their students. As one participant described: “The student picked us because we supported their research interest of racial battle fatigue.” This participant had shared with their prospective student that “I’m really excited about that [topic], and it overlaps with my own research in historical trauma with native populations.”

Personalized Support. Participants indicated personalized support was crucial to recruiting diverse students to their CES doctoral program. One participant reported that most of the diverse students who chose to attend their doctoral program typically shared the same response when asked about their choice: “Their comments are consistent. . . . They say, ‘We came and interviewed, and we met you, and we met the students, and we feel cared about.’”

Faculty Involvement. Third, faculty involvement was an essential component of proactive and intentional efforts. Faculty involvement seemed to take a variety of forms: (a) activities related to promoting multiculturalism and social justice, (b) engagement in diverse areas of the profession and representing the program well, and (c) advocating to connect potential students to external funding resources or professional opportunities. One participant explained faculty involvement this way: “An anchor person who strongly identifies not only with their own diversity, but also with a body of scholarship related to diversity.” Another participant shared, “Our faculty have had some nice engagements with organizations and research strands focused on multiculturalism and social justice issues.” These types of involvement made an impact on the impressions of prospective students from diverse backgrounds: “We have students who came to us and said, ‘I looked at the work your faculty were doing, I looked at what they said was important on the website, and it struck a chord with me.’”

Support and Retention Strategies

The third major category of support and retention strategies was characterized as responding to awareness and understanding of diverse students’ perspectives, experiences, and needs while enrolled in the doctoral program. Participants reported that faculty engaged in proactive and intentional efforts that integrated considerations for cultural identity, personalized support, and faculty involvement.

Awareness and Understanding

As with recruitment, participants reported that successful retention and support of enrolled doctoral students integrated considerations for the students’ cultural identity as well as values, needs, and interests that are a part of that identity. One participant described exploring missing aspects of each student’s experience for the purpose of providing effective support: “It’s super important on a very regular basis to sit down with students of color specifically and talk with them about what they’re not getting . . . those conversations really are key.” Often, these personalized conversations are part of a healthy, intentional mentoring relationship in which students are purposely paired with faculty who can understand their experience, support them in navigating professional organizations, and foster success in the program and in their future career. Two participants added that an effective support strategy involves reaching out and engaging in regular conversations about student struggles and experience with microaggressions, tokenism, or other socioemotional matters.

Some participants reported that diverse students may be lacking in foundational skills and knowledge that put them at a disadvantage in the doctoral program, such as deficits in research competence. Personal conversations between mentors and protégés include being “willing to have difficult conversations about skill deficits” in a manner that encourages and empowers diverse students to succeed.

Proactive and Intentional Efforts

Successful education of diverse doctoral students is a mission that requires thoughtful, intentional, and proactive efforts on the part of doctoral faculty. A participant whose program had a good track record in recruiting diverse students explained, “Proactive efforts take a lot of thought” and aiming for effective retention necessitates “an intentional effort, and that’s what it takes to provide comfort for a more diverse group of students.” For many participants in the study, showing intentionality started with provision of financial support in the form of scholarships, fellowships, and graduate assistantships. Doctoral faculty also advocated for students by connecting them to funding sources because financial support “is the best predictor of keeping people in the program.”

Connection to Cultural Identity. Proactive and intentional efforts were considered to be a step beyond planning, in that doctoral faculty commit tangible and intangible resources along with taking actions toward promoting diversity in the program. In addition to inquiring about the missing aspects of their identity in the program, participants reported that ongoing conversations about cultural identity during the students’ program of study was important to support and retention. For example, some students chose a doctoral program to pursue a specific line of research connected with cultural identity and wanted their faculty members to make intentional efforts to help them further their line of inquiry related to cultural issues.

Personalized Support. Participants reported that personalized support was a critical strategy in helping culturally diverse doctoral students to thrive in the program. Participants believed that supportive faculty–student relationships had a strong impact on retention. As articulated by one participant, “One of our strengths is the relationship that we have with our students . . . it may be making the difference in the students that we keep.” Participants also used a buddy system whereby each student applicant was paired with a current doctoral student as their go-to person for any questions or concerns, to help them transition into the program.

Faculty Involvement. Embracing diversity is a proactive and intentional business, which translated to participants purposefully and thoughtfully changing the way they interact with prospective and current students from diverse backgrounds. Participants reported that diverse students may need more availability and outreach from faculty. As one participant stated, “We try to be available to them when they’ve got concerns that they need to address. We’re always trying to reach out more and being more proactive.” This proactive responsiveness and intentional mentoring seemed particularly important with regard to helping diverse students with professional identity development. One participant reflected that “some students coming from diverse backgrounds are going to need to be socialized into the profession, to make them comfortable in that identity.” Elaborating further, this participant said that, “this requires a lot of very intentional mentoring” and included formal as well as informal activities. For example, they said, “Even having them come to conferences, to introduce them to people. Having meals with them. Modeling how you interact with colleagues. Making sure they go to luncheons . . . to dinners.”

Discussion

In this study, 15 counselor educator participants gave voice to strategies that doctoral programs use to recruit, retain, and support underrepresented doctoral students from diverse backgrounds and their perceptions of the level of success these programs have had with their implemented strategies. We examined these experiences and identified two overarching themes of awareness and understanding and proactive and intentional efforts in the way they approached the need to recruit and support diverse doctoral students.

During the process of data analysis, a substantive framework emerged to explain participant strategies that had led to success. Analysis of the participants’ narratives shed light on counselor educators’ awareness and understanding that being proactive and intentional in integrating approaches that connect to the student’s cultural identity, provide personalized support, and involve faculty appear to be successful strategies for recruiting, retaining, and supporting diverse students. These categories reflect a program’s commitment to and demonstration of diversity, with the necessity of intentional and active approaches indicated in literature (Evans & Cokley, 2008; Hipolito-Delgado et al., 2017; McCallum, 2016; Rogers & Molina, 2006). Commitment to diversity has been found to be a highly influential factor in applicants’ decisions to enter a doctoral program (Haizlip, 2012; Zeligman et al., 2015) and once enrolled, for students from URM backgrounds to feel a sense of inclusion, connection, and belonging (Henfield et al., 2013; Hollingsworth & Fassinger, 2002; Protivnak & Foss, 2009).

The literature has indicated that a program’s commitment and intentionality about increasing the diversity of both students and faculty has a direct impact on the number of applicants received by that program (Zeligman et al., 2015). Participant narratives from this study supported this strategy. Diverse students are drawn to programs that value their cultural background and the research interests that come with that identity. This might mean presence of diverse faculty and student body, being encouraged to express their uniqueness, and having faculty who share their research interests. The unique needs, values, and interests of diverse students require CES faculty to be mindful of providing personalized support during the recruitment process as well as during their enrollment in the program. These can be in the form of intentional mentoring, support in addressing possible skills deficits, having personalized conversations, and engaging in a buddy system. A third essential strategy is faculty involvement in multiculturalism and social justice issues, engagement in diverse areas of the profession, and advocating for students academically, professionally, and socioeconomically.

Implications for Counselor Education

The findings from this study reveal the need for a change on the part of some CES doctoral programs in developing intentional and proactive efforts to recruit, support, and retain students from culturally diverse backgrounds. In this study, several participants noted that their doctoral program employed passive recruiting and retention strategies, which appeared to be inadequate and contrary to CACREP standards. Some participants also highlighted barriers to both recruiting and retaining diverse doctoral students, such as unclear standards and faculty attitudes and behaviors that include complacency, defensiveness and dismissiveness, lack of awareness, and assumptive thinking about diversity. Other CES departments seem to be partially implementing a comprehensive and systematic plan for recruiting and retaining diverse students. For example, they may utilize alumni networks to help with recruiting diverse students but lack a plan to support and retain enrolled students.

An important potential barrier for supporting diverse students in CES doctoral programs is the time required for faculty mentorship. Some participants in the study reported that some diverse students needed more close mentoring, and this time commitment would likely reduce available time for other faculty activities such as conducting research and writing for publication. For faculty on the tenure-track system in research institutions, losing time to research endeavors poses a potential threat to career advancement. One participant shared that while “by and large, most faculty want to mentor diverse students and put the time in,” this time commitment stood in opposition to their own tenure and promotion process. This participant elaborated that the pressure to “publish or perish” can “somewhat alter career trajectory for the faculty, if they spend too much time in mentoring.” This participant believed that this issue was “one of the real tensions here in academia” and explained that “either you want diversity, and you’re willing to reward people who are willing to invest themselves in the diversity . . . or you’re not. But you can’t have it both ways.” It appears that the current structure within universities, such as the criteria for tenure and promotion, can present a significant barrier to supporting diverse students. Prior authors have noted that established university and program culture can create a sense of marginalization for diverse students, making it difficult to both recruit and retain URM doctoral students (Holcomb-McCoy & Bradley, 2003; Zeligman et al., 2015). Faculty may need to advocate for structural changes within their universities to ensure that their students are adequately supported. Some participants in the study indicated that low teaching loads were another avenue of freeing up time for mentoring.

The CACREP standards (2015) contain a mandate for systematic and continuous efforts to retain a diversified student body in counselor education programs. Some participants noted in this study that the actual appraisal by CACREP site visit teams of how this standard was being met was unclear. Confusion about this standard may result in not having a strategy for ensuring that the standard was being met. Clarification and accountability are necessary to ensure that programs are meeting this standard.

It is crucial that counselor education programs continue to develop specific strategies to both recruit and retain underrepresented doctoral students. It is no longer acceptable to rest on the institutional name or location. Intentionality that addresses the needs of underrepresented students should include connection to students’ cultural identity, personalized support, and faculty involvement, as these will ensure that students feel wanted and valued throughout the entire process (recruitment to completion).

Limitations

Although grounded theory provides a richness and depth to understanding questions for research, it comes with potential limitations. Clarke (2005) discussed limitations typical in qualitative research and grounded theory. Researchers are faced with an overwhelming amount of information to code, categorize, and analyze. Qualitative researchers can quite easily get bogged down with the complexity and amount of data, which can lead to a diluting of results (Clarke, 2005). The research team addressed this challenge by engaging in a two-step coding process: engaging in group coding of the first three transcripts and then dyadic coding of the remaining transcripts. Through saturation, the research team was able to establish categories that captured the main themes and ideas of the participant statements and check their own biases and values as potentially impacting the interpretation of the codes.

The research team was composed of members who themselves are from diverse backgrounds and who had experiences as doctoral students in CES programs. In addition, all members of the research team currently work in counselor training programs and wrestle with the same questions under review—namely, how to recruit, support, and retain diverse students. The research team attempted to address limitations through developing a priori codes potentially rooted in their own experiences and through recording memos during each group and individual coding session to capture the presence of personal values, biases, or experiences, as well as checking other team members’ codes. Although it is impossible to fully account for all potential biases present in a qualitative analysis, these efforts of diligently checking experiences aimed to mitigate this impact on the overall results and conclusions of the study.

Although the coding team believed that data reached saturation at 15 interviews, the sample was small (N = 15) for the method of inquiry according to Creswell and Poth (2018). Although we believe that limiting the number of respondents to no more than one faculty member per program was helpful in reducing the potential for bias due to group effect, it is possible that the faculty members surveyed were not the sole representations of their counselor education program. As with many qualitative studies, generalizability to the larger population is limited. However, it is noteworthy that the demographics of the participants in the current study do align with typical cultural representation of counselor education programs (CACREP, 2018).

Future quantitative studies are needed to evaluate the size of the effect of these strategies on recruitment and retention rates of diverse students in CES doctoral programs. For example, future studies could evaluate the relationship between student perceptions of proactive and intentional efforts toward connecting with cultural identity, personalized support, and faculty involvement with actual retention rates of diverse students in CES programs and their overall student satisfaction. Such information would be helpful to decipher which of these factors has the greatest impact on recruiting, retaining, and supporting diverse students in CES doctoral programs, which would be useful information for current CES doctoral programs.

Conclusion

This study highlights that although more efforts to recruit and retain students from diverse backgrounds are needed, when counselor education programs are intentional and proactive, it has a meaningful impact. What seems to be effective in recruiting, retaining, and supporting diverse students is developing a connection to cultural identity, support that is personalized, and faculty involvement. When students from diverse backgrounds feel some connection to their specific cultural identity and receive personalized support, they are more likely to enter a program and persist. Finally, the involvement of faculty at all levels of the recruitment and retention process is monumental. Students from diverse backgrounds perceive counselor education programs as inviting and able to meet their cultural needs when programming is intentional and proactive.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Baker, C. A., & Moore, J. L., III. (2015). Experiences of underrepresented doctoral students in counselor education. Journal for Multicultural Education, 9(2), 68–84. https://doi.org/10.1108/JME-11-2014-0036

Barker, M. J. (2016). The doctorate in black and white: Exploring the engagement of Black doctoral students in cross race advising relationships with White faculty. Western Journal of Black Studies, 40(2), 126–140.

Behl, M., Laux, J. M., Roseman, C. P., Tiamiyu, M., & Spann, S. (2017). Needs and acculturative stress of international students in CACREP programs. Counselor Education and Supervision, 56(4), 305–318.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12087

Blackwell, J. E. (1987). Mainstreaming outsiders: The production of Black professionals (2nd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield.

Blockett, R. A., Felder, P. P., Parrish, W., III, & Collier, J. N. (2016). Pathways to the professoriate: Exploring Black doctoral student socialization and the pipeline to the academic profession. The Western Journal of Black Studies, 40(2), 95–110.

Brown, E. M., & Grothaus, T. (2019). Experiences of cross-racial trust in mentoring relationships between Black doctoral counseling students and White counselor educators and supervisors. The Professional Counselor, 9(3), 211–225. https://doi.org/10.15241/emb.9.3.211

The Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education. (2019). Basic classification description. http://carn

egieclassifications.iu.edu/classification_descriptions/basic.php

Castellanos, J., Gloria, A. M., & Kamimura, M. (Eds.). (2006). The Latina/o pathways to the Ph.D.: Abriendo caminos. Stylus.

Chan, A. W., Yeh, C. J., & Krumboltz, J. D. (2015). Mentoring ethnic minority counseling and clinical psychology students: A multicultural, ecological, and relational model. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(4), 592–607. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000079

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). SAGE.

Chen, S. Y., Basma, D., Ju, J., & Ng, K.-M. (2020). Opportunities and challenges of multicultural and international online education. The Professional Counselor, 10(1), 120–132. https://doi.org/10.15241/syc.10.1.120

Clarke, A. E. (2005). Situational analysis: Grounded theory after the postmodern turn. SAGE.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed.). SAGE.

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2014). CACREP vital statistics 2013: Results from a national survey of accredited programs. http://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/20

19/05/2013-CACREP-Vital-Statistics-Report.pdf

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2015). CACREP standards 2016. https://www.cacrep.org/for-programs/2016-cacrep-standards

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2016). CACREP vital statistics 2015: Results from a national survey of accredited programs. http://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/20

19/05/2015-CACREP-Vital-Statistics-Report.pdf

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2018). CACREP vital statistics 2017: Results from a national survey of accredited programs. http://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/20

19/05/2017-CACREP-Vital-Statistics-Report.pdf

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2019). Annual report 2018. https://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/CACREP-2018-Annual-Report.pdf

Creswell, J. W., Hanson, W. E., Plano, V. L. C., & Morales, A. (2007). Qualitative research designs: Selection and implementation. The Counseling Psychologist, 35(2), 236–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000006287390

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). SAGE.

Definitions, 20 U.S.C. 20 § 1067k (2020). November 2, 2019. https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid

:USC-prelim-title20-section1067k&num=0&edition=prelim

Dieker, L., Wienke, W., Straub, C., & Finnegan, L. (2013). Reflections on recruiting, supporting, retaining, graduating, and obtaining employment for doctoral students from diverse backgrounds. Teacher Education and Special Education, 37(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406413505874

Evans, G. L., & Cokley, K. O. (2008). African American women and the academy: Using career mentoring to increase research productivity. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 2(1), 50–57.

https://doi.org/10.1037/1931-3918.2.1.50

Foxx, S. P., Kennedy, S. D., Dameron, M. L., & Bryant, A. (2018). A phenomenological exploration of diversity in counselor education. Journal of Professional Counseling: Practice, Theory & Research, 45(1), 17–32.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15566382.2019.1569320

González, J. C. (2006). Academic socialization experiences of Latina doctoral students: A qualitative understanding of support systems that aid and challenges that hinder the process. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 5(4), 347–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538192706291141

Goodman, R. D., Williams, J. M., Chung, R. C.-Y., Talleyrand, R. M., Douglass, A. M., McMahon, H. G., & Bemak, F. (2015). Decolonizing traditional pedagogies and practices in counseling and psychology education: A move towards social justice and action. In R. D. Goodman & P. C. Gorski (Eds.), Decolonizing “multicultural” counseling through social justice (pp. 147–164). Springer.

Grapin, S. L., Bocanegra, J. O., Green, T. D., Lee, E. T., & Jaafar, D. (2016). Increasing diversity in school psychology: Uniting the efforts of institutions, faculty, students, and practitioners. Contemporary School Psychology, 20(4), 345–355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-016-0092-z

Guillory, R. M. (2009). American Indian/Alaska Native college student retention strategies. Journal of Developmental Education, 33(2), 14–16, 18, 20, 22–23, 40. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ897631.pdf

Haizlip, B. N. (2012). Addressing the underrepresentation of African-Americans in counseling and psychology programs. College Student Journal, 46(1), 214–222.

Henfield, M. S., Owens, D., & Witherspoon, S. (2011). African American students in counselor education programs: Perceptions of their experiences. Counselor Education and Supervision, 50(4), 226–242.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2011.tb00121.x

Henfield, M. S., Woo, H., & Washington, A. (2013). A phenomenological investigation of African American counselor education students’ challenging experiences. Counselor Education and Supervision, 52(2), 122–136. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2013.00033.x

Hinojosa, T. J., & Carney, J. V. (2016). Mexican American women pursuing counselor education doctorates: A narrative inquiry. Counselor Education and Supervision, 55(3), 198–215. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12045

Hipolito-Delgado, C. P., Estrada, D., & Garcia, M. (2017). Counselor education in technicolor: Recruiting graduate students of color. Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 51(1), 73–85.

https://doi.org/10.30849/RIP/IJP.V51I1.293

Holcomb-McCoy, C., & Bradley, C. (2003). Recruitment and retention of ethnic minority counselor educators: An exploratory study of CACREP-accredited counseling programs. Counselor Education and Supervision, 42(3), 231–243. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2003.tb01814.x

Hollingsworth, M. A., & Fassinger, R. E. (2002). The role of faculty mentors in the research training of counseling psychology doctoral students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 49(3), 324–330.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.49.3.324

Interiano, C. G., & Lim, J. H. (2018). A “chameleonic” identity: Foreign-born doctoral students in U.S. counselor education. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 40, 310–325.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-018-9328-0

Lerma, E., Zamarripa, M. X., Oliver, M., & Vela, J. C. (2015). Making our way through: Voices of Hispanic counselor educators. Counselor Education and Supervision, 54(3), 162–175. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12011

Lewis, C. W., Ginsberg, R., Davies, T., & Smith, K. (2004). The experiences of African American Ph.D. students at a predominately White Carnegie I-research institution. College Student Journal, 38(2), 231–245.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (2013). The constructivist credo. Left Coast Press, Inc.

Luedke, C. L., Collom, G. D., McCoy, D. L., Lee-Johnson, J., & Winkle-Wagner, R. (2019). Connecting identity with research: Socializing students of color towards seeing themselves as scholars. The Review of Higher Education, 42(4), 1527–1547. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2019.0074

Marsella, A. J., & Pedersen, P. (2004). Internationalizing the counseling psychology curriculum: Toward new values, competencies, and directions. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 17(4), 413–423.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070412331331246

McCallum, C. M. (2015). Turning graduate school aspirations into enrollment: How student affairs professionals can help African American students. New York Journal of Student Affairs, 15(1), 1–18. https://journals.canisius.edu/index.php/CSPANY/article/view/448/717

McCallum, C. M. (2016). “Mom made me do it”: The role of family in African Americans’ decisions to enroll in doctoral education. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 9(1), 50–63. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039158

Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed.). Wiley.

Ng, K.-M. (2006). Counselor educators’ perceptions of and experiences with international students. International Journal for the Advancement of Counseling, 28(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-005-8492-1

Ng, K.-M., & Smith, S. D. (2009). Perceptions and experiences of international trainees in counseling and related programs. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 31, 57–70.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-008-9068-7

Patton, M. Q. (2014). Qualitative research and evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice (4th ed.). SAGE.

Ponjuan, L. (2011). Recruiting and retaining Latino faculty members: The missing piece to Latino student success. Thought & Action, 99–110. https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/bitstream/handle/10919/84034/Recruit

ingLatinoFacultyMembers.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Ponterotto, J. G. (2005). Qualitative research in counseling psychology: A primer on research paradigms and philosophy of science. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.126

Preston, J., Trepal, T., Morgan, A., Jacques, J., Smith, J., & Field, T. (2020). Components of a high-quality doctoral program in counselor education and supervision. The Professional Counselor, 10(4), 453–471. https://doi.org/10.15241/jp.10.4.453

Proctor, S. L., & Romano, M. (2016). School psychology recruitment research characteristics and

implications for increasing racial and ethnic diversity. School Psychology Quarterly, 31(3), 311–326. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000154

Protivnak, J. J., & Foss, L. L. (2009). An exploration of themes that influence the counselor education doctoral student experience. Counselor Education and Supervision, 48(4), 239–256.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2009.tb00078.x

Rogers, M. R., & Molina, L. E. (2006). Exemplary efforts in psychology to recruit and retain graduate students of color. American Psychologist, 61(2), 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.61.2.143

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). SAGE.

Woo, H., Jang, Y. J., & Henfield, M. (2015). International doctoral students in counselor education: Coping strategies in supervision training. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 43(4), 288–304. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmcd.12022

Zeligman, M., Prescod, D. J., & Greene, J. H. (2015). Journey toward becoming a counselor education doctoral student: Perspectives of women of color. The Journal of Negro Education, 84(1), 66–79.

https://doi.org/10.7709/jnegroeducation.84.1.0066

The authors present this article in memory of Dr. Rose Merrell-James, who shared her knowledge, experience, strength, and wisdom with all of us through this scholarly work.

Jennie Ju, PhD, LPC, is an assistant professor at Palo Alto University. Rose Merrell-James was an assistant professor at Shippensburg University. J. Kelly Coker, PhD, MBA, NCC, BC-TMH, LCMHC, is a professor and program director at Palo Alto University. Michelle Ghoston, PhD, ACS, LPC(VA), LCMHC, is an assistant professor at Wake Forest University. Javier F. Casado Pérez, PhD, NCC, LPC, CCTP, is an assistant professor at Portland State University. Thomas A. Field, PhD, NCC, CCMHC, ACS, LPC, LMHC, is an assistant professor at the Boston University School of Medicine. Correspondence may be addressed to Jennie Ju, 1791 Arastradero Road, Palo Alto, CA 94304, jju@paloaltou.edu.

Appendix A

Interview Protocol

For context, please briefly describe how you self-identify and your background. This information will be aggregated; individual participant responses will not be associated with any quotes in subsequent manuscripts.

Gender:

Sexual/Affective Orientation:

Race and Ethnicity:

Years as a Faculty Member in a Counselor Education Program:

Years as a Faculty Member in a Doctoral Counselor Education Program:

Number of Doctoral Counselor Education Programs You Have Worked In:

Regions of Doctoral Counselor Education Programs You’ve Worked In (using regions

commonly defined by national counselor education associations and organizations):

How might you define a “high-quality” doctoral program?

What do you believe to be the most important components? The least important?

How have you helped students to successfully navigate the dissertation process?

Which strategies has your program used to recruit underrepresented students from diverse

backgrounds? How successful were those?

Which strategies has your program used to support and retain underrepresented students from diverse

backgrounds? How successful were those?

What guidance might you provide to faculty who want to start a new doctoral program in counseling

with regards to working with administrators and gaining buy-in?

What guidance might you provide to faculty who want to sustain an existing doctoral program in

counseling with regards to working with administrators and gaining ongoing support?

Last question. What other pieces of information would you like to share about running a successful,

high-quality doctoral program?

Aug 18, 2020 | Volume 10 - Issue 3

Jessica Burkholder, David Burkholder, Stephanie Hall, Victoria Porter