Mar 18, 2025 | Volume 15 - Issue 1

Zori A. Paul, Kyesha M. Isadore, Nishi Ravi, Kayla D. Lewis, Dewi Qisti, Alex Hietpas, Bergen Hermanson, Yuji Su

Queer and transgender people of color (QTPOC) face unique mental health challenges because of intersecting forms of discrimination that place them at higher risk for adverse mental health outcomes. Emerging research has begun to explore the concept of microaffirmations—small verbal or nonverbal forms of communication that signal support, encouragement, or validation—as a protective factor for marginalized populations. This study highlights how QTPOC experience and perceive microaffirmations and explores the role microaffirmations play in their mental health and well-being. Utilizing an interpretive phenomenological analysis, qualitative data were obtained from 14 QTPOC participants through semi-structured interviews. Analyses identified five superordinate themes: influence of identity development, safety with others, envisioning policy changes, representation, and internalization of perceived worth. This study demonstrates the role microaffirmations play in mitigating the negative impacts of discrimination and enhancing the well-being of QTPOC. Implications for counselors include suggestions for providing QTPOC clients with more affirming care on the micro and macro levels.

Keywords: microaffirmations, queer, transgender, people of color, mental health

The number of queer and transgender people of color (QTPOC) in the United States is increasing (Jones, 2024), leading to a greater focus on their unique experiences and mental health needs. In recent years, the visibility of QTPOC has grown, and with it, awareness of the specific challenges they face. These challenges are compounded by intersecting forms of discrimination related to both their racial/ethnic identities and their sexual and gender identities (Cyrus, 2017). Despite this increased visibility, QTPOC continue to experience significant mental health disparities, which are often overlooked in broader discussions about mental health and well-being. These mental health concerns include higher rates of depression, anxiety, and trauma, as well as increased risk of suicidal ideation compared to their White cisgender or heterosexual counterparts (Bostwick et al., 2014; Horne et al., 2022; Meyer, 2003; White Hughto et al., 2015).

Based on the existing mental health disparities among QTPOC, the need exists for enhanced awareness and education about how to promote safe and affirming therapeutic environments for QTPOC clients. Recent research indicates that QTPOC’s mental health outcomes, sense of belonging, and overall well-being are dependent on interactions with others both on the micro and macro levels. For example, how QTPOC are referred to by counselors or administrative staff and how welcomed they feel as members of their community significantly impact their overall mental health and well-being (Pflum et al., 2015). At the same time, QTPOC often experience stressors related to state and federal anti-LGBTQIA+ legislation and lack of competency from non-QTPOC counselors and other health care professionals, possibly leading to feelings of exclusion (Dispenza & O’Hara, 2016; Horne et al., 2022). Counselors and researchers have emphasized the need for addressing issues of racism, homophobia, and transphobia in clinical practices, counselor education programs, and broader societal contexts (Dispenza & O’Hara, 2016; Miller et al., 2018; Mizock & Lundquist, 2016).

Mental Health Concerns for Queer and Transgender People of Color

In recent decades, there has been an increase in research examining the social experiences of minoritized groups, including queer adults, transgender individuals, and people of color (Brooks, 1981; Flanders et al., 2019; Meyer, 2003; Testa et al., 2015). These studies have highlighted substantial disparities in mental health and well-being among these populations, often linked to experiences of discrimination and marginalization. Research indicates that QTPOC are particularly vulnerable to mental health issues because of the intersecting impacts of racism, heterosexism, and transphobia. For instance, a study examining factors related to depression and anxiety for lesbian, gay, and bisexual people of color found that both distal and proximal minority stressors accounted for 33% of the variance in participants’ mental health outcomes (Ramirez & Galupo, 2019). This dual marginalization often leads to cumulative forms of discrimination, including social exclusion from both larger society and within their own communities. QTPOC may face racism within the LGBTQIA+ community and heterosexism or transphobia within their racial and ethnic groups (Cyrus, 2017). Despite these challenges, social support and community connectedness have been identified as critical resources that can buffer the effects of stigma and promote resilience among QTPOC. For example, social support from individuals who are empathetic toward discriminatory experiences can shield young African American LGBTQIA+ youth from the distress associated with intersectional discrimination, fostering a sense of affirmation for their identities and enhancing their autonomy in help-seeking behaviors (Hailey et al., 2020).

Community connectedness has also been linked to positive outcomes among QTPOC (Roberts & Christens, 2020). Roberts and Christens (2020) found that being open about one’s sexual or gender identity (i.e., outness) is beneficial to the well-being of White participants, but not directly for Black and Latinx participants. Instead, the positive effects of outness on well-being for these groups are mediated by their connectedness to the LGBTQIA+ community (Roberts & Christens, 2020). However, the effectiveness of community connectedness can vary. For example, McConnell and colleagues (2018) reported that community connectedness had a weaker mediating effect on the relationship between stigma and stress in sexually minoritized men of color compared to their White counterparts, suggesting that racial stigma may diminish the protective effects of community connectedness. Establishing community connectedness with other QTPOC may foster positive within-community relationships that extend beyond discrete identity groups, enabling members to feel acknowledged and accepted, and leading to positive reappraisals about their identities (Ghabrial & Andersen, 2021; G. Smith et al., 2022). Despite the potential utility gained by understanding factors that promote coping and resilience, there is still a lack of research examining their impact on the mental health and well-being of QTPOC. Emerging research has begun to explore potential sources of everyday coping and resilience, such as the study of microaffirmations.

Microaffirmations

Microaffirmations are defined as small verbal or nonverbal communications that signal support, encouragement, or validation (Ellis et al., 2019; Rowe, 2008). Despite their subtle nature, microaffirmations can be intentional or unintentional, with some occurring as deliberate acts of affirmation while others emerge naturally in everyday interactions (Rowe, 2008). Rowe (2008), who first introduced the concept, posited that for underrepresented groups, daily occurrences of marginalization may go overlooked or be diminished within hierarchical power structures. As members of these groups often struggle with feeling appreciated and accepted within disempowering environments, microaffirmations may effectively counter these negative experiences by disrupting processes that promote social exclusion and oppression (Ellis et al., 2019). Microaffirmations normalize and acknowledge the contributions of marginalized individuals, offer individuals support during times of distress, and empower disenfranchised group members to leverage their strengths to maximize their potential (Rowe, 2008). In general, microaffirmations function as a tool of social reinforcement to bolster productivity by engendering a sense of belonging, fostering inclusion, and enhancing well-being (Topor et al., 2018).

Over the past decade, microaffirmations have emerged as a potential protective factor against the detrimental impact of prejudice and discrimination (Pérez Huber et al., 2021; Rolón-Dow & Davison, 2021). In particular, the underlying behavioral mechanisms of microaffirmations are implicated in reducing intergroup conflict stemming from social stratification and stigma (Jones & Rolón-Dow, 2018; Rolón-Dow & Davison, 2021). Although microaffirmations were initially developed within the workplace literature to address the experiences of cisgender women, recent work has extended the concept’s application to further marginalized groups, including people of color and the LGBTQIA+ community. Microaffirmations can play an important role in the lives of LGBTQIA+ individuals by communicating acceptance, extending social support, and affirming their identity (Flanders et al., 2019). For example, in a cross-sectional study with LGBTQIA+ adolescents, Sterzing and Gartner (2020) found that receiving microaffirmations from family members was associated with a reduction in symptoms of depression, distress, emotional dysregulation, and suicidality. Similarly, interpersonal microaffirmations have also been associated with fewer symptoms of anxiety and stress (Flanders, 2015) and are frequently referred to as impactful experiences of affirmation among bisexual people (Flanders et al., 2019). However, some studies suggest that the effects of microaffirmations may be limited or context-dependent. For example, DeLucia and Smith (2021) found that microaffirmations from mental health providers had no impact on bisexual people’s intentions to seek mental health treatment, whereas experiences of biphobia negatively influenced these intentions. Similarly, Salim et al. (2019) found no association between microaffirmations and happiness among bisexual women. These findings suggest that the effects of microaffirmations may be context-dependent, influencing some aspects of well-being while having little impact on others. Although microaffirmations may foster a sense of validation and support, they may not necessarily translate into behavioral changes, such as help-seeking. These varying results highlight the need for further research on microaffirmations to understand their impact on well-being within different social contexts and systems of power and privilege.

In contrast, research with transgender adults has shown relatively consistent and positive outcomes associated with microaffirmations. Using thematic analysis, Anzani and colleagues (2019) found that microaffirmations may strengthen the therapeutic alliance and enhance perceived treatment satisfaction and efficacy for transgender clients. Scholars have also investigated racial-specific microaffirmations, conceptualized as acts, cues, or verbal utterances that validate racial identities, acknowledge lived experiences, and promote racial justice norms (Rolón-Dow & Davison, 2021). While microaffirmations may have a lesser psychological impact, incidence rate, and intensity than microaggressions (Jones & Rolón-Dow, 2018), they may function to counteract and partially repair the cumulative effects of insidious everyday acts of racism (Pérez Huber et al., 2021). Racial microaffirmations can promote healing through shared cultural intimacy, enabling supportive community members to engage in a cumulative and responsive process of acknowledgment and support that can be both protective and restorative in the context of structural racism (Pérez Huber et al., 2021).

The Current Study

The theoretical framework for this study is grounded in Minority Stress Theory (MST; Brooks, 1981; Meyer, 2003) and Rolón-Dow and Davison’s (2021) typology of microaffirmations. MST posits that the stress experienced by individuals with stigmatized identities is not due to the identity itself but arises from external prejudice and discrimination, as well as internalized stigma (Brooks, 1981; Meyer, 2003). For QTPOC, these stressors are compounded by intersecting forms of racism, heterosexism, and transphobia. This framework highlights the unique stressors faced by QTPOC and underscores the need to understand the multifaceted nature of their experiences. In addition to MST, this study draws on the typology of racial microaffirmations from a critical race/LatCrit approach developed by Rolón-Dow and Davison (2021), which includes four forms: microrecognitions, microprotections, microtransformations, and microvalidations. Each type can be understood as different feelings arising from behaviors, verbal statements, or environmental cues. Microrecognitions involve feeling acknowledged and included (e.g., Pride flags, signage), microprotections offer a sense of being shielded from disparagement (e.g., support and advocacy from others), microtransformations foster a deep sense of belonging and capability (e.g., individuals or institutions advocating for federal and state policies that protect LGBTQ+ rights), and microvalidations affirm that one’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are accepted and valued (e.g., QTPOC-specific spaces). While MST has provided a valuable framework for understanding QTPOC mental health disparities, there remains a need to explore how protective factors, such as microaffirmations, can mitigate the negative impact of discrimination on QTPOC. Microaffirmations, though subtle, normalize marginalized communities’ existence and place in society and may counterbalance the pervasive negative experiences of marginalization. Despite the promising research on microaffirmations for individual marginalized groups, research specifically focusing on the impact of microaffirmations on QTPOC is still limited. Given the significant mental health disparities faced by QTPOC and the potential of microaffirmations as a protective factor, this study aimed to deepen the understanding of these dynamics and identify effective strategies for fostering resilience and improving mental health outcomes among QTPOC. The purpose of this study was to 1) explore how QTPOC describe and understand microaffirmations and 2) investigate the specific types of microaffirmations in relation to the mental health and well-being of QTPOC.

Method

The current study employed an interpretive phenomenological design. Interpretive phenomenology is a rigorous qualitative methodology that seeks to uncover participants’ meaning-making processes—comprising their understandings, perceptions, and experiences—related to their lived experiences with a particular phenomenon (J. A. Smith et al., 2009). Interpretive phenomenological analysis (IPA) focuses analytically on the personal meaning-making of participants within specific contexts (J. A. Smith et al., 2009). Through this method, themes are systematically identified and leveraged to construct interpretive descriptions of participants’ narratives, providing insight into the meanings and essences of their lived experiences with the phenomenon.

Participants and Procedures

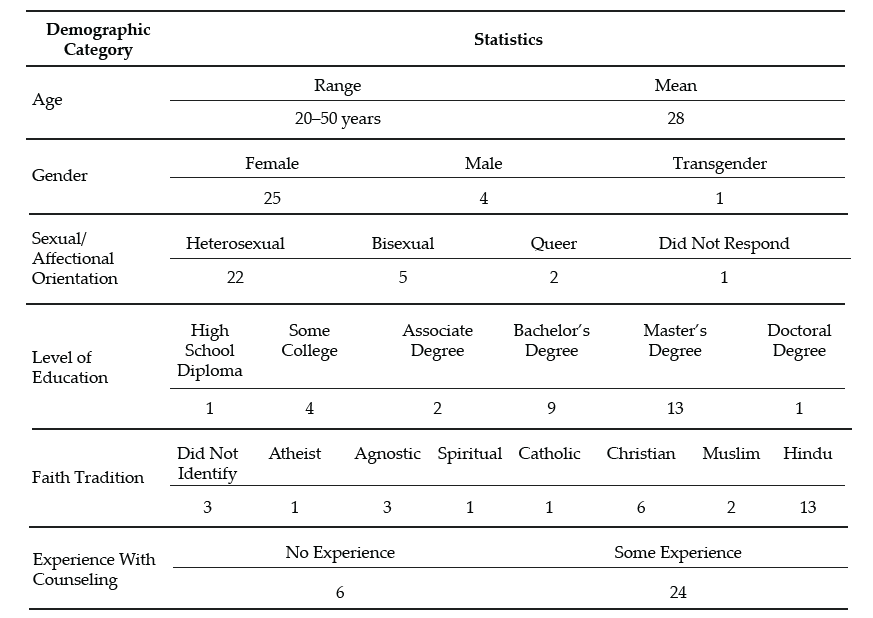

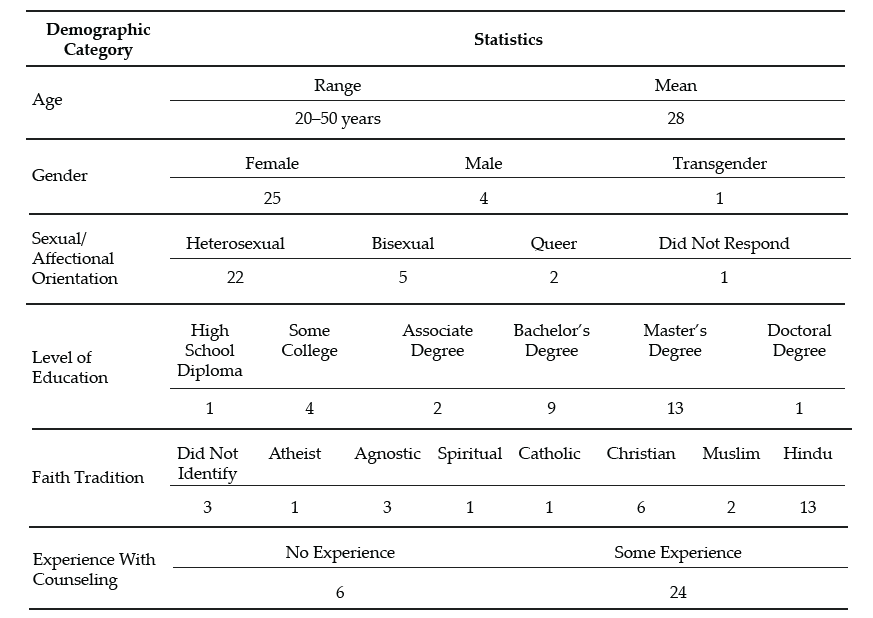

Institutional review board approval was secured prior to participant recruitment or data collection, and all participants gave consent via the online survey. Data was collected during the summer of 2023 and participants were recruited through recruitment flyers and emails via social media, LGBTQIA+ listservs, snowball sampling, and national listservs and interest networks. Eligible participants were asked to respond to an online survey to complete a brief demographic survey and were then contacted by the researchers to schedule a virtual interview. Eligibility criteria included: 18 years of age or older and capable of providing informed consent, identifying as a person of color with a marginalized sexual and/or gender identity, and currently living in the United States or U.S. territories. Interviews took place privately on a video-conferencing platform and were recorded and transcribed for data collection purposes. Participants who completed the interview were provided with a $25 e-gift card as an incentive for participation in the study. Participant demographics are presented in Table 1. All participants (N = 14) identified as a person of color; ages 22–46; sexual identities included queer, bisexual, asexual, demisexual, and gay/lesbian; gender identities included cisgender man, cisgender woman, and non-binary/gender-expansive. Racially and ethnically, participants identified as Filipino, Black/African American, Afro-Caribbean, Chinese American, Latino/a/x, Vietnamese, and Chinese. All participants held a postsecondary degree including bachelor’s, master’s, or doctorate degrees.

All participants engaged in one 60-minute semi-structured interview, which consisted of 19 open-ended questions and prompts aimed at exploring participants’ lived experiences with microaffirmations and the utility of microaffirmations in their daily lives. Drawing from Rolón-Dow & Davison’s (2021) typology of microaffirmations, the interview protocol (see Appendix) was designed to explore participants’ experiences with the four forms of microaffirmations: microrecognitions, microprotections, microtransformations, and microvalidations. For example, the question “Could you describe everyday experiences that made you feel that your thoughts, feelings, sensations, and/or behaviors associated with your lived experience as [insert identity] are accepted, legitimized, or given value?” was formulated to invite participants to reflect on whether they experienced microvalidations. This open-ended question was followed up with questions such as “If you haven’t experienced that, what do you think positive acknowledgment and understanding of your identity and lived experience would look like?” and “In what ways do you think more positive acknowledgment and understanding would impact you directly?” Audio files were recorded using a secure device and stored in a restricted access folder on the researcher’s university department server. Files were used for transcription purposes only and destroyed after the transcription process was complete.

Data Analysis

The data analysis process adhered to the established analytic procedures of IPA outlined by J. A. Smith and colleagues (2009). IPA is characterized by its interactive and inductive approach, focusing on how individuals make sense of their specific lived experiences. The interpretive nature of IPA allows for interpretations that may diverge from the participant’s original text, provided these interpretations are rooted in a close examination of the participant’s words (J. A. Smith et al., 2009).

Initially, the interviews were transcribed verbatim and meticulously reviewed by the research team to understand their context. During this preliminary phase, bracketing and initial coding were performed to describe the interview content. Each interview was individually analyzed to identify central concepts before finding commonalities across interviews (J. A. Smith et al., 2009). The researchers then utilized these initial codes and the original transcripts to identify emergent themes and patterns, employing techniques like abstraction and subsumption to develop superordinate themes. These steps were repeated for each of the participants individually to allow for new themes to emerge by case before superordinate themes were compared across participant cases corresponding to the central research questions.

Table 1

Participant Demographic Information

| Participant

(pronouns) |

Age |

Gender Identity |

Sexual Identity |

Race/Ethnicity |

Highest Degree |

| April

(she/her) |

29 |

Cisgender woman |

Asexual, Demisexual |

Chinese American |

Master’s degree |

| Baohua

(not disclosed) |

36 |

Cisgender man |

Gay |

Asian or Asian American |

Master’s degree |

| D

(she/her) |

28 |

Cisgender woman |

Lesbian, Demisexual |

Black or African American |

Master’s degree |

| Didi

(not disclosed) |

27 |

Cisgender woman |

Bisexual |

Latino/a/x or Hispanic |

Bachelor’s degree |

| Dwayne

(he/him) |

46 |

Cisgender man |

Gay |

Black or African American |

Master’s degree |

| Faith

(she/her) |

23 |

Cisgender woman |

Lesbian, Bisexual, Questioning |

Filipino |

Bachelor’s degree |

| J

(he/him) |

31 |

Cisgender man |

Bisexual |

Filipino |

Doctorate degree |

| Jane

(she/her) |

36 |

Cisgender woman |

Queer |

Black or African American |

Doctorate degree |

| Kay

(she/her) |

27 |

Cisgender woman |

Bisexual, Queer |

Black/Afro-Caribbean |

Master’s degree |

| Lucia

(they/them) |

26 |

Gender-expansive |

Queer |

Filipino |

Master’s degree |

| Nick

(he/him) |

27 |

Cisgender man |

Gay |

Black or African American |

Bachelor’s degree |

| Oliver

(he/him/any) |

22 |

Cisgender man |

Gay, Queer |

Vietnamese |

Bachelor’s degree |

| QL

(not disclosed) |

29 |

Gender-expansive |

Queer |

Chinese |

Master’s degree |

| Stacey

(she/her) |

29 |

Cisgender woman |

Bisexual |

African American & Caribbean American |

Doctorate degree |

Trustworthiness and Researcher Positionality

Our research team consisted of one Black bisexual/queer cisgender female faculty member, one Black queer genderfluid faculty member, four doctoral counseling students, and two master’s counseling students. The students on the research team identify as members of various races/ethnicities, genders, and sexual orientations. All members of the research team either work in or are enrolled in CACREP-accredited counselor education or APA-accredited counseling psychology programs, and all researchers have clinical experience working with diverse populations. To increase opportunities for candid conversations about the role of race/ethnicity, gender, sexuality, and intersectionality with participants throughout the interview process, interviews were conducted by members of the research team who identify as racially/ethnically minoritized, gender-expansive, and/or queer.

Several well-established methodological strategies were employed throughout data collection and analysis to enhance the credibility and trustworthiness of the findings. Multiple coders and peer audits of codes and themes were used to further explore themes, patterns, and interpretations; challenge assumptions; and provide additional insights. This approach is a recognized strategy for enhancing credibility in qualitative research (Yardley, 2008). The involvement of multiple coders and peer audits also served as a check against normative assumptions, prompting researchers to consider how systemic biases might influence their interpretations. Additionally, the research team conducted member checks with participants to verify the accuracy of themes and interpretations. Following the example of Lincoln and Guba (1985), the research team conducted member checks to allow participants to react to the data and the research team’s interpretations before their feedback was incorporated into the presentation of the findings. Participants who engaged in the member check process were provided with a $10 e-gift card as a token of appreciation. The participants’ feedback was not merely a validation step but also a critical engagement with their lived experiences, contributing to a more comprehensive representation of their narratives. The research team met weekly to engage in reflexive discussions about our assumptions, biases, personal worldviews, questions, and concerns related to our research processes, analyses, interpretations, and conclusions.

Results

An in-depth phenomenological analysis of the 14 participant interviews resulted in identification of five superordinate themes related to understanding the role of microaffirmations among QTPOC. Superordinate themes include influence of identity development, safety with others, envisioning policy changes, representation, and internalization of perceived worth.

Influence of Identity Development

The theme influence of identity development reflected how participants understood the utility of microaffirmations in relation to their racial, gender, and sexual identity development. Participants at earlier stages of identity development emphasized the importance of microvalidations and microrecognitions, which provided support and validation as they navigated internal conflict, such as questioning their identity or experiencing self-doubt. For example, April, a 29-year-old asexual/demisexual Chinese American woman, shared that she was still discovering her identity and sometimes felt “a little bit ambiguous about where I’m located on the map.” She highlighted how microvalidations—subtle signs of being recognized and valued—helped her feel seen and supported during this uncertain time:

The other person listening to me or asking me questions that make me feel seen . . . I would say people noticing the pieces that are authentic to who I am and people being willing to spend time listening to me and asking follow-up questions. That is affirming.

Similarly, Faith, a 23-year-old lesbian/bisexual Filipino woman, described herself as “either bisexual or gay, not sure which one yet,” and reflected on how microrecognitions, such as being acknowledged in conversations or within social settings, validated her evolving identity. These early-stage participants frequently described microvalidations and microrecognitions as pivotal in affirming their personal experiences and alleviating internal struggles with identity. In contrast, participants who were more secure and confident in their identities—representing a later stage in their identity development—emphasized a need for microprotections and microtransformations—types of microaffirmations that extend beyond individual validation to encompass broader social change. These participants valued microprotections, which offer safeguarding measures for the QTPOC community against discrimination and prejudice, and microtransformations, which focus on creating systemic changes to improve the quality of life for all QTPOC. For example, Jane, a 36-year-old queer Black woman, discussed how educators can implement microtransformations by using their influence to normalize queer identities within the classroom:

I feel like if we were to learn about [QTPOC] as historical figures and learn about them, like in health class for example, it would help us in other interpersonal contexts and making relationships. It would also normalize treating [QTPOC] as people and with kindness.

Jane’s reflection illustrates the potential for microtransformations to contribute to systemic shifts in how QTPOC are viewed and treated in society. Participants at this later stage of identity development sought microaffirmations that not only validated their personal identities but also fostered more inclusive environments through microprotections and broader societal shifts. These microprotections, such as inclusive policies in schools or workplaces, safeguard QTPOC from harmful discrimination, while microtransformations create opportunities for long-term structural changes that challenge structural inequities and create more affirming environments for QTPOC.

Safety with Others

The theme safety with others represented participants’ experiences of how microaffirmations, particularly microvalidations and microrecognitions, signaled safety in their external environments, indicating that they could express their identities without fear or discrimination. Many participants spoke about the importance of microaffirmations being a way to subtly indicate that an area or person in their external environment is less likely to discriminate, alienate, or be violent toward them. Lucia, a 26-year-old gender-expansive queer Filipino, highlighted the role of microrecognitions in fostering a sense of security: “Microaffirmations communicate safety to me, like, say, from my external environment, that I can then disclose, fully disclose, who I actually am to people . . . So [microaffirmations] are definitely an aspect of safety and being out or not.” For Lucia, small but significant acts of recognition, such as visual cues or verbal affirmations from others, provided reassurance that their identity would be accepted and protected in that space. Similarly, D, a 28-year-old lesbian/demisexual Black woman, shared that microvalidations, such as seeing the Pride flag displayed in public spaces, gave her a sense of immediate comfort and safety: “I can breathe and relax and like, oh, I can exist in this space.” These microvalidations, subtle yet powerful, signaled that the space was affirming and protective of her identity.

Beyond personal safety, participants also reflected on the protective role of microprotections. Some participants, like Jane, described how microprotections in her environment gave her confidence that she would not be alone if a negative situation occurred: “[Microaffirmations] were a sign that there was some kind of protection and backup, that if something goes wrong, that I’m not in it by myself . . . I’m not going to be piled on . . . or outwardly rejected.” This sentiment highlights how microprotections create a sense of communal support, with which participants know that others will ally with them in moments of potential conflict or discrimination. Stacey, a 29-year-old bisexual African American and Caribbean American woman, elaborated on how the cumulative effect of microaffirmations contributed to her overall sense of safety: “When you have more microaffirmations than aggressions . . . you, I, tend to feel safer.” In this instance, Stacey underscored the idea that frequent experiences of affirmation—whether through microvalidations or microrecognitions—help mitigate the impact of microaggressions, allowing her to feel more secure in her identity. Oliver, a gay/queer Vietnamese man, further reflected on how the absence of microaffirmations could leave him feeling vulnerable: “If I didn’t have the experiences of microaffirmations that I did today, I would just feel . . . less mentally secure generally.” Oliver’s observation emphasizes the protective nature of microaffirmations, in that their presence contributed not only to a sense of physical safety but also to psychological security.

Envisioning Policy Changes

The theme envisioning policy changes captured participants’ reflections on the broader implications of microaffirmations, specifically their potential to influence policy and create systemic change. Participants shared their views on both the immediate benefits of microaffirmations and their limitations in addressing larger structural issues. The role of microaffirmations was seen as a necessary component of personal healing from the often-daily trauma of microaggressions but was not sufficient to address systemic inequities. Instead, participants stated that microaffirmations should serve as stepping stones toward inclusive laws and policies. Microprotections, such as individuals expressing their support for policies that provide legal safeguards and affirming spaces, were seen as critical for improving the well-being of QTPOC. Lucia advocated for increased health and gender-affirming care protections: “We need increased protections for health and gender-affirming care, and not just in certain states but nationally.” Lucia’s desire for more inclusive policies highlights the role of microprotections in safeguarding the rights and well-being of QTPOC at a systemic level. Similarly, Stacey emphasized the need for broader legal changes to contend with book bans and the censorship of LGBTQIA+ content in public schools:

I find book bans and the banning of specific conversations in public schools to be very harmful. I primarily work with adolescents and their families, and I believe a lot of stuff starts in childhood, and if we are sending the message to children that queer people shouldn’t exist or that we can’t talk about it, it creates generations of harm.

Stacey’s reflection illustrates how microprotections can counteract systemic exclusion and ensure that QTPOC youth are represented and affirmed in public education.

Microtransformations, on the other hand, were described as the support for far-reaching changes in policies and societal norms that would fundamentally improve the daily lives of QTPOC. Kay, a bisexual/queer Black/Afro-Caribbean woman, noted that while microaffirmations were helpful in buffering the effects of daily microaggressions, they were not enough to dismantle deeply embedded systemic oppression:

So, I think microaffirmations are a buffer to all the aggressions, violence, harm, and trauma that’s happening consistently, but it doesn’t necessarily erase the harm and the violence. But it does provide, at least for me, a buffer mentally. Because I feel if I experience a microaggression, and if I internalize it, that can add to deeper trauma. And microaffirmations can help me externalize that and know that even though it hurts, that it’s not me. I’m not gonna sit in that with that person. And so, I think it’s a great buffer.

Kay’s awareness of the limitations of microaffirmations underscores the importance of advocating for systemic reforms that extend beyond individual or community-level affirmations. There was a marked urgency in advocating for national-level policy changes, such as the expansion of health care access and “full adoption rights for same-sex parents” (Baohua, a 36-year-old gay Asian man). Baohua’s comments reflect the urgent need for uniform protections and policies that support QTPOC regardless of geographic location. Dwayne, a 46-year-old Black gay man, similarly advocated for accessible and inclusive mental health care services as a form of microtransformation, stating that “Making mental health care more accessible and acceptable for all of us should be a priority.” Dwayne’s insight connects microtransformations to health equity, pointing out that long-term systemic improvements are needed to ensure that QTPOC have equal access to health services. Ultimately, dissatisfaction with current policies was prevalent, with participants advocating for equitable reforms that go beyond affirming language and instead target holistic care. Some found it challenging to specify exact policies but envisioned that supportive policies would enhance their well-being and enable easier connections, more energy, and fuller participation in daily life.

Representation

The theme of representation reflected participants’ experiences of engaging with microaffirmations that represent their lived experiences as QTPOC from external sources through visual or vocal cues, as well as participants’ creation of their own microaffirming external sources for others to feel represented through.

External Representation

Representation that was received or seen via microvalidations and microrecognitions was critical in helping participants feel affirmed in their racial/ethnic and gender/sexual identities. J, a 31-year-old bisexual Filipino man, emphasized how social media representations during Pride Month and Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month made him feel both his queer and racial identities were not only seen but celebrated:

What comes to mind right away is just Instagram stories and just seeing most of my timeline having some sort of Pride tag or Pride sticker on their stories . . . And also last month during AAPI Heritage Month, those Instagram stories and having the little sticker—it’s really nice to see a bunch of signs of like, “hey, we’re celebrating you!” and “hey, I’m a part of this group too!”

For J, these microrecognitions on social media provided him with a sense of visibility and belonging, reinforcing that the community valued his intersectional identity. Participants throughout shared that visible external representation like affirming signage, Pride flags, racially and LGBTQIA+ diverse TV shows such as Heartstopper, LGBTQIA+ bumper stickers, hashtags, social media posts, and even seeing LGBTQIA+ folks being successful in a variety of different careers were viewed as affirming of their queer identities. Having external representation through a variety of sources not only made participants feel like their identities were being celebrated, but some participants, like Kay, also believed that external representations are microprotections that are “counteracting or disrupting” people from being “harmful” and deterring discrimination.

Created Representation

Though experiencing representation was important, many found that actively creating microaffirmations and making their own representation for themselves and others was also imperative to their well-being. Many saw themselves as change agents, contributing to microtransformations by normalizing conversations about their sexual and gender identities, establishing safe spaces, and engaging in activism that benefited other QTPOC. Dwayne spoke about how his life journey recently involved stepping into a leadership role, in which he felt responsible for creating representation for others:

I guess . . . when it comes to people who are capable of trying to help others, [they realize] that there is sometimes a shortage of people who can be that spokesperson, or be that leader, to be that example, or that exemplary person. They can be in the forefront. . . . And so, I think where I’m at now, just in my life journey, is that . . . I’m coming into that space.

By creating visibility for himself, Dwayne was actively contributing to the creation of microtransformations. Stacey shared the importance of fostering inclusivity for future generations, particularly her children. She explained how creating affirming spaces at home, such as by exposing her children to diverse representations of queer families, was a way to contribute to future microprotections: “[I want to] have them reading books and you know, expose them to other queer families and let them know that this is normal.” By normalizing having conversations about the LGBTQIA+ community, not only is knowledge being shared, but the likelihood increases that youth who may resonate with identities within the community may experience less queer- and race-related microaggressions than their predecessors (Houshmand et al., 2019).

Internalization of Perceived Worth

The theme internalization of perceived worth not only highlighted participants’ internalization of microaffirmations regarding their individual and collective sense of worth but also how the source of these microaffirmations influenced their impact. Microvalidations were often described as contributing to their mental and emotional well-being. For example, Didi, a 27-year-old bisexual Latina woman, shared how microaffirmations helped her feel less overwhelmed and more validated in her identity: “[Microaffirmations] really help me feel validated and, in terms of mental health, I feel like it makes me feel less overwhelmed.” For Didi, these microvalidations provided emotional support that helped her manage the daily stressors associated with navigating stigma and other social barriers. Microrecognitions were also described as crucial in helping participants internalize a sense of worth. For some, like Nick, a 27-year-old gay Black man, internalized validation from microaffirmations not only makes participants feel like their identities as QTPOC are valid but may also provide QTPOC with “better mental health.” QL, a 29-year-old queer gender-expansive Chinese person, also spoke about how microaffirmations helped with their mental well-being and made them feel “affirmed” and “really good,” and that “in some ways it helps with the anxiety. It helps with the depression.”

Another aspect of the theme internalization of perceived worth involves the source of microaffirmations, which influenced how deeply these affirmations impacted their sense of self-worth. Microaffirmations from people with shared or similar identities were particularly meaningful, as these individuals could better understand and relate to the participants’ experiences. April explained that she primarily found validation for her identity within her relationship: “I feel that affirmation of my identifying as demisexual primarily only comes from my own relationship [with my partner].” For April, the microaffirmations she received from her partner were more impactful than those from others because they were rooted in a shared understanding of her identity and experiences. Similarly, Kay shared that the most meaningful microaffirmations often come from her queer friends who share similar marginalized identities: “The microaffirmations carry more weight when they come from my friends who are queer and/or genderfluid or trans . . . because I feel like we all know what we’re going through and we can all support each other.”

This idea that internalized perceived worth or validation comes from those with similar queer and/or trans and racial/ethnic identities was also expressed by Baohua when he described the microaffirmations he received from his friends who also identify as QTPOC, despite cultural differences:

Or maybe they experience some challenges, and I feel like that’s relatable. It’s like . . . we’re speaking in the same language. We’re experiencing similar things. . . . That kind of gives me . . . like different validation to say, hey, we are here, right? Even though that’s very old—we’re here, we’re queer, whatever. But it’s like we are here, and we are living life despite different social or political challenges that we’re facing.

Baohua’s statement highlights how microrecognitions from peers with similar identities can bolster one’s sense of worth and community, reinforcing the idea that they are not alone in their experiences.

Discussion

All 14 participants expressed various experiences of microaffirmations as queer and/or transgender people of color. Themes found in this study’s results (i.e., influence of identity development, safety with others, envisioning policy changes, representation, and internalization of perceived worth) align with and expand on the growing body of literature on microaffirmations’ role in the LGBTQIA+ community (Anzani et al., 2019; Flanders et al., 2019; Pulice-Farrow et al., 2019; Sterzing & Gartner, 2020) and marginalized racial/ethnic communities (Pérez Huber et al., 2021; Rolón-Dow & Davison, 2021). Despite the topic of microaffirmations becoming more prevalent in scholarly literature, there is still a dearth of research that looks at defining and understanding the impacts of microaffirmations for those with both marginalized gender and/or sexual identities and marginalized racial/ethnic identities. Elements of Rolón-Dow and Davison’s subcategories of microaffirmations were used as a foundation for this study’s current superordinate themes.

For the theme of influence of identity development, participants discussed their experiences with microaffirmations that supported and validated their individual identity and other microaffirmations that applied to the broader queer community. For those in the earlier stages of their identity development, the presence of microaffirmations seemed to mitigate any internalized conflict or discrimination related to their queer identities, compared to those in later stages of identity development. These findings aligned with various LGBTQIA+ identity development models, such as D’Augelli’s (1994) Model of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Identity Development and the Model of Multiple Dimensions of Identity (Abes et al., 2007). It seemed that participants who were in the earlier stages of their queer and/or transgender identity development found microaffirmations to be more impactful when they were directed toward them as individuals versus those who were in later stages and had a more community/systemic viewpoint. The differences in identity developmental stages may also be explained by Roberts and Christens (2020), who reported that Black and Latinx participants, when “out,” experienced positive outcomes when they experienced a sense of connectedness to the LGBTQIA+ community. The results of this study (Roberts & Christens, 2020) suggest that those in later stages of development based on how “out” they are may have more ties to other QTPOC. Similar findings from Ghabrial and Andersen (2021) and G. Smith and colleagues (2022) further support the positive impact of community connectedness on participants’ experiences. Perhaps participants in later stages of their identity development are more likely to be out and intentional about finding QTPOC spaces, therefore feeling more validated by microaffirmations directed at the broader queer community instead of those targeting them individually.

For the theme safety with others, participants emphasized their experiences with microaffirmations that signaled safe spaces, individuals, and organizations. This theme aligns with Rolón-Dow and Davison’s (2021) subcategories of microaffirmations, specifically microvalidations and microprotections. Hudson and Romanelli’s (2020) findings, which highlight the fostering of safety and acceptance by the LGBTQ community as a strength and health-promoting factor for LGBTQ adults of color, align with this theme. Participants mentioned that being around other QTPOC allowed them to fully disclose their sexual and gender identities and authentically be themselves. Though participants primarily focused on feelings of safety regarding their marginalized sexual and/or gender identities, many, like Baohua, also mentioned examples of microaffirmations that validated and instilled feelings of safety for both these identities and their racial/ethnic identities. The microaffirmations could potentially reduce the negative mental health–related issues experienced by the participants in this study (Topor et al., 2018).

Regarding the theme envisioning policy changes, participants reflected on the broader implications of microaffirmations and their potential to influence policy and create systemic change. They shared that these microaffirmations also provided immediate benefits, supporting previous literature which reported that gender-affirming policies are associated with positive mental health outcomes among transgender individuals (Horne et al., 2022). However, many of our participants discussed the impact of current anti-LGBTQIA+ legislation and the potential effects of future legislation at both the federal and local levels on the LGBTQIA+ community. Similar to the theme influence on identity development, the centrality of community connectedness and protection was evident when participants talked about both current and future policy changes. This is supported by Hudson and Romanelli (2020), who proposed that QTPOC have a future orientation focused on investing in and improving opportunities for health and well-being for current and future community members. The fourth theme, microaffirmations as representation, was shared by participants as external representations from outside sources, as well as how participants themselves created microaffirmations for others. While previous literature (McInroy & Craig, 2017) also identified external representations of QTPOC, many participants also underlined the importance of being the provider of various forms of microaffirmations. Participants emphasized the importance of actively generating microaffirmations that provided representation for other QTPOC folks. These examples included conducting affirmative research on QTPOC, compiling resources with positive QTPOC representation, and stepping into leadership roles in the LGBTQIA+ community. Hudson and Romanelli (2020) noted that QTPOC involved in activism and advocacy were more likely to be aware of structural and social injustices that can negatively impact the well-being of individuals in the LGBTQIA+ community.

The final theme, internalization of perceived worth focuses on how microaffirmations are internalized and shape participants’ sense of self and collective worth, as well as the impact of microaffirmations based on participants’ relationship with the giver of the microaffirmations. Ghabrial (2019) suggests that for marginalized individuals, feeling that one’s marginalized identity can be viewed as a positive aspect can foster resilience and resolve when experiencing discrimination. This may explain why participants such as Didi felt less overwhelmed and participants like Stacey felt hope when receiving microaffirmations. For these two participants, their positive viewpoints on their sexual identities encouraged them not only in their identities but also in advocating for themselves and other QTPOC. Microaffirmations may therefore be one reason why QTPOC feel motivated to participate in advocacy efforts. Another element of this theme that participants discussed is the impact of internalizing perceived worth depending on the source of the microaffirmation. While microaffirmations from anyone were appreciated, some participants emphasized the positive impact of microaffirmations received from those within the LGBTQIA+ community or from close relationships, whether platonic, familial, or romantic. In a study focusing on transgender individuals and their romantic relationships, Pulice-Farrow and colleagues (2019) reported that participants found microaffirmations more meaningful when they came from romantic partners rather than strangers, as it affirmed the importance of the relationship. This idea also expands on the work by Delston (2021), who suggested that individuals from vulnerable groups seek environments where they feel valued, appreciated, and included. Delston also warns that microaffirmation recipients should be aware of where and from whom they receive microaffirmations, as they may be influenced to make life decisions based on biased external influences, such as a QTPOC only having their identity affirmed by limiting White LGBTQIA+ sources. This study’s findings indicate that microaffirmations from those in close relationships with QTPOC may have a greater impact than those from strangers or large organizations, highlighting the necessity for QTPOC to be cautious of the giver of microaffirmations and the importance of QTPOC to create intentional and affirming support systems.

Implications for Counselors

Given the nuanced understanding of microaffirmations and their profound impact on QTPOC, counselors working with this population can draw several practice implications to foster resilience and improve mental health outcomes. First, it is essential for counselors to recognize the various stages of identity development their QTPOC clients may be undergoing. Clients in the early stages of identity development may benefit significantly from microvalidations and microrecognitions that affirm their identities and experiences, helping them navigate internalized discrimination. Engaging in active listening, providing reflections and follow-up questions, and validating clients’ feelings and identities are vital strategies for those still exploring their sexual and gender identities.

Counselors must also establish environments where QTPOC clients feel safe and affirmed. This can be achieved by incorporating visible signs of support, such as Pride flags or inclusive posters, and using affirming language that communicates safety. Counselors must also check their biases, assumptions, and competencies around QTPOC identities and how they intersect (e.g., continuing education, LGBTQ+/QTPOC affirming supervision/consultation). As Delston (2021) proposed, microaffirmations may influence a person’s decisions based on who and where they came from. Well-intentioned counselors may further perpetuate harmful stereotypes or affirm QTPOC clients from a narrow White, Western perspective that limits influence from these clients’ racial/ethnic background, thereby creating an unsafe environment.

Furthermore, counselors should understand the importance of advocating for inclusive policies. Outside of sessions, counselors can educate themselves and advocate for pro-LGBTQIA+ legislation that would benefit QTPOC. By engaging in advocacy and policy work, counselors can help create a safe and supportive environment that extends beyond the counseling office. Counselors can also seek out positive representations of QTPOC in media, which may allow them to be better able to connect with clients in session by demonstrating their understanding of social and cultural references. However, non-QTPOC counselors should engage with those materials in good faith and avoid performative advocacy with clients, such as having Pride flags hanging in their office but not having resources specific to the needs of QTPOC clients. Moreover, in session, counselors can help clients outline close relationships and safe spaces affirming QTPOC clients’ identities and refer clients with limited support to QTPOC resources locally and virtually. Counselors can also incorporate expressive art therapy techniques into sessions that provide QTPOC clients creative outlets that allow them to not only express themselves but also to be productive by sharing their creations with others as a form of authentic queer representation (Buttram, 2015).

Finally, counselors can support QTPOC clients in fostering internalized worth by consistently using affirming language, adopting a strengths-based approach, and facilitating connections with other QTPOC via group counseling services or within the community. Providing psychoeducation about the impact of discrimination along with employing narrative counseling techniques can help clients reframe their personal stories. By recognizing the unique experiences and needs of QTPOC clients, counselors can play a pivotal role in fostering environments that promote mental health, resilience, and a strong sense of worth, both on an interpersonal, therapeutic level and within the broader societal context.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study, while providing valuable insights into the role of microaffirmations for QTPOC, has several limitations that should be noted. During the time of interviews, most participants identified as cisgender, their gender identity aligning with their sex assigned at birth, providing limiting perspectives of those with gender-expansive identities. Most participants were also Millennials (born 1981 to 1996) and older Gen Zs (born 1997 to 2010; Dimock, 2019), which limits perspectives of what may be considered microaffirmations from older generations of QTPOC who historically experienced less and/or different affirmations in their lives. Future research should aim to include a larger and more diverse sample to enhance the generalizability of the findings.

Another limitation of this study was that it did not ask participants for their regional location. Though some participants shared where they lived in their interviews, knowing regional locations may have helped to understand if participants from similar regions experienced similar types and frequency of microaffirmations. Future research should explore the experiences of QTPOC in specific geographical regions and cultural settings to capture and compare regional differences.

An additional crucial limitation is that, though the study did require participants to be currently living in the United States, there were a few participants who were either immigrants who had lived part of their developmental years in another country or were international students who came to the United States later in life. Though these participants shared their experiences, interview questions did not consider the added marginalized identities of being an immigrant/non–U.S. citizen. Future research is warranted to investigate the utility of microaffirmations for undocumented or non–U.S. citizen QTPOC. Lastly, there is a need for more intervention-based research to develop and test specific counseling strategies that effectively utilize microaffirmations to support QTPOC clients.

Conclusion

This study expanded understanding of the different subcategories of microaffirmations within the context of multiple marginalized identities, specifically being a person of color and being LGBTQIA+. The findings illustrate QTPOC perceptions of microaffirmations and their significant impact on their mental well-being. Efforts should be made to further understand the lasting impact of microaffirmations for individuals with multiple marginalized identities and how microaffirmations can encourage QTPOC and others to make macro-level changes. Counselors and researchers have a vital role in identifying and fostering microaffirmations for QTPOC across various aspects of their work.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Abes, E. S., Jones, S. R., & McEwen, M. K. (2007). Reconceptualizing the model of multiple dimensions of identity: The role of meaning-making capacity in the construction of multiple identities. Journal of College Student Development, 48(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2007.0000

Anzani, A., Morris, E. R., & Galupo, M. P. (2019). From absence of microaggressions to seeing authentic gender: Transgender clients’ experiences with microaffirmations in therapy. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 13(4), 258–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2019.1662359

Bostwick, W. B., Boyd, C. J., Hughes, T. L., West, B. T., & McCabe, S. E. (2014). Discrimination and mental health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84(1), 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0098851

Brooks, V. R. (1981). Minority stress and lesbian women. Lexington Books.

Buttram, M. E. (2015). The social environmental elements of resilience among vulnerable African American/Black men who have sex with men. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 25(8), 923–933. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2015.1040908

Cyrus, K. (2017). Multiple minorities as multiply marginalized: Applying the minority stress theory to LGBTQ people of color. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 21(3), 194–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/19359705.2017.1320739

D’Augelli, A. R. (1994). Identity development and sexual orientation: Toward a model of lesbian, gay, and bisexual development. In E. J. Trickett, R. J. Watts, & D. Birman (Eds.), Human diversity: Perspectives on people in context (pp. 312–333). Jossey-Bass.

Delston, J. B. (2021). The ethics and politics of microaffirmations. Philosophy of Management, 20(4), 411–429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40926-021-00169-x

DeLucia, R., & Smith, N. G. (2021). The impact of provider biphobia and microaffirmations on bisexual individuals’ treatment-seeking intentions. Journal of Bisexuality, 21(2), 145–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299716.2021.1900020

Dimock, M. (2019, January 17). Defining generations: Where Millennials end and Generation Z begins. Pew Research Center. www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2019/01/17/where-millennials-end-and-generation-z-begins

Dispenza, F., & O’Hara, C. (2016). Correlates of transgender and gender nonconforming counseling competencies among psychologists and mental health practitioners. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3(2), 156–164. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000151

Ellis, J. M., Powell, C. S., Demetriou, C. P., Huerta-Bapat, C., & Panter, A. T. (2019). Examining first-generation college student lived experiences with microaggressions and microaffirmations at a predominately White public research university. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 25(2), 266–279. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000198

Flanders, C. E. (2015). Bisexual health: A daily diary analysis of stress and anxiety. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 37(6), 319–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2015.1079202

Flanders, C. E., Shuler, S. A., Desnoyers, S. A., & VanKim, N. A. (2019). Relationships between social support, identity, anxiety, and depression among young bisexual people of color. Journal of Bisexuality, 19(2), 253–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299716.2019.1617543

Ghabrial, M. A. (2019). “We can shapeshift and build bridges”: Bisexual women and gender diverse people of color on invisibility and embracing the borderlands. Journal of Bisexuality, 19(2), 169–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299716.2019.1617526

Ghabrial, M. A., & Andersen, J. P. (2021). Development and initial validation of the Queer People of Color Identity Affirmation Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 68(1), 38–53. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000443

Hailey, J., Burton, W., & Arscott, J. (2020). We are family: Chosen and created families as a protective factor against racialized trauma and anti-LGBTQ oppression among African American sexual and gender minority youth. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 16(2), 176–191.

https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428x.2020.1724133

Horne, S. G., McGinley, M., Yel, N., & Maroney, M. R. (2022). The stench of bathroom bills and anti-transgender legislation: Anxiety and depression among transgender, nonbinary, and cisgender LGBQ people during a state referendum. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 69(1), 1–13.

https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000558

Houshmand, S., Spanierman, L. B., & De Stefano, J. (2019). “I have strong medicine, you see”: Strategic responses to racial microaggressions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 66(6), 651–664. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000372

Hudson, K. D., & Romanelli, M. (2020). “We are powerful people”: Health-promoting strengths of LGBTQ communities of color. Qualitative Health Research, 30(8), 1156–1170. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732319837572

Jones, J. M. (2024, March 13). LGBTQ+ identification in U.S. now at 7.6%. GALLUP. https://news.gallup.com/poll/611864/lgbtq-identification.aspx

Jones, J. M. & Rolón-Dow, R. (2018). Multidimensional models of microaggressions and microaffirmations. In G. C. Torino, D. P. Rivera, C. M. Capodilupo, K. L. Nadal, & D. W. Sue (Eds.), Microaggression theory: Influence and implications (pp. 32–47). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119466642.ch3

Lincoln, Y. S. & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. SAGE.

McConnell, E. A., Janulis, P., Phillips, G., II, Truong, R., & Birkett, M. (2018). Multiple minority stress and LGBT community resilience among sexual minority men. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 5(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000265

McInroy, L. B., & Craig, S. L. (2017). Perspectives of LGBTQ emerging adults on the depiction and impact of LGBTQ media representation. Journal of Youth Studies, 20(1), 32–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2016.1184243

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

Miller, M. J., Keum, B. T., Thai, C. J., Lu, Y., Truong, N. N., Huh, G. A., Li, X., Yeung, J. G., & Ahn, L. H. (2018). Practice recommendations for addressing racism: A content analysis of the counseling psychology literature. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 65(6), 669–680. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000306

Mizock, L., & Lundquist, C. (2016). Missteps in psychotherapy with transgender clients: Promoting gender sensitivity in counseling and psychological practice. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3(2), 148–155. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000177

Pérez Huber, L., Gonzalez, T., Robles, G., & Solórzano, D. G. (2021). Racial microaffirmations as a response to racial microaggressions: Exploring risk and protective factors. New Ideas in Psychology, 63, 100880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2021.100880

Pflum, S. R., Testa, R. J., Balsam, K. F., Goldblum, P. B., & Bongar, B. (2015). Social support, trans community connectedness, and mental health symptoms among transgender and gender nonconforming adults. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(3), 281–286. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000122

Pulice-Farrow, L., Bravo, A., & Galupo, M. P. (2019). “Your gender is valid”: Microaffirmations in the romantic relationships of transgender individuals. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 13(1), 45–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2019.1565799

Roberts, L. M., & Christens, B. D. (2020). Pathways to well-being among LGBT adults: Sociopolitical involvement, family support, outness, and community connectedness with race/ethnicity as a moderator. American Journal of Community Psychology, 67(3–4), 405–418. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12482

Rolón-Dow, R., & Davison, A. (2021). Theorizing racial microaffirmations: A Critical Race/LatCrit approach. Race Ethnicity and Education, 24(2), 245–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2020.1798381

Rowe, M. (2008). Micro-affirmations and micro-inequities. Journal of the International Ombudsman Association, 1(1), 45–48. https://mitsloan.mit.edu/shared/ods/documents?PublicationDocumentID=5404

Salim, S., Robinson, M., & Flanders, C. E. (2019). Bisexual women’s experiences of microaggressions and microaffirmations and their relation to mental health. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 6(3), 336–346. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000329

Smith, G., Robertson, N., & Cotton, S. (2022). Transgender and gender non-conforming people’s adaptive coping responses to minority stress: A framework synthesis. Nordic Psychology, 74(3), 222–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/19012276.2021.1989708

Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research. SAGE.

Sterzing, P. R., & Gartner, R. E. (2020). LGBTQ microaggressions and microaffirmations in families: Scale development and validation study. Journal of Homosexuality, 67(5), 600–619. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2018.1553350

Testa, R. J., Habarth, J., Peta, J., Balsam, K., & Bockting, W. (2015). Development of the Gender Minority Stress and Resilience Measure. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(1), 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000081

Topor, A., Bøe, T. D., & Larsen, I. B. (2018). Small things, micro-affirmations and helpful professionals everyday recovery-orientated practices according to persons with mental health problems. Community Mental Health Journal, 54, 1212–1220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-018-0245-9

White Hughto, J. M., Reisner, S. L., & Pachankis, J. E. (2015). Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Social Science & Medicine, 147, 222–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.010

Yardley, A. (2008). Piecing together—A methodological bricolage. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(2), Article 31. https://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/416/902

Zori A. Paul, PhD, NCC, LPC (MO), is a clinical assistant professor at Marquette University. Kyesha M. Isadore, PhD, NCC, CRC, is an assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Nishi Ravi, MCouns, is a doctoral student at Marquette University. Kayla D. Lewis, MS, is a doctoral student at Marquette University. Dewi Qisti, MS, is a doctoral student at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Alex Hietpas, MS, is a doctoral student at Marquette University. Bergen Hermanson, BA, is a master’s student at Marquette University. Yuji Su, BA, is a master’s student at Marquette University. Correspondence may be addressed to Zori A. Paul, Department of Counselor Education and Counseling Psychology, Schroeder Complex, 113M, Marquette University, P.O. Box 1881, Milwaukee, WI 53201-1881, zori.paul@marquette.edu.

Appendix

Interview Protocol

The interview will focus on details of participants’ experiences with microaffirmations. Participants will be asked how to describe everyday experiences and small actions that affirm their identities or impact their experiences; how different types of microaffirmations (microrecognitions, microvalidations, microtransformations, and microprotections) show up in their lives; and the impact of microaffirmations on their overall mental health and well-being. The goal of this interview is to elicit rich descriptions of participants’ experiences. The following questions and prompts will be used as a guide for the interview:

- Background Questions

a. Could you briefly explain how you refer to yourself in terms of your sexual and/or gender identity and what those labels, if you use any labels, mean to you?

b. Could you briefly explain how you refer to yourself in terms of your racial and/or ethnic identity and what those labels, if you use any labels, mean to you?

c. Can you describe a time when you felt like someone affirmed your sexual and/or gender identity?

i. If not already answered: What was your relationship to this person?

2. Microaffirmations

a. (Microrecognitions) Could you describe everyday experiences, such as actions, words, or environmental cues (like artwork, signage, symbols) that made you feel like your [insert identity] was given positive visibility and appreciation?

i. If you haven’t experienced that, what do you think positive visibility and appreciation for your identity would look like?

ii. In what ways do you think more positive visibility and appreciation for your identity would impact you directly?

b. (Microvalidations) Could you describe everyday experiences that made you feel that your thoughts, feelings, sensations, and/or behaviors associated with your lived experience as [identity] are accepted, legitimized, or given value?

i. If you haven’t experienced that, what do you think positive acknowledgment and understanding of your identity and lived experience would look like?

ii. In what ways do you think more positive acknowledgment and understanding would impact you directly?

c. (Microtransformations) Could you describe everyday experiences that made you feel that your identity as a member of [insert identity group] has been enabled, enhanced, or increased in society?

i. What do you think potential policies/initiatives that would enable, enhance, or increase your life look like?

ii. How would your life be impacted directly?

d. (Microprotections) Could you describe everyday experiences that make you feel shielded or protected from harmful or derogatory behaviors, practices, and policies tied to your identity as [insert identity]?

i. If you haven’t experienced that, what do you think potential protections or shields would look like?

ii. How would your life be impacted if you had more protection and shields?

3. Other

a. So far, we’ve been talking about positive everyday experiences that affirm your [identity]. The term we use for these everyday experiences and small actions is called microaffirmations. Can you tell us a little about the relationship of these microaffirmations with your overall mental health and well-being and how microaffirmations may impact it?

i. What do you think is the role of microaffirmations in terms of how you navigate spaces that have historically been exclusive to queer and trans people of color?

b. Is there anything we missed regarding any actions, words, or environmental cues you’ve experienced as [identity] throughout the course of your everyday life that affirms your identity and acknowledges your realized identity, and promotes social justice?

Dec 5, 2024 | Volume 14 - Issue 3

Russ Curtis, Lisen C. Roberts, Paul Stonehouse, Melodie H. Frick

Tattoo art is one of the earliest forms of self-expression, but the advent of colonialism, and its accompanying religious convictions, halted the practice in many Indigenous lands and led to widespread bias against tattooed people—a bias maintained to the present. How might the counseling profession respond to this residual bias and intentionally invoke a cultural shift destigmatizing tattoos? Through an extensive literature review, this article provides a more comprehensive understanding of tattoo-related mental health correlates, biases, and theories that enhance the effectiveness of counseling and parallel trends in the counseling profession that emphasize sociocultural influences on wellness. As a result of this survey, the authors propose a new theory of tattoo motivation, the unencumbered self theory of tattoos, which advances existing tattoo theory and aligns with current counseling trends by postulating that tattoos symbolize the uniquely human desire to transcend norms and laws imposed by external influences.

Keywords: tattoo, bias, mental health, theory, counseling

Imagine you are the parent of a 13-year-old girl. While at a parent–teacher conference, you learn your daughter is struggling with disruptive behavior and angry outbursts during class. The teacher asks if you would support your daughter seeing the school counselor and adds that the counselor is in the school building and available to speak with parents. You approach the counselor’s office, gently knock, and are welcomed by a warm, feminine-presenting adult. As the counselor offers their hand to shake, you notice an entirely tattooed forearm, and as you greet their eyes, more ink is evident on their neck.

What feelings, assumptions, or concerns emerge as you put yourself in the place of the parent in the above vignette? Despite the recent popularization of tattoos, a bias remains. Current research indicates that nearly half of adults in the United States between the ages of 18–34 have at least one tattoo (Roggenkamp et al., 2017), and the tattoo business is one of the fastest-growing enterprises, producing over a billion dollars in annual revenue (Zuckerman, 2020). This trend in tattoo art transcends the United States and is evident throughout the world (Ernst et al., 2022; Khair, 2022; Roberts, 2016). Nevertheless, bias against tattooed people remains, and women and people of color receive the brunt of this discrimination (Baumann et al., 2016; Guéguen, 2013; Kaufmann & Armstrong, 2022; Khair, 2022; Roberts, 2016). Given this meteoric resurgence in tattoo art and the discrimination that clings to it, implications for counseling practice inevitably exist.

Professional questions relevant to the counseling practice include: Is there a relationship between a desire for a tattoo and mental health? What motivates a person to seek a tattoo? In what ways may a tattoo bias subconsciously shape a counselor’s interactions with a client? How might the counseling community communicate a spirit of inclusion to the tattooed? To address these questions, this article employs the following structure. First, we provide a context for this bias by briefly examining the history and cultural perspectives of tattoos. Second, to establish the importance of this issue, we empirically demonstrate the reality of tattoo bias. Third, with this history of bias in mind, we comb the literature for research that explores the relationship between mental health and tattoos. Fourth, these relationships offer a frame of reference for our survey of established tattoo motivation theories, to which we propose an additional theory, the unencumbered self theory of tattoos, and reveal its significance within a clinical setting via a case study. Fifth, before concluding the article, we demonstrate how our inquiry’s content might be applied by enumerating our argument’s implications for the counseling profession.

Historical and Cultural Perspectives of Tattoos

The word tattoo originates from the Samoan term tatau, meaning “to tap lines on the body.” The practice of tattooing is known to have existed as early as 7000 BC, as seen on Egyptian mummies (Rohith et al., 2020). Otzi the Ice Man, dating back to 3000 BC, was discovered in 1991 with tattoos on his arms and wrist that are thought to have been applied for therapeutic purposes, a potential precursor to acupuncture (Schmid, 2013). Prior to the colonization of Indigenous lands by European countries, many tribes practiced the art of tattoo to symbolize adulthood, tribal membership, and status (Dance, 2019; Thomas et al., 2005). However, with the emergence of European imperialism, colonizers taught Indigenous people that tattoos were an abomination, scripturally prohibited, and therefore immoral. For instance, in The Holy Bible (New International Version, 1978, Leviticus 19:28) and The Qur’an (2004, Surah 7:46), specific passages forbid marking the skin.

Despite these condemnations, the practice of tattooing was not eradicated. Many cultures continued their tattoo traditions, and modern culture has adopted new traditions, which are even now expanding throughout the world (Ernst et al., 2022; Khair, 2022; Roberts, 2016). Although there is much intergroup variability, cultural identity can influence the motivation for and type of preferred tattoo. In India, for instance, tattoos often depict unique patterns specific to different tribal regions in the country. Specifically, in urbanized Indian geographic areas, there is increasing integration of tribal pattern tattoos with Western-influenced designs (Rohith et al., 2020). In Samoan culture, men receive an intricate tattoo called a pe’a while women receive a malu, both to indicate maturity (Dance, 2019). Lest the cultural importance of Indigenous tattoos be doubted, their misappropriation has resulted in litigation, thereby challenging attorneys to consider the property rights of tattoo designs (Tan, 2013).

Profoundly relevant to counseling, tattoos are often representational and symbolize something of importance. In a recent qualitative study of tattooed Middle Eastern women, Khair (2022) discovered themes related to taking ownership of their bodies in a patriarchal society and symbolism of their strength and desire to break free of patriarchal rules and religious mandates. In the United States, a study of mixed-race Americans’ tattoos revealed the most common tattoo themes include animal images and text of personally meaningful messages (Sims, 2018). In yet another group, White supremacists often get swastikas, crossed hammers, Confederate flags, and embellished Celtic crosses (Southern Poverty Law Center, 2006). Similarly, in Czech Republic prisons, the skull tattoo is a symbol representing neo-Nazi extremism, which then informs prison officials of inmates potentially becoming radicalized (Vegrichtová, 2018).