Feb 7, 2022 | Volume 12 - Issue 1

Clare Merlin-Knoblich, Jenna L. Taylor, Benjamin Newman

Social justice is a paramount concept in counseling and supervision, yet limited research exists examining this idea in practice. To fill this research gap, we conducted a qualitative case study exploring supervisee experiences in social justice supervision and identified three themes from the participants’ experiences: intersection of supervision experiences and external factors, feelings about social justice, and personal and professional growth. Two subthemes were also identified: increased understanding of privilege and increased understanding of clients. Given these findings, we present practical applications for supervisors to incorporate social justice into supervision.

Keywords: social justice, supervision, case study, personal growth, practical applications

Social justice is fundamental to the counseling profession, and, as such, scholars have called for an increase in social justice supervision (Ceballos et al., 2012; Chang et al., 2009; Collins et al., 2015; Dollarhide et al., 2018, 2021; Fickling et al., 2019; Glosoff & Durham, 2010). Although researchers have studied multicultural supervision in the counseling profession, to date, minimal research has been conducted on implementing social justice supervision in practice (Dollarhide et al., 2021; Fickling et al., 2019; Gentile et al., 2009; Glosoff & Durham, 2010). In this study, we sought to address this research gap with an exploration of master’s students’ experiences with social justice supervision.

Social Justice in Counseling

Counseling leaders have developed standards that reflect the profession’s commitment to social justice principles (Chang et al., 2009; Dollarhide et al., 2021; Fickling et al., 2019; Glosoff & Durham, 2010). For instance, the American Counseling Association’s ACA Code of Ethics (2014) highlights the need for multicultural and diversity competence in six of its nine sections, including Section F, Supervision, Training, and Teaching. Additionally, in 2015, the ACA Governing Council endorsed the Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies (MSJCC), which provide a framework for counselors to use to implement multicultural and social justice competencies in practice (Fickling et al., 2019; Ratts et al., 2015). All of these standards reflect the importance of social justice in the counseling profession (Greene & Flasch, 2019).

Social Justice Supervision

Although much of the counseling profession’s focus on social justice emphasizes counseling practice, social justice principles benefit supervisors, counselors, and clients when they are also incorporated into clinical supervision. In social justice supervision, supervisors address levels of change that can occur through one’s community using organized interventions, modeling social justice in action, and employing community collaboration (Chang et al., 2009; Dollarhide et al., 2021; Fickling et al., 2019). These strategies introduce an exploration of culture, power, and privilege to challenge oppressive and dehumanizing political, economic, and social systems (Dollarhide et al., 2021; Fickling et al., 2019; Garcia et al., 2009; Glosoff & Durham, 2010; Pester et al., 2020). Moreover, participating in social justice supervision can assist counselors in developing empathy for clients and conceptualizing them from a systemic perspective (Ceballos et al., 2012; Fickling et al., 2019; Kiselica & Robinson, 2001). When a supervisory alliance addresses cultural issues, oppression, and privilege, supervisees are better able to do the same with clients (Chang et al., 2009; Dollarhide et al., 2021; Fickling et al., 2019; Glosoff & Durham, 2010). Thus, counselors become advocates for clients and the profession (Chang et al., 2009; Dollarhide et al., 2021; Gentile et al., 2009; Glosoff & Durham, 2010).

Chang and colleagues (2009) defined social justice counseling as considering “the impact of oppression, privilege, and discrimination on the mental health of the individual with the goal of establishing equitable distribution of power and resources” (p. 22). In this way, social justice supervision considers the impact of oppression, privilege, and discrimination on the supervisee and supervisor. Dollarhide and colleagues (2021) further simplified the definition of social justice supervision, stating that it is “supervision in which social justice is practiced, modeled, coached, and used as a metric throughout supervision” (p. 104). Supervision that incorporates a focus on intersectionality can further support supervisees’ growth in developing social justice competencies (Greene & Flasch, 2019).

Literature about social justice supervision often includes an emphasis on two concepts: structural change and individual care (Gentile et al., 2009; Lewis et al., 2003; Toporek & Daniels, 2018). Structural change is the process of examining, understanding, and addressing systemic factors in clients’ and counselors’ lives, such as identity markers and systems within family, community, school, work, and elsewhere. Individual care acknowledges each person within the counseling setting independent of their environment (Gentile et al., 2009; Roffman, 2002). Scholars advise incorporating both concepts to address power, privilege, and systemic factors through social justice supervision (Chang et al., 2009; Gentile et al., 2009; Glosoff & Durham, 2010; Greene & Flasch, 2019; Pester et al., 2020).

It is necessary to distinguish social justice supervision from previous literature on multicultural supervision. Although similar, these concepts are different in that multicultural supervision emphasizes cultural awareness and competence, whereas social justice supervision brings attention to sociocultural and systemic factors and advocacy (Dollarhide et al., 2021; Fickling et al., 2019; E. Lee & Kealy, 2018; Peters, 2017; Ratts et al., 2015). For instance, a supervisor practicing multicultural supervision would be aware of a supervisee’s identity markers, such as race, ethnicity, and culture, and address those components throughout the supervisory experience, whereas a supervisor practicing social justice supervision would also consider systemic factors that impact a supervisee, in addition to being culturally competent. The supervisor would use that knowledge in the supervisory alliance and act as a change agent at individual and community levels (Chang et al., 2009; Dollarhide et al., 2021; Fickling et al., 2019; Gentile et al., 2009; Glosoff & Durham, 2010; E. Lee & Kealy, 2018; Lewis et al., 2003; Peters, 2017; Ratts et al., 2015; Toporek & Daniels, 2018).

Researchers have found that multicultural supervision contributes to more positive outcomes than supervision without consideration for multicultural factors (Chopra, 2013; Inman, 2006; Ladany et al., 2005). For example, supervisees who participated in multicultural supervision reported that supervisors were more likely to engage in multicultural dialogue, show genuine disclosure of personal culture, and demonstrate knowledge of multiculturalism than supervisors who did not consider multicultural concepts in supervision (Ancis & Ladany, 2001; Ancis & Marshall, 2010; Chopra, 2013). Supervisees also reported that multicultural considerations led them to feel more comfortable, increased their self-awareness, and spurred them on to discuss multiculturalism with clients (Ancis & Ladany, 2001; Ancis & Marshall, 2010). Although parallel research on social justice supervision is lacking, findings on multicultural supervision are a promising indicator of the potential of social justice supervision.

Models

In recent years, scholars have called for social justice supervision models to integrate social justice into supervision (Baggerly, 2006; Ceballos et al., 2012; Chang et al., 2009; Collins et al., 2015; Glosoff & Durham, 2010; O’Connor, 2005). However, to date, only three formal models of social justice supervision have been published. Most recently, Dollarhide and colleagues (2021) recommended a social justice supervision model that can be used with any supervisory theory, developmental model, and process model. In this model, the MSJCC are integrated using four components. First, the intersectionality of identity constructs (i.e., gender, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, abilities, etc.) is identified as integral in the supervisory triad between supervisor, counselor, and client. Second, systemic perspectives of oppression and agency for each person in the supervisory triad are at the forefront. Third, supervision is transformed to facilitate the supervisee’s culturally informed counseling practices. Lastly, the supervisee and client experience validation and empowerment through the mutuality of influence and growth (Dollarhide et al., 2021).

Prior to Dollarhide and colleagues’ (2021) model for social justice supervision, Gentile and colleagues (2009) proposed a feminist ecological framework for social justice supervision. This model encouraged the understanding of a person at the individual level through interactions within the ecological system (Ballou et al., 2002; Gentile et al., 2009). The supervisor’s role is to model socially just thinking and behavior, create a climate of equality, and implement critical thinking about social justice (Gentile et al., 2009; Roffman, 2002).

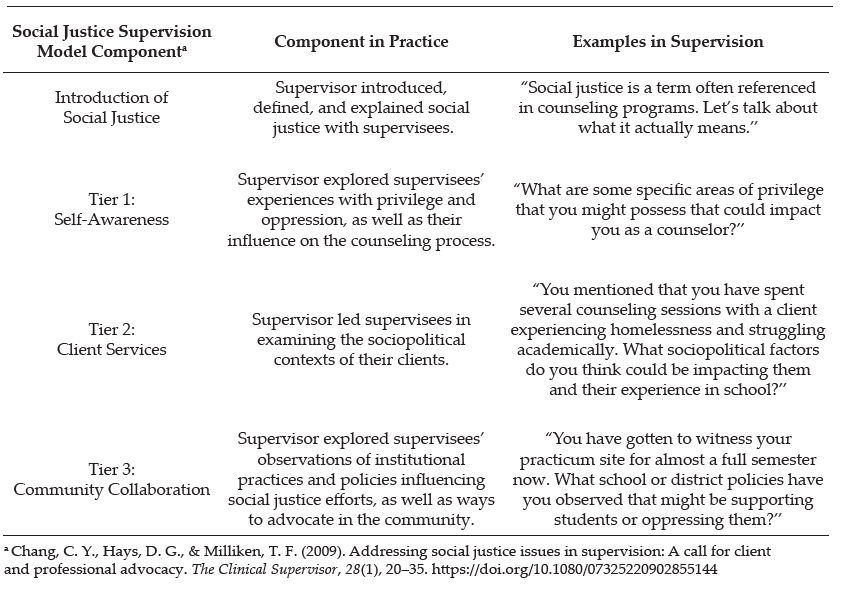

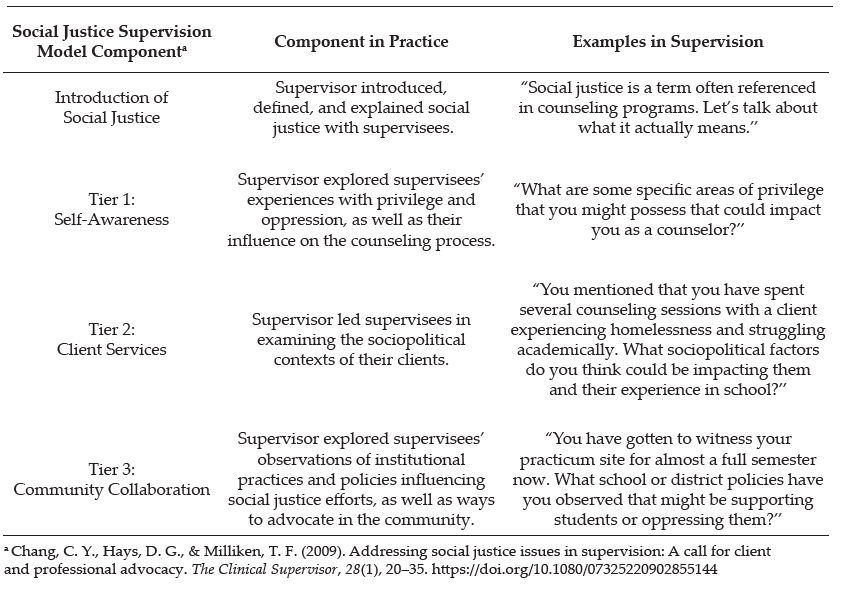

Lastly, Chang and colleagues (2009) suggested a social constructivist framework to incorporate social justice issues in supervision via three delineated tiers (Chang et al., 2009; Lewis et al., 2003; Toporek & Daniels, 2018). In the first tier, self-awareness, supervisors assist supervisees to recognize privileges, understand oppression, and gain commitment to social justice action (Chang et al., 2009; C. C. Lee, 2007). In the second tier, client services, the supervisor understands the clients’ worldviews and recognizes the role of sociopolitical factors that can impact the developmental, emotional, and cognitive meaning-making system of the client (Chang et al., 2009). In the third tier, community collaboration, the supervisor guides the supervisee to advocate for changes on the group, organizational, and institutional levels. Supervisors can facilitate and model community collaboration interventions, such as providing clients easier access to resources, participating in lobbying efforts, and developing programs in communities (Chang et al., 2009; Dinsmore et al., 2002; Kiselica & Robinson, 2001).

Each of these supervision models serves as a relevant, accessible tool for counseling supervisors to use to incorporate social justice into supervision (Chang et al., 2009, Dollarhide et al., 2021; Gentile et al., 2009). However, researchers lack an empirical examination of any of the models. To address this research gap and begin understanding social justice supervision in practice, the present qualitative case study exploring master’s students’ experiences with social justice supervision was undertaken.

We selected Chang and colleagues’ (2009) three-tier social constructivist framework in supervision for several reasons. First, the social constructivist framework incorporates a tiered approach similar to the MSJCC (Ratts et al., 2015) and reflects social justice goals in the profession of counseling (Ceballos et al., 2012; Chang et al., 2009; Collins et al., 2015; Glosoff & Durham, 2010). Second, the model is comprehensive. In using three tiers to address social justice (self, client, and community), the model captures multiple layers of social justice influence for counselors. Finally, the model is simple and meets the developmental needs of novice counselors. By identifying three tiers of social justice work, Chang and colleagues (2009) crafted an accessible tool to help new and practicing school counselors infuse social justice into their practice. This high level of structure matches the initial developmental levels of new counselors, who typically benefit from high amounts of structure and low amounts of challenge in supervision (Foster & McAdams, 1998).

Method

The research question guiding this study was: What are the experiences of master’s counseling students in individual social justice supervision? We used a social constructivist theoretical framework and presumed that knowledge would be gained about the participants’ experiences based on their social constructs (Hays & Singh, 2012). The ontological perspective reflected realism, or the belief that constructs exist in the world even if they cannot be fully measured (Yin, 2017).

We selected a qualitative case study methodology because it was the most appropriate approach to explore the experiences of a single group of supervisees supervised by the same supervisor in the same semester. In this approach, researchers examine one identified unit bounded by space, time, and persons (Hancock et al., 2021; Hays & Singh, 2012; Yin, 2017). Qualitative case study research allows researchers to deeply explore a single case, such as a group, person, or experience, and gain an in-depth understanding of that identified situation, as well as meaning for the people involved in it (Hancock et al., 2021; Prosek & Gibson, 2021).

In this study, we selected a case study methodology because the study’s participants engaged in the same supervisory experience at the same counseling program in the same semester, thus forming a case to be studied (Hancock et al., 2021). Given the research question, we specifically used a descriptive case study design, which reflected the study goals to describe participants’ experiences in a specific social justice supervision experience. Case study scholars (Hancock et al., 2021; Yin, 2017) have noted that identifying the boundaries of a case is an essential step in the study process. Thus, the boundaries for this study were: master’s-level school counseling students receiving social justice supervision from the same supervisor (persons) at a medium-sized public university on the East Coast (place) over the course of a 14-week semester (time).

Research Team

Our research team for this study consisted of our first and third authors, Clare Merlin-Knoblich and Benjamin Newman, both of whom received training and had experience in qualitative research. Merlin-Knoblich and Newman both identify as White, heterosexual, cisgender, middle-class, and trained counselor educators/supervisors. Merlin-Knoblich is a woman (pronouns: she/her/hers) and former school counselor, who completed master’s and doctoral coursework on social justice counseling and studied social justice supervision in a doctoral program. Newman is a man (pronouns: he/him/his) and clinical mental health/addictions counselor, who completed social justice counseling coursework in a master’s counseling program before completing a doctorate in counselor education and supervision. Our second author, Jenna L. Taylor, was not a part of the research team, but rather was a counseling student unaffiliated with the research participants who assisted in the preparation of the manuscript. Taylor identifies as a White, heterosexual, cisgender, and middle-class woman (pronouns: she/her/hers) with prior experience in research courses and on qualitative research teams. Merlin-Knoblich was familiar with all three participants given her role as the practicum supervisor. Taylor and Newman did not know the study participants beyond Newman’s interactions while recruiting and interviewing them for this study.

Participants and Context

Although some scholars of some qualitative research methodologies call for requisite minimum numbers of participants, in case study research, there is no minimum number of participants sufficient to study (Hays & Singh, 2012). Rather, in case study research, researchers are expected to study the number of participants needed to reflect the phenomenon being studied (Hancock et al., 2021). There were three participants in this study because the supervisory experience that comprised the case studied included three supervisees. Adding additional participants outside of the case would have conflicted with the boundaries of the case and potentially interfered with an understanding of the single, designated case in this study.

All study participants identified as White, heterosexual, cisgender, middle-class, and English-speaking women (pronouns: she/her/hers). Participants were 23, 24, and 26 years old. All the participants were students in the same CACREP-accredited school counseling program at a public liberal arts university on the East Coast of the United States. Prior to the study, the participants completed courses in techniques, group counseling, school counseling, ethics, and theories. While being supervised, participants also completed a practicum experience and coursework in multicultural counseling and career development.

All participants completed practicum at high schools near their university. One high school was urban, one was suburban, and one was rural. During the practicum experience, participants met with Merlin-Knoblich, their supervisor, for face-to-face individual supervision for 1 hour each week. They also submitted weekly journals to Merlin-Knoblich, written either freely or in response to a prompt, depending on their preference. Merlin-Knoblich then provided weekly written feedback to each participant’s journal entry, and, if relevant, the journal content was discussed during face-to-face supervision. Simultaneously, a university faculty member provided weekly face-to-face supervision-of-supervision to Merlin-Knoblich to monitor supervision skills and ensure adherence to the identified supervision model. The faculty member possessed more than 15 years of experience in supervision and was familiar with social justice supervision models.

Merlin-Knoblich applied Chang and colleagues’ (2009) social constructivist social justice supervision model in deliberate ways throughout the supervisees’ 14-week practicum experience. For example, in the initial supervision sessions, Merlin-Knoblich introduced the supervision model and explained how they would collaboratively explore ideas of social justice in counseling related to their practicum experiences. This included defining social justice, discussing supervisees’ previous background knowledge, and exploring their openness to the idea.

Throughout the first 5 weeks of supervision, Merlin-Knoblich used exploratory questions to build participants’ self-awareness (the first tier), particularly around their experiences with privilege and oppression. During the next 5 weeks of supervision, Merlin-Knoblich focused on the second tier, understanding clients’ worldviews. They discussed sociopolitical factors and examined how a client’s worldview impacts their experiences. For example, Merlin-Knoblich discussed how a client’s age, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, family structure, language, immigrant status, gender identity, sexual orientation, and other factors can influence their experiences. Lastly, in the final 4 weeks of supervision, Merlin-Knoblich focused on the third tier of social justice implications at the institutional level. For instance, Merlin-Knoblich initiated discussions about policies at participants’ practicum sites that hindered equity. Merlin-Knoblich also explored the role that participants could take in making resources available to clients, advocating in the community, and using leadership to support social justice. Table 1 summarizes how Merlin-Knoblich implemented Chang and colleagues’ (2009) social justice model.

Table 1

Social Justice Supervision in Practice

Merlin-Knoblich addressed fidelity to the supervision model in two ways. First, in weekly supervision-of-supervision meetings with the faculty advisor, they discussed the supervision model and its use in sessions with participants. The faculty advisor regularly asked about the supervision model and how it manifested in sessions in an attempt to ensure that the model was being implemented recurrently. Secondly, engagement with Newman occurred in regular peer debriefing discussions about the use of the supervision model. Through these discussions, Newman monitored Merlin-Knoblich’s use of the social justice model throughout the 14-week supervisory experience.

Data Collection

We obtained IRB approval prior to initiating data collection. One month after the end of the semester and practicum supervision, Newman approached Merlin-Knoblich’s three supervisees about participation in the study. He explained that participation was an exploration of the supervisees’ experiences in supervision and not an evaluation of the supervisees or the supervisor. Newman also emphasized that participation in the study was confidential, entirely voluntary, and would not affect participants’ evaluations or grades in the practicum course, which ended before the study took place. All supervisees agreed to participate.

Case study research is “grounded in deep and varied sources of information” (Hancock et al., 2021) and thus often incorporates multiple data sources (Prosek & Gibson, 2021). In the present study, we identified two data sources to reflect the need for varied information sources (Hancock et al., 2021). The first data source came from semistructured interviews with participants, a frequent data collection tool in case study research (Hancock et al., 2021). One month after the participants’ practicum experiences ended, Newman conducted and audio-recorded 45-minute individual in-person interviews with each participant using a prescribed interview protocol that explored participants’ experiences in social justice supervision. Newman exercised flexibility and asked follow-up questions as needed (Merriam, 1998).

The interview protocol contained 12 questions identified to gain insights into the case being studied (Hancock et al., 2021). Merlin-Knoblich and Newman designed the interview protocol by drafting questions and reflecting on three influences: (a) the overall research question guiding the study, (b) the social constructivist framework of the study, and (c) Chang and colleagues’ (2009) three-tier supervision model. Questions included “In what ways, if any, has the social justice emphasis in your supervision last semester influenced you as a counselor?” Questions also addressed whether or not the emphasis on social justice at each tier (i.e., self, client, institution) affected participants. Appendix A contains a list of all interview questions.

The second data source was participants’ practicum journals. In addition to interviewing the participants about experiences in supervision, we also asked participants if their practicum journals could be used for the study’s data analysis. The journals served as a valuable form of data to answer the research question, given their informative and non-prescriptive nature. That is to say, although participants knew during the study interviews that the interview data would be used for analysis for the present study, they wrote and submitted their journals before the study was conceptualized. Thus, the journals reflected in-the-moment ideas about participants’ practicum and social justice supervision. Furthermore, this emphasis on participant experiences during the supervisory experience aligned with the methodological emphasis on studying a case in its natural context (Hancock et al., 2021). All participants consented for their 14 practicum journal entries (each 1–2 pages in length) to be analyzed in the study, and they were added to the interview data to be analyzed together. Such convergent analysis of data is typical in case study research (Prosek & Gibson, 2021).

Data Analysis

We followed Yin’s (2017) case study research guidelines throughout the data analysis process. We transcribed all interviews, replaced participants’ names with pseudonyms, and sent participants the transcripts for member checking. Two participants approved their interview transcripts without objection. One participant approved the transcript but chose to share additional ideas about the supervisory experience via a brief email. This email was added to the data. The case study database was then formed with the compiled participants’ journal entries, the additional email, and the interview data (Yin, 2017).

Next, we read each interview transcript and journal entry twice in an attempt to become immersed in the data (Yin, 2017). We then independently open coded transcripts by identifying common words and phrases while maintaining a strong focus on the research question and codes that answered the question (Hancock et al., 2021). We compared initial codes and then collaboratively narrowed codes into cohesive categories representing participants’ experiences. This process generated a list of tentative categories across data sources (Yin, 2017). Throughout these initial processes, we attended to two of Yin’s (2017) four principles of high-quality data analysis: attend to all data and focus on the most significant elements of the case.

We then independently contrasted the tentative categories with the data to verify that they aligned accurately. We discussed the verifications until consensus was met on all categories. Lastly, we classified the categories into three themes and two subthemes found across all participants (Stake, 2005). During these later processes, we were mindful of Yin’s (2017) remaining two principles of high-quality data analysis: consider rival interpretations of data and use previous expertise when interpreting the case. Accordingly, we reflected on possible contrary explanations of the themes and considered the findings in light of previous literature on the topic.

Trustworthiness

We addressed trustworthiness in three ways in this study. First, before data collection, we engaged in reflexivity through acknowledging personal biases and assumptions with one another (Hays & Singh, 2012; Yin, 2017). For example, Merlin-Knoblich acknowledged that her lived experience supervising the participants might impact the interpretation of data during analysis and noted that these perceptions could potentially serve as biases during the study. Merlin-Knoblich perceived that the supervisees grew in their understanding of social justice, but also acknowledged doubt over whether the social justice supervision model impacted participants’ advocacy skills. She also noted her role as a supervisor evaluating the three participants prior to the study taking place. These power dynamics may have influenced her interpretations in the analysis process. Newman shared that his lack of familiarity with social justice supervision might impact perceptions and biases to question whether or not supervisees grew in their understanding of social justice. We agreed to challenge one another’s potential biases during data analysis in an attempt to prevent one another’s experiences from interfering with interpretations of the findings.

In addition, we acknowledged that our identities as White, English-speaking, educated, heterosexual, cisgender, middle-class researchers studying social justice inevitably was informing personal perceptions of the supervisees’ experiences. These privileged identities were likely blinding us to experiences with oppression that participants and their clients encountered and that we are not burdened with facing. Throughout the study, we discussed the complexity of studying social justice in light of such privileged identities. We spoke further about our identities and potential biases when interpreting the data.

Second, investigator triangulation was addressed by collaboratively analyzing the study’s data (Hays & Singh, 2012). Because data included both interview transcripts and journals, we confirmed that study findings were reflected in both data sources, rather than just one information source (Hancock et al., 2021). This process helped prevent real or potential biases from informing the analysis without constraint. We also were mindful of saturation of themes while comparing data across participants and sources during the analysis process. Lastly, an audit trail was created to further address credibility. The study recruitment, data collection, and data analysis were documented so that the research can be replicated (Hays & Singh, 2012; Roulston, 2010).

Findings

In case study research, researchers use key quotes and descriptions from participants to illuminate the case studied (Hancock et al., 2021). As such, we next describe the themes and subthemes identified in study data using participants’ journal and interview quotes to illustrate the findings. Three overarching themes were identified in the data: 1) intersection of supervision experiences and external factors, 2) feelings about social justice, and 3) personal and professional growth. Two subthemes, 3a) increased understanding of privilege and 3b) increased understanding of clients, further expand the third theme.

Intersection of Supervision Experiences and External Factors

One theme evident across the data was that participants’ experiences in social justice supervision did not occur in isolation from other experiences they encountered as counseling students. Coursework, overall program emphasis, and previous work experiences were external factors that created a compound influence on participants’ counselor development and intersected with their experiences of growth in supervision. Thus, external factors influenced participants’ understanding of and openness to a social justice framework. For example, concurrent with their practicum and supervision experiences, participants completed the course Theory and Practice of Multicultural Counseling. While discussing their experiences in supervision, all participants referenced this course. For example, Casey explained that exposure to social justice in the multicultural counseling course while discussing the topic in supervision made her more open and eager to learning about social justice overall.

Participants’ experiences prior to the counseling program also appeared to intersect with and influence their experiences in social justice supervision. Kallie, for instance, previously worked with African American and Latin American adolescents as a camp counselor at an urban Boys and Girls Club. She explained that social justice captured the essence of viewpoints formed in these experiences, saying, “I really like social justice because it kind of is like the title for the way I was looking at things already.” Casey grew up in California and reported that growing up on the West Coast also exposed her to a mindset parallel to social justice. Esther described that though she was not previously exposed to the term “social justice,” studying U.S., women’s, and African American history in college influenced her pursuit of a counseling career. This influence is evident in Esther’s third journal entry, in which she described noticing issues of power and oppression:

My own attention to an “arbitrarily awarded power” and personal questioning as to what to do with this consciousness has been at the forefront of my mind over the past two years. Ultimately this self-exploration led me to school counseling as a vehicle to advocate and raise consciousness in potentially disenfranchised groups.

This quote highlights how Esther’s previous studies in college may have primed her for the content she was exposed to in social justice supervision.

Feelings About Social Justice

The second theme was a change in participants’ feelings toward social justice over the course of the semester. Two of the participants expressed that their feelings toward social justice changed from intimidation and fear to comfort and enthusiasm. Initially, Casey explained that social justice supervision created feelings of intimidation. Casey felt fear that the supervisor would instruct her to be an advocate at the practicum site, and that in doing so, Casey would upset others. However, Casey reported that she realized during supervision that social justice advocacy does not necessarily look one specific way. Casey said, “I think a lot of that intimidation went away as I realized that I could have my own style integrated into social justice.” Kallie expressed a similar pattern of emotions, particularly regarding examining clients from a social justice perspective. When asked to explore clients through this lens in supervision, an initial uncomfortable feeling emerged, but over the course of practicum, Kallie reported an attitude change. In the sixth journal entry, Kallie explained that she was focusing on examining all clients through a social justice lens, and “found it to be significantly easier this week than last week.”

Esther also shared evidence of changed emotions during social justice supervision. Initially, Esther reported feeling excited, but later, she was confused as to how counselors could use social justice practically. Despite this confusion, Esther shared that she gained new awareness that social justice advocacy is not only found in individual situations with clients, but also in an overall mindset:

Something I will take from it [supervision] . . . is you incorporate that sort of thinking into your overall [approach]. You don’t necessarily wait for a specific event to happen, but once you know the culture of a place, you have lessons geared towards whatever the problem is there.

Despite these mixed feelings, Esther’s experience aligns with Casey’s and Kallie’s, as all reported experiencing a change in emotions toward social justice over the course of supervision.

Personal and Professional Growth

Participants also demonstrated changes in professional and personal growth throughout the supervision experiences, the third theme identified. In early journal entries, they reported nervousness, doubt, and insecurity regarding their counseling skills and knowledge. Over time, the tone shifted to increased comfort and confidence. This improvement appeared not only related to overall counseling abilities, but specifically to participants’ understanding of social justice in counseling. For example, in Esther’s second journal entry, she noted the influence that social justice supervision had on the ability to recognize oppression and bring awareness to it at practicum. Esther wrote, “Just having this concept be explicitly laid out in our plan has already caused me to be more attentive to such issues.”

Similarly, professional growth was evident in Kallie’s journal entries over time. In the fourth journal entry, Kallie described discomfort and nervousness when reflecting on clients’ sociopolitical contexts. However, in the ninth journal entry, Kallie described an experience in which she adapted her counseling to be more sensitive to the client’s multicultural background. Casey also highlighted growth with an anecdote about a small group she led. Casey explained that the group was for high-achieving, low-income juniors intending to go to college:

In the very beginning, I remember thinking—this sounds terrible now, but—“It’s kind of unfair to the other students that these kids get special privileges in that they get to meet with us and walk through the college planning process.” ’Cause I was thinking, “Wow, even kids who are high-achieving but are middle-class or upper-class, they could use this information, also. And it’s not really fair that just ’cause they’re lower class, they get their hand held during this.” But, throughout the semester, realizing that that’s not necessarily a bad thing for an institution to give another one a little extra help because they’re gonna have a deficit of help somewhere else in their life, and it really is fair. It’s more fair to give them more help ’cause they likely aren’t going to be getting it at home. . . . So, by having that group, it actually is making a greater degree of equity . . . through supervision and through processing all of that, [I learned] it was actually evening the board out more.

Participants also expressed that their professional growth in social justice competencies was intertwined with personal growth. Casey reported that supervision increased her comfort when talking about social justice issues and led to the reevaluation of personal opinions. Similarly, Kallie summarized:

I am very thankful that I had that social justice–infused model because it changed the way I think about people. . . . It kinda opened my eyes in a way I had not anticipated practicum opening my eyes. I didn’t expect that—social justice. I didn’t realize how big of an impact it would actually have.

Increased Understanding of Privilege

Participants reported that understanding their privilege was one area of growth. During practicum, participants considered their areas of privilege and how these aligned or contrasted with those of clients. For example, in Esther’s third journal entry, she noted that interactions with clients made her more aware of personal privileges, which led her to create a list regarding gender identity, socioeconomic background, and sexual orientation. Casey and Kallie further described initially feeling resistant to the idea of White privilege. Casey explained:

I was a little resistant to the idea of White privilege originally, which I’ve since learned is a normal reaction. ’Cause I’ve kind of had the thought of “No! It’s America! All of us pull ourselves up by our bootstraps and everyone has the same opportunity,” which just isn’t the case. And so that definitely had a huge influence on me—realizing that I have huge privileges and powers that I did not, maybe didn’t want to, recognize before.

After initial resistance, participants reported that they transitioned from feeling shame about White privilege to an increased understanding and excitement to use privilege to create change.

Increased Understanding of Clients

Lastly, participants also reported specific growth in their understanding of the clients whom they counseled. Participants believed they were better able to understand clients’ backgrounds and experiences because of social justice supervision. Kallie described how reflecting on clients’ sociopolitical contexts helped her better understand clients. She noted that the practice became a habit, saying, “It just kinda invaded the way I look at different people and see their backgrounds.” Casey also described an increased understanding of clients by sharing an example of a client who was highly intelligent, low-income, and Mexican American. Casey learned that the client intended to go to trade school to become a mechanic and was not previously exposed to other postsecondary education options like college. Casey described this realization as “a big moment” and said, “My interaction with him, for sure, was influenced by recognizing that there was social injustice there.”

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore counseling students’ experiences in social justice supervision. Findings indicated that participants had meaningful experiences in social justice supervision that impacted them as future counselors. Topics of privilege, oppression, clients’ sociopolitical contexts, and advocacy were reportedly prominent in the participants’ supervision and influenced their experiences.

Despite many calls for social justice supervision in the counseling profession (Baggerly, 2006; Ceballos et al., 2012; Chang et al., 2009; Collins et al., 2015; Glosoff & Durham, 2010; O’Connor, 2005), this is the first known study about supervisees’ experiences with social justice supervision. It represents a new line of inquiry to understand what social justice supervision may be like for supervisees. Findings indicate that participants wrestled with understanding social justice and viewed it as a complex topic. They also suggest that participants found value in making sense of social justice and using it as a tool to better support clients individually and systemically. Similar to research on multicultural supervision, participants indicated that receiving social justice supervision was a positive experience and impacted personal and professional growth (Ancis & Ladany, 2001; Ancis & Marshall, 2010; Chopra, 2013; Inman, 2006; Ladany et al., 2005).

Notably, findings align with some, though not all, of Chang and colleagues’ (2009) delineated tiers in the social justice supervision model. Some of the themes reflect the first tier, self-awareness. For example, participants’ feelings about social justice (Theme 2) and increased understanding of privilege (Theme 3a) highlight how the supervisory experience enhanced their self-awareness as counselors. As their feelings changed and knowledge of privilege grew, their self-awareness improved, a critical task in becoming a social justice–minded counselor (Chang et al., 2009; Dollarhide et al., 2021; Fickling et al., 2019; Glosoff & Durham, 2010). Participants’ increased understanding of clients (Theme 3b) reflects the second tier in Chang and colleagues’ (2009) model, client services. In demonstrating an enhanced understanding of clients and their world experiences, the participants reported thinking beyond themselves and into how power, privilege, and oppression affected those they counseled.

The final tier of the social justice supervision model, community collaboration, was not evident in participant data about their experiences. Despite the supervisor’s intent to address this tier through analyses of school and district policies, as well as community advocacy opportunities, themes about this topic did not manifest in the data. This theme’s absence may suggest that the supervisor’s efforts to address the third tier were not strong enough to impact participants. Alternatively, the absence may suggest that participants were not developmentally prepared to make sense of social justice at a systemic, community level. Instead, their development matched best with social justice ideas at the self and client levels.

Participant findings did align with previous research about supervision. For example, Collins and colleagues (2015) studied master’s-level counseling students and found that their lack of experience in social justice supervision led them to feel unprepared to meet the needs of diverse clients. In this study, the presence of social justice supervision helped participants feel more prepared to support clients, as evidenced in the subtheme of increased understanding of clients. Furthermore, this study reflects similar findings from multicultural supervision research. We found that multicultural supervision was associated with positive outcomes of being prepared to work with diverse clients and engaging in effective supervision (Chopra, 2013; Inman, 2006; Ladany et al., 2005). This pattern is reflected in the current study, as participants reported positive experiences in social justice supervision. Ancis and Ladany (2001) and Ancis and Marshall (2010) found that incorporating multicultural considerations into supervision increases supervisees’ self-awareness and encourages them to engage clients in multicultural discussions. These same results were evident in the present study, with participants reporting personal and professional growth, such as stronger awareness of White privilege and greater willingness to examine clients’ sociopolitical contexts. Findings also reflect general research on supervision, which indicates that supervisees typically experience personal and professional growth in the process (Association for Counselor Education and Supervision, 2011; Watkins et al., 2015; Young et al., 2011).

Furthermore, study findings also align with assertions from supervision scholars regarding the value of social justice supervision. They support Chang and colleagues’ (2009) claim that social justice supervision can increase counselor self-awareness and build an understanding of oppression. Additionally, the findings also reflect Glosoff and Durham’s (2010) assertion that social justice in supervision helps supervisees gain awareness of power differentials. Finally, Ceballos and colleagues (2012) posited that social justice supervision will help counselors develop empathy for clients as counselors conceptualize clients in a systemic perspective. The participants’ enhanced understanding of White privilege and their clients’ contexts supports each of these ideas. Though findings are not generalizable, they appear to confirm scholars’ ideas about social justice supervision and suggest that the approach can be a positive, beneficial experience for counselors-in-training.

Limitations

Study findings ought to be considered in light of the study’s limitations. First, although case study research focuses on a single identified case by definition and is not designed for generalization (Hays & Singh, 2012), the case in this study consisted of a demographically homogenous population of only three participants lacking racial, gender, and age diversity. This lack of diversity influenced participants’ experiences and study findings. Second, although the supervisor in this study did not conduct the semistructured interviews with participants in an attempt to prevent bias, participants were aware that Merlin-Knoblich was collaborating on the study, and this knowledge may have influenced their reported experiences. Merlin-Knoblich and Newman also began the study with acknowledged biases toward and against social justice supervision, and although they engaged in reflexivity and dialogue to prevent these biases from interfering with data analysis, there is no way to verify that this positionality did not influence the interpretation of findings. Lastly, our privileged identities served as a potential limitation while studying a topic like social justice supervision. Our racial, educational, class, language, and sexual identity privileges continually blind us to the experiences of oppression that others, including supervisees and clients, face. Seeking to know these perspectives better can increase our understanding of the implications of social injustices in society.

Implications for Counselor Educators and Supervisors

The positive participant experiences illuminated through this study suggest that supervision based on this model may yield positive experiences for counselors-in-training, such as supporting students in developing self-awareness, understanding of clients’ sociopolitical contexts, and advocacy skills (Chang et al., 2009). Although the supervisor in this study used social justice supervision in individual sessions with participants, counselor educators may choose to apply social justice supervision models to group or triadic supervision. Counseling supervisors in agency, private practice, and school settings may also want to consider using social justice supervision to support counselors and subsequently clients (Baggerly, 2006; Ceballos et al., 2012; O’Connor, 2005). Furthermore, counselor educators teaching doctoral students may want to incorporate social justice supervision models into introductory supervision courses. Including these models into course content may in itself increase student interest in social justice (Swartz et al., 2018).

Regardless of the setting in which supervisors implement social justice supervision, the findings suggest practical implications that supervisors can consider. First, supervisors appear to benefit from considering social justice supervision models in their work (Chang et al., 2009; Dollarhide et al., 2021; Gentile et al., 2009). The findings in this study, plus previous research indicating positive outcomes for multicultural supervision (Chopra, 2013; Inman, 2006; Ladany et al., 2005), suggest that social justice supervision may potentially benefit counseling. Second, supervisors using social justice supervision may encounter supervisee confusion, discomfort, and/or enthusiasm when introduced to social justice supervision. These feelings also may change over the course of the supervisory relationship when learning about social justice. Third, supervisors ought to be mindful of all three tiers of Chang and colleagues’ (2009) social justice supervision model and a supervisee’s developmental match with each tier. As seen in this study, supervisees may be best matched for the first and second tiers of the model (self-awareness and client services), but not the third tier (community collaboration). Supervisors would benefit from assessing a supervisee’s potential for understanding community collaboration before deciding to infuse its focus in supervision.

More research is needed to understand social justice supervision. A variety of future studies, including different models, methods, and settings, would benefit the counseling profession. For example, a study implementing the social justice supervision model proposed by Dollarhide and colleagues (2021) can add to the needed research in this field. Additional qualitative studies with diverse supervisees in different counseling settings would be helpful in understanding if the experiences participants reported encountering in this study are common in social justice supervision. Quantitative studies on social justice supervision interventions would also add to the profession’s knowledge on the value of social justice supervision. Lastly, studies on supervisees’ experiences in social justice supervision compared to other models would highlight benefits and drawbacks of multiple supervision models (Baggerly, 2006; Chang et al., 2009; Glosoff & Durham, 2010).

Conclusion

In this article, we explored master’s-level counseling students’ experiences in social justice supervision via a qualitative case study. Through this exploration, we identified three themes reflecting participants’ experiences in social justice supervision: intersection of supervision experiences and external factors, feelings about social justice, and personal and professional growth, as well as two subthemes: increased understanding of privilege and increased understanding of clients. Findings suggest that social justice supervision may be a beneficial practice for supervisors and counselor educators to consider integrating in their work (Chang et al., 2009; Dollarhide et al., 2021; Gentile et al., 2009; Pester et al., 2020). Further research across contexts and with a range of methodologies is needed to better understand social justice supervision in practice.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

American Counseling Association. (2014). ACA code of ethics. https://www.counseling.org/resources/aca-code-of-ethics.pdf

Ancis, J. R., & Ladany, N. (2001). A multicultural framework for counselor supervision. In L. J. Bradley & N. Ladany (Eds.), Counselor supervision: Principles, process, and practice (3rd ed., pp. 63–90). Brunner-Routledge.

Ancis, J. R., & Marshall, D. S. (2010). Using a multicultural framework to assess supervisees’ perceptions of culturally competent supervision. Journal of Counseling & Development, 88(3), 277–284.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00023.x

Association for Counselor Education and Supervision. (2011). Best practices in clinical supervision. https://acesonline.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/ACES-Best-Practices-in-Clinical-Supervision-2011.pdf

Baggerly, J. (2006). Service learning with children affected by poverty: Facilitating multicultural competence in counseling education students. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 34(4), 244–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1912.2006.tb00043.x

Ballou, M., Matsumoto, A., & Wagner, M. (2002). Toward a feminist ecological theory of human nature: Theory building in response to real-world dynamics. In M. Ballou & L. S. Brown (Eds.), Rethinking mental health and disorder: Feminist perspectives (pp. 99–141). Guilford.

Ceballos, P. L., Parikh, S., & Post, P. B. (2012). Examining social justice attitudes among play therapists: Implications for multicultural supervision and training. International Journal of Play Therapy, 21(4), 232–243. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028540

Chang, C. Y., Hays, D. G., & Milliken, T. F. (2009). Addressing social justice issues in supervision: A call for client and professional advocacy. The Clinical Supervisor, 28(1), 20–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/07325220902855144

Chopra, T. (2013). All supervision is multicultural: A review of literature on the need for multicultural supervision in counseling. Psychological Studies, 58, 335–338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-013-0206-x

Collins, S., Arthur, N., Brown, C., & Kennedy, B. (2015). Student perspectives: Graduate education facilitation of multicultural counseling and social justice competency. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 9(2), 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1037/tep0000070

Dinsmore, J. A., Chapman, A., & McCollum, V. J. C. (2002). Client advocacy and social justice: Strategies for developing trainee competence. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the American Counseling Association, Washington, DC.

Dollarhide, C. T., Hale, S. C., & Stone-Sabali, S. (2021). A new model for social justice supervision. Journal of Counseling & Development, 99(1), 104–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12358

Dollarhide, C. T., Mayes, R. D., Dogan, S., Aras, Y., Edwards, K., Oehrtman, J. P., & Clevenger, A. (2018). Social justice and resilience for African American male counselor educators: A phenomenological study. Counselor Education and Supervision, 57(1), 2–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12090

Fickling, M. J., Tangen, J. L., Graden, M. W., & Grays, D. (2019). Multicultural and social justice competence in clinical supervision. Counselor Education and Supervision, 58(4), 309–316. https://doi.org/10.1002.ceas.12159

Foster, V. A., & McAdams, C. R., III. (1998). Supervising the child care counselor: A cognitive developmental model. Child and Youth Care Forum, 27(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02589525

Garcia, M., Kosutic, I., McDowell, T., & Anderson, S. A. (2009). Raising critical consciousness in family therapy supervision. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 21(1), 18–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952830802683673

Gentile, L., Ballou, M., Roffman, E., & Ritchie, J. (2009). Supervision for social change: A feminist ecological perspective. Women & Therapy, 33(1–2), 140–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703140903404929

Glosoff, H. L., & Durham, J. C. (2010). Using supervision to prepare social justice counseling advocates. Counselor Education and Supervision, 50(2), 116–129. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2010.tb00113.x

Greene, J. H., & Flasch, P. S. (2019). Integrating intersectionality into clinical supervision: A developmental model addressing broader definitions of multicultural competence. The Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 12(4). https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/jcps/vol12/iss4/14

Hancock, D. R., Algozzine, B., & Lim, J. H. (2021). Doing case study research: A practical guide for beginning researchers (4th ed.). Teachers College Press.

Hays, D. G., & Singh, A. A. (2012). Qualitative inquiry in clinical and educational settings. Guilford.

Inman, A. G. (2006). Supervisor multicultural competence and its relation to supervisory process and outcome. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 32(1), 73–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2006.tb01589.x

Kiselica, M. S., & Robinson, M. (2001). Bringing advocacy counseling to life: The history, issues, and human dramas of social justice work in counseling. Journal of Counseling & Development, 79(4), 387–397.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2001.tb01985.x

Ladany, N., Friedlander, M. L., & Nelson, M. L. (2005). Critical events in psychotherapy supervision: An interpersonal approach. American Psychological Association.

Lee, C. C. (2007). Counseling for social justice (2nd ed.). American Counseling Association.

Lee, E., & Kealy, D. (2018). Developing a working model of cross-cultural supervision: A competence- and alliance-based framework. Clinical Social Work Journal, 46, 310–320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-018-0683-4

Lewis, J. A., Arnold, M. S., House, R., & Toporek, R. L. (2003). Advocacy competencies. www.counseling.org/resources/competencies/advocacy_competencies.pdf

Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. Jossey-Bass.

O’Connor, K. (2005). Assessing diversity issues in play therapy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 36(5), 566–573. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.36.5.566

Pester, D. A., Lenz, A. S., & Watson, J. C. (2020). The development and evaluation of the Intersectional Privilege Screening Inventory for use with counselors-in-training. Counselor Education and Supervision, 59(2), 112–128. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12170

Peters, H. C. (2017). Multicultural complexity: An intersectional lens for clinical supervision. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 39, 176–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-017-9290-2

Prosek, E. A., & Gibson, D. M. (2021). Promoting rigorous research by examining lived experiences: A review of four qualitative traditions. Journal of Counseling & Development, 99(2), 167–177. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12364

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar-McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2015). Multicultural and social justice counseling competencies. www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/competencies/multicultural-and-social-justice-counseling-competencies.pdf

Roffman, E. (2002). Just supervision. Multicultural Perspectives on Social Justice and Clinical Supervision Conference, Cambridge, MA, United States.

Roulston, K. (2010). Reflective interviewing: A guide to theory and practice. SAGE.

Stake, R. E. (2005). Qualitative case studies. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 433–466). SAGE.

Swartz, M. R., Limberg, D., & Gold, J. (2018). How exemplar counselor advocates develop social justice interest: A qualitative investigation. Counselor Education and Supervision, 57(1), 18–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12091

Toporek, R. L., & Daniels, J. (2018). ACA advocacy competencies. https://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source

/competencies/aca-advocacy-competencies-updated-may-2020.pdf?sfvrsn=f410212c_4

Watkins, C. E., Jr., Budge, S. L., & Callahan, J. L. (2015). Common and specific factors converging in psychotherapy supervision: A supervisory extrapolation of the Wampold/Budge Psychotherapy Relationship Model. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 25(3), 214–235. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0039561

Yin, R. K. (2017). Case study research and applications: Designs and methods (6th ed.). SAGE.

Young, T. L., Lambie, G. W., Hutchinson, T., & Thurston-Dyer, J. (2011). The integration of reflectivity in developmental supervision: Implications for clinical supervisors. The Clinical Supervisor, 30(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2011.532019

Appendix A

Semistructured Interview Questions

- What brought you to this counseling program?

- Overall, how would you describe your practicum experience last semester?

- Where did you complete your practicum?

- How would you describe the population you worked with at your practicum?

- What previous experience, if any, did you have with social justice prior to individual practicum supervision?

- During individual practicum supervision on campus last semester, what were some of your initial thoughts and feelings about a social justice–infused supervision model?

- In what ways, if any, did those thoughts and feelings about social justice change throughout your

supervision experience?

These next three questions address three areas of social justice that were incorporated into your individual practicum supervision model: self, students (clients), and institution (school or school districts).

6. Do you think that the emphasis on social justice related to self (i.e., your power, privileges, and experience with oppression) in individual practicum supervision on campus had any influence on you?

-

- If yes, what influence did this emphasis have on you?

- If no, why do you think that’s the case?

7. Do you think that the emphasis on social justice related to others (i.e., the sociopolitical context of students, staff, etc.) in individual practicum supervision on campus had any influence on you?

-

- If yes, what influence did this emphasis have on you?

- If no, why do you think that’s the case?

8. Do you think that the emphasis on social justice related to institution (i.e., your practicum site, school district) in individual practicum supervision on campus had any influence on you?

-

- If yes, what influence did this emphasis have on you?

- If no, why do you think that’s the case?

- In what ways, if any, has the social justice emphasis in your individual practicum supervision influenced you as a counselor?

- In what ways, if any, has the social justice emphasis in your individual practicum supervision influenced your development as a person?

- How would you define social justice?

- Is there anything else you would like to add regarding your experience in a social justice–infused model of supervision last semester?

- Is there anything else you’d like to share?

Clare Merlin-Knoblich, PhD, NCC, is an associate professor at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. Jenna L. Taylor, MA, NCC, LPC-A, is a doctoral student at the University of North Texas. Benjamin Newman, PhD, MAC, ACS, LPC, CSAC, CSOTP, is a professional counselor at Artisan Counseling in Newport News, VA. Correspondence may be addressed to Clare Merlin-Knoblich, 9201 University City Blvd., Charlotte, NC 28211, cmerlin1@uncc.edu.

Nov 9, 2021 | Volume 11 - Issue 4

Stacey Diane Arañez Litam, Christian D. Chan

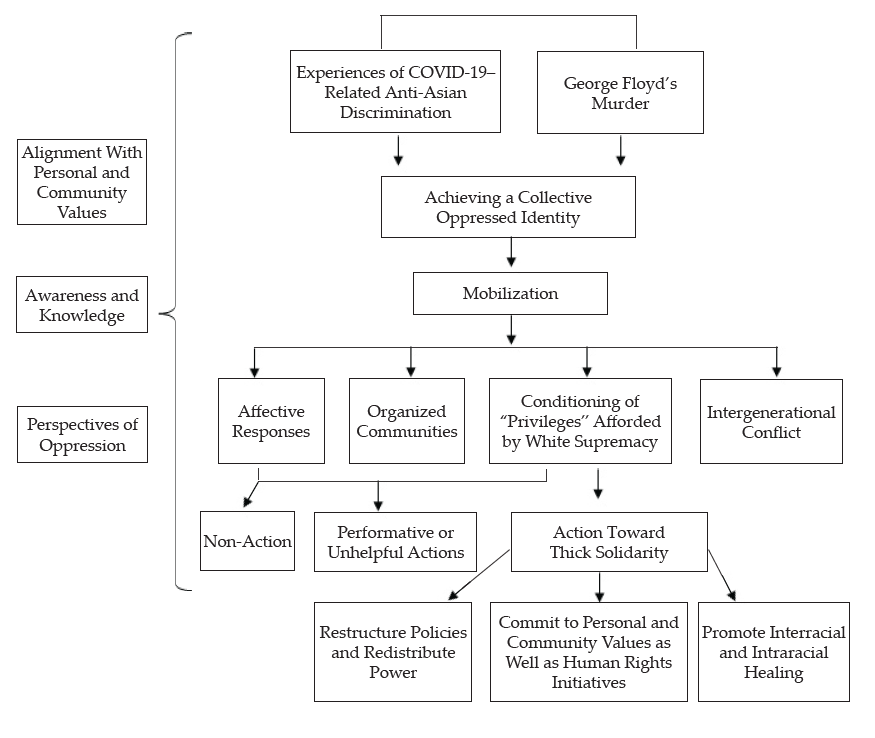

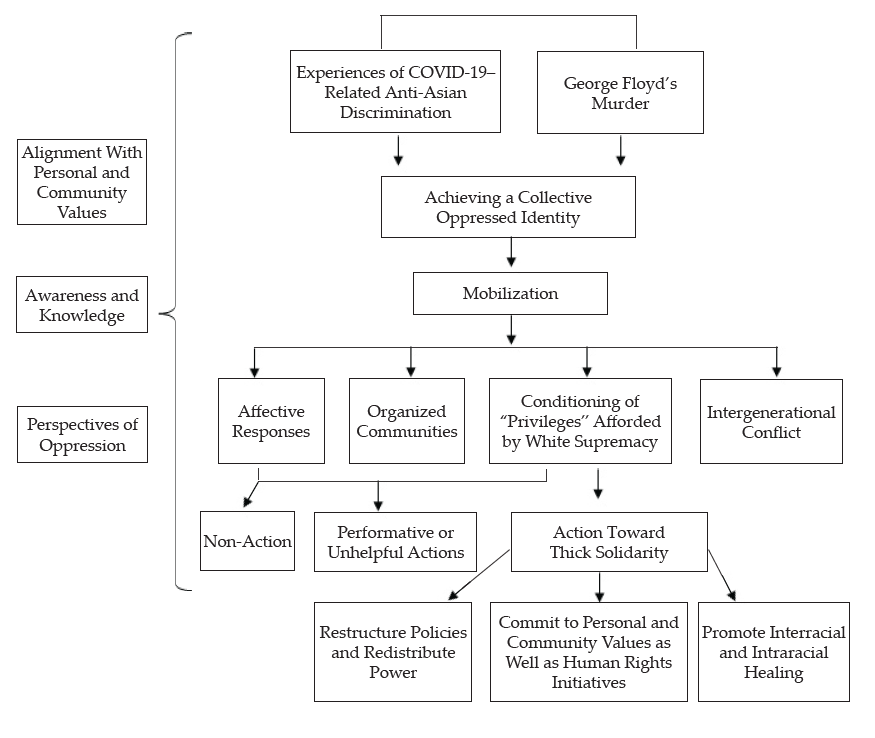

A grounded theory study was employed to identify the conditions contributing to the core phenomenon of Asian American activists (N = 25) mobilizing toward thick solidarity with the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement in 2020. The findings indicate achieving a collective oppressed identity was necessary to mobilize in thick solidarity with the BLM movement and occurred because of causal conditions: (a) experiences of COVID-19–related anti-Asian discrimination, and (b) George Floyd’s murder. Non-action, performative or unhelpful action, and action toward thick solidarity were influenced by contextual factors: (a) alignment with personal and community values, (b) awareness and knowledge, and (c) perspectives of oppression. Mobilization was also influenced by intervening factors, which included affective responses, intergenerational conflict, conditioning of “privileges” afforded by White supremacy, and the presence of organized communities. Mental health professionals and social justice advocates can apply these findings to promote engagement in the community organizing efforts of Asian American and Pacific Islander communities with the BLM movement, denounce anti-Blackness, and uphold a culpability toward supporting the Black community.

Keywords: Asian American, solidarity, social justice, Black Lives Matter, grounded theory

Trayvon Martin’s death in 2012 reignited conversations about the underlying sentiments of White supremacy that remain deeply entrenched in American society (Khan-Cullors & Bandele, 2017; Taylor, 2016). Shortly thereafter, the #BlackLivesMatter (BLM) movement was launched to address acts of police brutality on Black and Brown people and challenge the systemic oppression within the justice system (Lebron, 2017). Following the murder of George Floyd in 2020, the role of silence in perpetuating complicity resurfaced, and the familiar narratives and gut-wrenching images of non-Black police officers harming Black bodies once again found a place in the limelight (Chang, 2020; Elias et al., 2021). However, this time there was something noticeably different; one of the non-Black officers was Asian American.

Tou Thao’s role in sanctioning George Floyd’s murder illuminated the complex history of anti-Blackness within Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) communities; created momentum for conversations about race, discrimination, and oppression; and echoed earlier support for the BLM movement among AAPIs (J. Ho, 2021; Merseth, 2018; Tran et al., 2018). These discussions may have been traditionally avoided, given the narrative invoked by racial and colonial notions that diminishes critical consciousness about racial histories and relations in AAPI communities (Chang, 2020; David et al., 2019). Because of the structural conditions of White supremacy and colonialism, AAPI communities have been forced to adopt Whiteness as a pathway to success, minimize salient cultural values, and trivialize manifestations of anti-Blackness (J. Ho, 2021; Poon et al., 2016). Erasing critical consciousness among AAPI communities has served as an insidious attempt to maintain a racial hierarchy that neither supports AAPI visibility nor eradicates racial tensions (Chou & Feagin, 2016; David et al., 2019). The invisibility of AAPI history absolves the United States from long-standing histories of anti-Asian racial violence (Li & Nicholson, 2021) and endorses complacency of White supremacy (Museus, 2021; Poon et al., 2019). Although this contention exists, a greater number of AAPI voices have begun to mobilize in solidarity with the BLM movement and the Black community in recent years (Anand & Hsu, 2020; Lee et al., 2020; Merseth, 2018; Tran et al., 2018).

Despite a complex racialized history of White supremacists weaponizing communities of color against each other (Nicholson et al., 2020; Poon et al., 2016), AAPI individuals have a long-standing history of pursuing thick solidarity and activism with the Black community and supporting Black civil rights (J. Ho, 2021). These racial coalitions have been evidenced through the Third World Liberation Front Strikes and the tireless efforts of activists like Grace Lee Boggs, Yuri Kochiyama, and Richard Aoki (W. Liu, 2018; Sharma, 2018). Thick solidarity is achieved when racial differences are acknowledged while emphasizing the specificity, irreducibility, and incommensurability of racialized experiences (W. Liu, 2018). Although understanding the factors that influence AAPIs to mobilize with the Black community represents a critical step toward thick solidarity (Tran et al., 2018), previous studies investigating the phenomenon have been limited to quantitative methods (Merseth, 2018; Yoo et al., 2021) or focused solely on Southeast Asian American populations (Lee et al., 2020).

The following sections outline the histories of racialized oppression faced by Asian American and Black communities and provide a brief overview of the extant research linking Asian American solidarity with the BLM movement. A grounded theory that identifies the emergent process that contributed to Asian American activists mobilizing toward thick solidarity with the BLM movement in 2020 is additionally presented.

The Racialized Experiences of Asian Americans and Black Communities in America

Prior to engaging in a grounded theory, researchers must build upon preexisting processes, theories, and perspectives documented in extant research (Charmaz, 2017). Thus, one cannot explore the processes that contributed to Asian American activists mobilizing toward thick solidarity with the BLM movement in 2020 without first addressing the nuanced and racialized experiences of AAPI and Black communities in America. Tran et al. (2018) asserted that navigating an oppressive system embedded in White supremacy has forced communities of color to make historical adaptations that leave AAPI voices out of the BLM movement. The following section provides a brief description of the complexity in which AAPI and Black identities are juxtaposed and elaborates on the model minority myth, racial triangulation, and historical anti-Blackness in AAPI communities as processes that may complicate the process of achieving thick solidarity.

Racial Triangulation

According to Kim (1999), racial triangulation theory refers to a “field of racial positions” (p. 106) that was proposed to extend the conceptualization of racial discourse beyond the Black and White narrative. The field of racial positions is mapped onto two dimensions. The superior/inferior axis represents the process of relative valorization, whereby Whites valorize Asian Americans relative to Black Americans in ways that maintain White privilege and White supremacy (Kim, 1999). The second dimension, an insider/foreigner axis, refers to the process of civic ostracism, in which Whites position Asian Americans as foreign, unassimilable, and outsiders (Kim, 1999; Xu & Lee, 2013). Although Asian Americans may be afforded social and economic benefits due to their proximity to Whiteness, this social location functions as an incomplete portrayal that conceals inequities, treats Asian Americans as perpetual foreigners, and maintains the status of White supremacy over communities of color (Bonilla-Silva, 2004; Nicholson et al., 2020). As a result, members of Asian American communities may be racialized to be White-adjacent and create an illusion of success with a conditional set of privileges (Kim, 1999; Museus, 2021).

One example of racial triangulation is the model minority myth, which essentializes Asian Americans by portraying them as a monolithic group with universal educational and occupational success (Chou & Feagin, 2016; Yi et al., 2020). According to Poon et al. (2016), scholars must acknowledge the model minority myth’s history to challenge processes of racial triangulation and deficit thinking. The model minority myth creates barriers to social justice efforts and racial coalitions by pitting communities of color against one another (Chang, 2020), invalidating experiences of systemic oppression and discrimination (Nicholson et al., 2020; Pendakur & Pendakur, 2016), and maintaining “a global system of racial hierarchies and White supremacy” (Poon et al., 2016, p. 6). When contextualizing the model minority myth through the lens of critical race theory, Asian Americans may be conceptualized as a “middleman minority” (Poon et al., 2016, p. 5). Originally coined by Blalock (1967) and later expanded upon by Bonacich (1973), middleman minorities are foreigners who buffer the power struggles between two major groups in a host society. Similar to other historical middleman minority groups, the minority model myth exploits Asian Americans by granting economic privileges while denying political or social power (Poon et al., 2016). As a more egregious consequence, the model minority myth can lead communities of color to harbor feelings of resentment toward Asian American communities, especially Asian immigrants who may feel pressured to prove their loyalty to American values (J. Ho, 2021) and embrace the submissive, hardworking qualities espoused by the model minority myth (Poon et al., 2019).

The complex relationship between AAPI and Black communities becomes even more complex as communities of color, including Black Americans, continue to define the boundaries of inclusion about “who belongs in communities of Color” (Tran et al., 2018, p. 78). As a result, Asian Americans are rarely included in race dialogues; may not be identified as “of color” by other groups; and are forced to navigate their weaponized, conditional identities as racialized in some spaces and White-adjacent in others (C. D. Chan & Litam, 2021; Litam & Chan, 2021; Museus, 2021; Poon et al., 2016).

Understanding Anti-Blackness in Asian American Communities

The denigration of Black identities and the desire to be viewed as distinct from Black Americans are evidenced across the histories of several Asian American ethnic subgroups. For example, in the mid-20th century, access to U.S. citizenship was limited to free White persons and persons of African descent (Pavlenko, 2002). At the time, the system was not set up to accommodate Asian Americans or other racialized groups, as evidenced by the landmark cases of Takao Ozawa and Bhagat Singh Thind (Chou & Feagin, 2016; Haney López, 2006). After living in the United States for over 20 years and articulating his relationship to White racial groups because of his light skin, Takao Ozawa, a Japanese man, was judged to be a race other than those able to obtain citizenship and deemed ineligible for naturalization (S. Chan, 1991; Yamashita & Park, 1985). Bhagat Singh Thind, an Asian Indian man, attempted to align specifically with the use of “Caucasian” and White racial ideologies, but was also denied citizenship by the U.S. Supreme Court (Haney López, 2006). Following the United States v. Bagat Singh Thind ruling, nearly 50% of Asian Indian Americans had their U.S. citizenship revoked (Haney López, 2006). Despite attempts to prove their loyalty to Whiteness, both cases reified how Asian Americans are placed in a vexing situation that provides an illusion of privileges but excludes them from fully participating as U.S. citizens (Haney López, 2006; Nicholson et al., 2020). Both cases also exemplified early instances of Asian American individuals who were pressured by prevailing racial ideologies to eschew Blackness and assimilate into dominant norms of White supremacy.

Examples of anti-Black sentiments are deeply rooted in people of Filipino descent who may endorse colonial mentality, an internalized form of oppression characterized by a preference for Western attitudes and the denigration of Filipino culture following years of colonization by the United States (David & Okazaki, 2006a, 2006b). For example, internalized anti-Black sentiments in Filipino culture are evidenced by the systematic discrimination against the dark-skinned Ati people, who are indigenous to the Aklan region (Petrola et al., 2020). As a result of the mining, logging, and tourism industries, the Ati have been forced to relocate onto smaller plots of land, face physical violence, and are denied various human rights (Petrola et al., 2020). Other insidious anti-Black attitudes that permeate the Filipino worldview include White-centered beauty notions that venerate straight hair and light skin over textured locks and dark skin (Nadal, 2021; Rafael, 2000). Despite their documented toxic and dangerous consequences, skin whitening products in the Philippines are a billion-dollar industry (Mendoza, 2014). These examples relay cultural and economic implications that are predicated on histories of global imperialism and colonialism, which root out indigeneity in favor of Eurocentric values and White norms (Fanon, 1952). Examples of anti-Black sentiments in Filipino communities are a sample of the ways in which colonialist movements mapped anti-Blackness onto Filipino communities and culture by occupation of the land, terrorism, and brutality (David, 2013; Nadal, 2021).

History of anti-Black attitudes may also exist in Korean Americans following the 1992 Los Angeles riots. After White officers were exonerated in the beating of Rodney King and a Korean store owner fatally shot 15-year-old Latasha Harlins, tension erupted between the Black and Korean American communities due to the lack of accountability for the killing of a Black person. Media reports of widespread rioting, theft, injuries, and damage to businesses were attributed to poor race relations between African American and Korean communities and larger issues of systemic racism were disregarded (Oh, 2010; Sharma, 2018). Despite calls to law enforcement for help, Korean voices were overlooked by the police (Yoon, 1997), which potentially illustrates how the law enforcement system reacts in favor of White interests. Once again, White media highlighted the undercurrent of racial tension between ethnic and racial groups as noteworthy and masked preexisting racial coalitions between Black and Asian American communities. These news stories deterred Asian American and Black communities from looking outward and acknowledging the larger issues of ongoing police brutality and inequitable justice systems (F. Ho & Mullen, 2008).

Chinese Americans may harbor anti-Black notions following the conviction of Peter Liang, who fatally shot Akai Gurley in New York City (W. Liu, 2018). Although he was the first officer indicted for killing an unarmed and innocent Black man, Liang’s conviction resulted in conflict between Chinese American and Black American communities (R. Liu & Shange, 2018; W. Liu, 2018). Many individuals within Asian American communities argued for the fair sentencing and punishment of Liang (Tran et al., 2018), but others protested the charge and believed the courts used him as a scapegoat to detract from BLM activists who called for police reform (R. Liu & Shange, 2018; W. Liu, 2018).

Challenging Historical Anti-Blackness in Asian American Communities

Challenging anti-Blackness in Asian American communities underscores a cultural paradox. On one hand, Asian American individuals, especially East Asian subgroups, benefit from social and economic privileges because of their proximity to Whiteness and identities as non-Black minorities (Bonilla-Silva, 2018; Poon et al., 2016). Thus, some Asian American individuals endorse aspects of the model minority myth because of the privilege it affords (Kim, 1999), even at the expense of maintaining a racially triangulated identity (Bonilla-Silva, 2004; Poon et al., 2019; Yi et al., 2020). Anti-Blackness therefore moves beyond prejudicial attitudes against Blacks and encompasses a performance of Whiteness (W. Liu, 2018).

Movements initiated by younger Asian American generations that challenge anti-Black sentiments (e.g., #Asians4BlackLives) are gaining traction (Anand & Hsu, 2020; Lee et al., 2020) and can help Asian immigrants move beyond their own unacknowledged pain and racial trauma to appreciate the challenges of other marginalized communities (David et al., 2019; Tran et al., 2018). For example, Letters for Black Lives is a crowdsourcing project that empowers communities of color to have conversations about anti-Blackness with older generations (R. Liu & Shange, 2018) who may endorse anti-Black attitudes following injustices against Asian people (e.g., Peter Liang) or anti-Asian historical events (e.g., the LA riots). These letters help younger Asian American communities describe ambiguous and complex issues related to social justice, racism, and systemic oppression with their families and have been helpful in promoting support for the BLM movement (Arora & Stout, 2019).

Extant Research on Racial Coalitions