Nov 9, 2021 | Volume 11 - Issue 4

J. Claire Gregory, Claudia G. Interiano-Shiverdecker

Using Moustakas’s modification of Van Kaam’s systematic procedures for conducting transcendental phenomenological research, we explored ballet culture and identity and their impact on ballet dancers’ mental health. Participants included four current professional ballet dancers and four previous professionals. Four main themes emerged: (a) ballet culture—“it’s not all tutus and tiaras”; (b) professional ballet dancers’ identity—“it is a part of me”; (c) mental health experiences—“you have to compartmentalize”; and (d) counseling and advocacy—“the dance population is unique.” Suggestions for counselors when working with professional ballet dancers and professional athletes, such as fostering awareness about ballet culture and its impact on ballet dancers’ identity and mental health, are provided. We also discuss recommendations to develop future research focusing on mental health treatment for this population.

Keywords: ballet dancers, culture, identity, phenomenological, mental health

“Dancers are the athletes of God.”—Albert Einstein

Professional ballet dancers’ mental health experiences are sparse within research literature (Clark et al., 2014; van Staden et al., 2009) and absent from the counseling literature. Most research including ballet dancers focuses primarily on eating disorders, performance enhancement (Clark et al., 2014), and injuries (Moola & Krahn, 2018). Although these topics are crucial to dancers’ wellness, explorations of ballet dancers’ mental health that do not primarily focus on eating disorders are also important. Increasing professional ballet dancer and athlete mental health research could provide counselors with deeper awareness of the populations’ needs. Further, counselors have access to the American Counseling Association’s (ACA; 2014) Code of Ethics, which is relevant for all clients, including athletic populations. However, the counseling profession lacks specific sports/athletic counseling ethical codes, competencies, and teaching guidelines (Hebard & Lamberson, 2017). The only mention of “athletic counseling guidelines” appears in a 1985 article from the Association for Counselor Education and Supervision (Hebard & Lamberson, 2017). In their initiative to increase counselor response to the need for athletic counseling, Hebard and Lamberson (2017) implored counselors to advocate for athletes’ mental health. Further, the researchers stated that it is common to view athletes as privileged and idolize them for their physical endurance; however, this perception may leave athletes vulnerable to mental health concerns. Recent examples of mental health difficulties experienced by formidable professional athletes include tennis player Naomi Osaka choosing to decline after-match news conferences to safeguard her mental health and gymnast Simone Biles removing herself from some events at the Tokyo 2020 Olympics in order to protect her mental health.

Moreover, scholars have been increasingly devoted to understanding the cultures within which performing artists are trained and developed and recognizing their role in supporting the health and well-being of the artist (Lewton-Brain, 2012; Wulff, 2008). For counselors, the ACA Code of Ethics (2014) promotes gaining knowledge, personal awareness, sensitivity, and skills pertinent to working with a diverse client population (C.2.a). However, this is difficult with limited current data or research seeking to advance knowledge of the culture of performing institutions and how they relate to artists’ mental health experiences. Therefore, an exploration of ballet culture and identity and their impact on ballet dancers’ mental health experiences could help inform counselors and counselor educators about the counseling needs of this population.

Mental Health Among Elite Athletes and Performing Artists

Because of the scant literature focusing directly on professional ballet dancers’ mental health, we included research findings from articles examining mental health among athletes and performing artists. Although differences exist between professional ballet dancers, elite athletes, and performing artists, a professional ballet dancer straddles multiple environments. For example, an elite athlete trains to win a national title or medal, possesses more than two years of experience, and trains daily to develop talent (Swann et al., 2015). Rouse and Rouse (2004) suggested that performing artists’ goals or outcomes are to create art and achieve a high performance level with audience satisfaction. Similar to these groups, a professional ballet dancer trains almost every day, which requires extreme dedication. They must comply with high physical and mental demands to develop their ballet technique for performing and entertaining audiences.

Scholars have discovered that elite athletes experience a high prevalence of anxiety, eating disorders, and depression compared to the general population (Åkesdotter et al., 2020; Gorczynski et al., 2017). At the same time, eating disorders are overrepresented in elite athlete studies because of the requirement that elite athletes maintain a specific stature for their profession (Åkesdotter et al., 2020). Interestingly, few elite athletes reported anxiety disorders even though they scored in the moderate range on the General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7; Åkesdotter et al., 2020). This could indicate that elite athletes normalize their anxiety and eating concerns, even at a clinical level. Likewise, performing artists display disproportionately high reporting rates for mental health disorders, such as depression, anxiety, and stress, when compared to the general population (Van den Eynde et al., 2016; van Rens & Heritage, 2021). Given professional ballet dancers’ emotionally demanding performance levels as performing artists and their physicality as athletes, they may share similar mental health experiences with elite athletes and performing artists, yet these experiences remain unknown.

Ballet Culture and Professional Dancers’ Mental Health

Literature exploring ballet dancers has focused on culture (Wulff, 2008), development (Pickard, 2012), emotional harm (Moola & Krahn, 2018), injury prevention (Biernacki et al., 2021), and disordered eating (Arcelus et al., 2014). Ballet, with origins in the Italian and French courts, is an age-old culture that fuses beauty and athleticism (Kirstein, 1970; Wulff, 2008). Influenced by social and cultural forces in the Western world (Kirstein, 1970), ballet culture is synonymous with tradition and hierarchy (Wulff, 2008). Ballet culture holds steadfast to idealistic tenets in which dispositions (e.g., tenacity), perceptions of an ideal body, and actions (e.g., constant rehearsals) provide dancers the ability to illustrate a story through movements (Wulff, 2008). Exquisite sets, costumes, and movements create a unique experience and can produce a visceral reaction in the audience (Moola & Krahn, 2018).

Yet a strong commitment to the art form requires ballet dancers to work with their bodies for hours, sustain injuries, and work through chronic pain (Pickard, 2012), often leading to emotional distress (Moola & Krahn, 2018). Physical requirements also make dancers three times more vulnerable, compared to non-dancers, to suffer from eating disorders, particularly anorexia nervosa and those labeled by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as eating disorders not otherwise specified (Arcelus et al., 2014). van Staden et al. (2009) focused directly on ballet dancers’ mental health, finding that professional ballet dancers also experience mental health concerns due to negative body image and stress. The vast majority of these studies originated from countries outside the United States, including South Africa (van Staden et al., 2009), the United Kingdom (Pickard, 2012), and Canada (Moola & Krahn, 2018). The scarcity of scholarly attention on professional ballet dancers’ mental health within the United States is concerning given the evidence of emotional distress in similar populations. Counselors may be less than effective without a clear understanding of this population’s mental health needs. Understanding the cultural context and its impact on ballet dancers’ mental health in the United States, therefore, requires further exploration.

Purpose of the Present Study

The purpose of this study was to explore ballet culture and identity and their impact on ballet dancers’ mental health experiences. The guiding research questions were (a) How do professional ballet dancers define ballet culture and identity? (b) What are the mental health experiences of professional ballet dancers? and (c) What are professional ballet dancers’ suggestions for counseling and advocating with this population?

Method

Given the purpose of this study, we chose a transcendental phenomenological approach as an appropriate method to discover and describe the essence of participants’ lived experiences. Both van Staden et al. (2009) and Moola and Krahn (2018) utilized phenomenological approaches to explore ballet dancers’ mental health and experiences of emotional harm. Originally introduced by Husserl (1970), this approach positions researchers to focus on the individual experience while also identifying commonalities across participants (Hays & Singh, 2012). Further, in transcendental phenomenology, researchers set aside preconceived ideas, seeking to add depth and breadth to people’s conscious experiences of their lives and the wider world. In Moustakas’s (1994) modification of Van Kaam’s method of transcendental phenomenology, researchers aim to collect the experiences of participants while consistently assessing and addressing their biases to produce a purer and transcended description of the researched phenomena. Because our lead author, J. Claire Gregory, possesses a background as a professional ballet dancer, the framework of transcendental phenomenology provided the needed structure for identification of biases and preconceived notions, allowing us to evaluate our positionality to the data.

Research Team Positionality

Our research team consisted of Gregory, a doctoral candidate and licensed professional counselor, and Claudia Interiano-Shiverdecker, an assistant professor in counselor education and supervision in a CACREP-accredited counselor education program. Gregory is a Caucasian female and was a professional ballet dancer for 7 years. Interiano-Shiverdecker is a Honduran female with extensive experience conducting qualitative research and clinical experience primarily focused on trauma, crisis, and grief. We have a combined 13 years in clinical practice. Moustakas implored researchers to uphold epoché, “a Greek word meaning to refrain from judgment, to abstain from or stay away from everyday, ordinary ways of perceiving things” (1994, p. 85), by bracketing their own opinions, theories, and expectations. Bracketing is a defining characteristic of transcendental phenomenology in which researchers set aside their own assumptions, to the extent possible, to allow individual experiences to emerge and inform a new perspective on the phenomenon (Moustakas, 1994). Given the composition of the research team and the methodology employed, it was vital to engage in ongoing conversations about our collaboration, data collection and analysis, participants, and the data. Therefore, we addressed specific biases by engaging in virtual weekly bracketing meetings for over a year. Before meetings, Gregory would log memos about thoughts during data collection and analysis. Interiano-Shiverdecker would serve as a consultant to address biases. The biases discussed included a desire to not focus on mental health disorders typically discussed in the literature (e.g., eating disorders) and a desire to highlight professional ballet dancers’ strengths to balance out negative stereotypes. Throughout data analysis, we noted that participants discussed other presenting mental health issues and the connection of ballet culture to the development of those issues, including eating disorders. We operated from a social constructivist research paradigm in which multiple realities of a phenomenon exist (ontology), researchers and participants co-construct knowledge (epistemology), and context is valuable (axiology; Hays & Singh, 2012). This approach primarily focused on reflecting the participants’ voices while recognizing our roles as researchers, so we intentionally did not incorporate a theoretical framework to analyze our data.

Sampling Procedures and Participants

The transcendental phenomenological research procedures we followed included (a) determining the phenomenon of interest, (b) bracketing researcher assumptions, and (c) collecting data from individuals who have directly experienced the phenomenon. Therefore, after receiving approval from our university’s IRB, we used purposive and snowball sampling to recruit professional ballet dancers in the spring and summer of 2020.

Purposive sampling allowed us to select participants for the amount of detail they could provide about the phenomenon (Hays & Singh, 2012). We intentionally recruited individuals who identified as a professional ballet dancer currently or in the past and were 18 years or older, aiming for a sample of at least five participants (Creswell, 2012). The parameters for “professional ballet dancer” were being a dancer with a professional ballet company and receiving financial payment. Gregory emailed potential participants, contacted professional ballet organizations to request distribution of the recruitment flyer among their members, and posted on Facebook groups used by professional ballet dancers. This email and post included an invitation to participate, a link to a demographic form, and an informed consent form. A total of seven eligible volunteers responded to recruitment emails and posts on Facebook groups. Through snowball sampling, we recruited one more participant. Seven of the dancers had worked with the same professional ballet company as Gregory, but only two had danced concurrently with her, which occurred 10 years prior to data collection.

All participants who contacted us about the study stayed enrolled and completed the interview session. Table 1 outlines the demographic information of each participant, with the use of pseudonyms. Five of the eight participants lived in a southern region of the United States, while three participants lived in northwest and eastern regions. All participants identified as Caucasian. Two participants currently worked as professional ballet dancers attached to a company; the other six were ballet teachers, office employees, freelance dancers, students, or nurses.

Data Collection Procedures

Moustakas (1994) recommended lengthy and in-depth interactions with participants in transcendental phenomenology in order to understand participants’ experiences of the phenomenon and the contexts that influence those experiences. Participation required professional ballet dancers to complete a demographic questionnaire, take a picture that represented their perspective on mental health while dancing professionally, and complete an individual semi-structured interview. We chose to include the picture to include creative expression, a vital element in ballet culture. The use of pictures during the interview process facilitated a representative and safe discussion around mental health. Although we did not directly analyze the pictures, they served as catalysts for interview questions. In qualitative research, photography can supplement primary data collection methods when participants struggle to utilize words alone to capture an experience (Hays & Singh, 2012).

Table 1

Participant Demographic Information

| Pseudonym |

Gender |

Age |

Race |

Professional Status |

| Abby |

F |

31 |

Caucasian |

Former Professional |

| Cleo |

F |

28 |

Caucasian |

Current Professional |

| Luna |

F |

35 |

Caucasian |

Former Professional |

| Mica |

F |

30 |

Caucasian |

Former Professional |

| Monica |

F |

37 |

Caucasian |

Former Professional |

| Paul |

M |

25 |

Caucasian |

Current Professional (Freelance) |

| Sophie |

F |

33 |

Caucasian |

Current Professional |

| Zelda |

F |

25 |

Caucasian |

Current Professional (Freelance) |

We developed a 9-item open-ended interview protocol (see Appendix) intended to explore participants’ experiences with mental health, counseling, and advocacy. Gregory conducted all interviews, which lasted from 30 to 60 minutes with an average of 40 minutes, and transcribed each interview verbatim afterward. Three interviews were in person, while six interviews occurred over the phone because of the COVID-19 pandemic. During development, we decided to begin with a simple question to help the dancer feel more at ease. In the next five questions, we utilized their picture to discuss mental health. Because the term “mental health” may or may not be known to the dancers, or it may hold stigma, we felt the picture could produce more insight and depth of the concept. Question 6 asked the dancers to consider their social context and its relation to their mental health. We also chose to include a question asking about ballet dancers’ strengths, as this seems to be rare within performing artist and athlete literature. Next, we directly asked the dancers how counselors could help and then asked a final question that created space for any other relevant thoughts. Through these interviews with eight (seven female, one male) professional ballet dancers, we reached data saturation, meaning that no new information emerged in the data creating redundancy.

Data Analysis

We followed Moustakas’s (1994) modification of Van Kaam’s steps for data analysis, which included (a) developing clusters of meaning, (b) using significant statements and themes to write a description of what participants experienced (textural description) and how they experienced it (structural description), and (c) describing the essence of participant experience from the textural and structural descriptions. First, Gregory engaged in member checking by emailing each participant their interview transcript to ensure accuracy and provide an opportunity to redact any statements. No participant changed their transcript.

Gregory then reviewed each transcript independently, highlighting significant statements or quotes that conveyed participants’ experience. This process is known as horizontalization (Moustakas, 1994). Then, we discussed each identified statement and assigned meaning to similar statements (i.e., clusters of meaning). We used NVivo software for data analysis to ensure consistency, transparency, and accuracy. NVivo, a qualitative data analysis software, aids researchers with consistency in assigning codes to similar topics and allows the research team to cross-check codes for accuracy.

We then determined the invariant constituents, or the final code list, from redundant and ancillary information through a process of reduction and elimination. For example, we eliminated codes that did not illustrate participants’ lived experiences in relation to the purpose of this study. Through the process of reduction, we merged codes if their meaning was similar. These processes allowed us to have a final list of codes that were not repetitive and aligned with the purpose of the study. Using the final codebook, we began the recursive coding process to recode every interview and reach final consensus. Recursive coding, a qualitative data analysis technique, is very useful when analyzing interview data, allowing researchers to compact the data into different categories and illuminating patterns within the data not otherwise apparent (Hays & Singh, 2012). For example, we noticed several codes that illustrated traditions or customs, both positive and negative, that ballet dancers embraced, so we decided to categorize codes about traditions and customs, in both negative and positive categories, to illustrate ballet culture.

Following this initial coding, we explored the latent meanings and clustered invariant constituents into themes, ensuring that all themes were representative of the participants’ experiences. We then synthesized themes into textural descriptions of participants’ experiences, including verbatim quotes and emotional, social, and cultural connections to create a textural-structural description of meanings and essences of experience (Moustakas, 1994). Using the individual textural-structural descriptions, we proceeded to create composite textural and structural descriptions of reoccurring and prominent themes. Finally, Gregory engaged in the member-checking process for a second time by sending the final themes to all participants via email. Four participants responded, all supporting the final themes.

Strategies for Trustworthiness

To ensure quality, we engaged in multiple strategies to meet trustworthiness criteria, such as transferability, confirmability, dependability, and credibility. Specific strategies included using researcher triangulation, member checking, in-depth description of the analyses, and thick description of the data (Hays & Singh, 2012). Weekly meetings for a year helped reduce researcher bias through openly challenging each other with any conclusions. We also engaged in two rounds of member checking for dependability and confirmability. In addition, we utilized an external auditor with previous experience in qualitative research who was unfamiliar with ballet traditions and culture to aid in establishing confirmability of the results and credibility of our data analysis process (Hays & Singh, 2012). The auditor reviewed our NVivo file for data analysis and notes, and the final presentation of the results in a Microsoft Word document. Although the external auditor provided us with APA suggestions, she had no critical feedback regarding our analysis. Instead, she supported our findings on ballet culture that provided a new insight for counselors. Finally, we used thick description when reporting the study findings to increase trustworthiness. Utilizing thick description allowed us to depict deeper meaning and context of the data instead of only reporting the basic facts (Hays & Singh, 2012).

Results

We identified four prevalent themes about professional ballet dancers’ mental health experiences: (a) ballet culture—“it’s not all tutus and tiaras”; (b) professional ballet dancers’ identity—“it is a part of me”; (c) mental health experiences—“you have to compartmentalize”; and (d) recommendations for counseling and advocacy—“the dance population is unique.”

Ballet Culture—“It’s Not All Tutus and Tiaras”

All eight participants described ballet as a unique culture with its own set of customs and ingrained traditions. One of the participants, Monica, further elucidated this point: “The traditions of ballet are very old-fashioned, but it’s beautiful when something endures and exists after hundreds of years.” Throughout their narratives, dancers mentioned patterns of “good” and “bad” sides to ballet culture. “It’s not all tutus and tiaras or the perfect life. There is so much beneath the surface,” explained Cleo. To clarify this theme, we divided it into two subthemes: negative aspects of ballet culture and positive aspects of ballet culture. Although we present this theme in two opposing subthemes for simplicity, dancers’ experiences existed along a continuum.

Negative Aspects of Ballet Culture

All of the participants shared that customs of ballet culture focused primarily on requirements indispensable to successfully performing a job that was emotionally and physically demanding. The dancers’ comments centered around physical body requirements and arduous training, highlighting the need for extreme physical athleticism to perform at a professional level. Monica explained, “They [ballet dancers] have obvious physical strength, stamina, endurance, and mind over matter for what they need to do.” “We’re a very underrated athlete,” echoed Abby. Zelda added, “I would compare us to what the world knows a little bit better as gymnastics for the Olympics.”

Although no interview questions specifically asked about the negative side to ballet, participants shared feeling constant stress, pushing their bodies and minds to their limits, worrying about body image and injuries, and feeling pressure to find and keep employment. It was commonplace for participants to experience a sense of pressure and stress from internal and external forces. For example, Paul stated, “I think about my ballet career, and I think how I was tired all the time, because I would wake up and do so much.” Echoing this feeling, Zelda shared, “I was half thriving, half dying inside.” Other participant statements emphasized feeling mentally broken with the lack of time for any outside hobby and having no power as a dancer. Abby stated, “In ballet, everything was just so competitive and mind twisting. I was raised with the idea that every day is an audition.” She added, “This could be your day, or if you don’t work hard today then 3 months from now it is going to creep up on you. So, it’s this weird, like, permanence that is doomed upon us.” According to Abby, there was a daily pressure to achieve greatness, which at times caused injury. For Cleo, a current professional ballet dancer, employment pressure and injury were prevalent: “I actually had an injury where I was not able to dance for a year. . . . I managed to sprain my ankle in three places. I had spent the entire summer rehabbing and keeping it in a boot.” Yet she explained that because she was “scared [of not being asked to return to the dance school], I danced on it for weeks after the initial injury.” Cleo also saw her peers struggling with the same issue:

My friend had food poisoning yesterday. She is still sick today and they told her she has to come in because they were setting the Adagio scene . . . she literally left class to throw up and then came back to class and the whole time was trying not to throw up.

Other professional dancers echoed these fears of financial stress and employment stability, which justified their reasons to push their minds and bodies to the limit, despite physical or mental injuries. Despite perceptions of glamour, Paul highlighted the financial strain that most ballet dancers experience by detailing how he made only “$100 a week and lived in a place that charged me $250 a month.” Even with their efforts, three participants had lost their dancing jobs. Luna believed it was her weight that got her fired, while Paul shared, “I would work super hard all day, back to the gym at night, eat super healthy, and I was still fired for not being good enough, according to my old boss.”

Positive Aspects of Ballet Culture

Despite these intense demands, all participants also discussed positive qualities of ballet culture. These included connection to others, learned adaptability, and creating a story for the audience. Paul highlighted, “Even with the bad parts, there’s a lot more good than there was bad. . . . It’s one of those things, you’re like, I love it so I’ll do it for whatever money.” Monica reflected on her career, saying, “I see fond memories and really good times.” Several participants shared how long training hours and a common goal created a unique connection to others that was difficult to experience elsewhere. Monica passionately stated that “dancers thrive in the sense of community. When you are in a company you are exactly that—part of the greater company and you work together.” Mica shared, “You aren’t really your own person when you are dancing in a professional setting.” “It helps create friends and that was the beauty behind it, you had a support system,” added Luna. Three of the dancers shared their enjoyment of creating an onstage story for the audience. Mica enjoyed how ballet “uses the body to give meaning to stories, more so than other forms of dance.” Luna shared, “We were giving back to the community and being a part of the arts. That was great. I loved that.”

Professional Ballet Dancers’ Identity—“It Is a Part of Me”

All dancers either directly or indirectly attested to a ballet identity and how it influenced their development. To display the range of experiences, we described this theme in two subthemes: ballet dancer traits and connections to their ballet dancer identities. The first subtheme illustrates aspects that ballet dancers might share, while the second theme discusses how participants connected these traits to their personal identity.

Ballet Dancer Traits

All participants shared traits they felt were central to life as a professional dancer, such as tenacity and grit, that influenced their identity during and after dancing. Luna, Mica, Sophie, and Zelda mentioned the discipline a dancer must possess for a successful ballet career. “The level of discipline, I think, is unmatched,” Mica fervently stated. Sophie, Mica, Zelda, and Paul mentioned that their determination for continuous improvement represented their role on stage and ability to maintain their jobs. Sophie expressed, “Your determination, your artistic expression, all of those things include the whole person.” The dancers expressed an ability to push through any odds knowing that, eventually, their hard work would pay off. Sophie shared:

Delayed gratification I feel is a big one [strength], especially in a society with everything now being instant and we are always on our phones, but to work on something slowly over time and be patient. Just trust that hard work pays off.

Dancers indicated a connection between their transformation as dancers and their development as adults. Cleo shared, “If you make it to a professional, you are one of the few that had a hard road, and it makes you have a very thick skin that can help in all matters of life.”

Connection to Their Ballet Dancer Identities

All dancers expressed both positive and negative emotions about their ballet identity, ranging from gratitude to contempt. Four participants expressed that dancing was not just something they did, it was who they were. For them, ballet, and the culture of ballet, were integral parts of their identity. During her interview, Zelda paused after a question about why she continues to dance and simply stated, “It is a part of me.” Sophie shared, “Over the years, I think I stuck with it because it became wrapped up in my identity a bit. This is who I am, this is what I do, this is what makes me special.” Additionally, Cleo and Sophie identified the power and connection they felt while dancing on stage. This connection gave meaning to their dance career. Sophie shared, “Somehow dance felt like it gave me the most ability to participate in music in a way I really wanted to and a kind of level of expression I never really had.”

Yet four participants also felt that their identity had evolved past ballet. “It’s a picture that represented me at a point in time, but I don’t feel it represents me anymore,” shared Mica. Paul, a freelance professional, shared, “I feel like it definitely was how I viewed myself. But I’m not 100% sure if I do or don’t feel that way now.” Monica, a former professional, explained:

Our identity is who we were and what we had, but that is not my core identity. I know who I am in my identity, and it is in Christ who made me, and also just me as a person is more than what I did and what I do on my days at a job.

Mental Health Experiences—“You Have to Compartmentalize”

Utilizing pictures to discuss mental health attended to participants’ preferred form of expression. As Zelda stated early in her interview, “I don’t know how to put it into words. It’s hard.” Despite their dedication and passion, all dancers spoke of the demanding nature of professional dancing and its impact on their mental health. Their conversation around mental health focused on two areas: perfectionism and the perfect body and compartmentalization.

Perfectionism and the Perfect Body

All dancers felt they needed an additional picture to represent the darker side of ballet or related this darker side to imperfections within the picture. Figure 1 displays Paul’s picture of artwork, which the dancer felt represented the outward appearance of perfection but included lumps of paint (i.e., imperfections), a representation of his mental health.

Figure 1

Paul’s Picture of His Mental Health Experience as a Professional Ballet Dancer

Despite there being no interview questions about their body image, seven of the eight dancers shared thoughts about body image concerns or pressure to develop a certain physique. Throughout their dancing career came numerous hours of practice in front of mirrors. Abby’s chosen picture displayed part of a bathroom mirror: “When I look into the mirror, a lot of judgments come back in, and ballet is all based off of opinions and judgments that really mess with your head.” She added, “Everything revolved around the mirror, and if the mirror said it was ok, then my brain said it was ok . . . with ballet and mental health, I feel like a lot of my mental health was based off the reflection.” Paul also shared, “I was going to the gym every single day and was in really good shape but was still told I was not in ballet shape.” Monica shared another company dancer’s experience: “Even though she was a gorgeous dancer and had the most incredible feet and legs, she was told she was overweight, and she did not know, in those days, how to deal with it.” Luna spoke openly about feelings of depression when she gained weight: “When I got fired, I would go into periods where I gained 20 pounds because of my depression. The whole reason I was fired was because I got too big.” She later added, “I started losing it when I got hired back but was not allowed to be in productions because I was too big. . . . The depression made me eat and go into a dark place.” However, Luna also spoke about current cultural changes regarding the “ideal” body shape for ballet dancers in the United States: “Nowadays I feel that they [ballet companies] have embraced differences in dancers.”

Although participants recognized the benefits of an unbreakable determination, discipline, and rigor toward their professional career, they also noted the emotional consequences of their dedicated work. Cleo best illustrated this point: “It just felt like it didn’t matter how hard I worked, it just took a toll. . . . I thought it [ballet] was beautiful, and 13 years ago I believed this, but then things started to turn darker mentally for me.” Mica shared, “I would say a lot of us, we have anxiety and depression, but we are also crazily mentally strong . . . like me, for example, I was told I was too fat from the age of 12.” With this constant stress, the dancers felt their mental health fluctuated with external forces (i.e., thoughts about not being good enough). Zelda stated, “I had constant anxiety of not being good enough.”

Compartmentalization

Another prominent subtheme for all of the dancers was compartmentalization. The dancers described compartmentalization of thoughts and feelings as a healthy coping mechanism for some and a hindrance for others. Abby and Sophie spoke about their need to separate from their feelings and thoughts to perform well. Abby told herself, “Do not think that way. You work really hard and you can put all those thoughts into a little box and hopefully, eventually, get rid of it.” She added that “when the thoughts creep up, I try to put them into my little mental box and try not to open it.” Sophie also spoke in depth about how she maintained her mental health and navigated her negative feelings:

I have to separate myself from my feelings sometimes. I have to remember that my feelings aren’t me. . . . You have to believe you can make it happen and it’s going to work out and be resilient enough to take rejection and injuries, and the uncertainty of finances. You have to hold on and believe it will happen for you. . . . Over time I have become more resilient or grounded. My mental health is very dependent on how I take care of the situations I am in.

However, several dancers also explained how this compartmentalization fostered a negative approach toward mental health, silenced their voice, and led them to bottle up their feelings. Abby described, “If you are sad and can’t handle it, then the director is going to see that, and consequences will happen . . . then it’s the worst . . . we are conditioned to accept whatever is given to us.” Cleo added, “You have to compartmentalize, to hold it in and aren’t allowed to talk about it . . . you’re not allowed to feel the validation of ‘I’m bothered by this.’ It’s almost wrong to feel bothered by this.” When analyzing the data, we noticed that the four participants who were former professional dancers noted an improvement in their mental health after their life in ballet. Sophie also illustrated changes in dancers’ mental health: “It is able to grow and change and be cultivated. So, I do not think mental health as a dancer is fixed.”

Recommendations for Counseling and Advocacy—“The Dance Population Is Unique”

As the conversation turned toward mental health experiences, all participants expressed recommendations in two areas: counseling and society’s view of ballet dancers and advocacy.

Counseling

All participants discussed recommendations for counseling when working with professional ballet dancers. Regarding counseling, Mica shared, “The dance population is unique in itself. A counselor being able to counsel to this is very important.” She further explained, “It’s not the same as advising someone who’s on a basketball team, nor is it the same as advising someone who’s on a theatre crew. It’s just different. It’s an athlete and it’s an artist.”

Abby also urged counselors to recognize trauma among this population: “I think counselors should be aware of emotional abuse and treat dancers as such.” Monica described how ballet dancers joined voices with the MeToo movement: “It just seemed like the movement of women being able to finally express what had happened to them and the abuse they had been enduring was very empowering.” At the same time, she indicated that a lot of people responded with “well that’s just what ballet is.”

Participants highlighted dancers’ absence of mental health services in their work contracts. “Just having someone to talk to would be nice. I know it’s not covered on a lot of health insurances or dancers’ insurance,” said Cleo. “It would be really cool if it were in the context of the studio and dancers could have one session a month at least . . . individual session, group sessions . . . I think a lot of people would jump at the opportunity,” stated Abby. Monica further explained how a counselor could “do a lot to sustain dancers and maybe help their careers because they might be less prone to injury if they aren’t sad and depressed or feeling alone or pushing themselves beyond their breaking point.” She added how counselors may support company staff: “I think there is a lot on the shoulders of the artistic director or one of the ballet mistresses or ballet masters to be an emotional shoulder or a listening ear.”

Another prevalent tenet woven throughout the dancers’ interviews was counselors’ awareness of ballet culture. Three dancers specifically mentioned that if counselors increased their awareness of dance careers, it might help dancers open up to counselors. Paul stated, “I think about when I was dancing, if someone had just been like ‘oh well, you don’t have to be super skinny to dance.’ I’d be like, you don’t know anything, ya know?” Another dancer shared:

Counselors may not need dance experience, but it would be helpful for the dancers if counselors at least have an idea of what a rehearsal day is . . . how many hours we are dancing, how many dancers have second jobs, how often we perform, it adds context . . . having an understanding of the rigors and demands from within the profession.

Society’s View of Ballet Dancers and Advocacy

At some point in their interviews, all participants described ballet dancers’ mental health as hidden or unknown to society, and therefore believed that the first step for advocacy required awareness. Participants explained that when people go to the theatre to watch The Nutcracker around the holiday season or attend Romeo and Juliet, they see a story, a real-time depiction of magic and narrative. Yet participants felt that this led society to view dancers as having “glamourous lifestyles” or, because of Hollywood, believe that dancers “are frail individuals that do not have a real job, throw their friends down the stairs, and steal husbands.” Cleo openly spoke about the hidden side of the ballet world when sharing her picture:

The idea is that it’s so glamorous and they have this perfect life, it’s like the same way they [society] perceive celebrities and they have these glamourous lives and everything is perfect when you see the surface and the smile you are forced to put on, but they do not see everything that goes on underneath. That’s why I love this photo: you don’t know what the person is actually feeling. . . . On the outside I am a very bubbly person, and people don’t know anything going on behind, I guess behind the curtain.

Along these same lines, participants advocated for gender equality within the profession. Although no interview questions asked about gender differences, three dancers pointed out this discrepancy by sharing that women are under extreme pressure to maintain their dance careers. Cleo and Abby also identified how most directors were male. Abby expressed this always “trying to appease the person in charge, who is almost always a man.” For five of the participants, the company director played a vital role in how they viewed themselves. Although some dancers noted overall societal changes and awareness that dancers did not have to fit “this anorexic ballerina” stereotype, some felt that overcoming long-lasting traditions in ballet culture of “skinny equals better” required significant change.

Discussion

The purpose of this qualitative study was to provide a better understanding of ballet culture and its impact on dancers’ identity and mental health. More specifically, we sought to explore different facets of professional ballet dancers’ mental health, while also providing cultural context to professional ballet dancers’ lived experiences. Our attention to cultural context is parallel to trends over the past decade reflecting scholars’ increased focus on performing artists’ training environments to understand their experiences (Lewton-Brain, 2012). Using this perspective allowed us to offer recommendations for counseling and advocacy directly inspired by the ballet dancers’ viewpoints.

The findings from this study resemble descriptions of belief systems and practices entrenched in ballet culture previously discussed in the literature (Wulff, 1998, 2008). One overarching premise presented by the dancers was their need to acquire physical strength, stamina, and a “mind over matter” attitude to have successful ballet careers. The positive and negative qualities of ballet culture created a constant push and pull; however, the participants kept dancing. They recognized their hardships and yet believed enduring them was necessary to live their dreams. The ethos of ballet culture made going through hardships—restricting eating, dancing with injuries, and other stressors—worthwhile. Without providing a justification for these physical and emotional injuries, these new findings provide context to understand ballet dancers’ ideas on body, mind, and health. As some dancers shared, ballet was more than a career to them; it was a part of them, and life without it was hard to imagine.

Participant narratives revealed the ballet dancers’ numerous strengths, such as tenacity, grit, learned adaptability, and unbreakable discipline and rigor. At the same time, participants discussed several mental health hardships. To live up to their ballet dancing goals, dancers focused on their most highly used attribute—their bodies. Because of this, body concerns were prevalent in the findings. The dancers also relayed mental struggles and with them a will to succeed and compartmentalize, to carry on for the performance and the art despite physical and/or emotional pain and at times unsupportive or even abusive environments. Their experiences seemed to align with similar concerns shared by tennis player Naomi Osaka and gymnast Simone Biles. To illustrate, Biles withdrew from part of the 2021 Olympics because of a mind and body disconnect. Her decision earned criticism from the public. She later shared her struggles with mental health concerns (i.e., depression) and how stepping down from competition allowed her to prioritize her mental health and protect her body from potential serious injury.

Our findings also aligned with similar results found with elite athletes and performing artists (Åkesdotter et al., 2020; Gorczynski et al., 2017) and ballet literature in other countries that underscore concerns with disordered eating and body image issues that run deep within ballet culture (Clark et al., 2014; van Staden et al., 2009). Participants discussed anxiety, depression, trauma, abuse, and perfectionism. Their discussions indicated a connection, with anxiety and depression feeding into restrictive eating or other types of eating disorders, and an emotional turmoil following when they were unable to have control. Comorbidity between these mental health disorders and eating disorders is prevalent in the literature, and the present findings elucidate a similar connection among professional ballet dancers.

The findings from this study add to our understanding of professional ballet dancers’ mental health across the world by presenting, to the best of our knowledge, the only study within the United States to fully focus on a qualitative exploration of professional ballet dancer mental health experiences. Our findings expand on and reinforce Hebard and Lamberson (2017), whose work implored counselors to advocate for athletes’ mental health awareness. They stressed that athletes are idolized for their physical endurance, and this perception may leave them specifically vulnerable to mental health issues. Our participants expressed a similar concern and desired counseling services integrated into their schedule and provided by a counselor possessing an understanding of the ballet culture and its specific stressors. They believed that mental health services could not only address their mental health struggles and provide trained support, but also reduce physical injuries often caused by repressed feelings of sadness, loneliness, or insecurity. Participants expressed that advocating for this population should focus on increased access to mental health service providers with an awareness of ballet culture.

Lastly, these findings elucidate a need to evaluate aspects of ballet culture ingrained in tradition that can lead to physical and emotional injuries. Conversations about ballet culture and the emphasis on “petite ballerina dancers” are slowly becoming a part of current efforts to dismantle established perceptions of beauty, athleticism, and inclusion. As Pickard (2012) stated about herself as a dancer, “My body is ballet” (p. 25), and participants expressed that for counselors to advocate for and counsel this population, building awareness about this ongoing conversation while acknowledging the impact of ballet culture on professional ballet dancers’ mindset should be a requirement.

Implications for Counseling

Because of ballet culture and traditions, ballet dancers experience intense physical and mental demands. Counselors must attempt to understand ballet culture as well as its impact on dancer identity and mental health. Counselors need to remain aware of ballet culture when broaching the topic of weight and body identity influences, requirements for a successful ballet dancer, and the relationship between ballet standards and mental health disorders. From the dancers’ perspective, their physical form is directly related to their mental state or how they view themselves. Dancers’ identities intertwine with their bodies from a young age. Although this creates many positive experiences for the dancers, they also expressed how this can lead to depression, anxiety, and other mental health disorders. Considering these experiences, we encourage counselors to support dancers with a client-centered approach and to create an atmosphere of understanding about the dancers’ physical form as integral to their identity and their profession. Utilizing a client-centered approach would allow counselors to inquire about the dancers’ professional experience and help them build an understanding of the professional demands of ballet. Additionally, we encourage counselors to help professional ballet dancers explore their internal self-talk around comparing themselves to others and their relationship with their body.

Although not as prevalent in the data, the dancer statements about abuse are just as vital for counselor awareness. As Monica stated, ballet is a culture with centuries-old traditions and, according to five of the dancers, artist leadership tends to be authoritative in nature. Ballet requires certain physical attributes and training to achieve professional status, which can manifest as abusive relationships and power struggles. We suggest that counselors help professional dancers learn when certain demands may be perceived as abuse by the world outside of the studio. Providing psychoeducation of abuse (e.g., different forms of abuse, power and control wheel) can help ballet dancers differentiate these behaviors and seek help, when needed.

Although many dancers in this study expressed wanting counseling, it seems as though they feared counselors would not understand them or why they committed to such an intense lifestyle. The central need, according to the dancers, is for counselors to be aware of the unique ballet culture. For many dancers, ballet was a part of them, their identity, and something they felt drawn to always be improving. It is not a sport or a hobby, though there seem to be some commonalities between professional ballet dancers and elite athletes. According to the literature (Åkesdotter et al., 2020; Gorczynski et al., 2017), elite athletes experience intense physical demands and elevated anxiety. Our current findings from the dancers are comparable to these features. Therefore, counselors working with dancers may find some similarities with sports counseling. However, counselors should remain aware that sports are for competition and winning, whereas ballet is an art that seeks to provide the audience enjoyment and entertainment.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

As with all research, limitations exist because of many factors. For example, this study engaged a small, homogenous sample of ballet dancers with limited opportunity to dive deeply into within-group differences. All participants identified as Caucasian and many of the dancers had resided in the same geographical location at one point. We recognize that racial and geographical differences, among others, can significantly impact participants’ mental health experiences.

In addition, seven of the eight participants had experienced a prior dance connection with Gregory. Although this may have contributed to trust and more candid interviews, it is also possible that this resulted in biases despite our measures to ensure trustworthiness (e.g., weekly research meetings in order to bracket).

Another limitation is the ballet dancers’ subjective representation of their own mental health. Their illustrations of their experiences provide an inner look at their mental health yet do not guarantee an accurate or clinical representation of their experiences.

Because of the limited research examining professional ballet dancer mental health experiences, many opportunities remain open for future research. One recommendation is for future researchers to consider within-group differences (e.g., race, gender) through recruitment of a heterogenous sample. Also, considering the study’s participants all identified as Caucasian, we recommend future researchers explore the mental health experiences of minority ballet dancers, as they tend to be underrepresented in professional ballet companies in the United States. Additionally, this study included both former and current professional ballet dancers. Researchers may discover insightful data using a longitudinal study, as this could display information about the career transition period from professional dancer to former professional dancer. Other recommendations for future research include quantitative studies focusing on counseling interventions or prevention. Finally, some participants discussed instances of trauma, depression, and anxiety. Future researchers could examine specific mental health disorders and their comorbidity among ballet dancers by using the GAD-7 (Spitzer et al., 2006) for assessing anxiety and the BDI-II (Beck et al., 1996) for depression.

Conclusion

This qualitative study explored ballet culture and identity and their impact on professional ballet dancers’ mental health experiences, which resulted in the four themes of (a) ballet culture—“it’s not all tutus and tiaras”; (b) professional ballet dancers’ identity—“it is a part of me”; (c) mental health experiences—“you have to compartmentalize”; and (d) counseling and advocacy—“the dance population is unique.” A distinct culture exists for professional ballet dancers that includes traditions passed down since the 14th century. Hence, tradition, dedication, and commitment to their profession shape professional ballet dancers’ identities. Further, their identities straddle the environments of performing artists and elite athletes, creating contextually distinctive experiences. For counselors to adequately support professional ballet dancers, they must first build their awareness of ballet culture and the unique mental health needs and resiliencies of dancers.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Åkesdotter, C., Kenttä, G., Eloranta, S., & Franck, J. (2020). The prevalence of mental health problems in elite athletes. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 23(4), 329–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2019.10.022

American Counseling Association. (2014). ACA code of ethics. https://www.counseling.org/resources/aca-code-of-ethics.pdf

Arcelus, J., Witcomb, G. L., & Mitchell, A. (2014). Prevalence of eating disorders amongst dancers: A systemic review and meta-analysis. European Eating Disorders Review, 22(2), 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2271

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. (1996). Beck Depression Inventory–II [Database record]. APA PsycTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t00742-000

Biernacki, J. L., Stracciolini, A. S., Fraser, J., Micheli, L. J., & Sugimoto, D. (2021). Risk factors for lower-extremity injuries in female ballet dancers: A systematic review. Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine, 31(2), e64–e79.

Clark, T., Gupta, A., & Ho, C. H. (2014). Developing a dancer wellness program employing developmental evaluation. Frontiers in Psychology, 5(731), 1–9.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00731

Creswell, J. (2012). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Gorczynski, P. F., Coyle, M., & Gibson, K. (2017). Depressive symptoms in high-performance athletes and non-athletes: A comparative meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 51(18), 1348–1354. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096455

Hays, D. G., & Singh, A. A. (2012). Qualitative inquiry in clinical and educational settings. Guilford.

Hebard, S. P., & Lamberson, K. A. (2017). Enhancing the sport counseling specialty: A call for a unified identity. The Professional Counselor, 7(4), 375–384. https://doi.org/10.15241/sph.7.4.375

Husserl, E. (1970). The crisis of European sciences and transcendental phenomenology: An introduction to phenomenological philosophy. Northwestern University Press.

Kirstein, L. (1970). Dance: A short history of classic theatrical dancing. Praeger.

Lewton-Brain, P. (2012). Conversation with a clinician: William G. Hamilton, MD – Is more always more for young dancers? International Association of Dance Medicine and Science Newsletter, 19(4).

Moola, F., & Krahn, A. (2018). A dance with many secrets: The experience of emotional harm from the perspective of past professional female ballet dancers in Canada. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 27(3), 256–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2017.1410747

Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. SAGE.

Nejedlo, R. J., Arredondo, P., & Benjamin, L. (1985). Imagine: A visionary model for counselors of tomorrow. George’s Printing.

Pickard, A. (2012). Schooling the dancer: The evolution of an identity as a ballet dancer. Research in Dance Education, 13(1), 25–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/14647893.2011.651119

Rouse, W. B., & Rouse, R. K. (2004). Teamwork in the performing arts. Proceedings of the IEEE, 92(4), 606–615. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2004.825880

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

Swann, C., Moran, A., & Piggott, D. (2015). Defining elite athletes: Issues in the study of expert performance in sport psychology. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 16(1), 3–14.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.07.004

Van den Eynde, J., Fisher, A., & Sonn, C. (2016). Working in the Australian entertainment industry: Final report. Entertainment Assist, 1–181. https://crewcare.org.au/images/downloads/WorkingintheAustralianEntertainmentIndustry_FinalReport_Oct16.pdf

van Rens, F. E. C. A., & Heritage, B. (2021). Mental health of circus artists: Psychological resilience, circus factors, and demographics predict depression, anxiety, stress, and flourishing. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 53, 101850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101850

van Staden, A., Myburgh, C. P. H., & Poggenpoel, M. (2009). A psycho-educational model to enhance the self-development and mental health of classical dancers. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science, 13(1), 20–28.

Wulff, H. (1998). Ballet across borders: Career and culture in the world of dancers. Berg Publishers.

Wulff, H. (2008). Ethereal expression: Paradoxes of ballet as a global physical culture. Ethnography, 9(4), 518–535. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1466138108096990

J. Claire Gregory, MA, NCC, LPC, LCDC, is a doctoral candidate at the University of Texas at San Antonio. Claudia G. Interiano-Shiverdecker, PhD, is an assistant professor at the University of Texas at San Antonio. Correspondence may be addressed to J. Claire Gregory, Department of Counseling, 501 W. César E. Chávez Boulevard, San Antonio, TX 78207-4415, jessica.gregory@utsa.edu.

Appendix

Interview Protocol

- Tell me a little bit about yourself.

- Tell me about the picture you took and how this represents your understanding of mental health as a professional ballet dancer.

- Is this picture representative of your mental health? If so, how?

- What do you see here when you look at your picture?

- What are you trying to convey to someone who is looking at your picture?

- Describe how this image relates to society and what prevailing ideas about your mental health are present in this picture.

- What are some strengths about being a professional ballet dancer?

- What can we as counselors do about ballet dancers’ mental health?

- Is there anything else you would like to add?

Aug 20, 2021 | Author Videos, Volume 11 - Issue 3

Warren N. Ponder, Elizabeth A. Prosek, Tempa Sherrill

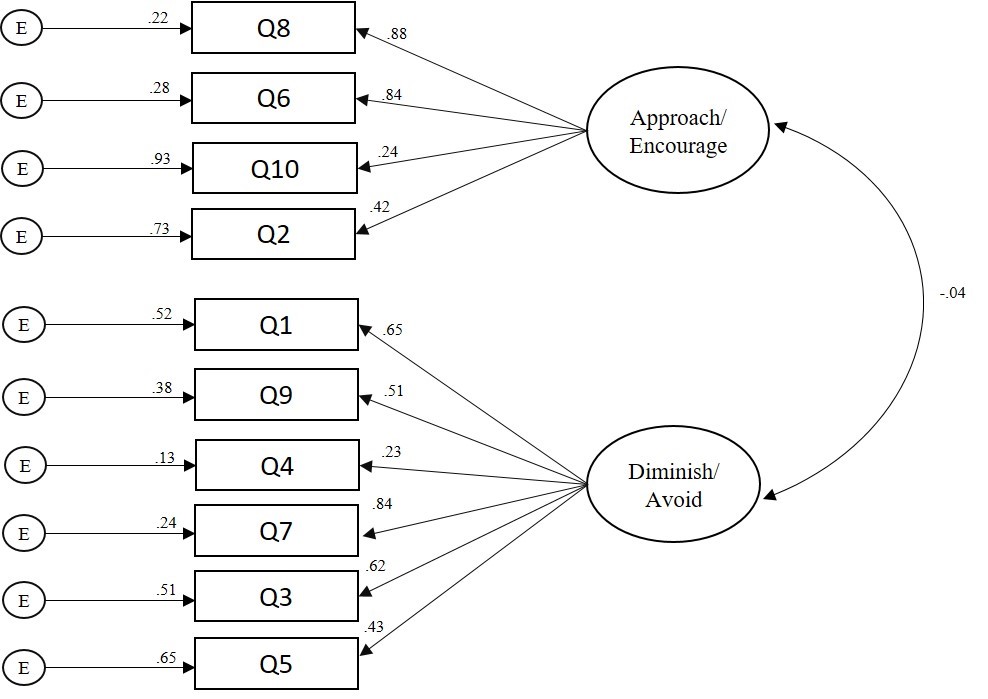

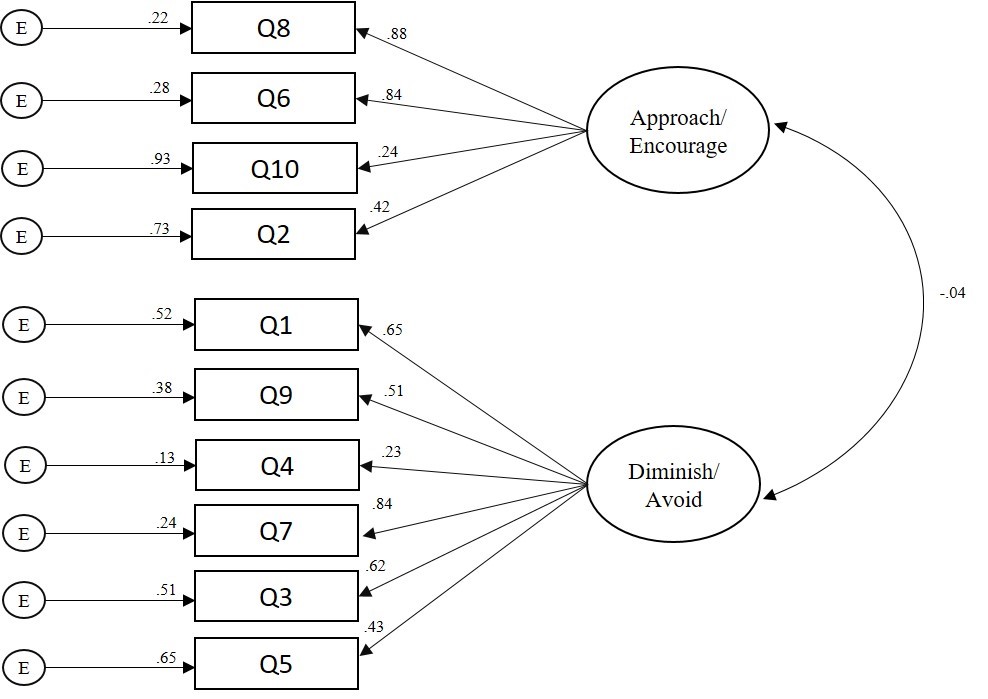

First responders are continually exposed to trauma-related events. Resilience is evidenced as a protective factor for mental health among first responders. However, there is a lack of assessments that measure the construct of resilience from a strength-based perspective. The present study used archival data from a treatment-seeking sample of 238 first responders to validate the 22-item Response to Stressful Experiences Scale (RSES-22) and its abbreviated version, the RSES-4, with two confirmatory factor analyses. Using a subsample of 190 first responders, correlational analyses were conducted of the RSES-22 and RSES-4 with measures of depressive symptoms, post-traumatic stress, anxiety, and suicidality confirming convergent and criterion validity. The two confirmatory analyses revealed a poor model fit for the RSES-22; however, the RSES-4 demonstrated an acceptable model fit. Overall, the RSES-4 may be a reliable and valid measure of resilience for treatment-seeking first responder populations.

Keywords: first responders, resilience, assessment, mental health, confirmatory factor analysis

First responder populations (i.e., law enforcement, emergency medical technicians, and fire rescue) are often repeatedly exposed to traumatic and life-threatening conditions (Greinacher et al., 2019). Researchers have concluded that such critical incidents could have a deleterious impact on first responders’ mental health, including the development of symptoms associated with post-traumatic stress, anxiety, depression, or other diagnosable mental health disorders (Donnelly & Bennett, 2014; Jetelina et al., 2020; Klimley et al., 2018; Weiss et al., 2010). In a systematic review, Wild et al. (2020) suggested the promise of resilience-based interventions to relieve trauma-related psychological disorders among first responders. However, they noted the operationalization and measure of resilience as limitations to their intervention research. Indeed, researchers have conflicting viewpoints on how to define and assess resilience. For example, White et al. (2010) purported popular measures of resilience rely on a deficit-based approach. Counselors operate from a strength-based lens (American Counseling Association [ACA], 2014) and may prefer measures with a similar perspective. Additionally, counselors are mandated to administer assessments with acceptable psychometric properties that are normed on populations representative of the client (ACA, 2014, E.6.a., E.7.d.). For counselors working with first responder populations, resilience may be a factor of importance; however, appropriately measuring the construct warrants exploration. Therefore, the focus of this study was to validate a measure of resilience with strength-based principles among a sample of first responders.

Risk and Resilience Among First Responders

In a systematic review of the literature, Greinacher et al. (2019) described the incidents that first responders may experience as traumatic, including first-hand life-threatening events; secondary exposure and interaction with survivors of trauma; and frequent exposure to death, dead bodies, and injury. Law enforcement officers (LEOs) reported that the most severe critical incidents they encounter are making a mistake that injures or kills a colleague; having a colleague intentionally killed; and making a mistake that injures or kills a bystander (Weiss et al., 2010). Among emergency medical technicians (EMTs), critical incidents that evoked the most self-reported stress included responding to a scene involving family, friends, or others to the crew and seeing someone dying (Donnelly & Bennett, 2014). Exposure to these critical incidents may have consequences for first responders. For example, researchers concluded first responders may experience mental health symptoms as a result of the stress-related, repeated exposure (Jetelina et al., 2020; Klimley et al., 2018; Weiss et al., 2010). Moreover, considering the cumulative nature of exposure (Donnelly & Bennett, 2014), researchers concluded first responders are at increased risk for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and generalized anxiety symptoms (Jetelina et al., 2020; Klimley et al., 2018; Weiss et al., 2010). Symptoms commonly experienced among first responders include those associated with post-traumatic stress, anxiety, and depression.

In a collective review of first responders, Kleim and Westphal (2011) determined a prevalence rate for PTSD of 8%–32%, which is higher than the general population lifetime rate of 6.8–7.8 % (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013; National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH], 2017). Some researchers have explored rates of PTSD by specific first responder population. For example, Klimley et al. (2018) concluded that 7%–19% of LEOs and 17%–22% of firefighters experience PTSD. Similarly, in a sample of LEOs, Jetelina and colleagues (2020) reported 20% of their participants met criteria for PTSD.

Generalized anxiety and depression are also prevalent mental health symptoms for first responders. Among a sample of firefighters and EMTs, 28% disclosed anxiety at moderate–severe and several levels (Jones et al., 2018). Furthermore, 17% of patrol LEOs reported an overall prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder (Jetelina et al., 2020). Additionally, first responders may be at higher risk for depression (Klimley et al., 2018), with estimated prevalence rates of 16%–26% (Kleim & Westphal, 2011). Comparatively, the past 12-month rate of major depressive disorder among the general population is 7% (APA, 2013). In a recent study, 16% of LEOs met criteria for major depressive disorder (Jetelina et al., 2020). Moreover, in a sample of firefighters and EMTs, 14% reported moderate–severe and severe depressive symptoms (Jones et al., 2018). Given these higher rates of distressful mental health symptoms, including post-traumatic stress, generalized anxiety, and depression, protective factors to reduce negative impacts are warranted.

Resilience

Broadly defined, resilience is “the ability to adopt to and rebound from change (whether it is from stress or adversity) in a healthy, positive and growth-oriented manner” (Burnett, 2017, p. 2). White and colleagues (2010) promoted a positive psychology approach to researching resilience, relying on strength-based characteristics of individuals who adapt after a stressor event. Similarly, other researchers explored how individuals’ cognitive flexibility, meaning-making, and restoration offer protection that may be collectively defined as resilience (Johnson et al., 2011).

A key element among definitions of resilience is one’s exposure to stress. Given their exposure to trauma-related incidents, first responders require the ability to cope or adapt in stressful situations (Greinacher et al., 2019). Some researchers have defined resilience as a strength-based response to stressful events (Burnett, 2017), in which healthy coping behaviors and cognitions allow individuals to overcome adverse experiences (Johnson et al., 2011; White et al., 2010). When surveyed about positive coping strategies, first responders most frequently reported resilience as important to their well-being (Crowe et al., 2017).

Researchers corroborated the potential impact of resilience for the population. For example, in samples of LEOs, researchers confirmed resilience served as a protective factor for PTSD (Klimley et al., 2018) and as a mediator between social support and PTSD symptoms (McCanlies et al., 2017). In a sample of firefighters, individual resilience mediated the indirect path between traumatic events and global perceived stress of PTSD, along with the direct path between traumatic events and PTSD symptoms (Lee et al., 2014). Their model demonstrated that those with higher levels of resilience were more protected from traumatic stress. Similarly, among emergency dispatchers, resilience was positively correlated with positive affect and post-traumatic growth, and negatively correlated with job stress (Steinkopf et al., 2018). The replete associations of resilience as a protective factor led researchers to develop resilience-based interventions. For example, researchers surmised promising results from mindfulness-based resilience interventions for firefighters (Joyce et al., 2019) and LEOs (Christopher et al., 2018). Moreover, Antony and colleagues (2020) concluded that resilience training programs demonstrated potential to reduce occupational stress among first responders.

Assessment of Resilience

Recognizing the significance of resilience as a mediating factor in PTSD among first responders and as a promising basis for interventions when working with LEOs, a reliable means to measure it among first responder clients is warranted. In a methodological review of resilience assessments, Windle and colleagues (2011) identified 19 different measures of resilience. They found 15 assessments were from original development and validation studies with four subsequent validation manuscripts from their original assessment, of which none were developed with military or first responder samples.

Subsequently, Johnson et al. (2011) developed the Response to Stressful Experiences Scale (RSES-22) to assess resilience among military populations. Unlike deficit-based assessments of resilience, they proposed a multidimensional construct representing how individuals respond to stressful experiences in adaptive or healthy ways. Cognitive flexibility, meaning-making, and restoration were identified as key elements when assessing for individuals’ characteristics connected to resilience when overcoming hardships. Initially they validated a five-factor structure for the RSES-22 with military active-duty and reserve components. Later, De La Rosa et al. (2016) re-examined the RSES-22. De La Rosa and colleagues discovered a unidimensional factor structure of the RSES-22 and validated a shorter 4-item subset of the instrument, the RSES-4, again among military populations.

It is currently unknown if the performance of the RSES-4 can be generalized to first responder populations. While there are some overlapping experiences between military populations and first responders in terms of exposure to trauma and high-risk occupations, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA; 2018) suggested differences in training and types of risk. In the counseling profession, these populations are categorized together, as evidenced by the Military and Government Counseling Association ACA division. Additionally, there may also be dual identities within the populations. For example, Lewis and Pathak (2014) found that 22% of LEOs and 15% of firefighters identified as veterans. Although the similarities of the populations may be enough to theorize the use of the same resilience measure, validation of the RSES-22 and RSES-4 among first responders remains unexamined.

Purpose of the Study

First responders are repeatedly exposed to traumatic and stressful events (Greinacher et al., 2019) and this exposure may impact their mental health, including symptoms of post-traumatic stress, anxiety, depression, and suicidality (Jetelina et al., 2020; Klimley et al., 2018). Though most measures of resilience are grounded in a deficit-based approach, researchers using a strength-based approach proposed resilience may be a protective factor for this population (Crowe et al., 2017; Wild et al., 2020). Consequently, counselors need a means to assess resilience in their clinical practice from a strength-based conceptualization of clients.

Johnson et al. (2011) offered a non-deficit approach to measuring resilience in response to stressful events associated with military service. Thus far, researchers have conducted analyses of the RSES-22 and RSES-4 with military populations (De La Rosa et al., 2016; Johnson et al., 2011; Prosek & Ponder, 2021), but not yet with first responders. While there are some overlapping characteristics between the populations, there are also unique differences that warrant research with discrete sampling (SAMHSA, 2018). In light of the importance of resilience as a protective factor for mental health among first responders, the purpose of the current study was to confirm the reliability and validity of the RSES-22 and RSES-4 when utilized with this population. In the current study, we hypothesized the measures would perform similarly among first responders and if so, the RSES-4 would offer counselors a brief assessment option in clinical practice that is both reliable and valid.

Method

Participants

Participants in the current non-probability, purposive sample study were first responders (N = 238) seeking clinical treatment at an outpatient, mental health nonprofit organization in the Southwestern United States. Participants’ mean age was 37.53 years (SD = 10.66). The majority of participants identified as men (75.2%; n = 179), with women representing 24.8% (n = 59) of the sample. In terms of race and ethnicity, participants identified as White (78.6%; n = 187), Latino/a (11.8%; n = 28), African American or Black (5.5%; n = 13), Native American (1.7%; n = 4), Asian American (1.3%; n = 3), and multiple ethnicities (1.3%; n = 3). The participants identified as first responders in three main categories: LEO (34.9%; n = 83), EMT (28.2%; n = 67), and fire rescue (25.2%; n = 60). Among the first responders, 26.9% reported previous military affiliation. As part of the secondary analysis, we utilized a subsample (n = 190) that was reflective of the larger sample (see Table 1).

Procedure

The data for this study were collected between 2015–2020 as part of the routine clinical assessment procedures at a nonprofit organization serving military service members, first responders, frontline health care workers, and their families. The agency representatives conduct clinical assessments with clients at intake, Session 6, Session 12, and Session 18 or when clinical services are concluded. We consulted with the second author’s Institutional Review Board, which determined the research as exempt, given the de-identified, archival nature of the data. For inclusion in this analysis, data needed to represent first responders, ages 18 or older, with a completed RSES-22 at intake. The RSES-4 are four questions within the RSES-22 measure; therefore, the participants did not have to complete an additional measure. For the secondary analysis, data from participants who also completed other mental health measures at intake were also included (see Measures).

Table 1

Demographics of Sample

| Characteristic |

Sample 1

(N = 238) |

Sample 2

(n = 190) |

| Age (Years) |

|

|

| Mean |

37.53 |

37.12 |

| Median |

35.50 |

35.00 |

| SD |

10.66 |

10.30 |

| Range |

46 |

45 |

| Time in Service (Years) |

|

|

| Mean |

11.62 |

11.65 |

| Median |

10.00 |

10.00 |

| SD |

9.33 |

9.37 |

| Range |

41 |

39 |

|

n (%) |

| First Responder Type |

|

|

Emergency Medical

Technicians |

67 (28.2%) |

54 (28.4%) |

| Fire Rescue |

60 (25.2%) |

45 (23.7%) |

| Law Enforcement |

83 (34.9%) |

72 (37.9%) |

| Other |

9 (3.8%) |

5 (2.6%) |

| Two or more |

10 (4.2%) |

6 (3.2%) |

| Not reported |

9 (3.8%) |

8 (4.2%) |

| Gender |

|

|

| Women |

59 (24.8%) |

47 (24.7%) |

| Men |

179 (75.2%) |

143 (75.3%) |

| Ethnicity |

|

|

| African American/Black |

13 (5.5%) |

8 (4.2%) |

| Asian American |

3 (1.3%) |

3 (1.6%) |

| Latino(a)/Hispanic |

28 (11.8%) |

24 (12.6%) |

| Multiple Ethnicities |

3 (1.3%) |

3 (1.6%) |

| Native American |

4 (1.7%) |

3 (1.6%) |

| White |

187 (78.6%) |

149 (78.4%) |

Note. Sample 2 is a subset of Sample 1. Time in service for Sample 1, n = 225;

time in service for Sample 2, n = 190.

Measures

Response to Stressful Experiences Scale

The Response to Stressful Experiences Scale (RSES-22) is a 22-item measure to assess dimensions of resilience, including meaning-making, active coping, cognitive flexibility, spirituality, and self-efficacy (Johnson et al., 2011). Participants respond to the prompt “During and after life’s most stressful events, I tend to” on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (not at all like me) to 4 (exactly like me). Total scores range from 0 to 88 in which higher scores represent greater resilience. Example items include see it as a challenge that will make me better, pray or meditate, and find strength in the meaning, purpose, or mission of my life. Johnson et al. (2011) reported the RSES-22 demonstrates good internal consistency (α = .92) and test-retest reliability (α = .87) among samples from military populations. Further, the developers confirmed convergent, discriminant, concurrent, and incremental criterion validity (see Johnson et al., 2011). In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha of the total score was .93.

Adapted Response to Stressful Experiences Scale

The adapted Response to Stressful Experiences Scale (RSES-4) is a 4-item measure to assess resilience as a unidimensional construct (De La Rosa et al., 2016). The prompt and Likert scale are consistent with the original RSES-22; however, it only includes four items: find a way to do what’s necessary to carry on, know I will bounce back, learn important and useful life lessons, and practice ways to handle it better next time. Total scores range from 0 to 16, with higher scores indicating greater resilience. De La Rosa et al. (2016) reported acceptable internal consistency (α = .76–.78), test-retest reliability, and demonstrated criterion validity among multiple military samples. In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha of the total score was .74.

Patient Health Questionnaire-9